Abstract

The addition of edible fiber could affect the shelf life of cookies, which can have a positive or negative impact depending on the source of fiber. This study is in continuation of two previously published papers to investigate the storage stability of cookies incorporated with 4.5% beetroot leaf powder (BLP), with 7% sapota fiber powder (SFP) and reference cookies during 15 months at ambient temperature by analyses of physicochemical, microbial and sensory properties on each specified month using international standard methods. It was found that with increasing storage period, there was an increment in moisture content, peroxide value, free fatty acids and microbial population including total aerobic bacteria and yeast and mold colonies of all cookies; the lowest values being for cookies with 7% SFP (5.70%, 4.12 mEqO2/1000 g cookie's fat, 1.47%, 2.73 and 2.36 log CFU/g dried cookie, respectively). In contrast, the reverse trend was found in pH value. At the end of storage, a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) was observed between reference cookies and other cookies regarding moisture content, peroxide value, free fatty acids and overall sensory acceptability; the quality of cookies supplemented with 7% SFP being desirable, followed by cookies with 4.5% BLP, and then reference cookies.

Keywords: Storage stability; Cookie; Microbial analysis; Physicochemical analysis, Sensory properties

Introduction

Bakery products including bread, cookies, rolls, pastries, pies and muffins are an integral part of the diet widely consumed worldwide (Saeed et al. 2019). Owing to the low moisture content and long shelf life of cookies, they differ from other bakery products (Agu and Okoli 2014). The principal ingredients of the cookie, namely fat, sugar and wheat flour, along with its shelf life, lead to the growing interest in cookie consumption as a ready-to-serve caloric snack by the majority of the population; however, it lacks in nutrients (Manley 2001; Nagarajaiah and Prakash 2015). In this way, regular wheat-based cookies are not suitable as a daily intake for human health; it is essential to enhance its nutrient components (Manley 2001; Asadi and Khan 2021).

The sapota or sapodilla or chiku (Manilkara zapota L.) and beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) belong to the family of Sapotaceae and Chenopodiaceae, respectively (Fernández et al. 2017; Kulkarni et al. 2007; Shui et al. 2004). Contrary to the excellent nutritional and phyto-nutritional components of beetroot leaf such as protein, vitamin, mineral, fiber, phenolic compound, antioxidant activity, it is often removed from its tuber and not used in the human diet (Asadi and Khan 2019; Biondo et al. 2014; Fernández et al. 2017; Shahenda and Jehan 2018). In addition, sapota is a nutritive tropical fruit that not only pulp is edible but also its peel. Nevertheless, the pulp of sapota is usually eaten, and its peel is discarded (Shui et al. 2004; Kulkarni et al. 2007; Asadi et al. 2021). Since the shelf life of sapota is short, the loss after harvesting is also an essential issue in tropical countries (Panda et al. 2014). The exploitation of the sapota and beetroot leaf as health-promoting substances into food products was suggested by several studies (Asadi and Khan 2019; 2021; Asadi et al. 2021; Fernández et al. 2017; Kulkarni et al. 2007; Shui et al. 2004).

Although the utilization of beetroot leaf and sapota can be challengeable in the enhancement of nutritional value of cookies, the supplementary non-wheat powder into cookie formulation can influence the quality and shelf life of this product (Dokić et al. 2014; Uthumporn et al. 2015; Asadi and Khan 2021; Asadi et al. 2021). It has been reported that cookies supplemented with 4.5% beetroot leaf powder (BLP) and cookies enriched with 7% sapota fiber powder (SFP) gained the highest sensory scores among cookies containing BLP and SFP at different levels of 4.5, 7, 9.5 and 12% that were made by Asadi and Khan (2021) and Asadi et al. (2021). The kinds of vegetables and fruits as well as the percentages of fiber were decided according to the prior review researches and preliminary baking trials (Asadi and Khan 2021; Asadi et al. 2021). Nevertheless, according to our knowledge, there are no published reports on the investigation of the shelf life of cookies incorporated with BLP and SPF. As the supplementation of cookies with non-wheat flour such as edible fiber could affect the physicochemical, microbiological and sensory properties of cookies, followed by the effects on shelf life of cookies, this research was conducted following two previously published papers by Asadi and Khan (2021) and Asadi et al. (2021) to study the storage stability of developed cookies with added fiber from BLP at 4.5% and SFP at 7%. The proximate composition of cookies with 4.5% BLP, cookies containing 7% SFP and reference cookies are shown in Table 1 (Asadi and Khan 2021; Asadi et al. 2021). Therefore, the purpose of this research was to investigate the shelf life of cookies by evaluating changes in the physicochemical parameters (i.e., moisture content, pH value, peroxide value (PV) and free fatty acids (FFA)), microbial properties (including aerobic mesophilic bacteria and yeast and mold count), and sensory characteristics (namely color, texture, taste, aroma and overall acceptability over time) on each specified month under the same conditions of temperature, humidity and packaging using international standard methods.

Table 1.

Formulation of cookie samples

| Ingredients (%) | Types of cookies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R–C† | 4.5BL-C‡ | 7SF-C§ | |

| Refined wheat flour | 100 | 95.5 | 93 |

| BLP¶ | - | 4.5 | - |

| SFP# | - | - | 7 |

| Refined sugar powder | 48 | 48 | 48 |

| Unsalted butter | 38 | 38 | 38 |

| Milk powder | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Ammonium bicarbonate | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 |

| common salt | 0. 5 | 0. 5 | 0. 5 |

| Lecithin powder | 0. 14 | 1.4 | 1.4 |

| Vanilla flavor liquid | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Potable water | 10–12 | 10–12 | 10–12 |

†R–C Reference cookie, ‡4.5BL-C Cookie containing 4.5% beetroot leaf powder, §7SF-C: Cookie containing 7% sapota fiber powder, ¶BLP Beetroot leaf powder, #SFP Sapota fiber powder

Materials and methods

Raw materials

The leaves of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) and sapota (Manilkara zapota L.) with other raw materials for cookie making and low-density polyethylene (LDPE) pouches were collected from the markets of U.P., India. The analytical grade solvents and chemical materials were used in this research.

Preparation of BLP and SFP

The BLP was prepared according to the procedure described by Asadi and Khan (2019; 2021). Briefly, beetroot leaves were washed with running water and soaked in NaClO solution (40 mg/L) for 30 min (Galla et al. 2017). After re-washing, beetroot leaves were chopped into small uniform sizes, and microwave blanching was conducted at 560 W for 50 s in a microwave system (Kenstar, India). The samples were dried at 60 ± 2 °C for 7 h using a tray drier (Biogen Scientific, India). After grinding and sieving to a particle size smaller than 0.18 mm, they were packed in LDPE pockets and stored at -18 °C for further use.

The SFP was made from sapota by the same aforementioned method, done by Asadi et al. (2021), followed by removing the seed, chopping, and extracting juice as per cold press in a clean muslin cloth. Afterwards, the residue of juice extraction was mixed with drinking water at the ratio of 1:1 (w/v) and again squeezed to remove the remaining juice. Obtained pomace was dried at 58 ± 2 °C for 6 h by tray drier, ground and sieved to create a particle size of less than 0.18 mm. Then they packed in LDPE bags and kept at -18 °C for further usage.

Production of cookies

The cookie samples were made as per the method of Kar et al. (2013) and done by Asadi and Khan (2021) and Asadi et al. (2021). The applied ingredients in the cookies were 100% composition flour, 38% unsalted butter, 48% refined sugar powder, 0.5% common salt, 1% ammonium bicarbonate, 0.75% sodium bicarbonate, 0.14% lecithin, 1.5% vanilla liquid flavor, 2% milk powder and 10- 12% potable water. The composite flour used in this research was the mixture of wheat flour with either BLP or SFP at the ratios of 100/0, 95.5/4.5 and 93/7 (w/w)%, for production of three kinds of cookies i.e., reference cookies, enriched BLP cookies and enriched SFP cookies, respectively. The consistent dough was prepared by kneading all ingredients. After sheeting and shaping of consistent dough in circular pieces with a thickness of around 0.44 ± 0.05 cm and diameter of 5 cm, they were baked for 20 ± 2 min at 168 ± 2 °C using the bakery oven (Bake Tech Enterprises, New Delhi, India). The packed cookies in LDPE punches were kept under the same conditions at room temperature (average temperature 28 ± 10 °C and average humidity 65 ± 5%) and away from exposure to sunlight for further analysis.

Physicochemical analysis

The moisture content and pH value of samples were assessed according to the official methods of AOAC (1999), methods 925.10 and 943.02, respectively. The FFA and PV were determined according to methods 2.201 and 2.501 of IUPAC (1987). The pH value was measured using the pH Meter (HM Digital, pH-80 pH Hydrotester, Korea).

Microbiological analysis

Microbiological analyses including total aerobic mesophilic bacteria and yeast and mold counts were performed according to the method depicted in AACC (2000); methods 42–11 and 42–50, respectively. The preparation of serial dilutions of samples was done following the AACC method 42–10 (AACC, 2000). The microbial counts were reported as log colony forming units per g dried sample (log CFU/g DS).

Sensory analysis

Several sensory characteristics of cookies, viz. color, taste, texture, aroma and overall acceptability were investigated by a panel of members including staff and students of the department using 9-Point-Hedonic-Scale, where the score of 1 indicated "dislike extremely", while the score of 9 represented "like extremely". The average scores greater than or equal to 6 (like moderately) were considered acceptable (Asadi and Khan 2021; Asadi et al. 2021).

Statistical analysis

All the analytical experiments were carried out in triplicates and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc multiple comparisons was applied to analyze data statistically using the SPSS software, version 22 (IBM). The P-value ≤ 0.05 was considered to determine the significant differences.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical properties of stored cookies

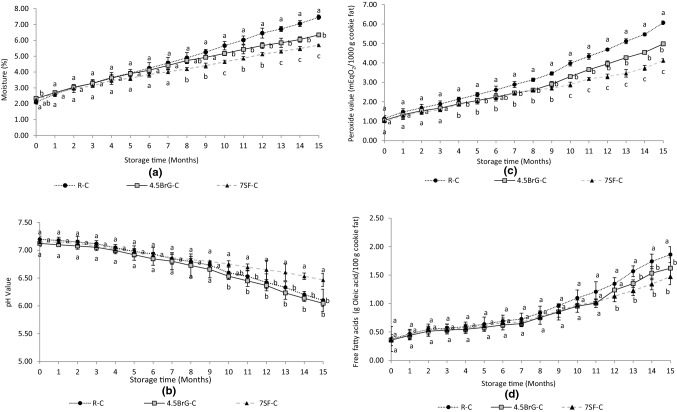

The stored cookies including cookies incorporated with 4.5% BLP, cookies prepared with 7% SFP along with reference cookies were analyzed in respect of the moisture content, pH value, PV and FFA at the interval of every month (24 h after preparation of cookies) until 15 months of storage (Fig. 1 a-d). An increase in moisture content, PV, and FFA was recorded in all stored cookies with the increase of storage time, while the reverse trend was found in terms of pH value.

Fig. 1.

Changes in moisture content (a), pH value (b), peroxide value (c) and free fatty acids (d) of cookies during storage time. R–C: Reference cookie without any fiber, 4.5BL-C: Cookie containing 4.5% beetroot leaf powder, 7SF-C: Cookie containing 7% sapota fiber powder. Different superscript letter on the same month of analysis represents statistical differences (p ≤ 0.05) between the cookie samples on that particular month of analysis

The moisture content as a crucial characteristic of cookies has a significant effect on cookie quality and shelf life (Manley 2001). The maximum level of 5% moisture content has been reported for a cookie without cream by Manley (2001) and Ogunjobi and Ogunwolu (2010). The acceptable moisture content of less than 14% has been noted for regular cookies (Ogunjobi and Ogunwolu 2010). In this study, the increment of moisture content in reference cookies, cookies containing 4.5% BLP and cookies prepared with 7% SFP respectively ranged from 2.10 to 7.46, 2.34 to 6.34 and 2.27 to 5.70%, from the beginning of storage (0 month) to the end of storage period (Fig. 1a). The lowest and highest moisture content range belonged to the cookie incorporated with 7% SFP and reference cookie, respectively. The moisture content of less than 5% was observed for reference cookies from the beginning of storage up to month 8; meanwhile, it was found for cookies containing 4.5% BLP and cookies made with 7% SFP up to months 9 and 11 of storage, respectively. The increase of moisture content in cookies during the storage time could be explained by the hygroscopic property of cookies; the cookies could absorb water vapor that is migrated from the package seal (Thivani et al. 2016; Kumar et al. 2016). The differences in moisture absorbtion of cookies could be due to the variation in some physicochemical properties of the applied composite flour in cookie formulations, mainly because of the impact of added fiber and surrounding water that could be migrated into the package during storage. Moreover, an important role of packaging in protecting cookies from atmospheric moisture has been confirmed by Manley (2001) and Pupulawaththa et al. (2014).

The pH value is one of the essential parameters that may affect the cookie taste (Ogunjobi and Ogunwolu 2010). Changes in pH values of cookies are illustrated in Fig. 1b. The rate of pH value in the y-axis is shown from 5 for better visualization of changes in pH values of stored cookies over time. As shown in Fig. 1b, the pH value in all cookies were slightly reduced as the storage period increased, whereas at the end of storage, the pH value of cookies containing 7% SFP was significantly higher (p ≤ 0.05) than that of reference cookies and cookies incorporated with 4.5% BLP. However, there was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between reference cookies and cookies containing 4.5% BLP and cookies incorporated with 7% SFP in terms of pH value from month 0 to 11. The pH value in all stored cookies throughout the storage remained greater than 6, which is considered non-acidic products. The pH value of reference cookie, cookie enriched with 4.5% BLP and cookie incorporated with 7% SFP ranged from 7.20 to 6.10, 7.12 to 6.05 and 7.15 to 6.47 from month 0 to month 15, respectively. The difference between the pH values of stored cookies probably was influenced by the variance in the pH value of composited flours made of wheat flour with either BLP or SFP, in addition to the generation of organic acids by microorganisms over time. Pupulawaththa et al. (2014) reported that a reduction in pH value of cookies over time might be due to producing organic acids by microorganisms with the pass of time. The pH values of 6.81 and 6.41 for cookies prepared with kohila (Lasia spinosa) powder at levels of 0 and 15% have been noted by Pupulawaththa et al. (2014). However, Uchoa et al. (2009) recorded the range of around 7.2- 6.4 for cookies made with different ratios of cashew apple powder and cassava flour.

The fat content, one of the essential ingredients of cookies, can be ranged from 12 to 30% (Manley 2001). Hence, the cookies' fat is at risk of hydrolysis and oxidation, causing an increase in the levels of FFA and PV of cookies (Ismail et al. 2014). In this research, the increasing trends in PV and FFA were observed for all the stored cookies over the storage, in which the increments of PV and FFA in reference cookies were greater than other stored cookies containing fiber (Fig. 1 c and d). The increasing trend in PV and FFA of cookies during storage time could be due to the oxidation and hydrolysis of cookies' fat (Ismail et al. 2014; Pupulawaththa et al. 2014; Daglioglu et al. 2004).

Figure 1c illustrates that the PV for reference cookies and cookies containing 4.5% BLP and cookies supplemented with 7% SFP ranged from 1.14 to 6.07, 1.04 to 4.98, and 1.01 to 4.12 mEqO2/1000 g cookie's fat from month 0 to month 15 of storage, respectively. There was a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) between PV of three kinds of stored cookies from month 10 to the end of storage, being the smallest PV for cookie containing 7% SFP, followed by the cookie incorporated with 4.5% BLP and finally reference cookie on the same month of storage.

In this research, the value of FFA in reference cookie, cookie incorporated with 4.5% BLP and cookie containing 7% SFP varied from 0.38 to 1.86, 0.36 to 1.62, and 0.37 to 1.47% from month 0 to the end of storage, respectively (Fig. 1d). There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) between the FFA of three kinds of stored cookies from the beginning of storage up to month 11; thereafter, this trend up to month 15 considerably went up. It was demonstrated that the value of FFA in reference cookies on the same month of storage was greater than other stored cookies containing fiber (BLP and SFP).

This variation in PV as well as FFA between stored cookies during the storage period might be due to the changes in moisture content of cookies over time. Besides, the higher antioxidant activity of cookies containing BLP and SFP compared with the reference cookies (Table 2) can be one of the reasons to stop or delay fat oxidation. Uthumporn et al. (2015) and Pupulawaththa et al. (2014) also reported that natural antioxidants in cookies containing fruit and vegetable fiber could be one of the reasons for stopping or delaying fat oxidation in such enriched cookies. On the other hand, the increase in PV of cookies might be associated with the oxygen migration into the packaging, which could be resulted in starting fat oxidation and slight rancidity. Therefore, the supplementation of cookies with vegetable and fruit powder led to reduced PV, FFA, and off-flavor during storage time. This pattern has also been shown by Ismail et al. (2014) and Uthumporn et al. (2015), who noted that the supplementation of cookies with pomegranate peel powder and eggplant powder led to a decline generation of FFA, PV and off-flavor over four and two months of storage, respectively. The pattern was also explained by the considerable antioxidant activity of cookies containing pomegranate peel powder and eggplant powder compared to the control cookie (Ismail et al. 2014; Uthumporn et al. 2015).

Table 2.

| Properties (%) | Types of cookies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| R–C† | 4.5BL-C‡ | 7SF-C§ | |

| Moisture | 2.10 ± 0.13b | 2.34 ± 0.03a | 2.27 ± 0.02ab |

| Crude fiber | 0.89 ± 0.25c | 2.01 ± 0.18b | 3.41 ± 0.26a |

| Total dietary fiber | 2.38 ± 0.18c | 5.02 ± 0.69b | 14.03 ± 0.57a |

| Protein | 6.05 ± 0.15b | 6.56 ± 0.16a | 5.72 ± 0.07b |

| Ash | 0.48 ± 0.06b | 1.26 ± 0.17a | 0.63 ± 0.25b |

| Fat | 17.10 ± 0.27b | 17.56 ± 0.20b | 18.69 ± 0.29a |

| Antioxidant activity | 0.27 ± 0.11c | 7.59 ± 0.39a | 6.20 ± 0.48b |

†R–C Reference cookie, ‡4.5BL-C Cookie containing 4.5% beetroot leaf powder, §7SF-C: Cookie containing 7% sapota fiber powder

All characteristics except moisture content are expressed on a dry weight basis of a sample. Data are mean of three replicates ± standard deviation. Data except moisture content are expressed on a dry matter basis in which the values with the same superscript letter in the row do not differ significantly (p > 0.05)

The values of 1.5% and 10 mEqO2/1000 g of cookie's fat have been noticed as the maximum standard level of FFA and PV in cookies, respectively (Daglioglu et al. 2004). In this research, the PV of all stored cookies was permissible during the shelf life (Fig. 1c). However, the value of FFA from month 0 up to month 12 for reference cookies and up to months 13 and 15 for cookies incorporated with 4.5% BLP and cookies supplemented with 7% SFP was permissible, respectively (Fig. 1d). The allowable values of around 1.20% and 4.9 mEqO2/1000 g sample fat were also observed respectively for FFA and PV in cookies prepared by Daglioglu et al. (2004) over 12 months of storage.

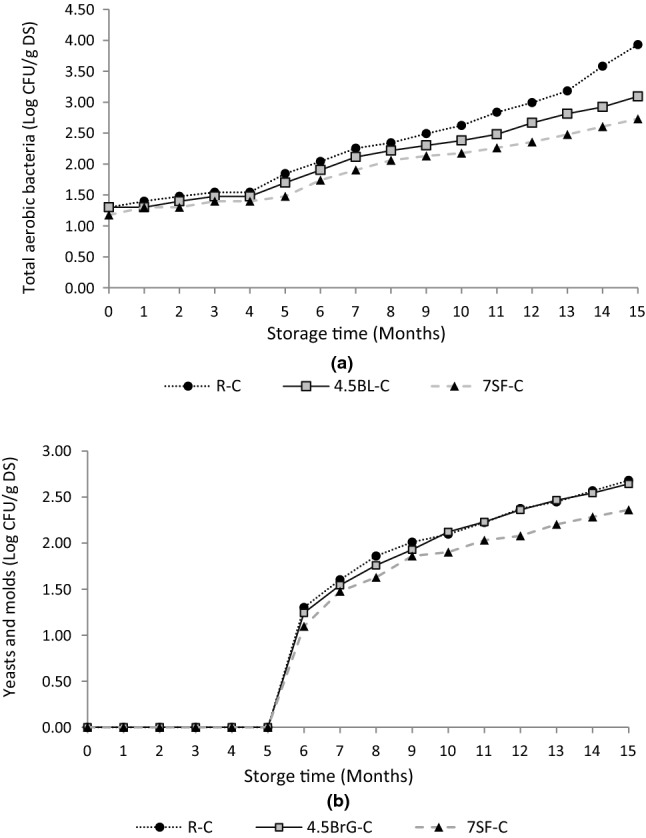

Microbiological properties of stored cookies

As presented in Fig. 2a, the total aerobic bacteria in reference cookie, cookie containing 4.5% BLP and cookie supplemented with 7% SFP gradually increased from 1.30 to 3.93, 1.30 to 3.09 and 1.18 to 2.73 log CFU/g DS from month 0 to the end of storage period, respectively. The total aerobic bacteria count fairly remained stable in all three kinds of cookies for the first four months of storage and then gradually increased. The rise in total aerobic bacteria was notable, corresponding to the reference cookie from month 13 to month 15 of storage. In this research, initial total aerobic bacteria could be attributed to the processing condition such as cooling and packaging. Nevertheless, the increase of microbial load after the first four months of storage could be due to changes in cookies' physicochemical properties, such as moisture content and pH value.

Fig. 2.

Changes in total aerobic bacteria (a) and yeasts and molds (b) of cookies during storage time. R–C Reference cookie without any fiber, 4.5BL-C Cookie containing 4.5% beetroot leaf powder, 7SF-C Cookie containing 7% sapota fiber powder, Log CFU/g DS Log colony forming units per g of dry weight of a sample

The yeast and mold colonies were not detected up to month 5 in case of all stored cookies (Fig. 3b). The increment in yeast and mold count was ranged from 1.30 to 2.68, 1.24 to 2.64 and 1.10 to 2.36 log CFU/g DS in reference cookies, cookies containing 4.5% BLP and cookies made with 7% SFP from month 6 to the end of storage period, respectively. The smallest range of yeast and mold colonies was observed in cookies incorporated with 7% SFP. However, the growth of yeast and mold in reference cookies as well as cookies made with 4.5% BLP was noticeable.

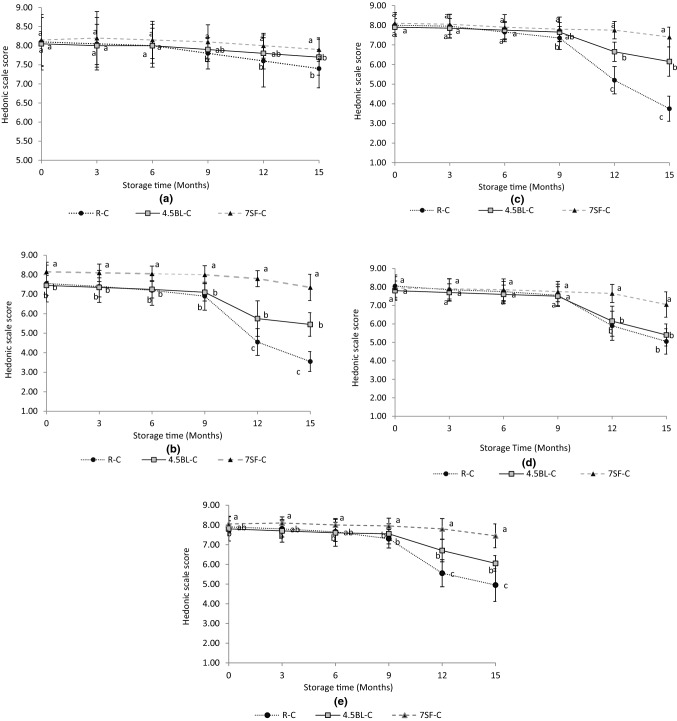

Fig. 3.

Changes in color (a), texture (b), taste (c), aroma (d) and overal acceptability (e) of cookies during storage time. R–C Reference cookie without any fiber, 4.5BL-C Cookie containing 4.5% beetroot leaf powder, 7SF-C Cookie containing 7% sapota fiber powder, Different superscript letter on the same month of analysis represents statistical differences (p ≤ 0.05) between the cookie samples on that particular month of analysis

In this research, the considerable amount of microbial count in reference cookie could be associated with the high moisture content of reference cookie compared to other stored cookies containing fiber (Table 2 and Fig. 1a), with a probability of some difference in phytochemical and antimicrobial properties of cookies' ingredients namely, wheat flour, BLP and SFP that require a further study. The cookies are often free from microbial spoilage because of low moisture content of around 1 to 5% (Manley 2001). However, microbial activity in food products is not only influenced by the moisture content of the substrate. It has been reported that surrounding moisture and air that could be migrated inside of packaging and changes in physicochemical properties of cookies such as moisture content and pH value most probably affected the microbial load of cookies over time. Besides, the nutritional value of food products presumably influences microbial growth (Shahbaz et al. 2013; Yusufu et al. 2016).

The maximum standard level of total aerobic bacteria and yeast and mold count are respectively 4.70 and 3.70 log CFU/g the cookie (Pupulawaththa et al. 2014). Thus, the microbial population in all stored cookies was permissible throughout 15 months of the storage period in the current study.

Sensory properties of stored cookies

Figure 3 (a-e) shows changes in sensory acceptability of cookies over time on each specified month, namely 0, 6, 9, 12 and 15. It was revealed a gradual decline in scores of sensory parameters (i.e., texture, taste, color, aroma and overall acceptability) for all three kinds of cookies with increasing storage time.

The hedonic scale score shown in Fig. 3a on the y-axis is started from 5 to visualize better changes in the score of color acceptability of cookies over time. Besides, none of the cookies samples gained a score of less than five. There was a negligible variation regarding the visual color of cookies throughout the storage period (Fig. 3a). However, a remarkable reduction was found in the case of texture (Fig. 3b), taste (Fig. 3c), aroma (Fig. 3d) and overall acceptability (Fig. 3e) of cookies after month 9 of storage.

Regarding the color acceptability of cookies from Fig. 3a, it can be seen that the score of color acceptability is slightly reduced in all three kinds of cookies over time. There was no significant difference (p > 0.05) in color acceptability between all three kinds of cookies from month 0 to 6; however, from month 9 to 15 there was a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) in color acceptability between cookies containing 7% SFP and other cookies. From Fig. 3b, it is clear that the score of texture acceptability in cookies supplemented with 7% SFP was significantly (p ≤ 0.05) higher than other cookies throughout the storage period. However, there was a non-significant difference (p > 0.05) in texture acceptability between the reference cookies and cookies containing 4.5% BLP from month 0 to 9. After month 9, there was a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) between the texture score of all three kinds of cookies, being the lowest score for the reference cookies and the largest score for cookies supplemented with 7% SFP (Fig. 3b). Figure 3c shows an insignificant difference (p > 0.05) between all three types of cookies concerning taste from month 0 to 6. However, a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) in taste score was found between three kinds of cookies from month 9 to 15, whereas at the end of storage the lowest taste score was subjected for reference cookies and the highest for cookies containing 7% SFP. From Fig. 3d, it is evident that there were no significant differences (p > 0.05) between all the three kinds of cookies in terms of aroma from month 0 to 9. However, after month 9 there was a significant difference (p ≤ 0.05) between cookies supplemented with 7% SFP and other cookies; the lowest aroma score being for reference cookies and the highest for cookies incorporated with 7% SFP. Regarding overall acceptability, a gradual reduction was observed, whereas at the end of storage the cookies containing 7% SFP received the highest sensory scores, followed by the cookies supplemented with 4.5% BLP and then the reference cookies (Fig. 3e). Therefore, in this study, at the end of storage period, the largest scores for all investigated sensory parameters were assigned to the cookies made with 7% SFP followed by cookies containing 4.5% BLP and then reference cookies.

It has been noted that changes in sensory characteristics of cookies over time might be the result of alterations in some physicochemical parameters of cookies such as moisture content, pH value, FFA and PV that could affect the texture, taste, and aroma of cookies (Manley 2001; Ogunjobi and Ogunwolu 2010; Ismail et al. 2014; Wani and Sood 2014; Thivani et al. 2016). Similarly, Thivani et al. (2016) also found a decline in the overall acceptability score of cookies incorporated with various levels of pineapple powder (0, 3, 5, 10, and 15%) during 7 weeks storage time. Also, Wani and Sood (2014) showed a gradual decrease in the overall acceptability of developed cookies supplemented with cauliflower (Brassica oleracea) leaf powder for 90 days of storage.

Conclusions

The results revealed that the addition of edible fiber could affect the physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory properties of cookies, followed by effects on the shelf life of cookies, which depending on the sources of fiber, can have a pleasant or adverse impact. Besides, the present study showed that SFP up to 7% and BLP up to 4.5% could be used in cookies with good storage stability and desirable sensory properties to add the cookie's nutritional value. It was found that at the end of storage, the lowest range of moisture content (2.27—5.70%), PV (1.01—4.12 mEqO2/1000 g fat of cookie), FFA (0.37—1.47%), and microbial population including total aerobic bacteria (1.18—2.73 log CFU/g dried cookie) and yeast and mold colonies (1.10—2.36 log CFU/g dried cookie) was observed for cookies supplemented with 7% SFP. However, the smallest range of pH values (7.12—6.05) was obtained for cookies containing 4.5% BLP compared to other cookies. The moisture content of less than 5% was found for reference cookies from month 0 to month 8; however, it was found for cookies supplemented with 4.5% BLP and cookies prepared with 7% SFP up to months 9 and 11 of the storage period, respectively. Regarding the sensory and physicochemical parameters of the cookies during 15 months of storage, the cookies incorporated with 7% SFP could be considered as desirable cookies, followed by cookies supplemented with 4.5% BLP and then the reference cookies. It follows that edible fibers from fruit pomace and vegetable waste could be suggested as the economic and natural sources of nutrients in cookies that can be one of the reasonable approaches for making value-added cookies with a good shelf life. Further studies might be recommended on the effects of different percentages of fiber on the extension of the shelf life of cookies with the investigation on the rate of preservative effects. Moreover, a study on the biochemical changes at the cellular and molecular level due to the effect of added fiber on physicochemical, microbiological, and sensory properties of cookies could also be suggested for further research.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the Department of Post-Harvest Engineering and Technology, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences, AMU, India, for providing necessary laboratory facilities

Author contribution

Asadi SZ conceived, carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript; Khan MA supervised the work and edited the manuscript; Zaidi S edited and helped in the revision of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict interest

The authors declare having no conflict or competing interests with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed for publishing the manuscript in the present format.

Availability of data

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- AACC (2000) Approved methods of the American association of cereal chemists, AACC methods 42-10, 42-11 and 42-50, 10th edn. St. Paul, Minn

- Agu HO, Okoli NA. Physico-chemical, sensory, and microbiological assessments of wheat-based biscuit improved with beniseed and unripe plantain. Food Sci Nutr. 2014;2(5):464–469. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AOAC . Official methods of analysis of AOAC international, AOAC methods 925.10 and 943.02. 16. Gaithersburg, MD: USA Association of Analytical Communities; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Asadi SZ, Khan MA (2019) Nutrients, phytochemicals and colour parameters of microwave and steam blanched dried beetroot [Beta vulgaris (L.) var. Conditiva] leaves. Int J Proc Post Harvest Technol 10(1):1–8. doi:10.15740/has/ijppht/10.1/1-8

- Asadi SZ, Khan MA (2021). The effect of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) leaves powder on nutritional, textural, sensorial and antioxidant properties of cookies. J Culinary Sci Technol 19(5): 424–438. Doi:10.1080/15428052.2020.1787285

- Asadi SZ, Khan MA. Chamarthy RV (2021) Development and quality evaluation of cookies supplemented with concentrated fiber powder from chiku (Manilkara zapota L.). J Food Sci Technol 58(5): 1839–1847. Doi:10.1007/s13197-020-04695-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Biondo PBF, Boeing JS, Barizão ÉO, Souza NED, Matsushita M, Oliveira CCD, Boroski M, Visentainer JV (2014). Evaluation of beetroot (Beta vulgaris L.) leaves during its developmental stages: a chemical composition study. Food Sci Technol 34(1): 94–101. Doi:10.1590/S0101-20612014005000007

- Daglioglu O, Tasan M, Gecgel U, Daglioglu F. Changes in oxidative stability of different bakery products during shelf life. Food Sci Technol Res. 2004;10(4):464–468. doi: 10.3136/fstr.10.464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dokić L, Nikolić I, Šoronja-Simović D, Pajin B, Juul N. Sensory characterization of cookies with chestnut flour. Int J Nutr Food Eng. 2014;8(5):416–419. doi: 10.5281/zenodo.1092193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández MV, Jagus RJ, Agüero MV (2017) Evaluation and characterisation of nutritional, microbiological and sensory properties of beet greens. Acta Sci Nutr Health 1(3):37–45. https://www.actascientific.com/ASNH/ASNH-01-0030.php. Accessed on 13th July, 2020

- Galla NR, Pamidighantam PR, Karakala B, Gurusiddaiah MR, Akula S. Nutritional, textural and sensory quality of biscuits supplemented with spinach (Spinacia oleracea L.) Int J Gastron Food Sci. 2017;7:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgfs.2016.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail T, Akhtar S, Riaz M, Ismail A. Effect of pomegranate peel supplementation on nutritional, organoleptic and stability properties of cookies. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2014;65(6):661–666. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2014.908170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IUPAC (1987) International union for pure and applied chemistry, Standard methods of analysis for the analysis of oils, fats and derivatives, IUPAC methods 2.201 and 2.501, 7th edn. Blackwell Jevent Publishers, Oxford

- Kar S, Mukherjee A, Ghosh M, Bhattacharyya DK (2013) Utilization of Moringa leaves as valuable food ingredient in biscuit preparation. Int J Appl Sci Eng 1(1):29–37. https://www.indianjournals.com/ijor.aspx?target=ijor:ijase&volume=1&issue=1&article=005. Accessed on 12th August, 2020

- Kulkarni AP, Policegoudra RS, Aradhya SM (2007) Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of sapota (Achras sapota Linn.) fruit. J Food Biochem 31(3):399–414. Doi:10.1111/j.1745-4514.2007.00122.x

- Kumar KA, Sharma GK, Khan MA, Semwal AD. A study on functional, pasting and micro-structural characteristics of multigrain mixes for biscuits. J Food Meas Charact. 2016;10(2):274–282. doi: 10.1007/s11694-016-9304-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manley D. Biscuit, cracker and cookie recipes for the food industry. 3. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing Ltd; Abington Hall; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajaiah SB, Prakash J. Nutritional composition, acceptability and shelf stability of carrot pomace-incorporated cookies with special reference to total and β-carotene retention. Cogent Food Agric. 2015;1(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/23311932.2015.1039886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogunjobi MAK, Ogunwolu SO. Physicochemical and sensory properties of cassava flour biscuits supplemented with cashew apple powder. J Food Tech. 2010;8(1):24–29. doi: 10.3923/jftech.2010.24.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panda SK, Sahu UC, Behera SK, Ray RC. Fermentation of sapota (Achras sapota Linn.) fruits to functional wine. Nutrafoods. 2014;13(4):179–186. doi: 10.1007/s13749-014-0034-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pupulawaththa AW, Perera ODAN, Ranwala A. Development of fiber rich soft dough biscuits fortified with kohila (Lasia spinosa) flour. J Food Process Technol. 2014;5(12):1–8. doi: 10.4172/2157-7110.1000395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed I, Shaheen S, Hussain K, Khan MA, Jaffer M, Mahmood T, Khalid S, Sarwar S, Tahir A, Khan F. Assessment of mold and yeast in some bakery products of Lahore, Pakistan based on LM and SEM. Microsc Res Tech. 2019;82(2):85–91. doi: 10.1002/jemt.23103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbaz M, Hanif K, Masood S, Rashid AA, Bilal M, Akbar N (2013) Microbiological safety concern of filled bakery products in Lahore. Pak J Food Sci 23(1):37–42. https://psfst.org/paper_files/7545_202594_7.pdf. Accessed on 12th August, 2020

- Shahenda ME, Jehan BA. The anti-anemic effect of dried beet green in phenylhydrazine treated rats. Arch Pharm Sci ASU. 2018;2(2):54–69. doi: 10.21608/aps.2018.18735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shui G, Wong SP, Leong LP. Characterization of antioxidants and change of antioxidant levels during storage of Manilkara zapota L. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52(26):7834–7841. doi: 10.1021/jf0488357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thivani M, Mahendren T, Kanimoly M. Study on the physicochemical properties, sensory attributes and shelf life of pineapple powder incorporated biscuits. Ruhuna J Sci. 2016;7(2):32–42. doi: 10.4038/rjs.v7i2.17. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uchoa AMA, Da Costa JMC, Maia GA, Meira TR, Sousa PHM, Brasil IM. Formulation and physicochemical and sensorial evaluation of biscuit-type cookies supplemented with fruit powders. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2009;64(2):153–159. doi: 10.1007/s11130-009-0118-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uthumporn U, Woo WL, Tajul AY, Fazilah A. Physico-chemical and nutritional evaluation of cookies with different levels of eggplant flour substitution. CyTA-J Food. 2015;13(2):220–226. doi: 10.1080/19476337.2014.942700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wani TA, Sood M. Effect of incorporation of cauliflower leaf powder on sensory and nutritional composition of malted wheat biscuits. African J Biotech. 2014;13(9):1019–1026. doi: 10.5897/AJB12.2346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yusufu PA, Netala J, Opega JL (2016) Chemical, sensory and microbiological properties of cookies produced from maize, African yam bean and plantain composite flour. Indian J Nutri 3(1):122–127. https://www.opensciencepublications.com/fulltextarticles/IJN-2395-2326-3-122.html. Accessed on 12th August, 2020