Abstract

The current study aimed to monitor the physicochemical, microbiological quality and sensory profile of pumpkin jam enriched with different proportions of honey, for an interval of 20 days during two months storage period. For that purpose, five jam samples were prepared; the first sample (A) is a control jam without addition of honey, the other four formulations B, C, D and E were prepared by replacing the granulated sugar with honey in different proportions of 5, 10, 15 and 20%, respectively. A decrease was observed in pH from 4.43 to 4.28, °Brix from 45.7 to 42.30%, except the sample C (fortified with 10% of honey) which showed Brix stability during storage; an increase in moisture content from 35.40 to 35.91%, titratable acidity from 1.163 to 1.179% was noted during evaluation. Microbiological examinations indicate that jams were microbiologically stable according to standards in force as all the count of the germs sought revealed lower loads and the total absence of pathogenic germs up to 60 days of refrigerated storage. The appreciation of jams by tasters tended to decrease towards the end of storage, where, on a hedonic scale of 5 points, the scores exhibited values between 1.3 and 3.6.

Keywords: Curcubita pepo, Jam, Honey, Quality analysis, Refrigerated storage

1. Introduction

Fruits and vegetables play an important role in the human body due to their natural richness in nutrients and bioactive compounds (Mazzoni et al. 2021). Indeed, fruits provide minerals, particularly potassium and vitamins, especially vitamin C necessary for the proper functioning of the human body (Mazzoni et al. 2021). However, the problem that arises with the fruits is their shelf life during storage, which is relatively short, which limits the availability of the fruit throughout the year, depending on the climate (FAO 2021). The most interesting evaluation from producers is the fresh marketing at the production sites, but this marketing mode does not take into account all the production, which is the source of considerable economic losses. After that, it is useful to process the fruits into other products such as canned food, syrup, jam, jelly and dried fruits. According to Salehi et al. (2019), the pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) is local to Northern Mexico and Southwestern and eastern USA and is considered as one of the most seasoned and developed varieties, by Mexican archeological evidence of 7000 BC. Cucurbita pepo is a fruit more commonly consumed in North America. The pumpkin is a fruit of high nutritional value, it contains high levels of total proteins (7.25 mg/g FW) and total sugar (90.1 mg/g FW) (Sharma and Ramana Rao 2013), crude fiber (11.463%), vitamins (C, B1 and folates) and total ash (15.988%) (with minerals K, Ca, Mg, Na, Fe, Zn, Cu, P and Mn) (Kulczynski and Gramza-Michałowsk 2019). The pumpkin is an excellent source of carotenoïds with its orange color denoting high content of β-carotene that is converted, after consumption, by the organism into vitamin A (Pereira et al. 2020). Indeed, Dinu et al. (2016) reported carotene levels ranging between 4.2 and 6.587 mg/100 g, as well as Sharma and Ramana Rao (2013) who reported carotenoïds levels of 7.47 mg/100 g. Furthermore, several previous works have noted the presence of molecules with biological activities in the pumpkin such as tocopherols, polyphenols, phenolic acids and flavonols with high antioxidant potential of the pumpkin as it has been demonstrated in the works of (Kulczynski and Gramza-Michałowsk (2019). However, because the majority of the Algerian populace being unaware of its high nutritional value due to the perception that it is a traditional food, the pumpkin is still unexplored. The cultivation of the pumpkins is inexpensive with a high yield. Although, the fruits can be preserved up to 3 months after harvest, they become sensitive to microbial deterioration with loss in moisture and color changes after peeling given the water content, which can exceed 92% as stated by El-Khatib and Muhieddine (2020), so, there is therefore a real concern for its conservation. Therefore, processing of pumpkin can transform it into more stable products that can be beneficial and attractive to both consumers and food industries with longer shelf-life. Pumpkins can be consumed in various ways, whether fresh, canned, frozen, or dried and as juice, nectar, jelly or jam. It is known that jams are very caloric food products given the large sugar quantity usually used, mainly sucrose, during the preparation. However, considerable sucrose consumption has been associated with harmful effects on health, such as cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity and hypertension. In this context, studies have been carried out on sugar substitutes to develop dietetic foods and to improve their organoleptic and physical characteristics (Vaseghi et al. 2020). Thus, this current study aimed to process the local pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) into an organic, dietetic and functional jam of which, part of the sugar has been replaced by natural honey in different formulations. The physicochemical, microbiological and organoleptic qualities of the jams produced were monitored for eight weeks (60 days) of refrigerated storage at 4 ± 2 °C. It must be noted that there are little data regarding the jam made from pumpkin fruit and no data relating to jam made with the addition of honey in partial replacement of sugar. This work is of great relevance because many regions of Algeria, as well as another part of the world, are pumpkin producers in considerable quantities. Thus, the processing of this fruit will be of economic importance for these countries.

Material and methods

Plant material

The Cucurbita pepo (pumpkin) used in this study was harvested on February 22, 2021 from a family garden in the region of El-Ayoun, El-Tarf (Algerian-Tunisian border). The fruit was taken at random from the center of the garden. The pumpkin was orange in color, oval in shape, with a weight of 11 kg. The length and width of the fruit were 92 and 53 cm, respectively, with a length / width ratio of 1.74.

Honey

The honey was purchased at the beekeeping training center of Bouhadjar, El-Tarf (Algeria). The pH, humidity, density, sucrose content and refractive index of honey were 6.52, 22%, 1.35, 5.7% and 1.4815, respectively.

Preparation of jam’ formulations

The preparation of the jam was made according to a recipe including fruit with sugar, with a modification relating to the addition of honey in different proportions (Table 1). Pumpkin was washed, peeled, halved and the seeds have been removed; the resulted pulp was cut into small cubes and then boiled with a sufficient quantity of sugar to a reasonably thick consistency, firm enough to hold fruit issues in position.

Table 1.

Experimental design of pumpkin jam formulations

| Formulation | Pumpkin pulp (g) | Sugar (g) | Honey (g) | Citric acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample A (Control treatment) | 400 | 200 | – | Juice of one lemon |

| Sample B | 400 | 190 | 10 | Juice of one lemon |

| Sample C | 400 | 180 | 20 | Juice of one lemon |

| Sample D | 400 | 170 | 30 | Juice of one lemon |

| Sample E | 400 | 160 | 40 | Juice of one lemon |

In all, 25 jars of jam were prepared, divided into five batches, each lot contains 5 jars, one of which is intended exclusively for microbiological analysis. Honey fortified jams and control jam were analyzed fresh (D0) and after every 20 days (D20, D40, D60) for a storage period of 2 months (60 days) at 4 ± 2 °C. At each sampling day, physicochemical and sensory analysis was carried out and the microbiological survey was carried out at the first (D0) and the last day (D60) of refrigerated storage.

Determination of physicochemical quality

The pumpkin jam was studied to determine the following parameters: the pH of jam samples was measured using a CRISON pH-meter and the result was read directly in pH units at nearest 0.05 pH units (NF V05-108). The titratable acidity was determined by titration with sodium hydroxide (0.1 N NaOH) of 25 g of jam dissolved in 50 mL of distilled water. The point of neutrality was reached when the coloured indicator (phenolphthalein) turned pink. The results were expressed in % of citric acid (NF V05-101); the moisture of jam samples was determined by drying 5 g of jam in an oven at 105 °C for 24 h by subtracting the dry matter content from 100 and the results were expressed in a percentage (%) (NF V03-601). Total ash content was estimated by incineration of a jam test portion at 550 ± 15 °C in an electrically heated muffle furnace, until a whitish residue of constant weight was obtained (NF V03-601) and finally, the rate of soluble solids (TSS%), also expressed in degrees Brix (°Brix), was assessed using Abbé's refractometer from the refractive index of the sample at a temperature of 20 °C. The result was obtained by multiplying the value read directly on the Brix scale of the refractometer by the dilution factor (ISO 2173).

Determination of microbial load

The microbiological control of the pumpkin jam is carried out according to the general guidelines of the Algerian standard published in the Official Journal of Algerian Republic (OJAR) n° 39 of July 2, 2017 relating to the microbiological criteria applicable to foodstuffs. Jam samples were analyzed for total aerobic microbial, total coliforms, coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella in 25 g, yeasts and molds. Table 2 summarizes all of the germs sought and counted according to the standard in force.

Table 2.

Microbiological analyses

| Germs sought | Culture media | Incubation Temperature °C | Incubation time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total aerobic microbial | Bromocresol purple lactose broth | 30 | 24 h |

| Total coliforms | Desoxycholate | 37 | 24 h |

| Coagulase positive Staphylococcus aureus | Chapman | 37 | 24/48 h |

| Salmonelles in 25 g | Hektoen | 37 | 72 h |

| Yeasts and molds | Sabouraud | 20 | 2–5 days |

Organoleptic assessment

Organoleptic evaluation was performed every 20 days until 60 days by recruiting 40 untrained subjects of both sex whose age range from 21 to 52 years old. The test was carried out at the approved private laboratory for food quality control and compliance, El-Bouni -Annaba – Algeria, in a fitting illumination. The sample range is served at room temperature (20 and 25 °C). The tasters were called upon to evaluate the jams prepared in relation to their texture, color, aroma, flavour and viscosity as well as their overall preference having also been estimated. Each parameter tested was evaluated by a score, according to a metric scale of a five-point (1 = dislike very much, 2 = dislike a little, 3 = neither like nor dislike, 4 = like a little, and 5 = like very much) (Milani et al. 2020). Results were subjected to analysis of variance in order to determine the possible differences existing between the aforementioned attributes of jams.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with Microsoft Office Excel 2007 for the measure of means and standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) was carried out using Minitab version 17 Software (Minitab Inc., State College, PA, United States) in order to compare means and to highlight significant differences between the jams produced. Statistical significance was defined at p < 0.05 (α = 0.05).

Results and discussion

Physicochemical characteristics of jams

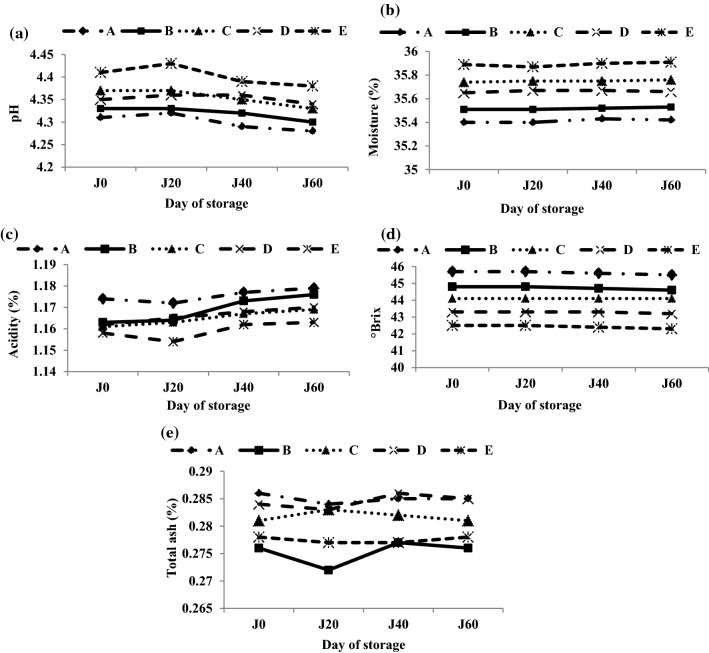

Evolution, during storage, of pH, acidity, moisture, TSS (°Brix) and total ash of prepared jams are illustrated in Fig. 1. Few data were available on the physicochemical parameters of pumpkin jam, although all fruits can be processed into jam, which makes comparison very difficult. So, most of the comparisons were made with results obtained on jam made from other fruits.

Fig. 1.

Evolution of (a): pH; (b): Moisture; (c): Acidity; (d): °Brix and (e): Total ash of Control jam (A), 5% Honey fortified jam (B), 10% Honey fortified jam (C), 15% Honey fortified jam (D) and 20% Honey fortified jam (E) during storage

The pH is a very important parameter since it determines, in part, the aptitude of foods to be preserved. Besbes et al. (2009) stated that the pH of jams must be superior to 3.5 units (> 3.5), since and according to the same authors, a very low pH can induce a deterioration of the sensory quality: crystallization of glucose; granular texture; excessive acidic flavor; and especially the phenomenon of exudation. The pH of the jam samples varied between 4.28 and 4.43 (Fig. 1a) and it is noted that the pH tends to decrease from the first to the last day of storage where the lowest value (4.28) was recorded in the control sample. However, in general the pH tends to increase as the amount of honey increased possibly due to the pH of the honey which was 6.52 contributing to a rise in jam pH. A decrease in pH (3.52–3.28) during 28 days of storage of low-calorie apple jam by using stevia as a sweetener, was obtained by Sutwal et al. (2019). Wasif et al. (2015) also arrived at the same result on apple olive blended jam, who observed a decrease in pH from 3.57 to 3.40 during three months of storage. The diminution of pH values occurring during storage might be due to formation of hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) by hydration of sugar during processing and storage leading to conversion of HMF into levulinic and formic acids as explained by Rababah et al. (2011) and / or can be due to the degradation of ascorbic acid or hydrolysis of pectin as reported by Mudasir and Anju (2018) in pumpkin-guava jam.

As for the moisture content, it varied between 35.40% and 35.91% (Fig. 1b). The moisture content is of great importance for the technological, microbiological and nutritional properties of agri-food products and interests regulatory and economic aspects. From Fig. 1b, it can be seen that the moisture content increases as the storage period lengthens and as the quantity of honey increases. Moisture content fluctuations recorded might be due to the heating process involved in processing as well as the moisture content of honey (22%). By comparing the moisture content of our jams (35.40–35.91%) with those found by Naeem et al. (2017) for fruit jams (strawberry, apricot, and blueberry (31.23–33.36%)), we find that our jams are the moistest. Whereas, the outcomes were close to the results of Sutwal et al. (2019) which were in the range on 32.4–34.00% on Apple jam prepared with sucrose.

The content of organic acids (citric, malic, tartaric acids, etc.) grouped under the term “acidity” denotes the maturity of the fruit (it lowers during maturation). The acidity of a jam directly reflects its acceptability by the consumer and its shelf life. The measured values of titratable acidity over storage time are illustrated in Fig. 1c. As expected, the acidity showed an opposite tendency to that observed for the pH. The acidity increased as the storage period lengthened from D0 to D60. Indeed, the initial acidity of samples A, B, C, D and E were 1.174%,1.163%, 1.161%, 1.162% and 1.158% which increased to 1.179%, 1.176%, 1.169%, 1.170% and 1.163%, respectively. According to Sutwal et al. (2019), the increase in acidity could be due to the formation of organic acids due to the degradation of polysaccharides and the disruption of pectic bodies. The outcomes are correlated with the works of Rana et al. (2021) for coconut and pineapple pulps jam who noted that acidity content increased gradually upon extension of storage period (6 months); and the work of Sutwal et al. (2019) for apple jam upon storage period of 28 days. Also, for the same day, it has been noted that the more the quantity of honey increases, the acidity decreases which can be explained by the rate of organic acids provided by honey namely xalic, L-tartaric, D-quinic, L-malic, L-ascorbic, citric, fumaric and succinic.

Brix degree (°Brix) or total soluble solids of fruits and fruit products represent various constituents present in soluble form, including sugars. For all the jam samples, the °Brix was between 42.30 and 45.7%. The °Brix of all jam samples tend to decrease slightly with storage and with the amount of honey added (Fig. 1d), except sample C (10% honey jam) which showed a ° Brix stability throughout storage. This situation can be explained by the presence of honey, which generated a dilution effect. A high ° Brix values were previously recorded by Benmeziane et al. (2018) and Touati et al. (2014) of 73.10° Brix and 64.42° Brix on melon and industrial apricot jam, respectively. Touati et al. (2014) evidenced that the TSS changes were not significant (p ˃ 0.05) by storage time, temperature or the interaction between those factors.

The amount of minerals such as calcium, phosphorus and iron present in the sample depicts the total ash content. The initial total ash contents of jam were 0.286%, 0.276%, 0.281%, 0.284% and 0.278% for jams A, B, C, D and E, respectively (Fig. 1e). After two months of storage, those rates were, respectively of 0.285%, 0.276%, 0.281%, 0.285% and 0.278% for jams A, B, C, D and E. The results of the current study were lower than the 0.30–0.37% reported by Rana et al. (2021) on mixed fruit jam, the 3.11 g/100 g noted by Alsuhaibani and Al-Kuraieefon (2018) on pumpkin jam; and higher than the 0.20% found by Benmeziane et al. (2018) on melon jam and 0.12–0.25% reported by Naeem et al. (2017) on different fruit jams (grape, apricot, blueberry and strawberry). Nwosu et al. (2014), stated that the variation in ash content is due to the variation in inorganic compounds especially calcium ion present in pectin of the different fruits. It turns out that the addition of honey had a very variable effect on the total ash content of jams where there were increases and decreases in ash with the addition of different amounts of honey. The levels recorded for jams B, C and E tend to stabilize towards the end of the 60 days storage period.

Changes in physicochemical quality over storage time

It was found that the storage time has a significant effect on the jam physicochemical quality (pH, °Brix, ash and moisture) except on the titratable acidity where no significant differences (p˃0.05) were detected over the storage time. The average pH of the jams produced varied between 4.30 and 4.40 (60 days) with a respective drop of 0.7%, 0.7%, 0.92%, 0.23% and 0.7% for A, B, C, D and E samples as shown in Table 3. The pH in the present study is classified as acidic (pH between 4.0 and 4.5) instigating an inhibitory effect on microorganisms growth and increasing the useful life of aliments as stated previously by Brandão et al. (2018). According to Wasif et al. (2015), the hydrolysis of pectic matter into pectenic acid and the formation of acidic compounds during the degradation of the sugar content may explain the drop in pH during storage. The storage time did not affect significantly (p > 0.05) the titratable acidity of jams, which averaged between 1.16 and 1.32% with respective raises of 0.42%, 1.12%, 0.68%, 0.68% and 0.43% for A, B, C, D and E samples (Table 3). Damiani et al. (2012) have observed that mixed marolo and araça jam pH presented a slight decrease from 3.31 to 3.27 during the first 6 months of storage and after 12 months, the pH increased to 3.33 and a slight increase in the total acidity from 1.17 to 1.27%, probably due to the accumulation of other organic acids (shikimic, fumaric, oxalic, lactic, propionic) during storage then returning to the original value of 1.18% at the end of the experiment. Conversely, Brandão et al. (2018) observed pH stability in cerrado fruit jam during storage for 180 days. The time also significantly affected (p < 0.05) the moisture content. Indeed, increases of 0.06%, 0.06%, 0.06, 0.03% and 0.06% were noted, respectively for jams A, B, C, D and E during storage as shown in Table 3. The outcomes were contradictory to those of Damiani et al. (2012) who observed a drop of approximately 27% in mixed araça and marolo jam during one year of storage. The authors have explained their results by the exchange of moisture between the inside and outside of the glass by desorption, the super junction chains forming the gel, thus trapping the free water and to a lesser extent, the Maillard reaction, which occurs at high temperatures in high-sugar products with low pH values using the water-free environment.

Table 3.

Means of the physicochemical properties of different jam formulations during all the storage period (up to 60 days)

| Formulation | A | B | C | D | E |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH |

4.30 ± 0.02c (− 0.7%) |

4.32 ± 0.014c (− 0.7%) |

4.36 ± 0.02b (− 0.92%) |

4.35 ± 0.01b (− 0.23%) |

4.40 ± 0.02a (− 0.7%) |

| Acidity (%) |

1.18 ± 0.03a (+ 0.42%) |

1.17 ± 0.01a (+ 1.12%) |

1.32 ± 0.3a (+ 0.68%) |

1.17 ± 0.04a (+ 0.68%) |

1.16 ± 0.04a (+ 0.43%) |

| Moisture (%) |

35.41 ± 0.02e (+ 0.06%) |

35.52 ± 0.01d (+ 0.06%) |

35.75 ± 0.01b (+ 0.06%) |

35.66 ± 0.01c (+ 0.03%) |

35.89 ± 0.02a (+ 0.06%) |

| Total soluble solids (°Brix) |

45.63 ± 0.1a (− 0.44%) |

44.73 ± 0.1b (− 0.47%) |

44.10 ± 0.00c (0%) |

43.28 ± 0.05d (− 0.23%) |

41.43 ± 0.1e (− 0.47%) |

| Total ash (%) |

0.285 ± 0.001a (-0.35%) |

0.275 ± 0.02d (0%) |

0.282 ± 0.001b (0%) |

0.285 ± 0.001a (+ 0.35%) |

0.278 ± 0.001c (0%) |

Different letters in the same line indicate significant differences (p < 0.05); Results are ranked in descending order: a>b>c>d>e

The values in brackets indicate the rate of increase/decrease between the first and the last day of storage;

( +): increase; (−): decrease

A: Control jam (without honey)

B: 5% Honey fortified jam

C: 10% Honey fortified jam

D: 15% Honey fortified jam

E: 20% Honey fortified jam

Statistical analysis revealed that the effect of storage on total soluble solids (°Brix) of different pumpkin jam were statistically significant (p < 0.05). In fact, a slight drop of 0.44%, 0.47%, 0.23% and 0.27% were observed for respectively, the A, B, D and E samples (Table 3). While, no changes were observed for the C sample (jam prepared with the addition of 10% of honey). Kanwal et al. (2017) indicated a significant effect of storage time for 60 days on the total soluble solids of the guava jam but with an increase during storage. The authors attributed this increase to acid hydrolysis of polysaccharides especially pectin and gums and to solubilization of jam ingredients or components throughout storage. An opposite trend, comparing to results of the current study, was recorded by Nafri et al. (2021) on ripe papaya jam who stated that prior to storage, the total soluble solids value of jam was 63°Brix, and the storage increased the °Brix value to 65 and 68.3° Brix at low and room temperature, respectively. The same trend of the total soluble solids raising was observed by Rana et al. (2021) after 6 months of storage, they explained this increase by the formation of mono and disaccharides resulted from hydrolysis of polysaccharides. From the results shown in Table 3, it is evident that storage time affected significantly (p < 0.05) the total ash contents as a rise of 0.35% up to 60 days of storage was noted for the 15% honey fortified jam. At the opposite, a drop with the same percentage (0.35%) was observed for sample A (control jam). The current results were not in line with the findings of Damiani et al. (2012) who indicated that storage for 12 months did not affect the ash content of a mixed araça and marolo jam, which averaged 0.20%. In general, low ash content recorded in the current study denotes that the homemade pumpkin jam analyzed is not a rich source of minerals.

Microbiological quality

The results of the microbial counts on the freshly produced jams as well as at the end of storage (D60) are presented in Table 4. It seems that the quantity of honey added has a variable effect on the microbiological criteria of the jams. Indeed, the microbial loads in terms of total aerobic microbial and total coliforms increased or decreased independently with the percentage of added honey. However, the count of these bacterial groups has raised considerably from the first day of production until the end of storage, without exceeding the standards dictated in the official journal of the Algerian Republic relating to the microbiological criteria of foodstuffs. Pramanick et al. (2014) have stated that jams and jellies properly prepared and packaged are free from bacteria and yeast cells until the lid is opened and exposed to air; this did not agree with the results of the present study which can be explained by the artisanal preparation of our jams which caused contamination during preparation. With regard to pathogens, Coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella were not detected after a storage period of two months. The same situation was noted for yeasts and molds for all freshly produced samples, nevertheless, at the end of storage, a few colonies appeared on samples A, C, D and E. The banana jams stored at 25 °C had developed mold by day 7. However, some banana jams developed molds in a shorter time due to differences in the amount of sugar and acidity of the jams. In contrast, the banana jams stored at 4 °C remained in good condition with no molds until day 14. At 4 °C, lower water activity and higher total soluble solids (sugar content) in the banana jams contributed to prolonging the shelf life of the jams (Wan-Mohtar et al. 2021). Overall and according to the standards of the official journal (2017), the jams produced were of satisfactory microbiological quality. The intense heat application involved in jam production, the cooking time as well as the low pH and the osmotic pressure exerted by the sugar contribute to the hygienic quality of the product and prevent microbial spoilage (Pramanick et al. 2014). Our findings agree with previous investigations of Benmeziane et al. (2018) who reported no fungi growth in a melon jam after four months of storage. Concerning the evolution of microbial loads, our results were not in agreement with those of Nafri et al. (2021) who reported that during storage no significant increase in microbial load was observed in the ripe and unripe papaya jam after 60 days of refrigerated storage.

Table 4.

Microbiological quality of the produced jams

| Storage day | D0 | D60 | Microbiological limits (UFC/g) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | A | B | C | D | E | ||

| Total aerobic microbial (UFC/g) | 3.3 × 103 | 1.6 × 102 | 2.4 × 102 | 1.1 × 102 | 2.8 × 102 | 7.2 × 103 | 4.8 × 103 | 3.1 × 104 | 8.2 × 103 | 5.6 × 104 | 104–105 |

| Total coliforms (UFC/g) | 36 | 16 | 22 | 16 | 12 | 38 | 72 | 4.1 × 102 | 2.2 × 102 | 1.8 × 102 | 102–103 |

| Coagulase positive staphylococci (UFC/g) | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | 10–102 |

| Salmonella in 25 g (UFC/g) | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Absence in 25 g |

| Yeasts and molds (UFC/g) | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | Abs | 1 | Abs | 4 | 2 | 3 | 102–103 |

A: Control jam (without honey)

B: 5% Honey fortified jam

C: 10% Honey fortified jam

D: 15% Honey fortified jam

E: 20% Honey fortified jam

Sensory evaluation

As in all foods, the organoleptic qualities are generally the final guide of the quality from the consumer’s point of view. Overall, all scores assigned for all jams (control and jam incorporated with honey) were less than 4, with the exception of sample A for its overall acceptability and sample D for its texture which received a score of 4 and 4.2, respectively at the 40th storage day. This situation can be due to that taster are not used to consuming a pumpkin-based jam which greatly influenced their appreciations which had repercussions on their acceptance of the distinctive characteristics of these new jams as stated by Alsuhaibani and Al-Kuraieef (2018). Our observations did not meet that of Awad and Shokry (2018) in their evaluation of the sensory characteristics of pumpkin jam where high sensory scores were observed for control (pumpkin jam) and other treatments (pumpkin jam with orange juice) with overall acceptability scores varying between 8.5 and 8.9, on a 9-point hedonic scale. As it can be seen from the results of Table 5, no significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed in the flavor of jams except at the end of the storage (D60), where significant differences (p < 0.05) were noted for samples C, D and E which were the least appreciated with respective scores of 1.6, 1.4 and 1.5. As for the viscosity, significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed between the samples up to the 20th day of storage, beyond which no difference was recorded between the jams. The panelists were much more indifferent or they did not like much the viscosity of the honey fortified pumpkin jams as well as the control jam. The tasters' assessments for samples C and D (with respectively 10% and 15% added honey) decreased as the storage period lengthened. The addition of 20% honey in the jam did not significantly influence (p > 0.05) the tasters' assessments for texture, color, aroma, viscosity and overall acceptability, except for the flavor where the scores decreased from 3 on the first day (D0) to 1.5 on the last day of storage (D60). As a result of their thicken texture and reduced water activity, jams are stable and can be conserved for a relatively prolonged time; nonetheless, during storage, some changes occur in their characteristics, such as color, aroma, and flavor that can affect the consumer acceptance. The sensory properties of jams depend mainly on their components, particularly the variety of pumpkin and even on its stage of maturity (Alsuhaibani and Al-Kuraieef, 2018). However, the tasters' responses to the different organoleptic qualities evaluated in the jams produced varied very widely throughout the storage period, which explains the scores recorded on the sensory attributes. Similar results were also observed in a study conducted by Adedeji (2017) in their evaluation of the sensory characteristics of watermelon-pawpaw blended jam. In addition, the study of Chauhan et al. (2011) on the sensory evaluation of osmo-dried apple slices indicated that sucrose-treated slices had significantly (p < 0.05) higher values for all the sensory attributes studied (color, appearance, aroma, taste, texture and overall acceptability) than other samples treated with honey, glucose, sorbitol, fructose and maltose. Honey-treated samples showed significantly (p < 0.05) lower color and texture values as compared to other samples as it possessed brown color and leathery texture. Touati et al. (2014) noted that despite a decrease in overall acceptability scores at 37 °C, data indicated that sensorial panel of the apricot jam remained appreciative.

Table 5.

Effect of storage time on the sensory attributes of different pumpkin jam formulations

| Storage day | D0 | D20 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jam sample / Sensory attributes | A | B | C | D | E | A | B | C | D | E |

| Texture | 3.4 ± 1.17a,b, A | 3.8 ± 1.03a,A | 3.3 ± 1.25a,b,c,A | 2.2 ± 1.40c,B | 2.3 ± 1.70b,c,A | 3.3 ± 1.25a, A | 3.50 ± 1.27a,A,B | 2.9 ± 1.10a,A,B | 3.00 ± 1.70a,A,B | 2.3 ± 1.70a,A |

| Color | 4 ± 0.82a, A | 2.7 ± 1.49b,B | 3.2 ± 1.14a,b,A,B | 2.6 ± 1.35b,A | 2.5 ± 1.84b,A | 3.00 ± 0.94a,b, B | 2.40 ± 1.35b,A | 2.7 ± 1.25a,b,B | 2.7 ± 1.70b,A | 3.9 ± 1.45a,A |

| Aroma | 3.2 ± 1.62a,b, A,B | 3.6 ± 1.26a,A | 3.3 ± 1.70a,b,A | 2.8 ± 0.63a,b,A | 2.1 ± 1.45b,A | 3.40 ± 1.17a, A | 2.9 ± 1.20a,b,A | 3.4 ± 1.58a,A | 3.2 ± 1.14a,b,A | 2.1 ± 1.79b,A |

| Flavour | 2.9 ± 1.45a, A,B | 3.6 ± 1.43a,A | 2.4 ± 1.17a,A,B | 3.1 ± 1.29a,A | 3 ± 1.76a,A | 2.40 ± 0.84a, B | 3.2 ± 1.32a,A | 2.9 ± 1.20a,A | 3.00 ± 1.83a,A | 3.5 ± 1.78a,A |

| Viscosity | 3.8 ± 1.14a, A | 3.5 ± 1.08a,b,A | 3.8 ± 0.63a,A | 2.6 ± 1.71b,A,B | 1.3 ± 0.48b,A | 3.7 ± 1.49a, A | 3.14 ± 0.99a,A,B | 3.1 ± 1.45a,A,B | 3.5 ± 1.35a,A | 1.6 ± 0.97b,A |

| Overall acceptability | 3.4 ± 1.43a, A,B | 3.3 ± 1.34a,b,A | 3.5 ± 1.43a,A | 2.7 ± 1.42a,b,A,B | 2.1 ± 1.29b,A | 2.7 ± 1.06a,b,B | 2.7 ± 0.82a,b,A | 3.7 ± 1.64a,A | 3.8 ± 1.55a,A | 2.1 ± 1.37b,A |

| Storage day | D40 | D60 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jam sample / Sensory attributes | A | B | C | D | E | A | B | C | D | E |

| Texture | 3.8 ± 1.48a,b, A | 2.6 ± 1.07b,B | 3.2 ± 1.40a,b,A | 4.2 ± 0.79a,A | 2.6 ± 1.84b,A | 3 ± 1.56a, A | 3.3 ± 1.06a,A,B | 2.1 ± 0.99a,B | 2.8 ± 1.40a,B | 2.1 ± 1.60a,A |

| Color | 3.3 ± 1.25a,b, A,B | 3.9 ± 0.99a,B | 3.7 ± 0.82a,b,A | 2.6 ± 1.84b,A | 3.1 ± 1.91a,b,A | 3.3 ± 1.16a,b, A, B | 3.5 ± 1.18a,b,A,B | 2.5 ± 0.97a,b,B | 3.4 ± 1.35a,A | 2.4 ± 1.58b,A |

| Aroma | 2.6 ± 1.43a, B,C | 2.6 ± 1.64a,A | 3.5 ± 1.08a,A | 3 ± 1.49a,A | 2.5 ± 1.72a,A | 1.6 ± 0.52b, C | 2.8 ± 0.63a,A | 1.5 ± 0.53b,B | 1.5 ± 0.71b,B | 1.3 ± 0.45b,A |

| Flavour | 3.6 ± 1.35a, A | 3.4 ± 1.07a,A | 2.8 ± 1.40a,A | 3.2 ± 1.62a,A | 2.8 ± 1.75a,A,B | 3.1 ± 1.1a, A,B | 3.6 ± 0.70a,A | 1.6 ± 0.70b,B | 1.4 ± 0.52b,B | 1.5 ± 0.53b,B |

| Viscosity | 3 ± 1.56a, A | 2.5 ± 1.18a,B | 3 ± 1.05a,A,B | 3.2 ± 1.03a,A,B | 2.9 ± 1.60a,A | 2.7 ± 1.16a, A | 3 ± 1.05a,A,B | 2.4 ± 0.70a,B | 2.2 ± 1.23a,B | 2.5 ± 1.35a,A |

| Overall acceptability | 4 ± 1.25a, A | 3.4 ± 1.43a,b,A | 3.3 ± 1.25a,b,A | 2.4 ± 1.43b,c,B | 1.7 ± 0.82c,A | 2.6 ± 0.84b,B | 3.6 ± 0.52a,A | 1.6 ± 0.52c,B | 1.6 ± 0.70c,B | 1.5 ± 0.71c,A |

Different letters in the same row indicate significant differences (p <0.05); The letters a, b and c: indicate the differences between the five jams on the same day of analysis; The letters A, B and C: indicate differences between the same jam depending on the days of storage; The results are listed in descending order; a > b > c or A > B > C

A: Control jam (without honey);B: 5% Honey fortified jam;C: 10% Honey fortified jam;D: 15% Honey fortified jam;E: 20% Honey fortified jam

Conclusion

This study focused on the development of a pumpkin-based jam and aims both to safeguard the phytogenetic heritage of the region of El-Tarf (Algeria) and to develop a food formulation of biological, energy and healthy. The jams were made with different proportions of sugar and honey; the physicochemical, microbiological and sensory qualities were monitored during two months of storage. The results showed that the pumpkin was advantageously processed into jam and that the honey did not hinder this processing. The jams presented pH varying from 4.28 and 4.43, the titratable acidity was between 1.154 et 1.179%. The Moisture content and the °Brix didn’t exceed 35.91% and 45.7%, respectively. The microbiological quality was satisfactory given the absence of pathogenic germs in terms of Staphylococcus aureus and salmonella as well as yeasts and molds. Sensory analysis confirmed the acceptability of this product by consumers; although scores tended to decrease during storage. The storage period had a significant impact on the prepared pumpkin jams, except the acidity, but their quality remains good and had consumer acceptance. From the overall results it can be concluded that pumpkin has been used advantageously in the manufacture of the jam; which allows its preservation and the reduction of the postharvest loss to provide value added product; So that the growers, processors and consumers can get maximum benefits from their products. Finally, it was found that prepared pumpkin jams stored for two months at cold temperatures were still acceptable.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for its financial support. The authors also thank the Quality Control and Compliance laboratory of Mr Berrahmoune A, El-Bouni –Annaba- Algeria for carrying out the various analyzes.

Author contributions

FBD: idea work, Finalization of this work, the presentation of the results and the interpretation as well as the drafting of the MS; KT and FZM: The realization of the practice; LD-A: orientation of the study.

Funding

Algerian Ministry of Higher Teaching and Scientific Research.

Availability of data and material

Yes, the data are specific to this study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to participate

The product don't present any health hazardous and we took the constent from the panelists for sensory study of product. In addition, the microbiological analysis is done before so to ensure the security of the tasters. In addition, tasters were supportive and interested in participating in the various tasting sessions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adedeji TO. Development and quality evaluation of Jam from Watermelon (Citrullus Lanatus) and Pawpaw (Carica Papaya) juice. Arch Food Nutr Sci. 2017;1:063–071. doi: 10.29328/journal.afns.1001010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alsuhaibani AMAM, Al-Kuraieef AN. Effect of low-calorie pumpkin jams fortified with soybean on diabetic rats: study of chemical and sensory properties. J Food Qual. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/9408715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Awad SMS, Shokry AM. Evaluation of physical and sensory characteristics of jam and cake processed using pumpkin (Cucurbita moschata) Middle East J Appl Sci. 2018;8(2):295–306. [Google Scholar]

- Benmeziane F, Djermoune-Arkoub L, Boudraa AT, Bellaagoune S. Physicochemical characteristics and phytochemical content of jam made from melon (Cucumis melo) Int Food Res J. 2018;25(1):133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Besbes S, Drira L, Blecker C, Deroanne C, Attia H. Adding value to hard date (Phoenix dactylifera L.): compositional, functional and sensory characteristics of date jam. Food Chem. 2009;112(2):406–411. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.05.093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandão TM, Do Carmo EL, Elias HES, De Carvalho EEN, Borges SV, Martins GAS. Physicochemical and microbiological quality of dietetic functional mixed cerrado fruit jam during storage. Sci World J. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/2878215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan OP, Singh A, Singh A, Raju PS, Bawa AS. Effects of osmotic agents on color, textural, structural, thermal, and sensory properties of apple slices. Int J Food Prop. 2011;14(5):1037–1048. doi: 10.1080/10942910903580884. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damiani C, Asquieri ER, Lage ME, Oliveira RA, Silva FA, Pereira DEP, Vilas Boas EVB. Study of the shelf-life of a mixed araça (Psidium guineensis Sw.) and marolo (Annona crassifora Mart.) jam. Food Sci Technol. 2012;32(2):334–343. doi: 10.1590/S0101-20612012005000050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dinu M, Soare R, Hoza G, Becherescu AD. Biochemical composition of some local pumpkin population. Agric Agric Sci Proced. 2016;10:85–191. doi: 10.1016/j.aaspro.2016.09.051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khatib S, Muhieddine M (2020) Nutritional profile and medicinal properties of pumpkin fruit pulp. In: The health benefits of foods - current knowledge and further development. First Edition. Publisher: Intech Open, pp 1–21. 10.5772/intechopen.89274

- FAO . Fruit and vegetables—your dietary essentials. Rome: Background paper,; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kanwal N, Randhawa MA, Iqbal Z. Influence of processing methods and storage on physico-chemical and antioxidant properties of guava jam. Int Food Res J. 2017;24(5):2017–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczynski B, Gramza-Michałowsk A. The profile of secondary metabolites and other bioactive compounds in Cucurbita pepo L. and Cucurbita moschata pumpkin cultivars. Molecules. 2019;24(16):2945. doi: 10.3390/molecules24162945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzoni L, Ariza Fernández MT, Capocasa F. Potential health benefits of fruits and vegetables. Appl Sci. 2021;11:8951. doi: 10.3390/app11198951. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milani A, Jouki M, Rabbani M. Production and characterization of freeze-dried banana slices pretreated with ascorbic acid and quince seed mucilage: physical and functional properties. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8:3768–3776. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mudasir B, Anju B. A study on the physico-chemical characteristics and storage of pumpkin-guava blended jam. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2018;7(3):1180–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Naeem MMN, Fairulnizal MN, Norhayati MK, Zaiton A, Norliza AH, Syuriahti Wan WZ, Azerulazree MJ, Aswir AR, Rusidah S. The nutritional composition of fruit jams in the Malaysian market. J Saudi Soc Agric Sci. 2017;16(1):89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jssas.2015.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nafri P, Singh AK, Sharma A, Sharma I. Effect of storage condition on physiochemical and sensory properties of papaya jam. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2021;10(2):1296–1301. doi: 10.22271/phyto.2021.v10.i2q.13990. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nwosu JN, Udeozor LO, Ogueke CC, Onuegbu N, Omeire GC, Egbueri IS. Extraction and utilization of pectin from purple star-apple (Chrysophyllum cainito) and African star-apple (Chrysophyllum delevoyi) in jam production. Austin J Nutr Food Sci. 2014;1(1):1003–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AM, Krumreich FD, Ramos AH, Krolow ACR, Santos RB, Gularte MR. Physicochemical characterization, carotenoid content and protein digestibility of pumpkin access flours for food application. Food Sci Technol. 2020;40(Suppl. 2):691–698. doi: 10.1590/fst.38819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pramanick P, Zaman S, Mitra A. Processing of fruits with special reference to S. apetala fruit jelly preparation. Int J Univ Pharm Bio Sci. 2014;3(5):36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Rababah TM, Al-Mahasneh MA, Kilani I, Yang W, Alhamad MN, Ereifej K, Al-u’datt M. Effect of jam processing and storage on total phenolics, antioxidant activity, and anthocyanins of different fruits. J Sci Food Agric. 2011;91:1096–1102. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana MS, Yeasmin F, Khan MJ, Riad MH. Evaluation of quality characteristics and storage stability of mixed fruit jam. Food Res. 2021;5(1):225–231. doi: 10.26656/fr.2017.5(1).365. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi B, Sharifi-Rad J, Capanoglu E, Adrar N, Catalkaya G, Shaheen S, Jaffer M, Giri L, Suyal R, Jugran AK, Calina D, Docea AO, Kamiloglu S, Kregiel D, Antolak H, Pawlikowska E, Sen S, Acharya K, Bashiry M, Selamoglu Z, Martorell M, Sharopov F, Martins N, Namiesnik J, Cho WC. Cucurbita plants: from farm to industry. App Sci. 2019;9(16):3387. doi: 10.3390/app9163387. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Ramana Rao TV. Nutritional quality characteristics of pumpkin fruit as revealed by its biochemical analysis. Int Food Res J. 2013;20(5):2309–2316. [Google Scholar]

- Sutwal R, Dhankhar J, Kindu P, Mehla R. Development of low-calorie jam by replacement of sugar with natural sweetener Stevia. Int J Curr Res Rev. 2019;11(4):9–16. doi: 10.31782/IJCRR.2019.11402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Touati N, Tarazona-Díaz MP, Aguayo E, Louaileche H. Effect of storage time and temperature on the physicochemical and sensory characteristics of commercial apricot jam. Food Chem. 2014;145:23–27. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaseghi F, Jouki M, Rabbani M. Investigation of physicochemical and organoleptic properties of low-calorie functional quince jam using pectin, quince seed gum and enzymatic invert sugar. Iran J Nutr Sci Food Technol. 2020;17(106):157–171. doi: 10.52547/fsct.17.106.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wan-Mohtar WAI, Abdul Halim-Lim S, Balamurugan JP, Mohd Saad MZ, Zahia Azizan NA, Jamaludin AA, Ilham Z. Effect of sugar-pectin-citric acid pre-commercialization formulation on the physicochemical, sensory, and shelf-life properties of Musa cavendish banana jam. Sains Malays. 2021;50(5):1329–1342. doi: 10.17576/jsm-2021-5005-13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wasif S, Khan A, Alam Z, Khan MA, Shah FN, Ali M, Shah F, Ul-Amin N, Ayub M, Wahab S, Muhammad A, Khan SH. Quality evaluation and preparation of apple and olive fruit blended jam. Glob J Med Res L Nutr Food Sci. 2015;15(1):15–21. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Yes, the data are specific to this study.