Abstract

Subcellular machinery of NLRP3 is essential for inflammasome assembly and activation. However, the stepwise process and mechanistic basis of NLRP3 engagement with organelles remain unclear. Herein, we demonstrated glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β) as a molecular determinant for the spatiotemporal dynamics of NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Using live cell multispectral time-lapse tracking acquisition, we observed that upon stimuli NLRP3 was transiently associated with mitochondria and subsequently recruited to the Golgi network (TGN) where it was retained for inflammasome assembly. This occurred in relation to the temporal contact of mitochondria to Golgi apparatus. NLRP3 stimuli initiate GSK3β activation with subsequent binding to NLRP3, facilitating NLRP3 recruitment to mitochondria and transition to TGN. GSK3β activation also phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase 2 Α (PI4k2A) in TGN to promote sustained NLRP3 oligomerization. Our study has identified the interplay between GSK3β signaling and the organelles dynamics of NLRP3 required for inflammasome activation and opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Subject terms: Inflammasome, Inflammasome

Inflammasomes are multiprotein cytosolic complexes that serve as a platform for caspase-1-dependent production of several proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18, and constitute a crucial step in the initiation of innate immune responses [1]. Excessive inflammasome activity has been involved in diverse chronic inflammatory diseases, notably including metabolic disorders such as fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes [2]. The NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated by a variety of structurally unrelated molecules ranging from insoluble particulates, endogenous danger signals and pathogen molecules [3–6]. However, these molecule activators do not bind NLRP3 directly and instead converge on a subcellular transport processes and consequent molecular machinery which intensively facilitates NLRP3 inflammasome orchestration [7]. A common theme from recent studies supports that reorganization of the intracellular organelle network is necessary for NLRP3 inflammasome activation, including lipid directed NLRP3 localization to mitochondria, microtubule-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and NLRP3 interaction with Golgi-localized phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate in response to diverse stimuli [5, 8–11]. Nevertheless, the current observations remain inconclusive and the exact sequence of molecular events for NLRP3 inflammasome assembly remains largely unknown [5, 8–11]. Here we investigated the organelle dynamics and molecular requirement for NLRP3 recruitment in live cells. Our observations present a comprehensive model of GSK3β signaling mediated NLRP3 activation resulting in distinct NLRP3 trafficking, organelle reorganization and inflammasome assembly.

Spatiotemporal dynamics of NLRP3 recruitment to mitochondria and subsequent TGN localization upon stimuli

To explore the spatiotemporal coordination of NLRP3 inflammasome components among organelles, Hela cells which lack NLRP3 inflammasome components were co-transfected with constructs expressing fluorescent proteins targeted to mitochondria, Golgi and NLRP3. Images were acquired using point scanning confocal microscopy, and the three fluorophores could be separated into distinct channels. Time-lapse imaging of Z-stacks of 25 × 35 nm slices and 1024 × 1024-pixel resolution captured every 5 min revealed the dynamics of all three labelled targets within single cell (Fig. S1A, B). Live cell images were processed using IMARIS - an imaging informatics pipeline for quantitative analysis of interactions between i) NLRP3-mitochondria, ii) mitochondria-Golgi and iii) NLRP3-Golgi over a 120 min time-course upon NLRP3 stimuli. Using this in vitro time-lapse imaging platform, we have tracked the dynamic subcellular localization of NLRP3. Under resting cell state, NLRP3-GFP was diffused across the cytosol without colocalization with either mitochondria or Golgi (Fig. 1A, t = 0 min). In response to nigericin stimulus, NLRP3-GFP gradually oligomerized as reflected by multiple green puncta formation during the observed course of 120 min (Fig. S1A-, B-1st lane). Golgi-RFP was present diffusely around the pre-nuclear region in resting cells and did not undergo morphological rearrangement after nigericin stimulation (Fig. S1A, B-2nd lane). Active NLRP3-GFP transiently overlapped with mitochondria at approximately 15 min, and subsequently disassociated from mitochondria over 60 min (Fig. 1A-1st lane, 1B, Movies S1). Concurrent with it disassociating from mitochondria, NLRP3 was subsequently aggregated to the Golgi apparatus, initiating at 15 min, forming and retaining contact for the remaining time period (Fig.1A-2nd lane, 1B, Movies S2). Single cell mapping of mitochondrial vesicles and Golgi apparatus revealed that the two organelles were transiently associated within a peak at 15 min providing a spatial basis for the transfer of NLRP3 from mitochondria to the Golgi (Fig. 1A-3rd lane, 1C, Movies S3). Time-lapse trafficking analysis visualized the changes in the contact between NLRP3-mitochondria, NLRP3-Golgi and mitochondria-Golgi demonstrating this sequential movement of NLRP3 from cytosol to mitochondria, and then to Golgi (Fig. 1D). This was further revealed by three-dimensional (3D) visualization in dynamic changes of NLRP3 trafficking from mitochondria to Golgi (Fig. S2). The use of Golgi-RFP generally detects both the trans and medial components of the Golgi stack. To identify the specific compartment of Golgi apparatus association with NLRP3, subcellular protein fractionation combined with immunoblotting was performed and showed that NLRP3 was predominantly localized at the Trans- but not Cis-Golgi portion after nigericin stimulation (Fig. 1E, F). Identical NLRP3 recruitment to mitochondria and subsequent Trans-Golgi network (TGN) were confirmed in mouse primary bone-marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) in response to NLRP3 stimuli (Fig. 2A–C). To further gain insight into these changes at the macromolecular level, we observed mitochondria organelle-Golgi apparatus contact in a dynamic fashion by transmission electron microscopy. Consistently, mitochondria were localized adjacent to points where Golgi apparatus localized at 5 min after NLRP3 inflammasome stimuli and were separated at 10 min (Fig. 2D). Collectively, these results indicate that signal-dependent NLRP3 recruitment to TGN occurred in physiologically relevant cells and preceded the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. Given the primary role of microtubules in organizing organelles and inter-organelle contacts [12], we next demonstrated a requirement for microtubule activity for the requirement of NLRP3 to Golgi (Fig. S3), which is consistent with previous reports that microtubule function is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation [9].

Fig. 1. Sequential localization of NLRP3 to the mitochondria, association of mitochondria with TGN, and NLRP3 recruitment to TGN.

HeLa cells expressing fluorescent fusion proteins NLRP3-GFP (green), TOM20-mPLUM (red) and Golgi-RFP (CellLightTM) (yellow) were stimulated with nigericin. The time-lapse imaging of live cells was captured every 5 min over the course of 120 min. A Representative snapshot images of NLRP3 dynamic contact with mitochondria and Golgi, and mitochondrial dynamic contact with Golgi were determined by fluorescence merge and colocalization analysis. All the panels represent images acquired from the same cell at various time points. The white pixel intensities show corresponding Z-slices with optimal colocalization over 2 channels obtained from Imaris 9.2.1- colocalization plugin. Scale bar 10 µm. B, C The levels of colocalized pixels between NLRP3 and mitochondria, NLRP3 and Golgi (B), and mitochondria and Golgi vesicles (C) were quantified using Image J. Three biological replicates were analyzed. The error bar indicates SEM. D Time-lapse tracking analysis of NLRP3 dynamic contact with mitochondria and Golgi, and mitochondrial dynamic contact with Golgi. E, F Immunoblot analysis of dynamic NLRP3 protein levels in Trans- (E) and Cis- (F) Golgi fractions that were fractionated from Hela cells expressing NLRP3 with nigericin stimulus as indicated time-course. Purity of the fractions was assessed by blotting for GM130 (Cis-), TGN38 (Trans-), and Tom20 (mitochondria).

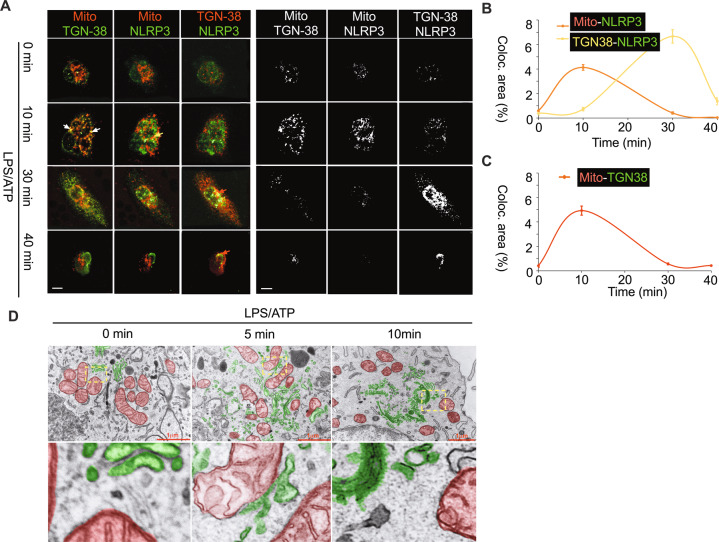

Fig. 2. Subcellular trafficking of NLRP3 in primary mouse BMDMs upon stimulus.

A Representative confocal images of mitochondria-TGN38, mitochondria-NLRP3 and NLRP3-TGN38 contact during 0, 10, 30 and 40 min after LPS/ATP in primary mouse BMDMs. Each 2-channel interaction was false colored and shown as red-green combo. The right panel shows corresponding colocalization pixels of the images on left panel as quantified using Image J. B Quantification of mitochondria-NLRP3 and TGN38-NLRP3 colocalization. C Quantification of mitochondria-TGN38 colocalization. D Electron micrograph shows dynamic contact between mitochondria and Golgi during 0, 5, and 10 min after LPS/ATP stimulation in primary mouse BMDMs. The TEM images were false colored to highlight mitochondria (red) and Golgi structures (green). At least 8 cells were randomly imaged per group per experiment. Scale bar = 10 μm. Data represent the mean +/- SD of three independent experiments.

A requirement of GSK3β signals for NLRP3 recruitment to subcellular organelles upon stimuli

Activation of immune pathways results in major metabolic demands on innate immune cells. A close integration of the immune and metabolic responses is well recognized but how this is achieved in NLRP3 activation is not well known. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) is one of the multifunctional protein kinases that has been implicated in the activation of myeloid cells and in regulating their ability to secrete cytokines [13]. GSK-3 was initially reported to be involved in metabolism and energy storage, yet it has since been shown to play divergent roles in various intracellular pathways [14]. There are two ubiquitously expressed isoforms of GSK3 encoded by distinct genes: GSK3α and GSK3β, which share sequence identity within their kinase domains, but GSK3α has an extended N-terminal region [15]. Their functions are partially but not fully redundant, and GSK3β has been much better characterized [14, 16, 17]. GSK3β has a number of substrates that allow it to coordinate many aspects of the immune response [18]. To directly address the role of GSK3β in NLRP3 activation we started by evaluating NLRP3 recruitment to TGN. Hela cells with stable overexpression of NLRP3-GFP were stimulated with nigericin. GSK3β depletion by siRNA knockdown significantly reduced the dynamic NLRP3 recruitment to mitochondria, and subsequently onto the Golgi (Fig. 3A, B), indicating GSK3β is required for NLRP3 trafficking. Recent studies have highlighted a model of reactive oxygen species (ROS)-sensitive NLRP3 ligand as one of the crucial elements for inflammasome activation [19]. Reduction of ROS with the antioxidants N-acetyl cysteine (NAC) significantly abolished NLRP3 recruitment to TGN, indicating ROS was required for NLRP3 puncta aggregation on TGN for inflammasome activation (Fig. S4A–D). In relation to this GSK3β inactivation had minor effects on ROS production indicating that GSK3β is downstream of ROS, and the requirement of GSK3β for subcellular NLRP3 trafficking was not simply due to its role on regulating ROS generation (Fig. S4). Further, the absence of GSK3β resulted in the disruption of NLRP3 aggregation and puncta formation on the TGN (Fig. S5). Of note, NLRP3 puncta aggregation on the TGN occurred independent of ASC, which is consistent with it being formed before the ASC speck (Fig. S6). The requirement of GSK3β for NLRP3 puncta aggregation on the TGN promoted us to examine the functional consequence in lack of GSK3β kinase activity in inflammasome activation. Similarly, GSK3β inactivation by a pharmacological GSK3β inhibitor resulted in the loss of NLRP3 puncta aggregation on the TGN (Fig. 4A, B). Pharmacological GSK3β inactivation potently reduced mature caspase-1, IL-1β production and ASC speck formation (Fig. 4C–G) without affecting the protein levels of NLRP3, pro-caspase-1 and pro-IL-1β in response to either ATP (Fig. 4C) or nigericin (Fig. 4D) stimulus in BMDMs. Moreover, GSK3α inhibition had minimal efficacy on reducing IL-1β production, as compared to GSK3β inhibition (Fig. S7A–E). By contrast, AIM2 inflammasome activation was unaffected by GSK3β (Fig. S7F). Furthermore, the effect was quite specific to GSK3β, as MAP, MEK and PI3 kinase inhibition did not reduce inflammasome activation assessed by ASC speck formation (Fig. S7G, H). Thus, these results indicated a potent and specific effect of GSK3β on the regulation of NLRP3 inflammasome assembly and activation. To validate the robustness of the role of GSK3β in NLRP3 inflammasome activation the ASC-reconstituted RAW264.7 mouse macrophages were used. GSK3β inactivation showed significantly less IL-1β release in response to NLRP3 stimulus (Fig. 4H), and the result was further confirmed in the J774 mouse macrophage line (Fig. 4I). Collectively, these data indicate that GSK3β is essential for subcellular NLRP3 trafficking to mitochondria with subsequent recruitment to the TGN, leading to inflammasome activation. These data revealed that the GSK3β mediated a stepwise model of cytosolic NLRP3 localizing initially to mitochondria, transient apposition of mitochondria and TGN, with the transfer of NLRP3 to the TGN.

Fig. 3. GSK3β deletion blocks NLRP3 trafficking to mitochondria following Golgi upon stimulus.

Hela cells expressing NLRP3-GFP were subjected to transfection with GSK3β specific siRNA (GSK3B KD) and scramble control siRNA (SCR). Cells were stimulated with nigericin (10 µM) for 120 min. A Representative time-lapse snapshots of NLRP3-Golgi and NLRP3-mitochondria contact. Scale bar = 10 µm. (B) Quantification of NLRP3-Mitochondria and NLRP3-Golgi interaction over the time-course in both SCR and GSK3B KD cells. Data represent the mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments.

Fig. 4. GSK3β is required for NLRP3 trafficking and inflammasome activation.

A Hela cells expressing NLRP3-GFP were treated with GSK3β inhibitor (SB216763) or an antioxidant (N-acetylcysteine (NAC)) following nigericin stimulation over 120 min. Representative images of NLRP3 aggregation on Trans-Golgi determined by fluorescence merge and colocalization analysis. B The levels of NLRP3- TGN38 colocalized pixel intensities were quantified from 10 different fields in each group. ****P < 0.0001. C–G LPS-primed mouse BMDMs were treated with SB216763 at different dosages following ATP (5 mM) for 30 min (C, E–G), or nigericin (10 µM) for 40 min (D). C, D Immunoblot analysis of active caspase-1 and IL-1β release, NLRP3 protein content and GSK3β phosphorylation were measured by western blot. E IL-1β release in culture supernatants by ELISA. F Immunofluorescence imaging of ASC specks (green spots indicated with white arrowheads) was performed using the antibody against ASC. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). G The levels of ASC specks were quantified by Image J. n = 12 fields. *P < 0.01. H IL-1β release by ELISA in culture supernatants from LPS-primed Raw264.7 macrophages stably expressing ASC with treatment as described in C. I IL-1β release by ELISA in culture supernatants from LPS-primed J774 macrophages which were pretreated with SB216763 following ATP as described in C. Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Association of phosphorylated GSK3β at position Tyr216 with the pyrin domain of NLRP3 upon stimuli

Inflammasome activation is known to primarily trigger pyroptosis with additional involvement of cell death including apoptosis and necroptosis depending on the cell type and the stimulus. In mouse macrophages LPS/ATP stimulus did not induce apoptosis but did induce cell death via pyroptosis, and this is blocked by GSK3β inhibition (Fig. S8A, B). The result is consistent with the known ability of inflammasome activation to induce pyroptosis, and our new findings of a key role for GSK3β in inflammasome activation. Furthermore, we investigated the role GSK3β- NFκB cross-talk for inflammasome activation (signal 2) post LPS priming (signal 1). This was performed by stimulation of mouse macrophages with ATP (signal 2 stimulus) in the presence or absence of GSK3β or NFκB inhibition. LPS priming induced NFκB p65 phosphorylation, however, no further changes occur after ATP stimulation in the presence or absence of GSK3β inhibition. Also, inhibition of NFκB activity post LPS priming shows no significant effect on cleaved IL1β protein levels (Fig. S8C, D). These findings suggest that targeting NFκB- GSK3β cross-talk at signal 2 does not affect NLRP3 inflammasome activation. We also performed IL-18 ELISA on LPS/ATP stimulated macrophages in the presence or absence of GSK3β inhibition (Fig. S8E) and observed that NLRP3 inflammasome activation also upregulates IL-18 secretion which was inhibited by GSK3β inhibitor. Finally, we confirmed that the GSK3β pathway is relevant to additional types of NLRP3 inflammasome stimulators by demonstrating the ability of the GSK3β inhibitor to block Alum triggered signal 2 (Fig. S8F, G).

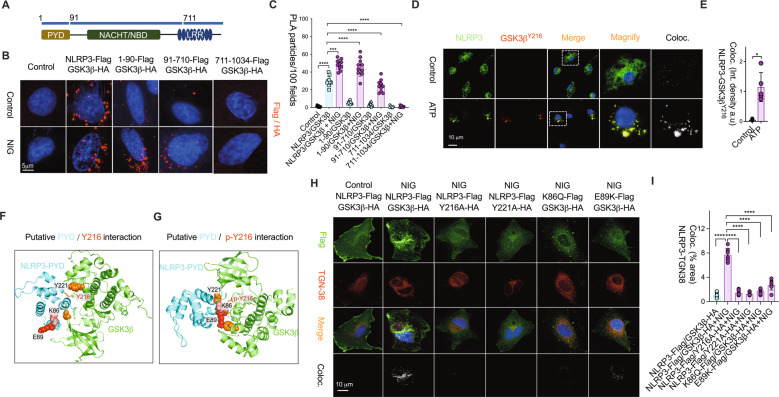

Structurally the NLRP3 protein contains an N-terminal pyrin domain (PYD), a nucleotide-binding (NACHT/NBD) domain, and a C-terminal leucine-rich repeat (LRR) domain [20]. Upon stimuli, NLRP3 is able to recruit the adaptor protein ASC through homotypic PYD-PYD interactions, ASC recruits caspase-1 leading to its activation and cleavage of pro-IL1β to produce active IL-1β [3]. To investigate the structural parameters of GSK3β/NLRP3 interaction and the molecular requirement for NLRP3 recruitment onto the TGN, we approached a domain-based association assay of protein function using several N-terminally truncated active forms of NLRP3 (Fig. 5A). The in-situ protein-protein interaction analysis using Duolink proximity ligation (PLA) showed that GSK3β directly associated with the PYD domain of NLRP3 protein (Fig. 5B, C), and this was confirmed similarly using the different approach of confocal image colocalization assay (Fig. S9). Phosphorylation of specific GSK3β residues can increase its ability to bind its substrates, which can in turn auto-phosphorylate [21]. To firstly determine the phosphorylation sites of GSK3β triggered by NLRP3 stimuli, we performed selective phosphopeptide enrichment of protein lysates from ATP-simulated macrophages prior to their measurement by mass spectrometry. We observed that GSK3β phosphorylation at position Tyr216 occurred in response to NLRP3 stimulation by LC-MS/MS analysis. Phosphorylation of GSK3β-Tyr216 and its colocalization with NLRP3 after ATP treatment was confirmed by immunostaining (Fig. 5D, E). To determine the structural association of GSK3β and NLRP3, we further performed bioinformatics and computational survey for modeling protein interactions. The 3D structure of GSK3β and NLRP3 were retrieved from public RCSB PDB resources (https://www.rcsb.org/). Molecular docking analysis was conducted (using HADDOCK protein-protein docking program, https://haddock.science.uu.nl/) in combination with a simple but robust scoring for ranking to infer a plausible location of GSK3β/NLRP3-binding sites (Fig. S10). The structural analysis docked the concrete confinement scores as per high-strength of close inter-residual distances and strong binding energy between Y221 position in GSK3β and respective conserved key residues of K86 and E89 positions in PYD domain of NLRP3 protein in native condition (Fig. 5F, G, Fig. S11) indicating a potential association occurs between phosphorylated GSK3β-Tyr216 and NLRP3 protein. Confirmatory confocal microscopy consistently showed that NLPR3PYD/TGN colocalization as well as NLRP3 puncta by NLRP3 stimuli are abolished in cells with forced expression of the serial mutants of GSK3β-Y216A, GSK3β-Y221A, NLRP3PYD-K86Q and NLRP3PYD-E89K (Fig. 5H, I). Correspondingly, cells expressing either the GSK3β-Y216A/Y221A or NLRP3PYD-K86Q/E89K double mutant constructs significantly abrogated NLRP3/GSK3β association in response to nigericin stimulus (Fig. S12). These results supported that the phosphorylated GSK3β binding to NLRP3 was a key early step in NLRP3 trafficking and inflammasome assembly. NLRP family proteins are typically comprised of a PYD domain, which is best known for innate immune responses and particularly in the assembly of inflammasomes. To further investigate whether NLRP3 interaction with GSK3β at the PYD domain could apply to other NLRPs, we retrieved the available 3D structures of NLRPs and approached the similar molecular docking analysis using HADDOCK. Among all the observed NLRPs, NLRP6PYD with the highest sequence similarity to NLRP3PYD had the strongest binding strength with GSK3β, while NLRP7PYD with weak sequence similarity to NLRP3PYD had the weakest binding strength (Table S1). These in silico illustrations highlighted the significance of unique amino acid sequence in the PYD domain of NLRP3 encoded by GSK3β activation.

Fig. 5. pGSK3β-Tyr216 interacts with NLRP3 via its pyrin domain.

A Diagram of NLRP3 fragment constructs containing PYD (1-90), NBD (91-710), and LRR (711-1034) domain. B Representative images of Duolink proximity ligation (PLA) assay of Hela cells in situ co-transfected with GSK3β-HA tag and NLRP3-Flag tag fragment constructs with/without nigericin stimulation. C The levels of PLA fluorescence pixels quantified by Image J. n = 10 fields. Scale bar 10 µm. ****P < 0.001, ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05. Representative images (D) and quantifications (E) of NLRP3 colocalization with phosphorylated GSK3β at Tyr216 site in LPS-primed BMDMs as described in Fig. 2C. n = 6 fields. Scale bar 10 µm. Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05. F, G Putative interaction between NLRP3PYD domain (PDB ID: 2NAQ) and GSK3β (PDB ID: 4DIT) with phosphorylation at Y216 site was predicated using HADDOCK protein-protein docking program by Haddock prediction interface. F, G Pymol generated images of docking results show a strong interaction between (F) K86 of NLRP3PYD and Y221 of GSK3β while the mutation of GSK3β-Y221A results in a weak interaction with K86 as shown in (G). H, I NLRP3-TGN38 colocalization was disrupted by the co-expression of NLRP3PYD/ GSK3β-Y216A, NLRP3PYD/ GSK3β-Y221A, NLRP3PYD-K86Q/ GSK3β, or NLRP3PYD-E89K mutant constructs, (H) Representative images, (I) Quantifications. n = 10 fields. Scale bar 10 µm. Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. ****P < 0.001, ***P < 0.01.

GSK-3β phosphorylation of PI4K2A at Ser5/9 residues in the TGN is an essential step for NLRP3 recruitment

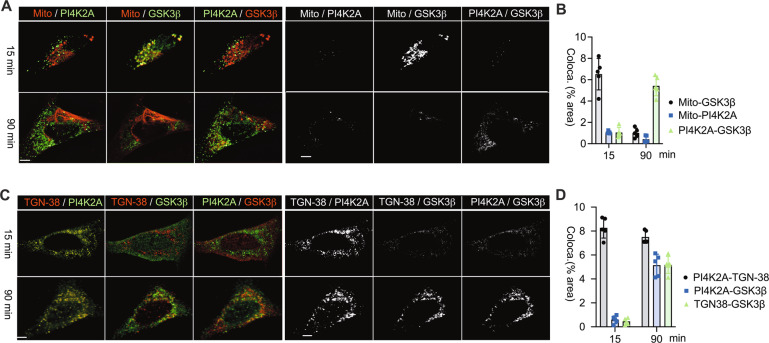

GSK-3β functions as a serine/threonine kinase, its substrates range from regulators of cellular metabolism to molecules that control cell signaling 14. To identify the GSK-3β phosphorylation downstream target which contributes to inflammasome activation, we performed the phosphopeptide enrichment of protein lysates from ATP-stimulated macrophages with/without the pharmacological inactivation of GSK3β prior to their measurement by mass spectrometry. Interestingly, the LC-MS/MS analysis identified phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase 2A (PI4k2A) containing peptide sequence with both serine 5 and 9 residues (Ser5/9) as downstream of GSK3β (Fig. S13). PI4k2A is a lipid kinase that phosphorylates the 4 positions of phosphatidylinositol (PI) lipids. PI4k2A regulates intracellular vesicle trafficking among the Golgi, endosomes and lysosomes [22, 23]. PI4k2A is highly expressed in mammalian cells, where it accounts for the majority of 4′ PI phosphorylation activity and localizes to the TGN /endosomal membranes [22, 24]. We further measured the protein localization of both GSK3β and PI4K2A in parallel by confocal imaging in response to NLRP3 stimuli during a time-course, PI4K2A enriched and localized at the TGN during the entire period (Fig. 6A, B). In contrast, GSK3β was only colocalized with mitochondria at early phase, and translocated to TGN at late phase (Fig. 6C, D) indicating GSK3β triggers PI4K2A phosphorylation at TGN. Thus, the results confirmed that the Ser5/9 residues of PI4K2A functions as unique downstream substrate of GSK3β pathway activation [23]. The similar approach of HADDOCK based molecular protein docking survey infers the binding with plausible sites between PI4k2A and NLRP3 interaction (Fig. S14). The association between PI4k2A and NLRP3 protein in Hela cells was determined by the in-situ protein-protein interaction assay using PLA (Fig. 7A, B), and this association in endogenous protein level was further advanced by colocalization analysis in primary BMDMs (Fig. 7C), and in response to Alum as signal 2 (Fig. S15). Forced expression of PI4k2A constructs with the double mutants of Ser5/9 residues identified from LC-MS/MS (Fig. 7D) entirely abrogated NLRP3 puncta formation as well as its colocalization on the TGN in Hela cells (Fig. 7E, F). Furthermore, the association among all three proteins of PI4k2A, GSK3β and NLRP3 was validated by protein immuno-precipitation assay (Fig. 7G). This confirms that phosphorylation of PI4k2A at Ser5/9 residues by GSK3β is a key mechanism for PI4k2A mediated regulation of NLRP3 trafficking, aggregation and inflammasome assembly. To determine the function of PI4k2A for NLRP3 inflammasome activation under physiological conditions interfering RNAs (siRNA) targeting GSK3β or PI4k2A were used to individually suppress endogenous GSK3β and PI4k2A expression (Fig. 7H). Depletion of GSK3β or PI4k2A greatly decreased mature caspase-1 and IL-1β release (Fig. 7H, I) from nigericin-treated mouse BMDMs without changing the protein expression level of NLRP3, pro-caspase-1 and pro-IL-1β (Fig. 7H). These data show that GSK3β controls subcellular NLRP3 trafficking and inflammasome activation by its direct phosphorylation of PI4k2A in TGN. Interestingly, a population of GSK3β located at the Golgi was previously shown to promote cargo transport from the Golgi to pre-lysosomal compartments [53]. Therefore, PI4k2A represented as a major target of GSK3β for maintaining a transport route from Golgi /endosomes to lysosomes for degradation of cargo proteins.

Fig. 6. GSK3β directly targets on PI4K2A at TGN upon stimulus.

Hela cells were stimulated with nigericin (10 μM) for 15 and 90 min. A, B Representative images and the quantification of mitochondria/PI4K2A, mitochondria/GSK3β, PI4K2A/GSK3β colocalization. C, D Representative images and the quantification of TGN-38/PI4K2A, TGN-38/GSK3β, PI4K2A/ GSK3β colocalization. Scale bar = 10 μm. The 2 channel colocalization was quantified using Image J colocalization plugin. At least 5 cells were imaged per group and quantified. Data represent the mean +/- SD of three independent experiments.

Fig. 7. PI4K2A phosphorylation by GSK3β directs NLRP3 recruitment to the TGN.

A Representative images of Duolink-PLA of Hela cells co-transfected with PI4K2A-His and NLRP3-Flag constructs. B The levels of PLA fluorescence pixels were quantified by Image J. n = 10 fields. Scale bar 10 µM. ****P < 0.001, ***P < 0.01, **P < 0.05. C Representative images of NLRP3 colocalization with PI4k2A in LPS/Nigericin treated BMDMs. D Mass spectrometry identification of highly conserved PI4k2A peptides in phosphorylated proteins enriched from the cell lysate of LPS/ATP treated BMDMs. E Representative images and (F) quantification of NLRP3 colocalization with Trans-Golgi in nigericin stimulated Hela cells expressing PI4K2A-S5/9A mutant. n = 8 fields. Scale bar 10 µM. ***P < 0.01. G Endogenous GSK3β association with PI4k2A and NLRP3 in LPS/ATP treated BMDMs. H Immunoblot analysis of active caspase-1 and IL-1β release, the protein contents of NLRP3, GSK3β and PI4k2A in whole cell lysate (Lysate) and cell supernatants (Super) from LPS/ATP treated BMDMs with Gsk3β and Pi4k2α knockdown (KD). I IL-1β release by ELISA in cell supernatants from LPS/ATP treated BMDMs with Gsk3β and Pi4k2α knockdown (KD). Data represent mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Inhibition of inflammasome activation by pharmacological GSK3β inactivation in mice

The in vivo relevance of this pathway was confirmed in mouse models of inflammation. GSK3β inactivation significantly reduced the recruitment of immune cells and generated significantly less IL-1β in MSU-induced peritonitis (Fig. S16), significantly less serum IL-1β in diet-driven inflammation (Fig. S17), and protection from ethanol-induced liver tissue injury (Fig. S18). The three models of alum-induced peritonitis, diet-induced inflammation and ethanol-induced liver inflammation are different in many aspects but share the features of activation of the sterile inflammatory response in myeloid cells as key to the inflammatory process. These studies convincingly show that GSK3β is required for NLRP3 inflammasome activation in vivo. Thus, these findings reveal a coordinated molecular signaling and multi-step subcellular spatiotemporal machinery which results in organized movement of cytosolic NLRP3 to mitochondria, brief apposition of mitochondria with TGN, and transfer of NLRP3 to the TGN. Phosphorylation of GSK3β resulting in its binding to NLRP3 is a key initiating step, and phosphorylation of PI4K2A is required for the localization of NLRP3 to TGN leading to inflammasome assembly and activation (Fig. S19). Collectively, this is the first study to integrate the biochemical and spatiotemporal organization of NLRP3 activation. We have delineated the mechanistic modelling of molecular signals mediated by GSK3β targeted PI4K2A activity in the requirement of NLRP3 protein scaffolding, trafficking and recruitment between organelles resulting in inflammasome activation. Each enzymatic and spatiotemporal step in this process provides novel insights and a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Cancer Institute. ASC−/−mice have been described previously [25]. All procedures were performed in accordance with the regulations adopted by the National Institutes of Health and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Yale University. Eight- to 12-week-old male mice were randomly assigned in most experiments.

The high-fat diet (HFD) and diabetic-HFD animal experiments were performed in the Experimental Animal Platform of Medical Research Center in Army Medical University in China, and all animal research was approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee/Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Army Medical University. The establishment of HFD and diabetic-HFD mouse models have been described previously [26].

The number of mice in each experimental group was chosen based on previous experience with these experimental models. Experiments were blinded to the person performing marker analysis.

Antibodies and reagents

Antibodies against NLRP3 (AG-20B-0014) and ASC (AG-25B-0006) were from AdipoGen LIFE SCIENCES. Antibodies against caspase-1 (SC-515), TGN38 (SC-166594) and TOM20 (SC-11415) were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Antibodies against GM130 (D6B1), PARP (9542) and caspase-3 (pro- 9662 and p30- 9661) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibody against IL-1β (AB-401-NA) was from R&D Systems. Nigericin (N7143) and ATP (A7699) were from Sigma-Aldrich. Antibody against Gasdermin D (IN110) was from Adipogen.

Mammalian cell culture

The HeLa cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Life technologies), PenStrep (penicillin - 100 U/ml & streptomycin -100 µg/ml, Gibco, Life technologies). HeLa cells were originally obtained from ATCC (https://www.atcc.org/), and were monitored regularly for contamination from other cell types. The cells were maintained free of bacterial, fungal or mycoplasma contamination.

Mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) were derived from bone marrow cells and differentiated for 7 days in complete RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ ml penicillin, 100 μg/ ml streptomycin, 50 μM 2-mercaptoethanol (all from Invitrogen), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 20 ng /ml M-CSF (PeproTech). All the cells were cultured at 37 °C with 5% (v/v) CO2 atmosphere.

Plasmids, viruses, and stable cell line

For the confocal microscopy experiments, the HeLa cells were transfected with pEGFP-C2-NLRP3 (λ492 – excitation; λ515 – emission). The cells were stably selected with 400 µg/ml concentration of G418 and were used for further experiments. TOM20 with mPlum tag (mPLUM-TOMM20-N-10mit) was used for mitochondria, since mPlum tag uses far-red laser for excitation (λ590 - exictation; λ649 - emission) and can be used in live cells for long exposure without significant mitochondrial damage. pEGFP-C2-NLRP3 was a gift from Christian Stehlik (Addgene plasmid # 73955) and mPlum-TOMM20-N-10 was a gift from Michael Davidson (Addgene plasmid # 56002). Prior to transfection, the regular medium was replaced by OPTI-MEM (Life technologies) for overnight, the plasmids were complexed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Life technologies) for HeLa cell transfection. The Golgi apparatus was marked with Cell Light® Golgi-RFP (Life technologies), which is a Bacman 2.0 virus-containing N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase with TagRFP (λ555 - excitation; λ584 - emission). N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferase is an enzyme located mostly in trans-Golgi vesicles and to some extent in medial Golgi, hence more suitable for experiments focusing on protein localization in trans-Golgi.

For immunological experiments the HeLa cells were transfected with either one or more of the following: NLRP3- Flag (pcDNA3.1-N-Flag-NLRP3), GSK3β-HA (pcDNA3.1-HA-GSK3β), PI4K2A His-tag (pcDNA3.1-His-PI4K2A) and PI4K2AS5/S9A mutant with His-tag (OHu69394DM_1 construct in pcDNA 3.1-His-PI4K2A), NLRP3-Flag-E86Q, NLRP3-Flag-K89E, GSK3β-HA-Y216A and GSK3β-HA-Y221A were custom designed and synthesized from GenScript Biotech (Piscataway, NJ). pcDNA3-N-Flag-NLRP3, pcDNA3-N-Flag-NLRP31–90, pcDNA3-N-Flag-NLRP391–710 and pcDNA3-N-Flag-NLRP3711–1034 were a gift from Bruce Beutler (Addgene plasmid #75127; #75137; #75140; #75141). pcDNA3.1-HA-GSK3β was a gift from Jim Woodgett (Addgene plasmid #14753).

Human GSK3B siRNA (Cat # sc-35527, Santa Cruz biotechnology) and scramble controls were used in HeLa cells. Mouse GSk3b siRNA (Silencer Select pre-designed siNRA, siRNA ID #: s80826, Ambion by Life Technologies) and scramble controls were used in BMDMs. Mouse Pi4k2a siRNA (Silencer Select pre-designed siNRA, siRNA ID #: s96535, Ambion by Life Technologies) and scramble controls were used in BMDMs. The CRISPR-lentivirus containing GFP (Mission TRC3 ORF GFP lentivirus with 107 TU/ml) was used to knockout PI4K2A in HeLa cells. Cells transduced with control transduction particles (Mission TRC3 ORF GFP Lentivirus High Titer Control with 5 × 108 TU/ml) were used as the negative control.

Isolation of fraction enriched in TGN

The cell TGN fraction was isolated using Minute™ Golgi Apparatus Enrichment Kit (GO-037, Invent Biotechnologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Inflammasome stimulation

For stimulation of reconstituted cell lines, the culture medium was replaced by OPTI-MEM medium containing inflammasome stimulus, including nigericin (10 μM). The cells were then incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere with 5% (v/v) CO2 for 90 min unless otherwise specified. Poly(dA: dT) (InvivoGen) was transfected into cells with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at 1.5 μg/ml for 3 h. BMDMs were primed with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 3 h before the addition of NLRP3 stimulus with nigericin (10 μM), ATP (5 mM) for 30 min, Alum for 5 h unless otherwise specified. Cells were collected in lysis buffer A (20 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM DTT, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to collect lysate for immunoblotting. Cell culture supernatant was also collected for detection of secreted caspase-1 p10 and IL-1β p17.

Live cell time lapse imaging and analysis

HeLa cells stably selected for NLRP3-GFP expression were transfected with TOM20-mPLUM. Following 24 h, the cells were transduced with Cell Light® Golgi-RFP and incubated overnight. At 48 h, the cells were plated on to 60µ-Dish (ibidi µ-Dish, 35 mm, high) with glass base, suitable for live cell imaging. The cells were imaged using Leica SP8 confocal microscope equipped with a live cell incubation chamber set up (37 °C heated chamber & objective; 5% CO2 supply). The images were acquired using the 40 × oil immersion objective. The green and cyan channels were acquired with PMT detector, while the mPlum channel was acquired using HyD detector with 0.3 gating. The dimension of the video file was set as 1024 × 1024 pixels to maximize clarity without losing significant frames. The microscope stage and the culture dish were allowed to equilibrate at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 h and then cells were screened for optimal expression of TOM20-mplum, NLRP3-GFP and Golgi-RFP. Once the cell was selected and focused, 10 µM nigericin was added to the medium and immediately the live cell time lapse sequence was initiated as Z stacks of 38 × 0.35 µm Z-slices at an interval of 5 min for a period of 2 h. The time lapse video file was acquired with LASX software (Leica, Germany) and was processed using IMARIS image analysis software (IMARIS 9.2.1, Bitplane). The IMARIS animation tab was used to record the 3D time lapse video of the cells. In the colocalization plugin of the Vantage function, each channel was overlaid with other channel and was analyzed at each time point for colocalization signal. The colocalization points were shown as white pixels superimposed upon 2-channel overlay. For higher resolution and clarity, the Z stack files were analyzed using 3D surface overlay. The dimensions of TOM20 and Golgi were measured using the slice function and the seed points were set accordingly while constructing 3D surfaces.

Live cell time tracking for Golgi-mitochondria-NLRP3 interactions

The Golgi and TOM20 channels from 3D time lapse video file were processed for 3D surface overlay and the motion of NLRP3 with respect to mitochondrial surface, motion of NLRP3 with respect to trans-Golgi (TGN) and motion of mitochondria with respect to TGN with time was tracked using the auto-aggressive motion tracking setting in the IMARIS software. The motion path was displayed as color coded lines, where the color spectrum represents the experiment time scale (violet – start point and deep red – end point). This motion tracking function aids to identify the interactions or associations and disassociations of various structures within a given experimental time frame.

Immunofluorescence staining

For immunostaining, cells were grown in 8 well slide chambers with removable wells (NUNCTM Lab-TekTM II Chamber SlideTM system, Thermo fisher scientific). The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 in PBS, before incubation with primary antibodies followed by Alexa Fluor-tagged secondary antibodies. In case of non-fluorescent tagged (FLAG/HA/HIS) protein, the cells were fixed with methanol instead. Nuclei were stained with DAPI in mounting medium (Prolong-Diamond antifade medium with DAPI). To ensure the quality of multi-fluorescent antibody stains in single experiments, controls lacking one of the stains and controls without primary antibody staining were used.

Fluorescence images of fixed cells were taken with a WLL (while light laser) Leica SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope. The images were mostly acquired under 100 × oil immersion objective with 1024 × 1024 pixel dimensions. PMT detectors were used for abundant proteins at visible range wavelengths while highly sensitive HyD detector with gating was used for low abundant proteins. Gating function in HyD detector allows for filtering out excitation wavelength overlay between two close-range fluorophores. The images from immunostaining were exported as leica image files (LIF) and were processed using IMARIS software (bitplane). The images were uniformly amended with minimal Gaussian blur to reduce graininess. The images of individual channels and/or overlay were saved as high-resolution TIF files. Further, the exported images were analyzed using Image J software package (NIH) for further analysis [27, 28]. The colocalization of two fluorescent channels was analyzed using Coloc2 function in Image J. The colocalization pixels were quantified, statistically analyzed, and were represented as the percentage of colocalization area.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM)

The cells were cultured on cover slips (Celltreat®) at the density of 1.5 × 106 cells/ml for overnight. The cells were primed with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 4 h followed by ATP (5 mM) stimulation. The cells were fixed by addition of fixation buffer (mixture of 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% formaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4) at 0, 5 and 10 min. The fixative was added as a 2 × concentrate directly to culture medium at 1:1 ratio and allowed to fix for 1 h at RT. The cells on coverslips were further washed 3 times with the 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and provided to the Yale electron microscopy core for further processing and imaging. After further processing and resin embedding, the specimens are cut into ultrathin sections (50–70 nm) and processed for TEM imaging. The specimens were specifically focused for areas enriched with mitochondria and Golgi structures. The images were acquired using FEI Tecnai Biotwin transmission electron microscope (80 kv). The specimens were specifically focused for areas enriched with mitochondria and Golgi structures. The resulting images were false colored to differentiate the mitochondrial (red) and Golgi (green) structures.

Duolink Proximity Ligation (PLA) assay

The Duolink proximity ligation (PLA) assay was performed, as previously described by our laboratory [29]. Briefly, the cells cultured in 8 well slide chamber were fixed and blocked in 5% (vol/vol) donkey serum (Duolink blocking solution) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight with the following pairs of primary antibodies: rabbit-HA (C29F4) or rabbit-His (D3I1O) and mouse-Flag (9A3) from Cell Signaling Technology at 4 °C. The cells were then incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with the following Duolink PLA probes: anti-Rabbit MINUS (Sigma-Aldrich, DUO92005) and anti-mouse PLUS (Sigma-Aldrich, DUO92003). Duolink in situ detection reagent kit (Sigma-Aldrich, DUO92008) was used for ligation and amplification at 37 °C according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The slides were then mounted using Duolink DAPI-mounting medium, and all images were acquired using Leica WLL SP8 confocal laser scanning microscope with LASX image processing interface at 40 × magnification. Fluorescence of PLA indicating interacting proteins was analyzed as intensity above threshold using NIH Image J software and represented as fold change from respective controls.

Protein-protein interaction in-silico analysis

To investigate the molecular interactions between the inflammasome proteins NLRP3, GSK3β and PI4K2A, the structures of these proteins were analyzed by protein-protein docking using HADDOCK prediction interface (HADDOCK 2.2 webserver@BonvinLab). This portal uses bioinformatic data, structural information, and experimental biophysical/biochemical data to expedite the modelling process. The protein structures for human NLRP3- PYD domain (2NAQ), human GSK3β (1H8F) and human PI4K2A (4PLA) were obtained from The Protein Data Bank (RCSB-PDB) as.pdb file format. For phosphorylated form of GSK3β, the pdb file was edited with PDB file editor (http://www.bioinformatics.org/pdbeditor/wiki/), where phospho group was added to Y216 residue. The files were prepared for docking using PYMOLv2.4 software (Schrondinger, Inc). The previously known active sites for the proteins were defined, the rotamer states of all active site amino acids were set to on and the structures were saved for analysis. When the structures were uploaded to HADDOCK prediction interface the passive residues were set for automatic selection. The top-ranking clusters from HADDOCK output files with lowest RMSD value and highest HADDOCK score were analyzed using PYMOL to identify the interacting residues, where only the residues with inter-amino acid distance >3.5 Å were selected for mutation analysis. These amino acids in interaction interface were mutated using the mutation wizard in PYMOL and the mutant forms of proteins were again subjected to HADDOCK docking to compare the interaction changes upon mutation.

Western blotting

The protein samples from BMDMs and HeLa cells used in the experiment were subjected to western blotting as a part of the study. The cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and then protein was extracted with RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce protease inhibitor tablets, Thermo fisher scientific) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (PhosSTOP, Sigma-Aldrich). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred on to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) via semi-dry transfer using a Pierce power blotter (Thermo fisher scientific). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in 1 × TBST for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation in respective primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. The primary antibodies were mostly used at a dilution of 1:1000 except anti-Gasdermin D rat monoclonal IgG, which was used at 1:500 dilution. To assure equal loading of proteins in all the wells, β-actin was used as the loading control. Whereas for supernatants, the blotted membranes were stained with PonceauS (Sigma-Aldrich) and shown for equal protein load in all samples. The blots were then incubated in corresponding secondary antibodies: goat-anti mouse HRP (1:20,000), goat anti-rabbit HRP (1:10,000) and goat anti-rat HRP (1:10,000) for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were then subjected to enhanced chemiluminescence reaction (SupersignalTM, west pico plus, Thermo fisher scientific) and captured using Hyblot X-ray film in dark. Original blots are available in supplementary materials.

MSU-induced mouse peritonitis

C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally with 2 mg MSU dissolved in 0.5 ml sterile PBS. Mice were euthanized 6 h later and peritoneal cavities were flushed with 5 ml cold PBS. Peritoneal lavage fluids were collected, and cytokines were measured by ELISA.

Statistical analysis

The sample size chosen for our animal experiments in this study was estimated based on previous experiments [29, 30]. All animal results were included, and no method of randomization was applied. For all the bar- graphs, data were expressed as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 7 (GraphPad). Data were compared either by a standard two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or paired Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni’s post-hoc test. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Yale Liver Center Morphology Core/Molecular Core Facilities for the support of confocal microcopy, image processing and biological assay, Yale Proteomics Core Facility for the support of LC-MS/MS assay, Center for cellular and molecular imaging (CCMI) EM core facility at Yale medical school for EM processing. This study was supported by NIH UO1 grant 5U01AA026962-04 (to WZM and XO), by VA Merit award BX003259-05(to W.Z.M.), by Yale Liver Center Award NIH P30DK-034989 Morphology Core and Cellular /Molecular Core, and in part by Yale Liver Center Pilot Project Award (to XO) and NCI grant 5R01CA224023-03 (to RAF). The Yale Liver Center Core Facilities were funded by NIH by grant DK P30-034989.

Author contributions

SA, RAF, WZM, and XO designed the research plan and interpreted the results. SA, YQ, ZL, SH, QL, and XO performed and analyzed the experiments. SA and. SB performed reversal experiments. SA, WZM, and XO wrote and WZM and XO edited the manuscript. XO supervised the project and gave final approval.

Data availability

All data are presented in the main text or supplementary materials. The expression plasmids reported in this manuscript are available at Addgene or upon request. The rest of the data supporting the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Our studies did not include human participants, human data, or human tissue. For the animal studies, experiments were performed according to both the Animal Care and Use Committee of Yale University and the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee/Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Army Medical University.

Footnotes

Edited by M. Piacentini

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Wajahat Z. Mehal, Email: wajahat.mehal@yale.edu

Xinshou Ouyang, Email: xinshou.ouyang@yale.edu.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41418-022-00997-y.

References

- 1.Place DE, Kanneganti TD. Recent advances in inflammasome biology. Curr Opin Immunol. 2018;50:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2017.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo H, Callaway JB, Ting JP. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of action, role in disease, and therapeutics. Nat Med. 2015;21:677–87. doi: 10.1038/nm.3893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu A, Magupalli VG, Ruan J, Yin Q, Atianand MK, Vos MR, et al. Unified polymerization mechanism for the assembly of ASC-dependent inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;156:1193–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cai X, Chen J, Xu H, Liu S, Jiang QX, Halfmann R, et al. Prion-like polymerization underlies signal transduction in antiviral immune defense and inflammasome activation. Cell. 2014;156:1207–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Chen ZJ. PtdIns4P on dispersed trans-Golgi network mediates NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2018;564:71–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0761-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Subramanian N, Natarajan K, Clatworthy MR, Wang Z, Germain RN. The adaptor MAVS promotes NLRP3 mitochondrial localization and inflammasome activation. Cell. 2013;153:348–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anand PK, Malireddi RK, Kanneganti TD. Role of the nlrp3 inflammasome in microbial infection. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:12. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou R, Yazdi AS, Menu P, Tschopp J. A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature. 2011;469:221–5. doi: 10.1038/nature09663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misawa T, Takahama M, Kozaki T, Lee H, Zou J, Saitoh T, et al. Microtubule-driven spatial arrangement of mitochondria promotes activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:454–60. doi: 10.1038/ni.2550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang Z, Meszaros G, He WT, Xu Y, de Fatima Magliarelli H, Mailly L, et al. Protein kinase D at the Golgi controls NLRP3 inflammasome activation. J Exp Med. 2017;214:2671–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.20162040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyer SS, He Q, Janczy JR, Elliott EI, Zhong Z, Olivier AK, et al. Mitochondrial cardiolipin is required for Nlrp3 inflammasome activation. Immunity. 2013;39:311–23. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valm AM, Cohen S, Legant WR, Melunis J, Hershberg U, Wait E, et al. Applying systems-level spectral imaging and analysis to reveal the organelle interactome. Nature. 2017;546:162–7. doi: 10.1038/nature22369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beurel E, Michalek SM, Jope RS. Innate and adaptive immune responses regulated by glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3) Trends Immunol. 2010;31:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: Tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1175–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woodgett JR. Judging a protein by more than its name: GSK-3. Sci STKE. 2001;2001:re12. doi: 10.1126/stke.2001.100.re12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ali A, Hoeflich KP, Woodgett JR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3: Properties, functions, and regulation. Chem Rev. 2001;101:2527–40. doi: 10.1021/cr000110o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Forde JE, Dale TC. Glycogen synthase kinase 3: A key regulator of cellular fate. Cell Mol Life Sci: CMLS. 2007;64:1930–44. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glibo M, Serman A, Karin-Kujundzic V, Bekavac Vlatkovic I, Miskovic B, Vranic S, et al. The role of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) in cancer with emphasis on ovarian cancer development and progression: A comprehensive review. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2021;21:5–18. doi: 10.17305/bjbms.2020.5036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tschopp J, Schroder K. NLRP3 inflammasome activation: The convergence of multiple signalling pathways on ROS production? Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:210–5. doi: 10.1038/nri2725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broz P, Dixit VM. Inflammasomes: Mechanism of assembly, regulation and signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:407–20. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frame S, Cohen P, Biondi RM. A common phosphate binding site explains the unique substrate specificity of GSK3 and its inactivation by phosphorylation. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1321–7. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00253-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo J, Wenk MR, Pellegrini L, Onofri F, Benfenati F, De Camilli P. Phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type IIalpha is responsible for the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase activity associated with synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3995–4000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230488100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JW, Leshchyns’ka I, Farghaian H, Hughes WE, Sytnyk V, Neely GG, et al. PI4KIIalpha phosphorylation by GSK3 directs vesicular trafficking to lysosomes. Biochem J. 2014;464:145–56. doi: 10.1042/BJ20140497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balla A, Tuymetova G, Barshishat M, Geiszt M, Balla T. Characterization of type II phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase isoforms reveals association of the enzymes with endosomal vesicular compartments. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20041–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111807200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ouyang X, Ghani A, Malik A, Wilder T, Colegio OR, Flavell RA, et al. Adenosine is required for sustained inflammasome activation via the A(2)A receptor and the HIF-1alpha pathway. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2909. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leng W, Ouyang X, Lei X, Wu M, Chen L, Wu Q, et al. The SGLT-2 inhibitor dapagliflozin has a therapeutic effect on atherosclerosis in diabetic ApoE(-/-) mice. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:6305735. doi: 10.1155/2016/6305735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiemerslage L, Lee D. Quantification of mitochondrial morphology in neurites of dopaminergic neurons using multiple parameters. J Neurosci Methods. 2016;262:56–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2016.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bravo-Sagua R, Parra V, Ortiz-Sandoval C, Navarro-Marquez M, Rodriguez AE, Diaz-Valdivia N, et al. Caveolin-1 impairs PKA-DRP1-mediated remodelling of ER-mitochondria communication during the early phase of ER stress. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:1195–212. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0197-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao P, Han SN, Arumugam S, Yousaf MN, Qin Y, Jiang JX, et al. Digoxin improves steatohepatitis with differential involvement of liver cell subsets in mice through inhibition of PKM2 transactivation. American J Physiol Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 2019;317:G387–97. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00054.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouyang X, Han SN, Zhang JY, Dioletis E, Nemeth BT, Pacher P, et al. Digoxin suppresses Pyruvate Kinase M2-Promoted HIF-1alpha Transactivation in Steatohepatitis. Cell Metab. 2018;27:1156. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are presented in the main text or supplementary materials. The expression plasmids reported in this manuscript are available at Addgene or upon request. The rest of the data supporting the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.