Abstract

Background:

The current nomenclature of obstetrical disorders is based on symptoms and signs and has been an obstacle for the accurate prediction and prevention of adverse pregnancy outcomes. We propose that a new taxonomy of obstetrical disease, which combines both clinical presentation and disease mechanisms as inferred by placental pathologic findings, will aid in the discovery of biomarkers, add specificity to those already known, and further facilitate prediction and prevention in obstetrics. This study was designed to test whether classifying obstetrical syndromes according to the presence or absence of placental vascular lesions improves the performance of putative biomarkers for prediction of adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Objectives:

To establish the longitudinal profile of placental growth factor (PlGF), soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), and the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio throughout gestation, and to determine whether the association between abnormal biomarker profiles and obstetrical syndromes is strengthened by the additional information (eg the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion) derived from placental examination.

Study Design:

This retrospective case cohort study was based on a parent cohort of 4,006 pregnant women enrolled prospectively. The case cohort (N=1,499) included 1,000 randomly selected patients from the parent cohort and all additional patients with obstetrical syndromes from the parent cohort. Patients were classified into six groups: 1) term delivery without pregnancy complications (n=540; control); possibly co-occurring obstetrical syndromes, including 2) preterm labor and delivery (n=203); 3) preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes (n=112; PPROM); 4) preeclampsia (n=230); 5) small-for-gestational-age (SGA) neonate (n=334); and 6) other pregnancy complications (n=182). Maternal plasma concentrations of PlGF and sFlt-1 were determined by using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays in 7,560 longitudinal samples. Placental pathologists, masked to clinical outcomes, diagnosed the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. Comparisons between mean biomarker concentrations in the control group and in those who developed any of the obstetrical syndromes were performed by utilizing longitudinal generalized additive models. After transforming the data into multiples of the mean (MoM) for gestational age and relevant maternal characteristics, we determined the adjusted odds ratios (aOR) conferred by an abnormal MoM PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio (<20th centile) at 28 to 32 weeks of gestation. For each obstetrical syndrome, comparisons were made between controls and cases regardless of placental pathology findings (aggregated), and then the cases were subdivided according to the presence or absence of placental lesions (disaggregated).

Results:

1) The frequency of placental lesions consistent with maternal vascular malperfusion varied by obstetrical syndrome: preeclampsia, 44%; SGA neonate, 40%; preterm labor, 30%; PPROM, 27%; and only 15% in term delivery controls; 2) the mean PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio was lower in the aggregated disease groups (all cases) vs controls after 19.5 weeks of gestation for preeclampsia, 21 weeks for SGA neonates, and 27 weeks for preterm labor and PPROM; 3) when syndromes were subclassifed based on the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, differences in the mean PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio between cases and controls were greater and emerged earlier in gestation: at 18 weeks for preeclampsia, 20 weeks for SGA neonates, 22 weeks for preterm labor, and 25 weeks for PPROM; 4) at 28 to 32 weeks of gestation, the aOR of the association between an abnormal PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio and obstetrical syndromes in aggregate was 6.7 for preeclampsia, 4.4 for SGA neonates, and 2.1 for PPROM and preterm labor (all p<0.05); 5) the magnitude of the association doubled for obstetrical diseases with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, reaching 13.6 for preeclampsia, 8.1 for SGA neonates, 5.5 for PPROM, and 3.3 for preterm labor (all p<0.05); 6) in the absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, the associations between an abnormal PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio at 28 to 32 weeks of gestation and the obstetrical syndromes were 2- to 3-fold weaker and did not reach significance for preterm labor and PPROM.

Conclusion:

Classification of obstetrical syndromes according to the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion allows biomarkers to be informative earlier in gestation and enhances the strength of association between biomarkers and clinical outcomes. We propose that this new taxonomy of obstetrical disorders will facilitate the discovery and implementation of biomarkers as well as the prediction and prevention of such disorders.

Keywords: Angiogenic index-1, classification of disease, fetal death, liquid biopsy, omics, placental growth factor (PlGF), placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, preeclampsia, pregnancy, preterm birth, preterm labor, preterm PROM, small for gestational age (SGA), soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFLT-1), soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1)

INTRODUCTION

The outcome of pregnancy has improved in the last century due to the introduction of prenatal and intrapartum care, advances in the treatment of hemorrhage, infection, and preeclampsia as well as to the development of newborn intensive care units.1–3 Most of the progress in obstetrics and neonatology has leveraged knowledge generated in other fields of medicine to address the problems of pregnant women and neonates. Recent successes in obstetrics in the prevention of spontaneous preterm labor with midtrimester cervical length and progesterone4–10 and preeclampsia with first-trimester screening and aspirin11–13 suggest that early prediction and prevention are possible by combining the use of biomarkers to identify the patient at risk, coupled with an intervention. Yet, most complications of pregnancy remain difficult to prevent. We propose that a major obstacle to progress has been the current classification of obstetrical disease. A more rational approach for the prediction and prevention of obstetrical disorders should be based on the understanding of the causes and the mechanisms responsible for complications of pregnancy.14, 15

The current taxonomy of obstetrical disorders is largely based on symptoms and signs, which are inadequate descriptors of disease because they are nonspecific and, importantly, represent the late manifestations of pathologic processes. The terms “preterm labor,” “preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes” (PPROM), “preeclampsia,” “small for gestational age” (SGA), “fetal death,” “macrosomia,” etc, provide little information about the causes of these conditions,14, 15 which is reflected in therapeutic approaches that have been focused mainly on symptoms and signs (eg tocolysis to decrease uterine contractility or antihypertensive agents in preeclampsia) rather than on the underlying causes of disease.14,15

Advances in the understanding of the etiology and the diagnosis, prediction, treatment, and prevention of diseases in other fields of medicine have been made largely through the application of knowledge derived from anatomical pathology by analyzing tissues obtained from autopsies and biopsies.16–19 Such is the case, particularly in oncology, where molecular profiling of tumors allows the identification of biomarkers,20–24 key to clinical care.25–27 In obstetrics, examination of the placenta provides insight into the mechanisms of disease responsible for the pregnancy complications.28–41 This organ is key for successful pregnancy, is universally available after delivery, is a large human biopsy42 with fetal and maternal components,43 and has been considered “a diary of intrauterine life”.44, 45

We propose that a new taxonomy of obstetrical syndromes should be informed by results of pathologic examination of the placenta and that such taxonomy would facilitate the discovery of biomarkers to predict disease, thereby enabling preventive measures and treatment.

The two major placental pathologic processes responsible for adverse pregnancy outcome are of inflammatory46–55 or vascular nature.56–68 Successful reproduction requires profound adaptations of two maternal systems, cardiovascular and immunologic. Specifically, hemochorial placentation requires remodeling of the uterine circulation and, in particular, of the spiral arteries. Failure of transformation of the spiral arteries predisposes to placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion,69–72 which have been identified in virtually all major obstetrical syndromes.57–60, 73–76 Similarly, pregnancy imposes fundamental changes in the immune system to manage the risk of infection77–79 in the context of a semi-allogenic pregnancy. Abnormal microbial–host interactions or sterile inflammation can lead to acute and chronic inflammatory lesions of the placenta, often observed in spontaneous preterm labor,46, 48, 51, 52, 80–84 but also in other obstetrical syndromes, such as fetal death.85, 86 Biomarkers, eg interleukin (IL)-6 and CXCL10, are now available to diagnose patients with placental acute and chronic inflammatory lesions.47, 87–91 Yet, a major unmet need is the identification of biomarkers for vascular pathology at the maternal-fetal interface.

Ananth and Vintzileos proposed the term “ischemic placental disease” to refer to a cluster of conditions associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including preeclampsia, SGA, and placental abruption,92–94 and they estimated that one in every four preterm births results from these conditions.95 Maternal plasma concentrations of placental growth factor (P1GF) and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFlt-1), or a ratio of PlGF/sFlt-1, are biomarkers for the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion,96 the main pathologic finding in ischemic placental disease. An abnormal concentration of these biomarkers in the early second trimester is predictive of the subsequent delivery of a placenta with maternal vascular lesions of malperfusion.96 These lesions were reported in approximately 70% of all unexplained fetal deaths in the third trimester86,97–100 and with lesser frequency in preeclampsia,56, 101–104 SGA,102, 105, 106 preterm labor,60 and PPROM.59 Not surprisingly, P1GF and sFlt-1 concentrations are powerful biomarkers for unexplained fetal death in the third trimester107–110 and, to a lesser extent, of preeclampsia111–117 and fetal growth restriction.112, 118

The current study was conducted to determine whether PlGF, sFlt-1, and the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio in maternal blood differ among patients who present with preeclampsia, SGA, preterm labor, and PPROM with and without placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. To accomplish this goal, we first examined the change in the profile of these analytes in obstetrical syndromes defined only by clinical presentation; then, we disaggregated (or subclassified) cases according to the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. We hypothesized that differences in the mean concentrations of biomarkers between cases and controls would be larger and that the strength of association would be greater when information derived from anatomic pathologic examination of the placenta is considered.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Study design and participants

This retrospective case cohort study was based on a parent cohort of 4,006 pregnant women enrolled prospectively.96 The median gestational age at enrollment (interquartile range) was 12.3 (9–16.9) weeks. The case cohort (N=1,499) included 1,000 randomly selected patients from the parent cohort and all additional patients with obstetrical syndromes from the parent cohort. The large fraction (1000/4006=25%) of patients selected at random from the parent cohort surpassed the minimum recommended (15%) so that the risk estimates based on the case-cohort would be similar to those obtained based on the full parent cohort.119, 120 Patients were classified into six groups: 1) term delivery without pregnancy complications (n=540; control); 2) preterm labor (n=203); 3) PPROM (n=112); 4) preeclampsia (n=230); 5) delivery of an SGA neonate (n=334); some of these pregnancy complications co-occurred (see below); and 6) other pregnancy complications (n=182). Co-occurrence of syndromes included instances of preeclampsia with SGA (n=68), preterm labor with SGA (n=19), and PPROM with SGA (n=9), among others. Of note, the cohort also included 24 cases of fetal death. Of these cases, 13 were assigned to Group 6 (other obstetrical complications; Table 1), while the remainder of 11 cases were complicated by one or more obstetrical syndromes that are the primary focus in this study.

Table 1: Demographics characteristics of the study cohort (n=1,499).

| Term delivery controls (n=540){491} | Preterm labor (n=203){195} | Preterm PROM (n=112){109} | SGA (n=334){312} | Preeclampsia (n=230){216} | Other complications++ (n=182){173} | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 22(20-26) | 23(21-27)* | 25(21-30)* | 22(19-28) | 23(19-28) | 24(20-29)* |

| African American | 92.3%(n=453) | 92.8%(n=181) | 92.7%(n=101) | 95.2%(n=297) | 95.2%(n=219) | 91.2%(n=166) |

| Nulliparity | 36.5%(n=179) | 27.2%(n=53)* | 31.2%(n=34) | 43.9%(n=137)* | 46.1%(n=106)* | 45.1%(n=82)* |

| Weight (kg)+ | 70(59-82) | 66(57-82)* | 71(59-90) | 64(57-77)* | 77(64-98.2)* | 81(64-100)* |

| Height (cm) | 162.6(160-167.6) | 162.6(157.5-167.6) | 162.6(157.5-167.6) | 161.3(157.5-165.1)* | 165.1(157.5-167.6) | 162.6(158.1-170.2) |

| Body Mass Index (kg/m2) | 26(22.5-31.3) | 25.4(21.7-31.9) | 27.6(22.9-32.4) | 25(21.8-30.1)* | 28.9(23.8-35.7)* | 29.7(24.6-36.5)* |

| Smoking | 18.7%(n=92) | 21.5%(n=42) | 30.3%(n=33)* | 31.1%(n=97)* | 21.7%(n=50) | 18.1%(n=33) |

| Chronic hypertension | 0%(n=0) | 7.2%(n=14)* | 5.5%(n=6)* | 10.6%(n=33)* | 29.1%(n=67)* | 18.1%(n=33)* |

| Gestational hypertension | 0%(n=0) | 4.6%(n=9)* | 4.6%(n=5)* | 10.6%(n=33)* | 0%(n=0)* | 40.1%(n=73)* |

| GA at delivery (weeks) | 39.6(38.9-40.4) | 35(30-36.3)* | 34(30-35.4)* | 38.5(36.9-39.4)* | 37.4(35.9-39)* | 39(37.8-40.1)* |

| Birthweight (grams) | 3310(3072-3565) | 2330(1377-2662)* | 2080(1340-2500)* | 2387(2100-2635)* | 2805(2141.2-3268.8)* | 3280(3005-3588.8) |

| Number of longitudinal samples per patient | 5(5-6) | 4(3-6) | 4(3-6) | 5(4-6) | 5(4-6) | 5(5-6) |

| Gestational age at sample (weeks) | 28.1(21.1-34.4) | 24.4(19.1-29.6) | 24.7(19.3-29.7) | 26.7(20.3-33.9) | 26.6(20.4-32.8) | 26.9(20.7-34.1) |

Values are given as median (Interquartile Range) or number (percentage)

n= number of women with biomarker data.

{} number of women with biomarker data for whom the complete set of demographics characteristics listed were available GA: gestational age

represents significant difference compared to the Control group (p<0.05) assessed using Wilcoxon test for continuous data and Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Differences were not assessed for the last two variables.

Exclusion criteria included multiple gestations, active vaginal bleeding, severe maternal morbidity (eg renal insufficiency, congestive heart disease, and chronic respiratory insufficiency), active hepatitis, or known fetal chromosomal abnormalities and major congenital anomalies.

All study participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrollment, and they were followed until delivery. The use of clinical data and biological specimens obtained from these women for research purposes was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Wayne State University and the Institutional Review Board of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Clinical definitions

Preeclampsia was defined as new-onset hypertension and proteinuria developing after 20 weeks of gestation.121–123 Hypertension was defined as systolic ≥140 and/or diastolic ≥90 mmHg blood pressure, measured at least on two occasions, 4 hours to 1 week apart.122 Proteinuria was defined as a urine protein level ≥300 mg in a 24-hour urine collection, or two random urine specimens, obtained 4 hours to 1 week apart, showing ≥1+ by dipstick.122 Early preeclampsia was defined as preeclampsia resulting in a preterm delivery <34 weeks of gestation.124–126 Late preeclampsia was defined as preeclampsia resulting in a delivery ≥34 weeks of gestation.126 SGA neonates included in this study had a birthweight <5th percentile for gestational age at delivery, according to a US reference population.127 The diagnosis of PPROM was determined with a sterile speculum examination with documentation of either vaginal pooling or a positive nitrazine or ferning test. Spontaneous preterm labor was defined as the spontaneous onset of labor with intact membranes and delivery <37 weeks of gestation.

Sample collection and immunoassays for PlGF and sFlt-1

Blood samples from women at enrollment and during subsequent examinations scheduled every 4 weeks until the 24th week of gestation, and bi-weekly thereafter until delivery, were collected in tubes containing EDTA. Samples were centrifuged and stored at −70° C. Maternal plasma concentrations of PlGF and soluble vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 (sVEGFR-1, also known as sFlt-1) were determined by immunoassays, as described previously (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).114 The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation of the assays were 1.4% and 3.9% for sFlt-1 and 6.02% and 4.8% for PlGF, respectively. The sensitivity of each assay was 16.9 pg/ml for sFlt-1 and 9.5 pg/ml for PlGF. Laboratory personnel performing the assays were blinded to clinical information.

Placental pathology

Placentas were examined histologically according to standardized protocols by four perinatal pathologists who were blinded to clinical diagnoses and obstetrical outcomes, as described elsewhere.48, 128–130 Placental features consistent with maternal vascular malperfusion were diagnosed by using criteria established by the Perinatal Section of the Society for Pediatric Pathology128 and the Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group Consensus131 and included at least one of the following: 1) villous changes, which are further subdivided into abrupt onset (remote villous infarcts, recent villous infarcts), gradual onset with intermediate duration (increased syncytial knots, villous agglutination, increased intervillous fibrin), or gradual onset with prolonged duration (distal villous hypoplasia); and 2) vascular lesions (persistent muscularization of the basal plate arteries, mural hypertrophy of the decidual arterioles, acute atherosis of the basal plate arteries, and/or of the decidual arterioles).

Statistical analysis

Changes in biomarker concentrations with the clinical presentation and presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion: a longitudinal analysis

PlGF, sFlt-1, and the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio were first log-transformed 132 to stabilize variance along the gestational-age span. To estimate the mean biomarker concentrations in groups of patients as well as the differences between cases and controls, we utilized generalized additive models to fit the data as a function of spline transformation terms of gestational age at blood draw. These models allowed for a smooth relationship between the mean biomarker plasma concentrations and gestational ages while accounting for the within-subject correlated observations. Non-overlapping 95% confidence intervals (CI) of the mean biomarkers between cases and controls were considered to represent significant differences in mean values at a given gestational age. Generalized additive models were fit and evaluated with the mgcv and itsadug packages for the R statistical language and environment (www.r-project.org).

Calculation of multiples of the mean for gestational age and maternal characteristics

Multiples of the mean (MoM) values for maternal characteristics and gestational age were calculated for PlGF and sFlt-1 at 28 to 32 weeks of gestation, using data from the random set of 1000 pregnancies as previously described.133 MoM models were previously described for several intervals throughout gestation, yet the choice of the 28 to 32 weeks’ interval was informed by the results of the longitudinal analysis. In this analysis, missing information on nulliparity, maternal weight, and smoking status, affecting 11% of the patients, was imputed. MoM values were determined as the observed biomarker value for a given sample divided by the mean predicted by multiple regression. MoM cut-offs that define abnormal biomarker values for all conditions were selected as the 20th percentile (for PlGF or PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio) or the 80th percentile (for sFlt-1) of a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation estimated from the sample. The 20th and 80th percentile cut-off values were chosen to provide a sufficient number of cases with an abnormal PlGF/sFlt1 ratio for each syndrome and their respective sub-groups defined by the presence of placental lesions.

Cross-sectional analysis of biomarker Multiple of the Median (MoM) values

The association between obstetrical syndromes and abnormal biomarker profiles were determined by using as reference the pooled group of controls and those with “other complications” who had a live birth and a sample available at the 28 to 32 weeks’ interval. The resulting adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and 95% CIs obtained by logistic regression account for possible differences in gestational age at sampling and in maternal risk factors because the effects of these variables on biomarker data were removed during the calculation of MoM values. Relative risk estimates were also determined by robust Poisson regression134 with weighting of the data to reflect the parent cohort as previously described for this case-cohort.96 All analyses were carried out by using the R statistical language and environment (www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population

The frequency of major obstetrical syndromes in the parent cohort (n=4,006) was as follows: preeclampsia, 6% (n=230); SGA neonate <5th percentile in birthweight, 8.3% (n=334); preterm labor, 5% (n=203); and PPROM, 3% (n=112). The demographic characteristics of the case cohort study (n=1,499) are described in Table 1.

Women who presented with preterm labor or PPROM had a higher mean age than those in the control group (p<0.05, for both). Maternal weight was lower in women who had preterm labor or delivered an SGA neonate and higher in those who developed preeclampsia, compared to those in the control group (all, p<0.05). Moreover, women who developed preeclampsia or SGA had a higher rate of nulliparity, while those who developed preterm labor were more likely to be parous than those in the control group (all, p<0.05). Smoking was more common in patients with PPROM or SGA than those in the control group (all, p<0.05).

Frequency of maternal vascular lesions of malperfusion in the cases and the control group

The frequency of placental lesions consistent with maternal vascular lesions of malperfusion was 44% (96/224) in preeclampsia; 40% (128/334) in pregnancies with an SGA neonate; 30% (58/203) in cases of preterm labor; 27% (28/112) in cases of PPROM; 26% (45/176) in the group labeled as having “other complications of pregnancy;” and 15% (80/532) in the control group. Nulliparity was associated with an increase in risk for delivery of placentas with maternal vascular lesions of malperfusion (OR=1.3; 95% CI, 1.01–1.66; p=0.03), due to the higher rates of nulliparity in the preeclampsia and SGA groups in which such placental lesions were more frequent.

Biomarkers (PlGF, sFlt-1, and the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio) become informative earlier in gestation when patients are subclassified according to the presence or absence of lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion in placental pathology

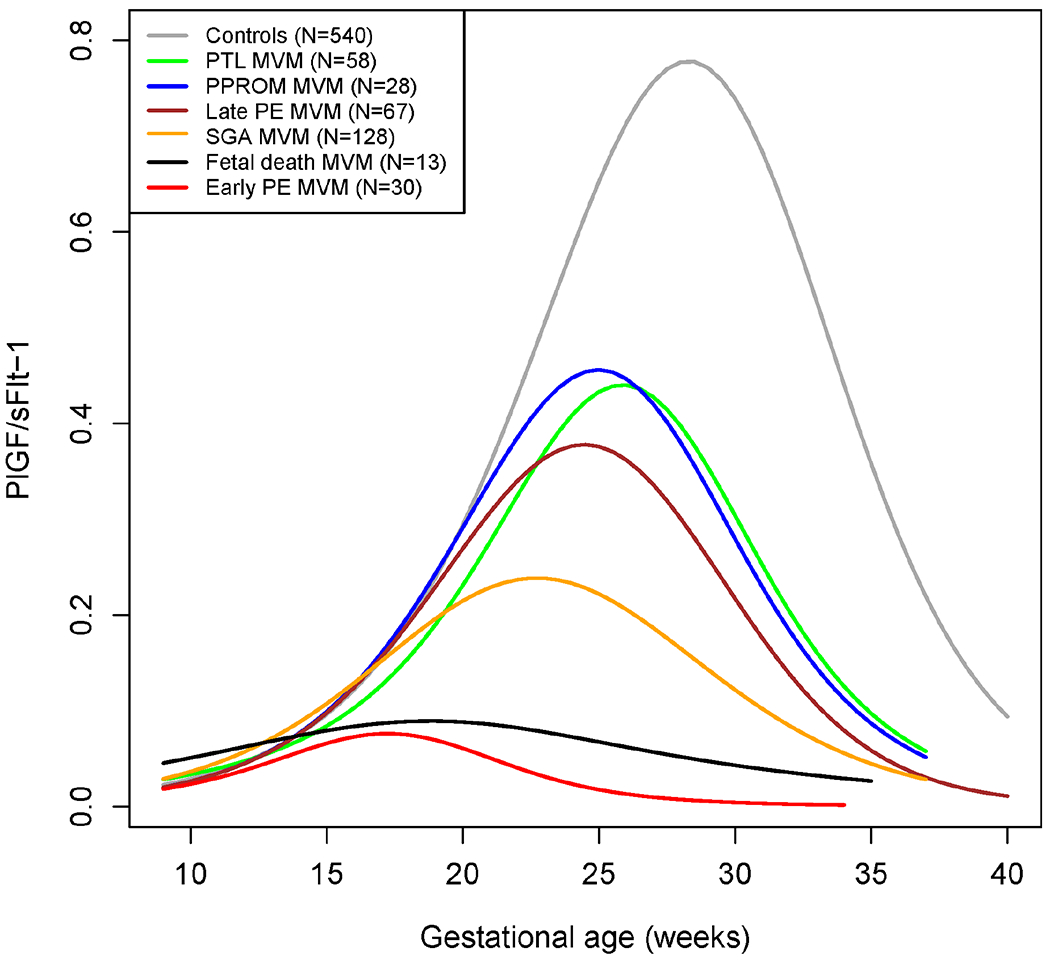

PlGF and sFlt-1 were measured in 7,560 maternal plasma samples collected throughout gestation from the 1,499 women in the study cohort (Table 1). The mean PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio was estimated as a function of gestational age by using generalized additive models. Longitudinal profiles differed by both clinical presentation and the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Maternal plasma PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio in normal and complicated pregnancies with and without placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion.

Mean and 95% confidence intervals values were estimated by generalized additive models using splines transformations of gestational age in term delivery controls and complicated pregnancies. PE: preeclampsia; SGA: small for gestational age; PTL: preterm labor and delivery; PPROM: preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes; MVM: placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. Dotted vertical lines represent the earliest gestational age when PlGF/sFlt-1 is significantly lower in cases than in controls.

The mean PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio was lower in patients who presented with complications of pregnancy than in those in the control group. The magnitude and timing at which differences were observed between cases and controls varied with the specific obstetrical syndrome and the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion (Figure 1). Patients who subsequently developed preeclampsia had a lower PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio, starting at 19.5 weeks of gestation; those with SGA at 21 weeks; and those with PPROM or preterm labor at 27 weeks (p<0.05, for all comparisons) (Figure 1, left column). However, when syndromes were classified (disaggregated) according to the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, differences in the mean PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio between the cases with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion and the controls were detected earlier in gestation: at 18 weeks for preeclampsia, 20 weeks for SGA, 22 weeks for preterm labor, and 25 weeks for PPROM (p<0.05, for all comparisons) (Figure 1, right column).

Importantly, when placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion were not present, there were no differences between preterm labor or PPROM cases and controls in the profile of a PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio at any time during gestation (Figure 1, right column). Even stronger conclusions regarding the benefit of disaggregation of obstetrical disease by the presence of placental lesions can be drawn based on the data of PlGF and sFlt-1 separately (Figures 2–3). For example, based on sFlt-1 analysis, differences between the preterm labor cases and the controls emerged at 25.5 weeks of gestation based on aggregated analysis but as early as 19 weeks in the disaggregated analysis (Figure 3). Moreover, only when SGA was disaggregated could we observe that a low first-trimester sFlt-1 concentration is a risk factor for future development of SGA, and a similar trend was noted for preeclampsia (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Maternal plasma PlGF ratio in normal and complicated pregnancies with and without placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion.

Mean and 95% confidence intervals values were estimated by generalized additive models using splines transformations of gestational age in term delivery controls and complicated pregnancies. PE: preeclampsia; SGA: small for gestational age; PTL: preterm labor and delivery; PPROM: preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes; MVM: placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. Dotted vertical lines represent the earliest gestational age when PlGF is significantly lower in cases than in controls.

Figure 3: Maternal plasma sFlt-1 ratio in normal and complicated pregnancies with and without placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion.

Mean and 95% confidence intervals values were estimated by generalized additive models using splines transformations of gestational age in term delivery controls and complicated pregnancies. PE: preeclampsia; SGA: small for gestational age; PTL: preterm labor and delivery; PPROM: preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes; MVM: placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. Dotted vertical lines represent the earliest gestational age when sFlt-1 is significantly higher in cases than in controls.

The magnitude of association between abnormal biomarkers and complications of pregnancy becomes greater after subclassification according to the presence or absences of maternal vascular lesions of malperfusion revealed by placental pathology

The aOR for the association between a low PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio at 28 to 32 weeks of gestation and obstetrical syndromes in aggregate were 6.7 for preeclampsia, 4.4 for SGA, and 2.1 for PPROM and preterm labor (all, p<0.05) (Figure 4, blue bars). The strength of association (measured by the OR) doubled for obstetrical diseases with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, reaching 13.6 for preeclampsia, 8.1 for SGA, 5.5 for PPROM, and 3.3 for preterm labor (all, p<0.05) (Figure 4, red bars). It is noteworthy, in the absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, that the associations between an abnormal PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio at 28 to 32 weeks of gestation and obstetrical syndromes were 2- to 3-fold weaker and did not reach significance for the preterm labor and PPROM groups (Figure 4, yellow bars). Similar findings were observed based on analysis results of PlGF and sFlt-1 separately (Figure 5 and Figure 6) and by using relative risk estimates and predictive performance metrics, such as the likelihood ratio of a positive or negative result (Table 2).

Figure 4: Adjusted odds ratios for obstetrical complications conferred by abnormal PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio at 28 to 32 weeks.

Results are presented for adverse outcomes in aggregate and disaggregated by presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion (MVM). A positive test was defined as MoM (PlGF/sFlt-1) <20th centiles. Significant associations (p<0.05) obtained via logistic regression are shown with (*). 95% confidence intervals are listed under estimates.

Figure 5: Adjusted odds ratios for obstetrical complications conferred by abnormal PlGF at 28 to 32 weeks.

Results are presented for adverse outcomes in aggregate and disaggregated by presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion (MVM). A positive test was defined as MoM PlGF <20th centiles. Significant associations (p<0.05) obtained via logistic regression are shown with (*). 95% confidence intervals are listed under estimates.

Figure 6: Adjusted odds ratios for obstetrical complications conferred by abnormal sFlt-1 at 28 to 32 weeks.

Results are presented for adverse outcomes in aggregate and disaggregated by presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion (MVM). A positive test was defined as MoM sFlt-1 >20th centiles. Significant associations (p<0.05) obtained via logistic regression are shown with (*). 95% confidence intervals are listed under estimates.

Table 2: Strength of the association between abnormal biomarkers and obstetric syndromes in aggregate and disaggregated by presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion.

| Cases | Controls | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Outcome | Outcome Type | Total | (+) test | Total | (+) test | aOR | aRR | Sensitivity | Specificity | (+) LR | (−) LR |

| sFlt-1 | PTL | All cases | 126 | 34 | 627 | 90 | 2.2(1.4-3.4) | 2.1(1.4-3.2) | 0.27(0.19-0.36) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 1.9(1.33-2.65) | 0.9(0.8-1) |

| sFlt-1 | PTL | with MVU | 33 | 13 | 627 | 90 | 3.9(1.8-8) | 3.8(1.8-7.7) | 0.39(0.23-0.58) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 2.7(1.72-4.37) | 0.7(0.5-0.9) |

| sFlt-1 | PTL | w/o MVU | 93 | 21 | 627 | 90 | 1.7(1-2.9) | 1.7(1-2.8) | 0.23(0.15-0.32) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 1.6(1.03-2.4) | 0.9(0.8-1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| sFlt-1 | PPROM | All cases | 74 | 21 | 627 | 90 | 2.4(1.3-4.1) | 2.3(1.4-3.9) | 0.28(0.19-0.4) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 2(1.31-2.98) | 0.8(0.7-1) |

| sFlt-1 | PPROM | with MVU | 19 | 8 | 627 | 90 | 4.3(1.6-11) | 4.3(1.7-10.7) | 0.42(0.2-0.67) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 2.9(1.67-5.14) | 0.7(0.5-1) |

| sFlt-1 | PPROM | w/o MVU | 55 | 13 | 627 | 90 | 1.8(0.9-3.5) | 1.8(1-3.4) | 0.24(0.13-0.37) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 1.6(0.99-2.75) | 0.9(0.8-1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| sFlt-1 | SGA | All cases | 248 | 67 | 627 | 90 | 2.2(1.5-3.2) | 1.4(1-1.9) | 0.27(0.22-0.33) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 1.9(1.42-2.49) | 0.9(0.8-0.9) |

| sFlt-1 | SGA | with MVU | 89 | 38 | 627 | 90 | 4.4(2.8-7.1) | 2.7(1.6-4.5) | 0.43(0.32-0.54) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 3(2.19-4.04) | 0.7(0.6-0.8) |

| sFlt-1 | SGA | w/o MVU | 159 | 29 | 627 | 90 | 1.3(0.8-2.1) | 0.9(0.6-1.5) | 0.18(0.13-0.25) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 1.3(0.87-1.86) | 1(0.9-1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| sFlt-1 | PE | All cases | 171 | 70 | 627 | 90 | 4.1(2.8-6) | 3.4(2.4-4.8) | 0.41(0.33-0.49) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 2.9(2.19-3.71) | 0.7(0.6-0.8) |

| sFlt-1 | PE | with MVU | 67 | 36 | 627 | 90 | 6.9(4.1-11.8) | 6.4(3.9-10.5) | 0.54(0.41-0.66) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 3.7(2.79-5.02) | 0.5(0.4-0.7) |

| sFlt-1 | PE | w/o MVU | 104 | 34 | 627 | 90 | 2.9(1.8-4.6) | 2.5(1.6-4.1) | 0.33(0.24-0.43) | 0.86(0.83-0.88) | 2.3(1.63-3.19) | 0.8(0.7-0.9) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PLGF | PTL | All cases | 126 | 22 | 627 | 83 | 1.4(0.8-2.3) | 1.4(0.8-2.2) | 0.17(0.11-0.25) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 1.3(0.86-2.03) | 1(0.9-1) |

| PLGF | PTL | with MVU | 33 | 7 | 627 | 83 | 1.8(0.7-4) | 1.7(0.7-4.1) | 0.21(0.09-0.39) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 1.6(0.81-3.19) | 0.9(0.8-1.1) |

| PLGF | PTL | w/o MVU | 93 | 15 | 627 | 83 | 1.3(0.7-2.2) | 1.2(0.7-2.2) | 0.16(0.09-0.25) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 1.2(0.74-2.02) | 1(0.9-1.1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PLGF | PPROM | All cases | 74 | 16 | 627 | 83 | 1.8(1-3.2) | 1.8(1-3.1) | 0.22(0.13-0.33) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 1.6(1.01-2.63) | 0.9(0.8-1) |

| PLGF | PPROM | with MVU | 19 | 7 | 627 | 83 | 3.8(1.4-9.8) | 3.8(1.5-9.7) | 0.37(0.16-0.62) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 2.8(1.49-5.18) | 0.7(0.5-1) |

| PLGF | PPROM | w/o MVU | 55 | 9 | 627 | 83 | 1.3(0.6-2.6) | 1.3(0.6-2.6) | 0.16(0.08-0.29) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 1.2(0.66-2.32) | 1(0.9-1.1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PLGF | SGA | All cases | 248 | 110 | 627 | 83 | 5.2(3.7-7.4) | 2.9(2.1-3.8) | 0.44(0.38-0.51) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 3.4(2.62-4.28) | 0.6(0.6-0.7) |

| PLGF | SGA | with MVU | 89 | 48 | 627 | 83 | 7.7(4.8-12.4) | 3.9(2.4-6.5) | 0.54(0.43-0.65) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 4.1(3.09-5.38) | 0.5(0.4-0.7) |

| PLGF | SGA | w/o MVU | 159 | 62 | 627 | 83 | 4.2(2.8-6.2) | 2.8(1.9-4.2) | 0.39(0.31-0.47) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 2.9(2.23-3.89) | 0.7(0.6-0.8) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PLGF | PE | All cases | 171 | 77 | 627 | 83 | 5.4(3.7-7.9) | 3.9(2.8-5.6) | 0.45(0.37-0.53) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 3.4(2.62-4.41) | 0.6(0.6-0.7) |

| PLGF | PE | with MVU | 67 | 41 | 627 | 83 | 10.3(6-18) | 9.3(5.6-15.5) | 0.61(0.49-0.73) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 4.6(3.51-6.1) | 0.4(0.3-0.6) |

| PLGF | PE | w/o MVU | 104 | 36 | 627 | 83 | 3.5(2.2-5.5) | 2.7(1.7-4.2) | 0.35(0.26-0.45) | 0.87(0.84-0.89) | 2.6(1.88-3.64) | 0.8(0.7-0.9) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PTL | All cases | 126 | 27 | 627 | 73 | 2.1(1.3-3.3) | 2(1.3-3.1) | 0.21(0.15-0.3) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 1.8(1.24-2.74) | 0.9(0.8-1) |

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PTL | with MVU | 33 | 10 | 627 | 73 | 3.3(1.5-7) | 3.2(1.5-6.9) | 0.3(0.16-0.49) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 2.6(1.49-4.56) | 0.8(0.6-1) |

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PTL | w/o MVU | 93 | 17 | 627 | 73 | 1.7(0.9-3) | 1.7(1-2.9) | 0.18(0.11-0.28) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 1.6(0.97-2.54) | 0.9(0.8-1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PPROM | All cases | 74 | 16 | 627 | 73 | 2.1(1.1-3.8) | 2(1.1-3.6) | 0.22(0.13-0.33) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 1.9(1.14-3.01) | 0.9(0.8-1) |

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PPROM | with MVU | 19 | 8 | 627 | 73 | 5.5(2.1-14.1) | 5.4(2.1-13.6) | 0.42(0.2-0.67) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 3.6(2.05-6.39) | 0.7(0.4-1) |

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PPROM | w/o MVU | 55 | 8 | 627 | 73 | 1.3(0.5-2.7) | 1.3(0.6-2.8) | 0.15(0.06-0.27) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 1.2(0.64-2.46) | 1(0.9-1.1) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | SGA | All cases | 248 | 91 | 627 | 73 | 4.4(3.1-6.3) | 2.5(1.8-3.4) | 0.37(0.31-0.43) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 3.2(2.4-4.13) | 0.7(0.6-0.8) |

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | SGA | with MVU | 89 | 46 | 627 | 73 | 8.1(5-13.2) | 4.2(2.5-6.9) | 0.52(0.41-0.62) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 4.4(3.31-5.96) | 0.5(0.4-0.7) |

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | SGA | w/o MVU | 159 | 45 | 627 | 73 | 3(2-4.6) | 2.2(1.5-3.3) | 0.28(0.21-0.36) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 2.4(1.75-3.38) | 0.8(0.7-0.9) |

|

| ||||||||||||

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PE | All cases | 171 | 80 | 627 | 73 | 6.7(4.5-9.9) | 4.7(3.3-6.7) | 0.47(0.39-0.55) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 4(3.07-5.26) | 0.6(0.5-0.7) |

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PE | with MVU | 67 | 43 | 627 | 73 | 13.6(7.9-24) | 12(7.1-20.2) | 0.64(0.52-0.76) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 5.5(4.17-7.29) | 0.4(0.3-0.6) |

| PLGF/sFlt-1 | PE | w/o MVU | 104 | 37 | 627 | 73 | 4.2(2.6-6.7) | 3.1(2-4.9) | 0.36(0.26-0.46) | 0.88(0.86-0.91) | 3.1(2.18-4.28) | 0.7(0.6-0.8) |

aOR: adjusted Odds Ratios; aRR: adjusted Relative Risk; LR: Likelihood Ratio; Estimates are provided with 95% confidence intervals. The largest estimates of aOR and aRR for a given biomarker and obstetrical syndrome are always for the subgroup with MVM lesions, and these are highlighted in bold. PTL: preterm labor; PPROM: preterm prelabor rupture of membranes; SGA: small for gestational age; PE: preeclampsia.

The profile of biomarkers throughout gestation in each obstetrical syndrome

The PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio in normal gestation reaches its peak at around 28 weeks of gestation, then decreases with advancing gestational age. The profile is different for each obstetrical syndrome with maternal vascular lesions of malperfusion, as shown in Figure 7 for PlGF/sFlt-1 and in Figure 8 for the inverse ratio sFlt-1/PlGF. The most abnormal profiles of the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio among cases with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion were observed for fetal death, early preeclampsia, and SGA (<5th percentile), with 20% of the cases in this latter group also complicated by preeclampsia. However, in patients with late preeclampsia, preterm labor, and PPROM, abnormalities were detectable only in the late-second and third trimesters. These findings have implications for the implementation of biomarkers. In other words, this knowledge can inform biomarker timing and threshold values for risk assessment of different syndromes as well as realistic expectations of their performance. Altogether, these findings demonstrate that subclassification of obstetrical syndromes, according to placental pathology findings, has important consequences for the discovery and implementation of biomarkers in clinical obstetrics.

Figure 7: Maternal plasma PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio in normal pregnancies and complicated pregnancies with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion.

Mean values were estimated by generalized additive models using splines transformations of gestational age. PE: preeclampsia; SGA: small for gestational age; PTL: preterm labor and delivery; PPROM: preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes; MVM: maternal vascular underperfusion.

Figure 8: Maternal plasma sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in normal pregnancies and complicated pregnancies with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion.

Mean values were estimated by generalized additive models using splines transformations of gestational age. PE: preeclampsia; SGA: small for gestational age; PTL: preterm labor and delivery; PPROM: preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes; MVM: maternal vascular underperfusion. A logarithmic axis was used to enhance visualization of differences between groups.

DISCUSSION

Principal findings of the study

The subclassification of obstetrical syndromes according to the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion 1) allows biomarkers in maternal blood (PlGF, sFlt-1, and PlGF/sFlt-1) to become informative earlier in gestation; 2) enhances the strength of association between abnormal biomarkers and clinical outcomes; and 3) uncovers syndromes in which PlGF was previously not known to be informative (ie preterm labor and PPROM). Therefore, these observations support the concept that a new nosology of obstetrical syndromes, which includes information about placental pathology findings, will enhance the discovery of biomarkers that, in turn, could improve the prediction and prevention of disease.

Results in the Context of What is Known

Maternal blood PlGF and soluble Flt-1 as biomarkers for preeclampsia

Pregnancy requires substantial changes in maternal vascular anatomy and physiology in order to provide adequate blood supply to the placenta and fetus, and this is partially accomplished through angiogenesis, which is regulated by a balance of growth factors (known as angiogenic and anti-angiogenic factors). The prototypic angiogenic factor is VEGF, which binds to its receptors135–137 and induces the proliferation of endothelial cells and tube formation.138 PlGF is a member of the VEGF family that was isolated from a cDNA library of a placenta at term.139 Several decades ago, investigators reported that the maternal plasma concentration of PlGF was lower in patients destined to develop preeclampsia than in patients with normal pregnancy outcome;140 however, the implementation of PlGF measurements to predict preeclampsia has been difficult due to false-positive and false-negative results.141–143 Indeed, a subset of patients with preeclampsia or even eclampsia do not have low concentrations of PlGF (or increased concentrations of the anti-angiogenic factors sFlt-1 or soluble endoglin).144, 145 Moreover, patients with an abnormal profile of angiogenic or anti-angiogenic factors may not develop preeclampsia; however, they could experience serious adverse pregnancy outcomes such as fetal death,107, 108 fetal growth restriction,112, 146–149 preterm labor,150, 151 and severe perivillous fibrin deposition,152 which often involve pathology of the supply line to the placenta and fetus.

Soluble Flt-1 (sFlt-1) is a splice variant of the VEGF receptor, fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (FLT 1), which lacks the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains and has important anti-angiogenic activity.137, 153, 154 The sFlt-1 binds free VEGF and PlGF in the maternal circulation. Syncytiotrophoblast and syncytial knots are sources of sFlt-1, and its concentration in the uterine vein in patients with preeclampsia is higher than in the peripheral circulation.155 We previously reported that sFlt-1 concentrations in maternal plasma are elevated in patients with preeclampsia,109, 112–115, 117, 155–158 fetal death,107, 108 massive perivillous fibrin deposition,152 SGA,112, 118, 149 mirror syndrome,159 and twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome.160 Moreover, recent reports suggest that patients with fetal parvovirus161 and cytomegalovirus infection162 may also have high maternal blood concentrations of sFlt-1. This is also the case in patients with molar pregnancy.163, 164

Maternal blood PlGF / sFlt-1 concentration ratio is a biomarker for the presence of maternal vascular malperfusion lesions in the human placenta

Vascular pathology is the most common mechanism of disease implicated in several obstetrical syndromes.57–62, 73–76, 165 We previously reported that the ratio of PlGF to sFlt-1 (which we referred to as the angiogenic index-1 in prior publications96, 110) is a biomarker for the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion.96 Women who delivered <34 weeks of gestation with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion had a lower maternal plasma PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio within 48 hours of delivery.96 Moreover, an angiogenic index-1 below the 2.5th percentile at 20-23 weeks of gestation identified 70% of women who delivered before 34 weeks of gestation with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion.96 Therefore, angiogenic index-1 represents the first prenatal biomarker for identifying placental lesions consistent with maternal vascular malperfusion. The lack of specificity of the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio for an obstetrical syndrome, such as preeclampsia, merely reflects that placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion are present also in other obstetrical syndromes and are not specific to preeclampsia.96

PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio is a predictor of unexplained fetal death in the third trimester and, in particular, in those cases associated with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion

A cross-sectional study showed that unexplained fetal death was associated with abnormally high concentrations of sFlt-1.107 Subsequent longitudinal studies have shown that a PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio at 30-34 weeks of gestation could identify patients at risk for fetal death and that the positive likelihood ratio of an abnormal PlGF/sFlt-1 was 14.109 Moreover, an abnormal ratio at 24 to 28 weeks of gestation also predicted unexplained fetal death in the third trimester, and when the endpoint was fetal death with placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, the likelihood ratio increased from 14 to 20.110 In other words, the test performs better when the endpoint includes not only the clinical presentation, fetal death, but also the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. A logical question which we tested in the current study, is whether similar findings would apply to other obstetrical syndromes, in particular, preeclampsia, SGA, and preterm labor with and without intact membranes.

PlGF, sFlt-1, and the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio in patients with preeclampsia, SGA, preterm labor, and PPROM: the effect of subclassification or disaggregation according to the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion

The analysis herein shows that in the absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, no differences in the maternal plasma PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio could be detected between patients with preterm labor or PPROM and gestational age-matched controls at any time during pregnancy. However, differences in the PlGF/sFlt-1 profiles emerged as early as 22 weeks for preterm labor and 25 weeks for PPROM if the cases had placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. This finding suggests that the association between an abnormal PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio and preterm labor and PPROM is mediated through the development of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. By contrast, for preeclampsia and severe SGA, differences between cases and controls are detected, regardless of the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. Yet, when lesions are present, the abnormality in PlGF/sFlt-1 profiles emerged about 5 weeks earlier for both conditions (Figure 1). The findings for the ratio also apply to the individual analytes as shown in Figure 2 (PlGF) and Figure 3 (sFlt-1).

The magnitude of the association between an abnormal PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio (after adjusting for maternal characteristics and obstetrical history) at 28 to 32 weeks of gestation and the occurrence of obstetrical syndromes were strengthened when the obstetrical disorders were disaggregated according to the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion (Figure 4). A PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio MoM <20th percentile was associated with PPROM (aOR=2.1); however, the magnitude of association increased (aOR=5.5) after subclassification of this syndrome by the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion. This was also the case for other syndromes: the association was strengthened when conditions were subclassified by the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion [SGA (aOR 8.1 vs 4.4), preeclampsia (aOR 13.6 vs 6.7), and preterm labor (aOR 3.3 vs 2.1)]. The findings were similar for PlGF and sFlt-1 alone (Figure 5 and Figure 6) using relative risk estimates rather than odds ratios (Table 2). Moreover, the results were consistent when using the 10th instead of the 20th percentile (PlGF) and the 90th instead of the 80th percentile (sFlt-1) as cut-off values to define an abnormal test result (data not shown).

Clinical implications

Obstetrical disorders are syndromic in nature,14, 15, 166, 167 and each disorder has multiple etiologies. In the case of preterm labor, the causes may include intra-amniotic infection,168–171 sterile intra-amniotic inflammation,172, 173 cervical disorders,174 a breakdown of maternal-fetal tolerance,51, 52, 175 etc, all of which can lead to the activation of the common pathway of parturition (myometrial contractility, cervical remodeling, and decidual/membrane activation).166, 167, 176 The terms “preterm labor with intact membranes,” “PPROM,” and “cervical insufficiency” merely describe the clinical presentation of asynchronous activation of the different components of the common pathway of parturition and therefore do not provide information about etiology.

Adequate blood supply to the placenta and fetus is essential for successful pregnancy. Therefore, it is not surprising that vascular pathology is the most frequent mechanism of disease in obstetrics. Lesions of vascular pathology are most frequently found in cases of fetal death,98, 177–179 preeclampsia,73, 84, 180, 181 SGA and fetal growth restriction,182–185 and abruptio placentae,186, 187 yet they have also been recognized in other obstetrical syndromes conventionally not considered to be predominantly of vascular origin (preterm labor,60, 188, 189 PPROM,59, 188, 190 and spontaneous abortion177, 191, 192). Biomarkers for placental vascular lesions can be expected to predict obstetrical syndromes caused by this pathologic process but not by other mechanisms of disease—eg, biomarkers of vascular disease should not be expected to reasonably identify the patient who would develop intraamniotic infection or other processes, such as immune-mediated mechanisms (ie alloimmunization or maternal anti-fetal rejection). Other molecules such as IL-6,47, 193, 194 IL-8,195–197 CXCL-10,87, 198 and CXCR-391 are putative biomarkers under these circumstances.

The diagnosis of vascular lesions requires histologic examination of the blood vessels. The human placenta is a large biopsy of maternal and fetal tissues and allows characterization of the presence and extent of vascular pathology. By examining the placenta, it is possible to classify obstetrical disorders according to the mechanisms of disease, which is essential in developing a more refined taxonomy of obstetrical disease and in aiding in biomarker discovery. We propose that subclassification or disaggregation of obstetrical syndromes according to placental pathology findings will create distinct groups that would be more homogeneous, which, in turn, could allow the discovery of more specific biomarkers informed by the mechanisms of disease of obstetrical disorders rather than by only symptoms and signs.

Research implications

The observation that syndrome subclassification or disaggregation by placental pathologic findings leads to stronger associations between biomarkers and obstetrical disease has several implications for research. First, studies of biomarker discovery require a precise endpoint. Most biomarker studies in obstetrics have aimed to predict obstetrical syndromes defined by symptoms and signs. These efforts have been uniformly unsuccessful or have led to claims that have not been replicated. We propose that defining obstetrical disorders by the combination of clinical presentation and placental pathology would generate more precise endpoints (often referred to as “phenotypes”) and that this would maximize the likelihood of biomarker discovery and assessment of true performance. For example, rather than attempting to predict all cases of spontaneous preterm labor, future studies should focus on the discovery of biomarkers to predict preterm labor associated with acute histologic chorioamnionitis (most often due to intra-amniotic infection) or chronic chorioamnionitis (the pathologic hallmark of maternal antifetal rejection). Such an approach has been successful in other areas of medicine (eg the likelihood of infection or sepsis can be assessed by inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6,199–203 transplant rejection with CXCL-10,204–206 and of recurrence with tumor markers such as alpha-fetoprotein207–210 or hCG211, 212). It is obvious that a universal biomarker for all pathologic processes does not exist and it is time that obstetrics, investigators, and funding agencies accept this reality.

Second, the conceptual framework advanced in this article can help to understand the apparent different behavior of biomarkers (eg PlGF, sFlt-1, alpha-fetoprotein and tumor necrosis factor alpha) among ethnic groups.213–217 It is possible that the different behavior of PlGF and sFlt-1 reflects the frequency and burden of maternal vascular lesions of malperfusion among groups.

Third, the findings reported herein suggest that current biomarkers may be used in novel ways to predict disease. For example, we noted that a lower sFlt-1 concentration in the first trimester is a risk factor for the subsequent development of SGA and possibly for preeclampsia. However, this observation was obscured when all cases (aggregated) were compared to controls, and this may apply to other biomarkers.

Fourth, biomarker discovery using omics approaches may be facilitated by syndrome subclassification. By comparing molecular profiles of cases with and, separately, without placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion to those of women with normal pregnancy, new subsets of biomarkers may emerge. For example, in a previously published longitudinal study that utilized proteomics in maternal blood, we found at 8 to 16 weeks of gestation that the maternal concentrations of matrix metalloproteinase-7 and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa were predictive of early preeclampsia.218 However, only when preeclampsia was subclassified according to the presence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 emerged as a predictor for early preeclampsia. Similar observations were made with other molecules such as singlec-6 [sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 6 at 22.1 to 32 weeks of gestation (Table 2 reported by Tarca et al218)].

The concept of obstetrical disorders as syndromes caused by multiple mechanisms of disease has begun to gain momentum as demonstrated by recent studies and thoughtful contributions by several groups, including the ELGAN Investigators229, Savitz,230 and Bujold.231–233 The work herein shows the value of the concept of disease subclassification by the presence of one or more lesions consistent with maternal vascular malperfusion. Importantly, a standardized approach (optimal sampling and quantitative assessment of the extent of the lesions) is key to avoid over-call or under-call of such lesions.234 We have provided evidence that the higher the number of placental lesions consistent with maternal vascular malperfusion, the greater the change of angiogenic and antiangiogenic markers.96 The premise that obstetrical disorders can be subclassified or disaggregated based on underlying pathophysiology as reflected by placental histologic examination can be expanded to include placental molecular signatures derived from bulk transcriptomics,219, 220 single-cell analysis,221 proteomics,222–225 and lipidomics.226–228 Non-invasive markers for early diagnosis of such disease sub-types may include not only blood markers but also those derived from other biological fluids and other types of data, such as those derived from imaging of the placenta.

Liquid biopsies to understand placental health and disease

At first, the proposal to incorporate placental pathology findings in the classification of obstetrical syndromes could appear not useful for the index pregnancy, given the organ is only available after delivery. However, progress in the understanding of the causes of disease, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease have been made possible due to the contributions of anatomical pathology—first, through autopsies, and only more recently, through biopsies. Indeed, autopsies do not help the deceased, but they have played a fundamental role in the advancement of medicine. Placental pathology has been shown to be the most informative tool for the understanding of fetal death and also to provide information to counsel patients about the risk of future pregnancies. It is now well established that some lesions, eg massive perivillous fibrin deposition152, 235, 236 and acute chorioamnionitis,237 tend to recur in subsequent pregnancies. The same is the case for the clinical cluster referred to as ischemic placental disease.94

The concept of a “liquid biopsy,” a test conducted on a sample of blood or another biological specimen (eg amniotic fluid,238, 239 cervico-vaginal fluid,240, 241 saliva,242 crevicular fluid,243 or urine244, 245) whose result can be used to infer pathologic changes in distant tissues (eg cancer)246, 247 or in other pathologic processes (eg atherosclerosis),248–250 is gaining momentum in contemporary medicine. We envision that liquid biopsies will provide a means to examine placental health and disease in real time, which is an unmet need in the field of reproduction. We propose that this can be accomplished by using omics techniques to interrogate differences in cell-free DNA,251–253 coding and non-coding RNA,221, 254–262 proteins,218, 225, 263–268 metabolites,269–273 and extracellular vesicles.274–282 The data presented herein suggest that the concept of the liquid biopsy based on the examination of maternal blood is imminently feasible, given that the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio not only can predict the occurrence of placental lesions but also obstetrical syndromes (eg fetal death and preeclampsia).

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of this study include the following: 1) the use of a longitudinal case-cohort design that allowed inclusion of all cases of interest from a cohort of 4,006 women; 2) all placentas underwent histologic examination by placental pathologists blinded to clinical information and pregnancy outcome; 3) the large number of PlGF and sFlt-1 measurements in patients who were serially sampled; and 4) the information is derived largely from an African-American population, which is often understudied, despite the higher burden of adverse pregnancy outcomes relative to other populations.283

Among the limitations of this study, we note the following: 1) some patients had samples collected in less than three gestational-age intervals; therefore, they were ineligible for the first sampling stage, which may have introduced a selection bias. However, we included a complete census of all patients from the parent cohort who developed any of the great obstetrical syndromes, regardless of the number of samples available, and the reference population was selected regardless of pregnancy outcome, greatly reducing the chance of differential selection bias; 2) missing data for some patient characteristics; and 3) insufficient observations to interrogate the differences between preterm and term preeclampsia and gestational-age subgroups for other obstetrical syndromes. Data and results herein are presented not only for PlGF and sFlt-1 separately but also for the combination of the two biomarkers via a ratio. For historical reasons, we have featured the PlGF/sFlt-1 ratio,112 while later reports have used sFlt-1/PlGF.284–287 However, the findings herein based on PlGF/sFlt-1 will also hold if the sFlt-1/PlGF ratio were to be used instead, by considering that women are at risk when the sFlt-1/PlGF is abnormally high. The assumption behind the use of either of the two ratios is that the decreases in PlGF will be as equally predictive of disease as the increase in sFlt-1. Yet, this assumption may not hold depending on the gestational age at measurement. Indeed, current risk prediction models involving maternal blood PlGF and sFlt-1 concentrations do not rely on ratios but use gestational age-dependent weighting of the evidence provided by each biomarker.133, 288

CONCLUSION

Classification of obstetrical syndromes according to the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion allows biomarkers to be informative earlier in gestation and enhances the strength of association between biomarkers and clinical outcomes. We propose that a new taxonomy of obstetrical disorders, which includes information derived from placental pathology, will facilitate the discovery and implementation of biomarkers in clinical practice to facilitate the prediction and prevention of such disorders.

Supplementary Material

Condensation.

Defining obstetrical syndromes based on the combination of symptoms, signs, and placental pathology improves disease characterization and facilitates biomarker discovery.

AJOG at a Glance.

A. Why was this study conducted?

The current taxonomy of obstetrical disease [eg preeclampsia, preterm labor, preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes, small-for-gestational-age fetus or neonate, fetal death, etc] is based exclusively on symptoms and signs. This study was undertaken to examine whether subclassification of obstetrical syndromes, according to the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, would facilitate the identification of biomarkers and improve their predictive performance.

B. What are the key findings?

When obstetrical syndromes are defined according to the combination of clinical signs and the presence or absence of placental lesions of maternal vascular malperfusion, rather than by clinical signs alone, a maternal blood biomarker (eg placental growth factor or sFlt-1) 1) becomes informative earlier in gestation; 2) has a higher adjusted odds ratio, indicating a stronger magnitude of association with the development of each obstetrical syndrome; and 3) becomes significantly associated with the development of preterm labor and preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes, conditions not previously thought to be predicted by such biomarkers.

C. What does this study add to what is already known?

We present evidence to support the generation of a new taxonomy of obstetrical syndromes in which conditions are defined by the combination of clinical symptoms and signs and indicators of disease pathophysiology, such as the presence or absence of placental lesions. Such taxonomy would improve the characterization of obstetrical disorders by including information about the mechanisms of disease, as reflected in placental pathology. We propose that this approach creates more homogeneous syndrome-subsets, which can facilitate the discovery and implementation of biomarkers, and provides a new framework to test therapeutic interventions and preventive strategies.

Funding:

This research was supported, in part, by the Perinatology Research Branch, , Division of Obstetrics and Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Division of Intramural Research, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (NICHD/NIH/DHHS); and, in part, with Federal funds from NICHD/NIH/DHHS under Contract No. HHSN275201300006C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Goldenberg RL, McClure EM. Maternal mortality. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;205:293–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Högberg U, Wall S. Secular trends in maternal mortality in Sweden from 1750 to 1980. Bull World Health Organ 1986;64:79–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Healthier mothers and babies. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999;48:849–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romero R Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2007;30:675–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH, Fetal Medicine Foundation Second Trimester Screening G. Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix. N Engl J Med 2007;357:462–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Romero R, Yeo L, Miranda J, Hassan SS, Conde-Agudelo A, Chaiworapongsa T. A blueprint for the prevention of preterm birth: vaginal progesterone in women with a short cervix. J Perinat Med 2013;41:27–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero R, Conde-Agudelo A, Da Fonseca E, et al. Vaginal progesterone for preventing preterm birth and adverse perinatal outcomes in singleton gestations with a short cervix: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:161–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conde-Agudelo A, Romero R. Vaginal progesterone to prevent preterm birth in pregnant women with a sonographic short cervix: clinical and public health implications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214:235–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romero R Spontaneous preterm labor can be predicted and prevented. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2021;57:19–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, et al. Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;38:18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberge S, Bujold E, Nicolaides KH. Aspirin for the prevention of preterm and term preeclampsia: systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218:287–93.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rolnik DL, Wright D, Poon LC, et al. Aspirin versus Placebo in Pregnancies at High Risk for Preterm Preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 2017;377:613–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolnik DL, Nicolaides KH, Poon LC. Prevention of preeclampsia with aspirin. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2022;226:S1108–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Romero R Prenatal medicine: the child is the father of the man. 1996. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2009;22:636–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Renzo GC. The great obstetrical syndromes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2009;22:633–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gal AA. In search of the origins of modern surgical pathology. Adv Anat Pathol 2001;8:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van den Tweel JG, Taylor CR. Introduction to the History of Pathology series. Virchows Arch 2010;457:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Tweel JG, Taylor CR. A brief history of pathology: Preface to a forthcoming series that highlights milestones in the evolution of pathology as a discipline. Virchows Arch 2010;457:3–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor CR. Milestones in Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Morphology. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2020;28:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golub TR, Slonim DK, Tamayo P, et al. Molecular classification of cancer: class discovery and class prediction by gene expression monitoring. Science 1999;286:531–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brenton JD, Carey LA, Ahmed AA, Caldas C. Molecular classification and molecular forecasting of breast cancer: ready for clinical application? J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7350–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mrózek K, Marcucci G, Paschka P, Whitman SP, Bloomfield CD. Clinical relevance of mutations and gene-expression changes in adult acute myeloid leukemia with normal cytogenetics: are we ready for a prognostically prioritized molecular classification? Blood 2007;109:431–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhou X, Lei L, Liu J, et al. A Systems Approach to Refine Disease Taxonomy by Integrating Phenotypic and Molecular Networks. EBioMedicine 2018;31:79–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarca AL, Romero R, Draghici S. Analysis of microarray experiments of gene expression profiling. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006;195:373–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmitz R, Young RM, Ceribelli M, et al. Burkitt lymphoma pathogenesis and therapeutic targets from structural and functional genomics. Nature 2012;490:116–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan JY, Choudhury Y, Tan MH. Predictive molecular biomarkers to guide clinical decision making in kidney cancer: current progress and future challenges. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2015;15:631–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins FS, Doudna JA, Lander ES, Rotimi CN. Human Molecular Genetics and Genomics - Important Advances and Exciting Possibilities. N Engl J Med 2021;384:1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Benirschke K, Burton GJ, Baergen RN. Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baergen RN, Burton GJ, Kaplan CG. Benirschke’s Pathology of the Human Placenta. Springer, Cham: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khong TY, Mooney EE, Nikkels PGJ, Morgan TK, Gordijn SJ. Pathology of the Placenta: A Practical Guide. Springer, Cham: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox H, Neil Sebire MBBSF. Pathology of the Placenta. Third Edition. Saunders; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.PINAR H The Human Placenta: Normal Developmental Biology. Core Curriculum Publishers, LLC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kay H, Nelson DM, Wang Y. The Placenta: From Development to Disease. Wiley-Blackwell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraus F, Redline R, Gersell D, Nelson M, Dicke J. Placental Pathology (Atlas of Nontumor Pathology). Washington, DC. The American Registry of Pathology; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heerema-McKenney A, Popek EJ, De Paepe ME. Diagnostic Pathology: Placenta. Amirsys, Inc, United States: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sebire NJ. Implications of placental pathology for disease mechanisms; methods, issues and future approaches. Placenta 2017;52:122–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faye-Petersen OM, Heller DS, Joshi VV. Handbook of Placental Pathology. CRC Press; 2nd edition 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vogel M, Turowski G. Clinical Pathology of the Placenta. De Gruyter; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton GJ, Barker DJP, Moffett A, Thornburg K. The Placenta and Human Developmental Programming. Cambridge University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gruenwald P The Placenta and Its Maternal Supply Line: Effects of Insufficiency on the Foetus. Springer Netherlands; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Power ML, Schulkin J. The Evolution of the Human Placenta. Johns Hopkins University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beaconsfield R, Birdwood G. Placenta : the largest human biopsy : based on papers from meetings at Harvard Medical School and the National Institutes of Health, November 1980, the Instituto Superiore di Sanita, Rome, and SCIP Research Unit, Bedford College, University of London. 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burton GJ, Jauniaux E. What is the placenta? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:S6 e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Altshuler G Some placental considerations in alleged obstetrical and neonatology malpractice. Leg Med 1993:27–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baergen RN. The placenta as witness. Clin Perinatol 2007;34:393–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim CJ, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Chaiyasit N, Yoon BH, Kim YM. Acute chorioamnionitis and funisitis: definition, pathologic features, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:S29–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim CJ, et al. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6: a sensitive test for antenatal diagnosis of acute inflammatory lesions of preterm placenta and prediction of perinatal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:960–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Redline RW, Faye-Petersen O, Heller D, et al. Amniotic infection syndrome: Nosology and reproducibility of placental reaction patterns. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2003;6:435–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heerema-McKenney A Defense and infection of the human placenta. APMIS 2018;126:570–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Palmsten K, Nelson KK, Laurent LC, Park S, Chambers CD, Parast MM. Subclinical and clinical chorioamnionitis, fetal vasculitis, and risk for preterm birth: A cohort study. Placenta 2018;67:54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim CJ, Romero R, Chaemsaithong P, Kim JS. Chronic inflammation of the placenta: definition, classification, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:S53–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim MJ, Romero R, Kim CJ, et al. Villitis of unknown etiology is associated with a distinct pattern of chemokine up-regulation in the feto-maternal and placental compartments: implications for conjoint maternal allograft rejection and maternal anti-fetal graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol 2009; 182:3919–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee J, Romero R, Dong Z, et al. Unexplained fetal death has a biological signature of maternal anti-fetal rejection: chronic chorioamnionitis and alloimmune anti-human leucocyte antigen antibodies. Histopathology 2011;59:928–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jacques SM, Qureshi F. Chronic chorioamnionitis: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Hum Pathol 1998;29:1457–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogge G, Romero R, Lee DC, et al. Chronic chorioamnionitis displays distinct alterations of the amniotic fluid proteome. J Pathol 2011;223:553–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Espinoza J, Romero R, Mee Kim Y, et al. Normal and abnormal transformation of the spiral arteries during pregnancy. J Perinat Med 2006;34:447–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Chaiworapongsa T, Hassan SS. Placental bed disorders in preterm labor, preterm PROM, spontaneous abortion and abruptio placentae. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2011;25:313–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, Romero R. The “Great Obstetrical Syndromes” are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kim YM, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, et al. Failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries in the placental bed in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;187:1137–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim YM, Bujold E, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Failure of physiologic transformation of the spiral arteries in patients with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2003;189:1063–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim YM, Chaemsaithong P, Romero R, et al. Placental lesions associated with acute atherosis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2015;28:1554–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Labarrere CA, DiCarlo HL, Bammerlin E, et al. Failure of physiologic transformation of spiral arteries, endothelial and trophoblast cell activation, and acute atherosis in the basal plate of the placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216:287 e1–87 e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ernst LM. Maternal vascular malperfusion of the placental bed. APMIS 2018;126:551–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Redline RW, Ravishankar S. Fetal vascular malperfusion, an update. APMIS 2018;126:561–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Redline RW, Ariel I, Baergen RN, et al. Fetal vascular obstructive lesions: nosology and reproducibility of placental reaction patterns. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2004;7:443–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wintermark P, Boyd T, Parast MM, et al. Fetal placental thrombosis and neonatal implications. Am J Perinatol 2010;27:251–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morgan TK, Tolosa JE, Mele L, et al. Placental villous hypermaturation is associated with idiopathic preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2013;26:647–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kliman HJ, Firestein MR, Hofmann KM, et al. Trophoblast inclusions in the human placenta: Identification, characterization, quantification, and interrelations of subtypes. Placenta 2021;103:172–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Redline RW, Boyd T, Campbell V, et al. Maternal vascular underperfusion: nosology and reproducibility of placental reaction patterns. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2004;7:237–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burton GJ, Woods AW, Jauniaux E, Kingdom JC. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta 2009;30:473–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brosens I, Puttemans P, Benagiano G. Placental bed research: I. The placental bed: from spiral arteries remodeling to the great obstetrical syndromes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:437–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Harris LK, Benagiano M, D’Elios MM, Brosens I, Benagiano G. Placental bed research: II. Functional and immunological investigations of the placental bed. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2019;221:457–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ogge G, Chaiworapongsa T, Romero R, et al. Placental lesions associated with maternal underperfusion are more frequent in early-onset than in late-onset preeclampsia. J Perinat Med 2011;39:641–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]