Abstract

Synthetic [Fe4S4] clusters with Fe–R groups (R = alkyl/benzyl) are shown to release organic radicals on an [Fe4S4]3+–R/[Fe4S4]2+ redox couple, the same that has been proposed for a radical-generating intermediate in the superfamily of radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) enzymes. In attempts to trap the immediate precursor to radical generation, a species in which the alkyl group has migrated from Fe to S is instead isolated. This S-alkylated cluster is a structurally faithful model of intermediates proposed in a variety of functionally diverse S transferase enzymes and features an “[Fe4S4]+-like” core that exists as a physical mixture of S = 1/2 and S = 7/2 states. The latter corresponds to an unusual, valence-localized electronic structure as indicated by distortions in its geometric structure and supported by computational analysis. Fe-to-S alkyl group migration is (electro)chemically reversible, and the preference for Fe vs. S alkylation is dictated by the redox state of the cluster. These findings link the organoiron and organosulfur chemistry of Fe–S clusters and are discussed in the context of metalloenzymes that are proposed to make and break Fe–S and/or C–S bonds during catalysis.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Members of the radical S-adenosyl-l-methionine (SAM) superfamily of enzymes1 perform a wide array of chemical reactions that support diverse cellular functions.2,3 The common intermediate in these processes is the highly reactive 5′-deoxyadenosyl radical (5′-dAdo•), which is generated from reductive homolysis of the S–C(5′) bond in SAM.2 The reducing equivalent is supplied by an [Fe4S4]+ cluster that binds SAM at one Fe site; the remaining three Fe centers are bound to the protein polypeptide via a highly conserved CX3CX2C motif. In addition to supplying an electron, the cluster may play a more intimate role in radical generation. Specifically, recent biochemical and spectroscopic studies have led to the characterization of a precursor to the 5′-dAdo• that is proposed to feature an Fe–C(5′) bond (Scheme 1A).4 This intermediate, termed ‘Ω,’ has subsequently been recognized across the radical SAM enzyme family,5,6 and related species have also been proposed in mechanisms of non-canonical radical SAM enzymes that release the 3-amino-3-carboxypropyl radical instead of the 5′-dAdo•.7 Both the structural identities8 and the roles of these intermediates in catalysis9 remain under investigation.

Scheme 1.

An organometallic intermediate proposed in mechanisms of radical SAM enzymes (A) and functional models thereof (B).

The transient nature of intermediate Ω has prevented its comprehensive characterization and limited our understanding of its formation, electronic structure, and reactivity patterns. To circumvent these challenges, our group has studied synthetic [Fe4S4]–R (R = benzyl, alkyl) clusters whose properties and reactivity are more amenable to thorough characterization.10–12 Although several such clusters have now been prepared and characterized, each features a four-coordinate alkylated Fe site10–12 (unlike Ω, which is thought to be at least five-coordinate); binding a fifth ligand results in a dramatically weakened Fe–C bond that readily undergoes homolysis to release radicals in an analogous fashion to the chemistry that occurs in radical SAM enzymes (Scheme 1B).12 Thus, as for intermediate Ω, the high reactivity of this five-coordinate intermediate has hampered its characterization. An additional limitation of these prior studies is that the clusters that undergo Fe–C bond homolysis generate radicals on an [Fe4S4]2+–R/[Fe4S4]+ redox couple (Scheme 1B; cluster charge states are tabulated in Table S1) whereas intermediate Ω is proposed to release the 5′-dAdo• on an [Fe4S4]3+–R/[Fe4S4]2+ redox couple.4 As such, two related objectives in our research have been to study clusters in which Fe–C bond homolysis occurs on an [Fe4S4]3+–R/[Fe4S4]2+ couple and to characterize intermediates featuring a higher-coordinate alkylated Fe center.

In this paper, we first demonstrate that organic radicals can be generated on an [Fe4S4]3+–R/[Fe4S4]2+ couple. Then, in attempts to characterize [Fe4S4]3+–alkyl clusters in which the alkylated Fe site has a high coordination number (≥ 5), we reveal an unexpected finding: that in the [Fe4S4]3+ core charge state, the alkyl group migrates from Fe to S in a two-electron reductive elimination reaction. We fully characterize this novel S-alkylated cluster and demonstrate the reversibility of alkyl-group migration. Lastly, we discuss the consequences of these findings in the context of both radical SAM and S transferase enzymes.

Results

Reaction pathways upon oxidizing [Fe4S4]–R clusters to the [Fe4S4]3+ core charge state

To test if organic radicals can be generated from the [Fe4S4]3+ state, we first attempted two-electron oxidation of two previously reported [Fe4S4]+ clusters: (IMes)3Fe4S4–CH2Ph (1–Bn; IMes = 1,3-dimesitylimidazol-2-ylidene) and (IMes)3Fe4S4–(CH2)7CH3 (1–Octyl), both of which had been shown to release organic radicals on an [Fe4S4]2+–R/[Fe4S4]+ couple upon addition of pyridine ligands to their one-electron oxidized, [Fe4S4]2+ forms (Scheme 1B).12 Indeed, reaction of 1–Bn with 2 equiv [Cp2Fe][BArF4] (ArF = 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl) in tetrahydrofuran (THF) results in the rapid and near-quantitative generation of bibenzyl (96 ± 5% yield) and [1–THF][BArF4]2 (98 ± 5% yield) within 1 min at room temperature (Scheme 2A; Fig. S10 and S65 for spectroscopic characterization of [1–THF][BArF4]2 and structural characterization of [1–Et2O][B(C6F5)4]2, an analogue of [1–THF][BArF4]2). Based on these results, we hypothesized that transiently generated [1–Bn][BArF4]2 binds THF at the apical Fe site, generating a reactive five-coordinate intermediate [1–Bn(THF)][BArF4]2 that quickly releases benzyl radical (Scheme 2A). Addition of 2 equiv [Cp2Fe][BArF4] to 1–Octyl generated only traces (~0.5%) of the radical dimerization product, hexadecane. The differences in reaction outcomes between 1–Bn and 1–Octyl may be due to the greater reactivity of 1° radicals over benzyl radicals (resulting in alternative pathways for free radical termination) and/or unproductive reactions that occur for 1–Octyl prior to Fe–C bond homolysis (vide infra). Regardless, these results demonstrate that organic radicals can be liberated from synthetic clusters in the [Fe4S4]3+ charge state, as has been proposed for radical SAM enzymes.

Scheme 2.

Radical generation on an [Fe4S4]3+–R/[Fe4S4]2+ redox couple via an intermediate with a five-coordinate Fe center.

We then sought to construct a more stable analogue of the intermediate that precedes Fe–C bond homolysis: [1–R(THF)]2+ (Scheme 2A). Our strategy was to combine the ether and alkyl donors into a chelating ligand, and for these purposes, we used the 3-methoxypropyl (MP) group (Scheme 2B). Treatment of (IMes)3Fe4S4–Cl (1–Cl) with 3-methyoxypropyl magnesium bromide gave (IMes)3Fe4S4–MP (1–MP), and oxidation of 1–MP with 1 equiv cobaltocenium ([Cp2Co][PF6] or [Cp2Co][BArF4]) in o-difluorobenzene (o-DFB) generated the [Fe4S4]2+ cluster [(IMes)3Fe4S4–MP]+ ([1–MP]+, anion = [PF6] or [BArF4], respectively) (Fig. 1A). The solid-state structure of [1–MP][BArF4] was determined from single-crystal X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. 1B) and established that the 3-methoxypropyl group binds as a monodentate ligand, with the ether group remaining unbound. The 1H NMR resonances for the α- and β-CH2 protons of the MP group in [1–MP][PF6] are shifted to 72.5 ppm and −3.4 ppm, respectively, which closely correspond to the chemical shifts for alkyl groups bound to [Fe4S4]2+ clusters previously reported by our group.10–12 In contrast, the γ-CH2 protons (at 3.4 ppm) and -CH3 protons (at 3.3 ppm) of the MP group display minimal paramagnetic shifting, indicating that they are not closely associated with the cluster. Based on these observations, we conclude that the ether group is not bound to the apical Fe site in solution.

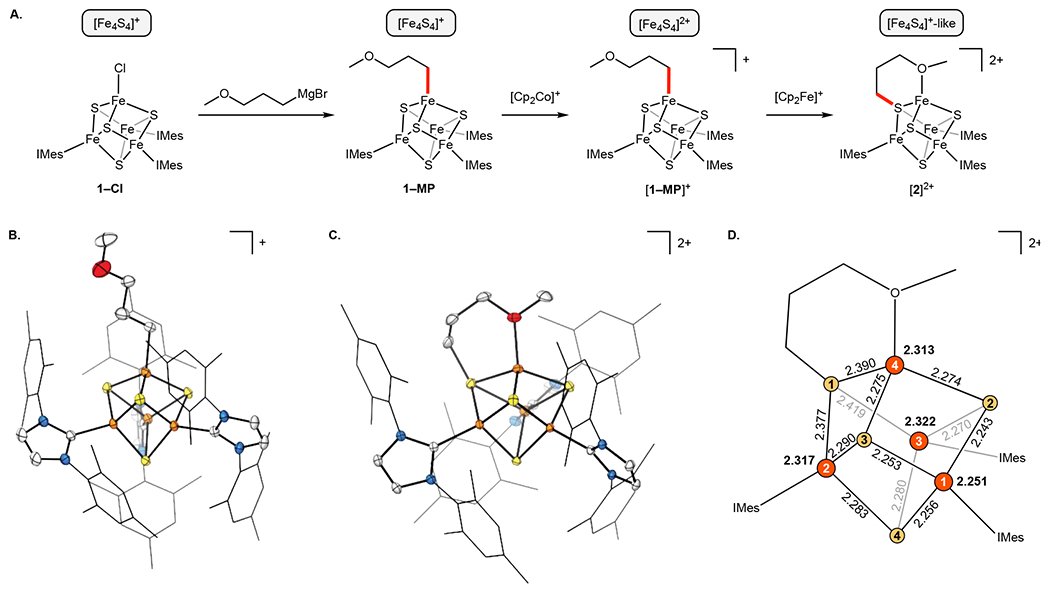

Figure 1.

Synthesis and characterization of 3-methoxylpropyl-ligated clusters. (A) Synthetic scheme. Panels (B) and (C) display thermal ellipsoid plots (50%) of [1–MP]+ and [2]2+, respectively. Hydrogen atoms, solvent molecules, and anions omitted for clarity. Fe (orange), S (yellow), O (red). N (blue), C (gray). (D) A schematic of the [Fe4S4] core of [2]2+ showing Fe–S distances in Å. Average Fe–S bond lengths for each site shown in bold. Standard uncertainties for bond distances omitted for clarity.

We next explored further oxidation of [1–MP]+. Treatment of [1–MP][PF6] (or [1–MP][BArF4]) with 1 equiv [Cp2Fe][PF6] (or [Cp2Fe][BArF4]) in o-DFB at −35 °C quickly produced a dark-red solution, the color of which persisted upon warming to room temperature. 1H NMR analysis of the reaction mixture revealed the generation of a species with unusually broad resonances between −4 and 13 ppm (Fig. S6, S8, S9). The new product slowly decomposes at room temperature (t1/2 ≈ 3 days in o-DFB; Fig. S11–S13) to a complex mixture of species. Nevertheless, in non-coordinating solvents, the degradation rate was sufficiently slow at −35 °C to grow single crystals by layering an o-DFB solution with fluorobenzene. Surprisingly, instead of obtaining an Fe-alkylated [Fe4S4]3+ cluster, single-crystal XRD analysis (Fig. 1C) revealed that the ether group of the MP ligand is now bound to Fe, and the alkyl ligand has migrated to an adjacent S site, forming the S-alkylated cluster [2][PF6]2. In [2]2+, the apical Fe is part of a six-membered ring featuring the methyoxypropane thiolate ligand whose μ3-thiolato group binds to two additional Fe sites. The observed S–C bond (1.837(2) Å) is unremarkable and falls within the typical range for alkane thiolates bridging two or more Fe centers.13–15

The conversion of transiently generated [1–MP]2+ to [2]2+ could occur by multiple mechanisms in which alkyl migration proceeds in a stepwise or a concerted fashion (Scheme 3). Given that solvent binding to [1–Bn]2+ rapidly releases benzyl radicals (Scheme 2A), it is reasonable to assume that intramolecular coordination of the ether group in [1–MP]2+ would generate the higher-coordinate intermediate (A) that undergoes Fe–C bond homolysis to generate a tethered 3-methoxypropyl radical (MP•) (in B). Recombination of the MP• with S instead of Fe would yield [2]2+. In this scenario, the net two-electron reductive migration of the MP group from Fe to S occurs in two, one-electron steps. Alternatively, the process could be concerted, occurring either directly from [1–MP]2+ or from intermediate A, thereby circumventing intermediate B.

Scheme 3.

Potential mechanisms of alkyl-group migration.

Because [2]2+ is structurally unprecedented in the synthetic [Fe4S4] cluster literature, and structurally homologous, S-functionalized [Fe4S4] clusters have been proposed as intermediates in a number of biological processes (see discussion),16–22 we undertook a detailed examination of the physical properties of [2]2+ and of the reversibility of the alkyl migration step (vide infra).

Characterization of [2]2+

Although [2]2+ is generated by oxidation of [1–MP]+, its Fe–S cluster core is formally more reduced because Fe-to-S alkyl-group migration is a two-electron reductive process. This is reflected in the 80 K Mössbauer spectra of the series 1–MP, [1–MP][PF6], and [2][PF6]2. Although none of the spectra can be simulated with a unique four-site model (see SI page 21 for further simulation details), the clusters’ average isomer shifts (δavg) inform on the average valences of the Fe ions. For 1–MP and [1–MP][PF6], δavg = 0.474 and 0.377 mm s−1 (Fig. 2), respectively, and the magnitude of the shift upon one-electron oxidation (a decrease of approximately 0.1 mm s−1) is consistent with a one-electron oxidation averaged over four Fe sites.23 In the absence of alkyl-group migration, a similar decrease in δavg would be expected upon further one-electron oxidation. Instead, the trend is reversed: δavg of [2][PF6]2 is 0.504 mm/s (Fig. 2), which is higher than that of [1–MP][PF6] and indeed similar to that of 1–MP. Thus, the Fe–S core of [2]2+ can be considered as “[Fe4S4]+-like”, consistent with its Fe oxidation states of 3×Fe2+ and 1×Fe3+ centers.

Figure 2.

Zero-field 57Fe Mössbauer analysis. (A) 80 K spectra of 1–MP, [1–MP][PF6] and [2][PF6]2 with δavg indicated. Experimental data (black circles) with fits shown as colored traces (see SI page 21 for fitting details). (B) Graphical depiction of δavg for 1–MP, [1–MP][PF6] and [2][PF6]2.

X-band EPR spectra of frozen solutions and microcrystalline solids of [2][PF6]2 show evidence for non-interconverting S = 1/2 and S = 7/2 spin systems whose ratios vary depending on the physical properties of the sample (vide infra). The 15 K spectrum of a sample prepared as a frozen solution in 9:1 o-DFB:toluene (Fig. 3A) reveals a dominant signal with g = [2.00, 1.96, 1.89] (gavg = 1.95; see Fig. S18 for simulation) that is consistent with an S = 1/2 spin system. In addition to this signal, a derivative-like feature is present at geff = 5.17 (Fig. 3A) as is an absorption-like feature at geff = 12.2; the latter is more evident in spectra of solid samples of [2][PF6]2 (Fig. 3B) and in spectra of poorly glassed frozen-solution samples (vide infra; Fig. S19). Comparison with computed rhombograms24 reveals that these two low-field features arise from transitions within an S = 7/2 spin system at an E/D ratio of ~0.10 (where D and E are the axial and transverse zero-field splitting parameters, respectively). Thus, the nearly isotropic signal at geff = 5.17 arises from transitions within the ms = |±3/2〉 Kramers doublet (gx, gy, and gz), while the feature at geff = 12.2 corresponds to gy of the ms = |±1/2〉 Kramers doublet. Transitions within other Kramers doublets of the S = 7/2 spin state are not visible due to their extreme breadth.24 The broadness of the features arising from the S = 7/2 state (Fig. S20), and the low intensity of the signal arising from the ms = |±1/2〉 Kramers doublet in particular, preclude an accurate determination of D in the current work, however the slower growth of the ms = |±1/2〉 doublet with increasing temperature relative to that of the ms = |±3/2〉 doublet indicates that D < 0 (Fig. S21). Note that similar EPR signals have been reported for the [Fe4S4] cluster in benzoyl Co-A reductase and attributed to an S = 7/2 spin system.25

Figure 3.

X-band (9.37 GHz) EPR characterization of [2][PF6]2. (A) Sample prepared as a frozen solution (9:1 o-DFB:toluene); 15 K; 40 μW. (B) Sample prepared as a crushed solid; 15 K; 160 μW. g-values indicated with arrows.

Whereas the EPR signals arising from the S = 7/2 spin state vary with temperature because of the changing population of ms states, the temperature-normalized spectra of the S = 1/2 signal are nearly superimposable (Fig. S19). This demonstrates that the S = 1/2 and S = 7/2 spin states are not interconverting on the EPR timescale and that, instead, samples of [2]2+ behave as physical mixtures of S = 1/2 and S = 7/2 states. Similar effects have been observed for [Fe4S4]+ clusters that exist as physical mixtures of S = 1/2 and S = 3/2 states.26–33 In addition, the ratio of the S = 1/2 and S = 7/2 signals can vary from sample to sample and exhibits a strong dependence on the solvent composition. Solvent combinations that give poorer glasses or that less efficiently solubilize [2]2+ tend to give a greater proportion of the S = 7/2 signal (Fig. S22). These observations suggest that the S = 7/2 state is favored in the solid state (including in aggregates formed upon freezing frozen solutions) and that the S = 1/2 state is favored in glassy, frozen solutions (as high as ~0.7 spins per cluster). Consistent with this proposal, the EPR spectrum of a solid sample of [2][PF6]2 features a dominant S = 7/2 signal, although both signals are significantly broadened (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these observations and the computational results discussed below indicate: (i) that the S = 7/2 and S = 1/2 states are both accessible for [2]2+; (ii) that these electronic isomers do not interconvert in the solid state or in frozen solution but rapidly interconvert in fluid solution at ambient temperature; (iii) that the two spin states correspond to a cluster with the same connectivity (namely, that revealed by XRD analysis) rather than to two different structures in solution (e.g., an S-alkylated and an Fe-alkylated cluster).

The S = 1/2 state of [2]2+ is typical of [Fe4S4]+ clusters and arises from antiferromagnetic coupling between an S = 9/2 [2Fe2.5+] pair (derived from parallel alignment of an Fe3+ ion and an Fe2+ ion that undergo valence delocalization by the double-exchange mechanism) and an S = 4 [2Fe2+] pair comprised of the remaining two spin-aligned Fe2+ sites (Fig. 4, left).34 The observed gavg is < 2 as is common for [Fe4S4]+ clusters.34,35 In contrast, the S = 7/2 spin state is more exotic. Although an octet state has been theoretically predicted to exist as one of several ground spin states for [Fe4Q4]+ clusters (Q = S or Se),35 it has so far only been spectroscopically observed in a few cases25,36–40 (and, relatedly, for the P-cluster of the Mo nitrogenase)41 and has not yet been observed for a structurally characterized [Fe4Q4]+ cluster. The electronic-structure basis for the S = 7/2 state is readily apparent from the crystal structure of [2]2+. As shown in Fig. 1D, the average Fe–S bond length at the Fe1 site (that which is not coordinated to the alkylated S site) is short: 2.251(2) Å (0.041(6) Å shorter than the average Fe–S bond length in the [Fe4S4]+ cluster 1–Bn),12 which we attribute to the localization of Fe3+ at this site. The remaining Fe sites are thereby localized Fe2+ centers because they are bound by a comparatively poorer μ3-thiolato ligand. Antiferromagnetic coupling between the Fe3+ center (S1 = 5/2) and the remaining three Fe2+ sites (aligned parallel with total spin S234 = 2 × 3 = 6; Fig. 4, right) gives Stot = S234 – S1 = 7/2, as is observed experimentally. This 3:1 spin-coupling pattern is consistent with the theoretical treatment of [Fe4S4]+ clusters with an S = 7/2 spin state35 and has been proposed to explain the magnetic properties of [Fe4Se4]+ and [Fe4S4]0 clusters (the latter with Stot = S234 – S1 = 6 – 2 = 4).38,42

Figure 4.

Spin-coupling patterns for the S = 1/2 (left) and S = 7/2 (right) states of [2]2+, specifically the BS34 and BS1 determinants, respectively. The bolded Fe–Fe axes represent spin aligned sets of Fe ions.

Valence localization in the S = 7/2 state is corroborated by broken-symmetry density functional theory (BS DFT) calculations. We first evaluated the relative energies of various BS determinants for [2]2+ by constraining the atomic coordinates to those observed crystallographically (the Mes groups were truncated to hydrogen, and the H-atom positions were optimized at the BP86/ZORA-def2-TZVP level; single-point energy calculations were performed at the TPSSh/DKH-def2-TZVP level; see SI page 48 for additional information). Among the four S = 7/2 BS determinants, the configuration in which Fe1 is in the minority spin (BS1) is the lowest in energy. Population analysis (see SI page 47) reveals that this corresponds to the electronic structure proposed based on the XRD analysis (vide supra): a localized Fe3+ site (Fe1) antiferromagnetically coupled to the remaining Fe2+ sites. This BS determinant is also 7.4 kcal/mol more favorable than the lowest-energy S = 1/2 BS determinant (see Table S5); the energetic preference for the S = 7/2 state using the crystal structure coordinates further supports our conclusion that the crystal structure represents the geometry of the S = 7/2 state.

Because the EPR spectrum of [2]2+ reveals both an S = 7/2 and an S = 1/2 signal, we were interested to learn if allowing the Fe–S core to relax in silico would result in the two states being closer in energy. We therefore conducted analogous BS-DFT calculations on partially optimized structures (Mes groups were truncated to hydrogen; Fe–Fe–C–N dihedral angles were fixed; geometry optimizations and energy calculations were performed at TPSSh/DKH-def2-TZVP level; see SI page 44–45 for additional information). The optimized structure using the S = 7/2 BS1 determinant is similar to that observed crystallographically, with short Fe–S distances around Fe1 (2.247 Å on average; Fig. S44). In contrast, the six BS determinants with an S = 1/2 spin state (BS12, BS13, BS14, BS23, BS24, BS34) all exhibit tetragonally compressed core structures and pairwise spin coupling (Table S6, Fig. S43, S48–S53 and Fig. 4, left), both of which are hallmarks of [Fe4S4]+ clusters with S = 1/2 ground states.43–46 In these fully optimized structures, the energies of the S = 1/2 BS determinants are still higher than that of the S = 7/2 BS1 determinant, but the gap is smaller than those in the unoptimized structures discussed in the preceding paragraph. Indeed, the S = 1/2 BS determinant with the lowest energy (BS34, with minority spin on Fe3 and Fe4) is only 2.7 kcal/mol higher than the S = 7/2 BS1 determinant. Due to the modest difference in computed energies, it is reasonable to expect that both spin states could be observed by EPR spectroscopy and that subtle perturbations from the environment (e.g., solvent interactions, glassing effects, etc.) could change the ratios of the two states, resulting in the occurrence of physical spin-mixtures. In contrast, because of the high homogeneity in a single-crystal lattice, only one state is observed crystallographically (specifically, the S = 7/2 spin state).

Assessing the reversibility of S-alkylation

Given that oxidation of [1–MP]+ triggers alkyl-group migration from Fe to S, we were interested to learn if the reverse reaction—alkyl-group migration from S to Fe—would occur upon reduction of [2]2+ (Fig. 5). Such a finding would build on prior work that has established the cleavage of S–C bonds at Fe–thiolate complexes,47–51 though in these examples the organic groups were lost as radicals instead of recombining with the complex to form an Fe–C bond. In the present study, we observed that treatment of [2][PF6]2 with 1 equiv Cp2Co in o-DFB at −35 °C for five minutes resulted in a color change to dark-brown. Examination of the solution by 1H NMR spectroscopy at room temperature showed complete consumption of [2][PF6]2 as evidenced by the disappearance of the characteristic peak at −2.3 ppm, and clean conversion to [1–MP][PF6] (with characteristic α- and β-CH2 protons of the MP group at 72.5 and −3.4 ppm, respectively; Fig. 5). Thus, [1–MP]+ and [2]2+ can be cleanly and reversibly interconverted by one-electron redox processes. Alkyl-group migration from Fe to S is therefore chemically reversible, with the preference for Fe vs. S alkylation depending on the redox state: Fe-alkylation is preferred at an [Fe4S4]2+ core whereas S-alkylation is preferred at an [Fe4S4]3+ core (to give an “[Fe4S4]+-like” core).

Figure 5.

Assessment of the chemical reversibility of redox-coupled interconversions of [1–MP]+ and [2]2+. 1H NMR spectra of isolated [1–MP][PF6] (top), isolated [2][BArF4]2 (middle), and the product from reduction of [2][PF6]2 using Cp2Co (bottom) recorded in d4-o-dichlorobenzene at room temperature.

To shed further light on these redox-coupled alkyl-group migration processes, we recorded cyclic voltammograms (CVs) of [1–MP][PF6] and [2][PF6]2 (henceforth denoted as [1–MP]+ and [2]2+ for simplicity). The CV of [1–MP]+ in the potential range of −1.0 V to −2.0 V features a reversible event at −1.54 V that corresponds to the [1–MP]+/1–MP redox pair (Fig. S35 and S36; all potentials referenced to Cp2Fe/[Cp2Fe]+).10–12 More interestingly, sweeping positively reveals an irreversible wave with a peak potential of ca. –0.3 V that arises from oxidation of [1–MP]+ (Fig. 6A). The return sweep displays a new event at ca. −0.9 V that becomes more reversible with increasing scan rate (Fig. 6A) and only appears if the CV is first swept positively past the wave at ca. −0.3 V (Fig. S37). Additionally, the same quasi-reversible feature is observed in the CV of [2]2+ when swept in the negative direction (Fig. 6B). We therefore assign this redox event, observed in CVs of both [1–MP]+ and [2]2+, to the [2]+/[2]2+ redox couple. As such, the irreversible wave at ca. –0.3 V observed in the positive sweep of [1–MP]+ corresponds to the oxidation-induced transformation of [1–MP]+ to [2]2+. Note that the same irreversible wave at ca. –0.3 V is observed in the CV of [2]2+ after sweeping negatively through the [2]+/[2]2+ redox couple because, under these conditions, in-situ generated [2]+ is partially converted to [1–MP]+. The sweep-rate dependence in the CV of [2]+ (Fig. 6B) is consistent with this interpretation; at slower sweep rates, the return wave of the [2]+/[2]2+ redox couple (at ca –0.8 V) is diminished, and that of the [1–MP]+/[2]2+ couple (at ca. –0.3 V) is enhanced because a greater proportion of [2]+ has rearranged to [1–MP]+. Taken together, these data enable the complete assignment of the CVs of [1–MP]+ and [2]2+. They also demonstrate that the rearrangement upon reduction of [2]2+ to [1–MP]+ occurs on the CV timescale, whereas the rearrangement upon oxidation of [1–MP]+ to [2]2+ is sufficiently fast that the [1–MP]+/[1–MP]2+ couple cannot be observed (at scan rates up to 2 V sec−1; Fig. S38).

Figure 6.

Cyclic voltammetry experiments and analysis. (A) CV plots of [1–MP]+. The slowest scans (25 mV/s) are shown in blue and the fastest scans (500 mV s−1) are shown in red. Other scan rates (50, 100, 150, 200, 300 and 400 mV s−1) are shown in gray. The starting scanning directions and positions are labeled with black arrows. (B) CV plots of [2]2+ with the same formatting as in (A). (C) Square scheme for the redox-coupled alkyl-group migration. (D) CV plot of [2]2+ recorded at 2.5 mV s−1. All CV experiments were referenced to Cp2Fe/[Cp2Fe]+ and performed in o-DFB with 0.5 M [Bu4N][PF6] supporting electrolyte at 2 mM [cluster] at room temperature.

Having assigned the features in the CVs of [1–MP]+ and [2]2+, we next considered the thermodynamics of these redox-coupled alkyl-group migrations. The equilibrium constants for the two redox-decoupled rearrangements (KAC, defined as [C]/[A], and KBD, defined as [D]/[B]; Fig. 6C) are connected to the redox couples, E1° and E2°, corresponding to equations (1) and (2) below:

| (1) |

| (2) |

Because the redox interconversion of [2]2+ and [2]+ is quasi-reversible, a value of E2° ≈ −0.90 V can be estimated from the mid-peak potentials in the CVs recorded at fast scan rates. In contrast, the irreversibility of the oxidation of [1–MP]+ precludes a reliable determination of E1°. However, E1° can be estimated from analysis of the CV of 1–Bn, which exhibits a quasi-reversible [1–Bn]+/[1–Bn]2+ couple when recorded in non-coordinating solvent (o-DFB) with a weakly coordinating electrolyte ([nPr4N][BArF4]; Fig. S39). Based on this analysis, we estimate E1° for the [1–MP]+/[1–MP]2+ couple to be −0.26 V.

The thermodynamic potential for the overall equilibrated system,

| (3) |

is defined as EK° and can be related52,53 to the standard potentials and the equilibrium constants, KAC and KBD, according to the relationships

| (4) |

| (5) |

when KAC << 1 and KBD >> 1 (or, ΔGAC >> 0 and ΔGBD << 0, respectively, as is the case in our system). EK° can in principle be used to derive the equilibrium constants for the redox-decoupled rearrangements, and its value is typically obtained by reading the center position of a reversible redox pair from a fully equilibrated system observed at sufficiently slow sweep rates.53,54 However, even at very slow sweep rates (e.g., 2.5 mV sec−1 for the CV of [2]2+; Fig. 6D), a fully equilibrated system is not achieved as evidenced by the wide separation and slow convergence of the two redox pairs (Fig. S40, S41). Nevertheless, we can still determine the upper and lower limits of the rearrangement free energies, ΔGBD and ΔGAC, using the relationship

| (6) |

At the limit of ΔGBD = 0,

| (7) |

where n = 1 (corresponding to the number of electrons transferred) and F is Faraday’s constant.

Likewise, at the limit of ΔGAC = 0,

| (8) |

Since neither ΔGBD nor ΔGAC is near zero, it is likely that both |ΔGBD| and |ΔGAC| are substantially lower than 15 kcal mol−1. Regardless, the foregoing CV analysis provides a range for the free-energy change of alkyl-group migration in both the cationic and dication states, as well as a qualitative indication of the rates of these processes.

Trapping intermediates upon oxidation of clusters featuring non-chelating alkyl groups

Alkyl-group migration in the transformation of [1–MP]+ to [2]2+ is accompanied by binding of the ether group to the formerly alkylated Fe site, and the thermodynamics of this rearrangement are impacted in part by the stabilization afforded by the formation of the six-membered ring in [2]2+ (or, conversely, by destabilization if there is significant ring strain). We were therefore interested to learn if S-alkylated clusters can be generated in the absence of a chelating alkyl group.

We began by reexamining two-electron oxidation of clusters 1–R (where R is the non-chelating benzyl or octyl group; vide supra). In particular, we attempted to trap intermediates via freeze-quench techniques and to analyze the products by EPR spectroscopy. Samples generated by freezing mixtures of 1–Bn and 2 equiv [Cp2Fe][BArF4] after incubating in THF at −78 °C for ~1 min display no EPR signals; apparently, the Fe–C bond is sufficiently weak that no Fe- or S-alkylated species can be observed under these conditions. This is also consistent with the generation of [1–THF][BArF4]2 (vide supra), which is diamagnetic and therefore EPR-inactive. In contrast, when 1–Octyl samples are prepared under identical conditions, a new S = 1/2 EPR signal is observed (0.13 spins per equiv of starting 1–Octyl; Fig. 7C) with a g-tensor (g = [1.99, 1.96, 1.91]) very similar to that of the S = 1/2 signal of isolated [2]2+ (g = [2.00, 1.96, 1.89]). Accompanying this spin-doublet signal, a small derivative-like signal was also detectable at geff = 5.17 (Fig. 7B), a characteristic geff value for an S = 7/2 system with E/D near 0.10 (also akin to that observed for [2]2+). Similar S = 1/2 signals were observed when conducting the same oxidation in 2-MeTHF or mixtures of THF and 2-MeTHF, and small perturbations to the EPR signals were apparent when the composition of the solvent mixture was changed (see SI page 30–31), indicating that solvent is coordinated to the cluster in the trapped intermediate (as depicted in Fig. 7A, top). Taken together, these EPR results demonstrate that the S-alkylated cluster [3]2+ forms in the presence of donor solvents (Fig. 7A, top), and we therefore conclude that the generation of S-alkylated Fe–S clusters does not require a chelating alkyl group.

Figure 7.

Fe- and S-alkylated species trapped in freeze-quench EPR studies. (A) Solvent dependence of reaction outcome in the two-electron oxidation of 1–Octyl. EPR spectra of [2]2+, [3]2+, and [1–Octyl]2+ in the low-field (B) and mid-field (C) regions. Spectra recorded at 15 K, 9.37 GHz, and 40 μW (for [2]2+ and [3]2+) or 10 μW (for [1–Octyl]2+).

Alkyl-group migration to S does, however, require a donor ligand. A markedly different S = 1/2 EPR signal (with g = [2.18, 2.03, 1.98]) was observed upon two-electron oxidation of 1–Octyl in the non-coordinating solvent o-DFB, corresponding to 0.36 spins per equiv 1–R (Fig. 7C, S30); a similar EPR signal was observed upon two-electron oxidation of 1-Bn in o-DFB (Fig. S34). Notably, the signals feature gavg > 2, which is characteristic of [Fe4S4]3+ clusters55–60 including Fe-alkylated [Fe4S4]3+ intermediates proposed in biological systems4,5,7 and synthetic models thereof.11 We therefore assign the species generated in o-DFB to the clusters [1–Octyl]2+ and [1–Bn]2+, which feature four-coordinate, alkylated/benzylated Fe sites (Fig. 7A, bottom). Thus, in the absence of a donor solvent, no R group migration occurs due to the absence of a suitable ligand for the Fe site, whereas in coordinating solvents like THF, an S-alkylated dicationic cluster forms with THF bound to the apical Fe site ([3]2+; Fig. 7A, top).

Discussion

In this work, we have demonstrated the facile and reversible migration of alkyl groups between Fe and S in synthetic [Fe4S4] clusters, and we now relate these findings to mechanistic proposals for [Fe4S4] enzymes. First, we note that [2]2+ is a high-fidelity structural model for several intermediates in S transferase enzymes. For example, in lipoic acid biosynthesis, LipA catalyzes the insertion of two S atoms into unactivated C–H bonds of a protein-bound n-octanoyl chain;61–65 in this reaction, the two S atoms derive from an [Fe4S4] cluster that is cannibalized during catalysis.17,19,20 The first S–C bond forms when a 2° carbon radical attacks the [Fe4S4] cluster to generate an S-alkylated [Fe4S4] cluster that loses Fe to form an S-alkylated [Fe3S4] cluster (Fig. 8A). Similar S-methylated [Fe4S4] and [Fe3S4] intermediates have been proposed in reactions performed by alkylthiotransferases21,22 such as MiaB and RimO as well as the nitrogenase maturase NifB, which is proposed to generate the central carbide in nitrogenase cofactors via an S-methylated intermediate (Fig. 8B).16,18,66,67 In the latter, the S-bound C atom eventually migrates to Fe, a process that is conceptually related to the alkyl-group migration reactions reported herein. The discovery and characterization of [2]2+ therefore supports the plausibility of S-alkylated intermediates in several Fe–S enzymes that serve a variety of cellular functions.

Figure 8.

Proposed enzymatic intermediates that feature S–C bonds at [Fe4S4] and [Fe3S4] clusters. (A) Mechanism of the first S–C bond-forming step in LipA. (B) Structures of methylated intermediates proposed for methiothiotransferases and in nitrogenase maturation.

The reversibility of S-alkylation is also noteworthy in this context. We observed rapid migration from S to Fe in the reduction of [2]2+ to [1–MP]+, and, by analogy, it would be reasonable to assume that reduction of enzymatic S-alkylated [Fe4S4] intermediates could likewise induce S-to-Fe alkyl-group migration. However, this appears not to take place, and one mechanism for preventing such processes could entail the rapid loss of Fe after S-alkylation of [Fe4S4] clusters (or, in some cases, before S-alkylation), as has been proposed in mechanisms for LipA (Fig. 8A), MiaB, and RimO.17,19,21,22 Thus, Fe loss may not be an incidental feature of these mechanisms, but instead a critical step to prevent alkyl migration to Fe and favor productive organosulfur chemistry.

The characterization here of reasonably stable S-alkylated [Fe4S4] clusters raises the question of why SAM-derived organoiron—but not organosulfur—intermediates have been observed in radical SAM enzymes. Indeed, our findings indicate that, in the absence of steric constraints imposed by the polypeptide, S-alkylation may be favored over Fe alkylation in the [Fe4S4]3+ state. Thus, it is likely that the active site geometry in radical SAM enzymes disfavors S–C bond formation. It is also possible that S-alkylated [Fe4S4] intermediates will be characterized in future studies of a radical SAM enzyme (observed, for example, under non-native reaction conditions, using non-native substrates, and/or in a protein mutant with a more open active site that increases the steric accessibility at S), and our work provides spectroscopic signatures that can be used to identify such species.

Lastly, our findings highlight the exceptional weakness of Fe–C bonds in [Fe4S4] clusters featuring alkylated Fe sites with high (> 5) coordination numbers. In the [Fe4S4]3+ state, we were able to trap species featuring a four-coordinate Fe–alkyl site (in the absence of an external ligand) or products of S-alkyl migration (in the presence of an internal or external ligand); in no cases have we observed the likely intermediate in these reactions: an [Fe4S4]3+ cluster featuring a 5-coordinate, alkylated Fe center. The favorability of Fe-to-S alkyl migration in this redox state speaks to both the stability of the S-alkylated species in the absence of a protein environment and the instability of the Fe-alkylated species. Given this unexpected reaction pathway, new strategies will be required to generate [Fe4S4] clusters with Fe-alkylated sites having a coordination number > 4.

Conclusion

We have shown that organic radicals can be generated on the same redox couple as has been proposed for radical SAM enzymes, [Fe4S4]3+–R/[Fe4S4]2+, in quantitative yield for the relatively stable benzyl radical and low yield for a reactive 1° radical. In our attempts to trap the key Fe-alkylated intermediate in this process, we made an unexpected discovery: in this small-molecule, synthetic system (i.e., one in which the cluster is not constrained by a protein active site), alkyl groups migrate from Fe to S in a net two-electron reductive elimination. The resulting S-alkylated [Fe4S4]+-like cluster was characterized, its spectroscopic signatures were elucidated, and its electronic structure was rationalized. We also showed that Fe-to-S migration is reversible upon re-reduction to the [Fe4S4]2+ state, and therefore that the regioselectivity of cluster alkylation can be controlled by the cluster’s redox state. This work connects the organoiron and organosulfur chemistry of Fe–S clusters, highlights the ease with which Fe–C and S–C bonds can be interchanged at Fe–S clusters, and lends credence to the intermediacy of S-alkylated intermediates in S transferase reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank N. B. Lewis, M. L. Pegis, and Y. Surendranath for helpful discussions, as well as P. Müller for assistance with XRD experiments. This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01GM136882. A.C.B. acknowledges fellowships from the National Science Foundation (Graduate Research Fellowship #1122374) and the Fannie and John Hertz Foundation.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supporting information

Experimental methods, spectroscopic data, and supplementary analysis.

References

- (1).Holliday GL; Akiva E; Meng EC; Brown SD; Calhoun S; Pieper U; Sali A; Booker SJ; Babbitt PC Atlas of the Radical SAM Superfamily: Divergent Evolution of Function Using a “Plug and Play” Domain. Methods Enzymol. 2018, 606, 1–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Broderick JB; Duffus BR; Duschene KS; Shepard EM Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes. Chem. Rev 2014, 114, 4229–4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Landgraf BJ; McCarthy EL; Booker SJ Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Enzymes in Human Health and Disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem 2016, 85, 485–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Horitani M; Shisler K; Broderick WE; Hutcheson RU; Duschene KS; Marts AR; Hoffman BM; Broderick JB Radical SAM Catalysis via an Organometallic Intermediate with an Fe-[5′-C]-Deoxyadenosyl Bond. Science 2016, 352, 822–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Byer AS; Yang H; McDaniel EC; Kathiresan V; Impano S; Pagnier A; Watts H; Denler C; Vagstad AL; Piel J; Duschene KS; Shepard EM; Shields TP; Scott LG; Lilla EA; Yokoyama K; Broderick WE; Hoffman BM; Broderick JB Paradigm Shift for Radical S- Adenosyl- l -Methionine Reactions: The Organometallic Intermediate Ω Is Central to Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 8634–8638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Balo AR; Caruso A; Tao L; Tantillo DJ; Seyedsayamdost MR; David Britt R Trapping a Cross-Linked Lysine-Tryptophan Radical in the Catalytic Cycle of the Radical SAM Enzyme SuiB. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2021, 118, No. e2101571118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Dong M; Kathiresan V; Fenwick MK; Torelli AT; Zhang Y; Caranto JD; Dzikovski B; Sharma A; Lancaster KM; Freed JH; Ealick SE; Hoffman BM; Lin H Organometallic and Radical Intermediates Reveal Mechanism of Diphthamide Biosynthesis. Science 2018, 359, 1247–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Donnan PH; Mansoorabadi SO Broken-Symmetry Density Functional Theory Analysis of the Ω Intermediate in Radical S-Adenosyl-L-Methionine Enzymes: Evidence for a Near-Attack Conformer over an Organometallic Species. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 3381–3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lundahl MN; Sarksian R; Yang H; Jodts RJ; Pagnier A; Smith DF; Mosquera MA; van der Donk WA; Hoffman BM; Broderick WE; Broderick JB Mechanism of Radical S-Adenosyl-l-Methionine Adenosylation: Radical Intermediates and the Catalytic Competence of the 5′-Deoxyadenosyl Radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2022, 144, 5087–5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Ye M; Thompson NB; Brown AC; Suess DLM A Synthetic Model of Enzymatic [Fe4S4]–Alkyl Intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141, 13330–13335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).McSkimming A; Sridharan A; Thompson NB; Müller P; Suess DLM An [Fe4S4]3+–Alkyl Cluster Stabilized by an Expanded Scorpionate Ligand. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 14314–14323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Brown AC; Suess DLM Reversible Formation of Alkyl Radicals at [Fe4S4] Clusters and Its Implications for Selectivity in Radical SAM Enzymes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 14240–14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Hagen KS; Holm RH Synthesis and Stereochemistry of Metal(II) Thiolates of the Types [M(SR)4]2−, [M2(SR)6]2−, and [M4(SR)10]2− (M = Fe(II), Co(II)). Inorg. Chem 1984, 2, 418–427. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Wang R; Camacho-Fernandez MA; Xu W; Zhang J; Li L Neutral and Reduced Roussin’s Red Salt Ester [Fe2(μ-RS)2(NO)4] (R = n-Pr, t-Bu, 6-Methyl-2-Pyridyl and 4,6-Dimethyl-2-Pyrimidyl): Synthesis, X-Ray Crystal Structures, Spectroscopic, Electrochemical and Density Functional Theoretical Investigations. Dalton Trans. 2009, No. 5, 777–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Zheng B; Chen X-D; Zheng S-L; Holm RH Selenium as a Structural Surrogate of Sulfur: Template-Assisted Assembly of Five Types of Tungsten–Iron–Sulfur/Selenium Clusters and the Structural Fate of Chalcogenide Reactants. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 6479–6490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Wiig JA; Hu Y; Lee CC; Ribbe MW Radical SAM-Dependent Carbon Insertion into the Nitrogenase M-Cluster. Science 2012, 337, 1672–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lanz ND; Pandelia M-E; Kakar ES; Lee K-H; Krebs C; Booker SJ Evidence for a Catalytically and Kinetically Competent Enzyme–Substrate Cross-Linked Intermediate in Catalysis by Lipoyl Synthase. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 4557–4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wiig JA; Hu Y; Ribbe MW Refining the Pathway of Carbide Insertion into the Nitrogenase M-Cluster. Nat. Commun 2015, 6, 8034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).McLaughlin MI; Lanz ND; Goldman PJ; Lee K-H; Booker SJ; Drennan CL Crystallographic Snapshots of Sulfur Insertion by Lipoyl Synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, 9446–9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).McCarthy EL; Booker SJ Destruction and Reformation of an Iron-Sulfur Cluster during Catalysis by Lipoyl Synthase. Science 2017, 358, 373–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhang B; Arcinas AJ; Radle MI; Silakov A; Booker SJ; Krebs C First Step in Catalysis of the Radical S-Adenosylmethionine Methylthiotransferase MiaB Yields an Intermediate with a [3Fe-4S]0-Like Auxiliary Cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 1911–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Esakova OA; Grove TL; Yennawar NH; Arcinas AJ; Wang B; Krebs C; Almo SC; Booker SJ Structural Basis for TRNA Methylthiolation by the Radical SAM Enzyme MiaB. Nature 2021, 597, 566–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Venkateswara Rao P; Holm RH Synthetic Analogues of the Active Sites of Iron-Sulfur Proteins. Chem. Rev 2004, 104, 527–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Hagen W Raymond. Biomolecular EPR Spectroscopy; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Boll M; Albracht SSP; Fuchs G Benzoyl-CoA Reductase (Dearomatizing), A Key Enzyme of Anaerobic Aromatic Metabolism. Eur. J. Biochem 1997, 244, 840–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Lindahl PA; Day EP; Kent TA; Orme-Johnson WH; Münck E Mössbauer, EPR, and Magnetization Studies of the Azotobacter Vinelandii Fe Protein. Evidence for a [4Fe-4S]1+ Cluster with Spin S = 3/2. J. Biol. Chem 1985, 260, 11160–11173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lindahl PA; Gorelick NJ; Münck E; Orme-Johnson WH EPR and Mössbauer Studies of Nucleotide-Bound Nitrogenase Iron Protein from Azotobacter Vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem 1987, 262, 14945–14953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Carney MJ; Papaefthymiou GC; Spartalian K; Frankel RB; Holm RH Ground Spin State Variability in [Fe4S4(SR)4]3−. Synthetic Analogs of the Reduced Clusters in Ferredoxins and Other Iron-Sulfur Proteins: Cases of Extreme Sensitivity of Electronic State and Structure to Extrinsic Factors. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1988, 110, 6084–6095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Zambrano IC; Kowal AT; Mortenson LE; Adams MW; Johnson MK Magnetic Circular Dichroism and Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Studies of Hydrogenases I and II from Clostridium Pasteurianum. J. Biol. Chem 1989, 264, 20974–20983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Conover RC; Kowal AT; Fu WG; Park JB; Aono S; Adams MW; Johnson MK Spectroscopic Characterization of the Novel Iron-Sulfur Cluster in Pyrococcus Furiosus Ferredoxin. J. Biol. Chem 1990, 265, 8533–8541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Flint DH; Emptage MH; Guest JR Fumarase A from Escherichia Coli: Purification and Characterization as an Iron-Sulfur Cluster Containing Enzyme. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 10331–10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Onate YA; Finnegan MG; Hales BJ; Johnson MK Variable Temperature Magnetic Circular Dichroism Studies of Reduced Nitrogenase Iron Proteins and [4Fe-4S]+ Synthetic Analog Clusters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Protein Struct. Molec. Enzym 1993, 1164, 113–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gloux J; Gloux P; Laugier J Single-Crystal and Powder EPR Studies of the S = 1/2 Ground State of the Iron−Sulfur Core in [Tris(Tetraethylammonium)][Tetrakis(Benzylthiolato)Tetrakis(μ3-Sulfido)Tetrairon]· (N,N-Dimethylformamide) with Crystal Structure Determination. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1996, 118, 11644–11653. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Helmut B; H. HR; Eckard M Iron-Sulfur Clusters: Nature’s Modular, Multipurpose Structures. Science 1997, 277, 653–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Noodleman Louis. Exchange Coupling and Resonance Delocalization in Reduced Iron-Sulfur [Fe4S4]+ and Iron-Selenium [Fe4Se4]+ Clusters. Part 1. Basic Theory of Spin-State Energies and EPR and Hyperfine Properties. Inorg. Chem 1991, 30, 246–256. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Moulis JM; Auric P; Gaillard J; Meyer J Unusual Features in EPR and Mossbauer Spectra of the 2[4Fe-4Se]+ Ferredoxin from Clostridium Pasteurianum. J. Biol. Chem 1984, 259, 11396–11402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gaillard J; Moulis JM; Auric P; Meyer J High-Multiplicity Spin States of 2[4Fe-4Se]+ Clostridial Ferredoxins. Biochemistry 1986, 25, 464–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Auric P; Gaillard J; Meyer J; Moulis JM Analysis of the High-Spin States of the 2[4Fe-4Se]+ Ferredoxin from Clostridium Pasteurianum by Mössbauer Spectroscopy. Biochem. J 1987, 242, 525–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Boll M; Fuchs G; Meier C; Trautwein A; Lowe DJ EPR and Mössbauer Studies of Benzoyl-CoA Reductase. J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 31857–31868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Lubner CE; Artz JH; Mulder DW; Oza A; Ward RJ; Williams SG; Jones AK; Peters JW; Smalyukh II; Bharadwaj VS; King PW A Site-Differentiated [4Fe–4S] Cluster Controls Electron Transfer Reactivity of Clostridium Acetobutylicum [FeFe]-Hydrogenase I. Chem. Sci 2022, 13, 4581–4588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Hagen WR; Wassink H; EADY RR; Smith BE; Haaker H Quantitative EPR of an S= 7/2 System in Thionine-Oxidized MoFe Proteins of Nitrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem 1987, 169, 457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Chakrabarti M; Deng L; Holm RH; Münck E; Bominaar EL Mössbauer, Electron Paramagnetic Resonance, and Theoretical Studies of a Carbene-Based All-Ferrous Fe4S4 Cluster: Electronic Origin and Structural Identification of the Unique Spectroscopic Site. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 2735–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Laskowski EJ; Frankel RB; Gillum WO; Papaefthymiou GC; Renaud J; Ibers JA; Holm RH Synthetic Analogs of the 4-Fe Active Sites of Reduced Ferredoxins. Electronic Properties of the Tetranuclear Trianions [Fe4S4(SR)4]3− and the Structure of [(C2H5)3(CH3)N]3[Fe4S4(SC6H5)4]. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1978, 100, 5322–5337. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Reynolds JG; Coyle CL; Holm RH Electron Exchange Kinetics of [Fe4S4(SR)4]2−/[Fe4S4(SR)4]3− and [Fe4Se4(SR)4]2−/[Fe4Se4(SR)4]3− Systems. Estimates of the Intrinsic Self-Exchange Rate Constant of 4-Fe Sites in Oxidized and Reduced Ferredoxins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 4350–4355. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Stephan DW; Papaefthymiou GC; Frankel RB; Holm RH Analogs of the [4Fe-4S]+ Sites of Reduced Ferredoxins: Structural and Spectroscopic Properties of [(C2H5)4N]3[Fe4S4(S-p-C6H4Br)4] in Crystalline and Solution Phases. Inorg. Chem 1983, 22, 1550–1557. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Hagen KS; Watson AD; Holm RH Analogs of the [Fe4S4]+ Sites of Reduced Ferredoxins: Single-Step Synthesis of the Clusters [Fe4S4(SR)4]3− and Examples of Compressed Tetragonal Core Structures. Inorg. Chem 1984, 23, 2984–2990. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lu T-T; Huang HW; Liaw WF Anionic Mixed Thiolate−Sulfide-Bridged Roussin’s Red Esters [(NO)2Fe(μ-SR)(μ-S)Fe(NO)2]− (R = Et, Me, Ph): A Key Intermediate for Transformation of Dinitrosyl Iron Complexes (DNICs) to [2Fe-2S] Clusters. Inorg. Chem 2009, 48, 9027–9035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Fitzpatrick J; Kalyvas H; Filipovic MR; Ivanović-Burmazović I; MacDonald JC; Shearer J; Kim E Transformation of a Mononitrosyl Iron Complex to a [2Fe-2S] Cluster by a Cysteine Analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2014, 136, 7229–7232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Lee Y; Jeon IR; Abboud KA; García-Serres R; Shearer J; Murray LJA [3Fe-3S]3+ Cluster with Exclusively μ-Sulfide Donors. Chem. Comm 2016, 52, 1174–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Arnet NA; McWilliams SF; DeRosha DE; Mercado BQ; Holland PL Synthesis and Mechanism of Formation of Hydride–Sulfide Complexes of Iron. Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 9185–9193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Li Q; Lalaoui N; Woods TJ; Rauchfuss TB; Arrigoni F; Zampella G Electron-Rich, Diiron Bis(Monothiolato) Carbonyls: C–S Bond Homolysis in a Mixed Valence Diiron Dithiolate. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 4409–4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Laviron E; Roullier L The Square Scheme with the Electrochemical Reactions at Equilibrium A Study by Diffusion or Thin Layer Cyclic Voltammetry and by Scanning Potential Coulometry. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interf. Electrochem 1985, 186, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- (53).Vallat A; Person M; Roullier L; Laviron E Electrochemical Study of Thermodynamics and Kinetics of the Cis-Trans Isomerization of Dicarbonylbis[1,2-Bis(Diphenylphosphino)Ethane]Molybdenum and -Tungsten Complexes and Their Cations. Inorg. Chem 1987, 26, 332–335. [Google Scholar]

- (54).Bernardo MM; Robandt P. v; Schroeder RR; Rorabacher DB Evidence for a Square Scheme Involving Conformational Intermediates in Electron-Transfer Reactions of Copper(II)/(I) Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1989, 111, 1224–1231. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Antanaitis BC; Moss TH Magnetic Studies of the Four-Iron High-Potential, Non-Heme Protein from Chromatium Vinosum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1975, 405, 262–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Beinert H; Thomson AJ Three-Iron Clusters in Iron-Sulfur Proteins. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1983, 222, 333–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Bertini I; Campos AP; Teixeira M; Luchinat C A Mössbauer Investigation of Oxidized Fe4S4 HiPIP II from Ectothiorohodospira Halophila. J. Inorg. Biochem 1993, 52, 227–234. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Cavazza C; Guigliarelli B; Bertrand P; Bruschi M Biochemical and EPR Characterization of a High Potential Iron-Sulfur Protein in Thiobacillus Ferrooxidans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 1995, 130, 193–199. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Heering HA; Bulsink YBM; Hagen WR; Meyer TE Reversible Super-Reduction of the Cubane [4Fe-4S](3+;2+;1+) in the High-Potential Iron-Sulfur Protein Under Non-Denaturing Conditions. Eur. J. Biochem 1995, 232, 811–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Tanifuji K; Yamada N; Tajima T; Sasamori T; Tokitoh N; Matsuo T; Tamao K; Ohki Y; Tatsumi K A Convenient Route to Synthetic Analogues of the Oxidized Form of High-Potential Iron–Sulfur Proteins. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 4000–4009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Miller JR; Busby RW; Jordan SW; Cheek J; Henshaw TF; Ashley GW; Broderick JB; Cronan John E; Marletta MA Escherichia Coli LipA Is a Lipoyl Synthase: In Vitro Biosynthesis of Lipoylated Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex from Octanoyl-Acyl Carrier Protein. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 15166–15178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Zhao X; Miller JR; Jiang Y; Marletta MA; Cronan JE Assembly of the Covalent Linkage between Lipoic Acid and Its Cognate Enzymes. Chem. Biol 2003, 10, 1293–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Cicchillo RM; Iwig DF; Jones AD; Nesbitt NM; Baleanu-Gogonea C; Souder MG; Tu L; Booker SJ Lipoyl Synthase Requires Two Equivalents of S-Adenosyl-l-Methionine To Synthesize One Equivalent of Lipoic Acid. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 6378–6386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Cicchillo RM; Booker SJ Mechanistic Investigations of Lipoic Acid Biosynthesis in Escherichia Coli: Both Sulfur Atoms in Lipoic Acid Are Contributed by the Same Lipoyl Synthase Polypeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 2860–2861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Douglas P; Kriek M; Bryant P; Roach PL Lipoyl Synthase Inserts Sulfur Atoms into an Octanoyl Substrate in a Stepwise Manner. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2006, 45, 5197–5199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Fajardo AS; Legrand P; Payá-Tormo L; Martin L; Pellicer Martínez MT; Echavarri-Erasun C; Vernède X; Rubio LM; Nicolet Y Structural Insights into the Mechanism of the Radical SAM Carbide Synthase NifB, a Key Nitrogenase Cofactor Maturating Enzyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142, 11006–11012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Burén S; Jiménez-Vicente E; Echavarri-Erasun C; Rubio LM Biosynthesis of Nitrogenase Cofactors. Chem. Rev 2020, 120, 4921–4968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.