Abstract

Background:

Despite the importance of social justice advocacy, surgeon attitudes toward individual involvement vary. We hypothesized that the majority of surgeons in this study, regardless of gender or training level, believe that surgeons should be involved in social justice movements.

Methods:

A survey was distributed to surgical faculty and trainees at three academic tertiary care centers. Participation was anonymous with 123 respondents. Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test were used for analysis with significance accepted when p < 0.05. Thematic analysis was performed on free responses.

Results:

The response rate was 46%. Compared to men, women were more likely to state that surgeons should be involved (86% vs 64%, p = 0.01) and were personally involved in social justice advocacy (86% vs 51%, p = 0.0002). Social justice issues reported as most important to surgeons differed significantly by gender (p = 0.008). Generated themes for why certain types of advocacy involvement were inappropriate were personal choices, professionalism and relationships.

Conclusions:

Social justice advocacy is important to most surgeons in this study, especially women. This emphasizes the need to incorporate advocacy into surgical practice.

Keywords: Advocacy, Social justice, Human rights, Surgeons, Opinion, Survey

1. Introduction

Acts of racism, gun violence and discrimination are prominent in today’s news and are frequent topics of discussion on social media outlets. Calls to action regarding social justice advocacy topics have been issued by an increasing numbers of medical societies which ask physicians to step beyond the realm of medicine and engage in social justice movements.1 One example is the American Medical Association who urged physicians to “advocate for the social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being”.1 While the idea of physician advocacy is not new, advances in technology and communication have allowed us to experience the breadth and devastation of violence and discrimination around the country.

Physician advocacy has been defined as “action by a physician to promote those social, economic, educational and political changes that ameliorate the suffering and threats to human health and well-being that he or she identifies through his or her professional work and expertise”.2 This definition implies that physician advocacy encompasses more than what is traditionally thought of as involving direct patient care, such as child and drug abuse. Instead, it enters the realm of social justice issues that historically were considered indirect impactors of patient care such as racism and immigration among others. Dr. Rudolf Virchow, of Virchow’s Triad, wrote in 1850 that, “… physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and social problems fall to a large extent within their jurisdiction”.2 Many surgeons are directly impacted by social justice problems such as racism, gun control, domestic violence, gender equality and more. We hypothesize that the majority of surgeons in this study, regardless of gender or training level, believe that surgeons and surgical societies should be involved in social justice movements.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design

We identified three academic tertiary care centers in three different geographic regions who were willing to participate in this pilot survey study. Topics were chosen based on three criteria. First, professional engagement of the surgeon in the social justice issue had to be considered anecdotally controversial to the pre-testing group. Discussion amongst group members included that physicians are generally expected to engage in advocacy when it encompasses a medical diagnosis or when we are mandated reporters. Examples include substance abuse prevention, given that it is a medically treated condition, and child abuse for which physicians are mandated reporters. As such, these were excluded. Second, it had to be associated with either a hashtag or an active, official internet website that defined the movement and its affiliations. Examples included “Black Lives Matter” for racism, “He For She” for gender equality, and “This is Our Lane” for gun control/gun rights. Third, we chose to limit the number of social justice issues discussed to no more than six in order to decrease the burden on the respondent. The final 6 social justice issues included were agreed upon by the pre-testing group prior to implementation. Demographic information was also asked of each participant in addition to the level of training and years in practice or residency. Advocacy related questions focused on two main categories: individual surgeon and surgical society involvement in social justice advocacy (Table 1, a complete survey can be found in the Appendix). Specifically, questions were asked regarding whether the respondent thought that these two groups should be involved, personal involvement in the past two years, type of involvement, social justice issues most important to that individual and types of advocacy that are inappropriate. Social justice advocacy issues included were racism, gender equality, gun control/gun rights, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer or questioning, plus (LGBTQ+) rights, immigration and sexual violence. The institutional review board (IRB) at the University of Oklahoma granted exemption approval to this study after an initial review (IRB 12593).

Table 1.

Non-demographic survey questions.

|

2.2. Pre-testing

The survey questions were emailed in word document form to a group of four surgical faculty (3 males and 1 female) and three residents (1 male, 2 females) for pre-testing at three academic tertiary care centers: Oklahoma University Medical Center in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma; Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania; and Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans, Louisiana. The survey is a convergent mixed methods design. In this pre-testing group, the surgical faculty were in different sub-specialties and years in practice while the surgical residents were from three different training years. The survey was also sent to an independent non-medical reviewer for syntax, grammar and readability. The questions asked to this pre-testing group were:

Any other questions/topics you feel are important or that surgeons would want to know?

Any questions that need clarity or revisions?

Any questions we should exclude and/or streamline?

All individuals responded to the email with their recommendations which were incorporated into a revised survey. Only after all individuals were satisfied with the clarity of questions and topics addressed was the survey then distributed to the three institutions. Participants who were involved in pre-testing were allowed to choose whether or not to anonymously participate in the formal survey once it was dispersed.

2.3. Distribution and participation

The final survey was composed into an online format within a secure REDCap database which was accessible via a unique link in which individuals could click to access the form and fill it out online. This link was embedded in an email with an invitation to participate in the study (see Appendix for the email invitation). The email was sent to the general surgery residency program directors at the three participating academic centers. The general surgery residency program directors then dispersed this email that contained the link to the survey form to all active general surgery residents, sub-specialty surgery fellows and surgical faculty at their institution. Respondents were able to click on the link in the email to access the REDCap survey form online to fill it out. Participants had the option to save their answers and complete the survey at a different time if desired. Once completed, all data was deidentified and stored in the REDCap database where the authors were able to access it for analysis. Participation was voluntary and anonymous. Information regarding consent, risks, benefits and alternatives was included at the top of each survey. Participants were informed that completion of the survey indicated consent. No incentives or deterrents were offered to participants. Respondents had one month to complete the survey once it was sent. A non-responder was defined as any surgical faculty or trainee who received the invitation email with embedded survey link but did not complete the survey within one-month after it was sent. Reminder emails were sent at the discretion of the individual institutions. Depending on the institution, 1–3 reminder emails were sent within the one-month time period after the survey was disseminated.

2.4. Statistical and qualitative analysis

In addition to descriptive statistics, statistical analysis was performed via Chi-square and Fisher’s exact test with significance assigned if p < 0.05. Qualitative, thematic analysis was performed on the free response text to questions 11 and 14 of the survey. Inductive, descriptive codes for each meaning unit were developed by reading through the responses by question and gender. Descriptive codes were then organized into patterns by question and gender. A code book was developed by revising all descriptive codes into hierarchical, more analytical codes. Patterns were organized into three themes: personal choices, professionalism and relationships. All free text responses were then imported into the qualitative data analysis computer software, NVivo. Gender was marked with different colored letters while questions focusing on individual surgeon or surgical society involvement in advocacy were separated by lower- and upper-case letters respectively. The code book was built within NVivo and the pattern and thematic codes were applied to the text. Text was pulled by codes and then reviewed and edited by patterns and themes within and across coded data segments before interpretation of the findings.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

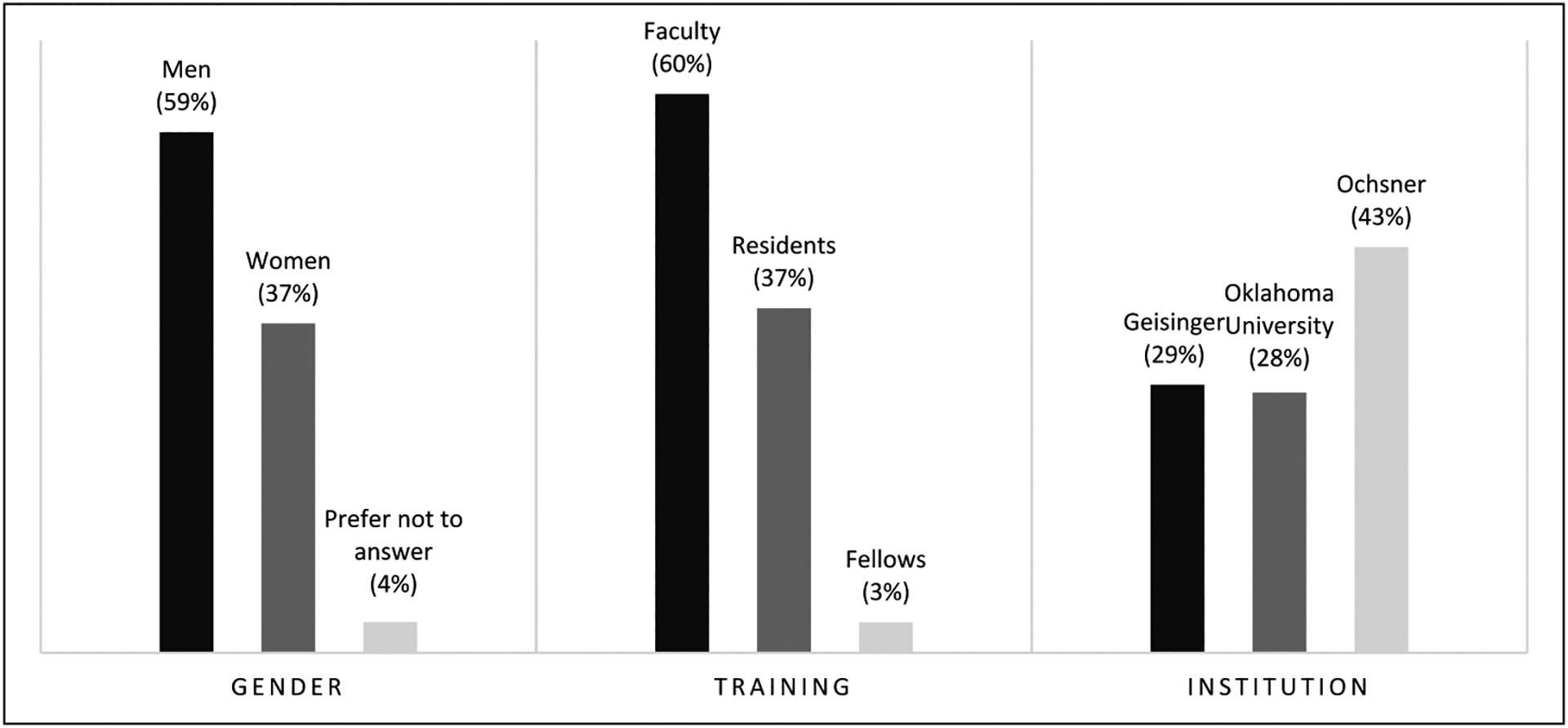

A total of 123 surgical faculty, fellows and residents completed the survey. The overall response rate was 46%. There was a higher response rate from faculty (50%) compared to residents (46%) and fellows (17%). The majority of respondents were white (77%), male (59%), surgical faculty (60%) and identified their specialty as general surgery (54%) (Table 2, Fig. 1). This was similar to the demographics of the overall surveyed population where 66% of those who received the survey invite were male and 58% were faculty. Other demographic information was not obtained from the non-respondent group and thus could not be compared. Responses were received from all major general surgery subspecialties (Table 3). Response differences between sub-specialties regarding individual and surgical society involvement in advocacy were analyzed and although slight variation existed, this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.81 and p = 0.34 respectively). Respondents ranged in age from 24 to 70 years old with an average of 39.6.

Table 2.

Demographics - race/ethnicity of respondents, n (%) n = 122.

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3 (2.5) |

| Asian | 12 (9.8) |

| Black or African American | 3 (2.5) |

| Hispanic, Latino or Spanish | 9 (7.4) |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) |

| White | 94 (77.0) |

| Other | 4 (3.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 4 (3.3) |

Fig. 1.

Demographics of respondents by gender, training level and institution.

Table 3.

Surgical sub-specialties of respondents, n (%) n = 115.

| Breast | 4 (3.5) |

| Cardiac | 6 (5.2) |

| Colon and Rectal | 6 (5.2) |

| General | 62 (53.9) |

| Pediatric | 9 (7.8) |

| Plastic | 2 (1.7) |

| Surgical Oncology | 6 (5.2) |

| Thoracic | 4 (3.5) |

| Trauma | 1513 |

| Vascula | 6 (5.2) |

3.2. Surgeon, surgical societies and advocacy

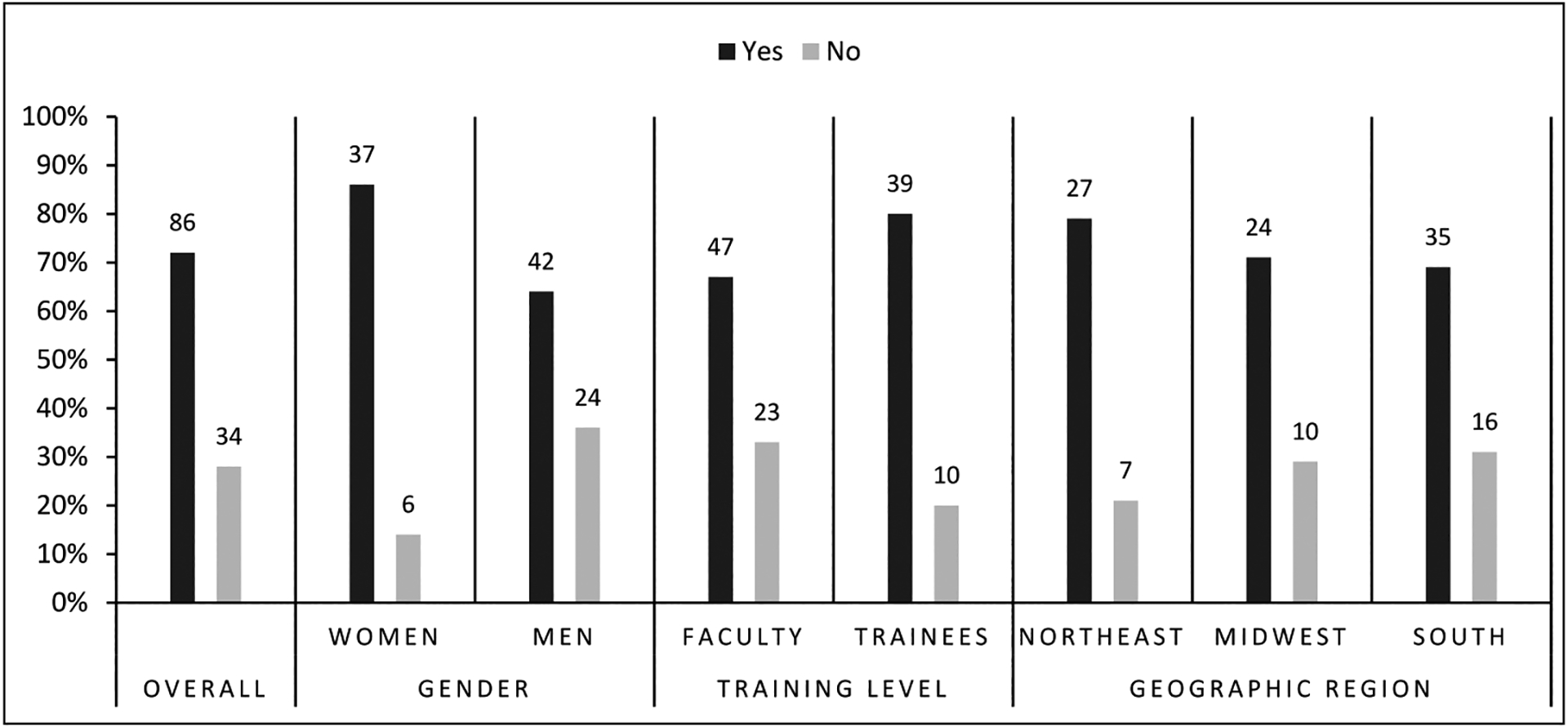

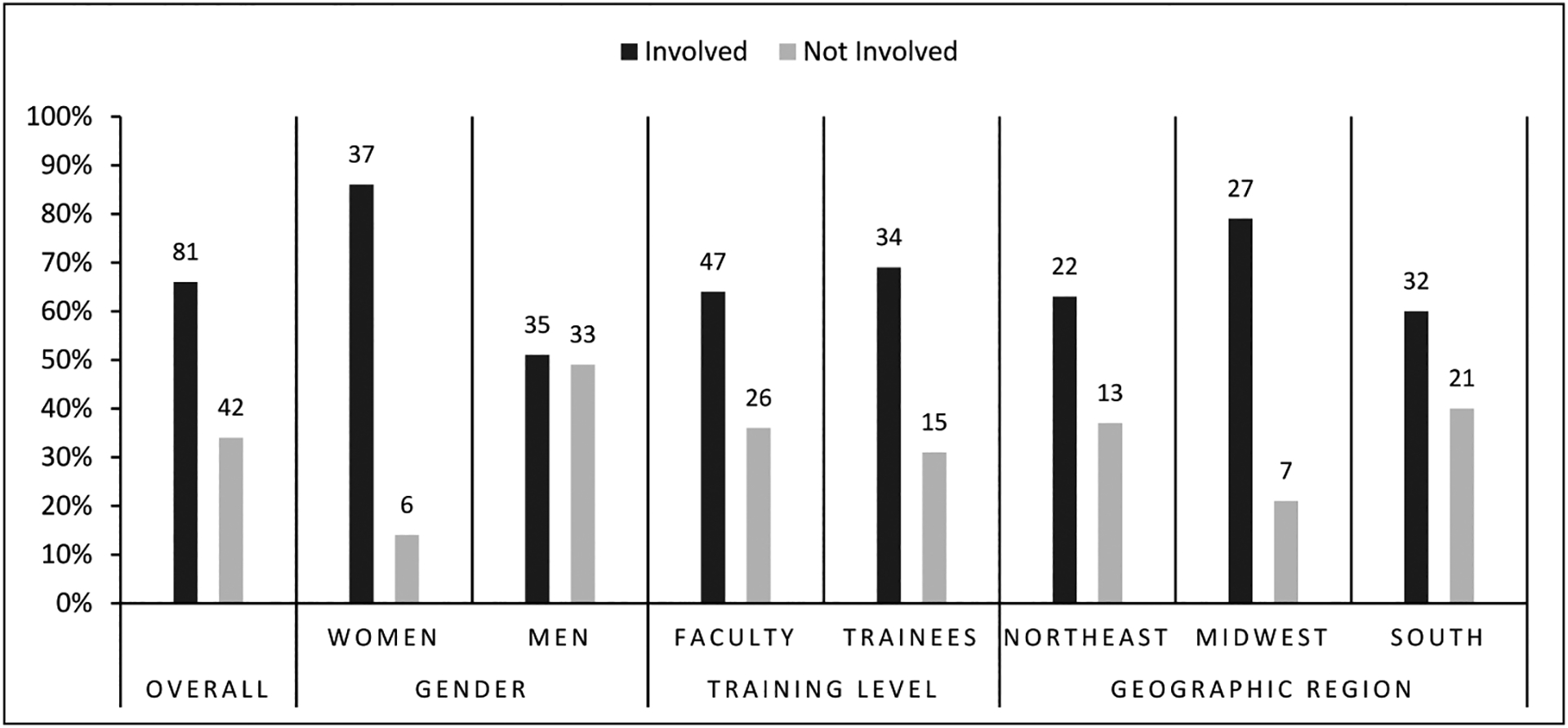

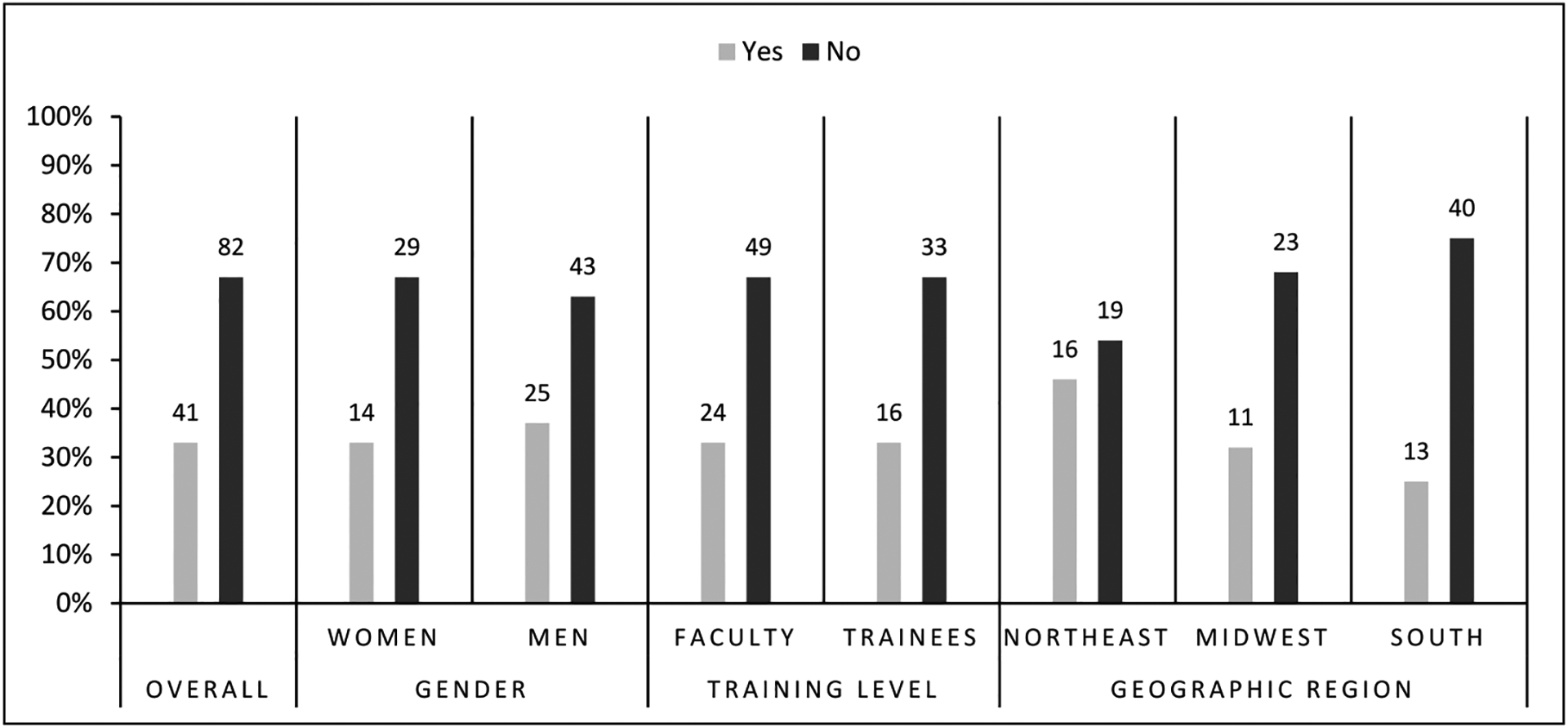

In general, 72% of participants stated that individual surgeons should be involved in social justice advocacy (Fig. 2). Most surgeons in this study stated that surgical societies should be involved in social justice advocacy (86%, Fig. 2). More than half of participants were involved in some form of social justice advocacy within the past two years and had some type of formal advocacy training (66% and 65% respectively, Fig. 3). The most common form of participation in social justice movements was discussing social justice movements at work (49%) followed by posting on social media (34%). When asked to choose the most important social justice issue, the majority of respondents selected racism (41%) followed by gender equality (15%) and gun control/gun rights (13%). Participants were also asked if they felt that there were any types of advocacy that were inappropriate for surgeons to be involved to which 33% of respondents selected “yes” (Fig. 4). The most common type of advocacy that was selected as being inappropriate for individual surgeon involvement was posting on social media (17.7%) followed by attending/organizing protests, marches or demonstrations (16%) and discussing social justice movements at work (16%).

Fig. 2.

Percentage of respondents in each group that selected “yes” or “no” when asked if individual surgeons should be involved in social justice advocacy.

Fig. 3.

Percent of respondents involved vs not involved in social justice advocacy within the last two years by gender, training level and geographic location.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of respondents in each group that selected “yes” or “no” when asked if there were any types of advocacy that were inappropriate for individual surgeons to be involved.

3.3. Gender and advocacy

Compared to men, women were significantly more likely to select that individual surgeons should be involved in social justice advocacy (86% vs 62%, p = 0.01, Fig. 2). There were no differences between genders regarding if surgical societies should be involved in advocacy (88% of women vs 79% of men, p = 0.30). Women were also more likely to be involved in advocacy in the last two years (86% vs 51%, p = 0.0002, Fig. 3). There was no difference between women and men regarding participation in advocacy training (67% vs 62%, p = 0.69). The percentage of men and women who indicated that certain forms of advocacy were inappropriate for individual surgeons to be involved were similar (33% of women and 37% of men, p = 0.69, Fig. 4). However, men were more likely to select that some forms of advocacy are inappropriate for surgical societies to be involved compared to women (49% vs 26%, p = 0.018).

Free text responses were also analyzed for variation between male and female respondents. In general, three main differences were noted between the genders. First, only men wrote about the potential of misinterpretation of their actions. Second, more women were concerned about the potential to harm relationships with colleagues compared to their male counterparts. Finally, more men than women wrote about the potential to harm relationships with patients.

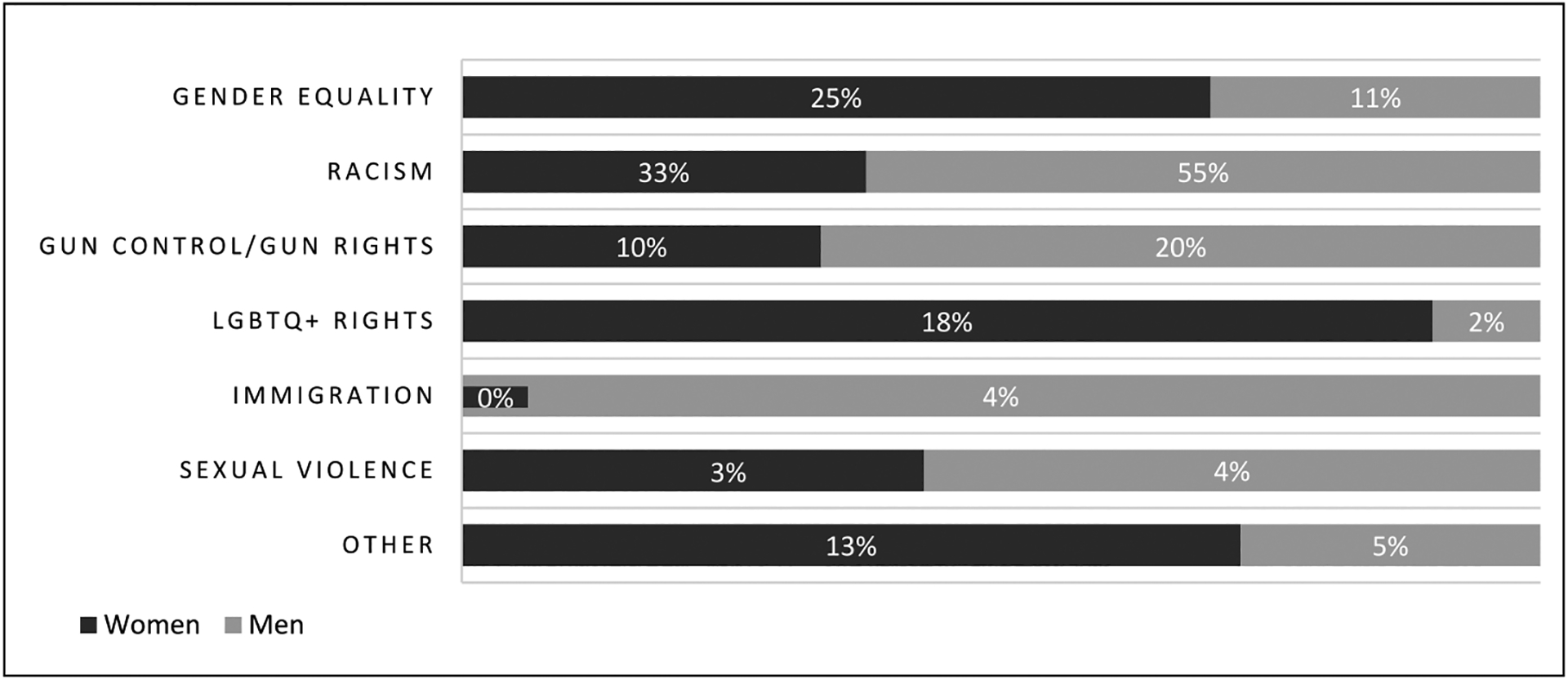

Significant variation also existed between men and women regarding what social justice issue was most important to them (p = 0.008). A higher percentage of women chose gender equality (24% vs 9%) and LGBTQ + rights (17% vs 2%) compared to men who were more likely to choose racism (47% vs 31%), gun control (17% vs 10%) and immigration (3% vs 0%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Percentage of most important social justice issue by gender.

3.4. Training level and advocacy

No significant differences were found between surgical faculty and trainees regarding individual surgeon involvement, surgical society involvement, personal involvement in advocacy, most important social justice issue or whether certain types of advocacy were inappropriate. However, a higher proportion of trainees indicated that individual surgeons (80% vs 67%) and surgical societies (86% vs 81%) should be involved in advocacy compared to faculty (p = 0.09 and 0.63 respectively, Fig. 2). A slightly higher percent of surgical faculty had participated in advocacy training compared to trainees, although this was not significant (67% vs 61%, p = 0.22). The type of training differed with a higher proportion of faculty participating in online training compared to trainees (59% vs 40%, p = 0.08). Faculty and trainees equally participated in social justice advocacy within the last two years (64% vs 69%, p = 0.70, Fig. 3). Faculty and trainees proportionally agreed that there are types of advocacy which are inappropriate for individual surgeons to be involved (33% each, p = 0.97, Fig. 4). There was no significant variation between faculty and trainees regarding the most important topic to them with the majority selecting racism (38% vs 46%, p = 0.55).

3.5. Geographic region and advocacy

Three geographic regions were included in this analysis: Northeast (represented by Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania), Midwest (represented by Oklahoma University Medical Center in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma) and South (represented by Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans, Louisiana). In general, there were no statistically significant differences between the three major geographic regions regarding surgeons and advocacy. However, respondents from the Northeast had the highest percentage of respondents selecting that individual surgeons should be involved in social justice advocacy followed by the Midwest and then the South (79%, 71% and 69% respectively, p = 0.61, Fig. 2). When asked if surgical societies should be involved in social justice advocacy, the South had the highest percentage to select “yes” followed by the Northeast and then the Midwest (87%, 86% and 74% respectively, p = 0.26). The Midwest had the highest percentage of advocacy participation in the last two years followed by the Northeast and the South (79%, 63% and 60%, p = 0.17, Fig. 3). Racism was selected as the most important social justice topic by all three regions. The South had the lowest percentage of respondents to select that certain types of social justice advocacy are inappropriate for individual and surgical society involvement (25% and 26%) compared to the Northeast which had the highest (46% and 51%) although this did not reach significance (p = 0.12 and 0.06 respectively) (Fig. 4).

3.6. Surgeon opinion on why certain types of advocacy are inappropriate

There were 30 respondents who indicated that certain types of advocacy are inappropriate for individual surgeons to be involved. All of these also responded in free text format to describe why they felt these types of advocacy were inappropriate. Thematic analysis led to several patterns that could be organized into three themes: personal choice, professionalism and relationships. These themes are outlined below.

3.6.1. Personal choice: being involved in social justice movements is a personal choice

Respondents thought that advocacy for social justice should be a personal choice that surgeons could make during their own time and outside of their work. These quotes illustrate this perception:

“I only think it is in a professional capacity. If it’s completely private that’s one thing but I don’t think all of it should be brought into the workplace or a professional capacity.”

“Being involved in social justice movements is a personal choice that any surgeon should be free to make.”

This perception of personal choice seemed to influence the position that professional organizations should not advocate for social justice movements, because they may not represent the diverse choices of individual members. The following quote is reflective of this position:

“An organization should not assume they have the same beliefs as all the people they represent.”

3.6.2. Professionalism: our responsibility is to take care of all patients

The notion of professionalism played an important role in considering social justice advocacy inappropriate for both surgeons and surgical organizations. Some respondents addressed the issue of a suitable environment when they stated that advocacy in the professional setting or workplace was not appropriate. Survey participants emphasized that patient care was their top responsibility. Surgeons thought that social justice advocacy was not appropriate when taking care of diverse patients with a wide variety of beliefs because they did not want discussions to affect their work or workflow. Instead, surgeons would rather focus on taking care of patients. Some respondents also addressed the role of organizations in the context of professionalism. Within this, some thought that organizations should support a movement prior to individual surgeons’ involvement. Another thought that organizations should collectively put forward an opinion. Talking about surgical societies, survey participants considered the financial support of social justice movements an improper use of finances because it was very likely that not all of the society’s members would support the chosen social justice cause.

3.6.3. Relationships: opinions Affect the way patients or colleagues think about us

The potential to damage professional relationships with patients, colleagues, and surgical societies also played an important role in considering social justice advocacy inappropriate for both surgeons and surgical organizations. As one person stated, “We … should not make our opinions affect the way patients or colleagues think about us. Social advocacy work might affect the way others think about us either because social justice messages/statements could be misinterpreted by the media, in the current social environment, or by social media posts taken out of context.”

Social justice advocacy work might also harm professional relationships at multiple levels. Several survey respondents thought that public statements, or discussions with patients, could offend or alienate patients, impair patient trust, and erode patient-doctor relationships. The following quotes illustrate these sentiments:

“Public prominence as a doctor/surgeon might alienate some patients and erode patient-doctor relationship which takes precedence …”

“… discussing advocacy and social justice unsolicited can sometimes offend patients who disagree with these views.”

Several respondents also pointed out that bringing social justice discussions into the work place would create an environment that colleagues might experience as unsafe, difficult, and uncomfortable. Two respondents spoke about the polarizing nature of such discussions, where “ … you are either with us or against us.”

In addition, social justice advocacy might negatively impact the professional society’s relationship to its members. Survey respondents perceived the role of surgical societies as caring for all of their members. They thought that societies could not, and should not, speak for or represent their members as a whole. By engaging in specific social justice advocacy, societies would likely alienate some of their members. Two quotes demonstrate these perceptions:

“I believe societies should stay out of such matters usually as it ends up feeling like they’re speaking for you and it may be something you don’t agree with.”

“Society membership is not homogeneous and such activity can alienate and split the membership.”

The three themes of personal choice, professionalism, and relationships were closely interwoven in the respondents’ perceptions of why social justice advocacy was inappropriate for surgeons and surgical societies. Social justice advocacy was considered a personal choice that, in general, was not compatible with the professional requirements of individual surgeons and surgical societies. The time and space for social justice advocacy was outside of work. Engaging in social justice causes in the professional space of caring for patients had the potential to distract from the focus of caring for patients, and to offend and alienate both patients and colleagues. Surgical societies also might run into the danger of alienating its members who, influenced by their perception of advocacy being a personal choice, did not want to be represented by the organization in support of specific social justice movements, in particular if financial support was involved.

4. Discussion

It was not until the last fifty years that there has been a rise in the emphasis on physicians playing an active role in advocacy. In particular, medical societies have begun to champion physicians as advocates for patients, healthcare reform and social justice movements.3 Physician advocates have historically been viewed on a broad spectrum, from benefactors of the disempowered to overanxious socialists. As an adaptation of what the Brazilian archbishop Dom Helder Camara wrote, “When I give treatment to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor are untreated, they call me a communist”.4 Our findings demonstrate that the majority of surgeons in this study agree with the need for their involvement in advocacy. However, there is a discrepancy between the percentage of surgeons stating that they should be involved in advocacy and those that have actually engaged in advocacy. This finding leads to the question of what barriers exist to preventing surgeons from being involved in advocacy.

Rising demands from surgical societies and their medical colleagues to take a stance on social justice issues can place pressure on the surgeon to become more involved in advocacy. However, today’s surgeons battle with the fear of litigation and concern for maintaining professionalism both within and outside of the clinical environment.5,6 This can lead to hesitancy in regard to being involved in advocacy in a professional capacity.7 These driving factors play a role in determining whether a surgeon is willing to become involved in advocacy.

Professional medical societies, as a whole, have increasingly been taking a stance on controversial social justice issues. Further emphasis has been placed on advocacy training in medical schools and being involved in professional societies that can affect changes in policy.8 The emphasis on physicians being involved in advocacy is ubiquitous across subspecialties. A Policy Statement issued by the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that, “… pediatricians have a role in advocating for policies and laws that protect youth who identify as transgender and gender diverse from discrimination and violence”.9 The American Medical Association published a policy titled, “Family and Intimate Partner Violence H-515.965” stating, “AMA believes that all forms of family and intimate partner violence (IPV) are major public health issues and urges the profession, both individually and collectively, to work with other interested parties to prevent such violence and to address the needs of survivors”.10 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued a “Joint Statement: Collective Action Regarding Racism” stating that, “… we will collectively advocate for public politics that seek to eliminate racial and other inequities”.11 The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has published defined statements on gender salary equality, diversity, harassment, discrimination and domestic violence. On July 21, 2020 the ACS even came out and issued not just a statement but a, “… call to action on racism as a public health crisis …”.12 Although 72% of surgeons in this study agree that they should be involved in advocacy, fewer respondents (66%) had actually participated in advocacy in the last two years. It is interesting to ask why surgeons are hesitant to engage in advocacy even when encouraged to do so by their professional organizations as well as by their medical colleagues. This reluctance appears to stem from three themes, specifically those of personal choice, relationships and professionalism. There is inferred fear that voicing one’s opinion on a specific social issue or use of professional standing as a lever of influence can be viewed as unprofessional behavior. A prominent example of this is physician presence in social media, where the line between professional and personal views is purposefully or inadvertently blurred.13 Respondents to our study indicated social media platforms, among other types of advocacy, as being inappropriate out of concerns for professionalism. The American College of Surgeons recognizes that social justice advocacy on media platforms is a vital and effective communication strategy. Rather than discourage surgeons from being involved in advocacy on social media, multiple guidelines have been published to direct the surgeon on how to maintain professional standards when utilizing such platforms for advocacy.6,13 Having identified potential barriers to advocacy involvement, how can the gap be closed between surgeons agreeing with advocacy involvement and personally engaging in advocacy?

One way to encourage involvement is to discuss the possible benefits of surgeon involvement in advocacy. An example is engaging in advocacy as a way to prevent and treat burnout; a topic that has recently received significant attention within the surgical community.14–16 A major symptom of burnout was the feeling of ineffectiveness when trying to deal with seemingly unchangeable, large, social constructs.14 Physicians, including surgeons, often care for patients who are victims of social inequities on a daily basis. From the surgical trauma victim of gun violence to the post-operative child struggling with recovery because of malnourishment, surgeons are not immune to the large social constructs that affect their patients.

Advocacy involvement can help the surgeon to feel empowered to decrease the burden of disease that they see. Uniting the surgical community on social advocacy topics that matter to surgeons and patients alike may remove the sense of helplessness, provide a voice and power to a specific issue, lead to a positive change in the community, and ultimately help the physician regain a sense of purpose in their profession.17,18 Joining with other specialties to combat social justice issues may also lead to faster systemic change as it is still true that, “many hands make light work”.

A second way to potentially increase surgeon involvement in advocacy is to better understand the views of those who feel that certain types of advocacy are inappropriate and then address those specific concerns. Ideas such as implementation of training regarding how to be involved in advocacy without negatively impacting the patient-physician relationship or how to engage in advocacy in a professional manner may help increase advocacy involvement. Although this pilot study points out key insights into the opinions of a small subset of surgeons in academic centers, it indicates the need for future studies targeting a broader surgeon population.

4.1. Limitations

This pilot study is limited by a small sample size, low response rate and represents only a minor subset of surgeons in three academic tertiary care centers. This has the potential to introduce bias as surgeons who are more likely to agree with surgeon advocacy and involvement may have also been more likely to complete this survey. There is also a paucity of literature specifically discussing surgeons and advocacy involvement. Further limitations include lack of demographic information of the non-responding population. Only gender and training level were able to be obtained in the non-responding population. Although these metrics are similar between the two populations, the lack of complete demographic information leads to an inability to generalize these findings. These results may also not be representative of surgeons throughout the United States since it only characterizes the opinions of surgeons from three academic centers in three geographic regions. Specifically, opinions of surgeons in community training programs, rural areas and from a wider variety of geographic regions are noticeably absent. Further studies incorporating more surgeons from a variety of practice settings as well as specifically addressing how to improve social justice advocacy involvement by surgeons and looking at surgeon advocacy training curriculum are needed. Finally, this study was disseminated by program directors which may have resulted in unintentional coercion, especially of surgical trainees. To decrease this risk, program directors received no notification of who responded to the survey and offered no incentives to either trainees or faculty for completion of the survey. However, it is possible that some trainees and faculty could have felt increased pressure to participate regardless. Finally, the verbiage “gun control/gun rights” are often thought of as contradictory terms. This may have led participants to be more or less likely to select this particular issue as appropriate for surgeon involvement.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study aims to identify the opinion of a subset of surgeons in academic training centers regarding social justice advocacy along with barriers to advocacy involvement. Based on the survey results, it can be concluded that the majority of surgeons in this study agree that they should be involved in social justice advocacy regardless of gender, training level or geographic region. However, the percent of surgeons that are actually involved in advocacy is notably smaller than those that agree that surgeons should be involved in advocacy. Sub-group analysis showed that overall more women surgeons agree that surgeons should be involved and have been involved in social justice advocacy within the last two years. These novel results lay the foundation for improving surgeon involvement in advocacy by identifying both the opinions of surgeons and potential groups that may benefit from further advocacy studies. Further studies are needed that look at the opinions of surgeons in a wider variety of practice settings including community training programs, rural areas and more geographic regions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank each of the general surgery program directors, Dr. George M. Fuhrman at Ochsner Medical Center, Dr. Jason S. Lees at Oklahoma University Medical Center and Dr. Mohsen M. Shabahang at Geisinger Medical Center for their support, proof-reading of the survey and instrumental help in encouraging faculty and trainee participation in this project. We would also like to thank the surgical faculty and trainees at each of the academic centers for their participation. In addition, we would like to thank Stephanie Mitchell for her contribution in converting the survey into an online format through REDCap.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.08.041.

References

- 1.Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):63–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhate TD, Loh LC. Building a generation of physician advocates: the case for including mandatory training in advocacy in Canadian medical school curricula. Acad Med. 2015. Dec;90(12):1602–1606. Epub 2015/07/23. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arya N Advocacy as medical responsibility. CMAJ (Can Med Assoc J). 2013. Oct 15; 185(15):1368. Epub 2013/10/02. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balch CM, Oreskovich MR, Dyrbye LN, et al. Personal consequences of malpractice lawsuits on American surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2011. Nov;213(5):657–667. Epub 2011/09/06. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Surgeons Statements on Principles. Bull Am Coll Surg p. 19–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huddle TS. Perspective: medical professionalism and medical education should not involve commitments to political advocacy. Acad Med. 2011. Mar;86(3):378–383. Epub 2011/01/21. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallagher S, Little M. Doctors on values and advocacy: a qualitative and evaluative study. Health Care Anal. 2017. Dec;25(4):370–385. Epub 2016/05/12. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rafferty J, Child COPAO, Health F, et al. Ensuring comprehensive care and support for transgender and gender-diverse children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142 (4), e20182162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Association TAM. Family and intimate partner violence H-515.965. Available from: https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/Violence%20and%20Abuse?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-4664.xml; 2019.

- 11.TACoOa Gynecologists. Joint statement: collective action regarding racism. Available from https://www.acog.org/news/news-articles/2020/08/joint-statement-obstetrics-and-gynecology-collective-action-addressing-racism; 2020.

- 12.ACoSBoRaACoSCo Ethics. American College of surgeons call to action on racism as a public health crisis: an ethical imperative. Available from https://www.facs.org/about-acs/responses/racism-as-a-public-health-crisis; 2020.

- 13.Logghe HJ, Boeck MA, Gusani NJ, et al. Best practices for surgeons’ social media use: statement of the resident and associate society of the American College of surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(3):317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Balch CM, Freischlag JA, Shanafelt TD. Stress and burnout among surgeons: understanding and managing the syndrome and avoiding the adverse consequences. Arch Surg. 2009;144(4):371–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dimou FM, Eckelbarger D, Riall TS. Surgeon burnout: a systematic review. J Am Coll Surg. 2016. Jun;222(6):1230–1239. Epub 2016/04/24. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horwitch C Reducing physician burnout starts with increasing advocacy. Med Econ. 2018;95(18):1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeelani R, Lieberman D, Chen SH. Is patient Advocacy the solution to physician burnout? Semin Reprod Med. 2019. Sep;37(5–06):246–250. Epub 2020/07/11. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stull MJ, Brockman JA, Wiley EA. The “I want to help people” dilemma: how advocacy training can improve health. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.