ABSTRACT

Temporary foreign farm workers (TFWs) are among the most vulnerable and exploitable groups. Recent research shows alarming rates of food insecurity among them. This review explores research focussing on food security of TFWs in Canada and the United States, summarizes findings, and identifies research gaps. Online databases, including MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, and government and nongovernment websites, and websites of migrant worker–supporting organizations were searched for peer-reviewed and non–peer-reviewed papers and reports published between 1966 and 2020 regarding food security of TFWs. Articles reviewed were analyzed to determine publication type, country, year, target population, and main findings. Content analysis was performed to identify major themes. Of 291 sources identified, 11 met the inclusion criteria. Most articles (n = 10) were based on studies conducted in the United States. The prevalence of food insecurity among TFWs ranged between 28% and 87%. From the content analysis, we formulated 9 themes, representing a diversity of perspectives, including access to resources, income, housing and related facilities, food access, dietary pattern and healthy food choices, and migrant's legal status. Instruments reported for the measurement of food security include USDA Household Food Security Survey Module (HFSSM; n = 8, 72.7%), the modified version of the USDA HFSSM (n = 1, 9%), hunger measure (n = 1, 9%), the modified CDC's NHANES (n = 1, 9%), and 24-h recall, diet history, and/or food-frequency questionnaire (n = 3, 27.3%). Factors impacting food security of TFWs working under the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Programs (SAWPs) in North America are understudied. There is a need to advance research looking particularly at policies and regulatory and administrative aspects of the SAWPs to improve the food security of this cohort. There is also a need for qualitative studies that explore lived experiences and perspectives of TFWs and key informants. Longitudinal studies may be useful to examine various factors, including policy-related, contributing to food insecurity of TFWs over time.

Keywords: food security, temporary foreign workers, seasonal agricultural worker program, migrant farm workers, Canada, United States

Statement of Significance: In light of the COVID-19 emergency situation and the ongoing restrictive measures towards containing the spread of the infection, the health and food security of the already vulnerable temporary foreign farm workers become even more compromised since they provide essential services within exceptionally challenging work and living conditions. Recent reports and media news indicate severe illness and death outbreaks among migrant workers, especially on farms and food-processing facilities due to work-related exposure. There is an immediate need to address these workers’ vulnerability to food security. This scoping review contributes to the efforts towards advancing our knowledge and understanding of a largely understudied and complex phenomenon of food security of temporary foreign farm workers within the context of an exceptionally challenging precarious status in which they live and work, in order to underline knowledge gaps and suggest further research focus and policy change recommendations.

Introduction

Canada and the United States have longstanding temporary foreign worker programs (TFWPs), which attract hundreds of thousands of temporary foreign farm workers (TFWs) every year to perform agricultural labor. Both countries depend largely on TFWs to fill labor shortages in agriculture, including temporary/seasonal positions, contributing to the food security of Canadian and US populations (1). These programs are characterized by seasonality and uncertainty of labor demand (2), unfree and limited contract (3), dependency, low wage and unstable income, poor housing conditions, laborious jobs and long working hours, isolation in rural “food deserts,” restricted mobility, limited access to social and human programs and services, and occupational and health risks (4–6). The culture of migrant farm work, together with the policy-related construct, nature, and administration aspects of the TFWPs, provides a precarious work and living environment and lifestyle over which TFWs have no control (5). The link between such blend of marginalizing conditions and the increased likelihood of TFWs’ vulnerability to and sustainability of food insecurity is well documented in the literature (5).

Temporary foreign worker programs

For many years, TFWs have been brought to Canada and the United States to perform agricultural labor through their respective TFWPs under the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) in Canada and the US Temporary Agricultural Workers Program (H-2A visa program) in the United States (7).

Canada relies on temporary or seasonal agricultural workers to sustain its economy (8, 9). The TFWP originated with the SAWP in 1966 as a pilot program to respond to agricultural labor shortages in Ontario and British Columbia (10), and continues to respond to short-term labor shortages in the Canadian economy (8, 9).

Foreign migrant workers play a major role in filling the labor gap in the Canadian agricultural sector, where Canadian citizens are not available or interested in this type of work (11). TFWs occupy up to 75% of agricultural positions (12). The number of TFWs working in agricultural positions increased by 52% between 2015 and 2019, reaching approximately 64,000 workers. The need for TFWs in the agricultural sector is expected to be 113,800 positions in 2025 (11).

Over the years, the Canadian TFWP has gone through a series of reforms, the most recent occurring in June 2014, when it was re-organized into 2 distinct programs: the temporary foreign worker program (TFWP) and the international mobility program, each with different requirements and operating procedures (10, 13, 14). Under this new reform, and at the request of the employer and following verification and approval from Employment and Social Development Canada, TFWs are admitted in Canada to fill temporary jobs through various temporary labor migration streams (10, 15). These streams are as follows:

High-wage stream, which refers to positions for which the wage offered to the hired TFWs is at or above the provincial/territorial median wage. This stream includes occupations such as managerial, scientific, professional, and technical.

Low-wage stream, which refers to positions where the wage offered to the hired TFW is below the provincial/territorial median wage. General laborers, food counter attendants, and sales and service personnel are examples of such positions, which usually require lower levels of formal training, such as a high school diploma or a maximum of 2 y of job-specific training.

Primary agricultural stream, under which TFWs from any country are admitted and hired to fill positions related to on-farm primary agriculture. This stream provides 4 options for employers wishing to hire TFWs for agricultural positions: 1) the SAWP, which enables employers to hire TFWs exclusively from Mexico and a number of Caribbean countries to work in seasonal agricultural positions; 2) the agricultural stream; 3) the high-wage stream; 4) and the low-wage stream (16). Each option has different rules concerning where the foreign workers can come from, the types of farms they can work on, and the type of work they can do.

In the United States, foreign agricultural workers are admitted through the foreign temporary/seasonal agricultural worker program, known as the H-2A visa program, which emerged as a result of the reform of the H-2 visa program in 1986 under the Immigration Reform and Control Act (7, 17). The H-2A program is an uncapped category that is managed and administered by 3 federal agencies (7): the Employment and Training Administration of the Department of Labor, which issues the H-2A labor certifications and oversees compliance with labor laws; US Citizenship and Immigration Services of the Department of Homeland Security, which adjudicates the H-2A visa petitions; and the Department of State, which issues the visas to the workers at consulates overseas (7, 17).

The process of obtaining foreign temporary/seasonal agricultural workers under the H-2A program is similar to that followed under the SAWP and several agencies must approve the employer's petition before employment can commence (17). Employers wishing to hire foreign temporary agricultural workers must demonstrate there are insufficient domestic workers who are “able, willing, qualified, and available to do the temporary work,” and certify that the proposed wages and employment conditions for the potential H-2A workers satisfy the applicable state employment standards and will not affect the wages and working conditions for American agricultural workers performing similar labor (18). However, unlike Canada, many foreign workers in the United States are unauthorized, with almost 50% of the agricultural workforce holding this status (17). In 2020, a total of 275,000 H-2A visas were issued for TFWs (19), comprising about 10% of the crop farmworkers hired in the United States (20).

Both the Canadian SAWP and the US H-2A visa program are agriculture-specific programs designed to hire foreign workers to fill positions of a temporary/seasonal nature for a specific period of time (21, 22). We have chosen Canada and the United States for the review for a number of reasons: 1) both countries depend largely on TFWs to fill labor shortages in agriculture, including temporary/seasonal positions (8, 9, 23); 2) both countries have similar longstanding TFWPs, although administered differently (24), which attract hundreds of thousands of TFWs every year; 3) agriculture in both countries comprises the largest sector compared with all other sectors in the TFWP (23, 25); 4) the TFWPs in both countries have received much attention and criticism, particularly towards violations to TFWs’ collective bargaining rights and protection capacities, among other issues (7); 5) the TFWPs in both countries continue to expand progressively, even after many reforms over the years (7, 13, 14, 10, 26); 6) except for the agricultural stream, all positions for TFWs demonstrated a downward trend after the major reform of the Canadian TFWP in 2014 (26); and 7) the Canadian SAWP has internationally been viewed as a model of best practices for managed migration, a model that inspired other countries, including the United States to develop their own migration programs (27). Table 1 provides a comparison between the US and Canadian TFWPs.

TABLE 1.

Comparison between the US and Canadian temporary foreign worker programs1

| Canada | United States | |

|---|---|---|

| Streams/programs | Low-wage, high-wage, primary agriculture, live-in caregiver program, and global talent stream | The H-1B, H-2A (agriculture), H-2B (nonagriculture), H-4 are the largest among the TFWPs; other programs exist |

| Regulation | Federal Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, and Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations | Immigration and Nationality Act |

| Administration | Federal (IRCC, ESDC, and CBSA) and provincial governments | Federal government (DOL, BCIS, DOS, DHS) |

| Labor certification | ESDC | DOL |

| Permit/visa duration | 8 mo | Up to 1 y (may be extended for “qualifying employment” in increments of <1 y, up to a maximum stay of 3 y) |

| Qualified TFWs | Nationals from all countries (some programs under the Primary Agriculture, such as the SAWP, are exclusive to nationals from Mexico and Caribbean countries) | All nationalities |

| Legal status of TFWs | TFWs are largely authorized (i.e., documented) | TFWs are largely unauthorized (undocumented) |

| Hiring process | Employer-driven (for low-skilled and agricultural workers); sending country selects workers to be sent | Employer-driven (for low-skilled and agricultural workers); sending country selects workers to be sent |

| Employer must advertise for the position for a defined period of time and demonstrate that no domestic workers are available for the job | Employer must advertise for the position for a defined period of time and demonstrate that no domestic workers are available for the job | |

| Employer must file and pass a labor market impact assessment and acquire a positive labor market certification | Employer must file and pass a labor market impact assessment and acquire a positive labor market certification | |

| Requires approval from several agencies (e.g., ESDC) | Requires approval from several agencies (e.g., DOL) | |

| Requires work permit (usually restricted to 1 employer) | Requires work permit (usually restricted to 1 employer) | |

| Employer must first advertise the job for a defined period of time at a predetermined wage to prove no native workers are available | Employer must first advertise the job for a defined period of time at a predetermined wage to prove no native workers are available | |

| Annual cap of TFWs | Restricted since 2014 | H-2A Unrestricted; H-2B Restricted |

| The number of TFWs exceeds that of permanent immigrants | Relatively low ratio of TFWs to permanent immigrants |

BCIS, Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services; CBSA, Canada Border Services Agency; DHS, Department of Homeland Security; DOL, Department of Labor; DOS, Department of State; ESDC, Employment and Social Development Canada; IRCC, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; SAWP, Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program; TFW, temporary foreign worker.

The SAWP

The SAWP is one of the oldest agriculture-related TFWPs that is commonly used by agricultural producers (15). The SAWP is based on bilateral agreements (8, 28, 29) between the government of Canada and the governments of Mexico and 11 Commonwealth Caribbean countries (10, 30). Under the SAWP, Canadian employers hire TFWs exclusively from these countries to meet their temporary, seasonal agricultural labor needs (11) for a maximum of 8 mo (22, 31).

Currently, more than 46,000 workers from Mexico and Caribbean countries are working in 10 Canadian provinces under the SAWP (32–34). In 2019, Ontario received the most workers (40,759 workers), followed by Quebec (33,730 workers) and British Columbia (32,020 workers) (8, 32, 35), while Mexico supplied the most workers (31, 36).

Many reports have appraised the SAWP as “a model program” characterized by best practices for managed migration that benefit the Canadian economy, consumers, and farmers (27, 33, 36, 37), as well as TFWs and their families (37). In 2017, the SAWP contributed significantly to the agricultural industry related to fruit and vegetable farms ($5.4 billion) and greenhouses ($1.4 billion) (38). The Canadian agricultural sector experiences fluctuating employment needs due to Canada's climate (2, 11). At its seasonal peak, the sector employs up to 30% more workers than at low times. Therefore, farmers may view the SAWP as a vital response to meet fluctuating labor needs. For migrant workers, the SAWP provides legal entry into Canada to work in 10 provinces so that they can support their families (29).

Food security is a multifaceted phenomenon (39). The United Nations FAO recognizes that “food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food to meet their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life” (40). The term “household food security” follows the definition of food security but at the family (household) level, focusing on household members (41). A household is considered food secure when it has access to sufficient food (in quality, quantity, and safety and culturally acceptable) for a healthy life to all individuals in the household (42).

There is substantial literature that has examined how TFWPs impact the lives and livelihoods of TFWs, making them racialized, marginalized, vulnerable, and exploitable due to their precarious and temporary status. Vulnerability to food insecurity is closely related to the different social patterns among the different sectors of the community (43). The FAO defines vulnerability as the “full range of factors that place people at risk of becoming food insecure” (41). This definition bases vulnerability on 3 dimensions: 1) vulnerability to an outcome; 2) vulnerability from a variety of risk factors, including political structures and processes which perpetuate inequity (44); and 3) vulnerability because of an inability to manage those risk factors (44, 45). However, less literature has focused on their food security and aspects of the Canadian SAWP and US H-2A programs that shape it. Previous reports indicated that TFWs, particularly those working and living in rural areas, have been reported to experience high levels of food insecurity, ranging from 20% to 80% (5, 6, 46). Food insecurity among TFWs might, in part, be due to their limited access to healthy and affordable food options subject to availability and transportation (46). In addition, farm workers have restricted access to food safety-net and health programs that provide support for nutritious and healthy food, due mainly to a lack of information and understanding regarding eligibility for these programs, which further complicates their risk to food insecurity (4, 46).

The purpose of this scoping review is to summarize current knowledge about food security of TFWs hired under the SAWP stream in Canada and the H-2A visa program in the United States, describe relevant research trends, and identify potential knowledge gaps, with a view to advancing research priority areas and answering unresolved questions.

The objectives of the review are as follows: 1) to describe the status of food security of TFWs in Canada and the United States; 2) to examine the extent research has addressed food security of TFWs and how well all subgroups (e.g., documented vs. undocumented; lone migrants vs. migrants with their families; women and children; seasonal vs. year-round) and geographic areas (e.g., TFWs working in rural areas vs. those working in urban or suburban areas) are represented; and 3) to summarize findings regarding the scope (i.e., extent, range, focus, and nature) (47) of research activity addressing food security of TFWs, determine current knowledge, and identify research gaps.

Methods

Review of the literature

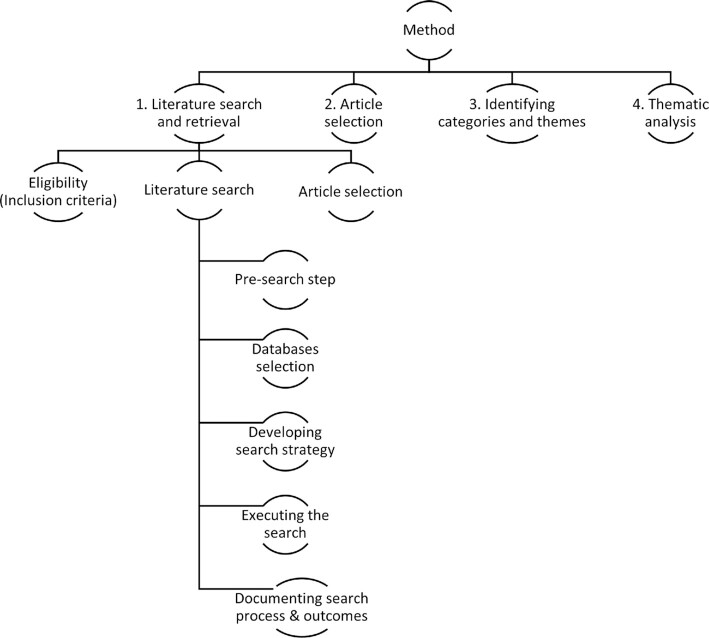

This scoping review followed the methodological framework of literature review outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (48) and the recommendations proposed by Levac and colleagues (47) to further advance the methodology based on Arksey and O'Malley's framework. The review is also informed by the reporting guidance set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses–Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) methodology for best practices in the reporting of scoping reviews (49). The review process involved the following stages: 1) search and retrieval of the literature, 2) selection of articles for the review, 3) identification of categories and themes within categories, and 4) thematic analysis (47, 50). A flowchart summarizing the review methodology is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

A schema outlining the review methodology.

A team of 2 reviewers were involved in the discussions and decision making surrounding the scoping process, and an associate research librarian at University of Saskatchewan helped develop and refine the search strategy (47).

Literature search and retrieval strategy

Peer-reviewed and non–peer-reviewed literature were searched through electronic databases, gray literature, reference lists, and hand-searching of key journals (51) using the following steps: 1) pre-search, 2) identifying and selecting relevant databases and other literature sources, 3) developing a search strategy for each database using key terms, and 4) documenting the search process and outcomes.

Pre-search step

One of the challenges we anticipated during the initial search was identifying relevant terminology that best describes “seasonal agricultural workers” and associated hiring programs under which those workers are admitted to the host country. Although using broad terminology and wide definitions may reduce the likelihood of missing relevant sources (48), and ensure a comprehensive and thorough review of available literature, this approach may produce a large volume of unmanageable and/or irrelevant articles. In addition, failure to capture the specific terminology and definitions used in Canadian and US contexts may risk missing relevant articles that contain important information. To increase the chance of identifying relevant articles in the electronic databases and to ensure consistency in the search strategy, we used a pre-search step to compile lists of terminologies and keywords constructed independently by each reviewer through hand-searching subject-specific articles published in key journals.

The pre-search was used for the following reasons:

As a means of a preliminary exploration of existing literature to capture and get to know context-specific terminology/keywords commonly used to apply them in the actual search. This step enhanced our familiarity with the literature and assisted in compiling and expanding a list of relevant key terms to conduct a more comprehensive, relevant search.

To avoid returning a large number of hits that would likely be unmanageable/irrelevant in the actual search.

Database selection

Since the topic under review includes concepts from both the fields of health sciences and social sciences, research databases from both disciplines were searched for relevant articles to ensure a comprehensive reach. The primary databases searched were MEDLINE (from 1966 to 26 December 2020), Web of Science (from 1966 to 26 December 2020), and Scopus (from 1966 to 26 December 2020). These databases were purposefully selected because they offer comprehensive coverage of the most up-to-date information from reliable, high-quality publications (50, 52). Accessing multiple databases is considered best practice to support a comprehensive search and to minimize potential bias (52, 53). Other databases, such as Google Scholar, SAWP-related government and nongovernment websites, and websites of migrant workers support and advocacy organizations were also searched. (A list of organizations supporting migrant workers can be found at: https://www.migrantworker.ca/for-migrant-workers/organizations/.) The reference lists of the retrieved articles that met the inclusion criteria were also searched.

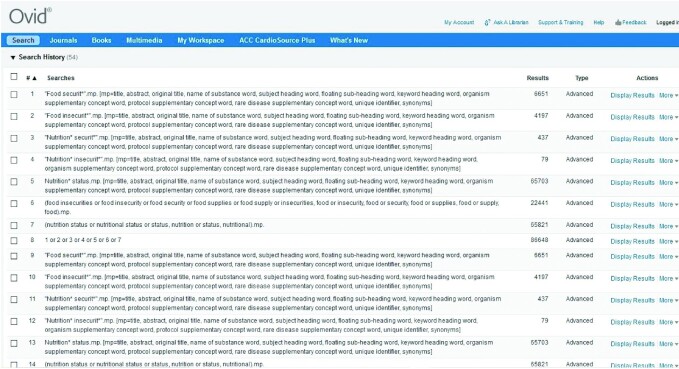

The literature search strategy

A combination of “keyword” mapped to database-suggested “subject term” [e.g., Medical Subject Heading (MeSH)] searching was used in each database to maximize relevance and retrieval of journal articles. A list of keywords and corresponding MeSH terms searched in the title, abstract, and keyword sections of the publications is summarized in Table 2. Where required, quotes (“ ”) were used to search for an exact phrase, and an asterisk (*) operator (or wildcard) was attached to the keyword to broaden the search. A Boolean search using Boolean operators was applied to combine keywords to further limit the search and produce more relevant results (50). Within MEDLINE/PubMed each search concept (e.g., “food security,” “seasonal agricultural worker program,” “Canada,” etc.) was expanded by connecting keywords with associated MeSH terms using appropriate Boolean operators. Limits were applied to identify full-text articles with the abstract written in the English language and a search date between 1966 (the year the SAWP was created) and 2020. No restrictions on publication type or geographic location were applied. The same search strategy was adapted for the other databases using the same keywords, MeSH terms (where applicable), and search limitations. Google-based search engines (Google and Google Scholar) and gray literature were searched to locate relevant non–peer-reviewed and/or unpublished articles/documents. Figure 2 presents a flowchart of the literature search and selection process.

TABLE 2.

Search terms and corresponding Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) used in MEDLINE/PubMed for literature review1

| Search concept | Keyword | MeSH term |

|---|---|---|

| Food security | “food securit*” | Food security |

| “food insecurit*” | Security, food | |

| “nutrition* securit*” | Food insecurity | |

| “nutrition* insecurit*” | Food insecurities | |

| “nutrition* status” | Insecurity, food | |

| Insecurities, food | ||

| Nutrition status | ||

| Nutritional status | ||

| Status, nutrition | ||

| Status, nutritional | ||

| TFWP/SAWP | “seasonal agricultural worker program” | Emigration and immigration |

| “temporary foreign worker program” | Transients and migrants | |

| “SAWP” | Agriculture | |

| “agricultural stream” | Farming | |

| “primary agriculture” | Transients and migrants | |

| “labour migration” or “Labor migration” | ||

| TFW | “temporary foreign agricultural worker*” | Migrants |

| “temporary migrant agricultural worker*” | Migrant worker | |

| “temporary migrant farm worker*” | Migrant workers | |

| “temporary foreign worker*” | Worker, migrant | |

| “temporary migrant worker*” | Workers, migrant | |

| “temporary agricultural worker*” | Migration policy | |

| “temporary foreign farm worker*” | Policy, migration | |

| “Seasonal agricultural worker*” | Migration policies | |

| “seasonal agricultural labour*” | Policies, migration | |

| “seasonal agricultural labour*” | Farmers | |

| “labor migrant*” or “Labour migrant*” | ||

| “migrant farm worker*” | ||

| “migrant worker*” | ||

| “Mexican migrant*” | ||

| “Jamaican migrant*” |

Searched on 26 December 2020. SAWP, seasonal agricultural worker program; TFW, temporary foreign farm worker; TFWP, temporary foreign worker program.

FIGURE 2.

A fraction of sample literature search results conducted in MEDLINE using keywords, subject terms, and Boolean operators. Copyright 2020 by Ovid Technologies, Inc.

Documenting the search process and outcomes

The search process, the resulting search log, and retrieved journal article lists generated in each electronic database were saved in a specific folder created in a personal account in the searched database to facilitate management, review, and modification of the original search, if needed (51). The retrieved article lists were then exported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation) with the following categories: search date, name of database searched, article title, abstract, author(s) name(s), publication year, source (publication journal), and keywords (54). At this stage, the exported citations were subject to screening for relevance, eligibility, and duplicates (55).

Eligibility: inclusion/exclusion criteria

To mitigate possible bias, 2 independent reviewers were involved in defining the study inclusion and exclusion criteria as well as the search terms at the outset of the study to minimize the potential for later ambiguity and disagreement in article selection when screening articles (48, 56). For example, while studies examining migrant agricultural workers are available in the literature, some of these studies focused on documented migrant workers while others addressed nondocumented migrant workers. Each migrant worker class (i.e., documented vs. nondocumented, seasonal vs. migrant) has its own challenges, legal considerations, eligibility for social assistance, and living and work conditions (35, 46), which may impact their risk and vulnerability to food insecurity. Therefore, we sought to specifically describe the target population to be included in our review.

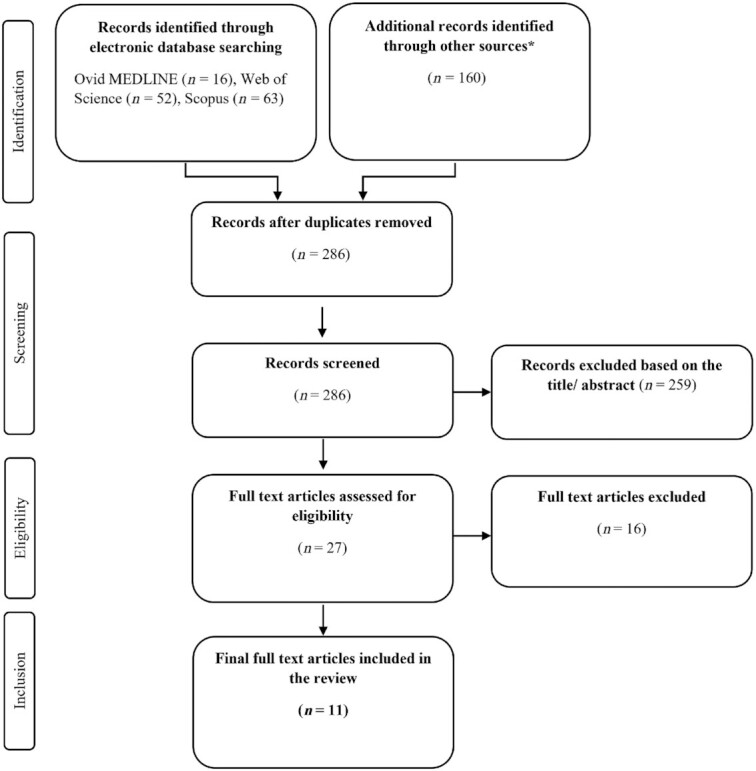

The 2 reviewers met at the beginning of the study to discuss decisions surrounding the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. Sources were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: 1) focused on temporary/seasonal foreign agricultural workers (documented and nondocumented), 2) provided information on the workers’ food security status, 3) within North American contexts (Canada and the United States), 4) published between 1966 and 2020, and 5) published in English (see Figure 3). The criteria were updated based on discussions and consensus of both reviewers, where discrepancies and disagreements were reconciled until consistency and consensus were achieved.

FIGURE 3.

A PRISMA flowchart outlining literature search and selection. PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Article screening and selection

Following the literature search and article retrieval process, the 2 reviewers independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to all citations to assess them for inclusion. Where uncertainty about the relevance of a study from the abstract remained, the full article was retrieved and checked. The 2 reviewers met again during subsequent stages of the abstract review process to discuss challenges related to study selection and search strategy and agree on feasible solutions.

Duplicates were identified and removed using the “highlight duplicate values” and “remove duplicates” functions in Excel. The titles and abstracts of the remaining articles were reviewed and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Full-text articles in the final list were read entirely.

Identification of categories and themes

In appreciating the ethical and professional importance of reflexivity in the literature review process, the authors recognize that their personal backgrounds, values, stances, and perspectives (50) may impact the search, retrieval, and selection of relevant articles; synthesis of knowledge; category and theme identification and classification; as well as interpretation of results. In order to mitigate possible bias, a dual review (56) was conducted where 2 reviewers independently read the full text of the articles included and identified themes for knowledge synthesis (57). Discrepancies in themes identified by the 2 reviewers were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction

Data from each original source were extracted following an inductive coding approach informed by the concepts/ideas identified in the source (58, 59) using a coding template. The template used was designed to enable the extraction of descriptive information on the scope (i.e., extent, focus, and nature) of research regarding food security of TFWs, and summarizing and disseminating the results. For the extent of research, the year of publication and study geographic location were recorded. For the focus of research, data regarding the research question and/or objectives, context, and characteristics of the population involved in the research were extracted. To describe the nature of research, data regarding the type of article, the research approach, and data-collection tools were extracted. In addition, information that reflects original research results from the results and discussion sections of each article was also extracted.

A content analysis, involving a thorough reading of each article and listing the salient themes identified in the abstract, results, and discussion sections of the article, was conducted on each source article included in the review (60). Themes relevant to food security of TFWs working in agriculture were identified through examining the article focus, stated problem, ideas and arguments, and the extent to which the themes were discussed (55). The emerging themes were then collated and organized in an outline connected to their sources. The thematic outline describes and summarizes the identified themes, as well as the content that made up those themes (61), the context in which the themes were conceptualized, the main problem discussed, the study population (the sample), and findings. The various themes identified were compared for similarities and differences (60).

Thematic analysis

The thematic analysis approach was based on the method described by Gasparyan et al. (52), which involves the use of bibliographic cards. In this method, the analysis takes place by theme, where each theme is critically examined from the perspectives of the various sources (articles) that address it. The goal is to understand what these sources say about these themes, how these sources are connected and/or overlap, and what gaps or questions are left to be answered. The analysis section takes a narrative format (61).

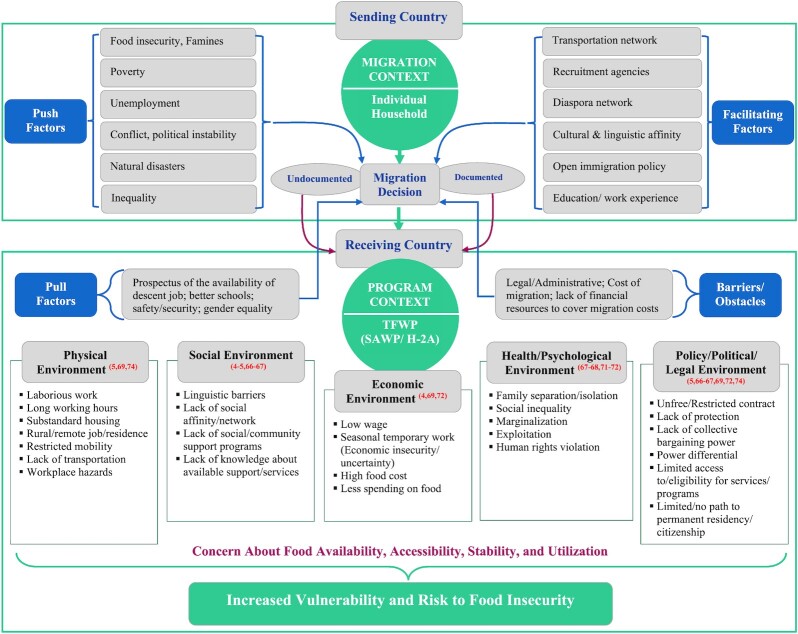

Conceptual framework

Following thematic analysis, we developed a conceptual framework (Figure 4) by integrating factors from both the worker-sending country (country of origin) and worker-receiving country (destination country), particularly those surrounding aspects of the Canadian and the US TFWPs, which might contribute to the food insecurity of TFWs. This was performed via a consensus-driven discussion by the authors. First, we highlighted factors that drive migration as reported in the literature (62) under 4 categories: 1) pushing factors, 2) pulling factors, 3) facilitating factors, and 4) barriers/obstacles. These factors are thought to influence the decision for migration.

FIGURE 4.

Conceptual framework: factors affecting the food security of TFWs. The boxes “Push Factors,” “Pull Factors,” “Facilitating Factors,” and “Barriers/Obstacles” are drivers of migration, and the items associated with each box are example drivers as reported in the literature. The superscript numbers that appear in the boxes “Physical Environment,” “Social Environment,” “Economic Environment,” “Health/Psychological Environment,” and “Policy/Political/Legal Environment” refer to the relevant reference numbers under which food security was discussed. H-2A, US Temporary Agricultural Workers Program; SAWP, Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program; TFW, temporary foreign farm worker; TFWP, temporary foreign worker program.

From the thematic analysis, we identified and grouped factors that were discussed in the article reviewed related to the Canadian and US TFWPs, as well as the conditions under which they live and work, into 5 environments: 1) physical environment, 2) social environment, 3) economic environment, 4) health/psychological environment, and 5) policy, political, and legal environment. Under each environment, we compiled a list of factors that emerged from the content analysis of the reviewed articles, which might impact the food security of TFWs.

Results

A total of 291 articles were identified through the initial search (electronic databases, n = 131; other sources, n = 160). Following the removal of duplicates, there were 286 articles. The titles and/or abstracts of the 286 articles were screened for eligibility and relevance, which resulted in the exclusion of 259 articles that did not meet eligibility criteria. The full texts of the remaining 27 articles were reviewed and read entirely to determine their eligibility for inclusion. Each article was assessed for the depth and extent to which it addressed and discussed the topic and contextual factors (i.e., factors potentially impacting food security of TFWs within the context of the temporary farm work migration, work, and living conditions of TFWs in the host country, as well as aspects surrounding the policies, regulations, and administration of the TFWP) (49). A total of 16 articles were excluded for insufficient relevance and/or contextual discussion. The final review was based on 11 full-text, peer-reviewed articles related to the food security of TFWs from databases (n = 9) and other sources (n = 2). Table 3 lists the articles included in the review and summarizes the characteristics of each individual article.

TABLE 3.

List and characteristics of final literature sources retrieved from the search process1

| Source characteristics | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study (ref), year, source type | Objectives | Context | Study design, location, date | Population, sample size, eligibility criteria | Data-collection method, tool | Main findings | Comments/future research suggested |

| Borre et al. (5) 2010; PR |

|

Vulnerability, food insecurity, and obesity of migrant farm workers within the context of their cultural lifestyle (living and working conditions) | Design not statedEastern North Carolina, USAJune–November 2005 | Families of Latino TFWs hired in agricultural labor during the 2005 season, who attended the ECMHSP at 2 sites (i.e., 2 meetings), and who completed all household interviews and questionnaires (n = 36 adults; all from Mexico except for 2 from Guatemala)Adults 19–45 y; children 2–18 y | Interviews: End of season semi-structured interviews with adult parents (n = 14); home visits (n = 16); focus groups (n = 19)Anthropometric measurements: heights and weights of adults and children over the age of 2 yInstruments: Structured 18-question USDA food security questionnaire in English and Spanish languages; 24-h recall (21 households completed 2 recalls) and diet history completed by mothers (n = 36) |

|

Relation between obesity, insecurity, migration, and working conditions |

| Bowen et al. (4) 2019; PR |

|

LIFWs working in low-pay, labor-intensive farm work full time year-roundLiving in a Spanish-speaking neighborhood with a shared reciprocity system of exchanging healthy food, services, and healthy behavior, and participating in a CFP but with restricted access to health and government-assisted human services and programs | Cross-sectional, rural northeastern county in Pennsylvania, USASeptember 2013–March 2014 | 70 Latino and 41 non-Latino (total 111) immigrant farmworkers who were CFP clientsEligibility: Being >18 y of age and could only participate in 1 of the 2 surveys | Modified bilingual (English and Spanish) CDC's NHANES, and the British Social Attitudes Survey; distributed twice (6 mo apart) |

|

Food security initially was not the focus of the study but was added later and included 1 question only.Limitations:§ Some data were reported missing (e.g., some qualitative responses); qualitative data analyses were limited to some responses, although not explicitly stated in the paper§ Reliability and validity of the survey were not examined§ Information about other sources/program which Latino adults may have used was not collected§ Not all barriers and facilitators to food choices were captured (e.g., availability of cooking facilities) |

| Castañeda et al. (63) 2019; PR | To examine the relation between HFI and obesity and its mediators among migrant Northwest Mexican agricultural workers living in 2 communities close to produce farms in Northwest Mexico | Migrant agricultural workers living and working in a developing country within a context of physically laborious jobs, with poverty, low-cost, high-energy diet | Cross-sectional, Northwest Mexico(Study date not specified) | 146 Adult North Mexican women (n = 83) and men (n = 63) living in 2 agricultural communitiesEligibility: Resided in the communities for at least 4 yExclusion criteria: Pregnant and lactating women | Interview using survey questionnaires (household food security questionnaire developed for Northwest Mexico population, sociodemographic, 24-h recall, and physical activity), and anthropometric measurements (height, weight, and waist circumference) |

|

Limitations:

|

| Hadley et al. (64) 2008; PR |

|

Living and working as an undocumented immigrant in an urban setting in the USA with inability to access health care and social services, and economic disadvantage in the labor market, and uncertainty and unpredictable seasonal work or work schedule | Nonprobability cross-sectional sample5 Neighborhoods within NYC, USA8 October and 5 December 2004 | 431 Undocumented Mexican immigrants living in 12 urban neighborhoods with the highest concentration of migrant Mexicans in NYC, USAEligibility: Adults 18 y or older, self-reported of being born in Mexico (undocumented immigrants), and current resident in NYCExclusion: being born in the USA | Interview in English or Spanish using translated and back-translated structured questionnaire (sociodemographic, date of entry in the USA, use of public assistance in the USA, levels of social and linguistic acculturation, experiences with hunger and self-perceived health, residency status in USA) |

|

Limitations:

|

| ● Uncertain and unpredictablework schedules and limitedaccess to public assistancemay contribute to high levelsof hunger | |||||||

| Kilanowski and Moore (65) 2010; PR | To obtain information from Latino farmworker parents on the level of HFS and food intake of their children | Spanish-speaking, low-income Latino TFW mothers working full time, living in self-reported safe buildings provided by farm owners free of charge, and some have own gardens to grow produce | Descriptive cross-sectionalOhio, USAJune to September 2007 | 50 Latino migrant farmworker mothers of children aged 2–13 yEligibility: TFW parents 18 y and older with children 2 to 13 y of age; ability to give informed consent; ability to complete 3 questionnaires in Spanish or English | Survey questionnaires (self-administered demographic, USDA's HFSSM, and food frequency designed for low-income Latinos); cultural assessment and review |

|

Limitations:

|

| Kilanowski (66) 2013; PR | To present self-management health education on healthy eating to Latina migrant farmworker mothers—phase 3 | US permanent resident Latino farmworker mothers (88%) with children living and working full time in 2 rural farms in 2 states (Florida and Texas) within a context of physically laborious job and poverty (88% earned <$1000/month), USA | Phase 3 of a 2- group pre/post quasi-experimental pilot intervention study titled “Dietary Intake and Nutrition Education (DINE)”California, USA | 59 Migrant farmworker mothers (intervention group, n = 34; comparison group, n = 25) of children (n = 82)Eligibility: Migrant mothers and their children 2 to 12 y old who lived on an agricultural work camp | Instructional sessions for the intervention group (three 1-h classes)Survey questionnaires for both intervention and comparison groups using demographic, acculturation, current and past food security status, self-efficacy; anthropometric measurements (weights and heights of children 2–12 y old); and pre/post-intervention knowledge gain work sheet |

|

|

| ● 54% of mothers receivedfood stamps, and 44%received supplements byWIC | |||||||

| Pulgar et al. (67) 2016; PR | To explore the relation between farm work–related stressors and depressive symptoms in women of Latino farmworker families | Food security of Latino migrant farmworker families within the context of stressors and economic hardship | Study design not stated; data collected from a larger studyNorth Carolina, USA, April 2011–April 2012 | 248 Latino child-mother dyad (25% from migrant farmworker families, and 75% from seasonal farmworker families residing in the same area year-round)Eligibility: Not stated | Fixed-response interview in Spanish using Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale, Migrant Farmworker Stress Inventory, and USDA's HFSSM |

|

Food security was not the focus of the study; rather, it was studied as a measure of, or proxy for, material, economic hardship as one of the independent variables |

| Moreno et al. (68) 2015; PR | To examine the associations between food insecurity and diabetes outcomes among rural Latinos |

|

Cross-sectionalLarge migrant health center system that provides safety-net careTwo rural California counties, USA, July 2009–January 2010 | 250 Latinos adults (78% were from Mexico) with diabetesEligibility: Self-identified as Latino; spoke English or Spanish; had a current diagnosis of diabetes type 2; 18 y of age or greater; had 1 primary care visit to the health center in the last 12 mo | Telephone survey and medical chart abstraction, 6-item USDA's HFSSM |

|

Limitations:

|

| Quandt et al. (69) 2018; PR | To explore potential barriers to and supports for migrant farmworkers’ practice of effective dietary self-management of diabetes | Migrant/seasonal farmworkers with diabetes living in camps (which may be barracks, trailers, old houses, or apartments, either owned or rented by growers or labor contractors) while receiving health and social services | Design not statedRural North Carolina, USAMay–September 2017 (during the agricultural season) | 200 Latino migrant farmworkers with or without diabetes recruited at 23 camps and 7 residencesEligibility: Being at least 18 y of age; currently working in farm work; and self-identified as Latino or Hispanic | Interview, survey in Spanish to collect information about nutrition strategies to diabetes self-managementThree measures were included in the survey: “obtaining food,” “preparing and consuming food,” and “maintaining food security” |

|

Limitations:

|

| Weigel et al. (70) 2007; PR | To examine the prevalence, predictors, and health outcomes associated with food insecurity in 100 TFW households living on the US–Mexico border | Border TFWs living and working on the US side of the border in the Paso del Norte, a region located inside the Chihuahua Desert | Cross-sectionalEl Paso County, Texas, and Dona Ana County, New Mexico (USA–Mexico borders) USA2003 (for 10 mo) | 12,000 Hispanic TFWs and their householdsEligibility: At least 1 adult member in the household had performed paid farm work during the prior 12 mo | Interview, surveyMeasures: food security status, anthropometric, health (physical, mental), clinical, and laboratory examinationsTools used: 18-item USDA's HFSSM, a modified (shortened) version of the main California Agricultural Worker Health Survey (CAWHS) and its female and male health supplements |

|

Limitations:

|

| ● Household participation infood stamps and other typesof assistance programs wasnot a significant predictor offood security status● The majority of adultparticipants were overweight (19%) or obese (66%); female adults’ averageBMI was significantly higherthan males’● Food security was notstatistically significantlyassociated with BMI in bothmale and female participants | |||||||

| Hill et al. (71) 2011; PR | To examine the prevalence of food insecurity in documented and undocumented migrant farmworkers (with and without H-2A visa) in Georgia | Food security within the context of documented (with H-2A visa) vs. undocumented (without H-2A visa) working status | Design not stated Georgia, USA June 2009 | 460 TFWs (most of them Mexican non–H-2A guestworkers with children | Survey, USDA's HFSSM |

|

Limitations:

|

BP, blood pressure; CFP, community food pantry; ECMHSP, East Coast Migrant Head Start Program; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; HFI, household food insecurity; HFS, household food security; HFSSM, Household Food Security Survey Module; LDL-C, LDL cholesterol; LIFW, Latino immigrant farmworker; NYC, New York City; PR, peer-reviewed journal article; ref, reference; TFW, temporary foreign worker; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

All identified sources were peer-reviewed articles published between 2007 and 2019, with the earliest article being published in 2007 (64, 70) and the latest in 2019 (4, 63). The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (n = 10 articles; 91%) (4, 5, 64, 70, 65–69, 71), and 1 study (63) was conducted in Mexico. Six studies (55%) (4, 63–65) were quantitative cross-sectional, 1 study (66) was a quasi-experimental interventional study, and 4 studies (36%) (5, 67, 69, 71) did not state their study design although seemed to follow a cross-sectional approach. The study population in most of the articles were Latino/Mexican/Hispanic TFWs (5, 63–71). However, the study populations of some studies also included non-Latinos (4), immigrants (4, 64), and migrants with nondocumented status (64, 67, 71).

Discussion

Themes

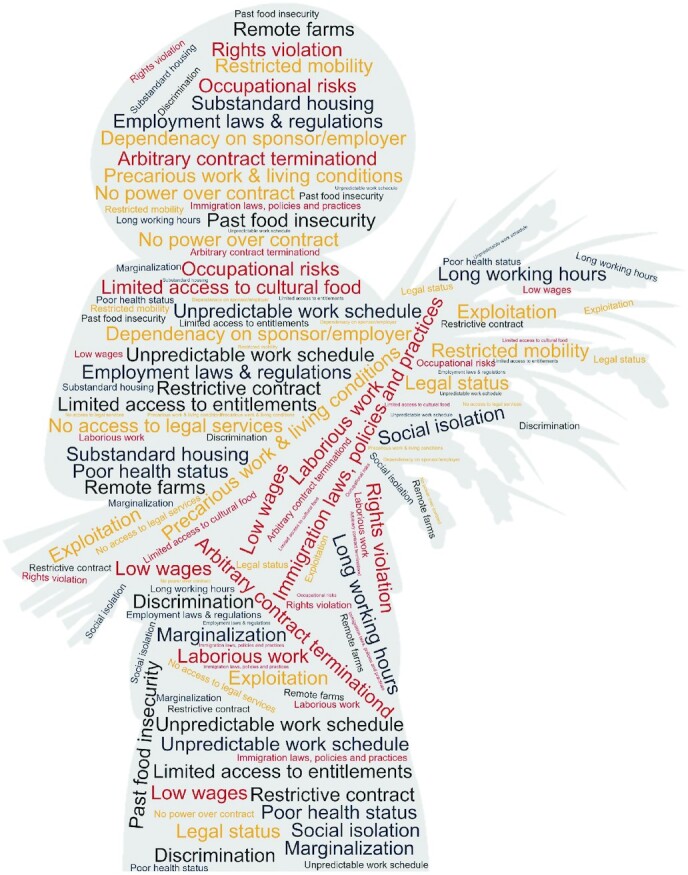

Nine themes related to TFWs and their food security were identified (see Table 4). As noted in Table 3, the reported prevalence of adult, child, and household food insecurity (HFI), with or without hunger, among TFWs and their families ranged from 28% to as high as 87%. The link between the unique environment in which TFWs live and work and their food security was the most common thematic category addressed (4, 5, 63–67, 70, 69, 71). Many scholars describe these conditions as “precarious,” a term which refers to nonpermanent residents and noncitizens, including TFWs, who are authorized and at risk of being unauthorized to live and work in Canada (72–75). Such a precarious living and work culture limits TFWs’ access to entitlements such as health care, legal services, education, as well as public services, programs, and support. This culture includes conditions such as employment laws and regulations, housing, income, social isolation, occupational risks, laborious work, long working hours, unpredictable work schedule, and mobility, among others.

TABLE 4.

Themes and supporting content identified in the review of the literature1

| Theme identified | Content making up the theme2 |

|---|---|

| Income and economic status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Food access, dietary pattern, and healthy food choices |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Housing, availability of kitchen and cooking appliances, and storage space |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Access to health care, public and private services, programs, and support |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nutrition education intervention |

|

|

|

| Vulnerability from migrant farm work and migrant's legal status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Acculturation and length of stay in destination country |

|

|

|

| Past food security and nutritional status at origin |

|

| Health and chronic diseases |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ECMHSCP, East Coast Migrant Head Start Program; HFI, household food insecurity, LIFW, Latino immigrant farmworker; TFW, temporary foreign farm worker.

Cited content does not necessarily reflect exact quotation from original citation and may have been paraphrased.

Theme 1: income and economic status

While many sources use food insecurity and hunger interchangeably, and hunger is frequently perceived conceptually within the context of food insecurity (64), they are not synonymous (76, 77). In fact, the World Food Program deems hunger as “an outcome of food insecurity” (78). For example, when investigating hunger in Canada, Davis and Tarasuk (77) suggested that the distinct situation that leads to hunger stems from inadequate or insecure access to food, but not from problems of food availability or quality. Their definition of hunger reads as follows: “the inability to obtain sufficient, nutritious, personally acceptable food through normal food channels or the uncertainty that one will be able to do so.”

In their study, Hadley et al. (64) measured hunger with a single item, where “respondents were asked whether they had experienced periods in the last six months when they were hungry but were unable to eat because they could not afford enough food.” While this single measure of hunger was used to reduce respondent burden, it did not reflect the full range or severity of food insecurity that might have been experienced in the study population. However, hunger has been associated with engaging in low-paying seasonal labor with an unpredictable work schedule (64). A link between low income and food insecurity among TFWs was also reported by Kilanowski (66). The majority of mothers (80%) reported having very low incomes, and 71% of their households experienced some level of food insecurity. Borre et al. (5) investigated food insecurity among Latino TFWs and suggested that poverty, as a component of the cultural lifestyle of TFWs, drove up the risk of food insecurity. Findings are consistent with the existing literature that food insecurity is strongly income related (79–81). Weiler et al. (34) argue that, while the SAWP may provide temporary improvements to food security, it fails to meaningfully address the structural roots of migrant poverty.

Theme 2: food access, dietary pattern, and healthy food choices

Bowen et al. (4) observed a high prevalence of food insecurity (76%) among TFWs and found that making healthy food choices was subject to the availability of and access to healthy food. The study highlighted that community food pantries (CFPs) may, in many cases, be the only source of healthy food for economically vulnerable families who were less likely to purchase food from the grocery stores due to high cost. Families were more likely to make healthy food choices where available and accessible, but their choices were limited by monthly access to the CFP and high food costs at grocery stores. This aligns with Weiler et al.’s (34) conclusion that the SAWP provides migrant households with increased food access, but at a high cost.

Kilanowski and Moore's (65) study involving Latino TFW families found that 52% of households were food insecure, while only 22% of children aged 6–11 y old met daily minimum food-group serving recommendations. Borre et al. (5) also linked food insecurity (64%; 35% with hunger) to changes in dietary pattern accompanying immigration. For example, participants reported they used to eat 3 meals of locally produced food or food bought in local markets together as a family in their home country, and that this eating pattern changed with immigration to include more frequent consumption of meats, sodas, processed foods, and snacks. The study concluded that reduced energy and nutrient intake was associated with food insecurity, and food insecurity with hunger for adults and children.

Theme 3: housing, availability of kitchen and cooking equipment/appliances, and storage space

Under some TFWPs in Canada and the United States, particularly those related to agriculture such as the SAWP, employers are required to provide housing to hired farmworkers, either on the employer's property or shared with other workers, which may be overcrowded (82). Poor housing increases TFWs’ vulnerability to food insecurity and hunger because workers cannot control these conditions (5). Kitchens often lack adequate, safe, and clean storage for foods, and functioning kitchen appliances (66). Workers may be compelled to buy and consume nonperishable, processed, and pre-packaged foods that do not need refrigeration and do not spoil quickly. Lack of access to a refrigerator and oven puts TFWs at 3 times increased risk for food insecurity compared with workers who had these amenities (71). Overcrowded, and underequipped, housing with inadequate storage and refrigeration space has been described as a barrier to healthy eating, and a risk to ill health (34, 82). However, TFWs working in more rural locations may be protected, as TFWs working on smaller farms characterized by fewer employees and smaller migrant housing camps experienced better food security and their children met daily minimum food-group serving recommendations (65). There is general agreement that the availability of kitchen appliances and cooking utensils in good working condition helps migrant families prepare healthier recipes (5, 66, 71).

Theme 4: access to health care, public and private services, programs, and support

Migrant agricultural workers’ limited access to health care and other government social programs and services that permanent residents and citizens can claim has been at the center of debate and criticism and has also been described as discrimination against TFWs in receiving countries (28, 83). Barriers to health care and other public services can be either direct, such as health and immigration policies that prohibit access, or secondary, such as unintended effects embedded in health and immigration policies, in addition to the precarious immigration status of TFWs (84).

Food insecurity has been observed to be more prevalent among Latino TFWs (52.4%) without health insurance (68). Undocumented TFWs were reported to be at higher risk of food insecurity because they were less likely to access some formal mechanisms, resources, and services (such as health care insurance coverage) that safeguard them from food insecurity (64). Undocumented migrants who received public assistance in the past 6 mo were more protected against hunger (80). However, access to health and social programming may not fully address food insecurity, as migrant families who participated in the East Coast Migrant Head Start Program, which included access to Head Start, Medicaid for uninsured children, and the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), experienced high levels of food insecurity (64% of adults and 56% of children 2–7 y of age) (5). Similarly, other studies reported that the higher participation by food-insecure TFWs in the Food Stamp program and WIC program compared with food-secure counterparts was not a significant predictor of food security status (70, 66).

These findings suggest that enrollment in assistance programs does not fully ameliorate food insecurity concerns. Complicating factors to accessing and using health and social programs may include fear of deportation if their employer knew they were sick (27) and “lack of information on the program eligibility, lengthy work documentation, residency requirements (e.g., 5 years), and additional barriers to access” (4).

Theme 5: nutrition education intervention

Nutrition education has been reported to significantly improve the mean nutrition knowledge of permanent migrant farmworker mothers who live and work in migrant agricultural work camps, especially those with low acculturation levels (66). Children of the migrant farmworker mothers who received nutrition education interventions were significantly more likely to move from the obese to the normal category of BMI. Providing migrant farmworker mothers working in rural farm-work camps access to resources in the form of health-promotion programs may contribute to improvement in their food security status. The study suggests that members of food-insecure migrant households may benefit from improvement in healthy eating behavior and nutrition knowledge facilitated by nutrition education and health promotion intervention. This effect was reflected in changes in mothers’ nutrition knowledge, as well as their child's nutritional indices such as child's BMI and nutritional intake. The study concluded that migrant farmworker mothers, particularly those with past food insecurity experience in the country of origin, who worry about providing adequate food for the children and adults may benefit from similar programs to provide adequate quality and healthful food for their families. Food-insecure adults tend to rely on low-cost, high-energy foods, which likely increases the risk of overweight and obesity (85, 86). The literature shows that food insecurity increases the odds of obesity in children (5 times higher for children from food-insecure households compared with children from food-secure households) (87) and adults (32% higher for adults from food-insecure households compared with adults from food-secure households) (86). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled community trials concluded that school-based nutrition education intervention was effective in reducing the BMI of both children and adolescents (88).

Theme 6: vulnerability to food insecurity associated with migrant seasonal/temporary farm work and migrants’ legal status

Migration to seek seasonal jobs has been described as a livelihood strategy rooted in complex socioecological and environmental factors that determine food insecurity (5). The interconnected social structure, organization, and environment created by government regulations and the dependency of TFWs on the sponsor/employer perpetuate a culture where TFWs are exposed to risks over which they have little control, and make them vulnerable to food insecurity. Migrant temporary/seasonal farm work corresponds to job insecurity as it is characterized by a limited unfree contract, uncertainty of labor demand, and hence an unstable income (2, 3). On the other hand, seasonal farm work attracts many unauthorized or undocumented workers (17) who appear to be the most vulnerable group due to their legal status and eligibility for social programs and services. The prevalence of food insecurity has been observed to be 2 times higher among undocumented TFWs as compared with TFWs with an H-2A visa (67% vs. 33%, respectively) (71). The H-2A program may protect against food insecurity by providing job security, higher wages, access to cooking facilities, meals, and transportation, or other factors.

Theme 7: acculturation and length of stay in the destination country

Hadley et al. (64) reported that the level of acculturation and length of stay in the receiving country did not predict hunger among undocumented TFWs. However, Weigel et al. (70) found that food insecurity with hunger was more frequent among TFWs who had spent ≤10 y in the United States.

Previous research suggests that acculturation is a risk factor for food insecurity (89–91), and that increased acculturation negatively affects adherence to diet recommendations among the immigrant farmworker population (92). However, Matias et al. (92) reported that TFWs with longer residence in the United States (>14 y) were more likely (1.5 times) to meet dietary recommendations.

Theme 8: food security in the country of origin

Past food security status of TFWs in their country of origin may predict current food security. Borre et al. (5) found that the majority of TFWs who reported food insecurity with and without hunger (75% and 67%, respectively) also reported experiencing food insecurity in their home country. Similarly, Kilanowski (66) reported that low levels of past food security were associated with low levels of current household food security. These findings may indicate that historically food insecurity–vulnerable families are most likely to migrate in search of seasonal work and continue to experience challenges related to food insecurity.

Theme 9: health and chronic diseases

The relation between food insecurity and overweight and obesity among TFWs was not consistent among studies. Borre et al. (5) observed that overweight and obesity were prevalent among all adult migrants, whereas 2- to 7-y-old food-insecure children were found to be less overweight and obese than their food-secure counterparts. Castañeda et al. (63) found that obesity was 5 times more likely among farmworkers with a mild HFI. However, a gender difference was noted as HFI protected against obesity among men, likely due to their intense farm-work–related physical activity.

Weigel et al. (70) reported that adult obesity, central body adiposity, elevated blood pressure, and blood lipid and glucose disturbances were common among TFWs, although not directly associated with food insecurity. Of all adult respondents, 19% were overweight, 66% were obese, and 66% had at-risk waist circumferences.

Pulgar et al. (67) determined that women from Latino TFW families with marginal, low, or very low food security were more than twice as likely to report significant depressive symptomatology as those who reported high food security. Similarly, Weigel et al. (70) observed that food-insecure Mexican TFW families in the US-Mexico border area were more likely to have at least 1 member affected by symptoms of depression, anxiety, learning disorders, as well as symptoms suggestive of gastrointestinal infection.

Moreno et al. (68) reported that poor health status was associated with higher risk of food insecurity among Latino TFWs with diabetes. Those who were food insecure were more likely to report cost-related medication underuse, less likely to achieve adequate diabetes control measures, and less likely to receive a dilated eye examination and annual foot examination. In a study that examined nutrition strategies used for diabetes self-management among TFWs, Quandt et al. (69) reported that, although 80% of the study participants reported no food security concerns, the majority (87%) reported that they depended on others for transportation to shop for food from a superstore.

The TFWPs in Canada and the United States share many aspects in common, as they also have differences manifested in other aspects surrounding, in particular, policies, regulations, and administration of the programs (24). For example, TFWs in the United States are largely unauthorized; yet, they remain central to the US economy. In Canada, however, most TFWs are recruited through formal programs, such as the SAWP. This official hiring process may provide TFWs in Canada more protection and more access to public services and programs, such as health care, compared with their counterparts in the United States. Another difference between the 2 programs is the maximum period for which TFWs can stay and work in either country. While TFWs in the United States may stay for 1 y and, under certain conditions, may extend this period for up to 3 y (18), TFWs in Canada may stay for a maximum of 8 mo (22, 31). Although working for a longer time may translate into more income, it may also increase the TFWs’ exposure to the precarious and harsh work and living conditions commonly reported among seasonal farmworkers, extending their vulnerability to food insecurity. An important difference that distinguishes the 2 programs may be in the ethnic background of eligible workers. While the Canadian SAWP is designed exclusively for nationals of Mexico and Caribbean countries, the H-2A program is open to nationals from all countries. This difference is worth considering as it resembles differences in cultural and linguistic affinity and support available for TFWs in the host country that can facilitate or hinder food security of TFWs. At the same time, both the Canadian SAWP and the US H-2A visa program are designed for agriculture-related positions. The culture of agriculture labor migration, as well as the environment in which TFWs in both countries work and live over which they have little or no control and the employer-driven hiring process, which grants employers the authority and control in both countries, remains to a large extent similar and challenging. With these differences and similarities between the 2 programs (see Table 1), the question of whether the findings of TFWs in the United States can be applied to their counterparts working under the Canadian SAWP needs further investigation.

Figure 5 presents a word cloud illustrating aspects associated with TFWs’ vulnerability to food insecurity as most frequently cited in the literature.

FIGURE 5.

Word cloud presenting aspects associated with TFWs’ vulnerability to food insecurity as most frequently cited in the literature. TFW, temporary foreign worker.

Limitations and strengths

Although our scoping review was comprehensive, it had some limitations and challenges. First, the review offers a descriptive narrative of the evidence without an analysis of article quality. Second, although effort was made to select relevant keywords and terminology commonly used in the literature, some possible keywords may have been omitted (93). Our focus was on providing a comprehensive review of the literature (breadth) rather than depth on the topic. Our review offers no assessment of risk of bias or meta-analysis (48, 57). However, since our aim was to rapidly map the literature and the main sources and types of evidence available on a largely understudied and complex topic, this approach was appropriate.

We did not assess interrater reliability. However, the independent reviewers met at the outset and during the review stages for discussions surrounding eligibility criteria and the search process, and interrater reliability, discrepancies, and disagreements were reconciled through discussions until consistency and consensus were achieved.

The coverage of our scoping review was limited to articles written in English. This decision was made because the review team is unable to read other languages and translating articles written in other languages was not feasible due to time and cost considerations. In addition, our search focused predominantly on health- and social sciences–related literature and may have missed some important relevant articles published in other disciplines.

Perhaps the greatest limitation of this review is the potential bias that might have resulted from the search process (e.g., the choice of electronic databases to search) and the selection of relevant articles for the review. The process of knowledge synthesis and content selected for inclusion also allows space for subjectivity. However, we applied rigorous review methods (including dual review for study inclusion and exclusion criteria, screening, and selection), and we followed current standards for the conduct of scoping reviews, as outlined by Arksey and O'Malley (48) and recommendations proposed by Levac and colleagues (47).

This review identified the following gaps in the literature:

Literature that explores food security of TFWs hired under Canadian and US SAWPs is scarce.

There is a need for qualitative studies that explore viewpoints and experiences of TFWs, key informants, and stakeholders about factors contributing to the food insecurity among TFWs in Canada and United States.

Although more difficult to conduct due to the precarious nature of temporary agricultural labor, longitudinal follow-up studies may be useful to examine various factors, including policy-related factors, contributing to food insecurity of TFWs over time.

Table 5 summarizes the current knowledge available in the literature and areas of potential research.

TABLE 5.

Key aspects of current knowledge related to TFWs working under the TFWPs and their food security status in Canada and the United States and potential areas for further research1

| What we know | What we need to know |

|---|---|

| TFWs are among the most vulnerable, racialized, and exploitable groups | What role do the federal and provincial governments who administer the TFWPs, particularly the SAWP both in Canada and the United States, play to protect TFWs from exploitation? |

| The prevalence of food insecurity among TFWs working under the TFWPs is higher than that of other subgroups and the general population (ranges between 28% and 87%) | What aspects of the TFWPs, particularly the SAWP both in Canada and the United States, have the potential to impact food security of TFWs (i.e., policy, legislation and regulation, administration, implementation, and coordination)? |

| A range of public and private programs and services are in place in the destination countries to support eligible TFWs | Are TFWs aware of these programs and services? How do they know about them? If they know, to what extent do they participate in these programs and services? |

| Some TFWs may be eligible for public assistance, programs, and services | What formal strategies and practices exist to ensure that TFWs are informed about existing criteria for their eligibility, scope of coverage, and terms for eligibility? |

SAWP, Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program; TFW, temporary foreign farm worker; TFWP, temporary foreign worker program.

Conclusions

This scoping review aimed to summarize current knowledge from peer-reviewed and non–peer-reviewed literature about factors associated with food insecurity of TFWs within the context of Canadian and US SAWPs and to identify knowledge gaps. The literature that addresses the food security of TFWs, particularly under the Canadian SAWP, is scarce, and we were not able to identify non–peer-reviewed sources that address food security of TFWs in our search. The majority of included studies were observational (quantitative cross-sectional) studies conducted in the United States, whereas none originated in Canada or discussed food security of TFWs within the context of the Canadian SAWP. Overall, TFWs were characterized as a food insecurity–vulnerable group that lived in precarious circumstances that could quickly change due to regulations and employer decisions beyond their control, which was conducive to food insecurity. All sources reported a high prevalence of food insecurity among TFWs, ranging from 28% to 87%. However, some inconsistencies were found between the results pertaining to reported associations between food security and specific social or health programs (e.g., receiving public assistance, participation in the Food Stamp program).

The diverse themes identified in the review reflect specific topics chosen by investigators as relevant to the relation between the food security of TFWs and contextual factors. However, the review did not identify qualitative studies that consider the subjective lived experiences and self-identified perspectives of the TFWs, key informants (government representatives, employers), and SAWP stakeholders about potential factors contributing to food insecurity of TFWs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—SAA-B and HV: study conception and design; SAA-B: data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation and drafting of the manuscript; HV, DB, RRE-S, JW, and GLL: critical review of the manuscript; HV and GLL: editing the manuscript; and all authors: reviewed the results and read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

This research received no specific funding from any funding agency in the government, nongovernment, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: CFP, community food pantry; HFI, household food insecurity; HFSSM, Household Food Security Survey Module; MeSH, Medical Subject Heading, SAWP, Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program; TFW, temporary foreign farm worker; TFWP, temporary foreign worker program; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Contributor Information

Samer A Al-Bazz, College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

Daniel Béland, Department of Political Science, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Ginny L Lane, Margaret Ritchie School of Family and Consumer Sciences, University of Idaho, Moscow, ID, USA.

Rachel R Engler-Stringer, Department of Community Health and Epidemiology, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

Judy White, Faculty of Social Work, University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada.

Hassan Vatanparast, College of Pharmacy and Nutrition, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

References

- 1. Weiler AM. A food policy for Canada, but not just for Canadians: reaping justice for migrant farm workers. Can Food Stud. 2018;5(3):279–84. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taylor JE. Agricultural labor and migration policy. Ann Rev Resource Econ. 2010;2(1):369–93. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weiler AM, McLaughlin J. Listening to migrant workers: should Canada's Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program be abolished?. Dialectical Anthropology. 2019;43(4):381–8. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowen ME, Casolac AR, Colemand C, Monahane L. Community food pantry (CFP) recipients’ food challenges: Latino households with at least one member working as farm worker compared to other CFP households. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2019;14(1-2):128–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Borre K, Ertle L, Graff M. Working to eat: vulnerability, food insecurity, and obesity among migrant and seasonal farmworker families. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(4):443–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wadsworth G, Rittenhouse T, Cain S. Assessing and addressing farm worker food security: Yolo County, 2015. Davis (CA): California Institute for Rural Studies; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Russo R. Collective struggles: a comparative analysis of unionizing temporary foreign farm workers in the United States and Canada. Houston J Int Law. 2018;41(1):51. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fernandez L, Read J, Zell S. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA). [Internet]. 2013; [cited 2020 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/reports/migrant-voices. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stevens K. Canada's temporary immigration system. (Special report: Immigration Law). Law Now;2009;34(2):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kachulis E, Perez-Leclerc M. Temporary foreign workers in Canada. Ottawa (Canada): Library of Parliament; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Meyer-Robinson R, Burt M. Sowing the seeds of growth: temporary foreign workers in agriculture. Ottawa (Canada): The Conference Board of Canada; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Caxaj CS, Cohen A. “I will not leave my body here”: migrant farmworkers' health and safety amidst a climate of coercion. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15):2643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Molnar P. The Canadian encyclopedia. [Internet]. 2018; [cited 2020 Nov 5]. Available from: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/canadas-temporary-foreign-worker-programs. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prokopenko E, Hou F. How temporary were Canada's temporary foreign workers?. Ottawa (Ontario): Statistics Canada; Research paper series no. 402. Statistics Canada, Analytical Studies Branch Issuing Body; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Employment and Social Development Canada . Government of Canada. [Internet]. 2019; [cited 2020 Nov 6]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/foreign-workers/reports.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Employment and Social Development Canada . What we heard: primary agriculture review, Sector Policy Division. Government of Canada; 2019. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/services/foreign-workers/reports/primary-agriculture.html [Google Scholar]

- 17. Trautman L. Comparing U.S. and Canadian foreign worker policies. Border Policy Brief. 2014;9(3):5. [Google Scholar]