Abstract

Helicobacter pylori strains can be divided into two groups, based on the presence of two unrelated genes, iceA1 and iceA2, that occupy the same genomic locus. hpyIM, located immediately downstream of either gene, encodes a functional CATG-specific methyltransferase. Despite the strong conservation of the hpyIM open reading frame (ORF) among all H. pylori strains, the sequences upstream of the ORF in iceA1 and iceA2 strains are substantially different. To explore the roles of these upstream sequences in hpyIM regulation, promoter analysis of hpyIM was performed. Both deletion mutation and primer extension analyses demonstrate that the hpyIM promoters differ between H. pylori strains 60190 (iceA1) and J188 (iceA2). In strain 60190, hpyIM has two promoters, Pa or PI, which may function independently, whereas only one hpyIM promoter, Pc, was found in strain J188. The XylE assay showed that the hpyIM transcription level was much higher in strain 60190 than in strain J188, indicating that regulation of hpyIM transcription differs between the H. pylori iceA1 strain (60190) and iceA2 strains (J188). Since the iceA1 and iceA2 sequences are highly conserved within iceA1 or iceA2 strains, we conclude that promoters of the CATG-specific methylase gene hpyIM differ between iceA1 and iceA2 strains, which leads to differences in regulation of hpyIM transcription.

In bacteria, DNA methylation is performed by methyltransferases (methylases). Each methylase has its own recognition sequence, and the nucleotide to be methylated is present within this sequence. Site-specific DNA methylation can change the three-dimensional structure of DNA, affect interactions between DNA and sequence-specific DNA binding proteins, and consequently have varied cellular functions. Among these functions are host-specific defense mechanisms (3). Bacteria usually possess two opposing enzyme activities, DNA restriction and methylation. By working together, they limit the spread of invading DNA molecules within the bacterial population and protect host DNA from digestion. In addition, DNA methylation may be involved in other cellular processes, including DNA mismatch repair, regulation of chromosomal DNA replication, and transposon movement (4).

Helicobacter pylori colonizes the human stomach (6, 7), which enhances the risk of peptic ulcer disease and gastric adenocarcinoma. H. pylori DNA is highly methylated on both adenine and cytosine residues, and the methylation patterns appear unique among various strains (26). However, despite their potential importance, mechanisms of DNA methylation in H. pylori are not well studied. hpyIM, a CATG-specific methylase gene (27) in H. pylori, has been cloned and identified. Study of hpyIM may help us understand DNA methylation in H. pylori.

The hpyIM open reading frame (ORF) is highly conserved among various strains (27). However, the sequences upstream of hpyIM, where its promoter presumably is located, are substantially different, as shown in studies of iceA, the gene immediately upstream (19). Two families of iceA sequences are present at the same genomic location and are designated iceA1 and iceA2. iceA1 has strong homology to nlaIIIR, which encodes a CATG-specific restriction endonuclease (NlaIII) in Neisseria lactamica, but iceA2 has no homology to any known gene (11, 17). U.S. and Dutch patients colonized by strains of the iceA1 genotypes have significantly higher levels of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 8 in the gastric mucosa and higher rates of peptic ulcer disease than those carrying iceA2 strains (19, 23), but the specific mechanisms involved are not known.

To test whether these two unrelated genes, iceA1 and iceA2, function as two different types of promoters for hpyIM expression (iceA1 and iceA2 types), we sought to identify the necessary promoter regions of hpyIM among iceA1 and iceA2 strains. A series of deletion mutations was created in the genomes of H. pylori strains 60190 (iceA1) and J188 (iceA2), and the hpyIM promoter regions were determined based on the CATG modification status of the genomic DNAs from each deletion mutant. The hpyIM transcriptional start sites also were determined. To evaluate the effect of the two types of promoters on hpyIM gene expression and regulation, XylE assays were performed in this study.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, growth conditions, and reagents.

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Growth conditions for Escherichia coli and H. pylori strains were similar to those described previously (27). Restriction enzymes and digestion buffers were obtained from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass.) or Promega (Madison, Wis.). Oligonucleotides used in this study were synthesized at the Vanderbilt University Cancer Center DNA Core Facility using a Milligen 7500 DNA synthesizer.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | F− φ80dlacZΔM15 Δ(lacZYA-argF)U169 recA1 hsdR17(rK−mK+) | 25 |

| H. pylori | ||

| 60190 | iceA1 | 19 |

| J166 | iceA1 | 19 |

| J178 | iceA2 | 19 |

| J188 | iceA2 | 19 |

| 60190M− | hpyIM::xylE/kan | 27 |

| J188M− | hpyIM::xylE/kan | 27 |

| 60190SM1 | iceA1-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with −545 to −334 bp upstream of hpyIM deleted | This study |

| 60190SM1Ω | iceA1-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with Ω terminator | This study |

| 60190SM2 | iceA1-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with −545 to −216 bp upstream of hpyIM deleted | This study |

| 60190SM3 | iceA1-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with −545 to −128 bp upstream of hpyIM deleted | This study |

| 60190SM4 | iceA1-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with −545 to 0 bp upstream of hpyIM deleted | This study |

| J188SM1 | iceA2-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with −653 to −300 bp upstream of hpyIM deleted | This study |

| J188SM2 | iceA2-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with −653 to −200 bp upstream of hpyIM deleted | This study |

| J188SM3 | iceA2-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with −653 to −100 bp upstream of hpyIM deleted | This study |

| J188SM4 | iceA2-hpyIM::xylE/kan, with −653 to 0 bp upstream of hpyIM deleted | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pQX2201 | iceA1-hpyIM of 60190 in pT7blue | This study |

| pQX2301 | iceA2-hpyIM of J188 in pT7blue | This study |

| pT7 Blue | Cloning vector, Ampr | Novagen |

| pBlue Ω | Smr/Spcr with T4 transcription and translation terminators | 20 |

DNA techniques.

All DNA techniques, including chromosomal and plasmid DNA preparation, PCR, Southern blotting, DNA sequencing, and DNA transformation, have been described (27). Computer analyses of DNA sequences and database similarity searches were performed with the Genetics Computer Group programs (2).

Construction of plasmids.

Plasmids pSM1/60190, pSM2/60190, pSM3/60190, and pSM4/60190 were constructed as follows. An insert was constructed by ligation of three DNA fragments: 5′ and 3′ flanking fragments from the cysE-iceA-hpyIM locus and a central fragment (xylE/kan cassette). The 2.4-kb xylE/kan cassette containing a reporter gene and a kanamycin resistance gene was generated as described previously (27). The 5′ flanking fragment was created by PCR using 60190 chromosomal DNA as a template and CysE-1 (5′TCATGCTAGATCTGTTTTATAGCCT3′) and IceA-R as primers, followed by digestion with KpnI. Each 3′ flanking fragment that carried a deletion in the iceA1-hpyIM region was made by PCR using 60190 DNA as a template and the primers RM8 (5′CTTATTCAAGCGGTATTTAAGCGA3′) and SM-1, SM-2, SM-3, or SM-4. The resulting fragments were ligated with the xylE/kan cassette and then with pT7blue, transformed into DH5α competent cells, and selected on Luria-Bertani medium with carbenicillin. Carr clones were examined by using both PCR and DNA sequencing to confirm the correct constructions. The plasmids pSM1/J188, pSM2/J188, pSM3/J188, and pSM4/J188 were constructed in a way parallel to that used for their respective plasmids designed for strain 60190, using J188 DNA as a template and CysE-2 (5′CTAGCGCATGCGTTGCACAAG3′) with IceA-R2 or Meth-5 (5′GCTCTTCAATTTTAGACGC3′) with JSM-1, JSM-2, JSM-3, or JSM-4 as primers. The plasmid pSM-1Ω was constructed by inserting a 175-bp omega terminator from the plasmid pBlueΩ (20) at the NotI site downstream of the xylE/kan cassette in the plasmid pSM-1/6 0190.

Construction of H. pylori iceA-hpyIM deletion mutants.

H. pylori cells from 24- to 36-h cultures of strain 60190 or strain J188 were used as recipient cells, and plasmid DNA (pSM-1/60190, pSM-2/60190, pSM-3/60190, or pSM-4/60190 for 60190; pSM-1/J188, pSM-2/J188, pSM-3/J188, or pSM-4/J188 for J188) was used as donor DNA. Transformation and selection for kanamycin-resistant colonies were described previously (27). The Kanr clones were examined by PCR and by Southern hybridization using probes corresponding to either hpyIM or the xylE/kan cassette.

RNA techniques.

H. pylori was grown in Brucella broth for 20 to 24 h and then harvested by centrifugation. Preparation of total RNA was performed using the TRI REAGENT (Molecular Research Center Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio). Primer extension was performed as described previously (10). To perform primer extension analysis, the oligonucleotides Meth3 (5′ATCATGGCCTACAACCGCATGGAT3′) or Meth3p (5′TTCATTGCAACCGCTATAAAGTAG3′) were used to localize transcriptional initiation sites for hpyIM. A sequencing ladder with the same primer was generated using a sequencing kit from Amersham Life Science (Cleveland, Ohio) and the plasmids pQX2201 or pQX2301 as templates.

XylE enzyme activity assay.

xylE encodes catechol 2,3-dioxygenase, a ring cleavage enzyme converting catechol to 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde, producing a bright yellow color (16). The xylE assay was performed as described previously (12, 16, 28). H. pylori cells were grown in Brucella broth for 24 h. The cell density was quantified and standardized by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). One unit of XylE enzyme activity is defined as the amount of enzyme that oxidizes 1 mmol of catechol per min per OD600 of cells at 24°C. The molar extinction coefficient of 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde is 4.4 × 104 (28).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The DNA sequence of the iceA2-hpyIM locus in H. pylori strain J188 has been submitted to the GenBank database under accession number AF250225.

RESULTS

Diversity of sequences upstream of hpyIM in iceA1 and iceA2 strains.

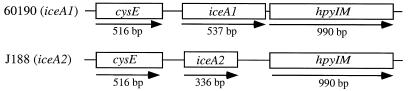

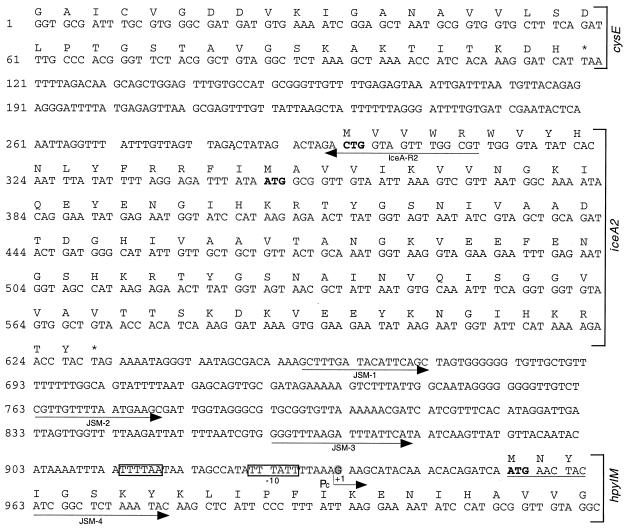

The sequence of the cysE-iceA-hpyIM locus in H. pylori strain J188 was determined and compared to that in strain 60190 (Fig. 1). cysE and hpyIM are conserved (with 85 and 94% identity) between the two strains, whereas iceA is not (with only 38% identity), which is consistent with previous findings (11, 19). The ORFs of cysE and hpyIM are 516 and 990 bp, respectively (Fig. 1), while the longest potential iceA1 ORF in strain 60190 is 537 bp, starting from TTG, and the longest iceA2 ORF in strain J188 is 336 bp, starting from CTG (Fig. 1). The diversity between the two loci begins 81 bp after the cysE ORF and ends just before the hpyIM ORF. We sought to investigate whether these two unrelated regions in H. pylori 60190 (iceA1 strain) and J188 (iceA2 strain) function as different promoters for hpyIM.

FIG. 1.

Comparison of H. pylori iceA1 and iceA2 loci. Schematic representation of the cysE-iceA-hpyIM loci in H. pylori strains 60190 (iceA1) and J188 (iceA2). The ORFs are represented by open boxes. The lines between the boxes represent noncoding regions. Each arrow represents the deduced direction of transcription.

Construction of H. pylori strain 60190 mutants with deletions upstream of hpyIM

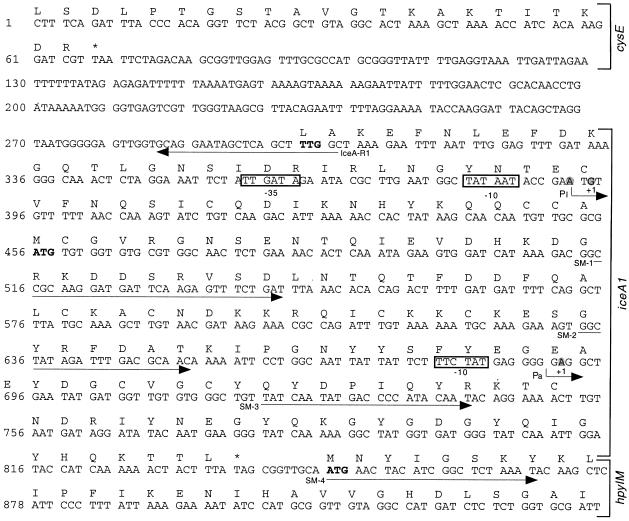

To define the region necessary for hpyIM expression in iceA1 strains, we constructed isogenic mutants of H. pylori strain 60190 with a series of deletions in the iceA1-hpyIM locus (Fig. 2 and 3A). In each mutant, the deleted region was replaced by the xylE/kan cassette, which has the same orientation as for iceA1 and hpyIM, and the promoterless xylE reporter was located immediately downstream of one of the predicted iceA1 start sites (TTG) in H. pylori 60190 (19). Thus, the mutant strains 60190SM1, 60190SM2, 60190SM3, and 60190SM4 are identical upstream of xylE/kan and possess 334, 216, 128, or 0 bp, respectively, of the intact region between xylE/kan and the hpyIM ORF.

FIG. 2.

The 937-bp cysE-iceA1-hpyIM region in H. pylori strain 60190. Partial cysE and hpyIM sequences and full iceA1 DNA sequences with their deduced protein sequences are presented. The potential translation start sites in iceA1 and hpyIM are in bold letters. The sequences of primers IceA-R1, SM-1, SM-2, SM-3, and SM-4 are underlined, and the arrows indicate the directions of primers. The sequences between IceA-R1 and SM-1, SM-2, SM-3, or SM-4 are deleted in plasmids pSM-1, pSM-2, pSM-3, or pSM-4 and mutants 60190SM1, 60190SM2, 60190SM3, or 60190SM4. The transcription start (+1) sites mapped by primer extension analysis are shaded. The bent arrows, labeled with the designated promoter names Pa and PI, indicate the direction of RNA. The putative −10 and −35 hexamers are boxed.

FIG. 3.

Deletion analysis of the hpyIM promoter of the iceA1 H. pylori strain 60190. (A) Schematic representation of hpyIM structures in wild-type H. pylori 60190 (60190wt), hpyIM mutant (60190M−), and mutants with deletion upstream of hpyIM (60190SM1, 60190SM2, 60190SM3, and 60190SM4). The dotted lines represent the deleted regions upstream of hpyIM, and the solid lines represent the intact regions. The positions of the deletion regions are labeled under the lines. Susceptibility to NlaIII digestion and DNA modification status at CATG sites are indicated in the panels at the right. Plus signs represent “digestible by NlaIII” or “with modification at CATG sites”; minus signs carry the opposite meanings. (B) Examination of the effects of deleting sequences upstream of hpyIM on CATG modification of the DNA. Chromosomal DNA from wild-type H. pylori 60190, its hpyIM mutant, and its deletion mutants was digested with NlaIII or HindIII or left uncut, and the digested products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel. The recognition sequences for NlaIII or HindIII are shown at the right.

Assay of hpyIM promoter activities in the H. pylori 60190 deletion mutants.

H. pylori hpyIM encodes a methylase that specifically modifies DNA at CATG sites, providing resistance to NlaIII digestion (27). The mutated hpyIM in 60190M− has no methylase function, which renders its chromosomal DNA susceptible to NlaIII digestion. Therefore, we used the CATG modification status of H. pylori DNA in each of the mutants to determine the effect of the deletion on hpyIM expression. Chromosomal DNA was isolated from these mutant strains and subjected to digestion by restriction endonucleases, NlaIII and HindIII (as a control) (Fig. 3B). DNAs from 60910wt and 60190M−, as positive and negative controls for CATG modification, respectively, were digested in parallel. As expected, DNA from all strains was digested by HindIII, indicating that each DNA was of sufficient purity to permit endonuclease digestion. Also, as expected, the DNA from the wild-type strain was resistant to NlaIII, while the DNA from the hpyIM::xylE mutant was digestible, indicating that CATG modification was present in 60190wt but not in 60190M−. DNA from the deletion mutant 60190SM1 was completely resistant to digestion. In contrast, DNA from 60190SM2 was partially digested, and DNA from 60190SM3 and 60190SM4 was completely digestible by NlaIII. These results indicate that the mutant strain 60190SM1, with a 334-bp intact sequence upstream of hpyIM, had CATG modification in its chromosomal DNA, and thus hpyIM was functional, whereas the mutant strains 60190SM2, 60190SM3, and 60190SM4, with a ≤215-bp intact sequence upstream of hpyIM, either partially or completely lost their ability to modify DNA at CATG sites. Thus, these data indicate that the promoter of hpyIM in strain 60190 is located in the 334-bp upstream region of hpyIM.

In each of the deletion mutants, the kan cassette was located upstream of and in the same orientation as hpyIM (Fig. 3A), a location suggesting the possibility that the kan promoter may affect hpyIM expression. However, the fact that DNA from 60190SM3 and 60190SM4 was completely digestible by NlaIII suggests that the kan promoter had little effect on hpyIM expression. To rule out the possibility that any part of the kan sequence contributes to the full expression of hpyIM in the mutant 60190SM1, a 140-bp T4 phage translational and transcriptional terminator from the omega cassette (20) was inserted downstream of the xylE/kan cassette to create the mutant strain 60190SM1Ω. DNA from this mutant was resistant to NlaIII and susceptible to HindIII digestion, respectively (data not shown), which confirms that the 334-bp region upstream of hpyIM itself possesses a functional promoter sufficient to drive full expression of hpyIM.

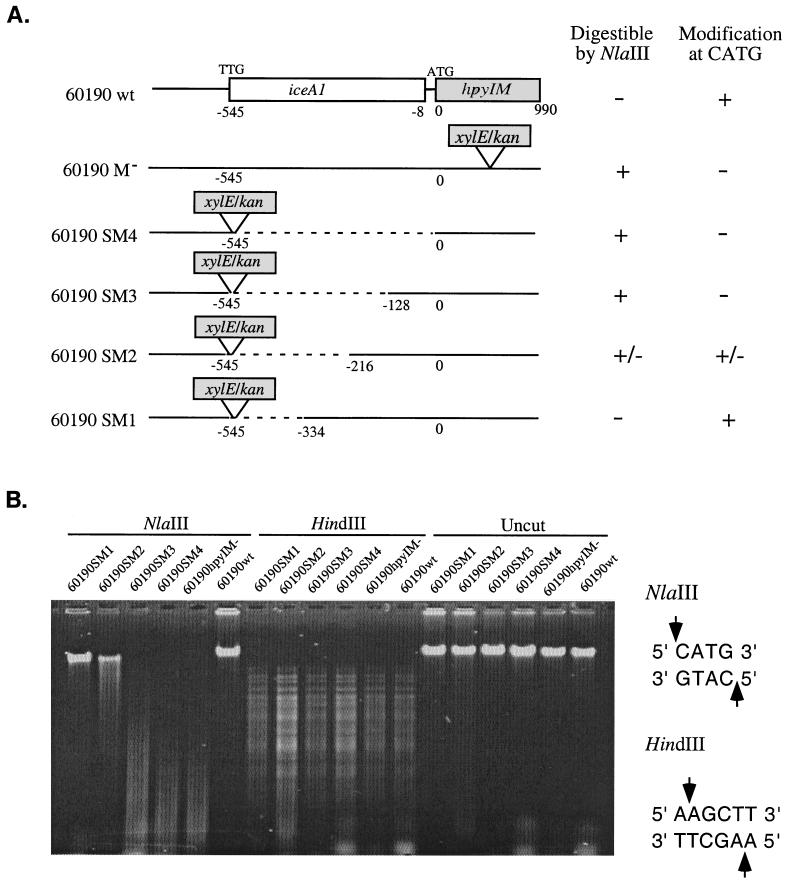

Primer extension analysis to identify hpyIM transcription start sites in H. pylori 60190.

To determine the transcription initiation sites of hpyIM in strain 60190, primer extension analysis was performed. Extension from the oligonucleotide Meth3 resulted in one product (232 nucleotides long) corresponding to an initiation site at the A residue (Fig. 4A) 157 nucleotides upstream of the start site of the hpyIM ORF (Fig. 2). This result is consistent with the deletion analysis results, in which mutant 60190SM3 (having a 128-bp upstream sequence intact of the hpyIM ORF) had no hpyIM activity. To further confirm this result, the oligonucleotide Meth3p, which is 70 bp upstream of Meth3, also was used for primer extension studies. Extension from this primer resulted in two products. One product (162 nucleotides long) corresponded to the same initiation site, as indicated by the Meth3 study (data not shown), confirming the presence of a promoter, designated Pa, upstream of this site (Fig. 2). Another product (445 to 458 nucleotides long) corresponded to a region, 5′GTTTTTAACCAAAG3′ (Fig. 4B), that is 441 to 454 nucleotides upstream of the hpyIM ORF (Fig. 2). The exact location of this extremely long product is difficult to determine because the sequencing ladder becomes compressed in this region. However, the presence of this extension product is consistent with our previous analysis of the strain 60190 iceA1 transcripts (10), in which two initiation sites (G and A) were identified 454 and 456 nucleotides upstream of the hpyIM ORF (Fig. 2) when the primer R7 (356 bp upstream of Meth3p) was used. This upstream promoter, designated PI (Fig. 2), was deleted in mutants 60190SM1, 60190SM2, 60190SM3, and 60190SM4. However, hpyIM was functional in strain 60190SM1, indicating that in addition to the upstream promoter (PI), the promoter Pa located in the 177-bp region upstream of the +1 site may function independently to drive hpyIM expression and provides full protection of cellular DNA from digestion by its cognate endonuclease.

FIG. 4.

Primer extension analysis of the hpyIM transcript in the iceA1 H. pylori strain 60190. (A) The 32P-labeled Meth3 primer was used in this analysis. The corresponding sequencing ladder is shown, and the arrow indicates the nucleotide position of the +1 site (residue A) that is 157 nt upstream of the hpyIM ORF (see Fig. 2). (B) The 32P-labeled Meth3p primer was used in this analysis. The arrow indicates the position of the extension product, which corresponds to a region 441 to 454 nt upstream of the translation start site (see Fig. 2).

There is a 157-nucleotide (nt) untranslated region in the hpyIM transcript derived from the Pa promoter. Analysis of the sequences upstream of the transcription initiation sites also reveals that hexamers with homology to the −10 consensus sequence (TATAAT) in E. coli (9, 15) are present at −10 positions, TTCTAT for the Pa promoter and TATAAT for the PI promoter. A sequence homologous to the E. coli −35 (TTGACA) hexamer (9, 15) is present at the −35 position of the PI promoter (TTGATA) but not for the Pa promoter. The mutant 60190SM2 has a 216-bp intact sequence upstream of the hpyIM ORF that includes the −10 and −35 regions. However, DNA from this mutant was only partially resistant to NlaIII digestion, indicating that additional elements are needed for full hpyIM expression.

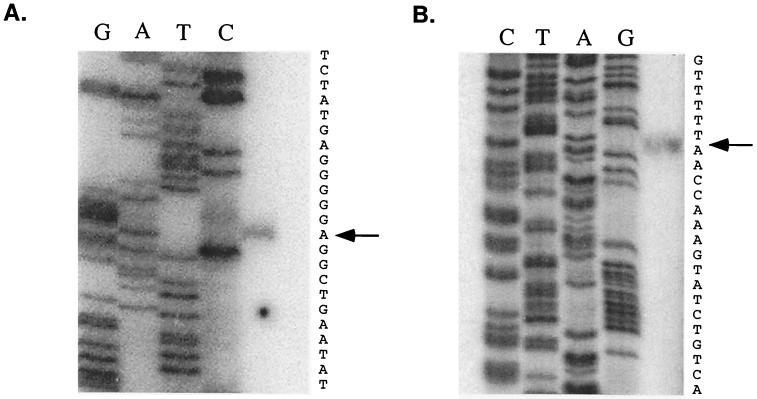

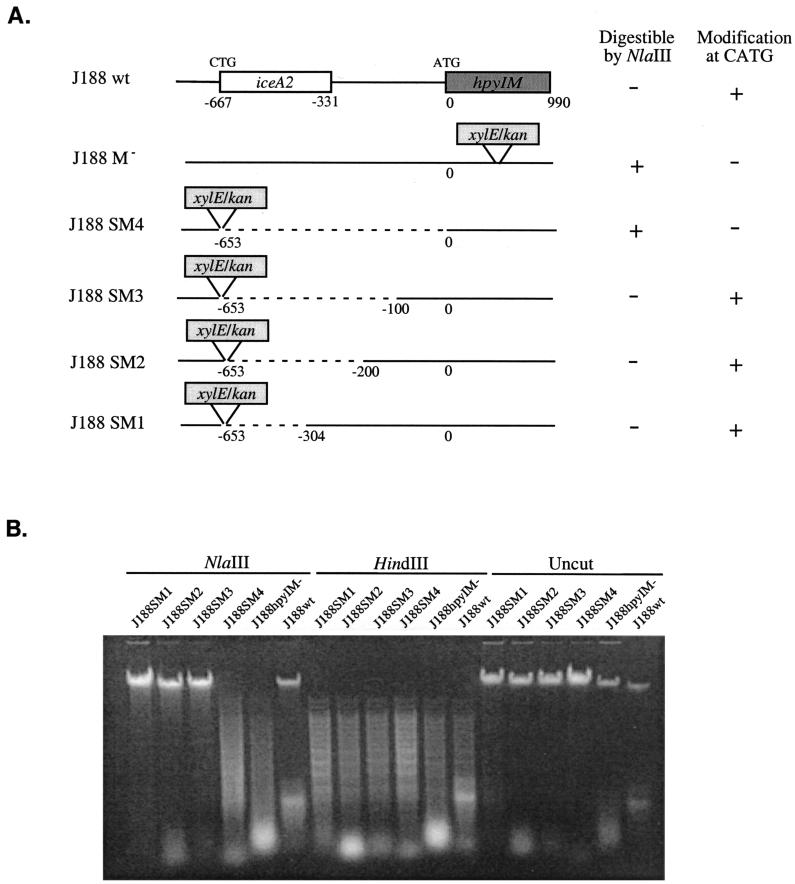

Construction of H. pylori strain J188 mutants with a series of deletions upstream of hpyIM.

To define the region that is necessary for hpyIM expression in iceA2 strains, we constructed isogenic mutants of H. pylori strain J188 that targeted the iceA2-hpyIM locus, in parallel to the hpyIM deletion mutants of strain 60190 (Fig. 5). As with the 60190 deletion mutants, the deleted regions were replaced by the xylE/kan cassette, in the same orientation as iceA2. Mutant strains J188SM1, J188SM2, J188SM3, and J188SM4 are identical upstream of the promoterless reporter xylE, located downstream of one of the predicted iceA2 start sites (CTG) in H. pylori strain J188, and possess 304, 200, 100, or 0 bp, respectively, of intact region upstream of hpyIM (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 5.

The 1,023-bp cysE-iceA2-hpyIM region in H. pylori strain J188. Partial cysE and hpyIM sequences and full iceA2 DNA sequences with their deduced amino acid sequences are presented. Potential translational start sites in iceA2 and hpyIM are in bold letters. The sequences of primers IceA-R2, SM-1, JSM-2, JSM-3, and JSM-4 are underlined, and the arrows show the directions of primers. The sequences between IceA-R2 and JSM-1, JSM-2, JSM-3, or JSM-4 are deleted in plasmids pSM-1/J188, pSM-2/J188, pSM-3/J188, and pSM-4/J188 and in mutants J188SM1, J188SM2, J188SM3, and J188SM4. A transcriptional initiation(+1) site is shaded (G). A bent arrow, labeled with the designated promoter name Pc, indicates the direction of transcription. The putative −10 and TTTTAA regions for the promoter Pc are boxed.

FIG. 6.

Deletion analysis of the hpyIM promoter of the iceA2 H. pylori strain J188. (A) Schematic representation of hpyIM structures in the wild-type strain J188 (J188wt), hpyIM mutant (J188M−), and mutants with deletions upstream of hpyIM (J188SM1, J188SM2, J188SM3, and J188SM4). (B) Examination of the effects of deleting sequences upstream of hpyIM on CATG modification of the DNA. Chromosomal DNA from the wild-type strain J188, its hpyIM mutant, and its deletion mutants was digested with NlaIII and HindIII or was uncut, and the digested products were resolved on a 1% agarose gel.

Assay of hpyIM promoter activities in the H. pylori J188 deletion mutants.

To analyze the CATG modification status of the hpyIM mutants of strain J188, chromosomal DNA from these mutants was digested with the restriction endonucleases NlaIII and HindIII (Fig. 6B). DNA from J188wt and J188M−, used as positive and negative controls for CATG modification, respectively, was digested in parallel. As expected, DNA from all strains was digested by HindIII, and DNA from the hpyIM::xylE mutant was digestible by NlaIII, whereas DNA from the wild-type strain was resistant. DNA from mutants J188SM1, J188SM2, and J188SM3 was completely resistant, while DNA from J188SM4 was digestible by NlaIII. The results indicate that J188 mutants with as little as 100 bp of intact sequence upstream of the translational start site in hpyIM have a functional hpyIM gene and that in strain J188, a sufficient hpyIM promoter is located within 100 bp upstream of this start site.

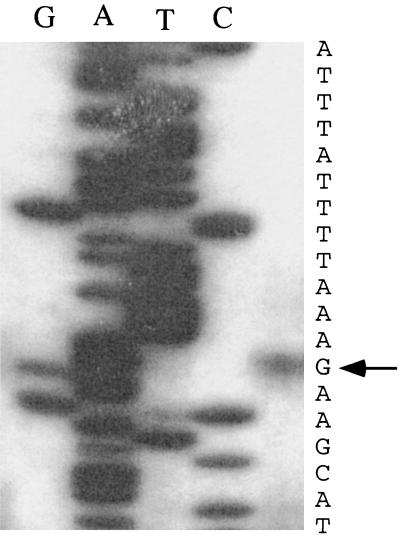

Primer extension analysis to identify hpyIM transcription start sites in H. pylori J188.

Next, primer extension analysis was performed to determine the transcription initiation site of hpyIM in strain J188. Extension from the primer Meth3 resulted in a product corresponding to an initiation site at a G residue (Fig. 7), 21 nucleotides upstream of the start of the hpyIM ORF (Fig. 5). This transcription initiation site of the J188 hpyIM promoter, designated Pc, is consistent with results of NlaIII digestion, in which DNA of J188SM3 (with a 100-bp intact region upstream of hpyIM) was completely resistant, while DNA of J188SM4 (with no intact region upstream of hpyIM) was NlaIII digestible. Sequences with partial homology to the −10 promoter element in E. coli were found at the −10 (TTTATT) position of the Pc promoter, but no E. coli −35 element was found at the −35 position. The motif TTTTAA, conserved in H. pylori promoters (24), was identified 11 bp upstream of the −10 element.

FIG. 7.

Primer extension analysis of the hpyIM transcript in the iceA2 H. pylori strain J188. The 32P-labeled Meth3 primer was used for the analysis. The corresponding sequencing ladder is shown, and the arrow indicates the nucleotide position of the +1 site (residue G), which is 21 nucleotides upstream of the hpyIM ORF (see Fig. 5).

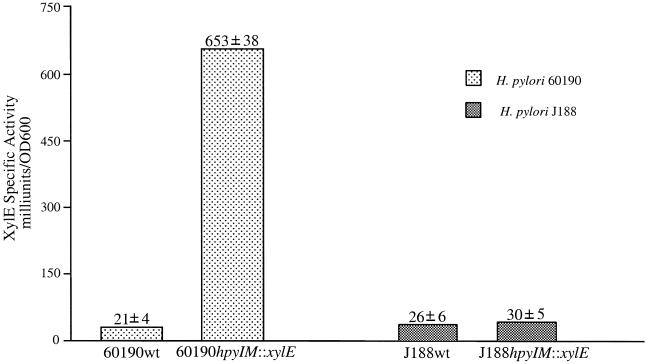

Comparison of hpyIM transcription levels in H. pylori strains 60190 and J188.

In the hpyIM mutants 60190M− and J188 M−, promoterless xylE carrying a ribosomal binding site was inserted into the middle of the hpyIM ORF, forming xylE::hpyIM transcriptional fusions (Fig. 3A and 6A). To investigate whether the different hpyIM promoters among the iceA1 and iceA2 strains differentially regulate hpyIM at the transcriptional level, 60190M− and J188M− and their wild-type strains, 60190wt and J188wt, were examined for XylE activity. The XylE activity in the reporter strain 60190M− was 653 ± 38 mU/OD600 (Fig. 8), substantially greater than the basal level of xylE activity (21 ± 4 mU/OD600) in the control (xylE−) 60190wt strain (Fig. 8), indicating the presence of hpyIM promoter activity in 60190. In contrast, the xylE activity in H. pylori J188M− was similar to the basal level of XylE activity in J188wt (Fig. 8), indicating no detectable hpyIM promoter activity in J188. These data indicate that hpyIM expression between H. pylori 60190 and J188 differs at the transcriptional level.

FIG. 8.

XylE activity of H. pylori strains 60190M− and J188M− (H. pylori hpyIM::xylE transcriptional reporter strains). Specific XylE activities (milliunits per OD600 per milliliter) were determined by using H. pylori cells that had been grown for 24 h. Results represent the mean ± standard deviation for three assays.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that the promoters for hpyIM differ between H. pylori strains possessing iceA1 (60190) and iceA2 (J188). Comparison of iceA1 sequences from 37 H. pylori strains available in GenBank demonstrated that the sequences are either identical or nearly identical to that of strain 60190 in the hpyIM promoter regions (data not shown). Alignment of the J188 iceA2 sequences with those from six other iceA2 strains in GenBank also showed strong similarities in the hpyIM promoter regions (data not shown). Thus, the respective hpyIM promoters identified in this study likely represent these in other iceA1 and iceA2 strains.

In the iceA1 strain 60190, hpyIM transcripts have two initiation sites, located 157 or 454 to 456 bp upstream of the hpyIM ORF start site, driven by the promoters Pa and PI, respectively. hpyIM is cotranscribed with a 384-bp ORF in iceA1 (Fig. 2) to produce an ∼1,460-nt major mRNA transcript (10), suggesting that the PI promoter is a major promoter for hpyIM expression. However, the mutant 60190SM1, in which the PI promoter was deleted, had full M.HpyI activity, indicating that the promoter Pa may function independently and sufficiently to drive hpyIM expression. While hpyIM transcription in the iceA1 strain 60190 is regulated by two promoters, only one hpyIM promoter, Pc, has been identified in strain J188. The initiation site of hpyIM transcription is 21 nt upstream of the hpyIM translational start site, and deletion studies indicate that the promoter Pc is located between the −79 and +1 sites.

Both hpyIM::xylE transcriptional fusion and Northern hybridization studies (J. P. Donahue and G. G. Miller, unpublished data) indicate that hpyIM transcription levels are much higher in iceA1 strains (60190 and J166) than in iceA2 strains (J188 and J178). The presence of different hpyIM promoters in these two types of strains could explain such differential hpyIM transcription. However, other factors also may contribute to the difference in hpyIM transcription. For H. pylori strains 26695 (iceA1) and J99 (iceA2), 6 to 7% of the genes are strain specific (1). Trans-acting factors among iceA1 and iceA2 strains may be varied and may regulate hpyIM differently. In addition, variation in mRNA stability may affect hpyIM mRNA levels. The hpyIM transcripts from the Pa and PI promoters in strain 60190 are substantially longer than in strain J188, which may affect mRNA stability.

The H. pylori 26695 genome contains rpoA, rpoB, and rpoD-like genes that separately encode the RNA polymerase α and β subunits and the major ς factor (22). H. pylori possesses ς80 but not ς70, and its RpoD cannot complement an E. coli rpoD mutant (5), suggesting that initiation of RNA transcription is not identical for these organisms. The hpyIM promoters contain −10 hexamers with homology to the E. coli −10 consensus sequence; however, except for the promoter PI, which exhibits a −35 hexamer with similarity to the E. coli −35 consensus sequence, no obvious −35 box was found in the hpyIM promoters. Promoter differences between H. pylori and other bacteria, including E. coli, have been reported (13, 21, 24). New motifs, TTAAGC or TTTTAA, have been proposed to be combined with the −10 hexamer in H. pylori promoters (24). However, TTAAGC was not present in the hpyIM promoters, whereas TTTTAA was found in the promoter Pc.

hpyIM is well conserved (27), and iceA1-hpyIM is a homolog of a CATG-specific type II restriction-modification (R-M) system in N. lactamica. However, due to the presence of mutations, H. pylori iceA1 appears to be degenerate in most strains (11; Q. Xu and M. J. Blaser, unpublished data). These data and its presence in iceA2 strains that lack any nlaIIIR-homologs indicate that hpyIM is not primarily involved in host-specific defense mechanisms. R-M systems in H. pylori are highly diverse among different strains (26). Strong conservation of hpyIM in contrast to the varied R-M systems among H. pylori strains suggests that CATG methylation may be involved in other important cellular processes. DNA methylation is involved in virulence-related function, as shown in studies of the pyelonephritis-associated pili (Pap) operon in E. coli (8) and the fimbriae (Pef) operon in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (18). Expression of Pap and Pef is transcriptionally regulated by methylation of GATC sites in their promoters; the methylation status of these sites controls phase variation, which facilitates bacterial adherence to host tissues, and thus colonization. DNA adenine methylation driven by Dam in serovar Typhimurium has an essential role in bacterial virulence (14). The iceA1 (but not iceA2) strains are significantly associated with high levels of the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin 8 in the gastric mucosa and with peptic ulcer disease in Western populations (19, 23). Whether hpyIM-regulated methylation is involved in virulence-related functions and whether the differing regulation of CATG methylation among iceA1 and iceA2 strains is related to the different clinical outcomes among these strains remain to be determined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. P. Donahue, G. G. Miller, and G. Mosig for useful discussions.

This work was supported in part by the Vanderbilt Cancer Center Core Grant and National Institutes of Health grants RO1 DK53707 and GM63270.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alm R A, Ling L L, Moir D T, King B L, Brown E D, Doig P C, Smith D R, Guild B C, deJonge B L, Carmel G, Tummino P J, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills D M, Ives C, Gibson R, Merberg D, Mills S D, Jiang Q, Taylor D E, Vovis G F, Trust T J. Genomic sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E W, Lipman D J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arber W. Host-controlled restriction and modification of bacteriophage. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1965;19:365–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.19.100165.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barras F, Marinus M G. The great GATC: DNA methylation in E. coli. Trends Genet. 1989;5:138–143. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(89)90054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beier D, Spohn G, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. Functional analysis of the Helicobacter pylori principal sigma subunit of RNA polymerase reveals that the spacer region is important for efficient transcription. Mol Microbiol. 1998;30:121–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg D E, Logan R P H. Helicobacter pylori, individual host specificity and human disease. Bioessays. 1997;19:86–90. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaser M J. Ecology of Helicobacter pylori in the human stomach. J Clin Investig. 1997;100:759–762. doi: 10.1172/JCI119588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braaten B A, Nou X, Kaltenbach L S, Low D A. Methylation patterns in pap regulatory DNA control pyelonephritis-associated pili phase variation in E. coli. Cell. 1994;76:577–588. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90120-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.deHaseth P L, Zupancic M L, Record M T., Jr RNA polymerase-promoter interactions: the comings and goings of RNA polymerase. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3019–3025. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.12.3019-3025.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donahue J P, Peek R M, Jr, Thompson S A, Xu Q, Blaser M J, Miller G G. Analysis of iceA1 transcription in the Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2000;5:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2000.00008.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueiredo C, Quint W G V, Sanna R, Sablon E, Donahue J P, Xu Q, Miller G G, Peek R M, Blaser M J, van Doorn L J. Genetic organization and heterogeneity of the iceA locus of Helicobacter pylori. Gene. 2000;246:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsyth M H, Atherton J C, Blaser M J, Cover T L. Heterogeneity in levels of vacuolating cytotoxin gene (vacA) transcription among Helicobacter pylori strains. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3088–3094. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3088-3094.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forsyth M H, Cover T L. Mutational analysis of the vacA promoter provides insight into gene transcription in Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:2261–2266. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.7.2261-2266.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heithoff D M, Sinsheimer R L, Low D A, Mahan M J. An essential role for DNA adenine methylation in bacterial virulence. Science. 1999;284:967–970. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5416.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishihama A. Molecular assembly and functional modulation of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Adv Biophys. 1990;26:19–31. doi: 10.1016/0065-227x(90)90005-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konyecsni W, Deretic V. Broad-host-range plasmid and M13 bacteriophage-derived vectors for promoter analysis in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Gene. 1988;74:375–386. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90171-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morgan R D, Camp R R, Wilson G G, Xu S Y. Molecular cloning and expression of NlaIII restriction-modification system in E. coli. Gene. 1996;183:215–218. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicholson B, Low D. DNA methylation-dependent regulation of Pef expression in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:728–742. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peek R M, Jr, Donahue J P, Tham K T, Thompson S A, Atherton J C, Blaser M J, Miller G G. Adherence to gastric epithelial cells induces expression of a Helicobacter pylori gene, iceA, that is associated with clinical outcome. Proc Assoc Am Physi. 1998;110:531–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prentki P, Krisch H M. In vitro insertional mutagenesis with a selectable DNA fragment. Gene. 1984;29:303–313. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spohn G, Beier D, Rappuoli R, Scarlato V. Transcriptional analysis of the divergent cagAB genes encoded by the pathogenicity island of Helicobacter pylori. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:361–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5831949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomb J F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney Keith, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adama M D, Hickey E K, Berg D E, Gocayne J D, Utterback T, Peterson J D, Kelley J, Cotton M D, Weidman J M, Fujii C, Bowman C, Watthey L, Wallin E, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Karp P D, Smith H O, Fraser C, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Doorn L J, Figueiredo C, Sanna R, Plaisier A, Schneeberger P, de Boer W A, Quint W. Clinical relevance of the cagA, vacA, and iceA status of Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:58–66. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70365-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanet A, Marsan L, Labigne A, Sagot M F. Inferring regulation elements from a whole genome. An analysis of Helicobacter pylori ς80 family of promoter signals. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:335–353. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woodcock D M, Crowther P J, Doherty J, Jefferson S, Decruz E, Noyer-weiner M, Smith S S, Michael M Z, Graham M W. Quantitative evaluation of E. coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3469–3478. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu Q, Morgan R D, Roberts R J, Blaser M J. Identification of type II restriction and modification systems in Helicobacter pylori reveals their substantial diversity among strains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:9671–9676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Q, Peek R M, Jr, Miller G G, Blaser M J. The Helicobacter pylori genome is modified at CATG by the product of hpyIM. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6807–6815. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.21.6807-6815.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zukowski M M, Gaffney D F, Speck D, Kauffmann M, Findeli A, Lecocq J P. Chromogenic identification of genetic regulation signals in Bacillus subtilis based on expression of a cloned Pseudomonas gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1101–1105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.4.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]