Abstract

Introduction:

Gunshot wounds to the head are more common in military settings. Recently, a damage control (DC) approach for the management of these lesions has been used in combat areas. The aim of this study was to evaluate the results of civilian patients with penetrating gunshot wounds to the head, managed with a strategy of early cranial decompression (ECD) as a DC procedure in a university hospital with few resources for Intensive Care Unit (ICU) neuro-monitoring in Colombia.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty-four patients were operated on according to the DC strategy (<12 hours after injury), over a four-year period. Variables were analyzed and results were evaluated according to the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) at 12 months post injury; a dichotomous variable was established as “favorable” (GOS 4–5), or “unfavorable” (GOS 1–3). A univariate analysis was performed using a Chi2 test.

Results:

Forty (74.1%) of the patients survived and 36 (90%) of them had favorable GOS. Factors associated with adverse outcomes were: Injury Severity Score (ISS) greater than 25, bi-hemispheric involvement, intra-cerebral hematoma on the first CT, closed basal cisterns and non-reactive pupils in the emergency room.

Conclusion:

Damage control for neurotrauma with ECD is an option to improve survival and favorable neurological outcomes 12 months after injury in patients with penetrating traumatic brain injury treated in a university hospital with few resources for ICU neuro-monitoring.

Keywords: gunshot injuries, cranial decompression, damage control, neurotrauma

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a major disease at global level. Incidents have been reported close to 200 cases per 100,000 people worldwide (1). According to the global burden of disease study published in 2010 by the World Health Organization (2–3), trauma remains a public health problem and generates a significant burden of disease in health care systems in Latin American countries. In Colombia, the global burden of injuries particularly affects the male, economically-active population between 12 and 45 years old. In 2013 for example, 26,000 deaths were due to trauma, mostly associated with interpersonal violence. From these injuries, a huge percentage was associated with closed and penetrating TBI (4).

Gunshot wounds are a regular component of the daily practice of surgeons dealing with neurotrauma in several civilian public and private hospitals in Latin America. Most of these wounds are associated to a high mortality rate (5–6). These injuries are also common in military settings; recently, an aggressive approach using damage control (DC) for the management of gunshot wounds has been proposed by military neurosurgeons in combat areas like Iraq and Afghanistan (7).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the results of the management of civilian patients with penetrating gunshot wounds to the head, operated with a strategy of early cranial decompression (ECD) as a DC procedure in a University Hospital with limited resources for advanced neuro-monitoring in Colombia.

Materials and methods

Design

This is a retrospective observational study of patients with severe TBI due to gunshot injuries by firearms, who underwent surgery for an ECD. ECD was defined as a procedure performed in the first 12 hours post trauma, as a DC approach in Neiva University Hospital (NUH) between February of 2009 and February of 2013. Approval from the NUH quality improvement office and the institutional review boards of NUH was obtained prior to conducting this study.

The patient outcomes were evaluated according to the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) at 12 months post-injury. Based on the GOS score, a dichotomous variable “favorable” (GOS 4 or 5), and “unfavorable” (GOS 1–3) was created. Patients were evaluated with the GOS in the outpatient clinic and by phone interview. Classic scale scoring was used (1 Dead, 2 Vegetative state, 3 Severe disability - Able to follow commands/unable to live independently, 4 Moderate disability - Able to live independently, unable to return to work or school, 5 Good recovery - Able to return to work or school) and the dichotomized groups were included in the data collection form for this study.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

Patients wounded in the head by firearms, under the International Classification of Disease (ICD-10) diagnosis codes of TBI were included in the study (S-00 to S-09 and T-00 to T-14). Only patients with intra-cerebral bullets or fragments were included. These patients had to receive an ECD (<12h after trauma) as therapy for DC. Additional criteria include a Glasgow Coma Scale <9, head Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) ≥ 3, and age of 18 years or older.

Early Cranial Decompression Technique.

Early cranial decompression include a >12cm by 12cm hemispheric craniectomy, with or without dural closure, and with or without removal of bullet or fragments. Surgical criteria for the procedure include: obliteration of the basal cisterns, midline shift of >0.5cm, acute subdural hematoma >1cm in width, epidural hematomas of >30cc in volume or intracerebral hemorrhage of >50cc in volume.

Data Collection and Statistical Analysis.

Documentary review of medical records by data recording was performed using an intake form that included epidemiological, clinical, surgical, and outcomes data. The results obtained in the study were analyzed by a statistical software R® version 2.15.2. Measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables were calculated including frequencies and proportions for categorical variables. The Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables, and Pearson Chi-Square test was used for categorical variables.

Results

Fifty-four patients were admitted to NUH with a diagnosis of severe TBI due to gunshot wounds between February of 2009 and February of 2013. Forty (74.1%) of the patients survived and 36 (90%) of them had a favorable neurological outcome at 12 months post-injury. Clinical and socio-demographic characteristics of the population are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical and socio-demographic characteristics of patients with penetrating TBI.

| GOS FAVORABLE n:36 | GOS UNFAVORABLE n:18 | p <0,05 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| ○ Male | 33(92%) | 14(77, 7%) | 0,024 |

| ○ Female | 3(8%) | 4(22, 3%) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| ○ Median ẋ (SD) | 33,5 ±14,20 | 37,1 ±16,05 | 0,035 |

| ○ Range | (18–48) | (22–69) | |

| Glasgow (Admission) | |||

| ○ Median ẋ (SD) | 6,6 ±3,54 | 6,3 ±4,8 | n.s. |

| ISS | |||

| ○ Median ẋ (SD) | 18, 25 ±3,96 | 25,53 ±11,10 | 0, 002 |

Source: Database of Early Cranial Decompression patients Neiva University Hospital. SD = Standard Deviation

Of the patients who underwent ECD therapy as a DC approach, associated factors for unfavorable neurologic outcome were an ISS >25, bi-hemispheric injury, intraventricular hemorrhage, closed basal cisterns and non-reactive pupils on arrival to the emergency department. Findings are presented in Table 2.

Table 2:

Clinical and radiologic findings of patients with penetrating TBI.

| GOS FAVORABLE n:36 | GOS UNFAVORABLE n:18 | p <0,05 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Basal cisterns | |||

| ○ Open | 13(36.1%) | 4(22.3%) | n.s. |

| ○ Closed | 10(27.8%) | 9(50%) | 0.047 |

| ○ Partially open | 13(36.1%) | 5(27.7%) | n.s. |

| Midline shift | |||

| ○ <0.5cm | 23(63.9%) | 4(22%) | n.s. |

| ○ >0.5cm | 13 (36.1%) | 14(78%) | 0.049 |

| Main diagnosis | |||

| ○ Epidural hematoma | 4(11.1%) | 1(5.6%) | n.s. |

| ○ Subdural hematoma | 4(11.1%) | 1(5.6%) | n.s. |

| ○ Subarachnoid hemorrhage | 10(27.8%) | 1(5.6%) | n.s. |

| ○ Intraventricular hemorrhage; | 18(50%) | 15(83.2%) | 0.001 |

| Pupils | |||

| ○ Reactive | 25(69.4%) | 6(33.3%) | |

| ○ No Reactive | 11(30.5%) | 12(66.7%) | 0.001 |

| Result | |||

| ○ Alive | 36(100%) | 4(22%) | |

| ○ Dead | 0(0%) | 14(78%) | |

Source: Database of Early Cranial Decompression patients Neiva University Hospital.

The average length of stay in the ICU for the group of patients with a favorable GOS (4–5) was 12.96 ± 2.67 days, compared to 26.71 ± 5.35 days for those in the unfavorable GOS (1–3) group (p = 0.0002). The average hospital stay overall for the favorable GOS group was 26.60 ± 5.78 days, versus 48.07 ± 12.92 days for the unfavorable GOS group (p = 0.00012).

Post-operative care of all the patients was performed at the ICU and included sedation with midazolam and fentanyl for a mean of 5 days. CT imaging was performed at 24 and 72 hours. Brain swelling was present in 100% of the cases at both time points. Medical management of brain swelling included hyperosmolar therapy with 7.5% saline delivered in a bolus of 150 to 250cc every 6 to 8 hours. A control CT around day 5 was performed in all patients.

Cranioplasty was performed in most of the cases with autologous bone in a mean period between 1 to 3 months after the initial decompression.

Discussion

Management of head injuries due to firearms has been reoriented in recent years. Traditionally, a conservative treatment of these patients was performed because such lesions were characterized by poor prognosis in studies from the early 80s (8). Based on the recent experiences of military neurosurgeons in conflict areas such as the Middle East (particularly Iraq and Afghanistan), where advanced neuro-monitoring for surgical decision-making was not always available, the need for more aggressive surgical management was established. Initially this was focused on a faster craniotomy, hematoma drainage and debridement of necrotic tissue (9). Years later, the term damage control was suggested for the entire approach involving an early cranial decompression to avoid herniation of the remaining brain tissue (10–11). Since then, this strategy has been proposed as an important option to improve survival and reduce disability in closed and penetrating brain injury (12–13). We consider this intervention an important option for low-resource civilian environments. This trend has been confirmed in our study, where we found that of the 54 patients with gunshot wounds to the head, 74.1% survived and 90% of the survivors (36 patients) presented a favorable neurological outcome (GOS 4–5) 12 months after the injury. Our sample includes civilian patients who suffered gunshot wounds inflicted by medium and high-speed weapons and were involved in violent acts in social conflict areas in Colombia (Figure 1).

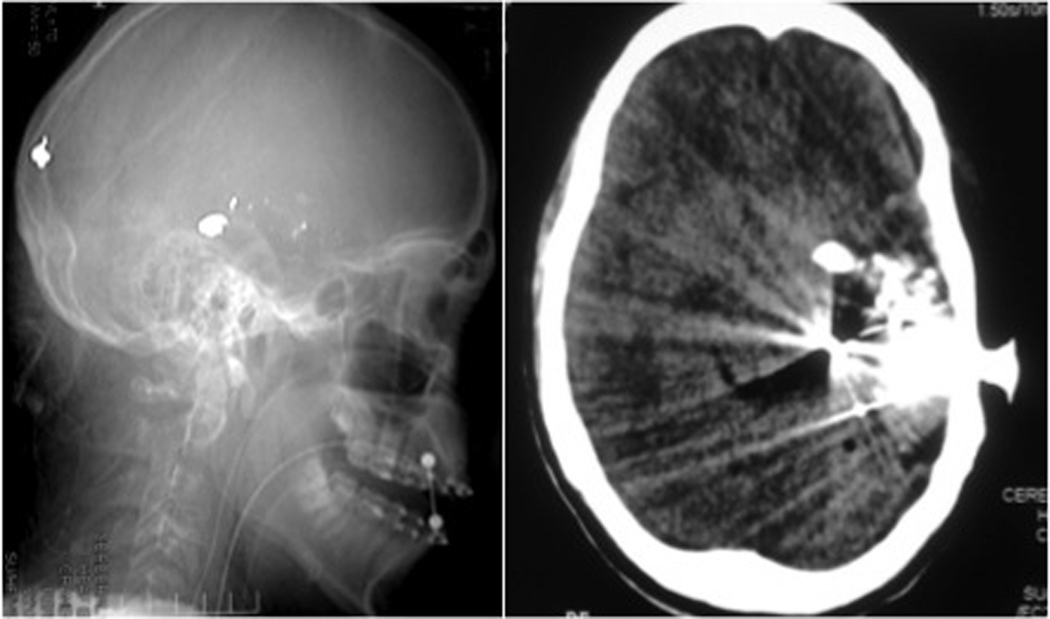

Figure 1.

Cranial X-ray (left) and CT scan (right) of a male patient with a gunshot wound to the head. The temporal and occipital lobes are compromised. (Photo source: Authors).

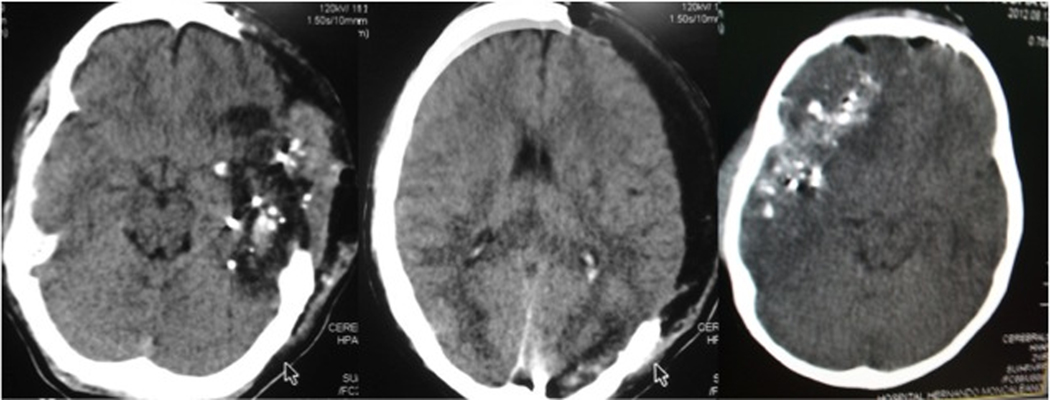

Gunshot wounds are injuries of high morbidity and mortality and have been linked to mortality predictors such as trans-ventricular trajectory, multi-lobe lesions, midline-crossing projectiles, absence of basal cisterns and peri-mesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage (14–15). Several of these factors were also found in our group of patients with an unfavorable neurologic outcome. CT findings of lobar or hemispheric injuries, with open or partially closed basal cisterns, and midline shift of <0.5 cm were associated with a better outcome in patients (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pre- and post-surgical CT imaging of a patient with findings of a favorable outcome. Note the absence of midline involvement and intraventricular hemorrhage. (Photo source: authors)

Intra-ventricular hemorrhage was found on the initial CT in 83.2% of the patients with an unfavorable GOS. A midline shift greater than 0.5 cm was present in 78% of patients with an unfavorable outcome, and compressed basal cisterns were in 50% of these patients. There was no statistically significant difference between admission GCS between the two groups, but the ISS for the favorable GOS group was 18 (SD: 25 ± 3.96), compared to 25 in the unfavorable GOS group (SD = 53 ± 11.10). This indicates that the risk of an adverse neurological outcome is associated with patients sustaining additional systemic injuries, as has been also reported in previous studies (16–17).

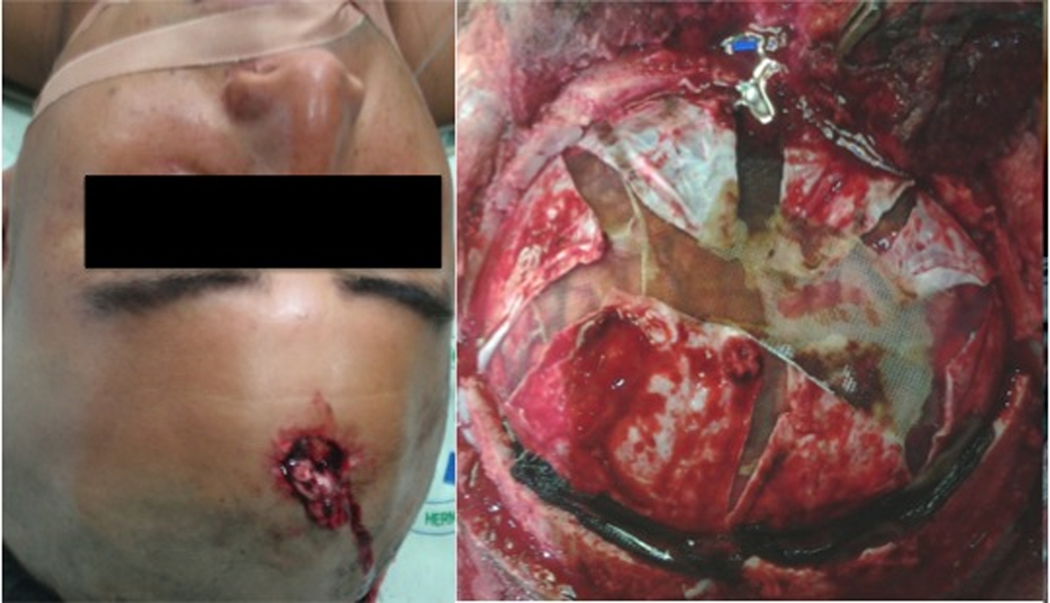

It is critical to note that similar studies involving penetrating gunshot wounds to the head were performed in centers where neuro-monitoring at intensive care units is readily available to support the decision for a secondary decompressive craniectomy (18–19). In our center, without the availability of advanced neuro-monitoring in the ICU, an early primary cranial decompression was performed and the results of this DC procedure show improvement in neurological outcomes in patients without neuro-monitoring before and after the surgical procedure (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Entry zone of a penetrating gunshot injury in a young male patient and an early cranial decompression procedure in a different patient. (Photo source: authors)

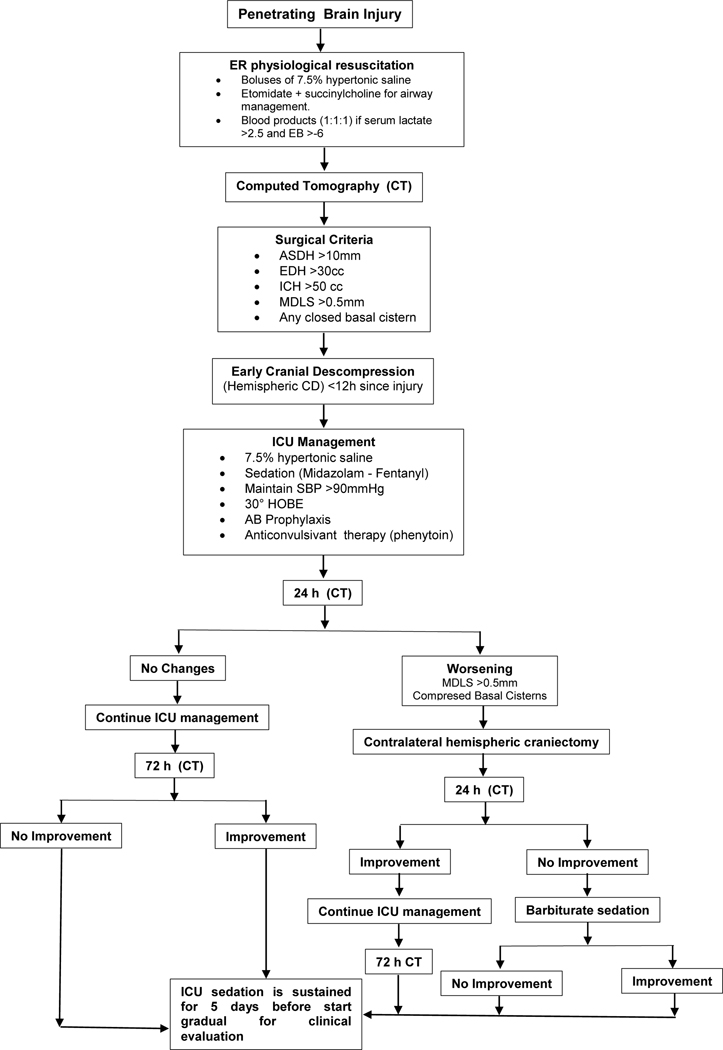

Currently at our institution, the management of patients with penetrating head injury has favored a surgical approach in which the DC decision is based on clinical and CT findings, according to the criteria associated with favorable or unfavorable prognostic factors. In recent published studies conducted in the emergency department at NUH, a positive correlation was found between specific trauma protocols for initial management, based on physiological resuscitation, and increased survival in severe TBI patients (20–21). We are still in the process of analysis in order to understand how these two interventions (medical and surgical) specifically affect the final results of each mechanism of brain injury (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Algorithm for management for penetrating brain injuries at Neiva University Hospital. Advanced neuro-monitoring parameters are not taken into account for surgical or medical decision-making due to limited resources in the ICU ward. Abbreviations: ER: Emergency Room, ASDH: Subdural hematoma, EDH: Epidural hematoma, ICH: Intracerebral hematoma, MDLS: Midline shift, SBP: systolic blood pressure, CD: Cranial Decompression, HOBE: Head of the bed elevation, ICU: Intensive care unit.

Conclusions

Damage control for neurotrauma with an early cranial decompression is an important option to improve survival and favorable neurological outcome in patients with penetrating TBI at 12 months after injury. These results are particularly relevant in the setting of a university hospital with limited resources for ICU neuro-monitoring. In this study, ICU and hospital stay was shorter in the group of patients with a favorable GOS at 12 months post injury. This procedure is of most benefit to patients who did not display midline involvement, intraventricular hemorrhage, or closed basal cisterns in the initial CT.

Acknowledgements

Authors are supported by the NIH-FIC Grant # R21TW009332.

References

- 1.Byass P, de Courten M, Graham WJ, Laflamme L, McCaw-Binns A, et al. (2013) Reflections on the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Estimates. PLoS Medicine 10(7): e1001477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horton R GBD 2010: understanding disease, injury, and risk. Lancet. 2012. Dec 15;380(9859):2053–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norton R, Kobusingye O. Injuries. N Engl J Med. 2013. May 2;368(18):1723–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De la Hoz GA. Comportamiento del homicidio en Colombia, 2013. Forensis, 2013: 79–125. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coughlan MD, Fieggen AG, Semple PL, Peter JC. Craniocerebral gunshot injuries in children. Childs Nerv. Syst. (2003) 19:348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karabagli H Spontaneous movement of bullets in the interhemispheric region. Ped. Neurosurg. (2005). 41:148–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurdjian SE. The treatment of penetrating wounds of the brain sustained in warfare. J. Neurosurgery, 2004; 39:157–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stone JL, Lichtor T, Fitzgerald LF. Gunshot wounds to the head in civilian practice. Neurosurgery. 1995. Dec;37(6):1104–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy ML. Outcome prediction following penetrating craniocerebral injury in a civilian population: aggressive surgical management in patients with admission Glasgow Coma Scale scores of 6 to 15. Neurosurg Focus. 2000. Jan 15;8(1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith JE, Kehoe A, Harrisson SE, Russell R, Midwinter M. Outcome of penetrating intracranial injuries in a military setting. Injury. 2014;45(5):874–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rubiano AM, Villarreal W, Hakim EJ, Aristizabal J, Hakim F, Dìez JC, Peña G, Puyana JC. Early decompressive craniectomy for neurotrauma: an institutional experience.Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009. Jan;15(1):28–38. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell RS, Mossop CM, Dirks MS, Stephens FL, Mulligan L, Ecker R, Neal CJ, Kumar A, Tigno T, Armonda RA. Early decompressive craniectomy for severe penetrating and closed head injury during wartime. Neurosurg Focus. 2010;28(5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouello G, Hamel O, Asehnoune K, Bord E, Robert R, Buffenoir K. Study of the Long-Term Results of Decompressive Craniectomy after Severe Traumatic Brain Injury Based on a Series of 60 Consecutive Cases. The Scientific World Journal Volume 2014, Article ID 207585, 10 pages [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Rubiano AM, Sarmiento FA, Pérez AF: Guías de Manejo Integral del Trauma Craneoencefálico en Areas de Combate y Manejo de Heridas por Proyectil de Arma de Fuego en Cráneo; en: Rubiano AM, Pérez R: Neurotrauma y Neurointensivismo. 1ª Ed. Editorial Distribuna. Bogotá; 2007. pp 231 – 244. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackeric Z, Gal P. Unusual penetrating head injury in children: personal experience and review of literature. Childs Nervous System (2009) 25: 909– 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aarabi B Management of Missile Head Wounds. Neurosurgery Quarterly (2003) 13(2):87–104 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grahm T, Williams F, Harrington T, Spetzler R 1990. Civilian gunshot wounds to the head: A prospective study. Neurosurgery 27: 696–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zafonte RD, Wood DL, Harrison-Felix CL ,Millis SR, Valena NV. Severe Penetrating head Injury: A study of outcomes.Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001. 82(3): 306–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdolvahabi RM, Dutcher SA, Wellwood JM, Michael DB. Craniocerebral missile injuries. Neurol Res 2001; 23: 210–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kesinger MR, Puyana JC, Rubiano AM. Improving trauma care in low- and middle-income countries by implementing a standardized trauma protocol. World J Surg 2014. Aug; 38(8):1869–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kesinger MR, Nagy LR, Sequeira DJ, Charry JD, Puyana JC, Rubiano AM A standardized trauma care protocol decreased in-hospital mortality of patients with severe traumatic brain injury at a teaching hospital in a middle-income country. Injury. 2014. Sep; 45(9):1350–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]