Abstract

The main goal of the article is to examine the tracking efficiency of a homogenous sample of 14 ETFs listed on European exchanges, replicating the performance of Euro Stoxx 50 Index—a benchmark index for blue chips from the euro area. This study provides some insights into the tracking quality of European ETFs over the long time horizon (2012–2021 period) including data from entire business cycle: both economic prosperity and COVID-19 crisis. The study has been made applying different tracking error calculation techniques and return intervals—daily, weekly and monthly. Passive investing may be a highly desirable, cheap and accurate method for long or short term investments in the largest 50 cap companies in the euro zone. Hence, this unique research may help to succeed in ETF selection process. The study reveals that ETFs are very effectively managed by keeping the TEs below 0.3% (for ETFs with accumulating share classes) and below 1% (for ETFs with distributing share classes). This shows that the ETFs with accumulating share classes perform much better—the average TE for three different methods is 0.11% for accumulating share classes ETFs and 0.33% for distributing share classes ETFs. It proofs, that it is not important whether to use the standard deviation of the difference between the return of an ETF and that of its benchmark index, or the standard error of regression in TE assessment, both methods give very similar results. However, TE calculation method signifies, if the average of the absolute difference between the return of an ETF and that of the index is used. Additionally, it is found that time intervals used in TE calculations matter—the shift from monthly to daily intervals results in reduction of TE levels. Using shorter intervals brings lower TE values of European ETFs.

Keywords: Exchange-traded funds (ETFs), Euro Stoxx 50 Index, Tracking efficiency, Tracking error

Introduction

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have been one of the most important innovations on financial markets over the last three decades (Charupat and Miu, 2013). They are usually open-ended funds, the shares of which are publicly traded on stock exchanges or other trading platforms (such as multilateral trading facilities). Most of them are passively managed, i.e. designed to closely track the performance and risk characteristics of diverse financial indices such as equity, fixed income, currency, commodity, alternative as well as multi-asset indices. In order to mirror the return of an index (which is not investible) as closely as possible, they use physical (direct) or synthetic (swap) replication methods.

Since the launch of first ETFs in the early 1990s, they have fundamentally changed the manner in which both institutional investors and retail investors construct their investment portfolios. Interestingly, even though ETFs are commonly treated as financial instruments that enable passive investing, most of them are active investments in form (designed to generate alpha) or function (serve as building blocks of active portfolios) (Easley et al. 2021). Over the last two decades, especially since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), global ETF market has grown dramatically. According to ETFGI data, at the end of December 2021 assets invested in 8553 exchange-traded funds reached the record level of USD 10.0 trillion. These instruments, together with 1324 other exchange-traded products (ETPs), are listed on 79 exchanges and trading platforms in 62 countries worldwide (ETFGI, 2022a). ETFs have become very popular, widely recognized and broadly applied investment vehicles as they offer many advantages to various investor groups, enabling them to achieve different goals. ETFs combine positive aspects of closed-ended and open-ended investment funds, hence they are increasingly gaining favor on global financial markets; foreign institutional investors, in particular, use ETFs to obtain exposure to all financial markets worldwide. As predicted by PwC (2022) global ETF market set to top USD 20 trillion by 2026 representing a 17% CAGR over the next five years.

First ETFs were launched on Toronto Stock Exchange (TSX) in 1990 (Toronto Stock Exchange Index Participation, TIPs) and on American Stock Exchange (AMEX) in 1993 (Standard & Poor’s Depositary Receipts, SPDR). In the following years, these financial instruments also debuted, among others, on stock exchanges in the Pacific region (on New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZX) in 1996 (NZ Top 10, TNZ)) (Chen, et al. 2017), and in Asia (on Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKEX)) in 1999 (Tracker Fund of Hong Kong) (Chu 2011)1. All the above-mentioned ETFs were designed to replicate the return of the main index in a given country. Typically, they were the instruments linked to the blue-chip index, comprising the largest and the most liquid shares.

This was also the case of the European financial market, where the first ETFs were launched in April 2000—almost simultaneously—on Deutsche Boerse (Euro Stoxx 50 LDRS and Stoxx 50 LDRS2) and on London Stock Exchange (LSE) (iShares FTSE 100) (Groves 2011)3. As regards both ETFs launched on Deutsche Boerse, first funds—unlike most other pioneering ETFs on a given market—sought to track regional equity indices, which offered exposure to 50 biggest public companies selected from euro area and European countries, respectively. Although in subsequent years a variety of single-country equity ETFs appeared on the European market (with exposure to broad market, large-cap, mid-cap and small-cap stocks, sectors, themes and specific factors—e.g. dividends, momentum, value), funds based on regional indices are still one of the most important (taking into account assets under management (AuM)) equity ETFs in Europe (Miziołek et al. 2020)4.

This applies in particular to the funds that aim to reflect the performance of indices whose portfolios include companies from countries belonging to the euro area. Since the most recognized benchmark of this segment of the European equity market is the Euro Stoxx 50 Index, many asset managers use this index as a flagship benchmark for their actively managed funds and other investment products, or as a reference index for index funds and ETFs. Given the fact that the European ETF market is highly fragmented and many asset managers cannot afford not to offer funds based on this benchmark, ETFs replicating return of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index are one of the most popular regional equity ETFs in Europe—among the 10 ETFs with European exposure with the largest AuM, as many as four strive to follow the performance of this index.

The main aim of the article is to examine the quality of replication within a homogenous sample of 14 exchange-traded funds tracking the performance of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index. These ETFs are listed on European stock exchanges, offer accumulating or distributing share classes and were launched in 2012 or earlier. The research uses most widely recognized measure used to assess an index replication quality—tracking error.

Although it is not the first study in which tracking efficiency of ETFs based on the Euro Stoxx 50 Index has been examined, it aims to contribute to existing literature in many ways. Firstly, we have explored tracking errors using three calculation techniques and three time intervals, while earlier studies were generally based on one or two time intervals only. Secondly, we have analyzed separately funds (share classes) capitalizing dividends and funds distributing dividends. Thirdly, we have checked whether the calculation method affects the level of tracking error. Lastly, we have examined all ETFs within the research sample over the same, long time horizon (10 years).

The primary findings of this paper can be summarized as follows. Exchange-traded funds listed on European exchanges, which replicate the performance of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index, are characterized by a very good tracking ability in long term. ETFs with accumulating and distributing share classes kept tracking errors below 0.3 and 1%, respectively. Tracking error results turned out to be generally very similar regardless of applied calculation methods (except for the method using the average of the absolute difference between the return of an ETF and that of the index) and time intervals. This results could be valuable for all market participants, not only European investors but all sort of financial analysts and researchers all over the world.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. The next section presents a review of the related literature. Subsequently, we outline the Euro Stoxx 50 Index and research sample (along with descriptive statistics presented in the three tables in Appendix). In the next sections, we describe research methods, results of the study and the main findings. Finally, we draw conclusions from the presented research.

Literature review

The mainstream of exchange-traded funds research includes three areas: the replication quality of ETFs, effectiveness of their stock market valuations in relation to the net asset value (NAV), and impact of ETF transactions on securities related to them and index derivatives. The main purpose of the vast majority of ETFs is to replicate the performance of the index (excluding management costs), therefore the research made in this area generally involves a comparison of the investment performance of the ETF with the index replicated by the ETF and determining the variability of differences in the rates of return between the ETF and the index it reflects. Within this research, some standard analyses are made for actively managed investment funds, using risk-adjusted performance measures.

The research connected with the index replication quality of ETFs has been conducted for about twenty years. Initially, it focused almost exclusively on the funds listed on American stock exchanges replicating indices of the domestic stock market. It was justified by the fact that the American ETFs market was the best-developed one, while in other regions of the world ETF markets were either relatively small and underdeveloped.

The first research concerned a small number of ETFs and encompassed a relatively short period. Elton et al. (2002) examined the performance of first American ETFs—Standard and Poor`s Depositary Receipts (SPDRs), listed on the American Stock Exchange (AMEX) in the period of 1993–1998. They found that the NAV return of SPDR ETF replicating the S&P 500 Index underperformed benchmark by 28.4 basis points (bps) per year and SPDR ETF tracking CRSP value-weighted S&P 500 Index underperformed by 40 bps. This underperformance was due to the difference between the NAV return without dividends and the S&P return without dividends and the effect of management expenses, as well as the lack of dividend reinvestment. Poterba and Shoven (2002) also analysed SPDR S&P 500 Trust, comparing its returns (pre-tax and after-tax) with returns of the largest equity index mutual fund—Vanguard 500 Index Fund (retail shares) and the S&P 500 Index from 1993 to 2000. The results proved that the total pre-tax return for ETF was 16–17 bps below the return of the Vanguard fund and it underperformed the S&P 500 benchmark by 22–23 bps. Reasons for this underperformance were consistent with the conclusions of Elton et al. Subsequent research exclusively on US ETFs was carried out, among others, by Shin and Soydemir (2010), and Qadan and Yagil (2012).

With development of ETF markets in other regions, there was commenced research on tracking efficiency of equity exchange-traded funds listed in other developed countries. Gallagher and Segara (2006) investigated ETFs listed on the ASX and replicating main Australian equity indices, Rompotis (2008) and (2012) examined the tracking efficiency of ETFs listed in Germany, Chen et al. (2017) studied replication quality of New Zealand ETFs. In recent years, research on emerging markets equity ETFs (with regional and single exposure) has been carried out with increasing frequency. For example, Blitz and Huij (2012) examined ETFs listed on US and European exchanges with exposure to two conventional broad EM indices (the MSCI Emerging Market Index and the S&P EM BMI Index). Johnson et al. (2013) investigated, among others, the tracking ability of 8 European ETFs that aim to mirror the performance of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Khan et al. (2015) examined emerging markets ETFs listed on the NYSE, mainly with single country and regional exposure. Baş and Sarıoğlu (2015) evaluated tracking errors for ETFs listed on the Borsa Istanbul and investing mainly in domestic equities. Miziołek and Feder-Sempach (2019) analysed tracking quality of European ETFs replicating the performance of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index. Diaw (2019) investigated tracking ability of domestic Saudi Arabian ETFs listed on the Tadawul Stock Exchange. Kok-Leyong et al. (2021) examined quality replication of iShares ETFs with exposure on Asia-Pacific equity markets, including emerging ones.

Among the studies on developed markets, some relate to ETFs that have exposure to the European equity market (and usually listed on European exchanges)—both with regional exposure and with single-country exposure. Due to the subject and purpose of this paper, only results and conclusions from selected articles that explore the issue of ETFs replicating the Euro Stoxx 50 Index, will be discussed.

Milonas and Rompotis (2006) examined the performance of 36 equity and fixed income ETFs tracking various European, US and Asian indices and listed on SIX Swiss Exchange in the period of 2001–2006 (including also four ETFs that did not survive). It is noteworthy that the study analysed for the first time, probably, such a wide range of results of ETFs tracking the return of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index. Surprisingly, five funds of that kind, on average, slightly overperformed the underlying index by 0.4 bps, although for the whole sample the average daily percentage return of ETFs was 4 bps lower than the return of corresponding indices. The study also revealed that all examined ETFs—due to the fact that they did not adopt full replication methods—had a relatively high tracking error (the mean tracking error of the three applied types was equal to 1.02%). Meanwhile, the average tracking error for five Euro Stoxx 50 ETFs was much smaller and amounted to 0.76% (ranging from 0.48 to 1.06%).

Hassine and Roncalli (2013) studied the performance of 31 ETFs tracking five benchmarks: S&P 500, Euro Stoxx 50 (6 funds: Amundi, db x-trackers, iShares (DE), iShares, Lyxor and Source), MSCI World, MSCI Emerging Markets and MSCI Japan/Topix from November 2011 to November 2012. They developed own tracker efficiency measure ζα. It is a value-at-risk measure, based on the three parameters: the performance difference between the fund and the index, the volatility of the tracking error and the liquidity spread. They found a positive value of efficiency measure for four out of six examined ETFs replicating returns of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index, probably due to fiscal optimization of dividends. The average value of ζα amounted to 8.93 bps, ranging from 41.64 to − 63.38 bps. They also calculated semi-volatility of the tracking error for Euro Stoxx 50 ETFs and noticed that the ranking of funds had changed slightly in comparison to the previous one. Besides, they developed an efficiency measure, based on the assumption that tracking errors were not normally distributed (with five risk measures), and observed only minor differences in relation to the first method.

Johnson et al. (2013) examined tracking efficiency of 65 ETFs that aim to mirror country benchmarks (S&P 500, FTSE 100, DAX, MSCI Japan, MSCI Brazil), regional indices (Euro Stoxx 50, MSCI Emerging Markets) and the MSCI World index. For all these funds, they measured tracking differences and tracking errors in different intervals and compared differences between ETFs using physical and synthetic replication. In the case of 12 funds (managed by 11 asset managers) replicating the Euro Stoxx 50 Index performance, an average daily tracking error in the period of 2010–2012 was 0.21% (0.12% for synthetic ETFs, 0.27% for physical ETFs), while an average weekly tracking error was 0.21%. They found that tracking errors for these ETFs were relatively high (in comparison to other ETFs linked to indices from developed markets), in part due to the use of enhancement techniques, which led many of these funds to outperform their benchmarks. Moreover, they estimated the rolling one-year tracking error for 5 ETFs over a longer period (2006–2012), concluding that the tracking error tended to increase during the GFC in early 2009. In turn, the average tracking difference for all 12 Euro Stoxx 50 ETFs amounted to 0.47% (in the period of 2010–2012). Similarly to tracking errors, the average value of tracking difference was considerably higher for physical ETFs (0.55%) than in synthetic ETFs (0.36%), as the latter benefited from dividend tax optimization and securities lending.

Yiannaki (2015) analysed performance of 24 equity ETFs in the period of 2008–2014, domiciled in two main European hubs (12 in Luxembourg and 12 in Ireland) and listed on three major European exchanges (London Stock Exchange, Euronext Paris, Deutsche Boerse), which track the same indices, including two ETFs replicating the Euro Stoxx 50 Index (iShares (EUE) and db x-trackers (DBXE)). Tracking errors for these two funds did not differ considerably from each other, although their values turned out to be relatively high over an annual, three-year and the entire examined period; they amounted, respectively, to 1.78% and 1.63%, 1.59% and 1.50%, and 2.65% and 2.99%.

It should be added that in the literature ETFs tracking returns of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index are compared not only against this benchmark, but also against the performance of index funds and Euro Stoxx 50 futures contracts (Madhavan et al. 2015).

Euro Stoxx 50 Index

Euro Stoxx 50 Index is one of the most popular indices of the European stock market. It is the most widespread index reflecting prices of European blue chip companies, i.e. the largest (taking into account free float market capitalization) and the most liquid (i.e. characterized by the highest stock exchange turnover) companies from 9 countries of the European Economic and Monetary Union5. The portfolio of Euro Stoxx 50 Index includes 50 companies classified into 20 supersectors, whose total market capitalization was 4,175.1 billion euros at the end of December 2021 (free float market capitalization—3,241.0 billion euros) and accounted for approximately 60% of the free-float market cap of the Euro Stoxx Total Market Index (TMI), comprising nearly 800 companies with large, medium and small capitalization from the euro zone (Qontigo 2022a).

The Euro Stoxx 50 Index was launched by the STOXX Limited6 in February 1998, though its base date was December 31, 1991, when its value was set at 100 points. It is calculated in different versions: as regards the way in which company income is taken into account and how the company's dividend is taxed (price, gross return, net return), as well as depending on the currency (EUR, USD, CAD, GBP, AUD, CHF and JPY). The composition of the index is revised once a year in September and in order to ensure diversification of the portfolio, the maximum weight of its participants is limited to 10% (the level is adjusted during the quarterly adjustment of the index) (Qontigo 2022b). At the end of December 2021, the largest part of the index portfolio constituted French (37.3%), German (31.6%), Dutch (16.4%) and Spanish (5.5%) companies. The largest constituents were: ASML (9.01%), LVMH Moet Hennessy (5.91%), Linde (4.82%), SAP (4.21%), and TotalEnergies (3.64%). The index portfolio is dominated by companies from technology (16.8%), industrial goods and services (14.4%), consumer products and services (13.8%), and chemicals (8.8%) supersectors (Qontigo 2022a).

On the basis of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index, many subindices or derived indices have been created, for example those excluding from their portfolio the stocks from specific sectors (e.g. Euro Stoxx 50 ex-Financials, Euro Stoxx 50 ex-Banks) or selected countries (e.g. Euro Stoxx 50 ex-France, Italy, Germany, Spain, Netherlands), and covering only shares of companies from a specific country (e.g. Euro Stoxx 50 France, Italy, Germany, Netherlands, Spain). In addition, there are strategy indices including short indices (e.g. Euro Stoxx 50 Daily Short indices with factors -1, -2, -3, -4, -5, -6, -7 and -8) and the leveraged indices (e.g. Euro Stoxx 50 Daily Leverage indices with factors of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and 8)7, as well as thematic indices (e.g. Euro Stoxx 50 ESG, Euro Stoxx 50 Low Carbon).

The Euro Stoxx 50 Index is licensed by many financial institutions, which use it to provide a variety of investment products, particularly ETFs, as well as exchange-traded notes (ETNs), futures contracts, options and structured products8. In December 2021, this index was fundamental to the functioning of more than 40 financial instruments, mainly listed on European stock exchanges, but also on US (NYSE Arca), APAC (Korea SE, Taiwan SE, ASX), African (Johannesburg SE) exchanges and multilateral trading platforms (Qontigo 2022c). The Euro Stoxx 50 Index is also a benchmark for many actively managed investment funds with exposure to the euro zone equity market.

Research sample

Out of the 1928 ETFs listed on European stock exchanges at the end of December 2021 (ETFGI 2022b), 20 funds aim to replicate the return of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index. Issuers of these ETFs are 10 separate financial institutions. Funds are registered in Ireland, Luxembourg, France, Germany and Spain. Their shares are listed—as a primary listing—on the stock exchanges in Paris (Euronext Paris), Frankfurt (Deutsche Boerse—Xetra), London (London Stock Exchange), Zurich (SIX Swiss Exchange) and Madrid (Bolsa de Madrid). In addition, they are also cross-listed in Milan (Borsa Italiana), Amsterdam (Euronext Amsterdam), Vienna (Wiener Boerse) and Stuttgart (Boerse Stuttgart), and on the multilateral trading facility BATS Chi-X Europe9.

The research sample includes 14 ETFs` share classes that have been functioning for at least 10 years10 and trying to replicate the Euro Stoxx 50 Total Return Net (TRN) Index. They are divided into two panels. Panel A includes five funds (share classes) that accumulate income and reinvest it (their shares are usually marked as A, C or Acc). Panel B covers nine funds (share classes) that periodically distribute income (their shares are usually designated as D or Dis). An overview of the sample is presented in Appendix in Table 2.

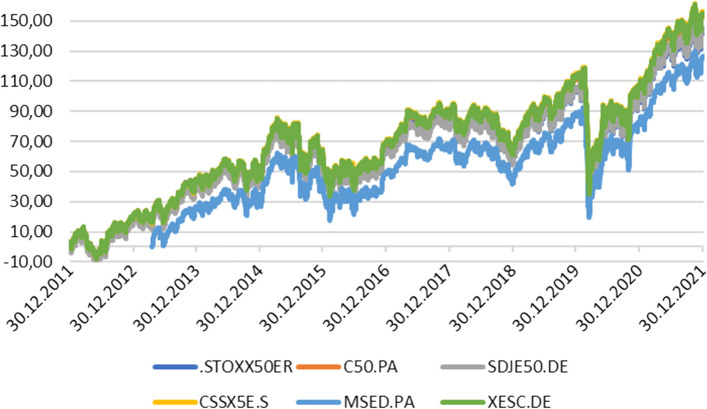

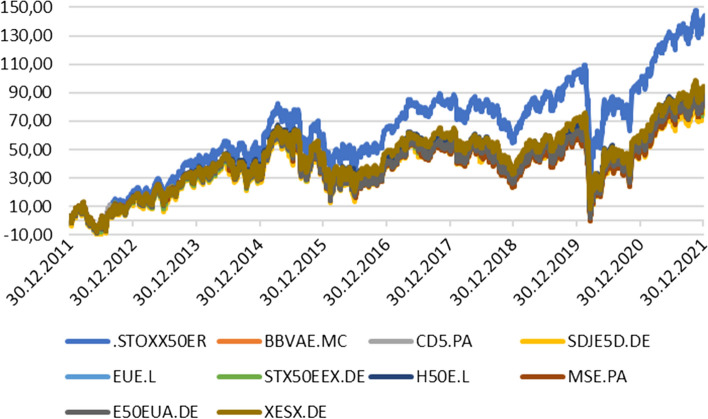

All ETFs’ net asset values (NAVs) were referenced to the Euro Stoxx 50 Total Return Net (TRN) Index, calculated in euro currency (see Appendix Figure 1 and 2)11. This choice was dictated by the desire to achieve the highest possible comparability of the analyzed data. NAVs for all the examined ETFs and closing values of the Euro Stoxx 50 TRN Index were collected from the Refinitiv EIKON Database. All funds in the sample have continuous data availability over the study period. As regards time intervals, we used 2547 observations (daily returns), 525 observations (weekly returns) and 121 observations (monthly returns). Descriptive statistics of time series are in Appendix in Tables 3, 4 and 512.

Figure 1.

Evolution of Euro Stoxx 50 Index closing values and ETFs NAVs per share from Panel A scaled to 100 at the beginning of the sample

Figure 2.

Evolution of Euro Stoxx 50 Index closing values and ETFs NAVs per share from Panel B scaled to 100 at the beginning of the sample

Research methods

Passively managed exchange-traded funds are designed to track the performance of the underlying index as closely as possible, yet in practice their returns differ from the returns of their benchmarks due to market frictions occurring while mirroring the performance of target indices. One of the basic measure used to determine the quality of index replication by passively managed funds is tracking error.

Tracking error (TE) denotes volatility of differential returns between the fund and the underlying index. Tracking error in the fund performance can be decomposed into two elements—an endogenous component arising from a fund’s replication of the underlying index and an exogenous component that stems from given changes in the constituents of the underlying index. The main factors affecting a tracking error comprise asset size, management fees, cash drag, securities lending, earnings on dividends (‘dividend effect’), foreign/domestic exchange-traded funds, index composition changes and the volatility of the benchmark (Frino et. al. 2004).

The literature presents different techniques of calculating tracking error (Roll 1992; Pope and Yadav 1994). In this article, we have used three of them, most commonly applied in practice.

According to the first method, TE is the standard deviation of the difference between the return of the fund and that of its benchmark index. The equation below represents the estimation of the tracking error 1 (TE1):

where TE1—tracking error calculated with first method, —average tracking difference.

Tracking difference depicts the difference in performance between respective ETF and the underlying index. It is calculated as the difference of return of the fund and return of its benchmark return over a specific period of time. Therefore, we calculated tracking difference (TD) using below formula:

where TDi,t—fund i tracking difference in t period, Ri,t—fund i return in t period, RINDEX,t—benchmark return in t period.

According to the literature, we calculated logarithmic rates of return using, respectively, net asset values (NAVs) of ETFs and the closing values of Euro Stoxx 50 TRN Index. The calculation of fund return is stated below:

Ri,t—fund i logarithmic return in t period, Pi,t—fund i NAV in t period, Pi,t-1—fund i NAV in t-1 period.

Similarly, the equation to calculate index return is:

where RINDEX,t—index logarithmic return in t period, PINDEX,t—closing value of index in t period, PINDEX,t-1—closing value of index in t-1 period.

The second method estimates the tracking error by taking the absolute value of the difference between the fund and benchmark returns. The equation below illustrates this estimation:

TE2—tracking error calculated with second method.

The third method uses the standard error of regression from the equation below as the tracking error.

where αi—alfa coefficient (excess return), βi—beta coefficient (systematic risk of the fund), εi—regression residuals, TE3—tracking error calculated with the third method.

The tracking error TE3 is equal to the standard deviation of residuals εi,t.

Results

Table 1 presents the estimates for tracking errors calculated with three different methods (TE1, TE2, TE3) in three different intervals (daily, weekly and monthly). The lowest TE values in each column are marked in bold, and the highest are marked in italics, separately for Panel A and Panel B.

Table 1.

Tracking errors calculated using three different methods in 2012–2021 (%).

Source: own calculations.

| ETF | TE1 | TE2 | TE3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | Weekly | Monthly | Daily | Weekly | Monthly | Daily | Weekly | Monthly | |

| Panel A | |||||||||

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (C) (C50.PA) | 0.0317 | 0.1082 | 0.2861 | 0.0064 | 0.0200 | 0.0769 | 0.0317 | 0.1082 | 0.2852 |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Acc (SDJ50.DE) | 0.0562 | 0.0832 | 0.1623 | 0.0062 | 0.0192 | 0.0758 | 0.0562 | 0.0832 | 0.1629 |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Acc) ( CSSX5E.S) | 0.1567 | 0.1294 | 0.2441 | 0.0304 | 0.0312 | 0,1126 | 0.1554 | 0.1293 | 0.2450 |

| Lyxor Core EURO STOXX 50 (DR) - UCITS ETF Acc (MSED.PA) | 0.0518 | 0.0766 | 0.1146 | 0.0083 | 0.0226 | 0.0670 | 0.0517 | 0.0767 | 0.1151 |

| Xtrackers EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF 1C (XESC.DE) | 0.2076 | 0.1205 | 0.2591 | 0.0312 | 0.0334 | 0.1245 | 0.2044 | 0.1206 | 0.2600 |

| Panel B | |||||||||

| AcciónEurostoxx 50 ETF (BBVAE.MC) | 0.1913 | 0.4466 | 0.7278 | 0.0318 | 0.1243 | 0.3306 | 0.1910 | 0.4471 | 0.7306 |

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (D) (CD5.PA) | 0.1998 | 0.4469 | 0.9286 | 0.0190 | 0.0800 | 0.3339 | 0.1998 | 0.4473 | 0.9264 |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Dist (SDJE5D.DE) | 0.1725 | 0.3692 | 0.7400 | 0.0178 | 0.0800 | 0.3246 | 0.1725 | 0.3695 | 0.7420 |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Dist) (EUE.L) | 0.1835 | 0.2883 | 0.5547 | 0.0328 | 0.0786 | 0.2941 | 0.1831 | 0.2885 | 0.5570 |

| iShares EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (DE) (STX50EEX.DE) | 0.1389 | 0.2963 | 0.5713 | 0.0309 | 0.0978 | 0.3542 | 0.1387 | 0.2963 | 0.5736 |

| HSBC EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (H50E.L) | 0.2100 | 0.3455 | 0.7168 | 0.0373 | 0.0784 | 0.3439 | 0.2093 | 0.3456 | 0.7194 |

| Lyxor EURO STOXX 50 (DR) UCITS ETF – Dist (MSE.PA) | 0.1904 | 0.4101 | 0.8171 | 0.0190 | 0.0791 | 0.2982 | 0.1904 | 0.4105 | 0.8169 |

| UBS ETF (LU) Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF (EUR) A-dis (E50EUA.DE) | 0.2555 | 0.3624 | 0.7380 | 0.0372 | 0.0851 | 0.3152 | 0.2530 | 0.3625 | 0.7324 |

| Xtrackers Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF 1D (XESX.DE) | 0.2768 | 0.4205 | 0.8541 | 0.0416 | 0.0850 | 0.3358 | 0.2740 | 0.4209 | 0.8520 |

The exhibit reports the results of the examination of ETFs` tracking errors. TE1 is the standard deviation of the difference between the return of the fund and that of its benchmark index.TE2 is the absolute value of the difference between fund and benchmark returns.TE3 –TE is the standard error of regression. Results for Lyxor EURO STOXX 50 (DR) UCITS ETF—since April 18, 2013.

The results indicate that all examined exchange-traded funds replicating performance of the Euro Stoxx 50 TRN Index are basically able to very precisely track the underlying index by keeping the TEs below 0.3% in Panel A. What is more, in over a half of the cases (51%) the TEs were below 0.1%, and in 27% the TEs were even below 0.05%. As far as Panel B is concerned, the results are weaker—the TEs were below 1%. In 77% of the TEs, the results were even below 0.5%, yet it is still a lot compared to those from Panel A: only in about one-third of them, the results were below 0.2%. This shows that the ETFs with accumulating share classes track the underlying index much better than the ETFs with distributing share classes. The average TE for all ETFs using three different methods is 0.25%, with 0.11% for Panel A and 0.33% for Panel B. The median TE for all ETFs using three different methods is 0.19%, with 0.08% for Panel A and 0.30% for Panel B. ETFs with accumulating share classes performed much better mainly because of the fact that they systematically reinvest the income generated by the fund (portfolio constituents).

These results appear to be generally consistent with the results obtained by Johnson et al. (2013). However, TEs turned out to be smaller than in the study of Milonas and Rompotis (2006)—where an average TE was 1.02%—and in the Yiannaki research (2015) in particular. In the latter case, this might be a consequence of adopting a different sample period (2008–2014), which matters for two reasons. Firstly, this period covered the time of a relatively high volatility on European equity markets. This is confirmed, for example, by Johnson et al. (2013) research results, which show that the tracking error did tend to increase during the GFC, reaching its nadir in early 2009. Secondly, in recent years many ETFs providers, faced with growing market competition, have decided to reduce management fees, which are the main factor affecting the quality of index replication. For example, total expense ratios (TERs) in 2013–2021 for iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF dropped from 0.20 to 0.10% and for Lyxor Euro Stoxx 50 (DR) UCITS ETF dropped from 0.20 to 0.07%.

If we investigate the results separately for the two panels, the highest values of the TEs are usually obtained for monthly data and the lowest for daily data in Panel A. The average value of the TE in daily, weekly and monthly intervals is 0.07, 0.08, and 0.17%, respectively. It could be explained by the fact that daily data cover more information (including outliers) and for weekly and monthly some information is missing, and as a result TE is higher. The growth in tracking errors, when shifting from daily performance data to weekly data, is contrary to the research by Lin and Mackintosh (2010), BlackRock (2012) and Johnson et al. (2013). It seems to look exactly the same when we examine the results for Panel B. The highest values of TEs are usually obtained for monthly data and the lowest for daily data. The average value of TEs in daily interval is 0.14%, 0.28% in weekly interval and 0.60% in monthly interval.

Interestingly, TEs achieved very similar values when using first and third calculation methods in both panels. It can therefore be concluded that it is not important whether one can use the standard deviation of the difference between the return of an ETF and that of its benchmark index, or the standard error of regression. It means that the first TE calculation method (variability of the difference in the ETF return and the underlying index return) is simply the same as the third one, when regressing the return of the ETF on the return of the underlying index. The results obtained using second method—the average of the absolute difference between the return of an ETF and that of the index—are usually much lower than in the first and third method, but the story between the numbers remains the same. Apparently it is important whether one can use first or third TE calculation method interchangeably or second, which provides different results.

Conclusions

In this study, we have estimated tracking errors for 14 equity ETFs (share classes), listed on European exchanges, which replicate the performance of the Euro Stoxx 50 TRN Index over the period of 2012–2021. The sample was divided into Panel A (five ETFs that accumulate income) and Panel B (nine ETFs that distribute income). We found that the funds were managed very effectively as regards limiting TEs. All studied ETFs from Panel A kept tracking errors below 0.3% and those from Panel B—below 1%, counted with three calculation methods and in different time intervals. Taking this into account, it can be stated that the ETFs successfully fulfill their main investment goal, which is to closely mimic the return of the benchmark index with minimal performance leakage and tracking error. We have to emphasize that the ETFs with accumulating share classes have performed much better—the average TE for three different methods is 0.11% for Panel A ETFs and 0.33% for Panel B ETFs.

The result was expected, as the researched ETFs are the funds with unique characteristics, allowing them to accurately match the performance of the Euro Stoxx 50 TRN Index. First of all, their management fees are significantly lower compared to other equity ETFs. Average TER in the funds from the research sample at the end of analyzing period was 10.7 bps; meanwhile, according to ETFGI (2020), asset-weighed TER for equity ETFs listed globally was 19 bps in September 2020. This results, on the one hand, from a massive competition among ETFs replicating the most popular equity benchmark for large caps in the euro area. On the other hand, low costs are an outcome of a great interest on the part of investors (which is reflected in very high assets under management in most of them)13, which makes it possible to take advantage of economies of scale. Secondly, almost all examined ETFs presently use the method of full physical (direct) replication, which significantly limits the possibility of differences between the fund’s and the underlying index returns. Moreover, the funds with blue chip shares in their portfolios may lend them to other investors, and the earned income may reduce errors in replicating the target index14. Finally, very low levels of TEs may result from the benchmark selection. As Johnson et al. (2013) points out, the net return version of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index assumes certain withholding taxes on the dividends paid by companies from the index. Meanwhile, many ETFs using direct replication by virtue of their country of domicile and double tax treaties, can obtain lower withholding tax rates than those assumed by the Euro Stoxx 50 Index. Securities lending and tax optimization also enable to achieve higher returns for some ETFs than the benchmark return.

It is noteworthy, however, that the tracking error can vary considerably over time and it is sensitive to the time horizon selected for calculations. It should be remembered that the research period was the time of prosperity in the blue-chip market segment of the euro area (except for the relatively brief period of a Covid-19 pandemic outbreak), which limited a negative impact of benchmark volatility on the tracking error. However, in the case of increased stock market volatility, the quality of index performance mirroring may deteriorate. Under these circumstances, the number of changes in index constituents may also increase, which can also contribute to the deterioration of the ETFs index tracking ability15.

The study has significant implications for performance evaluation of exchange-traded funds. Primarily, the research results show that the TE values obtained by using the standard deviation of the difference between the return of the fund and that of its benchmark index and method of standard error of regression, are very similar. Our conclusion concerning three different methods of TE calculation is that it is not important whether we use the standard deviation of the difference between the return of an ETF and that of its benchmark index, or the standard error of regression, but it is valid whether we use the average of the absolute difference between the return of an ETF and that of the index.

Secondly, the study found that the lowest TE values occur when adopting daily intervals both for ETFs accumulating income and for those which distribute it. The research can be also important for investors. It proves that passively managed funds replicating performance of the blue chip index from developed markets can—under favorable market conditions—remarkably reduce the volatility of differential returns between the fund and the benchmark index.

Among the limitations of this study, which may be of considerable importance, there should be mentioned a fairly small sample. Nevertheless, considering a comparatively young age of the European ETF market, its saturation, and the fact that providers offer mainly distribution share classes, larger samples are hardly available.

Further research on the issues presented in this paper could be conducted in a few directions. First of all, a research sample may be expanded on other European funds tracking performance of the main euro zone stock indices, to better explain why there is a difference in the TE levels and why the pattern for different time intervals is not maintained. Secondly, factors affecting the tracking error of ETFs replicating returns of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index—such as replication method, assets under management, total expense ratio, volume, volatility and the fund’s age—should be examined.

Acknowledgements

“The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support was received during the preparation of this manuscript.”

Biographies

Ewa Feder-Sempach

serves as Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Sociology, University of Lodz, Poland. Graduated from the University of Lodz, receiving master’s degrees in International Economics (2004) and English Philology (2020). She also received the Ph.D. degree in Economics from Lodz University in 2010. Her scientific research includes international investments and portfolio analysis. She is also the author and the co-author of several publications, more than thirty articles, monographs and chapters devoted to international financial markets, investment theory and portfolio systematic risk.

Tomasz Miziołek

serves as Associate Professor at the Faculty of Economics and Sociology, University of Lodz, Poland. He graduated in International Trade from the University of Lodz, Poland, in 1995. He received the Ph.D. degree in Economics from University of Lodz in 2000. From 2000 to 2015, he was an Assistant Professor in the Department of International Economic Relations at the University of Lodz. Since 2016, he has been an Associate Professor in the Department of International Finance and Investment in the same University. His research activities are focused on mutual funds (especially passively managed), international investments, and financial indices. He is the author and the co-author of several publications, including book “International equity exchange-traded funds”.

Appendix

See Figs 1 and 2, Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Table 2.

Description of ETFs under study

| Name of the fund and share class (EIKON ticker) | Management company | Domicle of the fund | Share class inception date |

Reference currency | Index replication method | Stock exchanges and MTFs (listing currencies) | Ongoing charges p.a. | Assets under management (AUM) | Distribution frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A—funds with accumulating share classes (funds capitalizing dividends) | |||||||||

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (C) (C50.PA) | Amundi Luxembourg | Luxembourg | September 2008* | EUR | Physical (direct) |

Euronext Paris (EUR), Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), SIX Swiss Exchange (EUR), Borsa Italiana (EUR), BIVA (EUR) |

0.15% | EUR 2,382.92 million** | n/a |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Acc (SDJ50.DE) | Invesco Investment Management | Ireland | March 2009 | EUR | Synthetic |

Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR) Borsa Italiana (EUR), SIX Swiss Exchange (EUR), London Stock Exchange (GBP) |

0.05% | EUR 279.96 million** | n/a |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Acc) (CSSX5S.S) | BlackRock AM Ireland | Ireland | January 2010 | EUR | Physical (direct) |

SIX Swiss Exchange (EUR), Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), Borsa Italiana (EUR), London Stock Exchange (EUR, GBP, USD), Euronext Amsterdam (EUR), BMV (MXN) |

0.10% | EUR 4,176.34 million | n/a |

| Lyxor Core EURO STOXX 50 (DR) - UCITS ETF Acc (MSED.PA) | Lyxor International AM | Luxembourg | April 2013 | EUR | Physical (direct) |

Euronext Paris (EUR) London Stock Exchange (GBP), Borsa Italiana (EUR), Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), BMV (MXN) |

0.07% | EUR 320.92 million | n/a |

| Xtrackers EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF 1C (XESC.DE) | DWS Investment | Luxembourg | August 2008 | EUR | Physical (direct) |

Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR) London Stock Exchange (GBP), SIX Swiss Exchange (CHF), Stuttgart Stock Exchange (EUR), Borsa Italiana (EUR) |

0.09% | EUR 8,07 billion** | n/a |

| Panel B—funds with distributing share classes (funds distributing dividends) | |||||||||

| Acción Eurostoxx 50 ETF (BBVAE.MC) | BBVA AM | Spain | October 2006 | EUR | Physical (direct) | Bolsa de Madrid (EUR) | 0.15% | EUR 119.79 million | No data available |

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (D) (CD5.PA) | Amundi Luxembourg | Luxembourg | June 2010* | EUR | Physical (direct) |

Euronext Paris (EUR), Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), SIX Swiss Exchange (EUR), Borsa Italiana (EUR), BIVA (EUR) |

0.15% | EUR 2,382.92 million** | Once a year |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Dist (SDJE5D.DE) | Invesco Investment Management | Ireland | November 2009 | EUR | Synthetic |

Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), SIX Swiss Exchange (EUR), Borsa Italiana (EUR) |

0.05% | EUR 279.96 million** | Semi-annual |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Dist) (EUE.L) | Black Rock AM Ireland | Ireland | April 2000 | EUR | Physical (direct) | Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), London Stock Exchange (GBP), Borsa Italiana (EUR), Euronext Amsterdam (EUR), SIX Swiss Exchange (CHF), BATS Chi-X Europe (EUR), BMV (MXN) | 0.10% | EUR 4,379.17 million | Quarterly |

| iShares EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (DE) (STX50EEX.DE) | BlackRock AM Deutschland | Germany | December 2000 | EUR | Physical (direct) | Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), SIX Swiss Exchange (EUR), BATS Chi-X Europe (EUR) | 0.10% | EUR 5,910,71 million | Up to 4x per year |

| HSBC EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (H50E.L) | HSBC Global AM (UK) | Ireland | October 2009 | EUR | Physical (direct) |

London Stock Exchange (GBP) Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), Euronext Paris (EUR), SIX Swiss Exchange (EUR, USD), Borsa Italiana (EUR) |

0.05% | EUR 469.53 million | Semi-annual |

| Lyxor EURO STOXX 50 (DR) UCITS ETF – Dist (MSE.PA) | Lyxor International AM | France | February 2001 | EUR | Physical (direct) |

Euronext Paris (EUR), Borsa Italiana (EUR), Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), SIX Swiss Exchange (EUR), Wiener Boerse (EUR), Bolsa de Madrid (EUR), Chi-X Europe (EUR), CBOE DXE Amsterdam (EUR) |

0.20% | EUR 3,79.07 million** | Semi-annual |

| UBS ETF (LU) Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF (EUR) A-dis (E50EUA.DE) | UBS Fund Management (Luxembourg) | Luxembourg | October 2001 | EUR | Physical (direct) |

SIX Swiss Exchange (CHF, EUR) Borsa Italiana (EUR), Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR), London Stock Exchange (GBP, EUR), Euronext Amsterdam (EUR) |

0.15% | EUR 430.97 million | Semi-annual |

| Xtrackers Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF 1D (XESX.DE) | DWS Investment | Luxembourg | January 2007 | EUR | Physical (direct) |

Deutsche Boerse (Xetra) (EUR) SIX Swiss Exchange (CHF), London Stock Exchange (GBP), Stuttgart Stock Exchange (EUR), Borsa Italiana (EUR) |

0.09% | EUR 8,07 billion** | Once a year |

* Launching date of French fund Amundi ETF Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR managed by Amundi Asset Management, which was absorbed by Luxembourg fund Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR (EUR) on February 2018.

** - AUM of whole fund (not of share class). Assets of all funds as of the end of 2021, except for: Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (C) and Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (D) (31 January 2022), Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Acc and Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Dist (8 April 2022), and Acción Eurostoxx 50 ETF (7 February 2022).

Notes: The exhibit presents the sample of exchange-traded funds’ share classes replicating performance of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index divided into two panels: accumulating share classes (Panel A) and distributing share classes (Panel B). In the case of Xtrackers ETF and both Amundi ETFs, the method of replication was converted from synthetic to physical replication over the research period. Prior to May 2018 names of Invesco ETFs were Source Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF. All data as of the end of December 2021, unless stated otherwise.

Source: fund prospectuses, factsheets and Key Investor Information Documents (KIIDs)

Table 3.

Descriptive statistics of NAV per share rates of the return in 2012–2021 (daily data)

| Full name of the fund (EIKON ticker) | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Kurtosis | Skewness | Range | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | ||||||||

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (C) (C50.PA) | 0.0368 | 0.0617 | 1.2165 | 10.4660 | − 0.8393 | 22.0340 | − 13.2049 | 8.8292 |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Acc (SDJ50.DE) | 0.0353 | 0.0615 | 1.2164 | 10.5022 | − 0.8382 | 22.0527 | − 13.2191 | 8.8336 |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Acc) ( CSSX5E.S) | 0.0369 | 0.0640 | 1.2062 | 10.8385 | − 0.8472 | 22.0442 | − 13.2082 | 8.8360 |

| Lyxor Core EURO STOXX 50 (DR) - UCITS ETF Acc (MSED.PA) | 0.0370 | 0.0718 | 1.2072 | 12.2235 | − 1.0172 | 22.0570 | − 13.2243 | 8.8328 |

| Xtrackers EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF 1C (XESC.DE) | 0.0367 | 0.0627 | 1.1981 | 10.0527 | − 0.7254 | 22.0454 | − 13.2119 | 8.8336 |

| Panel B | ||||||||

| AcciónEurostoxx 50 ETF (BBVAE.MC) | 0.0245 | 0.0579 | 1.2205 | 10.3045 | − 0.8490 | 22.0296 | − 13.1912 | 8.8383 |

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (D) (CD5.PA) | 0.0246 | 0.0582 | 1.2332 | 9.9877 | − 0.8594 | 22.0338 | − 13.2049 | 8.8289 |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Dist (SDJE5D.DE) | 0.0230 | 0.0599 | 1.2277 | 10.1277 | − 0.8463 | 22.0525 | − 13.2191 | 8,8334 |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Dist) (EUE.L) | 0.0249 | 0.0515 | 1.2184 | 10.4054 | − 0.8175 | 22.0327 | − 13.2009 | 8.8318 |

| iShares EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (DE) (STX50EEX.DE) | 0.0241 | 0.0573 | 1.2168 | 10.4104 | − 0.8440 | 22.0234 | − 13.1919 | 8.8315 |

| HSBC EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (H50E.L) | 0.0260 | 0.0577 | 1.2178 | 10.3890 | − 0.8291 | 22.0402 | − 13.2044 | 8,8358 |

| Lyxor EURO STOXX 50 (DR) UCITS ETF – Dist (MSE.PA) | 0.0243 | 0.0569 | 1.2338 | 10.0951 | − 0.8704 | 22.0453 | − 13.2149 | 8.8304 |

| UBS ETF (LU) Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF (EUR) A-dis (E50EUA.DE) | 0.0246 | 0.0561 | 1.2071 | 9.7050 | − 0.7209 | 22.0394 | − 13.2067 | 8.8327 |

| Xtrackers Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF 1D (XESX.DE) | 0.0260 | 0.0593 | 1.2083 | 9.7022 | − 0.7252 | 22.0456 | − 13.2118 | 8.8338 |

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics of NAV per share rates of the return in 2012–2021 (weekly data)

| Full name of the fund (EIKON ticker) | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Kurtosis | Skewness | Range | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | ||||||||

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (C) (C50.PA) | 0.1781 | 0.3980 | 2.6620 | 10.8021 | − 1.4088 | 32.7009 | − 22.2767 | 10.4242 |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Acc (SDJ50.DE) | 0.1786 | 0.4008 | 2.6599 | 10.9088 | − 1.4269 | 32.7150 | − 22.2861 | 10.4289 |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Acc) ( CSSX5E.S) | 0.1799 | 0.4112 | 2.6524 | 10.9869 | − 1.4196 | 32.7066 | − 22.2802 | 10.4264 |

| Lyxor Core EURO STOXX 50 (DR) - UCITS ETF Acc (MSED.PA) | 0.1769 | 0.4010 | 2.6941 | 11.9119 | − 1.5486 | 32.6961 | − 22.2687 | 10.4274 |

| Xtrackers EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF 1C (XESC.DE) | 01792 | 0.4033 | 2.6566 | 10.9433 | − 1.4244 | 32.7110 | − 22.2797 | 10.4314 |

| Panel B | ||||||||

| AcciónEurostoxx 50 ETF (BBVAE.MC) | 0.1180 | 0.2726 | 2.6912 | 10.3794 | − 1.3757 | 32.7360 | − 22.3057 | 10.4303 |

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (D) (CD5.PA) | 0.1184 | 0.3287 | 2.6970 | 10.1021 | − 1.3469 | 32.7008 | − 22.2766 | 10.4242 |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Dist (SDJE5D.DE) | 0.1172 | 0.3370 | 2.6896 | 10.3011 | − 1.3784 | 32.7151 | − 22.2859 | 10.4291 |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Dist) (EUE.L) | 0.1200 | 0.3397 | 2.6627 | 10.6918 | − 1.3849 | 32.6928 | − 22.2673 | 10.4255 |

| iShares EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (DE) (STX50EEX.DE) | 0.1160 | 0.3377 | 2.6602 | 10.7875 | − 1.4027 | 32.7212 | − 22.2759 | 10.4453 |

| HSBC EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (H50E.L) | 0.1251 | 0.3491 | 2.6911 | 10.2788 | − 1.3772 | 32.7068 | − 22.2784 | 10.4284 |

| Lyxor EURO STOXX 50 (DR) UCITS ETF – Dist (MSE.PA) | 0.1172 | 0.3469 | 2.6901 | 10.2459 | − 1.3682 | 32.6963 | − 22.2702 | 10.4261 |

| UBS ETF (LU) Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF (EUR) A-dis (E50EUA.DE) | 0.1186 | 0.3299 | 2.6681 | 10.6334 | − 1.3915 | 32.6941 | − 22.2682 | 10.4259 |

| Xtrackers Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF 1D (XESX.DE) | 0.1271 | 0.3757 | 2.6877 | 10.2946 | − 1.3656 | 32.7113 | − 22.2800 | 10.4313 |

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of NAV per share rates of the return in 2012–2021 (monthly data)

| Full name of the fund (EIKON ticker) | Mean | Median | Standard Deviation | Kurtosis | Skewness | Range | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A | ||||||||

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (C) (C50.PA) | 0.7449 | 1.2239 | 4.6470 | 1.8603 | − 0.4263 | 34.2770 | − 17.6826 | 16.5943 |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Acc (SDJ50.DE) | 0.7468 | 1.1951 | 4.6109 | 1.9496 | − 0.4250 | 34.2904 | − 17.6902 | 16.6002 |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Acc) ( CSSX5E.S) | 0.7525 | 1.2910 | 4.6145 | 1.8726 | − 0.4132 | 34.2488 | − 17.6468 | 16.6020 |

| Lyxor Core EURO STOXX 50 (DR) - UCITS ETF Acc (MSED.PA) | 0.6845 | 1.1280 | 4.7136 | 2.0554 | − 0.3730 | 34.2727 | − 17.6707 | 16.6020 |

| Xtrackers EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF 1C (XESC.DE) | 0.7498 | 1.2501 | 4.6215 | 1.8994 | − 0.4219 | 34.2659 | − 17.6606 | 16.6053 |

| Panel B | ||||||||

| AcciónEurostoxx 50 ETF (BBVAE.MC) | 0.4851 | 1.1780 | 4.6804 | 1.8264 | − 0.3849 | 34.2867 | − 17.6525 | 16.6342 |

| Amundi Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF DR – EUR (D) (CD5.PA) | 0.4866 | 1.1166 | 4.5925 | 1.4948 | − 0.4821 | 32.1952 | − 17.6823 | 14.5129 |

| Invesco EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF Dist (SDJE5D.DE) | 0.4813 | 1.1390 | 4.7023 | 1.7037 | − 0.4281 | 34.2907 | − 17.6902 | 16.6005 |

| iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Dist) (EUE.L) | 0.4937 | 1.0897 | 4.6331 | 1.7465 | − 0.3693 | 34.0043 | − 17.6371 | 16.3671 |

| iShares EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (DE) (STX50EEX.DE) | 0.4767 | 1.1296 | 4.6339 | 1.9550 | − 0.4037 | 34.6225 | − 18.0232 | 16.5993 |

| HSBC EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF (H50E.L) | 0.5115 | 1.1880 | 4.6858 | 1.6373 | − 0.3561 | 34.1838 | − 17.5756 | 16.6083 |

| Lyxor EURO STOXX 50 (DR) UCITS ETF—Dist (MSE.PA) | 0.4816 | 0.8977 | 4.5998 | 1.8696 | − 0.3392 | 34.1765 | − 17.5861 | 16.5904 |

| UBS ETF (LU) Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF (EUR) A-dis (E50EUA.DE) | 0.4877 | 1.0788 | 4.5499 | 2.1300 | − 0.3577 | 34.2353 | − 17.6460 | 16.5892 |

| Xtrackers Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF 1D (XESX.DE) | 0.5242 | 0.8441 | 4.5846 | 1.9836 | − 0.3545 | 34.2661 | − 17.6608 | 16.6053 |

Authors contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by [Ewa Feder-Sempach]. The first draft of the manuscript was written by [Tomasz Miziołek] and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.”

Funding

The research was not directly financed.

Declaration

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest. The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Names of funds at the moment of their launch.

LDRS, which stands for “Leaders”, was Merrill Lynch`s branding for these ETFs. The current names of these funds, now managed by BlackRock, are: iShares Core EURO STOXX 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Dist) (EUE) and iShares STOXX Europe 50 UCITS ETF (EUN).

The Euro Stoxx 50 Index was also used by Lyxor to launch in 2001 the first in the European market synthetic ETF that used a swap to track the risk/return profile of the underlying index.

Exchange-traded funds, that mimic the performance of Stoxx Europe 50 and Euro Stoxx 50 indices, are ranked fourth and fifth on the list of the largest European ETFs, taking into account most popular underlying indices (PwC 2021).

In fact, index portfolio includes company shares from eight countries (France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, Italy, Ireland, Belgium, and Finland), because none of the companies from Luxembourg currently meet the requirements for participation in the Euro Stoxx 50 Index.

STOXX Ltd. (part of Qontigo) is an established and leading index specialist with a European heritage. According to Trackinsight (2021) STOXX is the fifth largest index provider in EMEA region by AUM tracked by ETFs.

The group of strategy indices based on the Euro Stoxx 50 Index comprises many other indices, including, among others, Euro Stoxx 50 Volatility Index (VSTOXX), Euro Stoxx 50 BuyWrite Index, Euro Stoxx 50 PutWrite Index, Euro Stoxx 50 Dividend Points (DVP) Futures Index, Euro iStoxx 50 Equal Risk Index and Euro Stoxx Low Risk Weighted 50 Index.

In total, the indices of STOXX Ltd. are licensed to about 500 financial institutions around the world.

Some ETFs are also listed outside Europe—on stock exchanges in Mexico (Bolsa Mexicana de Valores (BMV) and Bolsa Institucional de Valores (BIVA)).

One of the funds—Lyxor Euro Stoxx 50 (DR) UCITS ETF—has been operating a bit shorter, since March 2013.

Due to tax-efficiency reasons, only ETFs replicating net total return version of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index are on the market.

In the case of the Lyxor Euro Stoxx 50 (DR) UCITS ETF, it was 2218, 456 and 106 observations, respectively.

The total net asset value of EU-domiciled ETFs replicating performance of the Euro Stoxx 50 Index amounted to 53.2 billion EUR at the end of June 2021—significantly larger net assets are managed only by ETFs replicating performance of S&P 500 Index (228.6 billion EUR), and MSCI World Index (153.2 billion EUR) [PwC 2021].

For example, income generated by securities lending in the case of iShares Core Euro Stoxx 50 UCITS ETF EUR (Dist) in the period Q2 2014—Q2 2019 totalled 10 bps. Securities lending income had the equivalent effect of offsetting management fee in this ETF by 10% in Q2 2019 [BlackRock, 2019]. Securities lending is a common practice across European-listed ETFs – according to Morningstar [2019] it is used, among others, by all or some ETFs (especially using physical replication) managed by Amundi, Deutsche Bank (Xtrackers), BlackRock (iShares), UBS and Vanguard.

When changing the composition of the index, there may be a lag time between a liquidation of the index`s old constituents and the addition of its new constituents. During this span physically replicated ETFs have to not only limit cash drag, but also execute necessary transactions in the most cost-effective manner (often relying on internal crossing transactions or automated external trading and trade-crossing systems) to ultimately minimize tracking error.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Ewa Feder-Sempach, Email: ewa.feder@uni.lodz.pl.

Tomasz Miziołek, Email: tomasz.miziolek@uni.lodz.pl.

References

- Baş NK, Sarıoğlu SE. Tracking ability and pricing efficiency of exchange traded funds: Evidence from Borsa Istanbul. Business and Economics Research Journal. 2015;6(1):19–33. [Google Scholar]

- BlackRock. 2012. ETF Due Dilligence. A framework to help investors select the right European Exchange Traded Products (ETPs).

- BlackRock. 2019. iShares Securities Lending. Unlocking the potential of portfolios, https://www.ishares.com/uk/professional/en/literature/brochure/ishares-securities-lending-en-emea-pc.pdf.

- Blitz D, Huij J. Evaluating the performance of global emerging markets equity exchange-traded funds. Emerging Markets Review. 2012;13(2):149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ememar.2012.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charupat N, Miu P. Recent developments in exchange-traded funds literature. Pricing efficiency, tracking ability and effects on underlying assets. Managerial Finance. 2013;39(5):427–443. doi: 10.1108/03074351311313816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Chen Y, Frijns B. Evaluating the tracking performance and tracking error of New Zealand exchange traded funds. Pacific Accounting Review. 2017;29(3):443–462. doi: 10.1108/PAR-10-2016-0089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chu PKK. Study on the tracking errors and their determinants: evidence from Hong Kong exchange traded funds. Applied Financial Economics. 2011;21(5):309–315. doi: 10.1080/09603107.2010.530215. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaw A. Premiums/Discounts. tracking errors and performance of Saudi Arabian ETFs. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business. 2019;6(2):9–13. doi: 10.13106/jafeb.2019.vol6.no2.9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Easley D, Michayluk D, O’Hara M, Putnins TJ. The active world of passive investing. Review of Finance. 2021;25(5):1433–1471. doi: 10.1093/rof/rfab021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elton EJ, Gruber MJ, Comer GI, Li K. Spiders: Where are the bugs? Journal of Business. 2002;75(3):453–472. doi: 10.1086/339891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ETFGI. 2020. Deborah Fuhr`s presentation ETF Landscape: Flows, Trends and Outlook. https://www.focusrisparmio.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Deborah-Fuhr_12novembre2020.pdf

- ETFGI. 2022a. ETFGI reports global ETFs industry ended 2021 with a record US$10.27 trillion in assets and record net inflows of US$1.29 trillion. https://etfgi.com/news/press-releases/2022a/01/etfgi-reports-global-etfs-industry-ended-2021-record-us1027-trillion.

- ETFGI. 2022b. ETFGI reports the ETFs industry in Europe ended 2021 with record net inflows of US$194 billion and record assets of US$1.60 trillion. https://etfgi.com/news/press-releases/2022b/01/etfgi-reports-etfs-industry-europe-ended-2021-record-net-inflows-us194.

- Frino A, Gallagher DR, Neubert AS, Oetomo TN. Index design and implications for index tracking: Evidence from S&P 500 index funds. The Journal of Portfolio Management. 2004;30(2):89–95. doi: 10.3905/jpm.2004.319934. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher DR, Segara R. The performance and trading characteristics of exchange-traded funds. Journal of Investment Strategy. 2006;1(2):49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Groves, F. 2011. Exchange traded funds. A Concise Guide to ETFs, Harriman House, Petersfield.

- Hassine M, Roncalli T. Measuring performance of exchange traded funds. Journal of Index Investing. 2013;4(3):57–85. doi: 10.3905/jii.2013.4.3.057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson B, Bioy H, Kellett A, Davidson L. On the right track: Measuring tracking efficiency in ETFs. The Journal of Index Investing. 2013;4(3):35–41. doi: 10.3905/jii.2013.4.3.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khan AP, Bacha OI, Masih AM. Performance and trading characteristics of exchange traded funds: Developed vs emerging markets. Capital Markets Review. 2015;23(1&2):40–64. [Google Scholar]

- Kok-Leong Y, Wee-Yeap L, Izlin I. Does an exchange-traded fund converge to its benchmark in the long run? Evidence from iShares MSCI in Asia-Pacific Countries. Humanities and Social Sciences Letters. 2021;9(4):389–402. doi: 10.18488/journal.73.2021.94.389.402. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, V., and P. Mackintosh. 2010. ETF Mythbuster. Tracking Down the Truth, Credit Suisse North America.

- Madhavan A, Marchioni U, Li W, Yan DuD. Equity ETFs versus index futures: A comparision for fully funded investors. The Journal of Index Investing. 2015;5(2):66–75. doi: 10.3905/jii.2014.5.2.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Milonas, N.T., and G.G. Rompotis. 2006. Investigating European ETFs: The case of the Swiss exchange traded funds. In The Annual Conference of HFAA, Thessaloniki, Greece.

- Miziołek T, Feder-Sempach E. Tracking ability of exchange-traded funds. Evidence from Emerging Markets Equity ETFs. Bank i Kredyt, Narodowy Bank Polski. 2019;50(3):221–248. [Google Scholar]

- Miziołek T., E. Feder-Sempach, and A. Zaremba. 2020. International equity exchange-traded funds. Navigating Global ETF market opportunities and risks, Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

- Morningstar. 2019. A guided tour of the European ETF marketplace, https://www.rankiapro.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/A_Guided_Tour_of_the_European_ETF_Marketplace.pdf.

- Pope PF, Yadav PK. Discovering errors in tracking error. The Journal of Portfolio Management. 1994;20(2):27–32. doi: 10.3905/jpm.1994.409471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poterba, J.M., J. B. Shoven. 2002. Exchange traded funds: A new investment option for taxable investors, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Working Paper No. 8781.

- PwC. 2021. European ETF Listing and Distribution. Global fund distribution and market research centre. October 2021, https://www.pwc.lu/en/asset-management/docs/pwc-european-etf-listing-distribution.pdf

- PwC. 2022. ETFs 2026: The next big leap, https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/financial-services/publications/assets/ETF_2026_PwC.pdf

- Qadan M, Yagil J. On the dynamics of tracking indices by exchange traded funds in the presence of high volatility. Managerial Finance. 2012;38(9):804–832. doi: 10.1108/03074351211248162. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roll R. A mean/variance analysis of tracking error. The Journal of Portfolio Management. 1992;18(4):13–22. doi: 10.3905/jpm.1992.701922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rompotis GG. Performance and trading characteristics of German passively managed ETFs. International Research Journal of Finance & Economics. 2008;15:210–223. [Google Scholar]

- Rompotis GG. The German exchange traded funds. The IUP Journal of Applied Finance. 2012;18(4):62–82. [Google Scholar]

- STOXX Limited. 2018. STOXX Exchange Traded Products, September 2018 https://www.stoxx.com/documents/stoxxnet/Documents/Resources/Exchange_Traded_Products/Exchange_traded_products_STOXX_Sep_2018.pdf.

- Qontigo. 2022a. Euro Stoxx 50 Index fact sheet, https://www.stoxx.com/download/indices/factsheets/SX5GT.pdf.

- Qontigo. 2022b. STOXX Index Methodology Guide (Portfolio Based Indices). Creating an Investment Intelligence Advantage. January 2022b, https://www.stoxx.com/document/Indices/Common/Indexguide/stoxx_index_guide.pdf

- Qontigo. 2022c. Exchange Traded Products, https://www.stoxx.com/documents/stoxxnet/Documents/Resources/Exchange_Traded_Products/Exchange_traded_products_STOXX_Qontigo.pdf

- Refinitiv EIKON database, available at the University of Lodz.

- Shin S, Soydemir G. Exchange-traded funds, persistence in tracking errors and information dissemination. Journal of Multinational Financial Management. 2010;20(4–5):214–234. doi: 10.1016/j.mulfin.2010.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trackinsight. 2021. Global ETF Survey 2021, https://am.jpmorgan.com/content/dam/jpm-am-aem/americas/mx/en/insights/portfolio-insights/Global-ETF-Survey-2021.pdf

- Yiannaki SM. ETFs performance Europe – a good start or not? Procedia Economics and Finance. 2015;30:955–966. doi: 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)01346-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]