Abstract

Introduction

In Hong Kong, CoronaVac and BNT162b2 have been approved for emergency use owing to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Reactions towards the vaccine and the risk of post-vaccination adverse events may be different between recipients with and without type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Objective

The aim of this study was to evaluate the risk of adverse events of special interest (AESI) and acute diabetic complications in the T2DM population after COVID-19 vaccination in Hong Kong.

Research Design and Methods

Self-controlled case-series analysis was conducted. Patients with T2DM who received at least one dose of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac between 23 February 2021 and 31 January 2022 from electronic health records in Hong Kong were included. The incidence rates of 29 AESIs and acute diabetic complications (any of severe hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis or hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome) requiring hospitalization within 21 days after the first or second dose of vaccination were reported. The risks of these outcomes were evaluated using conditional Poisson regression.

Results

Among 141,224 BNT162b2 recipients and 209,739 CoronaVac recipients with T2DM, the incidence per 100,000 doses and incidence per 100,000 person-years of individual AESIs and acute diabetic complications ranged from 0 to 24.4 and 0 to 438.6 in BNT162b2 group, and 0 to 19.5 and 0 to 351.6 in CoronaVac group. We did not observe any significantly increased risk of individual AESIs or acute diabetic complications after first or second doses of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccine. Subgroup analysis based on HbA1c < 7% and ≥ 7% also did not show significantly excess risk after vaccination.

Conclusions

Patients with T2DM do not appear to have higher risks of AESI and acute diabetic complications after BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccination. Moreover, given the low incidence of AESIs and acute diabetic complications after vaccination, the absolute risk increment was likely minimal.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40264-022-01228-6.

Key Points

| The risk of adverse events of special interest and acute diabetic complications were not increased after coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccination. |

| The benefits of COVID-19 vaccination in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) patients outweigh its potential risks since T2DM was associated with severe adverse outcomes and mortality in COVID-19. |

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) increases the risk of severe adverse outcomes and mortality in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1, 2]; therefore, the diabetic population has been prioritized for COVID-19 vaccination in countries such as the US and the UK [3, 4]. In Hong Kong, two vaccines have been approved for emergency use owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, namely CoronaVac from Sinovac Biotech (Hong Kong) Limited (equivalent to Sinovac Life Sciences Company Limited) and BNT162b2 from Fosun Pharma/BioNTech (equivalent to the BioNTech vaccine marketed by Pfizer outside of China).

Adverse events associated with COVID-19 vaccination have been one of the major concerns. Occasional case reports describing the occurrence of acute hyperglycemic crisis, blood glucose fluctuation and acute myocardial injury in prediabetic or diabetic patients after vaccination brought about safety concerns of vaccine in patients with T2DM [5–7]. The randomized controlled trials of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac, and a population-based cohort study in the US, showed no major adverse events, including myocarditis and thromboembolism, after vaccination [8–10], contradicting a few observational studies revealing potentially increased risk [11–13]. Conflicting findings from these studies warrant further evaluation of vaccine safety. Besides, as these studies included a relatively small proportion of patients with T2DM, their findings in the general population may not be directly applicable to the T2DM population. Moreover, analytical study specifically evaluating the risk of acute diabetic complications, such as severe hypoglycemia, diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome, after COVID-19 vaccination are lacking. Due to the potential immune dysfunction in patients with T2DM [14–17], reactions towards the vaccine and the risk of post-vaccination adverse events may be different between those with and without T2DM. Prior studies have shown that concerns of vaccine safety is a major reason for COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [18, 19]. In view of this, our study aimed to evaluate whether there is excess risk of post-vaccination adverse events in patients with T2DM, using a population-based diabetes cohort in Hong Kong.

Research Design and Methods

Study Design

This self-controlled case-series (SCCS) study was conducted to investigate the excess risk of adverse events of special interest (AESI) and acute diabetic complications in patients with T2DM after BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccination. SCCS is a study design that was specifically developed to assess vaccine safety, and was applied in several COVID-19 and other vaccine safety studies [12, 20–27]. It is able to compare risks of outcomes in different periods, including exposure and non-exposure periods, within an individual. Hence, SCCS can minimize any measured or unmeasured time-invariant confounding effects by treating the same individual as control.

Data Source

The electronic health records from the clinical management system of the Hospital Authority (HA) were used in this study. HA is a statutory administrative body in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR), which manages 43 public hospitals, 49 specialist outpatient clinics and 73 primary care clinics. More than 20 million attendances at these public healthcare facilities and over 70% of hospitalization in Hong Kong were recorded in the year 2018–2019 [28, 29]. All medical records from public hospitals, ambulatory clinics, specialist clinics, general outpatient clinics, and emergency rooms in the HA could be accessed via the clinical management system, including demographic information, diagnoses, medication and laboratory tests for each patient. Data from this system have been utilized to conduct pharmacovigilance studies, including studies that evaluated vaccines against COVID-19 [30–32]. Two COVID-19 vaccines, namely BNT162b2 and CoronaVac, have been currently available under emergency use by the government for people aged 16 years or above in Hong Kong since 23 February 2021. The rollout schedule of the vaccination program is stated in electronic supplementary material (ESM) 1. Details of the vaccination status, which were linked with the data from the clinical management system using a de-identified unique identifier for each patient, were obtained from the Department of Health of the HKSAR Government.

Study Population

This study included patients aged ≥ 16 years who had received at least one dose of BNT162b2 or CoronaVac in Hong Kong between 23 February 2021 and 31 January 2022. Individuals who had a documented diagnosis of T2DM from 1 January 2005 to 23 February 2021, or had a prescription of any oral antidiabetic drug within 90 days before 23 February 2021, were considered to be patients with T2DM and were included in this study. Patients who had a documented diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus from 1 January 2005 to 23 February 2021 were excluded. The diagnosis of T2DM was determined by the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code of 250.x0 or 250.x2, or the International Classification of Primary Care, Second edition (ICPC-2) code of T90.

Outcomes

AESI was selected from a list of events advocated by the WHO Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety [33]. A total of 29 AESIs were studied, including autoimmune diseases (Guillain–Barré Syndrome, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, narcolepsy, acute aseptic arthritis, [idiopathic] thrombocytopenia and subacute thyroiditis), cardiovascular diseases (microangiopathy, heart failure, stress cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, arrhythmia and myocarditis), adverse events involving the circulatory system (thromboembolism, hemorrhagic disease, single organ cutaneous vasculitis), hepato-renal system (acute liver injury, acute kidney injury and acute pancreatitis), peripheral and central nervous systems (generalized convulsion, meningoencephalitis, transverse myelitis and Bell’s palsy), respiratory system (acute respiratory distress syndrome), skin and mucous membrane, joints (erythema multiforme and chilblain-like lesions) and others (anaphylaxis, anosmia, Kawasaki disease and rhabdomyolysis). The other set of outcomes of interest is related to glycemia, which included acute diabetic complications, namely severe hypoglycemia, hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome and diabetic ketoacidosis. All the above outcomes were primarily defined based on inpatient diagnosis with ICD-9-CM codes and procedure codes. The detailed definition of each outcome is shown in ESM Table 1.

Regarding the sample size calculation, assuming the relative risk of 1.5–3.0, the total sample size required was from 40 to 376 to achieve 80% power at 0.05 significance level for the SCCS analyses, respectively. A detailed sample size calculation for SCCS analysis is provided in ESM Fig. 1.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics. When analyzing each outcome event (except for anaphylaxis), persons with a previous diagnosis of that event before 23 February 2021 were excluded, and any new diagnosis within 21 days after the first or second doses of vaccine was interpreted as incident outcomes. The 21-day follow-up period after each dose was considered to be sufficient to identify an early excess risk of adverse events, and this risk period has been used in other COVID-19 vaccine safety studies [10, 11]. Since it would be difficult to classify allergic reactions with symptom onset of 2 days or more after vaccination, the risk period of anaphylaxis was defined as 2 days (i.e. 0–1 day post-vaccination). This approach has also been applied by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the US when monitoring anaphylaxis after BNT162b2 vaccination [34]. Incidence per 100,000 doses, incidence per 100,000 persons, and incidence rate (cases per 100,000 person-years) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated for the vaccinated group.

Self-Controlled Case-Series Analysis

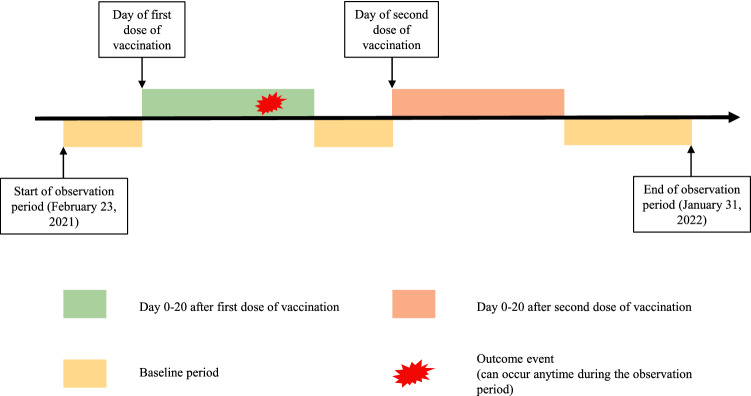

Two exposure periods, i.e. 0–20 days after the first dose and 0–20 days after the second dose, were evaluated in SCCS analysis. The remainder of the time during the observation period from 23 February 2021 to 31 January 2022 was defined as baseline periods, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Starting from 1 January 2022 onwards, the new arrangement of the booster dose was implemented to adults who were already fully vaccinated, with the second dose received 6 months previously [35]. However, our vaccination records retrieved only included records up to 31 January 2022, hence the majority of the vaccine recipients had not yet received the booster dose. Therefore, to minimize the effect of the booster dose, the individual observation period started on 23 February 2021 and ended on 31 January 2022 or the day before the booster dose, whichever was earlier. SCCS analysis was only conducted when the total number of outcome events were at least five. Theoretically, there are three assumptions when using the SCCS model [36]. First, outcome events should be independently recurrent such that events would not be affected by previous occurrences. However, this assumption might be violated in this study as some of the outcomes of interest might occur recurrently and were likely to increase the risk of future episodes. In such conditions, only the first incident event should be used for analysis [36]. Therefore, we only took into consideration the first incident of outcome events since 2005, the earliest date of data availability, during the observation period. The second assumption is that the episodes of outcome events should not affect the exposure. Hence, it may not be appropriate to fit this study into a standard (classical) SCCS model as patients with a history of the outcomes of interest are less likely to receive the vaccine in Hong Kong due to vaccine hesitancy. The third assumption is that the event should not be censored by outcome event or mortality during the whole observation period. To avoid violating the second and third assumption, we used a modified SCCS model, which is proposed by the inventors of SCCS to evaluate COVID-19 vaccine safety [22], for this study. The modified SCCS model was specifically designed to handle outcomes that would affect exposure. Unvaccinated people who developed the outcome of interest were also included in the modified SCCS model to estimate the probability of receiving vaccination among people with outcome events. Therefore, the association between vaccination and risk of outcomes could be adjusted accordingly. No censoring during the entire observation period was needed in this study as the modified SCCS already takes mortality into account [22]. The modified SCCS has been widely used in the evaluation of COVID-19 vaccine safety [24–27].

Fig. 1.

Observation timeline of a hypothetical patient in the self-controlled case series

The modified SCCS for investigating event-dependent exposure was conducted using the R function ‘eventdepenexp’ in the R-package ‘SCCS’. This study adjusted the seasonal effect by month. Conditional Poisson regression was applied to estimate the adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR) and 95% CI by comparing the incidence rate of outcomes in different risk periods with that in the baseline periods. Each outcome of interest was investigated individually and people with a history of the corresponding outcome before 23 February 2021 were excluded from the analysis. We calculated risk differences per 100,000 persons between the incidences in risk periods and the baseline period, where a lower value of risk difference indicates no or less excess risk after vaccination. To ensure robustness, we conducted five sensitivity analyses. The length of the risk periods was changed from 21 days to 14 days and 28 days and 49 days in the first three sensitivity analyses. As COVID-19 potentially increased the risk of AESI, patients who had COVID-19 before or during the study period were excluded in the fourth sensitivity analysis. In the fifth sensitivity analysis, people who received their first dose on or after 31 December 2021 were excluded to ensure a minimum follow-up period of 30 days after vaccination. Subgroup analysis was also conducted by stratifying patients with HbA1c < 7% and ≥ 7%.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and only p values < 0.05 were considered significant. R version 4.0.3 were used to conduct all the statistical analyses. At least two investigators (WX and VKCY) independently conducted the analyses for quality assurance.

Results

A total of 1,743,081 and 1,333,533 subjects received at least one dose of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac, respectively, during the period 23 February 2021 to 31 January 2022. Among these vaccine recipients, 141,224 (8.1%) and 209,739 (15.7%) patients with T2DM were included in the BNT162b2 and CoronaVac groups, respectively; 89.3% (n = 126,199) of BNT162b2 recipients and 77.6% (n = 162,772) of CoronaVac recipients completed two doses of vaccine within the study period. The total number of administered doses for BNT162b2 and CoronaVac was 267,423 and 372,511, respectively. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study cohort. The average age, Charlson comorbidity index, and proportion of males was 64.68 years (standard deviation [SD] 11.37), 2.98 (SD 1.45) and 55.1% in the BNT162b2 group, respectively, and 68.14 years (SD 10.74), 3.34 (SD 1.43) and 50.6% in the CoronaVac group, respectively. ESM Table 2 shows the comorbidities and medications used for these patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients receiving BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccination

| BNT162b2 | CoronaVac | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 141,224 | 209,739 |

| Age, years [mean (SD)] | 64.68 (11.37) | 68.14 (10.74) |

| Sex, male | 77,781 (55.1) | 106,109 (50.6) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index [mean (SD)] | 2.98 (1.45) | 3.34 (1.43) |

| HbA1c | ||

| < 7% | 92,951 (65.82) | 137,195 (65.41) |

| 7–7.9% | 29,670 (21.01) | 45,378 (21.64) |

| 8–8.9% | 8483 (6.01) | 12,896 (6.15) |

| ≥ 9% | 6594 (4.67) | 9275 (4.42) |

| Missing | 3526 (2.50) | 4995 (2.38) |

| History of outcome diseases | ||

| Guillain–Barré Syndrome | 273 (0.2) | 431 (0.2) |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis | 3 (0.0) | 5 (0.0) |

| Narcolepsy | 7848 (5.6) | 8230 (3.9) |

| Acute aseptic arthritis | 1292 (0.9) | 2155 (1.0) |

| (Idiopathic) thrombocytopenia | 441 (0.3) | 687 (0.3) |

| Subacute thyroiditis | 12 (0.0) | 19 (0.0) |

| Microangiopathy | 5 (0.0) | 8 (0.0) |

| Heart failure | 2566 (1.8) | 4732 (2.3) |

| Stress cardiomyopathy | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Coronary artery disease | 14,009 (9.9) | 22,102 (10.5) |

| Arrhythmia | 5765 (4.1) | 10,515 (5.0) |

| Myocarditis | 418 (0.3) | 716 (0.3) |

| Thromboembolism | 16,021 (11.3) | 28,532 (13.6) |

| Hemorrhagic disease | 5833 (4.1) | 11,639 (5.5) |

| Single-organ cutaneous vasculitis | 374 (0.3) | 596 (0.3) |

| Acute liver injury | 8589 (6.1) | 11,283 (5.4) |

| Acute kidney injury | 5437 (3.8) | 10,042 (4.8) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 778 (0.6) | 1234 (0.6) |

| Generalized convulsion | 842 (0.6) | 1267 (0.6) |

| Meningoencephalitis | 176 (0.1) | 225 (0.1) |

| Transverse myelitis | 7 (0.0) | 11 (0.0) |

| Bell’s palsy | 1403 (1.0) | 2221 (1.1) |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 2006 (1.4) | 2976 (1.4) |

| Erythema multiforme | 35 (0.0) | 44 (0.0) |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 23 (0.0) | 33 (0.0) |

| Anosmia, ageusia | 171 (0.1) | 203 (0.1) |

| Anaphylaxis | 4159 (2.9) | 6815 (3.2) |

| Kawasaki disease | 110 (0.1) | 167 (0.1) |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 283 (0.2) | 405 (0.2) |

| Hypoglycemia | 1757 (1.2) | 3207 (1.5) |

| Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome | 1900 (1.3) | 2699 (1.3) |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 301 (0.2) | 297 (0.1) |

Data are expressed as n (%) unless otherwise specified

SD standard deviation

Table 2 displays the incidence of AESI and hypoglycemia within 21 days after BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccination. In general, the incidence of AESI, diabetic complications and all-cause mortality within 21 days after BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccination was rare. In the BNT162b2 group, the incidence ranged from 0 to 24.4 per 100,000 doses; from 0 to 46.4 per 100,000 persons; and incidence rate from 0 to 438.6 per 100,000 person-years. For CoronaVac recipients, the incidence ranged from 0 to 19.5 per 100,000 doses; from 0 to 34.8 per 100,000 persons; and incidence rate from 0 to 351.6 per 100,000 person-years. The following AESI events were not observed after vaccination: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, thrombocytopenia, subacute thyroiditis, microangiopathy, stress cardiomyopathy, single-organ cutaneous vasculitis, transverse myelitis, chilblain-like lesions, anosmia, and Kawasaki disease. There was no incidence of erythema multiforme and diabetic ketoacidosis after BNT162b2 vaccination, and there was no incidence of meningoencephalitis after CoronaVac vaccination. Meanwhile, only four outcomes, including coronary artery disease, arrhythmia, thromboembolism, and narcolepsy (in the BNT16b2 group only), had an incidence rate of higher than 20 per 100,000 persons after BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccination.

Table 2.

Incidence rate of adverse events of special interest among patients receiving BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccination

| Event | Incidence per 100,000 doses | Incidence per 100,000 persons | Incidence rate (per 100,000 person-years) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b2 | ||||

| Overall adverse events of special interest | 109 | 61.49 (50.49, 74.17) | 117.12 (96.18, 141.26) | 1,102.42 (913.73, 1330.08) |

| Autoimmune disease | 39 | 15.68 (11.15, 21.43) | 29.69 (21.12, 40.59) | 282.03 (206.06, 386.01) |

| Guillain–Barré syndrome | 1 | 0.37 (0.01, 2.09) | 0.71 (0.02, 3.95) | 6.74 (0.95, 47.82) |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Narcolepsy | 33 | 13.09 (9.01, 18.38) | 24.78 (17.06, 34.79) | 235.45 (167.39, 331.19) |

| Acute aseptic arthritis | 7 | 2.64 (1.06, 5.44) | 5.00 (2.01, 10.31) | 47.50 (22.65, 99.64) |

| (Idiopathic) thrombocytopenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subacute thyroiditis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 60 | 25.95 (19.80, 33.40) | 49.28 (37.61, 63.43) | 465.93 (361.77, 600.08) |

| Microangiopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart failure | 15 | 5.71 (3.20, 9.42) | 10.82 (6.06, 17.85) | 102.65 (61.89, 170.27) |

| Stress cardiomyopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coronary artery disease | 33 | 13.70 (9.43, 19.24) | 25.98 (17.88, 36.48) | 246.10 (174.96, 346.16) |

| Arrhythmia | 32 | 12.47 (8.53, 17.60) | 23.64 (16.17, 33.38) | 224.09 (158.47, 316.88) |

| Myocarditis | 1 | 0.38 (0.01, 2.09) | 0.71 (0.02, 3.96) | 6.74 (0.95, 47.87) |

| Circulatory system | 63 | 26.76 (20.56, 34.23) | 50.83 (39.06, 65.03) | 480.21 (375.14, 614.72) |

| Thromboembolism | 58 | 24.43 (18.55, 31.58) | 46.40 (35.24, 59.98) | 438.55 (339.04, 567.27) |

| Hemorrhagic disease | 10 | 3.90 (1.87, 7.17) | 7.39 (3.54, 13.59) | 70.02 (37.68, 130.14) |

| Single-organ cutaneous vasculitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepato-renal system | 5 | 2.08 (0.68, 4.85) | 3.94 (1.28, 9.20) | 37.38 (15.56, 89.81) |

| Acute liver injury | 2 | 0.80 (0.10, 2.88) | 1.51 (0.18, 5.45) | 14.33 (3.58, 57.31) |

| Acute kidney injury | 3 | 1.17 (0.24, 3.41) | 2.21 (0.46, 6.46) | 20.94 (6.75, 64.92) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 2 | 0.75 (0.09, 2.72) | 1.42 (0.17,5.15) | 13.52 (3.38, 54.07) |

| Nerves and central nervous system | 10 | 3.87 (1.86, 7.12) | 7.34 (3.52, 13.50) | 69.62 (37.46, 129.40) |

| Generalized convulsion | 5 | 1.92 (0.62, 4.47) | 3.63 (1.18, 8.47) | 34.43 (14.33, 82.73) |

| Meningoencephalitis | 1 | 0.37 (0.01, 2.09) | 0.71 (0.02, 3.95) | 6.73 (0.95, 47.79) |

| Transverse myelitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bell’s palsy | 4 | 1.51 (0.41, 3.87) | 2.86 (0.78, 7.33) | 27.17 (10.20, 72.38) |

| Respiratory system (acute respiratory distress syndrome) | 10 | 3.79 (1.82, 6.98) | 7.19 (3.45, 13.22) | 68.19 (36.69, 126.74) |

| Skin and mucous membrane, joints system | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Erythema multiforme | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | ||||

| Anaphylaxisa | 1 | 0.39 (0.01, 2.15) | 0.73 (0.02, 4.07) | 70.30 (9.90, 499.04) |

| Anosmia, ageusia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kawasaki disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 2 | 0.75 (0.09, 2.71) | 1.42 (0.17, 5.13) | 13.48 (3.37, 53.88) |

| Acute diabetes complications | 35 | 13.45 (9.37, 18.70) | 25.49 (17.76, 35.45) | 241.72 (173.55, 336.66) |

| Hypoglycemia | 27 | 10.23 (6.74, 14.88) | 19.38 (12.77, 28.19) | 183.85 (126.08, 268.09) |

| Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome | 9 | 3.41 (1.56, 6.48) | 6.46 (2.96, 12.27) | 61.35 (31.92, 117.92) |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All-cause mortality | 25 | 9.35 (6.05, 13.80) | 17.70 (11.46, 26.13) | 168.11 (113.59, 248.78) |

| CoranaVac | ||||

| Overall adverse events of special interest | 139 | 57.09 (47.99, 67.40) | 102.72 (86.36, 121.27) | 1,027.88 (870.45, 1,213.78) |

| Autoimmune disease | 38 | 10.79 (7.64, 14.82) | 19.17 (13.57, 26.32) | 195.27 (142.09, 268.36) |

| Guillain–Barré syndrome | 1 | 0.27 (0.01, 1.50) | 0.48 (0.01, 2.66) | 4.87 (0.69, 34.55) |

| Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Narcolepsy | 27 | 7.56 (4.98, 10.99) | 13.41 (8.84, 19.51) | 136.74 (93.77, 199.39) |

| Acute aseptic arthritis | 10 | 2.71 (1.30, 4.99) | 4.82 (2.31, 8.86) | 49.05 (26.39, 91.16) |

| (Idiopathic) thrombocytopenia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Subacute thyroiditis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 96 | 30.21 (24.47, 36.89) | 54.02 (43.76, 65.96) | 545.24 (446.39,665.98) |

| Microangiopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Heart failure | 31 | 8.50 (5.78, 12.07) | 15.13 (10.28, 21.48) | 153.73 (108.11, 218.60) |

| Stress cardiomyopathy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Coronary artery disease | 40 | 11.98 (8.56, 16.31) | 21.35 (15.25, 29.07) | 216.44 (158.76, 295.07) |

| Arrhythmia | 52 | 14.67 (10.95, 19.23) | 26.13 (19.52, 34.27) | 265.03 (201.95, 347.80) |

| Myocarditis | 2 | 0.54 (0.07, 1.95) | 0.96 (0.12, 3.46) | 9.75 (2.44, 38.97) |

| Circulatory system | 65 | 20.29 (15.66, 25.85) | 36.29 (28.01, 46.25) | 365.96 (286.98, 466.68) |

| Thromboembolism | 63 | 19.48 (14.97, 24.93) | 34.84 (26.78, 44.58) | 351.58 (274.65, 450.05) |

| Hemorrhagic disease | 9 | 2.55 (1.17, 4.84) | 4.54 (2.08, 8.63) | 46.10 (23.99, 88.60) |

| Single-organ cutaneous vasculitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hepato-renal system | 12 | 3.59 (1.86, 6.27) | 6.39 (3.30,11.16) | 64.93 (36.88, 114.34) |

| Acute liver injury | 3 | 0.85 (0.18, 2.49) | 1.51 (0.31, 4.42) | 15.42 (4.97, 47.81) |

| Acute kidney injury | 5 | 1.41 (0.46, 3.28) | 2.51 (0.81, 5.85) | 25.42 (10.58, 61.08) |

| Acute pancreatitis | 6 | 1.62 (0.59, 3.53) | 2.88 (1.06, 6.26) | 29.31 (13.17, 65.25) |

| Nerves and central nervous system | 14 | 3.89 (2.13, 6.53) | 6.92 (3.78, 11.60) | 70.33 (41.65, 118.74) |

| Generalized convulsion | 1 | 0.27 (0.01, 1.53) | 0.49 (0.01, 2.72) | 4.97 (0.70, 35.25) |

| Meningoencephalitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transverse myelitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bell’s palsy | 13 | 3.53 (1.88, 6.03) | 6.27 (3.34, 10.72) | 63.82 (37.06, 109.92) |

| Respiratory system (acute respiratory distress syndrome) | 16 | 4.36 (2.49, 7.07) | 7.74 (4.43, 12.57) | 78.79 (48.27, 128.60) |

| Skin and mucous membrane, joints system | 1 | 0.27 (0.01, 1.50) | 0.48 (0.01, 2.66) | 4.86 (0.68, 34.49) |

| Erythema multiforme | 1 | 0.27 (0.01, 1.50) | 0.48 (0.01, 2.66) | 4.86 (0.68, 34.49) |

| Chilblain-like lesions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Others | ||||

| Anaphylaxisa | 1 | 0.28 (0.01, 1.55) | 0.49 (0.01, 2.75) | 50.69 (7.14, 359.83) |

| Anosmia, ageusia | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Kawasaki disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 2 | 0.54 (0.07, 1.94) | 0.96 (0.12, 3.45) | 9.73 (2.43, 38.91) |

| Acute diabetes complications | 53 | 14.64 (10.97, 19.15) | 26.05 (19.52, 34.07) | 264.74 (202.25, 346.53) |

| Hypoglycemia | 38 | 10.36 (7.33, 14.22) | 18.43 (13.04, 25.29) | 187.36 (136.33, 257.49) |

| Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome | 22 | 5.99 (3.75, 9.06) | 10.64 (6.67, 16.10) | 108.26 (71.29, 164.42) |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| All-cause mortality | 47 | 12.62 (9.27, 16.78) | 22.41 (16.47, 29.80) | 228.27 (171.51, 303.82) |

aThe follow-up period of the incidence of anaphylaxis was 2 days (i.e. 0–1 day post-vaccination), and the anaphylaxis was not included in the calculation of the incidence of the overall adverse events of special interest

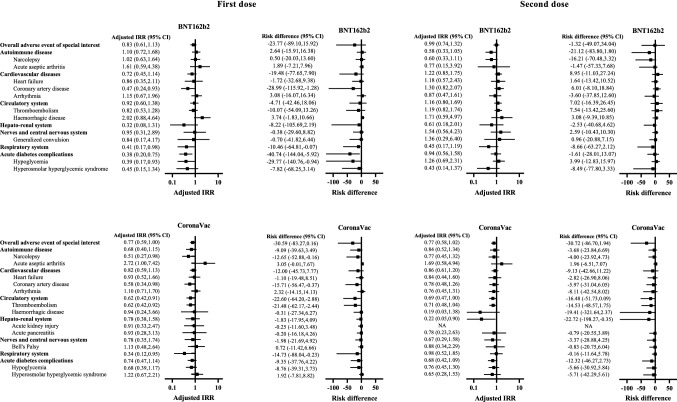

Figure 2 and Table 3 suggest that there was no significantly increased risk of individual AESI or acute diabetic complications within 21 days after the first or second dose of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccination. In general, the risk difference of individual AESI or acute diabetic complications was small, ranging from −29.8 to 7.5 incidence per 100,000 persons in the BNT162b2 group, and from −21.5 to 3.1 incidence per 100,000 persons in the CoronaVac group.

Fig. 2.

Adjusted incidence rate ratio and risk difference of adverse events of special interest and acute diabetes complications after vaccination of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac

Table 3.

Adjusted incidence rate ratio and risk difference of adverse events of special interest and acute diabetes complications for 21-day follow-up period after vaccination of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac

| Reference | First dose | Second dose | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event | Event | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | Risk difference (95% CI), incidence per 100,000 persons | Event | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | Risk difference (95% CI), incidence per 100,000 persons | |

| BNT162b2 | |||||||

| Overall adverse events of special interest | 4368 | 53 | 0.83 (0.61, 1.13) | − 23.77 (− 89.10, 15.92) | 56 | 0.99 (0.74, 1.32) | − 1.32 (− 49.07, 34.04) |

| Autoimmune disease | 941 | 26 | 1.10 (0.72, 1.68) | 2.64 (− 15.91, 16.38) | 13 | 0.58 (0.33, 1.05) | − 21.12 (− 83.80, 1.80) |

| Narcolepsy | 623 | 21 | 1.02 (0.63, 1.64) | 0.50 (− 20.03, 13.60) | 12 | 0.60 (0.33, 1.11) | − 16.21 (− 70.48, 3.32) |

| Acute aseptic arthritis | 305 | 5 | 1.61 (0.59, 4.38) | 1.89 (− 7.21, 7.96) | 2 | 0.77 (0.15, 3.92) | − 1.47 (− 57.33, 7.68) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 3463 | 24 | 0.72 (0.45, 1.14) | − 19.48 (− 77.65, 7.90) | 36 | 1.22 (0.85, 1.75) | 8.95 (− 11.03, 27.24) |

| Heart failure | 1637 | 6 | 0.86 (0.35, 2.11) | − 1.72 (− 32.68, 9.38) | 9 | 1.18 (0.57, 2.43) | 1.64 (− 13.42, 10.52) |

| Coronary artery disease | 1951 | 10 | 0.47 (0.24, 0.93) | − 28.99 (− 115.92, − 1.28) | 23 | 1.30 (0.82, 2.07) | 6.01 (− 8.10, 18.84) |

| Arrhythmia | 1603 | 20 | 1.15 (0.67, 1.96) | 3.08 (− 16.07, 16.34) | 12 | 0.87 (0.47, 1.61) | − 3.60 (− 37.85, 12.60) |

| Circulatory system | 3257 | 29 | 0.92 (0.60, 1.38) | − 4.71 (− 42.46, 18.06) | 34 | 1.16 (0.80, 1.69) | 7.02 (− 16.39, 26.45) |

| Thromboembolism | 3049 | 25 | 0.82 (0.53, 1.28) | − 10.07 (− 54.09, 13.26) | 33 | 1.19 (0.82, 1.74) | 7.54 (− 13.42, 25.60) |

| Hemorrhagic disease | 445 | 6 | 2.02 (0.88, 4.64) | 3.74 (− 1.83, 10.66) | 4 | 1.71 (0.59, 4.97) | 3.08 (− 9.39, 10.85) |

| Hepato-renal system | 869 | 2 | 0.32 (0.08, 1.31) | − 8.22 (− 105.69, 2.19) | 3 | 0.61 (0.18, 2.01) | − 2.53 (− 40.68, 4.62) |

| Nerves and central nervous system | 413 | 4 | 0.95 (0.31, 2.89) | − 0.38 (− 29.60, 8.82) | 6 | 1.54 (0.56, 4.23) | 2.59 (− 10.43, 10.30) |

| Generalized convulsion | 246 | 2 | 0.84 (0.17, 4.17) | − 0.70 (− 41.82, 6.44) | 3 | 1.36 (0.29, 6.40) | 0.96 (− 20.88, 7.15) |

| Respiratory system (acute respiratory distress syndrome) | 1108 | 5 | 0.41 (0.17, 0.98) | − 10.46 (− 64.81, − 0.07) | 5 | 0.45 (0.17, 1.19) | − 8.66 (− 63.27, 2.12) |

| Acute diabetes complications | 2595 | 12 | 0.38 (0.20, 0.75) | − 40.74 (− 144.04, − 5.92) | 23 | 0.94 (0.56, 1.58) | − 1.61 (− 28.01, 13.07) |

| Hypoglycemia | 1918 | 8 | 0.39 (0.17, 0.93) | − 29.77 (− 140.76, − 0.94) | 19 | 1.26 (0.69, 2.31) | 3.99 (− 12.83, 15.97) |

| Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome | 958 | 5 | 0.45 (0.15,1.34) | − 7.82 (− 68.25, 3.14) | 4 | 0.43 (0.14, 1.37) | − 8.49 (− 77.80, 3.33) |

| CoronaVac | |||||||

| Overall adverse events of special interest | 4792 | 79 | 0.77 (0.59, 1.00) | − 30.59 (− 83.27, 0.16) | 60 | 0.77 (0.58, 1.02) | − 30.72 (− 86.70, 1.94) |

| Autoimmune disease | 987 | 18 | 0.68 (0.40, 1.15) | − 9.09 (− 39.63, 3.49) | 20 | 0.84 (0.52, 1.34) | − 3.68 (− 23.84, 6.69) |

| Narcolepsy | 646 | 12 | 0.51 (0.27, 0.98) | − 12.65 (− 52.88, − 0.16) | 15 | 0.77 (0.45, 1.32) | − 4.00 (− 23.92, 4.73) |

| Acute aseptic arthritis | 322 | 6 | 2.72 (1.00, 7.42) | 3.05 (− 0.01, 7.67) | 4 | 1.69 (0.58, 4.94) | 1.96 (− 6.51, 7.07) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 3768 | 55 | 0.82 (0.59, 1.13) | − 12.00 (− 45.73, 7.77) | 41 | 0.86 (0.61, 1.20) | − 9.13 (− 42.66, 11.22) |

| Heart failure | 1752 | 20 | 0.93 (0.52, 1.66) | − 1.10 (− 19.48, 8.51) | 11 | 0.84 (0.44, 1.60) | − 2.82 (− 26.90, 8.06) |

| Coronary artery disease | 2068 | 19 | 0.58 (0.34, 0.98) | − 15.71 (− 56.47, − 0.37) | 21 | 0.78 (0.48, 1.26) | − 5.97 (− 31.04, 6.05) |

| Arrhythmia | 1791 | 35 | 1.10 (0.71, 1.70) | 2.32 (− 14.15, 14.13) | 17 | 0.76 (0.45, 1.31) | − 8.11 (− 42.54, 8.02) |

| Circulatory system | 3569 | 34 | 0.62 (0.42, 0.91) | − 22.60 (− 64.20, − 2.88) | 31 | 0.69 (0.47, 1.00) | − 16.48 (− 51.73, 0.09) |

| Thromboembolism | 3352 | 33 | 0.62 (0.42, 0.92) | − 21.48 (− 62.17, − 2.44) | 30 | 0.71 (0.48, 1.04) | − 14.53 (− 48.57, 1.75) |

| Hemorrhagic disease | 463 | 7 | 0.94 (0.24, 3.66) | − 0.31 (− 27.34, 6.27) | 2 | 0.19 (0.03, 1.38) | − 19.41 (− 321.64, 2.37) |

| Hepato-renal system | 926 | 10 | 0.78 (0.38, 1.58) | − 1.83 (− 17.95, 4.09) | 2 | 0.22 (0.05, 0.90) | − 22.72 (− 198.27, − 0.35) |

| Acute kidney injury | 715 | 5 | 0.91 (0.33, 2.47) | − 0.25 (− 11.60, 3.48) | 0 | NA | NA |

| Acute pancreatitis | 220 | 3 | 0.93 (0.28, 3.13) | − 0.20 (− 16.18, 4.26) | 3 | 0.78 (0.23, 2.63) | − 0.79 (− 20.55, 3.89) |

| Nerves and central nervous system | 479 | 8 | 0.78 (0.35, 1.74) | − 1.98 (− 21.69, 4.92) | 6 | 0.67 (0.29, 1.58) | − 3.37 (− 28.88, 4.25) |

| Bell's Palsy | 204 | 8 | 1.13 (0.48, 2.64) | 0.72 (− 11.42, 6.66) | 5 | 0.88 (0.34, 2.29) | − 0.83 (− 20.75, 6.04) |

| Respiratory system (acute respiratory distress syndrome) | 1135 | 5 | 0.34 (0.12, 0.95) | − 14.73 (− 88.04, − 0.23) | 11 | 0.98 (0.52, 1.85) | − 0.16 (− 11.64, 5.78) |

| Acute diabetes complications | 2871 | 32 | 0.74 (0.47, 1.14) | − 9.35 (− 37.76, 4.22) | 21 | 0.68 (0.42, 1.09) | − 12.32 (− 46.27, 2.73) |

| Hypoglycemia | 2137 | 22 | 0.68 (0.39, 1.17) | − 8.76 (− 39.31, 3.73) | 16 | 0.76 (0.45, 1.30) | − 5.66 (− 30.92, 5.84) |

| Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome | 1053 | 15 | 1.22 (0.67, 2.21) | 1.92 (− 7.81, 8.82) | 7 | 0.65 (0.28, 1.53) | − 5.71 (− 42.29, 5.61) |

Adjusted IRR was obtained from conditional Poisson regression adjusted for seasonal effect from self-controlled case-series analysis

IRR incidence rate ratio, CI confidence interval, NA not available

Five sensitivity analyses were performed and they did not reveal a significantly increased risk of individual AESIs or acute diabetic complications after the first or second dose of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccination (ESM Tables 3–7). Subgroup analysis based on HbA1c <7% and ≥7% also did not show a significantly excess risk of each class of AESI and acute diabetic complications after vaccination (ESM Table 8).

Discussion

Our current territory-wide study provided reassuring data on the safety of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac for the diabetic population, which could help to minimize vaccine hesitancy among this population at risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes. We did not observe any significant increase in the risk of AESI in patients with T2DM after either BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccination. Furthermore, regarding glycemic control, the two vaccines were not associated with a heightened risk of acute diabetic complications. For infrequent outcomes, we cannot rule out the possibility of false negatives due to insufficient power of the current study. Nonetheless, since the number of incidences after vaccination was small, the absolute risk increments were minute, even if the relative risks were statistically significant.

Some conditions included in the list of AESIs, such as thromboembolism and acute pancreatitis, may be more commonly seen in individuals with T2DM, as suggested by previous studies [37, 38]. Hence, it is highly relevant to evaluate the risk of these AESIs associated with COVID-19 vaccination. The present study did not identify any significant increased risk of AESI in vaccinated individuals with T2DM, which is in line with previous large-scale studies in the general population that confirm the safety of the vaccines [10, 11]. Meanwhile, there have been growing concerns over the heightened risks of thromboembolism after COVID-19 vaccination. The excess risk of thromboembolic events was identified in another COVID-19 vaccine, ChAdOx1 [23], and a previous study suggested that free DNA in the vaccine might have potentially induced antibodies against platelet factor 4, thereby activating platelets and causing immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia [39]. Since COVID-19 vaccines are of different technology platforms, whether enhanced platelet activation observed in ChAdOx1 would be reproduced in BNT162b2 and CoronaVac requires further elucidation. Indeed, a large-scale SCCS study showed increased risk of arterial thromboembolism after BNT162b2 vaccination [12], while several population-based cohort studies reported no association between BNT162b2 and thromboembolic events [10, 11, 23, 25], revealing that current evidence remains largely inconclusive. In this study, patients with T2DM were not shown to be associated with higher risks of thromboembolic events after COVID-19 vaccination. Since our study is the first large-scale analytic study on the safety of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with T2DM, further studies are still needed to confirm our findings.

The incidence of myocarditis after BNT162b2 vaccination in healthy male adolescents was reported in multiple studies [13, 40], but such an association was not observed in our T2DM cohort. Although current evidence does not explain the increased risk of myocarditis in young males, age appears to play an important role because cases were mainly observed in a younger (i.e. 12–24 years) age group [41]. It has been hypothesized that mRNA vaccines could trigger an intense immune response in a small subgroup of vulnerable adolescents, and asymptomatic infection of COVID-19 is more prevalent in young people, hence resulting in a higher incidence of post-vaccination systemic inflammatory response, which may subsequently lead to myocarditis [42]. This possibly explains why an increased incidence of myocarditis was not demonstrated in the current study because our population is generally older and subjects are less susceptible to immune-mediated myocarditis.

Apart from AESI, it is crucial to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 vaccines on the glycemic control of patients with T2DM, so as to clarify concerns raised by previous case reports regarding the possibility of COVID-19 vaccine disrupting glucose homeostasis and worsening glycemic control [5] that resulted in acute diabetic complications, even in patients who had good glycemic control at baseline [43, 44]. In the present study, an increased incidence of hypoglycemic episodes, diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycemic syndrome was not detected among the vaccinated individuals. It was hypothesized that vaccination that mimics natural infection may trigger systemic inflammatory response, causing hyperglycemia [44]. Whether this hypothesis fully explains fewer hypoglycemic events in the current study is unknown. Nonetheless, in a Chinese study that recruited healthy volunteers to receive two doses of inactivated COVID-19 vaccine from another manufacturer, a consistent rise of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was noted by day 28 regardless of the vaccination schedule [45]. A downtrend in HbA1c was observed afterwards, yet the value was still higher after 3 months when compared with baseline [45]. Therefore, long-term follow-up is deemed necessary to determine whether the effect of vaccine on HbA1c is transient or clinically significant, and future studies in larger populations that received BNT162b2 and CoronaVac are anticipated. Since only events that led to hospitalization were taken into consideration, we could not rule out the possibility that some patients experienced mild or self-limiting hypo- or hyperglycemia after vaccination. However, severe post-vaccination acute complications that require inpatient management are unlikely. Additional studies are warranted to investigate the effect of COVID-19 vaccines on diabetic control.

This study has several strengths. First, the evidence on the safety profile of the COVID-19 vaccine, in particular CoronaVac, among the diabetic population was limited, and this study addressed a novel research question. Second, the vaccination records covering the whole population in Hong Kong was officially provided by the Government, conferring high reliability and population representativeness. Our database also included the laboratory parameters so we could evaluate the safety profile of COVID-19 vaccine in different levels of HbA1c. Third, given a very low infection rate of COVID-19 (12,168 COVID-19 cases as of 31 January 2022 in the Hong Kong population of around 7.5 million) [46], the impact from COVID-19 and its complications on our observation of the safety of vaccines should be minimal. Fourth, several sensitivity analyses were conducted to ensure the robustness of the results. Given the very low number of mortality events in the observation period after COVID-19 vaccination, and similar results in sensitivity analysis, including patients with mortality, the third assumption of SCCS analysis was less likely violated in this study.

Nevertheless, there were a few limitations in this study. First, the present study may not have sufficient statistical power to detect very rare events. Ideally, this study should be repeated in a larger population of DM patients. Second, our database only captured patients who have ever utilized public health services under the HA. It is possible that some DM patients who were managed in the private sector and have never attended clinics under the HA were not included in the current study. However, it was reported that more than 90% of the DM patients were managed under the HA because public healthcare is heavily subsidized by the government [47] and more than 70% of hospitalizations were admitted to public hospitals [48]. Furthermore, this limitation does not affect SCCS analysis as it is an intrasubject comparison. Third, bias may arise from underdiagnosis or misclassification since the outcome events were defined by diagnosis coding. However, coding accuracy of the current electronic health database has been demonstrated by previous studies as the diagnosis codes had high positive predictive values [32]. Fourth, our cohort only included patients with T2DM diagnosed on or before 23 February 2021, and thus patients with newly diagnosed T2DM after the inclusion period were not captured in this study. Lastly, we could not eliminate the possibility that some events occur after 21 days post vaccination. This will be elucidated with longer-term monitoring for adverse events after vaccination among DM patients.

Conclusions

Patients with T2DM were not found to be associated with elevated risks of AESI and acute diabetic complications within 21 days after BNT162b2 or CoronaVac vaccination. We cannot rule out the possibility of false negatives due to insufficient power of the current study for a few rare disease outcomes. However, given the low incidence of rare disease outcomes after vaccination, the absolute risk increment was likely minimal. Since T2DM is a known risk factor for poor outcome associated with COVID-19, the proven benefits of COVID-19 vaccination in the diabetic population still outweigh its potential risks. Ongoing safety surveillance of the vaccines is warranted.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge a research grant from the Food and Health Bureau, The Government of the HKSAR (ref. no. COVID19F01); Members of the Expert Committee on Clinical Events Assessment Following COVID-19 Immunization for case assessment; and colleagues from the Drug Office of the Department of Health, and the HA for providing vaccination and clinical data. They also thank Ms Cheyenne Chan for administrative assistance.

Declarations

Authors’ Contributions

EYFW, CSLC and ICKW had the original idea for the study, contributed to the development of the study, extracted data from the source database, constructed the study design and the statistical model, reviewed the literature, and act as guarantors for this study. EYFW, WX and VKCY undertook the statistical analysis. EYFW, AHYM and ICKW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ICKW is the principal investigator and provided oversight for all aspects of this project. CSLC, AHYM, FTTL, XL, CKHW, EWYC, DTWL, KCBT, IFNH, CLKL and GML provided critical input to the analyses, design and discussion. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the analysis, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted

Funding

This regulatory pharmacovigilance study was initiated by the Department of Health, HKSAR. The Food and Health Bureau of the HKSAR government provided funding for this study. The sponsor of this study was involved in the study design and data collection via the Department of Health. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and took final responsibility for the decision to submit this study for publication.

Conflicts of interest

EYFW has received research grants from the Food and Health Bureau of the Government of the HKSAR, and the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (RGC), outside the submitted work. CSLC has received grants from the Food and Health Bureau of the Hong Kong Government, Hong Kong RGC, Hong Kong Innovation and Technology Commission, Pfizer, IQVIA, and Amgen, and personal fees from Primevigilance Ltd, outside the submitted work. FTTL has been supported by the RGC Postdoctoral Fellowship under the Hong Kong RGC and has received research grants from the Food and Health Bureau of the Government of the HKSAR, outside the submitted work. EWYC reports honorarium from the HA and grants from the Hong Kong RGC, the Research Fund Secretariat of the Food and Health Bureau, the National Natural Science Fund of China, Wellcome Trust, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, Amgen, Takeda, and the Narcotics Division of the Security Bureau of HKSAR, outside the submitted work. XL has received research grants from the Food and Health Bureau of the Government of the HKSAR; research and educational grants from Janssen and Pfizer; internal funding from the University of Hong Kong; and consultancy fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, unrelated to this work. CKHW reports receipt of the General Research Fund, RGC, Government of HKSAR, and EuroQol Research Foundation, all outside the submitted work. IFNH has received speaker’s fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme. ICKW reports research funding outside the submitted work from Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, Janssen, Bayer, GSK, Novartis, the Hong Kong RGC, the Hong Kong Health and Medical Research Fund, National Institute for Health Research in England, European Commission, and National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia, and has also received speaker’s fees from Janssen and Medice in the previous 3 years. He is also an independent non-executive director of Jacobson Medical in Hong Kong. Anna Hoi Ying Mok, Wanchun Xu, Vincent Ka Chun Yan, David Tak Wai Lui, Kathryn Choon Beng Tan, Ivan Fan Ngai Hung, Cindy Lo Kuen Lam, and Gabriel Matthew Leung have no known conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Hong Kong/HA Hong Kong West Cluster (UW21-149 and UW21-138) and the Department of Health Ethics Committee (LM21/2021).

Consent to participate and consent for publication

Consent from participants was not required as this study extracted anonymous data from an electronic health database under Hong Kong regulations and approval from the HA and the Department of Health.

Availability of data and material

Data will not be available for others as the data custodians have not given permission.

Code availability

The modified SCCS for investigating event-dependent exposure was conducted using the R function ‘eventdepenexp’ in the R-package ‘SCCS’. The R code will not be shared as it contains information about the dataset that is confidential.

Footnotes

Full professors: Kathryn Choon Beng Tan, Ivan Fan Ngai Hung, Cindy Lo Kuen Lam, Gabriel Matthew Leung and Ian Chi Kei Wong.

Eric Yuk Fai Wan and Celine Sze Ling Chui contributed equally to this article as co-first authors.

References

- 1.Apicella M, Campopiano MC, Mantuano M, Mazoni L, Coppelli A, Del Prato S. COVID-19 in people with diabetes: understanding the reasons for worse outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(9):782–792. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang I, Lim MA, Pranata R. Diabetes mellitus is associated with increased mortality and severity of disease in COVID-19 pneumonia—a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priority groups for coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccination: advice from the JCVI, 2 December 2020. 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/priority-groups-for-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-advice-from-the-jcvi-2-december-2020/priority-groups-for-coronavirus-covid-19-vaccination-advice-from-the-jcvi-2-december-2020

- 4.Nguyen KH, Srivastav A, Razzaghi H, Williams W, Lindley MC, Jorgensen C, et al. COVID‐19 vaccination intent, perceptions, and reasons for not vaccinating among groups prioritized for early vaccination—United States, September and December 2020. Wiley Online Library; 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Edwards AE, Vathenen R, Henson SM, Finer S, Gunganah K. Acute hyperglycaemic crisis after vaccination against COVID-19: A case series. Diabet Med. 2021;38(11):e14631. doi: 10.1111/dme.14631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prasad A. COVID 19 vaccine induced glycaemic disturbances in DM2-A Case Report. World J Adv Res Rev. 2021;10(3):149–156. doi: 10.30574/wjarr.2021.10.3.0247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barsha SY, Haque MMA, Rashid MU, Rahman ML, Hossain MA, Zaman S, et al. A case of acute encephalopathy and non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction following mRNA-1273 vaccination: possible adverse effect? Clin Exp Vacc Res. 2021;10(3):293. doi: 10.7774/cevr.2021.10.3.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanriover MD, Doğanay HL, Akova M, Güner HR, Azap A, Akhan S, et al. Efficacy and safety of an inactivated whole-virion SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac): interim results of a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial in Turkey. Lancet. 2021;398(10296):213–222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01429-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein NP, Lewis N, Goddard K, Fireman B, Zerbo O, Hanson KE, et al. Surveillance for adverse events after COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. JAMA. 2021;326(14):1390–1399. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.15072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barda N, Dagan N, Ben-Shlomo Y, Kepten E, Waxman J, Ohana R, et al. Safety of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide setting. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(12):1078–1090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2110475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hippisley-Cox J, Patone M, Mei XW, Saatci D, Dixon S, Khunti K, et al. Risk of thrombocytopenia and thromboembolism after Covid-19 vaccination and SARS-CoV-2 positive testing: self-controlled case series study. BMJ. 2021;374:n1931. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mevorach D, Anis E, Cedar N, Bromberg M, Haas EJ, Nadir E, et al. Myocarditis after BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine against Covid-19 in Israel. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(23):2140–2149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richard C, Wadowski M, Goruk S, Cameron L, Sharma AM, Field CJ. Individuals with obesity and type 2 diabetes have additional immune dysfunction compared with obese individuals who are metabolically healthy. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000379. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marfella R, Sardu C, D’Onofrio N, Prattichizzo F, Scisciola L, Messina V, et al. Glycaemic control is associated with SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections in vaccinated patients with type 2 diabetes. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-30068-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sardu C, Marfella R, Prattichizzo F, La Grotta R, Paolisso G, Ceriello A. Effect of hyperglycemia on COVID-19 outcomes: vaccination efficacy, disease severity, and molecular mechanisms. J Clin Med. 2022;11(6):1564. doi: 10.3390/jcm11061564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marfella R, D'Onofrio N, Sardu C, Scisciola L, Maggi P, Coppola N, et al. Does poor glycaemic control affect the immunogenicity of the COVID-19 vaccination in patients with type 2 diabetes: the CAVEAT study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24(1):160–165. doi: 10.1111/dom.14547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, Pollard AJ, Larson HJ, Teerawattananon Y, et al. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet. 2021;397(10278):1023–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00306-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Solís Arce JS, Warren SS, Meriggi NF, Scacco A, McMurry N, Voors M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Med. 2021;27(8):1385–1394. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01454-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitaker HJ, Paddy Farrington C, Spiessens B, Musonda P. Tutorial in biostatistics: the self-controlled case series method. Stat Med. 2006;25(10):1768–1797. doi: 10.1002/sim.2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weldeselassie YG, Whitaker HJ, Farrington CP. Use of the self-controlled case-series method in vaccine safety studies: review and recommendations for best practice. Epidemiol Infect. 2011;139(12):1805–1817. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811001531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie Y, Jabagi MJ, Botton J, Bertrand M, Baricault B, Drouin J, et al. A modified self-controlled case series method for event-dependent exposures and high event-related mortality, with application to COVID-19 vaccine safety. Stat Med. 2022;41(10):1735–1750. doi: 10.1002/sim.9325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson CR, Shi T, Vasileiou E, Katikireddi SV, Kerr S, Moore E, et al. First-dose ChAdOx1 and BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccines and thrombocytopenic, thromboembolic and hemorrhagic events in Scotland. Nat Med. 2021;27(7):1290–1297. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01408-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patone M, Handunnetthi L, Saatci D, Pan J, Katikireddi SV, Razvi S, et al. Neurological complications after first dose of COVID-19 vaccines and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27(12):2144–2153. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01556-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jabagi MJ, Botton J, Bertrand M, Weill A, Farrington P, Zureik M, et al. Myocardial infarction, stroke, and pulmonary embolism after BNT162b2 MRNA COVID-19 vaccine in people aged 75 years or older. JAMA. 2022;327(1):80–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.21699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wan EYF, Chui CSL, Wang Y, Ng VWS, Yan VKC, Lai FTT, et al. Herpes zoster related hospitalization after inactivated (CoronaVac) and mRNA (BNT162b2) SARS-CoV-2 vaccination: A self-controlled case series and nested case-control study. Lancet Reg Health-West Pac. 2022;21:100393. doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sing CW, Tang CTL, Chui CSL, Fan M, Lai FTT, Li X, et al. COVID-19 vaccines and risks of hematological abnormalities: nested case-control and self-controlled case series study. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(4):470–480. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singhal A, Ross J, Seminog O, Hawton K, Goldacre MJ. Risk of self-harm and suicide in people with specific psychiatric and physical disorders: comparisons between disorders using English national record linkage. J R Soc Med. 2014;107(5):194–204. doi: 10.1177/0141076814522033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Census and Statistics Department. Thematic Household Survey Report No. 58. Hong Kong; Census and Statistics Department; 2015.

- 30.Li X, Tong X, Yeung WWY, Kuan P, Yum SHH, Chui CSL, et al. Two-dose COVID-19 vaccination and possible arthritis flare among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Hong Kong. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81(4):564–568. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wan EYF, Chui CSL, Lai FTT, Chan EWY, Li X, Yan VKC, et al. Bell's palsy following vaccination with mRNA (BNT162b2) and inactivated (CoronaVac) SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a case series and nested case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00451-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wong AY, Root A, Douglas IJ, Chui CS, Chan EW, Ghebremichael-Weldeselassie Y, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes associated with use of clarithromycin: population based study. BMJ. 2016;352:h6926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h6926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. COVID-19 Vaccines: Safety Surveillance Manual - Module: Establishing active surveillance systems for adverse events of special interest during COVID-19 vaccine introduction. 2021 [cited 30 Sep 2021]. https://www.who.int/vaccine_safety/committee/Module_AESI.pdf

- 34.CDC COVID-19, Team R. Allergic reactions including anaphylaxis after receipt of the first dose of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine—United States, December 14–23, 2020. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(2):46–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Further expansion of COVID-19 vaccination arrangements from January 1. 2021. https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/202112/24/P2021122400509.htm

- 36.Petersen I, Douglas I, Whitaker H. Self controlled case series methods: an alternative to standard epidemiological study designs. BMJ. 2016;354:i4515. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell EJ, Folsom AR, Lutsey PL, Selvin E, Zakai NA, Cushman M, et al. Diabetes mellitus and venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2016;111:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Girman C, Kou T, Cai B, Alexander C, O’Neill E, Williams-Herman D, et al. Patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus have higher risk for acute pancreatitis compared with those without diabetes. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12(9):766–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greinacher A, Thiele T, Warkentin TE, Weisser K, Kyrle PA, Eichinger S. Thrombotic thrombocytopenia after ChAdOx1 nCov-19 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(22):2092–2101. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2104840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diaz GA, Parsons GT, Gering SK, Meier AR, Hutchinson IV, Robicsek A. Myocarditis and pericarditis after vaccination for COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;326(12):1210–1212. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bozkurt B, Kamat I, Hotez PJ. Myocarditis with COVID-19 mRNA vaccines. Circulation. 2021;144(6):471–484. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.121.056135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Das BB, Moskowitz WB, Taylor MB, Palmer A. Myocarditis and pericarditis following mRNA COVID-19 vaccination: what do we know so far? Children. 2021;8(7):607. doi: 10.3390/children8070607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mishra A, Ghosh A, Dutta K, Tyagi K, Misra A. Exacerbation of hyperglycemia in patients with type 2 diabetes after vaccination for COVID19: report of three cases. Diabetes Metabol Syndrome. 2021;15(4):102151. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2021.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee HJ, Sajan A, Tomer Y. Hyperglycemic emergencies associated with COVID-19 vaccination: a case series and discussion. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5(11):bvab141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Liu J, Wang J, Xu J, Xia H, Wang Y, Zhang C, et al. Comprehensive investigations revealed consistent pathophysiological alterations after vaccination with COVID-19 vaccines. Cell Discov. 2021;7(1):1–15. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00329-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centre for Health Protection (CHP). Latest situation of cases of COVID-19 (as of 30 September 2021). Hong Kong: Department of Health; 2021.

- 47.Lau IT. A clinical practice guideline to guide a system approach to diabetes care in Hong Kong. Diabetes Metab J. 2017;41(2):81. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2017.41.2.81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Census and Statistics Department. Thematic Household Survey Report No. 58. Census and Statistics Department; 2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.