Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic affected college students’ overall health. The aims of this qualitative inquiry were to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of the mind-body physical activity (MBPA) intervention and to explore the MBPA intervention experiences through the use of journals and photographs (photovoice) of a purposeful sample of 21 college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. An inductive qualitative process was used to explore the data that emerged from photovoice images and journals. Students’ experiences were encapsulated in 6 key themes: (1) holistic individual well-being; (2) physical activity as a matter of necessity; (3) mind-body physical activity intervention impacts; (4) broadening strategies for adapting and reacting; (5) systemic effect of stress management changes; and (6) perceiving causes of stress. Participants reflected collective intellectual, physical, and emotional fatigue as obstacles and perceived stress. The quality of COVID-19 related perspectives and stressful experiences are defined from traumatic and overwhelming to higher than normal. Findings from this study contribute to our understanding of the distinctive factors of the COVID-19 era among college students. Health educators should consider the implementation of multilevel and multicomponent MBPA interventions, and our findings highlight the utility of supporting higher education students in a meaningful way.

Keywords: stress, mind-body physical activity, health-intervention, photovoice, journaling, qualitative research, COVID-19, students

During COVID-19, college life suddenly changed, and students’ stress, depression, and anxiety levels increased.

Findings from this study contribute to our understanding of the distinctive factors of the COVID-19 era among college students. This qualitative inquiry contributes to the field by exploring personal experiences and critical factors that impact the development of an effective MBPA intervention to reduce stress and improve well-being using photovoice and journals among young adults.

Students indicated they want to learn strategies to alleviate stress, improve their health, and conquer their profound challenges on personal and institutional levels; they need time to manage overall health and processes for self-care. Our findings revealed that students want to learn more about stress alleviating strategies and MBPA intervention to support personal growth.

Introduction

COVID-19 stunned the world as it rippled through every country at the beginning of 2020; affecting all sectors of society, college life suddenly changed, and stress levels among students increased.1,2 In addition to the severe consequences, students’ depression, anxiety, and worries about health increased, and healthy behaviors such as physical activity (PA) decreased. 3 More than 64% of students reported life stress about personal health problems, and 74.8% experienced difficulties related to their loved ones, which interferes with mental health, and can be mitigated by a higher sense of well-being induced by regular PA.4,5

Mind-body physical activity (MBPA) combines ancient techniques.6,7 MBPA described as “yoga, tai chi, qigong, mindful walking, walking meditation, and physical practice, were developed in Eastern culture, in other words, with origins that lie outside of the Western culture” 7 (p. 2). Evidence shows that MBPA ameliorates stress. 8 College students believe that ancient practices are credible in affecting physiological and mental processes and improving overall health.9-11 Brief practices, such as 5 and 10 min (e.g., walking meditation vs sitting) and single sessions, have anxiolytic benefits and decrease stress. 12 Also, when experiencing psychosocial stress, a single 30-min laughter yoga session may protect the stress response as decreased salivary cortisol compared to a reading group.13,14 Additionally, one 60 min yoga session revealed a significant decrease in stress among college women when exposed to power and stretch yoga. 15 A 5-minute breathing exercise substantially reduced stress levels in the veterinary student while performing surgery on a live animal. 16 Further, a single-session loving-kindness meditation was more effective in inducing positive emotions in students who had no experience in meditative practices than compassion meditation and control conditions. 17

To manage stress, sensing physiological changes is vital. Life stresses are associated with mental disorders; thus, developing effective strategies to support mental health is critical. 4 College years are demanding, and the transition to young adulthood is a critical developmental phase that affects the community and society. 18 Lived experiences, narratives, and how college students describe stress during the COVID-19 are essential sources in developing effective interventions.

A qualitative inquiry that explores personal experiences can provide a more enhanced understanding of MBPA interventions. What is still needed is information about key factors that impact the development of an effective MBPA intervention to reduce stress and improve well-being. This study aimed to learn about students’ experiences using photovoice, journals, and a qualitative process to explore data by answering 3 research questions.

What are the lived experiences and key factors in the development of an effective, 10-min MBPA intervention to improve well-being and reduce stress among students during COVID-19?

What are the key themes arising from qualitative inquiries using photovoice and journals of an individual’s experience?

How do college students describe stress during COVID-19, and in what ways, if any, was the MBPA intervention helpful to young adults during stressful experiences?

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative action research method, photovoice methodology, and reflective journals were used in this study.19-22 Action research is closely associated with reflective practice, which can be used at a personal, professional, and organizational level; and it enables both researchers and participants to collaborate and ask vital questions of self and identity within and the organization.19-21 As such, qualitative action research is a “unique approach that focuses on practical problem-solving within a local context” including photo analysis and journals “to inform practice at the local level” 20 (p. 9). Photographs and reflective journals are frequently used approaches to collect data among qualitative action researchers in health education and PA.20,22,23 Photovoice as an innovative and interactive qualitative methodology, prompts participant-driven themes and allows participants to serve as “experts” on their “issues” and use the language of photos to express their needs and experiences.22,24

Journaling is an appropriate creative approach to encouraging reflection.21,25 The use of reflective journals is an educational method aimed at fostering student’s capacity to reflect on self-knowledge and feelings and perceived as a resource for exploring both participants and instructors alike.25,26 Journals allow participants to reflect on their individual lived experiences, explore potential growth, and gain an understanding of themself as college students during COVID-19. Therefore, qualitative action research using photovoice and reflective journals were well suited to explore students’ unique experiences, needs, and voices.

This project obtained approval from the University’s Institutional Review Board and written informed consent from the participants prior to the study initiation.

Participants

A purposeful sample (N = 21) of students enrolled in college classes for credits toward their graduation was recruited from a southwestern university in the United States. Due to the pandemic, online interactions were encouraged during the 2021 spring semester. Therefore, recruitment, time commitment, and the MBPA intervention were described to potential volunteers via emails and during initial online class meetings across campus. The inclusion as a participant in the study was based upon full time undergraduate or graduate student status. Overall, 25 students volunteered. Two participants asked the researcher to withdraw them from the study after accepting the MBPA Canvas class invitation due to contribution to other research projects in their program of study. Twenty-three participants completed the pre-intervention phase journals and the first module intervention activities. However, since some participants became unwell, only 21 were able to complete the study. The 21 students had a mean (SD) age = 21 (2.23) years, 24.52 (4.57) BMI, and 81% were female. The majority, 81% of the participants, were white, 9% Hispanic or Latino, and 5% Black or African American and Asian/Pacific Islander. Participants from all academic levels were well represented; 28% of the students were juniors, 24% were freshmen and seniors, 19% were sophomores, and 5% were of graduate/professional status (Supplemental Table 1). It was anticipated that the recruited sample provide the depth of data via journals and photovoice, and adequate experiences to achieve data saturation. 27

Intervention

To explore real-life connections as participants reflect upon their experiences, we have implemented a tailored MBPA course. The researcher, a certified instructor with over 35 years of experience, created the online class based on best practices using the asynchronous model. Participants had access to the pre-designed MBPA activities at any time and completed them at their own pace following the outlined 4 modules. 28 The intervention was delivered for 8 weeks, 3 times weekly via Canvas. The 24 sessions were conducted in 4 modules using core components rooted in ancient practices of traditional deep, diaphragm mindful breathing activities, yoga poses (asanas), breathing techniques (pranayama), qigong, martial art movements, walking activities, and loving-kindness walking meditation with present moment awareness.

The learning materials (videos, audio recordings) were built on each other, and participants submitted their narratives in sequence. The first module’s objective was to be aware of each breath and tailor the practice of the sensations of deep breathing while stimulating the diaphragm. The second module’s objective was to be continuously aware of each movement, using qigong, asanas, and martial arts, and tailor the sensations and feelings as we move. The third module’s objective was to be aware of each step and tailor each sensation leading to loving-kindness. The 4th module was built on ancient practices of loving-kindness, such as kind wishes toward self and others. In weeks 7 and 8, participants started to apply the content learned in previous sessions and practiced MBPA. Participants chose the environment for their practice in which they felt safe and chose when they sensed the intervention might alleviate stress.

Qualitative Data Collection and Instruments

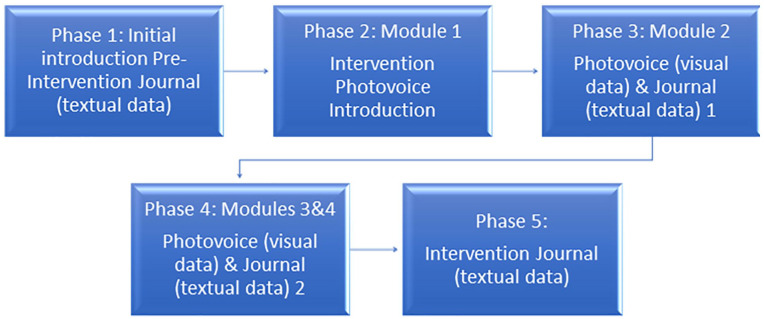

Data were collected online through assignments in the Canvas modules (Supplemental Table 2). A photovoice template was used to collect photographs and related reflections. A template for reflective journals was used to collect textual data. Previous investigators have found both to be an effective research tool: “Photovoice is a method by which people can identify, represent, and enhance their community” 22 (p. 369). Photovoice is a flexible photographic method using pictures to collect visual data in harmony with textual data. 22 Photographs are precise records for collecting data in a systematic way. 24 Data collection followed 5 phases (Figure 1). 29

Figure 1.

The visual synopsis of the data collection procedure.

Participants completed the pre-intervention journals to collect the first textual dataset. Identifying potential problems or ethical questions, such as including other people in the photograph, were addressed in phase 2. 22 Participants used their phones to complete their photovoice without taking pictures of other people in phases 3 and 4. In phase 5, students completed the final reflective journals. The online platform provided participants time, flexibility, and privacy to reflect on their experiences during the pandemic. Therefore, participants could choose a comfortable environment and space to write, take photos, and practice the intervention. 30

Data Analysis

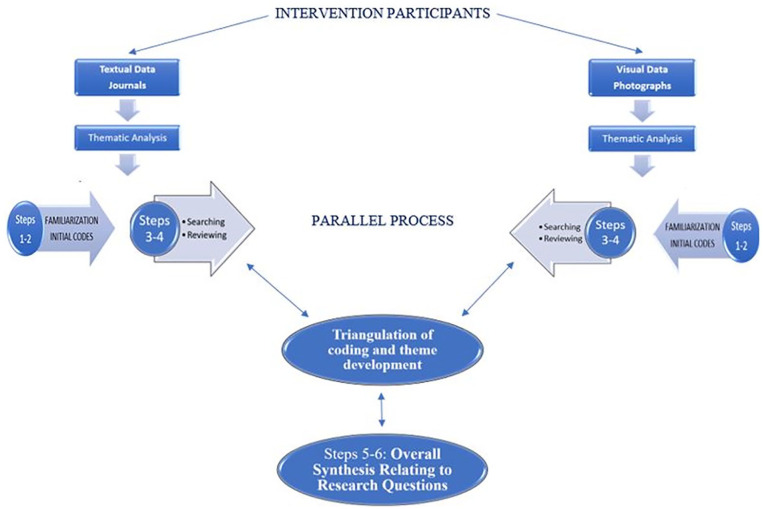

Data analysis followed a thematic analysis approach to explore college students’ lived experiences through textual and visual documents (Figure 2). 31 Given that the purpose of photovoice is to prompt participant-driven themes and have participants serve as the “experts on their ‘issues’, everyone used individual electronic journals to talk about their photos.” 22 Therefore, individual journaling contextualized the photographs. 32 Thematic analysis is a reflective qualitative analytic approach extensively used in health science.23,33 To answer the research questions and comprehend the experiences of each participant, the researcher used a general “data driven” inductive approach with an essentialist/realist epistemology. 34

Figure 2.

The visual synopsis of the data analysis procedure.

To examine and identify developing common themes and subthemes, researchers used line-by-line coding and constant comparison to keep the data of photos and related journal entries rooted in the participants’ language, narratives, and experiences. Triangulation of the coding and themes by a second researcher was tested using NVivo Pro (QSR International) for the coding and theme development to improve validity.

Results

To use photovoice authentically, participants described the significance of their photographs. Participants added 50 photographs across 2 photovoice journals of the environment where they chose to carry out the MBPA activities and completed over 1300 journal prompts. Examining students’ experiences blending reflective journals with photovoice while living during COVID-19 presents rich data resulting in 6 themes (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of the Results, Briefing the Key Themes, Subthemes, and Frequency Numbers.

| Key theme | Subthemes | Quote examples | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Holistic individual well-being |

Making Connections and Interconnections

where participants experienced a sense of connecting with their bodies, family, and nature. |

I took a photo in my backyard because it was a nice close place and it was comfortable to me since it is familiar [. . .] safe and the people that have been in it makes me feel loved. I have many great memories with people I love in that yard [. . .] I would have gone to the beach if I could because I grew up there and it makes me feel very loving and calm. (P21) I felt more grounded and connected with my body. (P7) I was thinking about how I was grateful for my family and the outdoors and the earth. I felt grounded and clear-headed. (P5) I liked looking at the birds, clouds, and trees outside, feeling the ground under my bare feet, and the wind and sun on my skin. (P10) |

275 64 |

| Interoception and Being in the Moment by sensing psychological and physiological changes, such as heart rate are vital to maintaining well-being. | [. . .] as I am walking I also felt my heart moving at a slow pace and the tensions of my muscles sleep. (P2) I was able to understand my mind and my body and tell myself that I am doing enough and that I am good enough. I have struggled with being confident in my skin and the loving-kindness activities really helped that. The walking activities also allowed me to be actively present. (P4) The breathing exercises helped me reduce my heart rate and be calm. (P8) I often felt more present and able to think in a more rational way. (P10) |

62 | |

| Empowering the “Refresh Button” and Enhancing Productivity as they engaged with the intervention activities and narrated they focused on tasks better, enhanced productivity, and felt empowered, like using a “refresh button on a computer” (p. 19). | I felt a lot more capable of being able to handle the tasks I had to complete for the next day. I felt very good about myself and more relaxed and able to complete daily tasks. I was thinking about how I was going to manage the tasks I had to do the next day. I was thinking that I was going to be productive and my mind was more clear to be able to go to bed without anxiety. (P3) [. . .] have only felt empowered (P18) [. . .] I think I’ve gotten pretty good at focusing and clearing my mind always makes me so relaxed and feel like a can do anything. (P19) |

59 | |

| Safe and Familiar Diverse Environment in which participants chose different locations to complete the MBPA where they felt safe; familiar places were key to realizing the rejuvenating intervention effects. | I feel my room is a safe space and I feel like I’ve done this by creating areas with peaceful art that feel neat and organized. (P6) The environment during this activity was awesome. It was at the perfect temperature outside and it was also quiet on campus. It gave me chance to be in my thoughts while I was walking and gave me a chance with me, myself, and I. (P2) |

51 | |

| Innovation Impacts and Future Preventive Plans on how they self-identified preventive strategies and future plans to enhance and extend their well-being. | I feel better prepared when I start to have symptoms of depression and anxiety. I have tools in my box I can use rather than relying 100% on my medication. (P8) I can do it during finals week and also any time when I feel overwhelmed. (P17) I think it would be great to use in between homework assignments or right before a big exam. The brief mind body activity really does help to clear one’s head so that they are better able to focus on the task at hand. (P3) I think it would be very beneficial if work places or school included practices like this. (P19) |

39 | |

| 2. Physical Activity as a Matter of Necessity |

PA Behaviors and Actions

as participants described their current levels of activity, and how “critical for overall health” (P17) such behavior was. Whether their activities were team-oriented or solo, formal or informal, athletic in nature, or simply moving to music, participants related the essential importance of PA. |

I am a huge fan of physical activity. I admit at times it can be hard to prioritize, although I find it extremely rewarding and necessary. (P18) I have always been a big fan of the outdoors and sports. (P17) I think it’s essential for every individual to partake in, whether it be big or small. (P20) |

199 78 |

|

Positive Emotions

were induced as journal reflections documented, “it made me very happy” (P2), in addition to relief from physical discomfort. (P9 and P5) photovoice reveal that the intervention helped reflect toward others (Figure 4). |

I love being physically active. It has always been a huge part of my life and it makes me super happy. (P4) What I loved is when I said “may I be strong.” I felt the strength building inside of me each time I said it. (P8) It felt really nice. Despite the activities not being that active, I felt like I had more energy after doing them. Especially being able to do them in the sun made my day, the combination just makes you happy. (P13) |

67 | |

|

Physical Activity Constraints and Challenges

where participants wrote about how the transition to college decreased their PA. |

I for sure need to be more active. I love being active just between full time student and full time work it’s hard to find time or motivation. (P1) I wish that I still viewed physical activity in a positive light, I don’t know how to get back to that kind of mindset. Instead of being a fun stress reliever, physical activity is stressful to me because it means I have to stop studying or give up time doing things I enjoy. I also worry about if I am doing the physical activity correctly. (P7) [. . .] I can’t find the energy to do anything. I would love to feel the same that I did before. (P19) |

54 | |

| 3. MBPA intervention impacts |

Meaningful Positive Impacts and Contextual Experiences

as participants responded to this intervention to decrease stress and alleviated issues related to breathing after contracting COVID-19. |

I’ve never felt this type of relaxation in my life. (P2) It was really great!! The intervention was something I’ve never experienced before but I enjoyed how it made me feel. (P5) I feel good. Allowing myself to breathe in different ways and really focus on what my body is doing has helped me a lot. I had Covid in November, and since then, I have had days where I have difficulty getting a really good deep breath. The 4-7-8 breathing technique has already been helping me expand my range of deep breathing which I am grateful for [. . .] my breathing has gotten better. (P11) |

191 61 |

|

Self-observed Changes

were reported. Students narrated on positive changes, such as becoming a more patient and better person, spending less time on electric devices, being more aware of their surroundings, and focusing less on others’ judgment or opinion. |

My stress has decreased significantly. Having a structured intervention to use was very helpful and I feel as though it reduced my stress just enough to pull me out of a funk or prevent me from going into a tailspin. (P5) Was awesome [. . .] It’s given me time to make myself better as a person and has provide me with patience. (P2) [. . .] allowed me to move away from my screen and slow down. (P4) |

55 | |

|

Sleep Hygiene

is affected by the long hours dedicated to studying and working can lead to erratic sleep patterns. Participants notably had trouble sleeping and the intervention induced better sleep hygiene. |

I noticed that when I completed the intervention before bed, I was able to sleep better. (P3) They helped me [. . .] to feel less overwhelmed [. . .] fall asleep better if I was feeling anxious. (P10) I was noticing that it helped me relax at certain points when I really needed it, and also helped me sleep better. I did it before bed and it helped me wind down, and relax my mind a lot. (P12) |

43 | |

|

Purposeful Course & Research Comments

described how the effectiveness of the intervention helped. Despite the general overall reporting that indicates positive outcomes, a student did note that recording their responses could be stressful. |

It was needed for my wellbeing and it was a really great experience. (P5) [. . .] if I didn’t resonate with an activity, there was going to be a new one in a week or two! (P7) [. . .] thank you for helping reduce my stress in definitely one of the most stressful years of my life. (P19) I think that including videos was very helpful because sometimes I would be confused by the descriptions. (P16) Sometimes it stressed me out knowing how much I needed to keep track of. (P12) |

32 | |

| 4. Broadening strategies for adapting and reacting |

Brevity

and variety of intervention helped participants overcome stress as students completed 10 practices. |

[. . .] focus on my breathing has shown me that everything that I’m going to face in my life it going to be hard, but as long as I stay calm, I’ll be fine. (P2) [. . .] really helped me relieve stress in the short term and feel more grounded, almost like I was resetting my brain [. . .] I am interested in learning more about MBPA to manage my stress! I think that also after trying the different types of activities and taking time to reflect on my experiences I was able to better understand what activities I liked and why. (P7) The brevity of it is also really nice, its efficient and quick to stop for 10 minutes. (P5) |

185 52 |

| “Move My Body Gently. . .Relax into the Movement” as the intervention helped participants relax. |

I was able to release my storm of all consuming thoughts for a few minutes and just breathe and move my body gently. . . I was able to focus on my breath and really enjoy and relax into the movement. (P5) I was thinking that this would be very good for me and would give me a chance to relax when I really need it. (P12) |

45 | |

| “Slow Down and Breathe was Necessary” as all students noted that the semester was very stressful and using the breathing activities helped. |

I felt relieved. I have been incredibly stressed this semester so having that chance to finally be able to slow down and breathe was necessary. (P14) I really enjoy the breathing techniques and just being able to find some peace and quiet. I really needed that [. . .] it intentionally gave me time to relax and just literally take a deep breath. (P1) |

44 | |

|

Self-care

care is evidenced in the journals; the importance of having some time to relax and clear their head, to be calmer and more aware of themselves and others. |

I was able to get out and just relax for a little while. Just take time to clear my head [. . .] I really liked it, because it brought my attention to not just myself, but others around me. It also brought more focus to clearing my head during my walks. It made me feel calmer and loving towards myself and others around me [. . .] being more loving towards myself [. . .] It really helped me sort out my thoughts. (P9) | 44 | |

| 5. Systemic effect of stress management changes |

Evoking and Inducing Emotions

as students wrote how their emotions accompanied their learning experience. |

I loved the breathing activities because it has helped me a ton with my lungs after having Covid. The walking activities were good too, and I love the kindness module so far the most. (P11) | 104 59 |

|

Relationships and Companion

are fun and essential channels to find comfort and support. |

I did it [MBPA activity] with my friend because she is really close to me and we support each other a lot. (P4) I did it with my mom because she is the one that I have been having a hard time with recently. (P21) |

45 | |

| 6. Perceiving causes of stress |

COVID-19

reflected overwhelming experiences. Contracting COVID-19 resulted in stress and difficulties academically, financially, and physically. |

Intense. My husband and I’s apartment lease ended when COVID began, and my husband and I both got COVID [. . .] still have lingering effects from Nov (shortness of breath, distorted taste/smell). (P15) I’m not sure if anything can take away the trauma that I have been through. However, the activities we did in this research have helped me stay in the moment rather than worrying about the past or future. (P21) I also had Covid-19 the first week of the study [. . .] I don’t really have a lot of memory from that week because I had a bad fever and felt really out of it. (P6) I fell behind in school because my parents and sister were diagnosed with Covid and I had take care of them. (P8) I constantly stress about money and school and how I am going to be able to handle everything in a world that is not normal right now. (P12) |

96 35 |

| “Work, work, and more work” by collective stressful educational and work experiences are reflected through the journals. |

I am working full time it is hard to find the time. Since I just will come home and work on homework and watch lectures. (P19) I love being active just between full time student and full time work it’s hard to find time or motivation. (P1) |

33 | |

|

Time Constrains

were shared as multiple stressful experiences related to feeling lost, struggling to maintain productivity or finding time for self-care. |

I feel very lost and struggle to maintain productivity. (P14) I was so stressed about time, and couldn’t confidently say that I could put 10 minutes of my day toward myself. I was always thinking about school work and that I had to do more every day. (P4) |

28 |

Note. Numbers in Italics represent frequencies for each of the subthemes.

Holistic Individual Well-being

College students’ well-being is the keystone to success and focusing on the whole student is critical. To succeed in college and beyond depends on each student’s ability to nurture their mental and physical well-being.

The participants narrated how the intervention affected their well-being and reported feeling more grounded and focused. They reported understanding the impact of daily movement and connecting their new intervention with the lessons of their childhood as a form of personal growth. Students also reported a desire to implement intervention techniques post-study to increase well-being.

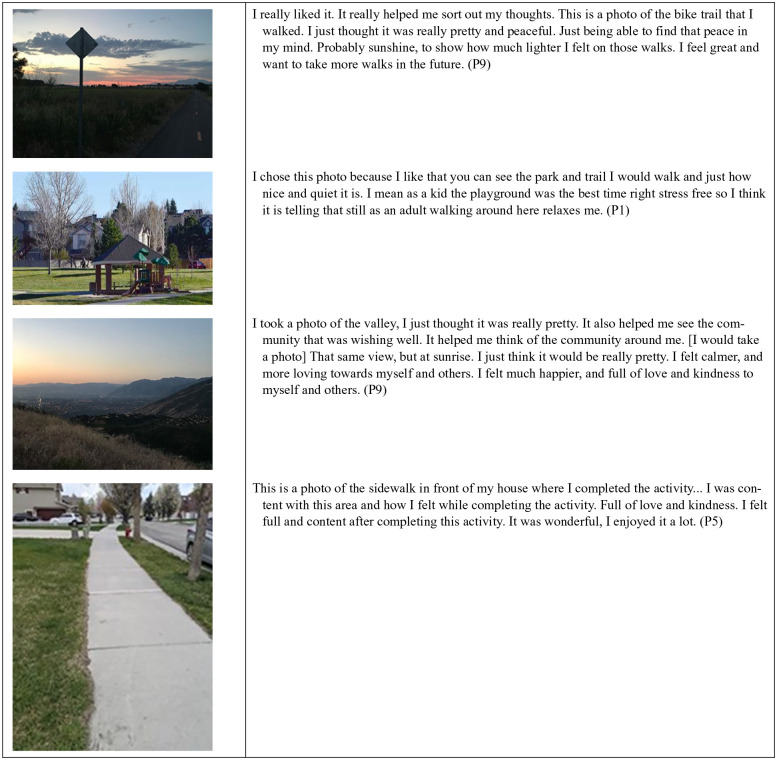

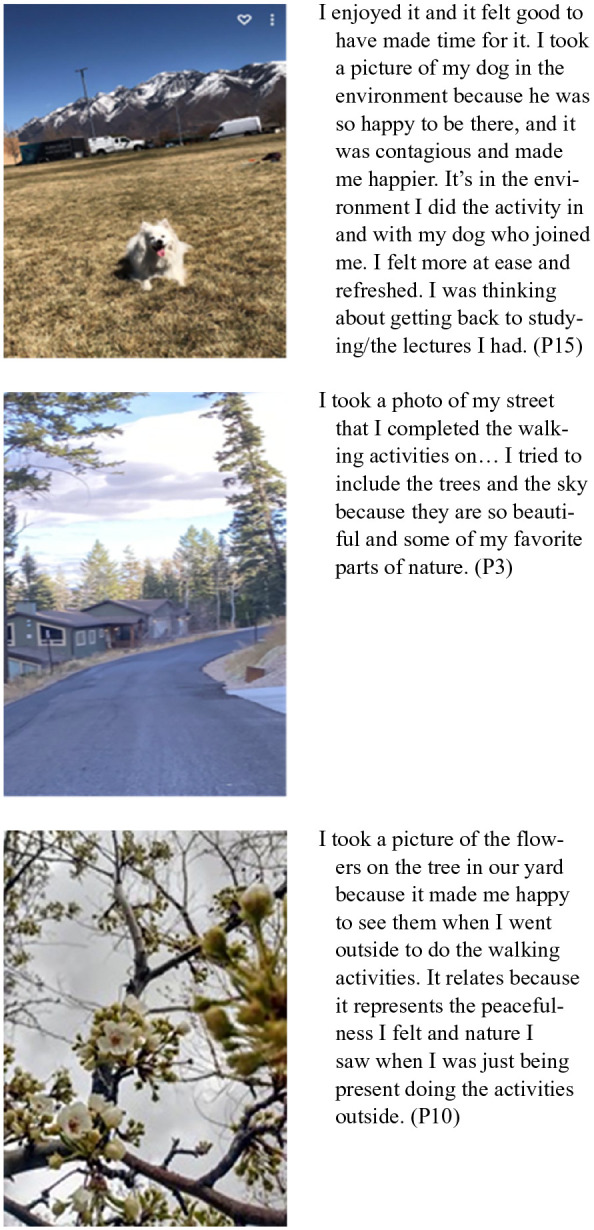

Further, photos allowed students to reflect on their experiences in a personal way, revealing their community and interests. Students did not always practice alone. The different environments affected the students’ paths, visual experiences, and emotional revelations; a supporting journal narrative is the participant’s voice (P15) represented by a journal entry with photograph in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Photovoice pictures by P15, P3, and P10.

These individual experiences revealed the complexity of the effects of COVID-19 on this student population in their personal and educational lives. For example, students reporting stress also reported muscle tension, physical discomfort, pain, and agitation. Stuck in an ongoing cycle of stress, students reported pains, weight gain, bloating, exhaustion, and agitation.

Further, some who practiced outdoors, reported becoming more compassionate toward [themselves], and found “hope of good being out in the world” (P8). Students tried to capture their feelings in photographs, as reflected in Figure 3 by P3 and P10.

PA as a Matter of Necessity

The participants noted the benefits of regular PA. Students reported that physical PA was important, but it was difficult to maintain optimal activity levels with normal levels of collegiate responsibility, and with the added burdens of the pandemic, any previous dedication to movement had declined precipitously. Intervention activities were a straightforward and natural path to increased PA. Students reported elevated energy and serenity. One student (P9) used an image of a bike trail at sunset to emphasize their written thoughts (Figure 4). Others related the essential importance of PA even as children (Figure 4 by P1). Their feelings weren’t simply directed inward: students’ (P9 and P5) photovoice reveal that the intervention helped them reflect toward others (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Photovoice pictures by P9, P1, and P5.

MBPA Intervention Impacts

Participants wrote unique narratives and took photos that reflected the meaningful positive impacts and contextual experiences, self-observed changes, sleep-hygiene, and course commentary as they completed the intervention. Some were ecstatic and energized about the intervention outcomes stating that they had never experienced this kind of relaxation before or had not had the tools before to cope with stress so successfully.

I am just grateful that I did this intervention. I am happy that I was introduced to these ways of coping with stress. (P11)

The authors of the photographs in Figure 4 reflect while completing the loving-kindness walking activities.

Broadening Strategies for Adapting and Reacting

Participants reflected on their thoughts, summarized their reactions to stressful situations, and identified specific coping strategies, such as focusing on breathing to stay calm, implementing a brief MBPA to transition between activities, refocus, or unwind: “I will just close my eyes and focus on my breathing until I am able to continue on with my day. YES!” (P5). In their own idioms: “I was able to get out of my head.” (P12). The activity also helped some participants to discern what activities they really liked and why.

Systemic Effect of Stress Management Changes

Many students reflected on how the intervention affected their life systemically and how much they appreciated being part of the project, which lowered the stress of being in college during the pandemic. They were proud of developing healthy habits and especially liked the loving-kindness module.

It made the stress of college, along with the pandemic, a lot easier to deal with [. . .] I have developed some healthy habits that I will try to stick with for the rest of my life. (P20)

Perceiving Causes of Stress

Finally, we discuss further how students perceived their causes of stress during COVID-19.

Discussion

This study set out, as a qualitative inquiry, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the MBPA intervention’s effectiveness and explore the experiences of college students during COVID-19. We used a qualitative process to identify key themes and participants’ perceived stress. To the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have examined MBPA using these methodologies. The discussion centers on our 3 research questions.

Lived Experiences and Key Factors

Students expressed that they gained strategies to enhance their well-being in a holistic way where short breaks for self-care and time for PA are necessary. Practicing the intervention helped students cope with the ripple effects of COVID, such as fear of infection, remote learning, isolation, fear of income loss, and suffering from trauma. Participants reflected on difficulties related to loved ones and anxiety about school, job interviews, and health conditions. Many worked in settings where they were often shorthanded. College students also experience challenges related to transitioning from parental care and high school, resulting in increased anxiety, stress, and depression. 1 Similarly, as participants described, they worried about school, health, jobs, and loved ones. Students reported trials and extenuated stress about health problems and finances. 4

The intervention helped participants build skills to cope with challenges by connecting with themselves, their loved ones, and their environments. As they chose familiar surroundings and companions, the intervention initiated an empowering experience, and a feeling of control, productivity, gratitude, and interconnectedness. These conclusions are consistent with other findings where a sense of connectedness and interconnectedness have vital benefits to enhancing well-being and academic performance. 35

Inactivity, work, schoolwork, and COVID-19 were most challenging, and the activities’ applicability and brevity helped students relax, sleep, and overcome stress. Although participants noted they value PA, they were unable to take care of themselves. Students reflected on how components of the MBPA (breathing, ancient movement, walking, and loving-kindness) promoted stress alleviating and coping strategies.

Having learned new techniques, participants experienced positive impacts that reduced anxiety, improved patience, positive emotions, focus, and sleep. Likewise, they voiced the importance of self-care, deep breaths, and frequent movement. Our findings reinforce that all 4 key components of MBPA are valuable in coping with students’ profound challenges. They learned strategies to recognize habitual internal trends and to respond appropriately.

Breathing techniques are considered core components of ancient practices. When people feel stressed, they breathe in a dysfunctional pattern. 36 Mastering how to breathe efficiently results in efficient oxygen metabolism. Learning deep, diaphragmatic, and 4-7-8 breathing can enhance breath awareness and adaptive strategies. 37 In our study, students learned new breathwork and narrated being more energized and less stressed. In the 4-7-8 activity after having COVID, students described improved breathing, which enhanced body awareness and evoked positive emotions. It also reduced depression and anxiety, and a 5-min breathing exercise substantially reduced stress. 16 Overall, students found it was necessary to use breathing techniques to reduce stress, enhance well-being, and promote relaxation.

Students described improved flexibility, reduced muscle tension, lower heart rate, and feeling strong as systemic health benefits. The walking and loving-kindness activities induced positive emotions, such as happiness, love, and gratitude toward self and others. Participants voiced they engaged in these activities longer and took breaks as needed more frequently. Similarly, photographs reflected an appreciation of the beauty of nature. Participants’ photos showed how companions and safe walks made them feel clear-headed and relaxed. Correspondingly, loving-kindness meditation has a meaningful impact on anxiety; however, the matched control group experienced increased anxiety. 38 Similarly, loving-kindness and PA revealed a substantial decrease in depression, stress, anxiety, and higher PA levels indicated better mood on the same and following days. 39 Participants described preventive plans to improve well-being; suggested teaching it to all incoming students as “[. . .] a free 1 credit course you should sign up for where you meet up and do these activities with other people.” (P10) and “I think practices like this could be taught to incoming freshmen to help handle stress.” (P16). The intervention can be both a mental and physical relief and a preventive opportunity to enhance productivity, connect, and reduce stress and distraction. Therefore, setting up areas across campuses where community members can practice and take necessary frequent short activity breaks as needed is recommended.

Key Themes Identified

The findings of 6 themes revealed the importance of PA and how the MBPA intervention impacted them. Participants reflected in their journals and photos on broadening strategies for adapting and reacting, the systemic effect of stress management changes, and how they perceived causes of stress. Themes connect through the paramount importance of a physically active lifestyle. All participants described that regular PA is a matter of necessity for well-being. However, due to time constraints, students can’t maintain their desired activity levels after starting college, and opportunities to be regularly physically active diminished. These observations are consistent with research that described structured, regular PA opportunities to maintain well-being diminish as young adults transition from high school to college as substantial physiological and psychological changes occur in this life stage. 6 Furthermore, inactivity increased during the pandemic worldwide while PA levels decreased. 40

Participants voiced that the activities were imperative to reduce stress. The frequent short activity breaks induced positive emotions, such as feeling healthy, connected to self and others, vigor, engagement, and loving-kindness. 41

As the participants progressed, their contextual experiences reflected the new techniques that decreased stress and found ways to deal with physical, emotional, and academic challenges. Therefore, the brevity, variety, sequence, and range of MBPA intervention activities contributed to the students’ experience, and they enjoyed trying new ones. Although participants reported overwhelming stress levels before they started the intervention, the perceived causes of stress were the least common theme. As they completed the 4 modules, they described enhancing well-being as the most common theme. Since students found strategies to deal with their profound encounters, they stayed engaged. From the MBPA perspective, walking can be quickly built into students’ schedules, and loving-kindness activities promote well-being. 12 Although loving-kindness education is generally explored as a single meditative intervention, researchers found that it promotes psychological health and decreases anxiety, stress, and depression while evoking positive emotions.17,38,41 Similarly, our participants reflected that the activities made them less stressed, and the environment played a vital role in their MBPA engagement.

Researchers discovered that the environment shapes PA, and natural spaces contribute substantially to well-being. 42 Likewise, students in this research appreciated the quality of their experience practicing the intervention freely. Safety and familiarity were the essential contributors regardless of being indoors or outdoors. Students reflected that natural green and blue spaces contributed to stress reduction in addition to the MBPA activity. The link between environment and PA, such as walking without harmful effects, is well established. 43 Further, participants freely chose their partners for the activity. They described that those relationships are essential channels for feeling comforted, supported, and having a sense of belonging as positive emotions which enhance productivity.

Perceived Stress During COVID-19

Academic pressure substantially contributes to psychological health as the brain is still developing well into the 30s.6,43 Our findings are meaningful, given that transition to young adulthood and college is critical and COVID-19 affects this developmental phase.

Our exploration of the perspective of students’ lived experiences is an opportunity to enhance well-being in college. Academic and social stressors contribute to mental health.44-46 In this study, 62% of the students were working, and some were working in the hospital, where they were often shorthanded. Our results reflected collective intellectual, physical, and emotional fatigue.

Contracting the virus, worrying, and caring for loved ones resulted in substantial stressors. Participants noted that distance learning presented physical, emotional, and academic challenges, such as time constraints, discomfort from being sedentary, and feeling isolated and overwhelmed, although online interventions support students through the pandemic. 47 Stress manifests itself as muscle tightness that can affect nutritional habits, leading to fatigue, pain, agitation, and physical and emotional discomfort. Our intervention provided personal resources to take short breaks to move, relax, slow down, and breathe.

Students wrote about the newfound skills and personal resources they learned (e.g., managing aches and pain, gaining confidence, and feeling empowered) and strategies (e.g., moving gently, relaxing, and breathing) as they progressed. In turn, these experiences enhanced holistic well-being. In our study, students investigated internal bodily sensations, such as feeling bloated, weight gain, muscle tension, and reduced heart rate. And they were connecting with natural sources, such as feeling the sun and wind on the skin. Therefore, students were externally and internally self-aware to identify these sensations and regulate these interoceptive signals. Furthermore, these perceptions of personal resources evoked positive emotions.

It is an individual and institutional responsibility to learn about strategies to sustain well-being and enhance professional and personal growth within the community. 48 Young adults need to learn strategies they can apply to balance their well-being to reap the benefits of college and self-manage life stressors with personalized education. 43 Furthermore, our findings suggest that the COVID-19 crisis caused trauma that affected everyone differently.

Young adults want to study strategies to alleviate stress, improve their health, and conquer their profound challenges on personal and institutional levels. 49 Participants responded that they need time to manage physical health and strategies for self-care, such as breaks, PA, and sleep hygiene.44,46 Our findings revealed that students want to learn more about stress alleviating strategies and MBPA intervention to support personal growth.

Physical activity-based multicomponent, multidisciplinary, and personalized interventions, where participants gain tools for managing stressors and regulating well-being by optimal stress reduction, are of societal importance. 18 Students voiced that MBPA activities should be taught to incoming first-year students and be included in all syllabi to decrease stress.

Strengths and Limitations

Several limitations warrant further discussion. First, students wrote about their photos instead of discussing them in interviews. However, writing about the photographs may promote deeper reflection. Second, photovoice is generally used as a participatory method, with students discussing their photos in focus groups; however, this was difficult to do during COVID-19. Given that time constraints were reported, being flexible may encourage richer expressions. Third, the asynchronous online design of the intervention provided an online modality of learning, and some participants may have desired in-person interaction. Furthermore, it is imperative to take the small sample size from one institution into consideration as a limitation to the study.

Conclusion

This study examined the importance of holistic individual well-being, PA’s necessity, how college students perceived stress, and the impact of the intervention. Overall, students described their lived experiences in Spring 2021 while practicing intervention 3 times weekly using journals and photovoice. Research findings have established the need for multilevel and multicomponent interventions that alleviate stress and enhance the well-being of the whole student.

Participants learned to alleviate stress and manage their challenges. Students shared that the MBPA activities helped them manage emergent challenges and recover. Therefore, we conclude that MBPA engagement is vital. These findings are novel in the literature though more research is needed.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580221126307 for “I Felt Grounded and Clear-Headed”: Qualitative Exploration of a Mind-Body Physical Activity Intervention on Stress Among College Students During COVID-19 by Ildiko Strehli, Donna H. Ziegenfuss, Martin E. Block, Ryan D. Burns, Yang Bai and Timothy A. Brusseau in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-inq-10.1177_00469580221126307 for “I Felt Grounded and Clear-Headed”: Qualitative Exploration of a Mind-Body Physical Activity Intervention on Stress Among College Students During COVID-19 by Ildiko Strehli, Donna H. Ziegenfuss, Martin E. Block, Ryan D. Burns, Yang Bai and Timothy A. Brusseau in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the students who participated in the study and all assistants who supported the data collection process.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Conceptualization, investigation, I.S, D.H.Z., M.E.B., R.D.B., Y.B., and T.A.B.; methodology, I.S. and D.H.Z.; formal analysis, I.S. and D.H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, I.S., D.H.Z., M.E.B., R.D.B., Y.B., and T.A.B.; project administration, I.S., R.D.B., and T.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Authors Declaration: The study obtained written informed consent from the subjects and was approved by the Institutional Review Board prior to study initiation.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board at University of Utah (protocol code: IRB # 139427).

ORCID iDs: Ildiko Strehli  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1127-2186

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1127-2186

Donna H. Ziegenfuss  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9981-5757

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9981-5757

Timothy A. Brusseau  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8234-3546

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8234-3546

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Aristovnik A, Keržič D, Ravšelj D, Tomaževič N, Umek L. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on life of higher education students: A global perspective. Sustainability. 2020;12(20):8438. doi: 10.3390/su12208438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fairlie R, Loyalka P. Schooling and Covid-19: lessons from recent research on EdTech. NPJ Sci Learn. 2020;5(1):13. doi: 10.1038/s41539-020-00072-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sañudo B, Fennell C, Sánchez-Oliver AJ. Objectively-assessed physical activity, sedentary behavior, smartphone use, and sleep patterns pre- and during-COVID-19 quarantine in young adults from Spain. Sustainability. 2020;12(15):5890. doi: 10.3390/su12155890 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karyotaki E, Cuijpers P, Albor Y, et al. Sources of stress and their associations with mental disorders among college students: Results of the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys International College Student Initiative. Front Psychol. 2020;11:1759. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jakicic JM, Kraus WE, Powell KE, et al. Association between bout duration of physical activity and health: Systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51(6):1213-1219. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Powell KE, King AC, Buchner DM, et al. The scientific foundation for the physical activity guidelines for Americans, 2nd Edition. J Phys Act Health. 2019;16:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Strehli I, Burns RD, Bai Y, Ziegenfuss DH, Block ME, Brusseau TA. Mind-body physical activity interventions and stress-related physiological markers in educational settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):224. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18010224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Capon H, O’Shea M, McIver S. Yoga and mental health: A synthesis of qualitative findings. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2019;37:122-132. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.101063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. MacLaughlin BW, Wang D, Noone AM, et al. Stress biomarkers in medical students participating in a mind body medicine skills program. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:1-8. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neq039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dawson AF, Brown WW, Anderson J, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Appl Psychol Health Well Being. 2020;12:384-410. doi: 10.1111/aphw.12188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Green OJ, Green JP, Carroll PJ. The perceived credibility of complementary and alternative medicine: A survey of undergraduate and graduate students. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2020;68(3):327-347. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2020.1756695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Edwards MK, Rosenbaum S, Loprinzi PD. Differential experimental effects of a short bout of walking, meditation, or combination of walking and meditation on state anxiety among young adults. Am J Health Promot. 2018;32(4):949-958. doi: 10.1177/0890117117744913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fujisawa A, Ota A, Matsunaga M, et al. Effect of laughter yoga on salivary cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone among healthy university students: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;32:6-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meier M, Wirz L, Dickinson P, Pruessner JC. Laughter yoga reduces the cortisol response to acute stress in healthy individuals. Stress. 2021;24(1):44-52. doi: 10.1080/10253890.2020.1766018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sullivan M, Carberry A, Evans ES, Hall EE, Nepocatych S. The effects of power and stretch yoga on affect and salivary cortisol in women. J Health Psychol. 2019;24(12):1658-1667. doi: 10.1177/1359105317694487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stevens BS, Royal KD, Ferris K, Taylor A, Snyder AM. Effect of a mindfulness exercise on stress in veterinary students performing surgery. Vet Surg. 2019;48(3):360-366. doi: 10.1111/vsu.13169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sirotina U, Shchebetenko S. Loving-kindness meditation and compassion meditation: do they affect emotions in a different way? Mindfulness. 2020;11(11):2519-2530. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Grasdalsmoen M, Eriksen HR, Lønning KJ, Sivertsen B. Physical exercise, mental health problems, and suicide attempts in university students. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):175. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-02583-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clark C. Carr and Kemmis’s reflections. J Philos Educ. 2001;35(1):85-100. doi: 10.1111/1467-9752.00211 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Johnson ES. Action research. In: Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. 2020. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9789190264093.013.696 [Google Scholar]

- 21. McIntosh P. Action Research and Reflective Practice: Creative and Visual Methods to Facilitate Reflection and Learning. Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369-387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Belon AP, Nieuwendyk LM, Vallianatos H, Nykiforuk CI. How community environment shapes physical activity: perceptions revealed through the PhotoVoice method. Social Sci Med. 2014;116:10-21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rose T, Shdaimah C, de Tablan D, Sharpe TL. Exploring wellbeing and agency among urban youth through photovoice. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2016;67:114-122. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.04.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Standal ØF, Moe VF. Reflective practice in physical education and physical education teacher education: A review of the literature since 1995. Quest. 2013;65(2):220-240. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2013.773530 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruiz-López M, Rodriguez-García M, Villanueva PG, et al. The use of reflective journaling as a learning strategy during the clinical rotations of students from the faculty of health sciences: an action-research study. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(10):e26-e31. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2015.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59-82. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Healy S, Colombo-Dougovito A, Judge J, Kwon E, Strehli I, Block ME. A practical guide to the development of an online course in adapted physical education. Palaestra. 2017;31(2):48-54. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nykiforuk CI, Vallianatos H, Nieuwendyk LM. Photovoice as a method for revealing community perceptions of the built and social environment. Int J Qual Methods. 2011;10(2):103-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches, 4th ed. SAGE; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Palibroda B, Krieg B, Murdock L, Havelock J. A Practical Guide to Photovoice: Sharing Pictures, Telling Stories and Changing Communities. Prairie Women’s Health Network; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Braun V, Clarke V. What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2014;9:26152. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v9.26152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Braun V, Clarke V, Weate P. Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In: Smith B., Sparkes A. C. (Eds.), Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. Routledge; 2016:191-205. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wahbeh H, Yount G, Vieten C, Radin D, Delorme A. Exploring personal development workshops’ effect on well-being and interconnectedness. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28(1):87-95. doi: 10.1089/jicm.2021.0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pandekar PP, Thangavelu PD. Effect of 4-7-8 breathing technique on anxiety and depression in moderate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients. International Journal of Health Sciences and Research. 2019;9(5):209-217. doi: 10.5535/arm.2019.43.4.509 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ma X, Yue ZQ, Gong ZQ, et al. The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Front Psychol. 2017;8:874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Totzeck C, Teismann T, Hofmann SG, et al. Loving-kindness meditation promotes mental health in university students. Mindfulness. 2020;11(7):1623-1631. doi: 10.1007/s12671-020-01375-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bai Y, Copeland WE, Burns R, et al. Ecological momentary assessment of physical activity and wellness behaviors in college students throughout a school year: Longitudinal naturalistic study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2022;8(1):e25375. doi: 10.2196/25375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bertrand L, Shaw KA, Ko J, Deprez D, Chilibeck PD, Zello GA. The impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on university students’ dietary intake, physical activity, and sedentary behaviour. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2021;46(3):265-272. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2020-0990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fredrickson BL, Boulton AJ, Firestine AM, et al. Positive emotion correlates of meditation practice: A comparison of mindfulness meditation and loving-kindness meditation. Mindfulness. 2017;8(6):1623-1633. doi: 10.1007/s12671-017-0735-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Iqbal A, Mansell W. A thematic analysis of multiple pathways between nature engagement activities and well-being. Front Psychol. 2021;12:580992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sideropoulos V, Midouhas E, Kokosi D, Brinkert J, Wong KK-Y, Kambouri MA. The effects of cumulative stressful educational events on the mental health of doctoral students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environmental 2021. doi:10.5522/04/16583861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wasil AR, Franzen RE, Gillespie S, Steinberg JS, Malhotra T, DeRubeis RJ. Commonly reported problems and coping strategies during the COVID-19 crisis: A survey of graduate and professional students. Front Psychol. 2021;12:598557. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.598557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wasil AR, Taylor ME, Franzen RE, Steinberg JS, DeRubeis RJ. Promoting graduate student mental health during COVID-19: acceptability, feasibility, and perceived utility of an online single-session intervention. Front Psychol. 2021;12:569785. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.569785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wasil AR, Malhotra T, Nandakumar N, et al. Improving mental health on college campuses: Perspectives of Indian college students. Behav Ther. 2022;53(2):348-364. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2021.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Liu C, McCabe M, Dawson A, et al. Identifying predictors of university students’ wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic: A data-driven approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18.(13): 6730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. World Health Organization. Promoting Mental Health Concepts, Emerging Evidence, Practice a Report of the WHO. Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse; 2005. who.int/publications/i/item/9241562943 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Taeymans J, Luijckx E, Rogan S, Haas K, Baur H. Physical activity, nutritional habits, and sleeping behavior in students and employees of a Swiss university during the COVID-19 lockdown period: Questionnaire survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(4):e26330. doi: 10.2196/26330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-inq-10.1177_00469580221126307 for “I Felt Grounded and Clear-Headed”: Qualitative Exploration of a Mind-Body Physical Activity Intervention on Stress Among College Students During COVID-19 by Ildiko Strehli, Donna H. Ziegenfuss, Martin E. Block, Ryan D. Burns, Yang Bai and Timothy A. Brusseau in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing

Supplemental material, sj-docx-2-inq-10.1177_00469580221126307 for “I Felt Grounded and Clear-Headed”: Qualitative Exploration of a Mind-Body Physical Activity Intervention on Stress Among College Students During COVID-19 by Ildiko Strehli, Donna H. Ziegenfuss, Martin E. Block, Ryan D. Burns, Yang Bai and Timothy A. Brusseau in INQUIRY: The Journal of Health Care Organization, Provision, and Financing