Abstract

Orbital inflammatory disease is a rarely reported complication of COVID-19 infection. We report a unique case of bilateral orbital myositis in a 12-year-old boy who tested positive for COVID-19 without typical systemic symptoms. Workup for other infectious and inflammatory etiologies was negative. After failing both oral and intravenous antibiotics, the patient was started on high-dose systemic steroids, with significant clinical improvement after 24 hours, thus confirming the inflammatory etiology of his presentation.

Case Report

A 12-year-old White boy with no prior ocular history presented emergently at the Greater Baltimore Medical Center with left eye pain, eyelid swelling, and bilateral periorbital erythema of 1 week’s duration. He had already completed a course of oral cefdinir and topical moxifloxacin, prescribed by outside providers for presumed preseptal cellulitis, without improvement. He reported mild periorbital pain but was otherwise at his normal healthy baseline and denied a decrease in vision, diplopia light sensitivity, or floaters. His corrected visual acuity was 20/25 in both eyes, with intraocular pressure of 11 mm Hg in each eye, full confrontation visual fields, and normal pupillary responses to light. Color vision was full in both eyes with Ishihara plates, and Hertel exophthalmometry confirmed no proptosis. Ocular motility testing demonstrated a −2 left supraduction deficit (Figure 1 ) and mild pain on abduction or adduction of either eye. External examination showed bilateral upper greater than lower eyelid edema and erythema. The remainder of the anterior segment and dilated fundus examination were normal.

Fig 1.

Findings on initial presentation including eyelid erythema and limited upgaze.

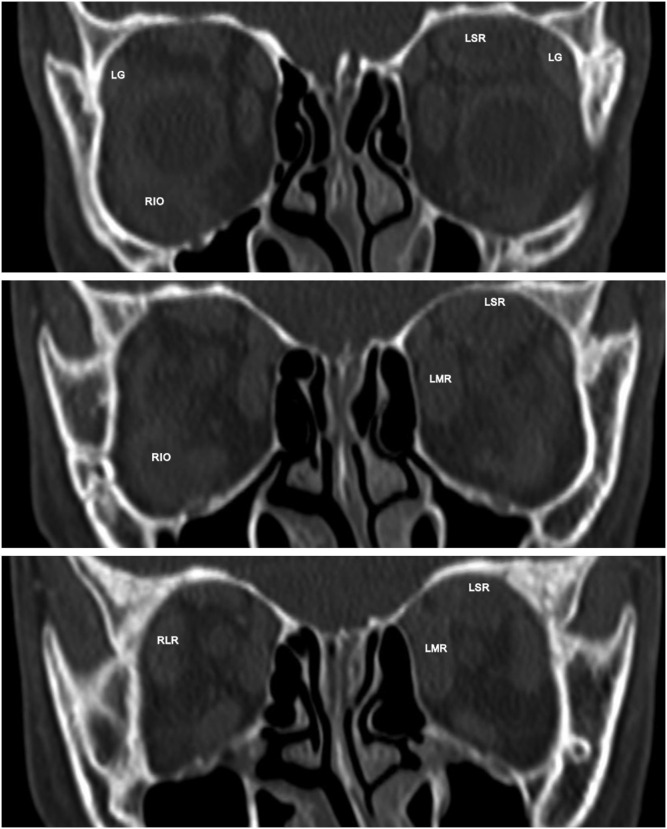

Computed tomography (CT) imaging of the brain and orbits showed enlargement of multiple extraocular muscles, including the right inferior oblique muscle, right lateral rectus muscle, left superior rectus muscle, and left medial rectus muscle (Figure 2 ). There was also enlargement of lacrimal glands bilaterally, without signs of sinus disease or orbital abscess.

Fig 2.

Computed tomography, coronal cuts from anterior (top) to posterior (bottom) demonstrating enlargement of the right inferior oblique (RIO), right lateral rectus (RLR), left superior rectus (LSR), left medial rectus (LMR) muscles, and bilateral lacrimal glands (LG).

Laboratory testing, including a complete metabolic panel and complete blood count, showed a hemoglobin of 11.4 g/dL (ref, 13.5-18.0), and C-reactive protein of 3.10 mg/dL (ref, <0.5) consistent with systemic inflammation. Blood cultures were negative. Thyroid testing, ANCA screening, and ACE levels were normal. He was found to be positive for COVID-19, without classic systemic symptoms.

His worsening eyelid redness and swelling despite oral antibiotics prompted admission by the internal medicine team for intravenous ampicillin-sulbactam and clindamycin. On day 3 of admission, after imaging and lab testing ruled out infection, the patient was given one dose of intravenous methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg, per ophthalmology recommendation, with significant improvement after only 24 hours. He was then discharged on oral prednisone 60 mg daily. One week after discharge, the patient’s symptoms had resolved, motility had returned to normal, and the oral prednisone was slowly tapered over 6 weeks without recurrence to date.

(See eSupplement 1, available at jaapos.org, for additional figures.)

Discussion

A thorough literature review demonstrated that the most common ophthalmic manifestations of COVID-19 have involved the anterior segment, posterior segment, and the neuro-ophthalmic pathway—rarely the orbit.1 To date, 3 reports have been published on COVID-19-related orbital inflammatory disease in children and young adults. The first included 2 separate cases of COVID-19-positive adolescents with painful unilateral eyelid swelling, and mild upper respiratory infection symptoms. CT imaging demonstrated sinusitis and fluid collections within the orbit, suggestive of orbital cellulitis, in addition to orbital or intracranial abscesses. Both patients were initially started on parenteral vancomycin and ceftriaxone, with little to no clinical improvement. The first patient was managed with an orbitotomy with drainage and subsequently demonstrated rapid clinical improvement with continued intravenous antibiotics and addition of metronidazole, nasal fluticasone, and oxymetazoline and topical tobramycin ointment. The second patient had near complete resolution of orbital findings after undergoing multiple endoscopic sinus drainage procedures and receiving intravenous vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and metronidazole as well as enoxaparin, hydroxychloroquine, zinc, vitamin C, thiamine, tobramycin ophthalmic ointment, and nasal fluticasone and oxymetazoline.2 The clinical course of both of these COVID-19 positive patients with orbital inflammation was more consistent with an infectious rather than an inflammatory etiology.

Another report discusses a 22-year-old healthy man diagnosed with right dacryoadenitis in the setting of COVID-19 that failed to improve with oral antibiotics but responded quickly to oral prednisone tapered slowly over 1 month.3 The third published report involves orbital myositis in a 10-year-old boy with periorbital swelling and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence of rectus muscle and lacrimal gland enlargement who tested positive for SARS-CoV2 in the absence of typical symptoms. This patient is most similar to the case presented here. He was prescribed oral prednisone 1 mg/kg/day tapered by 10 mg weekly and had clinical improvement within 2 days with resolution on MRI findings after 14 days.4

These 4 cases demonstrate orbital inflammatory responses in young patients, all of whom had mild to asymptomatic COVID-19 infections. The literature on adult COVID-19-related orbital myositis is also limited, with the main difference being a higher prevalence of classic COVID-19 systemic symptoms, such as fever, arthralgias, or myalgias.5 , 6

Orbital inflammatory disease is a rare phenomenon but has variable etiologies, including systemic inflammatory conditions, autoimmune disorders, infection and drug reactions.4 Various mechanisms have been proposed for COVID-19-triggered muscle inflammation. One possibility is direct viral entry via spike proteins attaching to ACE-2 receptors present on muscle tissue. This could promote transfer of genetic material into the cell via the viral envelope and host membrane coupling. It is also possible that, like other viruses causing myositis, COVID-19 may activate T-cell clonal expansion and increase the production of proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in muscle inflammation and damage.7, 8, 9Another proposed mechanism is autoimmunity due to molecular mimicry, with antibodies initially produced for host defense reacting with muscles, leading to a hyperinflammatory state with injury to myocytes.7 The significant response to steroids is similar to that seen in cases of idiopathic orbital inflammation (IOI). Steroid dosing for IOI, usually starting at 1/mg/kg/day of prednisone with slow taper over 6-8 weeks, can be used as a guide for treatment in COVID-19-related orbital inflammation as well.10

Although we cannot rule out the possibility that COVID-19 infection was coincidental rather than causative in this case, our case report highlights the possible occurrence of orbital inflammatory disease associated with COVID-19 in the absence of typical systemic symptoms.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Sen M., Honavar S., Sharma N., Sachdev M. COVID-19 and eye: a review of ophthalmic manifestations of COVID-19. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2021;69:488–509. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_297_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turbin R.E., Wawrzusin P.J., Sakla N.M., et al. Orbital cellulitis, sinusitis and intracranial abnormalities in two adolescents with COVID-19. Orbit. 2020;39:305–310. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1768560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martínez Díaz M., Copete Piqueras S., Blanco Marchite C., Vahdani K. Acute dacryoadenitis in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Orbit. 2022;41:374–377. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2020.1867193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eleiwa T., Abdelrahman S.N., ElSheikh R.H., Elhusseiny A.M. Orbital inflammatory disease associated with COVID-19 infection. J AAPOS. 2021;25:232–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jaapos.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Armstrong B.K., Murchison A.P., Bilyk J.R. Suspected orbital myositis associated with COVID-19. Orbit. 2021;40:532–535. doi: 10.1080/01676830.2021.1962366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mangan M.S., Yildiz E. New onset of unilateral orbital myositis following mild COVID-19 infection. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:669–670. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2021.1887282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saud A., Naveen R., Aggarwal R., Gupta L. COVID-19 and myositis: what we know so far. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2021;23:63. doi: 10.1007/s11926-021-01023-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalakas M.C. Guillain-Barré syndrome: The first documented COVID-19–triggered autoimmune neurologic disease: More to come with myositis in the offing. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2020;7:e781. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Megremis S., Walker T.D.J., He X., et al. Antibodies against immunogenic epitopes with high sequence identity to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with autoimmune dermatomyositis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020;79:1383–1386. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2020-217522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yeşiltaş Y., Gündüz A. Idiopathic orbital inflammation: Review of literature and new advances. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2018;25:71. doi: 10.4103/meajo.MEAJO_44_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.