Abstract

The nasopharynx is an integral component of the upper aerodigestive tract, whose morphologic features share an intimate relationship with a vast array of clinical, functional, and quality of life conditions related to contemporary humans. Its composite architecture and central location amidst the nasal cavity, pharyngotympanic tube, palate, and skull base bears implications for basic physiologic functions including breathing, vocalization, and alimentation. Over the course of evolution, morphological modifications of nasopharyngeal anatomy have occurred in genus Homo which serve to distinguish the human upper aerodigestive tract from that of other mammals. Understanding of these adaptive changes from both a comparative anatomy and clinical perspective offers insight into the unique blueprint which underpins many clinical pathologies currently encountered by anthropologists, scientists, and otorhinolaryngologists alike. This discussion intends to familiarize readers with the fundamental role that nasopharyngeal morphology plays in upper aerodigestive tract conditions, with consideration of its newfound clinical relevance in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: nasopharynx, nasal obstruction, sleep apnea, eustachian tube disorder

INTRODUCTION

The nasopharynx lies at the junction of the nasal cavity, basicranium, oropharynx, and parapharyngeal space and is a clinically important and anatomically complex region of the upper aerodigestive tract. Testament to its unique location at the apex of the crossroads of respiration and deglutition, the nasopharynx arises embryologically from both digestive and respiratory progenitors. An exclusively human characteristic is the postnatal change that occurs in and around the nasopharynx, merging pathways for respiration and deglutition. While this allows for unique human functions such as articulate speech, it also opens the door for clinically significant pathology such as aspiration and obstructive sleep apnea. As such, there is great clinical benefit in understanding the morphological and pathologic relationships of the nasopharynx and its surroundings. The nasopharynx is integral to nearly every aspect of the field of otorhinolaryngology, and as clinicians in this field, we aim to provide an overview of nasopharyngeal morphological correlates with clinical, functional, and quality of life conditions related to contemporary humans.

BOUNDARIES OF THE NASOPHARYNX

The nasopharynx, by definition, is an organ space behind the nasal cavity in the upper aspect of the throat (Wenig, 2015). From an evo-devo perspective, the boundaries of the nasopharynx did not arise from a single organ, but rather the evolutionary bricolage of several pharyngeal and branchial arch-derived structures (see Jankowski in this issue). Superiorly, its roof is characterized by mucosa covering the sphenoid and clivus; inferiorly, its floor is the soft palate; anteriorly; it is flanked by the nasal choanae; posteriorly, by the posterior pharyngeal wall, upper cervical spine, and associated prevertebral musculature; and laterally, by the pharyngobasilar fascia and medial pterygoid plates. All boundaries of the nasopharynx are bony except the floor, which can be manipulated by the soft palate (Mukherji and Castillo, 1998).

This soft tissue floor separating the nasopharynx from the oropharynx has functional implications. For example, during the pharyngeal stage of swallowing, elevation of the soft palate against the lateral and posterior walls of the pharynx effectively seals off the nasopharynx from the oropharynx to prevent bolus regurgitation and to assist with food propulsion (Goyal and Mashimo, 2006). Synergistic action of the palatopharyngeal sphincter closes off the pharyngeal isthmus between the nasopharynx and oropharynx, further limiting superior movement of the bolus. Structural abnormalities of the palate which inhibit velopharyngeal closure may impair resonant control of speech and contribute to nasal regurgitation, a condition called velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD). Discussion of this clinical entity occurs later in this text.

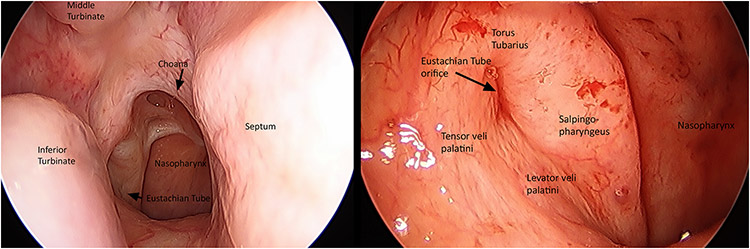

While all but the floor of the nasopharynx is bony, these boundaries are not imperforate. Notably, the lateral walls of the nasopharynx are host to an important communication with the middle ear space via the eustachian tube and its orifice, also named the pharyngotympanic tube, just below the level of the posteroinferior nasal concha (Figure 1). Normally, this tube remains closed as its proximal walls are collapsed. The cartilaginous end of the pharyngotympanic tube produces a mucosal prominence in the nasopharynx, named the torus tubarius. Mechanisms for control of tubal muscle function and concomitant middle ear aeration have been the focus of considerable investigation (Eden et al., 1990).

Figure 1:

Endoscopic endonasal view of the right posterior nasal cavity and nasopharynx. The nasal choanae are paired, fixed apertures in the posterior nasal cavity that delineate the rostral boundary of the nasopharynx. A closer look at the nasopharyngeal orifice reveals its intimate morphologic and anatomic relationship to the pharyngotympanic tube. Associated tubal structures and location of pharyngotympanic musculature are readily identified. Image provided courtesy of Dr. David Poetker.

Paratubal constrictor muscles, namely the tensor veli palatini (TVP), levator veli palatini (LVP), and tensor tympani, assist with pharyngotympanic function via periodic opening of the eustachian tube. Research indicates that the TVP is the main tubal dilator, while the LVP may provide minor assistance by provoking inward movement of the anterior tube near the torus (Doyle and Rood, 1979; Alper et al., 2012). Muscle fibers of the TVP course superiorly along the bony pharyngotympanic tube to become anatomically continuous with the tensor tympani muscle. For this reason, it is suggested the latter muscle may contribute to tubal dilation, though its precise role remains uncertain (Gannon and Eden, 1987). Morphologic variations, such as cleft palate, can disrupt muscle orientation and insertion sites of these muscles, often leading to inadequate middle ear ventilation and subsequent otic disease (Abe et al., 2004).

CLINICAL RELEVANCE OF NASOPHARYNGEAL MORPHOLOGY IN HUMANS

The central location of the nasopharynx within the head and neck confers to its osseous and soft tissue components crucial implications for human health and function including respiration, olfaction, phonation, hearing, and deglutition. The nasopharynx acts as a conduit for airflow through the nose and paranasal sinuses to the upper respiratory tract, but also to the pharyngotympanic tubes and middle ear. The nasopharynx is also an ecological reservoir for microorganisms. While we will not dwell on the microbiota of this region, its physical location in the central head and neck enables the dissemination of opportunistic pathogens to other nearby craniofacial structures. It is believed that nasopharyngeal flora informs, to a large extent, the microbiota of the paranasal sinuses, middle ear, and lower respiratory tract (Kang and Kang, 2021). It is implicated in the pathophysiology of many diseases including otitis media, rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinitis, asthma, and pneumonia (Ylikoski et al., 1989; Chi et al., 2003; Rawlings et al., 2013; Rodrigues et al., 2013).

Anatomic conditions involving the nose and nasopharynx, such as septal deviation, turbinate hypertrophy, nasal valve collapse, choanal atresia, and adenotonsillar hyperplasia often contribute to nasal airway obstruction by altering airflow dynamics and nasopharyngeal surface morphology (Hamdan et al., 2008; Yildirim et al., 2008; Ramsden et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2014). Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common disorder among both pediatric and adult humans, whose rising incidence poses a serious threat to public health (Gottlieb and Punjabi, 2020). The relationship between nasopharyngeal collapsibility and degree of airway resistance in subjects with sleep apnea is well-defined (Suratt et al., 1985). OSA is associated with significant reductions in quality-of-life metrics, impaired functional and work performance, and increased incidence of chronic cardiovascular disease (Al Lawati et al., 2009).

While a portion of clinical conditions related to nasopharyngeal boundaries are benign, there exist more concerning pathologies which originate from this region. The boundaries of the nasopharynx and their histopathologic distinction from the nasal cavity mark a watershed area for neoplasm distribution (Mills et al., 2000). Angiofibromas, rhabdomyosarcomas, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma almost entirely arise on the nasopharyngeal side, whereas sinonasal adenocarcinoma, inverted papillomas, pleomorphic adenomas, and pyogenic granulomas almost exclusively arise in the nasal cavity (Rodriguez et al., 2017). The following paragraphs discuss in greater detail human nasopharyngeal morphology and its association with common clinical pathologies currently treated by otorhinolaryngology and oromaxillofacial specialists.

1. Nasal and oral breathing

Over the course of evolution, morphological modifications of nasopharyngeal anatomy have occurred in genus Homo which serve to distinguish the human upper aerodigestive tract from that of other mammals (Laitman, 1977; Pagano et al., 2022). These adaptive changes play an important role in the evolution of breathing, vocalization, and alimentation. In most other mammalian species, the intranarial epiglottis is firmly seated above the soft palate; this arrangement deflects swallowed material over the tracheal airway and into the esophagus, allowing the ability to eat and breathe simultaneously (Laitman, 1977; Harrison, 1995). Human newborns, up until 3 to 4 months into development, possess this same intranarial system to suckle (Crompton et al., 2008). It is with age that the human external basicranial flexion increases and the caudal rim of the soft palate no longer interlocks with the intranarial epiglottis, permitting the formation of a common aerodigestive tract (Laitman, 1977).

Morphologic abnormalities which interfere with obligate nasal breathing among infants (i.e., choanal atresia) are then considered an acute otolaryngologic emergency in order to establish an airway (Murray et al., 2019). Choanal atresia is a congenital condition characterized by failure of the nasal fossae to recanalize in early fetal development. This embryologic deviation results in anatomic occlusion of either one or both nasal choanae by aberrant soft tissue, bone, or a combination of both. Unilateral choanal atresia rarely presents with infant respiratory distress and often goes undiagnosed until adulthood due to nonspecific symptoms of persistent nasal airway obstruction. In the case of bilateral choanal atresia, both nasal passageways are blocked causing profound respiratory distress, particularly when the mouth is closed in periods of quiet respiration, feeding, and sleeping. Given this, prompt surgical intervention is critical to restore choanal patency and safeguard the infant’s ability to breathe and feed as intended.

2. Velopharyngeal Dysfunction

Resonant control of speech and swallowing are complex processes highly dependent on the competency of velopharyngeal structures within the nasopharynx. Palatal musculature, including the TVP, LVP, superior pharyngeal constrictor, muscularis uvulae, palatopharyngeus, and palatoglossus forms a dynamic valve called the velopharyngeal sphincter, which is elevated during speech and swallowing to separate the nose from the mouth. When closure of the velopharyngeal sphincter is incomplete, velopharyngeal dysfunction (VPD) results. Patients with VPD show persistent hypernasal speech due to abnormal nasal emission, atypical articulation patterns, and involuntary nasal regurgitation of food and liquids. VPD, whether anatomic, neurologic, or learned in origin, has significant functional and psychosocial consequences for quality of life.

Velopharyngeal insufficiency is commonly encountered among the cleft palate (overt and submucous) population due to structural deficiencies which disrupt normal sphincter physiology. Palatal clefting alters pharyngeal muscle insertion and function, preventing the velum from adequately translating posteriorly to obtain an effective seal with the posterior and lateral aspects of the pharynx. The LVP muscle is the primary muscle responsible for velar elevation during speech and swallow. Its inserted position relative to the soft palate is a crucial factor for determining velopharyngeal competence. Muscular fibers from the LVP form a structural sling which occupies 50 percent of the velar length measured from the posterior nasal spine to the uvular tip. In infants born with cleft palate, the course and insertion of the LVP is markedly disorganized; the muscle fibers insert on the posterior nasal spine and medial margin of the bony cleft palate instead of forming a levator sling, inevitably resulting is isometric contraction of the muscle and abnormal velopharyngeal closure (Ha, 2007). Variances in the pathomorphology of the LVP muscle are well-described in the literature (Cohen et al., 1994; Koch et al., 1998). Lindman and Stal, in their laboratory, demonstrated that the LVP muscle of cleft patients lacked contractile mechanisms, had a greater density of connective tissue, and a significantly smaller diameter of muscle fibers compared to age-matched controls (Lindman et al., 2001). Cohen et al. also found that in some subjects, the LVP was nearly indistinguishable as a discrete muscle due to striking morphologic disorientation (Cohen et al., 1993). In surgical correction of cleft palate, proper repositioning of the LVP muscle is suggested to mitigate the persistence of postsurgical nasalized speech and nasopharyngeal reflux (Ha, 2007).

Removal of the tonsils and adenoid pad for pediatric patients with sleep disordered breathing or chronic nasal airway obstruction is indicated but may also have an impact on velar mechanisms. Adenotonsillectomy may enlarge the velopharyngeal orifice to an extent which precludes adequate sphincter closure (Pickrell et al., 1976), particularly among those with palatal clefting. Insufficient velar-adenoidal contact has implications for consideration of adenoidectomy in this cohort (Hubbard et al., 2010). However, even those without overt clefting may still develop VPD and hypernasal speech after removal of the tonsils and adenoids. The incidence of persistent VPD has been quoted between 1:1200 and 1:3000 following adenotonsillectomy and 1:10,000 following adenoidectomy (Witzel et al., 1986; Stewart et al., 2002). The complication of hypernasality in the post-operative period is often transient, but in rare instances the soft palate is unable to accommodate to this anatomic change over time, resulting in permanent VPD (Khami et al., 2015).

Aside from structural defects, velopharyngeal competence is also modulated by central neuronal systems. Postnasal upper respiratory tract (URT) control is dependent upon specific patterns of innervation of URT muscles by motoneurons of the nucleus ambiguus and hypoglossal nucleus (Friedland, 1993). Brainstem pathologies can interfere with direct innervation of the velum, or the coordination of the palatal and lingual musculature associated with normal vocalization. Such neurogenic insults are suggested to underlie some of the incoordination pathologies seen with VPD (Kummer et al., 2015).

3. Nasal Airway Obstruction

Nasal airway obstruction is a frequently encountered condition among otolaryngologists, particularly at our institution. For this report, we assessed our adult clinic volume over a 10-year span and identified 13,128 patients who were evaluated for anatomic causes of nasal obstruction. The vast majority of these, 69.4% (n=9112), had a deviated nasal septum. About half of these, 52.8% (n=4808) had concurrent inferior turbinate hypertrophy. Other anatomic findings causing nasal obstruction included isolated inferior turbinate hypertrophy (n=2118, 16.1%), or anterior nasal abnormalities such as nasal valve collapse or aperture stenosis (n=1898, 14.5%). These numbers attest to the high prevalence of anatomic abnormalities in the human nasal complex that can negatively impact nasal airflow through the nasopharynx. It was previously demonstrated by Rhee and colleagues, that corrective nasal valve surgery results in significant improvement in disease-specific quality of life and high satisfaction level (Rhee et al., 2005). However, less than 30% of the 13,128 patients seen in our clinics opted for surgical correction, which may reflect the unique adult human capability of alternatively breathing through the mouth. Evolutionarily, one might postulate that if adult humans remained obligate nose breathers, individuals with these anatomic conditions may have been physiologically less fit during metabolically demanding activities.

The consequences of nasal obstruction on elite athletes seeking peak metabolic performance has been studied previously (Benninger et al., 1992). While nasal patency does not directly interfere with aerobic capacity and athletic performance, it has been shown to indirectly impact the quality of life and peak performance of those who are affected (McIntosh et al., 2021). Decreased nasal patency disrupts sleep architecture, reduces ability to concentrate, and contributes to daytime somnolence, all of which compromise training and interfere with achieving peak physical fitness.

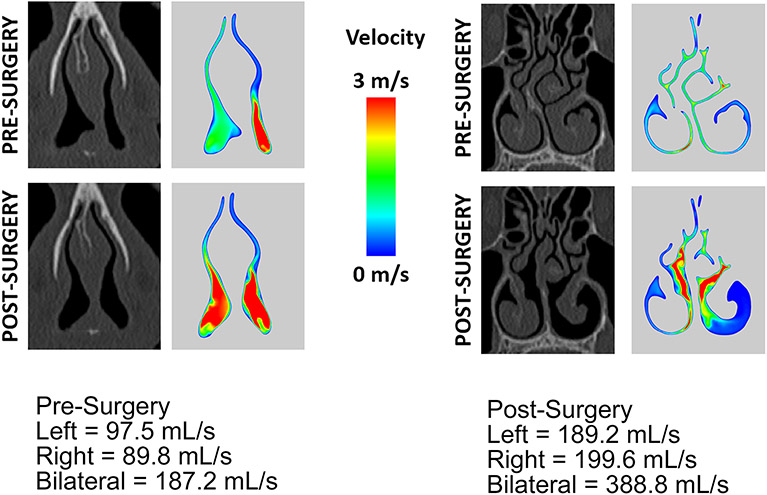

In the last decade, assessment of nasal airflow has shifted from unreliable and subjective measures to the objective characterization afforded by computational fluid dynamics (CFD) (Dayal et al., 2016; Garcia et al., 2016; Radulesco et al., 2019). CFD is a mathematical tool that only recently has become more readily available for the otolaryngologist and scientist to use in investigative practice (Garcia et al., 2016; Radulesco et al., 2019; Bastir et al., 2021). At our own institution, we have a research program dedicated to CFD simulation of nasal and pharyngeal airflow in patients with obstructive pathologies. For example, CFD analysis can characterize nasal airflow in patients with nasal airway obstruction, both before and after surgical intervention, and demonstrate how the anatomy of the nose directly impacts air flow velocity and symmetry (Figure 2).

Figure 2:

Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation of nasal airflow in a patient with nasal airway obstruction (NAO). Patient underwent septoplasty, rhinoplasty, and left inferior turbinate reduction. The Nasal Obstruction Symptom Evaluation (NOSE) score improved from 80 pre-surgery to 0 post-surgery. Image ‘A’ depicts a cross-section of the nasal turbinates to illustrate the difference in pre- and post-surgical nasal airflow with left inferior turbinate reduction. Image ‘B’ depicts a cross-section of the nasal valve to illustrate the difference in pre- and post-surgical nasal airflow with septoplasty and rhinoplasty. Image provided courtesy of Dr. Guilherme Garcia.

Malik and colleagues recently found that for patients suffering from empty nose syndrome, a debilitating condition associated with aggressive nasal airway surgery, restoring the spatial contour of the nasal cavity via inferior meatus augmentation correlates to improvements in both rhinologic and psychological symptoms of the disease, as well as nasal airflow redistribution as exhibited by CFD (Malik et al., 2021). Understanding the morphologic relationships between nasopharyngeal structure and patient-reported symptom perception, with the use of CFD modeling, may help broaden our understanding of airflow dynamics and their relation to anatomic causes of nasal airway obstruction.

4. Otitis Media and Eustachian Tube Dysfunction

Otitis media (OM) is defined as an infection of the middle ear space. Acute otitis media (AOM), aside from upper respiratory infection, is the second most commonly diagnosed disease entity among children worldwide. Peak incidence and prevalence occur during the first 2 years of life (Rettig and Tunkel, 2014) and roughly 80% of all pediatric patients will experience at least one case of OM (Schilder et al., 2016). Yet, AOM in adults is quite rare unless there are associated pathologies impacting eustachian tube dysfunction (e.g., nasopharyngeal carcinoma obstructing the eustachian tube aperture). This astounding difference in rate of middle-ear disease has been proposed to be, in part, the consequence of anatomic shifts related to the relative position of the pharyngotympanic tube across the human lifespan (Bluestone, 1996), though this area of subject is under debate.

The pharyngotympanic tube in adolescents and adults differs anatomically and physiologically from that infant and toddlers. In adulthood, it measures approximately 36 mm and descends from the tympanic cavity to the nasopharynx at a 45-degree angle from the sagittal plane (Bluestone, 2005a). The tube is hourglass shaped, displaying largest diameters at the pharyngeal orifice and nearing the tympanic cavity, and narrowing in size at the isthmus near the junction of the bony and cartilaginous components of the tube. Conversely, the pharyngotympanic tube in early childhood is only about half its adult length, descends in a more horizontal plan at an angle of approximately 10-degrees, and is relatively shorter with a smaller lumen area throughout (Bluestone, 2005b). These features in infancy can facilitate the seeding of nasopharyngeal bacteria into the middle ear space, increasing risk of infection.

Among anthropologists, is it suggested that predisposing factors to OM are correlated to our evolutionary past. Human newborns are born relatively early and with underdeveloped anatomic and immunophysiologic systems, compared to our primitive human ancestors and mammalian counterparts (Daniel, 1999; Bluestone, 2005b). Moreover, evolutionary adaptations to speech and loss of prognathism are postulated to have influenced angulation and caliber of the pharyngotympanic tube in such a way that predisposes to OM (Bluestone, 2008). However, these remarks are premised on the notion that pharyngotympanic anatomy is the sole determinant of susceptibility to middle ear disease, which is questionable and fails to incorporate various selective pressures which are known to impact function and dysfunction of the middle ear and host immune system. Little evidence exists to confirm that pharyngotympanic morphology is significantly altered in OM susceptible populations (Sade and Ar, 1997; de Ru and Grote, 2004). OM is not unique to humans; in fact, its prevalence is well documented in the veterinary community among domestic animals including dogs, cats, horses, pigs, and rabbits (Kahn and Line, 2010).

A number of studies have reported variation in prevalence of OM by ethnicity. While reviews do not necessarily agree on differences in propensity of OM between white, black, Hispanic or Asian children in the developed world, reliable data with sound methodological configuration has revealed significant discrepancies in OM among children of the indigenous Australian Aborigine (Boswell and Nienhuys, 1995; Gunasekera et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2009), the Native American (Maynard et al., 1972; Curns et al., 2002; Singleton et al., 2009), the Inuit (Maynard et al., 1972; Curns et al., 2002; Singleton et al., 2009) and the Maori (Giles and Asher, 1991; Gribben et al., 2012), when compared to their white counterparts. Socioeconomic disparities or healthcare seeking behaviors may contribute to this finding (Vernacchio et al., 2004), but the differences in OM incidence in indigenous groups remain profound despite controlling for sociodemographics. This suggests that host genetics may play a role in engendering intra-species diversification and genotypic variation regarding immunologic response. Identification of genetic loci that are associated with OM is an avenue of precision medicine which is currently under study and has shed light into potential disease mechanisms and novel therapeutic strategies for certain at-risk groups (Bhutta et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2017; Geng et al., 2019).

5. Snoring and obstructive sleep apnea

Snoring is a common, acoustic phenomenon generated as a result of airflow resistance within the upper aerodigestive tract, namely the nasopharynx. Turbulent airflow causes the soft tissues of the nasopharynx to vibrate and emit a perceptible sound. On the continuum of sleep-disordered breathing, snoring can be classified as heavy breathing, simple snoring, or obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). While the effects of isolated snoring on overall health remain poorly understood, the health, safety, and economic consequences of OSA are well documented (Al Lawati et al., 2009). OSA is defined by repetitive partial or complete impedance in airflow with resultant decrease in blood oxygenation levels due to collapse of the upper airway while asleep. Current estimates in population-based prevalence of OSA among adult Americans range from 6-17% and are rapidly increasing with the obesity epidemic (Senaratna et al., 2017). The primary etiology for OSA is related to upper airway tissue collapse during sleep, a process governed by passive anatomical factors and active neural control of pharyngeal muscle tone. Patients with OSA are more often overweight and have extrinsic fat accumulation in the parapharyngeal spaces, though there exists a unique subset of patients whose craniofacial morphology may predispose to apneic events due to secondary narrowing of the upper airway (i.e., mandibular hypoplasia, craniosynostosis, midface hypoplasia) (Shelton et al., 1993).

OSA has been observed since ancient times; the first historical record of it dated back to 460 BC. (Kryger, 1983). In 1965, the first polysomnograph recorded objective evidence of sleep apnea in humans, and since, the clinical condition of OSA has been investigated in several of our other mammalian counterparts (Jung and Kuhlo, 1965). Hendricks and colleagues realized the presence of mild OSA in English bulldogs, who are anatomically prone to sleep-related airway obstruction because of their large soft palate and smaller pharyngeal cross-sectional diameter (Hendricks et al., 1987). Lonergan et al. and Brennick et al. extended this work to female Yucatan miniature pigs and obese Zucker rats who demonstrated similar features in upper airway collapse during sleep (Lonergan et al., 1998; Brennick et al., 2006).

Upper airway obstruction at the level of nasopharynx is dictated by several osseous and soft tissue factors, among which hypertrophy of the nasopharyngeal tonsils (adenoids) is a key factor in the pathogenesis of upper airway obstruction in children (Greenfeld et al., 2003). Along with palatine and lingual tonsils, adenoid tissue constitutes a major part of ‘Waldeyer’s ring’, a lymphoepithelial aggregate of tissue strategically located in the nasopharynx with purposeful regional immune function. This tissue grows rapidly in the first 8 years of human development, relative to the total luminal area of the nasopharynx (Papaioannou et al., 2013). In consequence, children are more susceptible to nocturnal airflow restriction from nasopharyngeal narrowing.

Gold standard of therapy for OSA involves a combination of weight-based lifestyle modifications and non-invasive treatment modalities since the nasopharynx is an anatomically difficult area to expose. Nasal stents and positive airway pressure are at the forefront of treatment, the latter of which functions to pneumatically stent the upper airway during sleep.

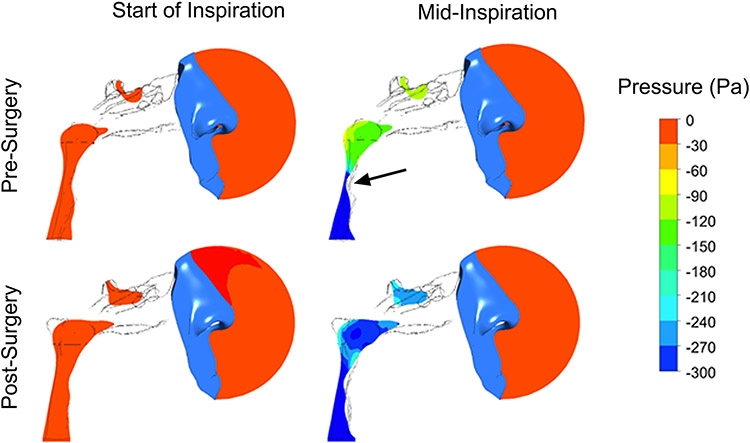

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices, however, are plagued by problems with long-term adherence, with many patients ultimately deserting the machine due to discomfort, claustrophobia, and poor nasal patency (Rotenberg et al., 2016). Research into surgical interventions for OSA was first pioneered in 1976 by Ikematsu, who developed the uvulopalatopharyngoplasty (UPPP) (Yaremchuk and Garcia-Rodriguez, 2017). UPPP is an operation designed to remove and rearrange redundant palatal tissues to increase airway size and decrease tissue collapse. Since its advent, multiple surgical approaches and combinations of this procedure have emerged, though with variable success rates. These include lingual tonsillectomy, maxillomandibular advancement, genioglossus advancement, hyoid suspension, hypoglossal nerve stimulation, and more. Animal models continue to advance our understanding of how various factors contribute to the pathogenesis of OSA, with hope to yield novel targets for OSA intervention (Kim et al., 2019). Furthermore, utilization of fluid-structure interaction (FSI) simulations of upper airway collapse in patients with OSA is a more recent branch of clinical research which analyzes pharyngeal air flow pressures before and after surgical intervention for OSA (Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Fluid-structure interaction (FSI) simulation of upper airway collapse in a patient with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) before and after maxillomandibular advancement (MMA). In the pre-surgery model, the pharynx is shown to have near-complete collapse during inspiration (arrow). In the post-surgery model, the degree of pharyngeal collapse during inspiration is significantly less compared to the pre-surgery model and dramatically improves proximal airway pressures. Image provided courtesy of Dr. Guilherme Garcia.

6. Nasopharyngeal Morphologic Implications in COVID-19 Testing

In the era of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, timely and reliable testing is essential for mitigating the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends collecting an upper respiratory specimen for initial testing, of which the nasopharyngeal swab is considered the gold standard owing to its diagnostic yield, moderate sensitivity, and high specificity (Lee et al., 2021; Tsang et al., 2021). Millions of people have been tested with the expectation that this process is relatively safe. However, recent literature suggests that nasopharyngeal swabs pose an increased risk of iatrogenic complications compared to less invasive swabs of the anterior nasal cavity or mid-turbinate (Koskinen et al., 2021). The most commonly reported complication of swabbing is epistaxis, though in rare instances patients have been treated for retained foreign bodies (i.e., portions of the swab device) or skull base injuries (i.e., cerebrospinal fluid leaks) after the test (Koskinen et al., 2021).

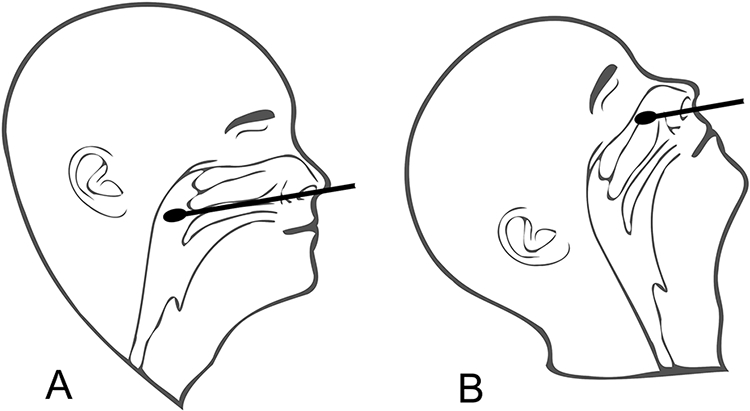

The CDC does not delineate an insertion depth for nasopharyngeal swabs, but instead recommends that the device be advanced until resistance is encountered corresponding to the posterior nasopharyngeal wall (Callesen et al., 2021). However, resistance can easily be met at any number of points prior to the nasopharynx due to the complex anatomy of the nasal airway. Intranasal variations among patients are common and may include septal deviations, septal spurs, neoplasms, or post-surgical augmentation of nasal tissue, all of which increase the technical challenge of a straightforward test. More so, misconstrued understanding of the anatomical relationship of the nostril, nose and pharynx may lead the operator to incorrectly insert the swab at an excessively cranialward angle. We have all seen pictures of people tilting their heads far back for testing which, in fact, increases the difficulty of following the nasal floor directly posteriorly to the nasopharynx (Figure 4). This causes discomfort to the patient, complications from encountering nasal structures, and a poor diagnostic test with low predictive value by failing to access the nasopharynx.

Figure 4:

Following the nasal floor with a head neutral position is the correct way to access the nasopharynx (A). A nasal swab, held at the same angle, but with the head tilted back, encounters nasal structures and ultimately the skull base leading to pain, complications, and a potentially poor diagnostic test (B).

In response to this, alternative sampling sites are being studied which utilize saliva, blood, urine, or feces. In their meta-analysis, Butler-Laporte and co-investigators found that the diagnostic sensitivity for salivary nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) closely mirrors that of the nasopharyngeal swab, and offers testing advantages such as ease of procurement, enhanced patient safety and comfort, and reduced occupational exposure for personnel collecting samples (2021). Prospective research in this area will help elucidate novel diagnostic targets for large-scale community-based testing and promote greater efficacy in a global public health response to this pandemic.

CONCLUSION

The nasopharynx is a distinct and critical component of the upper aerodigestive tract, whose evolution and morphological transformation over a human lifetime impacts a wide range of modern human functions, including respiration, phonation, hearing, sleeping, and deglutition. More recently, relevance of nasopharyngeal morphology to the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated implications for broad-scale testing, disease surveillance, and global prevention.

Acknowledgments

A portion of this manuscript was supported by OTO Clinomics, a project funded through the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin Endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin with support by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, Award Number UL1TR001436. The content is solely the responsibility of the author(s) and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors note no conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

LITERATURE CITED

- Abe M, Murakami G, Noguchi M, Kitamura S, Shimada K, Kohama GI. 2004. Variations in the tensor veli palatini muscle with special reference to its origin and insertion. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 41:474–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Lawati NM, Patel SR, Ayas NT. 2009. Epidemiology, risk factors, and consequences of obstructive sleep apnea and short sleep duration. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 51:285–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alper CM, Swarts JD, Singla A, Banks J, Doyle WJ. 2012. Relationship between the electromyographic activity of the paratubal muscles and eustachian tube opening assessed by sonotubometry and videoendoscopy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 138:741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastir M, Sanz-Prieto D, Burgos M. 2021. Three-dimensional form and function of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx in humans and chimpanzees. Anat Rec (see this issue). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benninger MS, Sarpa JR, Ansari T, Ward J. 1992. Nasal patency, aerobic capacity, and athletic performance. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 107:101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta MF, Thornton RB, Kirkham LS, Kerschner JE, Cheeseman MT. 2017. Understanding the aetiology and resolution of chronic otitis media from animal and human studies. Dis Model Mech 10:1289–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone CD. 1996. Pathogenesis of otitis media: role of eustachian tube. Pediatr Infect Dis J 15:281–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone CD. 2005a. Anatomy and Physiology of the Eustachian Tube System. In: Johnson JT, Newlands SD, editors. Head and Neck Surgery: Otolaryngology. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p 1253–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone CD. 2005b. Humans are born too soon: impact on pediatric otolaryngology. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 69:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluestone CD. 2008. Impact of evolution on the eustachian tube. Laryngoscope 118:522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell JB, Nienhuys TG. 1995. Onset of otitis media in the first eight weeks of life in aboriginal and non-aboriginal Australian infants. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 104:542–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennick MJ, Pickup S, Cater JR, Kuna ST. 2006. Phasic respiratory pharyngeal mechanics by magnetic resonance imaging in lean and obese zucker rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173:1031–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callesen RE, Kiel CM, Hovgaard LH, Jakobsen KK, Papesch M, von Buchwald C, Todsen T. 2021. Optimal Insertion Depth for Nasal Mid-Turbinate and Nasopharyngeal Swabs. Diagnostics (Basel) 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi DH, Hendley JO, French P, Arango P, Hayden FG, Winther B. 2003. Nasopharyngeal reservoir of bacterial otitis media and sinusitis pathogens in adults during wellness and viral respiratory illness. Am J Rhinol 17:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SR, Chen L, Trotman CA, Burdi AR. 1993. Soft-palate myogenesis: a developmental field paradigm. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 30:441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SR, Chen LL, Burdi AR, Trotman CA. 1994. Patterns of abnormal myogenesis in human cleft palates. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 31:345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crompton AW, German RZ, Thexton AJ. 2008. Development of the movement of the epiglottis in infant and juvenile pigs. Zoology (Jena) 111:339–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curns AT, Holman RC, Shay DK, Cheek JE, Kaufman SF, Singleton RJ, Anderson LJ. 2002. Outpatient and hospital visits associated with otitis media among American Indian and Alaska native children younger than 5 years. Pediatrics 109:E41–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel HJ. 1999. Otitis Media: An Evolutionary Perspective. In: Trevathan W, Smith EO, McKenna JJ, editors. Evolutionary Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press. p 75–100. [Google Scholar]

- Dayal A, Rhee JS, Garcia GJ. 2016. Impact of Middle versus Inferior Total Turbinectomy on Nasal Aerodynamics. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 155:518–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Ru JA, Grote JJ. 2004. Otitis media with effusion: disease or defense? A review of the literature. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle WJ, Rood SR. 1979. Anatomy of the auditory tube and related structures in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta). Acta Anat (Basel) 105:209–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eden AR, Laitman JT, Gannon PJ. 1990. Mechanisms of middle ear aeration: anatomic and physiologic evidence in primates. Laryngoscope 100:67–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedland DR. 1993. Development of Upper Respiratory Tract Motor Nuclei in the Rat (Rattus Norvegicus). In: Anatomy and Physiology. Ann Arbor, MI: City University of New York. p 444. [Google Scholar]

- Gannon PJ, Eden AR. 1987. A specialized innervation of the tensor tympani muscle in Macaca fascicularis. Brain Res 404:257–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia GJM, Hariri BM, Patel RG, Rhee JS. 2016. The relationship between nasal resistance to airflow and the airspace minimal cross-sectional area. J Biomech 49:1670–1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng R, Wang Q, Chen E, Zheng QY. 2019. Current Understanding of Host Genetics of Otitis Media. Front Genet 10:1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles M, Asher I. 1991. Prevalence and natural history of otitis media with perforation in Maori school children. J Laryngol Otol 105:257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM. 2020. Diagnosis and Management of Obstructive Sleep Apnea: A Review. JAMA 323:1389–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal RK, Mashimo H. 2006. Physiology of oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal motility. In: GI Motility Online: Nature. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfeld M, Tauman R, DeRowe A, Sivan Y. 2003. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome due to adenotonsillar hypertrophy in infants. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 67:1055–1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribben B, Salkeld LJ, Hoare S, Jones HF. 2012. The incidence of acute otitis media in New Zealand children under five years of age in the primary care setting. J Prim Health Care 4:205–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunasekera H, Knox S, Morris P, Britt H, McIntyre P, Craig JC. 2007. The spectrum and management of otitis media in Australian indigenous and nonindigenous children: a national study. Pediatr Infect Dis J 26:689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha S 2007. The Levator Veli Palatini Muscle in Cleft Palate Anatomy and Its Implications for Assessment Velopharyngeal Function: A Literature Review. Commun Sci Disord 12:77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan AL, Sabra O, Hadi U. 2008. Prevalence of adenoid hypertrophy in adults with nasal obstruction. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 37:469–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DFN. 1995. The Anatomy and Physiology of the Mammalian Larynx. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hendricks JC, Kline LR, Kovalski RJ, O'Brien JA, Morrison AR, Pack AI. 1987. The English bulldog: a natural model of sleep-disordered breathing. J Appl Physiol (1985) 63:1344–1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard BA, Rice GB, Muzaffar AR. 2010. Adenoid involvement in velopharyngeal closure in children with cleft palate. Can J Plast Surg 18:135–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung R, Kuhlo W. 1965. Neurophysiological Studies of Abnormal Night Sleep and the Pickwickian Syndrome. Prog Brain Res 18:140–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn CM, Line S. 2010. The Merck Veterinary Manual, 10th ed. Kenilworth, NJ: Merck. [Google Scholar]

- Kang HM, Kang JH. 2021. Effects of nasopharyngeal microbiota in respiratory infections and allergies. Clin Exp Pediatr 64:543–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khami M, Tan S, Glicksman JT, Husein M. 2015. Incidence and Risk Factors of Velopharyngeal Insufficiency Postadenotonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 153:1051–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim LJ, Freire C, Fleury Curado T, Jun JC, Polotsky VY. 2019. The Role of Animal Models in Developing Pharmacotherapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J Clin Med 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Heo GE, Seo A, Na Y, Chung SK. 2014. Correlation between nasal airflow characteristics and clinical relevance of nasal septal deviation to nasal airway obstruction. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 192:95–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KH, Grzonka MA, Koch J. 1998. Pathology of the palatal aponeurosis in cleft palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 35:530–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen A, Tolvi M, Jauhiainen M, Kekalainen E, Laulajainen-Hongisto A, Lamminmaki S. 2021. Complications of COVID-19 Nasopharyngeal Swab Test. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 147:672–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kryger MH. 1983. Sleep apnea. From the needles of Dionysius to continuous positive airway pressure. Arch Intern Med 143:2301–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kummer AW, Marshall JL, Wilson MM. 2015. Non-cleft causes of velopharyngeal dysfunction: implications for treatment. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 79:286–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laitman JT. 1977. The Ontogenetic and Phylogenetic Development of the Upper Respiratory System and Basicranium in Man. In. Ann Arbor, MI: Universtiy of Microfilms: Yale University. [Google Scholar]

- Lee RA, Herigon JC, Benedetti A, Pollock NR, Denkinger CM. 2021. Performance of Saliva, Oropharyngeal Swabs, and Nasal Swabs for SARS-CoV-2 Molecular Detection: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Microbiol 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J, Hafren L, Kerschner J, Li JD, Brown S, Zheng QY, Preciado D, Nakamura Y, Huang Q, Zhang Y. 2017. Panel 3: Genetics and Precision Medicine of Otitis Media. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 156:S41–S50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindman R, Paulin G, Stal PS. 2001. Morphological characterization of the levator veli palatini muscle in children born with cleft palates. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 38:438–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonergan RP 3rd, Ware JC, Atkinson RL, Winter WC, Suratt PM. 1998. Sleep apnea in obese miniature pigs. J Appl Physiol (1985) 84:531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik J, Dholakia S, Spector BM, Yang A, Kim D, Borchard NA, Thamboo A, Zhao K, Nayak JV. 2021. Inferior meatus augmentation procedure (IMAP) normalizes nasal airflow patterns in empty nose syndrome patients via computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 11:902–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard JE, Fleshman JK, Tschopp CF. 1972. Otitis media in Alaskan Eskimo children. Prospective evaluation of chemoprophylaxis. JAMA 219:597–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh C, Clemm HH, Sewry N, Hrubos-Strom H, Schwellnus MP. 2021. Diagnosis and management of nasal obstruction in the athlete. A narrative review by subgroup B of the IOC Consensus Group on "Acute Respiratory Illness in the Athlete". J Sports Med Phys Fitness 61:1144–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills SE, Gaffey MJ, Frierson HF. 2000. Tumors of the Upper Aerodigestive Tract and Ear. In: Atlas of Human Pathology. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology. p 4–70. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherji SK, Castillo M. 1998. Normal cross-sectional anatomy of the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and oral cavity. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 8:211–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S, Luo L, Quimby A, Barrowman N, Vaccani JP, Caulley L. 2019. Immediate versus delayed surgery in congenital choanal atresia: A systematic review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 119:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagano AS, Smith CM, Balzeau A, Marquez S, Laitman JT. 2022. Nasopharyngeal morphology contributes to understanding the “muddle in the middle” of the Pleistocene hominin fossil record. Anatomical Record. (see this issue) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou G, Kambas I, Tsaoussoglou M, Panaghiotopoulou-Gartagani P, Chrousos G, Kaditis AG. 2013. Age-dependent changes in the size of adenotonsillar tissue in childhood: implications for sleep-disordered breathing. J Pediatr 162:269–274 e264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickrell KL, Massengill R Jr., Quinn G, Brooks R, Robinson M. 1976. The effect of adenoidectomy on velopharyngeal competence in cleft palate patients. Br J Plast Surg 29:134–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radulesco T, Meister L, Bouchet G, Giordano J, Dessi P, Perrier P, Michel J. 2019. Functional relevance of computational fluid dynamics in the field of nasal obstruction: A literature review. Clin Otolaryngol 44:801–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsden JD, Campisi P, Forte V. 2009. Choanal atresia and choanal stenosis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 42:339–352, x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawlings BA, Higgins TS, Han JK. 2013. Bacterial pathogens in the nasopharynx, nasal cavity, and osteomeatal complex during wellness and viral infection. Am J Rhinol Allergy 27:39–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rettig E, Tunkel DE. 2014. Contemporary concepts in management of acute otitis media in children. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 47:651–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee JS, Poetker DM, Smith TL, Bustillo A, Burzynski M, Davis RE. 2005. Nasal valve surgery improves disease-specific quality of life. Laryngoscope 115:437–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues F, Foster D, Nicoli E, Trotter C, Vipond B, Muir P, Goncalves G, Januario L, Finn A. 2013. Relationships between rhinitis symptoms, respiratory viral infections and nasopharyngeal colonization with Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae and Staphylococcus aureus in children attending daycare. Pediatr Infect Dis J 32:227–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez DP, Orscheln ES, Koch BL. 2017. Masses of the Nose, Nasal Cavity, and Nasopharynx in Children. Radiographics 37:1704–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg BW, Murariu D, Pang KP. 2016. Trends in CPAP adherence over twenty years of data collection: a flattened curve. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 45:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sade J, Ar A. 1997. Middle ear and auditory tube: middle ear clearance, gas exchange, and pressure regulation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 116:499–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilder AG, Chonmaitree T, Cripps AW, Rosenfeld RM, Casselbrant ML, Haggard MP, Venekamp RP. 2016. Otitis media. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2:16063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaratna CV, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Campbell BE, Matheson MC, Hamilton GS, Dharmage SC. 2017. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 34:70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton KE, Woodson H, Gay S, Suratt PM. 1993. Pharyngeal fat in obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 148:462–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton RJ, Holman RC, Plant R, Yorita KL, Holve S, Paisano EL, Cheek JE. 2009. Trends in otitis media and myringtomy with tube placement among American Indian/Alaska native children and the US general population of children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 28:102–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart KJ, Ahmad T, Razzell RE, Watson AC. 2002. Altered speech following adenoidectomy: a 20 year experience. Br J Plast Surg 55:469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suratt PM, McTier RF, Wilhoit SC. 1985. Collapsibility of the nasopharyngeal airway in obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis 132:967–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang NNY, So HC, Ng KY, Cowling BJ, Leung GM, Ip DKM. 2021. Diagnostic performance of different sampling approaches for SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR testing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 21:1233–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernacchio L, Lesko SM, Vezina RM, Corwin MJ, Hunt CE, Hoffman HJ, Mitchell AA. 2004. Racial/ethnic disparities in the diagnosis of otitis media in infancy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 68:795–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenig BM. 2015. Embryology, Anatomy, and Histology of the Pharynx. In: Atlas of Head and Neck Pathology, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Williams CJ, Coates HL, Pascoe EM, Axford Y, Nannup I. 2009. Middle ear disease in Aboriginal children in Perth: analysis of hearing screening data, 1998-2004. Med J Aust 190:598–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witzel MA, Rich RH, Margar-Bacal F, Cox C. 1986. Velopharyngeal insufficiency after adenoidectomy: an 8-year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 11:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaremchuk K, Garcia-Rodriguez L. 2017. The History of Sleep Surgery. Adv Otorhinolaryngol 80:17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim N, Sahan M, Karslioglu Y. 2008. Adenoid hypertrophy in adults: clinical and morphological characteristics. J Int Med Res 36:157–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ylikoski J, Savolainen S, Jousimies-Somer H. 1989. Bacterial flora in the nasopharynx and nasal cavity of healthy young men. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 51:50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]