Abstract

Coronavirus 2 is responsible for Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), and the main sequela is persistent fatigue. Post-viral fatigue is common and affects patients with mild, asymptomatic coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). However, the exact mechanisms involved in developing post-COVID-19 fatigue remain unclear. Furthermore, physical and cognitive impairments in these individuals have been widely described. Therefore, this review aims to summarize and propose tools from a multifaceted perspective to assess COVID-19 infection. Herein, we point out the instruments that can be used to assess fatigue in long-term COVID-19: fatigue in a subjective manner or fatigability in an objective manner. For physical and mental fatigue, structured questionnaires were used to assess perceived symptoms, and physical and cognitive performance assessment tests were used to measure fatigability using reduced performance.

Keywords: Chronic fatigue syndrome, Coronavirus, Fatigue, Neurologic manifestations, Neuropsychological tests, Physical performance

1. Introduction: "I feel exhausted"

Coronavirus 2 causes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV-2), infecting more than 580 million people and killing approximately 6,4 million. The phrase “I feel exhausted” became known worldwide after the clinical "resolution" of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) drew attention to the sequelae of the disease. After the acute phase of the disease, approximately 80% (Kaczynski and Mylonakis, 2022, Lopez-Leon et al., 2021) remain with long-term sequelae (Willi et al., 2021), namely "Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" (Nalbandian et al., 2021), "Post-COVID-19 Syndrome" (Salamanna et al., 2021), or "Long COVID-19" (Yelin et al., 2022). The severity of the inflammatory response, deficiency in the resolution of inflammation, and systemic involvement of Sars-Cov-2 could explain the persistence of COVID-19 symptoms (Mehandru and Merad, 2022). The global estimate is that approximately 200 million individuals suffer long-term sequelae (Chen et al., 2022). Furthermore, even vaccinated patients risk developing long COVID-19 (Al-Aly et al., 2022).

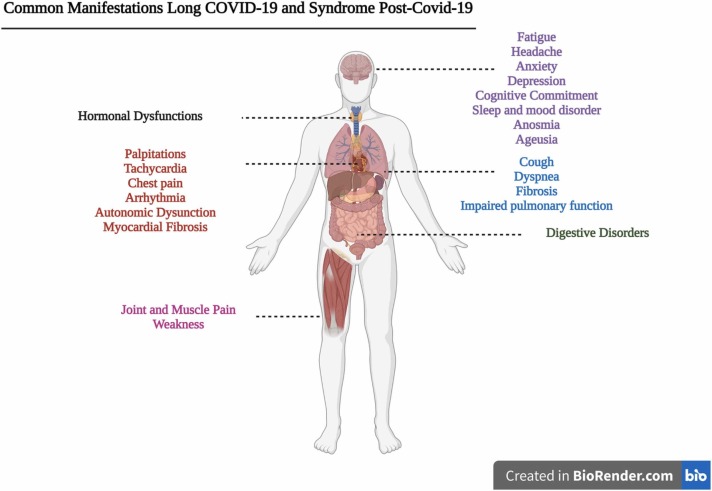

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines define "Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome" as those signs and symptoms (illustrated in Fig. 1) that persist between 4 and 12 weeks after acute onset of the disease and "post-COVID-19 syndrome" or "Long COVID-19" as those that persist beyond 12 weeks (three months) (Venkatesan, 2021). The systemic and persistent COVID-19 sequelae impair pulmonary, cardiovascular, neuropsychological, endocrine, gastrointestinal, and musculoskeletal systems (Fig. 1) (Gupta et al., 2020; L. Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021; Lopez-Leon et al., 2021; Pilotto et al., 2021; Salamanna et al., 2021; Weng et al., 2021; Willi et al., 2021). The phenotype is similar to the post-viral neurological syndrome of other respiratory syndromes, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) of other coronaviruses (Batawi et al., 2019, Hickie et al., 2006, Moldofsky and Patcai, 2011, Perrin et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

Common and persistent manifestations after COVID-19. Legend: Main manifestations and late sequela of COVID-19 between three and six months or more.

Source: Author (2022).

Fatigue is the primary and prevalent sequela (Lopez-Leon et al., 2021, Van Herck et al., 2021, Willi et al., 2021), even in asymptomatic COVID-19 (Malkova et al., 2021). Approximately 63% of individuals with sequelae of COVID-19 have difficulty performing daily tasks, self-care, and mobility and have a social and recreational impairment with difficulty returning to work (Ceban et al., 2021). This sequela is emblematic because fatigue as a symptom is still not well understood. Unlike in healthy individuals, where it occurs as a physiological response to intense and prolonged activities transiently and predictably (Kluger et al., 2013), disease-related fatigue is referred to as fatigue or exhaustion even at rest, with a negative impact on functionality and quality of life (Finsterer and Mahjoub, 2014).

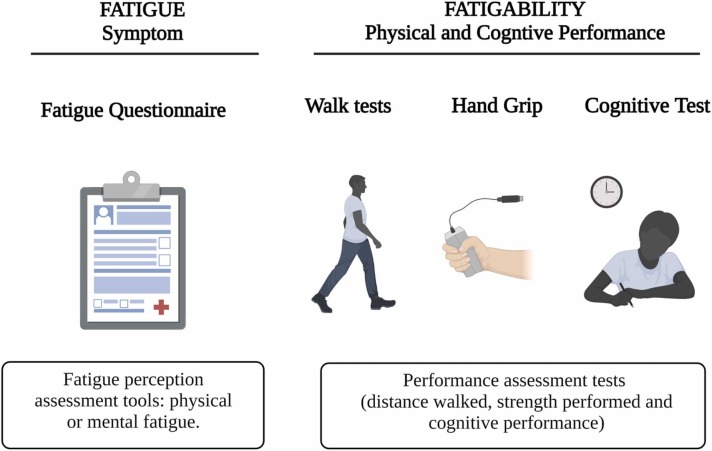

Fatigue is a complex biological, psychosocial, and behavioral phenomenon (Aaronson et al., 1999, Finsterer and Mahjoub, 2014, Katz et al., 2018, Walters et al., 2019). Mainly (and didactically), fatigue is classified into physical (central or peripheral) and mental (Boyas and Guével, 2011, Tanaka and Watanabe, 2012). Central fatigue is associated with supraspinal and spinal commands (Tanaka and Watanabe, 2012) and adenosinergic signaling (Alves et al., 2019), which influences the physical component (Tanaka et al., 2013). Peripheral fatigue is associated with the neuromuscular junction responsible for excitation-contraction coupling, the skeletal muscles for contractile function, dependence on blood flow, the state of the intracellular medium, and availability of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Allen et al., 2008, Boyas and Guével, 2011, Tanaka and Watanabe, 2012). Increased perception of physical exertion defines mental fatigue, which limits exercise tolerance in humans (Marcora et al., 2009). However, it does not appear to reduce the central nervous system’s (CNS) ability to recruit muscle activity (Pageaux et al., 2015). Moreover, mental fatigue is experienced during specific cognitive activities, such as executive attention and working memory (Ortelli et al., 2021). However, this association is not yet well understood (Ishii et al., 2014). Therefore, fatigue assessment is crucial for therapeutic planning and prognosis of COVID-19. Physical and cognitive tests assess the objective (signs) phase of fatigue, known as fatigability ( Fig. 2) (Finsterer and Mahjoub, 2014, Kluger et al., 2013), while standardized and available questionnaires assess fatigue’s symptomatic (subjective) spectrum.

Fig. 2.

Practical examples of fatigue and fatigability assessment. Legend: Fatigue is the subjective perception of physical and/or mental tiredness/strain/weakness in symptom assessment questionnaires. Fatigability is a measure of fatigue represented by reduced physical and/or cognitive impairment. The walking test predicts an essential measure of fatigue, reduced grip strength, and cognitive impairment.

Source: Author (2022).

Our research group investigated post-viral fatigue in long COVID-19 patients from a multifaceted viewpoint (Campos et al., 2021). This review proposes fatigue assessment tools for long COVID-19. These methodologies are essential for understanding the abnormal psychobiology of fatigue and for the follow-up (short and long term) of one of the central sequelae of COVID-19 (Bonizzato et al., 2022, Bungenberg et al., 2022, Gaber, 2021).

2. Post-viral fatigue: this old stranger is back with COVID-19

Post-viral fatigue was first observed during the most devastating epidemic in modern history, the Spanish flu of 1918, caused by the influenza A (H1N1) virus, with global mortality ranging from 24.7 to 50 million (Johnson and Mueller, 2002, Trilla et al., 2008). More recently, the incidence of fatigue was 2.8% during the 2003 H1N1 pandemic, mainly in young adults under 30 years of age (Magnus et al., 2015). Fatigue also appears after Ebola infection (9–28%)(Rowe et al., 1999; Wilson et al., 2018), West Nile fever (31%) (Garcia et al., 2014), dengue fever (82%) (Ren et al., 2018), and non-epidemic infections such as tick encephalitis (30%) (Bogovič et al., 2019), Epstein-Barr (9%) (White et al., 1998), and mononucleosis (11–38%) (Buchwald et al., 2000, Hickie et al., 2006, Katz et al., 2009). Chronic fatigue after post-viral infection is common.

Fatigue due to COVID-19 is common, frequent, and independent of disease severity (Townsend et al., 2020a). Carfi et al. (2020) demonstrated that fatigue was the main symptom reported in hospitalized patients during the acute phase and after a mean follow-up of 60 days (Carfì et al., 2020). In 458 non-hospitalized patients, fatigue was present in approximately 46% of patients, assessed using the Chalder Fatigue Scale, and persisted for approximately four months after clinical diagnosis (Stavem et al., 2021). A cohort study of 1733 COVID-19 infected patients discharged from a hospital in Wuhan, China, showed that fatigue was present in approximately 63% of the sample and persisted for approximately six months. In addition, 23% of 1692 disease-infected patients showed reduced exercise capacity in the 6-minute walk test (6 MWT) (C. Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). Post viral fatigue is prevalent, even in asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 (Malkova et al., 2021). Of 58 asymptomatic patients admitted to a hospital in Wuhan, China, with COVID-19 confirmed using reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay and abnormalities on lung CT scan, 16 (27.6%) had fatigue days after hospitalization (Meng et al., 2020).

Seven months after the onset of COVID-19, persistent fatigue, post-exertional malaise, cognitive dysfunction, sensorimotor changes, headache, sleep disturbances, and muscle and joint pain persisted in a sample of 3762 patients from 56 countries (Davis et al., 2020). The symptoms observed were similar to those of chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/MS) (Fukuda et al., 1994, Wong and Weitzer, 2021), persistent and disabling, with considerable social and economic repercussions (Nacul et al., 2020). Interestingly, fatigue and cognitive dysfunction such as brain fog, memory-related problems, attention, and sleep disturbances are persistent and more common in the long term (between six months or more) than in the medium term (less than six months) for hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients. In addition, the frequency of anxiety and depression increases in the medium and long term (Premraj et al., 2022).

COVID-19 can cause relatively severe and more prolonged symptoms associated with post-viral fatigue than other respiratory tract viral infections (Gaber, 2021). A high prevalence of impaired skeletal muscle strength and reduced physical performance has been observed in hospitalized patients recovering from COVID-19 without prior locomotor impairment (Paneroni et al., 2021). Apathy, executive function deficits, and cognitive impairments were confirmed after neuropsychological and neurophysiological tests were performed on post-COVID-19 patients (Ortelli et al., 2021). Fatigue may modify motor and cognitive strategies to protect the body and prevent further damage (Glass et al., 2004). The perception of affected individuals in simple mental tasks requiring substantial effort indicates that the patients need more significant effort, showing a greater number of brain regions being used in processing auditory and spatial cognitive information (Lange et al., 2005).

Previously productive individuals with stable clinical conditions may present with chronic conditions after infection with the virus, thereby increasing the demand for healthcare services. Considering the persistence of fatigue due to MERS, approximately 48% after 12 months and 32% after 18 months, and due to SARS, approximately 40% after 3.5 years (Ahmed et al., 2020), it is expected that after COVID-19 infection, there is also a high prevalence of fatigue and other neuropsychological sequelae with the need for treatment in this population (Malik et al., 2022). The follow-up of patients after the acute phase of the disease showed chronicity in functionality and the consequent socioeconomic delay that these limitations may generate (Willi et al., 2021). In Toronto, patients infected with SARS in 2003 could not return to work one year after the illness because of persistent fatigue, diffuse myalgia, weakness, and depression (Moldofsky and Patcai, 2011). COVID-19 patients still experience pain, mobility impairment, anxiety, and depression for a year (L. Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). These sequelae create the need for chronic treatment, which financially impacts people's lives (Graves et al., 2021). Approximately 60 million unemployment insurance claims were filed in the USA; the estimated cost of lost output and reduced health was $16 trillion (Cutler and Summers, 2020).

3. Physiopathological mechanism: neuroinflammation and fatigue

The pathophysiological process arising from SARS-CoV-2 infection can cause inflammation in the CNS and peripheral nervous system (PNS) (Hu et al., 2020, Mao et al., 2020). Commonly, neurological and neuropsychiatric symptoms are the main manifestations in hospitalized patients, even after six months or more of diagnosis (Premraj et al., 2022). These manifestations may result from factors such as lung injury and systemic alteration with sepsis, organ failure, encephalopathy, the consequences of an immune-mediated inflammatory response, and neurological manifestations caused by direct CNS and PNS involvement (Pezzini and Padovani, 2020).

Human neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and endothelial cells express angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in the medial temporal gyrus and posterior cingulate cortex and poorly in the hippocampus (Chen et al., 2021). After infection, the virus spreads rapidly through the CNS (Netland et al., 2008) and other tissues because host ACE2 is the receptor for binding the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 and is expressed in the lungs, intestines, kidneys, brain, and blood vessels (Wan et al., 2020). Coronavirus crosses the blood-brain barrier through the olfactory nerves through the cribriform plate (Guo et al., 2008, Hives et al., 2017, Kida et al., 1993, Moldofsky and Patcai, 2011), as confirmed in transgenic mice expressing the human ACE2 receptor in epithelial cells. Genetic material and proteins of SARS-CoV-2 have been detected in the CNS of postmortem patients, with pronounced neuroinflammation in the brainstem (TC) (Matschke et al., 2020). Viral infection causes neuronal and glial damage and contributes to the development of neurological diseases (Giraudon and Bernard, 2010).

SARS-CoV-2 stimulates the host immune system to release cytokines and subsequent inflammation and immune dysfunction through the activation or impairment of various immune cells such as dendritic cells, natural killer cells, macrophages, and neutrophils. This process can lead to flu-like symptoms and then to septic shock (Brenu et al., 2010, Lorusso et al., 2009). In addition, inflammation-induced delirium contributes to different symptoms and sequelae (Proal and VanElzakker, 2021, Wan et al., 2020).

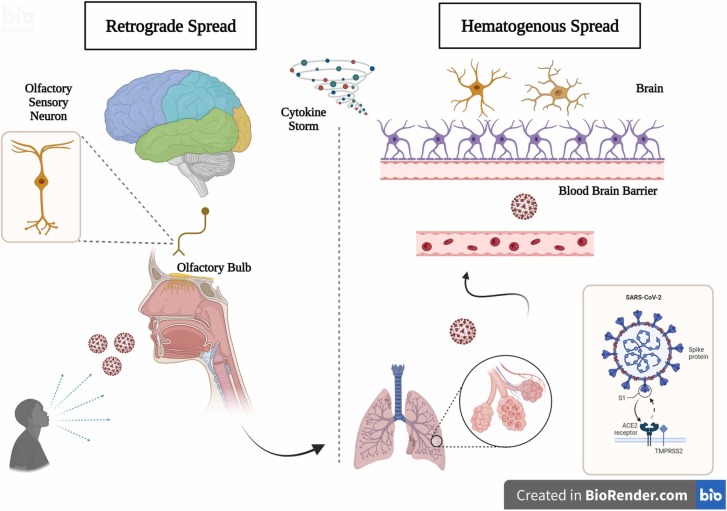

The two routes viruses can enter the CNS are hematogenous and retrograde dissemination ( Fig. 3). In the first case, there is direct viral infection of the endothelium, accumulation of inflammatory mediators, and movement across the blood-brain barrier. In the second case, there is the involvement of peripheral nerves, transport through axonal fibers, and entry into the CNS (Berth et al., 2009, Ellul et al., 2020, Hu et al., 2020, Iadecola et al., 2020, McGavern and Kang, 2011). The "Trojan Horse" mechanism is also described, with infection of leukocytes by the virus and entry into the brain through the paracellular route (Galea et al., 2022, Hu et al., 2020). Coronaviruses can also enter the cardiorespiratory center through mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors in the airway (Desforges et al., 2019, Román et al., 2020). Olfactory dysfunction indicates neural invasion of the CNS by the olfactory bulb (Meinhardt et al., 2021), which has also been observed in animal models (Netland et al., 2008).

Fig. 3.

Mechanisms of entry of Sars-Cov-2 into the nervous system. Legend: The two routes of SARS-CoV-2 infection in the nervous system (hematogenous and retrograde) are possible pathogenic mechanisms. A cytokine storm is a condition that contributes to the development of symptoms.

Source: Author (2022).

There is evidence of the mechanisms of post-viral fatigue in COVID-19 patients. Versace et al. (2021) and Ortelli et al. (2021) demonstrated impairment of intracortical GABAergic circuits associated with the primary motor cortex (M1) in post-COVID-19 patients with persistent fatigue and cognitive dysfunction (Ortelli et al., 2021, Versace et al., 2021). According to the authors (Versace et al., 2021), neuroinflammation with activated microglial and astrocytic cells induces more neural cytokines (Kwon and Koh, 2020) that may probably cause GABAergic dysfunction and fatigue (Versace et al., 2021). Interestingly, patients had high levels of IL-6 and PCR in the acute phase of the disease, which is responsible for systemic inflammation. Furthermore, a previous study on an animal model suggests that the hyperinflammatory state induced by IL-6 can reduce the density of functional GABA receptors, thereby causing an imbalance between inhibition and synaptic excitation (Garcia-Oscos et al., 2012).

A significant review study with meta-analysis (Ceban et al., 2021) demonstrated that fatigue and cognitive impairment (CG) are common manifestations of "post-COVID-19 syndrome" or "long Covid-19". In subgroup analysis, a higher proportion of fatigue and CG was observed for females (46% fatigue and 56% CG) than for males (30% fatigue and 35% CG); however, there was no significant difference between genders. In addition, there was also no difference in the proportion of hospitalized (36% fatigue and 30% CG) and non-hospitalized (44% fatigue and 20% CG) patients. There was no difference in the proportion of those with less (33% fatigue and 22% CG) or more than six months (31% fatigue and 21% CG) of persistency after the diagnosis of COVID-19. Notably, there was a high level of heterogeneity for fatigue (I2 = 99.1%) and CG (I2 = 98.0%), although a reduction was observed in subgroup analysis.

Clinical data from patients hospitalized with COVID-19 have demonstrated that changes associated with the CNS, PNS, and musculoskeletal systems are common (Bungenberg et al., 2022, Galea et al., 2022, Mao et al., 2020). Substantial neurological and psychiatric morbidities have been observed for approximately six months after infection (Taquet et al., 2021). Advanced age, comorbidities, and disease severity can predict neurological manifestations (Pilotto et al., 2021). Above all, even if neurological manifestations and cognitive decline are associated with severe and critical patients, those not hospitalized and with a mild and moderate disease also show significant long-term impairments (Goërtz et al., 2020, Hellmuth et al., 2021, Salamanna et al., 2021).

Female sex increases the risk for persistent post-COVID-19 fatigue(Fernández-De-las-peñas et al., 2022; L. Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). Compared to males, females have an odds ratio (OR) of 1.43 (95% CI 1.04–1.96) for fatigue at 12 months post-COVID-19(L. Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). Similarly, a meta-analysis of studies on COVID-19 survivors showed greater self-reported fatigue in women after hospital admission, with an OR of 1.78 (95% CI 1.53–2.87)(Rao et al., 2022). This high probability of fatigue after COVID-19 persists in non-hospitalized women(Stavem et al., 2021).

The reasons females experience more persistent symptoms than males remain unclear, but they contribute to greater psychological stress, higher levels of anxiety and depression, worse sleep quality, and inflammatory response(Fernández-De-las-peñas et al., 2022; Rudroff et al., 2022). Females with COVID-19 seem to have a different inflammatory condition than males, associated with persistent fatigue. A significantly lower number of interleukin 2 (IL-2) and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) producing T cells were observed in tired women(Meisinger et al., 2022). Interleukin 6 (IL-6) levels were also higher in cases with fatigue, although within the normal range. Compared to men, however, IL-6 levels were higher in the presence of post-COVID-19 viral fatigue(Ganesh et al., 2022). More research is needed to understand better the role of IL-6 in post-COVID-19 fatigue(Rudroff et al., 2022).

Fatigue is a special feature in COVID-19 as it stems from the SARS-CoV-2 infection itself, but it can also be a manifestation of underlying psychological disorders(Morgul et al., 2021; Rudroff et al., 2020; Ruiz et al., 2022). COVID-19 is responsible for neuropsychiatric sequelae associated with persistent fatigue(Mazza et al., 2021), but the psychological impact of the pandemic itself was responsible for stress, anxiety, and depression in the general population(Passavanti et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). Fear, restrictive measures, and social isolation resulting from the pandemic are related to physical and mental fatigue(Morgul et al., 2021). Stress, physiological or psychological, is a predisposing factor to the development of fatigue(Chaudhuri and Behan, 2004; Kato et al., 2006). As for fear, a 23.1% prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was demonstrated within 3 months after COVID-19(Zeng et al., 2022), similar to the prevalence of PTSD (23.0%) observed in other infectious disease pandemics(Yuan et al., 2021). The outbreak of a highly transmitted infectious disease causes stress and anxiety, which can lead to depression(Yuan et al., 2021). Furthermore, there is a correlation between fatigue in COVID-19 and a previous history of anxiety and depression(Joli et al., 2022). Anhedonia has been observed in fatigued participants after SARS-CoV-2 infection(El Sayed et al., 2021). However, the correlation between depression and persistent fatigue in COVID-19 is not fully understood(Townsend et al., 2020b).

Chronic pain is another common manifestation in patients with COVID-19 with long-term fatigue and depressed mood(L. Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021; Janbazi et al., 2022). These conditions are indeed described following viral infections(Clauw et al., 2020). Pain and fatigue have subjective characteristics and can be caused by physical or psychological factors(Clauw et al., 2020). Although there is an association between pain and fatigue, the causal association is not fully clarified(Fishbain et al., 2003). These findings demonstrate the need to evaluate different constructs in patients with persistent post-COVID-19 fatigue and understand the factors associated with the physical, mental, and psychological aspects of fatigue(Calabria et al., 2022).

4. Fatigue assessment methods in COVID-19: a multifaceted view

We should consider that the COVID-19 pandemic is an atypical situation needing emerging diagnosis and treatment, which explains the lack of evidence on the validation of measurement instruments for chronic manifestations of the disease, such as post-viral fatigue. Instrument validation has an important gap in fatigue’s pathophysiological and pathogenic mechanisms (Aaronson et al., 1999, Tyson and Brown, 2014), especially in post-viral fatigue due to COVID-19.

Problems frequently found are low-quality results or bias in research completion due to the limited selection of measurement instruments (Machado et al., 2021). Construct-specific assessment methods are essential, considering the instrument's reliability, validity, and responsiveness (Mokkink et al., 2016). Ceban and colleagues’ review (Ceban et al., 2021) used specific methods for the construct "fatigue." They obtained a higher proportion of individuals manifesting the symptom compared to a lower proportion obtained in studies that used non-specific methods such as self-report and dichotomous questions.

Chaudhuria and Behan. (2004) described fatigue as subjective and characterized it as difficulty initiating or maintaining voluntary activities (Chaudhuri and Behan, 2004). Therefore, it can be considered a debilitating and non-transitory condition of physical and mental fatigue, characterized by muscle weakness and lack of energy, altered concentration, sluggishness, and drowsiness (Marcora et al., 2009). Thorsten Rudroff and colleagues (2020) described fatigue as "decreased physical and/or mental performance" and proposed a model that could theoretically explain the mechanisms of fatigue in COVID-19 patients (Rudroff et al., 2020). According to the authors, central, psychological, and peripheral factors may be associated with pathophysiological mechanisms. The central factors are associated with the possible neuroinvasive mechanism, inflammation, demyelination, neurotransmitter changes, and psychological mechanisms associated with stress, fear, anxiety, and depression observed in these patients. Finally, peripheral factors are directly associated with the musculoskeletal system due to pain and muscle weakness (Rudroff et al., 2020).

This phenomenon encompasses different aspects, and a robust assessment may explain, in part, possible sites of fatigue manifestation in these patients. Our research group has studied post-viral fatigue due to COVID-19 from different perspectives and with different measurement instruments to assess physical and mental performance, questionnaires for symptom assessment, and standardized tests for assessing cognitive function (Campos et al., 2021). The following instruments evaluate fatigue in physical, cognitive, and symptomatic aspects.

4.1. Structured questionnaire for fatigue assessment

Structured questionnaires are widely used to assess fatigue as a symptom that affects physical, mental, cognitive, and emotional functions, motivation, and activities of daily living (Tyson and Brown, 2014). Unidimensional instruments focus on assessing the severity of fatigue and are usually faster and easier to apply. However, they are limited in their ability to interpret the range of factors that may be associated with the manifestation of the symptom because they assess only one dimension (Whitehead, 2009). Among these instruments, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Fatigue (FACIT), Brief Fatigue Inventory, Visual Analog Scale-Fatigue, Fatigue Severity Scale, and Fatigue Impact Scale have been used to assess the construct (Machado et al., 2021, Tyson and Brown, 2014). Multidimensional instruments can investigate different physical, emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and affective domains (Whitehead, 2009). In this group, the individual strength checklist, Piper Fatigue Scale, Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory, and Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire are widely used in randomized clinical trials (Chalder et al., 1993, Daynes et al., 2021, Kim et al., 2020, Machado et al., 2021, Smets et al., 1995, Tuzun et al., 2021, Tyson and Brown, 2014).

Table 1. presents the unidimensional and multidimensional questionnaires that have been used to assess fatigue in COVID-19 patients, including the Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire (Elanwar et al., 2021, Stavem et al., 2021, Townsend et al., 2021a, Townsend et al., 2021b, Tuzun et al., 2021), Fatigue Severity Scale (Leite et al., 2022), Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (Morin et al., 2021), FACIT (Evans et al., 2021), Brief Fatigue Inventory (Stallmach et al., 2022), Checklist Individual Strength (Heesakkers et al., 2022, Van Herck et al., 2021), and Visual Analog Scale – Fatigue and modified BORG scale (Cortés-Telles et al., 2021, Daher et al., 2020, Paneroni et al., 2021). In addition, the presence of fatigue in activities of daily living has been assessed using the Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspnea Questionnaire (PFSDQ-M) (Campos et al., 2021, Carter et al., 2022).

Table 1.

Unidimensional and multidimensional questionnaires used to assess fatigue in COVID-19.

| Instrument |

Description |

Findings in COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Unidimensional | ||

| Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy – Fatigue (FACIT) | It has 13 items assessing the perception of fatigue related to the last seven days and the answers are given on a Likert scale from 0 to 4 points (Cella et al. 2002). | The mean total score for fatigue was 16.8 (13.2) points among the 1036 subjects at the seventh month after hospitalization for COVID-19(Evans et al., 2021). |

| Brief Fatigue Inventory | It has an item about fatigue of the last week (yes or no). There are three rating items with scores from 0 to 10 for fatigue severity at "now", "usual" and "worst" times. And six items that assess the impact of fatigue over the past 24 h(Y. W. Chen, Coxson, and Reid 2016). | Fatigue present up to 163 days after COVID-19, assessed in 315 (93.2%) of 338 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, of whom 150 (47.6%) had moderate fatigue (4–6 points) (Stallmach et al., 2022). |

| Visual Analog Scale – Fatigue | Visual analog scale that assesses the severity of fatigue in a numerical measure from 0 to 10(Tseng, Gajewski, and Kluding 2010). | The mean score for physical fatigue was 8 points and 7 for mental fatigue in 150 subjects hospitalized for COVID-19(Tuzun et al., 2021). |

| Fatigue Severity Scale | It assesses the severity of fatigue on nine items referring to perceived fatigue over the past two weeks. Each item is scored from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 points (strongly agree)(Krupp and Pollina 1996). | Of the 124 subjects evaluated, 71(57%) had relevant fatigue at hospital discharge (≥ 4 points) post-COVID-19(Leite et al., 2022). |

| Fatigue Impact Scale | It assesses the impact of fatigue on subjects' functional limitation in the last month. Recently adapted (modified version) to be responsive to daily use with eight items ranging from 0 to 4 points(Fisk and Doble 2002). | NE |

| Modified BORG Scale | Assesses the perception of fatigue on a scale of 0–10 points(Borg et al. 2010). | In the walk test, perceived fatigue was on average 1.9 (1.8) points in a sample of 186 subjects who underwent hospitalization for COVID-19(Cortés-Telles et al., 2021). |

| Multidimensional | ||

| Checklist Individual Strength | It consists of a 20-item instrument with four domains (subjective fatigue, motivation, activity and concentration), referring to the last two weeks (Vercoulen et al. 1994). | 138 (56.1%) of 246 patients who had been in an Intensive Care Unit had abnormal fatigue (27 points or more) up to one year after (Heesakkers et al., 2022). |

| Piper Fatigue Scale | It assesses behavioral, affective, sensory, mood-related, and cognitive aspects. The revised version has 22 items with Likert-type responses ranging from 0 to 10(Reeve et al. 2012). | NE |

| Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory | A 20-item instrument for assessing general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced activity, and reduced motivation. The score is given for each domain and ranges from 4 to 20 points(Smets et al., 1995). | Patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19 had persistent fatigue with high scores in the domain of reduced motivation and mental fatigue(Morin et al., 2021). |

| Chalder Fatigue Questionnaire | 11-item instrument that assesses the domains mental fatigue and physical fatigue and each item is scored from 0 to 3 points (Chalder et al., 1993). | Fatigue was present in 120 (80%) of 150 subjects (Tuzun et al., 2021). The post-viral fatigue burden in post-COVID-19 patients was high with a mean total score of 15.1 (5.0) points (out of 33)(Stavem et al., 2021). |

| Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspnea Questionnaire (PFSDQ-M) | Assesses the impact of fatigue on the activities of daily living in a domain ranging from 0 to 100 points(Lareau, Meek, and Roos 1998). | Fatigue had a positive association with functional status ( r = 0.491, p = 0.045) among participants with COVID-19(Carter et al., 2022). |

Legend: NE (NOT EVALUATED).

4.2. Cognitive function in the assessment of mental fatigue

Mental fatigue manifests as impaired cognitive function (Ishii et al., 2014, Jonasson et al., 2018). In addition, impaired cognitive and executive functions have been demonstrated in post-COVID-19 patients (Ortelli et al., 2021, Versace et al., 2021). Attention (Ortelli et al., 2021) and memory (Bungenberg et al., 2022, Molnar et al., 2021) are the most commonly affected functions.

The cognitive function of COVID-19 patients has been evaluated using different measuring instruments, as shown in Table 2. The d2 test of attention revised (d2-R) was used in a cohort study of hospitalized patients, and cognitive impairment was defined as an impaired score (Morin et al., 2021). In addition, many studies (Aiello et al., 2022, Alemanno et al., 2021, Bonizzato et al., 2022, Bungenberg et al., 2022, Daynes et al., 2021, Evans et al., 2021, Patel et al., 2021, Raman et al., 2021, Stallmach et al., 2022) have assessed cognitive function using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), developed for screening assessment of cognitive impairment and widely recognized (Nasreddine et al., 2005). The Mini-Mental State Examination is also a commonly used instrument for detecting impairments in cognitive function (Aiello et al., 2022, Alemanno et al., 2021, Damiano et al., 2022).

Table 2.

Cognitive function assessment instruments used in COVID-19.

| Instrument | Description | Findings in COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| d2-R test | Focused and sustained attention assessment instrument (Brickenkamp, R., Schmidt-Atzert, L. 2010). | Cognitive impairment (defined as an impaired d2-R score) was observed in 61 (38.4%) of 159 patients who were hospitalized for COVID-19 with persistent fatigue(Morin et al., 2021). |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) | Tool used for cognitive screening and detection of mild cognitive impairment (<26 out of 30 points). It has an assessment of 6 cognitive domains: executive functions; visuospatial abilities; short-term memory; language; attention, concentration and working memory; and temporal and spatial orientation(Nasreddine et al., 2005). | A total of 124 (16.2%) of 767 patients with mild to very severe disease showed cognitive impairment (score <23) up to six months after(Evans et al., 2021). Up to 80% of 87 subjects in rehabilitation for COVID-19 sequelae had cognitive dysfunction(Alemanno et al., 2021). Cognitive dysfunction (<26 points) was observed in 23.5% of 355 patients with COVID-19 sequelae(Stallmach et al., 2022). |

| Mini Mental State Examination | Cognitive function evaluation with performance ranging from 0 to 30 points (Folstein, Folstein, and McHugh 1975). | Data from 100 patients with COVID-19 sequelae demonstrated a mean score of 27 (3.36) and 28.22 (1.94)(Aiello et al., 2022). |

| Rey Auditory−Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) | Neuropsychological test for the evaluation of cognitive function. Assesses episodic memory(Moradi et al. 2016). | Up to 67% of patients showed cognitive impairment 4 months after COVID-19(Vannorsdall et al., 2021). |

| Number Span Forward | Attention and working memory assessment (Becker et al., 2021). | The authors detected a high prevalence of cognitive impairment in patients up to six months after COVID-19(Becker et al., 2021). |

| Trail Making Test | Executive function test with divided attention assessment (Llinàs-Reglà et al. 2017). | |

| Hopkins Verbal Learning Test–Revised | Cognitive assessment test - verbal episodic memory (Benedict et al. 1998). |

Becker et al. (2021) used tests to assess memory and attention using the number span forward, trail making test, and Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised (Becker et al., 2021). Vannorsdall et al. (2021) also used the Trail Making Test and Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) (Vannorsdall et al., 2021). The RAVLT was also used in the study by García-Molina et al. (2021) (García-Molina et al., 2021).

Tests adapted for online use are also described. Zhao et al. (2022) assessed aspects of cognition such as memory, attention, motor control, planning, and verbal reasoning skills in a sample of 64 COVID-19 patients (Zhao et al., 2022). Zhou et al. (2020) used iPad-based online neuropsychological testing (Zhou et al., 2020).

4.3. Physical performance in physical fatigue assessment

Physical fatigue is a condition of reduced physical performance and strength. Because of the difficulty initiating or maintaining voluntary motor activities (Chaudhuri and Behan, 2004, Marcora et al., 2009, Rudroff et al., 2020), the assessment of muscle strength, endurance, and performance in physical tests has been performed using various instruments in post-COVID-19 patients ( Table 3).

Table 3.

Physical performance fatigability assessment instruments used in COVID-19.

| Instruments | Descriptions | Findings in COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Six-Minute WalkTest(6MWT) | Functional capacity test. The main outcome is the assessment of distance traveled(Singh et al. 2014). | 147 (12%) of 1248 patients at 1 year after COVID-19 were below the lower limit of normal(L.Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021). |

| Incremental Shuttle Walk Test (ISWT) | Exercise capacity test, with progressive walking and guided by sound signals. The primary endpoint is the assessment of distance walked(Singh et al. 2014). | The average distance for patients with COVID-19 sequelae referred for rehabilitation was 300 (198) meters(EnyaDaynes et al., 2021). |

| Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) | Lower-limb physical performance. Evaluation of balance, gait speed and lower limb strength (Guralnik et al., 1994). | 53 patients (22.3%) of 238 had impaired physical performance 4 months after hospital discharge for COVID-19(Bellan et al., 2021). |

| Maximum Voluntary Isometric Contraction | Maximal voluntary isometric strength evaluation test(Meldrum et al. 2007). | Muscle weakness of the quadriceps and biceps was observed in 86% and 76% of 41 patients without pre-COVID-19 disabilities(Paneroni et al. 2021a). |

| Hand Grip | Dominant hand grip strength test(Bohannon 2015). | The mean strength value observed in 73 female patients was 21.83 kg and in 77 male patients was 36.93. For females with a history of severe COVID-19 the grip strength was lower when compared to non-severe cases(Tuzun et al., 2021). |

| Electromyography | Evaluation of muscle electrical activity (Kane and Oware 2012). | Of the 20 patients with persistent fatigue from COVID-19, 11 (55%) showed changes in electrical activity compatible with myopathy(Agergaard et al., 2021). |

The Incremental Shuttle Walt Test (ISWT) and the six-minute walk test (6MWT) are widely accepted field tests used in patients with respiratory diseases, and the primary endpoint of both is the distance walked (Holland et al., 2014). Regarding COVID-19, studies using the ISWT (Campos et al., 2021, Daynes et al., 2021, Evans et al., 2021) have been conducted, in addition to 6MWT (Bellan et al., 2021, Carenzo et al., 2021, Eksombatchai et al., 2021; C. Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021; L. Huang et al., 2021, Huang et al., 2021; Salles-Rojas et al., 2021). Above all, unlike the 6MWT, the ISWT is a progressive walking test guided by audible beeps and controlled walking speed (Holland et al., 2014).

A short physical performance battery (SPPB) has also been used (Bellan et al., 2021, Evans et al., 2021). This test assesses balance, gait speed, and lower-limb strength. The score is calculated by the sum of the assessment of the three components and can range from 0 to 12 points, with the classification of functional capacity as poor (0–3 points), low (4–6 points), moderate (7–9 points), or good (10–12 points) (Guralnik et al., 1994).

Other physical tests have been described for assessing muscle fatigue, which may also be an exciting tool for measuring physical performance in COVID-19 patients. The Maximal Voluntary Isometric Contraction (MVC) (Paneroni et al., 2021) and submaximal strength assessment (Lou, 2012, Vøllestad, 1997), handgrip strength (Jäkel et al., 2021, Roberts et al., 2011, Tuzun et al., 2021), and electromyography (Agergaard et al., 2021, González-Izal et al., 2012, Schillings et al., 2003, Vøllestad, 1997) are some of the tests described.

5. Practical considerations and perspectives

Data from literature converge on the assumption that fatigue is a complex phenomenon. Various measurement instruments can be used to assess fatigue at different sites. We conclude that post-viral fatigue in post-COVID-19 patients can be assessed not only by self-reported and/or directly assessed symptom perception but also by reduced physical and/or cognitive performance. Follow-up on sequela in patients is essential to identify long-term manifestations and their impact on the quality of life of affected patients (Singh et al., 2020). These assessments could assist the scientific community in clinical research and clinical staff in treatment strategies.

The strength of this review is the implication of the instruments that may be used to assess fatigue and its different sites of manifestation in patients affected by COVID-19. We further understand that a starting point has been established for validation studies of instruments in this population. Assessments using standardized research instruments are important because research methodologies must remain in agreement to obtain more robust conclusions.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the funding sources: Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina (FAPESC, Brazil), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil), and the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil).

References

- Aaronson L.S., Teel C.S., Cassmeyer V., Neuberger G.B., Pallikkathayil L., Pierce J., Press A.N., Williams P.D., Wingate A. Defining and measuring fatigue. Image-- J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 1999;31:45–50. doi: 10.1111/J.1547-5069.1999.TB00420.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agergaard J., Leth S., Pedersen T.H., Harbo T., Blicher J.U., Karlsson P., Østergaard L., Andersen H., Tankisi H. Myopathic changes in patients with long-term fatigue after COVID-19. Clin. Neurophysiol.: Off. J. Int. Fed. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2021;132:1974–1981. doi: 10.1016/J.CLINPH.2021.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed H., Patel K., Greenwood D.C., Halpin S., Lewthwaite P., Salawu A., Eyre L., Breen A., O’Connor R., Jones A., Sivan M. Long-term clinical outcomes in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus outbreaks after hospitalisation or ICU admission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Rehabil. Med. 2020;52 doi: 10.2340/16501977-2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiello E.N., Fiabane E., Manera M.R., Radici A., Grossi F., Ottonello M., Pain D., Pistarini C. Screening for cognitive sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a comparison between the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA. Neurol. Sci.: Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022;43:81–84. doi: 10.1007/S10072-021-05630-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Aly Z., Bowe B., Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2022;2022:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemanno F., Houdayer E., Parma A., Spina A., Del Forno A., Scatolini A., Angelone S., Brugliera L., Tettamanti A., Beretta L., Iannaccone S. COVID-19 cognitive deficits after respiratory assistance in the subacute phase: A COVID-rehabilitation unit experience. PloS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0246590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen D.G., Lamb G.D., Westerblad H. Skeletal muscle fatigue: cellular mechanisms. Physiol. Rev. 2008;88:287–332. doi: 10.1152/PHYSREV.00015.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves, A.C. de B., Bristot, V.J. de O., Limana, M.D., Speck, A.E., Barros, L.S. de, Solano, A.F., Aderbal S. Aguiar, J., 2019, Role of Adenosine A2A Receptors in the Central Fatigue of Neurodegenerative Diseases. 〈https://home.liebertpub.com/caff〉 9, 145–156. 〈https://doi.org/10.1089/CAFF.2019.0009〉.

- Batawi S., Tarazan N., Al-Raddadi R., Al Qasim E., Sindi A., Al Johni S., Al-Hameed F.M., Arabi Y.M., Uyeki T.M., Alraddadi B.M. Quality of life reported by survivors after hospitalization for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS. Health Qual. life Outcomes. 2019;17 doi: 10.1186/S12955-019-1165-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker J.H., Lin J.J., Doernberg M., Stone K., Navis A., Festa J.R., Wisnivesky J.P. Assessment of Cognitive Function in Patients After COVID-19 Infection. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2021.30645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellan M., Soddu D., Balbo P.E., Baricich A., Zeppegno P., Avanzi G.C., Baldon G., Bartolomei G., Battaglia M., Battistini S., Binda V., Borg M., Cantaluppi V., Castello L.M., Clivati E., Cisari C., Costanzo M., Croce A., Cuneo D., De Benedittis C., De Vecchi S., Feggi A., Gai M., Gambaro E., Gattoni E., Gramaglia C., Grisafi L., Guerriero C., Hayden E., Jona A., Invernizzi M., Lorenzini L., Loreti L., Martelli M., Marzullo P., Matino E., Panero A., Parachini E., Patrucco F., Patti G., Pirovano A., Prosperini P., Quaglino R., Rigamonti C., Sainaghi P.P., Vecchi C., Zecca E., Pirisi M. Respiratory and Psychophysical Sequelae Among Patients With COVID-19 Four Months After Hospital Discharge. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/JAMANETWORKOPEN.2020.36142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berth S.H., Leopold P.L., Morfini G. Virus-induced neuronal dysfunction and degeneration. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed. ) 2009;14:5239–5259. doi: 10.2741/3595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogovič P., Lusa L., Korva M., Lotrič-Furlan S., Resman-Rus K., Pavletič M., Avšič-županc T., Strle K., Strle F. Inflammatory immune responses in patients with tick-borne encephalitis: dynamics and association with the outcome of the disease. Microorganisms. 2019;7 doi: 10.3390/MICROORGANISMS7110514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzato S., Ghiggia A., Ferraro F., Galante E. Cognitive, behavioral, and psychological manifestations of COVID-19 in post-acute rehabilitation setting: preliminary data of an observational study. Neurol. Sci.: Off. J. Ital. Neurol. Soc. Ital. Soc. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2022;43:51–58. doi: 10.1007/S10072-021-05653-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyas S., Guével A. Neuromuscular fatigue in healthy muscle: underlying factors and adaptation mechanisms. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2011;54:88–108. doi: 10.1016/J.REHAB.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenu E.W., Staines D.R., Baskurt O.K., Ashton K.J., Ramos S.B., Christy R.M., Marshall-Gradisnik S.M. Immune and hemorheological changes in chronic fatigue syndrome. J. Transl. Med. 2010;8:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald D.S., Rea T.D., Katon W.J., Russo J.E., Ashley R.L. Acute infectious mononucleosis: Characteristics of patients who report failure to recover. Am. J. Med. 2000;109:531–537. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00560-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bungenberg J., Humkamp K., Hohenfeld C., Rust M.I., Ermis U., Dreher M., Hartmann N.U.K., Marx G., Binkofski F., Finke C., Schulz J.B., Costa A.S., Reetz K. Long COVID-19: Objectifying most self-reported neurological symptoms. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2022;9 doi: 10.1002/ACN3.51496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabria M., García-Sánchez C., Grunden N., Pons C., Arroyo J.A., Gómez-Anson B., Estévez García M., del C., Belvís R., Morollón N., Vera Igual J., Mur I., Pomar V., Domingo P. Post-COVID-19 fatigue: the contribution of cognitive and neuropsychiatric symptoms. J. Neurol. 2022;269 doi: 10.1007/S00415-022-11141-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campos, M.C., Nery, T., Cristina, A., Alves, B., Speck, A.E., Soares, D., Vieira, R., Jayce, I., Schneider, C., Paula, M., Matos, P., Arcêncio, L., Silva, A., Junior, A., Aguiar, A.S., 2021, Rehabilitation in Survivors of COVID-19 (RE2SCUE): a nonrandomized, controlled, and open protocol. medRxiv 2021.09.06.21262986. 〈https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.06.21262986〉.

- Carenzo L., Protti A., Dalla Corte F., Aceto R., Iapichino G., Milani A., Santini A., Chiurazzi C., Ferrari M., Heffler E., Angelini C., Aghemo A., Ciccarelli M., Chiti A., Iwashyna T.J., Herridge M.S., Cecconi M. Short-term health-related quality of life, physical function and psychological consequences of severe COVID-19. Ann. Intensive Care. 2021;11 doi: 10.1186/S13613-021-00881-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carfì A., Bernabei R., Landi F. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;324:603–605. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2020.12603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.J., Baranauskas, M.N., Raglin, J.S., Pescosolido, B.A., Perry, B.L., 2022, Functional status, mood state, and physical activity among women with post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. medRxiv: the preprint server for health sciences. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.11.22269088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ceban F., Ling S., Lui L.M.W., Lee Y., Gill H., Teopiz K.M., Rodrigues N.B., Subramaniapillai M., Di Vincenzo J.D., Cao B., Lin K., Mansur R.B., Ho R.C., Rosenblat J.D., Miskowiak K.W., Vinberg M., Maletic V., McIntyre R.S. Fatigue and cognitive impairment in Post-COVID-19 Syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behav., Immun. 2021;101:93–135. doi: 10.1016/J.BBI.2021.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalder T., Berelowitz G., Pawlikowska T., Watts L., Wessely S., Wright D., Wallace E.P. Development of a fatigue scale. J. Psychosom. Res. 1993;37:147–153. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90081-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri A., Behan P.O. Fatigue in neurological disorders. Lancet (Lond., Engl. ) 2004;363:978–988. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15794-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Haupert S.R., Zimmermann L., Shi X., Fritsche L.G., Mukherjee B. Global Prevalence of Post-Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Condition or Long COVID: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J. Infect. Dis. 2022 doi: 10.1093/INFDIS/JIAC136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Wang K., Yu J., Howard D., French L., Chen Z., Wen C., Xu Z. The Spatial and Cell-Type Distribution of SARS-CoV-2 Receptor ACE2 in the Human and Mouse Brains. Front. Neurol. 2021;11 doi: 10.3389/FNEUR.2020.573095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauw D.J., Häuser W., Cohen S.P., Fitzcharles M.A. Considering the potential for an increase in chronic pain after the COVID-19 pandemic. Pain. 2020;161:1694. doi: 10.1097/J.PAIN.0000000000001950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés-Telles A., López-Romero S., Figueroa-Hurtado E., Pou-Aguilar Y.N., Wong A.W., Milne K.M., Ryerson C.J., Guenette J.A. Pulmonary function and functional capacity in COVID-19 survivors with persistent dyspnoea. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2021;288 doi: 10.1016/J.RESP.2021.103644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler D.M., Summers L.H. The COVID-19 Pandemic and the $16 Trillion Virus. JAMA. 2020;324:1495–1496. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2020.19759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher A., Balfanz P., Cornelissen C., Müller A., Bergs I., Marx N., Müller-Wieland D., Hartmann B., Dreher M., Müller T. Follow up of patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Pulmonary and extrapulmonary disease sequelae. Respir. Med. 2020;174 doi: 10.1016/J.RMED.2020.106197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damiano R.F., Caruso M.J.G., Cincoto A.V., de Almeida Rocca C.C., de Pádua Serafim A., Bacchi P., Guedes B.F., Brunoni A.R., Pan P.M., Nitrini R., Beach S., Fricchione G., Busatto G., Miguel E.C., Forlenza O.V. Post-COVID-19 psychiatric and cognitive morbidity: Preliminary findings from a Brazilian cohort study. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2022;75:38–45. doi: 10.1016/J.GENHOSPPSYCH.2022.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, H.E., Assaf, G.S., McCorkell, L., Wei, H., Low, R.J., Re’em, Y., Redfield, S., Austin, J.P., Akrami, A., 2020, Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. medRxiv. 〈https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.12.24.20248802〉. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Daynes E., Gerlis C., Chaplin E., Gardiner N., Singh S.J. Early experiences of rehabilitation for individuals post-COVID to improve fatigue, breathlessness exercise capacity and cognition - A cohort study. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2021;18 doi: 10.1177/14799731211015691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desforges M., Le Coupanec A., Dubeau P., Bourgouin A., Lajoie L., Dubé M., Talbot P.J. Human coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses: underestimated opportunistic pathogens of the central nervous system. Viruses. 2019:12. doi: 10.3390/V12010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eksombatchai D., Wongsinin T., Phongnarudech T., Thammavaranucupt K., Amornputtisathaporn N., Sungkanuparph S. Pulmonary function and six-minute-walk test in patients after recovery from COVID-19: A prospective cohort study. PloS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0257040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Sayed S., Shokry D., Gomaa S.M. Post-COVID-19 fatigue and anhedonia: A cross-sectional study and their correlation to post-recovery period. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2021;41:50–55. doi: 10.1002/npr2.12154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elanwar R., Hussein M., Magdy R., Eid R.A., Yassien A., Abdelsattar A.S., Alsharaway L.A., Fathy W., Hassan A., Kamal Y.S. Physical and Mental Fatigue in Subjects Recovered from COVID-19 Infection: A Case-Control Study. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2021;17:2063–2071. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S317027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellul M.A., Benjamin L., Singh B., Lant S., Michael B.D., Easton A., Kneen R., Defres S., Sejvar J., Solomon T. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:767–783. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans R.A., McAuley H., Harrison E.M., Shikotra A., Singapuri A., Sereno M., Elneima O., Docherty A.B., Lone N.I., Leavy O.C., Daines L., Baillie J.K., Brown J.S., Chalder T., De Soyza A., Diar Bakerly N., Easom N., Geddes J.R., Greening N.J., Hart N., Heaney L.G., Heller S., Howard L., Hurst J.R., Jacob J., Jenkins R.G., Jolley C., Kerr S., Kon O.M., Lewis K., Lord J.M., McCann G.P., Neubauer S., Openshaw P.J.M., Parekh D., Pfeffer P., Rahman N.M., Raman B., Richardson M., Rowland M., Semple M.G., Shah A.M., Singh S.J., Sheikh A., Thomas D., Toshner M., Chalmers J.D., Ho L.P., Horsley A., Marks M., Poinasamy K., Wain L.V., Brightling C.E., Abel K., Adamali H., Adeloye D., Adeyemi O., Adeyemi F., Ahmad S., Ahmed R., Ainsworth M., Alamoudi A., Aljaroof M., Allan L., Allen R., Alli A., Al-Sheklly B., Altmann D., Anderson D., Andrews M., Angyal A., Antoniades C., Arbane G., Armour C., Armstrong N., Armstrong L., Arnold H., Arnold D., Ashworth M., Ashworth A., Assefa-Kebede H., Atkin P., Atkins H., Atkins A., Aul R., Avram C., Baggott R., Baguley D., Baillie J.K., Bain S., Bakali M., Bakau M., Baldry E., Baldwin D., Ballard C., Bambrough J., Barker R.E., Barratt S., Barrett F., Basu N., Batterham R., Baxendale H., Bayes H., Bayley M., Beadsworth M., Beirne P., Bell R., Bell D., Berry C., Betts S., Bhui K., Bishop L., Blaikely J., Bloomfield C., Bloss A., Bolger A., Bolton C.E., Bonnington J., Botkai A., Bourne M., Bourne C., Bradley E., Bramham K., Brear L., Breen G., Breeze J., Briggs A., Bright E., Brightling C.E., Brill S., Brindle K., Broad L., Broome M., Brown J.S., Brown M., Brown J., Brown R., Brown V., Brown A., Brugha T., Brunskill N., Buch M., Bularga A., Bullmore E., Burn D., Burns G., Busby J., Buttress A., Byrne S., Cairns P., Calder P.C., Calvelo E., Card B., Carr L., Carson G., Carter P., Cavanagh J., Chalder T., Chalmers J.D., Chambers R.C., Channon K., Chapman K., Charalambou A., Chaudhuri N., Checkley A., Chen J., Chetham L., Chilvers E.R., Chinoy H., Chong-James K., Choudhury N., Choudhury G., Chowdhury P., Chowienczyk P., Christie C., Clark D., Clark C., Clarke J., Clift P., Clohisey S., Coburn Z., Cole J., Coleman C., Connell D., Connolly B., Connor L., Cook A., Cooper B., Coupland C., Craig T., Crisp P., Cristiano D., Crooks M.G., Cross A., Cruz I., Cullinan P., Daines L., Dalton M., Dark P., Dasgin J., David A., David C., Davies M., Davies G., Davies K., Davies F., Davies G.A., Daynes E., De Silva T., De Soyza A., Deakin B., Deans A., Defres S., Dell A., Dempsey K., Dennis J., Dewar A., Dharmagunawardena R., Diar Bakerly N., Dipper A., Diver S., Diwanji S.N., Dixon M., Djukanovic R., Dobson H., Dobson C., Dobson S.L., Docherty A.B., Donaldson A., Dong T., Dormand N., Dougherty A., Dowling R., Drain S., Dulawan P., Dunn S., Easom N., Echevarria C., Edwards S., Edwardson C., Elliott B., Elliott A., Ellis Y., Elmer A., Elneima O., Evans R.A., Evans J., Evans H., Evans D., Evans R.I., Evans R., Evans T., Fabbri L., Fairbairn S., Fairman A., Fallon K., Faluyi D., Favager C., Felton T., Finch J., Finney S., Fisher H., Fletcher S., Flockton R., Foote D., Ford A., Forton D., Francis R., Francis S., Francis C., Frankel A., Fraser E., Free R., French N., Fuld J., Furniss J., Garner L., Gautam N., Geddes J.R., George P.M., George J., Gibbons M., Gilmour L., Gleeson F., Glossop J., Glover S., Goodman N., Gooptu B., Gorsuch T., Gourlay E., Greenhaff P., Greenhalf W., Greenhalgh A., Greening N.J., Greenwood J., Greenwood S., Gregory R., Grieve D., Gummadi M., Gupta A., Gurram S., Guthrie E., Hadley K., Haggar A., Hainey K., Haldar P., Hall I., Hall L., Halling-Brown M., Hamil R., Hanley N.A., Hardwick H., Hardy E., Hargadon B., Harrington K., Harris V., Harrison E.M., Harrison P., Hart N., Harvey A., Harvey M., Harvie M., Havinden-Williams M., Hawkes J., Hawkings N., Haworth J., Hayday A., Heaney L.G., Heeney J.L., Heightman M., Heller S., Henderson M., Hesselden L., Hillman T., Hingorani A., Hiwot T., Ho L.P., Hoare A., Hoare M., Hogarth P., Holbourn A., Holdsworth L., Holgate D., Holmes K., Holroyd-Hind B., Horsley A., Hosseini A., Hotopf M., Houchen L., Howard L., Howell A., Hufton E., Hughes A., Hughes J., Hughes R., Humphries A., Huneke N., Hurst J.R., Hurst R., Husain M., Hussell T., Ibrahim W., Ient A., Ingram L., Ismail K., Jackson T., Jacob J., James W.Y., Janes S., Jarvis H., Jayaraman B., Jenkins R.G., Jezzard P., Jiwa K., Johnson S., Johnson C., Johnston D., Jolley C., Jolley C.J., Jones I., Jones S., Jones D., Jones H., Jones G., Jones M., Jose S., Kabir T., Kaltsakas G., Kamwa V., Kar P., Kausar Z., Kelly S., Kerr S., Key A.L., Khan F., Khunti K., King C., King B., Kitterick P., Klenerman P., Knibbs L., Knight S., Knighton A., Kon O.M., Kon S., Kon S.S., Korszun A., Kotanidis C., Koychev I., Kurupati P., Kwan J., Laing C., Lamlum H., Landers G., Langenberg C., Lasserson D., Lawrie A., Lea A., Leavy O.C., Lee D., Lee E., Leitch K., Lenagh R., Lewis K., Lewis V., Lewis K.E., Lewis J., Lewis-Burke N., Light T., Lightstone L., Lim L., Linford S., Lingford-Hughes A., Lipman M., Liyanage K., Lloyd A., Logan S., Lomas D., Lone N.I., Loosley R., Lord J.M., Lota H., Lucey A., MacGowan G., Macharia I., Mackay C., Macliver L., Madathil S., Madzamba G., Magee N., Mairs N., Majeed N., Major E., Malim M., Mallison G., Man W., Mandal S., Mangion K., Mansoori P., Marciniak S., Mariveles M., Marks M., Marshall B., Martineau A., Maskell N., Matila D., Matthews L., Mayet J., McAdoo S., McAllister-Williams H., McArdle P., McArdle A., McAulay D., McAuley H., McAuley D.F., McCafferty K., McCann G.P., McCauley H., McCourt P., Mcgarvey L., McGinness J., McGovern A., McGuinness H., McInnes I.B., McIvor K., McIvor E., McMahon A., McMahon M.J., McMorrow L., Mcnally T., McNarry M., McQueen A., McShane H., Megson S., Meiring J., Menzies D., Michael A., Milligan L., Mills N., Mitchell J., Mohamed A., Molyneaux P.L., Monteiro W., Morley A., Morrison L., Morriss R., Morrow A., Moss A., Moss A.J., Moss P., Mukaetova-Ladinska E., Munawar U., Murali E., Murira J., Nassa H., Neill P., Neubauer S., Newby D., Newell H., Newton Cox A., Nicholson T., Nicoll D., Nolan C.M., Noonan M.J., Novotny P., Nunag J., Nyaboko J., O’Brien L., Odell N., Ogg G., Olaosebikan O., Oliver C., Omar Z., Openshaw P.J.M., Rivera-Ortega P., Osbourne R., Ostermann M., Overton C., Oxton J., Pacpaco E., Paddick S., Papineni P., Paradowski K., Pareek M., Parekh D., Parfrey H., Pariante C., Parker S., Parkes M., Parmar J., Parvin R., Patale S., Patel B., Patel S., Patel M., Pathmanathan B., Pavlides M., Pearl J.E., Peckham D., Pendlebury J., Peng Y., Pennington C., Peralta I., Perkins E., Peto T., Petousi N., Petrie J., Pfeffer P., Phipps J., Pimm J., Piper Hanley K., Pius R., Plein S., Plekhanova T., Poinasamy K., Polgar O., Poll L., Porter J.C., Portukhay S., Powell N., Price L., Price D., Price A., Price C., Prickett A., Quaid S., Quigley J., Quint J., Qureshi H., Rahman N., Rahman M., Ralser M., Raman B., Ramos A., Rangeley J., Rees T., Regan K., Richards A., Richardson M., Robertson E., Rodgers J., Ross G., Rossdale J., Rostron A., Routen A., Rowland A., Rowland M.J., Rowland J., Rowland-Jones S.L., Roy K., Rudan I., Russell R., Russell E., Sabit R., Sage E.K., Samani N., Samuel R., Sapey E., Saralaya D., Saratzis A., Sargeant J., Sass T., Sattar N., Saunders K., Saunders R., Saxon W., Sayer A., Schwaeble W., Scott J., Scott K., Selby N., Semple M.G., Sereno M., Shah K., Shah A., Shah P., Sharma M., Sharpe M., Sharpe C., Shaw V., Sheikh A., Shevket K., Shikotra A., Short J., Siddiqui S., Sigfrid L., Simons G., Simpson J., Singapuri A., Singh S.J., Singh C., Singh S., Skeemer J., Smith I., Smith J., Smith L., Smith A., Soares M., Southern D., Spears M., Spencer L.G., Speranza F., Stadon L., Stanel S., Steiner M., Stensel D., Stern M., Stewart I., Stockley J., Stone R., Storrie A., Storton K., Stringer E., Subbe C., Sudlow C., Suleiman Z., Summers C., Summersgill C., Sutherland D., Sykes D.L., Sykes R., Talbot N., Tan A.L., Taylor C., Taylor A., Te A., Tedd H., Tee C.J., Tench H., Terry S., Thackray-Nocera S., Thaivalappil F., Thickett D., Thomas D., Thomas D.C., Thomas A.K., Thompson A.A.R., Thompson T., Thornton T., Thwaites R.S., Tobin M., Toingson G.F., Tong C., Toshner M., Touyz R., Tripp K.A., Tunnicliffe E., Turner E., Turtle L., Turton H., Ugwuoke R., Upthegrove R., Valabhji J., Vellore K., Wade E., Wain L.V., Wajero L.O., Walder S., Walker S., Wall E., Wallis T., Walmsley S., Walsh S., Walsh J.A., Watson L., Watson J., Watson E., Welch C., Welch H., Welsh B., Wessely S., West S., Wheeler H., Whitehead V., Whitney J., Whittaker S., Whittam B., Wild J., Wilkins M., Wilkinson D., Williams N., Williams B., Williams J., Williams-Howard S.A., Willicombe M., Willis G., Wilson D., Wilson I., Window N., Witham M., Wolf-Roberts R., Woodhead F., Woods J., Wootton D., Worsley J., Wraith D., Wright L., Wright C., Wright S., Xie C., Yasmin S., Yates T., Yip K.P., Young B., Young S., Young A., Yousuf A.J., Yousuf A., Zawia A., Zhao B., Zongo O. Vol. 9. 2021. Physical, cognitive, and mental health impacts of COVID-19 after hospitalisation (PHOSP-COVID): a UK multicentre, prospective cohort study; pp. 1275–1287. (The Lancet. Respiratory Med.). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-De-las-peñas C., Martín-Guerrero J.D., Pellicer-Valero Ó.J., Navarro-Pardo E., Gómez-Mayordomo V., Cuadrado M.L., Arias-Navalón J.A., Cigarán-Méndez M., Hernández-Barrera V., Arendt-Nielsen L. Female Sex Is a Risk Factor Associated with Long-Term Post-COVID Related-Symptoms but Not with COVID-19 Symptoms: The LONG-COVID-EXP-CM Multicenter Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022;11:413. doi: 10.3390/JCM11020413/S1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer J., Mahjoub S.Z. Fatigue in healthy and diseased individuals. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. care. 2014;31:562–575. doi: 10.1177/1049909113494748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishbain D.A., Cole B., Cutler R.B., Lewis J., Rosomoff H.L., Rosomoff R.S. Is pain fatiguing? A structured evidence-based review. Pain. Med. 2003;4:51–62. doi: 10.1046/J.1526-4637.2003.03008.X/2/M_PME_03008_T2B.JPEG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda K., Straus S.E., Hickie I., Sharpe M.C., Dobbins J.G., Komaroff A. The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group [see comments] Ann. Intern. Med. 1994;121:953–959. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-121-12-199412150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaber T. Assessment and management of post-COVID fatigue. Prog. Neurol. Psychiatry. 2021;25:36–39. doi: 10.1002/pnp.698. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galea M., Agius M., Vassallo N. Neurological manifestations and pathogenic mechanisms of COVID-19. Neurol. Res. 2022 doi: 10.1080/01616412.2021.2024732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh R., Grach S.L., Ghosh A.K., Bierle D.M., Salonen B.R., Collins N.M., Joshi A.Y., Boeder N.D., Anstine C.V., Mueller M.R., Wight E.C., Croghan I.T., Badley A.D., Carter R.E., Hurt R.T. The Female-Predominant Persistent Immune Dysregulation of the Post-COVID Syndrome. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2022;97:454. doi: 10.1016/J.MAYOCP.2021.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M.N., Hause A.M., Walker C.M., Orange J.S., Hasbun R., Murray K.O. Evaluation of prolonged fatigue post-west nile virus infection and association of fatigue with elevated antiviral and proinflammatory cytokines. Viral Immunol. 2014;27:327–333. doi: 10.1089/vim.2014.0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Molina A., Espiña-Bou M., Rodríguez-Rajo P., Sánchez-Carrión R., Enseñat-Cantallops A. Neuropsychological rehabilitation program for patients with post-COVID-19 syndrome: a clinical experience. Neurol. (Barc., Spain) 2021;36:565–566. doi: 10.1016/J.NRLENG.2021.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Oscos F., Salgado H., Hall S., Thomas F., Farmer G.E., Bermeo J., Galindo L.C., Ramirez R.D., D’Mello S., Rose-John S., Atzori M. The stress-induced cytokine interleukin-6 decreases the inhibition/excitation ratio in the rat temporal cortex via trans-signaling. Biol. Psychiatry. 2012;71:574–582. doi: 10.1016/J.BIOPSYCH.2011.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraudon P., Bernard A. Vol. 117. 2010. Inflammation in neuroviral diseases; pp. 899–906. (Journal of Neural Transmission (Vienna, Austria: 1996)). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass W.G., Subbarao K., Murphy B., Murphy P.M. Mechanisms of host defense following severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (SARS-CoV) pulmonary infection of mice. J. Immunol. 2004;173:4030–4039. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.6.4030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goërtz Y.M.J., Van Herck M., Delbressine J.M., Vaes A.W., Meys R., Machado F.V.C., Houben-Wilke S., Burtin C., Posthuma R., Franssen F.M.E., van Loon N., Hajian B., Spies Y., Vijlbrief H., van ’t Hul A.J., Janssen D.J.A., Spruit M.A. Persistent symptoms 3 months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection: the post-COVID-19 syndrome? ERJ Open Res. 2020;6 doi: 10.1183/23120541.00542-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Izal M., Malanda A., Gorostiaga E., Izquierdo M. Electromyographic models to assess muscle fatigue. J. Electromyogr. Kinesiol.: Off. J. Int. Soc. Electrophysiol. Kinesiol. 2012;22:501–512. doi: 10.1016/J.JELEKIN.2012.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves J.A., Baig K., Buntin M. The Financial Effects and Consequences of COVID-19: A Gathering Storm. JAMA. 2021;326:1909–1910. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2021.18863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y., Korteweg C., McNutt M.A., Gu J. Pathogenetic mechanisms of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Virus Res. 2008;133:4–12. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A., Madhavan M.V., Sehgal K., Nair N., Mahajan S., Sehrawat T.S., Bikdeli B., Ahluwalia N., Ausiello J.C., Wan E.Y., Freedberg D.E., Kirtane A.J., Parikh S.A., Maurer M.S., Nordvig A.S., Accili D., Bathon J.M., Mohan S., Bauer K.A., Leon M.B., Krumholz H.M., Uriel N., Mehra M.R., Elkind M.S.V., Stone G.W., Schwartz A., Ho D.D., Bilezikian J.P., Landry D.W. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guralnik J.M., Simonsick E.M., Ferrucci L., Glynn R.J., Berkman L.F., Blazer D.G., Scherr P.A., Wallace R.B. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J. Gerontol. 1994;49 doi: 10.1093/GERONJ/49.2.M85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heesakkers H., Van Der Hoeven J.G., Corsten S., Janssen I., Ewalds E., Simons K.S., Westerhof B., Rettig T.C.D., Jacobs C., Van Santen S., Slooter A.J.C., Van Der Woude M.C.E., Van Den Boogaard M., Zegers M. Clinical Outcomes Among Patients With 1-Year Survival Following Intensive Care Unit Treatment for COVID-19. JAMA. 2022;327:559–565. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.2022.0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellmuth J., Barnett T.A., Asken B.M., Kelly J.D., Torres L., Stephens M.L., Greenhouse B., Martin J.N., Chow F.C., Deeks S.G., Greene M., Miller B.L., Annan W., Henrich T.J., Peluso M.J. Persistent COVID-19-associated neurocognitive symptoms in non-hospitalized patients. J. Neurovirol. 2021;27:191. doi: 10.1007/S13365-021-00954-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickie I., Davenport T., Wakefield D., Vollmer-Conna U., Cameron B., Vernon S.D., Reeves W.C., Lloyd A. Post-infective and chronic fatigue syndromes precipitated by viral and non-viral pathogens: Prospective cohort study. Br. Med. J. 2006;333:575–578. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38933.585764.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hives L., Bradley A., Richards J., Sutton C., Selfe J., Basu B., Maguire K., Sumner G., Gaber T., Mukherjee A., Perrin R.N. Can physical assessment techniques aid diagnosis in people with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis? A diagnostic accuracy study. BMJ Open. 2017;7:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland A.E., Spruit M.A., Troosters T., Puhan M.A., Pepin V., Saey D., McCormack M.C., Carlin B.W., Sciurba F.C., Pitta F., Wanger J., MacIntyre N., Kaminsky D.A., Culver B.H., Revill S.M., Hernandes N.A., Andrianopoulos V., Camillo C.A., Mitchell K.E., Lee A.L., Hill C.J., Singh S.J. An official European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society technical standard: field walking tests in chronic respiratory disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;44:1428–1446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00150314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J., Jolkkonen J., Zhao C. Neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2 and its neuropathological alterations: Similarities with other coronaviruses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020;119:184. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUBIOREV.2020.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Huang L., Wang, Yeming, Li X., Ren L., Gu X., Kang L., Guo L., Liu M., Zhou X., Luo J., Huang Z., Tu S., Zhao Y., Chen L., Xu D., Li Y., Li C., Peng L., Li Y., Xie W., Cui D., Shang L., Fan G., Xu J., Wang G., Wang Y., Zhong J., Wang C., Wang J., Zhang D., Cao B. Vol. 397. 2021. 6-month consequences of COVID-19 in patients discharged from hospital: a cohort study; pp. 220–232. (Lancet (London, England)). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L., Yao Q., Gu X., Wang Q., Ren L., Wang Y., Hu P., Guo L., Liu M., Xu J., Zhang X., Qu Y., Fan Y., Li X., Li C., Yu T., Xia J., Wei M., Chen L., Li Y., Xiao F., Liu D., Wang J., Wang X., Cao B. 1-year outcomes in hospital survivors with COVID-19: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet (Lond., Engl. ) 2021;398:747–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01755-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C., Anrather J., Kamel H. Effects of COVID-19 on the Nervous System. Cell. 2020;183:16–27. doi: 10.1016/J.CELL.2020.08.028. e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A., Tanaka M., Watanabe Y. Neural mechanisms of mental fatigue. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;25:469–479. doi: 10.1515/REVNEURO-2014-0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jäkel B., Kedor C., Grabowski P., Wittke K., Thiel S., Scherbakov N., Doehner W., Scheibenbogen C., Freitag H. Hand grip strength and fatigability: correlation with clinical parameters and diagnostic suitability in ME/CFS. J. Transl. Med. 2021;19 doi: 10.1186/S12967-021-02774-W. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janbazi L., Kazemian A., Mansouri K., Madani S.P., Yousefi N., Vahedifard F., Raissi G. The incidence and characteristics of chronic pain and fatigue after 12 months later admitting with COVID-19; The Post- COVID 19 syndrome. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022 doi: 10.1097/phm.0000000000002030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson N.P.A.S., Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918-1920 “Spanish” influenza pandemic. Bull. Hist. Med. 2002;76:105–115. doi: 10.1353/BHM.2002.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joli J., Buck P., Zipfel S., Stengel A. Post-COVID-19 fatigue: A systematic review. Front. Psychiatry. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/FPSYT.2022.947973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonasson A., Levin C., Renfors M., Strandberg S., Johansson B. Mental fatigue and impaired cognitive function after an acquired brain injury. Brain Behav. 2018;8 doi: 10.1002/BRB3.1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczynski M., Mylonakis E. 80% of patients with COVID-19 have ≥1 long-term effect at 14 to 110 d after initial symptoms. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022;175:JC10. doi: 10.7326/J21-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K., Sullivan P.F., Evengård B., Pedersen N.L. Premorbid Predictors of Chronic Fatigue. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2006;63:1267–1272. doi: 10.1001/ARCHPSYC.63.11.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B.Z., Shiraishi Y., Mears C.J., Binns H.J., Taylor R. Chronic fatigue syndrome after infectious mononucleosis in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2009;124:189–193. doi: 10.1542/PEDS.2008-1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B.Z., Collin S.M., Murphy G., Moss-Morris R., Wyller V.B., Wensaas K.A., Hautvast J.L.A., Bleeker-Rovers C.P., Vollmer-Conna U., Buchwald D., Taylor R., Little P., Crawley E., White P.D., Lloyd A. The international collaborative on fatigue following infection (COFFI) Fatigue.: Biomed., Health Behav. 2018;6:106–121. doi: 10.1080/21641846.2018.1426086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kida S., Pantazis A., Weller R.O. CSF drains directly from the subarachnoid space into nasal lymphatics in the rat. Anatomy, histology and immunological significance. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 1993;19:480–488. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1993.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.Y., Lee J.S., Son C.G. Systematic review of primary outcome measurements for chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (Cfs/me) in randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9:1–12. doi: 10.3390/jcm9113463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluger B.M., Krupp L.B., Enoka R.M. Fatigue and fatigability in neurologic illnesses: proposal for a unified taxonomy. Neurology. 2013;80:409–416. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0B013E31827F07BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon H.S., Koh S.H. Neuroinflammation in neurodegenerative disorders: the roles of microglia and astrocytes. Transl. Neurodegener. 2020;9 doi: 10.1186/S40035-020-00221-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange G., Steffener J., Cook D.B., Bly B.M., Christodoulou C., Liu W.C., DeLuca J., Natelson B.H. Objective evidence of cognitive complaints in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A BOLD fMRI study of verbal working memory. NeuroImage. 2005;26:513–524. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite L.C., Carvalho L., Queiroz D.M. de, Farias M.S.Q., Cavalheri V., Edgar D.W., Nery B.R. do A., Vasconcelos Barros N., Maldaner V., Campos N.G., Mesquita R. Can the post-COVID-19 functional status scale discriminate between patients with different levels of fatigue, quality of life and functional performance? Pulmonology. 2022 doi: 10.1016/J.PULMOE.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Leon, S., Wegman-Ostrosky, T., Perelman, C., Sepulveda, R., Rebolledo, P.A., Cuapio, A., Villapol, S., 2021, More than 50 Long-term effects of COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv: the preprint server for health sciences. 〈https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.01.27.21250617〉. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lorusso L., Mikhaylova S.V., Capelli E., Ferrari D., Ngonga G.K., Ricevuti G. Immunological aspects of chronic fatigue syndrome. Autoimmun. Rev. 2009;8:287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou J.S. Techniques in assessing fatigue in neuromuscular diseases. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. North Am. 2012;23:11–22. doi: 10.1016/J.PMR.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado M.O., Kang N.Y.C., Tai F., Sambhi R.D.S., Berk M., Carvalho A.F., Chada L.P., Merola J.F., Piguet V., Alavi A. Measuring fatigue: a meta-review. Int. J. Dermatol. 2021;60:1053–1069. doi: 10.1111/IJD.15341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus P., Gunnes N., Tveito K., Bakken I.J., Ghaderi S., Stoltenberg C., Hornig M., Lipkin W.I., Trogstad L., Håberg S.E. Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) is associated with pandemic influenza infection, but not with an adjuvanted pandemic influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2015;33:6173–6177. doi: 10.1016/J.VACCINE.2015.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik P., Patel K., Pinto C., Jaiswal R., Tirupathi R., Pillai S., Patel U. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome (PCS) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL)-A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94:253–262. doi: 10.1002/JMV.27309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkova A., Kudryavtsev I., Starshinova A., Kudlay D., Zinchenko Y., Glushkova A., Yablonskiy P., Shoenfeld Y. Post COVID-19 Syndrome in Patients with Asymptomatic/Mild Form. Pathogens. 2021;10 doi: 10.3390/PATHOGENS10111408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L., Jin H., Wang M., Hu Y., Chen S., He Q., Chang J., Hong C., Zhou Y., Wang D., Miao X., Li Y., Hu B. Neurologic Manifestations of Hospitalized Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77:683–690. doi: 10.1001/JAMANEUROL.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]