Abstract

Plants deploy extracellular and intracellular immune receptors to sense and restrict pathogen attacks. Rapidly evolving pathogen effectors play crucial roles in suppressing plant immunity but are also monitored by intracellular nucleotide-binding, leucine-rich repeat immune receptors (NLRs), leading to effector-triggered immunity (ETI). Here, we review how NLRs recognize effectors with a focus on direct interactions and summarize recent research findings on the signalling functions of NLRs. Coiled-coil (CC)-type NLR proteins execute immune responses by oligomerizing to form membrane-penetrating ion channels after effector recognition. Some CC-NLRs function in sensor–helper networks with the sensor NLR triggering oligomerization of the helper NLR. Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR)-type NLR proteins possess catalytic activities that are activated upon effector recognition-induced oligomerization. Small molecules produced by TIR activity are detected by additional signalling partners of the EDS1 lipase-like family (enhanced disease susceptibility 1), leading to activation of helper NLRs that trigger the defense response.

Keywords: effector, immune receptor, signalling

Introduction

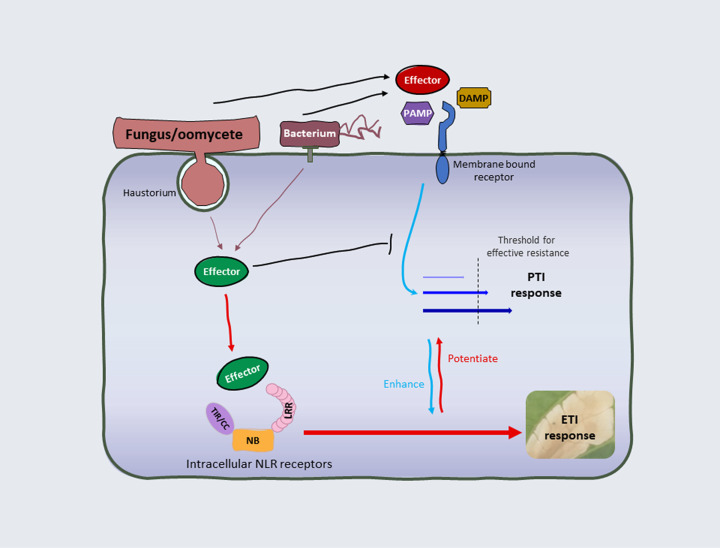

Plants and animals are continuously coresident with microbes, many of which are potential pathogens. While animals deploy specialized mobile cells within a circulatory system as the basis of adaptive immunity, plants rely on a cell-autonomous immune system to detect and restrict pathogen attacks. This comprises two main layers of recognition that operate either at the cell surface or in the host cytoplasm as illustrated in Figure 1 [1–3]. Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) localized in the plasma membrane (PM) monitor the extracellular environment for the presence of pathogens through recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), or apoplastic effector proteins, causing pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) [4–7]. Many adapted pathogens deliver effector proteins directly into plant cells to suppress defense responses including PTI [1,7]. As a countermeasure, plants have evolved a second layer of recognition involving intracellular nucleotide-binding/leucine-rich-repeat receptors (NLRs), which recognize effectors directly or indirectly, inducing effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [1,8]. Although description of the molecular biology of ETI is relatively recent, its existence was first synthesized in the ‘gene-for-gene model’ [9] describing the genetic interaction between host Resistance ‘R’ genes (i.e., NLRs) and pathogen Avirulence ‘Avr’ genes (recognized effectors). PTI provides a broad-spectrum resistance to a wide range of nonadapted pathogens and as such contributes to basal immunity [4,10,11]. ETI provides robust defense responses that are often associated with cell death termed the hypersensitive response (HR) at infection sites to inhibit pathogen proliferation [10,12,13]. There is also evidence for cross-talk between ETI and PTI pathways that can enhance immune responses [14,15]. In this review, we discuss activation of ETI with a focus on the direct recognition of pathogen effectors by plant NLRs and subsequent signalling events, based on the most recent research advances.

Figure 1. Overview of plant immunity.

In the extracellular space, PAMPs, DAMPs, or apoplastic effector proteins released from pathogens are recognized by cell surface membrane-bound receptors, inducing PTI. To suppress PTI, bacterial pathogens inject effectors into the host cell through a type-III secretion system, while fungi and oomycetes develop specialized structures such as haustoria to deliver effectors. Intracellular NLR receptors recognize specific effectors and trigger ETI, which is often associated with cell death at the infection sites. ETI can potentiate PTI by up-regulation of the underlying genes, while activation of PTI can enhance the defense response triggered by ETI. PTI and ETI work together to provide robust effective resistance against pathogens.

NLRs and effector recognition

NLR proteins occur in plants, animals, and fungi and share a basic protein architecture consisting of a conserved central nucleotide-binding (NB) domain, a C-terminal LRR domain, and distinct N-terminal domains. Plant NLRs can be subdivided into two main groups according to their N-terminal domains: those containing an N-terminal TIR (Toll/interleukin-1 receptor and resistance) domain (TIR-NLR or TNL), and those with an N-terminal CC (coiled-coil) domain (CC-NLR or CNL). A subset of CC-NLRs have CC domains related to RPW8 (resistance to powdery mildew 8) and are known as CCR-NLRs or RNLs [16,17]. Generally, the N-terminal CC or TIR domains act as the signalling moieties and are often sufficient to activate downstream responses alone [18–22]. The central NB domain acts as a molecular switch determining the ‘on’ and ‘off’ signalling states of the NLRs by binding ADP or ATP, respectively [23–26]. In many cases, the LRR domain is responsible for the specificity of effector recognition [17,25–27], and congruently, this is often where the greatest polymorphism lies in NLR gene families. However, in other cases, additional noncanonical domains in some NLRs can mediate recognition as described below [25,26].

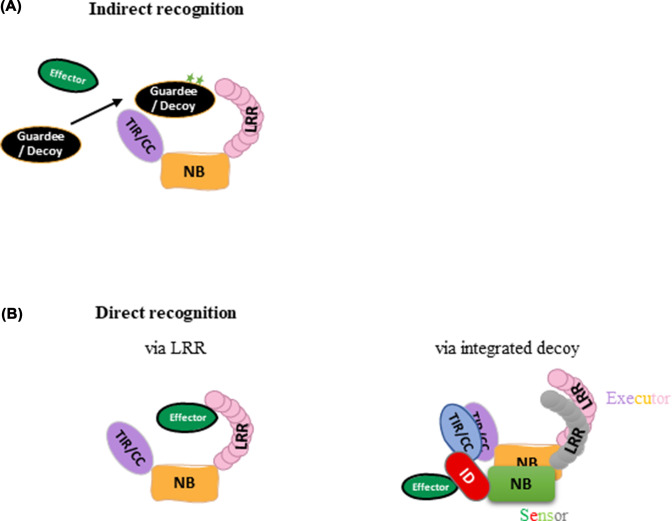

Recognition of effectors in the intracellular space of host cells is a central event in the activation of ETI. Plant NLR proteins can recognize effectors directly by physical interaction or indirectly through an intermediate partner as illustrated in Figure 2 [8,10,28]. Indirect effector recognition by NLRs involves recognition of changes induced in another host protein usually by the enzymatic activity of an effector [8]. Two conceptual models describe such indirect recognition (Figure 2A). In the ‘guard’ model, a host protein that is directly targeted by a pathogen effector as part of its virulence function is guarded by NLR proteins. In the ‘decoy’ model, a protein that mimics the effector target protein mediates recognition. NLR proteins monitor modifications of the ‘guard’ or ‘decoy’ proteins as indicators of pathogen infection that trigger their activation [29]. An advantage of indirect effector recognition for the host is that it is triggered by the function of a pathogen effector, which makes it difficult for the pathogen to escape recognition (i.e., by modifying or losing the effector) without losing a valuable virulence capability [28]. However, this mode of recognition generally requires that the pathogen effector has a protein-modifying activity. Direct recognition on the other hand involves detection of the presence of a pathogen effector by physical interaction with an NLR (Figure 2B), often mediated by the LRR domain [8]. Another mode of recognition is given by the integrated decoy model, which is a combination of direct recognition and the ‘decoy’ model. Here, NLR proteins contain additional integrated domains (ID) that mediate direct recognition by mimicking the protein targets of effectors [28,30–32]. Direct effector recognition has thus far been found more often for eukaryotic filamentous pathogens, whereas indirect recognition has been more often found for bacterial effectors [33,34]. Below we discuss examples of direct recognition between NLR proteins and effectors in more detail.

Figure 2. Models of effector recognition.

Plant NLR proteins recognize effectors (green) either directly or indirectly. (A) Indirect effector recognition occurs through monitoring effector-induced modifications of an intermediate guardee or decoy protein (black). (B) Direct effector recognition often occurs via interaction with the LRR domain (left) or with an ID (red), a decoy protein integrated with the NLR protein that mediates direct effector recognition. Such NLR-ID proteins often occur as part of a sensor/executor NLR pair, with both proteins required for specific resistance.

A number of examples of direct interactions are given in Table 1. One of the first examples to be characterized in detail was between variants of the flax NLR protein, L, and the flax rust fungus effector AvrL567. The specificity of recognition between L5, L6, and L7 and 12 AvrL567 variants is determined by polymorphic amino acids in the LRR domains of the NLR [27,35,36] as well as in surface-exposed residues of the AvrL567 protein [37]. This implies that a physical interface occurs between these regions of the two proteins that underlies recognition. Similarly, the recognition specificity of the barley NLR protein MLA is determined by polymorphisms in the LRR that are involved in physical interaction with AvrMla proteins from the barley powdery mildew pathogen [38]. A wheat homolog of MLA, Sr50, also directly recognizes its corresponding effector AvrSr50 from the wheat stem rust fungus [39]. Some AvrSr50 variants from virulent rust isolates escape Sr50 binding via one or a few mutations on the effector surface [40], while a central region of the LRR is the main contributor to its recognition specificity [41]. Likewise, recognition between the Arabidopsis NLR RPP1 and the downy mildew effector ATR1 involves interaction of effector surface residues with the C-terminal region of RPP1 including the LRR [42,43].

Table 1. Examples of direct receptor–effector recognitions.

| Resistance proteins | NLR type | Organism | Effector | Pathogen | Evidence | Domains involved in recognition | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L5, L6, and L7 | TIR | Linum usitatissimum | AvrL567 | Melampsora lini | Y2H | LRR | [35,36] |

| M | TIR | L. usitatissimum | AvrM | M. lini | Y2H | Unknown | [103,104] |

| L2 | TIR | L. usitatissimum | AvrL2 | M. lini | Y2H | LRR | Unpublished data |

| MLA1, 7, 10, 13 | CC | Hordeum vulgare | AVRa1, 7, 10, 13 | Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei | Y2H | LRR | [105,106] |

| Sr50 | CC | Secale cereale | AvrSr50 | Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici | Y2H | LRR | [39,40] |

| Sr35 | CC | Triticum aestivum | AvrSr35 | P. graminis f. sp. tritici | CoIP, BiFC, structure | LRR | [107,108] |

| RppC | CC | Zea mays L. | AvrRppC | P. polysora | CoIP, BiFC | Unknown | [109] |

| RPP1 | TIR-JID/PL | Arabidopsis thaliana | ATR1 | Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis | Structure | LRR and JID/PL | [26,110,111] |

| ROQ1 | TIR-JID/PL | N. benthamiana | XopQ | Xanthomonas | Structure | LRR and JID/PL | [25,112] |

| N | TIR | N. tabacum | p50 | Tobacco mosaic virus | Y2H | NB-LRR | [113] |

| Pi54 | CC | Oryza sativa | AvrPi54 | Magnaporthe oryzae | Y2H | unknown | [114] |

| Pi-ta | CC-ID | O. sativa | AvrPi-ta | M. oryzae | Y2H | LRR-ID | [115] |

| Sw-5b | CC | Solanum lycopersicum | Nsm | Tomato-spotted wilt virus | CoIP | LRR | [68] |

| RB/Rpi-blb1 | CC | Solanum bulbocastanum | Avrblb1 | Phytophthora infestans | Y2H | CC | [116] |

| Pik-1/Pik-2 | CC-ID/CC | O. sativa | AvrPik | M. oryzae | Structure, Y2H | ID | [117,118] |

| RGA5/RGA4 | CC-ID/CC | O. sativa | AvrPia, AVR1-CO39 | M. oryzae | Y2H | ID | [50,119] |

| RRS1/RPS4 | TIR-ID/TIR | A. thaliana | PopP2 | Ralstonia solanacearum | Y2H | ID | [48,51,120–122] |

| RRS1/RPS4 | TIR-ID/TIR | A. thaliana | AvrRps4 | Pseudomonas syringae | Structure | ID |

Recent structural determination of the TIR-NLR proteins, ROQ1 and RPP1, in complex with their respective effectors, XopQ1 and ATR1, revealed key insights into the molecular basis of recognition [25,26,44]. In both cases, the LRR domains showed extensive physical contact with the effector proteins. However, in addition to this, a short domain located C-terminal to the LRR domains of ROQ1 and RPP1 called the C-JID/PL domain (jelly roll and Ig-like domain, or post-LRR) also contributed to the direct interaction with each effector. This was centered on a region of the JID/PL domain that shows high sequence variability. Mutagenesis assays confirmed that residues within the LRR and JID/PL domains determine the effector recognition specificity. The JID/PL domain exists in many but not all TIR-NLR proteins across multiple plant species [45,46], and could be a common effector recognition component of TNLs in addition to LRR domains.

NLRs with integrated decoy domains often occur as one member of an NLR pair, in which one protein known as the sensor NLR contains an ID that interacts directly with effectors to induce activation of the alternate executor (or helper) NLR (Figure 2B) [17,28,30,47]. Arabidopsis RRS1/RPS4 [48], rice Pik-1/Pik-2 [49], and RGA5/RGA4 pairs [50] are three well-known examples of paired sensor/executor NLRs. The sensor proteins Pik-1 and RGA5 of rice recognize different effectors from the rice blast fungus that bind to their HMA (heavy-metal associated) IDs and trigger immunity via the executors Pik-2 and RGA4, respectively [49,50]. The RRS1 sensor protein carries a WRKY domain as an ID and recognizes the unrelated bacterial effectors Pseudomonas syringae AvrRps4 and Ralstonia solanacearum PopP2, leading to immune responses mediated by the executor protein RPS4 [48,51]. These effectors normally target host WRKY transcription factors, but their action on the RRS1 WRKY ID leads to effector recognition. In the case of AvrRps4, physical interaction of the effector with the RRS1 WRKY domain disrupts an intramolecular interaction with another C-terminal domain thereby destabilizing the inactive state of the protein complex [52]. Overexpression of the executor NLRs, RPS4 and RGA4, causes autoactive cell death in planta, but overexpression of the sensor NLRs, RRS1 and RGA5, does not [53,54]. Moreover, the autoactivity of these executor NLRs can be suppressed by coexpression of RRS1 or RGA5. Hence, sensor NLRs can act as suppressors in some cases to inhibit executor NLRs in the absence of effector recognition. However, in other cases, paired NLRs work co-operatively. For instance, the rice CC-NLR pair Pikp-1/Pikp-2 requires both NLRs to trigger cell death, and neither of them is autoactive when expressed alone [55].

NLR resistosomes and immune signalling

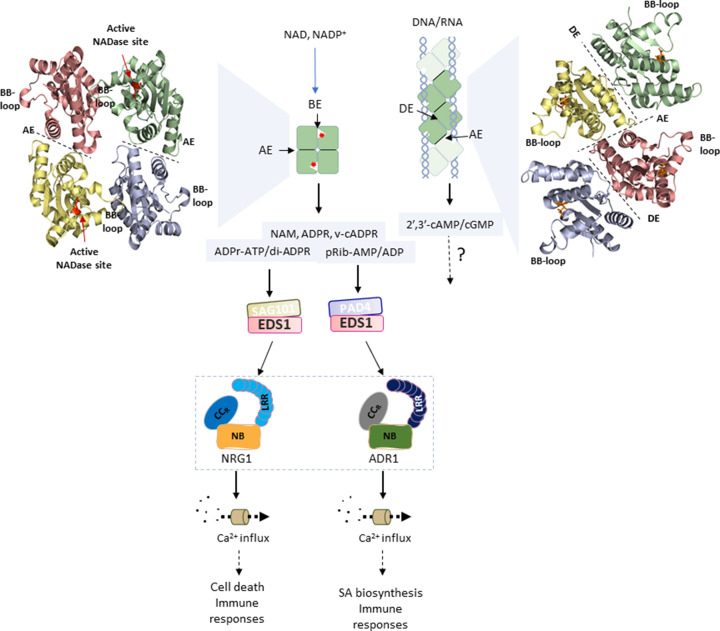

Several early studies showed that self-association of the TIR or CC signalling domains is a precondition of cell death activity. For example, mutations that disrupt the self-association of Sr33 or MLA10 CC domains abolish the cell death caused by either expression of the CC domain alone or the full-length CNL protein [21,56]. Similarly, the crystal structures of isolated plant TIR domains contain separate self-interaction interfaces, AE and DE (Figure 3), and mutational analyses have shown that both are necessary for TIR signalling [57–59]. These observations suggested that NLR proteins function via assembly into multimeric signalling complexes after effector detection [60]. In agreement with this, there is now direct structural evidence that three different NLRs self-associate to form higher-order ‘resistosome’ protein complexes after effector recognition [25,26,61], discussed in further detail below.

Figure 3. Working model for TIR activation and signalling pathways.

Upon TIR-NLR activation, resistosome formation causes the TIR domains (indicated by the green squares in the schematic model) to oligomerize through AE and BE interfaces to activate NADase activity, which cleaves NAD or NADP+ to generate various small molecules and ADP-ribosylation products (left). Alternatively, TIR domains may also self-associate through AE and DE interfaces to form helical filaments, which can bind and hydrolyze DNA/RNA and generate 2′,3′-cAMP/cGMP (right). Extreme left: Roq1TIR tetramer cryo-EM structure (PDB: 7JLX). Extreme right: L6TIR (PDB: 3OZI) tetramer structural model assembled through AE and DE interfaces. The TIR monomer subunit structures are shown in green, yellow, lavender, and salmon with the catalytic glutamate residues shown in red in the resistosome tetramer (left) and in orange in the AE–DE filament (right). The NADase activity products ADPr-ATP/di-ADPR bind to EDS1/SAG101 complexes, while pRibAMP/ADP binds to EDS1/PAD4 complexes. This results in activation of their helper CCR-NLRs, NRG1, and ADR1, respectively. NRG1s promote cell death, whereas ADR1s induce SA biosynthesis, achieved by triggering Ca2+ influx or through some other unknown mechanism(s). Solid arrows indicate confirmed links, dotted arrows indicate tentative pathways.

CC-NLR activation and immune signalling

Structural determination of complexes containing the full-length CC-NLR protein ZAR1 revealed major conformational changes during its activation. This work identified three structural phases: an inactive monomeric state, an intermediate preactivation monomeric state, and the active state, which forms a wheel-like pentameric resistosome complex [24,61]. Inactive ZAR1 binds ADP, while an RKS1 pseudokinase molecule interacts with the LRR domain. This prerecognition complex detects the Xanthomonas effector AvrAC indirectly via a decoy protein kinase, PBS1-like protein 2 (PBL2). After uridylation by AvrAC, PBL2UMP interacts with the ZAR1-RKS1 complex through RKS1, causing outwards rotation of the ZAR1 NB domain, which promotes ADP release and subsequent ATP binding. ATP binding induces further structural changes that assist formation of the active pentameric structure. The N-terminal α1 helix of the CC domain is exposed upon ZAR1 activation and in the resistosome complex, the five CC domains form a funnel-shaped structure with the α1 helices at the apex. The active ZAR1 resistosome associates with the PM and can act as a Ca2+ influx channel [61–64]. Mutation of negatively charged residues within the funnel-shaped CC domain structure abolish ion transport and cell death activity, suggesting that this structure inserts into the membrane to form a Ca2+ permeable channel that is necessary for immunity activation. Newly published research shows that the isolated CC domain of the Arabidopsis helper CCR-NLR NRG1.1 also adopts a four-helical bundle structure that closely resembles those of other plant CC domains and the inactive state of ZAR1 [18]. Moreover, the active AtNRG1.1 protein oligomerizes and forms puncta in the PM, and both activated AtNRG1.1 and AtADR1 can cause Ca2+ influx. Both channel activity and cell death induction also require conserved negatively charged residues in the N-terminal of the CC domains, as observed for ZAR1. This suggests that the CCR domains of these proteins function similarly to the CC domains of other CNL proteins. Moreover, transcriptome analysis revealed that similar gene expression changes are triggered by activation of both CCR-NLRs and other CNLs [18,65]. Hence, formation of Ca2+ permeable channels might be a common mechanism for immune activation by CC-NLRs. There are, however, exceptions to this model. For instance, many of the CC-NLRs in the Solanaceae family operate within a sensor-helper network, where a variety of sensor CC-NLRs are involved in pathogen detection but require helper CC-NLRs of the NRC family to induce immune responses [66,67]. For instance, Sw-5b (Table 1) acts as a sensor that directly interacts with the Nsm protein of tomato-spotted wilt virus and requires NRC family helper NLRs for signalling [67,68]. A recent preprint [69] suggests that pathogen recognition by sensor CC-NLRs in this family leads to oligomerization and membrane association of the NRC helpers.

TIR-NLR activation and immune signalling

TIR-NLRs adopt a very different signalling strategy compared with CC-NLRs. TIR domains possess NADase catalytic activity; upon self-association, TIRs hydrolyze NAD+ and generate a variant-cyclic-ADP-ribose products (v-cADPR), which is hypothesized to activate downstream signalling [19,20]. The TIR domain of the animal SARM1 protein and some bacterial and archaeal TIRs were first shown to have intrinsic NAD+ hydrolase activity [70,71]. Plant TIRs share similar structures to that of SARM1 TIR and possess NADase activity dependent on a conserved glutamate residue, albeit at much lower levels than SARM1 [19,20]. The NADase activity of isolated plant TIR domains requires self-association, with mutations in the AE or DE interfaces abolishing the NADase activity (as well as cell death signalling), while the activity can be enhanced by using molecular-crowding agents (e.g., polyethylene glycol) that promote self-association by increasing the effective protein concentration [19,20]. These observations suggest that plant TIRs need to form higher order structures for NADase activation.

The TIR-NLR proteins ROQ1 from Nicotiana benthamiana and RPP1 from Arabidopsis recognize their cognate effectors directly [25,26]. Unlike the ZAR1 resistosome that forms a disc-like pentamer structure with the N-terminal CC domain helix protruding from its center, ROQ1 and RPP1 form tetrameric structures more like a triple-layered cylinder. Four LRR-JID/PL domain-effector complexes spread out at the one end, while the NB domains oligomerize in the center and thereby drive the TIR domains to self-associate at the other end of the cylinder. TIR domain self-association occurs through two AE and BE interfaces as two asymmetric pairs (Figure 3). While the AE interface is conserved between the resistosome and isolated TIR domain structures, the BE interface is unique to the resistosome and was not observed in TIR X-ray structures, although it does involve some of the same residues involved in the DE interface. Formation of the ROQ1 and RPP1 tetramers exposes two NADase catalytic sites in the two BE interfaces, such that the tetramer includes two NADase-active TIR domains and two inactive domains. Fusion of plant TIRs to the multimerization domain of SARM1 (octamer-forming) or to NLRC4 (which contains about ten protomers in an open-ended ring) can activate cell death signalling in N. benthamiana [19,72]. Thus, TIR oligomerization works upstream of activation of NADase activity, and the stoichiometry of the activated TIR complex is not strictly limited to tetrameric structures. The presence of the BE interface in these resistosomes in place of the DE interface in some TIR-alone crystal structures suggested the possibility that the latter could be a crystal artefact. However, a recent study showed that the plant L7 TIR domain forms helical filaments with AE and DE interfaces that bind to dsDNA or dsRNA molecules within the helical groove and can hydrolyze these molecules to release 2′,3′-cAMP/cGMP [73]. This activity depends on the same active site residues involved in NADase activity. Hence, plant TIRs may adopt different interface combinations (AE+DE or AE+BE; Figure 3) to initiate either 2′,3′-cAMP/cGMP synthetase or NADase activity, respectively, which could both contribute to generation of downstream signalling molecules, possibly with different signalling outcomes [73].

Signalling convergence and distribution: EDS1 and helper NLRs

Two levels of signalling components are required downstream of the TIR domain catalytic activity (NADase/2′,3′-cAMP/cGMP synthetase) leading to resistance outputs (Figure 3). The first level consists of members of the EDS1 family of lipase-like proteins. EDS1 forms mutually exclusive heterodimers with its family members PAD4 (phytoalexin deficient) or SAG101 (senescence-associated gene) [74–77]. The second level is composed of the helper CCR-NLRs, NRG1 and ADR1, that work co-operatively with either the EDS1-SAG101 or EDS1-PAD4 heterodimers, respectively, to mediate immunity [16,78–82]. It remains unclear how immune signals are transferred from TIRs to these downstream signalling partners.

EDS1 family proteins feature an N-terminal lipase-like α/β-hydrolase-fold domain and a C-terminal EP domain (named from the EDS1-PAD4 interaction), which is composed primarily of α-helical bundles [77]. Both EDS1 and PAD4 contain a conserved SDH catalytic triad in the lipase-like domain, and the EP domains have a conserved EPLDIA motif with unknown function [77,83–86]. The solved Arabidopsis EDS1-SAG101 heterodimer structure and the modelled EDS1-PAD4 complex show that the two heterodimers adopt similar interaction profiles [77]. Their interaction is mainly mediated by the N-terminal domains, with the αH helix in the EDS1 N-terminal lipase-like domain fitting neatly into the groove of the N-terminal domain of PAD4 or SAG101. The C-terminal EP domains interact weakly, creating cavity surfaces that are necessary for immune signalling mediated by both EDS1 heterodimers [77,79,83,84,86–88]. One hypothesis has been that the products of TIR catalytic activity bind to this cavity to modify EDS1 heterodimers, and two recent preprints confirm this hypothesis. Huang et al. [89] show that TIR catalytic activity results in the production of phosphoribosyl-AMP/ADP, which binds to the EDS1/PAD4 complex, while Jia et al. [90] show that TIR activity also leads to ADPr-ATP production and binding to the EDS1/SAG101 complex. In both cases, small-molecule binding causes conformational changes in the EDS1 complexes and results in engagement with the ADR1 or NRG1 helper NLRs, respectively.

The helper CCR-NLRs, ADR1 and NRG1, represent an ancient branch of the CC-NLR gene family that occurs in widely diverged plant lineages. This family is usually represented by only one or a few copies within each species in contrast with the broad diversity of other CNL and TNL families. CCR-NLRs from various species, especially Arabidopsis, are required for the function of all tested TNLs and some CNLs [16,65,91–94]. Studies in Arabidopsis revealed that ADR1 and NRG1 function differently: generally, AtADR1s are used by both TNLs and CNLs and function upstream of the SA pathway to restrict pathogen growth, whereas AtNRG1s function mainly for cell death induction by TNLs. AtADR1s and AtNRG1s work synergistically to provide effective resistance [78–81]. However, another study showed that ADR1 can also mediate cell death induced by RRS1/RPS4 in Arabidopsis when NRG1s and the SA pathway are blocked [95]. Transient overexpression of Solanum tuberosum ADR1 (StADR1) or NbNRG1 induces a resistance response that suppresses the accumulation of potato virus X without visible HR [16,91]. Thus, it is reasonable to conclude that both ADR1 and NRG1 possess transcriptional reprogramming and cell death-inducing capacities [95]. EDS1-PAD4 and EDS1-SAG101 heterodimers form two parallel signalling pathways with ADR1 and NRG1 acting downstream, respectively [79,81,86,87]. Several studies have suggested that the EDS1-SAG101 heterodimer works together with NRG1 in inducing cell death triggered by TIR-NLRs, whereas the EDS1-PAD4 heterodimer acting with ADR1 provides broader transcriptional defense in basal immunity used by both TNLs and CNLs [79,86,88,96,97]. All TIR-NLRs tested so far in N. benthamiana require EDS1-SAG101 and NRG1 for activation of immunity [79,80,87], while the NbEDS1–NbPAD4–NbADR1 module has not yet been shown to contribute to immunity in N. benthamiana. An expression profiling study showed that NbNRG1 is required for 80% of the transcriptional changes induced by recognition of the bacterial XopQ1 effector in N. benthamiana, suggesting a major role in this response [80]. The remaining 20% of transcriptional changes may be controlled by other signalling proteins, possibly including NbADR1. The entire Arabidopsis AtEDS1–AtSAG101–AtNRG1 module can be transferred into N. benthamiana to mediate TIR-NLR-triggered immunity [79]. However, combinations of these genes derived from different species (e.g., AtEDS1 plus NbSAG101), or the AtEDS1–AtPAD4–AtADR1 module, cannot confer cell death mediated by TIR-NLRs or restriction of pathogen growth in N. benthamiana [79,86,91]. This supports the idea that EDS1 family proteins and helper CCR-NLRs coevolved separately in different species.

In summary, EDS1 family proteins seem to act as a signalling convergence node where the EDS1-PAD4 and EDS1-SAG101 heterocomplexes work complementarily to collect immune signals from NLRs. These heterocomplexes further activate either ADR1 or NRG1 to execute different immune responses, which require their CCR domains and Ca2+ channel activity. A reasonable hypothesis is that the EDS1 family node evolved as an adapter complex to connect TNLs to a pre-existing CNL signalling pathway. No TNL, SAG101, or NRG1 proteins exist in monocots, but the monocot TIR-only protein BdTIR possesses NADase activity and can induce EDS1- and NRG1-dependent cell death in N. benthamiana [16,20,79,83]. It would therefore be interesting to learn how TIR-only proteins function in monocot plants. Little is known of the physical connections between NLRs and EDS1. Some Arabidopsis TNLs including RPS4, RPS6, and SNC1 have been reported to interact with EDS1 [53,98–100]. Effector-dependent associations between EDS1-SAG101 and NRG1, and EDS1-PAD4 and ADR1, have been proposed in Arabidopsis based on genetic and molecular evidence [95]. However, how immune signalling is transferred from NLRs to the EDS1 node and then activates helper RNLs remains unclear. Apart from mediating ETI triggered by plant intracellular NLRs, the EDS1-PAD4-ADR1 module is reported to participate in immune responses mediated by the cell surface receptor RLP23, suggesting that it may also function as a convergence point for PTI and ETI [101]. Two recent studies in Arabidopsis reported that PTI and ETI mutually reinforce each other during resistance (Figure 1) [14,15]. The authors argue that PTI provides the primary defense against most pathogens, and that ETI mediated by intracellular NLR proteins enhances the transcription and protein stability of PRR signalling components, reversing the attenuation of PTI caused by pathogens. Conversely, ETI responses could be strongly enhanced by activation of plant cell surface immune receptors [102].

Summary

Plant NLRs have evolved direct and indirect recognition mechanisms to detect pathogens. Direct recognition is the dominant form in resistance to biotrophic filamentous pathogens such as fungi and oomycetes.

Selection imposed by direct recognition leads to evolution of effector proteins through modification of surface residues that prevent interaction with host receptors.

CNL and TNL proteins assemble into higher-order resistosomes after effector recognition. In CNL resistosomes, the CC domains seem to act as Ca2+ channels on the PM while oligomerization of TNLs activates TIR domain enzymatic functions that produce potential signalling molecules.

EDS1–PAD4–ADR1 and EDS1–SAG101–NRG1 modules work differently and synergistically for ETI.

Mapping physical connections between TIR-NLRs, EDS1 family proteins and NRG1 or ADR1, are required to understand immune signal transmission during ETI.

Abbreviations

- CC

coiled-coil

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- EDS1

enhanced disease susceptibility 1

- EP

EDS1-PAD4

- ETI

effector-triggered immunity

- HMA

heavy-metal associated

- HR

hypersensitive response

- ID

integrated domain

- NB

nucleotide-binding

- NLR

nucleotide-binding, leucine-rich repeat immune receptor

- PAD4

phytoalexin deficient

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- PBL2

PBS1-like protein 2

- PRR

Pattern recognition receptor

- PTI

pattern-triggered immunity

- RPW8

resistance to powdery mildew 8

- SAG101

senescence-associated gene

- StADR1

Solanum tuberosum ADR1

- TIR

Toll/interleukin-1 receptor

- v-cADPR

variant-cyclic-ADP-ribose

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Funding

JC was supported by a Chinese Scholarship Council (CSC) postgraduate fellowship. PND and JPR also acknowledge support by the Australian Research Council Discovery program grant DP170102902.

Author Contribution

JC drafted the manuscript and all the authors contributed to writing, reviewing, and editing of the final version.

References

- 1.Jones J.D. and Dangl J.L. (2006) The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329 10.1038/nature05286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F.M. (2005) Are innate immune signaling pathways in plants and animals conserved? Nat. Immunol. 6, 973–979 10.1038/ni1253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen Q.M., Iswanto A.B.B., Son G.H. and Kim S.H. (2021) Recent advances in effector-triggered immunity in plants: new pieces in the puzzle create a different paradigm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4709 10.3390/ijms22094709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Couto D. and Zipfel C. (2016) Regulation of pattern recognition receptor signalling in plants. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 537–552 10.1038/nri.2016.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Wit P.J. (2016) Apoplastic fungal effectors in historic perspective; a personal view. New Phytol. 212, 805–813 10.1111/nph.14144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schellenberger R., Touchard M., Clement C., Baillieul F., Cordelier S., Crouzet J.et al. (2019) Apoplastic invasion patterns triggering plant immunity: plasma membrane sensing at the frontline. Mol. Plant Pathol. 20, 1602–1616 10.1111/mpp.12857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naveed Z.A., Wei X.Y., Chen J.J., Mubeen H. and Ali G.S. (2020) The PTI to ETI continuum in phytophthora-plant interactions. Front. Plant Sci. 11, 593905 10.3389/fpls.2020.593905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dodds P.N. and Rathjen J.P. (2010) Plant immunity: towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 539–548 10.1038/nrg2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flor H.H. (1971) Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 9, 275–296 10.1146/annurev.py.09.090171.001423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cui H.T., Tsuda K. and Parker J.E. (2015) Effector-triggered immunity: from pathogen perception to robust defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 66, 487–511 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee H.A., Lee H.Y., Seo E., Lee J., Kim S.B., Oh S.et al. (2017) Current understandings of plant nonhost resistance. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 30, 5–15 10.1094/MPMI-10-16-0213-CR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalio R.J.D., Paschoal D., Arena G.D., Magalhaes D.M., Oliveira T.S., Merfa M.V.et al. (2021) Hypersensitive response: from NLR pathogen recognition to cell death response. Ann. Appl. Biol. 178, 268–280 10.1111/aab.12657 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katagiri F. and Tsuda K. (2010) Understanding the plant immune system. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 23, 1531–1536 10.1094/MPMI-04-10-0099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan M., Jiang Z., Bi G., Nomura K., Liu M., Wang Y.et al. (2021) Pattern-recognition receptors are required for NLR-mediated plant immunity. Nature 592, 105–109 , 10.1038/s41586-021-03316-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ngou B.P.M., Ahn H.K., Ding P. and Jones J.D.G. (2021) Mutual potentiation of plant immunity by cell-surface and intracellular receptors. Nature 592, 110–115 , 10.1038/s41586-021-03315-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collier S.M., Hamel L.P. and Moffett P. (2011) Cell death mediated by the N-terminal domains of a unique and highly conserved class of NB-LRR protein. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 24, 918–931 10.1094/MPMI-03-11-0050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duxbury Z., Wu C.H. and Ding P. (2021) A comparative overview of the intracellular guardians of plants and animals: NLRs in innate immunity and beyond. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 72, 155–184 10.1146/annurev-arplant-080620-104948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacob P., Kim N.H., Wu F., El-Kasmi F., Chi Y., Walton W.G.et al. (2021) Plant “helper” immune receptors are Ca(2+)-permeable nonselective cation channels. Science 373, 420–425 10.1126/science.abg7917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horsefield S., Burdett H., Zhang X., Manik M.K., Shi Y., Chen J.et al. (2019) NAD(+) cleavage activity by animal and plant TIR domains in cell death pathways. Science 365, 793–799 10.1126/science.aax1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wan L., Essuman K., Anderson R.G., Sasaki Y., Monteiro F., Chung E.H.et al. (2019) TIR domains of plant immune receptors are NAD(+)-cleaving enzymes that promote cell death. Science 365, 799–803 10.1126/science.aax1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Casey L.W., Lavrencic P., Bentham A.R., Cesari S., Ericsson D.J., Croll T.et al. (2016) The CC domain structure from the wheat stem rust resistance protein Sr33 challenges paradigms for dimerization in plant NLR proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 12856–12861 10.1073/pnas.1609922113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bi G.Z., Su M., Li N., Liang Y., Dang S., Xu J.C.et al. (2021) The ZAR1 resistosome is a calcium-permeable channel triggering plant immune signaling. Cell 184, 3358–3360 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bernoux M., Burdett H., Williams S.J., Zhang X., Chen C., Newell K.et al. (2016) Comparative analysis of the flax immune receptors L6 and L7 suggests an equilibrium-based switch activation model. Plant Cell. 28, 146–159 10.1105/tpc.15.00303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J., Wang J., Hu M., Wu S., Qi J., Wang G.et al. (2019) Ligand-triggered allosteric ADP release primes a plant NLR complex. Science 364, 5868 10.1126/science.aav5868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin R., Qi T., Zhang H., Liu F., King M., Toth C.et al. (2020) Structure of the activated ROQ1 resistosome directly recognizing the pathogen effector XopQ. Science 370, 9993 10.1126/science.abd9993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma S., Lapin D., Liu L., Sun Y., Song W., Zhang X.et al. (2020) Direct pathogen-induced assembly of an NLR immune receptor complex to form a holoenzyme. Science 370, 3069 10.1126/science.abe3069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravensdale M., Bernoux M., Ve T., Kobe B., Thrall P.H., Ellis J.G.et al. (2012) Intramolecular interaction influences binding of the Flax L5 and L6 resistance proteins to their AvrL567 ligands. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1003004 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cesari S. (2018) Multiple strategies for pathogen perception by plant immune receptors. New Phytol. 219, 17–24 10.1111/nph.14877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Hoorn R.A. and Kamoun S. (2008) From Guard to Decoy: a new model for perception of plant pathogen effectors. Plant Cell. 20, 2009–2017 10.1105/tpc.108.060194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cesari S., Bernoux M., Moncuquet P., Kroj T. and Dodds P.N. (2014) A novel conserved mechanism for plant NLR protein pairs: the “integrated decoy” hypothesis. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 606 10.3389/fpls.2014.00606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moffett P. (2016) Using decoys to detect pathogens: an integrated approach. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 369–370 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grund E., Tremousaygue D. and Deslandes L. (2019) Plant NLRs with integrated domains: unity makes strength. Plant Physiol. 179, 1227–1235 10.1104/pp.18.01134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saur I.M.L., Panstruga R. and Schulze-Lefert P. (2021) NOD-like receptor-mediated plant immunity: from structure to cell death. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 305–318 10.1038/s41577-020-00473-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giraldo M.C. and Valent B. (2013) Filamentous plant pathogen effectors in action. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 800–814 10.1038/nrmicro3119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dodds P.N., Lawrence G.J., Catanzariti A.M., Ayliffe M.A. and Ellis J.G. (2004) The Melampsora lini AvrL567 avirulence genes are expressed in haustoria and their products are recognized inside plant cells. Plant Cell. 16, 755–768 10.1105/tpc.020040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dodds P.N., Lawrence G.J., Catanzariti A.M., Teh T., Wang C.I., Ayliffe M.A.et al. (2006) Direct protein interaction underlies gene-for-gene specificity and coevolution of the flax resistance genes and flax rust avirulence genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 8888–8893 10.1073/pnas.0602577103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang C.I.A., Guncar G., Forwood J.K., Teh T., Catanzariti A.M., Lawrence G.J.et al. (2007) Crystal structures of flax rust avirulence proteins AvrL567-A and -D reveal details of the structural basis for flax disease resistance specificity. Plant Cell. 19, 2898–2912 10.1105/tpc.107.053611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shen Q.H., Zhou F.S., Bieri S., Haizel T., Shirasu K. and Schulze-Lefert P. (2003) Recognition specificity and RAR1/SGT1 dependence in barley Mla disease resistance genes to the powdery mildew fungus. Plant Cell. 15, 732–744 10.1105/tpc.009258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen J., Upadhyaya N.M., Ortiz D., Sperschneider J., Li F., Bouton C.et al. (2017) Loss of AvrSr50 by somatic exchange in stem rust leads to virulence for Sr50 resistance in wheat. Science 358, 1607–1610 10.1126/science.aao4810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ortiz D., Chen J., Outram M.A., Saur I.M.L., Upadhyaya N.M., Mago R.et al. (2022) The stem rust effector protein AvrSr50 escapes Sr50 recognition by a substitution in a single surface exposed residue. New Phytol. 234, 592–606 10.1111/nph.18011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tamborski J., Seong K., Liu F., Staskawicz B. and Krasileva K.V. (2022) Engineering of Sr33 and Sr50 plant immune receptors to alter recognition specificity and autoactivity. bioRxiv, 10.1101/2022.03.05.483131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chou S., Krasileva K.V., Holton J.M., Steinbrenner A.D., Alber T. and Staskawicz B.J. (2011) Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis ATR1 effector is a repeat protein with distributed recognition surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13323–13328 10.1073/pnas.1109791108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krasileva K.V., Dahlbeck D. and Staskawicz B.J. (2010) Activation of an Arabidopsis resistance protein is specified by the in planta association of its leucine-rich repeat domain with the cognate oomycete effector. Plant Cell. 22, 2444–2458 10.1105/tpc.110.075358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maruta N., Burdett H., Lim B.Y.J., Hu X.H., Desa S., Manik M.K.et al. (2022) Structural basis of NLR activation and innate immune signalling in plants. Immunogenetics 74, 5–26 10.1007/s00251-021-01242-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dodds P.N., Lawrence G.J. and Ellis J.G. (2001) Six amino acid changes confined to the leucine-rich repeat beta-strand/beta-turn motif determine the difference between the P and P2 rust resistance specificities in flax. Plant Cell. 13, 163–178 , 10.1105/tpc.13.1.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saucet S.B., Esmenjaud D. and Van Ghelder C. (2021) Integrity of the post-LRR domain is required for TIR-NB-LRR function. Mol. Plant Microbe. Interact. 34, 286–296 10.1094/MPMI-06-20-0156-R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burdett H., Bentham A.R., Williams S.J., Dodds P.N., Anderson P.A., Banfield M.J.et al. (2019) The plant “resistosome”: structural insights into immune signaling. Cell Host Microbe. 26, 193–201 10.1016/j.chom.2019.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Le Roux C., Huet G., Jauneau A., Camborde L., Tremousaygue D., Kraut A.et al. (2015) A receptor pair with an integrated decoy converts pathogen disabling of transcription factors to immunity. Cell 161, 1074–1088 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashikawa I., Hayashi N., Yamane H., Kanamori H., Wu J.Z., Matsumoto T.et al. (2008) Two adjacent nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat class genes are required to confer Pikm-specific rice blast resistance. Genetics 180, 2267–2276 10.1534/genetics.108.095034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cesari S., Thilliez G., Ribot C., Chalvon V., Michel C., Jauneau A.et al. (2013) The rice resistance protein pair RGA4/RGA5 recognizes the magnaporthe oryzae effectors AVR-Pia and AVR1-CO39 by direct binding. Plant Cell. 25, 1463–1481 10.1105/tpc.112.107201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sarris P.F., Duxbury Z., Huh S.U., Ma Y., Segonzac C., Sklenar J.et al. (2015) A plant immune receptor detects pathogen effectors that target WRKY transcription factors. Cell 161, 1089–1100 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma Y., Guo H., Hu L., Martinez P.P., Moschou P.N., Cevik V.et al. (2018) Distinct modes of derepression of an Arabidopsis immune receptor complex by two different bacterial effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 10218–10227 10.1073/pnas.1811858115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huh S.U., Cevik V., Ding P., Duxbury Z., Ma Y., Tomlinson L.et al. (2017) Protein-protein interactions in the RPS4/RRS1 immune receptor complex. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006376 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cesari S., Kanzaki H., Fujiwara T., Bernoux M., Chalvon V., Kawano Y.et al. (2014) The NB-LRR proteins RGA4 and RGA5 interact functionally and physically to confer disease resistance. EMBO J. 33, 1941–1959 10.15252/embj.201487923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zdrzalek R., Kamoun S., Terauchi R., Saitoh H. and Banfield M.J. (2020) The rice NLR pair Pikp-1/Pikp-2 initiates cell death through receptor cooperation rather than negative regulation. PloS ONE 15, e0238616 10.1371/journal.pone.0238616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cesari S., Moore J., Chen C., Webb D., Periyannan S., Mago R.et al. (2016) Cytosolic activation of cell death and stem rust resistance by cereal MLA-family CC-NLR proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 10204–10209 10.1073/pnas.1605483113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernoux M., Ve T., Williams S., Warren C., Hatters D., Valkov E.et al. (2011) Structural and functional analysis of a plant resistance protein TIR domain reveals interfaces for self-association, signaling, and autoregulation. Cell Host Microbe 9, 200–211 10.1016/j.chom.2011.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams S.J., Sohn K.H., Wan L., Bernoux M., Sarris P.F., Segonzac C.et al. (2014) Structural basis for assembly and function of a heterodimeric plant immune receptor. Science 344, 299–303 10.1126/science.1247357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X., Bernoux M., Bentham A.R., Newman T.E., Ve T., Casey L.W.et al. (2017) Multiple functional self-association interfaces in plant TIR domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, E2046–E2052 , 10.1073/pnas.162124811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang X., Dodds P.N. and Bernoux M. (2017) What do we know about NOD-like receptors in plant immunity? Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 55, 205–229 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080516-035250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang J., Hu M., Wang J., Qi J., Han Z., Wang G.et al. (2019) Reconstitution and structure of a plant NLR resistosome conferring immunity. Science 364, 5870 10.1126/science.aav5870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bi G., Su M., Li N., Liang Y., Dang S., Xu J.et al. (2021) The ZAR1 resistosome is a calcium-permeable channel triggering plant immune signaling. Cell 184, 3358–3360 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang G., Roux B., Feng F., Guy E., Li L., Li N.et al. (2015) The decoy substrate of a pathogen effector and a pseudokinase specify pathogen-induced modified-self recognition and immunity in plants. Cell Host Microbe 18, 285–295 10.1016/j.chom.2015.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu M., Qi J., Bi G. and Zhou J.M. (2020) Bacterial effectors induce oligomerization of immune receptor ZAR1 in vivo. Mol. Plant 13, 793–801 10.1016/j.molp.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saile S.C., Jacob P., Castel B., Jubic L.M., Salas-Gonzales I., Backer M.et al. (2020) Two unequally redundant “helper” immune receptor families mediate Arabidopsis thaliana intracellular “sensor” immune receptor functions. PLoS Biol. 18, e3000783 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu C.H., Belhaj K., Bozkurt T.O., Birk M.S. and Kamoun S. (2016) Helper NLR proteins NRC2a/b and NRC3 but not NRC1 are required for Pto-mediated cell death and resistance in Nicotiana benthamiana. New Phytol. 209, 1344–1352 10.1111/nph.13764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu C.H., Abd-El-Haliem A., Bozkurt T.O., Belhaj K., Terauchi R., Vossen J.H.et al. (2017) NLR network mediates immunity to diverse plant pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 8113–8118 10.1073/pnas.1702041114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhu M., Jiang L., Bai B.H., Zhao W.Y., Chen X.J., Li J.et al. (2017) The intracellular immune receptor Sw-5b confers broad-spectrum resistance to tospoviruses through recognition of a conserved 21-amino acid viral effector epitope. Plant Cell. 29, 2214–2232 10.1105/tpc.17.00180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Contreras M.P., Pai H., Tumtas Y., Duggan C., Yuen E.L.H., Cruces A.V.et al. (2022) Sensor NLR immune proteins activate oligomerization of their NRC helper. bioRxiv, 10.1101/2022.04.25.489342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Essuman K., Summers D.W., Sasaki Y., Mao X., Yim A.K.Y., DiAntonio A.et al. (2018) TIR domain proteins are an ancient family of NAD(+)-consuming enzymes. Curr. Biol. 28, 421e4–430e4 10.1016/j.cub.2017.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Essuman K., Summers D.W., Sasaki Y., Mao X., DiAntonio A. and Milbrandt J. (2017) The SARM1 Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain possesses intrinsic NAD(+) cleavage activity that promotes pathological axonal degeneration. Neuron 93, 1334e5–1343e5 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Duxbury Z., Wang S., MacKenzie C.I., Tenthorey J.L., Zhang X., Huh S.U.et al. (2020) Induced proximity of a TIR signaling domain on a plant-mammalian NLR chimera activates defense in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 18832–18839 10.1073/pnas.2001185117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yu D., Song W., Tan E.Y.J., Liu L., Cao Y., Jirschitzka J.et al. (2022) TIR domains of plant immune receptors are 2′,3′-cAMP/cGMP synthetases mediating cell death. Cell in press 10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wiermer M., Feys B.J. and Parker J.E. (2005) Plant immunity: the EDS1 regulatory node. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 8, 383–389 10.1016/j.pbi.2005.05.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Feys B.J., Wiermer M., Bhat R.A., Moisan L.J., Medina-Escobar N., Neu C.et al. (2005) Arabidopsis senescence-associated gene101 stabilizes and signals within an enhanced disease susceptibility1 complex in plant innate immunity. Plant Cell. 17, 2601–2613 10.1105/tpc.105.033910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Garcia A.V., Blanvillain-Baufume S., Huibers R.P., Wiermer M., Li G., Gobbato E.et al. (2010) Balanced nuclear and cytoplasmic activities of EDS1 are required for a complete plant innate immune response. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000970 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wagner S., Stuttmann J., Rietz S., Guerois R., Brunstein E., Bautor J.et al. (2013) Structural basis for signaling by exclusive EDS1 heteromeric complexes with SAG101 or PAD4 in plant innate immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 14, 619–630 10.1016/j.chom.2013.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Castel B., Ngou P.M., Cevik V., Redkar A., Kim D.S., Yang Y.et al. (2019) Diverse NLR immune receptors activate defence via the RPW8-NLR NRG1. New Phytol. 222, 966–980 10.1111/nph.15659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lapin D., Kovacova V., Sun X., Dongus J.A., Bhandari D., von Born P.et al. (2019) A coevolved EDS1-SAG101-NRG1 module mediates cell death signaling by TIR-domain immune receptors. Plant Cell. 31, 2430–2455 10.1105/tpc.19.00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Qi T., Seong K., Thomazella D.P.T., Kim J.R., Pham J., Seo E.et al. (2018) NRG1 functions downstream of EDS1 to regulate TIR-NLR-mediated plant immunity in Nicotiana benthamiana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E10979–E10987 10.1073/pnas.1814856115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu Z., Li M., Dong O.X., Xia S., Liang W., Bao Y.et al. (2019) Differential regulation of TNL-mediated immune signaling by redundant helper CNLs. New Phytol. 222, 938–953 10.1111/nph.15665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Jubic L.M., Saile S., Furzer O.J., El Kasmi F. and Dangl J.L. (2019) Help wanted: helper NLRs and plant immune responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 50, 82–94 10.1016/j.pbi.2019.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lapin D., Bhandari D.D. and Parker J.E. (2020) Origins and immunity networking functions of EDS1 family proteins. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 58, 253–276 10.1146/annurev-phyto-010820-012840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Voss M., Toelzer C., Bhandari D.D., Parker J.E. and Niefind K. (2019) Arabidopsis immunity regulator EDS1 in a PAD4/SAG101-unbound form is a monomer with an inherently inactive conformation. J. Struct. Biol. 208, 107390 10.1016/j.jsb.2019.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Feys B.J., Moisan L.J., Newman M.A. and Parker J.E. (2001) Direct interaction between the Arabidopsis disease resistance signaling proteins, EDS1 and PAD4. EMBO J. 20, 5400–5411 10.1093/emboj/20.19.5400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhandari D.D., Lapin D., Kracher B., von Born P., Bautor J., Niefind K.et al. (2019) An EDS1 heterodimer signalling surface enforces timely reprogramming of immunity genes in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 10, 772 10.1038/s41467-019-08783-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gantner J., Ordon J., Kretschmer C., Guerois R. and Stuttmann J. (2019) An EDS1-SAG101 complex is essential for TNL-mediated immunity in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Cell. 31, 2456–2474 10.1105/tpc.19.00099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dongus J.A. and Parker J.E. (2021) EDS1 signalling: at the nexus of intracellular and surface receptor immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 62, 102039 10.1016/j.pbi.2021.102039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Huang S., Jia A., Song W., Hessler G., Meng Y., Sun Y.et al. (2022) Identification and receptor mechanism of TIR-catalyzed small molecules in plant immunity. bioRxiv, 10.1101/2022.04.01.486681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jia A., Huang S., Song W., Wang J., Meng Y., Sun Y.et al. (2022) TIR-catalyzed ADP-ribosylation reactions produce signaling molecules for plant immunity. bioRxiv, 10.1101/2022.05.02.490369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peart J.R., Mestre P., Lu R., Malcuit I. and Baulcombe D.C. (2005) NRG1, a CC-NB-LRR protein, together with N, a TIR-NB-LRR protein, mediates resistance against tobacco mosaic virus. Curr. Biol. 15, 968–973 10.1016/j.cub.2005.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grant J.J., Chini A., Basu D. and Loake G.J. (2003) Targeted activation tagging of the Arabidopsis NBS-LRR gene, ADR1, conveys resistance to virulent pathogens. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 16, 669–680 10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.8.669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Shao Z.Q., Xue J.Y., Wu P., Zhang Y.M., Wu Y., Hang Y.Y.et al. (2016) Large-scale analyses of angiosperm nucleotide-binding site-leucine-rich repeat genes reveal three anciently diverged classes with distinct evolutionary patterns. Plant Physiol. 170, 2095–2109 10.1104/pp.15.01487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Dong O.X., Tong M., Bonardi V., El Kasmi F., Woloshen V., Wunsch L.K.et al. (2016) TNL-mediated immunity in Arabidopsis requires complex regulation of the redundant ADR1 gene family. New Phytol. 210, 960–973 10.1111/nph.13821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sun X., Lapin D., Feehan J.M., Stolze S.C., Kramer K., Dongus J.A.et al. (2021) Pathogen effector recognition-dependent association of NRG1 with EDS1 and SAG101 in TNL receptor immunity. Nat. Commun. 12, 3335 10.1038/s41467-021-23614-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Bonardi V., Tang S., Stallmann A., Roberts M., Cherkis K. and Dangl J.L. (2011) Expanded functions for a family of plant intracellular immune receptors beyond specific recognition of pathogen effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 16463–16468 10.1073/pnas.1113726108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cui H., Gobbato E., Kracher B., Qiu J., Bautor J. and Parker J.E. (2017) A core function of EDS1 with PAD4 is to protect the salicylic acid defense sector in Arabidopsis immunity. New Phytol. 213, 1802–1817 10.1111/nph.14302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bhattacharjee S., Halane M.K., Kim S.H. and Gassmann W. (2011) Pathogen effectors target Arabidopsis EDS1 and alter its interactions with immune regulators. Science 334, 1405–1408 10.1126/science.1211592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Heidrich K., Wirthmueller L., Tasset C., Pouzet C., Deslandes L. and Parker J.E. (2011) Arabidopsis EDS1 connects pathogen effector recognition to cell compartment-specific immune responses. Science 334, 1401–1404 10.1126/science.1211641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim T.H., Kunz H.H., Bhattacharjee S., Hauser F., Park J., Engineer C.et al. (2012) Natural variation in small molecule-induced TIR-NB-LRR signaling induces root growth arrest via EDS1- and PAD4-complexed R protein VICTR in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 24, 5177–5192 10.1105/tpc.112.107235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pruitt R.N., Locci F., Wanke F., Zhang L., Saile S.C., Joe A.et al. (2021) The EDS1-PAD4-ADR1 node mediates Arabidopsis pattern-triggered immunity. Nature 598, 495–499 10.1038/s41586-021-03829-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yuan M., Ngou B.P.M., Ding P. and Xin X.F. (2021) PTI-ETI crosstalk: an integrative view of plant immunity. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 62, 102030 10.1016/j.pbi.2021.102030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Catanzariti A.M., Dodds P.N., Lawrence G.J., Ayliffe M.A. and Ellis J.G. (2006) Haustorially expressed secreted proteins from flax rust are highly enriched for avirulence elicitors. Plant Cell. 18, 243–256 10.1105/tpc.105.035980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Catanzariti A.M., Dodds P.N., Ve T., Kobe B., Ellis J.G. and Staskawicz B.J. (2010) The AvrM effector from flax rust has a structured C-terminal domain and interacts directly with the M resistance protein. Mol. Plant. Microbe. Interact. 23, 49–57 10.1094/MPMI-23-1-0049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Saur I.M., Bauer S., Kracher B., Lu X., Franzeskakis L., Muller M.C.et al. (2019) Multiple pairs of allelic MLA immune receptor-powdery mildew AVRA effectors argue for a direct recognition mechanism. Elife 8, 44471 10.7554/eLife.44471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bauer S., Yu D.L., Lawson A.W., Saur I.M.L., Frantzeskakis L., Kracher B.et al. (2021) The leucine-rich repeats in allelic barley MLA immune receptors define specificity towards sequence-unrelated powdery mildew avirulence effectors with a predicted common RNase-like fold. PLoS Pathog. 17, 9223 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Salcedo A., Rutter W., Wang S.C., Akhunova A., Bolus S., Chao S.M.et al. (2017) Variation in the AvrSr35 gene determines Sr35 resistance against wheat stem rust race Ug99. Science 358, 1604–1606 10.1126/science.aao7294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Förderer A., Li E., Lawson A., Deng Y.-n., Sun Y., Logemann E.et al. (2022) A wheat resistosome defines common principles of immune receptor channels. bioRxiv, 10.1101/2022.03.23.485489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Deng C., Leonard A., Cahill J., Lv M., Li Y., Thatcher S.et al. (2022) The RppC-AvrRppC NLR-effector interaction mediates the resistance to southern corn rust in maize. Mol. Plant 15, 904–912 10.1016/j.molp.2022.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Goritschnig S., Steinbrenner A.D., Grunwald D.J. and Staskawicz B.J. (2016) Structurally distinct Arabidopsis thaliana NLR immune receptors recognize tandem WY domains of an oomycete effector. New Phytol. 210, 984–996 10.1111/nph.13823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Steinbrenner A.D., Goritschnig S. and Staskawicz B.J. (2015) Recognition and activation domains contribute to allele-specific responses of an Arabidopsis NLR receptor to an oomycete effector protein. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004665 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Schultink A., Qi T., Lee A., Steinbrenner A.D. and Staskawicz B. (2017) Roq1 mediates recognition of the Xanthomonas and Pseudomonas effector proteins XopQ and HopQ1. Plant J. 92, 787–795 10.1111/tpj.13715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ueda H., Yamaguchi Y. and Sano H. (2006) Direct interaction between the tobacco mosaic virus helicase domain and the ATP-bound resistance protein, N factor during the hypersensitive response in tobacco plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 61, 31–45 10.1007/s11103-005-5817-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rayi S., Singh P.K., Gupta D.K., Mahato A.K., Sarkar C., Rathour R.et al. (2016) Analysis of Magnaporthe oryzae genome reveals a fungal effector, which is able to induce resistance response in transgenic rice line containing resistance gene, Pi54. Front. Plant Sci. 7, 1140, 10.3389/fpls.2016.01140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jia Y., McAdams S.A., Bryan G.T., Hershey H.P. and Valent B. (2000) Direct interaction of resistance gene and avirulence gene products confers rice blast resistance. EMBO J. 19, 4004–4014 10.1093/emboj/19.15.4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Chen Y., Liu Z. and Halterman D.A. (2012) Molecular determinants of resistance activation and suppression by Phytophthora infestans effector IPI-O. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002595 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Maqbool A., Saitoh H., Franceschetti M., Stevenson C.E., Uemura A., Kanzaki H.et al. (2015) Structural basis of pathogen recognition by an integrated HMA domain in a plant NLR immune receptor. Elife 4, 8709 10.7554/eLife.08709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Kanzaki H., Yoshida K., Saitoh H., Fujisaki K., Hirabuchi A., Alaux L.et al. (2012) Arms race co-evolution of Magnaporthe oryzae AVR-Pik and rice Pik genes driven by their physical interactions. Plant J. 72, 894–907 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Guo L.W., Cesari S., de Guillen K., Chalvon V., Mammri L., Ma M.Q.et al. (2018) Specific recognition of two MAX effectors by integrated HMA domains in plant immune receptors involves distinct binding surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 11637–11642 10.1073/pnas.1810705115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Deslandes L., Olivier J., Peeters N., Feng D.X., Khounlotham M., Boucher C.et al. (2003) Physical interaction between RRS1-R, a protein conferring resistance to bacterial wilt, and PopP2, a type III effector targeted to the plant nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8024–8029 10.1073/pnas.1230660100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tasset C., Bernoux M., Jauneau A., Pouzet C., Briere C., Kieffer-Jacquinod S.et al. (2010) Autoacetylation of the Ralstonia solanacearum effector PopP2 targets a lysine residue essential for RRS1-R-mediated immunity in Arabidopsis. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001202 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mukhi N., Brown H., Gorenkin D., Ding P.T., Bentham A.R., Stevenson C.E.M.et al. (2021) Perception of structurally distinct effectors by the integrated WRKY domain of a plant immune receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2113996118 10.1073/pnas.2113996118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]