Abstract

Background/Aim:

The diagnostic accuracy of brief informant screening instruments to detect dementia in critically ill adults is unknown. We sought to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the 2- to 3-min Ascertain Dementia 8 (AD8) completed by surrogates in detecting dementia among critically ill adults suspected of having pre-existing dementia by comparing it to the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR).

Methods:

This substudy of BRAIN-ICU included a subgroup of 75 critically ill medical/surgical patients determined to be at medium risk of having pre-existing dementia (Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly [IQCODE] score ≥3.3). We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV), and AUC for the standard AD8 cutoff of ≥2 versus the reference standard CDR score of ≥1 for mild dementia.

Results:

By the CDR, 38 patients had very mild or no dementia and 37 had mild dementia or greater. For diagnosing mild dementia, the AD8 had a sensitivity of 97% (95% CI 86–100), a specificity of 16% (6–31), a PPV of 53% (40–65), an NPV of 86% (42–100), and an AUC of 0.738 (0.626–0.850).

Conclusions:

Among critically ill patients judged at risk for pre-existing dementia, the 2- to 3-min AD8 is highly sensitive and has a high NPV. These data indicate that the brief tool can serve to rule out dementia in a specific patient population.

Keywords: Clinical Dementia Rating Scale, Cognitive disorders, Cognitive screening test, Delirium, Dementia, Diagnosis, Critical illness, Sensitivity, Specificity, Ascertain Dementia 8

Introduction

Pre-existing dementia is a major risk factor for delirium in the intensive care unit (ICU) and is prevalent among older adults [1]. The ability to quickly and accurately determine a patient’s baseline, premorbid cognitive status is essential for patients admitted to the ICU in order to guide clinical care and to identify those at high risk for delirium. Delirium superimposed on pre-existing dementia is associated with worse outcomes than in those with dementia alone [2]. However, recognition of pre-existing dementia is challenging because of the limited communication abilities of ICU patients. One study showed that over half of cases of pre-existing dementia are not recognized by ICU physicians [3]. Another challenge to identifying dementia is that it takes time. Reference standard tests, such as the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR], are lengthy. The only dementia screening tool previously studied in the ICU – the Short Form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE] – takes 10–25 min [4]. The Eight-Item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia (Ascertain Dementia 8, AD8] is a 2- to 3-min informant-based screening tool that could be useful in the ICU. Although the AD8 is shorter and more sensitive than the IQCODE [5], its diagnostic accuracy has not been studied in the ICU.

The objective of this substudy of BRAIN-ICU [6] was to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the AD8 in critically ill adults suspected of having pre-existing dementia by comparing it to the CDR. We chose to study this medium-risk group because the enrollment process of BRAIN-ICU excluded the highest-risk group altogether and did not have the personnel to score the lengthy CDR in the large low-risk group. Additionally, patients at medium risk often pose the most diagnostic uncertainty. The AD8 has potential to be a quick triage test in this population that, if positive, could trigger more detailed testing. The AD8 could help to risk-stratify patients to facilitate targeted interventions and could potentially replace time-consuming tests currently used in research studies.

Methods

Study Population and Setting

This investigation was planned a priori as a substudy within the BRAIN-ICU investigation, a multicenter, prospective cohort study approved by the Vanderbilt University IRB.

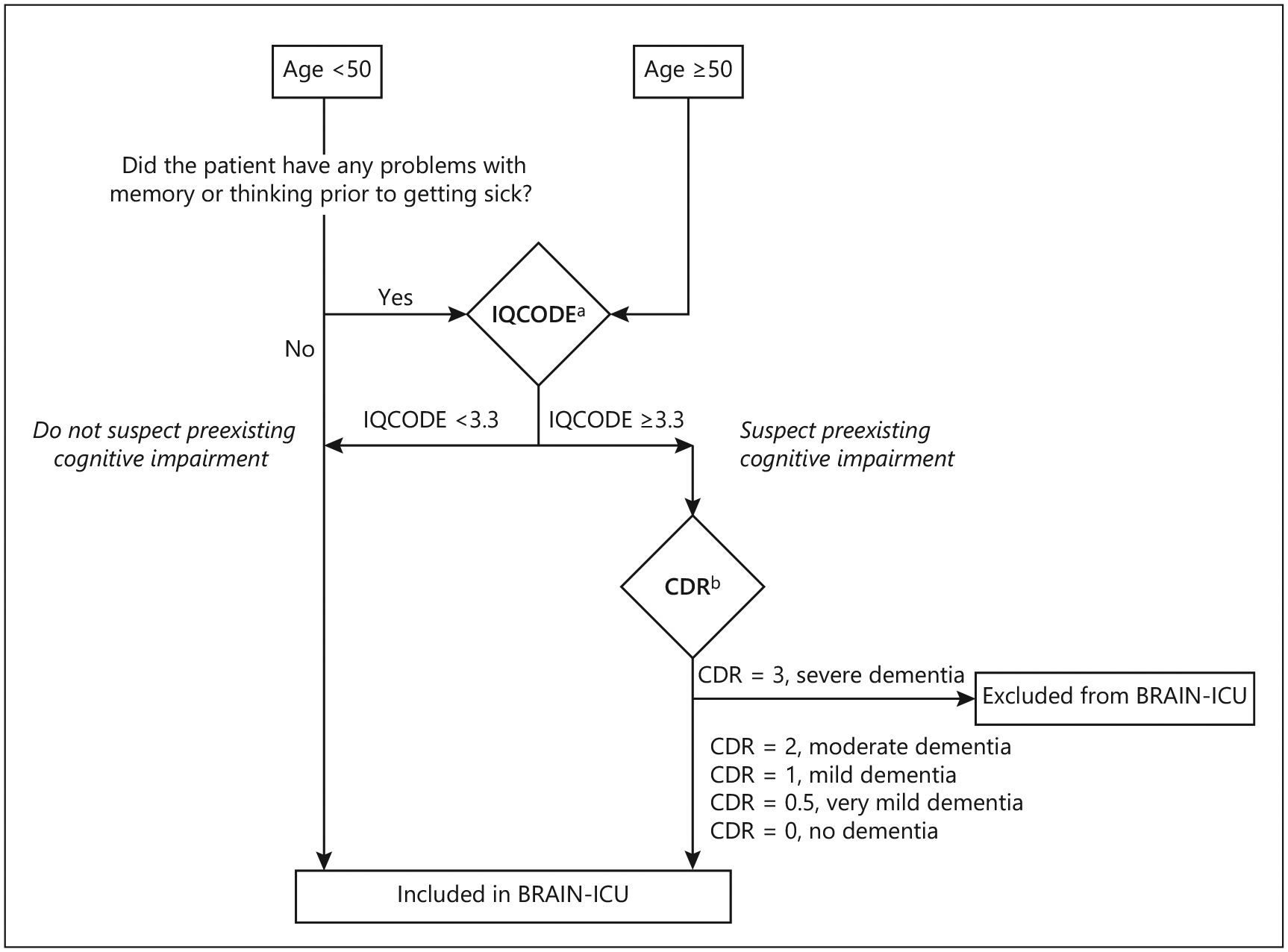

BRAIN-ICU enrolled patients admitted to the surgical or medical ICU with respiratory failure, cardiogenic shock, or septic shock [6]. Because the main purpose of BRAIN-ICU was to identify potentially modifiable risk factors for long-term cognitive impairment after the ICU, patients at highest risk for severe pre-existing dementia were excluded (known neurodegenerative disease, recent cardiac surgery, or anoxic brain injury], as well as those with severe pre-existing dementia (determined via patient history or chart review and/or screening protocol with a CDR score of 3]. For this AD8 substudy, we also excluded those at lowest risk for dementia according to the screening protocol using surrogate-based assessment (Fig. 1). Low-risk individuals were excluded for two reasons: (1) detecting dementia in the “middle-risk” group is often the most challenging, and (2) logistically, administering the lengthy CDR (45-min tool) to both the low- and middle-risk groups was not feasible.

Fig. 1.

Screening protocol for pre-existing cognitive impairment by surrogate assessment. a The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) is a 16-item, informant-based screening tool [31]. IQCODE scores from 3.3 to 3.6 have been shown to be valid for the diagnosis of dementia in a variety of non-ICU settings [4]. b The Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) is a detailed surrogate-based questionnaire designed to detect and stage dementia and commonly used as a gold standard. Because the main aim of the BRAIN-ICU study was to identify potentially modifiable risk factors for long-term cognitive impairment after the ICU, patients with severe dementia (CDR score = 3) were excluded.

In parallel fashion, the AD8 was administered to surrogates of all patients. Because the AD8 was added to the study protocol shortly after the study had already begun, patients who did not receive the AD8 were excluded. Additionally, we excluded patients who were not eligible to undergo the CDR because of low suspicion for pre-existing dementia per the screening protocol (Fig. 1).

Test Methods

The AD8 [7] was used as the index test and was administered to the surrogates of all patients by research coordinators. Though the AD8 was derived from the CDR primarily for detecting Alzheimer disease, it has been shown to reliably identify pre-existing dementia regardless of its etiology [8]. It is a brief informant-based questionnaire with 8 yes/no questions (0–8, higher scores reflecting more cognitive impairment). It is designed to identify intraindividual change over the previous few years in multiple cognitive domains. Prior studies in outpatient settings [5, 9–12], emergency departments [13], and hospitalized older adults with delirium [14] have found sensitivities ranging from 68 to 100% and specificities ranging from 17 to 90% with AUCs of 0.62–0.97. We used a prespecified cutoff of ≥2 to indicate pre-existing dementia, consistent with the majority of prior validation studies.

The CDR was used as the reference standard for diagnosing pre-existing dementia [15]. The CDR, a surrogate-based questionnaire designed to detect and stage dementia, is a “gold standard” due to its robust inter-rater reliability [16] and strong concurrent validity [17]. Importantly, CDR scores derived solely from surrogates have proven accurate [18]. The CDR is scored from 0 to 3 (0 = no dementia, 0.5 = questionable dementia, 1 = mild dementia, 2 = moderate dementia, and 3 = severe dementia) [19]. Experts disagree over whether a CDR score of 0.5 represents “mild cognitive impairment” or “very mild dementia” [20–22]. To be consistent with prior validation studies of the AD8 [8, 9], we used a prespecified and broadly agreed-upon CDR cutoff of 0.5 for very mild dementia and of 1.0 for mild dementia.

The screening questionnaires were administered by CDR-certified research personnel. For both questionnaires, if possible, we selected a surrogate who had known the patient for at least 10 years. Since most participants were not able to complete the CDR interview at enrollment due to critical illness, we used the CDR surrogate-only modification. If possible, the entire interview was completed (including both the surrogate and patient components of the CDR). The CDR was scored independently by one of two doctoral psychologists without access to the AD8 results or clinical information. If there was disagreement, a third psychologist determined the score.

Covariates

Baseline patient characteristics collected upon admission included age, race, gender, marital status, years of education, employment status, history of proxy-reported depression and other mental health illnesses, comorbidity score [23], frailty index [24], and functional status using the Katz Activities of Daily Living [25] and Pfeffer Functional Activities Questionnaire [26]. In-hospital characteristics were collected, including admission diagnosis, ICU type, severity of illness according to the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [27], mechanical ventilation, and delirium. The relation of the surrogate to the patient was also recorded.

Statistical Analysis

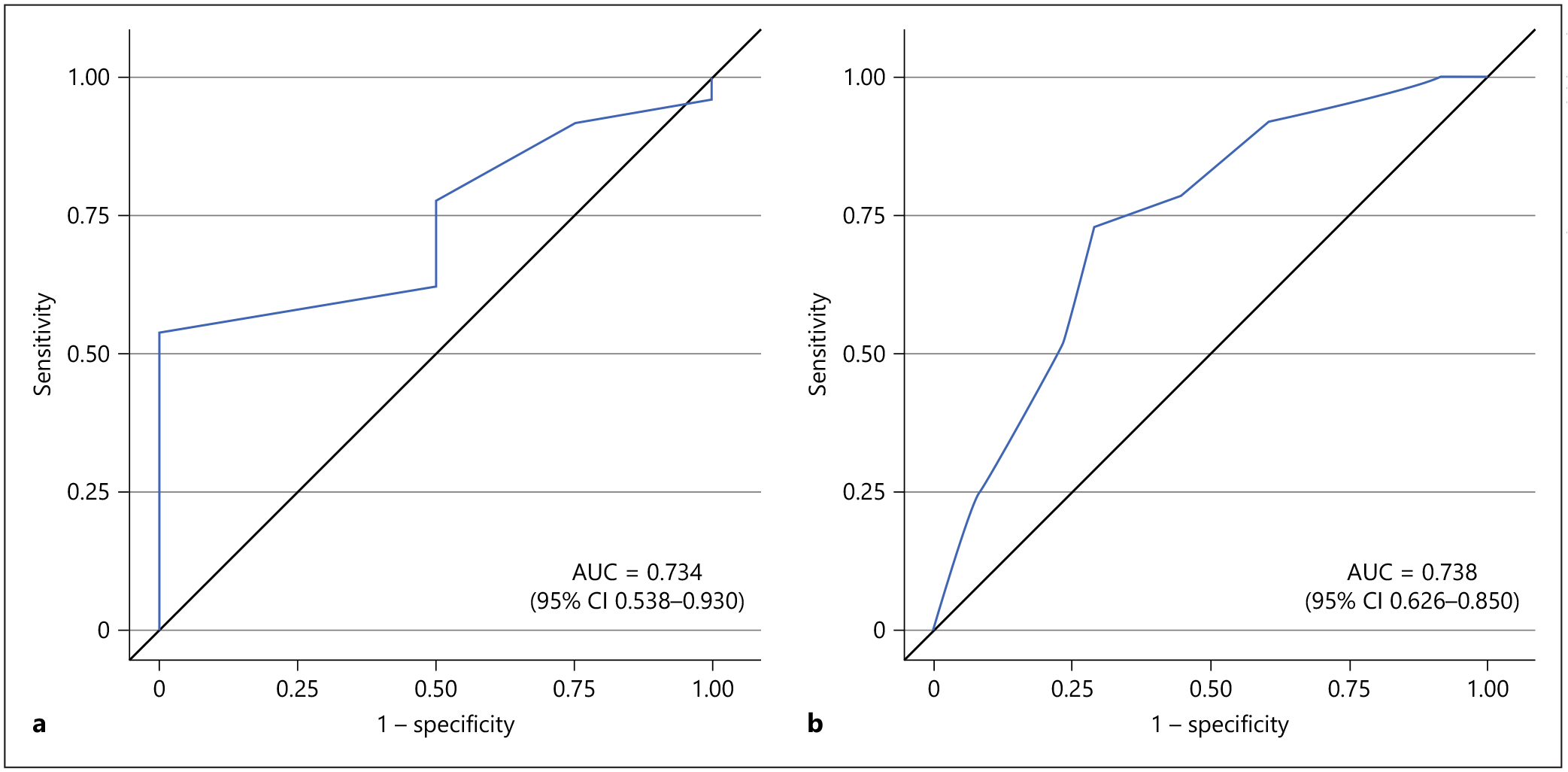

All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 and R version 3.0.1. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, and positive and negative likelihood ratios with 95% CI were calculated for the AD8 using the CDR assessment as the reference standard. We used the previously validated cutoff score of ≥2 for the AD8. We conducted separate analyses, a first using a CDR score of ≥ 0.5 as the reference standard for very mild pre-existing dementia and a second using a CDR score of ≥1 for mild pre-existing dementia. Receiver operating characteristic curves and AUCs were generated to visually depict the ability of the AD8 to discriminate between normal and very mild pre-existing dementia (CDR score ≥0.5) and between normal and mild pre-existing dementia (CDR score ≥1).

Results

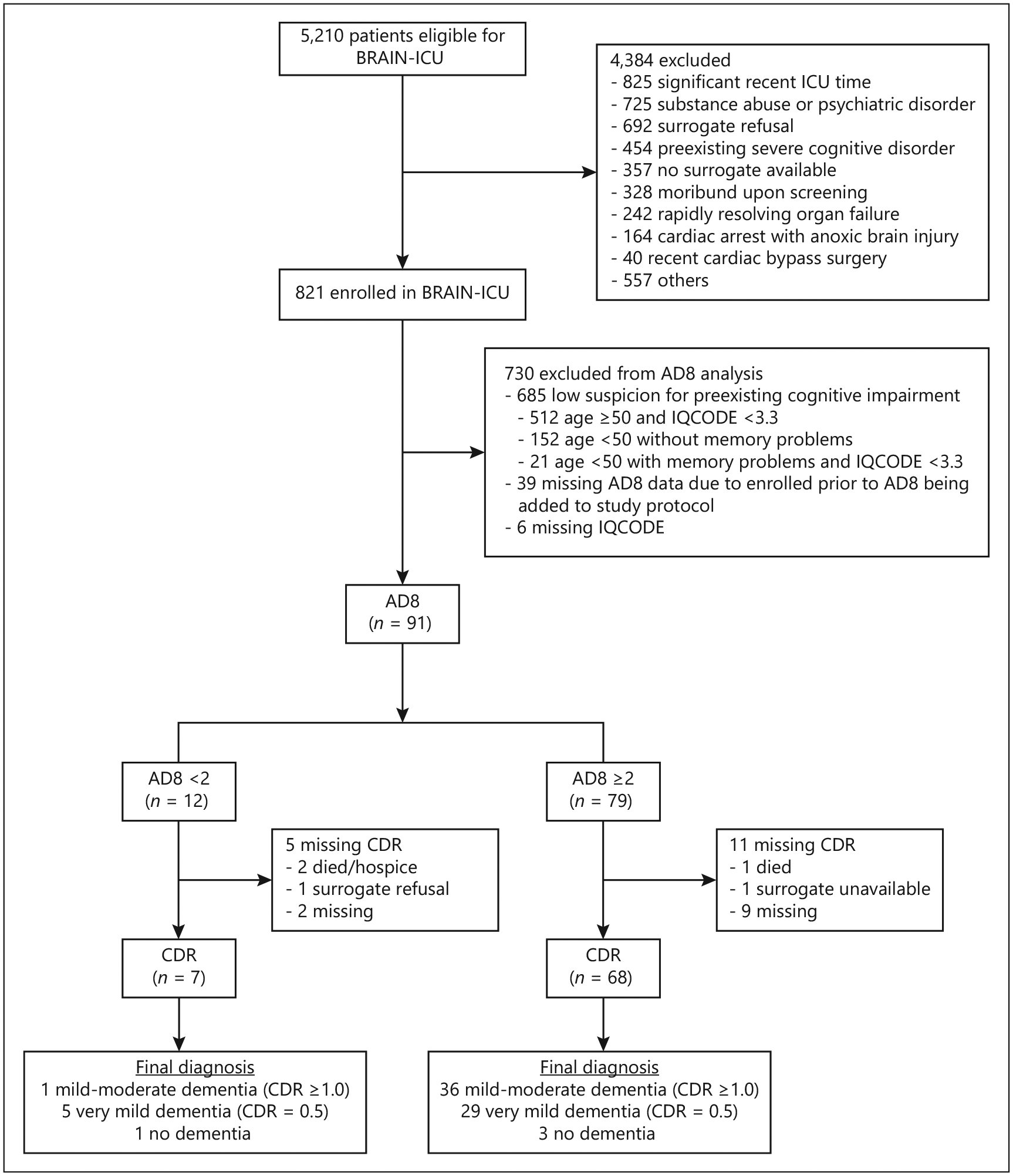

Among 821 patients enrolled in BRAIN-ICU, 91 had the AD8 completed (Fig. 2). Of those, 16 (18%) were missing a CDR score (5 [42%] of those with an AD8 score <2 and 11 [14%] of those with an AD8 score ≥2). A total of 75 patients for whom the AD8 was completed had a CDR score <3 and were included as the final study population (Table 1). Surrogates were mostly spouses (n = 33; 44%) or adult children (n = 29; 39%). Four patients had the capacity to answer questions and contributed to the CDR responses, but only one of these did not have a surrogate also answering the questionnaires.

Fig. 2.

Study enrollment. Seventy-five patients had the Eight-Item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia (AD8; index test) and the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR; reference standard) completed and were included in this study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants (n = 75)

| Demographics | |

| Age, years | 61.5 (53.0–76.6) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| White | 72 (96) |

| Black | 3 (4) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 32 (43) |

| Married, n (%)a | 24 (32) |

| Employed at ICU admission, n (%) | 3 (4) |

| Years of education | 12 (11–12) |

| Baseline clinical status | |

| FAQ score | 8 (2–13) |

| FAQ score >9, n (%)b | 34 (45) |

| Katz ADL scoreb | 1 (0–3) |

| Frailty, n (%)c | 45 (60) |

| History of depression, n (%) | 38 (51) |

| History of non-depression psychiatric illness, n (%) | 18 (24) |

| Charlson comorbidity indexd | 2 (1–4) |

| Framingham Risk Score | 9 (6–15) |

| In-hospital characteristics | |

| Admission diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Sepsis, ARDS due to infection or septic shock | 24 (32) |

| CHF/cardiogenic shock | 7 (9) |

| Airway protection | 7 (9) |

| COPD/asthma or ARDS without infection | 5 (7) |

| Surgery | 18 (24) |

| Other medical diagnosis | 14 (19) |

| ICU type, n (%) | |

| Medical | 45 (60) |

| Surgical | 30 (40) |

| Modified SOFA score at enrollmente | 6 (5–8) |

| Patients with mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 66 (88) |

| Patients with delirium, n (%) | 55 (73) |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 24 (32) |

Values denote the median (IQR) or n (%). ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Marital status was assessed at the 3-month follow-up.

Disability was defined as dependency in either activities of daily living (ADL), determined by the Katz ADL score, or instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), determined by the Pfeffer Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) score.

Frailty was defined as a score of 5 or higher on the Clinical Frailty Scale.

Scores on the Charlson comorbidity index range from 0 to 33 (higher is worse).

Scores on the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) range from 0 to 24 (higher is worse).

Table 2 shows the classification of the patients by AD8 and CDR. Table 3 lists the diagnostic performance of the AD8 for each CDR reference standard (0.5 and 1). The receiver operating characteristic curves are depicted in Figure 3.

Table 2.

Classification of the patients by CDR diagnosis (n = 75)

| Test result | CDR diagnosis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| normal (CDR score = 0) | very mild dementia (CDR score = 0.5) | mild dementia (CDR score = 1.0) | moderate dementia (CDR score = 2.0) | |

| Not impaired (AD8 score <2) | 1 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Impaired (AD8 score ≥2) | 3 | 29 | 27 | 9 |

CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale; AD8, Ascertain Dementia 8.

Table 3.

Psychometric properties of the AD8 among critically ill adults using the CDR as the reference standard

| CDR score ≥0.5 as reference standard | CDR score ≥1 as reference standard | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (95% CI), % | 91.55 (82.51–96.83) | 97.30 (85.84–99.93) |

| Specificity (95% CI), % | 25.00 (0.63–80.59) | 15.79 (6.02–31.25) |

| Accuracy, % | 88 | 57 |

| PPV (95% CI), % | 95.59 (87.64–99.01) | 52.94 (40.45–65.17) |

| NPV (95% CI), % | 14.29 (0.00–57.87) | 85.71 (42.13–99.64) |

| Positive LR (95% CI) | 1.22 (0.69–2.16) | 1.15 (1.00–1.34) |

| Negative LR (95% CI) | 0.34 (0.05–2.18) | 0.17 (0.02–1.35) |

| AUC (95% CI) | 0.734 (0.538–0.930) | 0.738 (0.626–0.850) |

CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale; AD8, Ascertain Dementia 8; AUC, area under the curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; LR, likelihood ratio.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for the Eight-Item Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia (AD8) as a screening tool for diagnosing dementia. Receiver operating characteristic curves are shown using the standard cutoff of ≥2 for the AD8. a Diagnostic performance of the AD8 for diagnosing very mild dementia (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score ≥0.5). b Diagnostic performance of the AD8 for diagnosing mild dementia (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale score ≥1.0).

Discussion

This study is the first to evaluate the diagnostic performance of the AD8 in detecting pre-existing dementia among critically ill adults suspected of having pre-existing dementia. In this sample, the AD8 – despite being very brief – was found to have high sensitivity (97%) for detecting mild pre-existing dementia (CDR ≥1.0) and a high negative predictive value (86%). Its low specificity in this population does warrant more detailed testing to confirm a diagnosis of dementia.

Our results are largely consistent with prior validation studies of the AD8 [14] and add to the small body of research examining pre-existing dementia screening tools in the ICU setting. Pisani et al. [1] found that 86% of the time the IQCODE agreed with the Modified Blessed Dementia Rating Scale, though the diagnostic accuracy of the IQCODE was not studied. The AD8 (2- to 3-min tool) is quicker to administer than the IQCODE (10–25 min), and the CDR is more of a gold standard than the Modified Blessed Dementia Rating Scale.

Identifying pre-existing dementia with the AD8 as a high-sensitivity test has potential to improve the clinical care of patients and to facilitate research. Pre-existing dementia increases the risk for delirium [2], worsening cognitive impairment [6, 28, 29], and for a composite outcome of readmission or death [30]. This quick tool could allow clinicians to identify this at-risk population, institute preventive efforts in the ICU, and ensure safe discharge plans after hospitalization. Additionally, screening for pre-existing dementia is important for research purposes. First, identifying patients with pre-existing dementia would allow researchers to study the effect of pre-existing dementia on important clinical outcomes. Second, screening for pre-existing dementia in the ICU with a brief tool is particularly important to distinguish it from incident long-term cognitive impairment, which newly develops in up to a third of ICU survivors [6].

Our study has potential limitations. First, external validity is threatened because our sample represents a very select group of critically ill patients at risk for dementia (75 of 821 participants) and may not represent the ICU population at large. Our sample had a high prevalence of dementia in part because we administered the CDR to those deemed to be at higher risk. This was a decision based on resource limitations in administering the lengthy CDR. In a broader population with lower dementia prevalence, the positive predictive value would be lower than we determined. Second is the potential for verification bias. Because this analysis was within the context of a prospective cohort with a protocol for screening for pre-existing dementia, only patients in whom pre-existing dementia was suspected (IQCODE score ≥3.3) received the CDR due to resource limitations. Verification bias would overestimate sensitivity and underestimate specificity. Despite the potential for verification bias, our study findings are still useful, especially in the medium-risk group, in which diagnosing dementia can be the most difficult. Third, the differential rate of CDR completion introduces the possibility that the results of the AD8 potentially influenced whether the CDR was completed. It is possible that upon scoring a reassuringly low AD8 score, research personnel were less likely to encourage the surrogate to complete the lengthy CDR.

In summary, among critically ill patients judged at medium risk for pre-existing dementia, the 2- to 3-min AD8 is highly sensitive (97%) and has a high negative predictive value (86%). The AD8 may have great utility in efficiently ruling out dementia when employed in ICU contexts. Future studies should explore the psychometric properties of the AD8 in a broader population of ICU patients and survivors.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, BRAIN-ICU ClinicalTrials.gov No. NCT00392795).

Footnotes

Statement of Ethics

Written, informed consent was obtained from the patients or their authorized surrogates.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pisani MA, Inouye SK, McNicoll L, Redlich CA. Screening for preexisting cognitive impairment in older intensive care unit patients: use of proxy assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003. May;51(5):689–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morandi A, Davis D, Fick DM, Turco R, Boustani M, Lucchi E, et al. Delirium superimposed on dementia strongly predicts worse outcomes in older rehabilitation inpatients. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014. May;15(5): 349–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisani MA, Redlich C, McNicoll L, Ely EW, Inouye SK. Underrecognition of preexisting cognitive impairment by physicians in older ICU patients. Chest. 2003. Dec;124(6):2267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cherbuin N, Jorm AF. The IQCODE: using informant reports to assess cognitive change in the clinic and in older individuals living in the community. In: Larner AJ, editor. Cognitive screening instruments. London: Springer; 2013. pp. 165–82. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razavi M, Tolea MI, Margrett J, Martin P, Oakland A, Tscholl DW, et al. Comparison of 2 informant questionnaire screening tools for dementia and mild cognitive impairment: AD8 and IQCODE. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014. Apr–Jun;28(2):156–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Jackson JC, Morandi A, Thompson JL, Pun BT, et al. ; BRAIN-ICU Study Investigators. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013. Oct;369(14):1306–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.AD8 Dementia Screening Interview. Washington University School of Medicine., Knight ADRC. Available from: http://knightadrc.wustl.edu/About_Us/PDFs/AD8form2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Powlishta KK, Coats MA, Muich SJ, Grant E, et al. The AD8: a brief informant interview to detect dementia. Neurology. 2005. Aug;65(4):559–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galvin JE, Roe CM, Xiong C, Morris JC. Validity and reliability of the AD8 informant interview in dementia. Neurology. 2006. Dec;67(11):1942–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryu HJ, Kim HJ, Han SH. Validity and reliability of the Korean version of the AD8 informant interview (K-AD8) in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009. Oct–Dec;23(4):371–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tew CW, Ng TP, Cheong CY, Yap P. A Brief Dementia Test with Subjective and Objective Measures. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord Extra. 2015. Sep;5(3):341–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larner AJ. AD8 Informant Questionnaire for Cognitive Impairment: Pragmatic Diagnostic Test Accuracy Study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2015. Sep;28(3):198–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter CR, DesPain B, Keeling TN, Shah M, Rothenberger M. The Six-Item Screener and AD8 for the detection of cognitive impairment in geriatric emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2011. Jun; 57(6):653–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jackson TA, MacLullich AM, Gladman JR, Lord JM, Sheehan B. Diagnostic test accuracy of informant-based tools to diagnose dementia in older hospital patients with delirium: a prospective cohort study. Age Ageing. 2016. Jul;45(4):505–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berg L Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):637–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke WJ, Miller JP, Rubin EH, Morris JC, Coben LA, Duchek J, et al. Reliability of the Washington University Clinical Dementia Rating. Arch Neurol. 1988. Jan;45(1):31–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris JC, McKeel DW Jr, Fulling K, Torack RM, Berg L. Validation of clinical diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1988. Jul;24(1): 17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berg L, McKeel DW Jr, Miller JP, Storandt M, Rubin EH, Morris JC, et al. Clinicopathologic studies in cognitively healthy aging and Alzheimer’s disease: relation of histologic markers to dementia severity, age, sex, and apolipoprotein E genotype. Arch Neurol. 1998. Mar;55(3):326–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993. Nov; 43(11):2412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, McKeel DW, Price JL, Rubin EH, et al. Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2001. Mar;58(3):397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petersen RC, Doody R, Kurz A, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rabins PV, et al. Current concepts in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol. 2001. Dec;58(12):1985–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolf C, Slavin MJ, Draper B, Thomassen F, Kochan NA, Reppermund S, et al. Can the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Identify Mild Cognitive Impairment and Predict Cognitive and Functional Decline? Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2016;41(5–6):292–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitnitski AB, Mogilner AJ, Rockwood K. Accumulation of deficits as a proxy measure of aging. ScientificWorld-Journal. 2001. Aug;1:323–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychological function. JAMA. 1963. Sep;185(12):914–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CH Jr, Chance JM, Filos S. Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the community. J Gerontol. 1982. May;37(3):323–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, Melot C, Vincent JL. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2001. Oct;286(14):1754–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010. Jul; 304(4):443–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krogseth M, Wyller TB, Engedal K, Juliebø V. Delirium is an important predictor of incident dementia among elderly hip fracture patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2011;31(1):63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Briggs R, Dyer A, Nabeel S, Collins R, Doherty J, Coughlan T, et al. Dementia in the acute hospital: the prevalence and clinical outcomes of acutely unwell patients with dementia. QJM. 2017. Jan;110(1):33–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jorm AF. The Informant Questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): a review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2004. Sep;16(3):275–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]