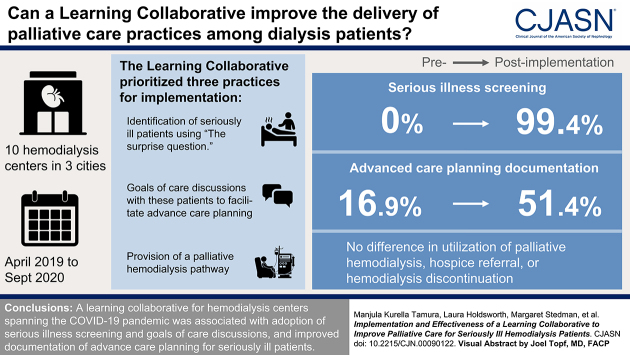

Visual Abstract

Keywords: geriatric nephrology, renal dialysis

Abstract

Background and objectives

Limited implementation of palliative care practices in hemodialysis may contribute to end-of-life care that is intensive and not patient centered. We determined whether a learning collaborative for hemodialysis center providers improved delivery of palliative care best practices.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Ten US hemodialysis centers participated in a pre-post study targeting seriously ill patients between April 2019 and September 2020. Three practices were prioritized: screening for serious illness, goals of care discussions, and use of a palliative dialysis care pathway. The collaborative educational bundle consisted of learning sessions, communication skills training, and implementation support. The primary outcome was change in the probability of complete advance care planning documentation among seriously ill patients. Health care utilization was a secondary outcome, and implementation outcomes of acceptability, adoption, feasibility, and penetration were assessed using mixed methods.

Results

One center dropped out due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Among the remaining nine centers, 20% (273 of 1395) of patients were identified as seriously ill preimplementation, and 16% (203 of 1254) were identified as seriously ill postimplementation. From the preimplementation to postimplementation period, the adjusted probability of complete advance care planning documentation among seriously ill patients increased by 34.5 percentage points (95% confidence interval, 4.4 to 68.5). There was no difference in mortality or in utilization of palliative hemodialysis, hospice referral, or hemodialysis discontinuation. Screening for serious illness was widely adopted, and goals of care discussions were adopted with incomplete integration. There was limited adoption of a palliative dialysis care pathway.

Conclusions

A learning collaborative for hemodialysis centers spanning the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic was associated with adoption of serious illness screening and goals of care discussions as well as improved documentation of advance care planning for seriously ill patients.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number:

Pathways Project: Kidney Supportive Care, NCT04125537

Introduction

High-quality care for patients with serious illness incorporates palliative care practices that enable patients to plan for their care and prepare for end of life (1,2). Hemodialysis providers poorly grasp their patients’ health priorities and fail to recognize when patients prioritize treatment of symptoms or relief of suffering over life extension (3). Prevailing hemodialysis models do not routinely incorporate palliative care practices, such as talking with patients about their prognosis and goals of care, facilitating advance care planning, and offering pathways for patients who want to limit aggressive care (4,5). These shortcomings contribute to high-intensity end-of-life care that may not be beneficial or patient centered (6,7).

Recognizing the limited number of palliative care specialists, implementation of primary palliative care has been recommended in settings that care for seriously ill patients (8,9). Hemodialysis centers are a logical site for this care because their providers have preexisting relationships and regular interaction with patients, and they are uniquely qualified to address the role of dialysis treatment during goals of care discussions. However, there has been limited success in routinely implementing palliative care services for many serious illnesses, including kidney failure (10,11). Passive dissemination of best practices and reliance on individual provider continuing education are rarely sufficient to overcome multilevel barriers. Furthermore, little is known about how to scale and sustain palliative care practices across diverse health systems because most interventions for the hemodialysis population have been tested in controlled research protocols or in a single-center setting (12–19).

The Pathways Project is a learning collaborative on the basis of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement model, in which teams from learning health care systems are brought together to apply improvement principles in a focused practice area: in this case, to improve delivery of palliative care best practices in hemodialysis centers (20,21). We assessed whether the learning collaborative fostered implementation of palliative care best practices in hemodialysis centers and whether it improved documentation of advance care planning and reduced acute health care utilization. The study spanned the early phase of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (coronavirus disease 2019 [COVID-19]) pandemic (22), providing a window into the experience of delivering palliative care during this period of heightened strain on health care systems.

Materials and Methods

Design, Setting, and Participants

Between April 1, 2019 and September 30, 2020, we conducted a mixed methods hybrid implementation-effectiveness study to evaluate a palliative care learning collaborative for providers from outpatient hemodialysis centers. The protocol was registered and approved by the institutional review board at George Washington University (180679). We followed the STROBE and SRQR standards in conducting the study and reporting the findings.

Ten hemodialysis centers in the New York City, Denver, and Dallas metropolitan areas took part in the study. Participating centers represented two for-profit dialysis organizations, one not-for-profit dialysis organization, and their affiliated nephrology practices. Typical of most hemodialysis centers, care was directed by nephrologists in concert with a multidisciplinary team. At the outset of the collaborative, most centers were conducting routine patient care conferences. Goals of care discussions and advance care planning were left to the discretion of individual treating nephrologists. Two centers offered palliative hemodialysis, and none had protocols addressing hospice referrals or discontinuation of hemodialysis.

Intervention

A detailed description of the intervention development and collaborative structure has been published (23). Briefly, the Pathways Project identified a “change package” consisting of 14 evidence-based best practices in palliative care, also known as kidney supportive care, and prioritized three practices for implementation: (1) identification of seriously ill patients; (2) goals of care discussions with these patients to facilitate advance care planning for future care options; and (3) provision of palliative hemodialysis defined as hemodialysis frequency less than thrice weekly to meet patient goals, coordination of care transitions with palliative care and hospice, and hemodialysis discontinuation for appropriate patients, hereafter referred to collectively as the palliative dialysis care pathway (24,25). At monthly intervals, providers screened adult patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis treatment with the surprise question (“Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 6–12 months?”) to identify seriously ill patients and prioritize them for supportive care practices (26). Identification of seriously ill patients in the first month of each implementation period was a required component of the evaluation. Centers had flexibility in the implementation of other components of the change package to allow for tailoring to local context and organizational needs.

Implementation teams consisting of a nephrologist or advanced practice provider and two to four additional multidisciplinary team members from each center participated in the collaborative. The curriculum covered the change package best practices, serious illness communication skills, and quality improvement methods. The collaborative structure included three learning sessions, monthly action calls, monthly support from a quality improvement expert, and ad hoc mentorship from a nephrologist dually board certified in palliative medicine (AHM). A detailed description of the learning session objectives and activities is presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Communication skills training was on the basis of the Veterans Affairs Goals of Conversation training program and VitalTALK curriculum (27,28). Participants learned skills for responding to emotion, checking for understanding, and eliciting goals, followed by role play to practice skills. Motivational interviewing skills were practiced in the second learning session (29). Re-education needs were met in four ways: role modeling of goals of care discussions by a palliative care nephrologist with center patients; an Ask-Tell-Ask laminated pocket card to use as a prompt during discussions; a video demonstrating a goals of care discussion with a standardized patient; and debriefing during action calls. The quality improvement component of the curriculum covered plan-do-study-act cycles, small tests of change, and root cause analysis (30). The first two learning sessions were in person over 2 days each in April and October 2019, and the third was virtual in three 2-hour sessions in July 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. To monitor implementation, each center collected data on two process measures—the percentage of patients screened for serious illness and the percentage of seriously ill patients with a goals of care discussion within 30 days of hospital discharge—as a proxy for center-wide adoption of this practice. Monthly action calls utilized the “all teach, all learn” model, which includes feedback on center performance, reinforcement of communication skills, and a forum for teams to share successes and exchange strategies for overcoming obstacles (20). Supplemental Figure 1 illustrates the timeline of the intervention delivery and data collection.

Effectiveness Outcomes

Using a pre-post design, effectiveness outcomes were compared in patients who screened positive as seriously ill in month 1 (the preimplementation period) and study month 15 (the postimplementation period). Two coprimary outcomes were designated—complete advance care planning documentation and patient-reported quality of end-of-life communication. Quality of end-of-life communication was dropped due to completion rates below 30%. Chart audits to measure advance care planning documentation were conducted by staff members at each center. Trained auditors used a checklist to ascertain the presence and quality of documentation for each of the following elements: designated surrogate decision maker; narrative discussion of goals of care; an accessible advance directive; and a medical order, such as do not resuscitate (DNR), physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST), or medical orders for life-sustaining treatment. Complete advance care planning documentation required three elements: a surrogate, a goals of care discussion, and either an accessible advance directive or medical order.

Seriously ill patients in month 1 and month 15 were followed from the start of each evaluation period for 3 months to ascertain mortality and palliative care utilization, including hospice referral, hemodialysis discontinuation, and the provision of palliative hemodialysis.

Statistical Analyses

One center dropped out due to the COVID-19 pandemic and could not be included in the analysis. We used descriptive statistics to plot the monthly rate of serious illness screening, screen-positive rates, and goals of care discussions over the duration of the study. To test for differences in advance care planning and utilization outcomes between the pre- and postimplementation periods, we applied a generalized linear mixed effect model with the logit link with random effects for the center and patient nested within the center. We obtained the population-averaged predicted probabilities for each outcome in the pre- and postimplementation periods from the generalized linear mixed effect model using the adjusted fixed effects (31). To estimate the adjusted period effect, we subtracted the predicted probability for the preimplementation period from the predicted probability for the postimplementation period. Estimates were bootstrapped using a clustered sampling method (with resampling at the site and patient levels) to obtain the bootstrapped confidence intervals (Supplemental Material). In sensitivity analyses, we additionally adjusted for patient age, sex, race, and ethnicity. We also conducted a subgroup analysis limited to the 77 patients who were present in both cohorts. Advance care planning and utilization outcomes were analyzed as dichotomous or categorical variables. Mortality was analyzed as an incidence rate. All analyses were performed using SAS Windows, version 9.4.

Implementation Assessment

The implementation assessment evaluated the appropriateness, adoption, feasibility, and penetration of the intervention (32). One researcher (L.H.) observed all learning sessions and action calls to follow collaborative activities and progress within each center over time. Notes from observations were organized into a narrative immediately following each session and treated like interview transcripts for analysis. Four centers representing variation in dialysis organization, geographic region, and implementation team configuration were selected for in-depth interviews at the end of the implementation period (32,33). Fourteen semistructured interviews with implementers from four centers were conducted between August and September 2020, with three to five participants selected from each center. The interview topic guide is presented in Supplemental Table 2. Professional groups included four nephrologists, two advanced practice providers, four social workers, and four nurses. Interviews lasted between 23 and 65 minutes (median =52 minutes).

Summaries of interviews and center-specific themes were circulated back to participants to check understanding and interpretation (34). All interviews were conducted via teleconference, recorded with permission, and transcribed for analysis. Transcripts were uploaded into NVivo (released March 2020) for coding and analysis. Analysis used deductive and inductive approaches, utilizing a priori codes from the topic guide and implementation theory while searching for emergent themes (34).

Data from quantitative and qualitative methods were integrated at the interpretation stage of analysis, and implementation of each practice was assessed as high, mixed, limited, or none. To evaluate center variation in advance care planning outcomes, we categorized centers into high and low performers on the basis of the primary outcome: the percentage of patients with complete advance care planning documentation above the median (≥40% versus <40%). Drawing on observations of all centers and interviews with two high-performing centers and two low-performing centers, we used a matrix analysis to look for patterns in practices, barriers, and facilitators between high- and low-performing centers.

Results

Study Population

Nine centers collected outcomes data in the pre- and postimplementation periods (Supplemental Figure 2). The total census was 1395 patients (median =132) during the preimplementation period and 1254 patients (median =133) during the postimplementation period. Of these patients, 273 (20%) in the preimplementation period and 203 (16%) in the postimplementation period were identified as seriously ill. Seriously ill patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The distribution of men, Hispanic ethnicity, Medicaid insured, and years receiving dialysis was similar in both periods. Compared with the preimplementation cohort, the postimplementation cohort was older and more likely to be non–English speaking. Center distribution also varied between periods.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients receiving hemodialysis who screened positive as seriously ill in the pre- and postimplementation periods

| Characteristic | N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Preimplementation, n=273 | Postimplementation, n=203 | |

| Age range, yr, n (%) | ||

| <55 | 39 (14) | 25 (12) |

| 55–64 | 69 (25) | 31 (15) |

| 65–74 | 81 (30) | 63 (31) |

| 75–84 | 51 (19) | 56 (28) |

| ≥85 | 33 (12) | 28 (14) |

| Men, n (%) | 158 (58) | 121 (60) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 161 (59) | 116 (57) |

| Black | 66 (24) | 47 (23) |

| Other | 46 (17) | 40 (20) |

| Hispanic ethnicity, n (%) | 85 (31) | 59 (29) |

| Primary language, n (%) | ||

| English | 220 (81) | 139 (71) |

| Spanish | 35 (13) | 28 (14) |

| Other | 17 (6) | 29 (15) |

| Medicaid insurance, n (%) | 174 (64) | 128 (63) |

| On dialysis, yr | ||

| <1 | 46 (17) | 31 (15) |

| 1–2 | 81 (30) | 55 (27) |

| 3+ | 146 (54) | 117 (58) |

| Center, n (%) | ||

| 1 | 16 (6) | 10 (5) |

| 2 | 24 (9) | 15 (7) |

| 3 | 28 (10) | 20 (10) |

| 4 | 17 (6) | 19 (9) |

| 5 | 43 (16) | 33 (16) |

| 6 | 29 (11) | 45 (22) |

| 7 | 34 (13) | 27 (13) |

| 8 | 28 (10) | 14 (7) |

| 9 | 54 (20) | 20 (10) |

Eight were missing primary language.

Adoption of Screening for Serious Illness, Goals of Care Discussions, and Palliative Dialysis Care Pathways

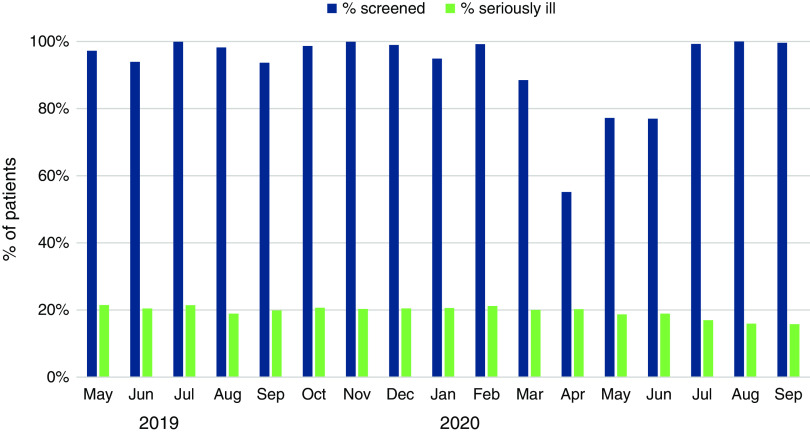

The average serious illness screening rate exceeded 90% for the first 10 months, dropped to a nadir of 55% during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic due to cessation of screening at four centers, and rebounded to >90% by July 2020 (Figure 1). Screen-positive rates varied by center from 9% to 31%, whereas the average screen-positive rate was stable throughout most of the implementation period. The center-reported occurrence of goals of care discussions after hospital discharge, a proxy for center-wide adoption, varied over the implementation period, with no clear temporal trend. From the preimplementation to postimplementation period, the number of centers offering a palliative dialysis care pathway increased from two to five. Several established referral relationships with local hospice organizations, and no centers implemented a protocol for hemodialysis discontinuation.

Figure 1.

Monthly rate of screening for serious illness and screen-positive rate among nine hemodialysis centers participating in a palliative care learning collaborative.

Advance Care Planning Documentation and Palliative Care Utilization

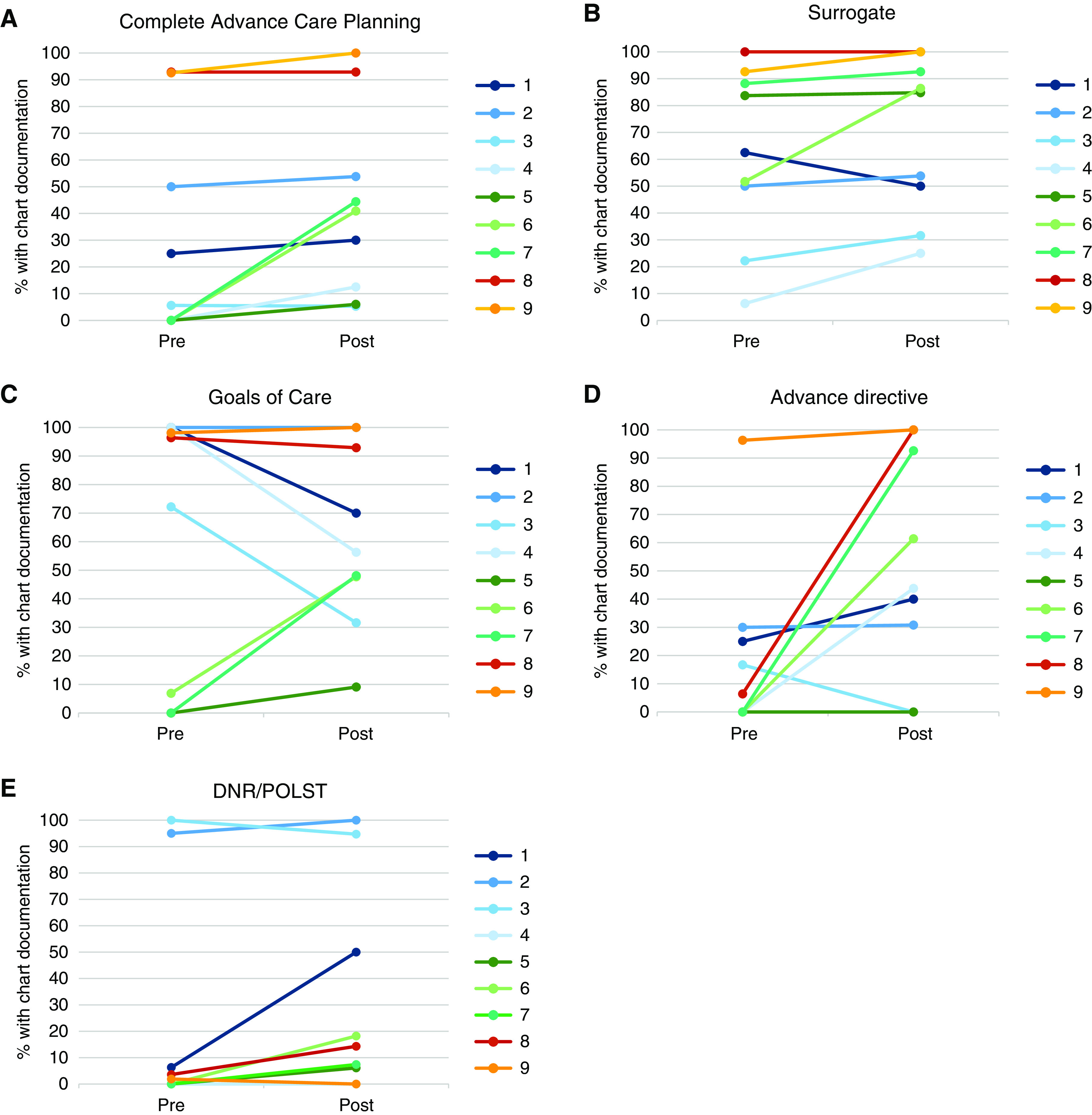

In adjusted models, the predicted probability of complete documentation of advance care planning increased by 34.5 percentage points from the preintervention period to the postintervention period (95% confidence interval, 4.4% to 68.5%) (Table 2). There was a significant increase in the predicted probability of documentation of an advance directive and a DNR/POLST (Table 2). There was no significant difference in the predicted probability of documentation of a surrogate or a goals of care discussion between intervention periods. Changes in documentation of each advance care planning element by center are illustrated in Figure 2. From the preimplementation to postimplementation period, surrogate and advance directive documentation increased at seven of nine centers, and DNR/POLST documentation increased at six centers. Regression to the mean was observed for goals of care documentation, such that documentation increased at centers with low preimplementation performance and decreased at centers with high preimplementation performance.

Table 2.

Adjusted probability of advance care planning documentation in hemodialysis medical record, palliative care utilization, and mortality rate among seriously ill patients in the pre- and postimplementation periods

| Implementation Outcomes | Preimplementation Predicted Probability | Postimplementation Predicted Probability | Difference in Predicted Probability (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advance care planning element | |||

| n | 258 | 196 | |

| Complete advance care planning, % | 16.9 | 51.4 | 34.5 (4.4 to 68.5) |

| Surrogate, % | 68.6 | 80.9 | 12.3 (–2.7 to 30.6) |

| Goals of care, % | 70.6 | 80.4 | 9.8 (–23.9 to 52.6) |

| Advance directive, % | 14.8 | 67.7 | 52.9 (2.2 to 92.2) |

| Do not resuscitate or POLST, % | 6.1 | 35.4 | 29.3 (3.5 to 61.8) |

| Palliative care utilization | |||

| n | 273 | 203 | |

| Palliative dialysis, % | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.8 (–1.7 to 4.6) |

| Referred to hospice, % | 2.6 | 1.5 | −1.1 (–4.6 to 3.7) |

| Discontinued dialysis, % | 2.2 | 0.5 | −1.7 (–4.1 to 1.8) |

| Mortality rate | |||

| n | 273 | 203 | |

| Death per 100 person-mo (95% CI) | 2.5 (1.6 to 4.0) | 2.0 (1.1 to 3.6) | −0.5 (–2.9 to 2.2) |

Seriously ill patients were identified by a response of “No, I would not be surprised” to the surprise question “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next 6–12 months?” Complete advance care planning indicates documentation of three elements: a surrogate, a goals of care discussion, and either an accessible advance directive or a medical order. One patient was missing a goals of care assessment, and one patient was missing an advance directive assessment. Adjusted estimates are from generalized linear mixed effects models with patient and center included as random effects. Predicted probabilities are averaged over site and patient and estimated as . The 95% CIs for the difference in predicted probability were estimated by clustered bootstrap. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; POLST, physician orders for life-sustaining treatment.

Figure 2.

Documentation of complete advance care planning among seriously ill patients during the pre- and postimplementation periods by center. Complete advance care planning (A), a surrogate (B), goals of care discussion (C), advance directive (D), and do not resuscitate (DNR)/physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (POLST) order (E).

In adjusted models, there was no significant difference in mortality or in the predicted probability of palliative hemodialysis, hospice referral, or hemodialysis discontinuation between the preintervention and postintervention periods (Table 2).

In sensitivity analyses, the estimated mean period effect on advance care planning documentation and utilization outcomes was similar after adjustment for patient demographic characteristics (Supplemental Table 3). The findings were similar when the analysis was limited to the 77 patients who were present in both periods (Supplemental Table 4).

Implementation of Palliative Care Best Practices

Table 3 lists the overall implementation assessment for the three best practices, with quotes highlighting themes regarding the appropriateness, adoption, feasibility, and penetration of each practice. The high rate of adoption for the first best practice, identifying seriously ill patients, was corroborated by interviews with participants, who perceived that the practice was useful for prioritizing patients for goals of care discussions, intuitive to apply, and easy to incorporate into workflow and spread to other providers. Although all centers adopted the second best practice to some degree, there were mixed experiences with implementation. Interviews suggested that providers needed time to gain self-efficacy in conducting goals of care discussions and overcome perceived feasibility barriers, such as coordinating schedules for family meetings. Limited adoption and penetration of the third best practice, offering a palliative dialysis care pathway, reflected mixed perceptions of appropriateness and the low feasibility of hospice care at several centers.

Table 3.

Implementation outcomes of a palliative care learning collaborative for hemodialysis centers

| Implementation Outcome | Overall Assessment | Summary of Findings and Exemplar Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Practice 1: Identifying seriously ill patients | ||

| Appropriateness | High | Implementation teams viewed this as an appropriate practice because it was useful for prioritizing patients for goals of care discussions “You don't sit down with the calculator and think about it, you just say ‘No, I won't be surprised’ or ‘Yes, I would be surprised.’ And amazingly accurate that is, and prompting us then to have the conversation that those patients are actually probably hoping that we'll have with them” (interview 2, nephrologist) |

| Adoption | High | Implementation team reports, corroborated by quantitative data, indicated that adoption of this practice was rapid and widespread “It doesn't take long to just go down the list and check to see. And most of the time, the patients, they stay the same” (interview 13, nurse practitioner) |

| Feasibility | High | Implementation teams reported that this practice was easily integrated into existing workflows “[Using the surprise question] is a breeze. That's like a slam dunk because what happens is [the social worker] has a list of patients per shift, and before we do our rounds, which is every single week, if it's that week, then she'll hand me the list of patients” (interview 4, nephrologist) |

| Penetration | High | Interviews indicated that providers outside the implementation team participated in identifying seriously ill patients “The first week of the month, [the coordinator] sends out an email to all of the nephrologists who have in-center dialysis patients with their census and a spreadsheet to check off yes or no to the surprise question, which we then send back to her. We've asked each physician to be the point person for their patients and answering that question” (interview 10, nephrologist) |

| Practice 2: Conducting goals of care discussions | ||

| Appropriateness | High | Interviews indicated that participating providers believed in this practice and were conceptually willing to engage in goals of care discussions; perceptions of appropriateness were often shaped by previous personal or clinical experiences “Patients want to have this conversation, they need to have this conversation, but they're going to offer resistance, and that resistance has to be gently and politely, but persistently overcome” (interview 11, nephrologist) |

| Adoption | High | Interviews indicated that providers needed time to achieve proficiency in communication skills before gaining self-efficacy in this practice; this occurred more rapidly at some centers than others due to prior exposure to communication skills training and greater engagement in collaborative activities “Initially we were using the little cards that they have provided us, to help us guide us through the conversation, but now I think it's just easier to just talk to the patient” (interview 7, nurse) |

| Feasibility | Mixed | Implementation teams reported that feasibility was affected by scheduling challenges that were accentuated during the COVID-19 pandemic and competing clinical demands “In private practice, we're trying to jam as much in to a week as we can without going crazy. And so putting in one more thing (goals of care conversations) that's uncomfortable and stretches you in a new direction is not your first instinct” (interview 4, nephrologist) |

| Penetration | Mixed | Interviews indicated uneven spread to providers outside the implementation team “We struggle still with [our other doctor] having these conversations and that always seems to be the topic of those monthly meetings. But now we have [a new nurse practitioner] and we're able to use her” (interview 3, nurse) |

| Practice 3: Offering a palliative dialysis care pathway | ||

| Appropriateness | Mixed | Implementation teams reported that views of the appropriateness of this practice were influenced by perceived patient preferences and perception by colleagues that palliative dialysis equated with inadequate care; there was some indication of changing views over the course of the collaborative on the appropriateness of this practice, as implementers internalized serious illness models of care “Every patient that I've done a goals of care conversation with has told me, ‘I will be on dialysis until the very day that I die’” (interview 6, nurse practitioner) “It's definitely in the front of my mind now, which is good. I'd be probably seeking out those people who are suffering. Saying okay, well their fluid gains are small but potassium's controlled, we can do this as they transition to end of life” (interview 2, nephrologist) |

| Adoption | Limited | Implementation teams reported limited adoption due to concerns about appropriateness and effect on dialysis quality measures “[The nephrologist] was very, very reluctant. I remember because his biggest thing was because it affects so much our Kt/v rates …. I remember, him saying that you know they need to change the guidelines to decrease that if you have someone who's on palliative dialysis. However, the patient we do have on palliative dialysis now, she used to be three days a week, three and a half hours and he moved her to four hours, but two days a week, but her lab values have not changed at all” (interview 3, nurse) |

| Feasibility | Limited | Palliative dialysis was feasible to implement for selected patients but not in a systematic way due to perceived lack of leadership buy-in and financial barriers to hospice; in several areas, hospices were unwilling to accept patients who wanted to continue dialysis, despite the presence of a terminal diagnosis other than kidney failure “We've got a couple of patients that are unofficially dialyzed in a quasipalliative way that are getting less dialysis by the book than other patients. But that is not something that we've standardized and worked out within the practice. And I feel a little uncomfortable about that because it looks like I've just gone rogue and done my own thing” (interview 4, nephrologist) |

| Penetration | None | There was limited evidence from interviews or observations that this practice spread outside the implementation team |

Appropriateness is the perceived fit or relevance of the practice. Adoption is the uptake of or intention to try the practice. Feasibility is the actual fit of the practice. Penetration is the spread of the practice to other providers within the center. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Four implementation themes characterized centers with high performance in complete advance care planning documentation from low-performing centers: (1) raising awareness of advance care planning, (2) making time for goals of care discussions, (3) creating standard work, and (4) leveraging multidisciplinary team roles (Table 4).

Table 4.

Implementation themes characterizing centers with high and low performance in complete advance care planning documentation

| Theme | Implementation Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performing Centers, n=5 | Low-Performing Centers, n=4 | |

| Raising awareness of advance care planning | High-performing centers used lobby daysa to educate patients, families, and staff about the purpose of advance care planning and prime them for a goals of care discussion | Low-performing centers had more limited efforts to educate patients about the purpose of advance care planning |

| Making time for goals of care discussions | High-performing centers integrated chairside goals of care discussions into team rounds, scheduled separate goals of care appointments with nephrologists or nurse practitioner/social worker teams using calendar blocks, and/or had greater provider availability on site to have impromptu conversations | Low-performing centers identified patients who would benefit from a goals of care discussion during patient care conferences, but lack of nephrologist availability contributed to lower success conducting discussions |

| Creating standard work | High-performing centers created standard work by adapting established programs for advance care planning, such as PREPARE or 5 Wishes, and incorporating advance care planning into routine work, such as the admissions process and unstable patient care conferences. They also developed and implemented advance care planning templates in the electronic health record. Standard work was reinforced by tracking performance in these processes at regular quality assurance and performance improvement meetings | Low-performing centers attempted to adapt established programs but approached advance care planning in a more “ad hoc” fashion They were more likely to perceive that these processes competed with other clinical demands, especially during COVID-19; consequently, the workflow did not become hardwired |

| Leveraging multidisciplinary team roles | High-performing centers effectively used nurses, social workers, and/or lay navigators to practice “at the top of their license” by empowering them to prime patients for a goals of care discussion or complete advance directives following a goals of care discussion | At low-performing centers, work was not distributed among the multidisciplinary team but rather revolved around the nephrologist who had limited time in the center as compared with other professional groups |

Complete advance care planning documentation required three elements: a surrogate, a goals of care discussion, and either an accessible advance directive or medical order. High-performing centers were defined as those that achieved complete advance care planning documentation ≥40% in the postimplementation period. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Lobby days are informal educational events about advance directives and advance care planning held in the lobby (i.e., waiting room) of dialysis centers.

Discussion

We conducted a multicenter study to assess the effects of a learning collaborative for hemodialysis providers on the delivery of palliative care best practices. Of the three practices prioritized for implementation, screening for serious illness was widely adopted and sustained during the pandemic. Goals of care discussions were adopted at all centers with incomplete integration. Over the 17-month learning collaborative, we observed an increase in complete documentation of advance care planning in the medical record for seriously ill patients. There was limited adoption of the third best practice, a palliative dialysis care pathway, and no significant difference in utilization of its components (palliative hemodialysis, hospice referral, or dialysis discontinuation) among seriously ill patients after the intervention.

Numerous studies have demonstrated gaps in the quality of serious illness care for patients receiving hemodialysis treatment, but few have assessed the implementation of palliative care practices across health systems or the effects on health care utilization. Our findings from nine hemodialysis centers with varied organizational structures and patient mix highlight both the potential benefits and several challenges associated with integrating palliative care practices for patients receiving hemodialysis treatment.

The simplicity and intuitiveness of the surprise question to screen for serious illness facilitated its uptake, and the continuation of this practice during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic supports the feasibility of its sustainment. The learning collaborative also seemed effective in overcoming barriers to increase documentation of advance care planning. The increase in complete advance care planning documentation, from 17% to 51%, is consistent with effects observed in controlled studies in which dedicated advance care planning facilitators were used (15,18,19). A consensus conference on advance care planning ranked documentation as a high-priority outcome (35), and the increases we observed in these outcomes are considered meaningful improvements in quality of care for seriously ill populations. Because access to specialty-trained palliative care providers or dedicated advance care planning facilitators may not be feasible in many dialysis settings, the collaborative relied on peer modeling to spread communication skills necessary to conduct goals of care discussions. Our observations suggested that centers that were more effective at implementation engaged patients, families, staff, and clinicians in a group of inter-related activities to generate momentum for the advance care planning process rather than relying on the nephrologist to drive the practice.

Utilization of palliative hemodialysis, hospice, and dialysis discontinuation did not change after the intervention. Interviews indicated a lack of buy-in among providers and leadership, poor alignment of this practice with dialysis performance measures, and barriers to hospice. The Medicare Hospice benefit permits patients to receive dialysis services under the ESRD benefit when the terminal diagnosis is not related to kidney failure; however, coverage determinations are delegated to local administrators (36,37). Participants reported that some hospice agencies were unwilling to admit patients who wanted to continue dialysis regardless of their terminal diagnosis. Limited implementation of this practice may also reflect an element of cognitive overload; the lift required on the part of dialysis centers to implement three new practices in a 17-month span during a global pandemic may have been too large.

This study has several limitations. First, pre-post designs are vulnerable to secular trends that can bias patient selection and outcomes. Although we attempted to account for differences in patient selection using regression methods, we could not account for the unanticipated effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and cannot exclude the possibility that the pandemic prompted more advance care planning. Geographic variation in the effect of COVID-19 may have affected the composition of the study cohort. If the pandemic resulted in death of patients who were less likely to engage in advance care planning, then the postimplementation probability of advance care planning documentation may be inflated. Second, we intended to measure patient-reported quality of communication but were limited by response rates below 30%. As a result, we cannot determine whether changes in advance care planning documentation were accompanied by improved patient understanding or experience. This information would be useful to assess the quality of communication skills training delivered by the collaborative. Third, chart auditors were not blinded to the intervention. Fourth, although the sample of dialysis centers was diverse with respect to geography, profit status, and nephrology practice affiliation, the number of centers was small, and participation was on the basis of centers’ interest in improving the quality of palliative care; therefore, the results may not be generalizable to other dialysis centers. Finally, because of the short duration of the study, we could not assess long-term sustainability.

Our evaluation offers several insights that could inform future trials of palliative care for patients with kidney failure. Telephone survey administration was not feasible owing to illness burden and call screening. Utilization of on-site interviewers and videoconferencing are two potential strategies to reduce missing patient-reported outcomes data in future studies. There was heterogeneity in baseline advance care planning documentation practices across centers, underscoring the importance of accounting for clustering effects in study design and analysis. Finally, this study describes rates of health care utilization in a seriously ill hemodialysis cohort that could be used to estimate sample size and plan economic analyses in future trials.

In summary, learning collaboratives may be an effective strategy to foster adoption of palliative care practices and improve advance care planning documentation in hemodialysis centers. To maximize the reach, effect, and sustainability of these practices, the learning collaborative should be paired with complementary strategies to promote communication skill building beyond implementation teams, address disincentives to palliative dialysis, and enhance nephrologist buy-in of palliative care models for seriously ill patients receiving dialysis.

Disclosures

G. Harbert reports honoraria from Fresenius Health Partners, Inc.; an advisory or leadership role for Fresenius Seamless Care of Dallas, LLC; and other interests or relationships as a consultant for the Renal Healthcare Association Educational Council. L. Holdsworth reports ownership interest in AbbVie and GlaxoSmithKline. M. Kurella Tamura reports employment with the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System; reports honoraria from the American Federation for Aging Research outside the submitted work; serves as an associate editor of CJASN; and serves in advisory or leadership roles for the Beeson External Advisory Committee and the Clin-Star Advisory Board. D.E. Lupu reports ownership interest in Southwest Gas Corporation; reports honoraria from and serves on the clinical advisory board of Monogram Health; and reports other interests or relationships with the Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients Executive Committee. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The authors acknowledge funding support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funder, the US Department of Veterans Affairs, or the US Government. Because Manjula Kurella Tamura is an associate editor of CJASN, she was not involved in the peer review process for this manuscript. Another editor oversaw the peer review and decision-making process for this manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Palliative Care for Hemodialysis Patients?,” on pages 1433–1435.

Author Contributions

M. Kurella Tamura, D.E. Lupu, E. Malcolm, and A.H. Moss conceptualized the study; A. Aldous, J. Han, and L. Holdsworth were responsible for data curation; J. Han, L. Holdsworth, and M. Stedman were responsible for formal analysis; M. Kurella Tamura, E. Malcolm, and M. Stedman were responsible for methodology; L. Holdsworth, M. Kurella Tamura, and D.E. Lupu were responsible for project administration; G. Harbert and A. Nicklas were responsible for resources; L. Holdsworth, M. Kurella Tamura, D.E. Lupu, and A.H. Moss were responsible for funding acquisition; A.H. Moss and M. Stedman provided supervision; M. Kurella Tamura wrote the original draft; and A. Aldous, S.M. Asch, G. Harbert, L. Holdsworth, K.A. Lorenz, D.E. Lupu, E. Malcolm, A.H. Moss, A. Nicklas, and M. Stedman reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

Individual participant data will not be shared.

Supplement Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00090122/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Material. Methods.

Supplemental Figure 1. Timeline of intervention delivery and data collection.

Supplemental Figure 2. Flow diagram of patient identification and outcome assessment in the preimplementation and postimplementation periods.

Supplemental Table 1. Overview of learning session objectives and activities.

Supplemental Table 2. Topic guide for interviews with implementation team members.

Supplemental Table 3. Advance care planning documentation and health care utilization among seriously ill patients during the pre- and postimplementation periods from multivariable adjusted models accounting for patient demographic characteristics with patient and center as random effects.

Supplemental Table 4. Advance care planning documentation among seriously ill patients in both the pre- and postimplementation periods from multivariable adjusted models accounting for patient demographic characteristics with patient and center as random effects.

References

- 1.Hole B, Hemmelgarn B, Brown E, Brown M, McCulloch MI, Zuniga C, Andreoli SP, Blake PG, Couchoud C, Cueto-Manzano AM, Dreyer G, Garcia Garcia G, Jager KJ, McKnight M, Morton RL, Murtagh FEM, Naicker S, Obrador GT, Perl J, Rahman M, Shah KD, Van Biesen W, Walker RC, Yeates K, Zemchenkov A, Zhao MH, Davies SJ, Caskey FJ: Supportive care for end-stage kidney disease: An integral part of kidney services across a range of income settings around the world. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 10: e86–e94, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris DCH, Davies SJ, Finkelstein FO, Jha V, Donner JA, Abraham G, Bello AK, Caskey FJ, Garcia GG, Harden P, Hemmelgarn B, Johnson DW, Levin NW, Luyckx VA, Martin DE, McCulloch MI, Moosa MR, O’Connell PJ, Okpechi IG, Pecoits Filho R, Shah KD, Sola L, Swanepoel C, Tonelli M, Twahir A, van Biesen W, Varghese C, Yang CW, Zuniga C; Working Groups of the International Society of Nephrology’s 2nd Global Kidney Health Summit : Increasing access to integrated ESKD care as part of universal health coverage. Kidney Int 95[4S]: S1–S33, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramer SJ, McCall NN, Robinson-Cohen C, Siew ED, Salat H, Bian A, Stewart TG, El-Sourady MH, Karlekar M, Lipworth L, Ikizler TA, Abdel-Kader K: Health outcome priorities of older adults with advanced CKD and concordance with their nephrology providers’ perceptions. J Am Soc Nephrol 29: 2870–2878, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurella Tamura M, Montez-Rath ME, Hall YN, Katz R, O’Hare AM: Advance directives and end-of-life care among nursing home residents receiving maintenance dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 435–442, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.O’Hare AM, Kurella Tamura M, Lavallee DC, Vig EK, Taylor JS, Hall YN, Katz R, Curtis JR, Engelberg RA: Assessment of self-reported prognostic expectations of people undergoing dialysis: United States Renal Data System Study of Treatment Preferences (USTATE). JAMA Intern Med 179: 1325–1333, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wachterman MW, Lipsitz SR, Lorenz KA, Marcantonio ER, Li Z, Keating NL: End-of-life experience of older adults dying of end-stage renal disease: A comparison with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage 54: 789–797, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier DE, Back AL, Berman A, Block SD, Corrigan JM, Morrison RS: A national strategy for palliative care. Health Aff (Millwood) 36: 1265–1273, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurella Tamura M, Meier DE: Five policies to promote palliative care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1783–1790, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakitas MA, Dionne-Odom JN, Ejem DB, Wells R, Azuero A, Stockdill ML, Keebler K, Sockwell E, Tims S, Engler S, Steinhauser K, Kvale E, Durant RW, Tucker RO, Burgio KL, Tallaj J, Swetz KM, Pamboukian SV: Effect of an early palliative care telehealth intervention vs usual care on patients with heart failure: The ENABLE CHF-PC randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 180: 1203–1213, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Broese JM, de Heij AH, Janssen DJ, Skora JA, Kerstjens HA, Chavannes NH, Engels Y, van der Kleij RM: Effectiveness and implementation of palliative care interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review. Palliat Med 35: 486–502, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amro OW, Ramasamy M, Strom JA, Weiner DE, Jaber BL: Nephrologist-facilitated advance care planning for hemodialysis patients: A quality improvement project. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 103–109, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Courtright KR, Madden V, Gabler NB, Cooney E, Kim J, Herbst N, Burgoon L, Whealdon J, Dember LM, Halpern SD: A randomized trial of expanding choice sets to motivate advance directive completion. Med Decis Making 37: 544–554, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goff SL, Unruh ML, Klingensmith J, Eneanya ND, Garvey C, Germain MJ, Cohen LM: Advance care planning with patients on hemodialysis: An implementation study. BMC Palliat Care 18: 64, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sellars M, Morton RL, Clayton JM, Tong A, Mawren D, Silvester W, Power D, Ma R, Detering KM: Case-control study of end-of-life treatment preferences and costs following advance care planning for adults with end-stage kidney disease. Nephrology (Carlton) 24: 148–154, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, Hanson LC, Lin FC, Hladik GA, Hamilton JB, Bridgman JC: Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: A randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 813–822, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL: Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 60: 946–950, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lupu DE, Aldous A, Anderson E, Schell JO, Groninger H, Sherman MJ, Aiello JR, Simmens SJ: Advance care planning coaching in CKD clinics: A pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Am J Kidney Dis 79: 699–708.e1, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perry E, Swartz J, Brown S, Smith D, Kelly G, Swartz R: Peer mentoring: A culturally sensitive approach to end-of-life planning for long-term dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 111–119, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Institute for Healthcare Improvement : The Breakthrough Series: Ihi’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement, 2003. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/IHIWhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModelforAchievingBreakthroughImprovement.aspx. Accessed September 10, 2021

- 21.Nembhard IM; Learning and Improving in Quality Improvement Collaboratives : Learning and improving in quality improvement collaboratives: Which collaborative features do participants value most? Health Serv Res 44: 359–378, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curtis JR, Kross EK, Stapleton RD: The importance of addressing advance care planning and decisions about do-not-resuscitate orders during novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA 323: 1771–1772, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupu DE, Aldous A, Harbert G, Kurella Tamura M, Holdsworth LM, Nicklas A, Vinson B, Moss AH: Pathways project: Development of a multimodal innovation to improve kidney supportive care in dialysis centers. Kidney360 2: 114–128, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grubbs V, Moss AH, Cohen LM, Fischer MJ, Germain MJ, Jassal SV, Perl J, Weiner DE, Mehrotra R; Dialysis Advisory Group of the American Society of Nephrology : A palliative approach to dialysis care: A patient-centered transition to the end of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2203–2209, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tentori F, Hunt A, Nissenson AR: Palliative dialysis: Addressing the need for alternative dialysis delivery modes. Semin Dial 32: 391–395, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, Gansor J, Senft S, Weaner B, Dalton C, MacKay K, Pellegrino B, Anantharaman P, Schmidt R: Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1379–1384, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foglia MB, Lowery J, Sharpe VA, Tompkins P, Fox E: A comprehensive approach to eliciting, documenting, and honoring patient wishes for care near the end of life: The Veterans Health Administration’s Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Initiative. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 45: 47–56, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VitalTalk . Available at: https://www.vitaltalk.org/. Accessed December 8, 2021

- 29.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF: The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot 12: 38–48, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute for Healthcare Improvement : Science of Improvement: Testing Changes, 2021. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementTestingChanges.aspx. Accessed December 28, 2021

- 31.Schabenberger O: Introducing the Glimmix Procedure for Generalized Linear Mixed Models, 2006. Available at: https://www.lexjansen.com/nesug/nesug05/an/an4.pdf. Accessed December 8, 2021

- 32.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M: Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 38: 65–76, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K: Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health 42: 533–544, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J: Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 4th Ed., Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Lum HD, Rietjens JAC, Korfage IJ, Ritchie CS, Hanson LC, Meier DE, Pantilat SZ, Lorenz K, Howard M, Green MJ, Simon JE, Feuz MA, You JJ: Outcomes that define successful advance care planning: A Delphi panelconsensus. J Pain Symptom Manage 55: 245–255.e8, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wachterman MW, Hailpern SM, Keating NL, Kurella Tamura M, O’Hare AM: Association between hospice length of stay, health care utilization, and Medicare costs at the end of life among patients who received maintenance hemodialysis. JAMA Intern Med 178: 792–799, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA: System-level barriers and facilitators for foregoing or withdrawing dialysis: A qualitative study of nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis 70: 602–610, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.