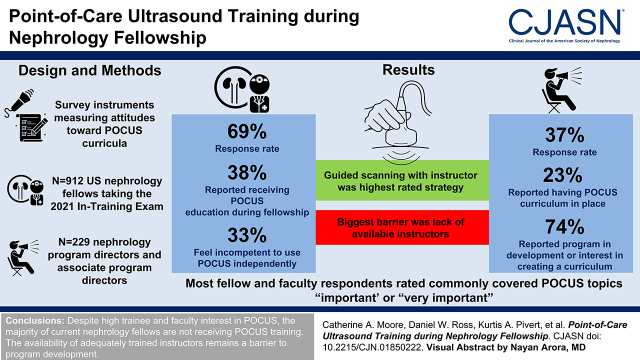

Visual Abstract

Keywords: echocardiography, dialysis access, kidney biopsy, kidney anatomy, nephrology, vascular access, fellowships and scholarships, point-of-care systems

Abstract

Background and objectives

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS)—performed by a clinician during a patient encounter and used in patient assessment and care planning—has many potential applications in nephrology. Yet, US nephrologists have been slow to adopt POCUS, which may affect the training of nephrology fellows. This study sought to identify the current state of POCUS training and implementation in nephrology fellowships.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Concise survey instruments measuring attitudes toward POCUS, its current use, fellow competence, and POCUS curricula were disseminated to (1) 912 US nephrology fellows taking the 2021 Nephrology In-Training Examination and (2) 229 nephrology training program directors and associate program directors. Fisher exact, chi-squared, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the frequencies of responses and the average responses between fellows and training program directors/associate program directors when possible.

Results

Fellow and training program directors/associate program directors response rates were 69% and 37%, respectively. Only 38% of fellows (240 respondents) reported receiving POCUS education during their fellowship, and just 33% of those who did receive POCUS training reported feeling competent to use POCUS independently. Similarly, just 23% of training program directors/associate program directors indicated that they had a POCUS curriculum in place, although 74% of training program directors and associate program directors indicated that a program was in development or that there was interest in creating a POCUS curriculum. Most fellow and faculty respondents rated commonly covered POCUS topics—including dialysis access imaging and kidney biopsy—as “important” or “very important,” with the greatest interest in diagnostic kidney ultrasound. Guided scanning with an instructor was the highest-rated teaching strategy. The most frequently reported barrier to POCUS program development was the lack of available instructors.

Conclusions

Despite high trainee and faculty interest in POCUS, the majority of current nephrology fellows are not receiving POCUS training. Hands-on training guided by an instructor is highly valued, yet availability of adequately trained instructors remains a barrier to program development.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/CJASN/2022_09_21_CJN01850222.mp3.

Introduction

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) is a bedside diagnostic tool used to augment the physical examination and guide focused clinical decisions. Emergency medicine adopted POCUS in the mid-1990s, and its use has rapidly expanded to other fields of medicine. Many argue that POCUS should be incorporated as the fifth pillar of the bedside physical examination (1). As clinical applications for POCUS multiply, interest in applications in the practice of nephrology has grown. An educational needs assessment conducted in 2016 found that nephrology fellows rated kidney ultrasound interpretations as a top desired topic for additional instruction (2). Despite the many potential applications of focused ultrasound in assessment of patients with kidney disease, nephrologists have been slow to adopt this technology (3,4).

The past 5 years have seen an increase in ultrasound training within nephrology fellowship programs, although the scope of this training is unknown. Therefore, the nephrology community needs a better understanding of the current educational landscape to anchor future discussions regarding defined competencies and curriculum development.

We aimed to assess the adoption of—and mechanisms used for—current POCUS training in nephrology fellowship programs and to understand current POCUS use by and perceived competence among nephrology trainees. As POCUS program development is a multistep process involving recruitment of material and faculty resources, we also sought to better describe perceived barriers to the successful adoption of POCUS training in nephrology fellowships.

Materials and Methods

Survey Instruments

We used two complementary research surveys to assess the current state of POCUS training in US nephrology fellowships from the perspective of both trainee and training program directors (TPDs)/associate program directors (APDs). A panel of nephrologists formally trained in POCUS who have expertise in ultrasound education and/or survey development was established to develop survey instruments measuring the adoption of POCUS within nephrology fellowship training (Supplemental Table 1 has survey domains and subdomains). Items were evaluated by a larger group of POCUS educators in nephrology at a national meeting, and formal review of survey items was provided by two faculty members at the University of Rochester with expertise in survey design. Cognitive pretesting was performed by two nephrologists at the University of Rochester with no ties to this study. Instruments were reviewed and edited for length by the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Data Subcommittee to comply with question and space limits, and the surveys were approved by the ASN Workforce and Training Committee for inclusion in the Nephrology In-Training Examination survey (nephrology fellows) and a dedicated ASN flash poll (TPDs/APDs).

Survey Audiences and Dissemination

The fellow audience comprised 912 US nephrology trainees taking the 2021 Nephrology In-Training Examination conducted between April 14 and 16, 2021. Fellows were exposed to the survey instrument upon test completion, and after informed consent, they were provided the option to not share their survey responses. In addition to the POCUS items, demographic information—including age, race, medical school classification, and sex—were collected by the National Board of Medical Examiners, and identifying information was removed prior to data sharing with the investigators. The faculty portion was disseminated in an anonymous ASN flash poll by email (using SurveyMonkey software) to 229 nephrology TPDs and APDs on July 17, 2021. After two reminders encouraging survey completion, the flash poll closed on August 16, 2021.

The two surveys and study protocol were deemed exempt by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board and are in keeping with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Item response types included Likert scale, single best response multiple choice, and multiple selected response. All survey responses were kept confidential, and there were no monetary incentives to participate.

Data were analyzed using R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Fisher exact, chi-squared, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare frequencies of responses and average response between fellows and TPDs/APDs when possible. Statistical tests were considered significant at α=0.05.

Results

Survey Response

A total of 631 nephrology fellows participated in the trainee survey (69% response rate), and 84 TPDs and APDs responded to the flash poll (37% response rate). A majority (376) of fellow respondents identified as men and were international medical graduates (378), with 214 reporting White race and 69 reporting Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity. Respondent demographic characteristics were similar to the nephrology fellow population, of which 60% were men, 66% were international medical graduates, 29% were White, and 9% were of Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity, according to data from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (5).

Attitudes toward Point-of-Care Ultrasound: Importance of Point-of-Care Ultrasound Topics to Nephrology Training

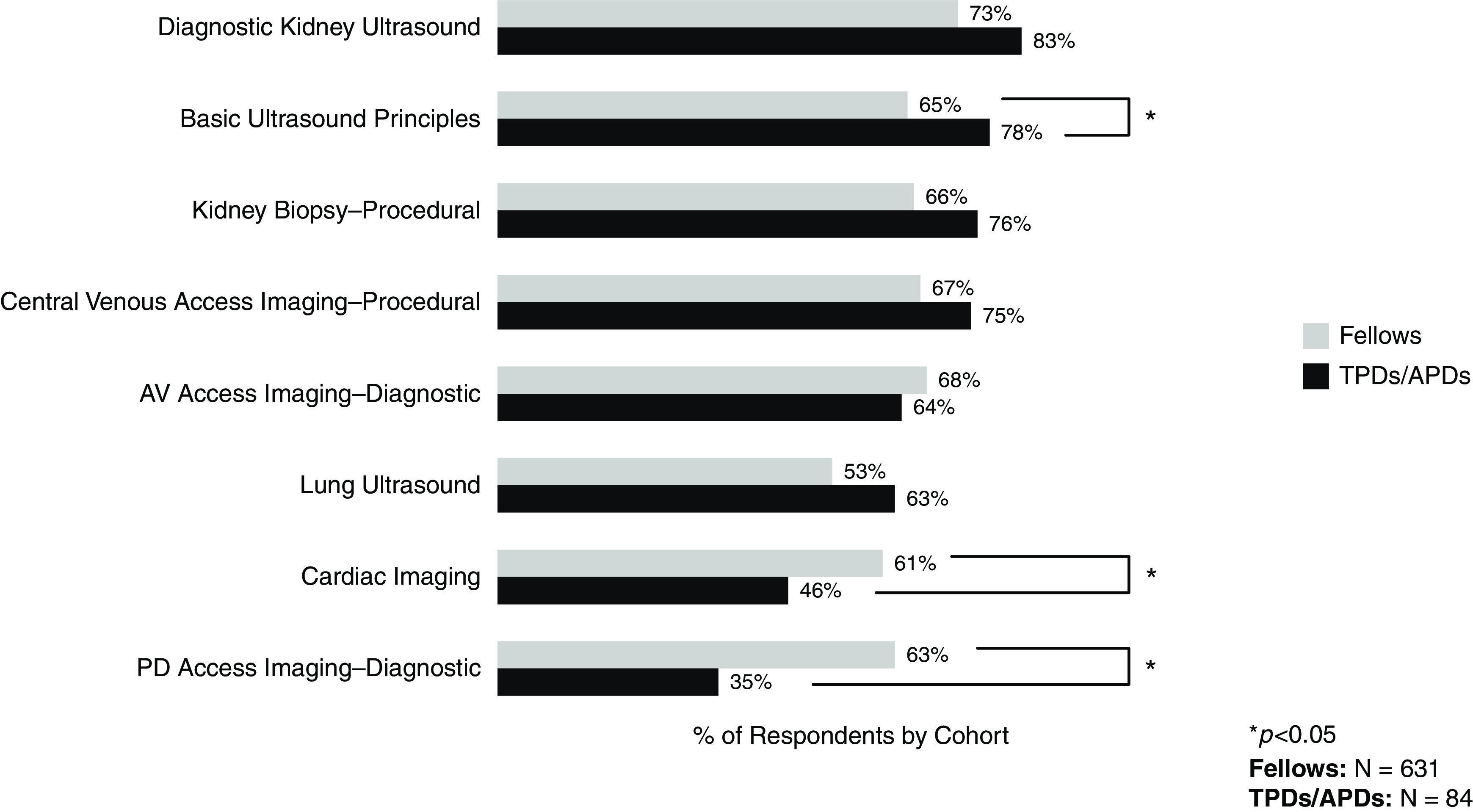

There seemed to be some agreement between nephrology trainees and TPDs/APDs about which nephrology POCUS topics were rated “important” or “very important”—including diagnostic kidney ultrasound and the use of POCUS in kidney biopsies; however, differences between cohorts were statistically significant (Figure 1) (P=0.01). Among the topics with the greatest divergence were basic ultrasound principles, with a greater proportion of TPDs/APDs indicating their importance (78% [64 of 82] versus 65% [356 of 547] of nephrology fellows; P<0.001), and more fellows perceived peritoneal dialysis access imaging as critical (63% [347 of 554] versus 35% [29 of 82] of TPDs/APDs; P<0.001). Procedural imaging implementations were similarly highly ranked, including kidney biopsy (fellows: 66% [397 of 597]; faculty: 76% [62 of 82]) and guidance for central vein cannulation (fellows: 67% [369 of 552]; faculty: 75% [62 of 83]).

Figure 1.

Nephrology point-of-care ultrasound topics rated “important”/“very important” for nephrology training by fellow and training program director (TPD)/associate program director (APD) respondents. Brackets indicate statistically significant differences between cohorts. AV, arteriovenous; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Current Point-of-Care Ultrasound Curriculum

Curriculum Development Stage.

Just 38% of fellows (240 of 631) and 23% of TPDs/APDs (19 of 84) reported having an established POCUS curriculum within their training program (P=0.004). An additional 38% (32 of 84) of TPDs/APDs reported having a curriculum in development, and 36% (30 of 84) reported that there was no program in development but that they had an interest in establishing a curriculum. Only 4% (three of 84) of the faculty surveyed reported having no interest in developing a POCUS curriculum within their program.

Ultrasound Topics.

TPDs/APDs indicated that diagnostic kidney ultrasound, basic ultrasound principles, and lung ultrasound were the most common components within both established (n=19) and developing (n=32) curricula (Table 1). Programs with interest in the development of POCUS curriculum similarly prioritized these topics. More than half of TPDs/APDs from established and developing programs reported incorporation of procedural imaging, with central venous access more commonly included than kidney biopsy. The least commonly emphasized topics by programs in all stages of development were ultrasound-guided arteriovenous access cannulation and peritoneal dialysis access diagnostic imaging.

Table 1.

Curricular details reported by training program directors and associate program directors in all stages of development

| Parameter | Faculty, n=81a | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Established Curriculum, n=19 | Curriculum in Development, n=32 | No Curriculum in Development but Interested, n=30 | |

| Topics covered or planned to be covered in POCUS curriculum, n (%) | |||

| Basic ultrasound principles | 17 (90) | 27 (84) | 22 (73) |

| Diagnostic kidney ultrasound | 18 (95) | 28 (88) | 25 (83) |

| Cardiac imaging | 10 (5) | 17 (53) | 12 (40) |

| Lung ultrasound | 15 (79) | 20 (63) | 18 (56) |

| AV access imaging—diagnostic | 9 (47) | 14 (44) | 12 (40) |

| PD access imaging—diagnostic | 1 (5) | 4 (13) | 4 (13) |

| AV access imaging—ultrasound-guided cannulation | 3 (16) | 7 (22) | 3 (10) |

| Central venous access imaging—procedural | 13 (68) | 18 (56) | 15 (50) |

| Kidney biopsy—procedural | 11 (58) | 16 (50) | 17 (57) |

| Structure of POCUS training in program, n (%) | |||

| Intensive block experience | 4 (21) | 7 (22) | 7 (23) |

| Longitudinal training experience | 16 (84) | 24 (75) | 20 (67) |

POCUS, point-of-care ultrasound; AV, arteriovenous; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Lowercase “n” values indicate the total number of respondents for each question section. Values are presented as the number of responses (percentage of per question respondent totals).

Curriculum Structure.

Regardless of the development stage, a majority of faculty respondents indicated that their POCUS curricula included (or would include) a longitudinal training experience. In contrast, an intensive block experience component was included by <25% of curricula in all stages of development.

Of the 19 TPD/APD respondents with an established POCUS curriculum, the vast majority (95%; 18 of 19) use direct observation to assess fellow competence (Table 2). More than half of TPDs/APDs included a combined portfolio (ultrasound video clips for remote review, 58% of programs), whereas knowledge tests, objective structured clinical examinations, and requiring a minimum number of studies were less commonly reported assessment strategies.

Table 2.

Assessment strategies and instructor background reported by training program directors and associate program directors in established programs

| Parameter | Item Response |

|---|---|

| Current strategies for assessing fellow competence in POCUS, n (%) | n=19 |

| Direct observation | 18 (95) |

| Knowledge test | 5 (26) |

| OSCE | 5 (26) |

| POCUS portfolio (ultrasound video clips for remote review) | 11 (58) |

| Required minimum no. of studies | 1 (5) |

| POCUS instructor background, n (%) | n=19 |

| Nephrology | 19 (100) |

| Cardiology | 0 (0) |

| Emergency medicine | 2 (11) |

| Pulmonary/critical care | 6 (32) |

| Ultrasound technologist | 2 (11) |

| Hospital medicine | 2 (11) |

| Anesthesia | 1 (5) |

Lowercase “n” values indicate the total number of respondents for each question section. Values are presented as the number of responses (percentage of per question respondent totals). POCUS, point-of-care ultrasound; OSCE, objective structured clinical examination.

All 19 respondents from established programs reported using nephrologists as POCUS instructors. Approximately one third of TPDs/APDs reported that pulmonologists/intensivists participated as instructors in their curricula. Instructors from other disciplines were not commonly reported by TPDs/APDs with established POCUS training programs.

Barriers to Curriculum Development.

The primary barrier to POCUS curriculum development as reported by TPDs/APDs with either established or developing programs (n=51) was a lack of trained faculty (Table 3). Access to ultrasound equipment and the perceived inability to bill point-of-care studies rounded out the top three deterrents. TPDs/APDs in programs with established POCUS curricula less commonly reported time for curriculum development as a barrier (21%; four of 19); however, those from developing programs more frequently noted time as an issue (38%; 12 of 32).

Table 3.

Barriers to point-of-care ultrasound curriculum development reported by training program directors and associate program directors

| Parameter n (%) | Established Curriculum, n=19 | Curriculum in Development, n=32 |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound machine access | 6 (32) | 11 (34) |

| Fear of missing an important diagnosis | 5 (26) | 8 (25) |

| Financial concerns | 4 (21) | 8 (25) |

| Inability to bill | 6 (32) | 11 (34) |

| No data supporting that POCUS expedites care | 2 (11) | 3 (9) |

| No interest/support from division/department | 1 (5) | 3 (9) |

| No time for curriculum development | 4 (21) | 12 (38) |

| No trained faculty | 10 (53) | 17 (53) |

| Opposition from other ultrasound-trained physicians | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

| Ultrasound studies are immediately available | 1 (5) | 3 (9) |

| None | 2 (11) | 7 (22) |

Lowercase “n” values indicate the total number of respondents for each question section. Values are presented as the number of responses (percentage of per question respondent totals). POCUS, point-of-care ultrasound.

Effectiveness of Point-of-Care Ultrasound Educational Strategy.

Among fellows reporting an established POCUS curriculum within their program, guidance by an instructor during scanning was most commonly valued as an effective educational strategy (Table 4). Other hands-on educational opportunities, including independent scanning and practice with simulated patients, were considered to be effective educational techniques by the majority of fellows. In contrast, online modules for POCUS education were less commonly rated as effective or highly effective by fellows.

Table 4.

Fellow survey responses

| Parameter | Fellows Reporting Point-of-Care Ultrasound Curriculuma |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness of educational strategy rated “somewhat effective” or “very effective,” n (%) b | |

| Online modulesc | 98 (43) |

| Independent scanningc | 142 (63) |

| Guided scanning with instructord | 174 (77) |

| Simulated patientse | 145 (66) |

| Frequency of POCUS use, n (%) | n=227 |

| Never | 22 (10) |

| <1 time/mo | 90 (40) |

| >1 time/mo but <1 time/wk | 67 (30) |

| >1 time/wk but <1 time/d | 40 (18) |

| >1 time/d | 8 (4) |

| NA | 13 (6) |

| Received adequate instruction to independently perform POCUS, n (%) | n=226 |

| Strongly agree | 21 (9) |

| Agree | 62 (27) |

| Neutral | 88 (39) |

| Disagree | 41 (18) |

| Strongly disagree | 14 (6) |

| NA | 14 (6) |

POCUS, point-of-care ultrasound; NA, not available.

Lowercase “n” values indicate the total number of responses for each question section. Values are presented as the number of responses (percentage of per question respondent totals). The total number of available respondents was 240.

Five-point Likert scale: very effective, effective, neutral, somewhat ineffective, or very ineffective.

The total number of respondents for this survey item was 224.

The total number of respondents for this survey item was 226.

The total number of respondents for this survey item was 221.

Perceived Point-of-Care Ultrasound Competence

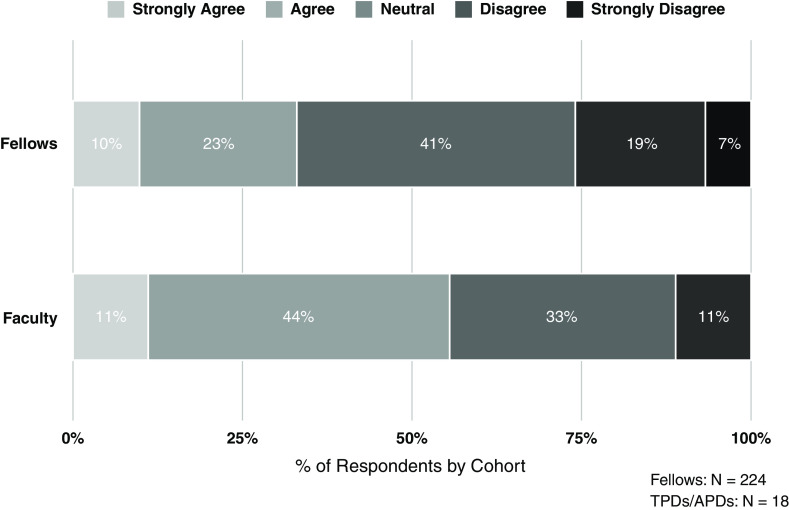

Fellows who received POCUS training reported using it infrequently during their daily clinical activities, either less than once a month (40%; 90 of 227) or not at all (10%; 22 of 227). When asked if they received adequate instruction within their nephrology training to independently perform POCUS, 37% (83 of 226) of fellows agreed or strongly agreed. Among TPDs and APDs responding from programs with established POCUS curricula (n=19), approximately half (nine of 19) felt that their graduating trainees would be competent to independently perform POCUS (Figure 2). Only 33% (74 of 224) of fellows reported feeling that they would be competent to independently perform POCUS by the end of their nephrology training. Differences in trainee and TPD/APD assessments of fellow POCUS competence were not statistically significant (P=0.06).

Figure 2.

Comparison of fellow and TPD/APD agreement that fellows are competent to independently perform point-of-care ultrasound at the completion of training.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that a majority of current US nephrology fellows consider POCUS topics to be important to their training and practice, most prominently diagnostic kidney ultrasound and kidney biopsy. Similarly, the vast majority of TPD/APD respondents believe that POCUS education is an important part of nephrology training, with diagnostic kidney ultrasound ranking highest and basic ultrasound principles and procedural imaging (kidney biopsy and central venous access) considered important by >70%. Notably, nearly all (96%) of the surveyed faculty reported at least an interest in developing a POCUS curriculum. Yet despite this, only 38% of fellows reported the presence of POCUS education within their training programs. This aligned with TPD/APD responses indicating that only 23% of programs have an established curriculum and that an additional 38% have a curriculum in development. Notably, of fellows who had access to POCUS training, only 33% agreed they would be prepared for independent practice in the modality by graduation. This highlights a need to address barriers to curriculum development and implementation.

Surveyed faculty most frequently reported a lack of available instructors as a barrier to POCUS program development, which was listed by more than half of the faculty with established and developing curricula. This challenge is certainly not unique to nephrology training, as access to adequate instruction and supervision is a commonly cited concern by trainees and faculty across multiple disciplines (5,6). It is notable that despite this barrier, all established programs primarily report nephrologists serving as POCUS instructors for their fellows, suggesting that a successful program requires trained instructors within the discipline. Reliance on instructors outside of nephrology, a strategy that may mitigate the limited availability of trained faculty (6), is reported in less than one third of established programs. Collaboration across disciplines may not align with the specific scope of training most valued by nephrologists, particularly with regard to kidney biopsy and kidney and arteriovenous access diagnostic imaging. Additionally, a recent survey of internal medicine residency programs indicated that diagnostic ultrasounds of the kidney and bladder are not commonly included in POCUS curricula, highlighting a need for nephrologists to champion this domain (7).

Other internal medicine subspecialties have supported faculty and trainee POCUS education. The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) has developed a national critical care ultrasound training course (8). Additionally, POCUS training is an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement in critical care, and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) has endorsed the use of POCUS and now offers POCUS training and certification (in collaboration with CHEST) (7). The overall push toward incorporating POCUS into internal medicine includes residency training. The Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM) released a position statement in 2019 supporting POCUS education in internal medicine residency (9), and a recent survey found that 95% of internal medicine residencies report incorporation of diagnostic POCUS (7).

Faculty respondents from programs with established POCUS curricula most commonly reported covering diagnostic kidney ultrasound and basic ultrasound principles. Procedural imaging, although strongly valued by fellows as well as TPDs/APDs, was less commonly covered within established programs. It is notable that despite the many potential applications of lung and cardiac ultrasound to the care of patients with kidney disease (10–12), incorporation of cardiopulmonary imaging into training is not universal among established POCUS nephrology curricula. This may again reflect the challenge of access to training by faculty.

Ultrasound-based volume assessment is being taught in more than half of US medical schools; is an Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requirement for critical care; and is endorsed by CHEST, SHM, and AAIM (13). Ultrasound-based volume assessment is part of the future of internal medicine. Most, if not all, internal medicine courses and curricula teach integrative lung and cardiac ultrasound as the cornerstone of ultrasound-based volume assessment. As volume experts, nephrologists need to understand ultrasound-based volume assessment, including not just its advantages but also its limitations. There is already a small but growing literature outlining how lung ultrasound and cardiac ultrasound apply specifically to patients with kidney disease (14,15).

In consideration of the effectiveness of POCUS teaching, guided scanning with an instructor was the highest-rated strategy by fellows. Notably, this is the most labor-intensive approach to training and highlights the importance of the lack of available instructors. Other hands-on training opportunities, including independent scanning and work with simulated patients, were also highly rated by fellows and could be used to supplement experiential learning without additional time investment by instructors. The pedagogical value of adding hands-on experience to procedural training has been well established and has been applied to POCUS education (16). Our findings support the need for POCUS programs to provide in-person training and access to ultrasound equipment for practice.

The vast majority of established programs report a longitudinal component to their POCUS curriculum. This structure allows for distributed practice (hands-on learning interspersed with periods of rest), a motor-learning principle with demonstrated beneficial effects on skill acquisition and retention that has been applied to surgical skills training (17). As bedside ultrasound skills deteriorate over time without repeated practice (18), it behooves POCUS educators to incorporate spaced learning in order to enhance skills retention. Our study demonstrates that POCUS educators in nephrology are using a curriculum structure consistent with those incorporated by emergency, internal, and critical care medicine training programs.

Current US nephrology fellows who have received POCUS training report low levels of perceived competence. Faculty assessment of trainee competence is similar, although slightly more optimistic. Similarly, POCUS is infrequently used by fellows who have received training, with only 22% reporting using it more than once per week. Unfortunately, these findings are similar to the self-reported competence and frequency of POCUS among learners in other specialties; although in other studies, reported clinical use alarmingly exceeded the perceived competence of operators (5,6). Although these metrics certainly raise concern about the effectiveness of current teaching strategies, the fellow responses could not be linked to specific training programs, and therefore, it is possible that fellows within programs with long established POCUS curricula would display more confidence in their ultrasound skills and would be more likely to frequently incorporate them into their clinical activities. Frequency of ultrasound use within a program could also be associated with the cumulative perceived competence of both faculty and trainees, as this tool is more likely to be incorporated into daily clinical activities when modeled by faculty mentors. An additional concern is the ability of faculty to assess fellows in this domain, as faculty training remains a prominent barrier to program development. When considering best approaches to faculty development in POCUS, assessment should be included within the training.

Within other specialties, including critical care, hospital medicine, and internal medicine, POCUS training for faculty has been incorporated into regional as well as national meetings. For example, both CHEST and SHM offer a pathway for POCUS certification following attendance at an approved hands-on course (19,20). These courses are offered multiple times per year throughout the United States. The American College of Physicians offers a virtual live training POCUS mentorship program (21). Our professional societies in nephrology should consider a similar model to help “train the trainers.”

This study has several limitations. Because of the space constraints of In-service Training Exam and flash poll surveys, our survey scope was restricted by the number of questions we were able to include. We were unable to obtain program information for fellow respondents, and therefore, we were unable to determine the relationships between program size and geographic location to POCUS curriculum specifics. Additionally, we were unable to survey fellows regarding curricular details or barriers to use. We were similarly unable to obtain demographics on faculty respondents and therefore could not compare faculty perceptions with fellow perspectives within a program. Although the faculty survey was sent to all US nephrology TPDs and APDs, only 37% of those surveyed responded, and their results may not be generalizable. We were unable to limit survey respondents per program, and therefore, equal representation of programs is not guaranteed. Additionally, selection bias is a concern, particularly by the nature of the instrument, as those faculty less interested in POCUS curriculum development may be less likely to complete the survey. Strengths of the survey include fellow response rate as well as the coordination of the instrument across survey groups, allowing for a direct comparison of fellow and faculty perspectives on the same issue.

In summary, although POCUS is a highly valued clinical skill among nephrology trainees and teaching faculty, bedside ultrasound teaching is incorporated in only a minority of training programs. Competence of fellows to independently perform POCUS, as perceived by trainees and faculty, is low, and clinical use of POCUS by fellows is infrequent. Current training relies heavily on skilled instructors, and availability of faculty educators remains a prominent barrier to curriculum development. To address this, we recommend investment in the POCUS education of faculty instructors within nephrology training programs, including the development of hands-on courses paired with certification pathways tailored to priority topics within nephrology. In addition, a priority of faculty development should include best approaches to the assessment of trainee competence in POCUS.

Disclosures

W.C. O'Neill reports consultancy agreements with Inozyme Pharma; ownership interest in Inozyme Pharma; research funding from Fresenius Medical Care Renal Therapies Group and the National Institutes of Health; royalties from UpToDate; advisory or leadership roles for Elastrin Therapeutics and Inozyme Pharma; and income from educational material related to ultrasonography. K.A Pivert is an employee of ASN. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the nephrology fellows, nephrology TPDs, associate training program directors, and faculty who contributed their insights to this research.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Incorporating Training in POCUS in Nephrology Fellowship Curriculum,” on pages 1442–1445.

Author Contributions

V.J. Lang and C.A. Moore conceptualized the study; C.A. Moore and K.A. Pivert were responsible for data curation; D.W. Ross was responsible for investigation; K.A. Pivert and S.M. Sozio were responsible for formal analysis; V.J. Lang, C.A. Moore, and D.W. Ross were responsible for methodology; C.A. Moore was responsible for project administration; W.C. O'Neill was responsible for resources; K.A. Pivert was responsible for software; V.J. Lang provided supervision; C.A. Moore, K.A. Pivert, and D.W. Ross wrote the original draft; and V.J. Lang, C.A. Moore, W.C. O'Neill, D.W. Ross, and S.M. Sozio reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

All data used in this study are available in the article and/or Supplemental Material.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.01850222/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Material. Fellow survey instrument and faculty survey instrument.

Supplemental Table 1. Survey domains and subdomains.

Supplemental Table 2. Demographic characteristics of 631 fellow survey respondents.

Supplemental Table 3. Stage of POCUS program development as reported by fellows and training/associate program directors.

Supplemental Figure 1. Importance of nephrology POCUS topics for nephrology training rated by fellow (left panel) and training/associate program director (right panels) respondents.

References

- 1.Narula J, Chandrashekhar Y, Braunwald E: Time to add a fifth pillar to bedside physical examination: Inspection, palpation, percussion, auscultation, and insonation. JAMA Cardiol 3: 346–350, 2018. 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rope RW, Pivert KA, Parker MG, Sozio SM, Merell SB: Education in nephrology fellowship: A survey-based needs assessment. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 1983–1990, 2017. 10.1681/ASN.2016101061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niyyar VD, O’Neill WC: Point-of-care ultrasound in the practice of nephrology. Kidney Int 93: 1052–1059, 2018. 10.1016/j.kint.2017.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Neill WC, Ross DW: Retooling nephrology with ultrasound. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 771–773, 2019. 10.2215/CJN.10430818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anstey JE, Jensen TP, Afshar N: Point-of-care ultrasound needs assessment, curriculum design, and curriculum assessment in a large academic internal medicine residency program. South Med J 111: 444–448, 2018. 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wenger J, Steinbach TC, Carlbom D, Farris RW, Johnson NJ, Town J: Point of care ultrasound for all by all: A multidisciplinary survey across a large quaternary care medical system. J Clin Ultrasound 48: 443–451, 2020. 10.1002/jcu.22894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soni NJ, Schnobrich D, Mathews BK, Tierney DM, Jensen TP, Dancel R, Cho J, Dversdal RK, Mints G, Bhagra A, Reierson K, Kurian LM, Liu GY, Candotti C, Boesch B, LoPresti CM, Lenchus J, Wong T, Johnson G, Maw AM, Franco-Sadud R, Lucas BP: Point-of-care ultrasound for hospitalists: A position statement of the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med 14: E1–E6, 2019. 10.12788/jhm.3079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenstein YY, Littauer R, Narasimhan M, Mayo PH, Koenig SJ: Effectiveness of a critical care ultrasonography course. Chest 151: 34–40, 2017. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.08.1465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LoPresti CM, Jensen TP, Dversdal RK, Astiz DJ: Point-of-care ultrasound for internal medicine residency training: A position statement from the Alliance of Academic Internal Medicine. Am J Med 132: 1356–1360, 2019. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covic A, Siriopol D, Voroneanu L: Use of lung ultrasound for the assessment of volume status in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 412–422, 2018. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karakala N, Córdoba D, Chandrashekar K, Lopez-Ruiz A, Juncos LA: Point-of-care ultrasound in acute care nephrology. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 28: 83–90, 2021. 10.1053/j.ackd.2021.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torino C, Gargani L, Sicari R, Letachowicz K, Ekart R, Fliser D, Covic A, Siamopoulos K, Stavroulopoulos A, Massy ZA, Fiaccadori E, Caiazza A, Bachelet T, Slotki I, Martinez-Castelao A, Coudert-Krier MJ, Rossignol P, Gueler F, Hannedouche T, Panichi V, Wiecek A, Pontoriero G, Sarafidis P, Klinger M, Hojs R, Seiler-Mussler S, Lizzi F, Siriopol D, Balafa O, Shavit L, Tripepi R, Mallamaci F, Tripepi G, Picano E, London GM, Zoccali C: The agreement between auscultation and lung ultrasound in hemodialysis patients: The LUST study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 2005–2011, 2016. 10.2215/CJN.03890416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell FM, Zakeri B, Herbert A, Ferre RM, Leiser A, Wallach PM: The state of point-of-care ultrasound training in undergraduate medical education: Findings from a national survey. Acad Med 97: 723–727, 2022. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000004512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koratala A, Chamarthi G, Kazory A: Point-of-care ultrasonography for objective volume management in end-stage renal disease. Blood Purif 49: 132–136, 2020. 10.1159/000503000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koratala A, Kazory A: Point of care ultrasonography for objective assessment of heart failure: Integration of cardiac, vascular, and extravascular determinants of volume status. Cardiorenal Med 11: 5–17, 2021. 10.1159/000510732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matthews L, Contino K, Nussbaum C, Hunter K, Schorr C, Puri N: Skill retention with ultrasound curricula. PLoS One 15: e0243086, 2020. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moulton CA, Dubrowski A, Macrae H, Graham B, Grober E, Reznick R: Teaching surgical skills: What kind of practice makes perfect? A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg 244: 400–409, 2006. 10.1097/01.sla.0000234808.85789.6a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rappaport CA, McConomy BC, Arnold NR, Vose AT, Schmidt GA, Nassar B: A prospective analysis of motor and cognitive skill retention in novice learners of point of care ultrasound. Crit Care Med 47: e948–e952, 2019. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Society for Hospital Medicine : POCUS Certificate of Completion. Available at: https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/clinical-topics/ultrasound/pocus-certificate-of-completion/. Accessed April 25, 2022

- 20.American College of Chest Physicians : Point of Care Ultrasound Certificate of Completion. Available at: https://www.chestnet.org/Learning/certificate-of-completion/POCUS. Accessed April 25, 2022

- 21.ACP : Point of Care Ultrasound Mentorship Program, 2022. Available at: https://www.acponline.org/meetings-courses/focused-topics/point-of-care-ultrasound-pocus-for-internal-medicine/point-of-care-ultrasound-mentorship-program. Accessed April 25, 2022

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.