Significance Statement

Dialysis is lifesaving for patients with ESKD, but replaces only 10% of normal kidney function, leaving these patients with a chronic urea overload. One unavoidable consequence of excess urea is carbamylation, a post-translational modification that interferes with biologic functions of proteins. In this study, the authors found that platelets from patients with ESKD exhibit carbamylation-triggered structural alterations in integrin αIIbβ3, associated with a fibrinogen-binding defect and impaired platelet aggregation. Given that lysine 185 in the β3 subunit seems to play a pivotal role in receptor activation, carbamylation of this residue may represent a mechanistic link between uremia and dysfunctional primary hemostasis in patients. Supplementation of free amino acids prevented loss of αIIbβ3 function, suggesting amino acid administration may have a beneficial effect on uremic platelet dysfunction.

Keywords: chronic hemodialysis, chronic kidney failure, end stage renal disease, platelets, uremia, coagulation, carbamylation, protein carbamylation

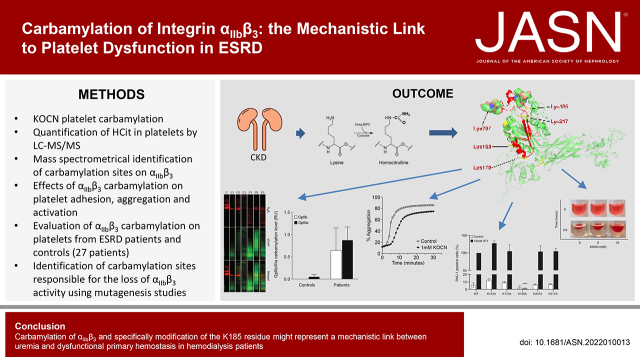

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Bleeding diatheses, common among patients with ESKD, can lead to serious complications, particularly during invasive procedures. Chronic urea overload significantly increases cyanate concentrations in patients with ESKD, leading to carbamylation, an irreversible modification of proteins and peptides.

Methods

To investigate carbamylation as a potential mechanistic link between uremia and platelet dysfunction in ESKD, we used liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) to quantify total homocitrulline, and biotin-conjugated phenylglyoxal labeling and Western blot to detect carbamylated integrin αIIbβ3 (a receptor required for platelet aggregation). Flow cytometry was used to study activation of isolated platelets and platelet-rich plasma. In a transient transfection system, we tested activity and fibrinogen binding of different mutated forms of the receptor. We assessed platelet adhesion and aggregation in microplate assays.

Results

Carbamylation inhibited platelet activation, adhesion, and aggregation. Patients on hemodialysis exhibited significantly reduced activation of αIIbβ3 compared with healthy controls. We found significant carbamylation of both subunits of αIIbβ3 on platelets from patients receiving hemodialysis versus only minor modification in controls. In the transient transfection system, modification of lysine 185 in the β3 subunit was associated with loss of receptor activity and fibrinogen binding. Supplementation of free amino acids, which was shown to protect plasma proteins from carbamylation-induced damage in patients on hemodialysis, prevented loss of αIIbβ3 activity in vitro.

Conclusions

Carbamylation of αIIbβ3—specifically modification of the K185 residue—might represent a mechanistic link between uremia and dysfunctional primary hemostasis in patients on hemodialysis. The observation that free amino acids prevented the carbamylation-induced loss of αIIbβ3 activity suggests amino acid administration during dialysis may help to normalize platelet function.

Uremic bleeding is a complication of renal insufficiency.1,2 Up to 50% of patients with ESKD are affected by hemostatic dysfunctions, with manifestations that range from easy bruising and prolonged bleeding at the vascular access site to potentially life-threatening conditions, such as gastrointestinal and intracranial bleeding.3,4 The coagulation system undergoes profound changes during renal disease, but the underlying mechanisms remain unclear.1,5 Although the pathogenesis of bleeding is most likely multifactorial, acquired defects in primary hemostasis seem to play a major role because hemorrhage occurs in the presence of normal concentrations of coagulation factors and normal platelet counts.6,7 Moreover, prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time are unaffected by uremia, whereas bleeding time, an indirect measure of platelet function, is almost always elevated.5,7 The improvement of uremic thrombocytopathies by modern hemodialysis (HD) techniques indicates uremic toxins are, at least partially, responsible for the observed platelet dysfunctions.8,9 Dialysis, however, cannot eliminate the risk but is even conducive to hemorrhage due to continuous platelet activation and the use of anticoagulants. Consequently, bleeding diatheses remain a problem for patients with ESKD, particularly during invasive procedures, and strategies are needed to achieve better management of bleeding complications.10,11

Uremia, the clinical condition associated with ESKD, results from the retention of waste products that, under physiologic conditions, are cleared by the kidneys.12,13 Once these compounds, collectively known as uremic toxins, accumulate, they can exert devastating effects on almost all organ systems.14 Urea is quantitatively the most abundant retention solute in the body, where it is in equilibrium with the reactive metabolite cyanate.15 Cyanate can react with N-terminal amino groups of proteins, peptides, and lysine residues, resulting, in the latter case, in the formation of carbamyllysine (homocitrulline; [HCit]).16 This irreversible modification can occur at multiple sites within a single protein, altering charge, structure, and function.17,18 Cyanate concentrations can be up to three times higher in patients with ESKD than in healthy individuals, resulting in an increased generation of carbamylated compounds, which are involved in the progression of kidney failure and the development of complications of ESKD, and have clinical value as biomarkers due to their association with cardiovascular and overall mortality.18–20 Additionally, elevated serum cyanate concentrations can have a major effect on cell surface proteins, as evidenced by the finding that carbamylation of erythrocyte membrane proteins in patients with ESKD was related to reduced membrane stability and premature erythrocyte degradation.21–23 Moreover, carbamylation of leukocyte proteins inhibited their ability to release microbicidal superoxide.24

Integrin αIIbβ3 is the major platelet membrane protein. The interaction of αIIbβ3 with von Willebrand factor (vWf) and fibrinogen is critical for platelet adhesion and aggregation.25 Uremic platelets revealed decreased binding of vWf and fibrinogen to αIIbβ3, which was neither restricted to a specific agonist nor related to αIIbβ3 expression levels.26 Therefore, the aggregation defect in uremia may be related to a functional defect in αIIbβ3 that affects the ability of the receptor to undergo the conformational change required for fibrinogen binding.7,8 The dialysis-associated improvements in αIIbβ3 function may explain the beneficial effects of HD on platelet aggregation.26 Thus, both uremic toxins and receptor occupancy by fibrinogen fragments likely contribute to the altered platelet reactivity in the uremic milieu.5,27

We hypothesized that platelet exposure to circulating urea-derived cyanate leads to carbamylation-triggered structural alterations of αIIbβ3 associated with a fibrinogen-binding defect contributing to impaired aggregation of uremic platelets. Therefore, in this study, we investigated whether carbamylation may form a mechanistic link between uremia and platelet dysfunction in ESKD. We especially focused on αIIbβ3 and the major human thrombin receptor, protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR-1), which controls one pathway of αIIbβ3 activation through inside-out signaling.28–30

Methods

Patients and Controls

The study included 27 patients with ESKD (15 men and 12 women, 27–82 years) receiving HD treatment two to four times weekly at Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway. The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (2013/2320/REK vest) approved collection of blood samples from the patients, and we obtained written informed consent from all participants before enrollment. We drew blood samples from the arterial needle or the outflow line of the dialysis catheter at the start of dialysis, collected in Vacuette ACD-A (acid citrate dextrose) tubes (Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC). From the 19 patients included in the aggregation experiments, seven were on acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) therapy (75 mg/d). Twelve patients did not receive any medication that affects platelet function (Supplemental Appendix).

We obtained control samples from blood donors at the blood bank (Department of Immunology and Transfusion Medicine, Haukeland University Hospital, Bergen, Norway). Control subjects had not taken any medication for at least 14 days before sampling.

Platelet Isolation and Carbamylation

We centrifuged blood samples for 20 minutes at 200 × g before collecting platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and diluting it with an equal volume of HEP buffer (140 mM sodium chloride [NaCl], 2.7 mM potassium chloride [KCl], 3.8 mM HEPES, 5 mM EDTA, 1 μM PGE1, pH 7.4). After centrifugation for 20 minutes at 100 × g to remove residual red and white blood cells, platelets were pelleted at 300 × g for 20 minutes and resuspended in platelet buffer (145 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 0.5 mM disodium phosphate, 6 mM glucose, pH 7.4). We performed all centrifugations at room temperature (RT). For experiments investigating activation-dependent responses, platelets were allowed to rest for 30–60 minutes at RT to ensure they were in the resting state.

We carbamylated platelets using the indicated concentrations of potassium cyanate (KOCN; Sigma-Aldrich, Oslo, Norway) for 30 minutes at 37°C. Control platelets were incubated in pure platelet buffer. To test whether free amino acids can protect platelets from carbamylation, we incubated platelets with KOCN in the presence of the amino acid infusions Glavamin or Vamin (Fresenius Kabi, Halden, Norway) diluted 1:4 in reaction buffer. We then centrifuged platelets at 300 × g for 5 minutes, resuspended them in binding buffer (140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM calcium chloride [CaCl2], 10 mM HEPES), and subjected them to subsequent analyses.

For platelet activation in plasma, we used PRP after removal of residual red and white blood cells. Plasma was diluted in a ratio of 1:1 with HEP buffer and carbamylated with 5 or 10 mM KOCN for 30 minutes at 37°C. After carbamylation, we adjusted the calcium concentration in plasma to 2.5 mM by using CaCl2.

Alternatively, for light transmission aggregometry (LTA) assays, we centrifuged blood for 20 minutes at 100 × g and RT to obtain PRP. PRP (600 μl) was centrifuged for 10 minutes at 3500 × g and RT to generate platelet-poor plasma (PPP), which was used as blank. PRP was carbamylated by incubation with 1, 5, or 10 mM KOCN for 30 minutes at 37°C. Control plasma was incubated with buffer. After carbamylation, we adjusted the calcium concentration in PRP to 2.5 mM CaCl2.

Platelet Protein Fractionation

Platelets were isolated from ACD-A tubes as described, frozen to −70°C, and, after addition of protease inhibitor (Complete Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Tablets; Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), thawed in a water bath at 37°C. We repeated freezing and thawing twice. Platelets were disrupted by sonication, centrifuged for 5 minutes at 4500 × g and 4°C, and the supernatants were collected. We then repeated the protein extraction and pooled the supernatants containing the cytosolic fraction. The pellets were washed once with cold platelet buffer and resuspended in 2 ml cold 100 mM sodium carbonate buffer, pH 11.5. Samples were transferred into small beakers, stirred on ice for 1 hour, and centrifuged for 1 hour at 47,800 × g and 4°C to obtain the peripheral membrane proteins (PMPs) in the supernatant. The pelleted integral membrane proteins (IMPs) were resuspended in NP-40 buffer (1% NP-40, 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA).

For biotin-PG labeling and the analysis of αIIbβ3 carbamylation, we pooled plasma from patients or controls, generating three patient and three control pools consisting of four to five individual samples each. We assigned patient samples to a pool according to their blood urea concentrations (lowest urea, P1; medium urea, P2; highest urea, P3; Table 1). Platelets were isolated from the pooled plasma samples and the platelet proteins fractionated as described above, with the difference that only the entire membrane proteins were separated from the cytosolic proteins but not PMPs and IMPs from each other. We solubilized membrane proteins in 100-mM sodium carbonate buffer, pH 11.5. We used the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) to determine protein concentrations in the individual fractions.

Table 1.

Urea concentration of patient platelet pools used in this study

| Pool Number | Urea Concentration, mM |

|---|---|

| 1 | 16.3 |

| 2 | 22.7 |

| 3 | 30.2 |

Quantification of HPLC-MS/MS

Platelet proteins of the cytosolic fraction were diluted to a concentration of 4 mg/ml in 150-mM NaCl, mixed 1:1 with 12-M hydrogen chloride, and incubated in glass tubes at 110°C for 18 hours. We evaporated hydrolysates twice to dryness under a stream of nitrogen. Dried samples were resuspended in 100 μl of 125-mM ammonium formate containing 1-μM d7-citrulline and 65-μM d8-lysine (internal standards) and filtered using Uptidisc PTFE filters (4 mm, 0.45 μm; Interchim, Mannheim, Germany). Diluted hydrolysates were subjected to HPLC-MS/MS analysis (API4000; ABSciex) using the same conditions as described in previous studies.31,32 We expressed HCit values relative to the lysine content in the hydrolysates.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blot of PMPs and IMPs

Proteins (2 μg) were mixed with 6× sample buffer and denatured for 10 minutes at 75°C. We loaded the complete sample volume (30 μl) into Novex 10% WedgeWell Tris Glycine Mini Gels (Life Technologies, Oslo, Norway) for separation via SDS-PAGE. We used Coomassie stain to visualize protein bands.

For Western blot, we transferred proteins onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad, Oslo, Norway) at 100 V and 4°C for 1 hour. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 for 1 hour, and primary antibodies were applied in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were sheep anti-human platelet αIIbβ3 (1:5000 vol/vol; Affinity Biologicals, Ancaster, ON, Canada) and rabbit anti-CBL (1:2500 vol/vol; Cell Biolabs, San Diego, CA). We then incubated the membranes with the horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies rabbit anti-sheep IgG (1:20000 vol/vol; Abcam) and mouse anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000 vol/vol; Jackson ImmunoResearch, Cambridge, United Kingdom), respectively, for 2 hours at RT. For development, Super Signal Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Oslo, Norway) was used, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and signals were recorded in a ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Bio-Rad).

Biotin-PG Labeling of Carbamylated Proteins

Biotin-PG labeling was performed as previously described.33 Samples (reaction volume 600 μl) were incubated with 20% (vol/vol) TCA and 0.2 mM biotin-PG for 30 minutes at 37°C. After a 30-minute incubation, we quenched the reaction with 150 μl of 0.1- M citrulline dissolved in 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.6). Proteins were precipitated by incubation on ice for 30 minutes and then centrifuged (13,500 rpm, 15 minutes) at 4°C. We discarded the supernatants, washed the protein pellets twice with cold acetone, and dried the pellets. The pellet was dissolved in a buffer containing 1% SDS, 7% β-mercaptoethanol, 20- mM HEPES (pH 8.0), 100- mM arginine, and 100- mM NaCl. We then boiled the sample for 10 minutes at 95°C and sonicated for 15 minutes twice to completely resolubilize the pellets. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (gradient 4%–12%; Bio-Rad) and transferred to membranes. The blots were blocked with 5% BSA in PBS with Tween 20 for 1 hour at RT and probed with sheep anti-human αIIbβ3 primary antibody diluted in 5% BSA overnight at 4°C. The blots were then washed with PBS with Tween 20 and probed with donkey anti-goat 680RD secondary antibody and streptavidin 800CW, as a surrogate antibody, diluted in 5% BSA for 1 hour at RT. The blots were further washed, and images were taken using a Licor Imager (700 nm and 800 nm). The band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software.

Platelet Adhesion Assay

Wells were coated with 100 μl human fibrinogen or albumin (2.5 mg/ml in 0.1 M carbonate buffer, pH 9.5) for 3 hours at 37°C. The coated plates were washed twice with 0.9% NaCl, 5×106 platelets in a volume of 100 μl platelet buffer were added to each well, and plates were incubated for 3 hours at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere. Plates were washed twice with PBS and adhered platelets fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde in PBS for 10 minutes at RT. Plates were washed twice with PBS and the cells stained with 0.5% crystal violet in distilled water for 10 minutes at RT. Plates were washed three times with distilled water and thoroughly drained on paper towels before 100 μl 1% SDS was added to each well. We measured absorbance at 570 nm on a Synergy H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Reader (Biotek, Bad Friedrichshall, Germany). Binding of platelets to albumin was used as a reference.

Platelet Aggregation Microplate Assay

We pipetted 5.6 μl pure platelet buffer (blank) or human thrombin (10 U/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) into the wells of a 96-well nonbinding microplate (Greiner Bio-One). A total of 3×107 carbamylated or control platelets in a volume of 145 μl platelet buffer were added to the wells, mixed with thrombin or buffer, and aggregation kinetics were recorded at 405 nm and 37°C for 30 minutes using continuous double orbital shaking. Light transmission was converted into percentage aggregation on the basis of the blank wells containing buffer instead of thrombin as 0% and pure buffer as 100% aggregation.

Light Transmission Aggregometry

LTA was performed in a Chrono-Log Model 700 Whole Blood Lumi-aggregometer (Chrono-Log Corporation, Havertown, PA). We prewarmed 240 μl washed platelets (1.8×108/ml) to 37°C in the aggregometer. After 3 minutes, we transferred the samples into the PRP positions of the aggregometer channels. A cuvette with 500 μl pure platelet buffer was placed as blank in the platelet-poor plasma position of channel 1, and the baseline in both channels was set to 0% aggregation. We then added 10 μl thrombin (10 U/ml) containing 2.5 mM CaCl2, and we recorded aggregation for 7 minutes at 37°C and 1000 rpm. We used AGGRO/LINK8 for Windows for measurements and slope calculations.

Flow Cytometry Aggregation Assay

Platelets were labeled with 0.25 μM CellTrace carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or 0.25 μM CellTrace Violet (Invitrogen) for 20 minutes at 37°C. Differently labeled platelets were mixed 1:1, activated with thrombin (0.4 U/ml), and incubated for 15 minutes at 14,000 rpm and 37°C on a thermomixer. We diluted samples with 400 μl PBS (100 mg/L Mg2+, 100 mg/L Ca2+) and evaluated aggregation on the basis of the increase in formation of double-colored events after platelet activation.

Assessment of αIIbβ3 and PAR-1 Activation by Flow Cytometry

Carbamylated and untreated or patient and control platelets (95 μl, 5 × 107 platelets/ml binding buffer) were activated with 0.4 U/ml human thrombin for 15 minutes at 37°C. We added 5 μl binding buffer to resting platelets. Alternatively, 95 μl control or carbamylated PRP was activated with 100 ng/ml convulxin (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan) for 15 minutes at 37°C.

Platelets were then stained with 20 μl FITC mouse anti-human PAC-1 antibody (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ), 10 μl Alexa Fluor 488 (AF488)–conjugated fibrinogen from human plasma (Thermo Fisher Scientific), or 20 μl PE-conjugated anti-human PAR-1 antibody (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) for 20 minutes at RT. To avoid fibrin polymerization, thrombin was inactivated with hirudin (3.125 U/U thrombin; Sarstedt, Nümbrecht, Germany) when binding of fibrinogen to activated αIIbβ3 was analyzed.

Samples were diluted with 400 μl PBS and αIIbβ3 activation was analyzed by measurement of antibody binding to resting and activated platelets by flow cytometry on a BD LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) equipped with BD FACSDiva software. Light scatter and fluorescence data were obtained with gain settings in logarithmic mode, and 50,000 events were acquired for each sample.

Preparation of DNA Constructs

The expression vectors encoding the sequence of human αIIb (pCMV6-A-Hygro-αIIb) and human β3 (pCMV6-Entry-β3) were purchased from OriGene Technologies GmbH (Herford, Germany). To obtain mutated αIIbβ3, five lysine residues located within the fibrinogen biding site of the β3 subunit were replaced by alanine (K163A, K170A, K185A, K207A, or K217A). Single mutations were introduced into the β3 sequence using the QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit and two specific overlapping oligonucleotide primers incorporating two base pair substitutions (Table 2). An expression vector containing all five mutations in the β3 sequence was generated using the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-Directed Kit (Stratagene; Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA) and all oligonucleotide primer pairs. All generated vectors were sequenced (Eurofins Genomics, Ebersberg, Germany) and used for transfection of human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA).

Table 2.

Oligonucleotides used for site-directed mutagenesis with two base pair substitutions marked

| Mutation Site | Oligonucleotide Primer Sequence |

|---|---|

| K163A | 5′-CCAGAACCTGGGTACCGCGCTGGCCACCCAGATGC-3′ |

| 5′-GCATCTGGGTGGCCAGCGCGGTACCCAGGTTCTGG-3′ | |

| K170A | 5′-CCACCCAGATGCGAGCGCTCACCAGTAACCTGC-3′ |

| 5′-GCAGGTTACTGGTGAGCGCTCGCATCTGGGTGG-3′ | |

| K185A | 5′-GGGCATTTGTGGACGCGCCTGTGTCACCATACATG-3′ |

| 5′-CATGTATGGTGACACAGGCGCGTCCACAAATGCCC-3′ | |

| K207A | 5′-CCCCTGCTATGATATGGCGACCACCTGCTTGCC-3′ |

| 5′-GGCAAGCAGGTGGTCGCCATATCATAGCAGGGG-3′ | |

| K217A | 5′-GCCCATGTTTGGCTACGCACACGTGCTGACGC-3′ |

| 5′-GCGTCAGCACGTGTGCGTAGCCAAACATGGGC-3′ |

Transfection of HEK293 Cells with αIIbβ3 Sequences

We maintained the HEK293 cells in high glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. To obtain HEK293 cells with transient expression of wild-type and mutated αIIbβ3 complexes, the expression vector encoding the αIIb sequence (pCMV6-A-Hygro-αIIb) was cotransfected with the expression vector encoding the wild-type β3 sequence (pCMV6-Entry- β3_WT) or mutated β3 cDNAs (pCMV6-Entry- β3_K→A) using the FuGene HD transfection reagent according to the manufacturer’s instruction (Promega, Madison, WI). Cells transiently expressing αIIbβ3 were analyzed 2 days after transfection.

αIIbβ3 Activation and Fibrinogen Binding in HEK293 Cells

HEK293 cells transiently expressing wild-type and mutated αIIbβ3 complexes were harvested with 2 mM EDTA in PBS and washed with PBS containing 2.5 mM CaCl2. To assess αIIbβ3 activation and fibrinogen binding, HEK293 cells were incubated with 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT) in PBS containing 2.5 mM CaCl2 for 20 minutes at 4°C. The high-affinity state of αIIbβ3 complexes was assessed by staining with FITC-conjugated anti–PAC-1 antibodies (BD Biosciences) for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark. Fibrinogen binding was assessed by incubation of cells in activation buffer supplemented with 2% BSA followed by staining with 50 μg/ml AF488-conjugated fibrinogen from human plasma (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After staining, all samples were centrifuged, diluted in PBS containing 2.5 mM CaCl2, and subjected to flow cytometric analysis using a BD LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences). Quantitative analysis of αIIbβ3 activation and fibrinogen binding was determined by measuring the percentage of FITC- or AF488-positive, PI-negative cells out of 10,000 events. We used nontransfected HEK293 cells as a negative control.

αIIb and β3 Surface Expression in HEK293 Cells Followed by Cell Surface Biotinylation

HEK293 cells transiently expressing wild-type and mutated αIIbβ3 complexes were washed with cold PBS and treated with 0.1 mg/ml EZ-link Sulfo-NHS-LC-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 hour at 4°C. Cells were washed twice with PBS containing 100 mM glycine, lysed with 300 μl RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) containing Complete EDTA-Free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) and 2.5 mM EDTA, and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C. We used the Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit to determine the protein concentration of the lysate. A total of 200–250 μg was loaded onto streptavidin magnetic beads (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL) and incubated overnight at 4°C. After incubation, we washed the beads three times in RIPA buffer and suspended them in 4× reducing sample buffer diluted in RIPA buffer to a final volume of 60 μl. Samples were boiled at 95°C for 5 minutes, resolved on SDS-PAGE, and electrotransferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was subsequently blocked and then probed with primary anti-αIIb and anti-β3 (Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN) in 5% skim milk overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed three times with TTBS and incubated with secondary horseradish peroxidase–conjugated antibodies for 1 hour at RT. The membrane was developed with ECL Western Blotting Substrate and the signal was detected with ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

Clot Retraction Assay

Blood was centrifuged for 20 minutes at 100 × g and RT to obtain PRP. We rested the PRP for 30 minutes in a warm water bath (30°C–35°C). Glass tubes were filled with 745 μl prewarmed Tyrode-HEPES buffer (134 mM NaCl, 0.34 mM disodium phosphate, 2.9 mM KCl, 12 mM sodium bicarbonate, 20 mM HEPES, 5 mM glucose, 1 mM magnesium chloride, pH 7.3), and 5 μl red blood cells (from the bottom layer of the tubes after centrifugation) and mixed. To each sample, 200 μl PRP and 2 μl KOCN (2.5 or 5 M) were added, and the samples were sealed with parafilm and then incubated for 30 minutes at 37°C. After carbamylation, 50 μl thrombin (10 U/ml) was added to initiate coagulation, and the samples were sealed again with parafilm. The samples were left undisturbed at RT for the duration of the experiment.

For the assessment of clot retraction, pictures were taken at the start of the experiment and then every 30 minutes from the time the first signs of clot retraction were observed. After complete retraction in the control sample, we determined the weight of the clots.

Statistical Analysis of αIIbβ3 Carbamylation

The plasma (healthy donors [n=12] and patients on HD [n=14]) samples were pooled together according to the blood urea concentrations of the patients to generate three representative samples (four to five donors per pool; Supplemental Table 1). The labeling experiments were performed with the platelet membrane proteins isolated from these samples in a blinded fashion with three technical replicates. We used ImageJ software to quantify and average the band intensities in the blots. The relative levels of carbamylation of the αIIb and β3 subunits were calculated by dividing the band intensities of the carbamylated fractions by that of the total input of the respective receptor bands. The relative levels of carbamylated αIIbβ3 in healthy control and patient on HD samples were plotted as the average of the three individual patient and control pools. The error bars represent SEM.

Statistical Analysis

Flow cytometry data analysis and preparation of figures was performed in FlowJo version 10.4.1 for macOS. Group means were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test or ANOVA. Correlations between fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 and aggregation were assessed by determining Spearman rank correlation coefficients. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism, version 7.0 for Mac, with P <0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Carbamylation Inhibits Platelet Adhesion and Aggregation by β3 Modification

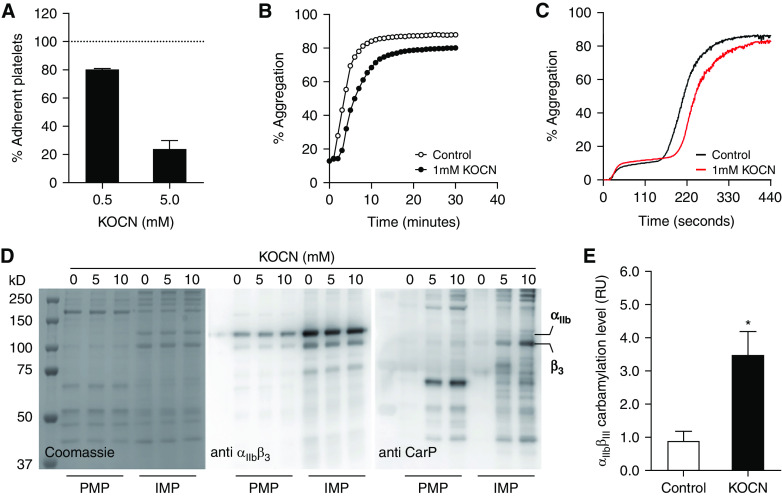

Testing the effect of carbamylation on αIIbβ3-mediated platelet functions, we found that brief exposure of platelets to cyanate significantly reduced adhesion to fibrinogen in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A). Carbamylation also altered the kinetics of thrombin-induced platelet aggregation (Figure 1, B and C). Platelet carbamylation was associated with a prolonged lag phase and reduced total aggregation. Carbamylation of the β3 subunit of αIIbβ3 that contains two fibrinogen-binding domains (Figure 1, D and E) supports our hypothesis that carbamylation impairs platelet adhesion and aggregation by inducing structural modifications in αIIbβ3 that interfere with ligand binding.

Figure 1.

β3 Carbamylation inhibits platelet adhesion and aggregation. Platelets were carbamylated in 0.5 or 5 mM KOCN for 30 minutes at 37°C, and adhesion to fibrinogen-coated microtiter plates was analyzed by measuring the absorbance at 450 nm after crystal violet staining. (A). Results are illustrated as percentage of adherent platelets normalized to the untreated control, which is represented by the horizontal line. Results show the average±SEM of two experiments, each including 24 wells per condition. Untreated and carbamylated (1- mM KOCN) platelets were activated with 5 nM thrombin, and aggregation kinetics were followed for 30 minutes on (B) a microplate reader or (C) for 7 minutes in a light transmission aggregometer. Curves represent the mean of three independent experiments. Total platelet proteins were isolated from untreated and carbamylated (5 and 10- mM KOCN) platelets and fractionated by differential centrifugation. PMP and IMP fractions were separated into individual proteins by SDS-PAGE (left). (D) Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and αIIbβ3 (middle) and carbamylated epitopes (CarP; right) were visualized by immunostaining. Membrane proteins from untreated and carbamylated (1-mM KOCN) platelets were labeled with biotin-PG, separated by SDS-page, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes by electroblotting. αIIbβ3 was detected by using a protein-specific primary antibody and a fluorescent secondary antibody; biotin-labeled carbamylated residues were visualized by using streptavidin 800CW. (E) Relative levels of αIIbβ3 carbamylation were obtained by dividing the streptavidin 800CW signal that overlaps with the receptor band by the signal corresponding to the complete receptor protein. The graph represents the average of two membranes each containing three technical replicates. Comparison was done by a paired t test. *P≤0.05. (A, B, C, and E) Graphs of the individual biological replicates are found in Supplemental Figure 4.

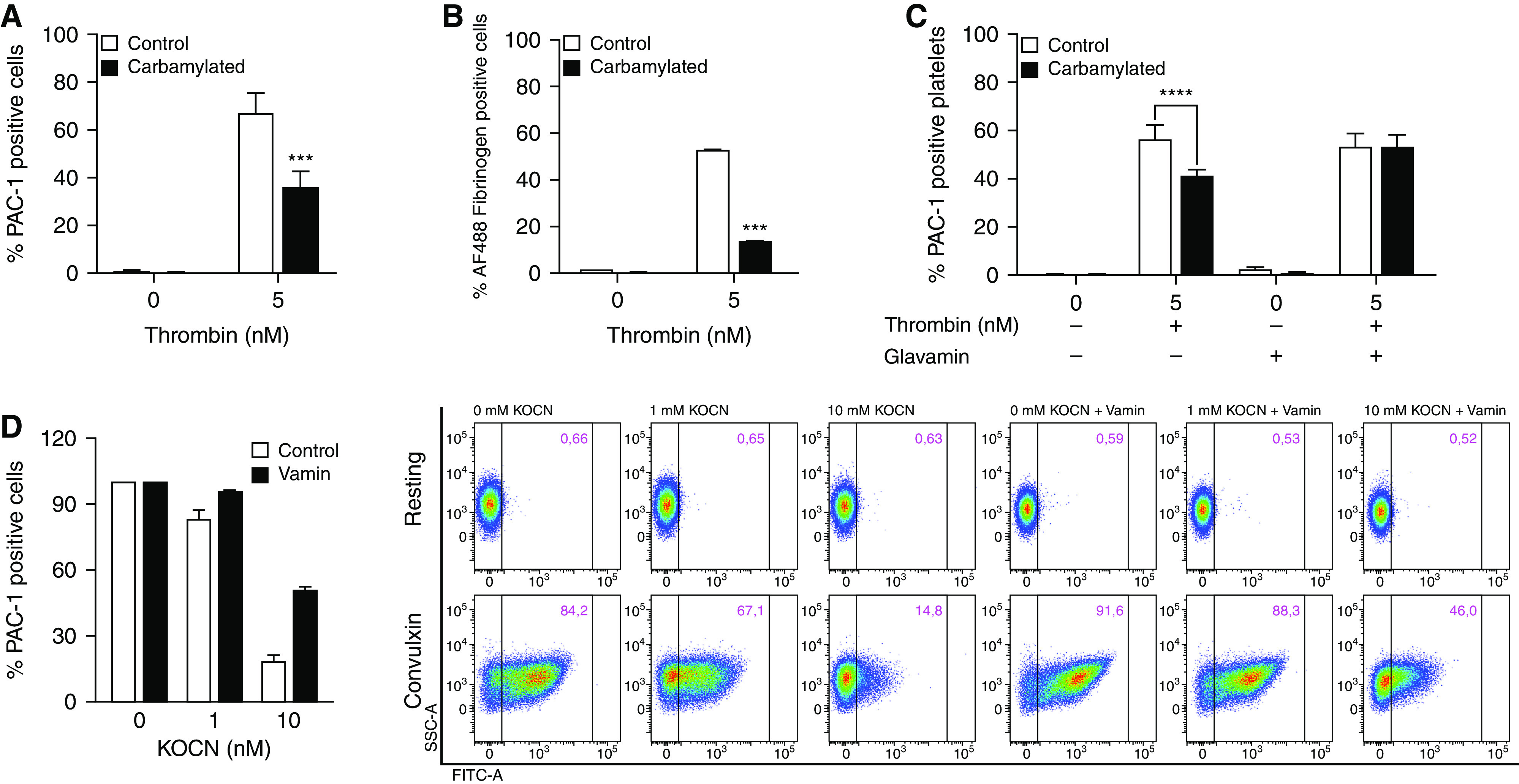

Platelet Carbamylation Inhibits αIIbβ3 Activation

The interaction of αIIbβ3 with fibrinogen is a complex process depending on the conformational states of both proteins.34 The αIIbβ3 fibrinogen-binding site contains five lysine residues located in the β3 subunit.35,36 Thus, carbamylation of these residues may impair conformational changes and/or alter the fibrinogen-binding capacity of αIIbβ3 and thereby contribute to reduced platelet adhesion and aggregation. We assessed the effect of carbamylation on platelet activation by measuring PAC-1 and fibrinogen binding to carbamylated and control platelets by flow cytometry. PAC-1 antibodies bind in proximity to a fibrinogen-binding site on β3 of the activated receptor only, thus allowing determination of the high-affinity state of the integrin.36 The population of PAC-1–binding platelets was significantly smaller after carbamylation compared with control platelets (Figure 2A). This result was confirmed using AF488-labeled fibrinogen to determine the proportion of activated platelets (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Platelet carbamylation inhibits αIIbβ3 activation in response to thrombin, and convulxin. (A–C) Carbamylated and control platelets were left in the resting state or activated with 5 nM thrombin, or (D) 100 ng/ml convulxin for 15 minutes at 37°C. (A, C, and D) αIIbβ3 activation was analyzed by flow cytometry using an anti–PAC-1 antibody, which binds to the activated receptor only or (B) AF488 fibrinogen, a labeled form of the endogenous αIIbβ3 ligand. Percentages of activated platelets were compared using two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post-test. ***P≤0.001. Platelets were carbamylated in the presence or absence of free amino acids, as described, and activated with thrombin (C) or convulxin (D). αIIbβ3 activation was assessed by flow cytometry measurements of anti–PAC-1 antibody binding. For convulxin, flow data are shown from one representative experiment (n=3). αIIbβ3 activation under the different conditions was compared using two-way ANOVA. ****P≤0.0001. Figures show the average of three (A and C) or two (D) biologic replicates. Figure 1B shows one representative experiment performed in triplicates. (A, C, and D) Graphs of the individual biological replicates are found in Supplemental Figure 5.

Due to the high reactivity of N-terminal amino groups with cyanate, free amino acids act as competitive inhibitors of protein carbamylation.37 Carbamylation-induced loss of αIIbβ3 activity was completely reversed in the presence of Glavamin, an amino acid solution administered to prevent protein malnutrition (Figure 2C). This further indicates that carbamylation may contribute to impaired αIIbβ3 function.

To investigate the effect of cyanate on platelets in plasma, PRP was carbamylated and platelet activation by the GpVI agonist convulxin was analyzed using PAC-1 antibodies. As shown for isolated platelets, the population of PAC-1–positive platelets in plasma was significantly smaller after carbamylation compared with control plasma. Carbamylation of plasma in presence of free amino acids prevented carbamylation-induced loss of αIIbβ3 activity (Figure 2D). PRP did not contain other blood cells (data not shown).

Platelet Carbamylation Does Not Affect PAR-1 Cleavage and α-Granule Secretion

Because impaired PAR-1 cleavage may contribute to decreased αIIbβ3 activity after platelet carbamylation, PAR-1 cleavage was investigated using a cleavage-sensitive antibody that exclusively recognizes the intact receptor. Equal amounts of antibody were bound to carbamylated and control platelets in the resting state. After activation with thrombin, antibody binding to both carbamylated and control samples was almost completely abolished, providing evidence that PAR-1 activation is not affected by carbamylation (Supplemental Figure 1A). These results were confirmed in platelets isolated from patients on HD and controls, where no differences in PAR-1 cleavage were observed (Supplemental Figure 1B). Moreover, carbamylation had no effect on the number of P-selectin and CD40L-positive platelets after activation, suggesting carbamylation has no effect on α-granule secretion (Supplemental Figure 1, C and D).

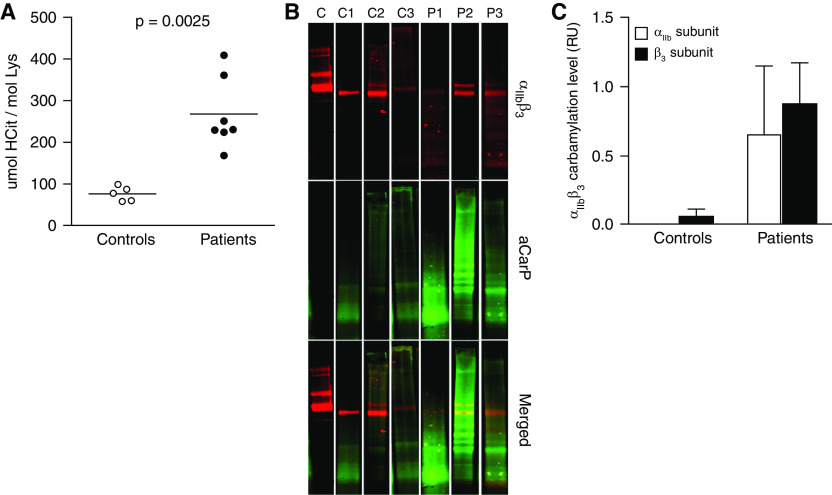

αIIbβ3 Is Carbamylated in Platelets from Patients on Chronic HD

To validate our in vitro findings, HCit levels in platelet proteins from patients on HD and controls were analyzed. The amount of HCit residues was around three-fold higher in platelets from patients on HD compared with controls (Figure 3A). Although the above approach confirmed significant carbamylation of platelet proteins, it did not provide specific information about αIIbβ3 carbamylation. Therefore, we used a HCit-specific biotin-PG probe to determine the relative level of carbamylated αIIbβ3 in platelet membrane proteins from patients on HD and controls. To minimize sample heterogeneity and improve the detection limit, plasma samples were pooled before platelet protein fractionation, generating three patient (P1–P3) and three control pools (C1–C3). All patient pools showed significantly higher band intensity for the carbamylation staining than the control pools, confirming αIIbβ3 is carbamylated in platelets from patients on HD. Carbamylated αIIb could not be detected in any of the control pools, and a detectable amount of carbamylated β3 was only observed in C3. Overall, the analysis of the clinical samples confirmed carbamylation of the αIIbβ3 complex in patients on HD, with only minor αIIbβ3 modification in healthy controls (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

αIIbβ3 is carbamylated in platelets from patients on chronic HD. (A) Proteins were isolated from uremic and control platelets, and the HCit content in the protein preparations was quantified by HPLC-MS/MS. Carbamylation levels in platelet preparations from patients and controls were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. Blood samples from patients with ESKD and control subjects were pooled (samples from four to five individuals per pool) before platelet membrane proteins were isolated by differential centrifugation. Membrane proteins were labeled using biotin-PG, separated by SDS-page, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes by electroblotting. (B) αIIbβ3 was detected using a protein-specific primary antibody and a fluorescent secondary antibody (top panel). Biotin-labeled carbamylated residues were visualized by using streptavidin 800CW (middle panel), and fluorescence signals were quantified in the overlapping regions (bottom panel). (C) Relative αIIbβ3 carbamylation was quantified in the control and patient pools and is shown as the mean of the three control and three patient pools. Only one out of three technical replicates is shown (B). C, purified αIIbβ3 protein, C1–C3, control pools; P1–P3, patient pools; aCarP, antobody against carbamylated proteins.

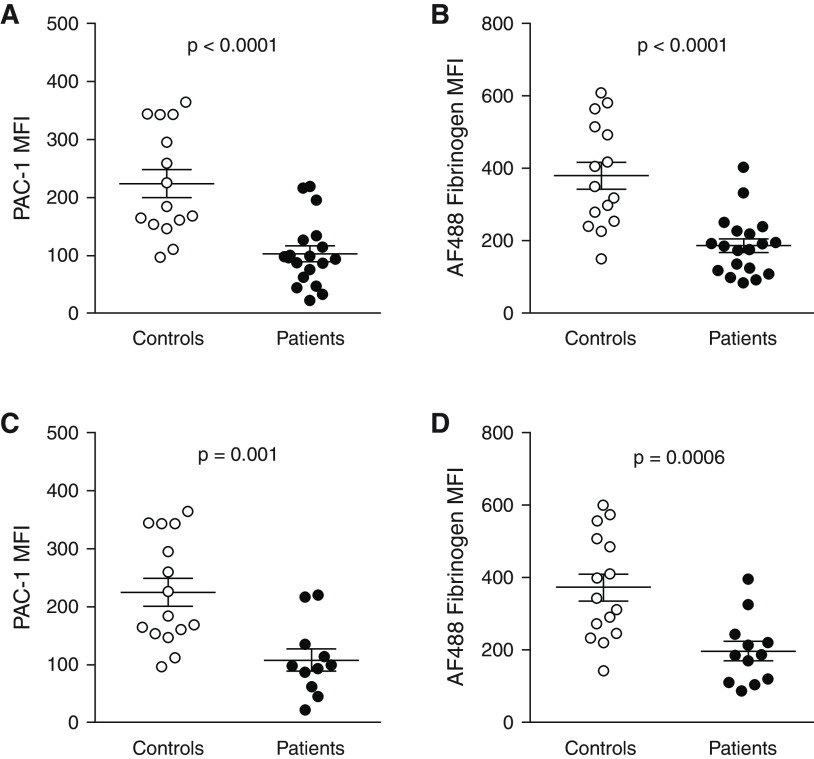

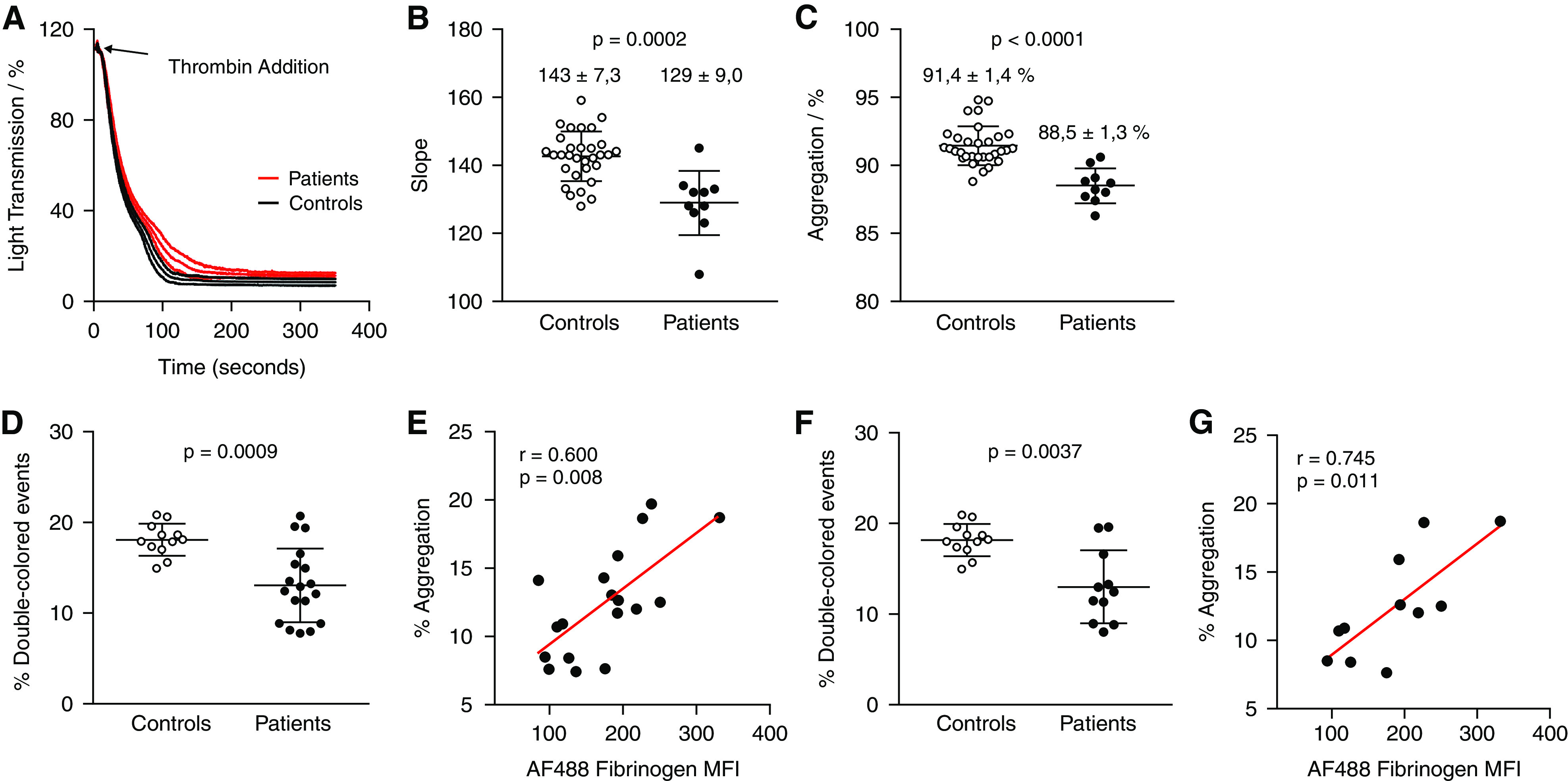

Carbamylation of αIIbβ3 Is Linked to Uremic Platelet Dysfunction

To test functional effects of αIIbβ3 carbamylation, we assessed conversion of the receptor to the active conformation by flow cytometry. Thrombin-induced αIIbβ3 activation was significantly reduced in platelets from patients on HD compared with healthy donors, as illustrated by reduced binding of PAC-1 and AF488 fibrinogen (Figure 4, A and B). These results agree with our in vitro findings, suggesting carbamylation of αIIbβ3 is one of the mechanisms underlying uremic bleeding. Excluding patients receiving antiplatelet therapy did not alter overall results (Figure 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

Carbamylation contributes to platelet dysfunction in ESKD. Patient (n=18 in [A], n=19 in [B]) and control (n=15) platelets were activated with 5 nM thrombin for 15 minutes at 37°C, and activation of αIIbβ3 was assessed by flow cytometry as (A, C) binding of anti–PAC-1 antibody or (B, D) AF488 fibrinogen. The results were analyzed in all patients (A, B) and in the subgroup of patients not on regular antiplatelet therapy (n=11 in [C], n=12 in [D]). αIIbβ3 activation between patients and controls was compared using the Mann–Whitney U test. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Uremic Platelets Show a Reduced Aggregation Response That Correlates with Fibrinogen Binding to αIIbβ3

Significantly reduced activation of αIIbβ3 in uremic platelets suggested that platelet aggregation may also be affected. Aggregation curves were recorded to determine reaction rate (slope) and maximum percentage of aggregation of platelets from patients on HD. Platelets from 31 healthy volunteers were analyzed to define a reference range. Compared with controls, aggregation of uremic platelets was characterized by a lower gradient slope (Figure 5, A and B) and a lower maximum aggregation percentage (Figure 5, A and C). To confirm these findings, platelet aggregation was assessed by flow cytometry, detecting the percentage of platelet aggregates after activation with thrombin.38 In agreement with the LTA results, the aggregability of uremic platelets was lower than that of control platelets (Figure 5D). Interestingly, we found a strong correlation between the percentage of platelet aggregates and the fibrinogen-binding capacity of αIIbβ3 on platelets from patients on HD (Figure 5E). The difference in percent aggregation, and the correlation between fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3 and aggregate formation, remained statistically significant after excluding the patients on antiplatelet therapy (Figure 5, F and G).

Figure 5.

Aggregation kinetics in response to thrombin differ in uremic and control platelets. Platelets isolated from patients on HD (n=10) were activated with 5 nM thrombin in the absence of exogenous fibrinogen, and the course of aggregation was recorded for 7 minutes by LTA. (A) Additionally, a standard aggregation curve, on the basis of the analysis of platelet samples from 31 healthy controls is shown. (B) Numerical values of the slope, a measure of the reaction rate, and (C) the percentage of aggregation, an indicator of platelet aggregability obtained from the individual aggregation curves of uremic and control platelets. CellTrace carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester– and CellTrace Violet–labeled uremic platelets (n=18) and control platelets (n=12) were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and activated with 5 nM thrombin at 37°C and 14,000 rpm for 15 minutes. (D) Aggregation was measured as the percentage of double-colored events by flow cytometry. (E) Spearman rank correlation between the percentage of aggregates formed after 15 minutes and the fibrinogen-binding capacity of αIIbβ3. (F, G) Data were analyzed separately for the subgroup of patients not on regular antiplatelet therapy (n=11). (B, C, D, F) Differences between patients and controls were tested using the Mann–Whitney U test. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Carbamylation Has No Effect on GpIb Function

To investigate the effect of carbamylation on other glycoprotein receptors, GpIb-mediated platelet agglutination was analyzed after activation of platelets with Ristocetin. GpIb is the second most abundant glycoprotein on the platelet surface and is critically involved in platelet adhesion to the subendothelium via binding to vWf. Carbamylation of platelets using different concentrations of cyanate had no effect on Ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination (Supplemental Figure 2). Using isolated platelets instead of PRP yielded the same result (data not shown).

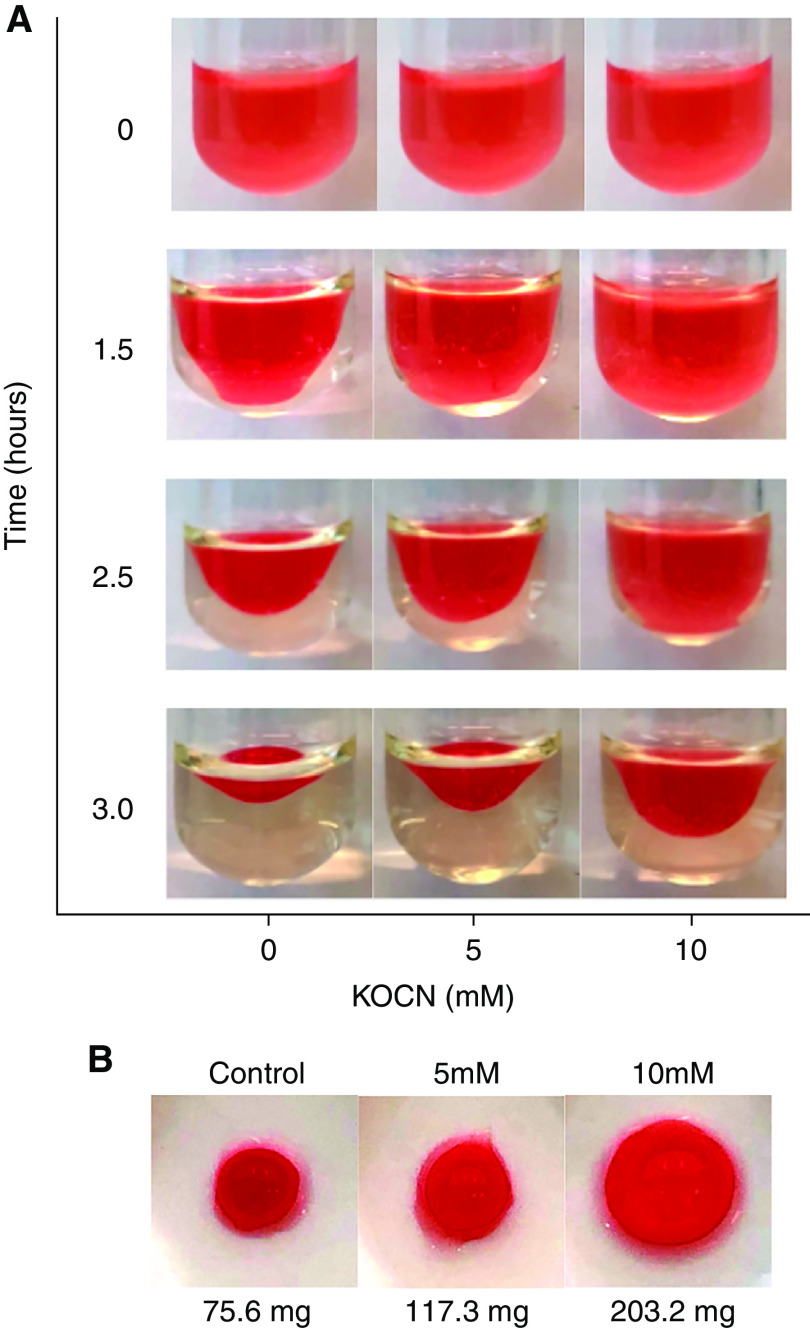

Carbamylation Increases Clot Retraction Time

Clot retraction is the process in which regression in size of a blood clot brings the edges of the endothelium closer together to repair the damage. Our results clearly show the clot retraction time increases with increased degree of carbamylation (Figure 6). Because clot retraction is driven by αIIbβ3, increased retraction time after platelet carbamylation may also be a result of αIIbβ3 dysfunction.

Figure 6.

Carbamylation increases clot retraction time. Tyrode–HEPES buffer was mixed with red blood cells and PRP, and the mixture was carbamylated using 5 and 10 mM KOCN for 30 minutes at 37°C. The control sample was incubated without KOCN. Coagulation was initiated by addition of 10 U/ml thrombin. The samples were sealed with parafilm and left undisturbed at RT for 3 hours. (A) Pictures of the retracting clots were taken at the start of the experiment and then every 30 minutes until complete retraction in the control sample was obtained. (B) At the end of the experiment the mass of the clots was determined.

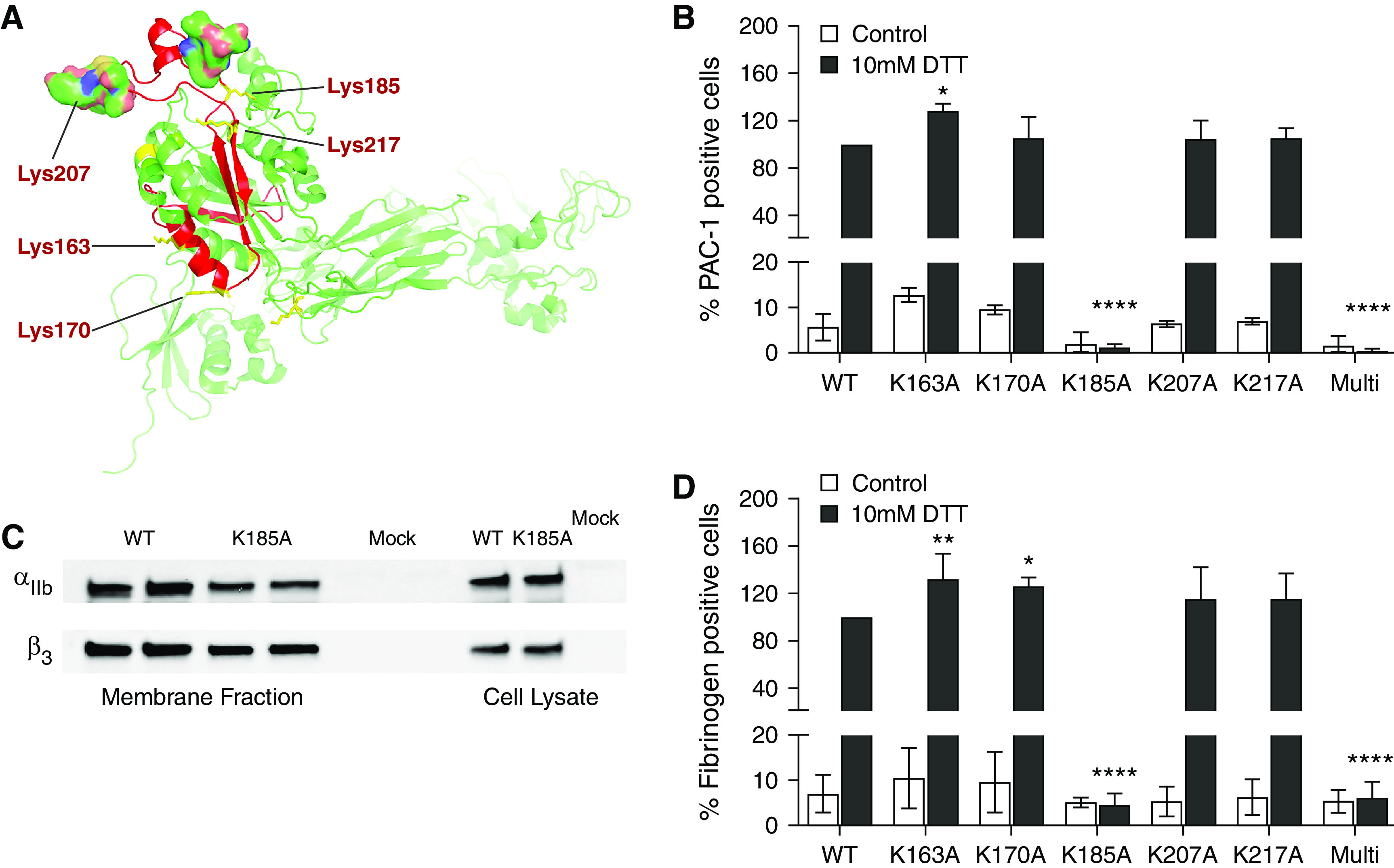

Modification of K185 in the αIIbβ3 Subunit Prohibits Receptor Activation and Fibrinogen Binding

To identify carbamylation sites responsible for the loss of αIIbβ3 activity, we performed in vitro mutagenesis studies. On the basis of current knowledge, and our finding that mainly the β3 subunit was carbamylated, we predicted in silico five lysine residues located within the fibrinogen binding sites as potentially the most susceptible for carbamylation (two in the 7E3 epitope binding site [K163 and K170] and three in the positively charged surface cleft [K185, K207, and K217]) (Figure 7A).35,36 To simulate the effect of carbamylation on the activity of αIIbβ3, an in vitro system was created using HEK293 cells transiently expressing the wild-type and mutated αIIbβ3 receptor variants in which the lysine residue of interest was replaced with neutral alanine, mimicking the loss of charge upon carbamylation. Activation of the fibrinogen receptor was assessed by flow cytometry using activation-dependent PAC-1 antibodies. Upon activation of wild-type αIIbβ3 with 10 mM DTT, the population of PAC-1–positive cells increased ten-fold (Figure 7, B and D). After treatment of HEK293 cells with KOCN, we noted a specific and concentration-dependent loss in αIIbβ3 activity, confirming the effect of carbamylation on fibrinogen receptor function in platelets and patients with ESKD (Supplemental Figure 3). Interestingly, the activation of αIIbβ3 was not affected by mutation of K165A, K170A, K207A, and K217A. In contrast, HEK293 cells transfected with the αIIbβ3_K185A variant had a very low level of active αIIbβ3 in the resting state (0.2% as compared with 2% PAC-1–positive cells in the wild type) and did not show any binding of PAC-1 antibodies after activation (Figure 7B). Similar results have been obtained for binding of human fibrinogen to HEK293 cells expressing all αIIbβ3 variants (Figure 7D). Using Western blot, we confirmed the αIIb and β3 subunits of the K185A variant were present on the cell membrane (Figure 7C). Interestingly, αIIbβ3 with all five mutations showed similar results for both PAC-1 and fibrinogen binding as the αIIbβ3_K185A variant (Figure 7, B and D). This confirms that the replacement of positively charged lysine by neutral alanine, specifically in position 185, affects the receptor’s ability to undergo the conformational changes required to reach the high-affinity state, bind fibrinogen, and exert downstream functions.

Figure 7.

The lysine residue in position 185 in the β3 binding site is pivotal for activation and fibrinogen binding of αIIbβ3 in HEK293 cells. (A) In silico three-dimensional model presenting the fibrinogen binding pocket of β3 with lysine residues selected as potential targets for carbamylation. The three-dimensional structure of β3 was prepared in the PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with wild-type (WT) and six mutated αIIbβ3 complexes (K163A, K170A, K185A, K207A, K217A, and a multimutant with all five mutations). Cells were activated with 10 mM DTT for 20 minutes at 4°C. (B) Activation and (D) fibrinogen binding was analyzed by flow cytometry using an activation-dependent anti–PAC-1 antibody and AF488 fibrinogen, respectively. (C) Surface expression of both subunits in cells expressing the αIIbβ3_K185A variant in comparison to cells expressing the wild-type receptor and nontransfected cells (mock) was confirmed by biotinylation of surface proteins followed by streptavidin bead immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting. Data are representative of three independent experiments (B, C, D). Percentages of activated cells (B, D) were compared using two-way ANOVA with follow-up Bonferroni multiple comparison test. *P≤0.05, **P≤0.01, ****P≤0.0001.

Discussion

Carbamylation of plasma proteins is extensively studied and has received much attention in the past due to the discovery of its association with serious complications of ESKD and with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in patients on HD.17,39 Average cyanate concentrations in the circulation of patients with ESKD were shown to be 0.6 mM, but cyanate concentrations of up to 1 mM are reported in the literature.40,41 These values are, however, an underestimation due to the high reactivity and, therefore, short halflife of cyanate, which has been shown to modify a number of plasma, cell surface, and even intracellular proteins. To date, most studies investigating carbamylation-induced alterations of cell functions were performed using erythrocytes and renal or endothelial cells, with less focus on other cell types.18,20,21,42

Platelets are the second most abundant blood cells after erythrocytes. Almost all of their functions, including the regulation of hemostasis, depend on surface receptors, which are easily accessible for modification by circulating cyanate throughout their life span of 7–9 days. Such conditions cannot be fully replicated in the laboratory because purified platelets continue to be metabolically active at RT. Products of metabolism, such as lactate, accumulate, severely diminishing their function and survival.43 Therefore, to achieve a rate of carbamylation corresponding to in vivo conditions in patients with ESKD, while not compromising platelet quality in in vitro experiments, we have used cyanate concentrations between 0.5 and 10 mM for 30 minutes.

In this study, we show that αIIbβ3 carbamylation is associated with reduced integrin activation and fibrinogen-binding capacity, leading to impaired platelet adhesion to fibrinogen and impaired platelet aggregation. We provide evidence that modification of the lysine residue in position 185 in the β3 subunit may prevent the conformational change of αIIbβ3 to the activated form and could, therefore, be a mechanistic link between uremia and bleeding diatheses in patients on dialysis.

Moreover, inhibition of αIIbβ3 activation after carbamylation was significant, regardless of whether the experiment was performed with PRP or isolated platelets and regardless of whether a PAR-1 agonist (thrombin) or a GpVI agonist (convulxin) was used for platelet activation.

Thrombin activates platelets via the PAR-1 pathway with minor contribution by PAR-4.44 Using flow cytometry, we demonstrated carbamylation had no effect on anti–PAR-1 antibody binding to resting or activated platelets, ruling out the possibility that carbamylation affects αIIbβ3 activation by interfering with PAR-1 cleavage. Unlike the ligand-binding domains of αIIbβ3, the cleavage site of PAR-1 does not contain lysine residues, minimizing the effect of carbamylation on receptor function. Because the leucine and proline residues of both PAR-1 and PAR-4 are regarded as responsible for the formation of the three-dimensional structures recognized by thrombin, it is likely that PAR-4 function is also preserved after exposure to cyanate.45

Both CD62P and CD40L are located in α-granules of quiescent platelets, but they translocate to the plasma membrane upon platelet activation, allowing their use as platelet-bound markers of α-granule secretion.46 We found carbamylation had no effect on the translocation of CD62P and CD40L. Because α-granules also contain a storage pool of αIIbβ3, normal degranulation indicates reduced fibrinogen binding by carbamylated platelets results from impaired activation and not from lower receptor expression on the platelet surface.47

Carbamylation had no effect on GpIb function because Ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination after exposure of platelets to cyanate was not different from control platelets. Collectively, these results support the assumption that carbamylation affects predominantly αIIbβ3 activation and, to a lesser extent, the function of agonist receptors or the integrity of intracellular signaling cascades. However, we cannot exclude that carbamylation of other proteins also contributes to platelet dysfunction. Carbamylation has been previously reported to affect fibrinogen function and fibrin clot formation.31,48 Both surface and intracellular proteins are susceptible to cyanate-driven modification, which could result in impaired integrin activation, clustering, or focal adhesion.49 A prime candidate for this effect is the cytoskeletal protein talin, which interacts through the poly-lysine tail of its C-terminal domain with the cytoplasmic tail of integrin β3.50,51

Importantly, our in vitro observations seem to reflect the situation in patients on HD, suggesting the potential role of carbamylation in platelet dysfunctions in ESKD. LC-MS/MS analyses of protein preparations showed the level of protein carbamylation was significantly higher in platelets from patients on HD than from controls, confirming platelet carbamylation in vivo in a high urea environment. Surface proteins are most susceptible to carbamylation and, because αIIbβ3 is the most abundant platelet surface protein, we hypothesized a significant proportion of the detected HCit residues derive from carbamylated αIIbβ3. Using a HCit-reactive biotin-PG probe in combination with a αIIbβ3-specific antibody, we successfully confirmed a high level of modification present on both subunits of the αIIbβ3 complex in the platelets of patients on HD, which was absent in control platelets. Interestingly, the highest level of carbamylated αIIbβ3 was detected in the medium urea pool (P2), despite a clear correlation of blood urea concentration and total protein carbamylation in plasma. The anti-αIIbβ3 staining showed several lower molecular weight bands in the lane corresponding to the high urea sample. This pattern may indicate receptor degradation and could explain a loss of the carbamylation signal, which was only evaluated in the region of the expected receptor bands (125 and 100 kD).

Receptor activation in uremic and control platelets further underlines that carbamylation is involved in the dysfunction of uremic platelets. αIIbβ3 Activation, as indicated by PAC-1 and fibrinogen binding, was significantly lower in platelets from patients on HD, whereas there was no difference in PAR-1 cleavage between patients and controls. This finding is consistent with the results of a previous study reporting reduced αIIbβ3 activity in patients on HD with equal receptor surface expression.26

Functional defects of in vitro carbamylated and uremic platelets resemble the clinical picture of Glanzmann thrombasthenia, a genetic disorder in which mutations in genes encoding integrin αIIbβ3 lead to the expression of low levels or a defective protein. Although it remains speculative, such similarity supports our hypothesis that carbamylation-induced damage of αIIbβ3 significantly contributes to uremic platelet dysfunction.52

A pilot study reported intravenous amino acid supplementation effectively reduced the carbamylation level of plasma proteins, as represented by the percentage of carbamylated albumin in patients on dialysis.37 Cyanate preferentially targets free amino acids, due to its high affinity for primary amino groups, thereby protecting the side chain amino groups of lysine in proteins from carbamylation-induced damage.15,53 We found that the amino acid infusions Glavamin and Vamin prevented carbamylation-induced loss of αIIbβ3 function, strengthening our hypothesis that αIIbβ3 carbamylation contributes to reduced receptor activation in the uremic milieu. Hence, regular supplementation with free amino acids may also have a beneficial effect on ESKD-associated complications, such as platelet dysfunctions.

The functional outcome of αIIbβ3 activation is the attainment of the high-affinity state of the receptor, enabling fibrinogen binding and the formation of platelet aggregates. Therefore, reduced receptor activation results in impaired aggregation. Our aggregation curves confirmed this by showing that the aggregation of uremic platelets was slower than the aggregation of control platelets. Additionally, flow cytometry showed the percentage of platelet aggregates directly correlated with the level of fibrinogen binding to αIIbβ3, providing further evidence that receptor carbamylation associated with a reduced fibrinogen-binding capacity can be involved in aggregation defects seen in uremic platelets.

Clot retraction is a process driven by αIIbβ3 and describes the regression in size of a blood clot, bringing the edges of the endothelium closer together to repair the damage. Our observation that carbamylation leads to increased clot retraction time supports the hypothesis that carbamylation of αIIbβ3 affects receptor activation, fibrinogen binding, and downstream functions of αIIbβ3 that are mediated by “outside-in” signaling.54

Seven patients on HD participating in this study were being treated with a daily dose of 75 mg ASA, which inhibits platelet aggregation.55 Exclusion of this group from the statistical analysis revealed that reduced αIIbβ3 activity and platelet aggregation in patients on HD is not only a consequence of antiplatelet therapy. In our study, low daily doses of ASA had no additional effect on platelet activation and aggregation that was strong enough to trigger significant changes between users and nonusers. This could be explained by aspirin resistance, which is known to occur to a higher degree in patients on HD than in other patient populations.56 Our patient sample was too small to adequately evaluate the response to ASA in patients on HD. To our knowledge, a link between carbamylation and ASA resistance has not been investigated before. However, it is conceivable that carbamylation impairs the effect of ASA by decreasing its bioavailability or increasing platelet turnover.

Taken together, our results clearly indicate that αIIbβ3 carbamylation, and specifically modification of the K185 residue, may be one of the underlying causes of platelet dysfunction in patients with ESKD.

Disclosures

T. Hervig reports receiving research funding from Cellphire. H.-P. Marti reports receiving research funding from Alexion, Amicus, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Takeda-Shire; and serving as a member of the American Society of Nephrology (fellow), European Renal Association–European Dialysis and Transplant Association, Norwegian Medical Association, Norwegian Society of Nephrology, Norwegian Society of Hypertension, and Swiss Society of Nephrology. J. Potempa reports receiving research funding from Colgate; having consultancy agreements with, having ownership interest in, and serving in an advisory or leadership role for Cortexyme Inc.; and having patents or royalties with University of Georgia. P. Thompson reports having ownership interest in AstraZeneca, Danger Bio, Merck, and Pfizer; serving as a consultant for Celgene and Disarm Therapeutics; having consultancy agreements with Odyssey Therapeutics and Related Sciences/Danger Bio; being the founder of Padlock Therapeutics, which was acquired by Bristol Myers Squibb in 2016 and is entitled to payments if certain milestones are met; and having patents or royalties with University of South Carolina. R. Tilvawala reports having ownership interest in Nio, Overstock, and Robinhood. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was funded by National Science Center grant 2019/33/B/NZ4/01889 (Poland), Helse Vest open project grant 303567, and Norwegian Research Council grant 296129. P. Mydel and V. Binder were supported by the Broegelmann Foundation. Work in the P.R. Thompson laboratory is supported, in part, by National Institutes of Health grant R35GM118112.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kristin Saele, Ingebjørg Margareth Gangstø, and all staff members at the dialysis unit at Haukeland University Hospital for their help with collecting the patient samples. The authors also thank all patients and voluntary blood donors for their readiness to contribute to the study.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Author Contributions

B. Bergum, V. Binder, B. Chruścicka-Smaga, P. Gillery, T. Hervig, S. Jaisson, P. Mydel, J. Sivertsen, P.R. Thompson, and R. Tilvawala were responsible for formal analysis; B. Bergum, V. Binder, B. Chruścicka-Smaga, P. Gillery, T. Hervig, M. Kaminska, S. Jaisson, V.V. Nemmara, J. Sivertsen, and P.R. Thompson were responsible for methodology; V. Binder, B. Chruścicka-Smaga, P. Gillery, S. Jaisson, V.V. Nemmara, and R. Tilvawala were responsible for data curation; V. Binder, B. Chruścicka-Smaga, T. Hervig, H.-P. Marti, and P. Mydel conceptualized the study; V. Binder, B. Chruścicka-Smaga, T. Hervig, and P. Mydel were responsible for investigation; V. Binder, B. Chruścicka-Smaga, S. Jaisson, P. Mydel, and R. Tilvawala wrote the original draft; V. Binder, B. Chruścicka-Smaga, P. Mydel, and R. Tilvawala were responsible for visualization; V. Binder, H.-P. Marti, and P. Mydel were responsible for project administration; P. Gillery, T. Hervig, H.-P. Marti, P. Mydel, J. Potempa, and P.R. Thompson were responsible for resources; P. Mydel and P.R. Thompson were responsible for funding acquisition; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

All data used in this study are available in this article.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2022010013/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1. Blood urea concentrations of individual patients and patient pools.

Supplemental Figure 1. Biological replicates to Figure 1.

Supplemental Figure 2. Biological replicates to Figure 2.

Supplemental Figure 3. Platelet carbamylation does not affect PAR-1 cleavage and agranule secretion.

Supplemental Figure 4. Platelet carbamylation has no impact on GpIb function.

Supplemental Figure 5. Carbamylation affects activation of αIIbβ3 expressed in HEK293 cells.

References

- 1.Hedges SJ, Dehoney SB, Hooper JS, Amanzadeh J, Busti AJ: Evidence-based treatment options for uremic bleeding. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 3: 130–153, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noris M, Remuzzi G: Uremic bleeding: Closing the circle after 30 years of controversies? Blood 94: 2569–2574, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lutz J, Menke J, Sollinger D, Schinzel H, Thürmel K: Haemostasis in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 29–40, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo C-C, Kuo H-W, Lee I-M, Lee C-T, Yang C-Y: The risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients treated with hemodialysis: A population-based cohort study. BMC Nephrol 14: 15, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jalal DI, Chonchol M, Targher G: Disorders of hemostasis associated with chronic kidney disease. Semin Thromb Hemost 36: 34–40, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Bladel ER, de Jager RL, Walter D, Cornelissen L, Gaillard CA, Boven LA, et al. : Platelets of patients with chronic kidney disease demonstrate deficient platelet reactivity in vitro. BMC Nephrol 13: 127, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaw D, Malhotra D: Platelet dysfunction and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial 19: 317–322, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joist JH, George JN: Hemostatic abnormalities in liver and renal disease. In: Hemostasis and Thrombosis: Basic principles and clinical practice, edited by Colman RW, Hirsh J, Marder VJ, Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001, pp 955–973 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linthorst GE, Avis HJ, Levi M: Uremic thrombocytopathy is not about urea. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 753–755, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galbusera M, Remuzzi G, Boccardo P: Treatment of bleeding in dialysis patients. Semin Dial 22: 279–286, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molino D, De Lucia D, Gaspare De Santo N: Coagulation disorders in uremia. Semin Nephrol 26: 46–51, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen G, Hörl WH: Immune dysfunction in uremia—an update. Toxins (Basel) 4: 962–990, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vanholder R, Pletinck A, Schepers E, Glorieux G: Biochemical and clinical impact of organic uremic retention solutes: A comprehensive update. Toxins (Basel) 10: 33, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lisowska-Myjak B: Uremic toxins and their effects on multiple organ systems. Nephron Clin Pract 128: 303–311, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delanghe S, Delanghe JR, Speeckaert R, Van Biesen W, Speeckaert MM: Mechanisms and consequences of carbamoylation. Nat Rev Nephrol 13: 580–593, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verbrugge FH, Tang WH, Hazen SL: Protein carbamylation and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int 88: 474–478, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalim S, Karumanchi SA, Thadhani RI, Berg AH: Protein carbamylation in kidney disease: Pathogenesis and clinical implications. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 793–803, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraus LM, Gaber L, Handorf CR, Marti H-P, Kraus AP Jr: Carbamoylation of glomerular and tubular proteins in patients with kidney failure: A potential mechanism of ongoing renal damage. Swiss Med Wkly 131: 139–4, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanholder R, Gryp T, Glorieux G: Urea and chronic kidney disease: The comeback of the century? (in uraemia research). Nephrol Dial Transplant 33: 4–12, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shaykh M, Pegoraro AA, Mo W, Arruda JA, Dunea G, Singh AK: Carbamylated proteins activate glomerular mesangial cells and stimulate collagen deposition. J Lab Clin Med 133: 302–308, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trepanier DJ, Thibert RJ, Draisey TF, Caines PS: Carbamylation of erythrocyte membrane proteins: An in vitro and in vivo study. Clin Biochem 29: 347–355, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pieniazek A, Gwoździński K: Carbamylation of proteins leads to alterations in the membrane structure of erythrocytes. Cell Mol Biol Lett 8: 127–131, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mun K-C, Kim H-C, Kwak C-S: Cyanate as a hemolytic factor. Ren Fail 22: 809–814, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraus LM, Elberger AJ, Handorf CR, Pabst MJ, Kraus AP Jr: Urea-derived cyanate forms epsilon-amino-carbamoyl-lysine (homocitrulline) in leukocyte proteins in patients with end-stage renal disease on peritoneal dialysis. J Lab Clin Med 123: 882–891, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Broos K, De Meyer SF, Feys HB, Vanhoorelbeke K, Deckmyn H: Blood platelet biochemistry. Thromb Res 129: 245–249, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gawaz MP, Dobos G, Späth M, Schollmeyer P, Gurland HJ, Mujais SK: Impaired function of platelet membrane glycoprotein IIb-IIIa in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 36–46, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Małyszko J, Małyszko JS, Myśliwiec M, Buczko W: Hemostasis in chronic renal failure. Rocz Akad Med Bialymst 50: 126–131, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monroe DM, Hoffman M, Roberts HR: Platelets and thrombin generation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22: 1381–1389, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kahn ML, Nakanishi-Matsui M, Shapiro MJ, Ishihara H, Coughlin SR: Protease-activated receptors 1 and 4 mediate activation of human platelets by thrombin. J Clin Invest 103: 879–887, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Candia E: Mechanisms of platelet activation by thrombin: A short history. Thromb Res 129: 250–256, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Binder V, Bergum B, Jaisson S, Gillery P, Scavenius C, Spriet E, et al. : Impact of fibrinogen carbamylation on fibrin clot formation and stability. Thromb Haemost 117: 899–910, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jaisson S, Desmons A, Doué M, Gorisse L, Pietrement C, Gillery P: Measurement of homocitrulline, a carbamylation-derived product, in serum and tissues by LC-MS/MS. Curr Protoc Protein Sci 92: e56, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bicker KL, Subramanian V, Chumanevich AA, Hofseth LJ, Thompson PR: Seeing citrulline: Development of a phenylglyoxal-based probe to visualize protein citrullination. J Am Chem Soc 134: 17015–17018, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Litvinov RI, Barsegov V, Schissler AJ, Fisher AR, Bennett JS, Weisel JW, et al. : Dissociation of bimolecular αIIbβ3-fibrinogen complex under a constant tensile force. Biophys J 100: 165–173, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhu J, Luo B-H, Xiao T, Zhang C, Nishida N, Springer TA: Structure of a complete integrin ectodomain in a physiologic resting state and activation and deactivation by applied forces. Mol Cell 32: 849–861, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gawaz M, Neumann F-J, Schomig A: Evaluation of platelet membrane glycoproteins in coronary artery disease: Consequences for diagnosis and therapy. Circulation 99: E1–E11, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kalim S, Ortiz G, Trottier CA, Deferio JJ, Karumanchi SA, Thadhani RI, et al. : The effects of parenteral amino acid therapy on protein carbamylation in maintenance hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr 25: 388–392, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Cuyper IM, Meinders M, van de Vijver E, de Korte D, Porcelijn L, de Haas M, et al. : A novel flow cytometry-based platelet aggregation assay. Blood 121: e70–e80, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koeth RA, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Wang Z, Fu X, Tang WH, Hazen SL: Protein carbamylation predicts mortality in ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 853–861, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Gamal D, Holzer M, Gauster M, Schicho R, Binder V, Konya V, et al. : Cyanate is a novel inducer of endothelial icam-1 expression. Antioxid Redox Signal 16: 129–137, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blackmore DJ, Elder WJ, Bowden CH: Urea distribution in renal failure. J Clin Pathol 16: 235–243, 1963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Gamal D, Rao SP, Holzer M, Hallström S, Haybaeck J, Gauster M, et al. : The urea decomposition product cyanate promotes endothelial dysfunction. Kidney Int 86: 923–931, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufman RM: Platelets: Testing, dosing and the storage lesion--recent advances. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2006: 492–496, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papadaki S, Sidiropoulou S, Moschonas IC, Tselepis AD: Factor Xa and thrombin induce endothelial progenitor cell activation. The effect of direct oral anticoagulants. Platelets 32: 807–814, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nieman MT, Schmaier AH: Interaction of thrombin with PAR1 and PAR4 at the thrombin cleavage site. Biochemistry 46: 8603–8610, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mumford AD, Frelinger AL 3rd, Gachet C, Gresele P, Noris P, Harrison P, et al. : A review of platelet secretion assays for the diagnosis of inherited platelet secretion disorders. Thromb Haemost 114: 14–25, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fullard JF: The role of the platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa in thrombosis and haemostasis. Curr Pharm Des 10: 1567–1576, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma Y, Tonelli M, Unsworth LD: Effect of carbamylation on protein structure and adsorption to self-assembled monolayer surfaces. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 203: 111719, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Desmons A, Okwieka A, Doué M, Gorisse L, Vuiblet V, Pietrement C, et al. : Proteasome-dependent degradation of intracellular carbamylated proteins. Aging (Albany NY) 11: 3624–3638, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chinthalapudi K, Rangarajan ES, Izard T: The interaction of talin with the cell membrane is essential for integrin activation and focal adhesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115: 10339–10344, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang P, Azizi L, Kukkurainen S, Gao T, Baikoghli M, Jacquier MC, et al. : Crystal structure of the FERM-folded talin head reveals the determinants for integrin binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117: 32402–32412, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Botero JP, Lee K, Branchford BR, Bray PF, Freson K, Lambert MP, et al. : ClinGen Platelet Disorder Variant Curation Expert Panel: Glanzmann thrombasthenia: Genetic basis and clinical correlates. Haematologica 105: 888–894, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berg AH, Drechsler C, Wenger J, Buccafusca R, Hod T, Kalim S, et al. : Carbamylation of serum albumin as a risk factor for mortality in patients with kidney failure. Sci Transl Med 5: 175ra29, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tucker KL, Sage T, Gibbins JM: Clot retraction. Methods Mol Biol 788: 101–107, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Metharom P, Berndt MC, Baker RI, Andrews RK: Current state and novel approaches of antiplatelet therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 35: 1327–1338, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aksu HU, Oner E, Celik O, Isiksacan N, Aksu H, Uzun S, et al. : Aspirin resistance in patients undergoing hemodialysis and effect of hemodialysis on aspirin resistance. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 21: 82–86, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.