Key Points

Osteopontin (OPN) is highly expressed by tubular epithelial cells in CKD and functions to maintain calcium-phosphate solubility in tubular fluid.

Reduced functional nephrons alone, in the absence of kidney injury, is sufficient to stimulate OPN expression by tubular epithelial cells.

High levels of tubular fluid phosphate or the presence of phosphate-based crystals may stimulate tubular OPN production in CKD.

Keywords: mineral metabolism, basic science, chronic kidney disease, mineral metabolism, nephrocalcinosis, osteopontin, phosphate, solubility

Visual Abstract

Abstract

Background

Nephron loss dramatically increases tubular phosphate to concentrations that exceed supersaturation. Osteopontin (OPN) is a matricellular protein that enhances mineral solubility in solution; however, the role of OPN in maintaining urinary phosphate solubility in CKD remains undefined.

Methods

Here, we examined (1) the expression patterns and timing of kidney/urine OPN changes in CKD mice, (2) if tubular injury is necessary for kidney OPN expression in CKD, (3) how OPN deletion alters kidney mineral deposition in CKD mice, (4) how neutralization of the mineral-binding (ASARM) motif of OPN alters kidney mineral deposition in phosphaturic mice, and (5) the in vitro effect of phosphate-based nanocrystals on tubular epithelial cell OPN expression.

Results

Tubular OPN expression was dramatically increased in all studied CKD murine models. Kidney OPN gene expression and urinary OPN/Cr ratios increased before changes in traditional biochemical markers of kidney function. Moreover, a reduction of nephron numbers alone (by unilateral nephrectomy) was sufficient to induce OPN expression in residual nephrons and induction of CKD in OPN-null mice fed excess phosphate resulted in severe nephrocalcinosis. Neutralization of the ASARM motif of OPN in phosphaturic mice resulted in severe nephrocalcinosis that mimicked OPN-null CKD mice. Lastly, in vitro experiments revealed calcium-phosphate nanocrystals to induce OPN expression by tubular epithelial cells directly.

Conclusions

Kidney OPN expression increases in early CKD and serves a critical role in maintaining tubular mineral solubility when tubular phosphate concentrations are exceedingly high, as in late-stage CKD. Calcium-phosphate nanocrystals may be a proximal stimulus for tubular OPN production.

Introduction

Renal excretion of phosphate is extremely efficient in healthy kidneys, allowing serum phosphate concentrations to be maintained in a very narrow range, despite fluctuations in dietary phosphate consumption. Phosphate retention promotes a constellation of mineral metabolism, bone, and cardiovascular abnormalities that contribute to the exceedingly high morbidity and mortality observed in patients with CKD (1); thus, compensatory mechanisms have evolved specifically to promote urinary phosphate excretion when functional nephron numbers are diminished. Early micropuncture studies conducted on nephrons from CKD rats showed a dramatic increase in the tubular phosphate concentration compared with wild-type (WT) rats (2). Likewise, studies in humans have found a progressive rise in the urinary fractional excretion of phosphate starting in early CKD (3). This early rise in urinary phosphate excretion is largely driven by fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), a bone-derived hormone that accumulates in the serum of patients with decreased nephron mass (4).

Osteopontin (OPN), encoded by the secreted phosphoprotein 1 (Spp1) gene, is a multifunctional protein that is produced by a variety of cells, including tubular epithelial cells, and is present at high concentrations in urine (5). OPN contains a phosphorylated polyaspartate region (ASARM sequence) that binds calcium-based crystals to prevent their expansion (6,7). Prior studies examining the role of OPN in kidney stone formation have demonstrated OPN to serve a prominent role in maintaining mineral solubility in urine where mineral concentrations often exceed supersaturation (8–10). OPN production by tubular epithelial cells is dramatically increased in CKD; however, the role of this protein in this setting remains unclear.

Because tubular fluid phosphate concentrations are highly elevated in CKD and exceed the anticipated supersaturation point for the precipitation of calcium-phosphate complexes (2), we speculated that this increased production of OPN by tubular epithelial cells may be an adaptive response to prevent tubular crystal formation when functional nephron numbers are reduced. To test this hypothesis, we (1) characterized the timing of renal OPN changes in CKD mice, (2) investigated if tubular injury was necessary for enhancing tubular OPN production or if nephron reduction alone was sufficient to induce this response, (3) examined how induction of CKD in OPN-null mice altered tubular phosphate solubility, (4) determined how neutralization of the ASARM motif (the domain of OPN that binds mineral and enhances its solubility) alters kidney mineralization in phosphaturic mice, and (5) evaluated the direct effect of phosphate-based nanocrystals on tubular epithelial expression of OPN.

Materials and Methods

Animal Preparation and Study Protocol

All mice were maintained in accordance with recommendations in the “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” from the Institute on Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council, and all animal protocols were approved by the University of Kansas Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee before the commencement of this research. Spp1−/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (C57BL/6J, stock # 004936); NaPi2a−/− mice (129Sv background) were generated from our in-house line that was originally donated by Dr. H. Susie Tenenhouse (11). The Hyp strain was originally obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (C57BL/6J, stock # 003950). Pcy/pcy mice (C57BL/6J background) were originally donated by Dr. Darren Wallace at the University of Kansas Medical Center. Col4a3−/− mice (F1 hybrid strain) were generated from breeding two separate lines of Col4a3 mice from pure C57BL/6J and SV129 backgrounds and studying only the first-generation offspring, as previously described (12). All mice were maintained on an ad libitum standard rodent diet unless otherwise noted. Studies involving a high-phosphate diet used a custom-made diet developed by Teklad (Indianapolis, IN) to contain 1.1% nonphytate phosphorus, 0.6% calcium, and 3000 IU/kg vitamin D (TD.190801).

Induction of CKD

For the induction of CKD by adenine diet, adenine was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO; catalog #A9451) and provided to Teklad for incorporation into our custom high-phosphate diet for a final adenine content of 0.2% adenine per kilogram of diet. Adenine-induced CKD was achieved by feeding mice this diet ad libitum over an 8-week duration. For the induction of CKD by aristolochic acid, aristolochic acid was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (catalog #A8626) and mixed with PBS before administration to adult mice by intraperitoneal (ip) injection at a dose of 3 mg/kg body weight five times per week for 9 weeks.

Administration of SPR4 Peptide to Hyp Mice

SPR4 (small synthetic peptide 4) is a 4.2 kDa peptide that was designed “biomolecularly” to mimic the PHEX (phosphate-regulating endopeptidase homolog X-linked) protein zinc catalytic binding site. PHEX is the only known protease that binds and cleaves ASARM peptide. The biochemical properties of SPR4 peptide have been extensively characterized in our prior publication (13). To prepare SPR4 for injection in the current studies, 10 mg of SPR4 peptide was first dissolved in 1 ml of 25 mM acetic acid, then 9 ml of 50 mM Tris (pH 7.4)/150 mM NaCl was added and thoroughly mixed. Finally, 200 μl of 1 mM ZnCl2 was added and mixed thoroughly to generate the final SPR4 solution. Adult Hyp mice consuming a 2% phosphate diet (Teklad TD.170496) were administered an initial 500 μg bolus of SPR4 (or vehicle) at study initiation and were then dosed with a total of 1175 μg SPR4 divided among eight ip injections over 8 weeks. Mice were euthanized 12 weeks after study initiation for tissue collection.

Tissue Processing and Histology

Kidneys were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4-μm sections. For periodic acid-Schiff and Von Kossa staining, sections were processed using standard staining protocols. For OPN immunohistochemistry (IHC), sections were deparaffinized and steamed in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes and then incubated in 3% H2O2 for 10 minutes followed by incubation in horse serum for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then incubated with anti-OPN (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN; catalog #AF808) overnight at 4°C. An ImmPRESS horseradish peroxidase horse anti-goat IgG secondary antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA; catalog #MP-7045) was applied for 1 hour at room temperature followed by the incubation with DAB substrate and hematoxylin counterstaining. Images for IHC quantification were taken at ×20 magnification using a Lumenera INFINITY-5 camera, with three images obtained from predetermined locations from a midsagittal kidney section of each sample. Nikon image analysis software was used to create a threshold binary overlay, with 1.12 as a cutoff, and pixel intensity of the DAB staining was quantified for each image by an operator blinded to sample identification. Data were calculated as a ratio of total DAB-positive area relative to the total tissue area, and the calculated average value obtained from three pooled images for each sample was used as the final expression value for that sample.

Biochemical Measurements and Reagents

Measurements of BUN and phosphorus in samples from Col4a3−/− and control mice were obtained using an Integra 400 Plus Bioanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Intact FGF23 was measured by ELISA (Kainos Lab, Tokyo, Japan), and parathyroid hormone (PTH) by the Mouse Intact PTH ELISA (Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH). Urine OPN was measured using a mouse/rat OPN ELISA (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The SPR4-peptide was synthesized using standard techniques by Polypeptide Laboratories (San Diego, CA), and purity was confirmed at >85% via HPLC, ion-exchange, and mass spectrometry, as previously described (13).

Gene Expression Analyses

For quantitative real-time PCR analysis of tissue gene expression, kidney specimens were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C until further processing. Details of tissue processing and primer sequences are provided in the Supplemental Methods.

Transcriptomic analysis of kidney OPN gene expression changes in Col4a3−/− mice was conducted after the Illumina TruSeq mRNA-Seq protocol, with at least 15 million reads for each sample. All FASTQ files from the RNA-Seq experiment were processed with Omicsoft Array Studio v6.2. Sequence reads were mapped to the reference mouse genome (Genome Reference Consortium Build 37) by the Omicsoft Aligner. Alignments were then quantified into FPKM values at the gene level using the gene model from “RefGene20121217” (14). For differential expression analysis, log2 (FPKM+1) values were used for Student’s two-tailed t test on Col4a3−/− versus WT at different ages over the disease progression

Micro-Computed Tomography Imaging

Whole formalin-fixed kidneys were individually wrapped and heat-sealed in cling film to prevent dehydration and stacked in a sample container for batch analysis by a Scanco micro-QCT 40 (Scanco Medical, Brüttisellen, Switzerland). A batch control file with the following specifications was used: energy intensity 45 kVp, 88 μA, and 4W; field of view/diameter 12 mm; voxel (VOX) resolution size 6 μM; integration time 300 mS. After raw data acquisition and computer reconstruction, the output files were contoured and defined using the Scanco software morph and integration functions. For three-dimensional image and quantitative analyses, a script file with the following specifications was used: Gauss σ=0.8, Gauss support=1; lower threshold=255 mg HA/ccm, upper threshold 1513 mg HA/ccm.

Cell Culture Studies

Cell culture experiments were conducted using both a mouse collecting duct cell line (mIMCD-3 cells, originally purchased from ATCC, Manassas, VA) and a novel human collecting duct cell line (RCTE-WT cells, developed by Dr. Chris Ward’s laboratory; publication pending). Calcium-phosphate (hydroxyapatite) nanocrystals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO; catalog #677418). mIMCD-3 cells were plated at 200,000 cells/well in six-well plates containing DMEM/F12 with 10% FBS and grown to 100% confluency (for 3 days). Once confluent, cells were treated with 500 μg/ml of hydroxyapatite nanocrystals for 24, 48, and 72 hours in the same medium. RCTE-WT cells were plated at 200,000 cells/well in six-well plates containing RPMI-1640 with 5% FBS and grown to 100% confluency. Once confluent, cells were treated with 500 μg/ml of hydroxyapatite for 24, 48, and 72 hours in the same medium. All control cells were incubated in identical medium alone.

Statistical Analyses

Differences between multiple groups were evaluated by one-way ANOVA. Differences between two groups at a single time point were evaluated by two-sided Student’s t test (for data with a Gaussian distribution) or Mann–Whitney test (for data with a non-Gaussian distribution); a t test with Welch’s correction was used when equal variances could not be assumed. Computations were performed using GraphPad Prism v8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

Results

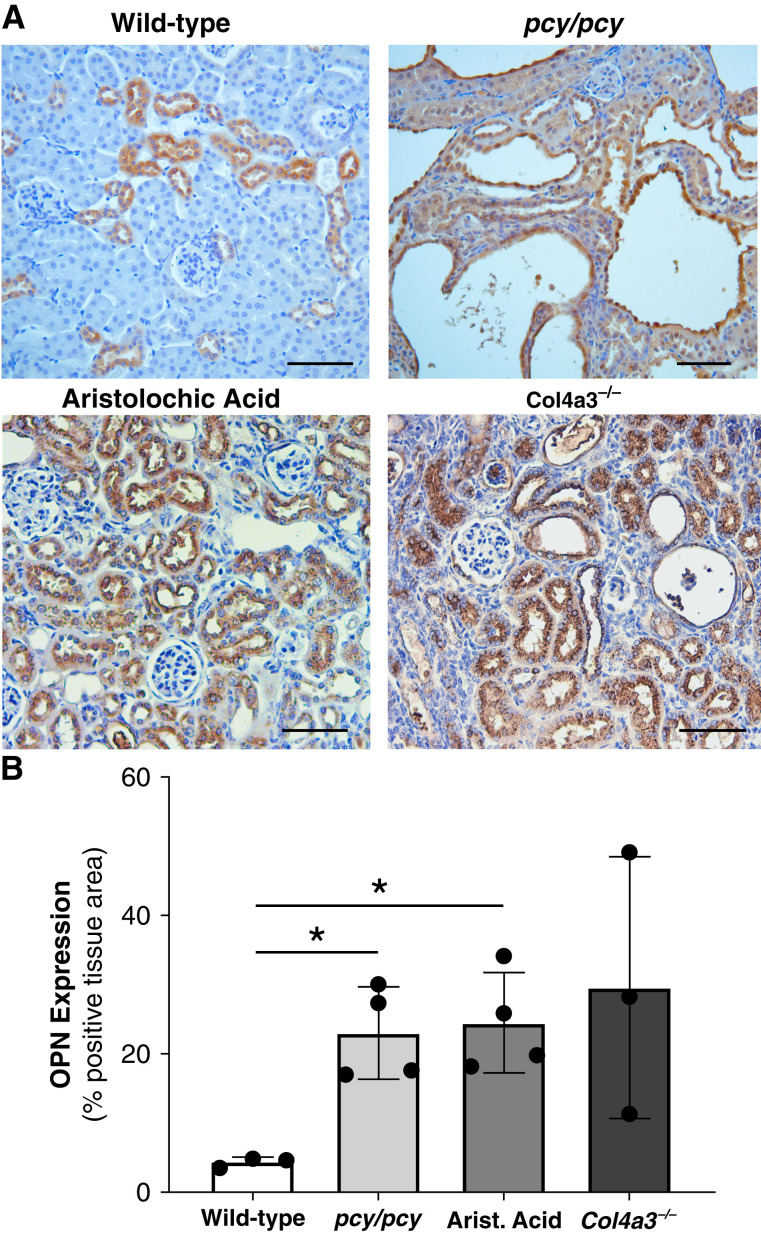

Tubular OPN Expression Is Consistently Increased in CKD Murine Models

To examine kidney OPN expression patterns in response to various forms of chronic kidney injury, we performed IHC of kidney sections from multiple CKD murine models, including cystic kidney disease (pcy/pcy), tubular toxin (aristolochic acid), and glomerulonephritis (Col4a3−/−) models (Figure 1A). We observed WT mice to exhibit OPN expression restricted to distal tubule epithelial cells (as previously described) (5), whereas CKD models all exhibited a dramatic increase in OPN expression in all other tubular segments. Quantification of OPN tissue staining confirmed a consistent increase in kidney OPN expression in all CKD models compared with WT mice (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Kidney osteopontin (OPN) expression is increased in various CKD murine models. (A) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of OPN protein expression (brown) in kidneys from mice with normal kidney function (wild type [WT]), cystic kidney disease (pcy/pcy), chronic tubular injury/fibrosis (aristolochic acid), and primary glomerulonephritis (Alport disease; Col4a3−/−). WT mice exhibit OPN staining in distal tubules, whereas all other CKD models demonstrate diffuse OPN staining in all nephron segments. (B) Quantification of OPN IHC staining confirmed the higher OPN expression in CKD models. Representative images were selected from a minimum of three per group; scale bar=100 µm for all images (*P<0.05 versus WT by t test with Welch’s correction; data presented as mean±SD).

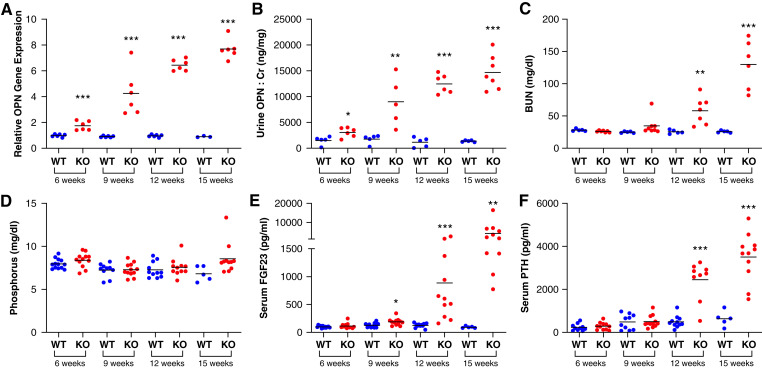

Kidney OPN Expression Is Upregulated Very Early in CKD Mice

To examine the timing of kidney OPN changes in CKD, we performed cross-sectional assessments of kidney Spp1 (OPN) gene expression (using an RNA-Seq database) (12) and measured urine OPN-to-creatinine ratios to define how changes in these parameters correspond to alterations in biomarkers of mineral metabolism and kidney function across the lifespan of Col4a3−/− mice, a murine model of human Alport syndrome that exhibits a CKD mineral and bone disorder phenotype similar to humans (15). We found kidney OPN gene expression and urine OPN-to-creatinine ratios to be substantially elevated by 6 weeks of age (Figure 2, A and B, respectively), long before elevations in BUN, phosphate, FGF23, or PTH (Figure 2, C–F).

Figure 2.

Kidney expression and urine concentrations of OPN are increased long before changes in traditional kidney function markers and mineral metabolism parameters in Col4a3−/− (knockout) mice. Col4a3−/− mice possess defective glomerular basement membrane structure leading to severe proteinuria and progressive CKD. We characterized changes in kidney and urine OPN in relation to established mineral metabolism and kidney function parameters in Col4a3−/− mice (F1 hybrid background for SV129 and C57Bl/6 strains) at 6, 9, 12, and 15 weeks of age. These measurements included (A) kidney OPN gene expression, (B) urine OPN/creatinine (Cr) ratio, (C) BUN, (D) serum phosphorus, (E) serum fibroblast growth factor 23, and (F) serum parathyroid hormone (**P<0.01, ***P<0.001 versus WT of same age; bars=mean per group).

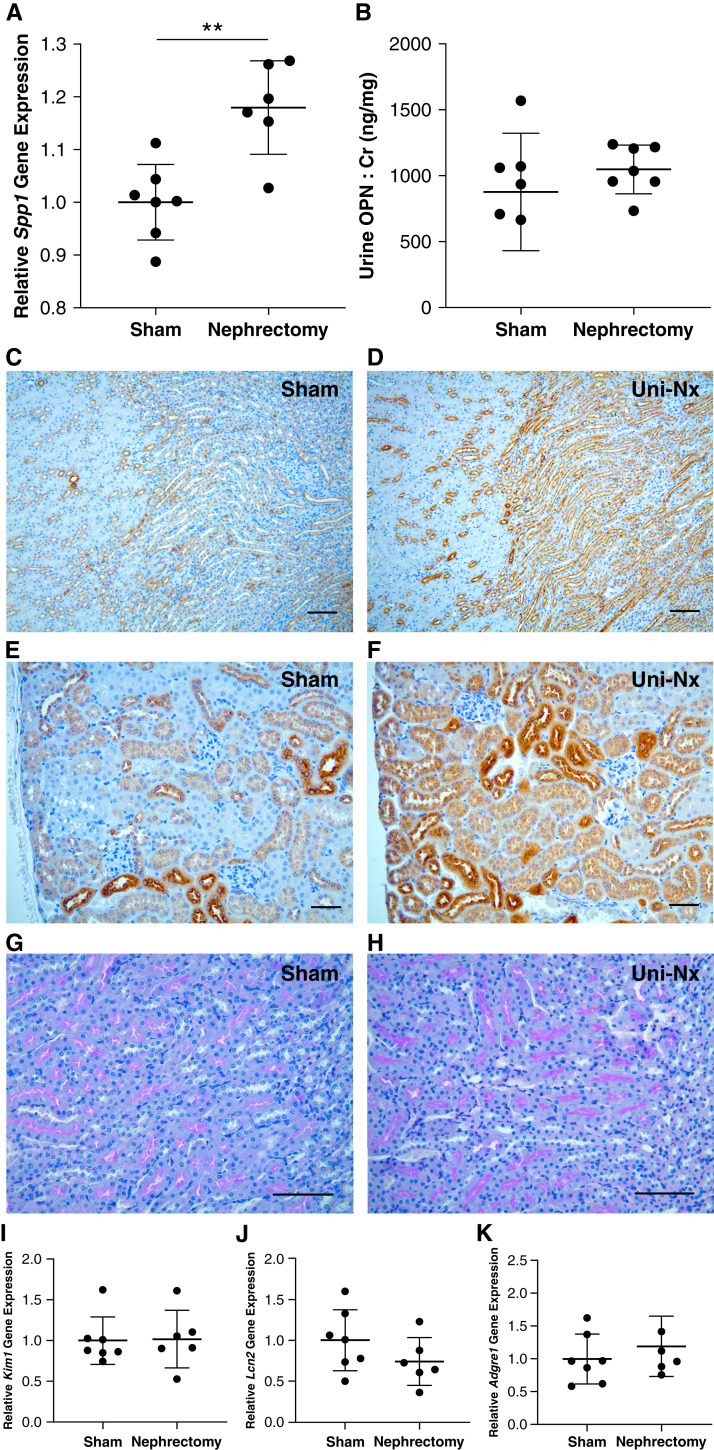

Reduction in Functional Nephron Numbers Induces Kidney Spp1 (OPN) Gene Expression in Residual Nephrons

To determine if tubular injury was necessary for the upregulation of tubular epithelial cell production of OPN (versus nephron depletion alone), we investigated kidney OPN expression changes in mice undergoing unilateral nephrectomy versus a sham operation. In kidney specimens collected 3 weeks after surgery, we found Spp1 (OPN) gene expression to be increased in unilateral nephrectomy mice compared with sham mice (Figure 3A); however, a comparison of urinary OPN-to-creatinine ratios between these groups revealed no obvious difference in urinary OPN excretion (Figure 3B). To evaluate differences in kidney tissue expression of OPN protein, we performed IHC for OPN in kidney sections from these same sham and nephrectomy groups and found that residual kidneys harvested from unilateral nephrectomy mice exhibited a profound increase in OPN protein expression in both medullary and cortical tubular segments (Figure 3, D and F, respectively). To confirm that the observed OPN expression was not secondary to tubular injury related to the nephrectomy procedure, we performed periodic acid-Schiff staining of kidney sections (Figure 3, G and H) and gene expression by quantitative real-time PCR for markers of tubular injury, including Kim-1 and Lcn2 (NGAL; Figure 3, I and J). Notably, we observed no evidence of tubular damage by either blinded histology evaluation or gene expression for injury markers, making it unlikely that acute injury was driving the OPN expression in this model. Finally, to examine if this enhanced OPN expression led to macrophage recruitment, we performed Adgre1 (F4/80) gene expression analysis and IHC staining for CD68, an established macrophage marker. We observed no difference in Adgre1 gene expression between the two groups (Figure 3K), and there was no obvious macrophage staining in kidney sections by IHC (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Kidney OPN expression is increased by reduction of functional nephrons (unilateral nephrectomy; Uni-Nx). (A) Spp1 (OPN) gene expression by quantitative real-time PCR was increased in the remaining kidney at 3 weeks post unilateral nephrectomy compared with sham-operated littermates. (B) No difference was observed in urine OPN (normalized to Cr). (C) and (D) IHC staining of residual kidneys from nephrectomy mice demonstrated markedly increased OPN expression (brown staining) in medullary tubules near the corticomedullary junction compared with sham controls (×10 magnification; scale bar=100 μm). Moreover, nearly all tubular segments in the kidney cortex (E) and (F) exhibited increased OPN expression in the Uni-Nx group (×20 magnification; scale bar=50 μm). Importantly, no evidence of tubular injury was observed by periodic acid-Schiff staining of kidney sections (G) and (H) (×20 magnification; scale bar=100 μm) or gene expression for Kim1 or Lcn2 (NGAL) (I) and (J). Additionally, Adgre1 (F4/80) expression was comparable for the two groups (K), suggesting no difference in macrophage accumulation in response to changes in OPN. Representative images were selected from a minimum of three per group (**P<0.01 by Student’s t test; all data presented as mean±SD; gene expression normalized to HPRT).

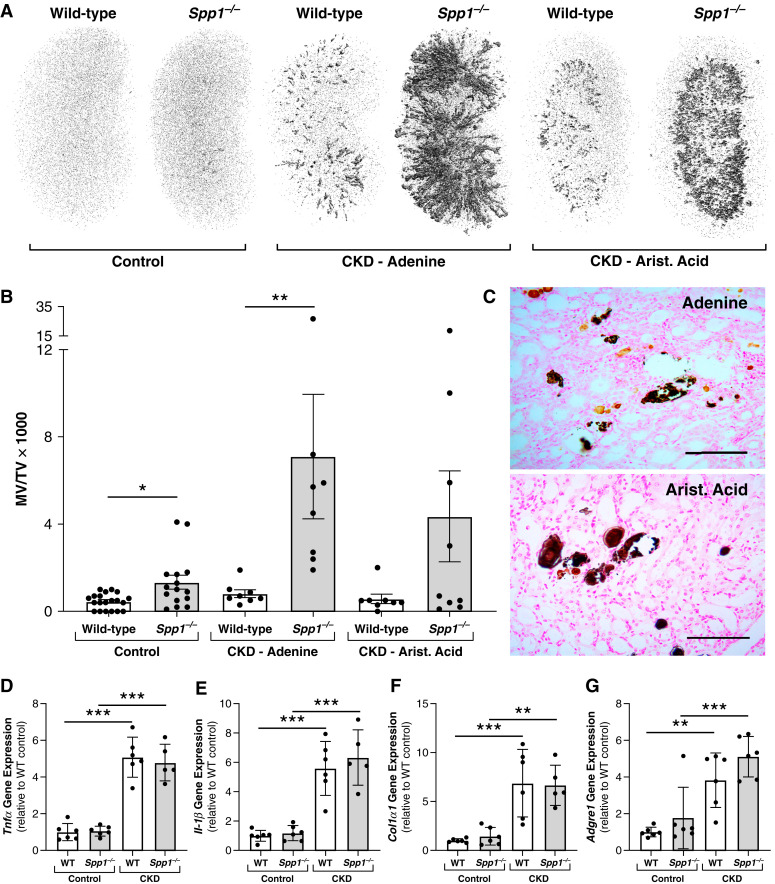

Induction of CKD in OPN-Null Mice Results in Severe Nephrocalcinosis

We evaluated the role of OPN in maintaining mineral solubility in tubular fluid of CKD mice by inducing CKD in Spp1−/− (OPN null) mice using two separate methods of CKD induction: ingestion of an adenine-containing diet, and ip injections of aristolochic acid. Micro-computed tomography scans of kidneys from these animals revealed extensive mineral deposition in kidneys from CKD mice lacking OPN expression (Figure 4). Interestingly, despite the markedly increased mineral deposition in Spp1−/− CKD mice compared with WT CKD mice (Figure 4, A and B), there was no obvious difference in gene expression patterns for markers of inflammation (Tnfα, Il-1β), fibrosis (Col1α1), and macrophage infiltration (Adgre1; Figure 4, D–G). Serum biochemical parameters were also assessed in these models, and the global absence of OPN had no obvious effect on serum mineral metabolism or kidney function parameters in CKD mice (Table 1).

Figure 4.

Induction of CKD in Spp1−/− (OPN-null) mice results in severe nephrocalcinosis. (A) Representative whole kidney micro-computed tomography (μCT) images demonstrating severe nephrocalcinosis in Spp1−/− mice after CKD induction by either chronic ingestion of 0.2% adenine or repeated subcutaneous injections of aristolochic acid. All mice were consuming a high (1.1%) phosphate diet for these studies to ensure high levels of urinary phosphate excretion. (B) Quantification of total kidney mineralized volume over total volume (MV/TV×1000) by μCT for all mice included in studies depicted in (A). (C) Von Kossa staining of kidney sections from CKD mice with OPN deletion showed a mixture of adenine (light brown) and phosphate-based crystals (black) in mice with CKD induced by adenine diet, whereas mice with CKD induced by aristolochic acid demonstrated only phosphate-based crystals (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 by one-way ANOVA; n≥8 per group for all μCT analyses; scale bars=100 μm). (D–G) Both WT and Spp1−/− mice with CKD induced by adenine diet exhibited increased kidney gene expression for markers of inflammation and fibrosis compared with non-CKD mice of the same genotype, including Tnfα (3D), Il-1β (3E), Col1α1 (3F), and Adgre1 (F4/80; 3G). However, Spp1 deletion had no apparent effect on the relative gene expression for these targets compared with WT mice within the same group (CKD or non-CKD; **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by one-way ANOVA; n≥5 per group for all gene analyses; data presented as mean±SD for all graphs).

Table 1.

Serum biochemistries in wild-type and Spp1−/− mice with and without CKD

| Control | CKD—Adenine | CKD—Aristolochic Acid | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Wild Type | Spp1−/− | Wild Type | Spp1−/− | Wild Type | Spp1−/− |

| Serum Phos (mg/dl) | 6.6±0.5 | 6.6±1.3 | 9.9±3.3b | 11.6±2.8b | 11.0±3.3b | 8.6±2b |

| Serum Ca (mg/dl) | 8.6±0.2 | 8.6±0.2 | 9.4±0.6b | 8.7±0.5a | 9.3±0.5 | 9.4±0.6b |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 685.7 | 617.1 | 1850.4 | 2449.6 | 1374.3 | 1905.5 |

| (569.1–908.2) | (446.3–1152.4) | (654.8–3071.1) | (1864.7–3529.5)b | (634.8–2079.2) | (1278–4766.6)b | |

| FGF23 (pg/ml) | 647.4 | 544.5 | 13,329.9 | 8021.8 | 8470.7 | 10,095.7 |

| (523.9–713.2) | (362.8–733.3) | (6369.8–20,416.4)b | (5080–13,992.4)b | (4478.2–14,691.9)b | (7427.3–21,706.7)b | |

| BUN (mg/dl) | 24.6±3.7 | 25.4±2.9 | 42.9±7.1b | 52.2±10.9b | 44.7±23.6b | 37.5±17.5b |

All normally distributed parameters are presented as mean±SD, non-normally distributed parameters (FGF23 and PTH) are presented as median (interquartile range); n≥7 mice per group for each time point. Group differences were analyzed by one-way ANOVA with multiple comparisons. Phos, phosphorus; Ca, calcium; PTH, parathyroid hormone; FGF23, fibroblast growth factor 23; Spp1−/−, OPN-null mice.

Statistically different (P<0.05) compared with WT in same group.

Statistically different (P<0.05) compared with mice of same genotype in control (non-CKD) group.

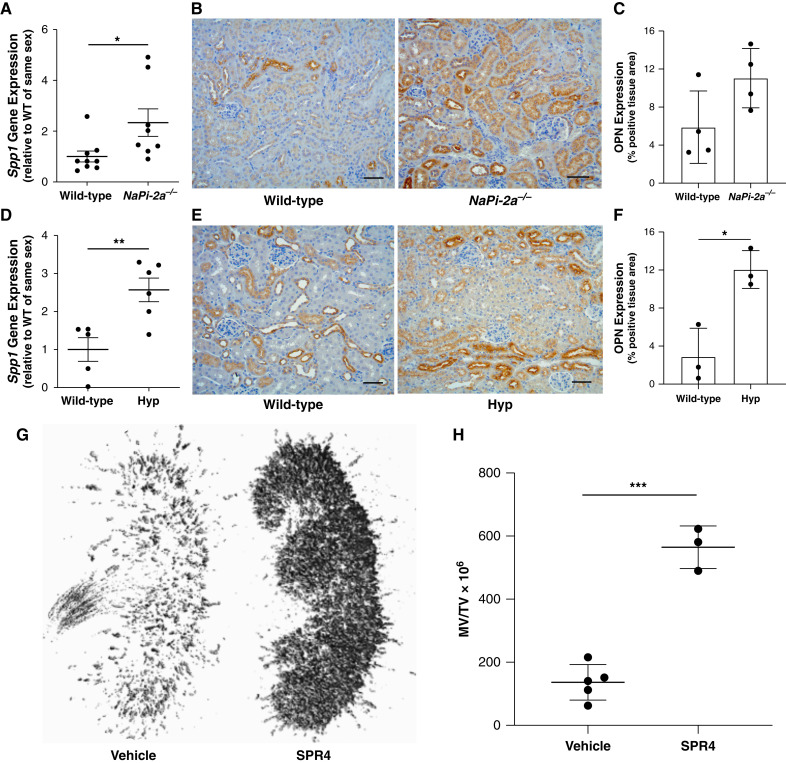

High Tubular Phosphate Concentrations Promote Kidney OPN Expression

Our prior studies demonstrated that feeding WT mice a low-phosphate diet resulted in a dramatic reduction in urinary OPN-to-creatinine ratio (16). We speculated that this observation resulted from reduced tubular fluid phosphate that would accompany low dietary phosphate ingestion. To determine if phosphaturia is a direct driver of kidney OPN production, we examined kidney OPN expression in two separate phosphaturic murine models: NaPi2a−/− mice (that exhibit primary phosphate wasting) and Hyp mice (that exhibit excess urinary phosphate excretion secondary to high serum FGF23). We observed kidney Spp1 (OPN) gene (Figure 5, A and D) and OPN protein (Figure 5, B and C and E and F) expression to be increased in both phosphaturic models.

Figure 5.

Kidney OPN and its ASARM peptide sequence serve a critical function in preventing nephrocalcinosis in the setting of phosphaturia. Two separate phosphaturic murine models, Napi2a−/− and Hyp mice, exhibit increased kidney OPN expression. (A) NaPi-2a−/− mice demonstrate increased kidney Spp1 (OPN) gene expression compared with WT littermates as assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. Moreover, (B) IHC staining revealed increased tubular OPN protein expression (brown) in kidney sections from NaPi-2a−/− mice. (C) Quantification of total OPN expression from images of mid-kidney sagittal cross-sections stained by IHC validated these observations. Similarly, phosphaturic Hyp mice exhibited (D) increased kidney Spp1 (OPN) gene expression, and (E) and (F) increased expression of OPN protein by IHC staining (all histology scale bars=50 μm). (G) Neutralization of the mineral binding (ASARM) peptide sequence of OPN with SPR4 peptide in Hyp mice results in severe nephrocalcinosis, as demonstrated by representative μCT images of whole kidneys from Hyp mice treated with either vehicle or SPR4. (H) Quantification of kidney mineralized tissue volume relative to total kidney volume (MV/TV) for all Hyp mice treated with either vehicle or SPR4 (for all analyses, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 by Student’s t test; n≥3 per group; data presented as mean±SD).

Neutralization of the Mineral-Binding (ASARM) Peptide Sequence of OPN Leads to Severe Nephrocalcinosis in Phosphaturic Mice

OPN contains a phosphorylated polyaspartate region (ASARM sequence) that is critical to its capacity to bind hydroxyapatite (calcium-phosphate) and enhance the solubility of this mineral compound in solution. We tested how neutralization of this ASARM motif altered tubular mineral solubility by administering an ASARM inhibitor (SPR4) to phosphaturic Hyp mice. We observed marked nephrocalcinosis in Hyp mice receiving SPR4 compared with vehicle-treated mice (Figure 5, G and H).

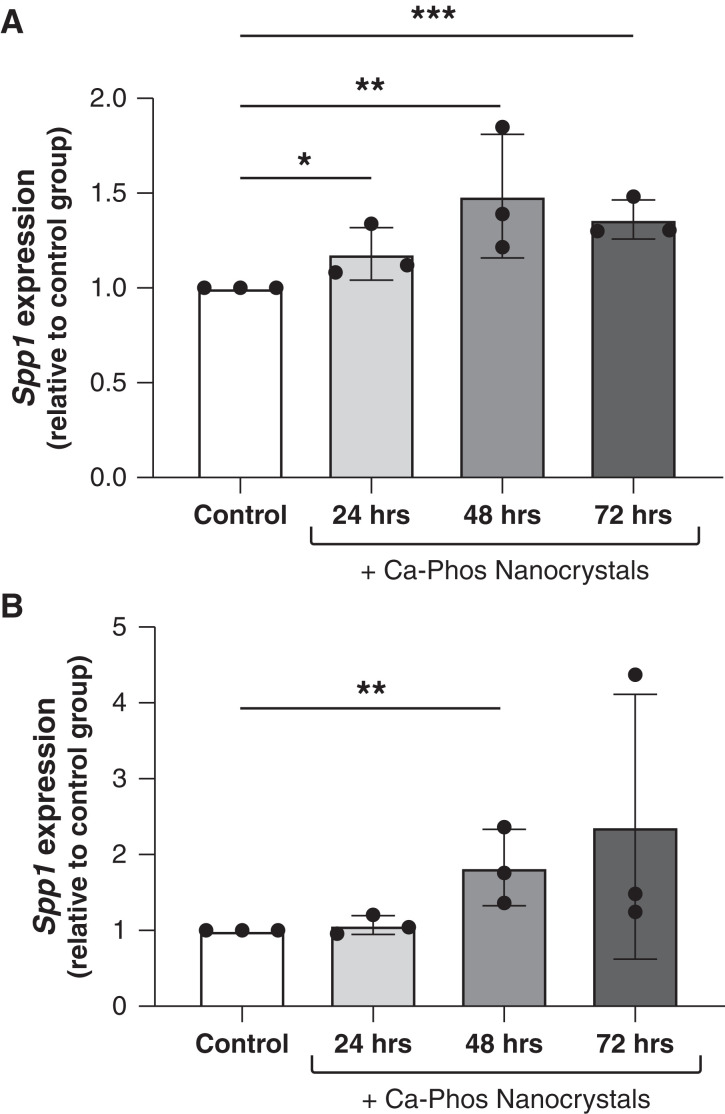

Calcium-Phosphate Nanocrystals Stimulate OPN Expression by Tubular Epithelial Cells In Vitro

We hypothesized that the formation of early calcium-phosphate nanocrystals in tubular fluid may be a proximal stimulus for OPN production by tubular epithelial cells in the setting of excess urinary phosphate excretion. To test this theory, we conducted in vitro cell culture experiments with two separate collecting duct cell lines: one of mouse origin (IMCD-3) and one of human origin (RCTE). Over the span of 72 hours, we observed the addition of calcium-phosphate nanocrystals stimulated Spp1 (OPN) gene expression in each of these cell lines (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Calcium-phosphate nanocrystals directly induce Spp1 (OPN) gene expression in tubular epithelial cells. Treatment of (A) mIMCD-3 cells, an immortalized mouse collecting duct cell line, or (B) RCTE cells, a novel human collecting duct cell line, with calcium-phosphate (hydroxyapatite) nanocrystals induced Spp1 gene expression compared with vehicle-treated control cells (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; data presented as mean±SD; a minimum of two replicates were included for each treatment group per experiment, and each experiment was run in triplicate).

Discussion

OPN, encoded by the secreted phosphoprotein 1 (Spp1) gene, is a multifunctional protein that is produced by tubular epithelial cells and is present at high concentrations in urine (5,17). The name “osteopontin” is derived from the Latin words for “bone” and “bridge” because a prominent feature of this protein is facilitating the attachment of mineral compounds to extracellular matrix or cells. In normal human and murine kidneys, OPN is primarily expressed by epithelial cells of the thick ascending limb and distal tubule (18); however, in the setting of kidney injury, OPN is produced by tubular epithelial cells located in other nephron segments (Figure 1).

The functional domains of OPN are highly conserved among species and include a phosphorylated polyaspartate region (ASARM sequence) that binds tightly to calcium-based mineral aggregates (6,7) and a separate RGD motif that binds to α-integrins to coordinate OPN attachment to matrix and cells and serves as a potent chemotactic stimulus for macrophage recruitment and propagates tissue fibrosis (19–24). Mice with inactivation of OPN exhibit impaired macrophage chemotaxis to sites of injury and altered wound healing (25,26). Prior animal studies suggest a dichotomous role of OPN in kidney biology. In rodent models of AKI, OPN promotes inflammation and fibrosis, as anti-OPN therapies attenuated these effects (27,28). On the contrary, studies investigating the role of OPN in kidney stone formation have established a central role of OPN in maintaining both calcium-phosphate and calcium-oxalate solubility in urine (7–9), a site where mineral concentrations commonly exceed their supersaturation threshold (2,8). Macrophages appear to play a vital role in nanocrystal clearance from the kidney (29–31); thus, it is plausible that OPN may assist in mediating macrophage recognition of early mineral aggregates that form in tubular fluid or are endocytosed by tubular epithelial cells. However, our current studies do not support tubular OPN expression as a sole trigger for macrophage recruitment to the kidney because kidneys harvested from mice undergoing prior unilateral nephrectomy demonstrated a clear increase of OPN protein expression compared with sham controls (Figure 3, C–F) but no evidence of kidney macrophage accumulation by either IHC staining (not shown) or gene expression for Adgre1 (F4/80), an established macrophage marker (Figure 3K). Likewise, Spp1 (OPN) null mice with CKD demonstrated no obvious difference in kidney Adgre1 (F4/80) gene expression compared with WT CKD mice (Figure 4G).

Evidence from prior studies has shown tubular phosphate concentrations to far exceed their supersaturation point in residual nephrons in CKD (2,3). In line with the known role of OPN for increasing urine mineral solubility (9), we hypothesized that increased OPN production by tubular epithelial cells in CKD kidneys represents an important evolutionary response to facilitate tubular phosphate solubility and excretion when tubular phosphate concentrations are forced to exceed their supersaturation point to maintain systemic phosphate balance. Our first notable finding in support of this theory was a generalized upregulation of OPN production by tubular epithelial cells across all studied CKD murine models, including models of polycystic kidney disease (pcy/pcy), glomerulonephritis (Col4a3−/−), and chronic tubulointerstitial nephritis (aristolochic acid; Figure 1). Moreover, we found residual kidneys from mice with prior unilateral nephrectomy exhibited increased OPN expression compared with sham-operated mice (Figure 3), suggesting that reduced nephron numbers alone (in the absence of tubular injury) can trigger early OPN production by residual nephrons.

Renal OPN production appears to be regulated by a multitude of stimuli, including the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and hormonal regulators of mineral metabolism (32,33). Given the importance of OPN in maintaining mineral solubility in tubular fluid, we speculated that an additional regulator of kidney OPN production may be phosphate or phosphate-based nanocrystal formation. In support of this potential relationship, a prior study found phosphate to stimulate OPN production by cultured osteoblasts directly (34). Moreover, we previously found WT mice consuming a high-phosphate diet to exhibit increased concentrations of urine OPN (16). From an evolutionary standpoint, it seems logical that elevated mineral concentrations in tubular fluid would be an important trigger for enhancing the production of factors that are critical for maintaining mineral solubility in tubular fluid. Thus, we theorized that high concentrations of tubular phosphate itself may be an important stimulus for OPN production in the kidney. In agreement with this theory, we found two separate phosphaturic murine models to demonstrate enhanced kidney OPN production (Figure 5, A–F), suggesting that tubular fluid phosphate may be a direct stimulus for tubular epithelial cell OPN production. Because phosphaturic mice and unilateral nephrectomy mice likely both exhibit increased tubular fluid flow (from either decreased proximal tubule sodium reabsorption or hyperfiltration, respectively), it is plausible that enhanced tubular fluid flow through residual nephrons could be an additional driver of OPN production in our models and in CKD. In support of such a mechanism, prior in vitro studies using both cultured tubular epithelial cells and osteoblasts showed that either increased fluid flow or mechanical force could directly stimulate OPN production by these cell lines (35,36).

Consistent with prior in vitro studies showing ASARM peptides can significantly enhance mineral solubility in solution, our current experiments confirm the ASARM peptide motif to be critical for maintaining mineral solubility in urine. As such, targeted neutralization of this ASARM sequence with SPR4 peptide in phosphaturic mice (Figure 4) recapitulated our observations in global OPN null mice with CKD (Figure 5). We cannot eliminate the possibility that the nephrocalcinosis phenotype seen in SPR4-treated mice was related to neutralization of either free ASARM peptides or the ASARM motif of other SIBLING proteins; however, the similarity between the phenotypes observed in these separate experiments suggests a substantial contribution of OPN-derived ASARM in mediating this finding. We speculate that the difference in the pattern of calcification observed in the adenine diet and aristolochic acid models likely resulted from the proximal tubule deposition of adenine crystals serving as a nidus for mineral attachment in the cortical regions of the kidney. The medullary pattern of nephrocalcinosis observed in aristolochic acid and SPR4-treated mice is more consistent with what would be expected under normal physiologic conditions where tubular mineral content would be dramatically increased in more distal tubular segments where final water reabsorption leads to a substantial increase in the concentration of tubular phosphate (2).

The current investigation has both important strengths and limitations. Strengths of this work include performing experiments in multiple CKD models to demonstrate that our findings are not specific to any single CKD rodent model, use of micro-computed tomography imaging to perform precise total kidney quantification of mineral content, data from two separate phosphaturic murine models to provide in vivo mechanistic insight into the role of phosphaturia in kidney OPN production, the inclusion of confirmatory studies demonstrating that direct inhibition of the ASARM peptide motif can recapitulate our observations with global OPN deficiency, and the conduction of cell culture studies to determine the direct effect of calcium-phosphate nanocrystals on OPN expression by tubular epithelial cells. Important limitations include a potential difference in the biologic pathways regulating urine mineral solubility in mice and humans, the use of a global OPN-deficient mouse makes us unable to ascribe our nephrocalcinosis phenotype definitively to reduced kidney-specific OPN expression, and no examination of how OPN deficiency or SPR4 neutralization affects long-term renal outcomes in our models.

The current investigation represents an important advancement in our understanding of the biologic processes regulating mineral solubility in CKD and establishes OPN as a central contributor to this process. Although prior investigations have described renal OPN as a contributor to kidney injury and CKD progression through its actions to promote local inflammation and fibrosis, we postulate that these tissue effects are a downstream consequence of the important evolutionary role of OPN to maintain mineral solubility in tubular fluid when functional nephron numbers become substantially reduced. Given the known role of immune cells in facilitating nanocrystal clearance from the kidney, any proinflammatory effects of OPN may simply represent another long-term “trade-off” for facilitating the immediate clearance of early mineral aggregates under conditions of extreme mineral burden to residual nephrons. Future studies should help further delineate the role of urinary phosphate as a promoter of kidney inflammation and fibrosis and decipher the precise role of kidney OPN expression as an intermediary in these processes.

Disclosures

J. Boulanger reports being an employee of Sanofi-Genzyme. S. Liu reports being an employee of Sanofi-Genzyme and ownership interest in Sanofi. P.S. Rowe reports ownership interest in Apple (AAPL), CYBL, DWAC, and RTX, and patents or royalties from the University of Kansas Medical Center. J.R. Stubbs reports consultancy agreements with Novadiol; research funding from Genzyme; and being a scientific advisor for Spectradyne LLC. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was partially supported by funds from the Kansas PKD Research and Translation Core Center (P30DK106912 to J.R. Stubbs), a National Institutes of Health (NIH) NIGMS and NIDDK grant (R01DK122212 to J.R. Stubbs), a PKD Foundation research grant (to T.A. Fields), and an NIH NIDDK grant (R01DK111693 to P.S. Rowe).

Footnotes

See related editorial, “Osteopontin Regulates Phosphate Solubility to Prevent Mineral Aggregates in CKD,” on pages 1477–1479.

Author Contributions

J. Boulanger, T.A. Fields, K.P. Jansson, S. Liu, P.S. Rowe, J.R. Stubbs, and S. Zhang were responsible for the investigation; J. Boulanger, K.P. Jansson, P.S. Rowe, J.R. Stubbs, and S. Zhang were responsible for data curation; T.A. Fields, K.P. Jansson, S. Liu, P.S. Rowe, J.R. Stubbs, and S. Zhang were responsible for methodology; T.A. Fields, K.P. Jansson, S. Liu, J.R. Stubbs, and S. Zhang were responsible for formal analysis; S. Liu, P.S. Rowe, and J.R. Stubbs were responsible for supervision and reviewed and edited the manuscript; S. Liu, P.S. Rowe, J.R. Stubbs, and S. Zhang were responsible for conceptualization; J.R. Stubbs was responsible for funding acquisition and project administration and wrote the original draft of the manuscript; S. Zhang was responsible for validation; and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://kidney360.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.34067/KID.0007352021/-/DCSupplemental.

Download Supplemental Methods, PDF file, 182 KB (181.1KB, pdf) .

References

- 1.Moe S, Drüeke T, Cunningham J, Goodman W, Martin K, Olgaard K, Ott S, Sprague S, Lameire N, Eknoyan G; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) : Definition, evaluation, and classification of renal osteodystrophy: A position statement from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Kidney Int 69: 1945–1953, 2006. 10.1038/sj.ki.5000414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bank N, Su WS, Aynedjian HS: A micropuncture study of renal phosphate transport in rats with chronic renal failure and secondary hyperparathyroidism. J Clin Invest 61: 884–894, 1978. 10.1172/JCI109014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craver L, Marco MP, Martínez I, Rue M, Borràs M, Martín ML, Sarró F, Valdivielso JM, Fernández E: Mineral metabolism parameters throughout chronic kidney disease stages 1–5—Achievement of K/DOQI target ranges. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1171–1176, 2007. 10.1093/ndt/gfl718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isakova T, Wahl P, Vargas GS, Gutiérrez OM, Scialla J, Xie H, Appleby D, Nessel L, Bellovich K, Chen J, Hamm L, Gadegbeku C, Horwitz E, Townsend RR, Anderson CA, Lash JP, Hsu CY, Leonard MB, Wolf M: Fibroblast growth factor 23 is elevated before parathyroid hormone and phosphate in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 79: 1370–1378, 2011. 10.1038/ki.2011.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie Y, Sakatsume M, Nishi S, Narita I, Arakawa M, Gejyo F: Expression, roles, receptors, and regulation of osteopontin in the kidney. Kidney Int 60: 1645–1657, 2001. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00032.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sørensen ES, Højrup P, Petersen TE: Posttranslational modifications of bovine osteopontin: Identification of twenty-eight phosphorylation and three O-glycosylation sites. Protein Sci 4: 2040–2049, 1995. 10.1002/pro.5560041009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoyer JR, Asplin JR, Otvos L: Phosphorylated osteopontin peptides suppress crystallization by inhibiting the growth of calcium oxalate crystals. Kidney Int 60: 77–82, 2001. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00772.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schlieper G, Westenfeld R, Brandenburg V, Ketteler M: Inhibitors of calcification in blood and urine. Semin Dial 20: 113–121, 2007. 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00257.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wesson JA, Johnson RJ, Mazzali M, Beshensky AM, Stietz S, Giachelli C, Liaw L, Alpers CE, Couser WG, Kleinman JG, Hughes J: Osteopontin is a critical inhibitor of calcium oxalate crystal formation and retention in renal tubules. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 139–147, 2003. 10.1097/01.ASN.0000040593.93815.9D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paloian NJ, Leaf EM, Giachelli CM: Osteopontin protects against high phosphate-induced nephrocalcinosis and vascular calcification. Kidney Int 89: 1027–1036, 2016. 10.1016/j.kint.2015.12.046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beck L, Karaplis AC, Amizuka N, Hewson AS, Ozawa H, Tenenhouse HS: Targeted inactivation of Npt2 in mice leads to severe renal phosphate wasting, hypercalciuria, and skeletal abnormalities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95: 5372–5377, 1998. 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo J, Song W, Boulanger J, Xu EY, Wang F, Zhang Y, He Q, Wang S, Yang L, Pryce C, Phillips L, MacKenna D, Leberer E, Ibraghimov-Beskrovnaya O, Ding J, Liu S: Dysregulated expression of microRNA-21 and disease-related genes in human patients and in a mouse model of Alport syndrome. Hum Gene Ther 30: 865–881, 2019. 10.1089/hum.2018.205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin A, David V, Laurence JS, Schwarz PM, Lafer EM, Hedge AM, Rowe PS: Degradation of MEPE, DMP1, and release of SIBLING ASARM-peptides (minhibins): ASARM-peptide(s) are directly responsible for defective mineralization in HYP. Endocrinology 149: 1757–1772, 2008. 10.1210/en.2007-1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mortazavi A, Williams BA, McCue K, Schaeffer L, Wold B: Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nat Methods 5: 621–628, 2008. 10.1038/nmeth.1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stubbs JR, He N, Idiculla A, Gillihan R, Liu S, David V, Hong Y, Quarles LD: Longitudinal evaluation of FGF23 changes and mineral metabolism abnormalities in a mouse model of chronic kidney disease. J Bone Miner Res 27: 38–46, 2012. 10.1002/jbmr.516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.David V, Martin A, Hedge AM, Drezner MK, Rowe PS: ASARM peptides: PHEX-dependent and -independent regulation of serum phosphate. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F783–F791, 2011. 10.1152/ajprenal.00304.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Min W, Shiraga H, Chalko C, Goldfarb S, Krishna GG, Hoyer JR: Quantitative studies of human urinary excretion of uropontin. Kidney Int 53: 189–193, 1998. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00745.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lopez CA, Hoyer JR, Wilson PD, Waterhouse P, Denhardt DT: Heterogeneity of osteopontin expression among nephrons in mouse kidneys and enhanced expression in sclerotic glomeruli. Lab Invest 69: 355–363, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scatena M, Liaw L, Giachelli CM: Osteopontin: A multifunctional molecule regulating chronic inflammation and vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 2302–2309, 2007. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.144824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liaw L, Lindner V, Schwartz SM, Chambers AF, Giachelli CM: Osteopontin and beta 3 integrin are coordinately expressed in regenerating endothelium in vivo and stimulate Arg-Gly-Asp-dependent endothelial migration in vitro. Circ Res 77: 665–672, 1995. 10.1161/01.RES.77.4.665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang H, Guo M, Chen JH, Wang Z, Du XF, Liu PX, Li WH: Osteopontin knockdown inhibits αv, β3 integrin-induced cell migration and invasion and promotes apoptosis of breast cancer cells by inducing autophagy and inactivating the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem 33: 991–1002, 2014. 10.1159/000358670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lancha A, Rodríguez A, Catalán V, Becerril S, Sáinz N, Ramírez B, Burrell MA, Salvador J, Frühbeck G, Gómez-Ambrosi J: Osteopontin deletion prevents the development of obesity and hepatic steatosis via impaired adipose tissue matrix remodeling and reduced inflammation and fibrosis in adipose tissue and liver in mice. PLoS One 9: e98398, 2014. 10.1371/journal.pone.0098398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.López B, González A, Lindner D, Westermann D, Ravassa S, Beaumont J, Gallego I, Zudaire A, Brugnolaro C, Querejeta R, Larman M, Tschöpe C, Díez J: Osteopontin-mediated myocardial fibrosis in heart failure: A role for lysyl oxidase? Cardiovasc Res 99: 111–120, 2013. 10.1093/cvr/cvt100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, Lopategi A, Ge X, Lu Y, Kitamura N, Urtasun R, Leung TM, Fiel MI, Nieto N: Osteopontin induces ductular reaction contributing to liver fibrosis. Gut 63: 1805–1818, 2014. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giachelli CM, Lombardi D, Johnson RJ, Murry CE, Almeida M: Evidence for a role of osteopontin in macrophage infiltration in response to pathological stimuli in vivo. Am J Pathol 152: 353–358, 1998 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liaw L, Birk DE, Ballas CB, Whitsitt JS, Davidson JM, Hogan BL: Altered wound healing in mice lacking a functional osteopontin gene (spp1). J Clin Invest 101: 1468–1478, 1998. 10.1172/JCI2131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okada H, Moriwaki K, Kalluri R, Takenaka T, Imai H, Ban S, Takahama M, Suzuki H: Osteopontin expressed by renal tubular epithelium mediates interstitial monocyte infiltration in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 278: F110–F121, 2000. 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.1.F110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu XQ, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Mu W, Giachelli CM, Atkins RC, Johnson RJ, Lan HY: A functional role for osteopontin in experimental crescentic glomerulonephritis in the rat. Proc Assoc Am Physicians 110: 50–64, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taguchi K, Okada A, Kitamura H, Yasui T, Naiki T, Hamamoto S, Ando R, Mizuno K, Kawai N, Tozawa K, Asano K, Tanaka M, Miyoshi I, Kohri K: Colony-stimulating factor-1 signaling suppresses renal crystal formation. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 1680–1697, 2014. 10.1681/ASN.2013060675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xi J, Chen Y, Jing J, Zhang Y, Liang C, Hao Z, Zhang L: Sirtuin 3 suppresses the formation of renal calcium oxalate crystals through promoting M2 polarization of macrophages. J Cell Physiol 234: 11463–11473, 2019. 10.1002/jcp.27803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taguchi K, Okada A, Hamamoto S, Unno R, Moritoki Y, Ando R, Mizuno K, Tozawa K, Kohri K, Yasui T: M1/M2-macrophage phenotypes regulate renal calcium oxalate crystal development. Sci Rep 6: 35167, 2016. 10.1038/srep35167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yu XQ, Wu LL, Huang XR, Yang N, Gilbert RE, Cooper ME, Johnson RJ, Lai KN, Lan HY: Osteopontin expression in progressive renal injury in remnant kidney: Role of angiotensin II. Kidney Int 58: 1469–1480, 2000. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00309.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noda M, Vogel RL, Craig AM, Prahl J, DeLuca HF, Denhardt DT: Identification of a DNA sequence responsible for binding of the 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 receptor and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 enhancement of mouse secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP-1 or osteopontin) gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87: 9995–9999, 1990. 10.1073/pnas.87.24.9995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beck GR Jr, Zerler B, Moran E: Phosphate is a specific signal for induction of osteopontin gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97: 8352–8357, 2000. 10.1073/pnas.140021997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diamond JR, Kreisberg R, Evans R, Nguyen TA, Ricardo SD: Regulation of proximal tubular osteopontin in experimental hydronephrosis in the rat. Kidney Int 54: 1501–1509, 1998. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.You J, Reilly GC, Zhen X, Yellowley CE, Chen Q, Donahue HJ, Jacobs CR: Osteopontin gene regulation by oscillatory fluid flow via intracellular calcium mobilization and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase in MC3T3-E1 osteoblasts. J Biol Chem 276: 13365–13371, 2001. 10.1074/jbc.M009846200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Download Supplemental Methods, PDF file, 182 KB (181.1KB, pdf) .