Abstract

Introduction

The use of weapons of mass destruction against civilian populations is of serious concern to public health authorities. Chemical weapons are of particular concern. A few studies have investigated medical responses in prehospital settings in the immediate aftermath of a chemical attack, and they were limited by the paucity of clinical data. This study aims to describe the acute management of patients exposed to a chemical attack from the incident site until their transfer to a medical facility.

Methods and analysis

This international multicentric observational study addresses the period from 1970 to 2036. An online electronic case report form was created to collect data; it will be hosted on the Biomedical Telematics Laboratory Platform of the Quebec Respiratory Health Research Network. Participating medical centres and their clinicians are being asked to provide contextual and clinical information, including the use of protective equipment and decontamination capabilities for the medical evacuation of the patient from the incident site of the chemical attack to the moment of admission at the medical facility. In brief, variables are categorised as follows: (1) chemical exposure (threat); (2) prehospital and hospital/medical facility capabilities (staffing, first aid, protection, decontamination, disaster plans and medical guidelines); (3) clinical interventions before hospital admission, including the use of protection and decontamination and (4) outcomes (survivability vs mortality rates). Judgement criteria focus on decontamination drills applied to any of the patient’s conditions.

Ethics and dissemination

The Sainte-Justine Research Centre Ethics Committee approved this multicentric study and is acting as the main evaluating centre. Study results will be disseminated through various means, including conferences, indexed publications in medical databases and social media.

Trial registration number

Keywords: ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, EPIDEMIOLOGY, FORENSIC MEDICINE, PUBLIC HEALTH, TRAUMA MANAGEMENT, TOXICOLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

The pioneering methods used in the measurement of medical responses in the contaminated area after a chemical attack—a topic that, to date to our knowledge, has not been studied thoroughly. The zone of interest consists of the interventions taking place in prehospital settings, beginning at the incident site and ending at the patient’s transfer to a clean zone.

The interventions assessed in this study are based on three key integrated competences, namely, (1) protection (for the staff and the patients), (2) decontamination (immediate and specialised (medical decontamination)) and (3) medical interventions.

The inclusion of both civilian and military healthcare resources in the study.

Issues raised by authorities around the world restricting access to data may adversely affect this study.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, a staggering chain of epidemics and intermittent CBRNE incidents has captured the world’s attention.1 If anything, events like the Syrian chemical warfare, Russia’s alleged use of Novichok in her spy games with the West, and the COVID-19 pandemic have neutralised the ‘alarming level of ignorance’ among civilians and the broader scientific community regarding the existence and capabilities of non-nuclear weapons of mass destruction (WMD).2 In an era of cognitive and hybrid warfare,3–8 the subtle and subversive use of WMD—and especially of chemical and biological agents—against military targets and civilian populations is likely to become the rule rather than the exception.

The use of WMD is of serious concern to civilian and military health authorities around the world.9–13 A large number of chemical agents, each with its own characteristics, including symptom onset (from seconds to hours) and contamination modalities (inhalation; ingestion; skin penetration) can be used in terrorist attacks, war, etc.12–30 Such threats require health organisations to be ever more prepared to manage patients exposed to WMD.31–38

The literature on the way prehospital clinical management of casualties is conducted during CBRNE events reveals several deficiencies concerning elements such as clinical protocols, work environments, and protection and decontamination capabilities. These range from the lack of accurate medical information and the inclusion of outdated information to the absence of medical gold standards for medical evacuations in prehospital settings (eg, using oxygen safely, efficient airway management).12 16 19–30 39–48 On the one hand, it has been noted that scientific publications did not address medical guidelines employed in actual acute settings conditions (ie, in real-life conditions). In the literature, mentions of clinical means in acute settings appeared to be limited to medical countermeasures capabilities (eg, HI-6/atropine and diazepam self-injectors for nerve agent exposures), which are only held by military and security forces and not by hospitals or pharmacies.12 16 19–30 39–48 On the other hand, a review of the literature revealed that most studies involved clinical interventions taking place after the patient had already been admitted to the hospital or medical facility.12 16 19–30 39–48

A recent systematic review49 assessing past medical responses in prehospital settings after chemical attacks50–53 constitutes one study,49 confirming the existence of these gaps and standardisation issues in clinical care, as well as in protection12–15 17–30 39–41 49 54–56 and decontamination capabilities12–15 17–30 39–41 49 54–56 for both patients and staff. These deficiencies are directly related to the medical extraction of casualties exposed to chemical attacks from the incident site to the point of transfer to a medical facility (ie, acute settings), which the systematic review also revealed to be an area that has hardly been studied.49

Given the scarcity of information regarding validated medical response data in acute settings,49 it is necessary to conduct studies on medical responses during a CBRNE event, starting with chemical exposures.

Aim

The aim of this multicentric observational study is to describe the acute medical management of patients wounded in a chemical event during their medical extraction to medical facilities.

Objectives

The first objective of the study is to retrospectively describe the three following interrelated competences during a medical extraction: (1) the use of protection capabilities for staff and patients, (2) the use of decontamination capabilities for staff and patients (levels: immediate and specialised) and (3) medical treatments provided.

The second objective is to collect any existing protocols and guidelines established by the concerned authorities that would form part of their disaster plan in the event of a chemical attack causing mass casualties, and to retrospectively compare them with what happened in real-life conditions.

Research questions

The research questions are: (1) What integrated protection capability was used in medical interventions? (2) What integrated decontamination capability was used in medical interventions? (3) What medical treatments did clinicians provide in acute settings (airway, breathing and circulation management; pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical products; medical technologies)? and (4) If algorithms such as protocols and guidelines were developed, how were they applied in emergency settings?

Methods and analysis

Study design

This is an ongoing multicentric observational study in which the assessment of the medical response to chemical attacks is conducted retrospectively over two distinct periods. The first is for events that occurred in the past five (5) decades (1970–2020). The second is for future chemical attacks that may occur within the next 15 years (2021–2036). Of note, the data collection will be performed retrospectively and after a participating medical centre receives approval by an ethics review board (ERB) (see the Ethics and dissemination, ethics approval, amendment and governance section).

Eligible chemical events

The eligibility of a chemical attack requires that it: (1) be confirmed either by the governmental authority of the attacked country or/and by at least one medical authority related to the attacked country, such as the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), Doctors Without Borders, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR); (2) be confirmed by an institution relying on security intelligence sources such as the WHO, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, etc and (3) occurred between January 1970 and December 2036.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for participating Institutions/centres

Inclusion criteria are:

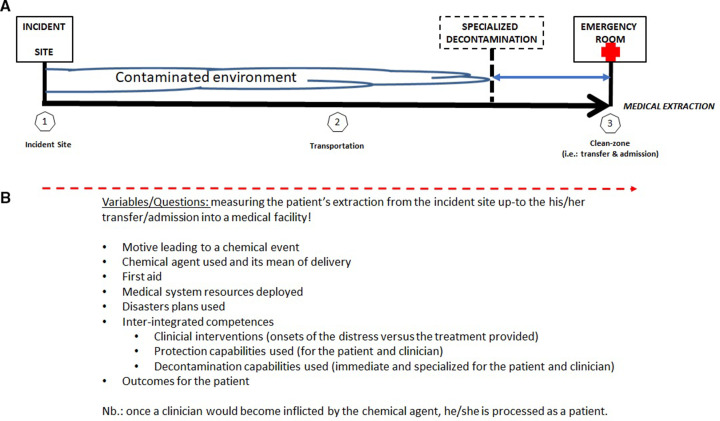

The chemical attack caused at least one casualty who required the assistance of the participating healthcare system (eg, physicians, nurses, paramedics and other healthcare specialists of a medical facility) during a medical extraction from the incident site until admission to a medical facility (figure 1).

Patients are eligible if they were exposed to the chemical attack.

Medical information concerning the chemical exposures, even if partial, is accessible to healthcare professionals for the purposes of filling out the online electronic case report form (eCRF).

Participants must be able to complete the online eCRF in English.

The approval of an ERB is obtained by each medical centre participant.

Figure 1.

Illustration summarising the medical extraction and the zone of interest. This illustration summarises the medical extraction and the study’s zone of interest, which begins at the incident site and ends when the patient is transferred and admitted to the emergency room or its equivalent (eg, a walk-in clinic). Part A. Step 1: patient management begins, step 2: transportation to the medical facility and step 3: patient admission to the emergency room. This is also the point at which continuity of care will normally proceed in a clean zone after patient decontamination. Ideally, the specialised decontamination facility will be located such that the patient will have been decontaminated prior to reaching the hospital. For that reason, it is represented by dashed lines. Emergency services found in cities that have such specialised assets may also have a specialised medical decontamination line that has the highest level of expertise to deal with injured, unconscious and deteriorating patients while they are being processed for a transfer to a clean zone. Part B: illustrates the correspondence between the detection of the patient’s clinical presentation and the medical response during the entire medical extraction. Part C: illustrates the frequency of patient monitoring.

Exclusion criteria: a negative response to any of the inclusion criteria results in an exclusion.

Target population and recruitment

Populations being studied include all individuals linked to a chemical event/attack who were affected by a chemical agent and needed the intervention of their local healthcare system (including anyone who was exposed and turned to a medical organisation for help sometime after an attack). As a third party recruited for this study, participating medical facilities that treated at least one patient will be responsible to make the selection based on the inclusion criteria and to anonymously manage clinical information for processing into the study eCRF.

Sample size calculation

As this is an observational study, there is no limitation on the number of patients that can be included per chemical event. In table 1, known chemical events that caused numerous casualties are shown. In other words, since a chemical attack/event may result in very few to hundreds of casualties, the sample size will vary accordingly.

Table 1.

Summary of past chemical exposures that have, to date, resulted in victims12 14 49 52 59–70

| Incident name | N | Chemical agent | Country | Year |

| Markov’s case | 1 | Ricin (toxin) | United Kingdom | 1979 |

| Aum Shinrikyo’s first attempt (Matsumoto) | >100 | Sarin (nerve agent) | Japan | 1994 |

| Aum Shinrikyo’s second attempt (Tokyo) | >1000 | Sarin | Japan | 1995 |

| Iran-Iraq war | >1000 | Mustard gas, cyclosarin, sarin, hydrogen cyanide, tabun* | Iraq | 1980–1988 |

| Syrian Regime | >100 | Mustard gas, chlorine, sarin | Syria | 2014 |

| ISIL, attack in Syria | >100 | Mustard gas, sarin, chlorine, phosphine | Syria | 2015 |

| ISIL, Iraq campaign | >100 | Mustard gas, chlorine, phosphine | Iraq | 2015 |

| Kim Jong-nam | >1 | VX (nerve agent) | Malaysia | 2017 |

| Salisbury attack | 3 | Novichok (nerve agent) | United Kingdom | 2018 |

| Amesbury | 1 | Novichok (nerve agent) | United Kingdom | 2018 |

Note. During this study, the electronic case report form will help rectify some basic facts about the use of chemical weapons in cases where disparities are found in different literature sources (https://cbrne-obs-ltb.cred.ca/; a product of the Biomedical telematics Laboratory: https://rsr-qc.ca/en/ltb/). For instance, Schulz-Kirchrath14 reported that Tabun was used during the Iran-Iraq war (*) while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) speculated about its use.69 Moreover, CDC also reported that VX was probably used during this same conflict.70

Where a participating medical centre managed numerous patients, the clinician representing the centre will determine the number of cases to be reported according to two factors: (1) data accessibility and (2) the burden associated with the task of completing the eCRF for each patient meeting the study criteria. Participating centres or clinicians will be requested to provide data on as many patients as they can. Given the chaotic nature of mass casualty events, data may be lost or incomplete. Participating centres are nevertheless encouraged to provide the data available for each patient.

Data collection and measurements

Data collection, quality, validation

Participating medical centres/clinicians are to use each patient’s medical chart to enter data into the study online eCRF. For data collection purposes, the eCRF is accessible through a secure website hosted on the Biomedical Telematics Laboratory Platform of the Quebec Respiratory Health Research Network. The link is only sent to designated staff at participating centres that have obtained ERB approval. Six data gathering categories comprise the eCRF. These are: (1) overview of the chemical attack; (2) deployment of resources; (3) hospital emergency room area; (4) patient information (including rescuers, first responders and clinicians suffering from secondary exposure effects); (5) medical extraction and interventions and (6) outcomes (survivability vs mortality rates). The healthcare and medical facility information section is composed of the following: (1) the clinical presentation; (2) treatments and (3) patient monitoring frequency. The latter is measured throughout the chemical attack casualty’s complete medical management starting at the incident site, and continuing during the medical evacuation and emergency room interventions (figure 1). Information will also be collected about the use of disaster plans (ie, how the medical authorities planned to respond to a chemical attack and what literature and references they relied on). Participating medical centre clinicians will be trained on a demonstration version of the eCRF before they begin entering data into the operational version (Demo: https://cbrne-obs-demo-ltb.cred.ca/; Operational: https://cbrne-obs-ltb.cred.ca/). Members of the study team will routinely validate the data entered in the eCRF. They will also answer questions and address any issues raised by participating medical centres and clinicians. However, a residual information bias cannot be excluded as an independent data quality assurance and validation on each participating site will not be performed. This limitation will be addressed in the final publication once the study has ended.

Other eCRF specifications

The eCRF is an interactive web-based platform developed and implemented by the Laboratoire Télébiomédical (LTB) du Réseau en santé respiratoire du Québec du Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé (Biomedical Telematics Laboratory: https://rsr-qc.ca/en/ltb/). The LTB has expertise in the development of such tools.57 58 Each participant recruited remotely inputs data into the eCRF under a personal profile that is protected by an encrypted password. Before an eCRF can be submitted, a number of mandatory questions must be answered. In addition, certain eCRF fields have answer options that allow for reporting that data are missing or non-existent. This makes it possible to assign a numerical value when assessing information gaps. All protected health and event-related information is stored in a secure location of the LTB. Epiconcept was certified as a Health Data Host on 19 April 2019, and the certification applies to the eCRF.

Criterion of primary judgement

The number of patients reported as wounded by a chemical weapon on whom a minimum of one decontamination procedure was performed before admission to the medical centre.

Criteria of secondary judgement

Four secondary judgement, criteria are defined as follows:

The percentage of patients wearing protective equipment on whom a minimum of one decontamination procedure was performed and who did not experience any distress event requiring at least one medical treatment during medical extraction from the incident site to their admission at the hospital emergency room or its equivalent (ie, endpoint of the medical extraction/evacuation).

The percentage of patients wearing protective equipment on whom a minimum of one decontamination procedure was not performed and who experienced at least one distress event requiring at least one medical treatment during medical extraction from the incident site to their admission at the hospital emergency room or its equivalent (ie, endpoint of the medical extraction/evacuation).

The percentage of decontaminated patients who did not experience any distress requiring a treatment and who wore protective equipment during a medical extraction until their admission at the hospital emergency room or its equivalent (ie, endpoint of the medical extraction/evacuation).

The percentage of decontaminated patients who experienced a minimum of one distress event for which they received at least one treatment, and who did not wear any protective equipment during a medical extraction until their admission at the hospital emergency room or its equivalent (ie, endpoint of the medical extraction/evacuation).

Patient and public involvement

There has been no patient or public involvement in the design, recruitment, conduct, interpretation and dissemination of this study’s results.

Biostatistical analysis

Continuous variables will be reported as mean±SD or median with IQR, including proportion, frequency and mode, according to the variable distributions. The normality assumption/distribution will be verified with the Shapiro-Wilk tests. Nominal variables will be reported as frequencies. Analyses will be conducted with the latest version of IBM SPSS Statistics Software or its equivalent in due time (SPSS; https://www.ibm.com/analytics/spss-statistics-software; Last accessed: 24 August 2022).

Impact of this study

It is anticipated that the results of this study will have the following impacts. It will:

Highlight the strengths of participating healthcare facilities in the medical management of chemically exposed patients.

Reveal gaps in the capability of participating healthcare facilities in the medical management of chemically exposed patients, thereby contributing to the optimisation of clinical standards and resource management during CBRNE incidents.

Demonstrate the need for future studies, including politicised cases where access to classified information will be required.

Pave the way for the implementation of a research programme in Chemical, Biological, Radiological, Nuclear, Explosive (CBRNE) defence through which medical algorithms and technologies for use by medical clinicians will be developed to address identified gaps.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval, amendment and governance

In order to conduct research involving human subjects, the approval of the Sainte-Justine Research Centre Ethics Committee was required. In March 2021, the committee approved the final amendment to the study plan (registration number 2020–2561). This amendment extended the study period to include future chemical attacks that will be analysed retrospectively. The solicitation of international medical centres and organisations as participants has begun since 2020 with the study’s initial approval obtained. A similar solicitation effort will be undertaken for future chemical attacks. The addition of medical centres or clinicians as future participants will require the approval of their ERB and a signed document formalising an interinstitutional agreement.

In circumstances where ethical review board approval would be difficult to obtain, such as a civil war, etc, options have been developed. The first will come into play once the country becomes stable with a legitimate government after a period of political instability (eg, civil war). In that case, medical centres will be solicited. The second, currently underway, is to solicit international organisations deployed in an unstable country to provide medical care to the civilian population. Examples of these organisations are the ICRC, Doctors Without Borders, the UNHCR, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. The participation of these organisations will require the approval of their respective ERB or a third-party organisation experienced in scientific study projects capable of providing such approval. Finally, the third option will be to conduct an interview directly with the patient via telemedicine (eg, Microsoft Teams). In such cases, a patient’s signed consent will need to be kept on record at Sainte-Justine University Hospital Research Centre’s medical archive department. When a medical centre or an international organisation does not have an ERB, ethics approval will need to be obtained from a third-party organisation, as suggested for option 2 (ie, a third-party organisation experienced in scientific study projects capable of providing such approval). However, in case of other obstacles, the matter will be referred to legal authorities in order to determine a suitable course of action. Finally, Sainte-Justine’s ERB overseeing the study will regularly be kept informed as to the use of this last option.

Dissemination

Results will be presented in conferences as well as published in peer-reviewed medical journals. The paper will also be advertised on social media. Since this paper will be published in open access, the public can acquire it freely.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Nadine Laflamme, Medical Intelligence CBRNE, for her administrative support, and to Eve Baribeau Marchand, University of Montreal library services, for her outstanding services. The authors also acknowledge Dr Maude St-Onge, MD for her contribution to the development of the study protocol.

Footnotes

Contributors: Study concept and design: SB, JL, PJ.Data acquisition: SB, JR, AK, DB, FL, YF, MD, PJ. Study validation: SB, MD, SS, PJ, JL. Data analysis and interpretation: SB, JR, MD, DB, YF, MD, JL, PJ. Drafting of the manuscript: SB. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: SB, DN, FL, HI, SS, JL, PJ. Study supervision: JL, PJ. Accountability: PJ, JC and SB took responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis. The lead author (PJ) affirmed that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported, and that no important aspects of the study have been omitted.

Funding: This work was supported in part by the Quebec Respiratory Health Research Network through the award of a $6,000 grant from its 2021 to 2023 funding programme (2021–2023 Use of QRHN Platforms Program, JL). Medical Intelligence CBRNE (also known as MEDINT CBRNE Group) donated US$2000 (no grant number) as a scientific entrepreneurship initiative. Other expenses were covered by PJ’s scientific research funds from the Quebec Ministry of Health and Sainte-Justine Hospital (no grant number, funds assigned to PJ to manage). Maintenance funding for the eCRF will be provided by Stephane Bourassa on an annual basis via his research funds. Each MEDINT CBRNE Group member provided their expertise to this study at no cost. No financial compensation will be provided to health care professionals. However, participants will receive full professional recognition by being listed as collaborators in this study.

Disclaimer: Funding sources played no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the drafting of the report; or the decision to submit this article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare that no commercial or governmental funding sponsored this project. Jacinthe Leclerc (JC), Philippe Jouvet (PJ), Stephane Bourassa (SB) and Marc Dauphin (MD) have no financial interests that are relevant to the submitted work. Medical Intelligence CBRNE Inc. (also known as MEDINT CBRNE Group) provided a donation for the creation of eCRF. Although SB and MD are MEDINT CBRNE Group founders and shareholders, they have no current financial interests relevant to the submitted work. MEDINT CBRNE Group is a start-up company that was established in 2017 with support from university entrepreneurship services (Laval and Montreal) and the Prince’s Trust Canada (https://www.princesoperationentrepreneur.ca/). The military expertise that has shaped MEDINT CBRNE Group was developed while serving in the Canadian Armed Forces.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Council of the European Union . European security strategy – a secure Europe in a better world. public information department of the communication unit in Directorate-General f. General. Secretariat of the Council. Brussels (Belgium): European Communities, 2009: 50. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/30823/qc7809568enc.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alibek K, Handleman S. Biohazard – the chilling true story of the largest covert biological weapons program in the world – ToId from the inside by the man who Ran it. New York (United States): Random House, 1999: 333. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nichsr/esmallpox/biohazard_alibek.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) . Cognitive warfare brings the new third operational dimension, besides the cyber and the physical ones. How should NATO adjust to it and face the challenges that come with it? 2002 innovation hub. NATO allied command transformation. website Blog. Available: https://www.innovationhub-act.org/content/cognitive-warfare [Accessed 24 Aug 2022].

- 4.Department of National Defence . Strong, Secure, Engaged Canada’s Defence Policy. Government of Canada. Ottawa (Canada); 2017. 113 pages. Catalog Number D2-386/2017E. ISBN 978-0-660-08443-5. Available: http://dgpaapp.forces.gc.ca/en/canada-defence-policy/docs/canada-defence-policy-report.pdf [Accessed 24 Aug 2022].

- 5.Monaghan S, Cullen P, Wegge N. MCDC Countering hybrid warfare project: Countering hybrid warfare. multinational capability development campaign. London (United Kingdom): The Government of the United Kingdom, 2019: 92. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/784299/concepts_mcdc_countering_hybrid_warfare.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bilal A. A. hybrid warfare – new threats, complexity, and trust as the antidote. Webpage NATO review. North Atlantic Treaty organization (NATO), 2021. Available: https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2021/11/30/hybrid-warfare-new-threats-complexity-and-trust-as-the-antidote/index.html

- 7.Duyeon K, Wright KD, Lee K. Gray-Zone strategy against North Korea. Webpage media. foreign Policystrategy against North Korea, 2019. Available: https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/05/14/the-united-states-needs-agray-zone-strategy-against-north-korea-missile-test-nuclear/

- 8.Wright ND. Getting Messages Through: The Cognition of Influence with North Korea and East Asia, Report for the DoD Joint Staff/J39 Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Branch. Intelligent Biology: London (United Kingdom), 2018. https://nsiteam.com/social/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Cognition-of-Influence_Final-Report_IntelligentBiology.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ruckart PZ, Fay M. Analyzing acute-chemical-release data to describe chemicals that may be used as weapons of terrorism. J Environ Health 2006;69:9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackerman G, Tamsett J. Jihadist and weapons of mass destruction. New York (United States): CRC Press (Taylor and Francis Group), 2009: 489. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geraci MJ. Mustard gas: imminent danger or eminent threat? Ann Pharmacother 2008;42:237–46. 10.1345/aph.1K445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bourassa S. The use of a gas mask during medical treatment in chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear environment. Kingston, Ontario: Division of Continuing Studies, Department of Chemistry & Chemical Engineering. Department of National Defence. Government of Canada. Royal Military College Editor-Massey Library, 2009: 200 pages. https://elibrary.rmc.ca/uhtbin/cgisirsi.exe/?ps=9GLnAMP45s/MASSEY/X/2/1000 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourassa S. L'impact Du travail respiratoire et les échanges gazeux pour l'utilisateur Du masque gaz (the impact of the work of breathing and respiratory gas exchange in gas mask users. Québec, Québec (Canada: Faculté des études supérieures. Faculté de médecine. Université Lava, 2017: 134. https://corpus.ulaval.ca/jspui/handle/20.500.11794/27792 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulz-Kirchrath S. Compendium chemical warfare agents. Oberschefflenzer (Germany): OWR AG, 2006: 68. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulz-Kirchrath S. Compendium biological warfare agents. OWR AG: Oberschefflenzer (Germany), 2006: 68. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ciottone GR. Toxidrome recognition in Chemical-Weapons attacks. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1611–20. 10.1056/NEJMra1705224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons . Medical aspects of assistance and protection against chemical weapons. The Hague (Netherlands) https://www.opcw.org/resources/assistance-and-protection/medical-aspects-assistance-and-protection-against-chemical [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suchard JR. Chemical Weapons. In: Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, et al., eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies. 10e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education, 2015: 1687–8. [Google Scholar]

- 19. U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defense. In: Medical management of chemical casualties handbook. Chemical Casualty Care Division. Government of the United States of America: Aberdeen Proving Ground (Maryland, United States. 7th Edition, 2007: 370 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S Army Center for Health Promotion & Preventive Medicine . The medical NBC Battlebook. Maryland: Government of the United States of America, 2002: 310. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodurtha P, Wilson B, Dickson EG. Cce 204 Militarymilitary Chemistrychemistry. course notes. Kingston: Department of National Defence, Government of Canada, Royal Military College Editor-Massey Library, 2016: 400. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Headquarters Departmentdepartment of the Army, the Navy, the Airair Forceforce and Commandant Marinemarine Corpscorps . Army field manual FM 8-285, navy medical P-5041, air force manual 44-149, marine force manual 11-11. treatment of chemical agent casualties and conventional military chemical injuries. Washington, DC (United States): Government of the United States of America, 1995: 138 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Army MC, Navy AF, Multiservice T. Techniques and Procedure for Nuclear, Biological and Chemical Defense Operations. Reference numbers (FM 3-11 (FM 3-100); MCWP 3-37.1; NWP 3-11; AFTTP (I) 3-2.42. Washington, DC: Government of the United States of America, 2003: 220 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 24.U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases . Medical management of biological casualties. Fort Detrick, Frederick, Maryland (United States): Government of the United States of America, 1998: 122 pages. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kortepeter M, Christopher GW. USAMRIID’s medical management of biological casualties handbook. Washington, DC (United States). Fort Detrick (United States): Government of the United States of America, 2001: 134. [Google Scholar]

- 26.North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) . Medical management of CBRN casualties. AMEDP-7.1. North Atlantic Treaty organization allied medical publication. NATO standardization office (NSO) © NATO/OTAN: Brussels (Belgium), 2018. Available: https://www.coemed.org/files/stanags/03_AMEDP/AMedP-7.1_EDA_V1_E_2461.pdf [Accessed 29 Jun 2022].

- 27.Barbee G, DeFoe D, Gonzalez C. Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) Injury – Part I: Initial Response to CBRN Agents (CPG ID: 69). In: Joint trauma system, clinical practice guidelines. Washington, DC (United States): Department of defense. Department of defense trauma registry. Government of the United States of America, 2018: 22. https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Chemical_Biological,_Radiological_Nuclear_Injury_Part1_Initial_Response_01_May_2018_ID69.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barbee G, DeFoe D, Gonzalez C. Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) Injury – Response Part 2: Medical Management of Chemical Agent Exposure (CPG ID:69). In: Joint trauma system, clinical practice guidelines. Department of defense. Department of defense trauma registry. Washington, DC (United States): Government of the United States of America, 2019: 36. https://jts.amedd.army.mil/assets/docs/cpgs/Chemical_Biological,_Radiological_Nuclear_Injury_Response_Part_2_Medical_Management_23_Jan_2019_ID69.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians & Prehospital Trauma Life Support Committee . Mass casualties and terrorism. Mosby/JEMS: Maryland Heights, Missouri (United States), 2007: 517–77. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Canadian Standards Association . Protection of first responders from chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) events. CAN/CGSB/CSA-Z1610-11. Government of Canada: Ottawa, Ontario (Canada), 2016: 148 pages. ISBN: 978-1-55491-613-9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Public Health England . Chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear incidents: clinical management and health protection. Report No. 2018080. London (United Kingdom): The Goverment of the United Kingdom, 2018: 148. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/712888/Chemical_biological_radiological_and_nuclear_incidents_clinical_management_and_health_protection.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bennett RL. Chemical or biological terrorist attacks: an analysis of the preparedness of hospitals for managing victims affected by chemical or biological weapons of mass destruction. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2006;3:67–75. 10.3390/ijerph2006030008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berkenstadt H, Ziv A, Barsuk D, et al. The use of advanced simulation in the training of anesthesiologists to treat chemical warfare casualties. Anesth Analg 2003;96:1739–42. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000057027.52664.0B [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kyle RR, Via DK, Lowy RJ, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to teach responses to weapons of mass destruction and terrorism using combined simulation modalities. J Clin Anesth 2004;16:152–8. 10.1016/j.jclinane.2003.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prockop LD. Weapons of mass destruction: overview of the CBRNEs (chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, and explosives). J Neurol Sci 2006;249:50–4. 10.1016/j.jns.2006.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandström BE, Eriksson H, Norlander L, et al. Training of public health personnel in handling CBRN emergencies: a table-top exercise card concept. Environ Int 2014;72:164–9. 10.1016/j.envint.2014.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Treat KN, Williams JM, Furbee PM, et al. Hospital preparedness for weapons of mass destruction incidents: an initial assessment. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:562–5. 10.1067/mem.2001.118009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Awad N, Cocchio C. Assessment of Hospital Pharmacy Preparedness for Mass Casualty Events P&T 2015;40:264–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization . Interim guidance document – initial clinical management of patients exposed to chemical weapons. Geneva (Switzerland), 2014: 34. https://www.who.int/environmental_health_emergencies/deliberate_events/interim_guidance_en.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons International Cooperation . Practical guide for medical management of chemical warfare casualties. The Hague (Netherlands: Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons International Cooperation and Assistance Division Assistance and Protection Branch, 2019: 164. https://www.opcw.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019/05/Full%20version%202019_Medical%20Guide_WEB.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wedmore IS, Talbo TS, Cuenca PJ. Intubating laryngeal mask airway versus laryngoscopy and endotracheal intubation in the nuclear, biological, and chemical environment. Mil Med 2003;168:876–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaufman BJ. Hazardous Materials Incident Response. In: Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Lewin NA, et al., eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, 10e. McGraw-Hill Education: New York (United States), 2015: 1670–7. ISBN: 978-0-07-180184-3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zilker T. Medical management of incidents with chemical warfare agents. Toxicology 2005;214:221–31. 10.1016/j.tox.2005.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arora R, Chawla R, Marwah R, et al. Medical radiation countermeasures for nuclear and radiological emergencies: current status and future perspectives. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2010;2:202–12. 10.4103/0975-7406.68502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anderson PD. Emergency management of chemical weapons injuries. J Pharm Pract 2012;25:61–8. 10.1177/0897190011420677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Totenhofer RI, Kierce M. It's a disaster: emergency departments' preparation for a chemical incident or disaster. Accid Emerg Nurs 1999;7:141–7. 10.1016/s0965-2302(99)80073-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kenar L, Karayilanoglu T. Prehospital management and medical intervention after a chemical attack. Emerg Med J 2004;21:84–8. 10.1136/emj.2003.005488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramesh AC, Kumar S, Triage KSJ. Triage, monitoring, and treatment of mass casualty events involving chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear agents. J Pharm Bioallied Sci 2010;2:239. 10.4103/0975-7406.68506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bourassa S, Paquette-Raynard E, Noebert D, et al. Gaps in prehospital care for patients exposed to a chemical attack – a systematic review. Prehosp Disaster Med 2022;37:230–9. 10.1017/S1049023X22000401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nozaki H, Hori S, Shinozawa Y, et al. Secondary exposure of medical staff to sarin vapor in the emergency room. Intensive Care Med 1995;21:1032–5. 10.1007/BF01700667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Okumura T, Takasu N, Ishimatsu S, et al. Report on 640 victims of the Tokyo subway sarin attack. Ann Emerg Med 1996;28:129–35. 10.1016/s0196-0644(96)70052-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosman Y, Eisenkraft A, Milk N, et al. Lessons learned from the Syrian sarin attack: evaluation of a clinical syndrome through social media. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:644–9. 10.7326/M13-2799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yanagisawa N, Morita H, Nakajima T. Sarin experiences in Japan: acute toxicity and long-term effects. J Neurol Sci 2006;249:76–85. 10.1016/j.jns.2006.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hick JL, Hanfling D, Burstein JL, et al. Protective equipment for health care facility decontamination personnel. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2003;42:370–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Houston M, Hendrickson RG. Decontamination. Crit Care Clin 2005;21:653–72. 10.1016/j.ccc.2005.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bodurtha P, Dickson E. Decontamination science and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) selection for Chemical-Biological-Radiological-Nuclear (CBRN) events. CRTI Project CSSP-2013-TI-1036. Department of National Defence. Government of Canada: Ottawa (Ontario, Canada), 2013. https://cradpdf.drdc-rddc.gc.ca/PDFS/unc263/p805114_A1b.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 57.Khemani RG, Smith L, Lopez-Fernandez YM, et al. Paediatric acute respiratory distress syndrome incidence and epidemiology (PARDIE): an international, observational study. Lancet Respir Med 2019;7:115–28. 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30344-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Santschi M, Jouvet P, Leclerc F, et al. Acute lung injury in children: therapeutic practice and feasibility of international clinical trials. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2010;11:681–9. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3181d904c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Atti S, Erickson T. The continuing threat of chemical weapons: a need for toxicological preparedness. Clinical Toxicology. Conference NACCT Taylor & Francis LTD 2017;55:158–759. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Amend N, Niessen KV, Seeger T, et al. Diagnostics and treatment of nerve agent poisoning-current status and future developments. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2020;1479:1–20. 10.1111/nyas.14336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fong IW, Alibek K. Bioterrorism and Infectious Agents – A New Dilemma for the 21st Century, Emerging Infectious Diseases of the 21st Century. United States: Springer, 2005: 273. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaillard Y, Regenstreif P, Fanton L. Modern toxic antipersonnel projectiles. Am J Forensic Med Pathol 2014;35:258–64. 10.1097/PAF.0b013e318288abe8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Office of the Director of National Intelligence . Chemical Warfare. Webpage. The National Counterproliferation Center. Government of the United States of America. Available: https://www.dni.gov/index.php/ncpc-features/1552 [Accessed 24 Aug 2022].

- 64.United Nations . Government, ‘Islamic State’ Known to Have Used Gas in Syria, Organisation for Prohibition of Chemical Weapons Head Tells Security Council. November 7, 2017. Webpage Media. Meetings Coverage Security Council. Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. 8090th Meeting (PM). SC130/60. Available: https://press.un.org/en/2017/sc13060.doc.htm#:~:text=The%20Islamic%20State%20of%20Iraq,OPCW)%E2%80%91United%20Nations%20Joint%20Investigative [Accessed 24 Aug 2022].

- 65.Lombardo C. More than 300 chemical attacks Launched during Syrian civil war, study says. NPr news: September 17, 2019. Webpage media. Available: https://www.npr.org/2019/02/17/695545252/more-than-300-chemical-attacks-launched-during-syrian-civilwar-study-says [Accessed 24 Aug 2022].

- 66.BBC News . Amesbury poisoning: Experts confirm substance was Novichok. September 4, 2018. Webpage Media. Available: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-45411557 [Accessed 24 Aug 2022].

- 67.Dearden L. Salisbury novichok attack: Timeline of movements by Russian ‘spies’ accused of attack. Police appealing for information on suspects and their movements over two days in the UK. Independent: September 21, 2021. Webpage Media.. Available: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/crime/salisbury-timeline-novichok-attack-suspects-b1923902.html [Accessed 24 Aug 2022].

- 68.Strack C. The Evolution of the Islamic State’s Chemical Weapons Efforts. Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. CTCSentinel 2017;10:19–23 https://ctc.usma.edu/the-evolution-of-the-islamic-states-chemical-weapons-efforts/ [Google Scholar]

- 69.Center for Control Diseases and Prevention . Facts Aboutabout Tabuntabun. Webpage. Emergency Preparedness and Response. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Government of the United States of America. Page last reviewed, 2018. Available: https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/tabun/basics/facts.asp

- 70.Center for Control Diseases and Prevention . Facts Aboutabout VX. Webpage. Emergency Preparedness and Response. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Government of the United States of America. Page last reviewed, 2018. Available: https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/vx/basics/facts.asp [Accessed 24 Aug 2022].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.