Abstract

Objectives

In late 2014, an HIV outbreak occurred in rural Cambodia among villagers who received medical injections from unlicensed medical providers, justifying the need to assess medical injection practices among those who are at risk of acquiring and/or transmitting HIV. This study examined medical injection/infusion behaviours among people living with HIV (PLWH) and those who were HIV negative in Cambodia. These behaviours should be properly assessed, especially among PLWH, as their prevalence might influence a future risk of other outbreaks.

Design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted in order to examine injection behaviours and estimate injection prevalence and rates by HIV status. Unsafe injections/infusions were those received from village providers who do not work at a health centre or hospital, or traditional providers at the participant’s (self-injection included) or provider’s home. Logistic regression was performed to examine the relationship between unsafe injection/infusion and HIV, adjusting for sex, age, education, occupation, residence location and other risk factors.

Setting

The survey was conducted in 10 HIV testing and treatment hospitals/clinics across selected provinces in Cambodia, from February to March 2017.

Participants

A total number of 500 volunteers participated in the survey, 250 PLWH and 250 HIV-negative individuals.

Outcome measures

Measures of injection prevalence and other risk behaviours were based on self-reports.

Results

Both groups of participants reported similar past year’s injection/infusion use, 47% (n=66) among PLWH and 54% (n=110) HIV-negative participants (p=0.24). However, 15% (n=11) of PLWH reported having received unsafe last injection compared with only 7% (n=11) of HIV-negative participants. In logistic regression, this association remained numerically positive, but was not statistically significant (adjusted OR 1.84 (95% CI: 0.71 to 4.80)).

Conclusions

The inclination for medical injections and infusions (unsafe at times) among PLWH and the general population in Cambodia was common and could possibly represent yet another opportunity for parenteral transmission outbreak.

Keywords: Epidemiology, HIV & AIDS, PUBLIC HEALTH

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

By accounting for the types of facilities at which injections and infusions were carried out, as we have done in our study, we were able to ascertain that the outcome of the study (the extent to which these injections/infusions could be interpreted as safe or unsafe) was measured reasonably accurately.

One of the biggest issues in any cross-sectional studies is reverse causation; however, this was highly unlikely in our study.

Medical injection and infusion practices were assessed through self-reports, which could lead to bias.

In order to have a complete understanding of the injection and infusion practices, the prescription tendencies of care providers should have also been assessed, but our work was only able to assess these practices among people living with HIV and those who were HIV negative across the 10 selected study sites.

Introduction

The WHO considered over or unnecessary use of injections as unsafe injection practices, alongside the use of unsafe methods for injection, such as reusing syringes and needles.1 2 In some parts of the world, particularly in low/middle-income countries (LMICs), this common medical procedure is being performed daily using unsafe (yet avoidable) injection practices which put both people living with HIV (PLWH) and communities at risk of blood-borne pathogen transmission.1–5 In late 2014, a rural community in Cambodia had a large outbreak of HIV when an unlicensed medical practitioner infected 242 villagers aged between 2 and 89 years through his use of contaminated injection equipment.6 7 In early 2018, another two HIV outbreaks linked with unsafe injection practices occurred in India and Pakistan.3 In Iran, the behavioural survey among people who inject drugs demonstrated a positive correlation between risky and unsafe injection use and the prevalence of HIV.8 These incidents and reports demonstrated the ongoing risk of outbreaks related to unsafe medical injection practices in many parts of the world. Additionally, a review article on injection practices worldwide published in 2000 reckoned that many injections are unsafe and unnecessary and that the region with the highest unsafe practice (reuse of injection materials) was indeed in Southeast Asia.9

In Cambodia, private healthcare providers are commonly sought for care. Although many of them are public healthcare workers who practise privately during off-working hours, there are also providers, mainly in rural areas, who are unlicensed private practitioners from whom the community seeks medical care including (but not limited to) injections and infusions. This is not uncommon in some parts of LMICs in which a person without proper training or education in administering certain medical procedures provides medical injections.4

The last Cambodia Demographic and Health Survey (Cambodia DHS 2014) assessed injection practices as part of their behavioural survey among the general population. According to their report, the prevalence of medical injection (having had any medical injections from health worker in the past 12 months) among the Cambodian population aged 15–49 years was approximately 35% (or 37% and 27% among women and men, respectively).10 Previous studies on injection use and safety practices (including the DHS) in Cambodia usually focused on the general population.11 Moreover, although according to the 2019 review on injection practices using the DHS data from 40 countries reported reduced numbers of unsafe injections in 81% of the countries, the data used were from 2011 to 2015,12 and no other assessment had been reported since then. Until the present work, these behavioural risk factors have not been studied among PLWH, despite the fact that the risk of getting or transmitting blood-borne pathogens among this population is heavily shaped by these behaviours. We hypothesised that PLWH might be seeking or receiving more medical injections (likely unnecessary and unsafe) than the general population for several reasons. First, being in regular care gives PLWH more opportunities to get diagnosed with various medical conditions and receive treatments. Second, PLWH often suffer from significantly more comorbidities, such as age-related non-communicable diseases and mental or neurological disorders, than the general population.13 14 For these reasons, PLWH might be in greater need of medical treatments, such as injections, than the general population.

Ever since the 2014 HIV outbreak in Roka village, there have been no other studies assessing injection behaviours among PLWH elsewhere; and the Cambodia DHS reported only medical injections given by healthcare workers. Without assessment of injection and infusion practices in people who are at risk of transmitting and acquiring HIV, it is challenging for public health professionals to advise or prepare public health measures which are both appropriate and efficient to address unsafe injection practices. Our study aims to primarily characterise injection practices among PLWH and those who were HIV negative and determine whether the first group were more likely to seek unsafe or unnecessary medical injections.

Although when considering unsafe medical injections, people usually refer to used syringes and needles, we considered (in this paper) injections provided by unlicensed (medical) practitioners unsafe as well. Understanding these injection-seeking behaviours among this population is helpful for planning necessary public health measures as well as improving access to formal healthcare facilities.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted a cross-sectional study among PLWH (n=250) who came to receive their HIV treatment care and those who came to have HIV testing and had a negative result (n=250) at 10 selected HIV clinics in five provinces and the capital city (Phnom Penh) of Cambodia, from early February to the end of March 2017. The sample size of 250 per group was calculated to provide 90% power to test the hypothesis using a two-sample comparison of proportions where the first proportion was set at 20% of injection use (HIV-negative participants) and the second proportion was set at 35% (HIV-positive participants). In Cambodia, HIV voluntary testing sites and HIV/AIDS treatment and care clinics (called opportunistic infections/antiretroviral therapy (OIs/ART) sites) are under the supervision of the National Centre for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology and STD (NCHADS); there are around 52 of them across Cambodia at the time of the study.

A two-stage sampling approach was employed for participant selection. We selected 10 sites and out of the 52 sites with joint testing/OI/ART services (meaning those with both testing and OI/ART services) using probability-proportional-to-size method. Then, from each of these 10 sites, we consecutively sampled 25 PLWH who came for their regular clinic visit or pharmacy refill. In a similar manner, HIV-negative individuals who came to each selected site for HIV testing who got a negative result were approached for recruitment (25 per site).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Both PLWH and HIV-negative participants were eligible if they were at least 18 years old and were willing and able to provide written informed consent to take part in the study on the data collection day. Excluded were individuals who were not willing or able to complete the questionnaire, had undetermined test result or presented any other condition that, in the opinion of the research or local healthcare staff, would preclude informed consent.

Medical history and behavioural assessment

HIV-specific factors (eg, HIV status, date of HIV test, WHO disease stage, etc) were obtained from linkage with the NCHADS database. Behavioural data were collected using a Computer-Assisted Person Interview technique, administered via tablet and questions were guided by the literature. Participants were asked to report on sociodemographic factors, such as date of birth, sex, education, marital status, occupation, general location of residence (village, community, district and province) and a wide range of behavioural factors including history of illicit injection drug use, alcohol and tobacco use and informal medical injection/infusion use (frequency and type of provider).

Definition and classification

The outcome of interest, unsafe medical injection (binary outcome), was defined as having received the last injection or infusion (within the past year) from village providers who do not work at a health centre or hospital, from traditional providers, or by self-injection (other than diabetic medication) either at their own home or at the provider’s home. In Cambodia and especially in rural areas, these health workers might also provide some basic medical services (including injections and infusions) at their patient’s home or in private hospitals/clinics. Therefore, regardless of where the PLWH received the injections, as long as they were provided by the providers who worked at a hospital or health centre, we considered these injections safe. Both intravenous and intramuscular injections were included in the questionnaire and reporting.

The prevalence of medical injections included those who reported at least one injection or infusion (over the past year), but excluded vaccinations, non-medical injections and rare medical injections such as transfusion.

The HIV status was not assessed by the study team, those with known HIV-positive or HIV-negative results were informed of the present study and referred by their care providers to the study team for further information on the study and consent process. We had no access to their HIV test or result.

Other risk behavioural assessments (alcohol and tobacco use, informal medical injection/infusion use, etc) were based on participants’ self-report.

Statistical analysis

We computed percentages and means of the key characteristics by HIV status. We calculated the prevalence of having had at least one medical injection from health workers and from all provider types over the past year among the participants (by their HIV status). Χ2 and Fisher’s exact tests were performed for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Next, the average number of past year’s medical injections from each type of providers by HIV status was also computed and we reported the p value derived from Poisson regression. Finally, to examine the relationship between unsafe medical injection practices and HIV status, we performed logistic regression, adjusting for sex, age, education, occupation, residence location, injection preference and other risk factors. Confounding variables were based on prior knowledge and literature review on similar work previously conducted.12 15 16 All analyses were done in STATA V.14.

Patient and public involvement

The PLWH, caregivers and those who sought HIV testing but were negative participated in the data collection of the study. Preliminary results of the study had been presented at the University of Health Sciences at the 2018 Scientific Days among invited caregivers, students and other invited guests and researchers.

Results

We presented key characteristics by HIV status in table 1. The sociodemographic factors are vastly different between the two groups in terms of age, marital status, educational background and occupation. PLWH appeared to be much older—mean age was 43 years (SD 9), of a lower educational background and married, while the majority of HIV-negative participants were younger—mean age was 31 years (SD 11), more educated and single. However, both groups were comparable in terms of their sex, income and residence location distribution. Female participants accounted for about 66% (n=164) of PLWH and 71% (n=177) of those uninfected. The majority of participants from both groups were from the provinces, 91% (n=227) among PLWH and 93% (n=231) among the uninfected.

Table 1.

Key characteristics of study participants by HIV status, Informal Medical Injection Study (n=500), Cambodia, 2017

| Sociodemographics | HIV+ (n=250) | HIV− (n=250) | P value | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 164 | 65.6 | 177 | 70.8 | 0.21 |

| Male | 86 | 34.4 | 73 | 29.2 | |

| Age* (mean, SD) | (43.1, 9.0) | (30.6, 10.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 15 | 6.0 | 87 | 34.8 | <0.001 |

| Married | 140 | 56.0 | 141 | 56.4 | |

| Divorced | 41 | 16.4 | 15 | 6.0 | |

| Widowed | 54 | 21.6 | 7 | 2.8 | |

| Education | |||||

| Secondary or higher | 104 | 41.6 | 163 | 65.2 | <0.001 |

| Primary or less | 146 | 58.4 | 87 | 34.8 | |

| Occupation* | |||||

| Unemployed | 81 | 32.7 | 126 | 50.8 | <0.001 |

| Self-employed/farmers | 95 | 38.3 | 70 | 28.2 | |

| Employed | 72 | 29.0 | 52 | 21.0 | |

| Household annual income*† (US$) | |||||

| >3000 | 40 | 22.9 | 44 | 22.8 | 0.48 |

| 1800–3000 | 45 | 25.7 | 42 | 21.8 | |

| 1001–1800 | 39 | 22.3 | 56 | 29.0 | |

| ≤1000 | 51 | 29.1 | 51 | 26.4 | |

| Current address* | |||||

| Province | 227 | 90.8 | 231 | 92.8 | 0.42 |

| Phnom Penh (capital city) | 23 | 9.2 | 18 | 7.2 | |

| Other behavioural risk factors‡ | |||||

| Smoke monthly or more often | 30 | 12.0 | 13 | 5.2 | <0.01 |

| Feeling drunk at least once a month | 45 | 18.0 | 63 | 25.2 | 0.05 |

| Contact with syringe and needle at workplace | 8 | 3.2 | 36 | 15.5 | <0.01 |

| Had at least one hospitalisation | 42 | 23.5 | 87 | 49.2 | <0.001 |

*Missing (HIV+ and HIV−, respectively): age (n=5, n=5); occupation (n=2, n=2); current address (n=0, n=1).

†The categories for household income used quartiles to assure sufficient numbers in each category.

‡Self-report over the past year.

Injection/infusion use

Injection and infusion practices are described in table 2. We found that the average annual number of injection/infusion from health workers was about three and four injections per person among PLWH and those who were HIV negative, respectively (p<0.001). The prevalence of any medical injection/infusion provided by health workers over the past year was higher among HIV-uninfected participants, 72% (n=153) compared with 40% (n=61) among those who were HIV positive (p<0.001). However, the prevalence of past year’s injection/infusion from all providers between the two groups was comparable, 47% (n=66) among PLWH and 54% (n=110) among those uninfected (p=0.24).

Table 2.

Injection and infusion-seeking behaviours of study participants by HIV status, Informal Medical Injection Study (n=500), Cambodia, 2017

| Injection and infusion practices | HIV+ (n=250) | HIV− (n=250) | P value | ||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Injection and infusion received | |||||

| Last injection/infusion within past year | |||||

| Given by relative/acquainted provider | 51 | 23 | 50 | 22.8 | 0.97 |

| Recommended by provider | 54 | 85.7 | 131 | 90.3 | 0.33 |

| Given at public hospital | 35 | 44.9 | 97 | 54.5 | 0.16 |

| Given at private hospital/clinic | 29 | 53.7 | 58 | 46 | 0.35 |

| Given at their own home | 16 | 31.4 | 24 | 21.2 | 0.16 |

| Number of injections/infusions within past year | |||||

| More than a year ago | 107 | 67.7 | 144 | 66.4 | 0.78 |

| From health workers (mean, SD) | (3.2, 7.5) | (4.3, 7.1) | <0.001 | ||

| From all providers (mean, SD) | (3.5, 7.1) | (4.4, 7.8) | <0.001 | ||

| At least one—health worker | 61 | 40.4 | 153 | 72.5 | <0.001 |

| At least one—all providers | 66 | 47.5 | 110 | 53.9 | 0.24 |

| Prefer injection to other treatments | 124 | 49.6 | 145 | 58 | 0.06 |

| Injection and infusion safety | |||||

| Last injection within past year | |||||

| Unsafe† last injection | 11 | 15.5 | 11 | 7.3 | 0.06 |

| Provider did not use new, unopened syringe/needle | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3.8 | 0.19 |

| Last injection within past year | |||||

| Unsafe† last infusion | 10 | 13.5 | 13 | 10.5 | 0.52 |

| Provider did not use new, unopened syringe/needle | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2.5 | 0.55 |

*The questions on this preference pertain to several tracer conditions (in which case medical injections are clearly unnecessary).

†Administered at participant’s or provider’s home by village providers who do not work at health centre or hospital, traditional providers or self-injection.

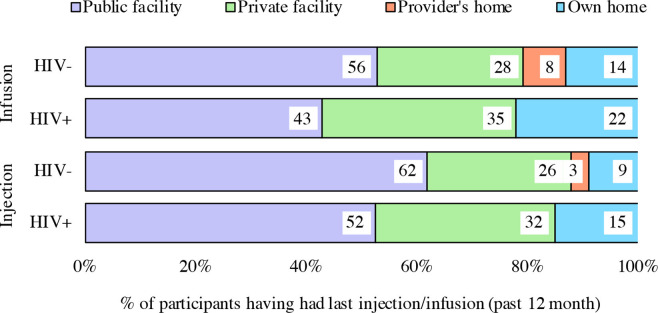

When asked about the last injection/infusion they received within the past year, PLWH were more likely to report having received their last one(s) at a private hospital/clinic, 54% (n=29), or at their own home, 31% (n=16), compared with a 46% (n=58) and 21% (n=24), respectively, reported by their HIV-negative counterparts. HIV-negative participants were more likely to have received their last injection/infusion at a public hospital, 54% (n=97), as opposed to 45% (n=35) of PLWH (p=0.16). Figure 1 broke down last injection and infusion by facility types in more details.

Figure 1.

Injection and infusion use among study participants by types of facility. Source: data from the 2017 Medical Injection Study (N=500), Cambodia.

Regardless of HIV status, public and private sectors accounted for the majority of medical injection and infusion received. Although none of our PLWH reported having received their last injection or infusion at a traditional healer’s home, about one-fourth of them reported having received their last injection (15% (n=9)) and infusion (22% (n=14)) at their own home.

A large number of participants from both groups, 50% (n=124) of PLWH and 58% (n=145) of those uninfected, reported that they preferred injection/infusion to other forms of treatment when sick (p=0.06). Moreover, more than 60% of participants from both groups indicated that they had actually received more injections the past year than previous year. Similarly, over 80% of both PLWH and HIV-negative participants reported that their last injection was in fact recommended by their care provider.

Injection/infusion safety practices

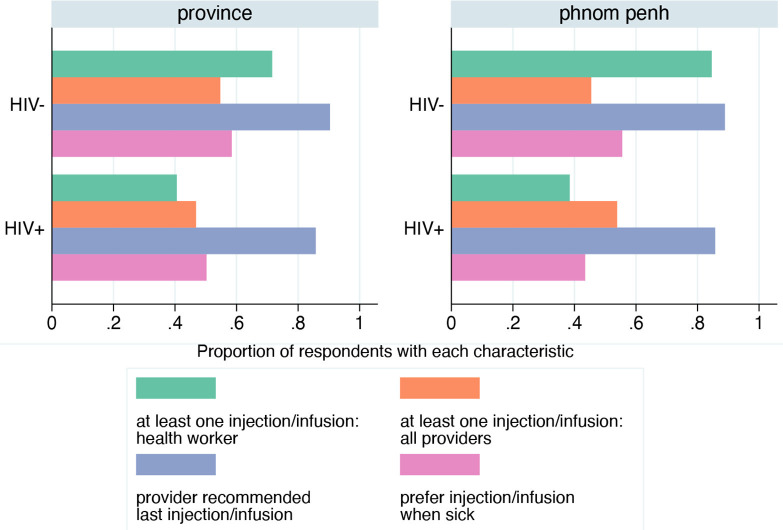

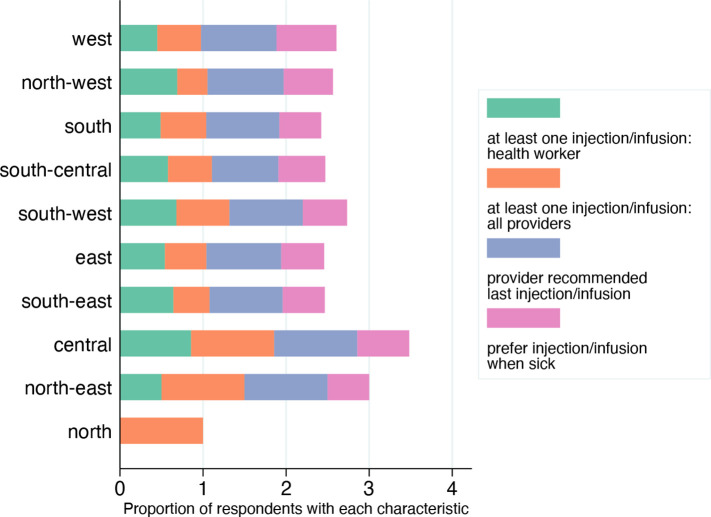

About 4% (n=6) of HIV-negative participants reported that the provider for their last injection did not use a new, unopened package of syringe and needles while none of PLWH reported this practice (p=0.06). Although the average annual injection/infusion rates from all provider types (including health workers) were slightly lower among PLWH (three injections per person) compared with those who were HIV negative (four injections per person) (p<0.001), we observed a slightly larger proportion of PLWH reported an unsafe last injection within the past year, 15% (n=11) vs 7% (n=11) reported by those who were HIV negative (p=0.06). Likewise, 13% (n=10) of PLWH reported an unsafe last infusion within the past year, compared with 10% (n=13) of HIV-uninfected participants (p=0.52). Regardless of whether they live in the provinces or the capital city ‘Phnom Penh’ (figure 2), the majority of participants from both groups reported their provider recommended their last injection/infusion and more HIV-negative participants than PLWH received their last injection/infusion from health workers. In figure 3, overall, we saw similar patterns across the country, except provinces in the central and north-eastern parts of Cambodia where injection/infusion use appeared the highest.

Figure 2.

Injection and infusion use among study participants by residence location—Phnom Penh versus provinces. Source: data from the 2017 Medical Injection Study (N=500), Cambodia.

Figure 3.

Injection and infusion use among study participants by geographical distribution. West: Pursat; North-west: Siem Reap, Battambang, Odor Meanchey, Banteay Meanchey; South: Takeo, Kampot, Prey Veng; South-central: Phnom Penh, Kampong Speu; South-west: Sihanoukville, Koh Kong; East: Kratie, Mondulkiri; South-east: Tbong Khmum, Svay Rieng, Kampong Cham, Kandal; Central: Kampong Thom, Kampong Chhnang; North-east: Steung Treng; North: Preah Vihear.

Association between unsafe medical injection/infusion and HIV

Table 3 presents the crude OR (cOR), adjusted OR (aOR) and the 95% CIs of the relationship between unsafe last medical injection and HIV status. Before adjustment, only sex, occupation and presence of two or more risk behaviours were associated with having had unsafe last injection or infusion (table 3). The association between unsafe medical injection/infusion and HIV status was numerically positive but was not statistically significant (cOR=1.45 (95% CI: 0.70 to 3.00)). After adjusting for other covariates, the aOR was 1.84 (95% CI: 0.71 to 4.80), remaining statistically non-significant.

Table 3.

Association between getting unsafe medical injection and HIV status, Informal Medical Injection Study (n=500), Cambodia, 2017

| Outcome: unsafe injection/infusion | Crude OR | 95% CI | Adjusted OR* | 95% CI |

| HIV+ (ref. HIV−) | 1.45 | 0.70 to 3.00 | 1.84 | 0.71 to 4.80 |

| Male (ref. female) | 2.17 | 1.03 to 4.57 | 2.37 | 1.00 to 5.62 |

| Age | 1 | 0.97 to 1.03 | 0.98 | 0.94 to 1.02 |

| Education (ref. secondary or higher) | ||||

| Primary or less | 0.7 | 0.33 to 1.46 | 0.96 | 0.41 to 2.23 |

| Occupation (ref. unemployed) | ||||

| Farmers and self-employed | 0.91 | 0.41 to 2.01 | 0.83 | 0.36 to 1.91 |

| Employed | 0.48 | 0.17 to 1.36 | 0.59 | 0.20 to 1.72 |

| Current address in Phnom Penh | 1.18 | 0.33 to 4.23 | 1.02 | 0.27 to 3.88 |

| (ref. in provinces) | ||||

| Prefer injection or infusion when sick | 0.59 | 0.29 to 1.21 | 0.66 | 0.32 to 1.40 |

| (ref. no preference) | ||||

| Had at least two risk behaviours† | 0.67 | 0.19 to 2.33 | 0.47 | 0.13 to 1.75 |

Unsafe injection/infusion: last injection/infusion within the past year administered at participant’s or provider’s home by village providers who do not work at health centre or hospital, traditional providers or self-injection.

*Adjusted for gender, age, education, occupation, residence location, injection or infusion preference, and presence of two or more risk behaviours.

†Combination of risk behaviours include: one or more hospitalisation, contact with syringe and needle, smoking monthly or more often and feeling drunk monthly or more often in the past year.

Discussion

In our study, we found a high prevalence of medical injections (having had any medical injections in the past year from health workers) among the study participants in general (almost 60%), but PLWH were more likely to have had unsafe last injection or infusion (having received their last injection from informal providers), compared with those who were HIV negative. Regardless of the reasons for medical injections (with few exceptions), this practice is very common and should be addressed, whether it is the PLWH’s false beliefs that injectable drugs work better than oral ones for certain medical conditions or the tendency to overprescribe these injectables.

According to the 2014 Cambodia DHS, there were great variations of injection prevalence (administered by health workers) ranging from 12% to 45%, and the average annual number of injections is one to two per person.10 We found a much higher prevalence among our study sample; our results were more in line with an article published in 2004 by Vong et al that also looked at medical injections in Cambodia and found 40% of medical injection prevalence and average number of injection (over the past 6 months) of 5.9 per person.11 This is, in fact, consistent with findings from a review paper published in 2016 which found that the 12-month medical injection prevalence ranged from 30% to 68% across studies conducted in South Asia.17 It should be noted that both the 2004 study and the 2014 DHS examined the injection practices among the general population outside of HIV setting (treatment or testing), and that it was unclear in the Cambodia DHS if infusions were also counted for their injection reporting. Our study grouped infusions with injections when reporting prevalence, similar to the 2004 study (Vong et al), but our study reported the injection behaviours over the past year instead of over 6 months like Vong et al did. Several other factors such as limited education, tendency of prescribers to recommend and participant’s personal preference of injection and the study population could be responsible for higher rates being reported in our study compared with others. However, these seemed consistent with a recently published paper which found high hepatitis C prevalence among Cambodian population that is likely due to medical injections.16 High prevalence of medical injection (ranging from 30% to 68%) had also been reported across studies conducted in South Asia.17 Results from a Kenyan survey published in 2016 suggested a positive association between HIV and those who reported having received injection in the last 12 months,18 although it should be noted that the Kenyan study only reported injections from care providers and not traditional healers or other types of providers.

The older mean age of our PLWH might also explain the high prevalence of medical injections among them. Because PLWH in the study were on average older, they could be sicker and, therefore, sought more medical procedures including injections. The age distribution of PLWH in Cambodia is actually weighed down by those who had been infected in the early 90s, and fewer people had become infected since 2000.19

The study should be interpreted with consideration to a number of limitations. Our assessment of the outcome was based on self-recall which could result in misclassification of the outcome measured. However, we have limited recalls to the past 12 months and reckon that to avoid capturing only certain fluctuations, a recall over 12 months appeared reasonable. Multiple studies used a 12-month time frame for estimating prevalence (although they mainly assessed drug use).20 21 As medical injections are generally also uncommon events, we, therefore, expected this misclassification, if any, to be minimal. By design, the outcome–exposure relationship in our study is obscure. However, our PLWH were mostly prevalent cases and older—92% of PLWH had been diagnosed more than 2 years prior (result not shown)—who were most likely got infected during the early 90s through unsafe sexual behaviours and not through unsafe injection practices. Consecutive sampling among PLWH and HIV-negative participants could also affect our internal validity; however, the process of scheduling the appointment at each selected facility for both groups is already in itself a random process. There were also patients who just dropped in. In other words, there is no reason to believe that participants might differ in terms of injection use between the time of our data collection and any other time. This does, however, limit our own study findings’ generalisability in a way that they might be applicable to only PLWH and HIV-negative population who come to receive care and seek HIV testing at the selected clinics and hospitals.

The strengths of our study included the fact that we accounted for not only both the provider of the last injection or infusion received within the past year, but also the facility at which these medical procedures were given. The combination of both provider and facility types should be able to capture better the safety aspect of medical injection/infusion. It should be noted that private facilities in Cambodia are generally considered ‘formal’ providers. Our work is one of the few studies which examined injection practices among PLWH over the past decade. Another study was conducted in 2016 (a year prior to when our study had started).16 Regardless, additional studies are necessary in order to confirm the findings from our work and understand the true underlying injection practices among PLWH.

Implications on policy and practices

Better access to medical care is a challenge particularly in rural parts of Cambodia. Our findings suggest the need to pull resources toward universal health coverage and educational programmes on safe medical injection practices. Resources are always limited in LMICs; therefore, support development partners play important roles in addressing these health needs. Besides these, other important educational programmes or activities directed at both PLWH and HIV-negative population are also deemed beneficial. Care providers could be important role models in enforcing correct practices of medical injection, particularly counsellors in the setting of HIV/AIDS care here could also play that role. Several HIV health facilities offered a digital platform of communication (Telegram group chat and Facebook Messenger chats are the most commonly used), on a voluntary basis, to PLWH and care providers to interact with one another on their HIV-related issues. These platforms could also be used as forums for communicating correct safe injection practices to them. Of course, these types of programmes would need further investigations in order to understand the population whom we could reach with these digital platforms. Regardless of HIV status, these educational programmes and activities should be widely inclusive because use of medical injection seemed to be very common among both PLWH and those who were HIV negative. Nevertheless, further investigations on the injection practices (among care provider) and the benefits of the aforementioned educational platforms would provide a more complete picture of the practices of medical injections in Cambodia and evidence as to whether they are beneficial or if additional programmes are to be put in place.

Conclusions

The majority of the Cambodian population, including those who are living with HIV, regard medical injections and infusions as a symbol for optimal medical care. Although on average, they might have received slightly fewer number of annual injections, PLWH were as likely to have received unsafe last injection/infusion within the past year as those who were HIV negative. This practice poses harms to themselves as well as their community and needs to be addressed among all stakeholders including providers who are able to prescribe medical injections including infusions. Our findings suggested the need to evaluate and reinforce safe injection practices among health workers for a complete assessment and understanding of medical injection education and practices in the health system.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @kennareyseang

Contributors: KS conducted literature search and data analysis, interpreted results, wrote the manuscript and created figures. KK and KV conducted literature search, designed the study, collected the data and guided data interpretation. DK conducted literature search and collected the data. VS and PG conceptualised the study, conducted literature search, interpreted results, guided data interpretation and accept full responsibility for the work and the conduct of the study. All authors provided critical feedback and shaped the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the UCLA Centre for AIDS Research/AIDS Institute (grant # 5P30 AI28697).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board (UCLA-IRB# 16-000876) and National Ethics Committee for Human Research (NECHR) of Cambodia (NECHR# 320). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Who guideline on the use of safety-engineered syringes for intramuscular, intradermal and subcutaneous injections in health care settings. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Injection safety: questions and answers. 2016. Available: https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/publications/is_questions-answers.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed July 2020].

- 3.Altaf A. Unsafe injection practices by medical practitioners in South Asia associated with hepatitis and HIV outbreaks. J Infect 2018;1:1–3. 10.29245/2689-9981/2018/2.1113 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta E, Bajpai M, Sharma P, et al. Unsafe injection practices: a potential weapon for the outbreak of blood borne viruses in the community. Ann Med Health Sci Res 2013;3:177–81. 10.4103/2141-9248.113657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . Make smart injection choices: national decision-making for safe and appropriate injections. 2017. Available: https://www.who.int/infection-prevention/tools/injections/IS_medical-treatement_leaflet.pdf?ua=1

- 6.Rouet F, Nouhin J, Zheng D-P, et al. Massive iatrogenic outbreak of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in rural Cambodia, 2014-2015. Clin Infect Dis 2018;66:1733–41. 10.1093/cid/cix1071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saphonn V, Fujita M, Samreth S, et al. Cluster of HIV infections associated with unsafe injection practices in a rural village in Cambodia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;75:e82–6. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esmaeili A, Shokoohi M, Danesh A, et al. Dual unsafe injection and sexual behaviors for HIV infection among people who inject drugs in Iran. AIDS Behav 2019;23:1594–603. 10.1007/s10461-018-2345-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutin YJF, Hauri AM, Armstrong GL. Use of injections in healthcare settings worldwide, 2000: literature review and regional estimates. BMJ 2003;327:1075. 10.1136/bmj.327.7423.1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of statistics; Directorate General for health; and ICF international. Cambodia demographic and health survey 2014. Phnom Penh, Cambodia, and Rockville, Maryland, USA: National Institute of Statistics; Directorate General for Health; and ICF International; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vong S, Perz JF, Sok S, et al. Rapid assessment of injection practices in Cambodia, 2002. BMC Public Health 2005;5:56. 10.1186/1471-2458-5-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayashi T, Hutin YJ-F, Bulterys M, et al. Injection practices in 2011-2015: a review using data from the demographic and health surveys (DHS). BMC Health Serv Res 2019;19:600. 10.1186/s12913-019-4366-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. amFAR. Hiv and comorbidities: the foundation for AIDS research (amFAR), 2020. Available: https://www.amfar.org/hiv-and-comorbidities/ [Accessed July 2020].

- 14.World Health Organization . Chronic comorbidities and coinfections in PLHIV. Available: https://www.who.int/hiv/topics/comorbidities/about/en/ [Accessed July 2020].

- 15.Janjua NZ, Akhtar S, Hutin YJF. Injection use in two districts of Pakistan: implications for disease prevention. Int J Qual Health Care 2005;17:401–8. 10.1093/intqhc/mzi048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pheng P, Meyer L, Ségéral O, et al. Hepatitis C seroprevalence among people living with HIV/AIDS and pregnant women in four provinces in Cambodia: an integrated bio-behavioral survey. BMC Infect Dis 2022;22:177. 10.1186/s12879-022-07163-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janjua NZ, Butt ZA, Mahmood B, et al. Towards safe injection practices for prevention of hepatitis C transmission in South Asia: challenges and progress. World J Gastroenterol 2016;22:5837–52. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i25.5837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimani D, Kamau R, Ssempijja V, et al. Medical injection use among adults and adolescents aged 15 to 64 years in Kenya: results from a national survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;66 Suppl 1:S57–65. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.. Ministry of Health/National center for HIV/AIDS, dermatology and STDs (MOH/NCHADS). annual report 2016 National Center for HIV/AIDS, Dermatology and STDs; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Degenhardt L, Peacock A, Colledge S, et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health 2017;5:e1192–207. 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30375-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) . Methodological guidelines to estimate the prevalence of problem drug use on the local level. Lisbon: EMCDDA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.