Abstract

Context

Researchers have identified sex differences in sport-related concussion incidence and recovery time; however, few have examined sex differences in specific recovery trajectories: time to symptom resolution, return to academics, and return to athletic activity across collegiate sports.

Objective

To examine sex differences in sport-related concussion recovery trajectories across a number of club and varsity sports with different levels of contact.

Design

Descriptive epidemiology study.

Setting

Collegiate varsity and club sports.

Patients or Other Participants

Sport-related concussions sustained by student-athletes (n = 1974; women = 38.8%) participating in Ivy League sports were monitored between 2013–2014 and 2018–2019.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Athletic trainers collected concussive injury and recovery characteristics as part of the Ivy League–Big Ten Epidemiology of Concussion Study's surveillance system. Time to symptom resolution, return to academics, and return to limited and full sport participation were collected. Survival analyses determined the time from injury to each recovery outcome for male and female athletes by sport. Peto tests were used to compare recovery outcomes between men's and women's sports and by sport.

Results

The median (interquartile range [IQR]) was 9 days (IQR = 4–18 days) for time to symptom resolution overall, 8 days (IQR = 3–15 days) for return to academics, 12 days (IQR = 8–23 days) for return to limited sport participation, and 16 days (IQR = 10–29 days) for return to full sport participation. We observed differences overall between sexes for median time to symptom resolution (men = 8 days [IQR = 4–17 days], women = 9 days [IQR = 5–20 days]; P = .03) and return to academics (men = 7 days [IQR = 3–14 days], women = 9 days [IQR = 4–17 days]; P < .001) but not for median time to return to athletics (limited sport participation: P = .12, full sport participation: P = .58). Within-sport comparisons showed that women's lacrosse athletes had longer symptom resolution (P = .03) and return to academics (P = .04) compared with men's lacrosse athletes, whereas men's volleyball athletes took longer to return to limited (P = .02) and full (P = .049) sport participation than women's volleyball athletes.

Conclusions

Recovery timelines between sexes were different. Athletes in women's sports experienced longer symptom durations and time to return to academics compared with men's sports, but athletes in men's and women's sports presented similar timelines for return to athletics.

Keywords: athletics, academics, return to learn, female athletes

Key Points

Athletes in women's collegiate sports exhibited a median of 1 day longer symptom duration and experienced a median of 2 days longer time to return to academics compared with male athletes.

Within-sport comparisons revealed sex differences for symptom resolution and return to academics in lacrosse and return to athletic activity in volleyball players.

Men's and women's collegiate sport athletes displayed similar times to return to limited and full sport participation after sport-related concussion.

Sport-related concussion (SRC) rates in collegiate sports have seemingly increased based on epidemiologic evidence,1,2 possibly because of greater awareness and recognition of SRC, as well as developments in guidelines or protocols for SRC management.3–5 Most research to date has addressed symptom recovery and timelines for return to play,6 which may be a product of SRC consensus statements focusing on the immediate removal from competition, SRC management strategies based on SRC symptoms, and effectiveness of gradual return-to-play protocols.3,5 The most recent consensus statement on concussion in sport4 discussed the importance of gradual return-to-school protocols. Importantly, however, few investigations have been designed to assess the nature and length of timelines for athletes returning to academics and sport activities across collegiate sports. Therefore, studies that include additional athlete and injury outcome characteristics (ie, sex, level of contact, time to return to academics, return to limited sport participation) across sports will be informative from a descriptive standpoint in documenting differences in SRC recovery and prognosis. Such descriptive findings may inform SRC management strategies, as clinicians can provide student-athletes with evidence-based anticipated clinical recovery outcomes that reflect outcomes displayed in similar sports and recognize when to make adaptations to their individualized concussion management plan if a student-athlete is not progressing through a clinical trajectory as expected.

The few researchers7,8 who assessed timelines for academic return after SRC mainly focused on return to learn in adolescent high school athletes. For example, in a recent study of youth athletes, DeMatteo et al7 found that approximately 64% reported problems in school and 74% received academic accommodations while recovering from an SRC. Among American youth football athletes, Chrisman et al8 noted that approximately 90% missed >1 week of school after SRC, returning on average 9 days postinjury. Although specifics of the academic return of collegiate athletes after an SRC are lacking, authors have reported that the median time to return to academics was 5 to 6 days9 and, on average, collegiate student-athletes missed 1 day of school after SRC.6,10 These studies were limited to small sample sizes in younger athletic populations, warranting a more robust examination in a larger sample of collegiate athletes. In addition, coupling return to athletics and academics with other aspects of clinical recovery (eg, symptom resolution) across sports with various risks and rates of SRC would provide useful data for clinicians during SRC management discussions with collegiate student-athletes.

Researchers10–12 have suggested that female athletes face an increased risk for SRC in sex-comparable sports, report a greater frequency and severity of SRC symptoms, and have protracted recovery patterns (ie, symptom resolution) compared with male athletes. Additional evidence10,11 has indicated sex differences in recovery timelines depending on the sport. For example, among female collegiate soccer and basketball athletes who sustained an SRC in practice and competition, respectively, Covassin et al11 demonstrated longer recovery times than in male athletes in similar activities. Although their study was limited to adolescent athletes, Desai et al13 observed that differences in time to clinical recovery on 5 markers of recovery between male and female athletes may have been due to modifiable risk factors, such as the timing of access to specialized care. In contrast, however, Putukian et al14 found no differences in time to symptom resolution or return to competition between male and female athletes in a sample restricted to 4 collegiate sports (ie, basketball, rugby, soccer, water polo). Similarly, Master et al15 identified no differences in return-to-play time between male and female collegiate athletes overall; yet when stratified by sport contact level, male athletes displayed longer recovery times than did female athletes in limited-contact sports, and female athletes took longer to recover than did male athletes in contact sports. These outcomes suggested mixed results for sex differences in SRC recovery and prognosis, although considerations of additional intermediate markers of clinical recovery (ie, return to academics, return to limited sport participation) were either few or also produced mixed results.9,14 Furthermore, many investigations of clinical recovery timelines post-SRC are underpowered to assess the effect of sex. Therefore, the purpose of our study was to assess whether clinical recovery trajectories, such as the times to symptom resolution, return to academics, and return to limited and full sport participation, differed in a large sample of male and female athletes across a number of collegiate club and varsity sports. We hypothesized that the time to each recovery outcome would not differ between male and female athletes.

METHODS

We reported clinical SRC outcome data from the Ivy League–Big Ten Epidemiology of Concussion Study, a large multisite collaboration across the Ivy League and Big Ten universities14; only data from the Ivy League were included in the current analysis. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. The University of Pennsylvania served as the institutional review board of record, with reliance agreements involving the institutional review board of each site, and informed consent was obtained for each student-athlete before the start of each athletic season.

Table 1.

Student-Athlete Characteristics

|

|

Men (n = 1209) | Women (n = 765) |

P Value |

| Mean ± SD | |||

| Age, y | 19.96 ± 1.3 | 19.57 ± 1.2 | <.001 |

| Time competing in sport, y | 10.50 ± 4.1 | 9.32 ± 4.7 | <.001 |

| No. (%) | |||

| History of previous concussion(s) | .27 | ||

| 0 | 562 (46.5) | 382 (49.9) | |

| 1 | 354 (29.3) | 211 (27.6) | |

| 2 | 175 (14.5) | 92 (12.0) | |

| ≥3 | 118 (9.7) | 80 (10.5) | |

| Received academic accommodations while returning to academics? Yesa | 354 (48.8) | 281 (57.5) | .003 |

A total of 761 (male = 483, female = 278) cases had missing information.

Operational Definitions

Concussion

An SRC was defined using the “Concussion in Sport” guidelines4 as a traumatic brain injury induced by biomechanical forces resulting in clinical signs and symptoms. Athletic trainers (ATs) worked in collaboration with team physicians at each school to identify and record SRCs in student-athletes who were diagnosed by a physician within the sports medicine or athletics department. At each school, the team physician made a clinical SRC diagnosis using best-practice guidelines for SRC management decisions. Each injury event was not a self-reported concussion but rather a clinical diagnosis noted in the athlete's electronic medical record.

Clinical Recovery Outcomes

Team physicians, ATs, or both made decisions for return to academics and activity based on SRC management protocols at each institution. Inherently, SRC management protocols may not have been identical across institutions; however, similar to the diagnosis of concussion, team physicians and ATs followed best-practice guidelines for SRC management decisions set forth by the National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement3 and Concussion in Sport Group.4 Study team members obtained dates for each clinical outcome (eg, symptom resolution, academic return, return to limited sport participation, return to full sport participation) of student-athletes diagnosed with an SRC. Time to symptom resolution was defined as the time between the date when the concussive injury occurred and when the athlete reported being symptom free. The time to return to academics was identified as the time from the date when the concussive injury occurred to the date when the athlete returned to full academic participation. In addition, if athletes received academic accommodations during their return to academics, study team members indicated this using a binary response (yes or no) in the database. Time to return to limited sport participation was determined as the time from the date when the concussive injury occurred to the date when the athlete returned to limited athletic participation (eg, the start of the return-to-play stepwise progression). Time to return to full sport participation was calculated as the time from the date when the concussive injury occurred to the date when the athlete was cleared to return to full athletic participation (eg, the date the athlete completed his or her stepwise return-to-play progression).

Procedures

Data-collection procedures for the registry database of the Ivy League–Big Ten Epidemiology of Concussion Study were described previously.14 Athletic trainers provided data regarding the characteristics, date of injury, and clinical recovery outcomes for student-athletes who sustained an SRC at each individual site during the 2013–2014 through 2018–2019 academic years. Sport-related concussions resulting from participation in Ivy League sports only during the 2013–2014 to 2018–2019 academic years were included because of complete participation by all 8 Ivy League schools for these years and because differences among conferences may have been a factor in recovery time. Clinical recovery outcomes for each injury event consisted of the dates for (1) symptom resolution, (2) return to academics, (3) return to limited sport participation, and (4) return to full sport participation as reported in the database by ATs tracking SRC recovery for each athlete. Return-to-athletic activity outcomes were separated into limited sport participation (date of sport-specific exercise resumption) and full sport participation (date of full sport participation resumption without restrictions, including full-contact practice and full competition).

Student-athletes were censored at the end of each academic year and, thus, may have reached these outcomes at later dates. (Censored refers to the fact that we “stopped” their time so that possible influencing factors would not contribute to the final time outcome.) In addition, censoring occurred in some cases when athletes were lost to follow-up at the end of the season, when leaving sports, etc. Given censoring, follow-up data were not available for symptom resolution in 19.1% (n = 377) of cases, return to full academics in 25.2% (n = 498) of cases, return to limited sport participation in 14.5% (n = 287) of cases, and return to full sport participation in 16.9% (n = 333) of cases. In addition, 38.6% (n = 761) of cases had missing information regarding academic accommodations.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to present participant characteristics and clinical recovery outcome measures across men's and women's collegiate sports in the Ivy League. We conducted independent-samples t tests to analyze age and years of competition and χ2 tests to analyze categorical variables (eg, concussion history, academic accommodations) to test for differences between male and female student-athletes. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to estimate the time (in days) between the date of injury and each recovery outcome (ie, symptom resolution, return to academics, return to limited sport participation, return to full sport participation) by sex by sport. The Peto test was calculated to compare differences in the timing of each recovery outcome between male and female athletes. In addition, to explore and account for the role that concussion history may have played, Kaplan-Meier survival curves and the Peto test were applied to estimate and compare the time (in days) between the date of injury and each recovery outcome by concussion history separately for male and female athletes. We then performed similar analyses for each sport while stratifying by concussion history to examine sex differences in the timing of each recovery outcome after accounting for concussion history. We used Stata (version 16; StataCorp LLC) statistical software for all analyses, and the α level was set a priori at .05.

RESULTS

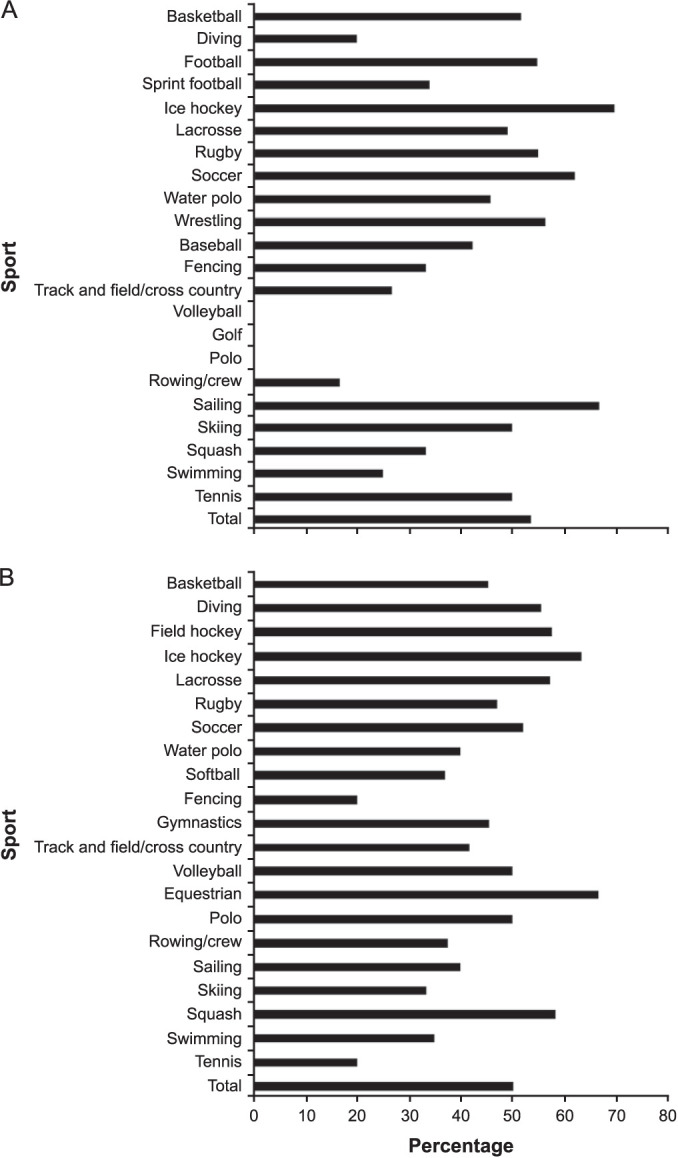

A total of 1974 student-athletes (men = 1209 [61.2%], women = 765 [38.8%]) sustained an SRC during the 2013–2014 through 2018–2019 academic years; 52.2% (n = 1030) reported at least 1 previous concussion. We observed differences between men and women for age (t1956 = −6.745, P < .001), years competing in sport (t1956 = −4.647, P < .001), and academic accommodations received (χ2 = 8.913, P = .003). Concussion history did not differ by sex (χ2 = 3.943, P = .27). The total counts and proportions of male and female student-athletes who sustained an SRC in each sport are shown in Table 2. The incidence of sustaining an SRC was highest in male and female student-athletes in contact sports (93.4% [n = 1101] and 79.2% [n = 552], respectively) as opposed to noncontact sports (2.1% [n = 26] and 9.0% [n = 69], respectively). The proportion of men and women within each sport who had a previous history of ≥1 concussion is displayed in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Concussions Stratified by Sport and Sex for Student-Athletes Participating in Ivy League Sports Between the 2013–2014 and 2018–2019 Academic Years

| Classification and Sport |

No. of Concussions (%)a |

|

| Men (n = 1209) |

Women (n = 765) |

|

| Contact sports | ||

| American football | 487 (40.3) | 0 |

| Basketball | 62 (5.1) | 64 (8.4) |

| Diving | 5 (0.4) | 9 (1.2) |

| Field hockey | 0 | 59 (7.7) |

| Ice hockey | 122 (10.1) | 93 (12.2) |

| Lacrosse | 114 (9.4) | 75 (9.8) |

| Rugby | 71 (5.9) | 134 (17.5) |

| Soccer | 87 (7.2) | 94 (12.3) |

| Sprint football | 50 (4.1) | 0 |

| Water polo | 35 (2.9) | 30 (3.9) |

| Wrestling | 96 (7.9) | 0 |

| Overall | 1129 (93.4) | 558 (72.9) |

| Limited contact | ||

| Baseball or softball | 26 (2.2) | 35 (4.6) |

| Fencing | 9 (0.7) | 5 (0.7) |

| Gymnastics | 0 | 44 (5.8) |

| Track and field or cross-country | 15 (1.2) | 12 (1.6) |

| Volleyball | 4 (0.3) | 42 (5.5) |

| Overall | 54 (4.5) | 138 (18.0) |

| Noncontact sports | ||

| Equestrian | 0 | 6 (0.8) |

| Golf | 1 (0.1) | 0 |

| Polo | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) |

| Rowing or crew | 6 (0.5) | 8 (1.1) |

| Sailing | 3 (0.3) | 10 (1.3) |

| Skiing | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.8) |

| Squash | 3 (0.3) | 12 (1.6) |

| Swimming | 8 (0.7) | 20 (2.6) |

| Tennis | 2 (0.2) | 5 (0.7) |

| Overall | 26 (2.1) | 69 (9.0) |

Percentages were calculated from the total number of male or female student-athletes.

Figure 1.

Percentage of A, men's and B, women's sport-related concussion cases with a history of ≥1 previous concussions by sport.

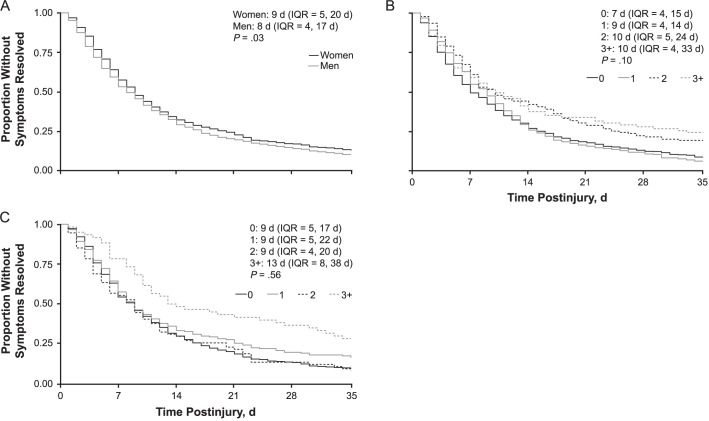

Symptom Resolution

The median time to symptom resolution overall was 9 days (interquartile range [IQR] = 4–18 days): 8 days (IQR = 4–17 days) for men and 9 days (IQR = 5–20 days) for women (P = .03; Figure 2A). At 7 days and 14 days postinjury, 55.1% (n = 880) and 30.7% (n = 490) of 1597 athletes, respectively, were still experiencing symptoms, whereas at ≥35 days postinjury, 11.7% (n = 188) of student-athletes were still experiencing symptoms (Supplemental Table 1, available online at https://doi.org/10.4085/601-20.S1). A greater proportion of women experienced longer symptom resolution (≥7 days = 57.6% [n = 370/642], ≥14 days = 32.6% [n = 209/642], ≥35 days = 13.2% [n = 84/642]) compared with men (≥7 days = 53.4% [n = 510/955], ≥14 days = 29.5% [n = 281/955], ≥35 days = 10.7% [n = 101/955]; Supplemental Table 1) at each time point. The time to symptom resolution was not different by concussion history for men (P = .10); however, those with no previous concussions had a faster time to symptom resolution (Figure 2B). For women, we noted no differences for symptom resolution time by concussion history (P = .56); however, those with ≥3 previous concussions demonstrated longer symptom resolutions (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the time to symptom resolution stratified by the number of previous concussions. A, Both sexes. B, Men. C, Women. Median days and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are presented for each clinical recovery outcome. Peto tests were used to compare differences in concussion histories between A, both sexes, B, men, and C, women.

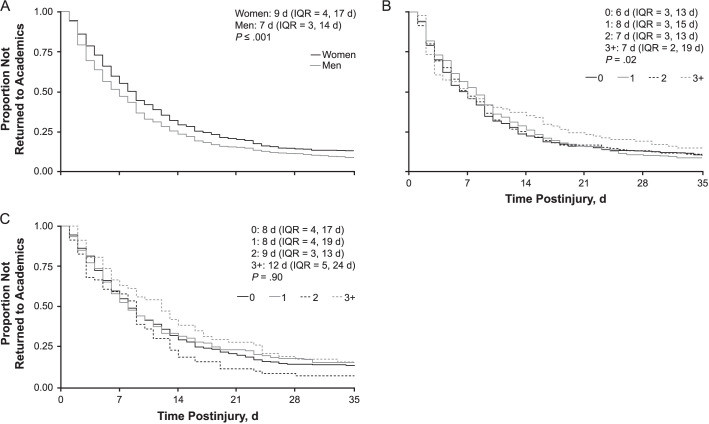

Return to Academics

The median time to return to academics overall was 8 days (IQR = 3–15 days): 7 days (IQR = 3–14 days) for men and 9 days (IQR = 4–17 days) for women (P < .001; Figure 3A). At 7 days and 14 days postinjury, 50.6% (n = 747) and 26.3% (n = 388) of 1476 athletes, respectively, had not returned to academics, whereas at ≥35 days postinjury, 11% (n = 164) had not returned to academics (Supplemental Table 2). A greater proportion of women took longer to return to academics (≥7 days = 55.5% [n = 324/584], ≥14 days = 29.8% [n = 174/584], ≥35 days = 13.5% [n = 79/584]) compared with men (≥7 days = 47.4% [n = 423/892], ≥14 days = 24.0% [n = 214/892], ≥35 days = 9.3% [n = 82/892]; Supplemental Table 2) at each time point. The time to academic return was different among men by the number of previous concussions (P = .02; Figure 3B). For women, we observed no differences for symptom resolution time by concussion history (P = .90); however, those with more previous concussions took longer to return to academics (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the time to return to academics stratified by the number of previous concussions. A, Both sexes. B, Men. C, Women. Median days and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are presented for each clinical recovery outcome. Peto tests were used to compare differences in concussion histories between A, both sexes, B, men, and C, women.

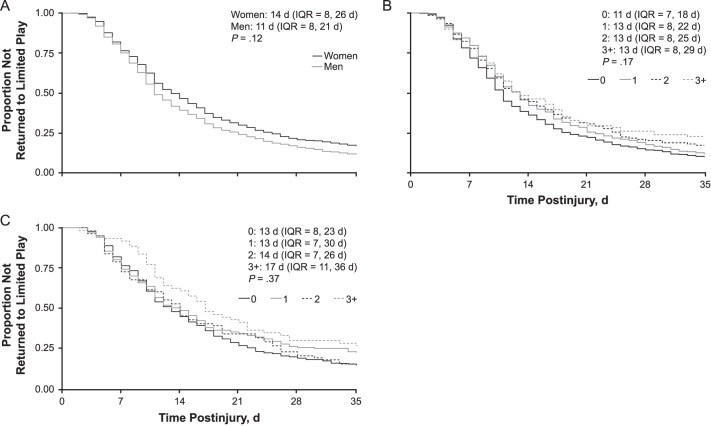

Return to Athletics

The median time to return to limited sport participation overall was 12 days (IQR = 8–23 days): 11 days (IQR = 8–21 days) for men and 14 days (IQR = 8–26 days) for women (P = .12; Figure 4A). At 7 days and 14 days postinjury, 75.9% (n = 1280) and 42.3% (n = 714) of 1687 athletes, respectively, had not returned to limited sport participation, whereas at ≥35 days postinjury, 14.3% (n = 240) had not returned to limited sport participation (Supplemental Table 3). The time to return to limited sport participation did not differ by the number of previous concussions for men (P = .17; Figure 4B) or women (P = .37; Figure 4C). For both men and women, those with more previous concussions demonstrated a longer time to return to limited sport participation.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the time to return to limited play stratified by the number of previous concussions. A, Both sexes. B, Men. C, Women. Median days and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are presented for each clinical recovery outcome. Peto tests were used to compare differences in concussion histories between A, both sexes, B, men, and C, women.

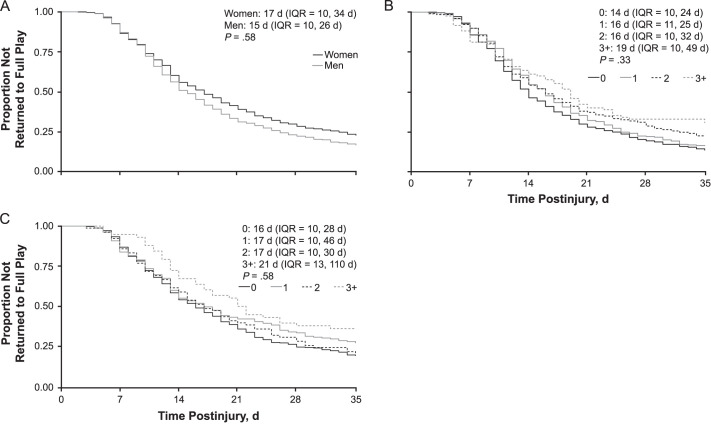

The median time to return to full sport participation overall was 16 days (IQR = 10–29 days): 15 days (IQR = 10–26 days) for men and 17 days (IQR = 10–34 days) for women (P = .58; Figure 5A). A total of 1426 (86.9%) of 1641 student-athletes did not return to full sport participation within 7 days of injury, 53.1% (n = 872) did not return to full sport participation within 14 days, and 19.4% (n = 316) had still not returned at 35 days after their injury (Supplemental Table 4). The time to full return to sport participation was not different by the number of previous concussions for men (P = .33; Figure 5B) or women (P = .58; Figure 5C). For both men and women, those with more previous concussions demonstrated a longer return to full sport participation.

Figure 5.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for the time to return to full play stratified by the number of previous concussions. A, Both sexes. B, Men. C, Women. Median days and interquartile ranges (IQRs) are presented for each clinical recovery outcome. Peto tests were used to compare differences in concussion histories between A, both sexes, B, men, and C, women.

Individual Sport Characteristics

Clinical recovery outcomes by sport are given in Supplemental Tables 1 through 4. American football (n = 487), women's rugby (n = 134), men's ice hockey (n = 122), and men's lacrosse (n = 114) had the highest total number of SRCs (Table 2). Men's and women's basketball, women's equestrian, women's squash, men's soccer, and men's water polo showed the highest proportions of student-athletes experiencing persistent symptoms >35 days postinjury (Supplemental Table 1). For return to academics, men's and women's basketball, men's and women's rugby, men's sailing, men's and women's soccer, and women's squash had the highest proportions of student-athletes not returning to class >35 days after SRC (Supplemental Table 2). Women's equestrian, men's rowing, men's and women's rugby, men's sailing, men's and women's soccer, women's squash, men's swimming, men's and women's tennis, and men's volleyball had the highest proportion of student-athletes not returning to limited sport participation by >35 days postinjury (Supplemental Table 3), whereas many sports had high proportions of athletes who had not returned to full sport participation >35 days postinjury (Supplemental Table 4). Within-sport comparisons yielded longer symptom resolution (P = .03) and return to academics (P = .04) for women's lacrosse compared with men's players; in volleyball, men took longer to return to limited (P = .02) and full (P = .049) sport participation than women. Supplemental Tables 1 through 4 also report on the timing of each outcome by sex for each sport after stratifying by concussion history.

DISCUSSION

In this large multisite study, we assessed timelines for clinical recovery outcomes using a crude analysis for collegiate student-athletes of all sports across all Ivy League institutions. Overall, student-athletes demonstrated a median of 9 days for full symptom resolution, 8 days for return to academics, 12 days to return to limited sport participation, and 16 days to return to full sport participation. Across all time measures, participants in women's sports overall experienced longer symptom resolution trajectories and return to academics compared with men's sports. The median difference of 1 day for symptom resolution between men's and women's sports as a whole may not have been clinically important; therefore, we point to sex differences within sports (eg, lacrosse). Furthermore, although women and men overall did not differ in the median time to return to limited or full sport participation, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves presented a spread between their return-to-play outcomes, particularly those with longer recoveries. In addition, within-sport sex differences were present for return to athletic activity (eg, volleyball). Importantly, the Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed heterogeneity in the recovery progression, providing further support for individualized SRC management strategies. Together, these findings are clinically relevant references for sports medicine providers making SRC management decisions, particularly when advising athletes in different sports, as well as those discussing differences in recovery trajectories with collegiate student-athletes.

We provided information for each clinical outcome measure by sex for each sport in Supplemental Tables 1 through 4 using a crude analysis to offer the most transparent information on the experience of student-athletes with an SRC and separately after stratifying by the concussion history. As shown in Supplemental Tables 1 through 4, sports with a greater proportion of athletes with a longer symptom duration were men's basketball, women's equestrian, men's soccer, women's squash, and men's water polo. For longer academic return, key contributing sports were men's and women's basketball, men's and women's rugby, men's sailing, men's and women's soccer, and women's squash. Similarly, a high proportion of men's and women's athletes across multiple sports still had not returned to limited or full sport participation weeks postinjury. Broadly, 34.7% (n = 568) of athletes had not returned to full sport participation by 3 weeks, 25.1% (n = 409) had not returned by 4 weeks, and 19.4% (n = 316) had not returned by 5 weeks postinjury. Interestingly, these lengthier time frames were not limited to contact sports as would be expected, but they also involved athletes competing in limited-contact or noncontact sports such as sailing, squash, and tennis. Specifically, men's limited-contact and noncontact sports accounted for 4.5% (n = 54) and 2.1% (n = 26) of male cases, respectively; women's limited-contact and noncontact sports accounted for 18.0% (n = 138) and 9.0% (n = 69) of cases, respectively. These proportions were important, as not all SRCs resulted from contact-sport participation; however, differences in proportions warrant cautious interpretations because the representation of male and female participants in some large-roster contact sports, such as football, varied. Accordingly, we did not analyze proportional differences in SRC between men and women at each contact level.

Our findings identifying a longer time to symptom resolution in women than in men were similar to those described in a number of previous studies of both high school and collegiate athletes,10–12 but to our knowledge, we were the first to demonstrate sex differences in the time to return to academics among collegiate student-athletes. Male athletes returned to academics a median of 2 days sooner than did female athletes. Furthermore, 15.8% (n = 141) of men and 20.7% (n = 121) of women had still not returned to academics at 3 weeks (21 days) postinjury, and return persisted beyond 4 weeks (28 days) postinjury for 19.6% (n = 232) of men and 26.7% (n = 226) of women. Whether a 1-day or 2-day difference in the time to return to academics or athletics is considered clinically meaningful has not, to our knowledge, been thoroughly discussed in the literature. Consider, for instance, the effect on injured athletes who may have missed an athletic or scholastic event (eg, competition, examination) because they refrained from activities 1 or 2 more days. More broadly, we found that significant proportions of collegiate athletes returned to academics ≥3 weeks postinjury and men's collegiate athletes returned to academics at a faster pace than women's athletes. Coupled with past research showing similar patterns of greater symptom burdens16–18 and durations,16,19–22 as well as worse academic performance in female athletes compared with male athletes after an SRC,23 we suggested that this prolonged symptom burden likely affects the ability to be in an academic environment, resulting in greater class time being missed. The sex differences in academic return, as well as the variability across sports, in this large sample also supported the development and use of gradual return-to-academics protocols, similar to gradual return-to-activity protocols already used4 for collegiate student-athletes.24 Specifically, a return-to-academics progression for collegiate student-athletes that includes initial cognitive rest, gradual reintroduction of cognitive activity, and gradual reintegration into academics and resumption of a full cognitive workload24 would be helpful in successfully returning athletes to class.

We observed no differences in the overall sample for the time to return to limited and full sport participation between men's and women's sports. Differences in the time to return were evident when examining individual sports, but these did not seem to be associated with sex. These results were consistent with those of other studies in which researchers examined Ivy League sex differences in the time to return to activity. For example, Davis-Hayes et al25 reported similar return-to-play times after SRC between male and female athletes participating in Columbia University athletics over 15 years. Putukian et al14 identified no differences in the time to return to competition of male and female athletes across 4 collegiate sports (ie, basketball, rugby, soccer, water polo). However, other researchers reported sex differences in the time to return to play, although the generalizability of these outcomes was limited by small sample sizes. In particular, Covassin et al11 showed that female collegiate soccer athletes who sustained an SRC in practice took longer to return to play than male soccer athletes, whereas female collegiate basketball athletes who sustained an SRC in competition took longer to return to play than male basketball athletes. These findings, coupled with ours, highlighted the importance of evaluating not only male versus female differences in clinical recovery outcomes but also patterns of clinical recovery outcomes within sports. For example, rules, equipment, and style-of-play differences between men's and women's lacrosse all have the potential to influence student-athletes' recovery from SRC.15

We presented recovery trajectories across sports for male and female Ivy League athletes as part of a large, multisite study. Importantly, this was one of the first investigations to show that, in the absence of sex differences in the time to return to sport participation, men's and women's sport athletes differed in the time for return to academics and symptom resolution. Although we were not able to account for how premorbid differences in symptom presentation between men and women affected SRC outcomes, which was an important consideration given previous sex differences in premorbid symptom presentation,12,26–28 we did note that women's sport athletes demonstrated protracted symptom resolution across sports. Furthermore, across recovery time points, a greater proportion of women's sport athletes still had not returned to class. It may be that a greater symptom burden in women was a mechanism underlying the protracted return to academics. Future researchers should examine whether athletes who present with greater symptom burdens take longer to return to academics and, moreover, whether specific symptom profiles predict who will benefit from gradual return-to-academics protocols and school accommodations.

FUTURE RESEARCH AND LIMITATIONS

Our study provided important information, particularly with respect to return to academics in collegiate athletes, yet some critical limitations must be considered. The sample was drawn from Ivy League schools that had access to similar standards of care. Prior authors have described how the standard of care29 and access to ATs can affect recovery time in athletes.30,31 Furthermore, adolescent athletes, and particularly female athletes, who were able to access specialty care earlier had faster recovery times.13 Similarly, the Ivy League comprises schools that must follow strict SRC management protocols that include immediate removal from sport when a concussion is suspected. Immediate removal from sport resulted in less time missed from sport and shorter symptom durations32; continuing to play postinjury resulted in longer recovery times.33 These results may not be generalizable to other schools, competitive levels, or divisions with more limited access to care and less stringent concussion-identification and -management protocols. In addition, these findings may not directly translate to older or younger populations or to players in other athletic conferences.

With so many sports, which is a strength of this study, we were able to decide whether and how to adjust P values and set a threshold for statistical significance. We did not set a threshold here; instead, we simply reported the P value for each analysis in Supplemental Tables 1 through 4 and focused on the estimates themselves, given that our goal was to inform considerations of whether female and male athletes in a specific sport experienced recovery times that differed to a clinically meaningful extent. Smaller cell sizes, which generally inflate P values, are inevitable when reporting many subgroup analyses.

Furthermore, we did not address whether student-athletes had access to academic accommodations or completed gradual return-to-academics protocols. Gradual return to learn is a relatively new recommendation,4 so it is unlikely that athletes in the sample completed this protocol, particularly for SRCs in earlier years.

Also, we did not aim to account for premorbid symptoms or factors that may have affected symptoms postinjury, as our aim was to simply describe the experience of the athletes rather than investigate and report characteristics associated with variability in timelines to recovery.12,26–28 However, we did evaluate the influence of concussion history on recovery in men and women. Both men and women with a greater number of previous concussions took longer to reach each clinical recovery outcome, yet the only difference was that, for men, the time to return to academics varied by the number of previous concussions. These findings should motivate researchers to investigate other factors (eg, learning disorders, neurodevelopmental disorders, and mood) that may influence recovery after concussion.

CONCLUSIONS

In this large multisite study, we identified clinical recovery outcome trajectories for collegiate student-athletes in all sports across all Ivy League institutions. Women's sport student-athletes experienced a longer symptom recovery trajectory and return to academics compared with student-athletes in men's sports. However, the time of return to limited or full sport participation did not differ between student-athletes in men's and women's sports. These results support those of previous investigators who suggested a longer symptom burden in female student-athletes, and we were the first to evaluate whether sex differences existed in the return to academics after an SRC. Within-sport comparisons yielded sex differences specifically for symptom resolution and return to academics in lacrosse and return to athletic activity in volleyball. Taken together, sex differences and limited sport-specific differences in SRC recovery trajectories further indicate the need for an individualized approach to clinical management of SRC. Future researchers should continue to evaluate progressive return-to-learn protocols in collegiate student-athletes after SRC.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Site investigators for the study were instrumental in accomplishing this work (listed alphabetically by institution): Russell Fiore, MEd, ATC, Matthew Culp, MA, ATC, and Bryn VanPatten, PhD, ATC (Brown University); William N. Levine, MD, and Natasha Desai, MD (Columbia University); David Wentzel, DO (Cornell University); Kristine A. Karlson, MD (Dartmouth College); Frank Wang, MD (Harvard University); Nicholas Port, PhD (Indiana University); Matthew Saffarian, DO (Michigan State University); Brian Vesci, MA, ATC (Northwestern University); Michael Gay, PhD, ATC (The Pennsylvania State University); Margot Putukian, MD (Princeton University); Carly Day, MD (Purdue University); Matthew B. Wheeler, PhD, and Randy Ballard, ATC (University of Illinois); Andy Peterson, MD, MSPH (University of Iowa); David Klossner, PhD (University of Maryland); Erin Moore, MEd, ATC (University of Minnesota); Art Maerlender, PhD, and Cary Savage, PhD (University of Nebraska–Lincoln); Brian Sennett, MD (University of Pennsylvania); Erin McQuillan, MS, ATC (University of Wisconsin); and Andrew Gotlin, MD, and Stephanie Arlis-Mayor, MD (Yale University).

We acknowledge the athletic staff, research staff, and faculty study contacts at each site for their contributions to the study, including (listed alphabetically by institution) Beth Conroy, MS, ATC (Brown University); Jim Gossett, MS, ATC, and Alexander Goldberg (Columbia University); Katy Harris, ATC (Cornell University); Meredith Cockerell, MS, ATC, and Scott Roy, MS, ATC (Dartmouth College); Taylor Ashcraft, MS, ATC, Chloe Amaradio, MS, ATC, and Bridget Hunt, MSAT, ATC (Harvard University); Nicholas Port, PhD (Indiana University); Katy Rogers, ATC, Chandler Castle, MS, ATC, and Tamaria Hibbler, MS, ATC (Michigan State University); Pete Seidenberg, MD (The Pennsylvania State University); Addam Reynolds, MSW, and Neeta Bauer (Princeton University); Kyle Brostrand, MS, ATC (Rutgers University); Paul Schmidt, MS, ATC, and Aaron Anderson, PhD, MS (University of Illinois); Kathryn Staiert, ATC (University of Iowa); Rebecca Hu and Chris Lacsamana, MEd, ATC (University of Maryland); Suzanne Hecht, MD, and Joi Thomas, MS, ATC (University of Minnesota); Todd Caze, MEd, MA, and Elliot Carlson (University of Nebraska–Lincoln); Emily Dorman, MS, ATC, Jenna Ratka, MS, ATC, and Theresa Soya, MPH (University of Pennsylvania); and Lindsay Snecinski, MS, ATC, Wendy Brunetto, MPH, and Kristen Moriarty, MEd, ATC (Yale University).

We also acknowledge the Big Ten–Ivy League Traumatic Brain Injury Research Collaboration board members: Carolyn Campbell-McGovern, MBA (the Ivy League); Martha Cooper (Big Ten Academic Alliance); Katherine Galvin, JD (Big Ten Academic Alliance); Robin Harris (the Ivy League); Kerry Kenny (Big Ten Conference); David Klossner, PhD (University of Maryland); Keith Marshall, PhD (Big Ten Academic Alliance); Nathan Meier (University of Nebraska–Lincoln); Margot Putukian, MD (Princeton University); Chris Sahley, PhD (Purdue University); Sam Slobounov, PhD (The Pennsylvania State University); Douglas H. Smith, MD (University of Pennsylvania); and Philip Stieg, PhD, MD (Weill Cornell Medical College).

We give special thanks to Martha Cooper (Big Ten Academic Alliance, assistant director and study liaison) and to members of the Study Advisory Committee: Carolyn Campbell-McGovern; Martha Cooper; Emily Dorman; Kerry Kenny; Art Maerlender; James Noble, MD, MS; Margot Putukian; Carry Savage; Jim Torner; and Dave Wentzel.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Found at DOI: https://doi.org/10.4085/601-20.S1

REFERENCES

- 1.Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train . 2007;42(2):311–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuckerman SL, Kerr ZY, Yengo-Kahn A, Wasserman E, Covassin T, Solomon GS. Epidemiology of sports-related concussion in NCAA athletes from 2009–2010 to 2013–2014: incidence, recurrence, and mechanisms. Am J Sports Med . 2015;43(11):2654–2662. doi: 10.1177/0363546515599634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Broglio SP, Cantu RC, Gioia GA, et al. National Athletic Trainers' Association position statement: management of sport concussion. J Athl Train . 2014;49(2):245–265. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.1.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCrory P, Meeuwisse W, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport–the 5th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med . 2017;51(11):838–847. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport, Zurich, November 2012. J Athl Train . 2013;48(4):554–575. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-48.4.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasserman EB, Kerr ZY, Zuckerman SL, Covassin T. Epidemiology of sports-related concussions in National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletes from 2009–2010 to 2013–2014: symptom prevalence, symptom resolution time, and return-to-play time. Am J Sports Med . 2016;44(1):226–233. doi: 10.1177/0363546515610537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeMatteo CA, Randall S, Lin CA, Claridge EA. What comes first: return to school or return to activity for youth after concussion? Maybe we don't have to choose. Front Neurol . 2019;10:792. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chrisman SPD, Lowry S, Herring SA, et al. Concussion incidence, duration, and return to school and sport in 5- to 14-year-old American football athletes. J Pediatr . 2019;207:176–184.e171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Terry DP, Huebschmann NA, Maxwell BA, et al. Preinjury migraine history as a risk factor for prolonged return to school and sports following concussion. J Neurotrauma . 2019;36(1):142–151. doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bretzin AC, Covassin T, Fox ME, et al. Sex differences in the clinical incidence of concussions, missed school days, and time loss in high school student-athletes, part 1. Am J Sports Med . 2018;46(9):2263–2269. doi: 10.1177/0363546518778251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Covassin T, Moran R, Elbin RJ. Sex differences in reported concussion injury rates and time loss from participation: an update of the National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program from 2004–2005 through 2008–2009. J Athl Train . 2016;51(3):189–194. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.3.05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iverson GL, Gardner AJ, Terry DP, et al. Predictors of clinical recovery from concussion: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med . 2017;51(12):941–948. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-097729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Desai N, Wiebe DJ, Corwin DJ, Lockyer JE, Grady MF, Master CL. Factors affecting recovery trajectories in pediatric female concussion. Clin J Sport Med . 2019;29(5):361–367. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Putukian M, D'Alonzo BA, Campbell-McGovern CS, Wiebe DJ. The Ivy League-Big Ten Epidemiology of Concussion Study: a report on methods and first findings. Am J Sports Med . 2019;47(5):1236–1247. doi: 10.1177/0363546519830100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Master CL, Katz BP, Arbogast KB, et al. CARE Consortium Investigators. Differences in sport-related concussion for female and male athletes in comparable collegiate sports: a study from the NCAA-DoD Concussion Assessment, Research and Education (CARE) Consortium. Br J Sports Med . 2021;55(21):1387–1394. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2020-103316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baker JG, Leddy JJ, Darling SR, Shucard J, Makdissi M, Willer BS. Gender differences in recovery from sports-related concussion in adolescents. Clin Pediatr (Phila) . 2016;55(8):771–775. doi: 10.1177/0009922815606417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covassin T, Elbin RJ, Bleecker A, Lipchik A, Kontos AP. Are there differences in neurocognitive function and symptoms between male and female soccer players after concussions? Am J Sports Med . 2013;41(12):2890–2895. doi: 10.1177/0363546513509962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ono KE, Burns TG, Bearden DJ, McManus SM, King H, Reisner A. Sex-based differences as a predictor of recovery trajectories in young athletes after a sports-related concussion. Am J Sports Med . 2016;44(3):748–752. doi: 10.1177/0363546515617746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kostyun RO, Hafeez I. Protracted recovery from a concussion: a focus on gender and treatment interventions in an adolescent population. Sports Health . 2015;7(1):52–57. doi: 10.1177/1941738114555075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller JH, Gill C, Kuhn EN, et al. Predictors of delayed recovery following pediatric sports-related concussion: a case-control study. J Neurosurg Pediatr . 2016;17(4):491–496. doi: 10.3171/2015.8.PEDS14332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berz K, Divine J, Foss KB, Heyl R, Ford KR, Myer GD. Sex-specific differences in the severity of symptoms and recovery rate following sports-related concussion in young athletes. Phys Sportsmed . 2013;41(2):58–63. doi: 10.3810/psm.2013.05.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schneider KJ, Emery CA, Kang J, Schneider GM, Meeuwisse WH. Examining Sport Concussion Assessment Tool ratings for male and female youth hockey players with and without a history of concussion. Br J Sports Med . 2010;44(15):1112–1117. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.071266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wasserman EB, Bazarian JJ, Mapstone M, Block R, van Wijngaarden E. Academic dysfunction after a concussion among US high school and college students. Am J Public Health . 2016;106(7):1247–1253. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall EE, Ketcham CJ, Crenshaw CR, Baker MH, McConnell JM, Patel K. Concussion management in collegiate student-athletes: return-to-academics recommendations. Clin J Sport Med . 2015;25(3):291–296. doi: 10.1097/JSM.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis-Hayes C, Gossett JD, Levine WN, et al. Sex-specific outcomes and predictors of concussion recovery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg . 2017;25(12):818–828. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-17-00276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks BL, Mannix R, Maxwell B, Zafonte R, Berkner PD, Iverson GL. Multiple past concussions in high school football players: are there differences in cognitive functioning and symptom reporting? Am J Sports Med . 2016;44(12):3243–3251. doi: 10.1177/0363546516655095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brooks BL, Silverberg N, Maxwell B, et al. Investigating effects of sex differences and prior concussions on symptom reporting and cognition among adolescent soccer players. Am J Sports Med . 2018;46(4):961–968. doi: 10.1177/0363546517749588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kontos AP, Elbin RJ, Sufrinko A, Marchetti G, Holland CL, Collins MW. Recovery following sport-related concussion: integrating pre- and postinjury factors into multidisciplinary care. J Head Trauma Rehabil . 2019;34(6):394–401. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bretzin AC, Aaron JZ, Douglas JW, Covassin T. Time to authorized clearance from sport-related concussion: the influence of health care provider and medical facility. J Athl Train . 2021;56(8):869–878. doi: 10.4085/JAT0159-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haarbauer-Krupa JK, Comstock DR, Lionbarger M, Hirsch S, Kavee A, Lowe B. Healthcare professional involvement and RTP compliance in high school athletes with concussion brain injury. 2018;32(11):1337–1344. doi: 10.1080/02699052.2018.1482426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McGuine TA, Pfaller AY, Post EG, Hetzel SJ, Brooks A, Broglio SP. The influence of athletic trainers on the incidence and management of concussions in high school athletes. J Athl Train . 2018;53(11):1017–1024. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-209-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asken BM, Bauer RM, Guskiewicz KM, et al. CARE Consortium Investigators Immediate removal from activity after sport-related concussion is associated with shorter clinical recovery and less severe symptoms in collegiate student-athletes. Am J Sports Med . 2018;46(6):1465–1474. doi: 10.1177/0363546518757984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elbin RJ, Sufrinko A, Schatz P, et al. Removal from play after concussion and recovery time. Pediatrics . 2016;138(3):e20160910. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.