Abstract

Background

Few intervention studies have integrated cultural tailoring, parenting, behavioral, and motivational strategies to address African American adolescent weight loss.

Purpose

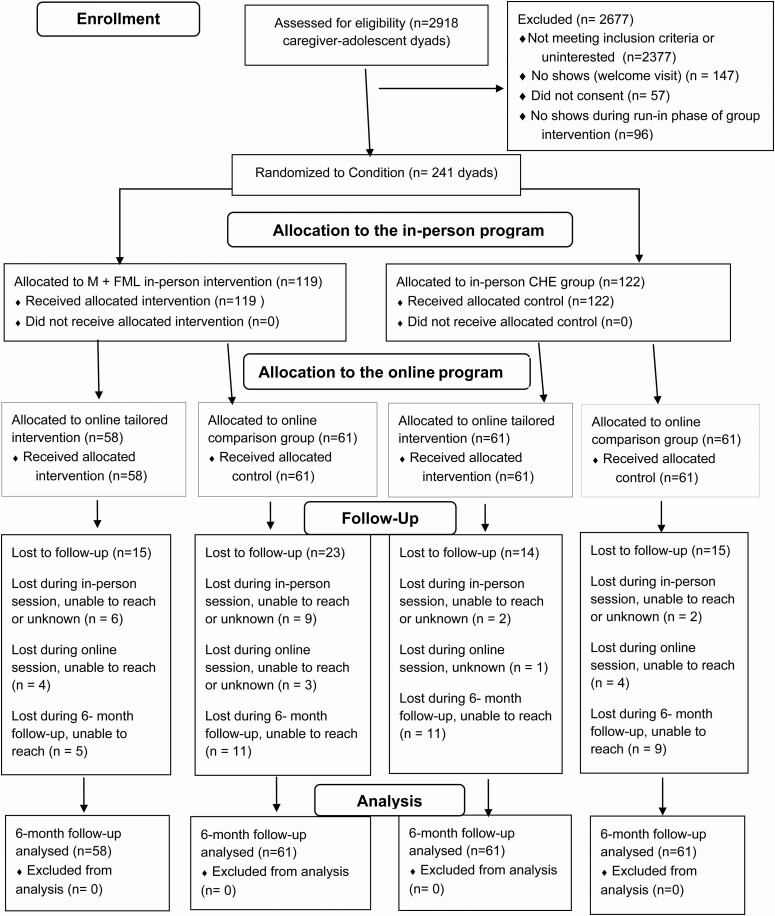

The Families Improving Together (FIT) for Weight Loss trial was a randomized group cohort study testing the efficacy of a cultural tailoring, positive parenting, and motivational intervention for weight loss in overweight African American adolescents (N = 241 adolescent/caregiver dyads).

Methods

The trial tested an 8-week face-to-face group motivational plus family weight loss program (M + FWL) compared with a comprehensive health education control program. Participants were then rerandomized to an 8-week tailored or control online program to test the added effects of the online intervention on reducing body mass index and improving physical activity (moderate-to-vigorous physical activity [MVPA], light physical activity [LPA]), and diet.

Results

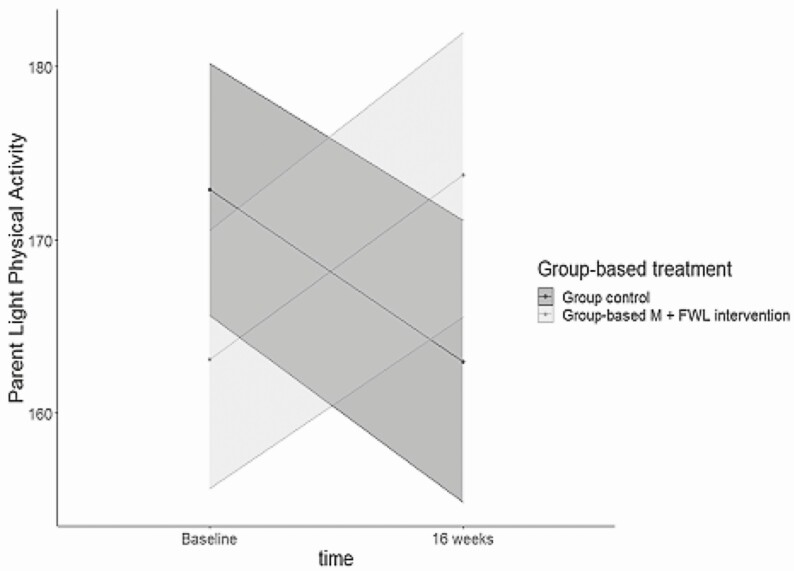

There were no significant intervention effects for body mass index or diet. There was a significant effect of the group M + FWL intervention on parent LPA at 16 weeks (B = 33.017, SE = 13.115, p = .012). Parents in the group M + FWL intervention showed an increase in LPA, whereas parents in the comprehensive health education group showed a decrease in LPA. Secondary analyses using complier average causal effects showed a significant intervention effect at 16 weeks for parents on MVPA and a similar trend for adolescents.

Conclusions

While the intervention showed some impact on physical activity, additional strategies are needed to impact weight loss among overweight African American adolescents.

Keywords: African American, Adolescents, Weight loss, Physical activity, Diet, Family intervention

The FIT trial intervention showed no effect on African American adolescents’ weight loss, however, parents showed a significant intervention-related increase in light physical activity.

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity among African American adolescents is approximately 40% [1]. Adolescent obesity is a risk factor for chronic diseases, including adult obesity, type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, and orthopedic problems [2, 3]. Low rates of physical activity (PA) and poor dietary habits largely contribute to obesity in adolescents [4], and thus various interventions have emphasized PA and dietary behavior change to promote weight loss in youth. Despite efforts to design comprehensive weight loss trials, numerous studies have been unsuccessful at retaining participants and achieving significant reductions in body mass index (BMI), particularly among racial/ethnic minority adolescent populations [5, 6].

Fostering a nurturing, supportive environment within the family may be a critical component for effectively reducing obesity among adolescents [7]. Past research has demonstrated the value of nurturance and positive parenting for improving adolescents’ dietary habits, PA, and weight management skills across a variety of intervention settings including home, schools, healthcare, and communities [7]. Consistent with Family Systems Theory (FST) [8], several family-based weight loss trials have emphasized the importance of positive parenting practices, including authoritative parenting styles (i.e., moderate control, nurturance, monitoring, shared decision-making) [9]. Complementing this approach, Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) [10] and Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [11] highlight the importance of families working together to develop behavioral skills (e.g., goal-setting, self-monitoring) and allowing adolescents to have choice and input to build autonomy support and self-efficacy [7, 12]. Limited studies, however, have integrated parenting, behavioral, motivational strategies, and cultural tailoring approaches to address adolescent obesity and increase engagement in treatment among overweight African American adolescents [9]. We argue that the integration of these theoretical approaches in combination with cultural tailoring are needed to increase engagement and success of weight loss interventions for African American families who have been understudied in previous research. The present study, known as the Families Improving Together (FIT) for Weight Loss trial, integrated these novel theoretical components into a motivational plus family weight loss (M + FWL) intervention.

Previous research has shown that poor participant retention may significantly contribute to ineffective weight loss trials [13] and that there is an increasing need to address program engagement through novel intervention approaches. Some weight loss studies have incorporated various technology-based components, including electronic (eHealth) and mobile health (mHealth), such as websites, mobile apps, text messages, and wearable technology, that may provide more convenient and accessible tools to increase engagement and help sustain long-term behavior change [14, 15]. Supporting this idea, one study found that higher (vs. lower) adolescent participation in an eHealth lifestyle intervention including parents was predictive of lower BMI [16]. While some technology-based trials have focused on parents as the agents of change with mixed success [17, 18] and have included family-based approaches [19, 20], few interventions have focused solely on African American families in general.

A novel feature of the present trial was that an online intervention was culturally tailored and designed to follow a group-based intervention. Few online trials have included African Americans youth [21, 22], however, one mHealth trial focused on parents of inactive youth (59% African Americans) and showed improvements in PA following a 12-week program [23]. Notably, technology-based health behavior interventions that were developed for diverse samples have primarily focused on surface-level approaches to cultural tailoring, including relevant and appropriate content, language, and visuals. We have previously shown that engagement in the FIT online program that included deep structure level cultural tailoring (e.g., ethnic identity, parenting values, etc.) had a significant effect on participant retention among African American families seeking weight loss treatment [24]. Furthermore, research indicates that health promotion programs that incorporate culturally tailored approaches may be more effective for ethnic/racial minorities especially when tailored on deep structural or personal values [25–27] including cultural values and norms [28]. Thus, implementing these strategies may lead to greater engagement and weight loss especially for African American families.

To date, few previous randomized controlled trials have tested the efficacy of eHealth online interventions on weight loss or the combination of face-to-face and eHealth interventions in overweight African American adolescents and their parents/caregivers [20]. A previous pilot study by the authors found that the culturally tailored online program was rated as well-liked and easy to use by African American parents (suggesting high acceptability and feasibility) [29] and that families prefer a mixed modality with only limited face-to-face meetings [30]. Thus, the FIT trial used a unique study design in that it allowed us to test both the effects of a brief group M + FWL curriculum compared with a group comprehensive health education (CHE) control program; and the added dose effects of a culturally tailored online intervention component on reducing BMI in overweight African American adolescents and their caregivers. The primary outcome was adolescent zBMI, with parent BMI, moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA; adolescent and parent), and dietary outcomes (adolescent and parent) included as secondary outcomes. Light PA (LPA) was evaluated as an additional outcome in light of recent research demonstrating the clinical significance of LPA [31]. Our specific research hypotheses were to determine: (a) if an 8-week face-to-face group M + FWL program showed greater improvements in zBMI (MVPA, LPA, diet) as compared with a CHE program in overweight African American adolescents and caregivers, and (b) if the added dose of an 8-week online tailored intervention (vs. control online program) extended the effect of the M+ FWL intervention on improving zBMI (MVPA, LPA, diet) at 16 weeks, and at a 6-month post-intervention follow-up.

Methods

Participants

A total of 241 families (adolescent/caregiver dyads) participated in the FIT trial. Families were recruited through community partnerships such as local churches, pediatric clinics, schools, community events, and through culturally relevant ads [32]. Participants were recruited between 2013 and 2018 and 6-month follow-up measures for the final cohort concluded in Spring of 2019. Participants were recruited from Columbia, SC and surrounding areas (within 60 miles). Families were considered eligible if: (a) they had an African American adolescent between the ages of 11 and 16 years old, (b) the adolescent was overweight or obese, defined as having a ≥85th percentile for age and sex, (c) at least one caregiver living in the household was willing to participate, and (d) the family had internet access. Exclusion criteria included presence of a medical or psychiatric condition that would interfere with PA or dietary behaviors, or currently participating in a weight loss program or taking medication that could interfere with weight loss. All participants signed informed consent and were compensated $110 for their participation in the measurement assessments across all timepoints. The trial was registered through ClinicalTrials.gov (#NCT01796067).

Study Design and Randomization

The FIT trial was a randomized group cohort design that tested the efficacy of the group M + FWL intervention compared with a group CHE program (see Fig. 1). The trial was implemented over 6 years and included 45 treatment/control groups across 16 cohorts (with at least 1 intervention and 1 comparison group per cohort). The study utilized a 2 × 2 factorial design to test the effects of the group-based intervention (M + FWL vs. CHE) and the added dose effects of a tailored online program versus online control program [33]. Groups were designed to include at least two boys in each group. Families were randomized to one of two evenings (Tuesday or Thursday) using a computer-generated randomized algorithm developed and implemented by the Center for Health Communication Research at the University of Michigan. Participants were randomized to an evening to ensure that they had an equal chance of being randomized to the group-based intervention or comparison program and that other schedule-related confounds were not accidentally introduced. Recruited families participated in a 2-week run-in period, which allowed participants to learn more about the program, complete baseline measures, and identify barriers to participation. Next, family evenings were randomized to a group M + FWL or CHE program using a second computer-generated randomized algorithm and were then rerandomized again for Phase 2 of the trial which compared the 8-week online tailoring versus online control program. After completing the online program, families received three online booster sessions (one every 2 months), which corresponded to the online program to which they were randomized.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram for the Families Improving Together (FIT) trial. CHE comprehensive health education; M + FWL motivation + family weight loss intervention.

Theoretical Overview of the Intervention

The intervention essential elements integrated components from FST [8], SCT [10], SDT [11], and cultural tailoring to target weight-related outcomes in African American adolescents. FST emphasizes the importance of positive parenting skills, including parenting style, monitoring, and communication. SDT highlights the importance of allowing adolescents to have input and choice around weight-related behaviors to build enjoyment and an autonomy-supportive climate. SCT provides the framework for using behavioral skills, such as goal-setting and self-monitoring to promote self-efficacy and sustained behavior change. Drawing from these frameworks, the FIT intervention targeted a series of essential elements, including autonomy-support, parent social support, positive communication skills, parental monitoring, and behavioral skills (goal-setting, self-monitoring, problem-solving). The FIT intervention used these components to target weight loss through: (a) increased fruit and vegetable intake, (b) decreased fast food and junk food intake, (c) decreased sugar sweetened beverages, (d) increased PA, and (e) decreased screen time (see [27, 33] for full intervention details). Each in-person session included key content and interactive activities targeting of these behaviors, along with at least one behavioral skill and positive parenting skill. Additionally, to address sociocultural components, the intervention curriculum integrated discussion of cultural topics, including cultural foods with special meaning, the role of emotional eating, the role of women as caregivers, and hairstyle concerns during PA.

Procedures for Group (M + FWL) Intervention

The group M + FWL intervention was delivered by two facilitators (at least one of whom was African American) who received training and was certified on behavioral skills, positive parenting, motivational interviewing, and cultural competency. All facilitators underwent extensive training with the PI and Co-I, including both didactic role-playing components. Twelve facilitators delivered the intervention across the 6-year period. To ensure fidelity across time, facilitators were required to complete quarterly booster training, including reviewing the intervention curriculum and practicing behavioral and parenting skills through role-playing. A total of 5–10 families met each week for 1.5 hrs in groups to discuss topics including positive parenting and communication skills, self-monitoring and goal-setting, energy balance and portion sizes, PA, sedentary behavior, and relapse prevention. Parents and adolescents received personalized daily calorie goals designed to promote gradual weight loss starting in Week 2 of the program. A supportive, interactive group environment was emphasized, and facilitators modeled providing choices and autonomy-support around setting health behavior goals. Parents were encouraged to provide choice to their adolescent and engage in shared decision-making [12]. At the end of each session, family bonding activities were used to encourage positive parenting skills and reinforce behavioral change. Families also received individualized feedback for 15 min each week, including a self-assessment of diet and PA behaviors, discussion of self-monitoring logs with the facilitator, problem-solving, and goal-setting. Makeup sessions were available in person or by phone and covered the dose of the intervention as outlined below.

After completing the group program, caregivers and adolescents completed an online survey, which was used to tailor the online intervention program. The FIT online intervention was completed by the caregiver and was designed to encourage autonomy-supportive parenting skills to support the adolescent’s weight loss goals. Adolescents did not directly participate in the online program, although the program was targeted at increasing specific parenting strategies and actions plans to assist their adolescent with weekly goals. The survey responses from both the caregiver and adolescent were used to tailor the online program on numerous constructs, including cultural factors, personal values, motivation, parent communication style, and current and past adolescent health behaviors (see also [24, 33] for full details).

In the first week of the online program, caregivers developed a calorie-related goal for their adolescent and completed a tailored autonomy-supportive parenting exercise to assess their parenting style and practices. In the following weeks (2–7), caregivers reported on their adolescent’s behavior across six health behaviors and their progress toward their calorie goal, which allowed for weekly tailored feedback. After receiving their weekly feedback, participants were able to select from the following content areas each week, which included a health behavior coupled with a parenting strategy (shown in parentheses): (a) energy balance (active listening), (b) fast food (reverse role play), (c) fruits and vegetables (increasing engagement), (d) PA (escape hatch, volition, choice), (e) time spent sitting (you provide, they decide), and (f) sweet drinks (push vs. pull language). The parenting strategies were intended to provide tailored content for overcoming communication barriers and increasing parental autonomy support.

Within each content session, parents were provided with guidelines for each behavior and tailored information about how their adolescent’s behavior had changed across the program. This information was further tailored on several constructs, including the parent’s personal values and cultural beliefs. The session also integrated cultural topics that the parents had previously identified as important to them, including discussion of cultural foods, spirituality, values, and ethnic identity. Each session ended with parents developing a weekly action plan for applying the parenting skill related to the selected health behavior. After completing the online program, booster sessions allowed for review of topics from the online program across the 6-month follow-up.

Procedures for CHE Program

Groups sessions for the CHE program also took place for 1.5 hrs weekly for 8 weeks and covered topics including stress management, diabetes, hypertension, cancer, media literacy, metabolism, positive self-concept, and sleep. The CHE curriculum did not include parenting skills or behavioral components. Online sessions for the CHE program were also completed by the parent and included tobacco prevention, social media, bullying and peer relationships, oral hygiene, nutrition, depression, sleep, and family stress. Topics were presented in a set order and were not tailored. Parents selected from these same topics for each of the three booster sessions.

Measures

All study measures were collected by certified measurement staff blind to group assignment. Measures were collected at baseline, post-intervention (8 weeks), post-online intervention (16 weeks) and at a 6-month follow-up. Dietary data were not collected at 8 weeks to reduce attention to diet in the CHE condition.

Demographic Information

Demographic information including adolescent age, adolescent sex, parent sex, parent age, parent marital status, number of children in the household, parent education, and annual household income were self-reported by the parent at baseline.

Intervention Process Evaluation Measures

The FIT trial incorporated a comprehensive process evaluation to assess program dose and fidelity of implementation [27, 34]. The FIT process data were assessed for summative purposes by a trained, independent process evaluator using systematic observation of in-person (or recorded) group sessions to assess the reach, dose delivered and the fidelity of intervention implementation [34]. The process evaluation questions were used to summarize: (a) dose delivered (completeness for all components), e.g., To what extent were all planned components of the program provided to program participants? (b) fidelity (for behavioral skills components and social climate components), e.g., To what extent was the social environment autonomy supportive? (c) Reach, e.g., What percentage of the possible target group attended each day of the program? Fidelity data were not obtained in the CHE program. Weekly attendance was recorded by the group facilitator for each session for both intervention and comparison programs, which was based on at least the presence of the caregiver. Caregivers and adolescents attended together most of the time (88% of sessions), and a makeup was offered if one of both family members were absent. Before implementation, the study investigators determined that the minimal acceptable level of fidelity was 3 on a 4-point scale and that the minimum acceptable level for dose was 75% completion rate. For the online program, dose was evaluated by tracking the total number of weekly sessions viewed in tailored and comparison online programs. Consistent with previous online studies, the a priori goal was for parents to complete >50% of the 8 online sessions.

Intervention Outcome Measures

Anthropometric measures

Trained, certified, and blinded measurement staff collected all anthropometric measures. Height (cm) and weight (kg) measurements were obtained using a Seca 880 digital scale and Shorr height board. Waist circumference was also obtained using a nontension tape measure on the natural waistline [35]. All measurements were taken twice and averaged for accuracy. BMI values were calculated using the standard BMI formula (kg/m2). Adolescent BMI scores were converted to BMI zscores using the NutStat (EpiInfo) program based on Centers for Disease Control sex specific 2000 reference curves.

MVPA and LPA

Measures of PA were obtained using 7-day estimates from omnidirectional Actical accelerometers. Both MVPA and LPA were examined. For adolescents, cut-points developed for use in youth populations were used [36] with 60-s epochs to classify accelerometer counts as MVPA (counts above 1,500) and LPA (counts between 100 and 1,500). Twenty consecutive zero counts were coded as nonwear time for adolescents [37]. For parents, previously validated cut-points [38] with 60-s epochs were used to classify accelerometer counts as MVPA (counts above 1,535) and LPA (counts between 110 and 1,534). Sixty consecutive zero counts were coded as nonwear time [39].

Dietary behaviors

Dietary outcomes for adolescents were collected using three random 24-hr dietary recalls conducted with a registered dietician through the Cancer Center at the University of South Carolina. The telephone-administered recalls were completed on two random weekdays and one random weekend day. Parents completed randomized dietary recalls online using the automated self-administered 24-hr dietary assessment tool [40]. Daily fruit and vegetable intake (with fried items removed), energy intake (kcal), and total fat intake (g) were estimated, and each outcome was averaged from the completed recalls.

Data Analysis

The face-to-face phase of the intervention involved treating families in groups, thus random effects models were used to yield unbiased estimates of treatment effects that account for similarities in outcomes within groups. Separate random effects ANCOVAs were used to assess the effect of the group M + FWL intervention on adolescent zBMI at post-intervention (8 weeks), post-online (16 weeks), and 6-month follow-up, with adolescent baseline zBMI included as a covariate to account for the longitudinal design (see Supplementary Materials Section A for additional details and equations). This modeling approach was also applied to assess intervention effects on secondary outcomes at each timepoint (PA and dietary outcomes). In addition to baseline zBMI, age, sex, and income were included as covariates. All primary and secondary outcomes were reviewed for normality and extreme changes between timepoints (see Supplementary Materials Section A).

BMI data were missing for 0.8% of adolescents at baseline and for 14.5%–28.2% at the postassessment timepoints. For parents, BMI data were missing for 1.2% at baseline and for 13.3%–27.0% at the postassessment timepoints. For dietary outcomes, missing data for adolescents included 3.7% at baseline and 18.3%–30.3% at the postassessment timepoints, and 12.8% at baseline and 37.3%–40.2% at the postassessment timepoints for parents. For PA, missing data for adolescents included 5.8% at baseline and 24.0%–46.5% at the postassessment timepoints, and 6.22% at baseline and 22.8%–44.8% at the postassessment timepoints for parents. Multiple imputation was used to address missing data [41], which provides an unbiased estimate of parameters and standard errors and is appropriate for longitudinal trials [42]. The MICE package in R was used to impute the data [43], which allows for the specification of a class variable (group) and the inclusion of a random effect in each of the imputation models. All demographic data, primary and secondary outcomes, and variables of theoretical importance were included in the imputation to minimize the likelihood of biased estimates and meet missing at random assumptions (see Supplementary Materials Section A for further details). This process resulted in 20 imputed datasets. The proposed models for evaluating treatment effects on BMI were conducted using each dataset, with the final parameter estimates and standard errors being pooled across imputations.

PA Outcome Data (MVPA and LPA)

An average daily estimate of adolescent and parent MVPA and LPA at each timepoint was included in the imputation model to account for known associations with BMI. However, to evaluate treatment effects on PA a weighted mixed model approach with variance weighting by the inverse of daily wear time proportions was used [44]. The weighted regression approach is an efficient approach for dealing with missing accelerometry data because cases with a higher proportion of missing wear time are down weighted compared with cases with less missingness, which has been shown to improve precision in estimating accelerometry-estimated PA [44]. See Supplementary Materials for additional details about missing data procedure.

Separate multilevel models were conducted to evaluate MVPA at each of the timepoints, with time dummy-coded as 0 = baseline, 1 = post for each of the later timepoints (8 weeks, 16 weeks, and 6 months). Covariates for adolescent age, adolescent baseline BMI, adolescent sex, parent age, parent baseline BMI, parent income, season (dummy-coded, 1 = winter), and weekend (dummy-coded, 1 = weekend) were also included in the models.

Effects of the Online Intervention for Compliers Versus Noncompliers

A follow-up analysis was conducted looking at effects of the online intervention on BMI and MVPA (adolescents and parents) as a function of compliance with the online intervention. Complier average causal effects (CACE) models [45, 46] were implemented using Mplus v7.1. The treatment effects were estimated for compliers who completed ≥70% of the online sessions as well as for those who were noncompliers. The approach by Jo et al. was used [46], which is based on Holland and Rubin’s causal model framework [47, 48]. This approach allows for an assessment of the causal effect of an intervention for those in the treatment condition who complied with the treatment compared with those in the control condition who would have complied if they had been randomized to treatment with inferences adjusted for the uncertainty in these estimates. CACE models are designed to allow for stronger estimates of the effects for compliers than more commonly applied subgroup analyses [46]. We constrained the effects of the covariates on the outcome to be the same across complier groups [49, 50]. Complier effects were assessed only for the effects of the online intervention because these analyses require prerandomization predictors of compliance which were obtained from the 8-week face-to-face program. For adolescents, sex, age, baseline zBMI, baseline MVPA, baseline dietary outcomes, baseline self-efficacy, and attendance at group sessions were included in the analyses. For parents, variables included parent annual income, parent marital status, baseline of parent MVPA in predicting their MVPA outcome and baseline BMI in predicting their BMI outcome. Previous attendance at the face-to-face sessions was a strong predictor of compliance with the online session. Analyses were conducted with multiply imputed data, with the resulting estimates for each group being combined according to Rubin’s rules [51]. These analyses were only conducted for the primary outcome of BMI and secondary outcome of MVPA for parents and adolescents.

Power

Power was previously calculated for a post-test ANCOVA (controlling for baseline status) using Monte Carlo simulations on our primary outcome of adolescent zBMI [33]. Estimates of effect sizes from previous parent-based interventions were used to guide our targeted effect size to provide a realistic and clinically relevant goal. We estimated power to detect an effect of 0.20 (given that Cohen’s D and zBMI are both scaled by the variance, this equates to a D of 0.20 and a reduction of zBMI of 0.20). However, our final sample size was lower than the anticipated sample size on which initial power estimates were conducted. Thus, we used the model estimated standard errors to calculate the effect size for 80% power to detect differences in adolescent zBMI [52]. We observed power to detect an effect (i.e., reduction in zBMI of) 0.24 for the group M + FWL intervention, 0.25 for the online intervention, and 0.33 for the interaction. These effect sizes are somewhat larger, but not substantially different than the original power analysis.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Demographic baseline characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1. A total of 72.2% of families were retained at the 6-month follow-up (see Fig. 1). For a summary of means and standard deviations of all outcomes across timepoints, see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Table 1.

Descriptive data for the total sample at baseline (N = 241)

| Group Intervention and Online Intervention (N = 58) | Group Intervention and Online Control (N = 61) | Group Control and Online Intervention (N = 61) | Group Control and Online Control (N = 61) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent sex (n, % female) | 41 (70.1%) | 39 (63.9%) | 35 (57.4%) | 38 (62.3%) |

| Adolescent Age M (SD) | 12.81 (1.73) | 13.00 (1.87) | 12.61 (1.63) | 12.90 (1.80) |

| * Adolescent BMI % | 97.54% | 96.22% | 96.35% | 96.45% |

| Parent sex (n, % female) | 55 (94.8%) | 58 (95.1%) | 58 (95.1%) | 60 (98.4%) |

| Parent Age (M, SD) | 44.19 (9.40) | 42.49 (8.59) | 43.21 (8.61) | 42.89 (8.10) |

| * Parent BMI (M, SD) | 36.99 (9.29) | 37.58 (8.59) | 37.98 (9.17) | 38.01 (7.90) |

| * Married (n, %) | 25 (43.1%) | 18 (29.5%) | 22 (36.1%) | 20 (32.8%) |

| Parent Education (n, %) | ||||

| Unreported | 2 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| 9 To 11 Years | 2 (3.4%) | 2 (3.3%) | 2 (3.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| 12 Years | 8 (13.8%) | 10 (16.4%) | 6 (9.8%) | 9 (14.8%) |

| Some College | 26 (44.8%) | 24 (39.3%) | 29 (47.5%) | 20 (32.8%) |

| 4 Year College | 8 (13.8%) | 12 (19.7%) | 11 (18.0%) | 14 (23.0%) |

| Professional | 12 (20.7%) | 13 (21.3%) | 12 (19.7%) | 18 (29.5%) |

| Parent Annual Income (n, %) | ||||

| Unreported | 2 (3.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Less than $10,000 | 4 (6.9%) | 15 (25.9%) | 12 (20.7%) | 5 (8.6%) |

| $10,000-$24,000 | 14 (24.1%) | 14 (20.0%) | 8 (13.8%) | 14 (24.1%) |

| $25,000-$39,000 | 17 (29.3%) | 15 (25.9%) | 14 (24.1%) | 18 (31.0%) |

| $40,000-$54,000 | 9 (15.5%) | 6 (10.3%) | 8 (13.8%) | 8 (13.8%) |

| $55,000-$69,000 | 6 (10.3%) | 5 (8.6%) | 5 (8.6%) | 5 (8.6%) |

| $70,000-$84,000 | 2 (3.4%) | 2 (3.4%) | 4 (6.9%) | 4 (6.9%) |

| $85,000 or greater | 4 (6.9%) | 4 (6.9%) | 9 (15.5%) | 7 (12.1%) |

Note: BMI = Body Mass index.

* Based on imputed baseline values.

Process Evaluation

Attendance rates were similar across the group M + FWL and CHE programs when makeups were included. All cohorts met the overall dose delivered criteria of at least 75% of components delivered (see Supplementary Tables S3 and S4). The majority of cohorts met the fidelity criteria at the facilitator and group level for intervention implementation. Participants in the four online conditions completed a similar number of sessions from 3.84 (SD = 3.18) to 4.93 (SD = 2.95).

Adolescent zBMI (Primary Outcome) and Parent BMI (Secondary Outcome)

For adolescents the random effect ANCOVAs revealed that there were no significant treatment effects for the group M + FWL intervention relative to the CHE program at 8 weeks (Estimate = 0.01, SE = 0.05, p = .76), 16 weeks (Estimate = 0.04, SE = 0.07, p = .59), or 6 months (Estimate = −0.03, SE = 0.11, p = .79; see Table 2). Effect sizes for the group M + FWL treatment effect at 8 weeks (d = 0.051), 16 weeks (d = 0.119), and 6 months (d = −0.064) were small. Furthermore, there was no significant treatment effect for the online tailored intervention versus online control program at 16 weeks (Estimate = 0.03, SE = 0.06, p = .66, d = 0.090) or 6 months (Estimate = −0.06, SE = 0.11, p = .55, d = −0.140), or an interaction between group and online treatment at 16 weeks (Estimate = −0.07, SE = 0.09, p = .45, d = −0.232) or 6 months (Estimate = 0.05, SE = 0.14, p = .74, d = 0.100).

Table 2.

Effects of the M + FWL group and online treatment on adolescent zBMI at 8 weeks, 16 weeks, and 6-month follow-up

| 8 weeks | 16 weeks | 6 months | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | SE | FMI | Estimate | SE | FMI | Estimate | SE | FMI | |

| Fixed effects | |||||||||

| (Intercept) | 2.06* | 0.03 | 0.29 | 2.03* | 0.05 | 0.40 | 2.07* | 0.08 | 0.41 |

| Baseline adolescent zBMI | 0.88* | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.91* | 0.05 | 0.31 | 0.79* | 0.08 | 0.36 |

| Baseline parent BMI | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.32 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.41 |

| Adolescent age | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.35 | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.32 |

| Parent age | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.46 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.37 |

| Adolescent sex | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 0.48 |

| Family income | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.34 | −0.01 | 0.05 | 0.34 | −0.04 | 0.09 | 0.47 |

| Group-based M + FWL | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.30 | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.42 |

| Online-based treatment | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.16 | −0.06 | 0.11 | 0.40 | |||

| Group × online treatment | −0.07 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.26 | |||

| Random effects | |||||||||

| Intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

| Residual | 0.27 | 0.30 | 0.45 | ||||||

| Group | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.08 |

BMI body mass index; FMI fraction of missing information; M + FWL motivation + family weight loss intervention.

*p < .05.

For parent BMI, there was no significant treatment effect for the M + FWL intervention relative to the CHE program at 8 weeks (Estimate = 0.49, SE = 0.79, p = .54, d = 0.096), 16 weeks (Estimate = 1.44, SE = 1.78, p = .42, d = 0.245), or 6 months (Estimate = −0.33, SE = 1.51, p = .83, d = −0.047), and no significant treatment effect for the online tailored intervention relative to the online control program at 16 weeks (Estimate = 0.01, SE = 1.44, p = .99, d = 0.001) or 6 months (Estimate = −1.03, SE = 1.53, p = .50, d = −0.149), and no interaction between group M + FWL and online treatment at 16 weeks (Estimate = −1.13, SE = 2.04, p = .58, d = 0.192) or 6 months (Estimate = 0.70, SE = 2.10, p = .74, d = 0.100).

Adolescent and Parent MVPA and LPA (Secondary Outcomes)

For adolescents, the weighed mixed model revealed that there were no significant effects for the group M + FWL intervention, the tailored online intervention, or crossover effect between treatments in predicting adolescent MVPA or LPA at 8 weeks, 16 weeks, or 6-month follow-up (see Supplementary Tables S5 and S6). For parents, at 8 weeks, there was no significant effect for the group M + FWL intervention on parent MVPA (see Supplementary Tables S7 and S8). At 16 weeks, there was a significant interaction between the group M + FWL intervention and time for parent LPA (B = 33.017, SE = 13.115, p = .012, d = 0.671; see Supplementary Table S8). Among parents in the group M + FWL intervention there was an increase in LPA from baseline to post-online, whereas for those in the CHE program there was a decrease in LPA (see Fig. 2). No other effects were significant for LPA or at the 6-month follow-up.

Fig. 2.

Interaction between group-based treatment at 16 weeks (B) when predicting parent light physical activity (LPA). M + FWL motivation + family weight loss intervention.

Adolescent and Parent Dietary Outcomes (Secondary Outcome)

There were no significant effects for the group M + FWL group-based intervention, the tailored online intervention, or crossover effect between treatments in predicting any dietary outcomes (kcal, total fat, or fruit and vegetables) at 16 weeks or 6 months for parents or adolescents.

Online Tailored Intervention Effects on BMI and MVPA for Compliers Versus Noncompliers

The CACE models showed no significant treatment effects on BMI for either adolescents (zBMI for compliers: B = −0.02, SE = 0.03, p = .56, for noncompliers: B = −0.01, SE = 0.11, p = .97) or parents (BMI for compliers: B = 0.17, SE = 0.36, p = .64, for noncompliers: B = −1.01, SE = 2.72, p = .71). For MVPA, adolescents who were compliers showed a 10 min/day increase (B = 10.50, SE = 6.54, p = .11). Adolescents who were noncompliant showed almost a 7-min decrease in MVPA (B = −6.80, SE = 10.73, p = .53). Parents showed a significant effect for MVPA, with a nearly 8-min increase in MVPA for compliers (B = 7.94, SE = 2.45, p = .001) and a similar decrease in MVPA for noncompliers (B = −7.57, SE = 5.07, p = .14).

Discussion

The findings from this trial showed there were no significant effects for BMI or diet for adolescents or parents for either the group-based or online tailored intervention. However, there was a significant effect of the group M + FWL intervention on parent LPA at 16 weeks. Parents in the group M + FWL intervention showed an increase in LPA, whereas parents in the CHE group showed a decrease in LPA. Secondary analyses showed treatment effects at 16 weeks for parents on MVPA outcomes using CACE completer analyses and a similar trend for adolescents.

We found no intervention effects for BMI, the primary outcome of interest, for either adolescents or parents. Previous studies have shown that weight loss programs have resulted in improved health behaviors (e.g., diet, PA) among adolescents, including underserved African American adolescents [20, 23]. However, to date, few previous randomized controlled trials have shown significant effects on BMI among adolescents [20]. For example, one study using a cluster randomized design with African American and white youth (7–10 years of age) showed no significant reduction in BMI at 12 weeks or 9 months follow-up [6]. Another study also reported no overall effect of a randomized controlled weight loss intervention trial on percent overweight in a multiethnic group of adolescents [53]. Importantly, previous research has found that African American youth experience high levels of psychological stress [54], which may tax self-regulatory resources for engaging in health-promoting behaviors (e.g., healthy eating, exercise) [55]. We conducted follow-up interviews with 30 families from the FIT trial and found that stress was a major barrier to program engagement [56]. Thus, understanding and addressing which stress-related risk factors are most impactful for adolescents with obesity may be critical for future continued efforts to develop and implement efficacious prevention and treatment programs.

Several studies have shown through completers analyses greater interventions effects on BMI [5, 53] or moderated intervention effects based on individual factors (e.g., engagement) [57]. In addition, some studies have shown positive treatment effects of weight loss programs among adolescents. However, these programs have typically targeted younger preadolescent youth and have often not included racial/ethnic minority adolescents in their studies [58, 59]. Most studies have also not used CACE analyses, which is a less biased approach for evaluating differences in those who compete the program versus drop out. The present study used attendance during the face-to-face phase of the FIT program as a predictor for assessing compliance. Importantly, while this approach provided some insight into why the intervention may have been more effective for some families, it is a relatively simplistic measure of engagement. One of the challenges with the CACE approach is that it requires a measure of engagement that can be assessed in both the intervention and control programs. Thus, future interventions may benefit from study designs that allow for measures of engagement across all conditions (e.g., attendance during multiple stages, such as run-in/prerandomization, or measuring motivation or perceived barriers to participation at baseline).

In the present study, parents were more likely to increase their LPA as a result of the intervention program. This is one of the few trials, to date, to explore LPA intensities as an outcome among African American families and this may be important given that those with overweight or obesity may be more comfortable engaging in a lighter intensity of activity than MVPA. Parents may have found LPA to be less time consuming (e.g., less likely to require a change of clothes) and easier to fit into daily routines (e.g., through daily activities like household chores). Additionally, LPA is less likely to produce excessive perspiration, which may be more appealing to African American women for whom hairstyle is a frequently reported barrier to PA [60]. Importantly, in a recent systematic review, it was reported that objectively measured PA was the most robust indicator of health outcomes in school-age youth [61], including PA of all intensity levels. A growing literature has shown that an increase in a 10-min bout of overall PA is associated with a significant reduction in diabetes risk and premature death [62, 63], thus the effects in the FIT trial on LPA may be especially important to consider for future interventions.

An interesting finding in the present study was the significant increase in parent MVPA using the CACE analyses with a similar trend among adolescents. It is important to note that these are secondary analyses that would need be replicated but which are more stringent that traditional subgroup approaches [46]. Although this finding was not significant for adolescents it is consistent with past studies in racial/ethnic minority youth. For example, in a family-based diabetes prevention trial of African American youth, a culturally tailored nutrition and exercise program for diabetes prevention resulted in significant increases in walking and decreases in BMI at a 1-year follow-up [64]. In contrast, another study found no significant different in PA (or BMI) among ethnically diverse youth after a family-based versus parent only intervention [65]. One study of primarily white youth, however, showed that an internet-based family-based intervention did result in increased PA, although no control group was included [66]. Similar increases in PA have also been demonstrated in young white children [67]. Taken together these findings suggest that there is a growing evidence base supporting the focus on PA outcomes in high risk and overweight youth.

A strength of the FIT trial is a 72% retention rate along with high program dose and fidelity of implementation. Previous studies have reported low engagement among ethnic/racial minority families in weight loss programs [33]. However, one study [16] found greater engagement by primarily white adolescents in a family-based eHealth lifestyle intervention and improvements in BMI. Similar to the FIT trial, some technology-based trials have focused on parents as the agents of change, which have yielded mixed results [17, 18]. Improving the quality, duration, and depth of tailoring of eHealth interventions for adolescents and parents may increase success rates [18]. The tailored online intervention in the FIT trial was unique in that it targeted multiple theoretical variables [33] and our research team has shown that exposure to the culturally tailored online program had a significant effect on participant retention [24]. This is consistent with growing evidence that health promotion programs with culturally tailored and targeted approaches may be more effective for increasing engagement in racial/ethnic minorities [25, 26].

There were no effects of our trial on improving dietary outcomes. This finding is consistent with other studies that have shown minimal impacts on dietary outcomes in family-based weight loss studies among overweight ethnic/racial minority adolescents [5, 65]. Many interventions targeting changes in dietary intake experience major methodological challenges, given that research indicates that between 8 and 32 recalls are recommended for adequate reliability [68]. However, a recent publication by our group also showed a moderating effect of the parenting factors and the group M + FWL intervention on improving the frequency of family mealtime [69]. An increasing number of investigators are advocating for a focus on the quality of diet and family mealtime as a protective factor in health promotion programs.

There are several limitations to the present study that should be noted. Our findings are limited given that the sample included overweight or obese African American adolescents from the Southeast USA, which may limit generalizability. In addition, although we used three random dietary recalls, growing evidence suggests that this limited number of dietary recalls, may not be adequate for demonstrating reliability [68]. Additionally, while the group-based intervention had a positive impact on parent LPA, PA was measured through accelerometers only. As a result, we are not able to draw conclusions about the types of activities participants engaged in (e.g., structured physical activities vs. reducing sedentary time at work or school). Given that our study was limited in only focusing on physical health-related outcomes (BMI, PA, diet) future research should evaluate the cascading effects of these comprehensive theoretical interventions on mental and social well-being [70]. For example, in a recent qualitative follow-up study we reported ripple effects of the group M + FWL intervention on improving positive communication and social support among adolescents and their parents [71].

In summary, although this trial did not result in the overall changes in BMI, the trial used a unique study design and online cultural tailoring approach to target weight-related outcomes and health behaviors among a high-risk group of overweight African American adolescents. While this trial did not show effects on BMI, the primary outcome, the results pointed to improvements in both LPA and MVPA in parents and a similar trend for MVPA in the youth. Addressing barriers and stress-related issues in a more fully integrated way could be critical for future interventions. This study is the first to test the effects of a mixed modality (face-to-face and tailored online) on health outcomes in African American adolescents and their families to increase engagement. Our study is consistent with past research that supports both technology-based interventions and tailored interventions in health promotion programs targeting racial/ethnic minority youth. Finally, our study showed a moderate to high retention rate and provides support for future interventions to continue to integrate innovative methods to increase engagement to ultimately impact health outcomes in underserved racial/ethnic minority adolescents.

Supplementary Material

Compliance with Ethical Standards This study adhered to appropriate ethical standards and the Helsinki Declaration.

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Authors Dawn K. Wilson, Allison M. Sweeney, M. Lee Van Horn, Heather Kitzman, Lauren H. Law, Haylee Loncar, Colby Kipp, Asia Brown, Mary Quattlebaum, Tyler McDaniel, Sara M. St. George, Ron Prinz, and Ken Resnicow declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Authors’ Contributions Dawn K. Wilson: Principal Investigator of the FIT trial and provided oversight on all aspects of the project including the theoretical framework, analyses, reporting of results, and writing of the manuscript. Allison M. Sweeney: assisted with all aspects of the project including analyses, reporting of results and writing of the manuscript. M. Lee Van Horn: Co-I and senior statistician provided oversight with collection of data, conceptualizing of the project, data analyses related to the outcome data, missing data, and CACE analyses, as well as the writing of the manuscript. Heather Kitzman: served as a Co-I and assisted with the study conceptualization, intervention oversight, and writing of the manuscript. Lauren H. Law: assisted with intervention oversight, measures, and the writing of the manuscript. Haylee Loncar: assisted with the recruitment, measures, intervention implementation, and writing of the manuscript. Colby Kipp: assisted with the measures, intervention implementation, process evaluation, and writing of the manuscript. Asia Brown: assisted with recruitment, measures, intervention implementation, and writing of the manuscript. Mary Quattlebaum: assisted with the conceptualization of the study, conducting literature reviews, and writing of the manuscript. Tyler McDanie:l assisted with process evaluation, intervention implementation, and writing of the manuscript. Sara M. St. George: assisted with the overall conceptualization of the study, intervention development and implementation, and writing of the manuscript. Ron Prinz: served as a Co-I and assisted with the overall conceptualization of parenting intervention in the study, with the writing of the manuscript. Ken Resnicow: served as a Co-I and assisted with the conceptualization of the study, tailoring of the online intervention, providing oversight on data analyses, and with the writing of the manuscript.

Ethical Approval This study was approved by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent This study followed appropriate informed consent procedures and was approved by the University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board.

Contributor Information

Dawn K Wilson, Department of Psychology, Barnwell College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Allison M Sweeney, College of Nursing, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

M Lee Van Horn, Department of Education, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM, USA.

Heather Kitzman, Baylor Scott & White Health and Wellness Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Lauren H Law, Department of Psychology, Barnwell College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Haylee Loncar, Department of Psychology, Barnwell College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Colby Kipp, Department of Psychology, Barnwell College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Asia Brown, Department of Psychology, Barnwell College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Mary Quattlebaum, Department of Psychology, Barnwell College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Tyler McDaniel, Department of Psychology, Barnwell College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Sara M St. George, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL, USA.

Ron Prinz, Department of Psychology, Barnwell College, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA.

Ken Resnicow, Department of Health Behavior and Education School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant (R01 HD072153) funded by the National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development to Dawn K. Wilson, and by a grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (T32 GM081740).

References

- 1. Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Martin CB, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence by race and Hispanic origin—1999–2000 to 2017–2018. JAMA. 2020;324:1208–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pulgaron ER, Delamater AM. Obesity and type 2 diabetes in children: epidemiology and treatment. Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kelsey MM, Zaepfel A, Bjornstad P, Nadeau KJ. Age-related consequences of childhood obesity. Gerontology. 2014;60:222–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee EY, Yoon KH. Epidemic obesity in children and adolescents: risk factors and prevention. Front Med. 2018;12:658–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moore SM, Borawski EA, Love TE, et al. Two family interventions to reduce BMI in low-income urban youth: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20182185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berry DC, Schwartz TA, McMurray RG, et al. The family partners for health study: a cluster randomized controlled trial for child and parent weight management. Nutr Diabetes. 2014;4:e101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wilson DK, Sweeney AM, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Gause H, St George SM. Promoting social nurturance and positive social environments to reduce obesity in high-risk youth. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2017;20:64–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Broderick CB. Understanding Family Process: Basics of Family Systems Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kitzman-Ulrich H, Wilson DK, St George SM, Lawman H, Segal M, Fairchild A. The integration of a family systems approach for understanding youth obesity, physical activity, and dietary programs. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2010;13:231–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Vol. 16. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986:2–xiii, 617. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55:68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Law LH, Wilson DK, St George SM, Kitzman H, Kipp CJ. Families Improving Together (FIT) for weight loss: a resource for translation of a positive climate-based intervention into community settings. Transl Behav Med. 2020;10:1064–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dhaliwal J, Nosworthy NM, Holt NL, et al. Attrition and the management of pediatric obesity: an integrative review. Child Obes. 2014;10:461–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DeSilva S, Vaidya SS. The application of telemedicine to pediatric obesity: lessons from the past decade. Telemed J E Health. 2021;27:159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tully L, Burls A, Sorensen J, El-Moslemany R, O’Malley G. Mobile health for pediatric weight management: systematic scoping review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e16214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tu AW, Watts AW, Chanoine JP, et al. Does parental and adolescent participation in an e-health lifestyle modification intervention improves weight outcomes? BMC Public Health. 2017;17:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wald ER, Ewing LJ, Moyer SCL, Eickhoff JC. An interactive web-based intervention to achieve healthy weight in young children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57:547–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hammersley ML, Jones RA, Okely AD. Parent-focused childhood and adolescent overweight and obesity eHealth interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Laura L. Technology as a platform for improving healthy behaviors and weight status in children and adolescents: a review. Obes Open Access. 2015;1:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rose T, Barker M, Maria Jacob C, et al. A systematic review of digital interventions for improving the diet and physical activity behaviors of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:669–677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verdaguer S, Mateo KF, Wyka K, Dennis-Tiwary TA, Leung MM. A web-based interactive tool to reduce childhood obesity risk in urban minority youth: usability testing study. JMIR Form Res. 2018;2:e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Callender C, Liu Y, Moore CE, Thompson D. The baseline characteristics of parents and African American girls in an online obesity prevention program: a feasibility study. Prev Med Rep. 2017;7:110–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Newton RL Jr, Marker AM, Allen HR, et al. Parent-targeted mobile phone intervention to increase physical activity in sedentary children: randomized pilot trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2014;2:e48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilson DK, Sweeney AM, Law LH, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Resnicow K. Web-based program exposure and retention in the families improving together for weight loss trial. Ann Behav Med. 2019;53:399–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kreuter MW, Lukwago SN, Bucholtz RD, Clark EM, Sanders-Thompson V. Achieving cultural appropriateness in health promotion programs: targeted and tailored approaches. Health Educ Behav. 2003;30:133–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Wilson DK. New perspectives on health disparities and obesity interventions in youth. J Pediatr Psychol. 2009;34:231–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Alia KA, Wilson DK, McDaniel T, et al. Development of an innovative process evaluation approach for the Families Improving Together (FIT) for weight loss trial in African American adolescents. Eval Program Plann. 2015;49:106–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Resnicow K, Davis R, Zhang N, et al. Tailoring a fruit and vegetable intervention on ethnic identity: results of a randomized study. Health Psychol. 2009;28:394–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson DK, Alia KA, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Resnicow K. A pilot study of the effects of a tailored web-based intervention on promoting fruit and vegetable intake in African American families. Child Obes. 2014;10:77–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kitzman-Ulrich HE, Wilson DK, Lyerly JE. Qualitative perspectives from African American youth and caregivers for developing the Families Improving Together (FIT) for weight loss intervention. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. 2016;4:263–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Chastin SFM, De Craemer M, De Cocker K, et al. How does light-intensity physical activity associate with adult cardiometabolic health and mortality? Systematic review with meta-analysis of experimental and observational studies. Br J Sports Med. 2019;53:370–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Huffman LE, Wilson DK, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Lyerly JE, Gause HM, Resnicow K. Associations between culturally relevant recruitment strategies and participant interest, enrollment and generalizability in a weight-loss intervention for African American families. Ethn Dis. 2016;26:295–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wilson DK, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Resnicow K, et al. An overview of the Families Improving Together (FIT) for weight loss randomized controlled trial in African American families. Contemp Clin Trials. 2015;42:145–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wilson DK, Griffin S, Saunders RP, Kitzman-Ulrich H, Meyers DC, Mansard L. Using process evaluation for program improvement in dose, fidelity and reach: the ACT trial experience. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2009;6:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lean ME, Han TS, Morrison CE. Waist circumference as a measure for indicating need for weight management. BMJ. 1995;311:158–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Puyau MR, Adolph AL, Vohra FA, Zakeri I, Butte NF. Prediction of activity energy expenditure using accelerometers in children. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:1625–1631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cain KL, Sallis JF, Conway TL, Van Dyck D, Calhoon L. Using accelerometers in youth physical activity studies: a review of methods. J Phys Act Health. 2013;10:437–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Trumpeter NN, Lawman HG, Wilson DK, Pate RR, Van Horn ML, Tate AK. Accelerometry cut points for physical activity in underserved African Americans. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Troiano RP, Berrigan D, Dodd KW, Mâsse LC, Tilert T, McDowell M. Physical activity in the United States measured by accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Subar AF, Kirkpatrick SI, Mittl B, et al. The Automated Self-Administered 24-hour dietary recall (ASA24): a resource for researchers, clinicians, and educators from the National Cancer Institute. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1134–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Schafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London, UK: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Enders CK. Analyzing longitudinal data with missing values. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56:267–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. van Buuren S, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. Mice: multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. J Stat Softw. 2010:1–68. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yue Xu S, Nelson S, Kerr J, et al. Statistical approaches to account for missing values in accelerometer data: applications to modeling physical activity. Stat Methods Med Res. 2018;27:1168–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peugh JL, Strotman D, McGrady M, Rausch J, Kashikar-Zuck S. Beyond intent to treat (ITT): a complier average causal effect (CACE) estimation primer. J Sch Psychol. 2017;60:7–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jo B. Estimation of intervention effects with noncompliance: alternative model specifications. J Educ Behav Stat. 2002;27:385–409. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Holland PW. Statistics and causal inference. J Am Stat Assoc. 1986;81:945–960. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rubin DB. Causal inference using potential outcomes: design, modeling, decisions. J Am Stat Assoc. 2005;100:322–331. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jaki T, Kim M, Lamont A, et al. The effects of sample size on the estimation of regression mixture models. Educ Psychol Meas. 2019;79:358–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Van Horn M.L., Smith J, Fagan AA, et al. Not quite normal: consequences of violating the assumption of normality in regression mixture models. Struct Equ Model. 2012;19:227–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rubin D. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Murray DM. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Berkowitz RI, Marcus MD, Anderson BJ, et al. ; TODAY Study Group . Adherence to a lifestyle program for youth with type 2 diabetes and its association with treatment outcome in the TODAY clinical trial. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hatch SL, Dohrenwend BP. Distribution of traumatic and other stressful life events by race/ethnicity, gender, SES and age: a review of the research. Am J Community Psychol. 2007;40:313–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Gallo LC, de Los Monteros KE, Shivpuri S. Socioeconomic status and health: what is the role of reserve capacity? Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18:269–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Quattlebaum M, Kipp C, Wilson DK, et al. A qualitative study of stress and coping to inform the LEADS Health Promotion Trial for overweight African American adolescents. Nutrients. 2021;13:1–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Campbell-Voytal KD, Hartlieb KB, Cunningham PB, et al. African American adolescent-caregiver relationships in a weight loss trial. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27:835–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Davis AM, Daldalian MC, Mayfield CA, et al. Outcomes from an urban pediatric obesity program targeting minority youth: the Healthy Hawks program. Child Obes. 2013;9:492–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fagg J, Chadwick P, Cole TJ, et al. From trial to population: a study of a family-based community intervention for childhood overweight implemented at scale. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38:1343–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Joseph RP, Coe K, Ainsworth BE, Hooker SP, Mathis L, Keller C. Hair as a barrier to physical activity among African American women: a qualitative exploration. Front Public Health. 2017;5:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, et al. Systematic review of the relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:S197–S239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. St George SM, Wilson DK, Van Horn ML. Project SHINE: effects of a randomized family-based health promotion program on the physical activity of African American parents. J Behav Med. 2018;41:537–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Moore SC, Patel AV, Matthews CE, et al. Leisure time physical activity of moderate to vigorous intensity and mortality: a large pooled cohort analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9:e1001335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Burnet DL, Plaut AJ, Wolf SA, et al. Reach-out: a family-based diabetes prevention program for African American youth. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103:269–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Boutelle KN, Rhee KE, Liang J, et al. Effect of attendance of the child on body weight, energy intake, and physical activity in childhood obesity treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:622–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Neufeld ND. Outcome analysis of the B.E. S.T.R.O.N.G. childhood obesity treatment program: effectiveness of an eight-week family-based childhood obesity program using an Internet-based health tracker. Child Obes. 2016;12:227–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Knowlden AP, Sharma M, Cottrell RR, Wilson BR, Johnson ML. Impact evaluation of Enabling Mothers to Prevent Pediatric Obesity through Web-Based Education and Reciprocal Determinism (EMPOWER) randomized control trial. Health Educ Behav. 2015;42:171–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. St George SM, Van Horn ML, Lawman HG, Wilson DK. Reliability of 24-hour dietary recalls as a measure of diet in African-American youth. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116:1551–1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wilson DK, Sweeney AM, Quattlebaum M, Loncar H, Kipp C, Brown A. The moderating effects of the Families Improving Together (FIT) for weight loss intervention and parenting factors on family mealtime in overweight and obese African American adolescents. Nutrients. 2021;13:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wilson DK. Behavior matters: the relevance, impact, and reach of behavioral medicine. Ann Behav Med. 2015;49:40–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sweeney AM, Wilson DK, Loncar H, Brown A. Secondary benefits of the families improving together (FIT) for weight loss trial on cognitive and social factors in African American adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2019;16:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.