Abstract

In bacteria, double-strand DNA break (DSB) repair involves an exonuclease/helicase (exo/hel) and a short regulatory DNA sequence (Chi) that attenuates exonuclease activity and stimulates DNA repair. Despite their key role in cell survival, these DSB repair components show surprisingly little conservation. The best-studied exo/hel, RecBCD of Escherichia coli, is composed of three subunits. In contrast, RexAB of Lactococcus lactis and exo/hel enzymes of other low-guanine-plus-cytosine branch gram-positive bacteria contain two subunits. We report that RexAB functions via a novel mechanism compared to that of the RecBCD model. Two potential nuclease motifs are present in RexAB compared with a single nuclease in RecBCD. Site-specific mutagenesis of the RexA nuclease motif abolished all nuclease activity. In contrast, the RexB nuclease motif mutants displayed strongly reduced nuclease activity but maintained Chi recognition and had a Chi-stimulated hyperrecombination phenotype. The distinct phenotypes resulting from RexA or RexB nuclease inactivation lead us to suggest that each of the identified active nuclease sites in RexAB is involved in the degradation of one DNA strand. In RecBCD, the single RecB nuclease degrades both DNA strands and is presumably positioned by RecD. The presence of two nucleases would suggest that this RecD function is dispensable in RexAB.

In bacteria, double-stranded DNA breaks (DSB) are frequent events that may be provoked, for example, by pauses in the replication fork (36, 43). Such genomic disruptions are lethal in the absence of DNA repair. In Escherichia coli DSB repair requires the activity of a large enzyme complex, known as RecBCD, that has ATP-dependent helicase and exonuclease activities (see reference 32 for a review). The enzyme degrades both strands, starting from the DNA break until it reaches an octanucleotide sequence, known as Chi, that attenuates degradation and stimulates recombination (44, 46). The enzyme exhibits helicase activity and residual exonuclease activity with an altered polarity after Chi (4, 16); the remaining activity provides a single-stranded DNA substrate for recombination enzymes to mediate repair.

Organization of the three-subunit exonuclease/helicase (exo/hel) RecBCD.

Structure-functional studies of RecBCD have revealed some of the roles of each subunit. RecB seems to possess two key activities of the enzyme. The N-terminal 929 amino acids (out of 1,180 total) have confirmed ATPase and helicase activities (13, 54); this region is similar to that of UvrD helicase. RecBCD helicase activity was recently proposed to function via a mechanism similar to that determined for UvrD (6). Nuclease activity was recently localized to the C-terminal 251 amino acids of RecB and is associated with the presence of a conserved motif, G-i-i-D-x(12)-D-Y-K-t-d (amino acids in small letters show less conservation) (51, 53, 54). This motif is present in numerous bacterial and eukaryotic enzymes (5). RecBCD was shown to have a single nuclease catalytic center in RecB that works on both DNA strands (51). Little is known about the roles of RecC, except that it appears to greatly enhance activities and processivity of RecB (11, 38); mutations in the RecC gene can also result in loss or modification of Chi recognition, as do mutations in genes of all subunits (1). RecD is an ATPase with similarity to a helicase involved in conjugational transfer of an enteric bacterial plasmid; its homologues seem to be broadly distributed in bacteria (determined by BLAST comparisons; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). As part of RecBCD, RecD appears to regulate exonuclease activity. Recent data suggest that RecD maintains RecBCD incompetent for homologous recombination prior to Chi; at Chi, RecD is suggested to undergo a conformational change that attenuates exonuclease activity and stimulates recombination (2, 3, 12, 33, 48). A swing model was proposed in which RecD assures proximity of the RecB nuclease with both DNA strands prior to Chi and a repositioning of the nuclease after Chi (51, 54).

Organization of the two-subunit exo/hel enzymes.

To date, models of exo/hel activities are based on those of RecBCD. Numerous RecBCD homologues have been identified in gram-negative enterobacteria and in the high-guanine-plus-cytosine-content mycobacteria. However, the functional RecBCD analogue in the low-guanine-plus-cytosine-content branch of gram-positive bacteria is structurally distinct from RecBCD. Using Lactococcus lactis as a model, a two-subunit enzyme called RexAB (comprising 1,073- and 1,099-amino- acid subunits, respectively) is necessary and sufficient to confer exo/hel activity and interacts with the L. lactis Chi site (22). RexAB bears homologues in at least six other gram-positive low-guanine-plus-cytosine-content bacteria as well as in the gram-negative bacterium Porphyromonas gingivalis (determined by BLAST comparison; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). As studied in L. lactis or in Bacillus subtilis (AddAB), the two-subunit exo/hel enzymes display biological and/or biochemical activities equivalent to those of RecBCD (i.e., ATP-dependent exonuclease, helicase, exonuclease blocking at Chi, and Chi-stimulated recombination; 8, 9, 10, 22, 23, 28, 30, 31). RexA and its analogues in other gram-positive bacteria have homology with PcrA helicase (determined by BLAST comparison; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/), whose mechanism has been deduced from structural determinations (49). In addition, the nuclease motif described above for RecB is conserved in L. lactis RexA and in all known two-subunit exo/hel enzymes (5, 28, 53). This similarity has lead to the hypothesis that all exo/hel enzymes function via similar mechanisms.

However, several lines of evidence argue against a common mechanism of DSB repair. The exo/hel-Chi couples show remarkably little conservation from one bacterium to another. Furthermore, Chi sites are not the same in different species, and their genome distribution properties differ for each organism (7, 8, 10, 21, 45). This suggests that the Chi features of high frequency and overrepresentation on the genome had to arise independently in each case (7, 21). In addition, although the enzymes have equivalent biological functions, their structures are strikingly different. Similarities between two- and three-subunit enzymes are restricted to ATPase, helicase, and nuclease motifs present, for example, in RecB (of RecBCD) and RexA (of RexAB); no similarity is detected in the other exo/hel subunits. For comparison, RecA proteins of Escherichia coli and L. lactis are 56% identical (19). Recent in vitro studies with the two-subunit AddAB exo/hel may suggest that its activities differ from those of RecBCD (9). Unlike RecBCD, where a Chi encounter affects the degradation pattern of both strands, attenuation at Chi of AddAB-mediated degradation seems to affect only the Chi-containing strand (9, 16); however, exo/hel activities in vitro are very sensitive to assay conditions, which could explain these observations. The above considerations raise the possibility that the two- and three-subunit exo/hel enzymes are programmed differently to carry out their functions.

We examined the divergence between exo/hel enzymes of different microorganisms. Analyses of the L. lactis RexAB enzyme reveals the presence of two potential nuclease activities on the enzyme, one on each subunit. Each nuclease motif was modified by site-specific mutagenesis. The mutants show clear phenotypic differences in vivo, revealing that each nuclease motif has a key functional role in DNA degradation. Our results lead us to suggest that RexAB exo/hel has two distinct nuclease activities that may each degrade one double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) strand. Differences between the two- and three-subunit enzymes further suggest that the ubiquitous DSB repair strategy may undergo selective pressures that increase divergence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

The E. coli strains used were TG1 [F′ traD36 lacIq Δ(lacZ)M15 proA+B+/supE Δ(hsdM-mcrB)5(rK− mK− mcrB) thi Δ(lac-proAB)], AB1157 (argE3 his-4 leuB6 proA2 thr-1 ara-14 galK2 lacY1 mtl-1 xyl-5 thi-1 rpsL31 tsx-33 supE44), and KM21 (AB1157 isogenic strain containing [recC ptr recB recD]::kan, referred to here as ΔrecBCD) (37). The rexAB genes were derived from L. lactis strain MG1363 (25) and were cloned on low-copy-number plasmid pGB2 (confers spectinomycin resistance) to generate pRexAB (22).

Rolling circle (RC) plasmid pRC2 (confers chloramphenicol resistance) corresponds to a pVS41 derivative (50) equipped with a polylinker (5′-CTGGAATTCGTCGACGGATCC-3′) (EcoRI and BamHI sites are underlined) (22). Complementary primers 5′-AATTCACGCGCTGCAGGCGCGTGG-3′ and 3′-GTGCGCGACGTCCGCGCACCCTAG-5′ containing two L. lactis Chi (ChiLl) sites (one in each orientation on the primer, in italics) were cloned between the EcoRI and BamHI sites to give rise to pRC2-ChiLl (22).

Media.

E. coli strains were grown in Luria broth at 30 or 34°C, as specified below. Antibiotics were used in E. coli as follows: ampicillin at 100 μg/ml, spectinomycin at 50 μg/ml, tetracycline at 15 μg/ml, kanamycin at 40 μg/ml, and chloramphenicol at 15 μg/ml.

rexAB mutant constructions.

To generate mutants affected in the nuclease motifs of RexAB, fragment mutagenesis was performed using modified primers and pRexAB as template DNA. RexABD910A was constructed by replacing the SfcI-ClaI fragment that contains the 3′ end of rexB with a corresponding PCR fragment that was modified by a point mutation. The SfcI-end primer was 5′-CTTTCTACAGATTACTTAGGGGCGATTGCGTATA-3′ (the SfcI site is underlined; the GAC aspartate codon, RexB position 910, is replaced by the GCG alanine codon; changes are in bold). The ClaI-end primer was 5′-TCGACAAATCGATTTGAGAGGACAATATCGACA-3′ (the ClaI site is underlined). The resulting fragment was first subcloned onto an intermediate vector and then was cloned to replace the wild-type segment in pRexAB. The RexABΔDYK mutant was constructed essentially in the same way except that the SfcI-end primer was 5′-CCAACTTTCTACAGATTACTTAGGGGCGATT//TCAAGTGCTCATTCATT-3′ (the 9-codon deletion, RexB amino acid positions 910 to 912, is indicated by double slashes).

The RexAΔDYKB mutant was constructed by two-step mutagenesis using four primers. A rexAB PstI-EcoRI fragment can be generated using two outside primers: A, 5′-GAAGTTCAACCAGTCAGTGAGTTTGTTCG-3′ (the PstI site present in rexA is 46 nucleotides downstream of this primer), and B, 5′-GGGAATTCGGTACCATTGTTCTTCCTCCCTAACAGC-3′ (the PCR-amplified fragment contains an added EcoRI site [underlined] at the end of the rexA gene). To generate an internal DYK codon deletion, overlapping oligonucleotides that prime in opposite directions were designed: C, 5′-CACATTTGTAAATCTGTCCGT//AAATAATATAATCTTGTCAGC-3′ (the 9-codon RexA deletion, positions 1114 to 1116, is indicated by double slashes; this oligonucleotide generates a PCR fragment when coupled with primer A), and D, 5′-GACAAGATTATATTATTT//ACGGACAGATTTACAAATGTG-3′ (the 9-codon RexA deletion, positions 1114 to 1116, is indicated by double slashes; this oligonucleotide generates a PCR fragment when coupled with primer B). To generate a PstI-EcoRI fragment in which the DYK tricodon is missing, separate PCRs were first performed using primers A plus C and B plus D. The template was pRexAB. These fragments were purified, combined, and used as templates in a PCR containing oligonucleotides A plus B. The resulting band of the expected size was purified and cloned, and the PstI-EcoRI fragment was finally recloned into PstI-EcoRI-cut pRexAB. The resulting pRexAΔDYKB clone was confirmed by sequencing.

The plasmid pRexABΔ771–1063 was constructed by digesting pRexAB with ClaI-ScaI filling in and religation. This resulted in an in-frame deletion in rexB.

UV sensitivity tests for E. coli.

The E. coli ΔrecBCD strains containing mutated or wild-type rexAB alleles were maintained at 30°C. Note that exonuclease activity of RexAB is thermosensitive in E. coli, possibly reflecting an optimal growth temperature of L. lactis of 30°C. Tests to determine UV resistance were performed as described previously (18).

T4g2 test for exonuclease activity in E. coli.

The bacteriophage T4g2 amber mutant (kindly provided by W. Wackernagel, University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany) was used to evaluate exonuclease activity. The gene 2 product encodes a protein which protects phage DNA extremities from RecBCD degradation (34). The phage stock was prepared on a recBC strain not containing a supE mutation, so DNA ends of this phage mutant are exonuclease sensitive. Therefore, the number of PFU is low when this phage is titrated on strains expressing RecBCD. Lactococcal exonuclease activity expressed from pRexAB wild-type and mutated alleles was evaluated in the E. coli ΔrecBCD strain and compared to that of plasmid-free AB1157 (wild type) and E. coli ΔrecBCD strains essentially as described (52), except that cultures and plates were incubated at 30°C.

Detection of HMW.

High-molecular-weight linear plasmid multimer (HMW) accumulation was detected on whole-cell lysates after agarose gel electrophoresis (14). Plasmid DNA, labeled by chemiluminescence using the ECL system (Amersham), was used as a probe. Southern blot hybridization was performed as recommended by the kit supplier.

Recombination test.

We used a previously described strategy to measure Chi-stimulated homologous recombination using short dsDNA substrates (15). The plasmid target (named pΔBla) is a pBR322 derivative with a 111-bp deletion in the β-lactamase gene (bla). The intact bla gene is restored via a double-exchange event with a linear DNA fragment (see reference 22 for details of its construction). In brief, primers were designed to PCR amplify a bla gene internal fragment covering the DNA deleted from pΔBla plus an additional 360-bp flanking homology with bla. Primer couples generating double ChiLl sites or no Chi sites (ChiLl0) were as described previously (22). ChiLl sites are located about 300 bp from heterologous dsDNA ends. Linear DNA used for experiments was recovered by PCR using the primers 5′-GTTGGGAAGGGCGATCGGTG-3′ and 5′-CACTCATTAGGCACCCCAGGC-3′. The final fragment sizes were ∼1.3 kb.

Electrocompetent cells of the ΔrecBCD strain with or without plasmids encoding the different RexAB alleles plus pΔBla were prepared at 34°C, and control strain TG1 carrying pΔBla was prepared at 37°C. Cells were incubated at 34°C for 90 min after electrotransformation, and colony counts were determined after a 2-day incubation. Competence was determined by transforming cells with known amounts of pACYC184 DNA, selecting for chloramphenicol. Strains were transformed with about 200 ng of linear DNA as described previously (17). Linear DNA samples were quantitated on agarose gels using marker DNAs of known quantities. Electrotransformation into TG1 carrying pΔBla was used to evaluate DNA quality. It was previously shown that electroporation totally inactivates wild-type E. coli RecBCD exonuclease but allows E. coli Chi-independent recombination (20); the recombination capacity of the two fragments (regardless of ChiLl) was compared in this way. Although the reason why electroporation inactivates RecBCD exonuclease is unknown, it is possible that the electric shock induces the SOS response, which is known to diminish exonuclease activity and retain recombination proficiency (41). Both fragments were found to transform this strain with about equal efficiencies (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Recombination efficiency in the presence of RexAB nuclease mutants

| pRexAB derivatives in E. coli ΔrecBCD (pΔBla) | Transformation efficiency with pACYC184 (1 μg) | No. of ampicillin-resistant transformants with:a

|

ChiLl stimulationb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ChiLl0c | ChiLlc | |||

| pRexAB | 2 × 106 | 10 | 199 | 30 |

| pRexABD910A | 2 × 106 | 482 | 3,012 | 10 |

| pRexABΔDYK | 1 × 106 | 130 | 309 | 4 |

| pRexABΔ771–1063 | 8 × 105 | 63 | 112 | 3 |

| pRexAΔDYKB | 5 × 106 | 8 | 6 | 1 |

| pGB2d | 2 × 106 | 30 | 19 | 1 |

| TG1 control | 1.5 × 107 | 416 | 272 | 1 |

Values represent the total number of transformants obtained in three transformation experiments. For each experiment 200 ng of the appropriate linear DNA was used.

ChiL stimulation was determined as the ratio of ampicillin-resistant transformants obtained with linear DNA fragments containing ChiLl compared to those with no ChiLl (designated ChiLl0). To determine the capacity of each fragment to effect homologous recombination, we used conditions of TG1 electroporation that abolish nuclease activity; the ratio obtained in TG1 was used to correct for Chi activity ratios in the test strains (20) (see Materials and Methods).

ChiLl and ChiLl0 correspond to the linear fragments used for gene conversion, which do and do not, respectively, contain the double ChiLl sites flanking the region of bla homology.

pGB2 was the vector used to clone rexAB genes.

Colony counts were performed after 48 h of incubation. The numbers of Amp-resistant transformants obtained with ChiLl- or ChiLl0-containing linear DNAs were compared for each strain. Linear DNA samples were quantitated on agarose gels using marker DNAs of known quantities. Electrocompetent E. coli ΔrecBCD containing pΔBla was used as a negative recipient control.

RESULTS

Conserved regions of two- versus three-subunit exo/hel enzymes.

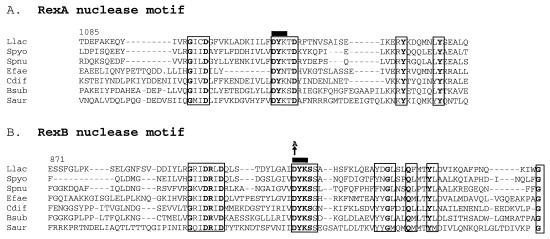

Alignments of several two-subunit exo/hel enzymes reveal that these enzymes are poorly homologous, even in closely related species. They bear very little homology with the three-subunit exo/hel. Nevertheless, a short nuclease motif was previously revealed in the AddA subunit of the B. subtilis AddAB enzyme and in the RecB subunit of RecBCD (28, 53). In RecBCD, this motif corresponds to the sole nuclease activity of the exo/hel enzymes (51). We found that this motif is actually present in both subunits of the two-subunit enzymes (Fig. 1). In the RexA subunit, a consensus is G-i-i-D-x(12)-D-Y-K-t-d (amino acids in small letters show some variation); in RexB it is G-r-i-D-R-i-D-x(9–12)-v-D-Y-K-S-s. The striking similarities between these motifs lead us to ask whether RexAB may bear two active nuclease sites, one in each subunit.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of nuclease motifs present in each subunit of the two-subunit exo/hel enzymes. (A) RexA subunit homologue alignments are presented for the region surrounding the nuclease motif (corresponding to positions 1085 to 1164 of the 1,173-amino acid L. lactis RexA subunit). (B) RexB subunit homologies in the region surrounding the nuclease motif (corresponding to positions 871 to 949 of the 1,099-amino acid L. lactis RexB subunit). Highly conserved motifs are enclosed in a rectangle, and amino acids that are totally conserved are in bold. The black bar over amino acids DYK corresponds to the region deleted in lactococcal RexA or RexB mutants; the arrow over position 910 in RexB indicates a point substitution from aspartic acid to alanine generated in RexB (see the text). Llac, L. lactis; Spyo, Streptococcus pyogenes; Spnu, Streptococcus pneumoniae; Efae, Enterococcus faecalis; Cdif, Clostridium difficile; Bsub, B. subtilis; Saur, Staphylococcus aureus.

Site-specific mutagenesis of putative nuclease motifs in RexA and RexB.

The rexAB operon (rexB is followed by rexA) was previously cloned on a low-copy-number plasmid and shown to fulfill the biological roles of RecBCD in an E. coli ΔrecBCD strain (22). The putative RexA nuclease motif (RexANuc) was modified by a 3-amino-acid deletion removing the tripeptide DYK in positions 1114 to 1116 (called RexAΔDYKB) (Fig. 1). The putative RexB nuclease motif (RexBNuc) was modified by alteration of D910 to A (called RexABD910A) or by a 3-amino-acid deletion, removing the tripeptide DYK in positions 910 to 912 (called RexABΔDYK) (Fig. 1). In addition, a 293-amino-acid in-frame deletion of RexB that removed C-terminal amino acids 771 to 1063 (called RexABΔ771–1063) was constructed. The cloned rexAB mutated genes gave rise to pRex plasmids bearing the name of the mutation and were established in an E. coli ΔrecBCD strain (37).

UV resistance conferred by the different pRexAB mutants was examined (Table 1). The ΔrecBCD strain shows greater UV resistance in the presence of pRexAB (22) or pRexABD910A. However, UV resistance of the ΔrecBCD strain was not at all or was only very slightly improved in the presence of pRexAΔDYKB, pRexABΔ771–1063, or pRexABΔDYK compared to that of the control strains. These results indicate that the introduced mutations affect the DNA repair capacity of RexAB exo/hel.

TABLE 1.

Capacity of RexAB nuclease mutants to complement a ΔrecBCD strain

| E. coli strain (plasmid) | Relative survival after UV irradiationa | Relative PFU of T4g2b |

|---|---|---|

| recBCD (pRexAB) | 1 | 0.000062 |

| recBCD (pRexABD910A) | 0.4 | 0.0014 |

| recBCD (pRexABΔDYK) | 0.09 | 0.015 |

| recBCD (pRexABΔ771–1063) | 0.05 | 0.17 |

| recBCD (pRexAΔDYKB) | 0.01 | 0.2 |

| recBCD (pGB2)c | 0.01 | 1 |

Cells were irradiated at 100 J/m2. Note that survival of the wild-type strain (AB1157) was 4 × 10−1, while that of recBCD (pRexAB) was 3 × 10−2. Results are means of two experiments.

The values given are relative to a plaque titer of ∼4 × 1010 PFU/ml on the ΔrecBCD strain; AB1157 gave a relative plaque titer of 0.0001. Results are means of at least three experiments.

pGB2 is the vector used to clone rexAB genes. For both experiments, determination values were within twofold of presented values.

Changes in RexA or RexB nuclease motifs affect RexAB exonuclease activities.

Phage T4g2 is susceptible to exo/hel degradation. As nuclease activity inhibits plaque-forming ability, plaque formation would reflect diminished nuclease activity in the rexAB mutants (Table 1). The recBCD mutant containing pRexAB efficiently inhibits phage multiplication, whereas this strain lacking rexAB genes is totally permissive (22). The strain containing pRexAΔDYKB allowed efficient phage multiplication. Thus, inactivation of the nuclease motif of RexA essentially abolishes all DNA degradation activity by RexAB.

For strains containing pRexABD910A and pRexABΔDYK, T4g2 infectivity was increased 10- and 100-fold, respectively (Table 2), indicating that nuclease activity is significantly reduced in these strains. Note that nuclease inactivation may even be underestimated in this assay, as unwinding activity alone may have a modest inhibitory effect on T4g2 multiplication (40). This result shows that the RexB nuclease motif DYK is a functionally active component of the exo/hel enzyme. The strain containing pRexABΔ771–1063 is totally permissive for phage multiplication, indicating that a large deletion in RexB abolishes in vivo nuclease activity.

These data show unambiguously that both the DYK motif in RexB (positions 910 to 912) as well as that in RexA (positions 1114 to 1116) are involved in nuclease activities of RexAB. Thus, the RexAB enzyme appears to differ from RecBCD, in which a single nuclease locus is involved.

RexBNuc mutants recognize Chi.

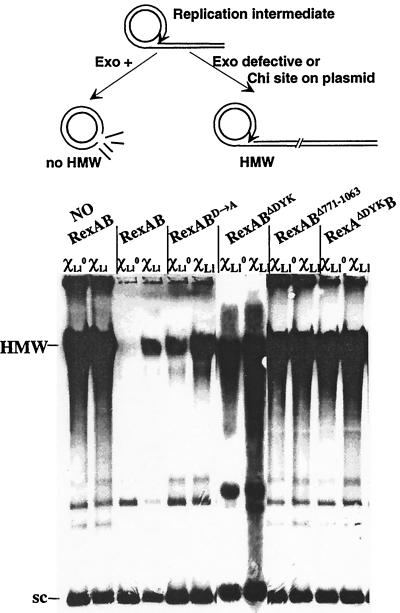

We previously developed an in vivo test to detect Chi attenuation of exo/hel exonuclease activity by using an RC plasmid as substrate. A ς-formed replication intermediate of RC plasmids provides a dsDNA end as an entry point for exo/hel enzyme. If the RC plasmid contains a Chi site in the orientation recognized by exo/hel, degradation is attenuated and ς-form replication results in accumulation of HMW (14, 26). In the absence of Chi on the plasmid, HMW do not accumulate as long as exo/hel is active. However, if exo/hel is nuclease defective, any RC plasmid will accumulate HMW (e.g., RC plasmids accumulate large amounts of HMW in an E. coli recD mutant; our unpublished data).

We examined the activity of rexAB mutants in the E. coli ΔrecBCD background on RC plasmids with or without an L. lactis Chi site (called ChiLl) (Fig. 2). In the presence of pRexAB, HMW accumulation was observed only if ChiLl was present on the RC plasmid. In the absence of any exo/hel enzyme, HMW accumulated regardless of the presence of ChiLl on the plasmid (Fig. 2) (22). The strain containing pRexAΔDYKB behaved like the exo/hel-deficient strain. These results are consistent with the nuclease-negative phenotype conferred by RexAΔDYKB in the phage infection test. Other mutated rexA alleles in which the nuclease motif was deleted gave rise to similar phenotypes (L. Rezaïki and A. Gruss, unpublished observations). We also observed ChiLl-independent HMW accumulation in the strain expressing RexABΔ771–1063, confirming that nuclease activity is deficient in this enzyme.

FIG. 2.

HMW accumulation in the presence of wild-type or mutant RexA or RexB subunits. The upper portion shows the schema of HMW accumulation. RC plasmid replication may result in formation of a ς-shaped intermediate with a dsDNA tail. This tail is susceptible to exonuclease (Exo) degradation, and a monomeric circle is restored (left). If the strain is exonuclease defective, or if Chi is present on the RC plasmid, the ς form is extended and HMW accumulates (right). The bottom portion shows E. coli ΔrecBCD derivatives containing plasmid pRC2 with ChiLl (marked χLl) or without (marked χLl0) as well as a plasmid that carries a rexAB allele or no rexAB, as indicated above the wells. Cells were grown to mid-logarithmic phase at 34°C, and whole-cell lysates were prepared. HMW were detected by Southern hybridization using a pRC2 DNA fragment as the probe. Positions of HMW and supercoiled monomer plasmid (sc) migration are indicated. Note that results shown for RexABΔDYK are from a separate gel.

The two rexBNuc mutants exhibit a markedly different phenotype (Fig. 2). As expected for a nuclease-defective enzyme, the presence of pRexABD910A resulted in more HMW than did pRexAB. However, HMW accumulation remained ChiLl dependent. Greater amounts of HMW were also observed when pRexABΔDYK was present; a modest effect of ChiLl in increasing accumulation was still observed. These results are consistent with our hypothesis that the RexBNuc motif is necessary for nuclease activity of the enzyme. In addition, the ChiLl-dependent increase in HMW accumulation shows that the remaining nuclease activity is still attenuated at ChiLl. Possibly, the RexB subunit degrades just one of the two dsDNA strands from the 5′ end (i.e., the strand containing the Chi complement) (23).

These results confirm the nuclease-defective phenotype of RexBNuc as seen in the T4g2 test. They further show that although RexBNuc nuclease activity is reduced, its ChiLl recognition is maintained. In contrast, the RexANuc nuclease change abolishes all nuclease activity, regardless of ChiLl. Thus, the phenotypes of the RexA and RexB nuclease changes are clearly distinguishable in vivo.

RexBNuc but not RexANuc mutants display a Chi-stimulated hyperrecombination phenotype.

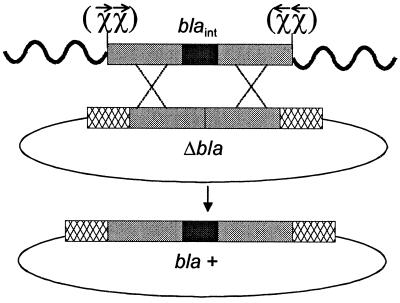

Gene replacement with linear DNA fragments is stimulated if correctly oriented Chi sites are present in the linear DNA flanking regions of homologies (15, 22, 23). Using this criterion, it was previously demonstrated that the presence of ChiLl stimulates homologous recombination (22, 23). We examined the ability of mutant RexAB exo/hel to mediate ChiLl-stimulated homologous recombination by using linear fragments with or without double ChiLl sites at the ends (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The E. coli ΔrecBCD recipient contained the recombination target plasmid (pΔBla) together with a plasmid encoding a mutated rexAB allele. As expected, very few recombinants were obtained in the ΔrecBCD host, regardless of whether ChiLl were present on the linear dsDNA ends. Recombination via wild-type RexAB was stimulated 30-fold by the presence of Chi on incoming linear fragments, in keeping with previous results (22, 23). In the presence of pRexAΔDYKB, recombination was at background levels, further confirming that a change in the RexA nuclease motif results in total inactivation of RexAB biological activities in vivo.

FIG. 3.

Strategy to test ChiLl effect on RexAB mutant-mediated homologous recombination. The recombination target plasmid pΔBla bears an internal deletion of bla (Δbla). Linear transforming DNA contains an internal fragment of bla which spans the bla deletion (black rectangle) plus an additional 360 bp of flanking homology (dark grey rectangle) with pΔBla (called blaint). Where present, double ChiLl sites on the linear fragments are oriented for recognition to enhance recombination and are represented by χχ (RexAB recognizes the arrow tail). Wavy lines represent heterologous dsDNA tails. Double-crossover homologous recombination is required to convert cells to being ampicillin resistant (bla+). Hatched rectangles represent bla DNA outside the regions present on linear DNA. The figure is essentially the same as one published in reference 22, with permission from the National Academy of Sciences.

RexBNuc nuclease mutants displayed a totally distinct hyperrecombination phenotype. Significant stimulation of homologous recombination as well as a ChiLl effect were observed. The greatest stimulation was seen in the presence of pRexABD910A; a hyperrecombination phenotype was observed for the ChiLl0 fragment as well as a further 10-fold stimulation by ChiLl. Chi-stimulated, elevated homologous recombination frequencies were also observed in the strain containing pRexABΔDYK. Thus, RexBNuc mutants have a stimulatory effect on recombination using short DNA fragments as substrates, and they also retain Chi recognition.

The strain containing pRexABΔ771–1063 demonstrated recombination frequencies like those of pRexAB, except that ChiLl0 fragment frequencies were elevated; nevertheless, an approximately threefold Chi stimulation effect was observed. These results suggest that the pRexABΔ771–1063 enzyme retains some ChiLl recognition activity despite a large C-terminal RexB deletion.

Taken together, these results show that RexA and RexB subunits both contribute to the observed nuclease activity of RexAB. The RexAΔDYK mutant abolishes all detectable in vivo activity of the enzyme, including homologous recombination. The RexABD910A and RexBΔDYK mutants reduce exonuclease activity but retain ChiLl recognition and display a ChiLl-stimulated hyperrecombination phenotype when using short dsDNA fragments as substrates.

DISCUSSION

RexAB exo/hel enzyme function involves two active nuclease sites.

The E. coli RecBCD-Chi couple has served as the prototype for bacterial DSB repair. Indeed, exo/hel-Chi couples identified in other bacteria were confirmed to fulfill the biological or biochemical functions established in E. coli (9, 22, 42, 52). However, RecBCD and the L. lactis exo/hel enzyme, RexAB, differ operationally: RecBCD relies on a single nuclease to effect DNA degradation (51, 53). In contrast, we have shown that RexAB contains two nuclease motifs, one in each subunit, both of which are required for full nuclease activity. Inactivation of the RexA nuclease motif results in total loss of exo/hel functions in vivo, whereas inactivation of the RexB nuclease motif reduces degradation while retaining Chi activity. As these two nuclease motifs are present in all identified (or predicted) two-subunit exo/hel enzymes, we predict that these enzymes will have properties similar to those described here.

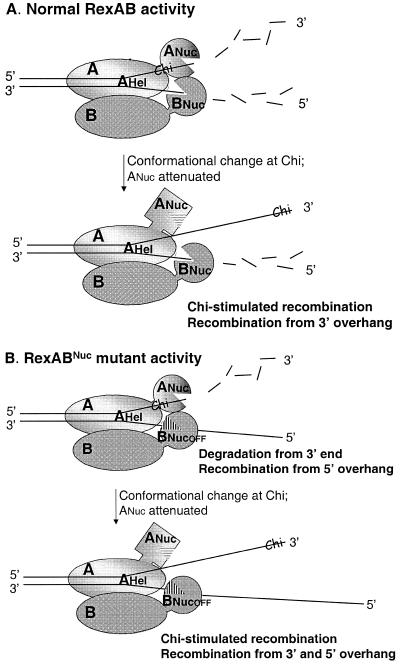

We propose a model for RexAB activity based on our in vivo results (Fig. 4A). The two major features of the model are the following. (i) RexA, like RecB, has helicase and nuclease activities and drives the enzyme. Unwinding of the double helix is assured by RexA, which has significant homology with PcrA helicases. The RexB subunit could enhance activities of RexA helicase, just as RecC appears to increase RecB processivity and activities (11, 38). (ii) The RexA nuclease cleaves just one strand, from the 3′ end, while the RexB nuclease is positioned to degrade from a 5′ end. This model is consistent with our results showing that RexBNuc mutants degrade DNA but maintain Chi recognition and with recent in vitro studies reported for AddAB in which degradation is attenuated at Chi but only on the Chi-containing strand; degradation of the “bottom” strand continues after Chi (9). This model may be useful in understanding the absence of a third, RecD-like component in the two-subunit exo/hel enzymes. RecD is proposed to position the single nuclease of the RecBCD enzyme so that it degrades the two DNA strands (51); if, as proposed, the nucleases of RexAB each act on a DNA strand, this RecD function would not be needed. Alternatively, the two established nuclease motifs are both needed to degrade each strand. We consider this possibility unlikely, as our results show that the RexA nuclease is active even if RexBNuc is mutated. In vitro analyses will confirm whether this model is valid.

FIG. 4.

Model for RexAB activity. (A) Normal RexAB. RexAB advances from an end on its dsDNA linear substrate via the RexA-driven helicase. RexB is proposed here to increase processivity, as does RecC of RecBCD (38). The RexA nuclease motif degrades from the 3′ end until the exo/hel enzyme reaches a Chi site. The conformational change at Chi attenuates RexA nuclease activity and thereby stimulates homologous recombination. The RexB nuclease degrades the dsDNA substrate from the 5′ end (bottom strand). At ChiLl, degradation is essentially unchanged or possibly enhanced, as reported, in vitro for the bottom strand after RecBCD encounters an E. coli Chi site (3). (B) Mutant affected in the RexB nuclease motif. Activities are as in panel A, except that the RexB nuclease is inactive. As such, although the 3′ end is degraded by RexA nuclease, a 5′ end is generated that can act as a substrate in homologous recombination, as shown from previous in vitro and in vivo data (35, 39). This can explain elevated levels of recombination in the assay using linear DNA fragments lacking ChiLl (Table 2). Upon a ChiLl encounter, RexA nuclease is attenuated, thus making both DNA strands accessible for recombination. A and B refer to RexA and RexB subunits, respectively. ANuc and BNuc correspond to the nuclease domains surrounding the motifs presented in Fig. 1. An open mouth has an active nuclease, while a barred mouth represents an inactive nuclease. AHel corresponds to the RexA helicase domain (deduced from BLAST homologies with PcrA helicase).

The above model can explain simply the behavior of the RexBNuc mutants (Fig. 4B). As mentioned above, we propose that RexA drives the enzyme. Our data suggest that inactivation of the RexB nuclease motif does not abolish other enzyme functions. As such, DNA strands would be unwound and the 3′ end degraded by RexA nuclease. The protruding 5′ end could act as a substrate for homologous recombination, as suggested by previous in vitro and in vivo data (35, 39), consistent with the hyperrecombination phenotype seen for the RexBNuc mutants in the absence of ChiLl stimulation (Table 2). Upon ChiLl encounter, degradation from the 3′ end is inhibited and both strands are available for recombination.

In contrast to RexBNuc mutants, the RexAΔDYKB mutant exhibited no in vivo biological activity and may thus correspond to a null mutant. Interestingly, in B. subtilis and in E. coli, mutations affecting nuclease motifs in RexA analogues AddA and RecB, respectively, retain helicase activities. For example, an AddAB mutant in which the C-terminal end of AddA is deleted lacks nuclease activity but retains some helicase proficiency in vivo and in vitro (28), and an E. coli RecBD1080ACD gene mutation inactivates the RecB nuclease (53); in vivo, this enzyme is nonfunctional (2). It was reasoned that RecBD1080ACD is unable to undergo a conformational change at Chi and thus remains locked in the “antirecombinase” position; this effect is alleviated by removing RecD (2, 12). Our preliminary results suggest that recombination is restored in a RexAΔDYK RexBΔDYK double mutant (data not shown), suggesting that the conformational change observed at ChiLl might involve interactions between RexB and RexA nuclease domains. Applying the above reasoning, we speculate that RexAΔDYKB could be locked in a nonrecombinogenic state that blocks the conformational change at ChiLl needed to render it recombinogenic. The alternative hypotheses concerning the RexANuc mutant will be examined by further genetic and biochemical tests.

Why is exo/hel so poorly conserved?

The primordial need for an intact genome suggests that DNA genome repair mechanisms have been present early in evolution. Accordingly, generalized homologous recombination proteins such as RecA, SSB, and RecF are rather highly conserved (19) (comparisons analyzed using BLAST; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/).

It is surprising that components of an important survival function like DNA repair are so markedly divergent. The diversity in DSB repair enzymes may be related to genome plasticity: genome rearrangements are common events that may occur via intrachromosomal transposition, gene duplications and inversions, or entry of exogenous DNA. In L. lactis, there is a 4:1 orientation bias of Chi distribution with respect to the direction of DNA replication (exo/hel recognizes Chi in one orientation) (14,21,23,29,47). Inversion of a large DNA segment could considerably reduce the number of Chi sites available to stimulate repair if a replication fork break occurs in that region (36). Such rearrangements could impose selective pressure for exo/hel divergence. The constant need for the exo/hel enzyme to adapt to altered distributions of Chi on the genome (e.g., due to chromosomal inversions or mutations) could explain why these enzymes are so divergent, even in closely related species.

Is E. coli the right DSB repair model? The E. coli RecBCD exo/hel enzyme has been the paradigm for DSB repair over the last 30 years. But E. coli is a relatively young bacterium in terms of evolution; it seems to have evolved well after oxygen became abundant (27). In contrast, L. lactis, which thrives under low- or no-oxygen conditions, appears to have preceded E. coli evolutionarily (24, 27). To follow the evolution of the DSB repair system, we suggest that comparison with an older microorganism like L. lactis will be informative and may reveal minimum requirements for DSB repair.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate discussions in the course of this work with Susan Amundsen, Yakyha Dieye, Bénédicte Michel, Yves Le Loir, Philippe Langella, and our laboratory colleagues and we thank anonymous reviewers for comments.

This work was supported by a grant from the Programme de recherche fondamentale en microbiologie et maladies infectieuses et parasitaires of the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie, France. A.Q. was the recipient of a postdoctoral fellowship awarded by the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientificas y Tecnicas, Argentina.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amundsen S K, Neiman A M, Thibodeaux S M, Smith G R. Genetic dissection of the biochemical activities of RecBCD enzyme. Genetics. 1990;126:25–40. doi: 10.1093/genetics/126.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amundsen S K, Taylor A, Smith G R. The RecD subunit of the Escherichia coli RecBCD enzyme inhibits RecA loading, homologous recombination and DNA repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:7399–7404. doi: 10.1073/pnas.130192397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson D G, Churchill J J, Kowalczykowski S C. A single mutation, RecBD1080A, eliminates RecA protein loading but not Chi recognition by RecBCD enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:27139–27144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.27139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson D G, Kowalczykowski S C. The recombination hot spot chi is a regulatory element that switches the polarity of DNA degradation by the RecBCD enzyme. Genes Dev. 1997;11:571–581. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aravind L, Walker D R, Koonin E V. Conserved domains in DNA repair proteins and evolution of repair systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1223–1242. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.5.1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianco P R, Kowalczykowski S C. Translocation step size and mechanism of the RecBC DNA helicase. Nature. 2000;405:368–372. doi: 10.1038/35012652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biaudet V, El Karoui M, Gruss A. Codon usage can explain GT-rich islands surrounding Chi sites on the Escherichia coli genome. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:666–669. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswas I, Maguin E, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. A 7-base-pair sequence protects DNA from exonucleolytic degradation in Lactococcus lactis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2244–2248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chedin F, Ehrlich S D, Kowalczykowski S C. The Bacillus subtilis AddAB helicase/nuclease is regulated by its cognate Chi sequence in vitro. J Mol Biol. 2000;298:7–20. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chedin F, Noirot P, Biaudet V, Ehrlich S D. A five-nucleotide sequence protects DNA from exonucleolytic degradation by AddAB, the RecBCD analogue of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:1369–1377. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen H W, Randle D E, Gabbidon M, Julin D A. Functions of the ATP hydrolysis subunits (RecB and RecD) in the nuclease reactions catalyzed by the RecBCD enzyme from Escherichia coli. J Mol Biol. 1998;278:89–104. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Churchill J J, Anderson D G, Kowalczykowski S C. The RecBC enzyme loads RecA protein onto ssDNA asymmetrically and independently of chi, resulting in constitutive recombination activation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:901–911. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churchill J J, Kowalczykowski S C. Identification of the RecA protein-loading domain of RecBCD enzyme. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:537–542. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dabert P, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. Chi sequence protects against RecBCD degradation of DNA in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:12073–12081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.24.12073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dabert P, Smith G R. Gene replacement with linear DNA fragments in wild-type Escherichia coli: enhancement by Chi sites. Genetics. 1997;145:877–889. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon D A, Kowalczykowski S C. Role of the Escherichia coli recombination hotspot, χ, in RecABCD-dependent homologous pairing. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:16360–16370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.27.16360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dower W J, Miller J F, Ragsdale C W. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:6127–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duwat P, Cochu A, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. Characterization of Lactococcus lactis UV-sensitive mutants obtained by ISS1 transposition. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4473–4479. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.14.4473-4479.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Duwat P, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. Use of degenerate primers for polymerase chain reaction cloning and sequencing of the Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis recA gene. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2674–2678. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2674-2678.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Karoui M, Amundsen S K, Dabert P, Gruss A. Gene replacement with linear DNA in electroporated wild-type Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1296–1299. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.5.1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.El Karoui M, Biaudet V, Schbath S, Gruss A. Characteristics of Chi distribution on different bacterial genomes. Res Microbiol. 1999;150:579–587. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(99)00132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.El Karoui M, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. Identification of the lactococcal exonuclease/recombinase and its modulation by the putative Chi sequence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:626–631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Karoui M, Schaeffer M, Biaudet V, Bolotin A, Sorokin A, Gruss A. Orientation specificity of the Lactococcus lactis Chi site. Genes Cells. 2000;5:453–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2000.00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox G E, Stackebrandt E, Hespell R B, Gibson J, Maniloff J, Dyer T A, Wolfe R S, Balch W E, Tanner R, Magrum L, Zablen L B, Blakemore R, Gupta R, Bonen L, Lewis B J, Stahl D A, Luehrsen K R, Chen K N, Woese C R. The phylogeny of prokaryotes. Science. 1980;209:457–463. doi: 10.1126/science.6771870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasson M J. Plasmid complements of Streptococcus lactis NCDO 712 and other lactic streptococci after protoplast-induced curing. J Bacteriol. 1983;154:1–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.154.1.1-9.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruss A, Ehrlich S D. Insertion of foreign DNA into plasmids from gram-positive bacteria induces formation of high-molecular-weight plasmid multimers. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1183–1190. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1183-1190.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta R S. Protein phylogenies and signature sequences: a reappraisal of evolutionary relationships among archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1435–1491. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1435-1491.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haijema B J, Venema G, Kooistra J. The C terminus of the AddA subunit of the Bacillus subtilis ATP-dependent DNase is required for the ATP-dependent exonuclease activity but not for the helicase activity. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5086–5091. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.17.5086-5091.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi I, Murialdo H, Crasemann J M, Stahl M M, Stahl F W. Orientation of cohesive end site cos determines the active orientation of chi sequence in stimulating RecA. RecBC-mediated recombination in phage lambda lytic infections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5981–5985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.5981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kooistra J, Haijema B J, Hesseling-Meinders A, Venema G. A conserved helicase motif of the AddA subunit of the Bacillus subtilis ATP-dependent nuclease (AddAB) is essential for DNA repair and recombination. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:137–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.1991570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kooistra J, Haijema B J, Venema G. The Bacillus subtilis addAB genes are fully functional in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:915–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01182.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kowalczykowski S C, Dixon D A, Eggleston A K, Lauder S D, Rehrauer W M. Biochemistry of homologous recombination in Escherichia coli. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:401–465. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.3.401-465.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuzminov A. Recombinational repair of DNA damage in Escherichia coli and bacteriophage lambda. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:751–813. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.4.751-813.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lipinska B, Rao A S, Bolten B M, Balakrishnan R, Goldberg E B. Cloning and identification of bacteriophage T4 gene 2 product gp2 and action of gp2 on infecting DNA in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:488–497. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.488-497.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mazin A V, Zaitseva E, Sung P, Kowalczykowski S C. Tailed duplex DNA is the preferred substrate for Rad51 protein-mediated homologous pairing. EMBO J. 2000;19:1148–1156. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michel B, Ehrlich S D, Uzest M. DNA double-strand breaks caused by replication arrest. EMBO J. 1997;16:430–438. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy K C. Use of bacteriophage recombination functions to promote gene replacement in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2063–2071. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2063-2071.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phillips R J, Hickleton D C, Boehmer P E, Emmerson P T. The RecB protein of Escherichia coli translocates along single-stranded DNA in the 3′ to 5′ direction: a proposed ratchet mechanism. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:319–329. doi: 10.1007/pl00008605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Razavy H, Szigety S K, Rosenberg S M. Evidence for both 3′ and 5′ single-strand DNA ends in intermediates in chi-stimulated recombination in vivo. Genetics. 1996;142:333–339. doi: 10.1093/genetics/142.2.333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rinken R, Thomas B, Wackernagel W. Evidence that recBC-dependent degradation of duplex DNA in Escherichia coli recD mutants involves DNA unwinding. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5424–5429. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5424-5429.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rinken R, Wackernagel W. Inhibition of the recBCD-dependent activation of Chi recombinational hot spots in SOS-induced cells of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1172–1178. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1172-1178.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schultz D W, Smith G R. Conservation of Chi cutting activity in terrestrial and marine enteric bacteria. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:585–595. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90489-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Seigneur M, Bidnenko V, Ehrlich S D, Michel B. RuvAB acts at arrested replication forks. Cell. 1998;95:419–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith G R, Kunes S M, Schultz D W, Taylor A, Triman K L. Structure of chi hotspots of generalized recombination. Cell. 1981;24:429–436. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sourice S, Biaudet V, El Karoui M, Ehrlich S D, Gruss A. Identification of the Chi site of Haemophilus influenzae as several sequences related to the Escherichia coli Chi site. Mol Microbiol. 1998;27:1021–1029. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stahl F W, Crasemann J M, Stahl M M. Rec-mediated recombinational hot spot activity in bacteriophage lambda. III. Chi mutations are site-mutations stimulating rec-mediated recombination. J Mol Biol. 1975;94:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(75)90078-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taylor A F, Schultz D W, Ponticelli A S, Smith G R. RecBC enzyme nicking at Chi sites during DNA unwinding: location and orientation-dependence of the cutting. Cell. 1985;41:153–163. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thaler D S, Sampson E, Siddiqi I, Rosenberg S M, Thomason L C, Stahl F W, Stahl M M. A hypothesis: Chi-activation of RecBCD enzyme involves removal of the RecD subunit. In: Friedberg E, Hanawalt P, editors. Mechanisms and consequences of DNA damage processing. New York, N.Y: Liss; 1988. pp. 413–422. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Velankar S S, Soultanas P, Dillingham M S, Subramanya H S, Wigley D B. Crystal structures of complexes of PcrA DNA helicase with a DNA substrate indicate an inchworm mechanism. Cell. 1999;97:75–84. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80716-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.von Wright A, Saarela M. A variant of the staphylococcal chloramphenicol resistance. Plasmid. 1994;31:106–110. doi: 10.1006/plas.1994.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang J, Chen R, Julin D A. A single nuclease active site of the Escherichia coli RecBCD enzyme catalyzes single-stranded DNA degradation in both directions. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:507–513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weichenhan D, Wackernagel W. Functional analyses of Proteus mirabilis wild-type and mutant RecBCD enzymes in Escherichia coli reveal a new mutant phenotype. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:1777–1784. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu M, Souaya J, Julin D A. Identification of the nuclease active site in the multifunctional RecBCD enzyme by creation of a chimeric enzyme. J Mol Biol. 1998;283:797–808. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu M, Souaya J, Julin D A. The 30-kDa C-terminal domain of the RecB protein is critical for the nuclease activity, but not the helicase activity, of the RecBCD enzyme from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:981–986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]