Keywords: computational fluid dynamics, neonates, tracheomalacia, ultrashort echo time magnetic resonance imaging, work of breathing

Abstract

Tracheomalacia is an airway condition in which the trachea excessively collapses during breathing. Neonates diagnosed with tracheomalacia require more energy to breathe, and the effect of tracheomalacia can be quantified by assessing flow-resistive work of breathing (WOB) in the trachea using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling of the airway. However, CFD simulations are computationally expensive; the ability to instead predict WOB based on more straightforward measures would provide a clinically useful estimate of tracheal disease severity. The objective of this study is to quantify the WOB in the trachea using CFD and identify simple airway and/or clinical parameters that directly relate to WOB. This study included 30 neonatal intensive care unit subjects (15 with tracheomalacia and 15 without tracheomalacia). All subjects were imaged using ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI. CFD simulations were performed using patient-specific data obtained from MRI (airway anatomy, dynamic motion, and airflow rates) to calculate the WOB in the trachea. Several airway and clinical measurements were obtained and compared with the tracheal resistive WOB. The maximum percent change in the tracheal cross-sectional area (ρ = 0.560, P = 0.001), average glottis cross-sectional area (ρ = −0.488, P = 0.006), minute ventilation (ρ = 0.613, P < 0.001), and lung tidal volume (ρ = 0.599, P < 0.001) had significant correlations with WOB. A multivariable regression model with three independent variables (minute ventilation, average glottis cross-sectional area, and minimum of the eccentricity index of the trachea) can be used to estimate WOB more accurately (R2 = 0.726). This statistical model may allow clinicians to estimate tracheal resistive WOB based on airway images and clinical data.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY The work of breathing due to resistance in the trachea is an important metric for quantifying the effect of tracheal abnormalities such as tracheomalacia, but currently requires complex dynamic imaging and computational fluid dynamics simulation to calculate it. This study produces a method to predict the tracheal work of breathing based on readily available imaging and clinical metrics.

INTRODUCTION

Newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) due to prematurity or congenital respiratory abnormalities may have breathing difficulties as a result of dynamic collapse of the trachea (tracheomalacia, TM) and are treated with oxygen or positive pressure ventilation to support breathing (1, 2). Previous studies reported that one out of every 2,100 newborns is diagnosed with TM (3). However, the prevalence of TM may be higher than reported in the literature because TM is primarily diagnosed by bronchoscopy (4, 5). Bronchoscopy is not widely performed in infants unless TM is strongly suspected, usually as a comorbidity with other conditions such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) or tracheoesophageal fistula/esophageal atresia (TEF/EA) (4–6). However, it is difficult to characterize whether TM or other pulmonary comorbidities contribute more toward the respiratory effort.

One method to quantify the effect of TM on respiratory effort is to evaluate the work of breathing (WOB). Although bronchoscopy cannot quantify respiratory effort, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models of respiration can calculate the amount of energy used to move air through the trachea, i.e., the tracheal resistive contribution to WOB (7, 8). Quantifying tracheal resistive WOB can provide a novel measure of disease severity and may in the future provide important data to improve patient care. For example, newborns diagnosed with BPD need additional energy to support breathing (9–11), but there is no current method to assess how much extra energy is spent during breathing. CFD simulations can provide such answers but are computationally expensive and time-consuming (7, 12). Identifying more readily available airway geometrics and clinical metrics that predict tracheal resistive WOB may help clinicians to assess respiratory effort in the dynamic neonatal airway without performing CFD simulations.

In the current literature, airway collapsibility and airway diameter are acknowledged as primary characteristics associated with increases in airway resistance, which raises respiratory effort (13, 14). However, it is not clear whether these airway measurements alone make the largest contribution to WOB. For example, some subjects with TM narrow their glottis to generate auto-positive end-expiratory pressure (auto-PEEP) (15). This glottis narrowing also increases the WOB in the trachea in this patient population. In adults, tracheal curvature has also been shown to increase breathing effort (16). Several studies have investigated the relationship between the WOB and airway geometric measurements such as cross-sectional area. For example, a strong relationship has been demonstrated between WOB and the percent area of obstruction due to subglottic stenosis in neonates (8). Another study showed that even small intrasubject variations in airway cross-sectional area through the breathing cycle can affect the WOB (12). However, various geometric measurements characterize airway anatomy and these studies have not investigated which measurements have the largest effect on WOB. This study uses MRI-based CFD to calculate the tracheal resistive WOB in neonates with and without TM and investigates the relationship between WOB and various imaging and respiratory metrics. Ultrashort echo time (UTE) MRI is used to create airway anatomy models for respiratory CFD simulations and to make geometric measurements of the trachea and airway (7, 17, 18). More straightforward metrics, which predict neonates’ WOB, may provide an important diagnostic tool in the treatment of neonates with airway disease.

METHODS

Subject Cohort

This research study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center; 30 neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) subjects were recruited with written parental consent. All subjects were breathing room air or using a nasal cannula, high-flow nasal cannula, or RAM continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) at the time of MRI, with no intubation (Table 1). Twenty-four of the subjects had underlying conditions such as BPD, tracheoesophageal fistula/esophageal atresia, or bronchoesophageal fistula, and there were six respiratory controls without any airway or lung defects. The diagnosis of TM was evaluated based on clinical bronchoscopy in 17 out of 30 subjects. In the other 13 subjects, the diagnosis of TM was determined via UTE MRI if the tracheal collapse was greater than 40%, as described by Hysinger et al (4).

Table 1.

Subject information

| Clinical Diagnosis | Cohort Size | Gender (M/F) | PMA at MRI (Mean ± SD, wk) | Height at MRI (Mean ± SD, cm) | Body Mass at MRI (Mean ± SD, kg) | Respiratory Support at MRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | 30 | (13/17) | 30.6 ± 5.6 | 47.9 ± 3.5 | 3.3 ± 0.7 | Room air (13), NC (4), HFNC (8), RAM CPAP (5) |

| Respiratory control | 6 | (2/4) | 39.9 ± 1.5 | 47.9 ± 2.4 | 3.1 ± 0.6 | Room air (6) |

| BPD | 18 | (9/9) | 41.9 ± 3.5 | 47.2 ± 4.0 | 3.5 ± 0.8 | Room air (4), NC (3), HFNC (7), RAM CPAP (4) |

| TEF/EA/BEF | 6 | (2/4) | 40.2 ± 0.5 | 49.9 ± 2.2 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | Room air (3), NC (1), HFNC (1), RAM CPAP (1) |

BEF, bronchoesophageal fistula; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; HFNC, high flow nasal cannula; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NC, nasal cannula; PMA, postmenstrual age; TEF/EA, tracheoesophageal fistula/esophageal atresia.

Image and Statistical Analysis

The UTE MRI acquisition, respiratory-gated MR image reconstruction, and the computational modeling of the airway based on patient-specific MRI data have previously been published (7, 12, 15) and are explained further in appendix.

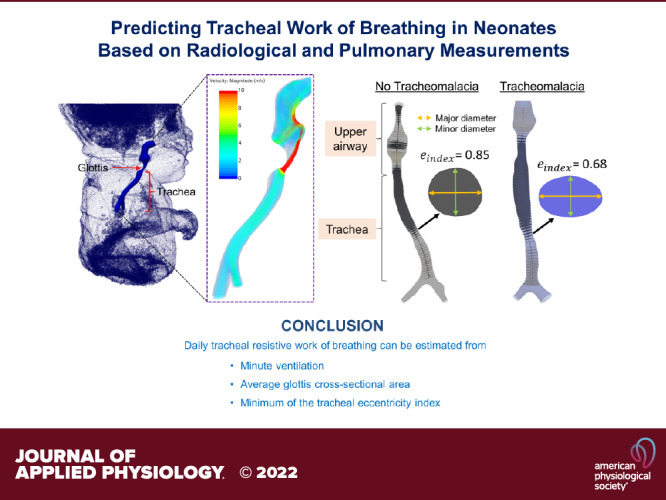

To calculate the cross-sectional area and diameter along the airway, an airway centerline was generated for each subject (16, 19, 20). Cross-sectional planes were created orthogonal to the centerline, 1 mm apart. In each plane, the eccentricity index was measured from the ratio between minor and major diameters (21). To obtain the major diameter of the cross-section, the maximum distance between two points on the perimeter was calculated. The minor diameter was determined by calculating the maximum distance on the cross section, which was orthogonal to the major diameter at its midpoint. Figure 1A shows the airway derived from the end-expiration MR image in two example subjects, one without TM (left) and one with TM (right). The eccentricity index of the two planes was 0.85 in the subject without TM and 0.68 in the subject with TM.

Figure 1.

The airway obtained from end-expiration image in an example subject without tracheomalacia (left) and a subject with tracheomalacia (right; A). Cross-sectional area change along the airway of an example subject with tracheomalacia between end-expiration (green) and end-inspiration (black) time points (B). Airflow velocity distribution at peak expiration in an example subject without tracheomalacia (left) and a subject with tracheomalacia (right; C). A: the cross-sectional planes were created orthogonal to the centerline in each airway. The tracheal cross section in the subject without tracheomalacia was more circular compared with the subject with tracheomalacia. B: the maximum percent change in the cross-sectional area compared with the end-inspiration cross-sectional area in the trachea was 65% (red arrow). C: the daily tracheal resistive work of breathing was 24 and 317 J in the subject without tracheomalacia and with tracheomalacia, respectively. In the subject with tracheomalacia, the high-velocity jet in the lower region of the trachea elevated the breathing effort.

The percent change in the cross-sectional area between inspiration and expiration was calculated relative to end inspiration (22). The end-inspiration and end-expiration airway surfaces were used for the analysis. Figure 1B demonstrates the cross-sectional area change along the airway in an example subject with TM at end-expiration (green curve) and end inspiration (black curve). To calculate the average (temporal mean) glottis cross-sectional area during the breathing cycle, the glottis cross-sectional area in end-expiration, peak inspiration, end inspiration, and peak expiration airway surfaces were measured. The airway volume between the glottis and carina at end-expiration was computed to obtain the tracheal volume.

Each subject’s clinical data such as birth body mass, gestational age, height, body mass, body surface area, and postmenstrual age at MRI were obtained from medical records. The lung tidal volume and single breath duration were calculated from MRI data as explained in appendix. Minute ventilation and respiratory rate were estimated using lung tidal volume and breath duration.

The tracheal resistive WOB is the change in the energy flux between the distal and proximal ends of the trachea (carina and glottis) integrated over one breathing cycle and was calculated using the airflow velocity and total pressure distributions in the trachea (glottis to carina), which were derived from CFD simulations (12). Figure 1C demonstrates airflow velocity distribution at the peak expiration time point in two example subjects, one without TM (left) and one with TM (right). The daily tracheal resistive WOB of each subject was calculated using the single-breath WOB and the respiratory rate.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients were used to find the relationship between daily tracheal resistive WOB and various airway, respiratory, and clinical measurements. The statistical significance of Spearman’s correlation was tested using Fisher transformed z-statistic with α = 0.05. Multivariable linear regression models were developed to find the significant factors that affect the tracheal resistive WOB. Only mutually independent covariates were considered in each model and R2 was used to judge the models’ adequacy. The final model included the covariates if the effects were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

Neonatal Subjects Demographics

Out of 30 subjects, 15 subjects were diagnosed with TM, whereas the other half of the subjects did not have TM. Table 1 shows the subjects’ diagnoses, demographics, and respiratory support during MRI.

The Relationship between Airway Measurements and Work of Breathing

The relationship between daily tracheal resistive WOB and some example airway measurements is shown in Fig. 2. Figure 2, A–D shows the WOB versus the maximum percent change in the tracheal cross-sectional area, average glottis cross-sectional area, tracheal volume at end-expiration, and the minimum of the eccentricity index of the trachea, respectively. In most of the subjects with TM, the maximum percent change in the tracheal cross-sectional area was above 40% (Fig. 2A) and the glottis cross-sectional area was below 8 mm2 (Fig. 2B). According to the Spearman’s coefficients, maximum percent change in the tracheal cross-sectional area (ρ = 0.560, P = 0.001) and average glottis cross-sectional area (ρ = −0.488, P = 0.006) were statistically significant as predictors of tracheal resistive WOB. The minimum of eccentricity index of the trachea was less than 0.70 in 60% of the subjects with TM (Fig. 2D). In addition to measurements shown in Fig. 2, the Spearman’s coefficients of the minimum tracheal cross-sectional area (ρ = −0.497, P = 0.005), average tracheal diameter (ρ = −0.409, P = 0.025), and tracheal length (ρ = −0.229, P = 0.224) were measured.

Figure 2.

The daily tracheal resistive work of breathing vs. maximum percent change in the tracheal cross-sectional area (A), average glottis cross-sectional area (B), tracheal volume at end expiration time point (C), and minimum of the eccentricity index of the trachea (D). Black and blue dots represent neonates without tracheomalacia and with tracheomalacia, respectively. ρ, P are Spearman’s coefficients. TM, tracheomalacia.

The Relationship between Clinical Measurements and Work of Breathing

The daily tracheal resistive WOB versus some example clinical measurements of each subject were compared. Figure 3 demonstrates the daily tracheal resistive WOB versus minute ventilation (Fig. 3A), lung tidal volume (Fig. 3B), respiratory rate (Fig. 3C), and body mass (Fig. 3D). The Spearman’s coefficients of minute ventilation and lung tidal volume were ρ = 0.613, P < 0.001 and ρ = 0.599, P < 0.001, respectively. The respiratory rate and body mass were not significant (P > 0.05). In addition to clinical measurements shown in the figure, height, body surface area, gestational age, and postmenstrual age at MRI were included in the study. However, these variables were not statistically significant in predicting tracheal resistive WOB (P > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Plots showing the daily tracheal resistive work of breathing vs. minute ventilation (A), lung tidal volume (B), respiratory rate (C), and body mass (D). Black and blue dots represent neonates without tracheomalacia and with tracheomalacia, respectively. ρ, P are Spearman’s coefficients. TM, tracheomalacia.

Multivariate Analysis Results

To predict WOB more precisely in the trachea, two multivariable linear regression models were developed and are shown in Table 2. The dependent variable in the first model was daily tracheal resistive WOB (y). Of the various airway and clinical measurements listed in The Relationship between Airway Measurements and Work of Breathing and The Relationship between Clinical Measurements and Work of Breathing sections, the combination of minute ventilation (x1), average glottis cross-sectional area (x2), and the minimum of the eccentricity index of the trachea (x3) predicted daily WOB (R2 = 0.726). The multivariable linear regression equation to determine the daily tracheal resistive WOB can be expressed as follows using the coefficients listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of factors affecting work of breathing

| Dependent Variable | R 2 | Independent Variable | Coefficient | Standard Error | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily tracheal resistive work of breathing, J/day | 0.726 | Intercept | 985.633 | 310.781 | 0.004 |

| Minute ventilation, mL/min | 0.466 | 0.080 | <0.001 | ||

| Average glottis cross-sectional area, mm2 | −31.993 | 8.041 | <0.001 | ||

| Minimum of the eccentricity index of the trachea | −1,397.950 | 446.960 | 0.004 | ||

| Tracheal resistive work of breathing per mL of air, kJ/mL | 0.677 | Intercept | 0.779 | 0.186 | <0.001 |

| Lung tidal volume, mL | 0.009 | 0.003 | 0.004 | ||

| Average glottis cross-sectional area, mm2 | −0.016 | 0.004 | 0.002 | ||

| Minimum of the eccentricity index of the trachea | −0.940 | 0.261 | 0.001 |

In a second model, the dependent variable was tracheal resistive WOB per milliliter of air inhaled. This model included lung tidal volume, average glottis cross-sectional area, and the minimum of eccentricity index of the trachea (R2 = 0.677). All independent variables in each model were statistically significant. Using the coefficients in Table 2, a similar equation can be written to calculate the tracheal resistive WOB per milliliter of air inhaled.

DISCUSSION

The main finding of this study is that tracheal resistive WOB depends on several airway and clinical measurements. The combination of minute ventilation, average glottis cross-sectional area, and the minimum of eccentricity index of the trachea can most accurately estimate the daily tracheal resistive WOB. These airway and clinical measurements can be obtained from medical images and clinical data and allow estimation of tracheal resistive WOB without performing CFD simulations.

According to current clinical guidelines, subjects with TM exhibit airway collapse greater than 50%, and the severity of TM is graded based on the percentage that the airway collapses on bronchoscopy (23). However, Fig. 2A demonstrated that although the degree of collapse correlates with the increase in tracheal resistive WOB due to the collapse (P = 0.001), there is a wide degree of variation (ρ = 0.56) and therefore, the degree of collapse may not be the most sensitive indicator of tracheal disease. For example, some subjects with ∼40% tracheal collapse have a higher WOB than those with 60%–70% collapse. Similarly, eight of the patients with TM do not exhibit collapse of greater than 50% and five of those eight do not exhibit increased work of breathing. Previously, Masters et al. (24) showed that bronchoscopic assessment of airway collapse does not correlate with clinical outcomes. Their finding may be related to the lack of correlation between collapse and WOB, assuming that there is a relationship between WOB and clinical outcomes. In addition, it is not significant in the multivariate analysis.

The findings of this study reveal that the tracheal WOB depends on multiple factors such as the shape of the airway lumen (airway eccentricity index) and the glottis cross-sectional area since the glottis controls airflow into the trachea (15). In the future, thresholds for each variable may be identified above which increased WOB is more likely. Estimating the WOB in the trachea based on the multiregression model introduced in this study would help clinicians in assessing a patient’s TM and thus in distinguishing symptoms or disease severity caused by the TM from those caused by other underlying diseases such as BPD or TEF/EA. For example, a healthy subject with minute ventilation of 900 mL/min, an average glottis cross-sectional area of 11 mm2, and a minimum of the eccentricity index of the trachea of 0.73 would have estimated tracheal resistive WOB of 33 J/day, whereas a subject with TM would have estimated tracheal resistive WOB of 370 J/day (minute ventilation 1,100 mL/min, average glottis cross-sectional area 6 mm2, and minimum of the eccentricity index of the trachea = 0.67).

Previous studies have calculated the total resistive WOB of the respiratory system in neonates with various pulmonary disorders (25–27). Bhutani et al. (27) found a linear relationship between total resistive WOB in the entire respiratory system and tidal volume and minute ventilation based on 22 premature infants with respiratory failure and no relationship was found between total resistive WOB and respiratory rate. Their study calculated transpulmonary pressure using esophageal pressure measurement, a minimally invasive procedure, to estimate the total resistive WOB. In contrast, our study highlights the relationship between tracheal resistive WOB and minute ventilation, lung tidal volume, and found no relationship between WOB and respiratory rate based on noninvasively computational modeling of the respiratory airflow in the airway. However, none of these variables separate subjects with TM and subjects without TM.

Many MR images of the airway represent an average image that would blur motion during the breathing cycle. However, the UTE MR imaging technique used in this study allows the reconstruction of airway images with dynamic tracheal size and shape at different phases of the breathing cycle (e.g., end expiration) (7, 17). The three-dimensional (3-D), high-resolution MRI method used in this study is noninvasive and has minimal risk compared with other imaging modalities with comparable resolution such as computed tomography (CT). UTE MRI is extensively used in research settings, and it is likely to be commercially available in the near future.

The minimum airway eccentricity index and average glottis cross-sectional area both calculations were based on dynamic images, which represent specific time points during breathing. When dynamic images are not available, the average glottis cross-sectional area could be determined from an ungated image, which shows the average position of the anatomy during the respiratory cycle. Tracheal collapse tends to occur during expiration, therefore images showing the tracheal anatomy during expiration are required to find the minimum eccentricity of the trachea and could perhaps be obtained using prospectively gated images using respiratory bellows. Similarly, the results of this study were based on three-dimensional models of the airway. When these airway models are not available, the minimum airway eccentricity index could be directly determined from medical images. The collapsed region of the trachea is typically where the eccentricity index is lowest, and the eccentricity index can be determined by measuring the minor and major tracheal diameters directly from MRI in that region to obtain the airway eccentricity index from the ratio of the diameters.

This model only predicts the tracheal resistive component of WOB. Although glottis narrowing increases this component of WOB, it may decrease the total WOB by preventing tracheal or distal airway collapse. Future studies will investigate the relationship between glottis narrowing and the total WOB to determine how the increase in tracheal resistive WOB is counteracted by decreases in other components of WOB.

One of the limitations of this study is its relatively modest size (n = 30 subjects). The presence of an endotracheal tube will likely affect airway dynamics, and intubated subjects were not included in this study; since our NICU inpatients tend to be more severe and intubated, this limited the sample size. As a result, our multivariate model was limited to three independent variables. Running more patient-specific CFD simulations can improve the accuracy of the model with more clinical or airway measurements. Another limitation of this study is that MR images were acquired, whereas the subjects were in a resting state or sleeping. The images should therefore be representative of the baby resting when outside of the scanner. However, this restful breathing pattern does not represent all behaviors such as crying or breathing during increased activity.

These CFD simulations on respiratory airflow demonstrated that WOB can be calculated in a specific region of the respiratory system—in this manuscript, the trachea. Clinicians will be able to anticipate resistive WOB specific to the trachea based on clinical and airway measures, which will aid in determining the severity and clinical relevance of TM.

Conclusions

This study identifies clinical and airway measurements that are significantly associated with tracheal resistive WOB based on CFD simulations. Although the degree of airway collapse is related to an increase in WOB in subjects with TM, other variables are also related to an increase in WOB. The tracheal resistive WOB depends on minute ventilation, minimum of the airway eccentricity index (i.e., the shape of the trachea when it is least round), and the average glottis cross-sectional area. The percent change in the tracheal cross-sectional area is typically used to assess TM endoscopically, but this metric was found to be less sensitive than the above metrics. This multivariate model may allow assessment of the neonatal trachea separately from lung parenchymal issues based on medical imaging and clinical data.

GRANTS

This research was funded by the Academic and Research Committee at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R00 HL144822, and R01 HL146689.

DISCLOSURES

A. J. Bates has research agreements with Philips and Siemens PLM software, and J. C. Woods has a research agreement with Philips.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.C.G., E.B.H., J.C.W., and A.J.B. conceived and designed research; C.C.G. and N.S.H. performed experiments; C.C.G., E.B.H., A.S., Q.X., D.B.G., M.M.H., and A.J.B. analyzed data; C.C.G., E.B.H., N.S.H., D.I., M.M.H., R.J.F., J.C.W., and A.J.B. interpreted results of experiments; C.C.G. prepared figures; C.C.G., E.B.H., A.S., Q.X., N.S.H., D.I., M.M.H., R.J.F., J.C.W., and A.J.B. drafted manuscript; C.C.G. and A.J.B. edited and revised manuscript; A.J.B. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients and families for participation in this study.

APPENDIX

Obtaining Mri Data and Image Reconstruction

The central airway and lungs of each neonate were imaged using a neonatal MRI scanner (field strength 1.5 T, bore size 18 cm) sited within the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) (18, 28–31). The resolution of the three-dimensional ultrashort echo time (UTE) MR images was 0.7 × 0.7 × 0.7 mm. Each MRI scan took ∼16 min, and 200,000 projections were recorded during the entire scan. Imaging parameters were echo time = 0.2 ms, flip angle = 5°, repetition time = 5.2 ms, image matrix = 256 × 256 × 256 (7, 17, 18).

Since TM is a disease involving airway dynamics, airway images were required at different phases of the respiratory cycle. To achieve this, UTE MRI data were respiratory-gated to reconstruct four images corresponding to different time points of the breathing cycle described previously (7, 17, 18). The initial point of the MRI free induction decay waveform was modulated due to the bulk motion and breathing of the neonate. After removing the bulk motion data, the rest of the MRI data was binned into four bins based on the amplitude of each breathing cycle. For each subject, four MR images were reconstructed showing end expiration, peak inspiration, end inspiration, and peak expiration (7, 32, 33). The peak inspiration and peak expiration image time points represent the maximum inspiratory and expiratory flow, respectively.

CFD Inputs—Airway Motion and Airflow Rates

To obtain a virtual airway surface and the airway motion throughout the breathing cycle, airways surfaces were segmented from each binned MR image using a three-dimensional active contour segmentation technique in ITK-SNAP software (version 3.8.0) (34). The mean intensity between the tissue surrounding the airway and the air-filled airway was used as the threshold intensity of the segmentation to standardize any uncertainty that occurred during the segmentation process. Segmented airway surfaces were smoothed using the Taubin smoothing filter in MeshLab 2016 (35, 36). Smoothed airway surfaces of each subject were registered using the Medical Image Registration ToolKit (version 1.1) software to determine the position of the airway at any instant during the breathing cycle (7, 12, 37). Each virtual airway extended from main bronchi to above the larynx (upper airway coverage varied 15 mm from larynx).

The airflow rates in the main bronchi were based on changes in lung volume and the respiratory waveform acquired from the raw MRI data. The lung tidal volume was calculated by segmenting the lungs in the MR images at end inspiration and end-expiration time points. A median breathing waveform from the 16 min of collected data was evaluated as a representative waveform, and this median waveform was scaled based on the lung tidal volume. Airflow rates of the left and right bronchi were derived by differentiating the volume curves with respect to time (7, 12).

CFD Modeling of the Airway

A patient-specific computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation was performed for each subject to model airflow in the airway using commercial CFD software, STAR-CCM+ 14.04.011-R8 (Siemens PLM Software). The large-eddy simulation was used to model turbulence. The no-slip condition was applied, in which the airflow velocity at the airway surface was considered to be zero relative to the airway wall. Airflow rates were applied at the main bronchi and the inlet of the airway was held at atmospheric pressure (15). The discretized airway included polyhedral cells in the interior and prism layers on the wall. The airway mesh size was 2 million cells, and the temporal resolution of the simulation was 0.8 ms, which was determined after performing a convergence study (12). The air was considered to be isothermal and incompressible at body temperature. As previously stated, the airway motion throughout the breathing cycle was integrated into the CFD model. (12). After running the CFD simulation for a single breath, daily tracheal resistive work of breathing (WOB) was calculated using the single-breath energy expenditure and respiratory rate (12).

REFERENCES

- 1. Hysinger EB, Friedman NL, Padula MA, Shinohara RT, Zhang H, Panitch HB, Kawut SM; Children’s Hospitals Neonatal Consortium. Tracheobronchomalacia is associated with increased morbidity in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Ann Am Thorac Soc 14: 1428–1435, 2017. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201702-178OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Carden KA, Boiselle PM, Waltz DA, Ernst A. Tracheomalacia and tracheobronchomalacia in children and adults: an in-depth review. Chest 127: 984–1005, 2005. doi: 10.1378/CHEST.127.3.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boogaard R, Huijsmans SH, Pijnenburg MWH, Tiddens HAWM, De Jongste JC, Merkus PJFM. Tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children: incidence and patient characteristics. Chest 128: 3391–3397, 2005. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hysinger EB, Bates AJ, Higano NS, Benscoter D, Fleck RJ, Hart CK, Burg G, De Alarcon A, Kingma PS, Woods JC. Ultrashort echo-time MRI for the assessment of tracheomalacia in neonates. Chest 157: 595–602, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCubbin M, Frey EE, Wagener JS, Tribby R, Smith WL. Large airway collapse in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr 114: 304–307, 1989. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(89)80802-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Higano NS, Bates AJ, Gunatilaka CC, Hysinger EB, Critser PJ, Hirsch R, Woods JC, Fleck RJ. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia from chest radiographs to magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography: adding value. Pediatr Radiol 52: 643–660, 2022. [Erratum in Pediatr Radiol 2022]. doi: 10.1007/s00247-021-05250-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gunatilaka CC, Higano NS, Hysinger EB, Gandhi DB, Fleck RJ, Hahn AD, Fain SB, Woods JC, Bates AJ. Increased work of breathing due to tracheomalacia in neonates. Ann Am Thorac Soc 17: 1247–1256, 2020. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202002-162OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang MM, Higano NS, Gunatilaka CC, Hysinger EB, Amin RS, Woods JC, Bates AJ. Subglottic stenosis position affects work of breathing. Laryngoscope 131: E1220–E1226, 2021. doi: 10.1002/lary.29169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anderson C, Hillman NH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia: when the very preterm baby comes home. Mo Med 116: 117–122, 2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Agostoni C, Buonocore G, Carnielli VP, De Curtis M, Darmaun D, Decsi T, Domellöf M, Embleton ND, Fusch C, Genzel-Boroviczeny O, Goulet O, Kalhan SC, Kolacek S, Koletzko B, Lapillonne A, Mihatsch W, Moreno L, Neu J, Poindexter B, Puntis J, Putet G, Rigo J, Riskin A, Salle B, Sauer P, Shamir R, Szajewska H, Thureen P, Turck D, Van Goudoever JB, ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition. Enteral nutrient supply for preterm infants: commentary from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 50: 85–91, 2010. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0B013E3181ADAEE0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lista G, Meneghin F, Bresesti I, Cavigioli F. Nutritional problems of children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia after hospital discharge. Pediatr Med Chir 39: 120–123, 2017. doi: 10.4081/pmc.2017.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gunatilaka CC, Schuh A, Higano NS, Woods JC, Bates AJ. The effect of airway motion and breathing phase during imaging on CFD simulations of respiratory airflow. Comput Biol Med 127: 104099, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Friedman ML, Nitu ME. Acute respiratory failure in children. Pediatr Ann 47: e268–e273, 2018. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20180625-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Trachsel D, Erb TO, Hammer J, von Ungern-Sternberg BS. Developmental respiratory physiology. Paediatr Anaesth 32: 108–117, 2022. doi: 10.1111/PAN.14362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gunatilaka CC, Hysinger EB, Schuh A, Gandhi DB, Higano NS, Xiao Q, Hahn AD, Fain SB, Fleck RJ, Woods JC, Bates AJ. Neonates with tracheomalacia generate auto-positive end-expiratory pressure via glottis closure. Chest 160: 2168–2177, 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bates AJ, Cetto R, Doorly DJ, Schroter RC, Tolley NS, Comerford A. The effects of curvature and constriction on airflow and energy loss in pathological tracheas. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 234: 69–78, 2016. doi: 10.1016/J.RESP.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Higano NS, Hahn AD, Tkach JA, Cao X, Walkup LL, Thomen RP, Merhar SL, Kingma PS, Fain SB, Woods JC. Retrospective respiratory self-gating and removal of bulk motion in pulmonary UTE MRI of neonates and adults. Magn Reson Med 77: 1284–1295, 2017. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hahn AD, Higano NS, Walkup LL, Thomen RP, Cao X, Merhar SL, Tkach JA, Woods JC, Fain SB. Pulmonary MRI of neonates in the intensive care unit using 3D ultrashort echo time and a small footprint MRI system. J Magn Reson Imaging 45: 463–471, 2017. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Piccinelli M, Veneziani A, Steinman DA, Remuzzi A, Antiga L. A framework for geometric analysis of vascular structures: application to cerebral aneurysms. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 28: 1141–1155, 2009. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2021652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bates AJ, Comerford A, Cetto R, Doorly DJ, Schroter RC, Tolley NS. Computational fluid dynamics benchmark dataset of airflow in tracheas. Data Brief 10: 101–107, 2017. doi: 10.1016/J.DIB.2016.11.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gandhi DB, Rice A, Gunatilaka CC, Higano NS, Fleck RJ, De Alarcon A. D, Hart CK, Kuo I-C, Amin RS, Woods JC, Hysinger EB, Bates AJ. Quantitative evaluation of subglottic stenosis using ultrashort echo time MRI in a rabbit model. Laryngoscope 131: E1971–E1979, 2021. doi: 10.1002/LARY.29363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bates AJ, Higano NS, Hysinger EB, Fleck RJ, Hahn AD, Fain SB, Kingma PS, Woods JC. Quantitative assessment of regional dynamic airway collapse in neonates via retrospectively respiratory-gated 1H ultrashort echo time MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 49: 659–667, 2019. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wallis C, Alexopoulou E, Antón-Pacheco JL, Bhatt JM, Bush A, Chang AB, Charatsi AM, Coleman C, Depiazzi J, Douros K, Eber E, Everard M, Kantar A, Masters IB, Midulla F, Nenna R, Roebuck D, Snijders D, Priftis K. ERS statement on tracheomalacia and bronchomalacia in children. Eur Respir J 54: 1900382, 2019. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00382-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Masters IB, Zimmerman PV, Pandeya N, Petsky HL, Wilson SB, Chang AB. Quantified tracheobronchomalacia disorders and their clinical profiles in children. Chest 133: 461–467, 2008. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pandit PB, Courtney SE, Pyon KH, Saslow JG, Habib RH. Work of breathing during constant- and variable-flow nasal continuous positive airway pressure in preterm neonates. Pediatrics 108: 682–685, 2001. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Courtney SE, Aghai ZH, Saslow JG, Pyon KH, Habib RH. Changes in lung volume and work of breathing: a comparison of two variable-flow nasal continuous positive airway pressure devices in very low birth weight infants. Pediatr Pulmonol 36: 248–252, 2003. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bhutani VK, Sivieri EM, Abbasi S, Shaffer TH. Evaluation of neonatal pulmonary mechanics and energetics: a two factor least mean square analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol 4: 150–158, 1988. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1950040306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tkach JA, Li Y, Pratt RG, Baroch KA, Loew W, Daniels BR, Giaquinto RO, Merhar SL, Kline-Fath BM, Dumoulin CL. Characterization of acoustic noise in a neonatal intensive care unit MRI system. Pediatr Radiol 44: 1011–1019, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00247-014-2909-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tkach JA, Merhar SL, Kline-Fath BM, Pratt RG, Loew WM, Daniels BR, Giaquinto RO, Rattan MS, Jones BV, Taylor MD, Tiefermann JM, Tully LM, Murphy EC, Wolf-Severs RN, LaRuffa AA, Dumoulin CL. MRI in the neonatal ICU: initial experience using a small-footprint 1.5-T system. AJR Am J Roentgenol 202: W95–W105, 2014. doi: 10.2214/AJR.13.10613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tkach JA, Hillman NH, Jobe AH, Loew W, Pratt RG, Daniels BR, Kallapur SG, Kline-Fath BM, Merhar SL, Giaquinto RO, Winter PM, Li Y, Ikegami M, Whitsett JA, Dumoulin CL. An MRI system for imaging neonates in the NICU: initial feasibility study. Pediatr Radiol 42: 1347–1356, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00247-012-2444-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Higano NS, Spielberg DR, Fleck RJ, Schapiro AH, Walkup LL, Hahn AD, Tkach JA, Kingma PS, Merhar SL, Fain SB, Woods JC. Neonatal pulmonary magnetic resonance imaging of bronchopulmonary dysplasia predicts short-term clinical outcomes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 198: 1302–1311, 2018. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201711-2287OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pipe JG, Menon P. Sampling density compensation in MRI: rationale and an iterative numerical solution. Magn Reson Med 41: 179–186, 1999. doi:. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jackson JI, Meyer CH, Nishimura DG, Macovski A. Selection of a convolution function for Fourier inversion using gridding (computerised tomography application). IEEE Trans Med Imaging 10: 473–478, 1991. doi: 10.1109/42.97598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, Smith RG, Ho S, Gee JC, Gerig G. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 31: 1116–1128, 2006. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2006.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Taubin G. Curve and surface smoothing without shrinkage. IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Cambridge, MA, 1995, p. 852–857. doi: 10.1109/ICCV.1995.466848. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Cignoni P, Callieri M, Corsini M, Dellepiane M, Ganovelli F, Ranzuglia G. MeshLab: an open-source mesh processing tool. In: 6th Eurographics Italian Chapter Conference 2008 - Proceedings. Salerno, Italy, 2008, p. 129–136. doi: 10.2312/LocalChapterEvents/ItalChap/ItalianChapConf2008/129-136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bates AJ, Schuh A, McConnell K, Williams BM, Lanier JM, Willmering MM, Woods JC, Fleck RJ, Dumoulin CL, Amin RS. A novel method to generate dynamic boundary conditions for airway CFD by mapping upper airway movement with non-rigid registration of dynamic and static MRI. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng 34: e3144, 2018. doi: 10.1002/cnm.3144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]