Abstract

Efg1 is essential for hyphal development in the human pathogen Candida albicans under most conditions. Efg1 is related to basic helix-loop-helix regulators, and therefore most workers presume that Efg1 is a transcription factor. Here we confirm that Efg1 is a DNA binding protein that can interact specifically with the E box.

Candida albicans is the major fungal pathogen of humans (19). This fungus causes frequent and recurrent oral and vaginal infections and systemic infections in severely immunocompromised patients. A number of factors are thought to promote establishment and progression of C. albicans infections, including yeast hypha morphogenesis (5, 16, 20). Several signalling pathways appear to activate hyphal development, and one of these pathways is defined by the factor Efg1 (9, 26). Efg1 probably lies on a Ras-cAMP-protein kinase A signalling pathway (5, 9, 10, 24). Mutations that inactivate Efg1 block hyphal development under most experimental conditions in vitro and in vivo (16, 26). For example, C. albicans efg1/efg1 mutants are unable to form hyphae following serum stimulation or pH induction in vitro or in the kidneys of infected animals. However, efg1/efg1 mutants still form hyphae when they are embedded in agar and in some infection models (6, 21). Nevertheless, Efg1 is considered a major morphogenetic regulator in C. albicans (9).

Ernst and coworkers pointed out that Efg1 contains a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain with significant sequence similarity to the APSES family of proteins (9, 26). Members of this family include morphogenetic regulators from other fungi, such as Sok2 and Phd1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Asm1 from Neurospora crassa, and StuA from Aspergillus nidulans. This bHLH domain, which is characteristic of some transcription factors, is thought to promote dimerization and DNA binding (18, 22). Therefore, it is generally presumed that Efg1 is a transcription factor, and most models of morphogenetic regulation are based on this presumption (5, 9, 26). However, this remains to be confirmed.

Hypha-specific genes carry E-boxes in their promoters.

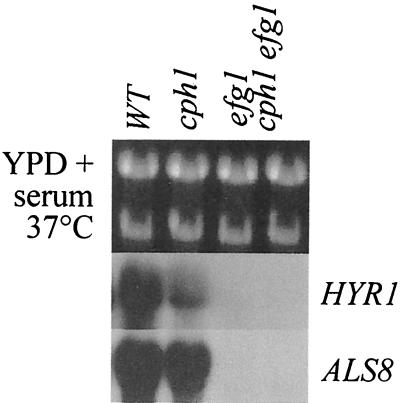

A number of hypha-specific genes have been identified in C. albicans. Several of these genes, such as HWP1, HYR1, ALS3, and ALS8, encode hyphal wall proteins (1, 12, 14, 25). The functions of other genes, such as ECE1 and RBT4, remain obscure (2–4). Activation of some hypha-specific genes depends upon Efg1 but not upon Cph1 (3, 23). Cph1 is a Ste12-like transcription factor which lies on the MAP kinase signalling pathway that regulates C. albicans morphogenesis (13, 15). We tested whether ALS8 and HYR1 are regulated by Efg1 and Cph1 by using an isogenic set of C. albicans strains (Fig. 1). Both mRNAs were induced following serum stimulation in wild-type and cph1/cph1 cells, but they were not induced in efg1/efg1 cells or an efg1/efg1 cph1/cph1 double mutant. Hence, as expected (3, 23), activation of ALS8 and HYR1 was dependent upon Efg1 but not upon Cph1 under these conditions.

FIG. 1.

Efg1p is required for HYR1 and ALS8 activation during serum-induced morphogenesis. We performed a Northern analysis with isogenic C. albicans strains grown for 2 h in YPD containing 10% fetal calf serum at 37°C; the strains used were wild-type strain SC5314 (WT) (11), cph1/cph1 strain JKC19 (15), efg1/efg1 strain HLC52 (16), and cph1/cph1 efg1/efg1 strain HLC54 (54). ALS8 and HYR1 blots were exposed for 8 h and 4 days, respectively. Data from one of two replicate experiments are shown.

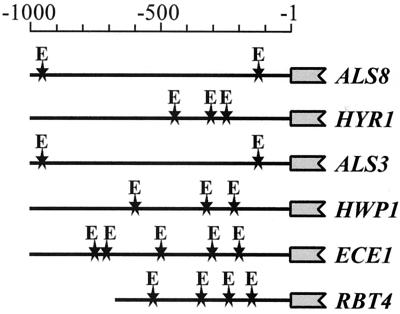

bHLH transcription factors related to Efg1 are known to bind to the E box (consensus sequence, 5′-CANNTG-3′ [18, 22]). Hence, we studied whether the promoter regions of hypha-specific genes contain E boxes by using regulatory sequence analysis tools (27). The ALS3, ALS8, ECE1, HYR1, HWP1, and RBT4 promoters all contain multiple E boxes (Fig. 2), which is consistent with the idea that Efg1 interacts with the E box to regulate expression of these promoters.

FIG. 2.

Hypha-specific promoters contain E boxes. The positions of E boxes (5′-CANNTG-3′) (stars) are shown in the 5′ regions of the ALS8, HYR1 ALS3, HWP1, ECE1 and RBT4 promoters (http://www-sequence.stanford.edu/group/candida). The scale is relative to the first nucleotide of each coding region.

Synthetic Efg1 binds to an E box.

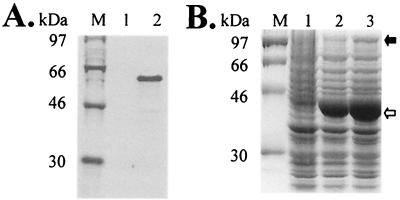

To test whether Efg1 can interact with an E box, we made two forms of synthetic Efg1. First, Efg1 was made with the TNT coupled in vitro transcription-translation system (Promega, Southampton, United Kingdom) by using pGEM-EFGI, which contains the PCR-amplified and resequenced EFG1 open reading frame in pGEM11Z (Promega). Second, a maltose binding protein (MBP)-Efg1 fusion was made in Escherichia coli by using pMAL-EFG1 (17), which contains the EFG1 open reading frame cloned into pMAL-c (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Mass.) (8). The levels of expression of MBP-Efg1 were low, apparently because this protein was toxic to E. coli. Nevertheless, the in vitro Efg1 and MBP-Efg1 were the expected sizes (Fig. 3) given the predicted molecular mass of Efg1, 60 kDa (26).

FIG. 3.

Production of synthetic Efg1s. (A) In vitro transcription and translation of EFG1: sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel containing [35S]-labelled reaction product. Lane M, markers; lane 1, control reaction with empty pGEM11Z vector; lane 2, reaction with pGEM-EFG1. (B) Synthesis of a MBP-Efg1 fusion protein in E. coli: Coomassie blue-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel containing soluble protein extracts. Lane M, size markers; lane 1, pMAL-c and no IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside); lane 2, pMAL-c with IPTG; lane 3, pMAL-EFG1 with IPTG. The positions of MBP (open arrow) and MBP-Efg1 (solid arrow) are indicated on the right.

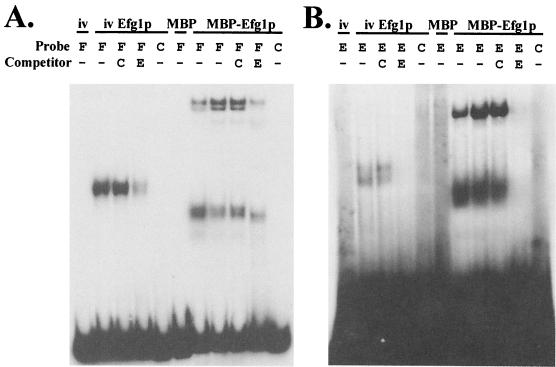

Both synthetic Efg1s were used in gel shift experiments (7) to test whether they interacted specifically with E box-containing DNA fragments. Both Efg1s formed complexes with a 90-bp region of the ALS8 promoter that contains an E box (Fig. 4A) and an E box-containing oligonucleotide (Fig. 4B). These complexes were competed out by E box-containing DNA molecules but not by a control oligonucleotide lacking an E box. Furthermore, the complexes were not formed by control extracts lacking Efg1. Therefore, Efg1 is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein capable of binding the E box.

FIG. 4.

Synthetic Efg1s interact specifically with the E box in vitro. (A) Gel shift assays in which an E box-containing fragment from the ALS8 promoter (−196 to −106) was used. (B) Gel shift assay in which an E box-containing oligonucleotide was used. The extracts used included a control in vitro transcription and translation extract lacking EFG1 (iv), an analogous extract containing EFG1 (iv Efg1p), a control E. coli extract containing the empty MBP expression plasmid (MBP), and an analogous extract containing the MBP-EFG1 fusion plasmid (MBP-Efg1p) (Fig. 3). The probes and competitors used were an ALS8 promoter fragment (F) (−196 to −106), an E box-containing oligonucleotide (E) (5′-AGAGATGCATTTGCTAGAGATGCATTTGCTAGACTT), and a control oligonucleotide lacking E boxes (C) (5′-AGAGATGTGCCGATTAGAGATGTGCCGATTAGACTT).

A hypha-specific promoter forms an Efg1-dependent complex.

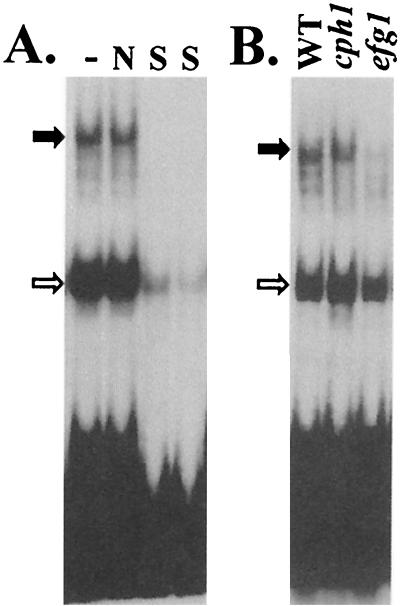

We then tested whether a hypha-specific promoter is able to form Efg1-dependent complexes with C. albicans cell extracts. A 90-bp ALS8 promoter fragment, which contained an E box, formed sequence-specific complexes with wild-type extracts (Fig. 5A). This fragment formed similar complexes with cell extracts prepared from yeast or hyphal cells (data not shown). Formation of the largest of these complexes was inhibited by inactivation of Efg1 but not by inactivation of Cph1. Therefore, the E box-containing region of the ALS8 promoter formed an Efg1-dependent complex.

FIG. 5.

E box region from the ALS8 promoter forms Efg1-dependent complexes with C. albicans extracts. Gel shift assays were performed with an E box-containing fragment from the ALS8 promoter (−196 to −106). (A) Complexes formed with cell extracts from wild-type C. albicans strain SC5314 and no competitor (−) a nonspecific competitor (N), or a specific competitor (S) (10-fold excess and then 20-fold excess of unlabelled E box fragment). (B) Cell extracts from wild-type strain SC5314, cph1/cph1 strain JKC19, and efg1/efg1 strain HLC52. The positions of sequence-specific Efg1-dependent complexes (solid arrow) and sequence-specific Efg1p-independent complexes (open arrow) are indicated on the left. The experiments were performed with cell extracts prepared from yeast cells growing on YPD at 25°C. Similar complexes were formed with extracts prepared from cells growing on YPD containing 10% serum at 37°C (data not shown).

The specificity of this interaction was examined further by testing whether other fragments of the ALS8 promoter, which lacked an E box, were capable of forming this Efg1-dependent complex. The following fragments were examined by using extracts prepared from wild-type and efg1/efg1 cells: −696 to −597, −596 to −495, −496 to −388, −412 to −281, and −306 to −197. None of these ALS8 promoter fragments generated the Efg1-dependent complex (data not shown), unlike the E box region (−196 to −106) (Fig. 5). The observation that the Efg1-dependent complex can form with cell extracts from yeast cells (Fig. 5A) and the observation that synthetic forms of Efg1 can interact directly with the E box (Fig. 4) suggest that this DNA binding activity is not dependent on activation of Efg1 by a morphogenetic stimulus.

Ernst (9) has pointed out that bHLH proteins can regulate genes that do not contain an E box. Also, we did not identify an E box in the 5′ region of RBT1, which is regulated by Efg1 (3). It is conceivable that RBT1 is regulated indirectly by Efg1 or that Efg1 can bind sequences other than E boxes. Nevertheless, our data confirm that Efg1 is a sequence-specific DNA binding protein that is capable of binding the E box and that most hypha-specific genes contain E boxes in their promoters. This is consistent with the idea that Efg1 interacts directly with hypha-specific promoters in C. albicans to activate transcription of the promoters during hyphal development, and this has important implications for regulation of cellular morphogenesis in this human pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gerald Fink and Joachim Ernst for providing strains, Lois Hoyer for providing information about the ALS3 promoter, and Susan Budge for excellent technical assistance. We are grateful to the Stanford DNA Sequencing and Technology Center for access to their C. albicans genome sequence data (http://www-sequence.stanford.edu /group/candida), which were generated with the support of the NIDR and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

P.L. was supported by the UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (grants 1/CEL4563 and 97/B1/P/03008). P.R.L. and A.J.P.B. were supported by The Wellcome Trust (grants 041399, 055015, and 063204).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey D A, Feldmann P J F, Bovey M, Gow N A R, Brown A J P. The Candida albicans HYR1 gene, which is activated in response to hyphal development, belongs to a gene family encoding yeast cell wall proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5353–5360. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5353-5360.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birse C E, Irwin M Y, Fonzi W A, Sypherd P S. Cloning and characterization of ECE1, a gene expressed in association with cell elongation of the dimorphic pathogen Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3648–3655. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3648-3655.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braun B R, Johnson A D. TUP1, CPH1 and EFG1 make independent contributions to filamentation in Candida albicans. Genetics. 2000;155:57–67. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun B R, Head W S, Wang M X, Johnson A D. Identification and characterization of TUP1-regulated genes in Candida albicans. Genetics. 2000;156:31–44. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown A J P, Gow N A R. Regulatory networks controlling Candida albicans morphogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:333–338. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01556-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown D H, Giusani A D, Chen X, Kumamoto C A. Filamentous growth of Candida albicans in response to physical environmental cues and its regulation by the unique CZF1 gene. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:651–662. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey J. Gel retardation. Methods Enzymol. 1991;208:103–117. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08010-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.di Guan C, Li P, Riggs P D, Inouye H. An Escherichia coli vector to express and purify foreign proteins by fusion to and separation from maltose-binding protein. Gene. 1987;67:21–30. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ernst J F. Transcription factors in Candida albicans—environmental control of morphogenesis. Microbiology. 2000;146:1763–1774. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feng Q, Summers E, Guo B, Fink G. Ras signaling is required for serum-induced hyphal differentiation in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6339–6346. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6339-6346.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillum A M, Tsay E Y, Kirsch D R. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;198:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00328721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoyer L L, Payne T L, Bell M, Myers A M, Scherer S. Candida albicans ALS3 and insights into the nature of the ALS gene family. Curr Genet. 1998;33:451–459. doi: 10.1007/s002940050359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leberer E, Harcus D, Broadbent I D, Clark K L, Dignard D, Ziegelbauer K, Schmit A, Gow N A R, Brown A J P, Thomas D Y. Homologs of the Ste20p and Ste7p protein kinases are involved in hyphal formation of Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13217–13222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leng P. Gene regulation during morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Ph.D. thesis. Aberdeen, United Kingdom: University of Aberdeen; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu H, Kohler J R, Fink G R. Suppression of hyphal formation in Candida albicans by mutation of a STE12 homolog. Science. 1994;266:1723–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.7992058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo H J, Kohler J R, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Fink G R. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell. 1997;90:939–949. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malathi K, Ganesan K, Datta A. Identification of a putative transcription factor in Candida albicans that can complement the mating defect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae ste12 mutants. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:22945–22951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massari M E, Murre C. Helix-loop-helix proteins: regulators of transcription in eucaryotic organisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:429–440. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.2.429-440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Odds F C. Candida and candidosis. 2nd ed. London, United Kingdom: Bailliere Tindall; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odds F C. Candida species and virulence. ASM News. 1994;60:313–318. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riggle P J, Anduitis K A, Chen X, Tzipore S R, Kamumoto C A. Invasive lesions containing filamentous forms produced by a Candida albicans mutant that is defective in filamentous growth in culture. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3649–3652. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3649-3652.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinson K A, Lopes J M. Saccharomyces cerevisiae basic helix-loop-helix proteins regulate diverse biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:1499–1505. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.7.1499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sharkey L L, McNemar M D, Saporito-Irwin S M, Sypherd P S, Fonzi W A. HWP1 functions in the morphological development of Candida albicans downstream of EFG1, TUP1 and RBF1. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5273–5279. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.17.5273-5279.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sonneborn A, Bockmuhl D P, Gerads M, Kurpanek K, Sanglard D, Ernst J F. Protein kinase A encoded by TPK2 regulates dimorphism of Candida albicans Mol. Microbiol. 2000;35:386–396. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Staab J F, Ferrer C A, Sundstrom P. Developmental expression of a tandemly repeated, proline and glutamine-rich amino acid motif on hyphal surfaces of Candida albicans. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6298–6305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stoldt V R, Sonneborn A, Leuker C E, Ernst J. Efg1p, an essential regulator of morphogenesis of the human pathogen Candida albicans, is a member of a conserved class of bHLH proteins regulating morphogenetic processes in fungi. EMBO J. 1997;16:1982. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Helden J, André B, Collado-Vides J. A web site for the computational analysis of yeast regulatory sequences. Yeast. 2000;16:177–187. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(20000130)16:2<177::AID-YEA516>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]