Abstract

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ (PI3Kγ) is a shared downstream component of chemokine-mediated signaling pathways and regulates migration, proliferation and activation of inflammatory cells. PI3Kγ has been shown to play a crucial role in regulating inflammatory responses during the progression of several diseases. We investigated the potential function of PI3Kγ in mediating inflammatory reactions and the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a model of multiple sclerosis (MS). We found that systemic treatment with selective PI3Kγ inhibitor AS-604850 significantly reduced the number of infiltrated leukocytes in the CNS and ameliorated the clinical symptoms of EAE mice. Treatment with this PI3Kγ inhibitor enhanced myelination and axon number in the spinal cord of EAE mice. Consistently, we demonstrated that PI3Kγ deletion in knockout mice mitigates the clinical sign of EAE compared to PI3Kγ+/+ controls. PI3Kγ deletion increased the number of axons in the lumbar spinal cord, including descending 5-HT-positive serotonergic fiber tracts. Our results indicate that PI3Kγ contributes to development of autoimmune CNS inflammation and that PI3Kγ blockade may provide a great potential for treating patients with MS.

Keywords: EAE, multiple sclerosis, PI3 kinase γ, functional recovery, axon, myelination

INTRODUCTION

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory disease and is characterized by myelin and axonal damage in the brain and spinal cord. The intensive attack of immune cells and generation of various cytokines induce myelin and axonal damage in the CNS (Friese et al., 2006; Hauser and Oksenberg, 2006). Particularly, myelin-specific T cells are activated in the peripheral lymphoid organs, cross the blood–brain barrier and penetrate into the CNS (Merrill and Benveniste, 1996; Martino and Hartung, 1999). T cells that access into the CNS initiate and coordinate the immune attack directed against the myelin sheath by recruiting other inflammatory cells from the immune system outside the CNS, including activated macrophages and microglia. Transmigration of activated B lymphocytes and plasma cells contributes to subsequent damage process by generating antibodies against myelin structures. A featured pathologic change in MS is the formation of multiple demyelinated plaques scattered in the CNS, particularly in the white matter areas (Friese et al., 2006; Hauser and Oksenberg, 2006). The accumulated myelin and axonal loss results in signal conduction failure along axons and neurological deficits in patients. Although most MS patients develop as a relapsing–remitting disease with partial or complete recovery in the early stage, recurrent inflammation over time leads to severe CNS damage and persistent neurological impairment.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks), a family of lipid signaling kinases, phosphorylate phosphoinositides at the 3 position of inositol ring and form phosphorylated inositol lipid. PI3Ks are divided into classes I, II and III according to their molecular structure, cellular regulation and in vivo substrate specificities. Class IA (α, β and δ isoforms) and class IB (γ isoform) are a family of dual-functional lipid and protein kinases. This class of enzymes generate second messenger phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3) by phosphorylating phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PI(4,5)P2). Following stimulation of GTP-binding protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), cellular levels of PI(3,4,5)P3 increase substantially and transiently, which controls many cellular functions, including growth, proliferation, survival, adhesion and migration. PI3Kα and β are almost ubiquitously expressed and regulate functions of a variety of cells. In contrast, PI3Kγ and δ are mainly expressed by white blood cells, including granulocytes, monocytes and macrophages, and are important for coordinating body responses to inflammatory stimulations. In particular, γ isoform plays a central role in chemokine-induced recruitment of leukocytes (Sasaki et al., 2000). PI3Kγ activation in neutrophils by chemoattractants on the surface of inflamed endothelium regulates adhesion and migration of neutrophils, release of cytokines, secretion of proteases, and the generation of reactive oxygen species and other antimicrobial products. PI3Kγ also regulates the function of other immune cells, including chemotaxis of monocytes or macrophages to inflammation sites, homing of dendritic cells to lymph nodes, and development and activation of T lymphocytes (Laffargue et al., 2002; Del Prete et al., 2004; Medina-Tato et al., 2007). PI3Kγ deletion in transgenic mice exhibits impaired neutrophil and macrophage migration, mast cell degranulation and some defects in thymocyte development (Del Prete et al., 2004). Therefore, PI3Kγ is a critical intracellular signal in regulating leukocyte functions and initiating a wide range of inflammatory processes following the activation of membrane GPCRs.

Given the essential role of PI3Kγ in regulating proliferation, activation and migration of various leukocytes, PI3Kγ stimulation may contribute to inflammatory responses in many disorders. Indeed, PI3Kγ plays a role in the activation of macrophages, generation of atherogenic cytokine and angiotensin-II in vitro in response to oxidized low-density lipoprotein, and the induction of atherosclerotic lesions in hyper-cholesterolemic mice in vivo (Chang et al., 2007). PI3Kγ contributes to joint inflammation and damage in the mouse model of rheumatoid arthritis because PI3Kγ knockout (KO) mice are resistant to collagen-II-specific antibody-induced arthritis (Camps et al., 2005). PI3Kγ also contributes to the pathogenesis of a number of other inflammatory disorders (Barber et al., 2005; Camps et al., 2005; Ruckle et al., 2006; Hayer et al., 2009). Thus, PI3Kγ may become an important therapeutic target for numerous inflammatory disorders.

Recent investigation of thiazolidinedione derivatives has led to the identification of isoform-specific inhibitors with high-binding capacity only for PI3Kγ (Camps et al., 2005). For example, AS605240, an ATP-competitive inhibitor of PI3Kγ, has 30-fold higher potency against PI3Kγ (Ki = ~8 nM) than against other PI3K isoforms (Camps et al., 2005). By using PI3Kγ inhibitors, a group demonstrated the remarkable role for this isoform in generating CD4 T cell memory (Barber et al., 2005), which is essential for inducing most autoimmune diseases (Lovett-Racke et al., 1998; Krakauer et al., 2006). AS605240 blocked glomerulonephritis of systemic lupus erythematosus and joint inflammation of rheumatoid arthritis in mouse models (Barber et al., 2005; Camps et al., 2005). In this project, we demonstrated significant protective effects of PI3Kγ suppression with pharmacological inhibitor AS-604850 in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mice, including reduced numbers of macrophages and lymphocytes in the CNS, increased myelination and axonal numbers in the spinal cord and decreased EAE clinical symptoms. Moreover, we demonstrated transgenic PI3Kγ deletion alleviated clinical symptoms of EAE and increased axonal numbers in the spinal cord of EAE mice, including descending serotonergic axons. Therefore, PI3Kγ repression may facilitate the development of an effective treatment for numerous inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, including MS.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

EAE induction, clinical score evaluation and drug treatment

C57BL6 mice or PI3Kγ KO mice with C57BL6J background were induced by subcutaneous injection of 200 μl of emulsion containing 200 μg of 35–55 myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) peptide in complete Freund’s adjuvant with 200 μg of H37Ra Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Bordetella pertussis toxin (50 ng) was injected intraperitoneally on the same day after MOG peptide injection and 48 h thereafter. Following immunization, animals were evaluated for clinical EAE scores with the following criteria: 0, no detectable sign of EAE; 1, weakness of the tail; 2, definite tail paralysis and hind limb weakness; 3, partial paralysis of the hind limbs; 4, complete paralysis of the hind limbs; 5, complete paralysis of the hind limbs with incontinence and partial or complete paralysis of forelimbs. During the clinical score evaluations, the examiner was unaware of the drug treatment or genotypes of transgenic mice.

In this project, we performed four batches of mouse experiments with MOG peptide immunization. (1) One day after EAE onset (score ⩾ 1), C57BL6 mice received systemic delivery of vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or AS-604850 (7.5 mg/kg/day) via daily subcutaneous injections for seven consecutive days. These mice were perfused 8 days after EAE onset (for leukocyte infiltration in the CNS, n = 5 mice per group) or perfused 28 days after EAE onset (for clinical EAE score evaluation, n = 6 mice per group). (2) To confirm the role of AS-604850 in alleviating EAE symptoms, we performed the second set of EAE mice and subcutaneously delivered DMSO or AS-604850 (7.5 mg/kg/day) for 14 continuous days starting one day after EAE onset (n = 9 and 8 mice in control and AS-604850 groups). These mice were perfused for histology and axon and myelination quantification 24 days after EAE onset. (3) To study the function of PI3Kγ for regulating EAE formation with a genetic approach, we immunized 3 groups of PI3Kγ mutant mice ( +/+, +/− or −/−) with MOG peptide as above and the clinical EAE scores were evaluated for 23 days (n = 12 mice per group). (4) To confirm reduced EAE scores in PI3Kγ deficient mice, we performed the other set of PI3K KO mice and examined serotonergic axons in the spinal cord 35 days after EAE onset (n = 10 and 9 mice in PI3Kγ+/+ and −/− groups). All the protocols for animal research were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Histology

Animals were perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde at the indicated times above and the spinal cord and brain were dissected out. Fixed spinal cord segments were removed and immersion-fixed in the same fixative for 1 day at 4 °C and incubated overnight in 30% sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Transverse frozen sections (30 μm) were cut and collected in wells containing PBS. After rinsing with PBS for 3 times, sections were incubated overnight with antibodies against myelin basic protein (MBP, 1:1000, SMI 99 mouse monoclonal, Covance), neurofilament (1:400, rabbit NF 200, Sigma) and 5-HT (1:4000, rabbit, Immunostar) diluted in TBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 4% normal goat serum. Following overnight incubation at 4 °C, sections were incubated with secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa488 or Alexa594 (1:200; Invitrogen) (Xing et al., 2011). Myelination of the spinal cord was confirmed by Luxol fast blue (LFB) staining, which labels myelin sheath structures (Xing et al., 2011). For LFB staining, transverse sections were dehydrated in a gradient of ethanol and stained in 0.1% solvent blue 38 (Sigma) in acidified 95% ethanol overnight at 60 °C. After rinsing with 95% ethanol and distilled water, sections were differentiated with 0.05% Li2CO3 and ethanol several times until the contrast between the gray matter and white matter was clearly detected (Mi et al., 2007; Xing et al., 2011). Some of these sections were also counterstained by Cresyl Violet.

Myelin and axon quantification

For MBP-labeled myelin and NF-stained axon quantification, images were captured with a Nikon digital image-collecting system from multiple spinal cord sections. The measured fields (250 × 360 μm) in three different white matter areas including dorsal, lateral and ventral columns were randomly selected in each section. The intensity of myelin and axonal signals in selected fields was analyzed automatically with ImageJ software (Xing et al., 2011). In brief, after inversion of the loaded images and conversion of them into binary number, the levels of threshold were adjusted until clear myelin circles and axon dots were achieved. Myelin and axonal number was automatically calculated as a ratio of myelin or axon signals to the measured areas. The average of eight random sections was collected at a given level of the spinal cord in each animal. To determine serotonergic fibers in the spinal cord, individual fibers stained by a 5-HT antibody in the ventral and dorsal half of the spinal cord at cervical 5 and lumbar 4 levels were traced manually as we reported previously (Fu et al., 2007; Dill et al., 2008; Fisher et al., 2011). The mean density of 5-HT fibers was measured from three random transverse sections in each mouse using ImageJ and Photoshop software. During histological processing and myelin measurements, the researchers were unaware of drug treatments or animal genotypes in EAE mice.

Statistical analysis

Prism Software was used for statistical analyses. The behavioral data evaluated at multiple time points (Figs. 2 and 5) were analyzed with a repeated-measures two-way ANOVA and p values are provided in the figures. The morphologic data collected at one time point were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests (Fig. 3) or with Student’s t-test (Figs. 1 and 6, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01). The data in all the graphs are means ± SEM and the differences with p < 0.05 were considered significant between different groups.

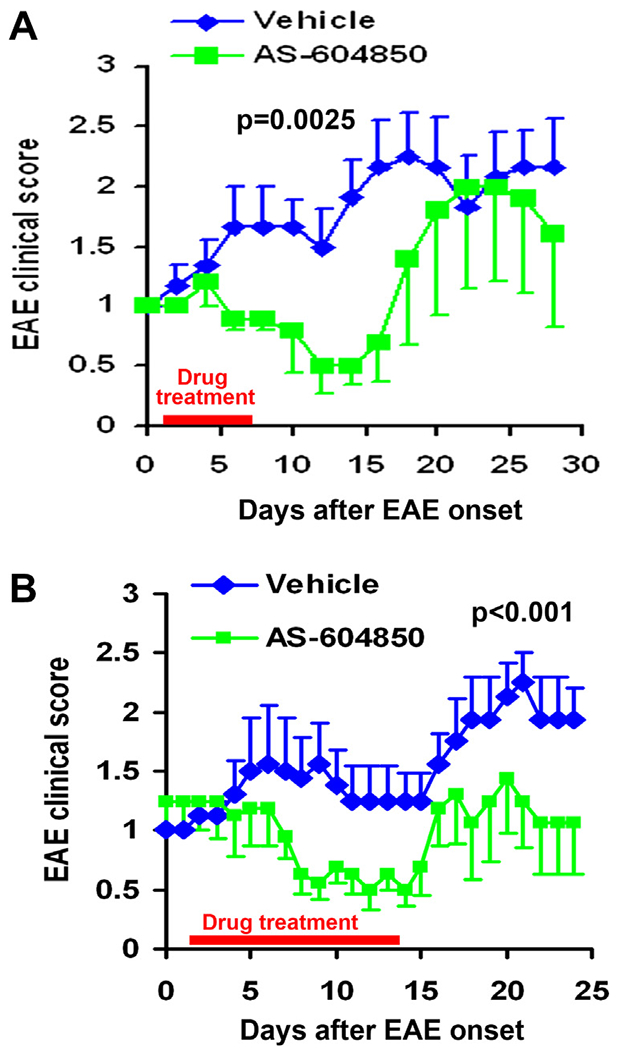

Fig. 2.

Treatment with selective PIK3γ inhibitor AS-604850 attenuates clinical symptoms of EAE mice. Graphs indicate clinical EAE scores as the function of time after EAE onset. Treatments with vehicle DMSO or AS-604850 (7.5 mg/kg/day) were initiated one day after EAE onset and sustained for 7 days (A) or for 14 days (B). AS-604850 treatment significantly reduced EAE scores at multiple time points. The bar in red indicates the time period for drug application in these EAE mice. n = 6 mice in each group in A; n = 9 and 8 mice in DMSO and AS-604850 groups in B. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

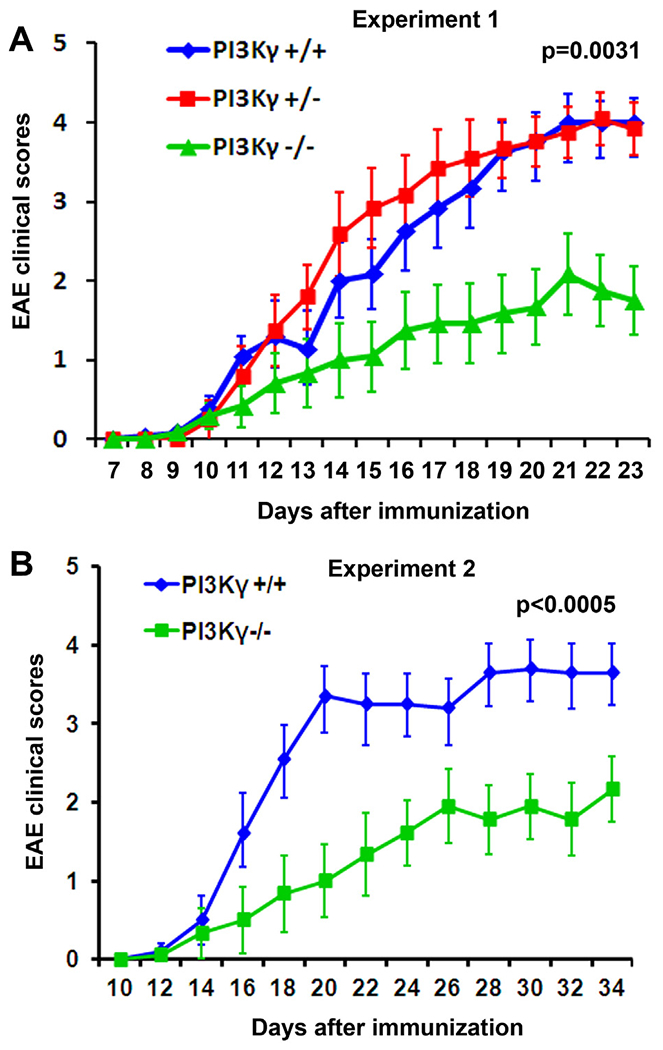

Fig. 5.

PIK3γ deletion in knockout mice reduces clinical EAE symptoms. Graphs indicate clinical EAE scores as the function of time. PIK3γ−/− mice exhibit significantly reduced EAE scores at multiple time points compared to either PIK3γ+/+ or +/− control groups. n = 12 mice in each group in A; n =10 and 9 mice in PIK3γ+/+ and −/− groups in B.

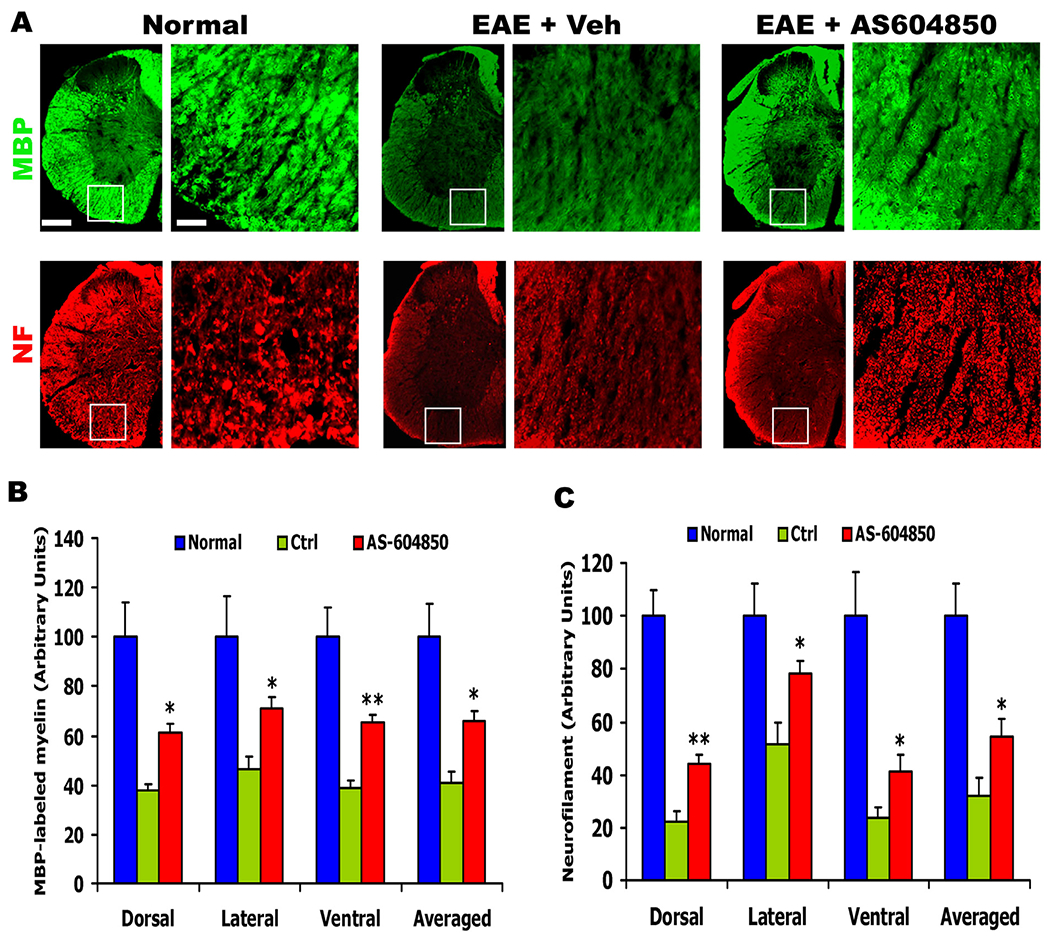

Fig. 3.

AS-604850 treatment enhances myelination and axon number in the lumbar spinal cord 25 days after EAE onset. (A) The representative images indicate transverse sections of the spinal cord immunostained for MBP (top images) and NF (bottom images) in normal, EAE + Veh and EAE + AS-604850 groups. In all the sections, dorsal is up. Scale = 150 (low power) or 30 (high power) μm. (B, C) The myelin signals stained by MBP and axonal signals labeled by NF were quantified from different white matter areas of transverse sections in a blind manner. n = 6 mice in each group.

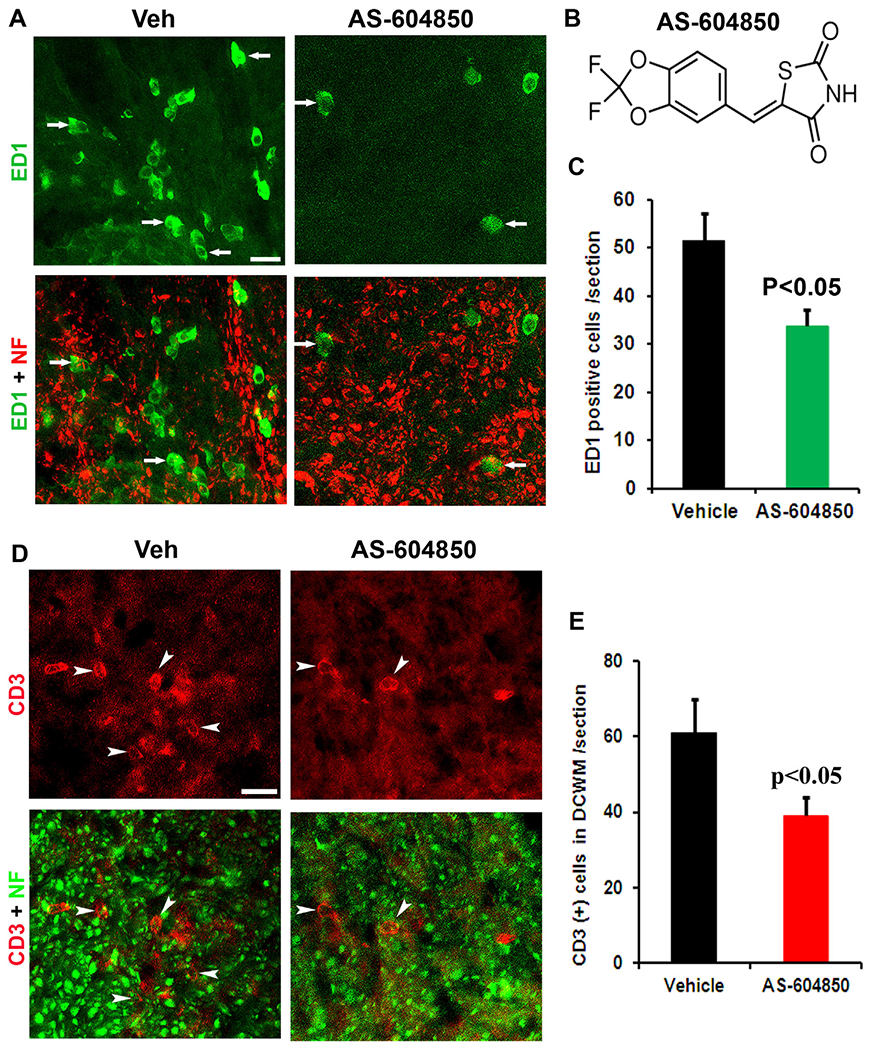

Fig. 1.

Systemic treatment with AS-604850 attenuated ED1+ macrophages and CD3+ lymphocytes in lumbar spinal cords of EAE mice. (A) The representative transverse spinal cord sections doubly stained for ED1 (green) and neurofilament (NF, red) display a number of ED1+ macrophages (arrows) in lateral white matter tracts in EAE mouse treated with vehicle DMSO. The similar sections reveal a reduced density of ED1+ macrophages in the same area of spinal cord from the EAE mice treated with AS-604850. Scale = 15 μm. (B) The schematic of molecular formula of AS-604850. (C) Quantification of ED1+ macrophages from each transverse section indicates significantly reduced number of ED1+ cells in the AS-604850-treated mice. (D) The representative transverse spinal cord sections doubly stained for CD3 (red) and NF (green) exhibit a number of CD3+ cells (arrowheads) in the dorsal column of lumbar spinal cord in EAE mouse treated with vehicle DMSO, but sections from AS-604850-treated EAE mice reveal a reduced density of CD3+ cells in the same area of spinal cord. Scale = 15 μm. (E) Quantification of CD3+ cells indicates significantly reduced number of CD3+ cells in AS-604850-treated mice. n = 5 mice in vehicle and AS-604850 groups. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

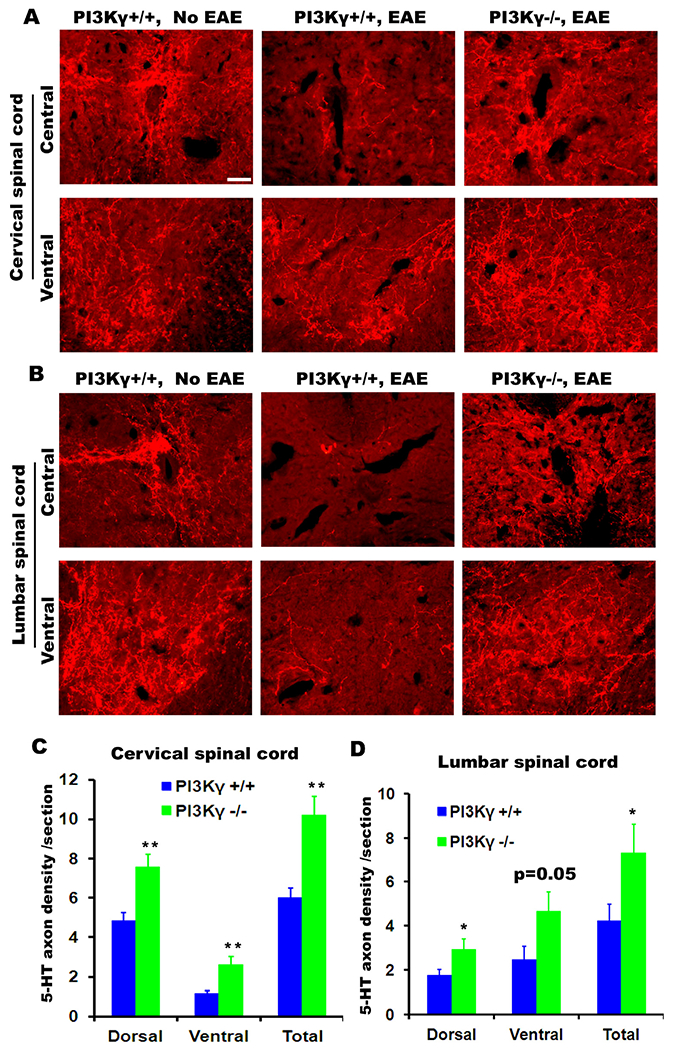

Fig. 6.

PIK3γ deletion enhances serotonergic fibers in the cervical and lumbar spinal cord of EAE mice. (A, B) Transverse sections of the central and ventral spinal cord at C5 (A) and L4 (B) levels reveal high density of serotonergic fibers in normal control mice (left column). Transverse sections of the spinal cord in control EAE mice (PIK3γ+/+) displayed highly-reduced 5-HT fibers 5 weeks after EAE onset (center column), but sections from PIK3γ−/− mice (right column) exhibited increased serotonergic fibers in both central and ventral part of the spinal cord compared to those in vehicle-treated EAE mice. The dorsal is up in all these sections. Scale = 50 μm. (C, D) Serotonergic fiber length was measured from gray and white matter in dorso-central areas and from gray matter in the ventral horn of the spinal cord at C5 (C) or L4 (D). PIK3γ−/− group shows a greater number of 5-HT positive axons in the cervical and lumbar spinal cord. n = 10 and 9 mice in C and D.

RESULTS

Systemic treatment with AS-604850 attenuated invasion of macrophages into the CNS in EAE mice

Considering crucial function of PI3Kγ in regulating inflammatory and immune reactions under several pathologic conditions (Barber et al., 2005; Camps et al., 2005; Donahue et al., 2007), we evaluated repression of this kinase with a small compound AS604850 on immune response in the CNS of EAE mice. AS-604850 is a selective and ATP-competitive inhibitor of PI3Kγ with an IC50 value of 0.25 μm for γ isoform (Camps et al., 2005). Previously, PI3Kγ selective inhibitors, including AS-604850, have been applied to mice orally at 10–30 mg/kg (Camps et al., 2005; Rodrigues et al., 2010; Kobayashi et al., 2011; Comerford et al., 2012). To evaluate in vivo dose of a PI3Kγ inhibitor more precisely, we first performed a dose-curve response by injecting AS-604850 into EAE mice subcutaneously at 7.5, 15 and 30 mg/kg/day. Surprisingly, all the EAE mice were unable to tolerate the two higher doses of AS-604850 and died 1–3 days after starting treatment. However, all the EAE mice treated at 7.5 mg/kg/day survived well and did not exhibit any signs of side effects. We therefore employed AS-604850 at 7.5 mg/kg/day for all the experiments in this project and evaluated its effects on leukocyte infiltration and EAE recovery. The different tolerance to AS-604850 between this study and previous reports probably attributes to drug application approaches because the drug absorption rate after subcutaneous injection should be greater than that of oral application.

To study the role of PI3Kγ for regulating leukocyte access to CNS, we delivered vehicle DMSO or AS-604850 (7.5 mg/kg/day) for seven consecutive days starting one day after EAE onset. Active C57BL/6 EAE mice were induced by subcutaneous injections of an emulsion containing autoantigen MOG peptide (MOG35–55) in complete Freund’s adjuvant. Similar to previous reports (Stromnes and Goverman, 2006), mice subjected to this procedure developed a typical course of neurological disability 12–14 days after immunization and the symptoms persisted for at least 5 weeks. We evaluated the effect of PI3Kγ inhibitor on macrophage invasion into the CNS in transverse sections of the spinal cord at L4 level by immunostaining ED1, a marker for activated macrophages and microglia. Genetic deletion of PI3Kγ in transgenic mice has been reported to abolish the activation of macrophages mediated by receptors for IgG-Fc (Camps et al., 2005; Konrad et al., 2008). Spinal cord sections in control EAE mice exhibited a number of ED1-positive cells in both white and gray matter areas. Although ED1-positive cells were widely distributed in the spinal cord, a higher density was detected along axonal tracts in the white matter (Fig. 1A, C). In contrast, sections from AS-604850-treated EAE mice exhibited a lower density of ED1 + cells. Thus, pharmacological PI3Kγ suppression with selective inhibitor suppresses the infiltration of macrophages into the CNS during EAE development.

PI3Kγ inhibitor AS-604850 reduced CD3-positive lymphocytes in the spinal cords of EAE mice

We next examined the invasion of lymphocytes into the CNS by doubly staining for CD3, a marker for T cells, and for neurofilament, a marker for axon cylinders. Although CD3+ cells were detected in both gray and white matter areas in transverse sections of vehicle-treated mice, they are also largely distributed to various axonal tracts in the white matter. However, sections from AS-604850-treated mice displayed significantly reduced density of CD3-positive cells (Fig. 1D, E). For example, we detected ~61 CD3+ cells in the dorsal column white matter per transverse section in control mice versus ~39 CD3+ cells in AS-604850-treated mice. Thus, PI3Kγ suppression with selective pharmacological compound attenuates the invasion of lymphocytes into the CNS at the early stage of MS genesis.

Subcutaneous injections of selective PI3Kγ inhibitor attenuate clinical severity in EAE mice

PI3Kγ plays a remarkably role in regulating the migration of leukocytes in response to chemokines and other chemoattractants, and its inhibition is protective in several inflammatory disease models (Sasaki et al., 2000; Ward, 2004; Barber et al., 2005; Camps et al., 2005). To test potential beneficial effects of PI3Kγ suppression on EAE recovery, we evaluated the clinical symptoms in MOG35–55-immunized C57BL/6 EAE mice treated with daily subcutaneous injections of DMSO or AS-604850 (7.5 mg/kg/day) starting one day after EAE onset. Vehicle-treated mice showed a typical course of EAE symptoms that appeared ~14 days after MOG peptide immunization and their clinical symptoms reached the first peak around 6–9 days after the onset and the declined to some degree (Fig. 2A). The scores reached a second peak level around 17–20 days after onset. However, EAE mice treated with AS-604850 started to exhibit significantly lower EAE scores 5 days after beginning drug delivery and the reduced EAE scores persisted for ~12 days, including 10 days after drug termination. This finding suggests that PI3Kγ suppression with a selective inhibitor significantly attenuated clinical symptoms of EAE mice.

The experiment shown in Fig. 2A indicates suppressed EAE symptoms in AS-604850-treated mice, but the clinical scores gradually returned to control levels ~10 days after drug termination. To confirm this finding and further evaluate the effect of a longer period of PI3Kγ inhibition on recovery of EAE mice, we conducted another set of experiments by injecting drugs for 14 days starting 1 day after EAE onset. Consistently, we observed the remarkably reduced EAE scores 5 days after starting AS-604850 application and the attenuated EAE scores were maintained during two weeks of drug treatment (Fig. 2B). Although we detected a slight trend of EAE score elevation during the first two days after drug termination (approximately the starting time for the second EAE score peak in control mice), AS-604850-treated EAE mice displayed significantly reduced symptoms 10 days after drug termination. These findings support the alleviation of EAE symptoms after PI3Kγ inhibitor treatment and the essential role of this kinase in EAE pathogenesis.

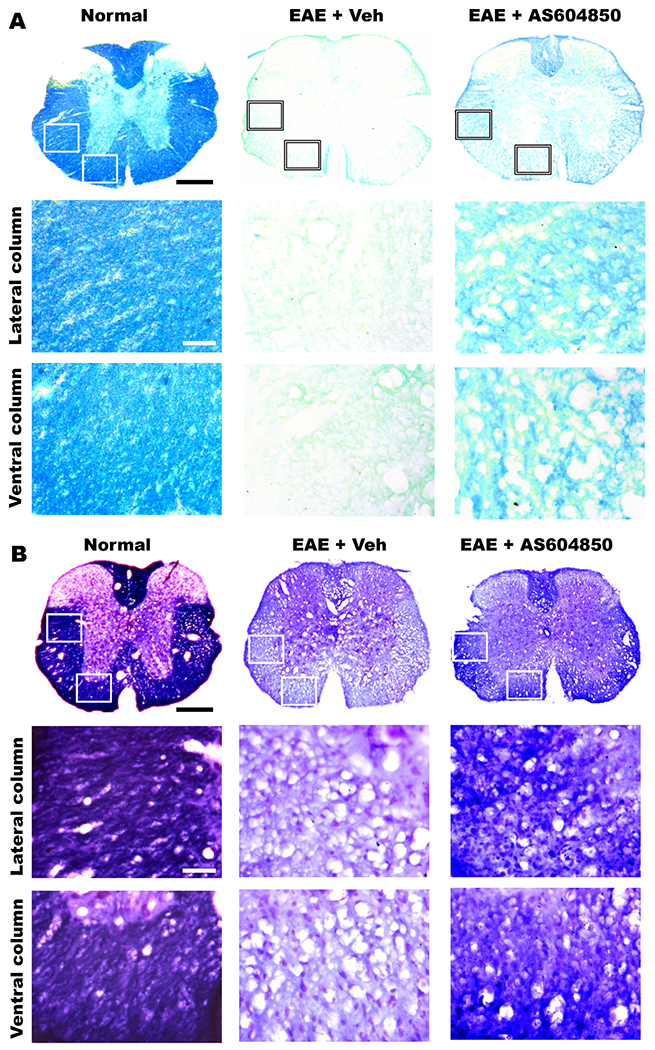

Systemic treatment with AS-604850 increased myelination and axonal number in the spinal cord of EAE mice

AS-604850 treatment attenuated leukocyte infiltration and clinical EAE symptoms, suggesting the protective effects of PI3Kγ inhibition to CNS tissue. We next determined whether AS-604850 treatment enhanced myelination and axon number in the spinal cord around 24 days after EAE onset by immunostaining MBP and neurofilament or by detecting myelin sheath with LFB staining. Compared to normal control mice, vehicle-treated EAE mice exhibited remarkably reduced myelin and axonal structures in the spinal cord, especially at the lumbar level (Fig. 3A and 4). Consistently, numerous groups reported obvious myelin and axonal loss along the white matter tracts in EAE mice (McGavern et al., 2000; Mi et al., 2007). Nevertheless, EAE mice treated with AS-604850 displayed significantly increased MBP, LFB and NF-staining signals at different white matter areas of the spinal cord (Fig. 3A–C and 4). Therefore, systemic treatment with PI3Kγ inhibitor reduced demyelination and axonal loss in EAE mice.

Fig. 4.

AS-604850 treatment increases myelination in the spinal cord of EAE mice detected by LFB staining. Images indicate representative transverse sections of the lumbar spinal cord processed for LFB staining (A) or LFB + Cresyl Violet counterstaining (B) in normal, EAE + vehicle and EAE + AS-604850 groups. The images at higher power were collected from lateral (middle) or ventral (bottom) white matter areas. In all the sections, dorsal is up. Scale bars = 350 μm (low magnification) and 50 μm (high magnification).

Transgenic PI3Kγ deletion reduced the severity of EAE in KO mice

To confirm the role of PI3Kγ in regulating EAE genesis, we immunized PI3Kγ KO mice with MOG peptide as above. All the three groups of mice (+/+, +/− and −/−) started to have clinical signs of EAE disease 10–12 days post-immunization (Fig. 5A). Although the onset of clinical symptoms in PI3Kγ−/− mice was not obviously delayed compared to two groups of control (+/+ and +/−) mice, the disease severity was significantly lower in PI3Kγ−/− mice around 18 days after immunization (~7 days after EAE onset). To confirm this finding, we performed the second set of experiments and detected continuingly attenuated EAE scores in PI3Kγ−/− mice (Fig. 5B) even 5 weeks after immunization. Thus, our further experiments using the transgenic approach validate the important role of PI3Kγ for mediating EAE genesis.

PI3Kγ deletion increased the number of descending serotonergic fibers in EAE mice

Given a significant role of PI3Kγ for mediating EAE pathogenesis, deletion of this kinase should also reduce myelin damage and axonal loss. A few descending spinal cord axonal pathways contribute to the extent of behavioral recovery in rodents, including the raphespinal fiber tracts (Li et al., 2004). We then characterized serotonergic fibers from transverse sections of EAE mice 35 days after EAE onset by immunostaining 5-HT. In normal control mice, a very high density of 5-HT fibers were detected in transverse sections of the spinal cord, particularly in the ventral horns as well as in the central and intermediolateral areas (Fig. 6A, B). Five weeks after EAE onset, the density of 5-HT-positive fibers was dramatically reduced in the spinal cord at either cervical or lumbar level compared to sections in normal control mice. Nevertheless, PI3Kγ−/− mice displayed significantly increased the density of 5-HT fibers in the spinal cord at both cervical and lumbar levels (Fig. 6A–D). Moreover, longitudinal sections of the spinal cord also displayed projection of a greater number of 5-HT-labeled axons in PI3Kγ−/− EAE mice (not shown). These results indicate that PI3Kγ deficiency preserved more axons in the spinal cord, including serotonergic fibers.

DISCUSSION

Principally expressed in leukocytes, PI3Kγ plays a central role in controlling proliferation and migration of leukocytes, including neutrophils, macrophages, mast cells and lymphocytes (Laffargue et al., 2002; Del Prete et al., 2004; Medina-Tato et al., 2007). Since PI3Kγ is a shared downstream signal for most chemokine-mediated pathways, it may represent an appropriate target for interfering with excessive leukocyte activation and migration in chronic inflammatory diseases. In support of this, PI3Kγ deletion in transgenic mice or suppression with pharmacological inhibitors is highly protective to different mouse models characterized by inflammatory and autoimmune reactions outside the CNS (Barber et al., 2005; Camps et al., 2005). These studies suggest that PI3Kγ inhibition prevents leukocyte recruitment, mast cell activation and other processes during initiation and progression of chronic inflammation. Given that adhesion, migration and invasion of inflammatory cells, particularly T cells, play a central role in the pathogenesis of MS, PI3Kγ activation may considerably contribute to inflammatory responses of MS and neural damage in the CNS. In this project, we demonstrate that selective PI3Kγ inhibitor AS-604850 significantly reduces the number of infiltrated leukocytes in the CNS of EAE mice and ameliorates clinical symptoms of EAE. Consistently, PI3Kγ deletion in KO mice mitigates clinical signs of EAE and increases the number of descending axons in the spinal cord, including serotonergic fiber tracts. PI3Kγ deficiency has also been shown to improve function by attenuating EAE clinical outcome (Fig. 4) (Rodrigues et al., 2010; Berod et al., 2011; Comerford et al., 2012). This study, together with other reports, supports the essential role of PI3Kγ in mediating MS pathogensis.

By employing PI3Kγ KO mice, we found that PI3Kγ−/− deletion significantly reduced clinical EAE scores compared to either PI3Kγ+/+ or +/− controls, although it did not delay the onset time of EAE. Consistently, two groups reported reduced EAE scores in PI3Kγ−/− mice (Berod et al., 2011; Comerford et al., 2012). In contrast, Rodrigues DH et al. reported remarkably delayed EAE onset compared to EAE controls (Rodrigues et al., 2010). The reasons for different effects of PI3Kγ deletion on EAE onset are not clear. Because all these studies employed PI3Kγ KO mice with C57BL/6 background, the genetic background was unlikely to cause the differences. However, these PI3Kγ mutant mice were generated by using different gene targeting approaches (Hirsch et al., 2000; Li et al., 2000; Sasaki et al., 2000), which might contribute to the diverse results among three studies (Rodrigues et al., 2010; Berod et al., 2011; Comerford et al., 2012). Together, these independent studies using the EAE model support the primary role of PI3Kγ in EAE formation.

Suppression of immune response in the peripheral lymphoid organs and subsequent infiltration of leukocytes into the CNS is probably the basis for alleviation of EAE clinical symptoms following PI3Kγ inhibition. PI3Kγ deletion delayed immune response in the spleen and draining lymph nodes by reducing cell number, cytokine production and antigen-specific lymphocyte proliferation 1–2 weeks after MOG peptide immunization (Berod et al., 2011). PI3Kγ absence attenuated CD4+ T cell immune priming, which is essential for EAE genesis. PI3Kγ−/− CD4+ T cells had reduced capacity of proliferation, decreased expression of activation marker proteins (CD69, CD44 and CD86) and inflammatory chemokine receptors CCR6 and CXCR3, and increased expression of chemokine receptor CCR7. PI3Kγ deletion also reduced interferon-γ-producing Th1 and interleukin (IL)-17A-producing Th17 cells in lymph nodes and spleen. Consequently, PI3Kγ deletion or inhibition suppressed infiltration of pathogenic leukocytes into the CNS following EAE immunization, including reduced invasion of CD4+/CD3+/CD8+ T cells, B cells, macrophages, neutrophils, Th17 cells and Th1 cells in the spinal cord. AS-604850 treatment significantly decreased the number of macrophages and CD3+ T cells in the spinal cord 8 days after EAE onset (Fig. 1). Increased T cell apoptosis due to PI3Kγ suppression may contribute to the reduction of cytokine-producing T cells in the CNS of EAE mice (Comerford et al., 2012).

As the shared downstream signaling for many chemokine-mediated pathways, PI3Kγ represents an appropriate target for interfering with excessive leukocyte activation and migration in chronic inflammatory diseases. Modulation of PI3Kγ activity may become a valid therapeutic approach for inflammation-mediated diseases. PI3Kγ deletion and inhibition are highly protective to different mouse models characterized by inflammatory and autoimmune reactions (Barber et al., 2005; Camps et al., 2005), including EAE model (Figs. 1–5). PI3Kγ inhibition efficiently prevents leukocyte recruitment, mast cell activation and other processes during EAE initiation and progression (Rodrigues et al., 2010; Berod et al., 2011; Comerford et al., 2012), suggesting its important function on inflammatory responses and neural damage during MS formation. Notably, systemic treatment with selective PI3Kγ inhibitor AS-604850 significantly reduces leukocyte infiltration in the CNS and ameliorates clinical symptoms of EAE (Figs. 1, 2 and 5). Although three recent studies have linked PI3Kγ deficiency/inhibition to EAE models, all of these reports were focused on the role of this kinase for regulating functions of different types of leukocytes (Rodrigues et al., 2010; Berod et al., 2011; Comerford et al., 2012). By contrast, the present study is centered on alterations of myelin and axonal structures in the spinal cord of EAE mice, in addition to showing consistent behavioral changes. For the first time, we reported detailed quantification data on enhanced myelination and axonal number in different locations of the spinal cord and novel information on the preservation of serotonergic fibers following transgenic or pharmacological PI3Kγ inhibition. Thus, this study, together with other recent reports, is important not only for understanding the molecular and cellular mechanism of MS formation, but for facilitating the development of a novel therapy for MS patients by targeting PI3Kγ.

Acknowledgments—

We thank Rashad Hussain, Hai Hiep Hoang and Sherry Rovinsky for technical support. This work was supported by research grants to S.L. from NIH (1R21NS066114), Shriners Hospitals for Children (SHC-250615) and Christopher & Dana Reeve Foundation (LA1-1002-2).

Abbreviations:

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- GPCR

GTP-binding protein-coupled receptor

- KO

knockout

- LFB

Luxol fast blue

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NF

neurofilament

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PI(3 4 5)P3

phosphatidylinositol-3 4 5-trisphosphate

- PI(4 5)P2

phosphatidylinositol-4 5-bisphosphate

- PI3Kγ

phosphoinositide 3-kinase γ

REFERENCES

- Barber DF, Bartolome A, Hernandez C, Flores JM, Redondo C, Fernandez-Arias C, Camps M, Ruckle T, Schwarz MK, Rodriguez S, Martinez AC, Balomenos D, Rommel C, Carrera AC (2005) PI3Kgamma inhibition blocks glomerulonephritis and extends lifespan in a mouse model of systemic lupus. Nat Med 11:933–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berod L, Heinemann C, Heink S, Escher A, Stadelmann C, Drube S, Wetzker R, Norgauer J, Kamradt T (2011) PI3Kgamma deficiency delays the onset of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis and ameliorates its clinical outcome. Eur J Immunol 41:833–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps M, Ruckle T, Ji H, Ardissone V, Rintelen F, Shaw J, Ferrandi C, Chabert C, Gillieron C, Francon B, Martin T, Gretener D, Perrin D, Leroy D, Vitte PA, Hirsch E, Wymann MP, Cirillo R, Schwarz MK, Rommel C (2005) Blockade of PI3Kgamma suppresses joint inflammation and damage in mouse models of rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Med 11:936–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JD, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Schvartz E, Lichtenstein AH, Field SJ, Kennedy C, Madhavarapu S, Luo J, Wu D, Cantley LC (2007) Deletion of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase p110gamma gene attenuates murine atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:8077–8082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comerford I, Litchfield W, Kara E, McColl SR (2012) PI3Kgamma drives priming and survival of autoreactive CD4(+) T cells during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. PLoS One 7:e45095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete A, Vermi W, Dander E, Otero K, Barberis L, Luini W, Bernasconi S, Sironi M, Santoro A, Garlanda C, Facchetti F, Wymann MP, Vecchi A, Hirsch E, Mantovani A, Sozzani S (2004) Defective dendritic cell migration and activation of adaptive immunity in PI3Kgamma-deficient mice. EMBO J 23:3505–3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill J, Wang H, Zhou FQ, Li S (2008) Inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 promotes axonal growth and recovery in the CNS. J Neurosci 28:8914–8928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donahue AC, Kharas MG, Fruman DA (2007) Measuring phosphorylated Akt and other phosphoinositide 3-kinase-regulated phosphoproteins in primary lymphocytes. Methods Enzymol 434:131–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D, Xing B, Dill J, Li H, Hoang HH, Zhao Z, Yang XL, Bachoo R, Cannon S, Longo FM, Sheng M, Silver J, Li S (2011) Leukocyte common antigen-related phosphatase is a functional receptor for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan axon growth inhibitors. J Neurosci 31:14051–14066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friese MA, Montalban X, Willcox N, Bell JI, Martin R, Fugger L (2006) The value of animal models for drug development in multiple sclerosis. Brain 129:1940–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Hue J, Li S (2007) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs promote axon regeneration via RhoA inhibition. J Neurosci 27:4154–4164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser SL, Oksenberg JR (2006) The neurobiology of multiple sclerosis: genes, inflammation, and neurodegeneration. Neuron 52:61–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayer S, Pundt N, Peters MA, Wunrau C, Kuhnel I, Neugebauer K, Strietholt S, Zwerina J, Korb A, Penninger J, Joosten LA, Gay S, Ruckle T, Schett G, Pap T (2009) PI3Kgamma regulates cartilage damage in chronic inflammatory arthritis. FASEB J 23:4288–4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch E, Katanaev VL, Garlanda C, Azzolino O, Pirola L, Silengo L, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Altruda F, Wymann MP (2000) Central role for G protein-coupled phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma in inflammation. Science (New York, NY) 287:1049–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi N, Ueki K, Okazaki Y, Iwane A, Kubota N, Ohsugi M, Awazawa M, Kobayashi M, Sasako T, Kaneko K, Suzuki M, Nishikawa Y, Hara K, Yoshimura K, Koshima I, Goyama S, Murakami K, Sasaki J, Nagai R, Kurokawa M, Sasaki T, Kadowaki T (2011) Blockade of class IB phosphoinositide-3 kinase ameliorates obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:5753–5758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad S, Ali SR, Wiege K, Syed SN, Engling L, Piekorz RP, Hirsch E, Nurnberg B, Schmidt RE, Gessner JE (2008) Phosphoinositide 3-kinases gamma and delta, linkers of coordinate C5a receptor-Fcgamma receptor activation and immune complex-induced inflammation. J Biol Chem 283:33296–33303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer M, Sorensen PS, Sellebjerg F (2006) CD4(+) memory T cells with high CD26 surface expression are enriched for Th1 markers and correlate with clinical severity of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 181:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffargue M, Calvez R, Finan P, Trifilieff A, Barbier M, Altruda F, Hirsch E, Wymann MP (2002) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma is an essential amplifier of mast cell function. Immunity 16:441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Liu BP, Budel S, Li M, Ji B, Walus L, Li W, Jirik A, Rabacchi S, Choi E, Worley D, Sah DW, Pepinsky B, Lee D, Relton J, Strittmatter SM (2004) Blockade of Nogo-66, myelin-associated glycoprotein, and oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein by soluble Nogo-66 receptor promotes axonal sprouting and recovery after spinal injury. J Neurosci 24:10511–10520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Jiang H, Xie W, Zhang Z, Smrcka AV, Wu D (2000) Roles of PLC-beta2 and -beta3 and PI3Kgamma in chemoattractant-mediated signal transduction. Science (New York, NY) 287:1046–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovett-Racke AE, Trotter JL, Lauber J, Perrin PJ, June CH, Racke MK (1998) Decreased dependence of myelin basic protein-reactive T cells on CD28-mediated costimulation in multiple sclerosis patients. A marker of activated/memory T cells. J Clin Invest 101:725–730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino G, Hartung HP (1999) Immunopathogenesis of multiple sclerosis: the role of T cells. Curr Opin Neurol 12:309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGavern DB, Murray PD, Rivera-Quinones C, Schmelzer JD, Low PA, Rodriguez M (2000) Axonal loss results in spinal cord atrophy, electrophysiological abnormalities and neurological deficits following demyelination in a chronic inflammatory model of multiple sclerosis. Brain 123(Pt 3):519–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina-Tato DA, Ward SG, Watson ML (2007) Phosphoinositide 3-kinase signalling in lung disease: leucocytes and beyond. Immunology 121:448–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Benveniste EN (1996) Cytokines in inflammatory brain lesions: helpful and harmful. Trends Neurosci 19:331–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mi S, Hu B, Hahm K, Luo Y, Kam Hui ES, Yuan Q, Wong WM, Wang L, Su H, Chu TH, Guo J, Zhang W, So KF, Pepinsky B, Shao Z, Graff C, Garber E, Jung V, Wu EX, Wu W (2007) LINGO-1 antagonist promotes spinal cord remyelination and axonal integrity in MOG-induced experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med 13:1228–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues DH, Vilela MC, Barcelos LS, Pinho V, Teixeira MM, Teixeira AL (2010) Absence of PI3Kgamma leads to increased leukocyte apoptosis and diminished severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 222:90–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruckle T, Schwarz MK, Rommel C (2006) PI3Kgamma inhibition: towards an ‘aspirin of the 21st century’? Nat Rev Drug Discov 5:903–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Irie-Sasaki J, Jones RG, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Stanford WL, Bolon B, Wakeham A, Itie A, Bouchard D, Kozieradzki I, Joza N, Mak TW, Ohashi PS, Suzuki A, Penninger JM (2000) Function of PI3Kgamma in thymocyte development, T cell activation, and neutrophil migration. Science (New York, NY) 287:1040–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromnes IM, Goverman JM (2006) Active induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Nat Protoc 1:1810–1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SG (2004) Do phosphoinositide 3-kinases direct lymphocyte navigation? Trends Immunol 25:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing B, Li H, Wang H, Mukhopadhyay D, Fisher D, Gilpin CJ, Li S (2011) RhoA-inhibiting NSAIDs promote axonal myelination after spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 231:247–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]