Abstract

Aims

Increasing evidence for benefit of early detection of cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) coupled with limitations of current diagnostic investigations has led to interest and utilisation of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM). We conducted a systematic review to assess current evidence on CGM compared to reference standard oral glucose tolerance test for the detection of dysglycemia in people with cystic fibrosis without confirmed diabetes.

Methods

MEDLINE, Embase, CENTRAL, Evidence-Based Medicine Reviews, grey literature and six relevant journals were searched for studies published after year 2000. Studies reporting contemporaneous CGM metrics and oral glucose tolerance test results were included. Outcomes on oral glucose tolerance tests were categorised into a) normal, b) abnormal (indeterminate and impaired) or c) diabetic as defined by American Diabetes Association criteria. CGM outcomes were defined as hyperglycemia (≥1 peak sensor glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL), dysglycemia (≥1 peak sensor glucose ≥ 140–199 mg/dL) or normoglycemia (all sensor glucose peaks < 140 mg/dL). CGM hyperglycemia in people with normal or abnormal glucose tolerances was used to define an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes. The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies tool was used to assess risk of bias. Primary outcome was relative risk of an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes compared to the oral glucose tolerance test.

Results

We identified 1277 publications, of which 19 studies were eligible comprising total of 416 individuals with contemporaneous CGM and oral glucose tolerance test results. Relative risk of an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes compared to oral glucose tolerance test was 2.92. Studies analysed were highly heterogenous, prone to bias and inadequately assessed longitudinal associations between CGM and relevant disease-specific sequela.

Conclusions

A single reading > 200 mg/dL on CGM is not appropriate for the diagnosis of CFRD. Prospective studies correlating CGM metrics to disease-specific outcomes are needed to determine appropriate cut-points.

Keywords: Continuous glucose monitoring, Cystic fibrosis, Diabetes, Diagnosis

Introduction

Background

Cystic fibrosis is an inherited autosomal recessive condition with variable clinical phenotypes [1], [2] with respiratory failure the commonest cause of death [3], [4]. Advances in cystic fibrosis treatment have led to increased life expectancy and consequently rising prevalence of associated co-morbidities such as cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) [3], [4]. It is estimated CFRD may affect up to half of all people with cystic fibrosis (PwCF) [5]. The pathophysiology of CFRD is complex with insulin deficiency, insulin resistance and concomitant exocrine pancreatic dysfunction leading to progressive inflammation and fibrosis of the pancreas [6], [7]. Presence of CFRD has been linked to lower baseline lung function [8], faster rate of pulmonary decline [9], [10], increased risk of co-infection with Staphylococcal aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa [11], prolonged pulmonary exacerbations [12] and higher mortality [13] when compared to those without diabetes. Early diagnosis of CFRD can improve nutritional status [14], [15], lung function and mortality [5], [16].

Current diagnostic criteria and limitations

The American Diabetes Association recommends an annual oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) from 10 years of age as the gold standard screening test for CFRD. Diagnosis of CFRD is confirmed if fasting plasma glucose level is ≥ 126 mg/dL (≥7.0 mmol/L) and/or 2-hour plasma glucose level is ≥ 200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/L). Cut-points on the OGTT for diagnosis of CFRD are not related to adverse cystic fibrosis outcomes, rather based on glucose levels associated with microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes [17]. However, treatment has been shown to be beneficial using these criteria and it remains unclear whether more sensitive criteria are needed [18]. Secondly, in cystic fibrosis the OGTT may demonstrate distinct abnormalities. Fasting hyperglycemia is uncommon and collection of blood glucose levels at 30, 60 and 90 min time-points increases opportunities to capture glucose peaks ≥ 200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/L) defined as indeterminate glucose tolerance [19], [20] which has been linked to increased future risk of CFRD [19], [21], [22], [23] and inferior lung function [24]. Thirdly, OGTT results over time may transition across normal, impaired and diabetic and this bi-directional trajectory may be indiscriminate and unpredictable [21], [25]. Lastly, there is reportedly low uptake of the OGTT for screening of CFRD by eligible people [26]. A haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥ 48 mmol/mol (≥6.5 %) is currently not recommended as a screening tool for CFRD due to insufficient sensitivity because of the intermittent nature of hyperglycemia and higher red cell turnover in cystic fibrosis [18], [27], [28]. Lower cut-offs have been proposed but not validated in PwCF [29], [30].

Evidence for continuous glucose monitoring

Continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) first became available in the early 2000 s [31] and rapidly gained interest with advancements in performance. Predominantly used for people with type 1 diabetes, CGM provides real-time sensor glucose readings together with valuable trends and insights not attainable with routine finger-prick blood glucose level monitoring [32], [33]. Usually, CGM serves as a management decision-aid that optimises behavioural and pharmacological interventions with evidence that it improves glycemic control, hypoglycemic confidence and diabetes distress in people with type 1 diabetes [32], [34]. In PwCF, limitations of current diagnostic investigations for CFRD coupled with increasing need for early detection and treatment have led to demands for a more sensitive, accessible and user-friendly screening test. The ability of CGM to detect early glucose abnormalities (dysglycemia) [35] in PwCF, paired with less burdensome application than the OGTT given no requirements for fasting and ability to be performed outside the healthcare setting has led to its unconventional use as a diagnostic test [36]. Currently there are no international position statements on the use of CGM in PwCF, only a practical guide offering expert opinion [37] and a recent systematic review by our group comparing use of CGM to self-monitoring of blood glucose for the management of people with confirmed CFRD [38].

Objectives

The primary objective of this systematic review was to assess current evidence on CGM to detect hyperglycemia and dysglycemia in PwCF and compare it to the reference gold standard OGTT. Secondary objectives were to explore interrelationships between CGM and other reference tests and identify evidence gaps to help guide future research directions.

Research design and methods

Protocol design

Our protocol aligned with a previously published Cochrane systematic review protocol on the topic [39] and followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and meta-Analyses for Protocols (PRISMA-P) reporting guidelines [40] (See Supplement 1). All human studies utilising CGM in cystic fibrosis published after January 1, 2000 were identified. The search was carried out on March 19, 2020 and database alerts set up to identify new relevant studies given anticipated disruption due to the covid-19 pandemic. Online databases searched included MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register for Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), all evidence-based medicine reviews incorporating Cochrane database of systematic reviews, ACP journal club, Cochrane central register of controlled trials, Cochrane methodology register and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Search Portal. Grey literature searches were conducted using Google Scholar, Open Grey and British Library. Six journals (Diabetic Medicine, Diabetes, Diabetologia, Journal of Cystic Fibrosis, Paediatric Pulmonology and Paediatric Diabetes) were hand searched (last 5 years) to identify relevant conference abstracts from Diabetes UK abstracts, American Diabetes Association Scientific Session Abstracts, European Association of the Study of Diabetes Annual Meeting, European Cystic Fibrosis Society, Annual North American Cystic Fibrosis Conference and Annual Meeting of the International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes respectively. A concept map (Supplement 2; S1 & S2) were developed to search the online databases using MeSH terms and text words to maximise sensitivity: “cystic fibrosis” AND “continuous glucose monitoring” AND “diabetes”.

Selection criteria

Eligibility criteria were predefined and inclusion criteria comprised individuals with confirmed cystic fibrosis of all ages and genders who had used any CGM device for > 24 h with at least one reference standard test (OGTT, HbA1c or plasma/finger-prick blood glucose level) within 3 months of CGM use. There were no restrictions on study type. Studies published before the year 2000, not in English language and with unavailable or insufficient published quantitative data were excluded. See Supplementary Material S3 for more detail.

Data extraction

Search results were exported for storage to EndNote and transferred to Covidence for screening and data extraction. One reviewer (SK) completed title and abstract screening and two reviewers (SK, MP) independently reviewed all full text articles to be included in the study, with discrepancies resolved by a third investigator (HT).

Data collection

One reviewer (SK) independently extracted data from published reports into a specially formulated electronic datasheet with 10 % cross-checked by a second reviewer (MP). Information collected included a) General study details (title, authors, reference, year of publication), b) Study information (selection criteria, study design and methods, number of participants), c) Participant demographics (age, gender), d) Index test (type of CGM used, average duration of wear), e) Glucometric outcomes of interest including CGM metrics, OGTT, HbA1c, finger and plasma blood glucose levels and other relevant clinical characteristics including pulmonary (e.g. forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1], pulmonary exacerbations, microbiological status) and non-pulmonary (e.g. body mass index [BMI]) outcomes.

Risk of bias Assessment

The Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool was used to assess risk of bias using four key domains including patient selection, index test, reference standard and flow and timing [41]. A flow diagram and signalling questions were created and piloted (see Supplement 2: S4 and S5).

Study definitions

Given lack of consensus CGM criterion for diagnosis of CFRD and in line with the Cochrane systematic review protocol on the topic [39] that used the American Diabetes Association criteria as a clinical reference point; we defined CGM outcomes based on best evidence that maximised evaluation of all available contemporaneous CGM and OGTT data in PwCF in the published literature. CGM hyperglycemia was defined as ≥ 1 peak on sensor glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/L), CGM dysglycemia as ≥ 1 peak on sensor glucose ≥ 140 and < 199 mg/dL (≥7.8–11.0 mmol/L) and CGM normoglycemia as all peaks on sensor glucose < 139 mg/dL (<7.7 mmol/L). Fasting sensor glucose levels were rarely reported in the literature and consequently not included in any definitions.

Results of OGTT were classified according to the American Diabetes Association criteria into either normal glucose tolerance (NGT), impaired glucose tolerance, indeterminate glucose tolerance, impaired fasting glucose and CFRD [18]. Studies reporting indeterminate glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose were infrequent. Therefore, we defined abnormal glucose tolerance (AGT) in our protocol to collectively refer to impaired glucose tolerance, indeterminate glucose tolerance and impaired fasting glucose on OGTT.

For the purposes of our study, we developed criterion for an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes which was met if PwCF with normal or abnormal glucose tolerance tests demonstrated ≥ 1 peak on sensor glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL (≥11.1 mmol/L) on CGM.

Outcomes

We compared aligned criterion on CGM (i.e. ≥ 1 peak on sensor glucose ≥ 200 mg/dL) to the reference standard OGTT (i.e 2-hour plasma glucose level ≥ 200 mg/dL) for diagnosis. Our primary outcome was the relative risk of an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes compared to the accepted OGTT diagnosis of CFRD in people with cystic fibrosis. We elected not to report results in terms of CGM being ‘superior’ or having ‘higher sensitivity’ than the OGTT given a) there are no international consensus on the use of CGM as a screening or diagnostic test for CFRD b) OGTT remains the established reference gold standard and c) no supreme third reference test exists that CGM and OGTT can be directly compared to. For this reason, conventional screening test outcomes such as sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were not calculated and reported in our review. Potential inferences from our study findings are presented in Supplementary material S6.

Secondary outcomes included evaluating the prevalence of CGM hyperglycemia, dysglycemia and normoglycemia in NGT and AGT to explore differences in how glucose abnormalities may be captured by the two modalities with some alignment of criterion. The interrelationships between CGM and HbA1c, plasma and fingerpick blood glucose levels were also explored.

Statistical analysis and data synthesis

The primary outcome of relative risk was calculated by dividing the total number of individuals meeting criterion for an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes by the total number of individuals meeting accepted CFRD criteria on OGTT i.e. arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes in NGT + AGT / confirmed CFRD diagnosis on OGTT.

Secondary outcomes included calculating the percentage of individuals with NGT and AGT who had CGM hyperglycemia, dysglycemia and normoglycemia. If multiple studies demonstrated alignment of methods, definitions and outcomes, then a meta-analysis was planned. For secondary outcomes evaluating the relationship between CGM and other reference standards (e.g. HbA1c, fingerpick and plasma blood glucose levels), a qualitative synthesis was planned.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

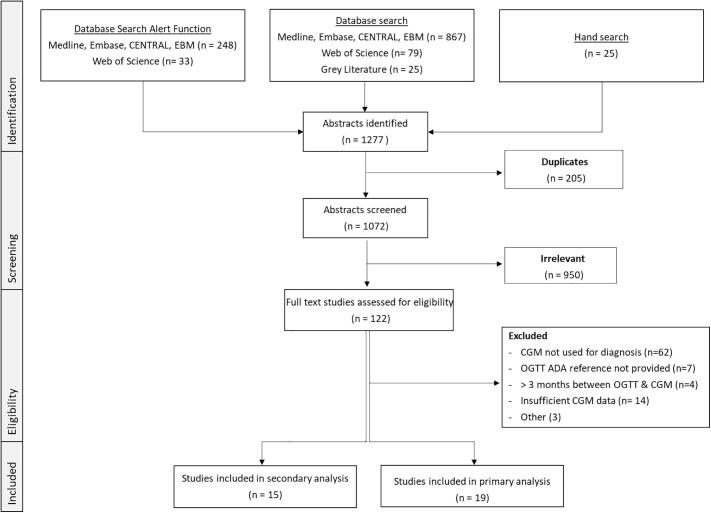

Fig. 1 shows a flow diagram of the study selection process. A total of 1277 publications were retrieved through the combination of original database searches, hand search and database alerts function until 30/6/2022. Following full-text review, 19 studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria for primary analysis. Of the 578 eligible participants, 162 were excluded largely due to insufficient published quantitative data. This resulted in a total of 416 individuals with contemporaneous CGM and OGTT (See Supplementary Material S7). Two recent studies by Chan et al [42] and Scully et al [43] reported comprehensive CGM metrics but not individual peak CGM sensor glucose readings therefore did not meet our protocol inclusion criteria, however their seminal findings are discussed in detail separately.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Definitions of hyperglycemia and dysglycemia varied significantly across studies, with most applying a variation of current American Diabetes Association diagnostic criteria for CFRD (See Table 1). Studies used different CGM devices, with Medtronic systems being the most common. Most studies excluded participants with an acute pulmonary exacerbation, cystic fibrosis related liver disease, significant coagulopathy, use of glucocorticoids, lung transplantation or pregnancy.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the primary analysis for comparisons of contemporaneous results from CGM and OGTT.

| Author | Year | Country | Study Type | Recruitment | n | Mean Age (yrs) | CGM used | Duration of CGM wear | Definition of Dysglycemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balzer*[44] | 2014 | Australia | Prospective | Selective | 14 | 25 | IPro2 | 6 days | Mean SG and range, AUC > 7.8 mmol/L |

| Boudreau[65] | 2017 | Canada | Prospective | Unclear | 15 | 35 | Dexcom | 7 days | Peak SG > 8.0 mmol/L abnormal |

| Dyce[66] | 2014 | UK | Retrospective | Unclear | 14 | NS | Not specified | NR | >4.5 % time monitored > 7.8 mmol/L defined as abnormal |

| Elidottir[52] | 2021 | Sweden | Prospective | Consecutive | 29 | 11.5 | Freestyle Libre | 14 days | Number of peak SG > 8 mmol/L and > 11.1 mmol/L measured + other CGM metrics |

| Franzese*[45] | 2008 | Italy | Prospective | Consecutive | 32 | 10 – 20 | Medtronic Minimed | 3 days | >1 SG peak > 7.8 mmol/L defined as impaired. > 1 SG peak > 11.1 mmol/L defined CFRD |

| Haliloglu[67] | 2017 | Turkey | Prospective | Consecutive | 44 | 13 | Medtronic Guardian | 3 days | >3% time > 11.1 mmol/L defined as abnormal |

| Helm[61] | 2009 | UK | Prospective | Unclear | 4 | 31 | Not specified | 3 days | Not explicitly defined – ‘diabetic range’ |

| Janssen[68] | 2010 | USA | Prospective | Unclear | 10 | NS | Medtronic | 3 days | SG range |

| Jefferies*[47] | 2004 | Canada | Prospective | Consecutive | 19 | 14 | Medtronic | 1–3 days | >1 SG peak > 7.8 mmol/L defined as impaired and > 11.1 mmol/L defined as CFRD |

| Khammar*[46] | 2009 | France | Prospective | Unclear | 20 | 14 | Not specified | 31 days | >1 SG peak > 11.1 mmol/L defined as CFRD |

| Leclerq[62] | 2013 | France | Prospective | Unclear | 38 | 26 | Medtronic | NR | >1 SG peak > 11.0 mmol/L defined as CFRD. Normal defined as peaks < 11.0 mmol/L |

| Leon[69] | 2018 | Spain | Prospective | Unclear | 30 | 14 | IProTM2 | 6 days | >1% time > 11.1 mmol/L defined as CFRD. < 1 % time > 11.1 mmol/L defined as impaired |

| Mainguy[70] | 2017 | France | Prospective | Consecutive | 29 | 13 | Medtronic Minimed | 3 days | SG peak > 7.8 mmol/L defined as impaired. SG peak > 11.1 mmol/L defined as CFRD. |

| Moreau[71] | 2008 | France | Prospective | Consecutive | 32 | 26 | Medtronic | 3 days | Normal defined as SG < 7.8 mmol/L. SG > 11.1 mmol/L defined as CFRD |

| O’Riordan[72] | 2006 | Ireland | Prospective | Unclear | 8 | Pediatric NS | Medtronic | 2 days | SG peak > 11.1 mmol/L defined as CFRD |

| Pu[58] | 2018 | Brazil | Prospective | Consecutive | 39 | 15 | Medtronic Minimed | 1–2 days | >1 SG peak > 7.8 mmol/L defined as impaired. > 1 SG peak > 11.1 mmol/L defined CFRD |

| Schiaffini[64] | 2010 | Italy | Prospective | Consecutive | 17 | 13 | Medtronic Minimed | 3 days | >2 SG peaks > 11.1 mmol/L defined as CFRD |

| Taylor-Cousar[63] | 2016 | USA | Prospective | Consecutive | 18 | 32 | Medtronic | 3 days | > 2 separate days of > 7.8 mmol/L defined as impaired or > 11.1 mmol/L defined CFRD |

| Widger[73] | 2011 | Australia | Prospective | Consecutive | 4 | 14 | Not specified | 3 days | >1 SG peak > 11.1 mmol/L defined as CFRD |

*Studies with high risk of selection bias due to inclusion of individuals with cystic fibrosis with reportedly previously abnormal blood glucose levels

NS not specified, SG sensor glucose result on continuous glucose monitoring, AUC area under the curve

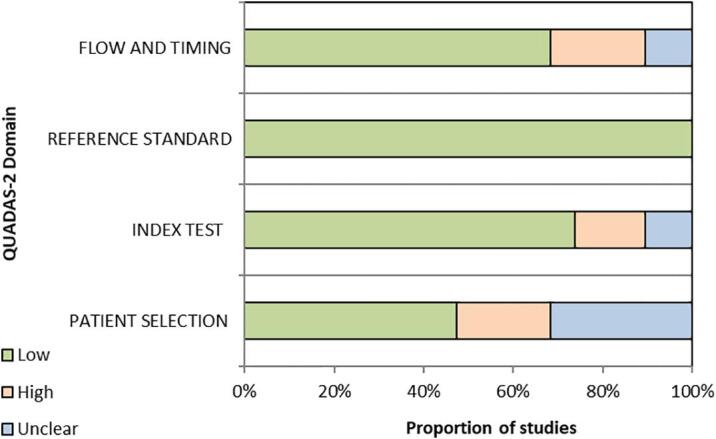

Risk of bias

Fig. 2 summarises overall risk of bias for studies included in the primary analysis according to the four QUADAS-2 domains. Four studies had very high risk of selection bias, with CGM performed due to clinical concern or known glucose abnormalities [44], [45], [46], [47]. Individual risk of bias for each study are presented in the Supplementary material S8.

Fig. 2.

Summary of overall risk of bias for studies included in the primary analysis.

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the study population was 18.6 years ± 8.0 with 159 (38.2 %) being male. Demographics were not reported by all the studies.

Primary outcome

Of the 416 individuals evaluated in our primary analysis, 51 met CFRD criteria on OGTT and the remaining 365 individuals (NGT = 253, AGT = 112) did not. Of the individuals without OGTT confirmed CFRD, 149 (85 NGT and 64 AGT) met criterion for an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes. Therefore, the calculated relative risk of an arbitrary diabetes diagnosis based on our CGM criterion compared to the reference standard OGTT was 2.92 (RR 149/51) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Results from studies with contemporaneous OGTT and CGM categorised according to protocol criterion.

|

Study |

Test |

Results |

Total |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Year |

OGTT |

Normal Glucose Tolerance (NGT) |

Abnormal Glucose Tolerance (AGT) |

CFRD | |||||

| CGM | Normoglycemia | Dysglycemia | Hyperglycemia | Normoglycemia | Dysglycemia | Hyperglycemia | ||||

| Balzer | 2014 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 14 | |

| Boudreau | 2017 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 15 | |

| Dyce | 2014 | 0 | 14 | NR | 0 | 0 | NR | 0 | 14 | |

| Elidottir | 2021 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 16 | 2 | 29 | |

| Franzese | 2008 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 32 | |

| Haliloglu | 2017 | 24 | NR | 10 | 0 | NR | 4 | 6 | 44 | |

| Helm | 2009 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | |

| Janssen | 2010 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | |

| Jefferies | 2004 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 7 | 19 | |

| Khammar | 2009 | 1 | NR | 9 | 3 | NR | 7 | 0 | 20 | |

| Leclerq | 2013 | 26 | NR | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 38 | |

| Leon | 2017 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 30 | |

| Mainguy | 2017 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 29 | |

| Moreau | 2008 | 14 | 0 | 8 | NR | NR | NR | 10 | 32 | |

| O'Riordan | 2007 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 2 | 4 | 2 | 8 | |

| Pu | 2018 | 9 | 14 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 39 | |

| Schiaffini | 2010 | 8 | NR | 3 | 3 | NR | 2 | 1 | 17 | |

| Taylor-Cousar | 2016 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 18 | |

| Widger | 2011 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | |

| Total (n) | 96 | 72 | 85 | 15 | 33 | 64 | 51 | 416 | ||

| Outcome of CGM |

NGT (total = 253) n % |

AGT (total = 112) n % |

Total (n = 365) n % |

|||||||

| CGM Normoglycemia | 96 (37.9 %) | 15 (13.4 %) | 111 (30.4 %) | |||||||

| CGM Dysglycemia | 72 (28.5 %) | 33 (29.5 %) | 105 (28.8 %) | |||||||

| CGM Hyperglycemia (i.e. arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes) | 85 (33.6 %) | 64 (57.1 %) | 149 (40.8 %) | |||||||

| Relative risk of diabetes diagnosis = n arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes/ n confirmed CFRD on OGTT = 149 / 51 | 2.92 | |||||||||

NR not reported

Secondary outcomes

Prevalence of CGM hyperglycemia, dysglycemia and normoglycemia

In individuals with NGT, 33.6 % (85/253) had CGM hyperglycemia, 28.5 % (72/253) had CGM dysglycemia and 37.9 % (96/253) had CGM normoglycemia. In individuals with AGT, 57.1 % (64/112) had CGM hyperglycemia, 29.5 % (33/112) had CGM dysglycemia and 13.4 % (15/112) had CGM normoglycemia. Overall, 41 % (n = 149/365) of individuals not meeting diabetes criteria on OGTT met criterion for an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes.

Comparison of CGM to other reference standards in people with cystic fibrosis

A total of 15 studies were included in a qualitative analysis (See Table 3) with Dobson et al [48] evaluating correlations between CGM and both fingerpick and plasma blood glucose levels. CGM was compared to HbA1c (n = 11)[47], [49], [50], [51], [52], [53], [54], [55], [56], [57], [58] fingerpick blood glucose levels (n = 3)[48], [59], [60] and plasma blood glucose level (n = 2)[48], [61]. Two studies [47], [50] also performed OGTT alongside CGM and HbA1c. Chan et al [50] reported HbA1c correlated with average glucose on CGM in PwCF, with the relationship comparable to people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Scully and colleagues [57] also found strong correlations between average glucose on CGM and HbA1c, which remained significant after adjustment for multiple variables (age, gender, ethnicity). They reported significant variability in HbA1c, average glucose and % time > 140 mg/dL on CGM but not in other CGM measures at 3-month follow-up [43].

Table 3.

Conclusions from studies comparing CGM to reference standards HbA1c, fingerpick and plasma blood glucose levels.

| Author | Year | Study Type | Recruitment | n | Pre-existing CFRD | Mean Age (yrs) |

CGM used |

HbA1c % | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CGM compared to HbA1c | |||||||||

| Brennan[49] | 2006 | Prospective | Unclear | 20 | 10 | 29 | Minimed | NR | Strong correlation between HbA1c and mean SG on CGM in CFRD R2 = 0.888 |

| Chan*[50] | 2018 | Prospective | Selective | 93 | 28 | 14 | IPro2 | 5.7 % | HbA1c correlated with multiple glycemic measures and didn’t underestimate average SG on CGM |

| Chan[51] | 2020 | Retrospective | Selective | 42 | 0 | 13 | IPro2 | 5.6 % | HbA1c normal despite hyperglycemia & glycemic variability on CGM in patients with NGT |

| Elidottir [52] | 2021 | Prospective | Consecutive | 29 | 2 | 11.2 | Freestyle Libre | 5.4 % | HbA1c significantly correlated with proportion of SG > 8 mmol/L during CGM (r(26) = 0.479, p = 0.013) and the average SG on CGM (r(26) = 0.517, p = 0.007). |

| Hope[53] | 2018 | Prospective | Unclear | 93 | Unclear | 14 | NS | 5.7 % | Strong correlation between HbA1c and average SG on CGM R = 0.86 |

| Jackson[54] | 2017 | Prospective | Unclear | 30 | 0 | Adults | NS | NR | 67 % (20/30) had glycemic abnormality detected on CGM with 2/30 having abnormal HbA1c |

| James[55] | 2019 | Retrospective | Unclear | – | Unclear | Adults | NS | NR | Moderate correlation between HbA1c and average SG on CGM (R = 0.667) |

| Jefferies* [47] | 2004 | Prospective | Consecutive | 19 | 7 | 14 | Medtronic | 6.3 % | Moderate correlation between HbA1c and average SG on CGM R2 = 0.42 |

| Manning [56] | 2022 | Retrospective | Selective | 52 | 52 | NR | Freestyle Libre | NR | Plasma HbA1c strongly correlated with estimated A1C (r = 0.90) |

| Pu [58] | 2018 | Prospective | Consecutive | 39 | 0 | 15 | Medtronic | NR | AUC values SG > 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) significantly associated with HbA1c (P = 0.026). % total time SG > 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) significantly associated with HbA1c (P = 0.027) |

| Scully [57] | 2020 | Prospective | Consecutive | 71 | 25 | 34 | Freestyle Libre | NR | HbA1c strongly correlated with average sensor glucose on CGM (R2 = 0.62, p=<0.001) with r’ship significant after adjustment for age, gender, pancreatic function, modulator use and ppFEV1 |

| Sensor glucose (SG) on CGM compared to fingerpick blood glucose level | |||||||||

| Cottam[59] | 2017 | Prospective | Unclear | 9 | NS | n/a | Freestyle Libre | n/a | Strong correlation between SG on CGM and fingerpick blood glucose levels (Spearman’s rho 0.947) however sensor glucose consistently lower |

| Dobson[48] | 2003 | Prospective | Unclear | 21 | 0 | 27 | Minimed | n/a | Strong correlation between SG on CGM and fingerpick blood glucose levels (R2 = 0.77) with a mean absolute difference 10.7 ± 8.7 %. |

| Howlett [60] | 2020 | Prospective | Consecutive | 18 | 18 | 36.4 | Freestyle libre | 7.6 | CGM vs fingerpick: mean absolute difference was 0.27 mmol/L (95 % CI −1.7 to 2.5), and for BGL < 4.0 mmol/L it was 0.47 mmol/L. Mean relative difference was 105 % (95 % CI 82 % to 130 %) |

| Sensor glucose (SG) on CGM compared to plasma blood glucose level | |||||||||

| Dobson[48] | 2003 | Prospective | Unclear | 21 | 0 | 27 | Minimed | n/a | Moderate correlation between SG on CGM and plasma blood glucose level (correlation coefficient 0.57) with a mean absolute difference 24.9 ± 21 % |

| Helm[61] | 2009 | Prospective | Unclear | 27 | 0 | Adults | Medtronic | n/a | CGM correlated well with plasma blood glucose level during OGTT |

*Study also performed OGTT alongside CGM and other reference measurements

Reporting of pulmonary, non-pulmonary and quality of life factors

Few studies reported associations between CGM and clinical outcomes. Khammar et al [46] found no difference in lung function and nutritional status between those with CGM hyperglycemia versus CGM normoglycemia. Elidottir and colleagues [52] reported a significant difference in lung function (as measured by FEV1% predicted) between those with CGM hyperglycemia (defined as ≥ 0.5 peaks per day of > 11 mmol/L on CGM p = 0.018) but no difference with regard to CGM dysglycemia. In contrast, Pu et al [58] reported no associations between FEV1 and CGM metrics (AUC and % total time > 200 mg/dL). Leclerq et al [62] reported no difference in intravenous antibiotic use between those with CGM hyperglycemia versus CGM normoglycemia, but noted the former had significantly higher rates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection/colonisation. Taylor-Cousar et al [63] reported no correlation between maximum sensor glucose on CGM and pulmonary exacerbations. Elidottir and colleagues [52] evaluated patient experiences of using CGM and reported high user acceptability and satisfaction.

Only two primary studies reported follow-up data with Schiaffini et al [64] repeating OGTT at 2.5 years and Taylor-Cousar et al [63] retrospectively reviewing clinical notes. Both studies found CGM hyperglycemia predicted progression to CFRD at future follow-up.

Discussion

Main findings

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review directly comparing contemporaneous results from CGM and the reference standard OGTT for the detection of hyperglycemia and dysglycemia in PwCF. Based on our study criterion, our findings suggest if CGM were to be used as a diagnostic test, then up to three times the number of PwCF would have met our arbitrary criterion for diabetes compared to the reference standard OGTT. According to our analysis, this would have resulted in up to half of all individuals not classified with diabetes on the OGTT given an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes. We found studies reported clinical outcomes on lung function [46], [52], [58], [62], [63], BMI [46], [58], [63], pulmonary exacerbation [63], microbiological status [62], and patient experiences of using CGM [52] however, none provided long-term prospective follow-up. Therefore, the clinical relevance and risks associated with using CGM for diagnosis of diabetes in PwCF remains unclear.

Alignment of findings with current position statements

The American Diabetes Association [18] and International Society for Pediatric and Adolescent Diabetes [17] currently do not support the use of CGM for the diagnosis of CFRD. This would align with our study findings whereby using criterion of ≥ 1 peak sensor glucose value > 200 mg/dL on CGM was associated with significantly increased detection of glucose abnormalities in PwCF compared to the OGTT with unknown clinical implications. Studies have linked dysglycemia detected on CGM with declines in lung function [52], [62], [74], poor recovery from pulmonary exacerbation [75], weight loss [20], [76] and increased risk of progression to CFRD [63], [64], however, the benefits of treating this dysglycemia remain underwhelming [44], [77], [78]. This is in contrast to impaired glucose tolerance detected on the OGTT, where some evidence exists to support insulin initiation with demonstrable improvements in weight, lung function and frequency of pulmonary exacerbations [79], [80], [81]. A multi-centre randomised controlled trial of once-daily insulin versus observation alone in PwCF with dysglycemia without a formal diagnosis of CFRD (CF-IDEA Trial, clinical trials.gov NCT01100892) is currently under-way to elucidate benefits of treating early glucose abnormalities.

Development of disease-specific cut points

Cystic fibrosis specific cut points on CGM should be based on adverse clinical outcomes such as lung function and/or nutritional decline given the distinct pathophysiological mechanisms responsible for the increased morbidity and mortality associated with CFRD [35], [82]. We found the key clinically relevant CGM metrics in PwCF were unclear amongst the analysed studies due to significant heterogeneity in definitions and inconsistent reporting of CGM metrics. From a mechanistic perspective, sustained dysglycemia rather than infrequent overt hyperglycemia on CGM may be of greater clinical relevance. For example, Hameed defined dysglycemia on CGM as 4.5 %-time (approximately 65 min/day) of sensor glucose reading ≥ 140 mg/dL (≥7.8 mmol/L) and found it correlated with declining weight and lung function [20]. Our own group has previously reported associations between percentage of total time ≥ 140 mg/dL (≥7.8 mmol/L) on CGM and poor pulmonary recovery following an exacerbation [75]. Additionally, international consensus on CGM reporting [83] do not include singular peaks above a pre-defined sensor glucose threshold as a key CGM metric. Only two studies [52], [58] in our primary analysis were published after this consensus statement with percentage total time spent > 140 mg/dL (>7.8 mmol/L) reported by one study, a metric they found was significantly associated with HbA1c [58].

Two recent studies by Chan et al [42] and Scully et al [43] prospectively and rigorously investigated relationships between the OGTT and key CGM metrics [83] such as average sensor glucose, percentage time above a sensor glucose threshold > 140 mg/dL equivalent to > 7.8 mmol/L (%T > 7.8), percentage time > 180 mg/dL equivalent to > 10.0 mmol/L (%T > 10.0), percentage time > 200 mg/dL equivalent to > 11.1 mmol/L (%T > 11.1), percentage time > 250 mg/dL equivalent to > 13.9 mmol/L (%T > 13.9), SD, coefficient of variation (CV) and mean amplitude of glucose excursion (MAGE). They did not report singular peaks above a pre-defined sensor glucose threshold on CGM therefore were not included in our primary analysis. Importantly, their studies were not designed to evaluate screening capabilities of CGM in PwCF, rather they focused on the capacity of CGM measures of dysglycemia (%T > 7.8), hyperglycemia (%T > 10.0, %T > 11.1, %T > 13.9) and glycemic variability (SD, CV, MAGE) to differentiate between PwCF with and without diabetes confirmed using the OGTT. Chan and colleagues used frequently sampled OGTT and CGM (iPRO2 CGM for 3–7 days) in 85 PwCF while Scully et al used the Freestyle Libre Pro and Dexcom G6/Pro devices in 77 PwCF. Scully et al found CGM measures of dysglycemia and hyperglycemia had high sensitivities (>90 %) and specificities (>80 %) for the detection of CFRD, in contrast to Chan et al who reported much lower sensitivities (67–75 %) and specificities (53–60 %). Scully et al also explored longitudinal interrelationships between CGM metrics and disease-specific clinical outcomes (FEV1 and BMI) and reported strong correlations between CGM measures of dysglycemia, hyperglycemia and glycemic variability. Given their positive findings, Scully and colleagues proposed two CGM measures demonstrating > 85 % sensitivity and specificity for identifying CFRD; 3.4 %-time > 180 mg/dL [equivalent to 49 min/day > 10.0 mmol/L] and 17.5 %-time > 140 mg/dL [equivalent to 252 min/day > 7.8 mmol/L]. Despite conflicting results, these studies provide the most comprehensive evidence to date on correlations between CGM metrics, OGTT and disease-specific outcomes. Furthermore, they highlight the deficiencies in rigor, particularly in the early studies included in our analysis, which likely reflect a learning curve associated with adoption of diabetes technology.

Standardisation of testing conditions

For CGM to be used in a diagnostic capacity, standardising testing conditions to ensure accuracy and reproducibility would be desirable. A pilot study in PwCF comparing contemporaneous hospital-based OGTT versus home-based OGTT using CGM and fingerpick blood glucose monitoring reported poor correlations in glucose levels [84] highlighting the importance of contextual factors impacting glycemia. Despite dysglycemia being more frequently detected on CGM compared to the OGTT [74], in our study we found 13.4 % (15/112) of individuals with AGT had CGM normoglycemia. This may have occurred due to behaviour modifications during unblinded CGM wear, unreported treatments such as modulator therapies and/or non-standardised OGTT conditions [85]. In contrast, factors such as diet, exercise, presence of intercurrent illness, pulmonary exacerbations and medications such as glucocorticoids could contribute to CGM hyperglycemia and dysglycemia. Reliance on singular peak sensor glucose criterion on CGM could amplify effects of testing conditions whilst percentage time metrics may be less vulnerable. Prolonged duration of CGM wear during stable disease might serve to increase opportunities for detection of glucose abnormalities, but on the other hand, CGM use during periods of illness such as a pulmonary exacerbation, may offer some of the earliest indications of β-cell dysfunction in PwCF.

Continuum of glucose abnormalities in cystic fibrosis

We found similar percentages of CGM dysglycemia in people with NGT and AGT and this aligns with findings from Scully’s cohort, whereby CGM measures of dysglycemia and hyperglycemia did not differentiate between these two groups [43]. Mid-OGTT glucose elevations > 140 and < 200 mg/dL mg/dL (>7.8–11.1 mmol/L) traditionally classified as NGT have recently been linked to early glucometabolic abnormalities [86] with refined OGTT criteria now emphasising the importance of distinct abnormalities such as indeterminate glucose tolerance in PwCF [23]. However, the transition from normal to diabetic glucose tolerance without any identifiable risk features [21], [64] together with low uptake of OGTT as a screening test poses a major barrier to early diagnosis of CFRD. Therefore, the potential for CGM to bridge this gap, and potentially combined with risk factors [26] to stratify and facilitate early diagnosis of CFRD is much needed and promising.

We found two studies reported CGM hyperglycemia predicted development of CFRD in the future [63], [64] however, a recent larger study showed CGM measures of dysglycemia only correlated with early weight decline at three years, despite detection of glucose abnormalities missed by the OGTT at baseline [87]. In PwCF, diverse epidemiological [21], [88], genetic [88], [89], therapeutic [90]) and clinical [16] factors may impact glycemia causing bidirectional changes in glucose levels, which have been detected on both OGTT [21] and CGM [57]. This complex continuum of glucose abnormalities governed by incompletely understood regulatory mechanisms such as the dynamic sensitivity of pancreatic β-cells to changes in glucose concentrations [86] coupled with heterogeneity of PwCF makes it challenging to define glycemia and its effects, regardless of the measurement tool used. This may explain the contrasting conclusions reached by Chan et al and Scully et al about whether CGM measures of hyperglycemia can reliably distinguish between individuals with and without CFRD. The dilemma of navigating these barriers while recognising the prognostic potential of CGM to detect glucose abnormalities, particularly in people with early clinical decline requires at this time a personalised approach and shared decision-making that balances potential unknown benefits with harms and futility.

Comparison to other reference tests

Our qualitative secondary analyses found reasonable correlation between average sensor glucose on CGM and HbA1c, however this may have been confounded by the significant number of individuals with confirmed CFRD in the studies. Comparison of estimated A1C (a CGM metric also known as glycemic management indicator) and plasma HbA1c may be useful to confirm and quantify if the latter underestimates glycemic control in PwCF. We found correlations between plasma and finger-prick BGL and sensor glucose on CGM was high, which could be useful for validating and stratifying the accuracy of different CGM devices available for use in PwCF.

In contrast to all other available diagnostic tests for diabetes, the capacity for CGM to provide rich glucometric data over a prolonged period of time makes it fit for purpose to capture the spectrum of glucose abnormalities that may be present in PwCF.

Strengths and weakness

Our review has several significant limitations. Firstly, definitions of CGM outcomes were extrapolated from American Diabetes Association criteria and a Cochrane systematic review protocol [39] on the topic and have low internal validity and clinical utility. Secondly, 162 potentially eligible participants were excluded predominantly due to insufficient data (n = 122) which may have introduced bias into our study by over or under-estimating the relative risk of an arbitrary CGM-diagnosis of diabetes. Thirdly, we acknowledge our analyses were significantly limited due to the methodological challenges arising from research in this field with heterogenous definitions, divergent clinical practice, inherent biases, small patient populations, lack of reporting key CGM metrics and learning curve associated with the adoption of diabetes technology. Over half of the studies failed to report how patients were selected which could have major implications given significant intra-and inter-individual heterogeneity with regards to glucose abnormalities in cystic fibrosis. Indeterminate glycemia may not have been recognised as a distinct entity during conduct of earlier studies, leading to PwCF meeting criteria falsely grouped as NGT instead of AGT in our study. Important clinical characteristics such as mutation status, pancreatic insufficiency, use of modulator therapy, and ethnicity were inconsistently reported. Studies also frequently failed to report whether CGM was blinded from the individual which could have implications for instigating behaviour change during the study period. Lastly, first-generation CGM devices used in the early 2000 s may have been vulnerable to hypoxia and potentially overestimated glucose concentrations [91].

Our study strengths include being the first systematic review on this topic and despite significant methodological limitations, by making few amendments to the original protocol (See Supplement 1) we deliver an organised, comprehensive and up-to-date overview of the stated problem, available evidence and gaps in knowledge.

Future directions

In people with type 1 diabetes, an evidence-base consisting of multiple large randomised controlled trials has been used to develop international consensus on standardised CGM metrics based on correlations with HbA1c and microvascular complications [92]. Major barriers exist to such an undertaking in PwCF. To facilitate high-quality research in this field, firstly reporting of standardised CGM metrics [92] and consensus on definitions for CGM measures of dysglycemia and hyperglycemia in PwCF would be helpful. Exploring associations between key CGM metrics such as glycaemic variability and percentage time above defined sensor glucose thresholds and clinically objective cystic fibrosis outcomes (e.g. FEV1, BMI, pulmonary exacerbations, microbiological status) together with epidemiological, genetic, therapeutic and clinical factors are required to better understand the complex continuum and bidirectionality of glucose abnormalities in PwCF and its effects. To explore longer-term interrelationships between CGM measures and disease-specific outcomes, prospective data collection and formation of repositories with collaborations across centres may be needed.

Before specific cut points based on disease-specific outcomes can be used to define diabetes on CGM, concurrent comparisons to reference standards such as the OGTT and HbA1c can ensure quality assurance and alignment. Once a sufficient evidence-base becomes available, then these disease-specific CGM cut points can serve as CGM targets for treatment, for which the effects will need separate evaluation. If treatment of early glucose abnormalities detected on CGM can be shown to improve clinical outcomes in PwCF, then alignment with OGTT and other reference standards may no longer be necessary, and consideration of a CGM-diagnosis of diabetes as an entity discrete from CFRD as currently defined may be needed.

Evaluation of consumer and healthcare provider experiences of using CGM for this purpose should also be encouraged as this will assist guideline development and implementation in the clinical setting. Finally, policies supporting use of CGM in PwCF may serve to increase funding, access and research and potentially result in geographically divergent clinical experiences and practice [93].

Conclusions

We found the research trajectory evaluating CGM as a diagnostic tool in PwCF has been fragmentary and under-developed owing to early learnings from the uptake of diabetes technology, with few recent seminal studies providing comprehensive insights. In our analysis, we found a single peak sensor glucose level > 200 mg/dL on CGM is not appropriate for the diagnosis of diabetes and compared to the oral glucose tolerance test, CGM was more likely to detect glucose abnormalities in people with cystic fibrosis owing to its capacity to capture more glucometric data over a prolonged period of time. With this in mind, if it were to be used as a diagnostic test, regardless of CGM criterion a much higher incidence of diabetes diagnoses could be expected. To advance this field, comprehensive reporting of CGM metrics and clinical characteristics together with reference to the OGTT and HbA1c should be encouraged in future studies. Prospective studies embracing collaborative approaches to data-driven research are needed to examine longitudinal interrelationships between CGM and clinically objective cystic fibrosis outcomes to allow for mechanistic understanding and diagnostic application, including the introduction of cystic fibrosis specific CGM cut points based on relevant clinical sequela.

Author Contributions

SK, MP, HT and GS contributed to study design. SK conducted the search, screening, data analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MP screened, piloted and reviewed/edited the manuscript. GS and HT reviewed/edited the manuscript. SK is the guarantor of this work and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis

Funding

SK is a PhD student supported by the Australian Government. HT is supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council by the Australian Government.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Joanne Enticott for advice on statistics, Dr Marie Misso for her input in protocol design and 65 km for CF, Cystic Fibrosis Victoria and Australia for their ongoing support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcte.2022.100305.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Mirtajani S., et al. Geographical distribution of cystic fibrosis; The past 70 years of data analyzis. Biomedical and Biotechnology Research Journal (BBRJ) 2017;1(2):105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 2.F. Ratjen et al. Cystic fibrosis Nature Reviews Disease Primers 1 1 2015 15010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.MacKenzie T., et al. Longevity of patients with cystic fibrosis in 2000 to 2010 and beyond: survival analysis of the cystic fibrosis foundation patient registry. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(4):233–241. doi: 10.7326/M13-0636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dupuis A., et al. Cystic fibrosis birth rates in canada: a decreasing trend since the onset of genetic testing. J Ped. 2005;147(3):312–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran A, D.J., Nathan B, Saeed A, Holme B, Thomas W, Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: current trends in prevalence, incidence, and mortality. Diabetes Care. Diabetes Care, 2009. 32(9): p. 1626 - 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Moran A., et al. Pancreatic endocrine function in cystic fibrosis. J Ped. 1991;118(5):715–723. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)80032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soave D., et al. Evidence for a causal relationship between early exocrine pancreatic disease and cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: a mendelian randomization study. Diabetes. 2014;63(6):2114–2119. doi: 10.2337/db13-1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koch C., et al. Presence of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes mellitus is tightly linked to poor lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis: Data from the European Epidemiologic Registry of Cystic Fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;32(5):343–350. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenecker J., et al. Diabetes mellitus in patients with cystic fibrosis: the impact of diabetes mellitus on pulmonary function and clinical outcome. Eur J Med Res. 2001;6(8):345–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milla C.E., Warwick W.J., Moran A. Trends in pulmonary function in patients with cystic fibrosis correlate with the degree of glucose intolerance at baseline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(3):891–895. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9904075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Limoli D.H., et al. Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa co-infection is associated with cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and poor clinical outcomes. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(6):947–953. doi: 10.1007/s10096-016-2621-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parkins M.D., Rendall J.C., Elborn J.S. Incidence and risk factors for pulmonary exacerbation treatment failures in patients with cystic fibrosis chronically infected with pseudomonas aeruginosa. Chest. 2012;141(2):485–493. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelstein S.M., et al. Diabetes mellitus associated with cystic fibrosis. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1988;112(3):373–377. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(88)80315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steinkamp G., von der Hardt H. Improvement of nutritional status and lung function after long-term nocturnal gastrostomy feedings in cystic fibrosis. The Journal of Pediatrics. 1994;124(2):244–249. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(94)70312-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shepherd R.W., et al. Nutritional rehabilitation in cystic fibrosis: controlled studies of effects on nutritional growth retardation, body protein turnover, and course of pulmonary disease. J Pediatr. 1986;109(5):788–794. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80695-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran A., et al. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and prognostic implications of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2677. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran, A., et al., ISPAD Clinical Practice Consensus Guidelines 2014. Management of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes in children and adolescents. Pediatr Diabetes, 2014. 15 Suppl 20: p. 65-76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Moran A., et al. Clinical care guidelines for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2697. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobson L., Sheldon C.D., Hattersley A.T. Conventional measures underestimate glycaemia in cystic fibrosis patients. Diabet Med. 2004;21(7):691–696. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01219.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hameed S., et al. Early glucose abnormalities in cystic fibrosis are preceded by poor weight gain. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):221–226. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lanng S., et al. Glucose tolerance in patients with cystic fibrosis: five year prospective study. BMJ. 1995;311(7006):655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7006.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmid K., et al. Predictors for future cystic fibrosis-related diabetes by oral glucose tolerance test. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(1):80–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coriati A., et al. The 1-h oral glucose tolerance test glucose and insulin values are associated with markers of clinical deterioration in cystic fibrosis. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53(3):359–366. doi: 10.1007/s00592-015-0791-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brodsky J., et al. Elevation of 1-hour plasma glucose during oral glucose tolerance testing is associated with worse pulmonary function in cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):292–295. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterescu A.E., et al. Natural history of glucose intolerance in patients with cystic fibrosis: ten-year prospective observation program. J Pediatr. 2010;156(4):613–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khare S., et al. Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: Prevalence, screening, and diagnosis. Journal of Clinical & Translational Endocrinology. 2022;27 doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2021.100290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Godbout A., et al. No relationship between mean plasma glucose and glycated haemoglobin in patients with cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2008;34(6 Pt 1):568–573. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holl R.W., et al. HbA1c is not recommended as a screening test for diabetes in cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(1):126. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.1.126b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilmour J.A., et al. Cystic fibrosis-related diabetes screening in adults: A gap analysis and evaluation of accuracy of glycated hemoglobin levels. Can J Diabetes. 2019;43(1):13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burgess J.C., et al. HbA1c as a screening tool for cystic fibrosis related diabetes. J Cyst Fibros. 2016;15(2):251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gerritsen M., Jansen J.A., Lutterman J.A. Performance of subcutaneously implanted glucose sensors for continuous monitoring. The Netherlands Journal of Medicine. 1999;54(4):167–179. doi: 10.1016/s0300-2977(99)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck R.W., et al. Effect of continuous glucose monitoring on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes using insulin injections: the diamond randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(4):371–378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lind M., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring vs conventional therapy for glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes treated with multiple daily insulin injections: the gold randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(4):379–387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.19976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Polonsky W.H., et al. The impact of continuous glucose monitoring on markers of quality of life in adults with type 1 diabetes: further findings from the diamond randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(6):736. doi: 10.2337/dc17-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chan C.L. Continuous glucose monitoring in cystic fibrosis–Benefits, limitations, and opportunities. J Cyst Fibros. 2021;20(5):725–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alexander S, B.N., Balfour-Lynn I et al, Clinical Care Guidelines of Children with CF. NHS Foundation Trust, 2020.

- 37.Chan C.L., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in cystic fibrosis - A practical guide. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(Suppl 2):S25–S31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2019.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kumar S., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring versus self-monitoring of blood glucose in the management of cystic fibrosis related diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cyst Fibros. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2022.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahmed M.I., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring systems for the diagnosis of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes. The. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018;2018(2):CD012953. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013755.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moher D., et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whiting P.F., et al. QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chan C.L., et al. The Relationship Between Continuous Glucose Monitoring and OGTT in Youth and Young Adults With Cystic Fibrosis. J Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2022;107(2):e548–e560. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scully K.J., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring and HbA1c in Cystic Fibrosis: Clinical correlations and implications for CFRD Diagnosis. J Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2022;107(4):e1444–e1454. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgab857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Balzer B.W.R., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring as a useful decision-making tool for adults with cystic fibrosis. Internet Journal of. Pulmonary Medicine. 2014;16(1) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Franzese A., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring system in the screening of early glucose derangements in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2008;21(2):109–116. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2008.21.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khammar A., et al. Value of continuous glucose monitoring in screening for diabetes in cystic fibrosis. [French] Arch Pediatr. 2009;16(12):1540–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jefferies C.A., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Diabetes. 2004;53 SUPPLEMENT(2):A104. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dobson L., et al. Validation of interstitial fluid continuous glucose monitoring in cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(6):1940–1941. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.6.1940-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brennan A.L., et al. Relationship between glycosylated haemoglobin and mean plasma glucose concentration in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2006;5(1):27–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2005.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan C.L., et al. Hemoglobin A1c accurately predicts continuous glucose monitoring-derived average glucose in youth and young adults with cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(7):1406–1413. doi: 10.2337/dc17-2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan C.L., et al. Lessons from continuous glucose monitoring in youth with pre-Type 1 diabetes, obesity, and cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(3):e35–e37. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Elidottir, H., et al., Abnormal glucose tolerance and lung function in children with cystic fibrosis. Comparing oral glucose tolerance test and continuous glucose monitoring. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Hope E., et al. 18 Haemoglobin a1c predicts average glucose by continuous glucose monitoring in youth with cystic fibrosis. J Investig Med. 2018;66(1):A70. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jackson V.M., Dyce P., Walshaw M.J. Exploring the utility of continuous glucose monitoring (CGMS) for cystic fibrosis related diabetes (CFRD) J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(Supplement 1):S137. [Google Scholar]

- 55.James S., et al. Redefining estimated average glucose (eAG) for cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2019;18(Supplement 1):S138. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Manning D.E., et al. P175 How accurate is the glucose management indicator calculated by continuous glucose monitoring compared to the blood HbA1c reading in patients with cystic fibrosis? J Cyst Fibros. 2022;21:S115. [Google Scholar]

- 57.K.J. Scully M.K.R.e.a., Poster Session Abstracts - The relationship between haemoglobin A1c and average glucose derived from continuous glucose monitoring in adults with CF Pediatr Pulmonol 55 S2 2020 S38 S361.

- 58.Zorrón Mei Hsia P.u., M.,, et al. Continuous glucose monitoring to evaluate glycaemic abnormalities in cystic fibrosis. Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(6):592. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-314250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cottam S., et al. Real life evaluation of the introduction of Freestyle Libre continuous glucose system versus capillary blood glucose monitoring in patients with cystic fibrosis related diabetes. J Cyst Fibros. 2017;16(Supplement 1):S35. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Howlett C., et al. P249 Clinical utility and effectiveness of the flash glucose monitor FreeStyle Libre versus capillary blood glucose (CBG) measurements in adults with Cystic Fibrosis-Related Diabetes (CFRD) – a pilot study. J Cyst Fibros. 2020;19:S126. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Helm J., et al. Interstitial glucose monitoring during oral glucose tolerance testing in CF – Early results from an ongoing study. Pediatr pulmonol. 2009;44:418. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leclercq A., et al. Early assessment of glucose abnormalities during continuous glucose monitoring associated with lung function impairment in cystic fibrosis patients. J Cyst Fibros. 2014;13(4):478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taylor-Cousar J.L., et al. Glucose >200 mg/dL during Continuous Glucose Monitoring Identifies Adult Patients at Risk for Development of Cystic Fibrosis Related Diabetes. J Diabetes Research. 2016;2016:1527932. doi: 10.1155/2016/1527932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schiaffini R., et al. Abnormal glucose tolerance in children with cystic fibrosis: the predictive role of continuous glucose monitoring system. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;162(4):705–710. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boudreau V., et al. Glycemic excursions in adult patients with cystic fibrosis during oral glucose tolerance test and 7 days of continuous glucose monitoring: Relationship with YKL-40 (Preliminary data) Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(Supplement 47):468. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dyce P., Jones G., Walshaw M. Comparison of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) and oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT) in the detection of early CFRD. Pediatr pulmonol. 2014;49:428. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Haliloglu, B., et al., Hypoglycemia is common in children with cystic fibrosis and seen predominantly in females. 2017. 18(7): p. 607-613. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 68.Janssen J.S., et al. Correlation between continuous glucose monitoring & OGTT for detection of diabetes in adult cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(SUPPL. 33):433. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Leon MC, G.L.M.-G.A.M.A., Tizzano SG. Fernandez DY, Lezcano CA., Oral glucose tolerance test and continuous glucose monitoring to assess diabetes development in cystic fibrosis patients. Endocrinologia, diabetes y nutricion, 2018. 65(1): p. 45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Mainguy C., et al. Sensitivity and specificity of different methods for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes screening: is the oral glucose tolerance test still the standard? J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2017;30(1):27–35. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2016-0184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moreau F., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in cystic fibrosis patients according to the glucose tolerance. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40(7):502–506. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1062723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oriordan S., et al. Can continuous glucose monitoring (CGMS) enhance the detection of CFRD in 167 Cystic Fibrosis Children?: 72-OR. Diabetes. 2006;55:A17–A18. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Widger J., et al. Glucose tolerance during pulmonary exacerbations in children with cystic fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2011;38(SUPPL:55). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chan C.L., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring abnormalities in cystic fibrosis youth correlate with pulmonary function decline. J Cyst Fibros. 2018;17(6):783–790. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pallin M., et al. Continuous glucose monitoring indices predict poor FEV1 recovery following cystic fibrosis pulmonary exacerbations. J Cyst Fibros. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Prentice B.J., et al. Glucose abnormalities detected by continuous glucose monitoring are common in young children with Cystic Fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Moran A., et al. Insulin therapy to improve BMI in cystic fibrosis-related diabetes without fasting hyperglycemia: results of the cystic fibrosis related diabetes therapy trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(10):1783–1788. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Minicucci L., et al. Slow-release insulin in cystic fibrosis patients with glucose intolerance: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatric Diabetes. 2012;13(2):197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bizzarri C., et al. Clinical effects of early treatment with insulin glargine in patients with cystic fibrosis and impaired glucose tolerance. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29(3):p. Rc1-4. doi: 10.1007/BF03345538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mozzillo E., et al. One-year glargine treatment can improve the course of lung disease in children and adolescents with cystic fibrosis and early glucose derangements. Pediatric diabetes. 2009;10(3):162–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lanng S., et al. Diabetes mellitus in cystic fibrosis: effect of insulin therapy on lung function and infections. Acta Paediatr. 1994;83(8):849–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb13156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Waugh N., et al. Screening for cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: a systematic review. Health technology assessment (Winchester, England) 2012;16(24):iii–179. doi: 10.3310/hta16240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Danne T., et al. International consensus on use of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(12):1631–1640. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Boudreau, V., et al., P244 Simplification of Cystic Fibrosis-Related Diabetes screening by the use of a home-based oral glucose tolerance test: a pilot study to evaluate feasibility, validity and patient perception (AtHome). Vol. 19. 2020. S125.

- 85.Ehrhardt N., Al Zaghal E. Continuous glucose monitoring as a behavior modification tool. Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(2):126–131. doi: 10.2337/cd19-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Piona C., et al. Glucose tolerance stages in cystic fibrosis are identified by a unique pattern of defects of beta-cell function. J Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2021;106(4):1793–1802. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Zorron M., et al. Can continuous glucose monitoring predict cystic fibrosis-related diabetes and worse clinical outcome? J Bras Pneumol. 2022;48(2) doi: 10.36416/1806-3756/e20210307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lewis C., et al. Diabetes-related mortality in adults with cystic fibrosis. Role of genotype and sex. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(2):194–200. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0576OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Adler A.I., et al. Genetic determinants and epidemiology of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: results from a british cohort of children and adults. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(9):1789–1794. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.McGarry M.E., et al. Left behind: The potential impact of CFTR modulators on racial and ethnic disparities in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2022;42:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2021.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Klonoff D.C., Ahn D., Drincic A. Continuous glucose monitoring: A review of the technology and clinical use. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;133:178–192. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Battelino T., et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabetes Care. 2019;42(8):1593. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Weiss L., et al. Clinical practice versus guidelines for the screening of cystic fibrosis-related diabetes: A French survey from the 47 centers. J Clin Transl Endocrinol. 2022;28 doi: 10.1016/j.jcte.2022.100298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.