Highlights

-

•

Stable isotopes of peanuts and their different fractions are investigated.

-

•

Stable C, N, O and H isotopes of peanuts are used to assign production origin.

-

•

Peanuts are leguminous plants and fix nitrogen from the atmosphere.

-

•

Peanut δ15N is unaffected by processing and indicates soil nitrification processes.

-

•

LDA model achieved higher classification rates than k-NN and SVM models.

Keywords: Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), Processing, Stable isotopes, Geographical origin, Chemometrics

Abstract

This study investigates the use of stable isotopes (C, N, H, and O) to characterize the geographical origin of peanuts along with different peanut fractions including whole peanut kernel, peanut shell, delipidized peanuts and peanut oil. Peanut samples were procured in 2017 from three distinctive growing regions (Shandong, Jilin, and Jiangsu) in China. Peanut processing significantly influenced the δ13C, δ2H, and δ18O values of different peanut fractions, whereas δ15N values were consistent across all fractions and unaffected by peanut processing. Geographical differences of peanut kernels and associated peanut fractions showed a maximum variance for δ15N and δ18O values which indicated their strong potential to discriminate origin. Different geographical classification models (SVM, LDA, and k-NN) were tested for peanut kernels and associated peanut fractions. LDA achieved the highest classification percentage, both on the training and validation sets. Delipidized peanuts had the best classification rate compared to the other fractions.

Introduction

Peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) is one of the major oilseed crops and is grown globally, mainly as a cash crop. In China, peanuts are widely cultivated, with China ranked among the top peanut producers and exporters in the world (Zhao, Wang, & Yang, 2020). Total peanut production in China reached 17.33 million tons in 2019 (National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2019), 2019). Its kernel is rich in edible oil (45 to 55 %) and provides a valuable source of macro and micronutrients (Shokunbi, Fayomi, Sonuga, & Tayo, 2012). However, its quality and safety is strongly associated with its growing origin. Peanuts are highly enriched in oil and are widely used as a raw material for oil extraction. Its oil content is strongly associated with the grown origin (Liang, 2021, Wang et al., 2021). However the potential contamination of peanuts from aflatoxins and heavy metals uptaken through irrigation water etc. is a serious food safety issue in peanut-producing areas (Liu et al., 2022, Lu et al., 2013). In China, peanuts produced in some regions including Heishan, Luanxian and Tongxu, etc. have been declared as Protected Geographical Indication (PGI) products and sell at a high premium than other regions. Mislabeling and adulteration of these PGI products for financial gain is a growing concern that now requires an effective analytical technique for authentication and origin identification of PGI peanuts and their products.

Recently, a few studies have explored the potential of different analytical techniques to determine the geographical authenticity of peanuts. In this context, only trace element analysis and NIR fingerprints have been applied to discriminate the geographical origin of peanuts (Wang et al., 2021, Zhao et al., 2020). Multivariate analysis revealed infrared spectral absorbance at different wavenumbers including 2923 cm−1, 2851 cm−1, 1742 cm−1, 1162 cm−1, and 1051 cm−1 were associated with sub origin classification (Wang et al., 2021). Isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS) and the analysis of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, and sulfur stable isotopes have also been widely used in food traceability research (Krauß et al., 2020, Liu et al., 2019, Wadood et al., 2018) and depends on a number of abiotic factors. Isotope ratio measurement of a bulk sample or a particular fraction can provide useful information regarding its provenance. Carbon (δ13C) isotopes of plants mainly depends on their photosynthetic pathways such as C3 (Calvin cycle) pathway, C4 (Hatch-Slack) pathway, and CAM photosynthesis which provide clear carbon isotopic distinctions (Roy, Hall, Mix, & Bonnichsen, 2005). Peanuts are leguminous C3 plants and follow the Calvin cycle for carbon assimilation. Nitrogen (δ15N) isotope ratios in the plants depend on various factors such as farming or fertilizer practices, soil and climatic conditions, and plant type (nitrogen-fixing or non-nitrogen fixing (Bateman, Kelly, & Woolfe, 2007). Peanuts are nitrogen-fixing, leguminous plants which remove nitrogen from the air and fix it in the soil via nitrogen-fixing bradyrhizobium nodules located on peanut roots (Wang et al., 2019). Oxygen (δ18O) and hydrogen (δ2H) isotopes fractionate during condensation and evaporation processes of the water cycle and the rate of fractionation depends on rainwater or groundwater input, local temperature, atmospheric oxygen, and CO2 pressure. In addition, plant physiology also plays an important isotopic fractionation role within the plants (de Rijke et al., 2016) Moreover, the variation of these stable isotope ratios in agricultural products was also reported during different industrialized food processing steps. In this context, isotope effects from wheat processing including wheat milling, noodle fabrication, and cooking was investigated and found that wheat processing had no effect on δ13C or δ15N values or only slightly influenced δ2H and δ18O values by different processing techniques (Wadood et al., 2018, Wadood et al., 2019).

There is a growing demand by Chinese consumers for high-quality regional products. Peanuts are a very popular snack food and widely used for cooking. However peanuts are especially vulnerable to aflatoxin contamination, so consumers are more concerned about peanut traceability and geographical origin to ensure higher standards of food safety. To date, there are no reported studies on the use of stable isotopes to geographically trace the origin of peanuts. In this study, stable isotopes (C, N, H, and O) were measured in different peanut fractions (whole peanut kernel, shell, delipidized peanuts and oil) procured from three different geographical areas in China. The aim of this study was to measure the isotopic variations among different peanut fractions and identify geographical origin characteristics of peanuts using stable isotopes combined with multivariate data analysis.

Materials and methods

Sample collection and site description

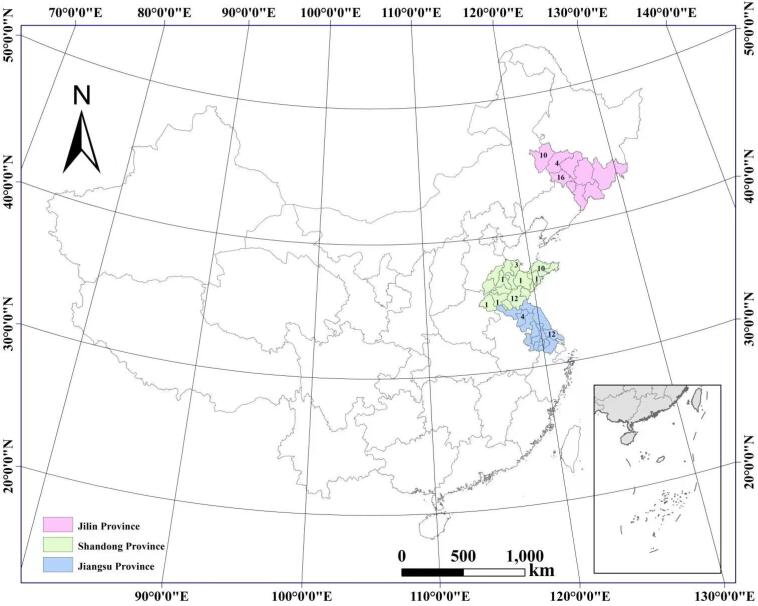

Around 100 g of peanut samples were harvested and collected in 2017 from 76 farms in three main peanut-producing regions of China, including Shandong Province (n = 30), Jilin Province (n = 30), and Jiangsu Province (n = 16) as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Geographical location of peanuts sampled from different producing regions in China.

Processing of peanut samples

Each sample consisted of different peanut fractions, including peanut shell, whole peanut kernel, delipidized kernel, and peanut oil. About 10 g of peanut pods were selected for each sample analysis. The separated and peeled fractions as whole peanut kernel and shell were freeze-dried and grounded into a fine powder. Delipidized peanuts (kernel) and peanut oil were obtained following an oil extraction procedure: 0.5 g of powder peanut kernel samples were delipidized using Soxhlet solvent extraction (SER 148, VELP Scientifica) using 50 mL of solvent (chloroform: petroleum ether, 70/30 v:v) for 6 h. The lipid extracts were stored in a freezer at −20 °C and the dried, powdered samples were stored in a desiccator at room temperature until analysis. All samples were analyzed within 1 month after preparation.

Stable isotope analysis

A quantity of 4.5 mg of dried powdered samples of different peanut fractions (peanut kernel, peanut shell, and delipidized kernel) and 0.2 mg of peanut oil were weighed in duplicate and packed into tin capsules (3 × 5 mm). For C and N isotopes, samples were analyzed in an elemental analyzer (Vario Pyro Cube, Elementar, Germany) coupled with an isotope ratio mass spectrometer (EA-IRMS) (IsoPrime100, England). The samples were converted into CO2 and NOx at high temperature (920 ͦC) in the combustion furnace under a flow of oxygen. Subsequently, an inert carrier gas (helium) with a flow rate of 230 mL/min transferred the combusted sample into a reduction chamber (600 ͦC) where NOx is reduced into nitrogen (N2) gas. The gases were finally transferred to the IRMS for isotope determination.

For H and O isotopes, 0.9 to 1.2 mg of powdered kernel, shell and delipidized kernel were weighed and folded into isotope grade silver capsules (6 × 4 mm). The samples were equilibrated in a desiccator for seventy-two hours. Subsequently, samples were introduced into an elemental analyzer via an autosampler. High temperature combustion (1450 ͦC) was achieved using pyrolysis to convert organic H and O to gaseous H2 and CO, respectively and finally the gases transferred into the IRMS for the isotope determination. The carrier gas (helium) was maintained at the flow rate of 120 mL/min and the pressure of the reference gas was 4 bar. The isotope values are expressed in delta notation and calculated using the following equation:

Where δE represents δ13C, δ15 N, δ2H, and δ18O whereas Rsample and Rstandard represent the 13C/12C, 15N/14N, 2H/1H or 18O/16O ratio in samples and references, respectively. Peanut kernel, shell and delipidized kernel samples were also calibrated against IAEA-CH6 (Sucrose, δ13C = -10.4 ‰), USGS 64(Glycine, δ13C = -40.8 ‰), IAEA-N-2 (Ammonium Sulfate, δ15 N = 20.3 ‰), USGS 40 (l-glutamic acid, δ15 N = -4.5 ‰). The peanut oil was also calibrated using B2172 (olive oil, δ13C = -29.3 ‰) which was obtained from Elemental Microanalysis (United Kingdom). Reference standard materials USGS 54 (δ2H = -150.4 ‰, δ18O = 17.8 ‰) and USGS 56 (δ2H = -44.0 ‰, δ18O = 27.3 ‰) were used for H and O isotope calibration of kernels and shells. Reference standard materials IAEA-CH-7 (polyethylene, δ2H = -100.3 ‰) and IAEA-601 (Benzoic Acid, δ18O = 23.3 ‰) supplied by IAEA were calibrated for H and O isotopes of peanut oil samples. The method precision was lower than 0.1 ‰ for δ13C, 0.2 ‰ for δ15N, 2.0 ‰ for δ2H, and 0.5 ‰ for δ18O, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Different statistical analyses including one-way analysis of variance (one way ANOVA), multi-way ANOVA, box and whisker plots, k-nearest neighbor (k-NN), support vector machines (SVM) and Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) were applied. All analysis except k-NN and SVM models were conducted using SPSS for Windows 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). k-NN and SVM models were analyzed using XLSTAT. One-way analysis of variance combined with Duncan’s test was applied to test the statistical significance between different origins of peanut and the different peanut fractions. Box plots combined with Duncan’s test were used to check the isotope variations between different peanut fractions. Multi-way ANOVA was applied to check the influence of different factors (regions, fractions, and their interactions) by calculating the contribution rate following mean square values. Finally, LDA, k-NN and SVM were applied to classify the geographical origin of the peanut samples. Segmented cross-validation was applied to all samples to validate the model.

Results and discussion

Stable isotopes (δ13C, δ15N, δ2H, δ18O) of peanut samples among different regions

Carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and oxygen isotopes (δ13C, δ15N, δ2H and δ18O) and carbon and nitrogen contents of peanut kernel and different peanut fractions including peanut shell, delipidized kernel and oil were determined and are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean %C, %N, δ13C, δ15N, δ2H, and δ18O values of different peanut fractions from different geographical regions.

|

Fractions |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Peanut Kernels |

Peanut Shells |

Defatted Kernel |

Oil |

||

| Isotopes | Regions | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD |

| C% | Shandong | 59.7 ± 3.1a | 46.1 ± 0.7 a | N/A | N/A |

| Jilin | 58 ± 1.7b | 46.1 ± 0.7 a | N/A | N/A | |

| Jiangsu | 59.9 ± 1.1a | 45.6 ± 1.4 a | N/A | N/A | |

| N% | Shandong | 4.4 ± 0.4 a | 0.8 ± 0.3 a | N/A | N/A |

| Jilin | 4.5 ± 0.5 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 a | N/A | N/A | |

| Jiangsu | 4.5 ± 0.4 a | 0.8 ± 0.1 a | N/A | N/A | |

| δ13C | Shandong | −28.4 ± 0.4b | −27.3 ± 0.7b | −25.5 ± 0.5b | −29.3 ± 1.3a |

| Jilin | −27.8 ± 0.6 a | −26.6 ± 0.6a | −24.7 ± 0.4a | −29.5 ± 0.4a | |

| Jiangsu | −29.3 ± 0.7c | −28.1 ± 0.6c | −26.6 ± 0.6c | −30.8 ± 0.6b | |

| δ15N | Shandong | −0.3 ± 1.2b | 1.8 ± 1.0a | −0.5 ± 1.1b | NA |

| Jilin | −0.1 ± 1.3b | 1.4 ± 1.9a | 0.1 ± 1.3b | NA | |

| Jiangsu | 1.9 ± 1.9a | 2.1 ± 1.6a | 2.2 ± 1.9a | NA | |

| δ2H | Shandong | −192.4 ± 11.9b | −95.3 ± 6.3b | −93.0 ± 7.4a | −265.3 ± 18.6c |

| Jilin | −174.4 ± 4.9a | −93.8 ± 4.1ab | −90.4 ± 5.9a | −256.3 ± 7.5b | |

| Jiangsu | −195.8 ± 10.6b | −90.9 ± 4.7a | −90.9 ± 6.2a | −246.4 ± 13.5a | |

| δ18O | Shandong | 14.2 ± 1.6c | 16.3 ± 1.3b | 16.0 ± 1.7b | 15.7 ± 1.6b |

| Jilin | 18.7 ± 1.4a | 18.9 ± 0.9a | 20.4 ± 0.8a | 17.6 ± 0.9a | |

| Jiangsu | 15.2 ± 0.9b | 16.4 ± 1.2b | 16.2 ± 0.5b | 15.2 ± 0.9b | |

The δ13C values of peanut kernels ranged between −29.3 to −27.8 ‰. Post-hoc tests showed significant δ13C differences among different regions (p < 0.05). The highest δ13C values were observed in Jilin samples followed by Shandong and the lowest δ13C values were found in Jiangsu. Overall, δ13C values exhibited a significant increase when going from east (Shandong province, warmer temperatures) to north (Jilin province, cooler, drier temperatures). Plants in cooler climates may experience a higher degree of stomatal closure, less water availability and higher water use efficiency than in warmer climates (Bontempo, Camin, Paolini, Micheloni, & Laursen, 2016). Jiangsu, Shandong, and Jilin are located at different altitudes 16.7 m, 49.31 m, and 196 m, respectively and it has been reported that several climatic (e.g., rain, atmospheric pressure, sunshine) and edaphic (e.g., nutrient content, soil water holding capacity) factors that covary with altitude are responsible to impart significant variations in δ13C values. Most importantly, δ13C fractionation during photosynthesis in C3 plants decreases with altitude because of greater carboxylation effect (Graves, Romanek, & Rodriguez Navarro, 2002). Other factors including plant physiology, solar radiation are also responsible for variations in δ13C values (Anderson and Smith, 2006, Wadood et al., 2018).

Peanut kernel δ15N values ranged from −0.34 to 1.89 ‰ with slightly higher values found in Jiangsu samples and the lower values in Shandong. Peanuts are nitrogen-fixing plants which typically have low δ15N values similar to the δ15N values in air (0 ‰). Slight variations between the three regions are more likely attributed to different climatic conditions which can change the physiology of plants and/or soil conditions allowing more or less nitrogen stockage in soils and uptake in plants. Slightly higher δ15N values in Jiangsu region peanuts compared to Jilin and Shandong peanuts reflect the uptake of stored atmospheric nitrogen from the soil, while lower δ15N values in the Shandong region reveal direct plant uptake of atmospheric nitrogen (ammonia mineralization) from nitrogen-fixing (Charles & Garten, 1993). Furthermore, soil characteristics and agricultural practices also impart variations in the δ15N values (Yuan et al., 2018). Soil characteristics among these regions have great diversity and N-stocking ability which influences δ15N values. Jilin region soils are mostly chernozem, aeolian sandy, and meadow soils, those in Jiangsu are sandy, brown, and yellow–brown soils; while Shandong has brown and cinnamon soils (Zhao et al., 2020).

δ2H peanut values also showed variations among different regions with the highest mean value (-174.39 ‰) found in Jilin while the lowest value (-195.76 ‰) was observed in the Jiangsu region. The main source of plant hydrogen is water taken up by the roots which is subsequently transpired through leaf stomata (Ziegler, Osmind, Stichler, & Trimborn, 1976). Therefore, more positive δ2H values are found in cooler, drier regions, where the evapotranspiration rate from leaf stomata is higher due to lower humidity. It has been reported that δ2H values become depleted with increasing inland distance from the coast (Dansgaard, 1964, Gat, 1996, Krauß et al., 2020). No significant difference was observed between peanut samples from Shandong and Jiangsu regions probably because of similar climatic conditions.

In the case of peanut oxygen (δ18O) isotopes, significant differences were observed for all three regions. A decreasing trend was observed for mean δ18O peanut values for the three regions with Jilin > Jiangsu > Shandong, respectively. δ18O values of local meteoric water are mainly associated with altitude, latitude, distance from the ocean, and the rate of evapotranspiration (Kern et al., 2020). Climatic differences among these regions are distinct and are the main contributor to peanut isotopic fractionation. Jilin province experiences a temperate, continental monsoon climate; Jiangsu province is a temperate to subtropical zone, whereas Shandong province experiences a warmer temperate, monsoon climate. Isotopic variations are reported between climatic conditions and δ18O values (Brescia et al., 2002). Mean peanut carbon content (%C) showed significant differences between Jilin/Shandong and Jilin/Jiangsu, while %N of peanuts did not exhibit any significant differences among regions.

Variation of stable isotopes (δ13C, δ15N, δ2H, δ18O) among different peanut fractions

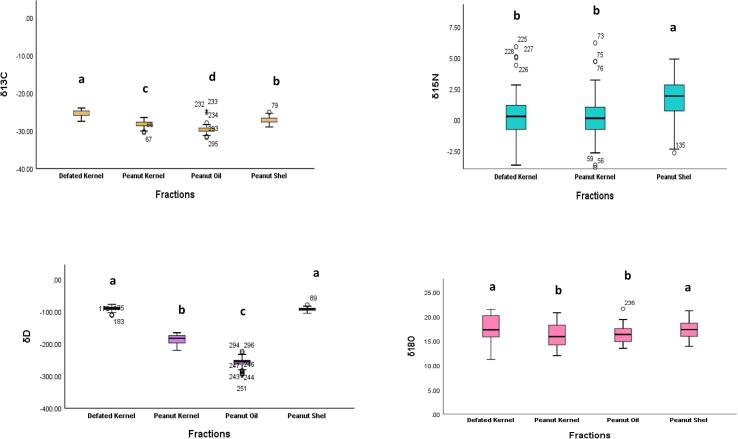

The δ13C, δ15N, δ2H and δ18O values of the different peanut fractions including peanut kernel, peanut shell, delipidized kernel, and oil from each region were calculated and shown in Fig. 2 in the form of univariate box and whisker plots. In the case of δ13C, the most positive mean δ13C value (-25.4 ‰) was found in the delipidized kernel and the most negative mean δ13C value (-29.7 ‰) in peanut oil. For the different peanut fractions, a decreasing δ13C trend of delipidized kernel > peanut shell > peanut kernel > peanut oil, respectively. Post-hoc tests (DMR) showed significant differences among all fractions (p < 0.05). Peanuts contain high-fat contents (>50 %) we compare our bulk and delipidized peanut δ13C values with those from peanut oil. Our findings were consistent with previous research (Guo et al., 2010, Steele et al., 2010). Lipids are the most depleted naturally occurring organic material, therefore the removing oil from peanuts (delipidization) will have an impact on its δ13C values, especially as peanuts have a high fat content (>40 %) (DeNiro and Epstein, 1977, Krauß et al., 2020, Post et al., 2007). For this reason, the delipidized sample is usually considered to more accurately reflect its carbon isotopic value (Tulli et al., 2020).

Fig. 2.

Box and whisker diagram of carbon (δ13C), nitrogen (δ15N), oxygen (δ18O), and hydrogen (δ2H) of peanuts and different peanut fractions from three production regions. The centre line is the median value and the box represents the 25 to 75 percentile. The whiskers represent the minimum and the maximum non outlier values and small circles “o” represent the outliers. a-d letters represent significant differences.

Peanut shells showed the highest δ15N values (+1.7 ‰) followed by the delipidized kernels (0.3 ‰), and the lowest values were observed in peanut kernels (0.2 ‰), respectively. No significant differences were observed between whole peanuts and delipidized kernels which is consistent with previous findings (Liu et al., 2018). In terms of δ2H values, more positive values were observed in delipidized kernels (-91.5 ‰) followed by peanut shells (-93.8 ‰), peanut kernels (-186.0 ‰), and the more negative values were observed in peanut oil (-257.8 ‰), respectively. Duncan multiple range (DMR) tests depicted significant differences for different fractions (p < 0.05). A decreasing δ18O trend was observed delipidized kernels > peanut shells > peanut oil > peanut kernels, respectively. All fractions showed individual ability to resolve the geographical origin of peanut samples. The effect of lipid extraction on the δ2H and δ18O values of delipidized peanuts remains unclear due to a limited number of studies.

Multivariate analysis

Analysis of variance across the three regions was applied to determine the influence of factors such as region, fraction and region × fraction on δ13C, δ15N, δ2H and δ18O values (Table 2). All factors showed a significant influence on the stable isotope values. The relative contribution of each factor was evaluated using mean square values. In the case of δ13C, the different fractions explained the maximum variance (76.6 %) followed by different regions (23.2 %), and their interaction (0.1 %), respectively. For δ15N, different regions explained the maximum variance (55.2 %) followed by fractions (34.6 %), and the least well explained was their interaction (8.1 %). In the case of δ2H, the maximum variance was explained by different fractions followed by different regions and their interaction. The relative contribution rate in terms of δ18O was by different regions (87.0 %), fractions (10.3 %), and regions × fractions (2.2 %), respectively. These results are consistent with previous findings where the processing of wheat explained the maximum variance for δ13C and δ2H and geographical origin explained the maximum δ15N variance (Liu et al., 2018).

Table 2.

Combined analysis of variance for carbon (δ13C), nitrogen (δ15N), oxygen (δ18O), and hydrogen (δ2H) values of peanuts.

|

δ13C (‰) |

δ15N (‰) |

δ18O (‰) |

δ2H (‰) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source of variation | df | MS | F | MS | F | MS | F | MS | F |

| Region (R) | 2 | 43.85** | 150.26 | 54.52** | 26.29 | 369.54** | 238.005 | 1343.462** | 25.38 |

| Fraction (F) | 2 | 145.078** | 497.107 | 34.127** | 16.456 | 43.990** | 28.331 | 210123.5** | 3970.15 |

| R × F | 4 | 0.222** | 0.762 | 8.008** | 3.862 | 9.238** | 5.949 | 1097.947** | 20.745 |

| Error | 219 | 0.292 | 2.074 | 1.553 | 52.92 | ||||

Geographical origin classification of peanut by LDA, k-NN and SVM

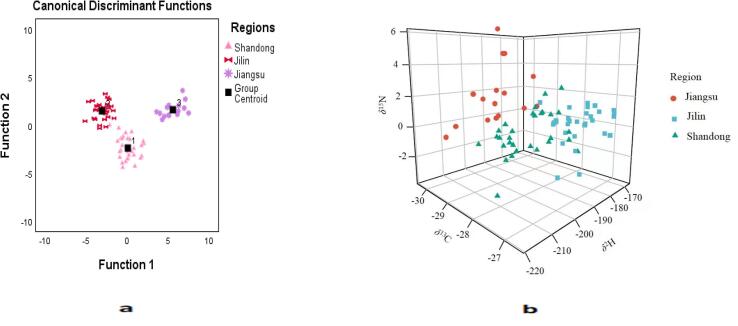

Classification methods based on LDA, k-NN, and SVM were developed and compared for their predictive ability to discriminate the geographical origin of peanut samples using stable isotopes. LDA is broadly applied for the classification of data due to its simplicity and empirical success in finding hidden trends in data. Similarly, SVM and k-NN are the widely used techniques that are developed through supervised learning. SVM can perform well with relatively small data set as it has a regularization parameter which work against over fitting and can effectively deal non-linearly separable data through the kernel trick. k-NN is easy, simple, and low cost algorithm that also performs well with small data sets and multiclass problems (Maione & Barbosa, 2019). To develop most robust model, discrimination capabilities of all these methods were compared. Table 3 summarizes the classification percentages. All fractions were individually used to check their discrimination power and finally-two matrices including peanut kernels and delipidized peanut samples were chosen because of their higher discrimination potential. Initially, linear discriminant analysis (LDA) was performed on the peanut kernel using 76 samples. Thirty samples were sourced from Shandong, 30 from Jilin, and the remaining 16 from Jiangsu. The LDA model correctly classified the origin of 88.2 % of samples and 86.8 % were correctly identified in cross-validation (Table 3). Subsequently, the second matrix (delipidized peanut samples) was used to develop a further LDA model. Two discriminant functions were obtained which were highly statistically significant (Wilk’s ƛ < 0.6). Function 1 explained the maximum variance (81.6 %) of the total variance. The developed model achieved a very high classification rate both in training and cross-validation. Samples were correctly classified with an accuracy rate of 94.7 % which was slightly reduced (92.1 %) in cross-validation. A few samples from Shandong and Jiangsu were misclassified, although Shandong had an accuracy rate of 93.3 % and 6.6 % of samples were misclassified as originating from Jilin and Jiangsu. Similarly, 87.5 % samples from Jiangsu were correctly classified, and 12.5 % samples were misclassified as Shandong, while 100 % samples were correctly classified as originating from Jilin. Delipidized peanut samples had a higher overall discrimination result which accounts for the removal of lipids (peanut oil) which adds a variable isotopic contribution depending on oil content. The geographical origin separation and classification is shown by plotting both discriminant functions (Fig. 3a).

Table 3.

Classification results of LDA, SVM, and k-NN of Peanut geographical origins by using the training and validation set.

| |||||||||

| Origins | Peanut Kernel | Defatted Sample | |||||||

| Predicted | Predicted | ||||||||

| Shandong | Jilin | Jiangsu | Total | Shandong | Jilin | Jiangsu | Total | ||

| Training | Shandong | 27 | 3 | 0 | 30 | 28 | 1 | 1 | 30 |

| Jilin | 3 | 26 | 1 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | |

| Jiangsu | 2 | 0 | 14 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 16 | |

| % correct | 90 | 86.7 | 87.5 | 88.2 | 93.3 | 100 | 87.5 | 94.7 | |

| Validation | Shandong | 2 | 4 | 0 | 30 | 26 | 3 | 1 | 30 |

| Jilin | 3 | 26 | 1 | 30 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 | |

| Jiangsu | 2 | 0 | 14 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 14 | 16 | |

| % correct | 86.7 | 86.7 | 87.5 | 86.8 | 86.7 | 100 | 87.5 | 92.1 | |

| b. k-NN | |||||||||

| Training | Shandong | 21 | 2 | 0 | 23 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 24 |

| Jilin | 1 | 22 | 0 | 23 | 3 | 16 | 0 | 19 | |

| Jiangsu | 4 | 0 | 8 | 12 | 6 | 0 | 4 | 10 | |

| % correct | 91.3 | 95.7 | 66.7 | 87.9 | 95.8 | 84.2 | 40 | 81.1 | |

| Validation | Shandong | 7 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| Jilin | 2 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 0 | 11 | |

| Jiangsu | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 6 | |

| % correct | 100 | 71.4 | 75 | 83.3 | 83.3 | 81.8 | 66.7 | 78.3 | |

| c. SVM | |||||||||

| Training | Shandong | 22 | 2 | 0 | 24 | 23 | 1 | 1 | 25 |

| Jilin | 2 | 22 | 0 | 24 | 2 | 25 | 0 | 27 | |

| Jiangsu | 2 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | |

| % correct | 91.66 | 91.66 | 83.33 | 90 | 92 | 92.5 | 100 | 93.3 | |

| Validation | Shandong | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Jilin | 1 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 | ||

| Jiangsu | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 6 | 8 | |

| % correct | 100 | 83.33 | 100 | 93.7 | 100 | 100 | 75 | 87.5 | |

Fig. 3.

(a) Cross plot of the first two discriminant functions obtained from the linear discriminant analysis of delipidized peanut matrices for different regions. (b) k-NN analysis of peanut kernel using the peanut kernel matrix.

Subsequently, a k-NN model was applied and prior to performing the analysis, the data set was divided into a training set (76 %) to develop a model and a test set (24 %) to calculate its classification performance. The k-NN model achieved the best performance when k = 3. The classification percentages for both the training and validation sets are summarized in Table 3c. The k-NN model achieved a total accuracy of 87.9 % in training and 83.3 % in the validation set, respectively, for the peanut kernels. The total classification percentages for delipidized peanut samples were 81.1 % for the training and 78.3 % for the validation sets, respectively. Fig. 3b depicts the geographical separation of peanut samples generated by the k-NN model. Finally, a SVM model was applied to classify samples according to different geographical origins. A SVM model was run with four types of kernel functions, including linear, power, RBF and sigmoid. The best performance was achieved with the power function. The SVM model achieved a higher classification rate both in the training and test sets. The total classification rates of the peanut kernel samples were 90 % in the training and 93 % in the validation sets, respectively. Similarly, the model achieved a total classification rate for the delipidized peanuts of 93.3 % and 87.5 % in the training and test sets, respectively (Table 3b). This comparison between the different statistical models showed that all the tested models were suitable for discriminating the geographical origin of peanut samples and each model had its own advantages. However, LDA proved to be a more effective and robust method since its classification rates were higher than the other two methods.

Conclusion

In this study, the geographical classification of peanuts and different peanut fractions from three provinces in China was successfully demonstrated using stable isotopes (C, N, H, and O). Peanut processing influenced the δ13C, δ2H, and δ18O values due to diploidization, while the δ15N values were mostly unaffected during processing. Climatic differences explained key isotopic variances between geographical regions, and similar trends were observed across peanut kernel and its fractions for each region. Three different geographical classification models were investigated. LDA had the highest classification ability for the delipidized kernels and SVM had the best model accuracy for the peanut kernel for both the training and validation sets. In general, the delipidized samples resulted in slightly improved classification results. The outcome of this study provides a useful method to verify peanut and peanut product origin in China and improve food safety through increase traceability using stable isotope and chemometric methods.

Author contributions

Syed Abdul Wadood and Yuwei Yuan conceived the idea, Yongzhi Zhang, Syed Abdul Wadood, Jing Nie drafted the manuscript, Chunlin Li analyzed data, Karyne M. Rogers and Yuwei Yuan edited the manuscript. The final version was approved by all authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Crop Varietal Improvement and Insect Pests Control by Nuclear Radiation Project, China; IAEA Coordinated Research Project [Grant No. D52042] and Special Fund of Discipline Construction for Traceability of Agricultural Product (2021-ZAAS). We also thank Zhao Haiyan from college of Food Science and Engineering, Qingdao Agricultural University, No. 700, Changcheng Road, Qingdao 266109, P.R. China for providing the peanut samples.

References

- Anderson K.A., Smith B.W. Effect of Season and Variety on the Differentiation of Geographic Growing Origin of Pistachios by Stable Isotope Profiling. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(5):1747–1752. doi: 10.1021/jf052928m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A.S., Kelly S.D., Woolfe M. Nitrogen isotope composition of organically and conventionally grown crops. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2007;55(7):2664–2670. doi: 10.1021/jf0627726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempo L., Camin F., Paolini M., Micheloni C., Laursen K.H. Multi-isotopic signatures of organic and conventional Italian pasta along the production chain. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2016;51(9):675–683. doi: 10.1002/jms.3816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brescia M.A., Di Martino G., Guillou C., Reniero F., Sacco A., Serra F. Differentiation of the geographical origin of durum wheat semolina samples on the basis of isotopic composition. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2002;16(24):2286–2290. doi: 10.1002/rcm.860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles T., Garten J. Variation in foliar 15N abundance and the avalability of soil nitrogen on walker branch watershed. Ecology. 1993;74(7):2098–2113. [Google Scholar]

- Dansgaard W. Stable isotopes in precipitation. Tellus. 1964;16(4):436–468. doi: 10.3402/tellusa.v16i4.8993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Rijke E., Schoorl J.C., Cerli C., Vonhof H.B., Verdegaal S.J.A., Vivó-Truyols G.…de Koster C.G. The use of δ2H and δ18O isotopic analyses combined with chemometrics as a traceability tool for the geographical origin of bell peppers. Food Chemistry. 2016;204:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.01.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNiro M.J., Epstein S. Mechanism of carbon isotope fractionation associated with lipid synthesis. Science. 1977;197(4300):261–263. doi: 10.1126/science.327543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gat J.R. Oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in the hydrologic cycle. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 1996;24(1):225–262. doi: 10.1146/annurev.earth.24.1.225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graves G.R., Romanek C.S., Rodriguez Navarro A. Stable isotope signature of philopatry and dispersal in a migratory songbird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99(12):8096–8100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082240899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L.X., Xu X.M., Yuan J.P., Wu C.F., Wang J.H. Characterization and authentication of significant Chinese edible oilseed oils by stable carbon isotope analysis. JAOCS, Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society. 2010;87(8):839–848. doi: 10.1007/s11746-010-1564-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kern Z., Hatvani I.G., Czuppon G., Fórizs I., Erdélyi D., Kanduč T.…Vreča P. Isotopic “altitude” and “continental” effects in modern precipitation across the Adriatic-Pannonian region. Water (Switzerland) 2020;12(6) doi: 10.3390/w12061797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krauß S., Vieweg A., Vetter W. Stable isotope signatures (δ2H-, δ13C-, δ15N-values) of walnuts (Juglans regia L.) from different regions in Germany. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2020;100(4):1625–1634. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, K. (2021). Determining the geographical origin of fl axseed based on stable isotopes , fatty acids and antioxidant capacity. July. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.11396. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liu H., Guo B., Zhang B., Zhang Y., Wei S., Li M.…Wei Y. Characterizations of stable carbon and nitrogen isotopic ratios in wheat fractions and their feasibility for geographical traceability: A preliminary study. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2018;69:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2018.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., Cao Z., Wang J., Sun B. Chlorine dioxide fumigation: An effective technology with industrial application potential for lowering aflatoxin content in peanuts and peanut products. Food Control. 2022;136 doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.108847. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Zhi, Zhang, W., Zhang, Y., Chen, T., Shao, S., Zhou, L., Yuan, Y., Xie, T., & Rogers, K. M. (2019). Assuring food safety and traceability of polished rice from different production regions in China and Southeast Asia using chemometric models. Food Control, 99(April 2018), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.12.011.

- Lu Z., Zhang Z., Su Y., Liu C., Shi G. Cultivar variation in morphological response of peanut roots to cadmium stress and its relation to cadmium accumulation. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 2013;91:147–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maione C., Barbosa R.M. Recent applications of multivariate data analysis methods in the authentication of rice and the most analyzed parameters: A review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2019;59(12):1868–1879. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2018.1431763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2019). China statistical yearbook. Beijing: China Statistics Press.

- Post D.M., Layman C.A., Arrington D.A., Takimoto G., Quattrochi J., Montaña C.G. Getting to the fat of the matter: Models, methods and assumptions for dealing with lipids in stable isotope analyses. Oecologia. 2007;152(1):179–189. doi: 10.1007/s00442-006-0630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy D.M., Hall R., Mix A.C., Bonnichsen R. Using stable isotope analysis to obtain dietary profiles from old hair: A case study from Plains Indians. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2005;128(2):444–452. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.20203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokunbi O.S., Fayomi E.T., Sonuga O.S., Tayo G.O. Nutrient composition of five varieties of commonly consumed Nigerian groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) Grasas y Aceites. 2012;63(1):14–18. doi: 10.3989/gya.056611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steele V.J., Stern B., Stott A.W. Olive oil or lard?: Distinguishing plant oils from animal fats in the archeological record of the eastern Mediterranean using gas chromatography/combustion/isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 2010;24(23):3478–3484. doi: 10.1002/rcm.4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulli F., Moreno-Rojas J.M., Messina C.M., Trocino A., Xiccato G., Muñoz-Redondo J.M.…Tibaldi E. The Use of Stable Isotope Ratio Analysis to Trace European Sea Bass (D. labrax) Originating from Different Farming Systems. Animals. 2020;10(11):2042. doi: 10.3390/ani10112042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadood S.A., Boli G., Yimin W. Geographical traceability of wheat and its products using multielement light stable isotopes coupled with chemometrics. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 2019;54(2):178–188. doi: 10.1002/jms.4312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadood S.A., Guo B., Liu H., Wei S., Bao X., Wei Y. Study on the variation of stable isotopic fingerprints of wheat kernel along with milling processing. Food Control. 2018;91:427–433. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.03.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Yang Q., Zhao H. Sub-regional identification of peanuts from Shandong Province of China based on Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy. Food Control. 2021;124(January) doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.107879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Zhang W., Zhang Y., Liu Z., Shao S., Zhou L., Rogers K.M. Differentiating Organically Farmed Rice from Conventional and Green Rice Harvested from an Experimental Field Trial Using Stable Isotopes and Multi-Element Chemometrics. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2018;66(11):2607–2615. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H., Wang F., Yang Q. Origin traceability of peanut kernels based on multi-element fingerprinting combined with multivariate data analysis. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 2020;100(10):4040–4048. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.10449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler H., Osmind C., Stichler W., Trimborn P. Hydrogen Isotope Discrimination in Higher Plants: Correlations with Photosynthetic Pathway and Environment. Planta. 1976;128:85–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00397183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]