NK cells play a critical role in immune surveillance, yet negative regulators of their maturation and function are poorly characterized. Imianowski et al. show that the transcriptional repressor BACH2 restricts NK cell maturation and anti-tumor function, with implications for immunotherapeutic development.

Abstract

Natural killer (NK) cells are critical to immune surveillance against infections and cancer. Their role in immune surveillance requires that NK cells are present within tissues in a quiescent state. Mechanisms by which NK cells remain quiescent in tissues are incompletely elucidated. The transcriptional repressor BACH2 plays a critical role within the adaptive immune system, but its function within innate lymphocytes has been unclear. Here, we show that BACH2 acts as an intrinsic negative regulator of NK cell maturation and function. BACH2 is expressed within developing and mature NK cells and promotes the maintenance of immature NK cells by restricting their maturation in the presence of weak stimulatory signals. Loss of BACH2 within NK cells results in accumulation of activated NK cells with unrestrained cytotoxic function within tissues, which mediate augmented immune surveillance to pulmonary cancer metastasis. These findings establish a critical function of BACH2 as a global negative regulator of innate cytotoxic function and tumor immune surveillance by NK cells.

Introduction

Natural killer (NK) cells are effector lymphocytes of the innate immune system, forming a critical first line of defense against cancer and infection (Vivier et al., 2008). They express an array of germline-encoded receptors enabling them to recognize cellular stress and defects in antigen presentation accompanying cellular infection or transformation (Lanier, 2005). Unlike CD8+ T cells, recognition of cancer by NK cells is independent of neo-antigens, which makes them an attractive target for cancer immunotherapy (Guillerey et al., 2016; Shimasaki et al., 2020). This is important since immune checkpoint inhibitor therapies, which are thought to predominantly target CD8+ T cells, only work in a subset of patients and in a manner correlated with the density of neo-antigenic mutations recognized by CD8+ T cells (Litchfield et al., 2021; Schumacher and Schreiber, 2015). NK cells are therefore mechanistically distinct targets for cancer immunotherapy. Clinical responses to NK cell–targeted immunotherapies have been modest, identifying a need to better understand the molecular mechanisms that restrict NK cell function to improve NK cell therapies (Guillerey et al., 2016).

NK cells exist in a variety of maturation states with distinct functional potential and migratory capacity. In mice, these can be identified according to their expression of the surface markers CD27, CD11b, and Killer Cell Lectin-Like Receptor G1 (KLRG1; Hayakawa and Smyth, 2006). NK cells progressively differentiate from an immature CD27+ CD11b− subset, which possesses the greatest proliferative potential, to a mature CD27− CD11b+ subset, which exhibits high levels of cytotoxic function. A subset of mature NK cells is terminally differentiated, marked by expression of KLRG1 (Chiossone et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2002). These NK cell subsets exhibit differential capacity to degranulate and produce IFN-γ (Vahlne et al., 2008). Human NK cells also exist in functionally heterogeneous states of maturation, with CD56bright CD16dim/− constituting a weakly cytotoxic subset capable of differentiating into the CD56dim CD16bright subsets, representing the major circulating population of human NK cells (Caligiuri, 2008; Michel et al., 2016; Poli et al., 2009).

While cytotoxic NK cell responses to cancer are primarily mediated by functionally mature NK cells (Malaise et al., 2014), tumors are capable of imposing an immature maturation state upon infiltrating NK cells within the tumor microenvironment, which can limit their activity (Krneta et al., 2016), as well as inhibiting NK cell maturation in the bone marrow (BM; Richards et al., 2006). While immature NK cells have reduced cytotoxic function, they have been proposed to form a precursor pool capable of expansion and formation of a memory-like population of cells during NK cell responses (Cerwenka and Lanier, 2016; Kamimura and Lanier, 2015). Therefore, the maturation state of NK cells has consequences for immune homeostasis as well as responses to infection and cancer. Multiple positive regulators of NK cell functional maturation have been defined (Bi and Wang, 2020; Geiger and Sun, 2016), but we lack a complete understanding of intrinsic negative regulators of this process, particularly in relation to the transcriptional program that governs NK cell functional maturation.

BACH2 is a 92-kD transcriptional repressor of the bZip family whose expression is predominantly restricted to lymphocytes (Igarashi et al., 2017; Oyake et al., 1996). In humans, genetic polymorphisms within the BACH2 locus are associated with multiple autoimmune and allergic conditions (Igarashi et al., 2017). Moreover, non-synonymous mutations within BACH2 are associated with a syndrome of primary immunodeficiency and autoimmunity termed BACH2-related immunodeficiency and autoimmunity (Afzali et al., 2017). BACH2 promotes the differentiation of Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells, and Bach2-deficient mice develop spontaneous lethal inflammation due to defective Treg cell development (Kim et al., 2014; Roychoudhuri et al., 2013). In CD8+ T cells, BACH2 promotes memory cell formation by restraining TCR-driven effector programs, engaging in passive transcriptional repression through competition with AP-1 factors for DNA binding (Grant et al., 2020; Roychoudhuri et al., 2016; Yao et al., 2021). In B cells, BACH2 is required for somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination (Muto et al., 2010; Muto et al., 2004). Thus, BACH2 has a well-characterized role in the adaptive immune system, but there is currently no assigned function of BACH2 in innate lymphocytes—something we sought to determine in this study.

Results and discussion

Bach2 is expressed in developing and mature NK cells

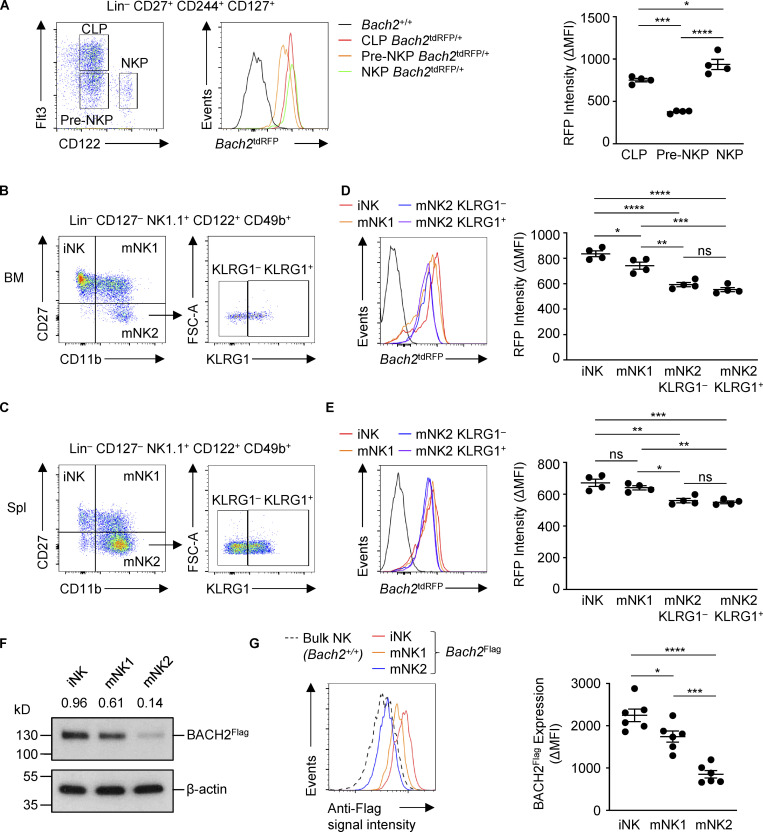

While BACH2 has known roles within the adaptive immune system, whether it functions within NK cells is unclear. We first asked whether Bach2 is expressed in NK cells and their progenitors. To address this, we analyzed Bach2 expression using Bach2tdRFP/+ Bach2 reporter mice, which contain a tandem-dimer RFP (tdRFP) open reading frame under the transcriptional control of endogenous Bach2 regulatory elements (Itoh-Nakadai et al., 2014). Mature NK cells develop in the BM from the common lymphoid progenitor as pre-NK progenitor (pre-NKP) and NK progenitor (NKP) cells. These populations can be distinguished from each other based on their expression of the surface markers Flt3 and CD122 (Geiger and Sun, 2016). Analysis of reporter expression showed that common lymphoid progenitor cells express high levels of Bach2, consistent with previously published findings (Itoh-Nakadai et al., 2014). In contrast, expression of Bach2 was reduced in the pre-NKP population before increasing in the NKP population (Fig. 1 A). An analogous pattern of expression is observed in developing T cells, with the expression of Bach2 being low in double negative and double positive early thymic developmental stages before increasing again in CD4 single-positive (CD4SP) thymocytes (Roychoudhuri et al., 2013).

Figure 1.

Expression of Bach2 in developing and mature NK cells. (A) Flow cytometry of Bach2tdRFP expression by NK cell progenitors within BM (left) and replicate measurements (right). (B and C) Gating strategy for progressive NK cell maturation states from the BM (B) and spleen (C). (D) Bach2tdRFP expression (left) and replicate measurements (right) in NK cell subsets defined in B from mice of indicated genotypes. (E) Bach2tdRFP expression (left) and replicate measurements (right) in the NK cell subsets defined in C from mice of indicated genotypes. (F) Immunoblot analysis of BACH2 expression in NK cell subsets sorted from Bach2Flag animals using an anti-Flag antibody. Numbers show relative expression when compared to an anti–β-actin control. (G) Flow cytometry of Bach2Flag expression in subsets of NK cells from the spleen (left) and replicate measurements (right). Bach2tdRFP expression is plotted as ΔMFI (mean fluorescence intensity), calculated as the difference between RFP signal in samples from Bach2tdRFP/+ animals compared to the mean RFP signal from WT controls (D–E). BACH2Flag expression is plotted as ΔMFI, calculated as the difference between anti-Flag signal in Bach2Flag animals and the mean WT control signal. Data representative of two independent experiments with four to six mice per group (A–E and G). ns, not significant (P > 0.05); *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Ordinary one-way ANOVA (D, E, and G). Bars and error are mean and SEM.

The following subsets of murine NK cells have been defined: iNK (CD27+ CD11b−), mNK1 (CD27+ CD11b+), and mNK2 (CD27− CD11b+; Goh and Huntington, 2017). mNK2 cells can be further subdivided into KLRG1− (mNK2 KLRG1−) and KLRG1+ (mNK2 KLRG1+) populations, the latter representing a terminally differentiated NK cell population (Robbins et al., 2004). We examined the expression of Bach2 in each of these subsets in Bach2tdRFP/+ reporter animals and WT controls (Fig. 1, B and C). All NK cell subsets expressed the Bach2 reporter; however, there was a small but significant decrease in reporter expression between the iNK and mNK1 subsets and the mature mNK2 subset in both the BM (Fig. 1 D) and the spleen (Fig. 1 E), indicating that as NK cells acquire a mature phenotype, their expression of Bach2 decreases. This pattern of expression is consistent with prior observations that BACH2 mRNA is more highly expressed in immature CD56bright human NK cells than in mature CD56dim cells (Collins et al., 2019; Holmes et al., 2021). We also observed a corresponding decrease in the levels of endogenous BACH2 protein expression in mNK2 compared with mNK1 and iNK cells isolated ex vivo from Bach2Flag reporter mice (Fig. 1, F and G; Herndler-Brandstetter et al., 2018). However, decreased expression of Bach2 mRNA in mature compared to immature NK cells was not accompanied by major differences in the overall chromatin accessibility of the Bach2 locus, as evidenced by analysis of previously determined chromatin accessibility profiles of CD27+ CD11b− and CD27− CD11b+ NK cells (Fig. S1 A; Zook et al., 2018).

Figure S1.

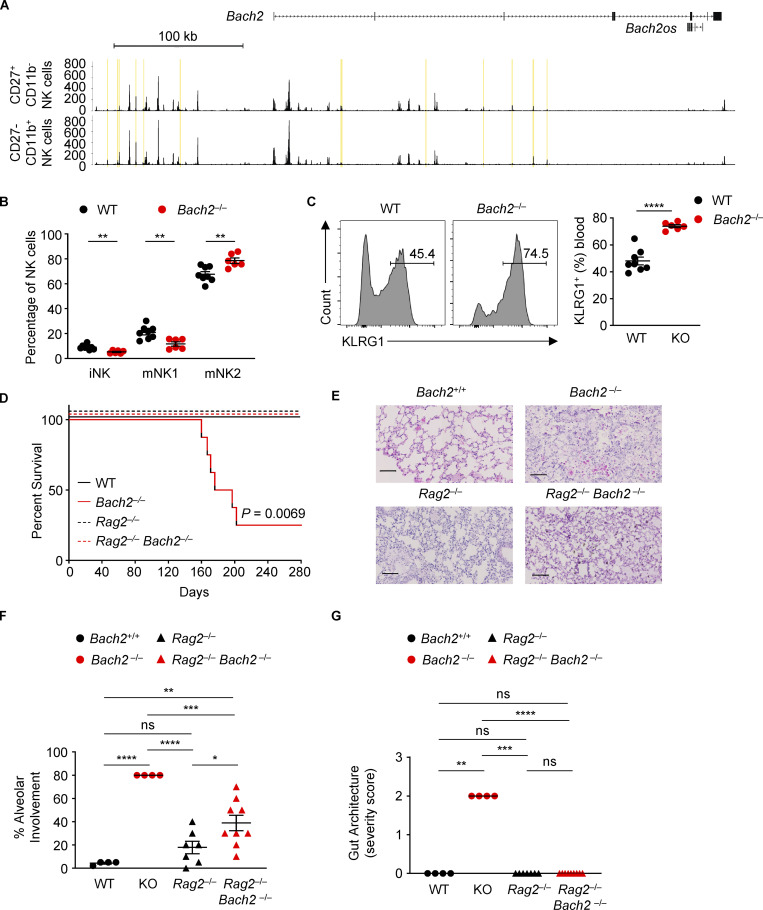

Bach2 deficiency in innate lymphocytes is not associated with a lethal inflammatory phenotype. (A) Genomic tracks depict histograms of normalized reads (y axis) plotted by genome position (x axis) near and within the Bach2 locus for BM-derived CD27+ CD11b− and CD27− CD11b+ NK cells (GSE109517; Zook et al., 2018). Yellow boxes highlight differentially accessible peak regions. (B) Percentages of NK cells of indicated phenotypes within NK cells from blood samples of WT and Bach2−/− mice. (C) Representative histograms (left) and replicate measurements (right) of KLRG1 expression on NK cells in blood samples from mice of indicated genotypes. Numbers in gates indicate percentages. (D) Kaplan-Meier plot showing survival of WT, Bach2−/−, Rag2−/−, and Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals. Logrank test; P = 0.0069. (E) Representative histological images of lungs taken from aged animals of indicated genotypes. Scale bar = 100 µm. (F) Replicate measurements of percentage alveolar involvement of lungs, as shown in E. (G) Histopathology scoring of gut samples taken from aged animals of indicated genotypes. ns, not significant (P > 0.05); *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Data representative of two independent experiments with six to eight mice per group (B–F). Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (B and C). Ordinary one-way ANOVA (F). Kruskal–Wallis test (G). Bars and error are mean and SEM.

BACH2 is a cell-intrinsic negative regulator of NK cell maturation and function

We asked whether systemic deletion of BACH2 is associated with differences in NK cell phenotype or function. Comparing NK cells in Bach2−/− animals with WT littermates, we noted increased frequencies of mNK2 cells, whereas there were decreased frequencies of iNK and mNK1 cells (Fig. S1 B). Additionally, a greater percentage of NK cells from Bach2−/− animals expressed KLRG1 (Fig. S1 C). However, Bach2−/− animals suffer from a lethal inflammatory phenotype attributable to defective Treg cell development (Roychoudhuri et al., 2013), precluding valid interpretation of the lineage-restricted function of BACH2 in NK cells using this experimental system. As NK cells develop independently of the activity of recombination-activating genes (Rag1 and Rag2), we examined the phenotype of NK cells in mice with combined deficiency of Bach2 and Rag2, hypothesizing that these animals would lack the inflammatory defect primarily driven by T cells in Bach2-deficient mice. Overall survival of Rag2−/− Bach2−/− mice was similar to WT or Rag2−/− controls, whereas Bach2−/− animals developed an inflammatory wasting disease requiring euthanasia (Fig. S1 D). H&E staining of lung and gut sections from aged WT, Bach2−/−, Rag2−/−, and Rag2−/− Bach2−/− mice revealed the histopathological features of colitis and pneumonitis found in in Bach2−/− animals were largely mitigated in Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals (Fig. S1, E–G), consistent with previously published findings (Ebina-Shibuya et al., 2017; Roychoudhuri et al., 2013).

We examined the expression of the surface markers CD27 and CD11b and found a higher proportion of NK cells from Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals belong to the mNK2 subset compared to Rag2−/− controls. Conversely, a lower proportion of NK cells belong to the iNK or mNK1 subsets (Fig. S2 A). A higher proportion of NK cells from Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals expressed KLRG1 in the spleen (Fig. S2 B) and lungs (Fig. S2 C). The serine protease Granzyme B is important for NK cell cytotoxic function (Afonina et al., 2010). Splenic Rag2−/− Bach2−/− NK cells showed a significant increase in Granzyme B expression (Fig. S2 D).

Figure S2.

Regulation of NK cell maturation by BACH2. (A) Representative plots of CD27 and CD11b expression (top) and percentages of NK cells of indicated phenotypes (bottom) within NK cells from spleens of Rag−/− and Rag−/− Bach2−/− mice. (B) Representative histograms (left) and replicate measurements (right) of KLRG1 expression on splenic NK cells from mice of indicated genotypes. (C) Representative histograms (left) and replicate measurements (right) of KLRG1 expression on lung NK cells from mice of indicated genotypes. (D) Representative Granzyme B expression (MFI) in splenic NK cells (left) and replicate measurements in spleen and lung NK cells (right) from mice of indicated genotypes. (E) Percentage of NK cells of indicated phenotypes (left) and KLRG1 expression on NK cells (right) within the CD45.1+ CD45.2+ NK compartments from the spleens of WT:WT (black dots) or Bach2−/−:WT (red dots) chimeras. Numbers in gates indicate percentages. Data representative of two independent experiments with five to six mice per group. ns, not significant (P > 0.05); **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Bars and error are mean and SEM.

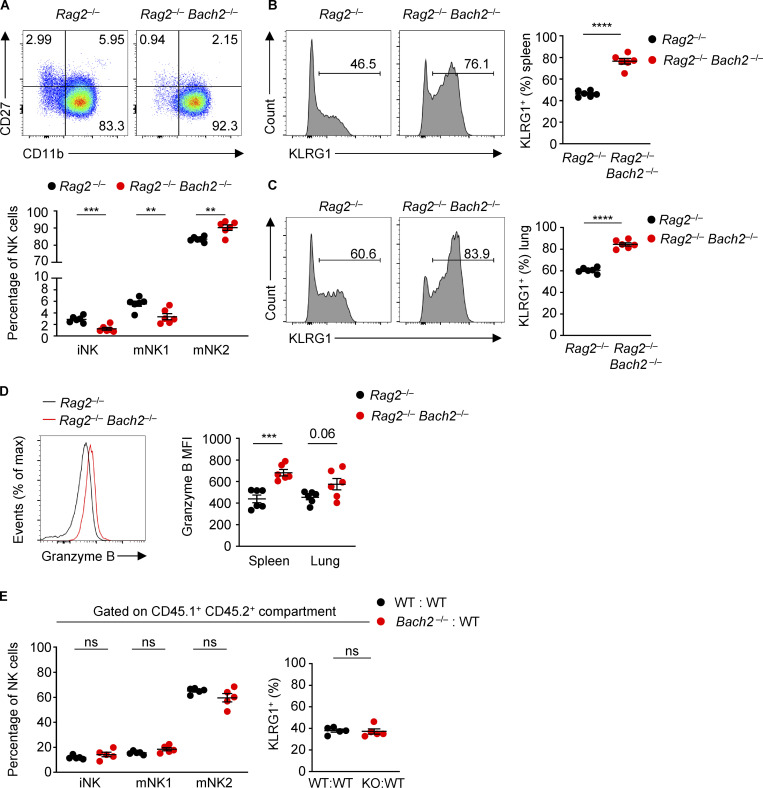

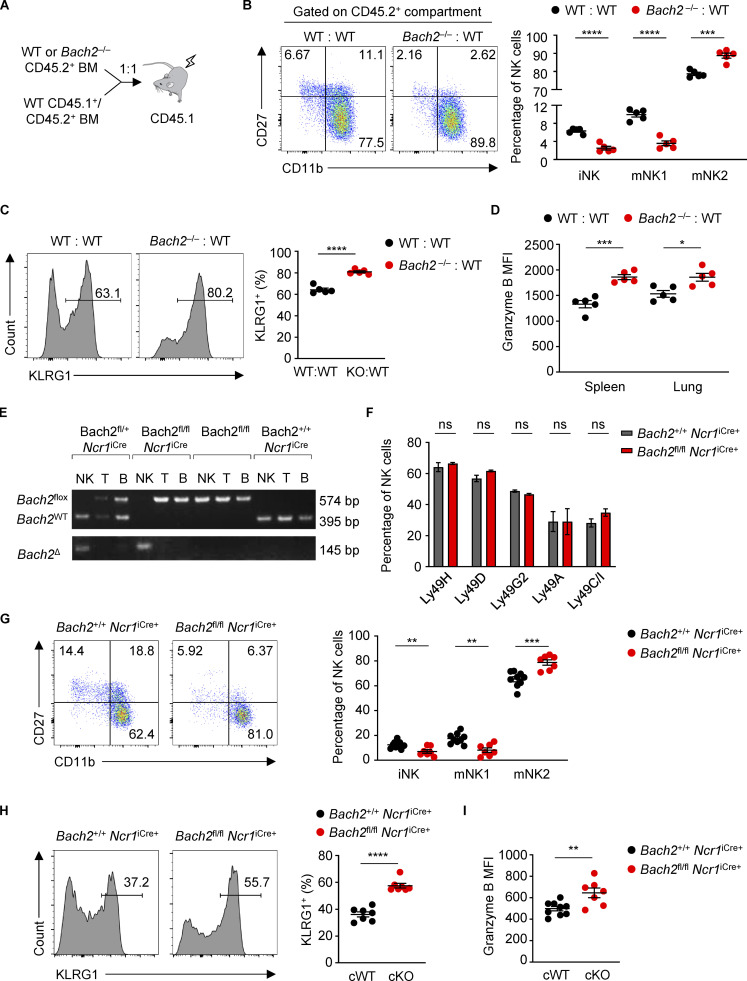

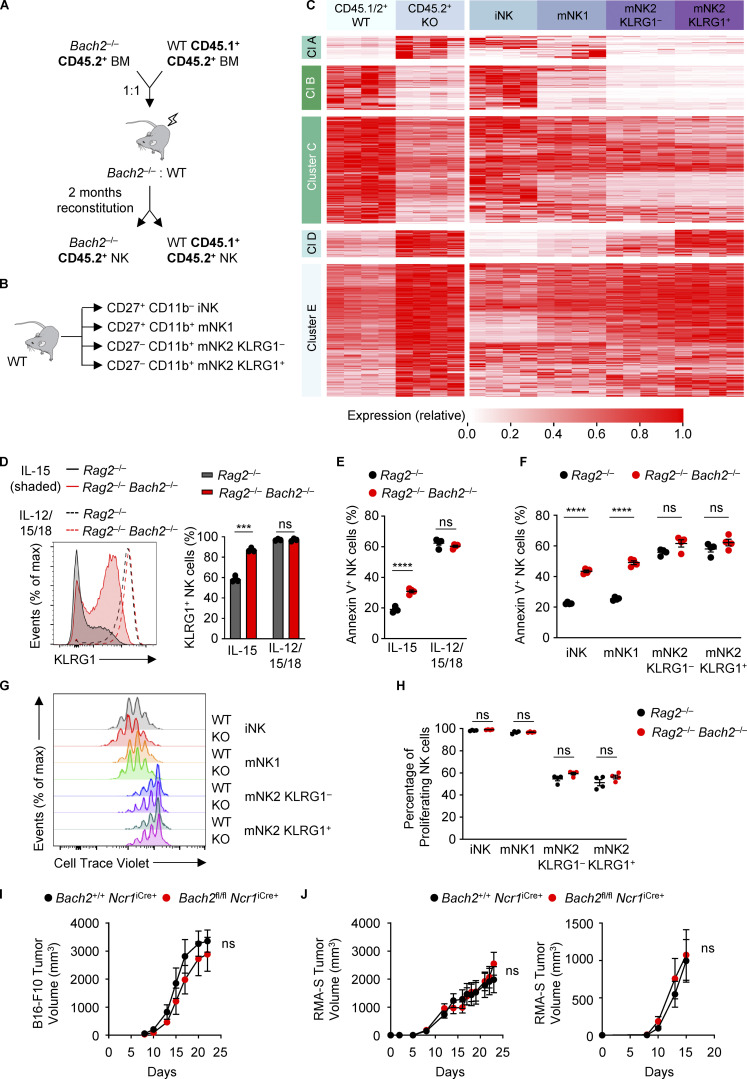

To examine the NK cell–intrinsic function of BACH2 in lymphoreplete hosts, we analyzed mixed BM chimeras (Fig. 2 A). CD45.1+ recipient animals were lethally irradiated and reconstituted with BM cells from congenially distinct WT (CD45.1+ CD45.2+) mice mixed with BM cells from either Bach2−/− or WT controls (CD45.2+). Analysis of the phenotype of splenic NK cells in the CD45.2+ compartment revealed that the proportion of cells belonging to the iNK and mNK1 subsets was reduced in NK cells from CD45.2+ Bach2−/− donor BM compared to those from WT BM, whereas the proportion of mNK2 cells was increased (Fig. 2 B). Additionally, the proportion of NK cells expressing KLRG1 was higher in Bach2−/− NK cells (Fig. 2 C). Importantly, analysis of NK cells from the CD45.1+ CD45.2+ WT compartment revealed no significant difference in the proportion of cells belonging to different NK subsets or expression of KLRG1 (Fig. S2 E), indicating that BACH2 has a cell intrinsic role in restraining the progressive maturation of NK cells. Analysis of CD45.2+ NK cells from the spleen and lung revealed that Bach2−/− NK cells express more Granzyme B compared to WT NK cells (Fig. 2 D). These findings demonstrate a cell-autonomous function of BACH2 in regulating NK cell maturation and function.

Figure 2.

Cell-intrinsic regulation of NK cell maturation by BACH2. (A) Schematic diagram of the generation of competitive mixed BM chimeras. (B) Expression of CD27 and CD11b (left) and percentage of NK cells of indicated phenotypes (right) within the CD45.2+ NK compartments from the spleens of WT:WT (black dots) or Bach2−/−:WT (red dots) chimeras. (C) Representative histograms (left) and replicate measurements (right) of KLRG1 expression on NK cells from the splenic CD45.2+ populations of WT:WT or Bach2−/−:WT chimeras. (D) Replicate measurements of Granzyme B expression (MFI) in spleen and lung NK cells gated from the CD45.2+ population of mixed BM chimeras. (E) PCR genotyping of sorted NK, T, and B cells from spleens of mice with the indicated genotypes. NK cells have cell-specific excision of Bach2 only in mice that also possess the Ncr1iCre gene. (F) Flow cytometry analysis of the expression of Ly49 receptors in Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre+ animals and controls. (G) Representative plots of CD27 and CD11b expression (left) and percentage of NK cells of indicated phenotypes (right) within the spleens of conditional KO animals and relevant controls. (H) Representative histograms (left) and replicate measurements (right) of KLRG1 expression on NK cells from the spleens of mice of indicated genotypes. (I) Granzyme B expression (MFI) of splenic NK cells from mice of indicated genotypes. Numbers in gates indicate percentages. Data representative of two (A–E) and four (G–I) independent experiments with five to seven mice per group. ns, not significant (P > 0.05); *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Bars and error are mean and SEM.

To enable loss-of-function analysis of the NK cell–restricted function of BACH2 in lymphoreplete hosts, we generated Bach2flox Ncr1iCre animals, enabling conditional deletion of Bach2 in NK cells (Kometani et al., 2013; Narni-Mancinelli et al., 2011). PCR analysis of genomic DNA from NK, B, and T cells showed that excision of Bach2 was NK cell specific (Fig. 2 E). No significant differences in the expression of Ly49 receptors were observed (Fig. 2 F). However, NK cells from Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre/+ animals had a smaller proportion of NK cells in the iNK and mNK1 differentiation state and a higher proportion of NK cells in the mNK2 differentiation state (Fig. 2 G). Moreover, the percentage of NK cells expressing KLRG1 was increased (Fig. 2 H), and Granzyme B expression was higher in NK cells from Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre/+ animals compared with Bach2+/+ Ncr1iCre/+ controls (Fig. 2 I).

BACH2 regulates the global transcriptional program of NK cell maturation

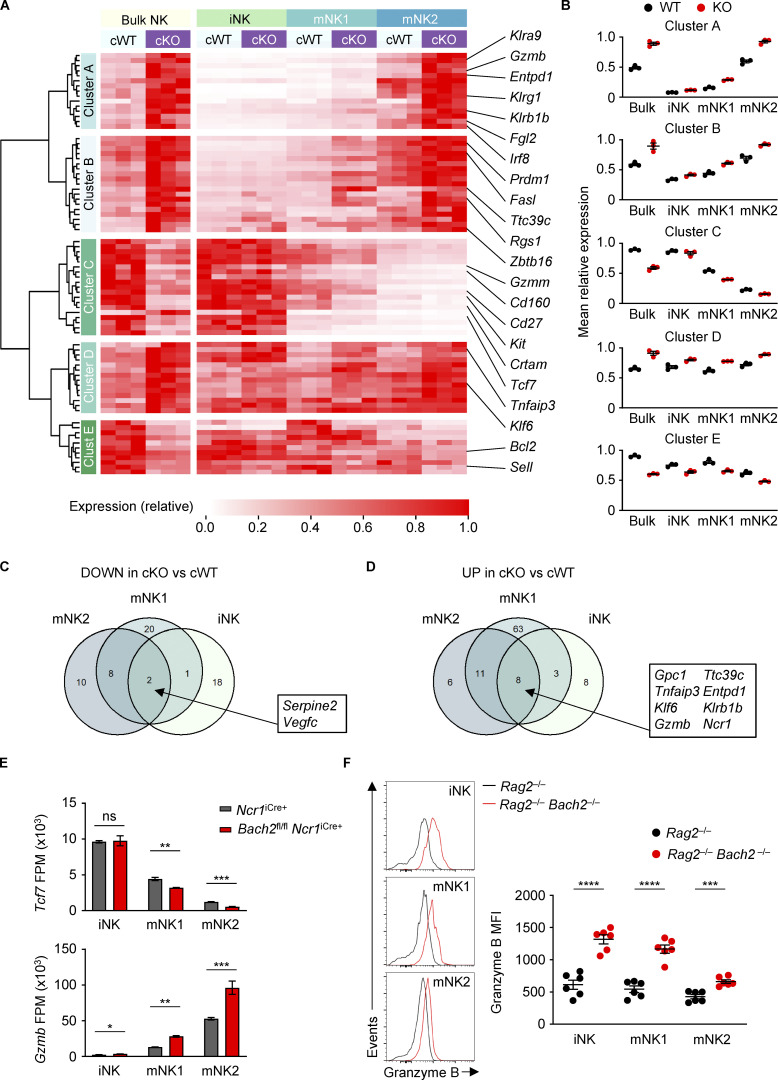

We found that genetic ablation of BACH2 resulted in changes in the expression of phenotypic markers associated with NK cell maturation. We therefore sought to determine the function of BACH2 in regulating the global NK cell transcriptional program. We isolated total NK cells or sub-fractionated iNK, mNK1, and mNK2 NK cell subsets by FACS from the spleens of Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre/+ (cKO) animals and Bach2+/+ Ncr1iCre/+ (cWT) controls and subjected these to massively parallel RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). Supervised hierarchical clustering analysis of RNA-Seq data revealed that the genes differentially expressed between cWT and Bach2-cKO NK cells fell within five main clusters (Fig. 3 A and Table S1). Strikingly, clusters A and B contained transcripts upregulated in Bach2-cKO NK cells whose expression was also increased in mature NK cell subsets; Cluster C contained transcripts downregulated in Bach2-cKO NK cells where expression was decreased in mature NK cell subsets; Cluster D contained a set of transcripts that were upregulated in Bach2-cKO cells whose expression was generally uniform between NK cell subsets, but exhibited genotype-driven differences within these subsets; and Cluster E contained transcripts downregulated among Bach2-cKO NK cells whose expression was only mildly affected by NK cell maturation state but exhibited genotype-driven differences within subsets. This was reflected in the cluster-average expression of genes within each cluster across the groups analyzed (Fig. 3 B). A similar set of gene expression differences were observed upon comparison of WT and Bach2−/− NK cells from mixed chimeric animals and compared to NK cell subsets sorted from WT animals (Fig. S3, A–C; and Table S2), underscoring that the changes observed result from a cell-intrinsic function of BACH2 within NK cells.

Figure 3.

Regulation of the global NK cell maturation program by BACH2. (A) Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes between NK cells sorted from Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre+ (cKO) mice and Ncr1iCre+ (cWT) controls (Padj ≤ 0.2). Also shown is the expression of these genes in NK cell maturation subsets sorted from the same animals. cWT/cKO bulk NK samples and cWT/cKO NK subset gene expression (fragments per million; FPM) independently normalized to row maxima. Genes are hierarchically clustered on the y axis. Data are representative of three biological replicates per group. (B) Average gene expression within the five identified clusters from A in cWT and cKO NK cells and NK cell subsets. (C) Venn diagram showing the overlap between significantly downregulated genes in NK cell maturation subsets sorted from cKO compared to cWT animals. (D) Venn diagram showing the overlap between significantly upregulated genes in NK cell maturation subsets sorted from cKO compared to cWT animals. (E) Normalized expression of selected genes in NK cell subsets sorted from cWT and cKO animals. (F) Representative histograms of Granzyme B expression (left) and replicate measurements of Granzyme B MFI (right) in indicated cell subsets from Rag2−/− and Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals (six mice per group). ns, not significant (P > 0.05); *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. RNA-Seq from three independent biological replicates per genotype is shown. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Bars and error are mean and SEM.

Figure S3.

Transcriptional control of NK cell maturation by BACH2. (A) Schematic diagram of the generation of mixed BM chimeras as a source of WT and Bach2−/− NK cells sorted for RNA-Seq. (B) Schematic diagram showing sorted NK populations from WT mice for RNA-Seq. (C) Heatmap showing differentially expressed genes between WT and Bach2−/− NK cells (Padj ≤ 0.2). Also shown is the expression of these genes in NK cell maturation subsets sorted from WT animals. WT/KO and NK subset gene expression (FPM) independently normalized to row maxima. Genes are hierarchically clustered on the y axis. Data are representative of four biological replicates per group. (D) Representative KLRG1 expression (left) and replicate measurements (right) of NK cells sorted from the spleens of mice with indicated genotypes after 4 d of culture in indicated conditions. (E) Replicate measurements showing the percentage of Annexin V+ NK cells of the indicated genotypes after 4 d in culture with the indicated cytokines. (F) Replicate measurements showing the percentage of Annexin V+ NK cells from indicated subsets and genotypes after sorting by FACS and following 4 d in culture with IL-15. (G) Representative plots showing CTV staining profiles of NK cells sorted into indicated subsets from mice of indicated genotypes after 4 d in culture with IL-15. (H) Replicate measurements showing the percentage of proliferating NK cells (gated as all NK cells not in the highest CTV peak) sorted from mice of indicated genotypes into indicated subsets after 4 d in culture with IL-15. (I) Tumor volume at indicated time point after subcutaneous administration of B16-F10 melanoma cells into animals of indicated genotypes. (J) Tumor volume at indicated time points after subcutaneous administration of RMA-S lymphoma cells into animals of indicated genotypes. Tumor growth after administration of 1 × 106 (left) and 2 × 105 (right) RMA-S cells is shown. RNA-Seq from four independent biological replicates per genotype are shown (C). Data representative of two independent experiments (D–F, I, and J). Data from three or four technical replicates (D–H) or six to eight mice per group (I and J). ns, not significant (P > 0.05); ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test (D–F and H–J). Bars and error are mean and SEM.

Importantly, clusters A, B, and C comprised 67.9% of differentially expressed genes in our analysis of Bach2-cKO animals, which were up- or downregulated both in bulk Bach2-cKO compared with cWT NK cells and changed in a similar direction upon progressive NK cell maturation. Accordingly, a significant proportion of the gene expression changes found between bulk cWT and Bach2-cKO NK cells were abolished upon analysis of cWT and cKO cells when fractionated into NK cell subsets—suggesting that these largely reflected the observed changes in the frequency of NK cell subsets comprising the bulk populations analyzed. This points to a prominent role of BACH2 as a global regulator of NK cell maturation states, with its loss resulting in increased maturation and terminal differentiation of NK cells. However, we also noted the presence of a core set of transcriptional differences between cWT and Bach2-cKO cells, which were present upon analysis of fractionated NK cell subsets, and which were consistent between two or more subsets analyzed (Fig. 3, C and D). These included genes such as Tcf7, which encodes the transcription factor TCF1 associated with lymphocyte stemness, and Gzmb, encoding the cytolytic effector molecule Granzyme B (Fig. 3 E). Consistent with mRNA expression profiles, flow cytometry analysis of Granzyme B expression within splenic NK cells revealed that it is significantly upregulated within iNK, mNK1, and mNK2 subsets when analyzed separately (Fig. 3 F). Thus, in addition to regulating the frequency of NK cells allocated to distinct maturation states, BACH2 plays a further role in controlling the transcriptional and phenotypic properties of distinct NK cell subsets.

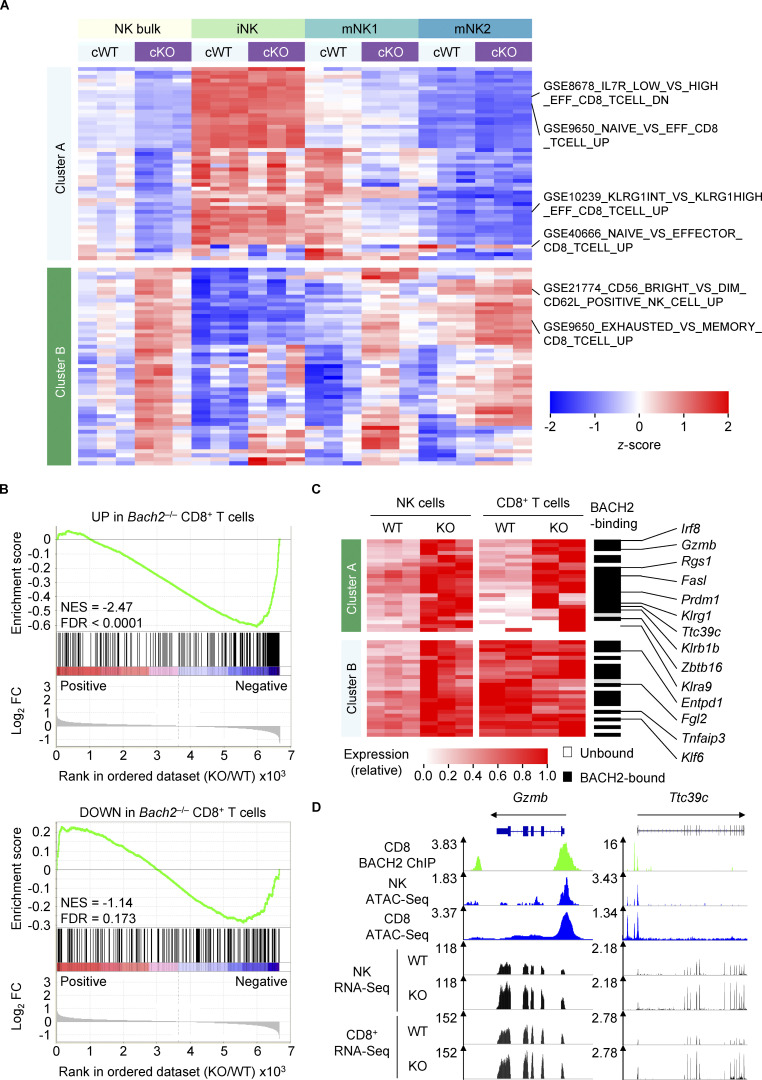

BACH2 regulates a shared transcriptional program in NK cells and CD8+ T cells

NK cells and CD8+ T cells are cytotoxic cells of the innate and adaptive lymphocyte lineages, respectively. There are similarities in the global maturation programs of CD8+ T cells and NK cells, although the molecular basis for their shared differentiation program has been unclear (Lau et al., 2018). Single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) of global gene expression differences between cWT and Bach2-cKO NK cells revealed enrichment of several gene sets involved in CD8+ T cell differentiation (Fig. 4 A and Table S3). In CD8+ T cells, BACH2 restrains effector programs to promote quiescent memory cell differentiation (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016). Given the results of our ssGSEA, we asked whether BACH2 regulates a common set of genes involved in lymphocyte maturation in NK cells and CD8+ T cells. We first examined whether differentially up- and downregulated transcripts in Bach2-deficient CD8+ T cells responding to viral infection ex vivo were enriched within the global gene expression differences between cWT and Bach2-cKO NK cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016). Strikingly, this analysis revealed a highly significant positive enrichment of genes upregulated among Bach2-deficient CD8+ T cells within the global differences in gene expression between Bach2-deficient and -proficient NK cells (Fig. 4 B and Tables S4 and S5).

Figure 4.

BACH2 regulates shared transcriptional programs in NK and CD8+ T cells. (A) ssGSEA of cWT and cKO NK cells and subsets with immunologic gene sets (ImmuneSigDB; Pval < 0.05, |FC| > 1.5). (B) GSEA of differentially upregulated (top) and differentially downregulated (bottom) genes in Bach2−/− CD8+ T cells within the global transcriptional differences between cKO and cWT NK cells. NES, normalized enrichment score; FDR, false discovery rate. (C) Heatmap showing expression of genes which are significantly upregulated in cKO NK cells (Padj ≤ 0.2) and expressed by both NK and CD8+ T cells. Genes with peak-called BACH2-binding sites between 15 kb upstream of the transcription start site and 3 kb downstream of the transcription end site of that gene within CD8+ T cells are indicated. cWT/cKO NK and WT/KO CD8+ T cell gene expression data (reads per million; RPM) independently normalized to row maxima. Genes are hierarchically clustered along the y axis. (D) Representative alignments of ChIP-Seq, ATAC-Seq, and RNA-Seq data at selected loci in indicated cell types, showing increased mRNA expression of genes. RNA-Seq from three independent biological replicates per genotype is shown.

To determine shared targets of BACH2 in NK cells and CD8+ T cells, we examined the expression of specific genes up- or downregulated among Bach2-cKO NK cells in Bach2-deficient vs. WT CD8+ T cells, alongside corresponding BACH2 chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) data showing which of these genes are bound by BACH2 in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4 C). BACH2 is a transcriptional repressor, and its target genes are typically upregulated in Bach2-deficient cells (Igarashi et al., 2017). Supervised hierarchical clustering analysis of upregulated transcripts in NK cells revealed two clusters of genes. Cluster A genes were upregulated in both Bach2-cKO NK cells and CD8+ T cells, and 75% of these genes were bound directly by BACH2 in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4 C). This included Gzmb and Ttc39c, which were upregulated in both Bach2-deficient CD8+ T cells and NK cells, shared a similar distribution of accessible chromatin in both CD8+ T cells and NK cells, and were bound by BACH2 in CD8+ T cells (Fig. 4 D). Thus, BACH2 regulates a partially shared transcriptional program within cytotoxic cells of the innate and adaptive lymphocyte system.

BACH2 maintains NK cell quiescence under weak levels of stimulatory signaling

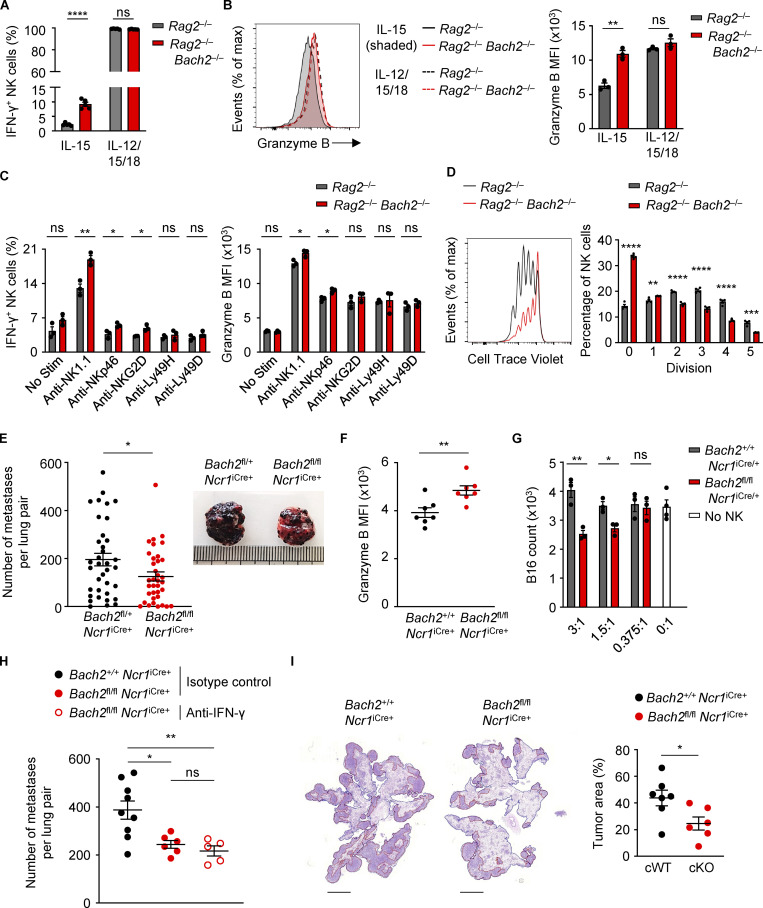

We wished to examine whether repression of NK cell function by BACH2 is contextual. We cultured sorted WT and Bach2-deficient NK cells with IL-15 alone or in combination with IL-12 and IL-18. We found an increase in the percentage of IFN-γ+ NK cells under IL-15 stimulation, a difference which was lost at the high levels of stimulation caused by IL-12 and IL-18 signaling (Fig. 5 A). Similarly, while Bach2-deficient NK cells expressed more Granzyme B compared to controls in the presence of IL-15, this difference was lost upon stimulation of cells with IL-15, IL-12, and IL-18 (Fig. 5 B). Furthermore, stimulation with IL-15, IL-12 and IL-18 resulted in a large proportion of cells expressing KLRG1 regardless of genotype, compared to a genotype-driven difference in its expression when cells were cultured only with IL-15 (Fig. S3 D). Stimulation of the NK cell activating receptors NK1.1, NKp46, and NKG2D also resulted in increased IFN-γ expression by Bach2-deficient NK cells and stimulation of NK1.1 and NKp46 resulted in increased Granzyme B expression, whereas culture for 16 h in media alone did not (Fig. 5 C). The loss of a genotype-driven difference in Granzyme B after brief culture in vitro compared with the differences observed directly ex vivo suggests that BACH2 restricts NK cell activation driven by tonic signals present under homeostatic conditions in vivo. Collectively, these findings show that BACH2 is a contextual regulator of NK cell quiescence, restraining NK cell activation and function under homeostatic conditions and weak stimulatory signaling.

Figure 5.

BACH2 maintains NK cell quiescence and restricts immune surveillance to pulmonary metastasis. (A) Replicate measurements of the percentage of IFN-γ+ NK cells sorted from the spleens of mice with indicated genotypes after 4 d of culture in indicated conditions. (B) Representative Granzyme B expression (MFI; left) and replicate measurements (right) of NK cells sorted from the spleens of mice with indicated genotypes after 4 d of culture in indicated conditions. (C) Replicate measurements of the percentage of IFN-γ+ NK cells (left) and NK cell Granzyme B expression (right) after sorting from the spleens of mice with indicated genotypes and 16 h of culture in indicated conditions. (D) Representative plot (left) showing CTV staining and replicate measurements (right) of the percentage of NK cells at each stage of division after isolation from the spleens of Rag2−/− and Rag2−/− Bach2−/− mice by FACS and following 4 d in culture with IL-15. (E) Frequency of B16 metastases on the lobular surfaces (left) and representative photographs (right) of lungs from mice of indicated genotypes 16 d after intravenous injection of B16 cells. Data pooled from five representative experiments with six to eight mice per group. (F) Granzyme B expression (MFI) of lung NK cells from conditional KO animals and relevant controls 16 d following intravenous injection of B16 cells. (G) Counts of B16 cells after overnight co-culture in indicated ratios with NK cells sorted from mice of indicated genotypes. (H) Frequency of B16 metastases on the pleural surfaces of lungs from mice of indicated genotypes and treated intraperitoneally with the indicated antibodies 15 d following intravenous injection of B16 cells. (I) Representative images (left) and quantification of relative tumor area to total lung area (right) of metastases within lungs of mice of indicated genotypes 13 d after intravenous administration of syngeneic LL/2 cells. Relative percentage of total cross-sectional lung area occupied by cancer metastases is shown. Scale bar = 3,000 µm. Data representative of two independent experiments (A, B, D, G, and I). Data from three to five technical replicates (A–D and G) or five to nine mice per group (F–I). ns, not significant (P > 0.05); *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test. Bars and error are mean and SEM.

Since the proliferative potential of NK cell subsets decreases as they progressively mature (Chiossone et al., 2009), we wanted to investigate the proliferative capacity of Bach2-deficient NK cells. NK cells from Rag2−/− and Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals were sorted and stained using Cell Trace Violet (CTV) and cultured in IL-15 for 4 d. Analysis of CTV peaks by flow cytometry showed that NK cells from Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals were significantly less proliferative in vitro, with a higher proportion of cells in earlier division stages than Rag2−/− controls (Fig. 5 D). We also asked whether Bach2-deficient NK cells are more susceptible to apoptosis. Annexin V can be used to detect apoptotic cells through its ability to bind to phosphatidylserine on their surface. Stimulation of NK cells with IL-15 resulted in higher frequencies of apoptotic cells but this difference was lost upon stimulation with IL-12 and IL-18 in addition to IL-15 (Fig. S3 E).

Given that BACH2 globally regulates the NK cell maturation program, we wanted to test whether the differences in proliferative potential and apoptosis of WT and Bach2-deficient NK cells were attributable to differences in their global maturation state. To assess this, we sorted WT and Bach2-deficient NK cells into iNK, mNK1, mNK2 KLRG1−, and mNK2 KLRG1+ subfractions, plated them in IL-15 at equal density and analyzed the percentage of apoptotic cells in each subset after 4 d in culture. We found that there were minimal differences in the frequency of Annexin V+ cells between genotypes in KLRG1− and KLRG1+ mNK2 cells, but there was a marked increase in Annexin V+ NK cells among iNK and mNK1 cells from Bach2-deficient animals (Fig. S3 F). This suggests that BACH2 promotes the survival of quiescent iNK and mNK1 cells. In contrast, when analyzing the proliferative potential of individually sorted subsets in IL-15, we found that the CTV profiles of each subset did not show genotype-driven differences (Fig. S3 G). We also observed no difference in the percentage of proliferating cells between genotypes for each subset of NK cells examined (Fig. S3 H). Therefore, the reduced proliferation of bulk Bach2-deficient NK cells is a reflection of their advanced differentiation state rather than an intrinsic role for BACH2 in regulating proliferation.

BACH2 restricts NK-mediated immunosurveillance to cancer metastasis

We asked whether increased NK cell maturation corresponds to increased tumor immunosurveillance within the tissues of animals lacking NK cell–restricted BACH2 expression. NK cells make up 10–20% of all lung-resident lymphocytes and are critically required for elimination of cancer metastases (Lopez-Soto et al., 2017). To test the NK cell–restricted function of BACH2 in immunity to lung metastases, we intravenously injected syngeneic B16-F10 melanoma cells and counted the number of metastatic deposits on the pleural surfaces of lungs after 16 d. We found a significantly reduced number of B16 deposits in the lungs of Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre/+ animals than controls (Fig. 5 E), demonstrating that BACH2 negatively regulates NK cell–mediated anti-tumor immunity. Accordingly, we observed increased Granzyme B expression within NK cells from B16-F10 tumor-bearing lungs of Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre/+ animals (Fig. 5 F). Consistently, whereas NK cells from lungs of cWT animals exhibited minimal cytotoxic activity when co-cultured with B16-F10 tumor cells in vitro, NK cells from cKO animals displayed significantly greater killing activity (Fig. 5 G). Moreover, treatment of animals with anti–IFN-γ neutralizing antibodies did not significantly alter the number of B16-F10 deposits in conditional KO animals, suggesting minimal involvement for IFN-γ in the enhanced anti-metastatic response of Bach2-cKO NK cells in vivo (Fig. 5 H). In contrast, we did not detect significant differences in the progression of subcutaneously implanted B16-F10 tumors (Fig. S3 I) or RMA-S tumors (Fig. S3 J). Consistent with the increased capacity of NK cells to clear metastatic deposits, we also observed an increase in NK cell–mediated immunity upon NK cell–restricted loss of BACH2 in the LL/2 intravenous lung metastasis model (Fig. 5 I). These experiments reveal a function of BACH2 in limiting NK cell–mediated immunosurveillance to pulmonary cancer metastasis.

Collectively, these findings show that BACH2 acts as an intrinsic negative regulator of NK cell maturation and function. BACH2 is expressed within developing and lineage-committed NK cells. Loss of BACH2 within NK cells results in accumulation of activated NK cells with unrestrained cytotoxic function, which mediate augmented immune surveillance to pulmonary cancer metastasis. We found that BACH2 regulates a partially shared transcriptional program in NK cells and CD8+ T cells, revealing a fundamental molecular analogy between the differentiation programs of these two cytotoxic lymphoid lineages. Although beyond the scope of this study, it will be important to assess whether BACH2 functions in human NK cells to influence their maturation state, and if NK cell dysfunction is associated with diseases associated with BACH2 loss-of-function (BACH2-related immunodeficiency and autoimmunity; Afzali et al., 2017) or polymorphisms (Igarashi et al., 2017). It will be important to test whether genetic manipulation of BACH2 can promote the function of NK cells in the adoptive cell therapy context. It would also be useful to compare BACH2-binding spectra in mouse and human NK cells (Holmes et al., 2021).

Further work is also required to understand the nature of the activating signals and signal transduction machinery that BACH2 regulates in NK cells. In CD8+ T cells, BACH2 controls TCR-driven transcriptional programs by restraining access of Jun family AP-1 transcription factors to the genomic 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate response elements to which they bind (Igarashi et al., 2017; Roychoudhuri et al., 2016). Recruitment to these 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate response elements occurs when members of the Jun family are phosphorylated in response to TCR signaling. NK cells do not signal through the TCR but rather integrate activating and inhibitory signals to produce a cytotoxic response (Lanier, 2005). A number of activating NK receptors use adaptor proteins containing immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motifs (ITAMs), thus sharing a common signaling mechanism with T and B cell antigen receptors. These include NKp46, which plays a critical role in NK cell recognition of B16 melanoma (Glasner et al., 2012) and Lewis lung carcinoma tumors (Shi et al., 2018), and NKG2D, which plays a role in recognition of Lewis lung carcinoma tumors (Shi et al., 2018). NKp46 associates with adaptors FcεRIγ and/or CD3ζ, whereas NKG2D associates with the adaptor protein DAP10 in NK cells (Diefenbach et al., 2002; Gilfillan et al., 2002; Pessino et al., 1998; Wu et al., 1999). Upon ligand recognition, phosphorylation of ITAM domains in these adaptor proteins results in a cascade of downstream signaling events leading to MAPK activation and translocation of AP-1 factors into the nucleus, allowing for induction of genes associated with NK cell activation. It is plausible that by competing with AP-1 factors for genomic binding, BACH2 represses NK cell activation driven by ITAM-coupled NK receptors, including not only NKp46 and NKG2D but also NK1.1. Importantly, in vitro stimulation with antibodies directed against NKp46, NKG2D, and NK1.1 resulted in greater induction of IFN-γ by Bach2-deficient than WT NK cells, supporting this hypothesis.

Our findings reveal a function of BACH2 within the innate lymphocyte lineage, and suggest that therapeutically enhancing the maturation state of NK cells under basal conditions within tissues augments their ability to respond to metastasis. This has implications for development of anti-metastatic immunotherapies.

Materials and methods

Mice and reagents

Ptprca (CD45.1) congenic mice and Rag2−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Bach2−/−, Bach2tdRFP, Bach2flox, Bach2Flag, and Ncr1tm1.1(icre)Viv mice were generated as previously described (Herndler-Brandstetter et al., 2018; Itoh-Nakadai et al., 2014; Kometani et al., 2013; Muto et al., 2004; Narni-Mancinelli et al., 2011). Littermate controls or age- and sex-matched animals were used in experiments as indicated. All mice were housed at the University of Cambridge University Biomedical Services Gurdon facility or the Babraham Institute Biological Support Unit. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with UK Home Office guidelines and were approved by the Babraham Institute and/or University of Cambridge Animal Welfare and Ethics Review Board. Mice were genotyped by Transnetyx. BM from two congenically distinct WT sources or WT and Bach2−/− BM was mixed in a 1:1 ratio and used to reconstitute lethally irradiated hosts (1,000 Rads) for 8–10 wk before NK cells were analyzed by flow cytometry or isolated by FACS for RNA-Seq.

Histopathological analysis of tissues

Lungs and guts taken from aged animals were fixed in 4% formalin before being embedded in paraffin. Sections were taken from the center of the lungs and from a cross-section of the guts and stained with H&E. Slides were blinded and independently scored for pathological features.

B16-F10 tumor metastasis model

B16-F10 murine melanoma cells were purchased from Kerafast and passaged in DMEM (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Mice were injected intravenously with 2 × 105 cells in 150 μl HBSS, and lungs were dissected on day 16 for metastasis enumeration and subsequent analysis by flow cytometry. IFN-γ neutralizing or IgG isotype control antibodies (BioXCell) were injected intraperitoneally every 3–4 d at a dose of 200 µg per injection, starting at day −1.

LL/2 tumor metastasis model

LL/2 murine carcinoma cells were passaged in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Mice were injected with 2 × 106 cells in 150 μl PBS, and lungs were dissected on day 13. Lungs were fixed in 4% formalin before being embedded in paraffin. Sections were taken from the center of the lungs and stained with H&E. Slide images were taken using a Pannoramic digital slide scanner (3DHistech) and analyzed using QuPath Software. Tumor burden was calculated as a percentage of total tissue area for each sample.

B16-F10 subcutaneous tumor model

B16-F10 murine melanoma cells were passaged in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Mice were injected subcutaneously into one flank with 1.25 × 105 cells in 100 μl PBS. Tumor growth was assessed by taking length and width measurements three times a week starting from day 7 after injection. Tumor volume was calculated as length × width2, and mice were culled as they reached severity limits for tumor size.

RMA-S subcutaneous tumor model

RMA-S murine lymphoma cells were passaged in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. Mice were injected subcutaneously with 1 × 106 or 2 × 105 cells in 100 μl PBS into each flank, and tumor growth was assessed by taking length and width measurements three times a week starting from day 3 after injection. Tumor volume was calculated as length × width2, and mice were culled as they reached severity limits for tumor size.

Flow cytometry

Single-cell suspensions from lymphoid tissues were prepared by mechanical dissociation through 40-µM cell strainers (BD Biosciences). Lungs were minced in media containing 20 µg/ml DNase I (Roche) and 1 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated with agitation at 37°C for 30 min before also being dissociated through 40-µM cell strainers. Erythrocytes were lysed using ice cold ACK Lysing Buffer (Gibco) for 60 s. Cells requiring intracellular staining of cytokines were stimulated prior to flow cytometry analysis using PMA, ionomycin, brefeldin A, and monensin for 4 h in complete RPMI 1640 (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Viable cells were discriminated by first staining alone with Zombie UV fixable viability dye (Biolegend) or eFluor 780 fixable viability dye (eBioscience) in PBS, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then incubated with specific surface antibodies (diluted 1/200) on ice for 25 min in FACS buffer, in the presence of 2.4G2 monoclonal antibodies to block FcγR binding. Cell surface phosphatidylserine was labeled using the eBioscience Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Set (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For intracellular staining, the eBioscience Foxp3/Transcription Factor Staining Buffer Set (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions followed by intracellular staining with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for 40 min. Samples were analyzed using the BD LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences) or Beckman CytoFLEX (Beckman Coulter), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar LLC).

Antibodies used for flow cytometry are listed as follows: anti-CD45.1—SB 600, APC or ef506 (A20), anti-CD45.2—ef506 (104), anti-CD3e—FITC (145-2C11), anti-CD5—FITC (53-7.3), anti-CD8a—FITC (53-6.7), anti-CD19—FITC (1D3), anti-CD11c—FITC (N418), anti-Ly6G/C (Gr-1)—FITC (RB6-8C5), anti-Ter-119—FITC (TER119), anti-Fcer1a—FITC (Mar-01), anti-B220—FITC, APC-ef780 or PerCp-Cy5.5 (RA3-6B2), anti-TCRβ—FITC or PerCp-Cy5.5 (H57-597), anti-CD127—PE-cf594 or BV421 (SB/199), anti-CD27—PerCp-Cy5.5 or PE (LG.3A10), anti-CD244—BV650 (2B4), anti-NK1.1—FITC, PE-Cy7 or BV650 (PK136), anti-CD122—PE-Cy7 (TM-β1), anti-CD11b—FITC or BV421 (M1/70), anti-Flt3—APC (A2F10), anti-KLRG1—APC or BV785 (2F1), anti-CD49b—FITC or APC-ef780 (DX5), anti-CD49a—BV711 (Ha31/8), anti–Granzyme B—PE (NGZB), anti–IFN-γ—ef450 or PE-Cy7 (XMG1.2), anti–Ki-67—PE-Cy7 (SolA15), anti-DYKDDDDK—BV421 (L5), anti-Ly49H—PE-Cy7 (3D10), anti-Ly49D—PE (4E5), anti-Ly49G2—FITC (4D11), anti-Ly49A—PE (A1), and anti-Ly49C/I—FITC (5E6). The lineage gate included the following markers: CD3e, CD5, CD8a, CD19, Ly6G/C, Ter-119, Fcer1a, and B220 or TCRβ and B220.

FACS

Pre-enrichment of NK cells from single-cell suspensions was done using the MagniSort Mouse NK cell Enrichment Kit (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Any markers required for cell sorting were stained using flow cytometry cell surface antibodies (detailed below), diluted 1/200, while cell suspensions were being labeled with the Enrichment Antibody Cocktail from the kit. Cells were filtered again and resuspended in RPMI 1640 containing DAPI for live/dead discrimination before sorting. Cell sorting was performed using a BD Fusion or Aria instrument (BD Biosciences). Cells were sorted into solutions of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 25% FBS (Sigma-Aldrich) before being prepared for experiments as described below.

In vitro NK cell proliferation assays

Splenic NK cells were purified from Rag2−/− and Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals by total NK cell enrichment followed by FACS, as described above. Bulk NK cells were either sorted solely according to CD49b expression or CD49b+ NK cells were further sorted according to NK subsets: iNK (CD27+ CD11b−), mNK1 (CD27+ CD11b+), mNK2 KLRG1− (CD27− CD11b+ KLRG1−), or mNK2 KLRG1+ (CD27− CD11b+ KLRG1+). The sorted cell populations were then stained with CTV (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then cultured at 50,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate in RPMI 1640 complete medium with 50 ng/ml IL-15 (Peprotech) alone or in combination with 2 ng/ml IL-12 (Peprotech) and 50 ng/ml IL-18 (R&D Systems, Bio-Techne) for 4 d at 37°C in 5% CO2. Before analysis by flow cytometry, cells were first stained with eFluor 780 fixable viability dye then surface flow cytometry antibodies, including Annexin V (PE-Cy7) to analyze apoptotic cells. Data were analyzed on FlowJo.

In vitro NK cell stimulation assays

Splenic NK cells (CD49b+) were purified from Rag2−/− and Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals by total NK cell enrichment followed by FACS, as described above. Cells were then cultured at 100,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate in RPMI 1640 complete medium with 50 ng/ml IL-15 alone or in combination with 2 ng/ml IL-12 and 50 ng/ml IL-18 for 4 d at 37°C in 5% CO2. NK-activating receptors (NK1.1, NKp46, NKG2D, Ly49D from Biolegend; Ly49H from eBioscience) were plate-bound at a density of 5 ng/ml 24 h prior to NK stimulation. For the last 4 h of culture, brefeldin A was added to block cytokine transport and allow for intracellular staining. Cells were then stained for flow cytometry as described above and data were analyzed on FlowJo.

In vitro NK cell cytotoxicity assays

Lungs dissected from Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre/+ and Bach2+/+ Ncr1iCre/+ animals were digested in media containing 20 µg/ml DNase I (Roche) and 1 mg/ml collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated with agitation at 37°C for 30 min before dissociation through 40-µM cell strainers. The resulting single-cell suspensions were incubated with ACK lysing buffer (Gibco) for 3 min. NK cells (CD49b+) were then purified by total NK cell enrichment followed by FACS, as described above. B16-F10 cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate before sorted NK cells were added at the indicated ratios in RPMI-1640 complete medium containing 50 ng/ml IL-15. Counts of B16-F10 cells were assessed by flow cytometry after 16 h of incubation, and the data were analyzed on FlowJo.

DNA isolation and PCR genotyping

NK, B, and T cell populations were sorted by FACS from the spleens of mice with the following genotypes: Bach2fl/+ Ncr1iCre/+, Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre/+, Bach2fl/fl Ncr1WT, and Bach2+/+ Ncr1iCre/+. DNA was isolated from these cell populations using the QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. DNA and primers were prepared for PCR using the MyTaq Red Mix (Bioline) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All PCR reactions were run on a Bio-Rad T100 Thermal Cycler using the following primers: Bach2flox, 5′-CCTTACTGGATTCGGATGAGAAGCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTCTGTACACAGTGGGATCCACGGG-3′ (reverse); Bach2excised, 5′-CTCACTATAGGGTTCGAGGAAGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-GTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCGG-3′ (reverse). Amplicons were visualized by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Immunoblot of BACH2-Flag in NK cell subsets

Splenic NK cells were purified from Bach2Flag animals by total NK cell enrichment followed by FACS, as described above. CD49b+ NK cells were sorted into three subset populations according to expression of the following surface markers: iNK (CD27+ CD11b−), mNK1 (CD27+ CD11b+), or mNK2 (CD27− CD11b+). Samples were lysed in Pierce RIPA Buffer containing cOmplete Mini protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche). The blots were probed with the primary antibodies anti-Flag M2 (Sigma-Aldrich) and an anti–β-actin control (Sigma-Aldrich). The secondary antibody was HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Bio-Rad). Blots were imaged and resultant bands quantified using ImageJ.

RNA-Seq analysis

Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes from WT, Bach2+/+ Ncr1iCre/+ (cWT), Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre/+ (cKO), or chimeric animals were purified by NK cell enrichment and FACS. NK cells (CD49b+ NK1.1+) from WT animals were sorted into the following groups: iNK (CD27+ CD11b−), mNK1 (CD27+ CD11b+), mNK2 KLRG1− (CD27− CD11b+ KLRG1−), or mNK2 KLRG1+ (CD27− CD11b+ KLRG1+). NK cells (CD49b+ NK1.1+) from chimeric animals were sorted into two groups depending on congenic marker expression: WT (CD45.1+ CD45.2+), KO (CD45.2+). NK cells (Lin− CD49b+ NK1.1+) from cWT and cKO animals were sorted into the following groups: CD49b+ NK bulk, iNK (CD27+ CD11b−), mNK1 (CD27+ CD11b+), and mNK2 (CD27− CD11b+). Staining for FACS was done in the presence of 2.4G2 monoclonal antibodies to block FcγR binding. The lineage gate included CD3e, CD19, F4/80, and CD11c antibodies. All samples were stored in 40 μl RNAlater Stabilization solution was at −80°C. Processing of samples was performed using the QIAshredder Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA was then extracted using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA libraries were prepared using the SmartSeq2 protocol on an automated Hamilton NGS-STAR library preparation system and sequenced using a HiSeq 2500 System (Illumina). The FastQ files were then subjected to quality control using FastQC and then alignment to the NCBIM37 Mus musculus genome annotation using the STAR workflow. Also aligned to the same genome assembly was previously published RNA-Seq data from WT and Bach2-deficient CD8+ T cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016). Differential gene expression analysis was performed using DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014), and differentially expressed genes were further analyzed and visualized using R. Expression heatmaps were generated with the R package pheatmap. RNA-Seq data are deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus under accession no. GSE214128.

Comparison of NK cell assay for transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC-Seq) and RNA-Seq with CD8+ T cell ChIP-Seq data

Single-cell suspensions of splenocytes from Bach2fl/fl animals were purified by NK cell enrichment and FACS. CD49b+ NK1.1+ NK cells were sorted from these samples and then subjected to ATAC-Seq as previously described (Buenrostro et al., 2013). ATAC-Seq reads were trimmed using Trim Galore (v0.4.4) using default parameters to remove standard Illumina adapter sequences. Reads were mapped to the mouse NCBIM37 genome assembly using Bowtie2 v2.3.2 with default parameters. TDF files for analysis in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) genome browser (Broad Institute) were generated using Samtools v1.9 and Igvtools v2.3.26. TDF files were also generated from WT and Bach2−/− NK and CD8+ T cell RNA-Seq reads described above. These data were compared with previously published ATAC-Seq and BACH2 ChIP-Seq data from CD8+ T cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016). Data were aligned on IGV for visualization of ATAC-Seq peaks and RNA expression in NK and CD8+ T cells at BACH2-binding sites.

Analysis of chromatin openness at the Bach2 locus in different stages of murine NK cell maturation

FASTQ files of ATAC-seq data assayed from BM-derived NK cell subsets (Zook et al., 2018) were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE109517). Trimming, alignment, peak calling, atlas generation, peak annotation, differential analysis, calculations for normalization factors, and visualization of genomic tracks were described previously (Lau et al., 2022). Features were considered differential if they showed a false discovery rate–adjusted P value <0.05, adjusted for multiple hypothesis correction, and an absolute Log2FC of >0.5.

Statistical testing

Data were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t tests, ordinary one-way ANOVA, or Kruskal–Wallis test were stated. Survival was assessed using the Logrank test. Most experiments did not require blinding since objective quantitative assays, such as flow cytometry, were used. For tumor experiments, female mice of different genotypes were randomized, and the operator was blinded to genotype before injection and again before counting of metastatic nodules or assessment of histology images to allow for objective assessment. Experimental sample sizes were chosen using power calculations, preliminary experiments, or were based on previous experience of variability in similar experiments. Samples that had undergone technical failure during processing were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows genome accessibility around the Bach2 locus in murine NK cells of differing maturity, phenotypic analysis of NK cells from the blood of Bach2−/− animals, and survival and histopathological analysis of tissues from an aging cohort of Bach2−/−, Rag2−/− Bach2−/−, Rag2−/−, and WT mice. Fig. S2 shows phenotypic analysis of NK cells from Rag2−/− Bach2−/− animals and Rag2−/− controls, as well as from the CD45.1+ CD45.2+ control compartment of mixed BM chimeras. Fig. S3 shows transcriptional analysis of NK cells from mixed BM chimeras compared to WT NK cells sorted into subsets according to maturity. Fig. S3 also shows analysis of phenotype, proliferative capacity, and apoptotic markers after culture of NK cells or sorted subsets in vitro, and growth of subcutaneously implanted tumors in Bach2fl/fl Ncr1iCre+ animals and controls. Table S1 shows expression of genes significantly up- or downregulated in Bach2-cKO NK cells (Padj ≤ 0.2). Table S2 shows expression of genes significantly up- or downregulated in Bach2-KO NK cells (Padj ≤ 0.2). Table S3 shows ssGSEA of bulk NK and NK subsets sorted from Bach2-cKO and Bach2-cWT animals with immunologic genesets (ImmuneSigDB; Pval < 0.05, |FC| > 1.5). Table S4 shows GSEA of genes significantly upregulated in Bach2-KO vs. WT CD8 T cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016) within the ranked global transcriptional differences between Bach2-cKO vs. Bach2-cWT NK cells. Table S5 shows GSEA of genes significantly downregulated in Bach2-KO vs. WT CD8 T cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016) within the ranked global transcriptional differences between Bach2-cKO vs. Bach2-cWT NK cells.

Supplementary Material

shows expression of genes significantly up- or downregulated in Bach2-cKO NK cells (Padj ≤ 0.2).

shows expression of genes significantly up- or downregulated in Bach2-KO NK cells (Padj ≤ 0.2).

shows ssGSEA of bulk NK and NK subsets sorted from Bach2-cKO and Bach2-cWT animals with immunologic gene sets (ImmuneSigDB; Pval < 0.05, |FC| > 1.5).

shows GSEA of genes significantly upregulated in Bach2-KO vs. WT CD8 T cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016) within the ranked global transcriptional differences between Bach2-cKO vs. Bach2-cWT NK cells.

shows GSEA of genes significantly downregulated in Bach2-KO vs. WT CD8 T cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016) within the ranked global transcriptional differences between Bach2-cKO vs. Bach2-cWT NK cells.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank members of the University of Cambridge University Biomedical Services facility at the Gurdon Institute and the Babraham Institute Biological Support Unit facility for technical support with animal experiments. We thank members of the flow cytometry facilities at both the Babraham Institute and the Department of Pathology, University of Cambridge for their assistance with cell sorting and analysis. Ncr1iCre mice were a kind gift from Eric Vivier (Aix-Marseille University, Marseille, France).

The research was supported by Medical Research Council grants MR/S024468/1 and MR/W018454/1, Wellcome Trust/Royal Society grant 105663/Z/14/Z, UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant BB/N007794/1 and Cancer Research UK grant C52623/A22597.

Author contributions: C.J. Imianowski and R. Roychoudhuri wrote the manuscript and designed experiments. C.J. Imianowski, S.K. Whiteside, T. Lozano, A.C. Evans, J. Benson, C.J.F. Courreges, F. Sadiyah, N.D. Zandhuis, F.M. Grant, M.J. Schuijs, P. Vardaka, and P. Kuo performed experiments. C.J. Imianowski, C.M. Lau, and R. Roychoudhuri analyzed bioinformatic data. E.J. Soilleux performed histopathological analysis and scoring. M.J. Schuijs, J. Yang, J.C. Sun, K. Okkenhaug, and T.Y.F. Halim provided protocols and support and advised on methodology. R. Roychoudhuri supervised the work.

References

- Afonina, I.S., Cullen S.P., and Martin S.J.. 2010. Cytotoxic and non-cytotoxic roles of the CTL/NK protease granzyme B. Immunol. Rev. 235:105–116. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00908.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afzali, B., Gronholm J., Vandrovcova J., O’Brien C., Sun H.W., Vanderleyden I., Davis F.P., Khoder A., Zhang Y., Hegazy A.N., et al. 2017. BACH2 immunodeficiency illustrates an association between super-enhancers and haploinsufficiency. Nat. Immunol. 18:813–823. 10.1038/ni.3753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi, J., and Wang X.. 2020. Molecular regulation of NK cell maturation. Front. Immunol. 11:1945. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro, J.D., Giresi P.G., Zaba L.C., Chang H.Y., and Greenleaf W.J.. 2013. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods. 10:1213–1218. 10.1038/nmeth.2688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligiuri, M.A. 2008. Human natural killer cells. Blood. 112:461–469. 10.1182/blood-2007-09-077438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerwenka, A., and Lanier L.L.. 2016. Natural killer cell memory in infection, inflammation and cancer. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16:112–123. 10.1038/nri.2015.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiossone, L., Chaix J., Fuseri N., Roth C., Vivier E., and Walzer T.. 2009. Maturation of mouse NK cells is a 4-stage developmental program. Blood. 113:5488–5496. 10.1182/blood-2008-10-187179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, P.L., Cella M., Porter S.I., Li S., Gurewitz G.L., Hong H.S., Johnson R.P., Oltz E.M., and Colonna M.. 2019. Gene regulatory programs conferring phenotypic identities to human NK cells. Cell. 176:348–360.e12. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.11.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diefenbach, A., Tomasello E., Lucas M., Jamieson A.M., Hsia J.K., Vivier E., and Raulet D.H.. 2002. Selective associations with signaling proteins determine stimulatory versus costimulatory activity of NKG2D. Nat. Immunol. 3:1142–1149. 10.1038/ni858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebina-Shibuya, R., Matsumoto M., Kuwahara M., Jang K.J., Sugai M., Ito Y., Funayama R., Nakayama K., Sato Y., Ishii N., et al. 2017. Inflammatory responses induce an identity crisis of alveolar macrophages, leading to pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. J. Biol. Chem. 292:18098–18112. 10.1074/jbc.M117.808535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, T.L., and Sun J.C.. 2016. Development and maturation of natural killer cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 39:82–89. 10.1016/j.coi.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilfillan, S., Ho E.L., Cella M., Yokoyama W.M., and Colonna M.. 2002. NKG2D recruits two distinct adapters to trigger NK cell activation and costimulation. Nat. Immunol. 3:1150–1155. 10.1038/ni857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasner, A., Ghadially H., Gur C., Stanietsky N., Tsukerman P., Enk J., and Mandelboim O.. 2012. Recognition and prevention of tumor metastasis by the NK receptor NKp46/NCR1. J. Immunol. 188:2509–2515. 10.4049/jimmunol.1102461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh, W., and Huntington N.D.. 2017. Regulation of murine natural killer cell development. Front. Immunol. 8:130. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, F.M., Yang J., Nasrallah R., Clarke J., Sadiyah F., Whiteside S.K., Imianowski C.J., Kuo P., Vardaka P., Todorov T., et al. 2020. BACH2 drives quiescence and maintenance of resting Treg cells to promote homeostasis and cancer immunosuppression. J. Exp. Med. 217:e20190711. 10.1084/jem.20190711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillerey, C., Huntington N.D., and Smyth M.J.. 2016. Targeting natural killer cells in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Immunol. 17:1025–1036. 10.1038/ni.3518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa, Y., and Smyth M.J.. 2006. CD27 dissects mature NK cells into two subsets with distinct responsiveness and migratory capacity. J. Immunol. 176:1517–1524. 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herndler-Brandstetter, D., Ishigame H., Shinnakasu R., Plajer V., Stecher C., Zhao J., Lietzenmayer M., Kroehling L., Takumi A., Kometani K., et al. 2018. KLRG1(+) effector CD8(+) T cells lose KLRG1, differentiate into all memory T cell lineages, and convey enhanced protective immunity. Immunity. 48:716–729.e8. 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, T.D., Pandey R.V., Helm E.Y., Schlums H., Han H., Campbell T.M., Drashansky T.T., Chiang S., Wu C.Y., Tao C., et al. 2021. The transcription factor Bcl11b promotes both canonical and adaptive NK cell differentiation. Sci. Immunol. 6:eabc9801. 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc9801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igarashi, K., Kurosaki T., and Roychoudhuri R.. 2017. BACH transcription factors in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 17:437–450. 10.1038/nri.2017.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh-Nakadai, A., Hikota R., Muto A., Kometani K., Watanabe-Matsui M., Sato Y., Kobayashi M., Nakamura A., Miura Y., Yano Y., et al. 2014. The transcription repressors Bach2 and Bach1 promote B cell development by repressing the myeloid program. Nat. Immunol. 15:1171–1180. 10.1038/ni.3024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamimura, Y., and Lanier L.L.. 2015. Homeostatic control of memory cell progenitors in the natural killer cell lineage. Cell Rep. 10:280–291. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.H., Gasper D.J., Lee S.H., Plisch E.H., Svaren J., and Suresh M.. 2014. Bach2 regulates homeostasis of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells and protects against fatal lung disease in mice. J. Immunol. 192:985–995. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S., Iizuka K., Kang H.S.P., Dokun A., French A.R., Greco S., and Yokoyama W.M.. 2002. In vivo developmental stages in murine natural killer cell maturation. Nat. Immunol. 3:523–528. 10.1038/ni796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kometani, K., Nakagawa R., Shinnakasu R., Kaji T., Rybouchkin A., Moriyama S., Furukawa K., Koseki H., Takemori T., and Kurosaki T.. 2013. Repression of the transcription factor Bach2 contributes to predisposition of IgG1 memory B cells toward plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 39:136–147. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krneta, T., Gillgrass A., Chew M., and Ashkar A.A.. 2016. The breast tumor microenvironment alters the phenotype and function of natural killer cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 13:628–639. 10.1038/cmi.2015.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanier, L.L. 2005. NK cell recognition. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 23:225–274. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C.M., Adams N.M., Geary C.D., Weizman O.E., Rapp M., Pritykin Y., Leslie C.S., and Sun J.C.. 2018. Epigenetic control of innate and adaptive immune memory. Nat. Immunol. 19:963–972. 10.1038/s41590-018-0176-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, C.M., Wiedemann G.M., and Sun J.C.. 2022. Epigenetic regulation of natural killer cell memory. Immunol. Rev. 305:90–110. 10.1111/imr.13031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litchfield, K., Reading J.L., Puttick C., Thakkar K., Abbosh C., Bentham R., Watkins T.B.K., Rosenthal R., Biswas D., Rowan A., et al. 2021. Meta-analysis of tumor- and T cell-intrinsic mechanisms of sensitization to checkpoint inhibition. Cell. 184:596–614.e14. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Soto, A., Gonzalez S., Smyth M.J., and Galluzzi L.. 2017. Control of metastasis by NK cells. Cancer Cell. 32:135–154. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love, M.I., Huber W., and Anders S.. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaise, M., Rovira J., Renner P., Eggenhofer E., Sabet-Baktach M., Lantow M., Lang S.A., Koehl G.E., Farkas S.A., Loss M., et al. 2014. KLRG1+ NK cells protect T-bet-deficient mice from pulmonary metastatic colorectal carcinoma. J. Immunol. 192:1954–1961. 10.4049/jimmunol.1300876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel, T., Poli A., Cuapio A., Briquemont B., Iserentant G., Ollert M., and Zimmer J.. 2016. Human CD56bright NK cells: An update. J. Immunol. 196:2923–2931. 10.4049/jimmunol.1502570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto, A., Ochiai K., Kimura Y., Itoh-Nakadai A., Calame K.L., Ikebe D., Tashiro S., and Igarashi K.. 2010. Bach2 represses plasma cell gene regulatory network in B cells to promote antibody class switch. EMBO J. 29:4048–4061. 10.1038/emboj.2010.257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muto, A., Tashiro S., Nakajima O., Hoshino H., Takahashi S., Sakoda E., Ikebe D., Yamamoto M., and Igarashi K.. 2004. The transcriptional programme of antibody class switching involves the repressor Bach2. Nature. 429:566–571. 10.1038/nature02596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narni-Mancinelli, E., Chaix J., Fenis A., Kerdiles Y.M., Yessaad N., Reynders A., Gregoire C., Luche H., Ugolini S., Tomasello E., et al. 2011. Fate mapping analysis of lymphoid cells expressing the NKp46 cell surface receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:18324–18329. 10.1073/pnas.1112064108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyake, T., Itoh K., Motohashi H., Hayashi N., Hoshino H., Nishizawa M., Yamamoto M., and Igarashi K.. 1996. Bach proteins belong to a novel family of BTB-basic leucine zipper transcription factors that interact with MafK and regulate transcription through the NF-E2 site. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:6083–6095. 10.1128/MCB.16.11.6083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessino, A., Sivori S., Bottino C., Malaspina A., Morelli L., Moretta L., Biassoni R., and Moretta A.. 1998. Molecular cloning of NKp46: A novel member of the immunoglobulin superfamily involved in triggering of natural cytotoxicity. J. Exp. Med. 188:953–960. 10.1084/jem.188.5.953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli, A., Michel T., Theresine M., Andres E., Hentges F., and Zimmer J.. 2009. CD56bright natural killer (NK) cells: An important NK cell subset. Immunology. 126:458–465. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.03027.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards, J.O., Chang X., Blaser B.W., Caligiuri M.A., Zheng P., and Liu Y.. 2006. Tumor growth impedes natural-killer-cell maturation in the bone marrow. Blood. 108:246–252. 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, S.H., Tessmer M.S., Mikayama T., and Brossay L.. 2004. Expansion and contraction of the NK cell compartment in response to murine cytomegalovirus infection. J. Immunol. 173:259–266. 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychoudhuri, R., Clever D., Li P., Wakabayashi Y., Quinn K.M., Klebanoff C.A., Ji Y., Sukumar M., Eil R.L., Yu Z., et al. 2016. BACH2 regulates CD8(+) T cell differentiation by controlling access of AP-1 factors to enhancers. Nat. Immunol. 17:851–860. 10.1038/ni.3441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychoudhuri, R., Hirahara K., Mousavi K., Clever D., Klebanoff C.A., Bonelli M., Sciume G., Zare H., Vahedi G., Dema B., et al. 2013. BACH2 represses effector programs to stabilize T(reg)-mediated immune homeostasis. Nature. 498:506–510. 10.1038/nature12199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, T.N., and Schreiber R.D.. 2015. Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science. 348:69–74. 10.1126/science.aaa4971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L., Li K., Guo Y., Banerjee A., Wang Q., Lorenz U.M., Parlak M., Sullivan L.C., Onyema O.O., Arefanian S., et al. 2018. Modulation of NKG2D, NKp46, and Ly49C/I facilitates natural killer cell-mediated control of lung cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 115:11808–11813. 10.1073/pnas.1804931115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimasaki, N., Jain A., and Campana D.. 2020. NK cells for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Drug Dis. 19:200–218. 10.1038/s41573-019-0052-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahlne, G., Becker S., Brodin P., and Johansson M.H.. 2008. IFN-γ production and degranulation are differentially regulated in response to stimulation in murine natural killer cells. Scand. J. Immunol. 67:1–11. 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02026.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivier, E., Tomasello E., Baratin M., Walzer T., and Ugolini S.. 2008. Functions of natural killer cells. Nat. Immunol. 9:503–510. 10.1038/ni1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., Song Y., Bakker A.B., Bauer S., Spies T., Lanier L.L., and Phillips J.H.. 1999. An activating immunoreceptor complex formed by NKG2D and DAP10. Science. 285:730–732. 10.1126/science.285.5428.730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao, C., Lou G., Sun H.W., Zhu Z., Sun Y., Chen Z., Chauss D., Moseman E.A., Cheng J., D’Antonio M.A., et al. 2021. BACH2 enforces the transcriptional and epigenetic programs of stem-like CD8(+) T cells. Nat. Immunol. 22:370–380. 10.1038/s41590-021-00868-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zook, E.C., Li Z.Y., Xu Y., de Pooter R.F., Verykokakis M., Beaulieu A., Lasorella A., Maienschein-Cline M., Sun J.C., Sigvardsson M., and Kee B.L.. 2018. Transcription factor ID2 prevents E proteins from enforcing a naive T lymphocyte gene program during NK cell development. Sci. Immunol. 3:eaao2139. 10.1126/sciimmunol.aao2139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

shows expression of genes significantly up- or downregulated in Bach2-cKO NK cells (Padj ≤ 0.2).

shows expression of genes significantly up- or downregulated in Bach2-KO NK cells (Padj ≤ 0.2).

shows ssGSEA of bulk NK and NK subsets sorted from Bach2-cKO and Bach2-cWT animals with immunologic gene sets (ImmuneSigDB; Pval < 0.05, |FC| > 1.5).

shows GSEA of genes significantly upregulated in Bach2-KO vs. WT CD8 T cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016) within the ranked global transcriptional differences between Bach2-cKO vs. Bach2-cWT NK cells.

shows GSEA of genes significantly downregulated in Bach2-KO vs. WT CD8 T cells (Roychoudhuri et al., 2016) within the ranked global transcriptional differences between Bach2-cKO vs. Bach2-cWT NK cells.