Abstract

The early 20th century was a time of rapid technological innovation and of demanding greater responsiveness of government and society to the needs of the common man. These impulses carried into the field of medicine, where quacks promised to overturn the medical establishment to bring wondrous new cures directly to the people. John Brinkley, among the foremost practitioners of that dark art, made a fortune implanting goat testicles into gullible men to cure sexual dysfunction and other ravages of old age. His medical training was limited, his treatments implausible, and yet, during a career that spanned over a quarter century, he became one of the best-known doctors of his era, through his use of technology, salesmanship, and politicking. Brinkley’s success illustrates how eager the public can be for panaceas, regardless of their actual merit, and the difficulty of interdicting the activities of quacks who have captured the public’s imagination.

Keywords: History of Medicine, Quackery, Communications in Medicine

John R. Brinkley was born in 1885 in the rural Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina. He was raised in a poor home by his uncle and aunt after both of his parents died in his early childhood.1 In 1907, at the age of 22, Brinkley created a medicine show with his first wife, in which they performed song and dance routines while hawking homebrewed tonics.2 Brinkley learned several key lessons from that experience, including the power of criticizing mainstream doctors as self-interested, and the technique of connecting with audiences by appealing to both their values and their fears.1 Such tactics worked well in the early 20th century, when mainstream medical treatments had little more scientific support than remedies being hawked at shows like his.2

After a brief period on the medicine show circuit, Brinkley moved to Chicago and began studies at the Bennett Medical College, one of a number of “eclectic” schools that trained physicians in the use of botanical remedies prior to the 1910 Flexner report. Lacking money to pay his tuition, Brinkley dropped out of the college without obtaining a degree and moved around the country for several years, while fleeing from collectors.1,3 During this itinerant period, he worked briefly with goats in a slaughterhouse, where he was fascinated by their apparent immunity to human disease.3 At about this time, he separated from his first wife and married a second woman, Minnie Telitha, without finalizing a divorce from his first wife.

Eventually, Brinkley received a medical degree from the Eclectic Medical College of Kansas City, giving rise to the argument that he “possessed as good a medical education as many of his contemporaries”1 during an era of poor medical educational standards. After graduation, Brinkley answered an advertisement from the town of Milford, Kansas, seeking a family physician for that rural community.

1. The goat gland operation

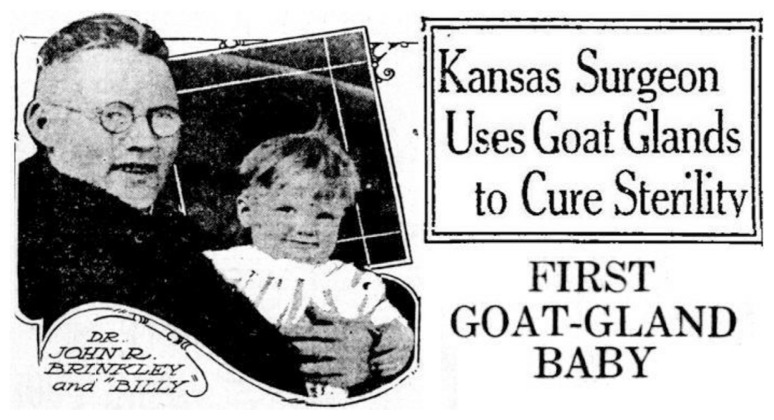

Brinkley arrived in Milford in 1917, and began practice as the town doctor. When the Spanish flu reached Milford, he provided commendable care to stricken members of the community.4 However, soon after his arrival, his practice veered in a new direction, when he was consulted by an elderly farmer who was having trouble fathering another child. Having earlier perceived goats as a wellspring of health and virility, Brinkley offered to implant the testes of a goat into the man surgically as a means of restoring his virility. The farmer was apparently thrilled with the results of the operation for reasons not specified. News of the miraculous treatment traveled fast throughout Milford, generating a second patient, William Stittsworth, who requested not just the goat gland operation on himself, but implantation of goat ovaries into his wife.1 Within a year, the couple birthed a son, fittingly named “Billy.”1 (Fig. 1) Brinkley performed the operation on several more patients, reportedly to unanimous positive reviews. At the height of his practice, he charged $750 (over $10,000 in 2020 dollars) for each procedure.2,5

Fig. 1. Advertisement for Brinkley’s Clinic, 1920s.

This newspaper advertisement showed Brinkley posing with Billy Stittsworth, who was born following Brinkley’s second xenotransplantation operation on his father. Photo from Wikimedia Commons.

In response to this early success, Brinkley hired an advertising consultant, to disseminate information on his procedure to newspapers around the country. The story caught the attention of a number of prominent men, including J. J. Tobias, chancellor of the University of Chicago Law School, who traveled to Milford for the Brinkley procedure. Of the operation he wrote later: “I was played out … I was an old man. I went to Milford and underwent Dr. Brinkley’s operation … Four days later the headaches disappeared … And seven days later I left the hospital feeling twenty-five years younger. And I seem to grow still younger every day.”3

Also intrigued by Brinkley’s treatment was Harry Chandler, owner of both the Los Angeles Times and that city’s first radio station, KHJ. Chandler invited Brinkley to operate on him in California with similar results. Chandler expressed his gratitude by extolling the virtue of Brinkley’s operation in print.5 The rave reviews from Tobias and Chandler brought Brinkley a torrent of patients, notoriety and money, which enabled him to build his own hospital in Milford.

The idea of xenotransplantation was neither new nor regarded as absurd during Brinkley’s time. Many mainstream physicians of that era believed that animal tissues could be transplanted successfully into humans.1 Efforts to implant animal blood and skin grafts into humans had been attempted as early as the 17th century, and in 1838, a corneal pig xenotransplant was performed.6 In the early 20th century, French surgeon Serge Voronoff became world-famous for experiments involving the transplantation of ape testicles into humans.1,6 Although modern experts dismiss these early experiments as ill-conceived,6 they did generate considerable interest among mainstream physicians at the time. In 1922, Brinkley published a book devoted to his procedure, in which he claimed that “today I am able to announce to the world, without mincing words, that the right method has been found, that I am daily transplanting animal glands into human bodies, and that these transplanted glands continue to function as live tissue in the human body, revitalizing … the human gland.”7

Did Brinkley’s procedure provide any tangible benefit to his patients, or were the reported beneficial effects that followed the treatment simply a product of a placebo effect? Could the implanted goat testes have released certain androgen hormones or other products in response to being rejected by the human host that enhanced well-being and, perhaps, fertility? Although unlikely, the latter possibilities have never been explored scientifically.

2. Radio, celebrity, and battling the establishment

Brinkley’s California trip, introduced him to Harry Chandler’s radio station and the power of mass communication. In 1923 he founded his own station in Milford, KFKB, which quickly became the most popular station in America8 owing to Brinkley’s programming skill. The station featured a mixture of “country music, comedy, poetry readings, market news, weather reports,… orchestras, and gospel preaching.”1 Rural folk were attracted to the station for its variety programming, but also for twice daily medical talks hosted by Brinkley. The talks, which were called the Medical Question Box, discussed health issues while promoting Brinkley’s hospital and procedures. In a daring move for the time, many questions considered on the Medical Question Box concerned issues of sexuality, which established Brinkley as assort of “Dr. Ruth Westheimer of the twenties and thirties.”9 His radio programs enabled him to gain the trust of his audience, which brought thousands of listeners to his hospital.

Brinkley next began branching out into the pharmaceutical business by forming a network of proprietary pharmacists who promoted his patent medicines. He prescribed medications on his radio show and encouraged listeners to self-diagnose and self-treat their illnesses. Mainstream medicine took note and began raising concern about the danger Brinkley posed to his patients.1

As Brinkley’s fame increased, so did scrutiny of his practice at a time of heightened attention to the lax standards of medical schools in North America. In 1923, newspapers began a series of reports on eclectic medical colleges (including Brinkley’s alma maters), which they accused of selling degrees in the absence of minimal attendance requirements. That same year, California tried to arrest Brinkley for practicing medicine without a standard medical education. However, the Kansas Governor, a friend of Brinkley’s, refused to extradite him to California. Nevertheless, journalists at the Kansas City Star10 seized on the story of Brinkley’s questionable practices, and began publishing the experiences of dissatisfied patients.

Meanwhile, Morris Fishbein, editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association, was mounting a wholesale crusade against quacks in the medical profession. In a piece published in JAMA in 1928, he called into question Brinley’s medical education by pointing out that he had been employed in New York while claiming to have been in school in Baltimore.11 In April 1930, Fishbein attacked Brinkley further by describing him in another JAMA editorial as “a charlatan of the rankest sort” … whose radio station was being used to “victimize people and to enrich himself.”1 Medical societies in Kansas took up Fishbein’s cause and began proceedings to revoke Brinkley’s medical license. Brinkley responded with screeds via KFKB, that promised to produce ten happy patients for every unhappy one the medical societies uncovered.1

In 1930, Brinkley was finally brought before the Kansas Medical Board on eleven charges, including misrepresentation of his educational credentials and improper prescribing of treatments over the radio without examining patients or subjecting them to proper laboratory testing.1 The Brinkley defense responded by calling attention to an article written by Fishbein, which “predicted that the doctor of the future would never have direct contact with patients, but would sit behind a large desk while diagnosing and prescribing over the television, much like John Brinkley was doing with his Medical Question Box on the radio.”1 Brinkley also had members of the board visit his hospital to see him operate. One who accepted the invitation was impressed enough with Brinkley’s technical skill, to describe his work “as skillful and deft a demonstration of surgery as he had ever witnessed.”1 However, Brinkley’s surgical skill was not enough to save his license. In September 1930, the board revoked Brinkley’s Kansas medical license for “gross immorality” and “unprofessional conduct.”1 Separately, but nearly simultaneously, KFKB’s radio license was revoked, forcing the station off the air in February 1931.12 Even so, this was not the end of Brinkley’s enterprise. His licensed associates at his hospital in Milford continued to perform his operation. Moreover, Brinkley’s hearings before the Kansas Medical Board actually increased his medical business by making him a martyr. Many Kansans trusted him more than the outside journalists, broadcasters, and the medical establishment, who were attacking him.

The outpouring of support that followed Brinkley’s hearing included a number of letters asking him to run for Governor, and five days after the Medical Board revoked his license, he announced his candidacy for the position as an independent, write-in candidate. He ran on a platform of “fearlessness, independence, [and] sympathy for the masses,”13 designed to appeal to those disaffected by the economic hardships of a state entering the Great Depression. He campaigned for workmen’s compensation, a Child Labor Amendment, free medical care for the poor, and pensions for the elderly and disabled; many of these populist proposals would be echoed in Roosevelt’s New Deal by decade’s end.14

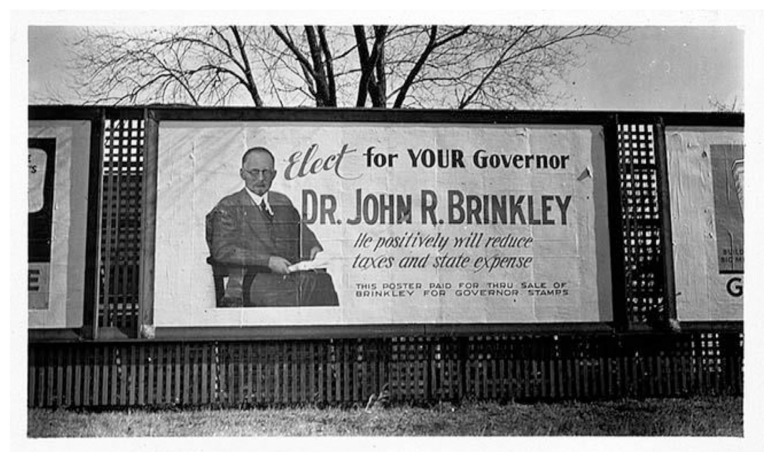

In the midst of the campaign, in a move reminiscent of some of the political maneuvering during the 2020 U.S. presidential campaign, the Kansas Attorney General announced that in order for write-in votes for Brinkley to count, they had to be written exactly as “J. R. Brinkley” and in no other way. This was a clear break from precedent in which such votes had previously been counted as long as the voter’s intent was clear.15 In the end, Brinkley finished a close third with over 183,000 votes out of a record-setting 600,000 total. As many as 50,000 votes are generally thought to have been disqualified over the technicality of writing Brinkley’s name improperly, which would have been more than enough to swing the race in Brinkley’s favor had they been counted.1 Brinkley decided not to contest the results of the election. Instead, he set his sights on a repeat bid in 1932 (Fig. 2), which again ended in a close third place loss.

Fig. 2. Campaign poster for John R. Brinkley for Governor, 1932.

This photo of a billboard from Brinkley’s second gubernatorial run shows his prominent branding of himself as a doctor and populist rhetoric of reducing taxes. Photograph from J. T. Williard, https://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/37099.

3. Leaving Kansas and eventual downfall

After losing KFKB, Brinkley traveled to Mexico and built a new radio station, XER in Villa Acuña, across the Rio Grande from Del Rio, Texas. In late 1932, he moved to Del Rio full-time to be closer to his new radio station and to use the Texas medical license he still possessed to continue practicing medicine. In Del Rio, his practice flourished, generating an annual income of over one million dollars.

Around 1933, Brinkley quietly changed his medical focus to the prostate, which he called that “troublesome old cocklebur.”16 He gave up implantation of goat testes for a procedure similar to a unilateral vasectomy, which he claimed cured prostate problems. The procedure was accompanied by a series of six post-operative injections of a compound called “ Formula 1020,” which on analysis was found to be nothing more than a dilute solution of blue dye in water. Morris Fishbein described the manufacture of Formula 1020 as “raking a body of water like Lake Erie, coloring it with a dash of bluing and then selling the stuff at $100 for six ampules.”17

Brinkley’s new surgical procedure made him more susceptible to patient complaints. Rejuvenation patients were often too embarrassed to complain when implantation of goat testes failed to cure their ills. However, as noted by Fishbein, “men do not have the same hesitancy about discussing operations for the relief of pathological conditions of the prostate than they do in talking about sexual rejuvenation.”1

In 1938, Brinkley moved again, this time to Arkansas, a state known for a particularly lenient medical licensing board, where several of Brinkley’s associates were licensed.16 Shortly thereafter, Fishbein published an article in Hygeia denouncing Brinkley as an example of “quackery [that had] reached its apotheosis.” He stated further that Brinkley had “consummate gall beyond anything revealed by any other charlatan … [in] shaking the shekels from the pockets of credulous Americans.”1 Brinkley decided to sue for libel, which proved disastrous. In the libel trial that ensued, Fishbein’s attorney forced Brinkley to admit that he knew the goat-gland operation “did not and could not rejuvenate a man by itself and that his advertisements claiming this ability during the previous decade were false.”1 Fishbein’s attorney then went on to say that “Dr. Brinkley is the foremost money-making surgeon in the world because he had sense enough to know the weaknesses of human nature and gall enough to make a million dollars a year out of it.”1 The jury returned a verdict in favor of Fishbein; Brinkley’s attorneys appealed; and an appellate court concluded that “the plaintiff by his methods violated acceptable standards of medical ethics—the plaintiff should be considered a charlatan and a quack in the ordinary, well-understood meaning of those words.”1

For Brinkley, the results of that defeat were immediate and devastating. The Fishbein libel case legally branded him a charlatan, leading to malpractice suits claiming more than $3 million in damages. Brinkley returned to Del Rio, where his financial woes and lawsuits continued to mount. His Mexican radio station was confiscated by the government, and in February 1941, he declared bankruptcy. In September 1941, a grand jury in Little Rock indicted Brinkley, his wife, and six associates on mail fraud charges, for which his wife and associates pled no contest. Brinkley’s trial was postponed due to ill health. His health rapidly declined thereafter. He died on May 26, 1942, never having been held legally accountable for his actions, in spite of amassing a fortune during over two decades as a quack.

4. Legacy

John R. Brinkley has rightly been labeled a quack, “an ignorant or fraudulent pretender to medical skill,”1 who placed personal gain above his patients’ best interests. And yet, in a certain perverted sense, he was one of the great medical minds of his era. He drew attention to two subjects largely ignored by medicine during that time – aging and failing sexuality in older men. And though he knew his methods were worthless, he performed them with a technical competency and focus on the patient that was equal to or better than reputable doctors of his era. Moreover, he demonstrated the power of mass communication in the practice of medicine, as perhaps, the first doctor to use broadcasting to provide medical advice to the public at large. Even Brinkley’s critics admitted that he was a talented surgeon, communicator, and businessman. He might have contributed much to medicine had he focused on legitimate, ethical practices, rather than the pursuit of wealth at the expense of his patients.1

Acknowledgements

Production of this manuscript was supported by NIH Grant #1F30HL145901 to PCS.

I thank Dr. Phil Mackowiak, MD, Professor Emeritus of Medicine at University of Maryland School of Medicine, for his help in editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The author denies any conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Alton Lee R. The Bizarre Careers of John R Brinkley. The University Press of Kentucky; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pope Brock. Charlatan: America’s Most Dangerous Huckster, the Man Who Pursued Him, and the Age of Flimflam. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harlan Resler Ansel. The Impact of John R Brinkley on Broadcasting in the United States. Northwestern University ProQuest Dissertations Publishing; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blair Tarr. Kansans of the great war era: Dr. John R. Brinkley. Kansas world war I centennial committee; 2016. https://ksww1.ku.edu/kansans-of-the-great-war-era-dr-john-r-brinkley/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mark Oliver, John Kuroski.Phony Dr. John Brinkley healed people with goat testicles — and made $12 million it. doing. Nov 26, 2018. https://allthatsinteresting.com/john-brinkley .

- 6. Cooper David KC. A brief history of cross-species organ transplantation. Proceedings (Baylor University. Medical Center) 2012;25(1):49–57. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2012.11928783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brinkley John R. The Brinkley Operation. S. B. Flower & Co; 1922. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gene Fowler, Bill Crawford. Border Radio. Texas Monthly Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evan Kindley.Nuts!: A Questionable Cure for Impotence. The New Republic. Jun 22, 2016. https://newrepublic.com/article/135422/nuts-questionable-cure-impotence .

- 10. Shelby Maurice E. John R. Brinkley and the Kansas city star. J Broadcast. 1978;22(1):33–45. doi: 10.1080/08838157809363864. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Morris Fishbein. John R. Brinkley – Quack. JAMA. 1928 January 14;90(2):134. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henry Robb Charles. Court of appeals of the District of Columbia. Feb 2, 1931. KFKB broadcasting Association vs. federal radio commission. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brinkley John R. Advertisement: The J. R. Brinkley Platform. The Belleville Telescope. Belleville, Kansas: Oct 30, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Clark Carroll D, Gist Noel P. Dr. John R. Brinkley: a case study in collective behavior. The Kansas Journal of Sociology. 1966;2(2):52–58. Published by: Social Thought and Research https://www.jstor.org/stable/23308471. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sam Zeff.The last time A Kansas gubernatorial election was this close, it involved goat glands. KCUR-FM. 2018. Aug 9, https://www.kcur.org/politics-elections-and-government/2018-08-09/the-last-time-a-kansas-gubernatorial-election-was-this-close-it-involved-goat-glands .

- 16. Schneider Albert J. That troublesome old cocklebur:” John R. Brinkley and the medical profession of Arkansas, 1937–1942. Ark Hist Q. 1976;35(1):27–46. Published by: Arkansas Historical Association https://www.jstor.org/stable/40018997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greenspan Robert E. Medicine: Perspectives in History and Art. 2006:488–571. [Google Scholar]