Abstract

Background:

Syphilis is one of the most important sexually transmitted infections (STI) and a public health problem, but the literature describing the true burden of syphilis is limited. In Iran, there are no accurate results on the prevalence of syphilis. This study aimed to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of syphilis in Iran.

Methods:

Following PRISMA guidelines, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies published on the prevalence of Syphilis in Iran. We systematically reviewed the literature to identify eligible studies as of Sep 13, 2020, in international and national databases. The results are presented in the form of forest plots and tables. Pooled prevalence and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using Der Simonian and Laird method. Perform subgroup analysis through population, gender, city, and diagnostic tests to assess the source of heterogeneity.

Results:

We reviewed 1,229 papers and reports, and extracted data from 15 eligible records. The prevalence of combined syphilis in Iran is 0.1% (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.1–0.1%). The prevalence of syphilis was 0.4% in men (95% confidence interval [95% CI] −0.3, 1%) and 0.6% in women (95% confidence interval [95% CI] (0.1, 1%)). The cumulative meta-analysis showed a decline in the prevalence of syphilis between the years 1999 and 2015.

Conclusion:

The prevalence of syphilis in Iran is low. In the past few decades, the prevalence of syphilis across the country has declined. Syphilis infection is a small burden that needs to be revised in the implementation of high-cost screening programs.

Keywords: Sexually transmitted infection, Syphilis, Meta-analysis, Iran

Introduction

All people, whether rich or poor, male or female, elderly or young, may be affected by blood-borne infections (1), among which sexually transmitted diseases (STD) are considered to be the world’s major public health problem (2). Syphilis is one of the most important sexually transmitted and blood-borne diseases caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum (3). It has four stages, and each stage has different symptoms. Syphilis is initially transmitted through direct contacts with the infected wounds of the infected person during sexual intercourse. The disease is also very contagious in the early stages, and after a while, a painless skin lesion called a canker develops on the affected person’s body (4). The canker may be located in an unknown anatomical area, the diagnosis of syphilis in both men and women is delayed in some cases until the subsequent clinical manifestations of the disease, and this leads to further transmission of the disease to the sexual partners of the patients or from mothers to fetuses. On the other hand, if left undiagnosed and untreated, syphilis can lead to cardiovascular complications, affect the nervous system, and cause congenital syphilis (5). This clearly shows the need for rapid and timely diagnosis of syphilis to control and prevent the spread of the disease among all people, especially among women before marriage and during pregnancy. To this end, health systems in various countries must pay close attention to women’s screening before marriage and during pregnancy.

In Iran, the prevalence of syphilis was 4.66% among patients referred to a medical clinic with clinical symptoms (6). Another study carried out on blood donors in Iran, indicated that the prevalence of syphilis was approximately 0.004% (7) (7). Although the prevalence of syphilis is low in both men and women, the disease is still common among high-risk groups in the country, including female sex workers (8, 9). According to WHO, there are approximately 12 million new cases of syphilis every year in men and women aged 15–49 in the world (10). However, there are no accurate data to properly understand the burden and the accurate epidemiology of sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis and to plan appropriate interventions and distribute resources (11).

Regarding the high prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases including syphilis among men and women and considering the need for urgent interventions to prevent the incidence of the disease among all community groups, especially women before marriage and during pregnancy, this study was conducted as a systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the prevalence of syphilis infections among the Iranian population.

Methods

Search Strategy

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (12), we searched the following databases from inception through to Sep 13, 2020: international (Medline, Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest, Cochrane and Google Scholar) and as well as Iranian databases including IranMedex, Scientific Information Database (SID), IRAN-DOC and the Iran Blood Transfusion Journal for original and quantitative studies that measured STIs prevalence in Iran. We reviewed the titles and abstracts to select potentially relevant papers. If there was any doubt about the suitability of the paper based on the abstract, the full text was reviewed. We manually searched the references and relevant articles for inclusion. We also looked at the electronic abstract list of congresses conducted in Iran and also at the electronic database of students’ thesis through universities” electronic libraries and websites, when was available. Keywords that we used for our search were “Syphilis OR Great Pox OR Treponema pallidum” AND (Prevalence* OR Incidence*) AND Iran (e.g., Iran OR Persia). The final search string used in databases be contacted the corresponding authors if needed.

Study selection criteria

Quantitative empirical studies were included in the review if they 1) were conducted in Iran, 2) were published in English or Persian, 3) have estimated Syphilis prevalence based on biological/serological diagnostic tests administered during the study, and 4) reported non-duplicate data (i.e., same data reported in multiple papers). Reviews, animal studies, clinical trials, commentaries and letters were excluded.

Data Collection

Data was extracted by one reviewer and double checked for the following items: type of study, sample size, location and time of the study, type of participants and prevalence of Syphilis and the coinfection. Each included study was coded for study characteristics (e.g., study’s author, year, location, sampling method, setting, and diagnostic tests), participant characteristics (e.g., age and sex). Disagreements in the screening and data extraction phases were resolved through further discussions.

Quality Assessment

Methodological quality was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute’s critical appraisal tool (13) for prevalence studies. This tool evaluates the extent to which a study has addressed the potential biases in its design, conduct, and analysis. Studies were examined for representativeness, sample size, recruitment, description of study participants and setting, data coverage of the identified sample, reliability of the measured condition, statistical analysis, and confounding factors. Scores ranged from 0–10 with ≤ 5 as “low/moderate quality” and > 5 as “fair quality.”

Data Analysis

After entering the extracted data into an excel sheet, the Stata version 16 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA) was used for statistical analyses. For estimating the pooled prevalence of syphilis, we used random-effects meta-analysis. We employed a random effects model with a DerSimonian-Laird method, as we suspected heterogeneity across the studies because of differences in syphilis diagnosis and study population. The pooled prevalence of syphilis, in different subgroups according to cites, study population, sampling methods and diagnostic test.

To assess differences in the accumulation of evidence for syphilis prevalence in Iran, cumulative meta-analyses were conducted. The cumulative meta-analysis provides cumulative pooled estimates and 95% CIs. To assess the sequential contributions of studies and evaluate changes in syphilis prevalence over time, studies were added alphabetically by years of implementation to a random-effects model. I-squared and Tau-squared statistics were applied for heterogeneity assessment.

Results

Participants and Study Characteristics

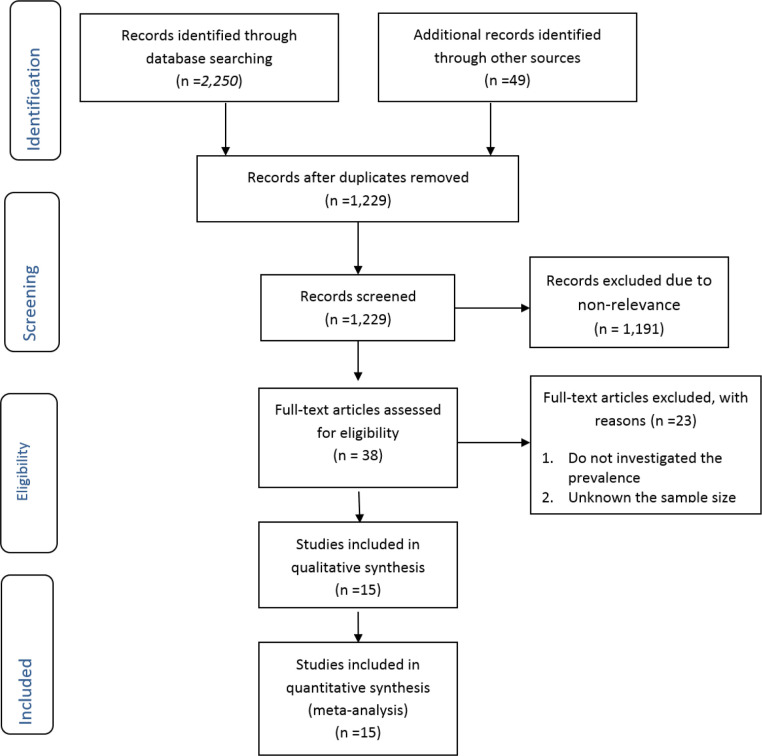

We found 1,229 non-duplicate studies, 15 of which met our inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). A description of the key characteristics of the included studies is provided in Table 1. The 15 studies included 1,022,254 participants, with sample sizes ranging from 41 (14) to 345,412 (7) with a median sample size of 635. All included studies were cross-sectional and most (n=13) had recruited through a convenience sampling approach; only two studies used probabilistic sampling methods. Most studies (n=6) were diagnosed the syphilis by the FTA-Abs test. Most studies (n=5) were conducted on the blood donor’s participants, and all were conducted in major urban settings.

Fig. 1:

Flowchart of the search and selection process

Table 1:

Characteristics of the included studies in meta-analysis

| First author and year of publication | Study date | Study location (city) | Total sample size | Study design | Study sampling procedure | Recruitment setting | Diagnostic test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khamisipour. et al, 2000(15) | 1999 | Bushehr | 635 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Referred to the clinic/hospital | RPR* |

| Nicbin. et al, 2003(16) | 2002 | Tehran | 500 | Cross-sectional study | Random sampling | Sex workers | RPR*

+FTA -Abs* |

| Tabassi. et al, 2004(17) | 2000 | Tehran | 50 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Referred to the clinic/hospital | NR* |

| Sadeghi. et al, 2007(18) | 2007 | Ardabil | 2198 | Cross-sectional study | Random sampling | General Population | VDRL* |

| Maleki. et al, 2008(19) | 2005 | Mashhad | 100 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Referred to the clinic/hospital | VDRL *+FT A-Abs |

| Khedmat. et al, 2009(7) | 2005 | Tehran | 345412 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Blood Donors | FTA- Abs |

| Khedmat. et al, 2009(7) | 2003 | Tehran | 329516 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Blood Donors | FTA- Abs |

| Khedmat. et al, 2009(7) | 2004 | Tehran | 329961 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Blood Donors | VDRL +FTA -Abs |

| Vahdani. et al, 2009(20) | 2007 | Tehran | 202 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Homeless | RPR |

| Navadeh. et al, 2012(21) | 2010 | Kerman | 177 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Sex workers | TPHA* |

| Moradmand Badie. et al, 2013(22) | 2008 | Tehran | 450 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | HIV patients | VDRL +FTA -Abs |

| Mohammadali. et al, 2014(23) | 2009 | Tehran | 10470 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Blood Donors | RPR |

| Hashemi-Shahri. et al, 2016 (14) | 2007 | Zahedan | 41 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | HIV patients | FTA- Abs |

| Shahesmaeili. et al, 2018(24) | 2015 | 13 Cities of IRAN | 1195 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Blood Donors | RPR |

| Khezri. et al, 2020(25) | 2015 | 13 Cities of IRAN | 1347 | Cross-sectional study | Convenience sampling | Sex workers | RPR |

RPR: A rapid plasma reagin, FTA-Abs: Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption, VDRL: The Venereal Disease Research Laboratory, TPHA: Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay, NR: Not reported

Risk of bias assessment

Details of the critical appraisal of the study qualities are summarized in Table 2. Overall, most studies endured from several methodological limitations, including response rate analysis and sampling method. Among the 15 included studies, six studies scored ≤5 (i.e., low/moderate quality), and nine studies scored >5 (i.e., fair quality).

Table 2:

Qualities of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis

| First Author/Year publication | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Total | Quality score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Khamisipour. et al, 2000 | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 5 | low/moderate |

| Nicbin. et al, 2003 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | 6 | Fair |

| Tabassi. et al, 2004 | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | NA | N | 2 | low/moderate |

| Sadeghi. et al, 2007 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 8 | Fair |

| Maleki. et al, 2008 | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | 4 | low/moderate |

| Khedmat. et al, 2009 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 | Fair |

| Khedmat. et al, 2009 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 | Fair |

| Khedmat. et al, 2009 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 | Fair |

| Vahdani. et al, 2009 | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 5 | low/moderate |

| Navadeh. et al, 2012 | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 5 | low/moderate |

| Moradmand Badie. et al, 2013 | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 6 | Fair |

| Mohammadali. et al, 2014 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 | Fair |

| Farrokhian. et al, 2016 | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | NA | N | 3 | low/moderate |

| Shahesmaeili. et al, 2018 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | 7 | Fair |

| Khezri. et al, 2020 | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N | 6 | Fair |

Keys:

A. Q1-Q9 represents questions used to assess the quality of included studies, listed below.

Q1. Was the sample frame appropriate to address the target populations?

Q2. Were the study participants sampled in appropriate way?

Q3. Was the sample size adequate?

Q4. Were the study subjects and setting described in details?

Q5. Was the data analysis conducted with sufficient coverage of the identified sample?

Q6. Was a valid method used in the identification of conditions?

Q7. Was the condition measured in a standard, reliable way for all participants?

Q8. Was there an appropriate statistical analysis?

Q9. Was the response rate adequate, and if not, was the low response rate managed appropriately?

B. Y, yes; N, no; U, unclear; NA, not applicable

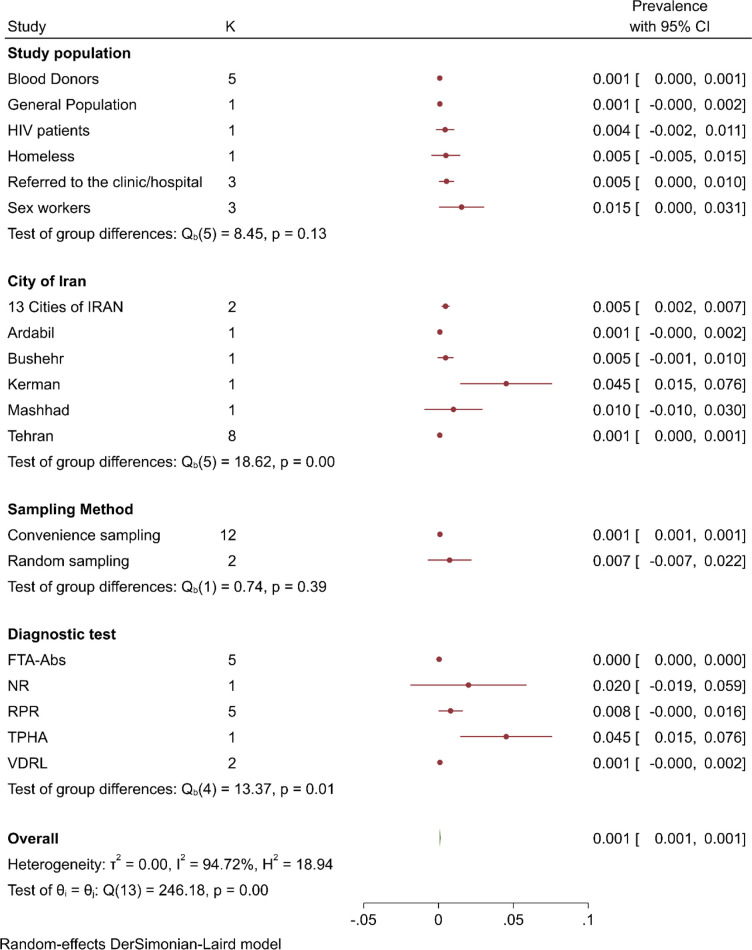

Prevalence of Syphilis

The estimated prevalence of syphilis obtained from the included studies as well as resulting pooled prevalence is presented in Fig. 2. The pooled syphilis prevalence was 0.001 (95% CI: 0.001, 0.001). Heterogeneity testing (I2=94.44%) revealed notable differences among the included studies in the meta-analysis; so that, meta-regression analyses revealed significant association between year of publication (β=0.0007, P<0.001), and year of study implementation (β = 0.0006, P<0.001).

Fig. 2:

Pooled syphilis prevalence in Iran

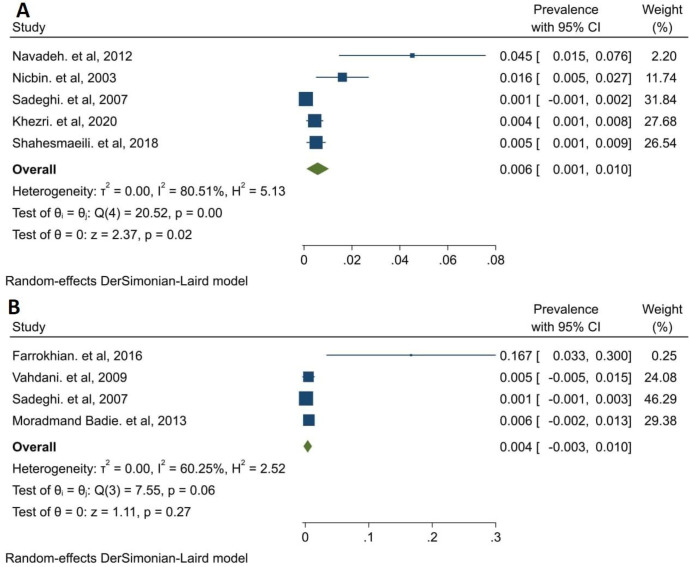

Prevalence of syphilis was reported in eight studies for Tehran 0.001 (95% CI: 0.000, 0.001), in five studies for blood donors 0.001 (95% CI: 0.000, 0.001), in three studies for referred to clinic/hospital participants 0.005 (95% CI: 0.000, 0.01), for sex workers 0.015 (95% CI: 0.000, 0.031) and in 12 studies for convenience sampling 0.001 (95% CI: 0.001, 0.001); another subgroup analysis was presented in Fig. 3. The prevalence of syphilis was 0.004 (95% CI: −0.003, 0.01) in men and 0.006 (0.001, 0.01) in women (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3:

Subgroup analysis of syphilis prevalence in Iran. FTA-ABS: Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody Absorption, NR: Not Reported, RPR: Rapid Plasma Regain, TPHA: Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay and VDRL: Venereal Disease Research Laboratory.

Fig. 4:

Pooled syphilis prevalence in Iran by sex. A: Women, B: Men

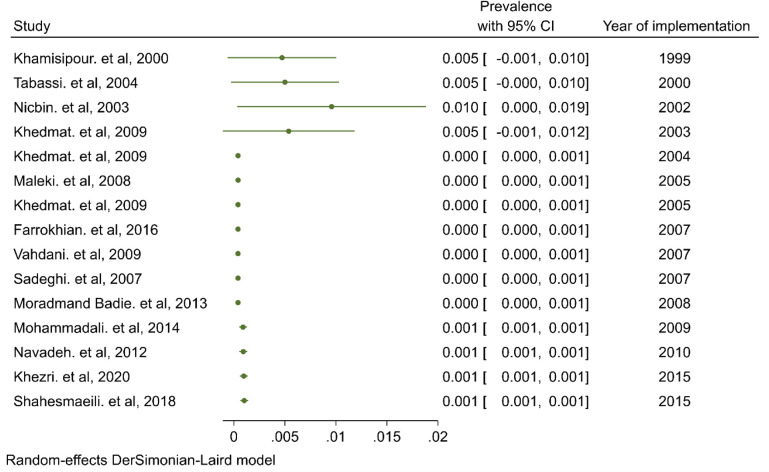

Cumulative meta-analysis

Cumulative meta-analysis was conducted to reflect the dynamic trend of results and evaluate the influence of individual study on the overall results. Figure 5 shows a forest plot for the cumulative meta-analysis for the trend of syphilis prevalence in Iran. A high prevalence of syphilis (Prevalence=0.005) was first observed in 199–2003, and then, a decline considerable was observed in 2004 and after that, the trend of results circa remained unchanged.

Fig. 5:

Cumulative meta-analysis of syphilis prevalence in Iran

Discussion

Sexually transmitted infections are one of the most common infectious diseases, affecting the health and lives of people all over the world. WHO estimated that in 2010, there were eleven million new cases of syphilis per year worldwide (26). The current systematic review and meta-analysis are based on 15 studies published between 1997 and 2021, involving 1,022,254 participants in Iran. This study examined the prevalence of syphilis in Iran. According to reports, the prevalence of syphilis ranged from 0% (7), to 0.112% in another study (21). In our study, the pooled estimates of the prevalence of syphilis assessed by meta-analysis were 0.004 (95% CI: −0.003, 0.01) for men and 0.006 (0.001, 0.01) for women. The pooled prevalence in this meta-analysis is comparable to the national surveillance report on the prevalence of syphilis among blood donors in Iran (27). The prevalence of syphilis among some specific populations were integrated. The prevalence of syphilis among the homeless in Tehran is 0.005 (20). The prevalence of female prisoners is 0.016. The most important risk factors are marital status and history of intravenous drug use. The prevalence of syphilis in Iranian cities ranges from 0.045 in Kerman (21) to 0.001 in Ardabil (28). The prevalence of syphilis in HIV patients is higher than that in the normal population. The prevalence of syphilis was 12.1%, (14) and other study reported 0.45% (22). On the other hand, ulcerated wounds from syphilis increase the chance of HIV infection (29). One percent of patients with genital anal warts had syphilis, and 2% had human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV) (30). If anyone is suspected, everyone be screened for STI and HIV (31) Syphilis is associated with transmission and infecting with other STIs like HIV itself.in a study reporting the incidence in men primary and secondary syphilis diagnosis, 1 in 20 men having sex with men were diagnosed with HIV within a year after syphilis diagnosis (32). The most important risk factors of syphilis has been reported to be sexual relationship with casual partners in the last year, same-sex sexual relationships, more than 10 partners, and having sexual intercourse before 15 years of age (33). The initiation of sex before the age of 18 is associated with an increased chance of chlamydia infection, this relationship is not statistically significant for syphilis (25). Nevertheless, early start of sex work between FSW is a great risk factor for unsafe sexual practices which can increase the chance of infecting with either HIV or STI.

The stages of syphilis are divided into early and late stages. Early syphilis includes primary and secondary syphilis that occur within a few weeks to 12 months after the first infection. Late syphilis includes untreated syphilis after 1 year, which may be as long as 30 years. The most common symptom of early syphilis is a localized skin lesion called chancre. The median incubation period seems to be about 21 d (3 to 90 d). Adenopathy and skin rashes as well as constitutional symptoms can be symptoms of secondary syphilis (34). Among Female Sex Workers (FSW), vaginal discharge is the most common symptom. In FSW, the incidence of gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis or HPV is about 40%. Although only one-third of syphilis patients will have excessive vaginal discharge. The overall sensitivity of diagnosis of syphilis based on common symptoms of sexual transmitted diseases (STI) like excessive vaginal discharge, genital ulcers, pain or burning sensation and genital warts was around 33%, the lease sensible for diagnosis based on symptoms between other common STIs. From FSW in 3 cities of Iran in 2012, only 63.9% of patients with STI symptoms had reported their symptoms (35). This means that attempts to detect STI in clinically referred patients are not sensitive enough. The prevalence of syphilis in asymptomatic individuals was 0.4%, while the prevalence in the general population was much lower (24). Syphilis screening should not be based on referral status and symptoms. However, diagnosis based on serological testing for people with related risk factors is the best way to control the disease. Especially the FSW population, they are the most important source connecting the infection to the general population.

In Iran, the blood transfusion service conducts serologic tests for syphilis, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) by a sensitive and specific test, antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti- HCV), antibody to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-Ab), and VDRL. The facility is obliged to report any reactivity test results immediately. People who donate blood regularly are less likely to contract syphilis than people who donate blood for the first time (23).

The trend of syphilis infection rates in Iran was first the high prevalence rate observed in 1999–2003 (Prevalence=0.005), and then a significant decrease was observed in 2004, after which the results remained approximately unchanged. The most important reason may be the increase in the number of blood donor tests and the mandatory serological screening before marriage in each county.

Given the difficulty of syphilis diagnosis, most of the included studies used different tests which may impact the prevalence report. Some regions in the country were not represented in this study due to lack of established original studies in the area. Furthermore, all included studies were clinic or refereed based. Thus, interpretation of findings has to be with due consideration of these limitations.

Conclusion

The prevalence of syphilis is very low in Iran. Syphilis prevalence has declined nationally over the past decades. Syphilis infection is a small burden that needs to be revised in the implementation of high-cost screening programs.

Journalism Ethics considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

No financial support was revived.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Jayaraman S, Chalabi Z, Perel P, et al. (2010). The risk of transfusion-transmitted infections in sub-Saharan Africa. Transfusion, 50(2):433–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samkange-Zeeb FN, Spallek L, Zeeb H. (2011). Awareness and knowledge of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among school-going adolescents in Europe: a systematic review of published literature. BMC Public Health,11:727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitlow CB. (2004). Bacterial sexually transmitted diseases. Clin Colon Rectal Surg, 17(4):209–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radolf JD, Tramont EC, Salazar JC, Syphilis (treponema pallidum) (2015). Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases: Elsevier, p. 2684–709.e4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Heymann DL. (2008). Control of communicable diseases manual, 19th edn Washington. DC: American Public Health Association Publications. 2008:746. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Safari R, Shahesmaeili R, Nasirian M, et al. (2014). Systematic review of Iraninan studies on sexually transmitted disease. Kerman. Kerman University of Medical Sciences, 15(3):168–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khedmat H, Alavian SM, Miri SM, et al. (2009). Trends in Seroprevalence of Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, HIV, and Syphilis Infections in Iranian Blood Donors from 2003 to 2005. Hepatitis Monthly, 9(1):24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization (2012). Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs); the importance of a renewed commitment to STI prevention and control in achiving global sexual and reproductive health. Switzerland, Geneva: WHO Website, [updated 15 February, 2013; cited 7 Agust, 2015]; Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/82207/1/WHO_RHR_13.02_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kazerooni PA, Motazedian N, Motamedifar M, et al. (2014). The prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Shiraz, South of Iran: by respondent-driven sampling. Int J STD AIDS, 25(2):155–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gewirtzman A, Bobrick L, Conner K, et al. (2011). Epidemiology of sexually transmitted infections. Sexually transmitted infections and sexually transmitted diseases: Springer; 2011. p. 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Organization WH (2012). Strategies and laboratory methods for strengthening surveillance of sexually transmitted infections. Switzerland, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6(7):e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munn Z, Moola S, Riitano D, et al. (2014). The development of a critical appraisal tool for use in systematic reviews addressing questions of prevalence. Int J Health Policy Manag, 3(3):123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashemi-Shahri SM, Sharifi-Mood B, Kouhpayeh H-R, et al. (2016). Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Hospitalized Patients With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Infection and Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) in Zahedan, Southeastern Iran. Int J High Risk Behav Addict, 5(3):e28028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khomisipour G, Tahmasbi R. (1999). Infection of HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis viruses in high-risk groups of Bushehr province in 1999. Iranian South Medical Journal, 3(3):53–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nikbin M, Faghreddin N, Tawfiqi Zavareh H, et al. (2003). Prevalence of syphilis in women prisoners in Tehran province in 2001 and 2002. Iranian Journal of Forensic Medicine, 9(30):82–4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tabassi A, Salmasi AH, Sabeti A. (2004). Acquired isolated abducens nerve palsies: a retrospective study on etiology in an Iranian population. Neuro-Ophthalmology, 28(4):155–61. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sadeghi H, Arshi S, Habibzadeh S, et al. (2007). Seroepidemiology of syphilis in a population of 50–20 years in the border areas of Ardabil province. Iranian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, 12(36):75–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maleki M, Javidi Z, Mashayekhi V, et al. (2008). Serologic Evaluation of HIV-1 and Syphilis in Patients withClinical Anogenital Wart. Medical Journal of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, 51(2):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vahdani P, HOSSEINI MS, FAMILI A, et al. (2009). Prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV, and syphilis among homeless subjects older than fifteen years in Tehran. Arch Iran Med,12(5):483–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navadeh S, Mirzazadeh A, Mousavi L, et al. (2012). HIV, HSV2 and Syphilis Prevalence in Female Sex Workers in Kerman, South-East Iran; Using Respondent-Driven Sampling. Iran J Public Health, 41(12):60–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Badie BM, Yavari Z, Esmaeeli S, et al. (2013). Prevalence survey of infection with Treponema pallidum among HIV-positive patients in Tehran. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed, 3(4):334–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohammadali F, Pourfathollah AAJAoIm. (2014). Changes in frequency of HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis infections among blood donors in Tehran province 2005–2011. Arch Iran Med,17(9):613–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shahesmaeili A, Karamouzian M, Shokoohi M, et al. (2018). Symptom-based versus laboratory-based diagnosis of five sexually transmitted infections in female sex workers in Iran. AIDS Behav, 22(Suppl 1):19–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khezri M, Shokoohi M, Mirzazadeh A, et al. (2020). Early sex work initiation and its association with condomless sex and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Iran. Int J STD AIDS, 31(7):671–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO (2012). Global incidence and prevalence of selected curable sexually transmitted infections-2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75181/9789241503839_eng.pdf?sequence=1 [PubMed]

- 27.Kheirandish M, Maghsudlu M, Amini Kafiabad S, et al. (2018). Syphilis Screening in Donated Blood. Scientific Journal of Iran Blood Transfus Organ,15(1):71–86. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sadeghi Bazargani H, Arshi S, Habibzadeh S, et al. (2007). Seroepidemiology syphilis in the 50–20 year old population of the border areas of Ardabil Province. Iranian Journal of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, 12(36):75–9. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen Y-C, Liu H-Y, Li C-Y, et al. (2015). The rising trend of sexually transmitted infections among HIV-infected persons: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan, 2000 through 2010. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr, 68(4):432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Massoud M, Javidi Z, Vahid M, et al. (2008). Serological evaluation of HIV-1 and syphilis in patients with clinical genital warts. Medical Journal of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, 51(100):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rust G, Minor P, Jordan N, et al. (2003). Do clinicians screen Medicaid patients for syphilis or HIV when they diagnose other sexually transmitted diseases? Sex Transm Dis, 30(9):723–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pathela P, Braunstein SL, Blank S, et al. (2015). The High Risk of an HIV Diagnosis Following a Diagnosis of Syphilis: A Population-level Analysis of New York City Men. Clin Infect Dis, 61(2):281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Motta L, Sperhacke RD, De Gregori A, et al. (2018). Syphilis prevalence and risk factors among young men presenting to the Brazilian Army in 2016: Results from a national survey. Medicine (Baltimore), 97(47):e13309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sparling PF, Holmes KK, Mardh PA. (1990). Natural history of syphilis. NewYork: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirzazadeh A, Shokoohi M, Khajehkazemi R, et al. (2016). HIV and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in Iran: findings from the 2010 and 2015 national surveillance surveys. The 21st International AIDS Conference, Durban, South AfricaAt: Durban, South Africa. [Google Scholar]