Abstract

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a sporadic, congenital, neuro-cutaneous disorder characterized by a mosaic, capillary malformation. SWS and non-syndromic capillary malformations are both caused by a somatic activating mutation in GNAQ encoding the G protein subunit alpha-q protein. The missense mutation R183Q is the sole GNAQ mutation identified thus far in 90% of SWS-associated or isolated capillary malformations. In this study, we sequenced skin biopsies of capillary malformations from 9 patients. We identified the R183Q mutation in nearly all samples, but one sample exhibited a Q209R mutation. This new mutation occurs at the same residue as the constitutively-activating Q209L mutation, commonly seen in tumors. However, Q209R is a rare variant in this gene. To compare the effect of the Q209R mutation on downstream signaling, we performed reporter assays with a GNAQ-responsive reporter co-transfected with either GNAQ WT, R183Q, Q209L, Q209R, or C9X (representing a null allele). Q209L showed the highest reporter activation, with R183Q and Q209R showing significantly lower activation. To determine whether these mutations had similar or different downstream consequences we performed RNA-seq analysis in microvascular endothelial cells (HMEC-1) electroporated with the same GNAQ variants. The R183 and Q209 missense variants caused extensive dysregulation of a broad range of transcripts compared to the WT or null allele, confirming that these are all activating mutations. However, the missense variants exhibited very few differentially expressed genes (DEGs) when compared to each other. These data suggest that these activating GNAQ mutations differ in magnitude of activation but have similar downstream effects.

Keywords: GalphaQ, RNA sequencing, signaling

INTRODUCTION

Sturge-Weber syndrome (SWS) is a sporadic congenital disorder that affects 1 out of every 20,000 – 50,000 newborns, characterized by capillary malformations involving the skin, brain leptomeninges, and choroid of the eye [1,2]. Most individuals with SWS are born with a facial birthmark commonly known as a port-wine stain; a capillary malformation caused by an abnormal aggregation of capillaries beneath the skin, which can eventually cause severe disfiguration [3,4]. Vascular malformations on the brain surface and eye can cause severe complications including epilepsy, stroke-like events, neurological and cognitive impairment, and glaucoma [5]. Because there are no targeted therapies available for patients with SWS, treatment options are limited to the management of symptoms and complications through anticonvulsant medications, surgery to suppress seizure activity, and medications to reduce the intraocular fluid pressure to treat glaucoma. Therefore, further understanding of the disease pathogenesis will help develop targeted therapies for patients with SWS.

SWS and non-syndromic, isolated facial capillary malformations fall within a continuum of vascular malformation phenotypes. Prior to the advent of deep DNA sequencing technologies, R. Happle hypothesized that both were caused by a somatic (post-zygotic) mutation in the same gene, with the anatomic extent of the malformation and disease severity determined by the developmental stage when the mutation was acquired in utero [6]. Both SWS and non-syndromic capillary malformations have now been shown to be caused by an acquired, somatic mutation in GNAQ, encoding the protein Gαq, an alpha subunit of heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding protein (G protein) complexes [7]. The mutation, guanine to adenine at position 548, results in an amino acid substitution at position 183 from an arginine (R) to a glutamine (Q) [8]. This mutation occurs in the affected tissues of approximately 90% of SWS patients, and the same mutation is also found in 92% of non-syndromic facial capillary malformations [8]. The mutation is primarily found in the endothelial cells of capillary malformations in the skin, brain, and eyes [8,9,5,10] suggesting an endothelial cell origin of the somatic mutation. However, in some cases the mutation is also found in brain cells [11], suggesting that the mutation may be acquired in a progenitor cell of multiple cell types. Recently, somatic mutations in SWS have been identified in the GNA11 gene, encoding the related alpha subunit, Gα11 and in GNB2 encoding the beta subunit of the G protein complex [12,13]. These rare somatic mutations, acquired in other G protein complex subunits, provide additional evidence of the primacy of this signaling complex in SWS and capillary malformation pathogenesis.

The missense mutation R183Q is the sole GNAQ mutation identified thus far in affected tissues from patients with SWS or isolated capillary malformations. Since approximately 10% of capillary malformations are negative for the p.R183Q GNAQ mutation, we investigated whether other somatic mutations might cause these malformations. Here, we sequenced skin biopsies from capillary malformations from 9 patients using a panel of oncogenes (see Methods) including GNAQ. In one sample, we found a novel mutation in GNAQ, and we investigated its effects on downstream signaling.

METHODS

Tissue samples

A total of 9 skin biopsies of affected tissue were collected from 9 patients: capillary malformations either from SWS patients or from non-syndromic capillary malformations. These skin biopsies were formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) for preservation prior to usage. Tissue sections obtained from skin biopsies were deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histopathological analysis.

DNA sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was purified from FFPE tissue samples. Purification was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol for the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). We used the SureSelect XT Low Input kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) to prepare a sequencing library targeted to the exons of 151 known oncogenes using the ClearSeq Comprehensive Cancer panel (Agilent). Briefly, purified DNA was enzymatically fragmented, ligated to sequencing adaptors, and amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to generate pre-capture gDNA libraries. The pre-capture gDNA libraries were then hybridized to the biotinylated RNA baits and captured with streptavidin magnetic beads. Following capture, the target-enriched sequencing libraries were pooled and sequenced to a depth of 500x on one lane on the Illumina HiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

DNA sequencing analysis

The DNA sequencing data were analyzed according to the Broad Institutes best practices workflows for somatic short variant discovery with minor modifications to facilitate affected only sequencing. Reads were trimmed and aligned to hg19 with bowtie2. Duplicate reads were marked and removed using GATK4 Mark Duplicates. Variants were called using GATK4 MuTect2. SnpEff was used to annotate the protein-level effects of each variant.

To identify putative pathogenic somatic variants, we filtered variants by the following criteria: total coverage >200x, >5 supporting reads with the alternate allele, alternate allele frequency >1% and <50%, population allele frequency <1% (gnomAD). We also filtered variants by function, selecting for variants that were nonsense, frameshift, missense, or predicted to impact splicing.

This filtered set was analyzed to identify variants of potential interest in the pathogenesis of SWS. We first analyzed all variants affecting GNAQ and GNA11, specifically looking for recurrent gain of function mutations (R183Q, Q209L/P/R). Variants in other genes were prioritized if they were present across multiple samples. All variants that were present in at least 3 samples were searched in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC), ClinVar, and a literature review. Second, to account for the possibility that a heterozygous set of loss-of-function variants within a single gene causes SWS, genes with the highest number of variants most likely to cause loss of function were identified. The 20 genes with the highest collective number of frameshift and nonsense variants were extracted and researched through a literature review.

Plasmids

For the construction of the GNAQ mutant-expressing plasmid, the human GNAQ TrueORF Gold cDNA clone was purchased from Origene (Rockville, MD). This clone contains the full-length open reading frame of GNAQ with His-DDK tags at the 3’ end in a pCMV6-Entry vector. The tags were removed by PCR amplification using a 5’ primer outside of the ribosome binding site and the Kozak sequence while adding a BamH1 site (5’-GTCGACTGGATCCGGTACCGAGGAGATC-3’) and a 3’ primer designed to stop transcription at the correct site while adding an Mlu1 site (5’-AGGACTTACGCGTTCATTAGACCAGATTGTACTCCTTC-3’). The full-length GNAQ without the tags was directionally cloned into a pCMV6 vector through digestion with BamH1 and Mlu1. The following mutations were introduced separately into GNAQ using site-directed mutagenesis: c.548G>A (p.R183Q), c.626A>T (p.Q209L), c.626A>G (p.Q209R), and c.27C>A (p.C9X) (premature termination codon). All point mutations and the fidelity of the full-length clones were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. The reporter plasmids used for the luciferase assay were the serum response element plasmid (pSRE)–Luc (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) and pSV40-RL (Promega, Madison, WI).

Dual luciferase reporter assay after transient transfection in HEK293T cells

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured at 37°C in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM, Gibco by Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 5% CO2 and seeded at a density of 2 × 104cells/well in a 24-well plate 24 hr before transfection. HEK293T cells at 70% confluence were then co-transfected with pSRE-Luc (50 ng), pSV40-RL (5 ng), and 50 ng of either GNAQ WT, p.R183Q, p.Q209L, p.Q209R, or p.C9X using FuGENE 6 (6FUG :1DNA ratio) (Promega, Madison, WI). For the p.Q209R mutant the Gαq selective inhibitor YM254890 (Tocris, Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN) was added at different concentrations (2, 40, and 600 nM) [14] to HEK293T cells transfected with the p.Q209R construct. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cell lysates were prepared from each transfection well to measure Firefly and Renilla luciferase activity in a 96-well plate using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) on a Polarstar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany). Assays were performed in triplicate, and at least 3 independent experiments were conducted. Data are expressed as the normalized fold change in activity between test groups using the following equation: Δ Fold in activity = Average (Firefly/Renilla) from GNAQ mutant sample/ Average (Firefly/Renilla) from WT GNAQ sample. The normalized fold changes from each experiment were then averaged together and 2-way repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to determine whether there were any statistically significant differences between the experimental groups.

ERK/p-ERK immunoblotting

For immunoblotting analysis, 70% confluent HEK293T cells, seeded overnight at a density of 5 × 104cells/well in a 6-well plate, were transfected using 2.5 μg DNA/well with either GNAQ WT, p.R183Q, p.Q209L, and p.Q209R mutant plasmid, (Fugene, Promega or Lipofectamine 3000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, for transfection). In each plate, one well was also transfected with a GFP vector to confirm an average of 60% transfection efficiency in all the experiments. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were washed in cold PBS and lysed with lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors on ice. Proteins were then extracted and stored at −70 C° until immunoblotting analysis. Protein concentrations were quantified using a Bradford micro-assay protocol (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Equal amounts of total protein for each sample were loaded into each well and resolved on a 4–15% polyacrylamide gel (Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Gels, Bio-Rad). Proteins were then transferred to PVDF membranes using the Trans Blot-Turbo System (Bio-Rad) and probed with antibodies recognizing p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2), phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA) and β-tubulin as a loading control. After incubation with primary antibodies, membranes were washed with TBS and incubated in donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA). The signal was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. Data for densitometry analysis were obtained using the Doc EZ imager and Image lab software (Bio-Rad). Fiji Image J software was used for densitometric data analysis.

Gene transfer by electroporation in HMEC-1 cells and RNA sequencing analysis

Cells from a human dermal microvascular endothelial cell line, HMEC-1 (ATCC, CRL-3243), were cultured following the manufacturer instructions, in MCDB 131 supplemented with 25 mL of microvascular growth supplement (Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine, and 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HMEC-1 cells are an immortalized microvascular endothelial cell line, originally isolated from human foreskin and transfected with the pSVT vector containing the large T antigen of Simian virus 40A. Tissue culture dishes were coated with 0.2% gelatin at 37°C for at least 30 minutes prior to use. Cells were incubated at 37°C/5%CO2 and passaged when approximately 80% confluent. GNAQ WT, p.R183Q, p.Q209L, p.Q209R, or p.C9X, and GFP plasmids were delivered to HMEC-1 cells via electroporation with the Neon Transfection system (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 5 μg of plasmid DNA was mixed with 5.5 × 105 cells in 100 μL of Buffer R. Cells were electroporated using 100 μL Neon tips and the following pulse conditions: 2 pulses at 1400 V with a 20-millisecond pulse width. Following electroporation, cells were transferred to the appropriate well on a 6-well plate containing 2 mL of pre-warmed HMEC-1 media and cultured for 24 hours. Each condition was prepared in triplicate and used for RNA sequencing.

RNA extraction from HMEC-1 cells

RNA was extracted from HMEC-1 cells 24 hours after electroporation. Cells were lysed and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini-isolation kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen).

Concentrations of RNA were quantified by Qubit (ThermoFisher) fluorometric assay. RNA integrity number (RIN) was determined by Tapestation (Agilent).

RNA sequencing and analysis

Extracted RNA from HMEC-1 cells was submitted to Novogene for mRNA library preparation and sequencing with 150bp paired-end reads on a NovaSeq6000 for a total of 6Gbp per sample. Sequencing data were analyzed using the nf-core/rnaseq module (version 3.4) [15]. The nf-core/rnaseq pipeline contains 10 major processing steps: 1) raw read quality control using FastQC; 2) extraction of UMI sequences from reads with UMI-tools; 3) trimming of sequencing reads to remove adapters and low quality bases from the end of reads using Trim Galore!; 4) removal of genomic contaminants with BBSplit; 5) removal of ribosomal RNAs with SortMeRNA; 6) alignment and quantification using STAR and Salmon respectively; 7) sorting and index alignments with SAMtools; 8) deduplication with UMI-tools using UMIs from step 2; 9) transcript assembly and quantification with StringTie; 10) final quality control metrics generated with RSeQC, Qualimap, dupRadar, Preseq, and DEseq2. After data processing, the aligned reads were examined to confirm that each sample expressed the corresponding form of mutant GNAQ. This analysis revealed that one sample transfected with GNAQ Q209L showed minimal expression of the mutant GNAQ (Fig. S1), therefore this sample was removed from subsequent analysis. Normalized feature counts were imported into DEseq2 for further analysis. DEseq2 estimates the variance-mean dependence of transcript counts between samples based on a model using the negative binomial distribution [16]. A DEseq2 model was built using the identity of the transfected plasmid, the replicate batch, and the normalized GNAQ counts which were discretized into 5 groups from low to high expression. Differential gene expression was calculated for each pairwise comparison between mutant groups. The top 100 differentially expressed genes were used for gene ontology enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis using ShinyGo, version 0.741 [17]. RNA sequencing data are available in the GEO data repository (GSE199978).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism 9.3 (GraphPad Software). Results are presented as the mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed using either one-way or repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s multiple comparison test and Student t test unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Sequencing results of skin biopsies of capillary malformations

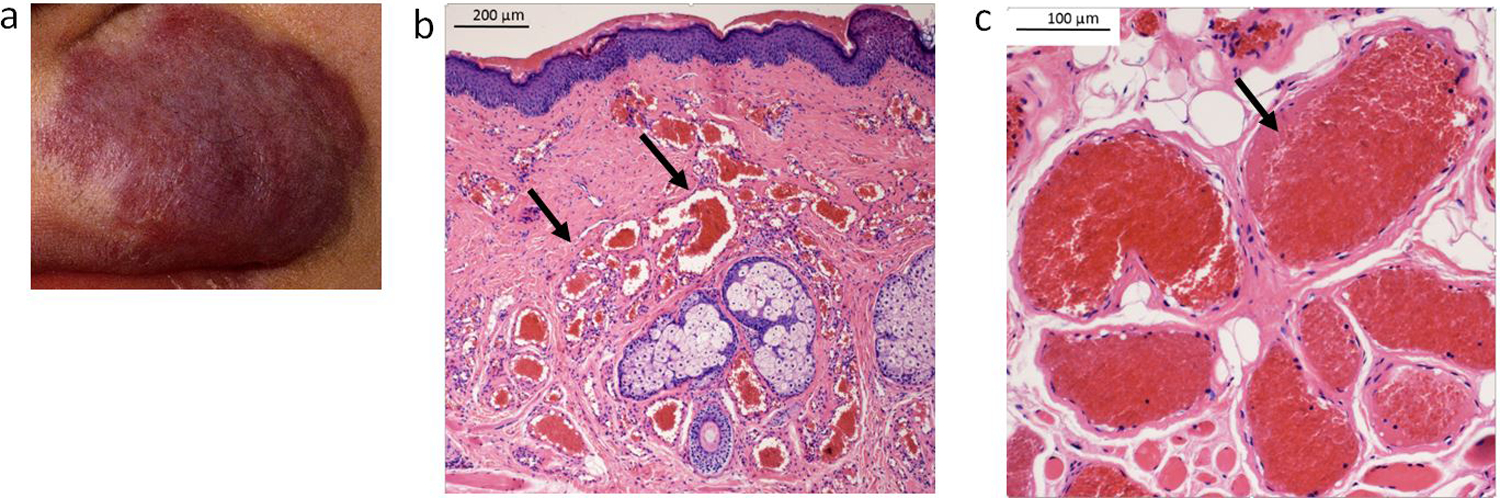

We obtained tissue samples from 9 patients exhibiting a capillary malformation from non-syndromic (isolated) cases or SWS. After performing DNA sequencing analysis, we identified the SWS/capillary malformation-associated p.R183Q GNAQ somatic mutation in 8 of 9 capillary malformation tissue samples from SWS/capillary malformation patients (Table 1). However, we identified a novel p.Q209R GNAQ mutation in one sample; a facial capillary malformation of a 19 y/o female (Fig. 1a–c). Histological analysis of the affected tissue showed dilated vessels with very little smooth muscle, arranged in lobules (Fig. 1b and c). There was no sign of vessel mural smooth muscle hypertrophy and no increase in mitotic activity. Thus, this sample was a typical non-syndromic (isolated) capillary malformation.

Table 1.

GNAQ mutations identified in Sturge-Weber syndrome/capillary malformation samples

| Sample ID | GNAQ Mutation | Ref Reads | Alt Reads | Allele Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3217 | p.R183Q | 606 | 67 | 10.0 |

| 3218 | p.R183Q | 427 | 43 | 9.1 |

| 3219 | p.R183Q | 468 | 25 | 5.1 |

| 3220 | p.R183Q | 643 | 37 | 5.4 |

| 3222 | p.R183Q | 897 | 47 | 5.0 |

| 3223 | p.R183Q | 1242 | 41 | 3.2 |

| 3224 | p.R183Q | 1032 | 36 | 3.4 |

| 3225 | p.Q209R | 567 | 113 | 16.6 |

| 3229 | p.R183Q | 267 | 19 | 7.1 |

Mutations were identified from targeted sequencing of the exons of GNAQ. The reported read counts for the reference and alternate alleles were determined after deduplication using unique molecular identifiers (UMIs).

Fig. 1:

Images of a facial capillary malformation in a patient carrying the Q209R mutation. a) The clinical photo (patient 3225) shows the location of the lesion on the upper left lip. There is mild associated soft tissue hypertrophy of the involved area, at least in part due to dilation of the component vessels within the subcutis. b and c) Microscopic examination revealed dilated capillaries and small venules congested with erythrocytes (as indicated by the black arrows) distributed within the involved dermis (b, original mag 40x, scale bar 200 μm) and subcutis (c, original mag 100x, scale bar 100 μm) of the lip, characteristic of port-wine stain (hematoxylin & eosin).

GNAQ p.Q209R mutation results in moderate activation of Gαq downstream signaling pathways

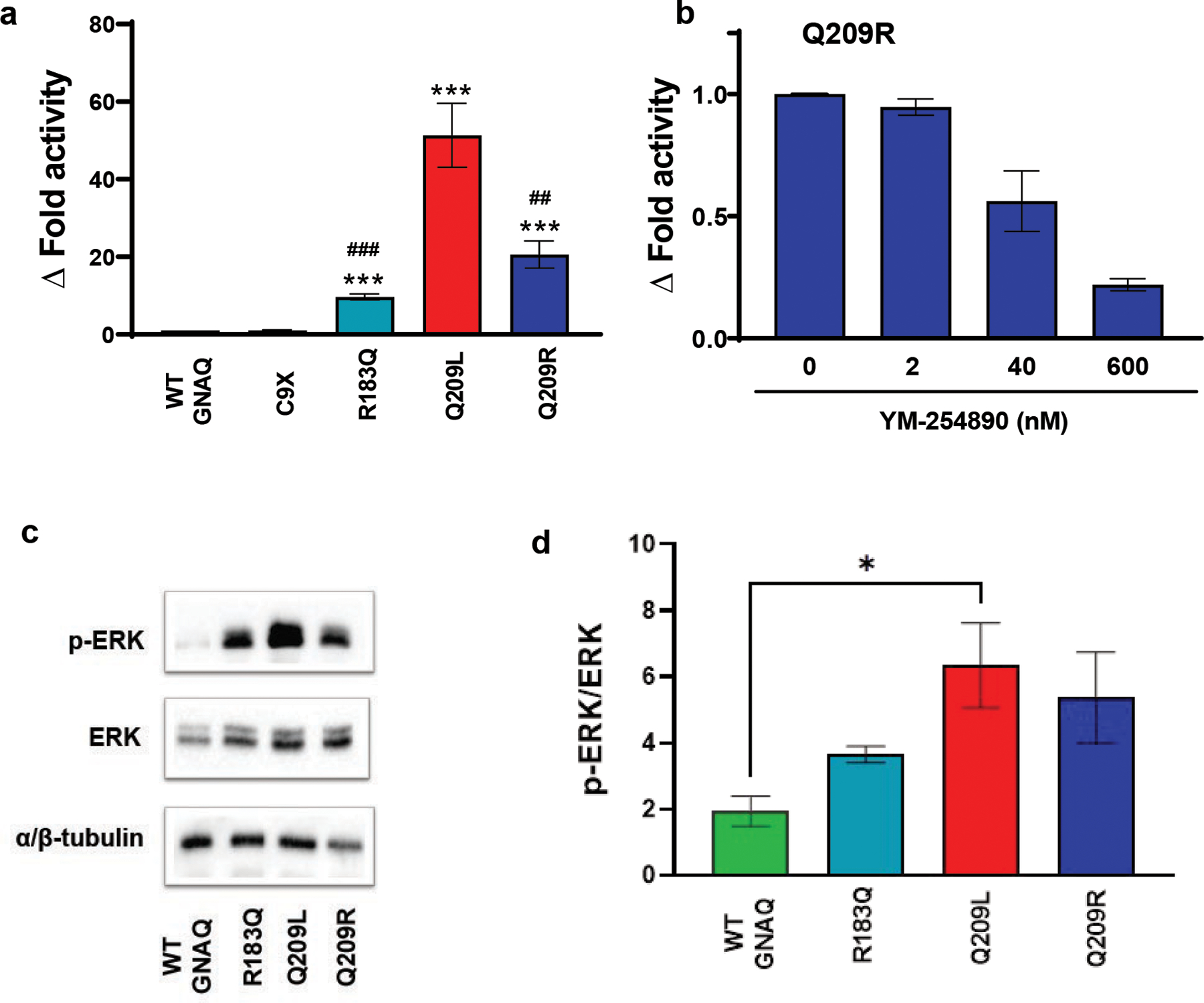

The p.Q209R variant occurs at the same codon as the most common GNAQ mutation in cancer, p.Q209L, but the arginine substitution is a rare variant (1.2% of GNAQ mutations) in the COSMIC database (Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) [18]. Previous studies have indicated that constitutive activation of Gαq by somatic GNAQ mutations such as Q209L or R183Q activates MAPK/ERK and JNK signaling pathways [19,20] and induces serum response element (SRE)-dependent gene transcription [21]. Therefore, SRE reporter luciferase assays have been successfully utilized to determine the strength activation of the G protein Gαq caused by somatic mutation of GNAQ [8,22]. To determine whether the novel p.Q209R GNAQ mutation also results in constitutive activation of Gαq and to assess the strength of activation, we first performed the SRE luciferase reporter assay, using our established in vitro model in HEK293T cells co-transfected with the reporter plasmid and either GNAQ WT or p.R183Q (the common SWS-associated mutation), p.Q209L (the most common GNAQ mutation in cancer), p.Q209R (our newly discovered mutation), or p.C9X (an early stop codon mutant to serve as a null allele).

Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells transfected with either the WT construct or the null mutation (C9X) exhibited negligible luciferase signal, indicating that under these unstimulated conditions, there was little to no constitutive activity through this pathway. Cells transfected with the p.Q209R GNAQ plasmid exhibited a 20-fold increase in luciferase signal compared to WT or null plasmids, while p.Q209L and p.R183Q GNAQ plasmids induced increases of 50- and 10-fold, respectively (***p<0.0001 p.R183Q, p.Q209L, p.Q209R, vs. WT GNAQ, Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Q209R moderately activates downstream G-protein signaling. a For the luciferase reporter assays, we transfected human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293T) with a GNAQ-responsive luciferase reporter co-transfected with either GNAQ WT, R183Q, Q209L, Q209R, or C9X (premature termination codon). Compared to WT GNAQ or null alleles, expression of Q209R induced a 20-fold increase in the luciferase activity. Similarly, Q209L and R183Q induced increases of 50- and 10-fold, respectively (***p < 0.0001 each mutant vs. WT GNAQ, ###p ≤0.0001, ##p < 0.01 R183Q and Q209R vs. Q209L, respectively, n = 9). b Incubation with various concentrations of small molecule Gαq inhibitor YM-254890 in HEK293T cells, co-transfected with Q209R, resulted in dose-dependent decrease of luciferase activity; n = 6. c Representative blots indicate a increase of MAPK phosphorylation in cells transfected with GNAQ mutants (*p < 0.05 WT GNAQ vs. Q209L, n = 3). d Graphical representation of p-ERK/ERK signaling seen in panel c

The specific small molecule Gαq inhibitor, YM-254890, suppresses luciferase signal in the SRE-reporter assay induced by activating mutations in GNAQ, thereby validating the use of this assay as a measure of signal derived from Gαq [14,23]. However, unlike other GNAQ activating mutations, our novel (new in SWS) p.Q209R mutation does not appear to have ever been investigated with the YM-254890 inhibitor. Therefore, we tested the effect of YM-254890 in cells transfected with p.Q209R and found that the SRE-mediated increase in luciferase activity was inhibited in a dose dependent manner (Fig. 2b). The results of this experiment validate that p.Q209R also activates Gαq [14].

These data indicate that p.Q209R GNAQ is also a gain-of-function mutation promoting Gαq constitutive activity (Fig. 2). Moreover, our data confirm that the GNAQ p.Q209L mutation is the strongest mutation of those assayed with regard to Gαq signaling, (p=0.0049 and p=0.0001; p.Q209L vs. p.Q209R and p.R183Q, respectively). By contrast, both p.R183Q and p.Q209R exhibited significantly weaker activation. The fact that p.Q209R was significantly weaker than p.Q209L was particularly surprising given the fact that the p.Q209R mutation occurs at the same amino acid residue as the common tumor mutation, p.Q209L.

To further compare the strength of activation of the p.Q209R mutation versus the other relevant GNAQ mutations, we performed western blot analysis measuring the ratio of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) to total ERK in HEK293T cells. As expected, there was a significant increase in p-ERK expression in cells expressing the p.Q209L GNAQ mutation (*p<0.037 WT vs. p.Q209L GNAQ, n=3). Although the average pERK expression was higher in HEK293T cells expressing p.Q209R and p.R183Q GNAQ compared with WT GNAQ, these changes were not significant (Fig.2c and d). Here again, the downstream effects of the novel p.Q209R mutation are more similar to the common SWS mutation, p.R183Q, than to the common cancer mutation, p.Q209L, at the same residue.

RNA-seq in HMEC-1 cells

The experiments above were performed in a heterologous cell system to take advantage of high transfection efficiency, especially useful for the co-transfection of the reporter gene and the GNAQ cDNA constructs. To determine whether these different mutations in GNAQ produced similar or distinct transcriptional programs, we turned to a more relevant cell type for SWS. We electroporated the human microvascular endothelial cell line (HMEC-1) with the plasmids containing either WT GNAQ or one of the following GNAQ variants: p.R183Q, p.Q209R, p.Q209L, and p.C9X, to assess any endothelial-specific transcriptional response differences.

We prepared biological triplicates for each experimental group and subjected them to RNA-sequencing. We aligned the resulting reads to the transcriptome of hg38 and used alignments to GNAQ to evaluate whether electroporation was successful. These alignments confirmed the presence of the expected variant in 14 of 15 samples (Fig. S1). The third replicate in the p.Q209L group had a low read count compared to the other p.Q209L replicates (751 vs. 224345 and 294227, Fig. S1d), indicating poor electroporation efficiency. Therefore, this sample was excluded from further analysis.

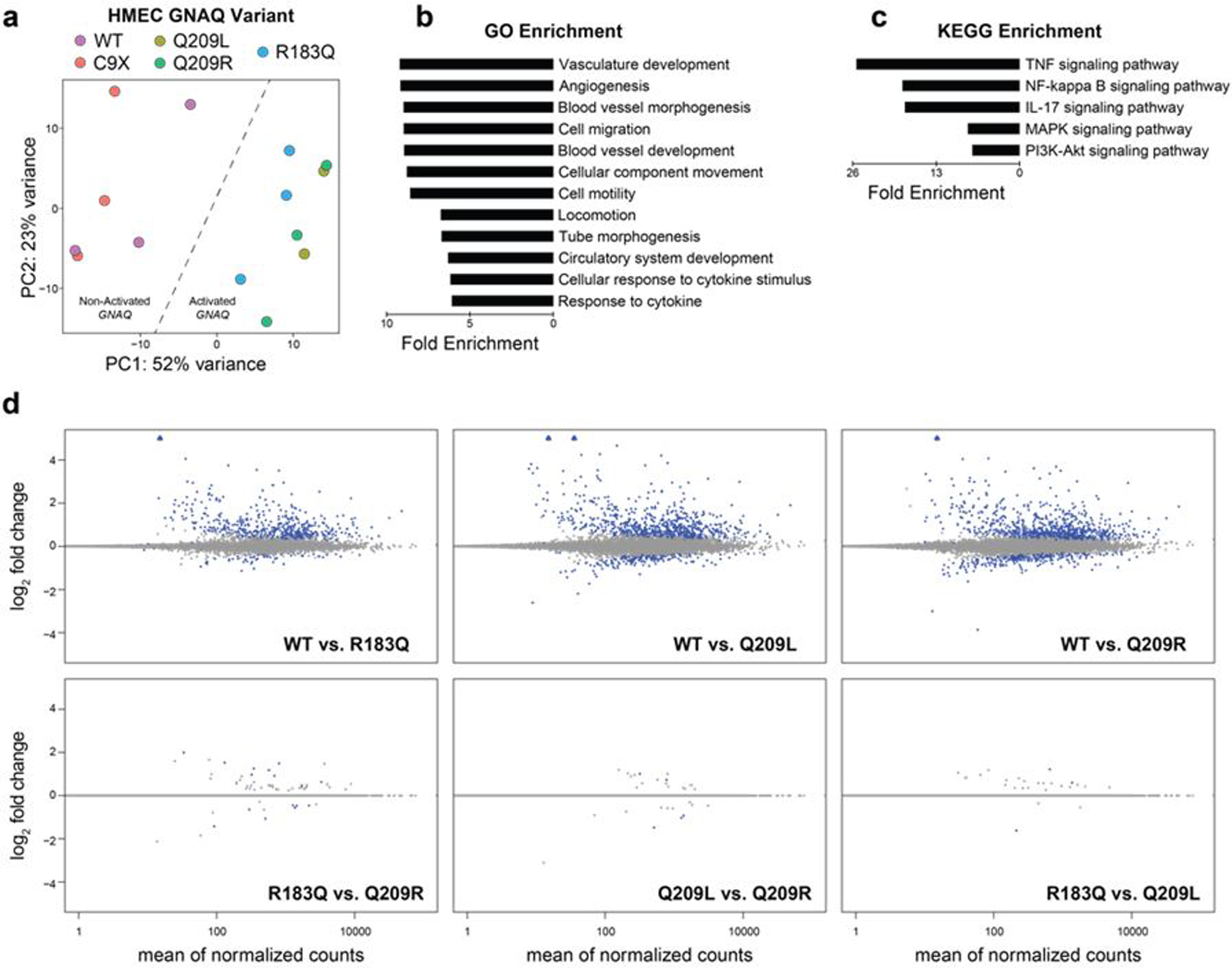

We used the remaining samples to determine differentially expressed (DE) genes for each pairwise comparison between groups. Principal component analysis revealed a clear separation between activated (p.R183Q, p.Q209L, and p.Q209R) and non-activated (WT and p.C9X) GNAQ (Fig. 3a). We next used the top 100 DE genes between the WT and p.Q209R groups for GO and KEGG enrichment to identify enriched biological processes and pathways respectively that correspond to the identified DE genes. The GO enrichment analysis returned several vascular-related terms including the top 3 enriched terms: Vasculature development, Angiogenesis, and Blood vessel morphogenesis (Fig. 3b). KEGG enrichment revealed cytokine signaling pathways (TNF, NF-kappa B, and IL-17) as well as MAPK and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways (Fig. 3c), both of which have been implicated in vascular malformations. Pairwise comparisons of DE genes between each group revealed numerous DE genes between mutant-activated and non-activated GNAQ; however, there were very few DE genes when comparing any two groups with an activating GNAQ mutation (Fig. 3d, Fig. S2). Notably, the expression of ANGPT2 (encoding Angiopoietin 2) was significantly increased in all three GNAQ groups with an activating mutation, consistent with previous work on p.R183Q [24]. Together, these data indicate that p.R183Q, p.Q209L, and p.Q209R affect similar transcriptional programs in endothelial cells.

Fig. 3.

Activating mutations in GNAQ produce similar transcriptomic effects. (a) Principal component analysis of RNA-seq data produced from HMEC-1 cells transfected with WT or mutant GNAQ plasmids. (b, c) Top enriched terms for gene ontology (b) and KEGG signaling pathway (c) using the top 100 differentially expressed genes between WT and Q209R groups. Enriched terms are sorted by fold enrichment and all terms shown have p < 1E-5. (d) MA plots of RNA-seq data for pairwise comparisons between WT and mutant GNAQ (top) and comparisons between mutations (bottom). Blue circles are statistically significant DEGs, blue triangles are significant DEGs off the scale, grey circles are not significant

DISCUSSION

The most common mutation found in capillary malformation with or without SWS is GNAQ, p.R183Q found in approximately 90% of capillary malformations and SWS cases. The goal of our study was to attempt to identify novel genetic mutations that may be responsible for capillary malformations. Sequencing results of skin biopsies of capillary malformations confirmed the presence of the p.R183Q mutation in 8 of 9 samples, but also identified a novel p.Q209R mutation in one sample. To our knowledge, this is the first report of this somatic mutation in a capillary malformation. Although this mutation is most likely a rare cause of capillary malformations, our analysis of its signaling consequences has shed some light on isolated capillary malformation, and by analogy, SWS pathogenesis.

GNAQ is commonly somatically mutated in multiple, different cell types, as observed in a variety of tumors. Although the p.R183Q mutation is also found in tumors, per the COSMIC database, by far the most common somatic GNAQ mutation in cancer is p.Q209L. The R183 and Q209 residues in the protein are involved in GTP hydrolysis, the auto-regulatory “off” switch of G-protein activation. GNAQ mutations at the Q209 or R183 residue reduce hydrogen bonding between Gαq and guanosine diphosphate (GDP), which is needed for assembly of the GDP-Gαβγ ‘inactive’ complex, thereby increasing activity of the Gαq subunit of the G-protein coupled receptor [7,25.] The p.Q209L mutation causes the complete loss of GTPase activity and constitutive activation of the subunit [7]. By contrast, the p.R183Q mutation leads to slower GTPase activity and thus, moderate activation [26,27]. Prolonged activation of Gαq causes upregulation of downstream signaling pathways, determined in large part by the specific cellular context.

Somatic mutations at the GNAQ p.Q209 residue are also acquired in certain vascular tumors. The GNAQ p.Q209R mutation, the same mutation identified in this report, is found in benign vascular tumors such as cherry angiomas [28] and circumscribed choroidal hemangioma [29]. However, the effect of this mutation on downstream signaling is not known. By two measures of downstream activation, GNAQ p.R183Q exhibits a much lower magnitude of activation than the constitutively-active p.Q209L [8], which has never been found in SWS or capillary malformations. Although this novel p.Q209R mutation occurs at the same residue (209) as the more common p.Q209L tumor-associated mutation, this less common arginine variant exhibits a lower activation level. This leads to the question whether p.Q209L can even be tolerated in the vascular endothelium. The p.Q209L somatic mutation has been found in a single case of anastomosing hemangioma, a benign, vascular tumor generally of adult onset [30]. The restricted mutation spectrum in GNAQ for SWS and isolated capillary malformations suggests that the strongly activating p.Q209L mutation might not be tolerated during vascular development in utero. This observation supports the hypothesis that acquisition of a fully activating GNAQ mutation in the endothelium during development would be lethal, even in the mosaic state.

We also wanted to understand the factors underlying the specificity of GNAQ mutations observed in SWS, choroidal hemangioma, and uveal melanoma (R183Q, Q209R, and Q209L/P respectively). The near-perfect correlation between these diseases and a specific GNAQ mutation may be the result of differences in activation strength, or the different GNAQ mutations may have distinct functional consequences that favor the development of one pathology over the others. When the mutants are expressed in endothelial cells, gene set enrichment analysis of these DEGs implicates signaling through EGFR, KRAS, and MTOR, consistent with some of the known downstream effectors of GNAQ signaling. KEGG analysis of DEGs between WT and any of the activating mutants revealed several dysregulated signaling pathways, including MAPK and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways that are implicated in vascular malformations. However, the DEGs between the different activating mutations was minimal. These combined data suggest that the effects of the different activating mutations are one of magnitude and not downstream consequences. The downstream effects of these mutations in different cell types could differ more significantly depending on the biochemical and cellular context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by The Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium (U54NS065705) of the NCATS Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN). RDCRN is an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR) and NCATS, funded through a collaboration between NCATS and NINDS. We also thank the Sturge-Weber Foundation for encouragement and support.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Desai S, Glasier C (2017) Sturge-Weber Syndrome. N Engl J Med 377 (9):e11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMicm1700538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bachur CD, Comi AM (2013) Sturge-weber syndrome. Curr Treat Options Neurol 15 (5):607–617. doi: 10.1007/s11940-013-0253-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Couto JA, Huang L, Vivero MP, Kamitaki N, Maclellan RA, Mulliken JB, Bischoff J, Warman ML, Greene AK (2016) Endothelial Cells from Capillary Malformations Are Enriched for Somatic GNAQ Mutations. Plast Reconstr Surg 137 (1):77e–82e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000001868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabeti S, Ball KL, Burkhart C, Eichenfield L, Fernandez Faith E, Frieden IJ, Geronemus R, Gupta D, Krakowski AC, Levy ML, Metry D, Nelson JS, Tollefson MM, Kelly KM (2021) Consensus Statement for the Management and Treatment of Port-Wine Birthmarks in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. JAMA dermatology 157 (1):98–104. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang L, Couto JA, Pinto A, Alexandrescu S, Madsen JR, Greene AK, Sahin M, Bischoff J (2017) Somatic GNAQ Mutation is Enriched in Brain Endothelial Cells in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Pediatr Neurol 67:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Happle R (1987) Lethal genes surviving by mosaicism: a possible explanation for sporadic birth defects involving the skin. J Am Acad Dermatol 16 (4):899–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimple AJ, Bosch DE, Giguere PM, Siderovski DP (2011) Regulators of G-protein signaling and their Galpha substrates: promises and challenges in their use as drug discovery targets. Pharmacol Rev 63 (3):728–749. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, Baugher JD, Frelin LP, Cohen B, North PE, Marchuk DA, Comi AM, Pevsner J (2013) Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med 368 (21):1971–1979. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1213507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakashima M, Miyajima M, Sugano H, Iimura Y, Kato M, Tsurusaki Y, Miyake N, Saitsu H, Arai H, Matsumoto N (2014) The somatic GNAQ mutation c.548G>A (p.R183Q) is consistently found in Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Hum Genet 59 (12):691–693. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2014.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y, Peng C, Huang L, Xu L, Ding X, Liu Y, Zeng C, Sun H, Guo W (2021) Somatic GNAQ R183Q mutation is located within the sclera and episclera in patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2020-317287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundaram SK, Michelhaugh SK, Klinger NV, Kupsky WJ, Sood S, Chugani HT, Mittal S, Juhasz C (2017) GNAQ Mutation in the Venous Vascular Malformation and Underlying Brain Tissue in Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Neuropediatrics 48 (5):385–389. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1603515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fjaer R, Marciniak K, Sundnes O, Hjorthaug H, Sheng Y, Hammarstrom C, Sitek JC, Vigeland MD, Backe PH, Oye AM, Fosse JH, Stav-Noraas TE, Uchiyama Y, Matsumoto N, Comi A, Pevsner J, Haraldsen G, Selmer KK (2021) A novel somatic mutation in GNB2 provides new insights to the pathogenesis of Sturge-Weber syndrome. Hum Mol Genet 30 (21):1919–1931. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddab144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Polubothu S, Al-Olabi L, Carmen Del Boente M, Chacko A, Eleftheriou G, Glover M, Jimenez-Gallo D, Jones EA, Lomas D, Folster-Holst R, Syed S, Tasani M, Thomas A, Tisdall M, Torrelo A, Aylett S, Kinsler VA (2020) GNA11 Mutation as a Cause of Sturge-Weber Syndrome: Expansion of the Phenotypic Spectrum of Galpha/11 Mosaicism and the Associated Clinical Diagnoses. J Invest Dermatol 140 (5):1110–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2019.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takasaki J, Saito T, Taniguchi M, Kawasaki T, Moritani Y, Hayashi K, Kobori M (2004) A novel Galphaq/11-selective inhibitor. J Biol Chem 279 (46):47438–47445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408846200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewels PA, Peltzer A, Fillinger S, Patel H, Alneberg J, Wilm A, Garcia MU, Di Tommaso P, Nahnsen S (2020) The nf-core framework for community-curated bioinformatics pipelines. Nat Biotechnol 38 (3):276–278. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0439-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S (2014) Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15 (12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ge SX, Jung D, Yao R (2020) ShinyGO: a graphical gene-set enrichment tool for animals and plants. Bioinformatics 36 (8):2628–2629. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bamford S, Dawson E, Forbes S, Clements J, Pettett R, Dogan A, Flanagan A, Teague J, Futreal PA, Stratton MR, Wooster R (2004) The COSMIC (Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer) database and website. Br J Cancer 91 (2):355–358. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamauchi J, Itoh H, Shinoura H, Miyamoto Y, Tsumaya K, Hirasawa A, Kaziro Y, Tsujimoto G (2001) Galphaq-dependent activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4/c-Jun N-terminal kinase cascade. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 288 (5):1087–1094. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thomas AC, Zeng Z, Riviere JB, O’Shaughnessy R, Al-Olabi L, St-Onge J, Atherton DJ, Aubert H, Bagazgoitia L, Barbarot S, Bourrat E, Chiaverini C, Chong WK, Duffourd Y, Glover M, Groesser L, Hadj-Rabia S, Hamm H, Happle R, Mushtaq I, Lacour JP, Waelchli R, Wobser M, Vabres P, Patton EE, Kinsler VA (2016) Mosaic Activating Mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ Are Associated with Phakomatosis Pigmentovascularis and Extensive Dermal Melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol 136 (4):770–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2015.11.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagae R, Sato K, Yasui Y, Banno Y, Nagase T, Ueda H (2011) Gs and Gq signalings regulate hPEM-2-induced cell responses in Neuro-2a cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 415 (1):168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maziarz M, Leyme A, Marivin A, Luebbers A, Patel PP, Chen Z, Sprang SR, Garcia-Marcos M (2018) Atypical activation of the G protein Gα(q) by the oncogenic mutation Q209P. J Biol Chem 293 (51):19586–19599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.005291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuo A, Matsumoto S, Nagano M, Masumoto KH, Takasaki J, Matsumoto M, Kobori M, Katoh M, Shigeyoshi Y (2005) Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel Gq-coupled orphan receptor GPRg1 exclusively expressed in the central nervous system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 331 (1):363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang L, Bichsel C, Norris AL, Thorpe J, Pevsner J, Alexandrescu S, Pinto A, Zurakowski D, Kleiman RJ, Sahin M, Greene AK, Bischoff J (2022) Endothelial GNAQ p.R183Q Increases ANGPT2 (Angiopoietin-2) and Drives Formation of Enlarged Blood Vessels. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 42 (1):e27–e43. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.316651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bichsel CA, Goss J, Alomari M, Alexandrescu S, Robb R, Smith LE, Hochman M, Greene AK, Bischoff J (2019) Association of Somatic GNAQ Mutation With Capillary Malformations in a Case of Choroidal Hemangioma. JAMA Ophthalmol 137 (1):91–95. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2018.5141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martins L, Giovani PA, Rebouças PD, Brasil DM, Haiter Neto F, Coletta RD, Machado RA, Puppin-Rontani RM, Nociti FH Jr., Kantovitz KR (2017) Computational analysis for GNAQ mutations: New insights on the molecular etiology of Sturge-Weber syndrome. J Mol Graph Model 76:429–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2017.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Litosch I (2016) Decoding Galphaq signaling. Life Sci 152:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klebanov N, Lin WM, Artomov M, Shaughnessy M, Njauw CN, Bloom R, Eterovic AK, Chen K, Kim TB, Tsao SS, Tsao H (2019) Use of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing to Identify Activating Hot Spot Mutations in Cherry Angiomas. JAMA dermatology 155 (2):211–215. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snellings DA, Gallione CJ, Clark DS, Vozoris NT, Faughnan ME, Marchuk DA (2019) Somatic Mutations in Vascular Malformations of Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia Result in Bi-allelic Loss of ENG or ACVRL1. Am J Hum Genet 105 (5):894–906. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bean GR, Joseph NM, Gill RM, Folpe AL, Horvai AE, Umetsu SE (2017) Recurrent GNAQ mutations in anastomosing hemangiomas. Mod Pathol 30 (5):722–727. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2016.234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

WEBSITES

- ClinVar: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/

- COSMIC: https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.