Abstract

Objective:

Delirium in critically ill children is associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality. Little is known about the lingering effects of pediatric delirium in survivors after hospital discharge. The primary objective of this study was to determine whether children with delirium would have a higher likelihood of all-cause pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) readmission within one calendar year, when compared to children without delirium.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting:

Tertiary care, mixed PICU at an urban academic medical center.

Patients:

Index admissions included all children admitted between September 2014 and August 2015. For each index admission, any readmission occurring within one year after PICU discharge was captured.

Intervention:

Every child was screened for delirium daily throughout the PICU stay.

Measurements and Main Results:

Amongst 1145 index patients, 166 children (14.5%) were readmitted at least once. Bivariate analyses compared patients readmitted within one year of discharge to those not readmitted: complex chronic conditions (CCC), increased severity of illness, longer PICU length of stay, need for mechanical ventilation, age <6 months, and a diagnosis of delirium were all associated with subsequent readmission. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to describe adjusted odds ratios for readmission. The primary exposure variable was number of delirium days. After controlling for confounders, critically ill children who experienced greater than two delirium days on index admission were more than twice as likely to be readmitted (aOR 2.2, CI 1.1-4.4, p=0.023). A dose-response relationship was demonstrated as children with longer duration of delirium had increased odds of readmission.

Conclusions:

In this cohort, delirium duration was an independent risk factor for readmission in critically ill children. Future research is needed to determine if decreasing prevalence of delirium during hospitalization can decrease need for PICU readmission.

Keywords: pediatric critical care, Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium (CAPD), pediatric, delirium, readmissions, intensive care, critical care

Tweet:

#Delirium duration is an independent risk factor for readmission in critically ill children. Future research is needed to determine if decreasing delirium rates can decrease need for #PICU readmission.

INTRODUCTION

As defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), delirium is an acute and fluctuating disturbance in attention, cognition, and awareness that develops within the context of an underlying medical illness or its treatment (1). While characteristically a transient condition, delirium has been strongly associated with in-hospital complications and increased mortality in both adult and pediatric populations (2-4). In adults, delirium has also been linked to post-discharge morbidity (5,6). Delirium in critically ill children has been independently associated with increased length of hospital stay, increased duration of mechanical ventilation, greater hospital costs, and increased in-hospital mortality (4,7-10).

While the literature regarding delirium-related outcomes in the adult population is extensive, there is a relative paucity of literature concerning outcomes after pediatric delirium. Little is known about the lingering effects of delirium in pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) survivors after hospital discharge (4,11). To date, research focusing on PICU readmissions has not included delirium in analyses.

Reducing pediatric readmissions is a critically important undertaking in improving outcomes of childhood illness. Pediatric readmissions have been associated with increased costs, greater hospital length of stay, and higher mortality (12,13). For survivors of childhood critical illness, the psychosocial effects of admission to the PICU have proven to be long-standing and complex (14,15). The combination of these factors has firmly established readmission rates as a quality metric of hospital care (13,16). The relationship between pediatric delirium and future readmissions to the PICU is a crucial knowledge gap to address.

In this study, we sought to determine whether delirium in critically ill children was independently associated with subsequent need for readmission. We hypothesized that children who experienced delirium during their PICU stay would have a higher likelihood of all-cause PICU readmission within one calendar year post-discharge, when compared to subjects who did not experience delirium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective single-site cohort study took place in a tertiary care, mixed PICU at an urban academic medical center. All children admitted between September 1, 2014 and August 31, 2015 were included as “index admissions.” Findings from this unique cohort were previously published in a study authored by Traube et al (11); however, only in-hospital outcomes were assessed. Therefore, for the purpose of this study, data collection was extended to capture all readmissions that occurred within one year following PICU discharge of this index cohort. All readmission data reported here are novel and have not been previously described. The Weill Cornell Medical College Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this minimal risk study (IRB# 1405015134) with waiver of requirement for informed consent.

On index admission, demographic data including age, sex, primary diagnosis, and need for mechanical ventilation were collected. Patients with prior admissions (occurring within one year before the index admission to our single center) were identified and excluded from further analyses. As a surrogate for illness severity on admission, a Pediatric index of Mortality-3 (PIM3) score (17) was calculated and split into tertiles to represent mild, moderate and severe illness. Pre-existing complex medical conditions were categorized as “complex chronic conditions” (CCCs) as originally defined in the literature by Feudtner et al (18), and quantified using a diagnoses list previously developed by Virtual Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Performance System (VPS) analysis (19). (CCCs have been identified as the strongest predictor of PICU readmission, with increasing numbers of CCCs directly related to increasing readmission risk) (20). Length of stay and in-hospital mortality were quantified upon PICU discharge.

Throughout the PICU stay, each child was screened for delirium twice daily, using the Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium (CAPD) (21). Recommended by the European Society of Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care (ESPNIC), the CAPD is an observational, well-validated tool widely used for assessment of pediatric delirium (8,22-25). Children who were diagnosed with delirium on at least one day during the index admission were categorized as “ever delirious” and number of delirious days was quantified. The Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS) was used to determine coma status, and delirium subtypes (26). The RASS is a 10-point scale, ranging from unarousable (−5), through alert and calm (0), to combative (+4) (27). Children with a RASS score of −4 or −5 were classified as “comatose”, as they were too deeply sedated to be evaluated for delirium. Delirious children with a RASS score between −3 and 0 were characterized as experiencing “hypoactive” delirium, while a RASS score between +1 and +4 denoted “hyperactive” delirium. “Mixed” delirium was used in the case of delirious children with RASS scores including both negative and positive numbers.

Granular data were similarly collected for each subsequent hospital readmission to our single center that occurred up to one calendar year after the index discharge. For each readmission, the primary diagnosis was noted, PIM3 score was calculated, and daily delirium status was collected. Length of stay and in-hospital mortality were again quantified upon PICU discharge after readmission.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients at index admissions were described as N (%) or mean (sd), median [min, max]. Characteristics of index admissions were also descriptively compared to characteristics of initial readmissions. Chi-square/Fisher's Exact tests or independent two-sample t-tests/Wilcoxon rank-sum tests (as appropriate) were utilized to compare patients readmitted within one year of discharge from index admission to those not readmitted within this time frame. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed modelling any readmission within one year of index admission, controlling for variables defined a priori based on the PICU readmission literature. The primary exposure variable was number of delirium days, categorized as none, 1-2, and greater than two days. All p-values were two-sided with statistical significance evaluated at the 0.05 alpha level. Analyses were performed in R version 4.0.2.

RESULTS

Study Cohort

From September 1, 2014 through August 31, 2015, 1243 unique patients were admitted to the PICU. Twenty-two patients did not survive to discharge. After excluding patients with prior admissions (n=76), 1145 unique subjects were available for inclusion in the index cohort. Approximately 57% of the children were male; a majority (60%) were less than 5 years old. Forty-seven percent were admitted with a primary diagnosis of respiratory failure or insufficiency. Approximately half (47%) had prior CCCs; of those children with a CCC, most (75%) only had one. Severity of illness, indicated by the median probability of mortality, was 1.2% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Description of Study Cohort

| Characteristic | Overall (N=1145) |

|---|---|

| Gender (n, %) | |

| Female | 496 (43.3%) |

| Male | 649 (56.7%) |

| Age (n, %) | |

| <6 months | 192 (16.8%) |

| 6 months or older | 953 (83.2%) |

| Admitting diagnosis (n, %) | |

| Cardiac disease | 91 (7.9%) |

| Hematologic/Oncologic disorder | 53 (4.6%) |

| Infectious/inflammatory | 118 (10.3%) |

| Neurologic disorder | 273 (23.8%) |

| Renal/Metabolic disorder | 75 (6.6%) |

| Respiratory insufficiency/failure | 535 (46.7%) |

| Complex Chronic Condition (n, %) | |

| None | 602 (52.6%) |

| 1 | 409 (35.7%) |

| 2 or more | 134 (11.7%) |

| Probability of mortality | |

| Mean (%, SD) | 2% (6%) |

| Median [%, range] | 1.2% [0.05%-100%] |

| PICU length of stay | |

| Median [days, range] | 3 [1-79] |

| Mechanical Ventilation (n, %) | 433 (37.8%) |

| Ever Delirious (n, %) | 162 (14.1%) |

| Hypoactive Delirium | 92 (57%) |

| Mixed Delirium | 63 (39%) |

| Hyperactive Delirium | 7 (4%) |

| Readmission within 1 Year (n, %) | 166 (14.5%) |

Characteristics of Readmitted Patients

One hundred and sixty-six children were readmitted at least once within a 1-year period, for an overall readmission rate of 14.5%. Amongst those children who were readmitted, there was a median of 1 readmission, with an overall range of 1 to 8 readmissions. Similar to the index cohort, 57% of readmitted children were male, and median probability of mortality was 1.2%. Fewer children were readmitted with respiratory compromise: only 41% as compared to 48% of the index cohort. It is notable that in the readmission cohort, 66% of children had CCCs, as compared to only 47% in the index cohort (Table 2).

Table 2.

Bivariate Analyses Describing Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Index Admission Associated with Readmission (n=1145)

| Patient Characteristics on Index Admission (n,%) |

No Readmission (n=979) |

Readmission (n=166) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 424 (85.5%) | 72 (14.5%) | >0.99 |

| Male | 555 (85.5%) | 94 (14.5%) | |

| Age | 0.017 | ||

| <6 months | 153 (79.7%) | 39 (20.3%) | |

| 6 months or older | 826 (86.7%) | 127 (13.3%) | |

| Admitting Diagnosis | 0.199 | ||

| Cardiac disease | 72 (79.1%) | 19 (20.9%) | |

| Hematologic/Oncologic disorder | 42 (79.2%) | 11 (20.8%) | |

| Infectious/inflammatory | 103 (87.3%) | 15 (12.7%) | |

| Neurologic disorder | 229 (83.9%) | 44 (16.1%) | |

| Renal/Metabolic disorder | 66 (88.0%) | 9 (12.0%) | |

| Respiratory insufficiency/failure | 467 (87.3%) | 68 (12.7%) | |

| Complex Chronic Condition | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 545 (90.5%) | 57 (9.47%) | |

| 1 | 338 (82.6%) | 71 (17.4%) | |

| 2 or more | 96 (71.6%) | 38 (28.4%) | |

| Mechanical Ventilation | <0.001 | ||

| No | 631 (88.6%) | 81 (11.4%) | |

| Yes | 348 (80.4%) | 85 (19.6%) | |

| Probability of Mortality (%, IQR) | 1% [1-3%] | 2% [1-4%] | <0.001 |

| PICU LOS (days, median, IQR) | 3 [2-4] | 4 [2-6] | <0.001 |

| Ever Delirious | <0.001 | ||

| No | 859 (87.4%) | 124 (12.6%) | |

| Yes | 120 (74.1%) | 42 (25.9%) | |

| Delirium Subtype | <0.001 | ||

| Hypoactive | 73 (61%) | 19 (45%) | |

| Mixed | 42 (35%) | 21 (50%) | |

| Hyperactive | 5 (4%) | 2 (5%) |

Delirium in Readmitted Patients

Amongst the readmitted cohort, there was a higher prevalence of delirium: delirium was diagnosed in 25%, as compared to 14% of the index admissions. The duration of delirium was longer as well, with a median of two days with delirium in the index cohort and three days in the readmission cohort. The most common type of delirium in the index cohort was hypoactive (57%); in subjects who were readmitted, mixed-type (50%) delirium was most common (Tables 1 and 2).

Predictors of PICU Readmission

In bivariate analyses (Table 2), the following characteristics on index admission were significantly associated with readmission: having a complex chronic condition, age<6 months, severity of illness on index admission, PICU length of stay, need for mechanical ventilation, and a diagnosis of delirium (26% of children with delirium required readmission, as compared to 13% of children without delirium, p<0.001).

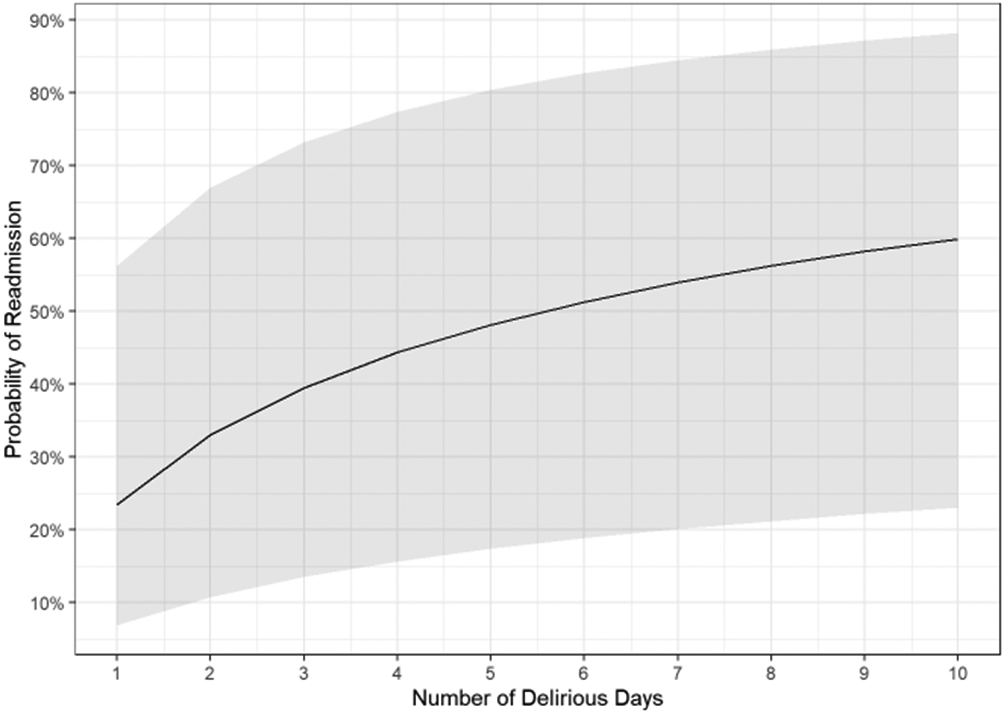

In the multivariable analysis (Table 3), the following factors were independently associated with readmission, after controlling for covariates: age less than six months on index admission (aOR 0.62 for >six months of age, CI 0.40–0.99), complex chronic conditions (with a stepwise increase in readmission rates for 1 vs. 2 or more CCC), and severe illness on index admission (as quantified by the PIM3 score). In addition, children with a length of stay greater than 3 days on index admission were more likely to be readmitted. Children with only 1-2 days of delirium were no more likely to be readmitted than children without delirium, after controlling for confounders. However, children with more than two days of delirium on index admission were more than twice as likely to be readmitted (aOR 2.21 [1.11-4.35], p=0.023), even after controlling for all other predictors of readmission (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Describing Odds of Readmission

| Patient Characteristic | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Age, 6 months or older (vs. <6 months) | 0.63 (0.4-0.9) | 0.04 |

| Complex Chronic Condition: | ||

| 1 (vs. none) | 2.22 (1.48-3.35) | <0.001 |

| 2 or more (vs. none) | 3.38 (2.04-5.58) | <0.001 |

| Severity of Illness | ||

| Moderate (vs mild) | 1.26 (0.78-2.04) | 0.34 |

| Severe (vs mild) | 2.06 (1.32-3.25) | 0.002 |

| Ever mechanically ventilated (vs. never) | 1.15 (0.79-1.68) | 0.45 |

| PICU LOS >3 days (vs. <=3 days) | 1.55 (1.05-2.26) | 0.02 |

| Number of delirious days: | ||

| 1 or 2 (vs. none) | 1.06 (0.59-1.83) | 0.84 |

| >2 (vs. none) | 2.21 (1.11-4.35) | 0.02 |

Figure 1.

Multivariable model, including only those children delirious on index admission (n=162), demonstrates a relationship between duration of delirium and odds of readmission.

DISCUSSION

While the PICU readmission literature is sparse, several factors have been strongly associated with greater readmission risk, including younger age, greater severity of illness, longer PICU length of stay, and (most significantly), presence of complex chronic conditions (20,28-29). Our study results are consistent with these findings, demonstrating that younger age (less than six months), severe illness on index admission, number of complex chronic conditions, and longer PICU length of stay all predicted future readmissions. In addition, we have shown that more than two days of delirium was independently associated with a more than doubling of readmission risk.

The ‘dose-response’ relationship between pediatric delirium and readmission risk is a novel and important finding. As previously determined in the pediatric delirium literature, delirium duration is directly related to clinical outcomes and can be thought of as a surrogate for delirium severity. Those children who experience a longer duration of delirium often require longer stays in the hospital, greater time on mechanical ventilation, and more hospital resources than patients with delirium of shorter duration (25). Studies have shown incremental increases in hospital costs for every day spent delirious (7). In this study, short delirium duration – although highly significant in bivariate analysis – was not independently associated with risk for readmission. However, delirium of greater than two days was associated with doubling of readmission risk, even after carefully including all the well-accepted factors that generally predict PICU readmissions. This may represent a threshold for longer-lasting effects.

It is of paramount importance to decrease the rate of PICU readmissions. Repeated admissions not only dramatically increase healthcare costs and strain the US healthcare system, but also negatively affect the long-term psychological, emotional and physical well-being of children and their families (12-16,20). A burgeoning pediatric literature has shown that pediatric delirium is preventable. As an example, Simone et al. demonstrated a significant decrease in delirium incidence with implementation of a quality improvement project including delirium education and screening, minimizing sedation, and early mobilization (30).

In this observational study, we do not presume causality. It is possible that the strong and independent association between delirium duration and odds of readmission reflects an epiphenomenon: rather than the delirium itself increasing the risk for readmission, it may be that delirium is merely a sensitive marker for the most vulnerable children who are already at considerable risk for poor outcomes. If so, then delirium would be an important way for providers to identify a high-risk population upon discharge. Future studies may explore feasibility and efficacy of PICU follow-up clinics for children who experienced delirium during their PICU stay. This could provide an opportunity to identify problems and intervene early, avoiding preventable readmissions. The ‘excess’ readmission risk associated with pediatric delirium may thus be modifiable.

This study has strengths and important limitations. To our knowledge, it is the first study to incorporate delirium into risk assessment for PICU readmission, and generates novel and important findings. The large cohort and remarkably complete dataset allowed for careful control of many variables. However, it is a single-center study and results may not be widely generalizable. In addition, although we included all variables that have been described as predictors of readmission in the PICU literature, it is likely that there are unknown confounders that were missed. Also, we were not powered to analyze either the subtypes of delirium (hypo-, hyperactive, and mixed) or the types of complex chronic conditions (for example: neurologic vs. oncologic vs. other) and their relationship to readmission in our cohort; these should be included in future larger studies (28). Finally, we could only capture prior admissions and readmissions to our single center, and could not account for admissions elsewhere, or post-discharge mortality at home. Finally, this observational study can only show associations, and cannot establish causal relationships.

In sum, delirium duration may be an independent risk factor for readmission in critically ill children. Future research is needed to determine if decreasing prevalence of delirium during hospitalization can decrease the need for PICU readmission.

Research In Context:

Delirium in critically ill children is associated with increased in-hospital morbidity and mortality. However, little is known regarding the effects of pediatric delirium on patient outcomes after discharge.

Reducing PICU readmission rates is an important quality metric. Therefore, identifying potentially modifiable factors that are associated with PICU readmissions is critically important.

This study describes the association between delirium and PICU readmission.

At the Bedside:

Delirium is independently associated with increased PICU readmission risk.

Further research is needed to investigate whether preventing and treating delirium can decrease PICU readmission rates.

Delirium provides a means of identifying children at high-risk for readmission. Targeted follow-up may identify problems, allow for early intervention, and avoid preventable readmissions.

Financial support:

Funding provide by the Department of Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medical College, and the Clinical Translational Science Center, grant number UL1-TR000457-06.

Footnotes

Copyright Form Disclosure: Dr. Traube’s institution received funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Cancer Institute; she received support for article research from the National Institutes of Health. The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Tara C. Pilato, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY.

Elizabeth A. Mauer, Department of Population Health Sciences, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY.

Linda M. Gerber, Department of Population Health Sciences, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY.

Chani Traube, Department of Pediatrics, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA, American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263–306. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182783b72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ely EW, Shintani A, Truman B, et al. Delirium as a predictor of mortality in mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit. JAMA. 2004;291(14):1753–1762. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel AK, Bell MJ, Traube C. Delirium in Pediatric Critical Care. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2017;64(5):1117–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2017.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girard TD, Jackson JC, Pandharipande PP, et al. Delirium as a predictor of long-term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1513–1520. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47be1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rengel KF, Hayhurst CJ, Pandharipande PP, Hughes CG. Long-term Cognitive and Functional Impairments After Critical Illness. Anesth Analg. 2019;128(4):772–780. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Traube C, Mauer EA, Gerber LM, et al. Cost Associated With Pediatric Delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(12):e1175–e1179. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silver G, Traube C, Gerber LM, et al. Pediatric delirium and associated risk factors: a single-center prospective observational study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16(4):303–309. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smeets IA, Tan EY, Vossen HG, et al. Prolonged stay at the paediatric intensive care unit associated with paediatric delirium. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;19(4):389–393. doi: 10.1007/s00787-009-0063-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kudchadkar SR, Yaster M, Punjabi NM. Sedation, sleep promotion, and delirium screening practices in the care of mechanically ventilated children: a wake-up call for the pediatric critical care community. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(7):1592–1600. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Traube C, Silver G, Gerber LM, et al. Delirium and Mortality in Critically Ill Children: Epidemiology and Outcomes of Pediatric Delirium. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(5):891–898. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards JD, Lucas AR, Stone PW, et al. Frequency, risk factors, and outcomes of early unplanned readmissions to PICUs. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(12):2773–2783. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31829eb970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gay JC, Agrawal R, Auger KA, et al. Rates and impact of potentially preventable readmissions at children's hospitals. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):613–9.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rennick JE, Rashotte J. Psychological outcomes in children following pediatric intensive care unit hospitalization: a systematic review of the research. J Child Health Care. 2009;13(2):128–149. doi: 10.1177/1367493509102472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manning JC, Hemingway P, Redsell SA. Long-term psychosocial impact reported by childhood critical illness survivors: a systematic review. Nurs Crit Care. 2014;19(3):145–156. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Payne NR, Flood A. Preventing pediatric readmissions: which ones and how?. J Pediatr. 2015;166(3):519–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Straney L, Clements A, Parslow RC, et al. Paediatric index of mortality 3: an updated model for predicting mortality in pediatric intensive care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(7):673–681. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31829760cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 Pt 2):205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edwards JD, Houtrow AJ, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Chronic conditions among children admitted to U.S. pediatric intensive care units: their prevalence and impact on risk for mortality and prolonged length of stay. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(7):2196–2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards JD, Lucas AR, Boscardin WJ, Dudley RA. Repeated Critical Illness and Unplanned Readmissions Within 1 Year to PICUs. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(8):1276–1284. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Traube C, Silver G, Kearney J, et al. Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium: a valid, rapid, observational tool for screening delirium in the PICU. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(3):656–663. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a66b76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris J, Ramelet AS, van Dijk M, et al. Clinical recommendations for pain, sedation, withdrawal and delirium assessment in critically ill infants and children: an ESPNIC position statement for healthcare professionals. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42(6):972–986. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4344-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fernández-Carrión F, González-Salas E, Silver G, Traube C. Translation and Cultural Adaptation of Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium to Spanish. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20(4):400–402. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barbosa MDSR, Duarte MDCMB, Bastos VCS, Andrade LB. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Cornell Assessment of Pediatric Delirium scale for the Portuguese language. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30(2):195–200. doi: 10.5935/0103-507X.20180033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyburg J, Dill ML, Traube C, et al. Patterns of Postoperative Delirium in Children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(2):128–133. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ely EW, Truman B, Shintani A, et al. Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: reliability and validity of the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). JAMA. 2003;289(22):2983–2991. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.22.2983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sessler CN, Gosnell MS, Grap MJ, et al. The Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale: validity and reliability in adult intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(10):1338–1344. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2107138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Czaja AS, Hosokawa PW, Henderson WG. Unscheduled readmissions to the PICU: epidemiology, risk factors, and variation among centers. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013;14(6):571–579. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182917a68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotsakis A, Stevens D, Frndova H, et al. Description of PICU Unplanned Readmission. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2016;17(6):558–562. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simone S, Edwards S, Lardieri A, et al. Implementation of an ICU Bundle: An Interprofessional Quality Improvement Project to Enhance Delirium Management and Monitor Delirium Prevalence in a Single PICU. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2017;18(6):531–540. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]