Abstract

Introduction:

Results from “ORAL Surveillance” safety trial have indicated an increased risk of malignancy with tofacitinib when compared with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFI). We further examined this safety concern in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients in the real-world setting.

Methods:

Using U.S. insurance claims data from Optum Clinformatics (2012–2020), IBM MarketScan (2012–2018), and Medicare (parts A, B, D, 2012–2017), we created two cohorts of RA patients initiating treatment with tofacitinib or TNFI. The first cohort, “Real-world evidence (RWE)” included patients from routine care. The second cohort, “RCT-duplicate cohort”, emulated the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the ORAL surveillance trial to assess comparability of our results with the trial. Cox proportional hazards models with propensity score fine-stratification weighting were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for risk of any malignancy (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer). Database-specific estimates were meta-analyzed using fixed effects models with inverse-variance weighting.

Results:

The RWE cohort included 83,295 patients of whom 10,504 (12.6%) initiated tofacitinib. The pooled weighted HR (95% CI) for the primary any malignancy outcome associated with tofacitinib compared with TNFI was 1.01 (0.83, 1.22) in the RWE cohort and 1.17 (0.85, 1.62) in the RCT-duplicate cohort (versus ORAL Surveillance trial, 1.48 [1.04, 2.09]).

Discussion:

We did not find evidence for an increased risk of malignancy with tofacitinib, in comparison with TNFI, in RA patients treated in the real-world setting. However, our results cannot rule out a possibility of an increase in risk that may accrue with a longer treatment duration.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that affects approximately 0.2% adult population globally (1). Tofacitinib is the first Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 for treatment of RA. Since then, the FDA has approved the use of tofacitinib for treatment of other autoimmune conditions including active psoriatic arthritis (2017), moderate to severe ulcerative colitis (2018), and most recently for active polyarticular course juvenile idiopathic arthritis (2020).

The utilization of tofacitinib has markedly increased for management of moderate to severe RA since 2012 (2–4). However, recent results from “ORAL Surveillance” post-marketing safety trial indicated that tofacitinib, in comparison with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFI), may be associated with increased risk of malignancies in patients with RA who were at least 50 years of age with cardiovascular risk factors (Hazard ratio [HR]: 1.48, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.04, 2.09) (5–8). As a result, the US FDA has issued a warning regarding risk of malignancies with tofacitinib (9). Given these results and increasing use of tofacitinib in treatment of patients with RA, the aim of this study was to conduct a large population-based observational study to further examine the risk of malignancies with tofacitinib in representative RA patients treated in a real-world clinical setting.

Patients and Methods

Data Sources and Study Design

We conducted an active-comparator, new-user cohort study (Supplemental Figure 1) using claims data from Optum Clinformatics (November 2012-June 2020), IBM MarketScan (November 2012- December 2018), and fee-for-service Medicare (parts A, B, and D, November 2012-December 2017) in the United States (10). Optum and MarketScan provide de-identified longitudinal patient-level health data from over 78 and 200 million commercially insured patients, respectively, across the United States. Medicare is a federal health insurance program which provides healthcare coverage for U.S. residents aged at least 65 years and some younger patients with disabilities. All these data sources capture information on patient demographics, health plan enrollment status, and patient-level longitudinal data on medical diagnoses in inpatient and outpatient settings, diagnostic tests, procedures, and pharmacy prescription dispensation records (including medication start and refill dates, strength, quantity, and days’ supply).

The protocol for this study received ethics approval (IRB #2011P002580, 207) from the Institutional Review Board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, Massachusetts). The full study protocol for this study was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04798287)(11). The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were followed (12). Informed consent requirement for patients was waived due to removal of all personal identifiers and protection of patient confidentiality for each of the three data sources. Signed data license agreements were obtained for all data sources.

Study population

We first identified patients initiating treatment on tofacitinib or a TNFI (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, and golimumab) in each of the three data sources. Cohort entry date was defined as the first record of pharmacy dispensation for tofacitinib or TNFI. Patients were required to have a minimum of 365 days of continuous enrollment in healthcare plan prior to and inclusive of the cohort entry date. To select patients with RA, we required at least two visits, 7–365 days apart, coded for RA in year prior to cohort entry date (Supplemental Figure 1). A previous study has shown a positive predictive value of 86% for this claims-based algorithm (13). Further, we restricted the study population to new users of tofacitinib and TNFI. Thus, tofacitinib users with a prescription of this drug in 365 days prior to cohort entry were excluded. We also excluded tofacitinib users with prescriptions of baricitinib or upadacitinib on or at any time prior to cohort entry date. Similarly, TNFI users with a prescription of index TNFI agent in 365 days prior to cohort entry date, TNFI users with previous use of any JAK inhibitor (i.e., tofacitinib, baricitinib, upadacitinib), and TNFI users with prescriptions for other agents from the TNFI class on cohort entry date were excluded. We also excluded patients with a concurrent prescription of tofacitinib and TNFI on cohort entry date. We additionally excluded patients with missing data on age or gender and patients admitted to a nursing facility or hospice admission at any point prior to cohort entry date. Finally, to identify incident cases of cancer, we excluded patients with a diagnosis of any malignancies (including non-melanoma skin cancer[NMSC]) prior to cohort entry date.

From this source population, we created two study cohorts: (1) “real-world evidence (RWE) cohort” which included all RA patients from routine care, and (2) “RCT-duplicate cohort” which emulated the ORAL surveillance trial by applying the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. The RCT-duplicate cohort was used to assess the comparability of our findings with the trial results (5, 6, 8).

The RWE cohort included all RA patients at least 18 years of age in Optum and MarketScan (≥ 65 in Medicare) at cohort entry date. In contrast, the RCT-duplicate cohort was restricted to patients 50 years (65 in Medicare) of age or older, with at least one methotrexate dispensation in six months prior to cohort entry date, and at least one cardiovascular risk factor (including history of smoking, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes mellitus, ischemic heart disease, or family history of ischemic heart disease) in the year prior to cohort entry date. We excluded patients hospitalized with infections in the 30-days prior to cohort entry date and pregnant patients from the RCT-duplicate cohort. The complete list of ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes used for exclusion criteria can be found in full protocol on clinicaltrials.gov (11).

Outcomes

In the primary as-treated analysis, we followed patients from the day after date of treatment initiation with tofacitinib or TNFI initiation for study outcomes until treatment discontinuation (60 days of no prescription refills for the index exposure after the days’ supply end for the most recent dispensation) or switch, insurance disenrollment, death, or end of the study period, whichever occurred first (Supplemental Figure 1). The primary outcome was defined as a composite endpoint of any new malignancies excluding non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) using a validated claims-based algorithm with two inpatient or outpatient ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis codes of the same type of malignancy occurring within 60 days (14, 15). This outcome definition demonstrated a high specificity (≥98%) for the majority of cancer outcomes. However, the sensitivity was somewhat lower for common solid tumors including lung cancer (76.2%), colorectal cancer (80.4%), breast cancer (78.9%) and lymphoma (79.8%). All carcinoma in situs were not included in the composite outcome definition. Secondary outcomes were individual types of malignancy including lung cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, lymphatic/hematopoietic tissue cancers, and NMSC. Last, we examined the association between tofacitinib and risk of herpes zoster as a positive control outcome, a known association established in previous studies (16, 17).

Covariate Assessment

We assessed 75 predefined suspected confounders or risk factors for malignancy in Optum and Medicare (74 in MarketScan) during the 365 days prior to and including cohort entry date (i.e baseline period). These included demographic variables of age, gender, and race (available in Optum and Medicare), and lifestyle-related variables including obesity and smoking which were assessed on cohort entry date (18, 19). We also assessed RA-related treatment history with conventional DMARDs including use of individual agents and total number of distinct agents during the baseline period. We assessed recent use (in 60 days prior to and including cohort entry date) of glucocorticoids. Prior use of glucocorticoids, cumulative prednisone equivalent dose of glucocorticoids, and number of distinct biological DMARD (including index drugs) were assessed during the baseline period (20, 21).

We assessed co-morbidities that have been shown to be associated with or share risk factors with malignancies including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease (atrial fibrillation, coronary artery disease, heart failure, stroke or transient ischemic attack, peripheral vascular disease), venous thromboembolism, chronic liver disease, chronic kidney disease (stage 3+), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, Combined Comorbidity Index, and claims-based frailty index (22–27). We assessed the use of the following medications: anticoagulants, antiplatelets, antidepressant drugs, antihypertensive drugs, anti-arrhythmic drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease maintenance drugs, insulin and non-insulin antidiabetic drugs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors, opioids, and hormonal agents (18, 25, 28–31). We also accounted for 25 markers of healthcare utilization to account for potential differences in use and access to healthcare system or potential differential surveillance during the baseline period. Finally, we assessed calendar year of cohort entry as a marker of temporal changes in management of patients with RA and diagnoses of malignancies during the study period.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized the baseline characteristics for patients initiating treatment on tofacitinib or TNFI using descriptive statistics. We provided Poisson distribution-based estimates of incidence rates, and incidence rate difference (comparing tofacitinib and TNFI users) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each study outcome.

We used propensity-score (PS) fine stratification to account for 75 measured potential confounders (74 in MarketScan) independently in each dataset (32). In the setting of low exposure prevalence, which is common when studying newer treatments versus more established treatments, this method has been shown to increase precision, without compromising bias adjustment, in comparison with PS-matching methods (32). To generate PS fine stratification weights, multivariable logistic regression was first used to calculate PS as the predicted probability of initiating treatment with tofacitinib conditional on baseline covariates in each of the data sources (33). We restricted the study population to the overlapping region of PS score distribution to include tofacitinib and TNFI users along the entire distribution of the PS and exclude patients with extreme PS (33). Subsequently, we created 50 strata, based on the distribution of PS in patients initiating treatment on tofacitinib (32). Tofacitinib users received a weight of one. To calculate the weights for TNFI users, first the proportion of tofacitinib users in each PS stratum was calculated by dividing the number of tofacitinib users in a given stratum by the total number of tofacitinib users in the study population. Similarly, the proportion of TNFI users was calculated by dividing the number of TNFI users in a given PS stratum by total number of TNFI users. The ratio of these proportions (i.e., the proportion of tofacitinib users in given strata divided by the proportion of TNFI users in given strata) defined the weight for TNFI users. This method estimates the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) (32).

To assess covariate balances between tofacitinib and TNFI users, we calculated standardized differences (%) before and after PS fine stratification weighting. Standardized differences of less than 10% indicated sufficient covariate balance when comparing tofacitinib and TNFI users (33–35). We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate crude and weighted hazard ratios and corresponding 95% CI with PS fine stratification weights used to account for potential confounders. Robust variance estimation was used to generate 95% CI in the weighted population. We also examined the cumulative incidence of composite malignancies and 95% CI for each treatment group in the PS-weighted populations. All analyses were conducted independently in each dataset. We used a fixed effects model with inverse variance weighting to meta-analyze database-specific effect estimates (36).

Aetion Evidence Platform was used for cohort construction (37). All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Secondary and Sensitivity analyses

We conducted prespecified subgroup analyses in the RWE cohort by stratifying on age (≤65 and >65) and sex. Further, we examined the risk of malignancies by stratification on the number of unique biologic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARD) used in year prior to cohort entry date (0 vs ≥1). As a sensitivity analysis, we conducted 1:1 PS matching using nearest neighbor greedy matching algorithm without replacement with a caliper of 0.025 on the natural scale of the PS (33, 38). We also restricted the TNFI comparator group to adalimumab and etanercept users in both RWE and RCT-duplicate cohorts similar to the comparator group in the ORAL Surveillance trial (5–8).

We further assessed different follow-up schemes in RWE and RCT-duplicate cohorts (Supplemental Figure 2). First, we implemented an intention-to-treat (ITT) exposure definition whereby patients were followed until end of study period after treatment initiation to minimize the impact of informative censoring based on treatment discontinuation on the results. Second, we implemented ITT exposure definition but truncated follow-up until maximum of 365 days after treatment initiation with tofacitinib or TNFI. Third, we conducted sensitivity analysis by lagging exposure by three months after treatment initiation to account for potential latency of treatment effect, exclude prevalent cases of cancer, and minimize surveillance bias. Finally, we extended the grace period to six months after treatment discontinuation to account for the potential carryover effect of the treatments on cancer outcomes. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis whereby we required at least two years of continuous enrollment prior to cohort entry date, excluded patients with dispensation for index drug at any point prior to cohort entry date, and assessed comorbidities over two-year baseline period prior to and including cohort entry date.

Results

RWE Cohort

The RWE cohort consisted of 83,295 patients: 25,410 patients identified in Optum, 29,511 patients in MarketScan, and 28,374 patients in Medicare (Consort diagrams: Supplemental Tables 1) of whom 3,304 (13.0%), 4,508 (15.3%), and 2,692 (9.5%) initiated treatment on tofacitinib respectively (Supplemental Table 2). The mean age in years comparing tofacitinib users and TNFI users was 55.9 vs 53.6 in Optum, 53.8 vs 51.6 in MarketScan, and 71.3 vs 71.4 in Medicare (Supplemental Table 2). The majority of patients were female (range 77–80%), white (range 66–83%) and had received treatment with conventional DMARDs (range 75–82%) and glucocorticoids (range 69–72%) prior to treatment initiation with tofacitinib or TNFI (Supplemental Table 2). The mean (std) number of bDMARDs prior to and including cohort entry date comparing tofacitinib with TNFI users was 1.6 (0.7) vs 1.3 (0.5) in Optum, 1.8 (0.8) vs 1.4 (0.6) in MarketScan, and 1.6 (0.7) vs 1.3 (0.5) in Medicare (Supplemental Table 2). There were no discernable differences across most comorbidities, prior prescriptions, and markers for healthcare utilization when comparing tofacitinib initiators with TNFI initiators (Supplemental Table 2). We obtained covariate balance after PS fine stratification weighting, with standardized differences of less than 5% for all covariates in all three datasets (Table 1 and Supplemental Table 3).

Table 1.

Select baseline characteristics of RWE rheumatoid arthritis patients initiating tofacitinib or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors after propensity score fine stratification weighting

| Optum | MarketScan | Medicare | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Tofacitinib (n=3,301) | TNFI (n=21,934) | SD (%) | Tofacitinib (n=4,499) | TNFI (n=24,960) | SD (%) | Tofacitinib (n=2,689) | TNFI (n=25,673) | SD (%) |

| Demographic variables | |||||||||

| Age; mean (std) | 55.8 (12.4) | 56.1 (13.1) | −2.3 | 53.8 (11.4) | 54.0 (11.7) | −1.8 | 71.3 (5.4) | 71.4 (5.3) | −1.3 |

| Female; n (%) | 2,690 (81.5) | 17,963 (81.9) | −1.0 | 3,699 (82.2) | 20,562 (82.4) | −0.4 | 2,300 (85.5) | 22,082 (86.0) | −1.4 |

| White; n (%) | 2,069 (62.7) | 13,683 (62.4) | 0.6 | - | - | - | 2,064 (76.8) | 19,537 (76.1) | 1.5 |

| Black; n (%) | 368 (11.1) | 2,473 (11.3) | −0.4 | - | - | - | 344 (12.8) | 3,397 (13.2) | −1.3 |

| Asian; n (%) | 98 (3.0) | 613 (2.8) | 1.1 | - | - | - | 73 (2.7) | 710 (2.8) | −0.3 |

| Hispanic; n (%) | 426 (12.9) | 2,903 (13.2) | −1.0 | - | - | - | 100 (3.7) | 980 (3.8) | −0.5 |

| RA related variables | |||||||||

| Number of unique bDMARDs; mean (std)* | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | 2.1 | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.5 | 1.6 (0.7) | 1.6 (0.7) | 2.9 |

| Non-biologic DMARDs | |||||||||

| Number of distinct csDMARDs; mean (std) | 1.0 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.8) | 0.1 | 1.0 (0.8) | 1.0 (0.8) | 2.0 | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.8) | 0.7 |

| Any csDMARD use; n (%) | 2,402 (72.8) | 15,971 (72.8) | −0.1 | 3,374 (75.0) | 18,576 (74.4) | 1.3 | 2,075 (77.2) | 19,725 (76.8) | 0.8 |

| Methotrexate; n (%) | 1,523 (46.1) | 10,037 (45.8) | 0.8 | 2,303 (51.2) | 12,618 (50.6) | 1.3 | 1,403 (52.2) | 13,214 (51.5) | 1.4 |

| Hydroxychloroquine; n (%) | 829 (25.1) | 5,528 (25.2) | −0.2 | 1,053 (23.4) | 5,711 (22.9) | 1.2 | 679 (25.3) | 6,425 (25.0) | 0.5 |

| Leflunomide; n (%) | 703 (21.3) | 4,702 (21.4) | −0.3 | 893 (19.8) | 4,917 (19.7) | 0.4 | 605 (22.5) | 5,845 (22.8) | −0.6 |

| Sulfasalazine; n (%) | 343 (10.4) | 2,287 (10.4) | −0.1 | 424 (9.4) | 2,287 (9.2) | 0.9 | 314 (11.7) | 3,025 (11.8) | −0.3 |

| Prior use of oral glucocorticoids (365 days); n (%) | 2,432 (73.7) | 16,177 (73.8) | −0.2 | 3,284 (73.0) | 18,275 (73.2) | −0.5 | 2,018 (75.0) | 19,258 (75.0) | 0.1 |

| Recent use of oral glucocorticoids (60 days); n (%) | 1,633 (49.5) | 10,825 (49.4) | 0.2 | 2,192 (48.7) | 12,188 (48.8) | −0.2 | 1,505 (56.0) | 14,329 (55.8) | 0.3 |

| Cumulative dose of oral steroids in mg; mean (std) | 901.4 (1277.6) | 911.5 (6555.1) | −0.2 | 1,754.5 (21873.2) | 1,859.6 (20903.4) | −0.5 | 1023.3 (1202.8) | 1,015.8 (1262.7) | 0.6 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||||

| Obesity; n (%) | 767 (23.2) | 5,139 (23.4) | −0.5 | 691 (15.4) | 3,844 (15.4) | −0.1 | 430 (16.0) | 4,118 (16.0) | −0.1 |

| Smoking; n (%) | 654 (19.8) | 4,292 (19.6) | 0.6 | 382 (8.5) | 2,146 (8.6) | −0.4 | 665 (24.7) | 6,377 (24.8) | −0.2 |

| Atrial fibrillation; n (%) | 116 (3.5) | 783 (3.6) | −0.3 | 94 (2.1) | 533 (2.1) | −0.3 | 246 (9.1) | 2,324 (9.1) | 0.3 |

| Coronary artery disease; n (%) | 296 (9.0) | 1,986 (9.1) | −0.3 | 326 (7.2) | 1899 (7.6) | −1.4 | 593 (22.1) | 5,641 (22.0) | 0.2 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus; n (%) | 702 (21.3) | 4,672 (21.3) | −0.1 | 683 (15.2) | 3,835 (15.4) | −0.5 | 821 (30.5) | 7,801 (30.4) | 0.3 |

| Heart failure; n (%) | 154 (4.7) | 1,073 (4.9) | −1.1 | 131 (2.9) | 733 (2.9) | −0.2 | 292 (10.9) | 2,791 (10.9) | 0.0 |

| Hypertension; n (%) | 1,671 (50.6) | 11,226 (51.2) | −1.1 | 1,928 (42.9) | 10,842 (43.4) | −1.2 | 2,207 (82.1) | 21,048 (82.0) | 0.2 |

| Hyperlipidemia; n (%) | 1,371 (41.5) | 9,201 (42.0) | −0.8 | 1,643 (36.5) | 9,215 (36.9) | −0.8 | 1,780 (66.2) | 16,896 (65.8) | 0.8 |

| Stroke or transient ischemic attack; n (%) | 81 (2.5) | 554 (2.5) | −0.5 | 81 (1.8) | 473 (1.9) | −0.7 | 88 (3.3) | 830 (3.2) | 0.2 |

| Peripheral vascular disease; n (%) | 137 (4.2) | 936 (4.3) | −0.6 | 106 (2.4) | 611 (2.4) | −0.6 | 268 (10.0) | 2,542 (9.9) | 0.2 |

| Venous thromboembolism; n (%) | 76 (2.3) | 518 (2.4) | −0.4 | 99 (2.2) | 559 (2.2) | −0.3 | 72 (2.7) | 694 (2.7) | −0.2 |

| Chronic liver disease; n (%) | 238 (7.2) | 1,582 (7.2) | 0.0 | 246 (5.5) | 1,341 (5.4) | 0.4 | 209 (7.8) | 1,987 (7.7) | 0.1 |

| Chronic kidney disease (Stage 3+); n (%) | 164 (5.0) | 1,090 (5.0) | 0.0 | 135 (3.0) | 753 (3.0) | −0.1 | 287 (10.7) | 2,776 (10.8) | −0.4 |

| COPD; n (%) | 490 (14.8) | 3,302 (15.1) | −0.6 | 501 (11.1) | 2,804 (11.2) | −0.3 | 693 (25.8) | 6,674 (26.0) | −0.5 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease; n (%) | 58 (1.8) | 388 (1.8) | −0.1 | 48 (1.1) | 258 (1.0) | 0.3 | 34 (1.3) | 324 (1.3) | 0.0 |

| Psoriasis; n (%) | 146 (4.4) | 960 (4.4) | 0.2 | 140 (3.1) | 749 (3.0) | 0.7 | 81 (3.0) | 728 (2.8) | 1.0 |

| Combined Comorbidity Index; mean (std) | 1.0 (1.8) | 1.0 (1.8) | −0.1 | 0.6 (1.4) | 0.6 (1.4) | −0.8 | 1.6 (2.2) | 1.6 (2.3) | −0.4 |

| Frailty index; mean (std) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.0) | −0.4 | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.0) | −1.6 | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.0) | 0.3 |

-Abbreviations: COPD-Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, csDMARDs-conventional synthetic disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, DMARD- disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, SD- standardized difference, std-standard deviation, TNFI- tumor necrosis factor inhibitors

-Full Tables describing all patient characteristics before and after PS-weighting are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Includes index drug

Primary Outcome- Risk of Any Malignancy

The mean (standard deviation) follow-up time in months in the as-treated analysis when comparing tofacitinib and TNFI users was 10.3 (11.2) and 11.3 (12.2) in Optum, 10.6 (11.0) and 11.4 (11.5) in MarketScan, and 10.3 (10.6) and 10.2 (10.4) in Medicare. Nevertheless, 9,237 (11.1%) patients had a follow-up time of at least two years. Overall, 13,893 (54.7%) patients in Optum, 15,445 (52.3%) in MarketScan, and 19,124 (67.4%) patients in Medicare discontinued treatment. The crude incidence rate (95% CI) per 100-person years when comparing tofacitinib users with TNFI users was 1.68 (1.24, 2.23) and 1.36 (1.21, 1.53) in Optum, 0.60 (0.39, 0.90) and 0.86 (0.74, 0.98) in MarketScan, and 2.70 (2.07, 3.46) and 2.49 (2.29, 2.71) in Medicare (Supplemental Table 4). The crude incidence rate difference (95% CI) per 100 person-years comparing tofacitinib users and TNFI users was 0.32 (−0.18, 0.83) in Optum, −0.25 (−0.52, 0.01) in MarketScan, and 0.21 (−0.50, 0.91) in Medicare (Supplemental Table 4). Overall, the pooled weighted HR (95% CI) for composite malignancy outcome comparing tofacitinib with TNFI was 1.01 (0.83, 1.22) corresponding to a weighted incidence rate difference (95% CI) per 100-person years of −0.16 (−0.40, 0.09) (Figure 1, Supplemental Table 4). The 95% CI for cumulative incidence of malignancies from time since treatment initiation were overlapping when comparing tofacitinib with TNFI users in each of the three data source (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of propensity score fine stratification weighted hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for composite malignancy outcome when comparing tofacitinib with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in RWE cohort (top panel) and RCT-duplicate cohort (bottom panel)

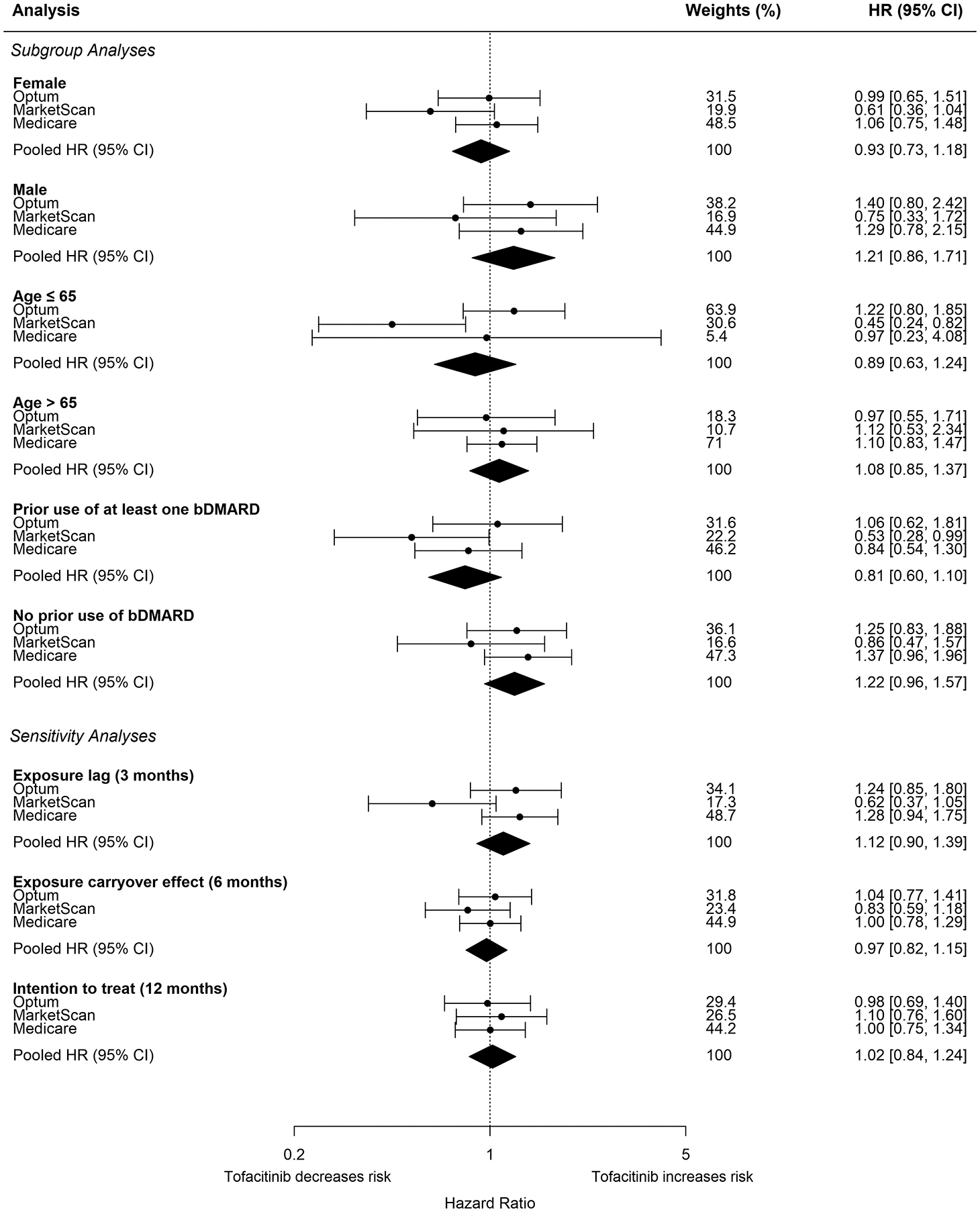

In subgroup analysis, the pooled weighted HR (95% CI) was 0.93 (0.73, 1.18) among females, 1.21 (0.86, 1.71) among males, 0.89 (0.63, 1.24) among those ≤65 years, and 1.08 (0.85, 1.37) among those >65 years. Among tofacitinib users, 1,650 (49.9%) patients in Optum, 2,797 (62.0%) in MarketScan, and 1,298 (48.2%) in Medicare had a history of use of bDMARDs prior to cohort entry date (Supplemental Table 4). Among TNFI users, 5,165 (23.4%) in Optum, 7,775 (31.1%) in MarketScan, and 7,624 (29.7%) in Medicare had a history of use of bDMARDs (Supplemental Table 4). The pooled weighted HR (95% CI) was 0.81 (0.60, 1.10) among those with history of treatment with bDMARDs, and 1.22 (0.96, 1.57) among patients with no history of treatment with bDMARDs (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 4).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of propensity score fine stratification weighted hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for composite malignancy outcome for subgroup and sensitivity analyses in RWE study cohort

The pooled weighted HR (95% CI) was 1.12 (0.90, 1.39) when implementing a three-month exposure lag, 0.97 (0.82, 1.15) with a six-month carryover effect after treatment discontinuation, and 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) when using ITT exposure definition (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 4). The pooled weighted HR (95% CI) was 1.02 (0.84, 1.24) when using ITT exposure definition but truncating follow-up time at 365 days after treatment initiation (Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 4). Using the six-month carryover and ITT exposure definition led to a longer follow-up time. The mean (std) follow-up time in months comparing tofacitinib with TNFI was 13.7 (13.2) vs 16.1 (14.9) in Optum, 14.0 (12.8) vs 16.1 (14.1) in MarketScan, and 13.4 (11.6) vs 17.3 (13.7) in Medicare when using the six-month carryover exposure definition. The mean (std) follow-up time in months comparing tofacitinib with TNFI was 22.6 (20.2) vs 25.2 (12.8) in Optum, 22.1 (17.9) vs 23.1 (18.5) in MarketScan, and 23.3 (16.4) vs 26.0 (17.1) in Medicare when using ITT exposure definition.

The pooled HR (95% CI) was 0.95 (0.75, 1.21) for 1:1 PS matching. The pooled weighted HR was 0.93 (0.75, 1.16) when restricting the comparator to adalimumab and etanercept users and 0.94 (0.74, 1.19) among patients with at least two years of continuous enrollment prior to cohort entry date with minimum of two years of washout for index drug, and a two-year window for assessment of comorbidities (Supplemental Table 4).

Secondary Outcomes

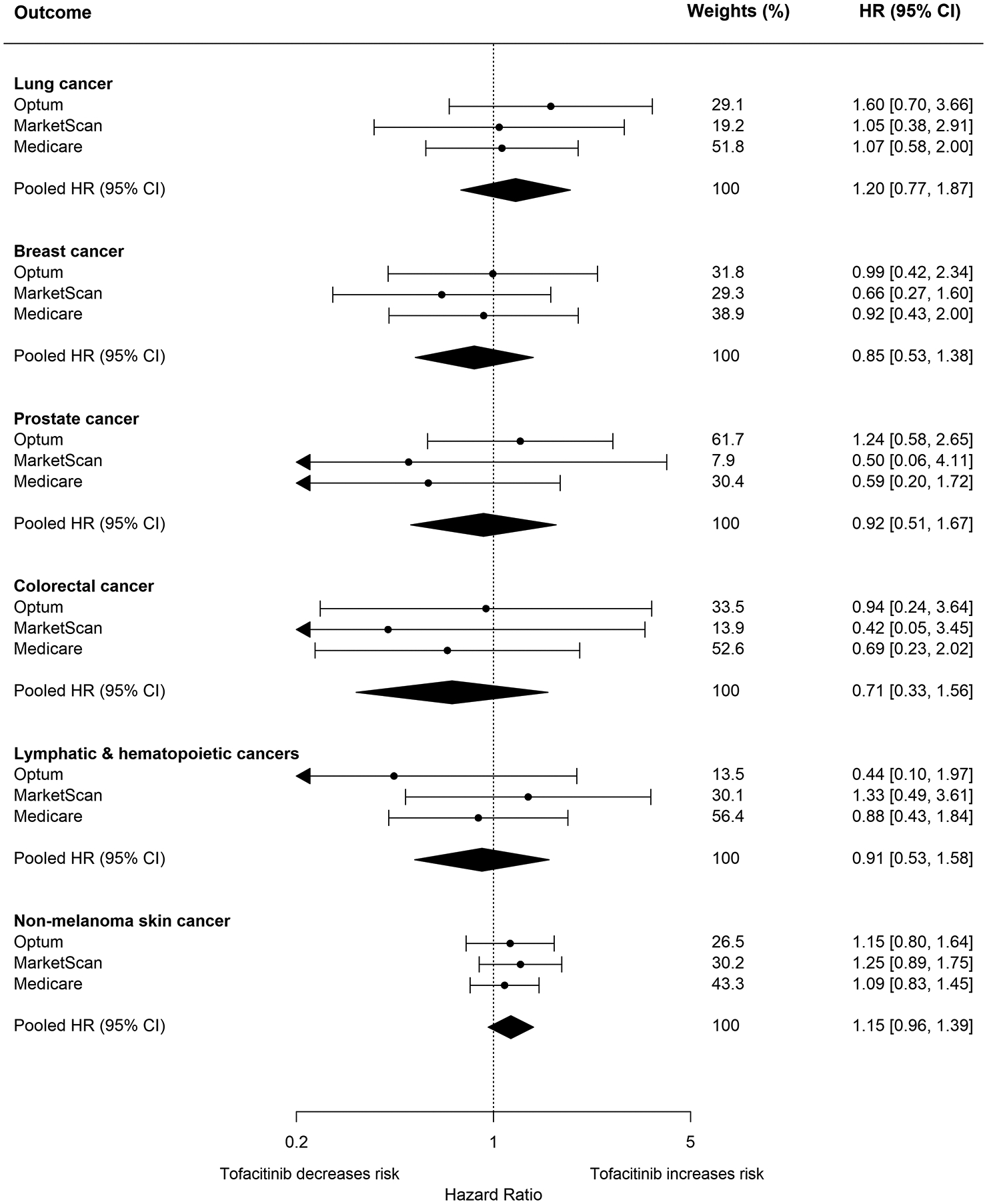

The pooled weighted HR (95% CI) when comparing tofacitinib users and TNFI users was 1.20 (0.77, 1.87) for lung cancer, 0.85 (0.53, 1.38) for breast cancer, 0.92 (0.51, 1.67) for prostate cancer, 0.71 (0.33, 1.56) for colorectal cancer, 0.91 (0.53, 1.58) for lymphatic and hematopoietic cancers, and 1.15 (0.96, 1.39) for NMSC in the RWE cohort (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 5). The pooled weighted HR (95%) CI was 2.02 (1.80, 2.27) for herpes zoster as the positive control outcome, consistent with previous reports (Supplemental Table 5) (16, 17).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of propensity score fine stratification weighted hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals for individual malignancy outcomes in RWE study cohort

RCT-duplicate Cohort

We identified 27,035 patients in the RCT-duplicate cohort: 5,899 in Optum, 6,588 in MarketScan, 14,548 patients in Medicare, respectively, who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Consort diagram: Supplemental Tables 1). Among these patients, 668 (11.3%), 938 (14.2%), 1,100 (7.6%) initiated treatment on tofacitinib (Supplemental Table 6). PS fine stratification achieved standardized differences close to zero for most covariates (Supplemental Table 7).

The crude incidence rate (95% CI) per 100-person years comparing tofacitinib with TNFI was 2.41 (1.35, 3.98) and 2.01 (1.63, 2.43) in Optum, 1.13 (0.54, 2.08) and 0.96 (0.72, 1.25) in MarketScan, and 2.76 (1.80, 4.04) and 2.31 (2.05, 2.61) in Medicare respectively (Supplemental Table 8). In the primary analysis, the pooled weighted HR (95% CI) was 1.17 (0.85, 1.62) when comparing tofacitinib users with TNFI users (vs ORAL Surveillance trial: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.04, 2.09) corresponding to a pooled weighted rate difference (95% CI) of 0.20 (−0.42, 0.82) per 100 person-years (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 8). In sensitivity analyses, the pooled weighted HR (95% CI) was 1.33 (0.94, 1.89) when lagging exposure by three months, 1.04 (0.78, 1.38) when using carryover of six months, 1.03 (0.83, 1.29) when using ITT exposure definition, and 1.07 (0.77, 1.50) when using ITT exposure definition but limiting follow-up to a maximum of 365 days after treatment initiation (Supplemental Table 8). We observed consistent results when restricting the comparator to adalimumab and etanercept users (pooled weighted HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 0.83, 1.67) (Supplemental Table 8). Overall, the results for cumulative incidence of malignancy outcomes from time since treatment initiation was inconclusive due to overlapping 95% CI when comparing tofacitinib with TNFI (Supplemental Figure 4).

Discussion

In this large multi-database cohort study, we did not observe an increased risk of malignancies when comparing tofacitinib with TNFI in RA patients treated in real-world settings (pooled weighted HR: 1.01, 95% CI: 0.83, 1.22). However, our results cannot not rule out a possibility of small increase in risk that may accrue with longer treatment episodes. Tofacitinib was associated with a numerically increased risk of malignancies in RCT-duplicate population which consisted of patients 50 years of age and older and with at least one cardiovascular risk-factor (pooled weighted HR: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.85, 1.62).

The ORAL Surveillance trial, a large, phase 3b/4 (n=4,362) post-marketing trial required by the FDA, assessed the safety of tofacitinib (5mg and 10mg) in comparison with adalimumab/etanercept in patients 50 years of age and older, with at least one cardiovascular risk factor, and with background treatment methotrexate treatment (5, 6, 8). Reports from this trial indicated that both 5mg and 10mg twice daily dose of tofacitinib were associated with increased risk of malignancies excluding NMSC (HR: 1.47, 95% CI: 1.00, 2.18 and HR: 1.48, 95% CI: 1.00, 2.19 respectively) (6–8). A higher risk of malignancies was observed in North America where the comparator was adalimumab (HR: 1.92, 95% CI: 1.10, 3.34) when compared with the rest of the world where the comparator was etanercept (HR: 1.25, 95% CI: 0.79, 1.97)(8). There were also imbalances in risk of lung cancer (HR: 2.17, 95% CI: 0.95, 4.93) and lymphoma (HR: 5.09, 95% CI: 0.65, 39.78) although with low precision (7, 8, 39). A significant difference between the RWE cohort in this study and the ORAL surveillance trial population is that the RWE cohort included all RA patients treated in routine care. Our results suggest potential heterogeneity of treatment effect. Among all RA patients treated in real world setting, we did not observe an increased risk of malignancies when comparing tofacitinib with TNFI. However, we observed a numerically increased risk of malignancies in the RCT-duplicate which included patients ≥ 50 years of age with cardiovascular risk factors (pooled weighted HR: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.85, 1.62). We also observed this numerically increased risk in RCT-duplicate cohort when restricting the comparator to adalimumab and etanercept (pooled weighted HR: 1.18, 95% CI: 0.83, 1.67). Nevertheless, there are other differences between our study and ORAL Surveillance trial including longer follow-up period in ORAL Surveillance trial (median of four years) and potential differential adherence to treatment (8).

Three other studies have also examined the association between tofacitinib and risk of malignancies (40–42). In a meta-analysis of six phase 2, six phase 3, and two long-term extension studies, the incidence rate of malignancies excluding non-NMSC among patients treated with tofacitinib was reported to be 0.85 (95% CI: 0.70, 1.02) events per 100 person-years, an incidence rate consistent with the expected range of patients with moderate-to-severe RA, although lower than the pooled crude incidence rate (per 100 person-years) observed across the three data sources in this study (1.74, 95 CI: 1.47, 2.06) (40). Similarly, a study conducted using CORRONA RA registry which includes more than 50,605 RA patients across private and academic practices in the United States, did not find an association between tofacitinib and malignancies excluding NMSC (Adjusted HR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.68, 1.61) or NMSC (Adjusted HR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.69, 1.50) (41). Last, a recent observational study which included 69,308 RA patients identified using Swedish Rheumatology Quality Register, reported that TNFI and other biologic/targeted synthetic DMARDs were not associated with increased risk of non-cutaneous malignancies when compared with no use of these drugs (42). However, this study did not assess risk of JAK inhibitors due to low number of events (<5). Multiple factors may account for differences in the results between these studies including the definition of study population, exposure and outcome definition, and follow-up time.

The potential mechanistic effects of tofacitinib on the risk of malignancies is complex. Tofacitinib is an inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK3 which are enzymes involved in activation of JAK-STAT signaling pathway. The effect of the JAK-STAT pathway on tumor initiation and progression is complex and multifaceted particularly given the possible indirect effects through crosstalk with other intracellular signaling pathways (43, 44). While some members of the STAT family (such as STAT3 and STAT5) may play a detrimental role in tumor initiation and progression, others (such as STAT1 and STAT2) may have a protective effect through mediating long-term antitumor immune response (43, 44). Further mechanistic studies are required to understand the potential direct effect of tofacitinib and role of JAK-STAT pathway in tumor initiation and progression.

There are several strengths of this study. First, we conducted analyses across three U.S. insurance claims databases (both commercial and public health plans) encompassing RA patients treated in a real-world setting, and thus the results are generalizable to setting of routine clinical care. Second, we calibrated our results with ORAL surveillance trial using the RCT-duplicate cohort to ensure validity of our study results and comparability with the trial findings. Third, we used an active-comparator, new-user design to control for confounding by indication and prevent immortal-time bias (10). Fourth, we observed consistent results in sensitivity analyses accounting for potential latency and carryover effect of treatment after discontinuation. Last, we registered the protocol for this study prior to conducting the analyses (11).

This study has some limitations. First, the follow-up time was relatively short (mean follow-up <1 year) due to the imposed as-treated definition where patients were censored at treatment discontinuation or switch. Nevertheless, 9,237 patients (11.1% of the study population) had a follow-up time of at least two years, a sample size greater than the ORAL Surveillance trial (n=4,362). Second, we did not assess the risk of malignancies for other JAK inhibitors including baricitinib and upadacitinib. Additional studies will be needed to examine the class effect of JAK inhibitors. Third, we did not have an adequate sample size to examine the risk of some individual malignancies such as leukemia and lymphoma. In addition, some subgroups indicated treatment heterogeneity, although no conclusions can be made due to low precision for the estimates. Fourth, outcome misclassification is possible, although we used a validated claims-based algorithm with a high specificity (≥98%) for most cancer types (15). Fifth, we also relied on diagnosis and procedure codes to select the study cohort. While we assessed obesity and smoking status, it is likely that the sensitivity of our claims-definitions is low (45, 46). Last, residual confounding due to some unmeasured RA-related variables is possible, although a recent study using CORRONA RA registry demonstrated that RA patients in United States initiating treatment with tofacitinib are similar to bDMARD users in regard to RA-related factors such as disease activity index (41).

In conclusion, in this large, population-based real-world cohort of 83,295 RA patients, tofacitinib was not associated with an increased risk of malignancies in comparison with TNFI. However, tofacitinib was associated with a numerically increased risk of malignancies in older patients with cardiovascular risk factors, similar to the ORAL Surveillance trial participants. Future studies with large sample size and long-term follow-up are required to confirm these findings.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This study was funded by internal sources of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women’s Hospital & Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. The funding source did not play any role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or writing of the manuscript. SCK is supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant - K24AR078959. FK is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé (FRQS).

Conflict of interest/Financial disclosures:

SCK has received research grants to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Roche/Genentech, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and AbbVie for unrelated studies. RJD has received research grants to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Bayer, Novartis, and Vertex for unrelated projects. All other authors have no conflict of interests to disclose.

References

- 1.Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Hoy D, Smith E, Bettampadi D, Mansournia MA, et al. Global, regional and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis 1990–2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(11):1463–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai RJ. Safety of TofAcitinib in Routine Care Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAR-RA)- Cardiovascular Endpoints. 2021. [cited; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04772248

- 3.Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, St Clair EW, Arayssi T, Carandang K, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73(7):1108–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park SH, Jeon HL, Kim SC, Hillen J, Gadzhanova S, Shin JY, et al. Utilization of targeted disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) for managing rheumatoid arthritis in the last decade: A two-country comparison. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfizer Inc. Safety Study Of Tofacitinib Versus Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Inhibitor In Subjects With Rheumatoid Arthritis. 2014. [cited; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02092467

- 6.Pfizer Inc. Pfizer Shares Co-Primary Endpoint Results from Post-Marketing Required Safety Study of XELJANZ® (tofacitinib) in Subjects with Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). 2021. [cited February 1, 2021]; Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-shares-co-primary-endpoint-results-post-marketing

- 7.Curtis J, Yamaoka K, Chen Y, Gunay L, Sugiyama N, Cornnell C, et al. Malignancies in Patients Aged ≥ 50 Years with RA and ≥ 1 Additional Cardiovascular Risk Factor: Results from a Phase 3b/4 Randomized Safety Study of Tofacitinib vs TNF Inhibitors. ACR Convergence; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ytterberg SR, Bhatt DL, Mikuls TR, Koch GG, Fleischmann R, Rivas JL, et al. Cardiovascular and Cancer Risk with Tofacitinib in Rheumatoid Arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(4):316–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Food and Drug Administration. Initial safety trial results find increased risk of serious heart-related problems and cancer with arthritis and ulcerative colitis medicine Xeljanz, Xeljanz XR (tofacitinib). 2021. [cited 2021 August 1, 2021]; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/initial-safety-trial-results-find-increased-risk-serious-heart-related-problems-and-cancer-arthritis

- 10.Lund JL, Richardson DB, Sturmer T. The active comparator, new user study design in pharmacoepidemiology: historical foundations and contemporary application. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2015;2(4):221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim SC. Safety of TofAcitinib in Routine Care Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis (STAR-RA)- Cancer Endpoints. [cited; Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04798287

- 12.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, Servi A, Polinski JM, Mogun H, Weinblatt ME, Katz JN, et al. Validation of rheumatoid arthritis diagnoses in health care utilization data. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13(1):R32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim SC, Pawar A, Desai RJ, Solomon DH, Gale S, Bao M, et al. Risk of malignancy associated with use of tocilizumab versus other biologics in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A multi-database cohort study. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49(2):222–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Setoguchi S, Solomon DH, Glynn RJ, Cook EF, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. Agreement of diagnosis and its date for hematologic malignancies and solid tumors between medicare claims and cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(5):561–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S, Wilkinson B, Bradley JD, Gruben D, et al. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(25):2377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pawar A, Desai RJ, Gautam N, Kim SC. Risk of admission to hospital for serious infection after initiating tofacitinib versus biologic DMARDs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multidatabase cohort study. Lancet Rheumat. 2020;2(2):e84–e98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cogliano VJ, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Lauby-Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. Preventable exposures associated with human cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(24):1827–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(1):7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Cock D, Hyrich K. Malignancy and rheumatoid arthritis: Epidemiology, risk factors and management. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018;32(6):869–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simon TA, Thompson A, Gandhi KK, Hochberg MC, Suissa S. Incidence of malignancy in adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gagne JJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Levin R, Schneeweiss S. A combined comorbidity score predicted mortality in elderly patients better than existing scores. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(7):749–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim DH, Patorno E, Pawar A, Lee H, Schneeweiss S, Glynn RJ. Measuring Frailty in Administrative Claims Data: Comparative Performance of Four Claims-Based Frailty Measures in the U.S. Medicare Data. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2020;75(6):1120–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lau ES, Paniagua SM, Liu E, Jovani M, Li SX, Takvorian K, et al. Cardiovascular Risk Factors are Associated with Future Cancer. JACC CardioOncol. 2021;3(1):48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tu H, Wen CP, Tsai SP, Chow WH, Wen C, Ye Y, et al. Cancer risk associated with chronic diseases and disease markers: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:k134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He MM, Lo CH, Wang K, Polychronidis G, Wang L, Zhong R, et al. Immune-Mediated Diseases Associated With Cancer Risks. JAMA Oncol. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tokajuk A, Krzyzanowska-Grycel E, Tokajuk A, Grycel S, Sadowska A, Car H. Antidiabetic drugs and risk of cancer. Pharmacol Rep. 2015;67(6):1240–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wong RSY. Role of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) in Cancer Prevention and Cancer Promotion. Adv Pharmacol Sci. 2019;2019:3418975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavergne F, Jay TM. Antidepressants Promote and Prevent Cancers. Cancer Invest. 2020;38(10):572–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wigmore T, Farquhar-Smith P. Opioids and cancer: friend or foe? Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2016;10(2):109–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desai RJ, Franklin JM. Alternative approaches for confounding adjustment in observational studies using weighting based on the propensity score: a primer for practitioners. BMJ. 2019;367:l5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46(3):399–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Austin PC. Using the Standardized Difference to Compare the Prevalence of a Binary Variable Between Two Groups in Observational Research. Communications in Statistics - Simulation and Computation. 2008;38(6):1228–34. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Franklin JM, Rassen JA, Ackermann D, Bartels DB, Schneeweiss S. Metrics for covariate balance in cohort studies of causal effects. Stat Med. 2014;33(10):1685–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1(2):97–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aetion Inc. Aetion Evidence Platform® (2020). Software for real-world data analysis. [cited; Available from: http://www.aetion.com

- 38.Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014;33(6):1057–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Health Products Regulatory Authority. Xeljanz (tofacitinib) - Important Safety Information from Pfizer Healthcare Ireland as approved by the HPRA (July 2021). 2021. [cited; Available from: https://www.hpra.ie/homepage/medicines/safety-notices/item?t=/xeljanz-(tofacitinib)---important-safety-information-from-pfizer-healthcare-ireland-as-approved-by-the-hpra-(july-2021)&id=99e90f26-9782-6eee-9b55-ff00008c97d0

- 40.Curtis JR, Lee EB, Kaplan IV, Kwok K, Geier J, Benda B, et al. Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor: analysis of malignancies across the rheumatoid arthritis clinical development programme. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(5):831–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kremer JM, Bingham CO 3rd, Cappelli LC, Greenberg JD, Madsen AM, Geier J, et al. Postapproval Comparative Safety Study of Tofacitinib and Biological Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs: 5-Year Results from a United States-Based Rheumatoid Arthritis Registry. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2021;3(3):173–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huss V, Bower H, Wadstrom H, Frisell T, Askling J. Short- and longer-term cancer risks with biologic and targeted synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drugs as used against rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brooks AJ, Putoczki T. JAK-STAT Signalling Pathway in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Owen KL, Brockwell NK, Parker BS. JAK-STAT Signaling: A Double-Edged Sword of Immune Regulation and Cancer Progression. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Desai RJ, Solomon DH, Shadick N, Iannaccone C, Kim SC. Identification of smoking using Medicare data--a validation study of claims-based algorithms. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25(4):472–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suissa K, Kim SC, Patorno E. Misclassification of Obesity in Claims Data. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021;12(11):e00423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.