Abstract

Objectives:

In Québec, Canada, we evaluated the risk of severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection associated with (1) the demographic and employment characteristics among healthcare workers (HCWs) and (2) the workplace and household exposures and the infection prevention and control (IPC) measures among patient-facing HCWs.

Design:

Test-negative case-control study.

Setting:

Provincial health system.

Participants:

HCWs with PCR-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) diagnosed between November 15, 2020, and May 29, 2021 (ie, cases), were compared to HCWs with compatible symptoms who tested negative during the same period (ie, controls).

Methods:

Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of infection were estimated using regression logistic models evaluating demographic and employment characteristics (all 4,919 cases and 4,803 controls) or household and workplace exposures and IPC measures (2,046 patient-facing cases and 1,362 controls).

Results:

COVID-19 risk was associated with working as housekeeping staff (aOR, 3.6), as a patient-support assistant (aOR, 1.9), and as nursing staff (aOR, 1.4), compared to administrative staff. Other risk factors included being unexperienced (aOR, 1.5) and working in private seniors’ homes (aOR, 2.1) or long-term care facilities (aOR, 1.5), compared to acute-care hospitals. Among patient-facing HCWs, exposure to a household contact was reported by 9% of cases and was associated with the highest risk of infection (aOR, 7.8). Most infections were likely attributable to more frequent exposure to infected patients (aOR, 2.7) and coworkers (aOR, 2.2). Wearing an N95 respirator during contacts with COVID-19 patients (aOR, 0.7) and vaccination (aOR, 0.2) were the measures associated with risk reduction.

Conclusion:

In the context of the everchanging SARS-CoV-2 virus with increasing transmissibility, measures to ensure HCW protection, including vaccination and respiratory protection, and patient safety will require ongoing evaluation.

Frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) have been greatly affected by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic worldwide. 1,2 In Canada, HCWs have been at higher risk of infection than the general population; they represented up to 19.4% of all cases recorded during the first wave. However, this rate has decreased to 4.4% since January 2021 following the vaccination campaign that began in December 2020. 2

Universal masking, screening for COVID-19, physical distancing, ventilation, vaccination, and standard infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, including personal protective equipment (PPE) use, are needed to minimize healthcare transmission. However, studies of risk factors and preventive measures for severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission in healthcare settings have yielded inconsistent results. 3–5

In Québec, the Canadian province with the highest reported number of infected HCWs, 2 a case–control study was conducted during the second and third pandemic waves to evaluate (1) the demographic and employment characteristics of HCWs associated with COVID-19 and (2) the association between the risk of infection and various exposures or IPC measures among patient-facing HCWs.

Methods

Study design and population

In this test-negative case–control study, participant data were extracted from the provincial laboratory COVID-19 database that contains records of all polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing in the province. HCWs who tested positive for the first time by PCR (ie, cases) were compared to a similar number of controls, randomly selected among test-negative HCWs who had COVID-19–compatible symptoms and no prior SARS-CoV-2 infection. The 1:1 case–control ratio was chosen balancing statistical power and logistic constrains for additional recruitment. During the peaks of the second pandemic wave (epi-weeks 2020-47 to 2021-05) and the third wave (epi-weeks 2021-14 to 2021-19), 750 controls per week were randomly sampled, whereas 550 controls were sampled in weeks with low case incidence (epi-weeks 2021-06 to 2021-13 and epi-weeks 2021-20 and 2021-21). 6 Cases and controls were censored after inclusion so that each HCW participated only once.

Eligible HCWs were those tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection by PCR between November 15, 2020, and May 29, 2021, and who had worked in any facility of Québec province during the 2 weeks prior to testing and spoke French or English.

The study period was mainly dominated by strains active before February 2021 (ie, the first wave) and SARS-CoV-2 α (alpha) variant cocirculation between February and May 2021 (ie, the second wave). 7 During this period, no influenza and few other respiratory viruses (<5% of adult cases), mainly characterized as rhinovirus or enterovirus, were detected in the hospital sentinel network for surveillance of respiratory viruses. 8 Vaccination of HCWs started in December 14, 2020, using an extended interval (up to 16 weeks) between the first and second doses.

Data collection

HCWs were contacted by phone between December 3, 2020, and July 31, 2021, and were invited to complete a self-administered online (or by phone if preferred) questionnaire sent to consenting participants fulfilling inclusion criteria (Supplementary Material 1 online). Collected data included information on demographic and employment characteristics as well as vaccination status (required since December 14, 2020). For each participant, a material deprivation index was assigned using an institutionally developed deprivation index, which is an ecological proxy based on residence ZIP code and area-based socioeconomic information. 9

Information was collected regarding workplace and household exposures during the 14 days prior to testing. Questions pertaining to workplace exposures and prevention measures followed during the 14 days prior to testing referred to patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 (a single category). The following information was collected regarding the training received since the beginning of the pandemic: (1) received no training, (2) received only written recommendations, or (3) training on COVID-19; among those having received a training an additional question asked if they had (4) received practical training on the use of PPE.

In Québec, recommendations for PPE use evolved during the study period. Before February 2021, an N95 mask was only required for aerosol-generating medical procedures (AGMPs) on COVID-19 patients. From mid-February onward, N95 mask use was required for any contact with confirmed COVID-19 patients. From the end of March onward, N95 mask use was required for any contact with suspected COVID-19 patients. 10,11

Data analysis

The association between risk of infection and demographic and employment characteristics was estimated with adjusted odds ratios (aORs) of infection and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) using a logistic regression model that included all predefined demographic and employment characteristics also adjusted for the health region.

To evaluate the impact of workplace exposures and IPC measures, a subsequent logistic regression model was added to adjust for health region, demographic, and employment characteristics. It included only cases and controls working in direct close contacts with patients (high-risk caregivers): patient support assistants (providing basic personal care to patients, such as hygiene, nutrition, positioning, and ambulation) and nursing staff and doctors working in acute-care hospitals (ACHs), long-term care facilities (LTCFs), and private seniors’ homes.

Variables with structural missing values were included in the models by including an interaction term between a nonmissing data indicator (eg, contact with COVID-19 patients) and the variable with missing data (eg, PPE use during contacts with COVID-19 patients), without including a main term for the variable with missing data. Sensitivity analyses using logistic regression conditional to calendar time (biweekly periods) to account for temporal risk variation did not change the estimations and were not included in the final models.

Ethical aspects

This survey was conducted under the legal mandate of the National Director of Public Health of Québec under the Public Health Act. It was also approved by the research ethics committee of the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Québec–Laval University. All participants gave verbal consent at the recruitment stage and an electronic consent when completing the online questionnaire.

Results

Participation in the study

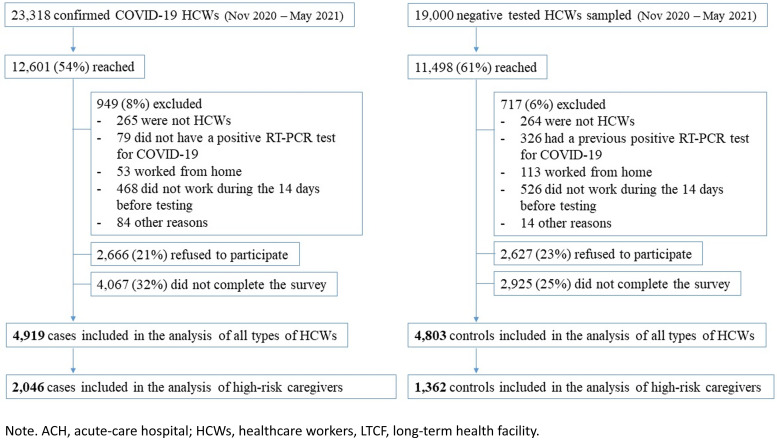

From the 23,318 HCWs with confirmed COVID-19 during the study period, 12,612 (54%) were reached and 949 (8%) were excluded (Fig. 1). The main reasons for exclusion were not being an HCW, not having a positive PCR test, working from home, and not having worked during the 14 days prior to testing. Additionally, 2,666 (21%) refused to participate and 4,067 (32%) agreed to participate but did not complete the survey, leaving 4,919 participant cases. From the 21,900 sampled controls, 11,498 (53%) were reached, 1,243 (11%) did not fulfill the inclusion criteria, 2,627 (23%) refused to participate, and 2,925 (25%) did not complete the survey, leaving 4,803 participant controls. Among them, 2,046 cases and 1,362 controls were high-risk caregivers working in 136 ACHs and >300 LTCFs and private seniors’ homes. They were included in the model evaluating workplace exposures and IPC practices.

Fig. 1.

Participants flowchart. Note. Nursing staff, patient-care assistants and physicians working in ACH, LTCF, or private residences for elderly are considered high-risk caregivers.

Demographic and employment risk factors for infection

The characteristics of cases and controls are displayed in Table 1. The risk of infection was significantly higher for HCWs self-identified as Black compared with non-Hispanic White participants (aOR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.7 to −3.0). Risk of infection was also independently associated with being male, being ≥40 years old, being born abroad, and having a native language different than French or English, but not with the material deprivation index (Table 1).

Table 1.

Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Sociodemographic and Employment Characteristics Among All Healthcare Workers a

| Variables | Prevalence | Odds Ratio of SARS-CoV-2 Infection | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (N = 4,919) | Controls (N = 4,803) | uOR | 95% CI | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Sex, male | 20.5 | 12.7 | 1.8 | 1.6–2.0 | 1.7 | 1.5–1.9 |

| Aged ≥40 y | 53.3 | 41.7 | 1.6 | 1.5–1.8 | 1.5 | 1.4–1.7 |

| Born abroad | 24.6 | 10.0 | 3.0 | 2.6–3.4 | 1.4 | 1.1–1.7 |

| Mother tongue other than French/English | 16.1 | 6.4 | 3.0 | 2.6–3.5 | 1.6 | 1.3–2.1 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White (non-Hispanic) | 74.7 | 89.6 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Black | 11.0 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 3.9–5.9 | 2.3 | 1.7–3.0 |

| Asiatic | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 1.7–3.2 | 1.3 | 0.9–1.9 |

| Hispanic | 2.8 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.7–3.1 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.5 |

| Arab | 3.7 | 2.0 | 2.2 | 1.7–2.9 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.3 |

| NR | 5.2 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.1–3.4 | 1.8 | 1.3–2.3 |

| Material deprivation index | ||||||

| Upper quartile | 23.9 | 27.5 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Two middle quartiles | 50.9 | 51.2 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.2 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.2 |

| Lower quartile | 25.2 | 21.4 | 1.3 | 1.1–1.5 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.2 |

| Type of employment | ||||||

| Admin/Management | 9.3 | 13.3 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Physician | 3.6 | 4.9 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.5 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.4 |

| Nursing personnel | 25.1 | 25.6 | 1.4 | 1.2–1.6 | 1.4 | 1.1–1.7 |

| Patient support assistant | 29.0 | 13.1 | 3.3 | 2.8–3.9 | 1.9 | 1.6–2.4 |

| Housekeeping | 3.8 | 1.0 | 5.3 | 3.8–7.6 | 3.6 | 2.5–5.4 |

| Social worker | 3.6 | 8.9 | 0.6 | 0.5–1.7 | 0.8 | 0.6–1.1 |

| Other b | 25.6 | 33.2 | 1.1 | 0.96–1.3 | 1.2 | 0.97–1.4 |

| Facility | ||||||

| ACH | 33.4 | 41.0 | Ref | Ref | ||

| LTCF | 22.8 | 12.2 | 2.4 | 2.2–2.8 | 1.5 | 1.2–1.9 |

| Private seniors’ homes | 12.0 | 4.1 | 3.5 | 3.0–4.3 | 2.1 | 1.6–2.6 |

| Other c | 31.8 | 42.7 | 0.9 | 0.8–1.0 | 1.1 | 0.97–1.3 |

| Private facility | 24.7 | 16.0 | 1.8 | 1.6–2.0 | 1.6 | 1.4–1.8 |

| Department | ||||||

| Admin | 8.9 | 12.2 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Elderly services | 20.7 | 9.9 | 3.0 | 2.5–3.5 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.5 |

| Medical departments | 15.0 | 9.9 | 2.1 | 1.7–2.5 | 1.8 | 1.5–2.3 |

| Emergency room | 6.0 | 6.5 | 1.3 | 1.1–1.6 | 1.2 | 0.9–1.5 |

| Intensive care unit | 4.6 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 |

| Clinics/external consultations | 7.1 | 13.4 | 0.7 | 0.6–0.9 | 0.7 | 0.6–0.9 |

| Other | 37.7 | 42.2 | 1.2 | 1.0–1.4 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.1 |

| Work experience <1 year | 21.8 | 11.9 | 2.1 | 1.9–2.4 | 1.5 | 1.3–1.7 |

| Work shift: evening or night | 21.0 | 12.7 | 1.8 | 1.6–2.0 | 1.1 | 0.97–1.2 |

| Working ≥40 hours per week | 16.7 | 12.7 | 1.4 | 1.2–1.5 | 1.3 | 1.2–1.5 |

| Compulsory overtime | 9.0 | 9.1 | 1.3 | 1.1–1.5 | 1.0 | 0.9–1.2 |

Note. ACH, acute-care hospital; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; LTCF, long-term care facility; NR; do not respond; ref, reference category; uOR, unadjusted odds ratio.

Logistic regression model adjusted for all presented characteristics and the health region.

Other types of employment: paramedic, security personnel, volunteer, stretcher bearer, kitchen staff, dentist or dental hygienist, special education teacher, building maintenance, laundry staff, occupational therapist, trainee, respiratory therapist, nutritionist, pharmacist or pharmacy assistant, physiotherapist, receptionist, laboratory technician, medical imaging technician, speech therapist, other.

Other facilities: health centers, clinics, rehabilitation center, other residential facilities, laboratory, pharmacy, nontraditional site for COVID-19 patient care, domiciliary work, administrative centers.

Compared with administrative staff, housekeeping staff was the occupation at highest risk after adjustment for race and/or ethnicity and other demographic variables (aOR, 3.6; 95% CI, 2.5–5.4), followed by patient-support assistants and nursing staff. Inexperienced workers (<1 year) and those working overtime (≥40 hours per week) had risks of infection increased by 50% and 30%, respectively. Notably, HCWs self-identified as Black were disproportionally represented in the occupations with highest infection risk: 10.3% of housekeeping staff and 16.6% of patient support assistants (compared to 6.4% of HCWs globally or 1.2% of physicians). Workers in private seniors’ homes and in LTCFs were more often infected than hospital staff (aOR, 2.1; 95% CI, 1.6–2.6 and aOR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.2–1.9, respectively), but HCWs in emergency rooms or intensive care units had no greater infection risk than administrative staff (Table 1).

Workplace exposures and IPC measures

Among high-risk caregivers, household exposure to a COVID-19 case, reported by 9% of cases and 3% of controls, was associated with the highest infection risk (aOR, 7.8; 95% CI, 5.2–11.8). ACH workers reported household exposure more often than LTCF workers, and this factor was associated with a greater infection risk (aOR, 13.0 vs 3.2). Exposures to COVID-19 patients (67% of cases and 43% of controls) and to COVID-19 coworkers (57% of cases and 35% of controls) were associated with 2.7- and 2.2-times higher risk of infection, respectively (Tables 2–4). Among LTCF workers, the highest risk of infection was associated with contacts with COVID-19 patients (aOR, 3.9) (Table 4). Between the prevaccination and postvaccination periods, the risk of infection increased among those exposed to a household member or coworker with COVID-19, but this risk decreased among those exposed to COVID-19 patients (Table 5).

Table 2.

Exposures to COVID-19 Individuals, Infection Control and Prevention Practices, and Vaccination Status of High-Risk Caregivers by Infection Status

| Variable | Cases (N = 2,046), No. (%) |

Controls (N = 1,362), (No. (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Exposures to COVID-19 | ||

| Household exposure to COVID-19 | 176 (8.6) | 38 (2.8) |

| Workplace exposure to COVID-19 patients | 1,365 (66.7) | 587 (43.1) |

| In a unit exclusive for COVID-19 patients | 577 (28.2) | 180 (13.2) |

| In a unit nonexclusive for COVID-19 patients | 709 (34.7) | 372 (27.3 |

| Outside a care unit (ambulatory patients) | 79 (3.9) | 35 (2.6) |

| Workplace exposure to COVID-19 coworkers | 1170 (57.2) | 475 (34.9) |

| Infection prevention and control measures | ||

| IPC training since the beginning of the pandemic | ||

| None | 45 (2.2) | 35 (2.6) |

| Only written recommendations | 189 (9.2) | 188 (13.8) |

| Any type of training | 1,812 (88.6) | 1,139 (83.6) |

| Practical training on PPE use | 1,605 (78.5) | 917 (67.3) |

| Always workplace masking | 1,946 (95.1) | 1,269 (93.2) |

| Always physical distancing if mask is not worn | 1,154 (56.4) | 712 (52.3) |

| Always hand washing after patient contact (among 2,014 cases and 1,274 controls) a | 1,893 (94.0) | 1,170 (91.8) |

| Always mask (medical mask or N95 respirator) use during contacts with non–COVID-19 patients (among 2,014 cases and 1,274 controls) a | 1,735 (86.1) | 1,118 (87.8) |

| Mask use during non-AGMP contacts with COVID-19 patients (among 1,365 cases and 587 controls) a | ||

| Not always mask | 84 (6.2) | 56 (9.5) |

| Medical mask | 1,154 (84.5) | 415 (70.7) |

| N95 respirator always or most of the time | 127 (9.3) | 116 (19.8) |

| Mask use during AGMP contacts with COVID-19 patients (among 186 cases and 173 controls) a | ||

| Not always mask | 18 (9.7) | 8 (4.6) |

| Medical mask | 53 (28.5) | 30 (17.3) |

| N95 respirator always or most of the time | 115 (61.8) | 135 (78.0) |

| Vaccination against COVID-19 | ||

| Unvaccinated | 1,755 (85.8) | 864 (63.4) |

| 1 dose 0–13 d before testing | 148 (7.2) | 112 (8.2) |

| 1 dose ≥14 d before testing | 136 (6.7) | 303 (22.3) |

| 2 doses 0–6 d before testing | 5 (0.2) | 27 (2.0) |

| 2 doses ≥7 d before testing | 2 (0.1) | 56 (4.1) |

Note. AGMP, aerosol-generating medical procedures; IPC, infection prevention and control; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Among cases and controls with the specified exposure (contact with patients, contact with COVID-19 patients, or AGMP contact with COVID-19 patients).

Table 4.

Adjusted Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Exposure to Infected Individuals, Infection Control and Prevention Practices and Vaccination Status Among High-Risk Caregivers, Stratified by Type of Facility

| Variable | ACH (N = 1,802) | LTCF (N = 1,167) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases, % | Controls, % | aOR | 95% CI | Cases, % | Controls, % | aOR | 95% CI | |

| Household exposure to COVID-19 | 13.0 | 2.5 | 13.0 | 7.4–22.8 | 5.3 | 3.9 | 3.2 | 1.5–6.8 |

| Workplace exposure to COVID-19 patients | 72.9 | 55.4 | 2.5 | 1.9–3.5 | 72.1 | 34.3 | 3.9 | 2.6–5.7 |

| Workplace exposure to COVID-19 coworkers | 56.7 | 35.4 | 2.3 | 1.7–3.1 | 64.0 | 38.0 | 2.2 | 1.4–3.3 |

| IPC training | ||||||||

| None | 1.4 | 3.2 | Ref | 2.1 | 1.7 | Ref | ||

| Only written recommendations | 12.5 | 15.3 | 1.5 | 0.6–3.8 | 5.5 | 8.4 | 0.6 | 0.2–2.5 |

| Any type of training | 86.1 | 81.5 | 2.3 | 0.9–5.5 | 92.5 | 90.0 | 1.2 | 0.4–4.4 |

| Hand washing after patient contact | ||||||||

| Not always | 5.4 | 8.6 | Ref | 4.3 | 2.3 | Ref | ||

| Always | 84.1 | 76.8 | 1.2 | 0.8–1.9 | 85.6 | 79.1 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.96 |

| Workplace masking | ||||||||

| Not always | 4.2 | 7.3 | Ref | 3.5 | 3.9 | Ref | ||

| Always | 95.8 | 92.7 | 1.3 | 0.7–2.1 | 96.5 | 96.1 | 0.6 | 0.2–1.5 |

| Physical distancing | ||||||||

| Sometimes/Never | 23.2 | 22.5 | Ref | 16.1 | 16.9 | Ref | ||

| Most of the time | 26.5 | 31.2 | 1.0 | 0.7–1.5 | 20.1 | 18.8 | 1.4 | 0.8–2.4 |

| Always | 50.3 | 46.3 | 1.5 | 1.1–2.2 | 63.8 | 64.4 | 1.4 | 0.9– 2.3 |

| Mask use during contact with non–COVID-19 patients | ||||||||

| Not always | 6.4 | 6.4 | Ref | 4.7 | 5.4 | Ref | ||

| Always | 77.2 | 77.0 | 1.0 | 0.6–1.6 | 82.8 | 76.8 | 1.3 | 0.6–2.5 |

| Mask use during non-AGMP contact with COVID-19 patients | ||||||||

| Medical mask | 54.9 | 34.9 | Ref | 65.4 | 28.9 | Ref | ||

| N95 always/most of the time | 10.8 | 13.1 | 0.6 | 0.4–0.9 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 0.3–2.8 |

| Mask use during AGMP contact with COVID-19 patients | ||||||||

| Medical mask | 4.2 | 3.4 | Ref | 1.8 | 0.8 | Ref | ||

| N95 always or most of the time | 13.0 | 16.7 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.8 | 0.1–11.1 |

| Vaccination against COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Unvaccinated | 85.4 | 66.0 | Ref | 85.2 | 55.4 | Ref | ||

| 1 dose 0–13 d before testing | 7.6 | 7.3 | 0.9 | 0.6–1.4 | 7.9 | 11.3 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.6 |

| ≥1 dose ≥14 d before testing | 7.0 | 26.7 | 0.3 | 0.2–0.4 | 6.9 | 33.3 | 0.2 | 0.1–0.3 |

Note. ACH, acute-care hospitals; AGMP, aerosol-generating medical procedures; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IPC, infection prevention and control; LTCF, long-term care facility; ref, reference category.

Table 5.

Adjusted Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Exposure to Infected Individuals, Infection Control and Prevention Practices, and Vaccination Status Among High-Risk Caregivers, Stratified by Period

| Variable | Prevaccination Period 15 Nov 2020 to 15 Jan 2021 |

Postvaccination Period 16 Jan 2021 to 29 May 2021 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases (N = 1,672), % |

Controls (N = 820), % |

aOR | 95% CI | Cases (N = 374), % |

Controls (N = 542), % |

aOR | 95% CI | |

| Household exposure to COVID-19 | 6.4 | 2.8 | 5.1 | 3.0–8.8 | 18.9 | 3.3 | 19.9 | 9.7–40.8 |

| Workplace exposure to COVID-19 patients | 74.3 | 56.3 | 3.4 | 2.6–4.4 | 52.8 | 35.9 | 1.9 | 1.2–3.0 |

| Workplace exposure to COVID-19 coworkers | 62.7 | 44.5 | 1.8 | 1.4–2.4 | 44.4 | 24.0 | 2.7 | 1.7–4.3 |

| IPC training | ||||||||

| None | 1.8 | 2.6 | Ref | 2.4 | 3.3 | Ref | ||

| Only written recommendations | 9.0 | 14.2 | 0.7 | 0.3–1.6 | 8.3 | 11.8 | 1.9 | 0.6–6.5 |

| Any type of training | 89.3 | 83.3 | 1.2 | 0.6–2.6 | 83.2 | 79.8 | 2.5 | 0.9–7.5 |

| Hand washing after patient contact | ||||||||

| Not always | 5.2 | 7.4 | Ref | 6.1 | 7.5 | Ref | ||

| Always | 92.8 | 87.4 | 1.1 | 0.7–1.6 | 82.1 | 73.9 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.9 |

| Workplace masking | ||||||||

| Not always | 4.5 | 5.3 | 4.8 | 8.2 | ||||

| Always | 95.5 | 94.7 | 1.0 | 0.6–1.7 | 95.2 | 91.9 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.4 |

| Physical distancing | ||||||||

| Sometimes/Never | 14.4 | 15.5 | Ref | 18.0 | 16.0 | Ref | ||

| Most of the time | 26.5 | 30.1 | 1.1 | 0.8–1.6 | 23.4 | 29.4 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.6 |

| Always | 59.1 | 54.5 | 1.4 | 1.0–1.9 | 58.5 | 54.6 | 1.4 | 0.8–2.4 |

| Mask use during contact with non–COVID-19 patients | ||||||||

| Not always | 6.0 | 5.8 | Ref | 4.3 | 6.1 | Ref | ||

| Always | 79.5 | 78.5 | 0.8 | 0.5–1.2 | 79.2 | 74.1 | 1.5 | 0.7–3.6 |

| Mask use during non-AGMP contact with COVID-19 patients | ||||||||

| Medical mask | 62.8 | 40.9 | Ref | 36.3 | 19.9 | Ref | ||

| N95 always/most of the time | 6.0 | 7.8 | 0.8 | 0.5–1.2 | 9.9 | 11.0 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.1 |

| Mask use during AGMP contact with COVID-19 patients | ||||||||

| Medical mask | 2.7 | 2.8 | Ref | 2.7 | 2.0 | Ref | ||

| N95 always or most of the time | 5.5 | 12.0 | 0.6 | 0.3–1.1 | 8.0 | 8.8 | 0.6 | 0.2–2.0 |

| Vaccination against COVID-19 | ||||||||

| Unvaccinated | 93.4 | 88.8 | Ref | 54.9 | 26.8 | Ref | ||

| 1 dose 0–13 d before testing | 5.4 | 8.5 | 0.6 | 0.4–0.9 | 15.5 | 7.5 | 1.1 | 0.6–2.1 |

| ≥1 dose ≥14 d before testing | 1.2 | 2.7 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.6 | 29.6 | 65.6 | 0.3 | 0.2–0.5 |

Note. ACH, acute-care hospitals; AGMP, aerosol-generating medical procedures; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; IPC, infection prevention and control; LTCF, long-term care facility; ref, reference category.

Among the 1,365 cases and 587 controls who reported having cared for confirmed or suspected COVID-19 patients, 9% of cases and 20% of controls had worn an N95 mask (Table 2). These proportions increased to 59% and 49%, respectively, during April and May 2021, when IPC recommendations were changed. Globally, N95 use was higher among HCWs in hospitals (16% of cases and 26% of controls), specifically in intensive care units (49% of cases and 62% of controls) (data not shown). N95 respirator use during non-AGMP contacts with COVID-19 patients was associated with a 30% lower risk of infection compared with medical mask use (aOR, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5–0.9) (Table 3). This result was consistent in all analyses stratified by facility and period, but the smaller sample size in each stratum precluded statistical significance (Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 3.

Multivariate Model of the Risk of SARS-CoV-2 Infection by Exposure, Infection Control and Prevention Practices and Vaccination Status Among High-Risk Caregivers

| Variable | Odds Ratio of SARS-CoV-2 Infection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| uOR | 95% CI | aOR a | 95% CI | |

| Household exposure to COVID-19 | 3.3 | 2.3–4.7 | 7.8 | 5.2–11.8 |

| Workplace exposure to COVID-19 patients | 2.6 | 2.3–3.1 | 2.7 | 2.2–3.3 |

| Workplace exposure to COVID-19 coworkers | 3.3 | 2.8–3.9 | 2.2 | 1.8–2.7 |

| IPC training | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | ||

| Only written recommendations | 0.8 | 0.5–1.3 | 0.7 | 0.4–1.2 |

| Any type of training | 1.2 | 0.8–1.9 | 0.9 | 0.5–1.6 |

| Hand washing after patient contact | ||||

| Sometimes/Never | Ref | Ref | ||

| Most of the time | 0.7 | 0.2–1.9 | 0.7 | 0.2–2.5 |

| Always | 1.0 | 0.4–2.7 | 0.8 | 0.2–2.5 |

| Workplace masking | ||||

| Sometimes/Never | Ref | Ref | ||

| Most of the time | 0.7 | 0.4–1.6 | 1.2 | 0.5–2.9 |

| Always | 1.1 | 0.6–2.3 | 1.2 | 0.6–2.7 |

| Physical distancing | ||||

| Sometimes/Never | Ref | Ref | ||

| Most of the time | 0.9 | 0.7–1.1 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.4 |

| Always | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 | 1.4 | 1.1–1.8 |

| Mask use during contact with non–COVID-19 patients | ||||

| Not always | Ref | Ref | ||

| Always | 1.1 | 0.9–1.5 | 1.0 | 0.7–1.4 |

| Mask use during non-AGMP contact with COVID-19 patients | ||||

| Medical mask | Ref | Ref | ||

| N95 respirator always or most of the time | 0.7 | 0.5–0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5–0.9 |

| Mask use during AGMP contact with COVID-19 patients | ||||

| Medical mask | Ref | Ref | ||

| N95 respirator always or most of the time | 0.5 | 0.3–0.8 | 0.7 | 0.4–1.2 |

| Vaccination against COVID-19 | ||||

| None | Ref | Ref | ||

| 1 dose 0–13 d before testing | 0.6 | 0.5–0.8 | 0.6 | 0.5–0.9 |

| ≥1 dose ≥14 d before testing | 0.2 | 0.1–0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2–0.3 |

Note. AGMP, aerosol-generating medical procedures; aOR, adjusted odds ratio; IPC, infection prevention and control; ref, reference category; uOR, unadjusted odds ratio. COVID-19 patients are those with suspected or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Logistic regression model adjusted for sex, age, born abroad, race/ethnicity, native language, type of employment, department, type of facility, health region and all other presented exposures, IPC practices, and vaccination status.

Training regarding infection prevention and control measures was reported by 89% of cases and 84% of controls, with 79% and 67%, respectively, having had practical training on PPE use (Table 2). General IPC measures intended to decrease workplace risk from unsuspected cases (eg, universal workplace masking, physical distancing, mask use during contacts with patients not suspected of COVID-19) were not associated with a decreased risk of infection (Table 3).

Vaccination with at least 1 dose was associated with an 80% reduction of the risk of infection (aOR, 0.2; 95% CI, 0.2–0.3) (Table 3).

Discussion

In this test-negative case–control study, conducted during the second and third COVID-19 pandemic waves, we detected an increased risk of infection in housekeeping staff and patient-support assistants, in unexperienced HCWs, and in those working in long-term and private facilities compared to ACHs. COVID-19 household exposure was associated with the highest risk of infection, but most of the infections were attributable to the more prevalent workplace exposures. The risk of infection was greater with exposure to infected patients than to infected coworkers, and this risk was more pronounced in LTCFs and during the second pandemic wave. The use of an N95 respirator during contact with COVID-19 patients and vaccination were the only measures associated with an infection risk reduction in these frontline HCWs.

Older participants and those of male sex were associated with 50% and 70% increased risks of infection, respectively. In several studies, the risk of infection increased with younger age, 3,5,12–15 which may be associated with community exposure risk unrelated to work, a question that was not asked in our study. Results regarding sex as an infection factor are inconsistent. 3,5,12,14,16,17 A meta-analysis reported that women are 50% more likely than men to adopt protective behaviors, which may explain the association between sex and infection observed in our study. 18 Self-reported Black race was associated with more than twice the risk of infection after adjustment for type of employment or deprivation index, similar to other studies among HCWs from the United States and Europe, 12,13,19–22 some of which also reported increased risk of seropositivity among Asian 19,22 or Hispanic staff. 13 Ethnic disparities in workplace COVID-19 exposures and less protection were reported from a UK survey conducted in summer 2020. 23 Although other characteristics identifying racial and linguistic minorities, like native language and being born abroad, were also independently associated with a 50% increase of infection risk, no association was found with the material deprivation index. This finding was also reported by a British study that simultaneously evaluated Black, Asian, and minority ethnicity and the Index of Multiple Deprivation score. 20

Specific occupational risk might be contextual to each health system or even each setting. In this study, the higher risk of infection was detected in nursing personnel and patient-support assistants but not in physicians is similar to findings elsewhere, 3,5,13,14,24–28 although others had divergent results. 3,24,25,28 In our study, housekeeping staff, a category that was not evaluated in most studies, was the type of employment with the highest risk of infection, exceeding that of personnel with close patient contacts. Other studies have also found the highest seroprevalence among housekeeping and domestic staff. 14,20,22 Waste management was the activity with more IPC protocol violations in hospital audits in a Korean study. 29 Similarly, a Canadian audit carried out during a facility outbreak in the summer of 2020 reported that errors in cleaning the environment were the most frequently identified. 30 Housekeeping staff tasks do not involve prolonged close contacts with patients, and their contamination by direct contact or droplet spread from COVID-19 patients should be infrequent. Whether the increased risk of housekeeping staff in Québec is related to lack of training and/or lack of adherence to IPC measures and their main routes of contamination remain to be clarified.

Similar to the literature, in our study the highest risk of transmission among HCWs was associated with COVID-19 contacts in the household (13-fold), where infection prevention measures may not be routinely followed and prolonged contacts at short distances occur frequently. 5,13,14,22,27,31 Household exposure was only reported by 9% of high-risk caregiver cases during the study period. This low prevalence of nonoccupational contacts might be to due underreporting associated with undetected asymptomatic infections or to the lack of benefit of occupational insurance coverage for HCWs reporting household acquisition. On the other hand, it could also be related to public health policies restricting social contacts that limited COVID-19 transmission in general population during the study period. Self-reported household exposure increased between November 2020 and May 2021 from 7% to 37% among high-risk HCWs and from 14% to 34% among all HCWs, in line with the increasing COVID-19 community incidence. 32 Most infections are thus likely attributed to exposure to SARS-CoV-2–infected patients (67% of cases) and coworkers (57% of cases). Although several studies have also reported that workplace exposures to COVID-19 patients or coworkers were associated with a risk of COVID-19 twice as high or higher, 5,14,15,27 other publications have reported no greater risk of infection. 4,12,21 These contradictory results may reflect the period when the study was carried out, the types of facilities, local differences in the epidemiology of the pandemic, and differences in the implementation of and compliance with IPC measures.

Protection against SARS-CoV-2 by N95 respirators versus surgical masks has not been evaluated in any randomized trial. Reviews summarizing observational real-life studies in healthcare settings concluded that evidence had insufficient strength to determine the benefit of N95 over medical masks or that this benefit had low certainty. 33,34 In our observational study, HCWs who wore an N95 during non-AGMP contacts with COVID-19–infected patients had an estimated 30% lower risk compared to those who used surgical masks. Wilson et al 36 reported higher protection for French HCWs mainly wearing respirators when caring for COVID-19 patients during AGMPs (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4–0.7) or during any (AGMP or non-AGMP) contact (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.3–0.5). Lentz et al 35 conducted an international online survey among 1,130 HCWs and described a risk reduction only when respirators were used for all types of contact with COVID-19 patients (OR, 0.4; 95% CI, 0.2–0.8). Haller et al 37 reported a relative risk reduction only significant for those with frequent contact with COVID-19 patients (hazard ratio, 0.7; 95% CI, 0.5–0.8) in a multicenter cohort of 3,259 HCWs in Switzerland. However, other studies have shown nonsignificant differences or inconsistent results according to the type of contact or the setting, which probably reflects the difficulties in measuring the use of respirators in observational studies. 13,27,35,38,39 Furthermore, both N95 and surgical masks might be used, making it difficult to isolate the effect of each mask. More importantly, many studies do not specifically measure the IPC practices during the incubation period. Although our results on the protective effect of N95 might also be explained by a higher compliance with other IPC measures among those also using N95 masks, we did not observe a risk reduction associated with other IPC practices, as would have been expected if N95 use was indirectly measuring other protective practices.

Although epidemiological studies have limitations precluding the demonstration with high certainty of the superiority of N95 masks over surgical masks, the findings of this study suggest that additional protection may be conferred by wearing an N95 respirator during contact with COVID-19 patients.

This study has several limitations. Its observational design is susceptible to residual confounding due to potential lack of comparability in exposures of cases and controls, as well as unmeasured confounding factors such as outbreaks in the units and environmental and infection control characteristics of the facilities. The subpopulation of high-risk caregivers used to evaluate exposures and IPC practices probably improved the comparability between cases and controls. Self-reported compliance with IPC practices is subject to desirability and/or recall bias and may have underestimated their protective effect. For instance, participants reported very strong adherence (>90%) to hand hygiene measures, which contrasts with results of audits on the practice of hand hygiene in some hospitals in the province showing that compliance varies between 63% and 70% (Institut national de santé publique du Québec, December 2020, unpublished document). The test-negative design of this study is also susceptible to selection bias for identifying risk factors of infection. 40 The smaller number of HCWs reporting contacts with COVID-19 patients from February to June 2021 limited the statistical power to evaluate preventive measures in analyses stratified for the period. Moreover, the relatively small number of participants in some groups (eg, physicians and housekeeping staff) resulted in less precise estimates of associations. Finally, the information gathered covered a 14-day period and may not be representative of the circumstances at the time of the contact leading to infection.

In conclusion, HCWs remain at higher risk of COVID-19 than the general population. Those with close and frequent patient contacts will most benefit from vaccination and respiratory protection. Their protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection will continue to be of paramount importance in preserving the safety of both the healthcare workforce and patients in a context of everchanging new variants that can bypass vaccine and natural immunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Armelle Lorcy (CHU de Québec-Université Laval Research Center) for her contribution to the large epidemiological survey conducted to evaluate COVID-19 workplace exposure, infection risk, and prevention in healthcare workers in Québec. We thank also Olivia Drescher (Centre de Recherche du CHU de Québec – Université Laval) for her collaboration in the estimation of the material deprivation index. Finally, we would like to thank all the healthcare workers that participated to this study.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2022.231.

click here to view supplementary material

Financial support

This work was supported by the Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec.

Conflict of interest

S.C. and G.D.S. report funding from the Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec to conduct this work, paid to their institution. G.D.S. received a grant from Pfizer for an antimeningococcal immunogenicity study not related to this study. Y.L. received grants from Becton Dickinson and Merck for investigator-initiated studies unrelated to this work. G.D. received payment from the University of Montreal for epidemiology teaching lessons for medical students. D.T. is supported by a research career award from the Fonds de recherche du Québec-Santé, paid to his institution. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

References

- 1. COVID data tracker. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#health-care-personnel. Published 2022. Accessed April 15, 2022.

- 2. COVID-19 cases and deaths in healthcare workers in Canada. Canadian Institute for Health Information website. https://www.cihi.ca/en/covid-19-cases-and-deaths-in-health-care-workers-in-canada. Published 2022. Accessed April 15, 2022.

- 3. Jespersen S, Mikkelsen S, Greve T, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 seroprevalence survey among 17,971 healthcare and administrative personnel at hospitals, prehospital services, and specialist practitioners in the central Denmark region. Clin Infect Dis 2020;ciaa1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4. Yassi A, Grant JM, Lockhart K, et al. Infection control, occupational and public health measures including mRNA-based vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 infections to protect healthcare workers from variants of concern: a 14-month observational study using surveillance data. PLoS One 2021;16:e0254920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wilkins JT, Gray EL, Wallia A, et al. Seroprevalence and correlates of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in healthcare workers in Chicago. Open Forum Infect Dis 2020;8:ofaa582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Données Covid-19 au Québec. Institut national de santé publique du Québec website. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees. Published 2022. Accessed April 15, 2022.

- 7. Données sur les variants du SRAS-CoV-2 au Québec. Institut national de santé publique du Québec website. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/covid-19/donnees/variants. Published 2022. Accessed April 15, 2022.

- 8. Gilca R, Amini R, Carazo S, et al. The changing landscape of respiratory viruses contributing to respiratory hospitalisations: results from a hospital-based surveillance in Québec, Canada, 2012–13 to 2021–22. medRxiv 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.07.01.22277061v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9. Gamache P, Hamel D, Blaser C. Material and social deprivation index: a summary. Institut national de santé publique du Québec website. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/publications/2639_material_social_deprivation_index.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed April 15, 2022.

- 10.COVID-19—la CNESST oblige le port du N95 ou d’une protection supérieure en zone chaude. Commission des normes de l’équité de la santé et de la sécurité du travail website. https://www.cnesst.gouv.qc.ca/fr/salle-presse/communiques/covid-19-cnesst-oblige-port-n95-dune-protection. Published 2021. Accessed May 15, 2022.

- 11.COVID-19—la CNESST oblige également le port du N95, ou d’une protection supérieure, en zone tiède. Commission des normes, de l’équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail website. https://www.cnesst.gouv.qc.ca/fr/salle-presse/communiques/n95-zone-tiede. Published 2021. Accessed May 15, 2022.

- 12. Jacob JT, Baker JM, Fridkin SK, et al. Risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity among US healthcare personnel. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e211283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Akinbami LJ, Chan PA, Vuong N, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 seropositivity among healthcare personnel in hospitals and nursing homes, Rhode Island, USA, July–August 2020. Emerg Infect Dis 2021;27:823–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wratil PR, Schmacke NA, Osterman A, et al. In-depth profiling of COVID-19 risk factors and preventive measures in healthcare workers. Infection 2021;50;381–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vitrat V, Maillard A, Raybaud A, et al. Effect of professional and extra-professional exposure on seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among healthcare workers of the French Alps: a multicentric cross-sectional study. Vaccines 2021;9:824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Iversen K, Bundgaard H, Hasselbalch RB, et al. Risk of COVID-19 in healthcare workers in Denmark: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:1401–1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erber J, Kappler V, Haller B, et al. Infection control measures and prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 IgG among 4,554 university hospital employees, Munich, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis 2022;28:572–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moran KR, Del Valle SY. A meta-analysis of the association between gender and protective behaviors in response to respiratory epidemics and pandemics. PLoS One 2016;11:e0164541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shorten RJ, Haslam S, Hurley MA, et al. Seroprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare workers in a large teaching hospital in the northwest of England: a period prevalence survey. BMJ Open 2021;11:e045384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shields A, Faustini SE, Perez-Toledo M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and asymptomatic viral carriage in healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. Thorax 2020;75:1089–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baker JM, Nelson KN, Overton E, et al. Quantification of occupational and community risk factors for SARS-CoV-2 seropositivity among healthcare workers in a large US healthcare system. Ann Intern Med 2021;174:649–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eyre DW, Lumley SF, O’Donnell D, et al. Differential occupational risks to healthcare workers from SARS-CoV-2 observed during a prospective observational study. Elife 2020;9:e60675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kapilashrami A, Otis M, Omodara D, et al. Ethnic disparities in health and social care workers’ exposure, protection, and clinical management of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK. Crit Public Health 2022;32:68–81. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Naesens R, Mertes H, Clukers J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence survey among health care providers in a Belgian public multiple-site hospital. Epidemiol Infect 2021;149:e172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. van der Plaat DA, Madan I, Coggon D, et al. Risks of COVID-19 by occupation in NHS workers in England. Occup Environ Med 2021. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2021-107628. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26. Poletti P, Tirani M, Cereda D, et al. Seroprevalence of and risk factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection in healthcare workers during the early COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2115699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Belan M, Charmet T, Schaeffer L, et al. SARS-CoV-2 exposures of healthcare workers from primary care, long-term care facilities and hospitals: a nationwide matched case-control study. medRxiv 2022. doi: 10.1101/2022.02.26.22271545v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. Zheng C, Hafezi-Bakhtiari N, Cooper V, et al. Characteristics and transmission dynamics of COVID-19 in healthcare workers at a London teaching hospital. J Hosp Infect 2020;106:325–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choi UY, Kwon YM, Kang HJ, et al. Surveillance of the infection prevention and control practices of healthcare workers by an infection control surveillance-working group and a team of infection control coordinators during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Infect Public Health 2021;14:454–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Picard C, Edlund M, Keddie C, et al. The effects of trained observers (dofficers) and audits during a facility-wide COVID-19 outbreak: a mixed-methods quality improvement analysis. Am J Infect Control 2021;49:1136–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Science M, Bolotin S, Silverman M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in Ontario healthcare workers during and after the first wave of the pandemic: a cohort study. CMAJ Open 2021;9:E929–E939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. De Serres G, Carazo S, Villeneuve J, Laliberté D. Enquête épidémiologique sur les travailleurs de la santé atteints par la COVID-19. Institut national de santé publique du Québec website. https://www.inspq.qc.ca/sites/default/files/publications/3192-enquete-epidemiologique-travailleurs-sante-covid-19.pdf. Published 2022. Accessed May 15, 2022.

- 33. Chou R, Dana T, Jungbauer R. Update alert 7: masks for prevention of respiratory virus infections, including SARS-CoV-2, in healthcare and community settings. Ann Intern Med 2022;175:W58–W59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2020;395:1973–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lentz RJ, Colt H, Chen H, et al. Assessing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) transmission to healthcare personnel: the global ACT-HCP case–control study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020. doi: 10.1017/ice.2020.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36. Wilson S, Mouet A, Jeanne-Leroyer C, et al. Professional practice for COVID-19 risk reduction among health-care workers: a cross-sectional study with matched case–control comparison. PLoS One 2022;17:e0264232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Haller S, Güsewell S, Egger T, et al. Impact of respirator versus surgical masks on SARS-CoV-2 acquisition in healthcare workers: a prospective multicentre cohort. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2022;11:27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Guo X, Wang J, Hu D, et al. Survey of COVID-19 disease among orthopaedic surgeons in Wuhan, People’s Republic of China: J Bone Jt Surg Am 2020;102:547–554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. O’Hara LM, Schrank GM, Frisch M, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) symptoms, patient contacts, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positivity and seropositivity among healthcare personnel in a Maryland healthcare system. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2021. doi: 10.1017/ice.2021.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40. Schnitzer ME, Harel D, Ho V, Koushik A, Merckx J. Identifiability and estimation under the test-negative design with population controls with the goal of identifying risk and preventive factors for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Epidemiology 2021;32:690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ice.2022.231.

click here to view supplementary material