Abstract

Systemic and mucosal humoral immune responses are crucial to fight respiratory viral infections in the current pandemic of COVID-19 caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus. During SARS-CoV-2 infection, the dynamics of systemic and mucosal antibody infections are affected by patient characteristics, such as age, sex, disease severity, or prior immunity to other human coronaviruses. Patients suffering from severe disease develop higher levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in serum and mucosal tissues than those with mild disease, and these antibodies are detectable for up to a year after symptom onset. In hospitalized patients, the aberrant glycosylation of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies enhances inflammation-associated antibody Fc-dependent effector functions, thereby contributing to COVID-19 pathophysiology. Current vaccines elicit robust humoral immune responses, principally in the blood. However, they are less effective against new viral variants, such as Delta and Omicron. This review provides an overview of current knowledge about the humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2, with a particular focus on the protective and pathological role of humoral immunity in COVID-19 severity. We also discuss the humoral immune response elicited by COVID-19 vaccination and protection against emerging viral variants.

Introduction

In December 2019, a new coronavirus emerged, attracting considerable attention worldwide. The SARS-CoV-2 virus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2), a member of the betacoronavirus family, went on to cause the current COVID-19 pandemic1. More than 460 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 have been reported to date, with more than six million deaths2. COVID-19 disease is highly variable in terms of clinical outcome, ranging from asymptomatic or mild disease, resembling a common cold, to more severe disease, including acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring hospitalization with oxygen therapy, or even death3.

The genome of SARS-CoV-2 encodes structural proteins (the spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins) essential for virion formation. S protein has two subunits (S1 and S2) separated by a furin cleavage site crucial for viral infection and distinguishing this virus from its relative, SARS-CoV4. The S protein contains the receptor-binding domain (RBD), which binds to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in host cells. ACE2 acts as the viral receptor, mediating virus entry and triggering an immune response in the host to eliminate the virus. S protein is, therefore, one of the principal targets of antibody-based immunotherapies and vaccines. S protein mutations have generated a wide spectrum of emerging variants, (variants of concern (VOC)) with different phenotypes affecting transmission and antibody sensitivity.

The immune response to pathogens is characterized by the activation of innate and adaptive responses, and their humoral and cellular components. Antibodies play a crucial role in protection against viral diseases via various mechanisms involving both their Fab and corresponding Fc portions. The Fab-mediated mechanisms include neutralization, in which the entry of the virus into the host cell is sterically blocked. Fc mechanisms include complement activation, antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC), and antibody-dependent phagocytosis (ADP). However, antibody effector functions can also exacerbate inflammation and generate more damage, as in the antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) observed in dengue disease5.

This review summarizes current knowledge about the humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2, highlighting the differences and points in common between systemic and mucosal humoral immune responses to the virus. We focus on the role of the antibody response, particularly the mucosal response, and its possible involvement in determining COVID-19 severity. We discuss the humoral immune response elicited by COVID-19 vaccination, together with protection against emerging viral variants. The modulatory effect of pre-existing immunity to other coronaviruses on the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 is also considered.

Systemic humoral response in COVID-19

The proportions of total IgA, IgM and IgG antibodies and of total IgG subclasses are not modified following SARS-CoV-2 infection6. However, anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody production varies with disease severity and depends on patient characteristics, such as sex and age (Fig. 1 ). Indeed, many studies have reported that specific antibody titers (even for antibodies directed against non-structural proteins and accessory proteins) are higher in patients with moderate/severe disease than in patients with asymptomatic/mild disease over the course of the infection7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17. Antibody levels are also higher in men than in women8, 18, 19, an observation that can be accounted for by the higher levels of ACE2 expression in men than in women20, rendering men more susceptible than women to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Similar differences between the sexes have been reported for other viruses, including MERS, SARS-CoV, Epstein Barr virus, HBV, HCV, and West Nile virus21. The humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 can also be modulated by the patient's age. Indeed, older patients with severe disease present more anti-spike IgG, IgM and IgA antibodies than younger patients15, 22, but this may also be due to confounding factors, such as comorbid conditions23. Furthermore, immunosenescence24 and inflammageing25 may also contribute to the more severe disease observed in older individuals. In addition, adults may have an ineffective, dysregulated innate immune response, leading to uncontrolled pro-inflammatory cytokine production (cytokine storm), and tissue injury26. The serum immune responses of children to the SARS-CoV-2 virus are limited to anti-spike IgG antibodies, whereas adults also produce anti-N IgG antibodies22. This observation is consistent with the milder course of infection in younger individuals, resulting in the release of smaller amounts of N protein from cells infected with the virus. Nevertheless, after mild COVID-19, children and adults have similar levels of anti-RBD IgG antibodies with similar abilities to inhibit RBD-ACE2 interactions18.

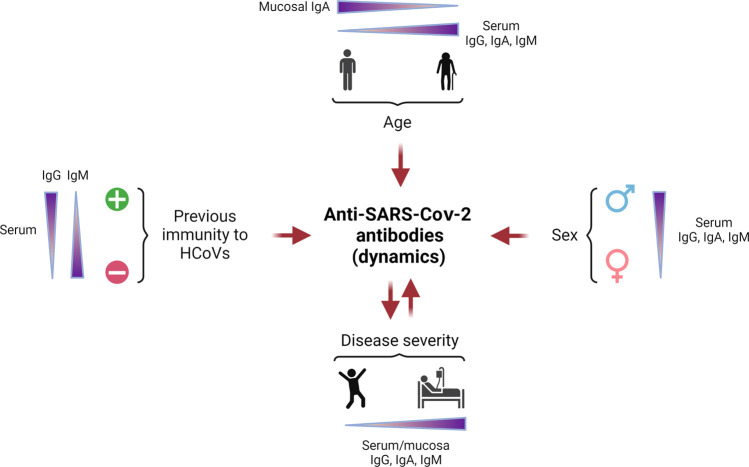

Fig. 1.

Factors affecting the dynamics of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

The characteristics of the patient can modulate the anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody response. Specific IgG, IgA and IgM levels in serum are high in elderly individuals, whereas the mucosal IgA levels are low in these individuals, contrasting with the situation in young patients, who have lower anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers in serum and higher levels of mucosal IgA. Titers of specific IgG, IgA, and IgM in serum are higher in male than in female patients. Patients previously infected with another human coronavirus (HCoV) (represented by the “+” symbol) develop more anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG than IgM in serum, whereas the contrary occurs in patients with no previous immunity to HCoV (represented by the “-” symbol). Disease severity can also modulate specific responses in patients, as a more severe disease is associated with higher titers of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG, IgA, and IgM in serum. The quality and quantity of these antibodies can also modify disease severity. (Created with www.Biorender.com).

Serum IgG, IgA and IgM antibodies are elicited principally against the spike (S1, S2 and RBD domains) and nucleocapsid proteins10, 12, 14, 16, 22, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33 (Fig. 2 ). Interestingly, both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients produce antibodies directed principally against S234. The fusion peptide (FP) is the region most frequently targeted by specific IgM, IgG and IgA in both groups of patients, but antibodies against this region are underrepresented in the specific IgG and IgA epitope repertoires in symptomatic patients compared to asymptomatic ones34. Conversely, the anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA antibodies in the serum of symptomatic patients better recognize the N-terminal domain (NTD) and RBD in S1 than those in the serum of asymptomatic patients34. These differences in antibody repertoire can modulate the efficacy of the immune response and, therefore, disease outcome34. In addition, the affinity of the antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 prefusion spike detected in the serum and nasal washes has been shown to be significantly higher in asymptomatic adults than in symptomatic COVID-19 patients34, suggesting that the antibody response in asymptomatic patients is more effective at controlling the infection than that in symptomatic patients. Some studies have reported higher levels of IgG avidity maturation in patients with severe disease, indicating the presence of larger numbers of memory B cells and/or long-lived plasma cells, which could be rapidly restimulated to prevent reinfection11, 16. However, even though reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is a rare event, occurring in less than 1% of COVID-19 cases, patients with a previous severe infection and those over the age of 65 years are more prone to reinfection35, 36, suggesting that natural immunity cannot be relied upon for protection.

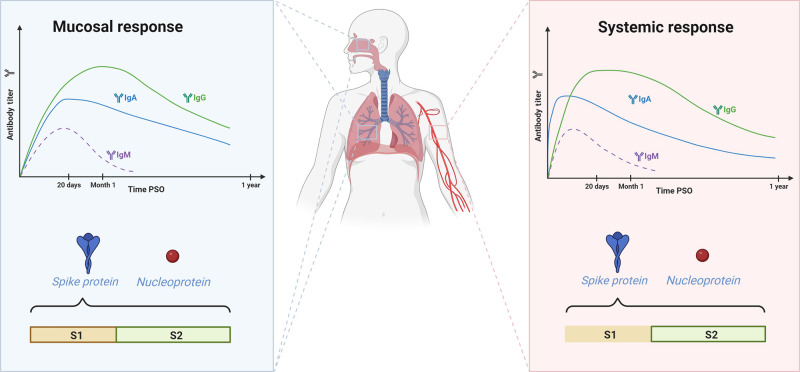

Fig. 2.

Mucosal and systemic humoral immune responses to SARS-CoV-2.

Both mucosal and systemic humoral immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 are characterized by a transient IgM response detectable until 1month post-symptom onset (PSO). The mucosal response is dominated by IgG and IgA, whereas the systemic response is initially dominated by IgA. Specific IgA and IgG antibodies are detected in mucosal tissues even at 9 months PSO, and such antibodies are detected in the serum until 1-year PSO. Both responses are directed against the spike protein and nucleoprotein. Despite the targeting of epitopes in the S1 and S2 subunits of the spike protein in both responses, the mucosal response is more diverse (represented by the line around the S1 and S2 rectangles) than the systemic response, in which the epitopes targeted lie principally in the S2 subunit (marked with the line only in the S2 rectangle). (Created with www.Biorender.com).

By contrast to other infections, IgM are not the first antibodies to appear in the blood of patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 patients37, probably due to prior immunity to other coronaviruses, as discussed below. Indeed, specific IgA is the predominant isotype in the first week post-symptom onset (PSO); there is then a peak of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM between 10 and 15 days PSO and an IgG peak around day 20 PSO11, 13, 30, 32, 33, 38, 39 (Fig. 2). IgM levels decrease significantly one-month PSO33, but specific IgA and IgG levels in the blood remain stable more than 6 weeks PSO39, 40 and IgG can be detected for up to 1 year PSO11, 12, 29, 30, 41, 42, 43. However, asymptomatic patients have lower levels of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and they, therefore, lose their specific IgG antibodies faster and more frequently than symptomatic patients14. The spike-specific IgG1 and IgG3 subclasses predominate over IgG2 and IgG4 in SARS-CoV-2-infected patients40, 44, 45, 46, as in other viral infections, with HIV47 or H1N1 influenza virus, for example48. The presence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA in serum is associated with gastrointestinal symptoms in COVID-19, whereas no such association has been found for IgG32. SARS-CoV-2 can replicate in human enterocytes49 and may activate the local production of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA, contributing to an increase in specific IgA levels in the blood.

Antibodies from the serum of COVID-19 patients have been shown to cross-react with the spike proteins of the four seasonal human coronaviruses (HCoVs: 229E, HKU1, NL63, and OC43)50. It remains a matter of debate whether prior immunity to HCoV is protective against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Several studies have reported that the levels of specific IgG and IgA against HCoVs are significantly higher in asymptomatic than in symptomatic COVID-19 patients, suggesting that prior HCoV infection can modulate COVID-19 severity51, 52, 53, 54. By contrast, other studies found no significant correlation between prior anti-HCoV immunity and COVID-19 severity27, 55, 56. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG titers are higher in patients with prior seasonal coronavirus immunity57 (Fig. 1), suggesting that the SARS-CoV-2 specific response is a recall-type response and should be protective. Cross-reactivity between OC43- and 229E-specific antibodies and SARS-CoV-2 proteins may be higher in children than in adults58, probably due to the high frequency of respiratory illnesses during childhood59, 60. It has also been suggested that prior HCoV immunity in children is protective against SARS-CoV-2 infection, as children develop less severe forms of COVID-19 than adults61. Several regions in the S2 subunit of the spike protein are homologous between HCoVs and SARS-CoV-2, but there is no homology in the RBD region62 and specific antibodies directed against HCoVs cannot neutralize SARS-CoV-2 in vitro57. Moreover, SARS-CoV-2 infection can occur in children regardless of their prior HCoV immunity63 and specific antibodies against HCoVs in children are unable to block SARS-CoV-2-RBD-ACE2 interaction58. Most of these observations were made with serum samples, but it is also very important to understand whether the mucosal response is induced similarly in all types of COVID-19 patients.

Mucosal humoral immunity in COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2 displays pulmonary tropism. Mucosal immune responses therefore probably play a crucial role in preventing the entry and spread of the virus Box 1. Only a few studies have investigated the kinetics and quality of the mucosal immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Mucosal responses, particularly anti-spike IgM, are inversely correlated with the viral load in nasopharyngeal swabs, indicating that a strong early nasal antibody response may play a key role in limiting disease by initiating or facilitating early viral clearance64. An association has also been reported between a strong nasal antibody response, specifically anti-RBD IgA, and the resolution of systemic symptoms, such as fatigue, fever, headache, dizziness, joint or muscle pain, and swollen lymph nodes64. Early control of viral replication in the upper respiratory tract, reducing the spread of the virus to the periphery, thereby limiting systemic symptoms, might account for this association. Specific anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies have been detected in the saliva31, 42, 65, nasopharynx6, 38, 64, 66, 67, 68, 69, bronchoalveolar lavages (BAL)31 and trachea of children70, and these antibodies are directed against S, RBD and N proteins6, 31, 42, 64, 65, 68. Limited data are available for stool samples, with only one study reporting minimal differences in anti-S IgA and IgG antibodies between infected and non-infected patients71, and another study detecting anti-RBD IgA antibodies in 11% of patients, particularly those with the most severe disease or presenting diarrhea72. Total IgM and IgG (including IgG subclasses) levels in nasal fluid, like those in serum, are similar in healthy donors and COVID-19 patients. By contrast, total IgA levels increase with disease severity6. As in the systemic humoral immune response, specific antibody titers in mucosal tissues are higher in moderate/severe disease than in asymptomatic/mild disease, over the course of the infection6, 7, 66 (Fig. 1). Interestingly, anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgA titers in mucosal tissues are inversely correlated with age in mild disease patients with low or absent specific serum response38. This can be explained, as suggested by Cervia et al. in 2021, that the extent and the duration of clinical symptoms modulate the immune response38 and that a good mucosal immune response may be sufficient to control viral replication when presenting mild or asymptomatic disease. However, the mucosal immune response provides insufficient protection against infection with the Omicron variant. SARS-CoV-2-infected children have very low levels of neutralizing antibodies in the lower respiratory tract70. Ravichandran et al. used genome fragment phage display library (GFPDL) technology to study epitope recognition by specific IgM, IgG and IgA antibodies in nasal secretions34. They found that IgM, IgA and IgG responses generally targeted a broader spectrum of epitopes in the NTD, RBD, FP, heptad repeat 1 (HR1) and HR2 regions distributed throughout the S1 and S2 subunits of the spike protein, whereas the systemic response was essentially restricted to S234. Interestingly, both monomeric and dimeric IgA were detected in the BAL of COVID-19 patients31 suggesting that anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in mucosal tissues may have different origins. Most of the dimeric IgA probably arises locally, but plasma monomeric IgA can reach the airways through a receptor-independent process called transudation, which is more likely to occur in damaged lung tissue, as observed in patients with severe COVID-1973, 74.

As described for other infections75, the IgG/IgA ratio follows a gradient down the respiratory tract, with higher titers of IgA than of other isotypes in saliva, but higher IgG titers than IgA titers in BAL31. IgG has been described as the predominant immunoglobulin in the saliva at the start of the disease7 (Fig. 2). Indeed, anti-SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG levels peak between days 31–45 PSO, and disappear at about day 106–115 PSO, whereas IgM and IgA appear at about day 20 PSO but their levels decrease more rapidly than those of IgG65. Specific anti-RBD IgA levels were found to be higher in saliva than in serum after day 49 PSO31, whereas airway-specific IgA and IgG levels declined significantly within three months of infection69. However, these antibodies remained detectable until nine months PSO42, 64. As in serum, the milder the disease, the shorter the life of the specific antibodies detected in mucosal tissues42

In conclusion, systemic and mucosal responses vary according to disease severity and infection kinetics. When studying the humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, we are monitoring the strength of the immune response triggered by the infection rather than the quality of this response to protect patients against the more severe disease. Even though there could be detrimental features of the individual immune response that could hamper the good evolution of the disease, what is the ultimate role of aantibodies during the infectious process?

Box 1 Humoral immune response to other coronaviruses

To date, seven coronaviruses infecting humans have been identified. Four of these viruses (human coronavirus (HCoV) -229E, -NL63, -OC43, and -HKU1) circulate as endemic strains and cause relatively mild common cold symptoms165. However, infection with these viruses can lead to the hospitalization of immunocompromised, elderly, or very young individuals59, 166. Children may be protected during the first three months after birth by anti-HCoV antibodies transferred from the mother59. Anti-S IgG and IgM antibodies against the four HCoVs can be detected in children, their frequency increasing with age to a plateau at 6 years of age, whereas no anti-S IgM is detected in healthy adults, suggesting that most HCoV infections occur in infancy or early childhood59, 167, 168, 169. Nevertheless, binding, and neutralizing antibody titers are higher in older adults170, in whom there is more anti-HCoV IgG in serum than specific IgA in nasal washes171. Antibody responses to HCoVs are not well maintained, and reinfections are common within 12 months172. Antibody repertoires against HCoVs differ qualitatively between children and adults. In children, anti-HCoV IgG antibodies target functionally important and structurally conserved regions of the spike, nucleocapsid, and matrix proteins173.

The other three coronaviruses—the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), SARS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2—can cause life-threatening respiratory infections165, 174, 175. Serum from SARS-CoV-convalescent patients contains cross-reactive antibodies against other HCoVs176, 177, 178, but not cross-neutralizing antibodies179. Anti-N SARS-CoV-specific IgA, IgM and IgG antibodies in serum can be detected within 1 week of the onset of illness, and they peak at about day 15 post-symptom onset (PSO)180, 181, 182. SARS-CoV-specific IgM antibodies are detected until 7 months PSO, but titers decline after the first month. By contrast, neutralizing antibody and SARS-CoV-specific IgG antibody titers remain stable over this period181, 182, 183. Anti-SARS-CoV IgA avidity remains low in a proportion of patients, even during late convalescence, whereas IgG avidity increases with time until 9 months PSO182.

Antibody-dependent protective functions in COVID-19

Fc-effector functions, such as ADP, have been associated with protection against other coronaviruses or HIV. Shiakolas et al. showed that six monoclonal antibodies from SARS-CoV patients that cross-reacted with SARS-CoV-2 virus-induced ADP but not neutralization in vitro, and that this Fc-effector function was associated with milder hemorrhagic disease in mouse lungs76. Furthermore, in a nonhuman primate model, Spencer et al. showed that the bNAb 10E8v4 displayed ADP reducing HIV viremia in non-neutralizing conditions77.

In vivo studies of SARS-CoV-2 infection have suggested that the humoral immune response is protective. For instance, a mixture of S309 and S2M11 monoclonal antibodies isolated from convalescent individuals and with different mechanisms of binding to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein yielded additive neutralizing effects and elicited robust ADCC and ADP in hamsters78, 79. In an FcγR-humanized mouse model, Yamin et al. showed that the REGN monoclonal antibody cocktail (currently in clinical use) induced protection against lethal SARS-CoV-2 challenge and that this protection was dependent on Fc-FcγR interaction, suggesting that Fc-effector functions improve the efficacy of REGN treatment80. Furthermore, McMahan et al. showed that, following the passive transfer of an IgG pool from rhesus macaques convalescing from SARS-CoV-2 infection to naïve macaques, IgG1 levels, neutralizing titers, ADCD and ADP were associated with protection against viral challenge81.

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody levels gradually decrease in the serum of patients, but both neutralizing antibody titers and robust specific memory B-cell responses are detected at 5 and 9 months PSO in patients who have had moderate and severe COVID-19, and they remain detectable at 1 year PSO, probably contributing to protection against reinfection14, 30, 39, 42, 82 (Fig. 3 ). During SARS-CoV-2 infection, the quality of antibody effector functions is correlated with their magnitude67, their specificity for RBD in both serum and nasal secretions6, 14, and with disease severity71. Different studies have shown that there is a dysfunction of NK cells in severe COVID-19 preventing the correct ADCC effect to occur40, 83. In patients with milder infections, as in women, NK-dependent ADCC activity is overrepresented relative to neutralization. The opposite situation is observed in patients with more severe disease and in men40, suggesting that antibody effector functions other than neutralization contribute to better protection. In particular, Witkowski et al. demonstrated that the uncontrolled TGF-β secretion by infected cells in severe patients, inhibits the expression of the integrin-β2 in NK cell surfaces making them unable to bind and kill infected cells83. Still, more studies are needed to decipher why there is an increase in TGF- β levels in severe COVID-19 patients and not in mild or asymptomatic patients.

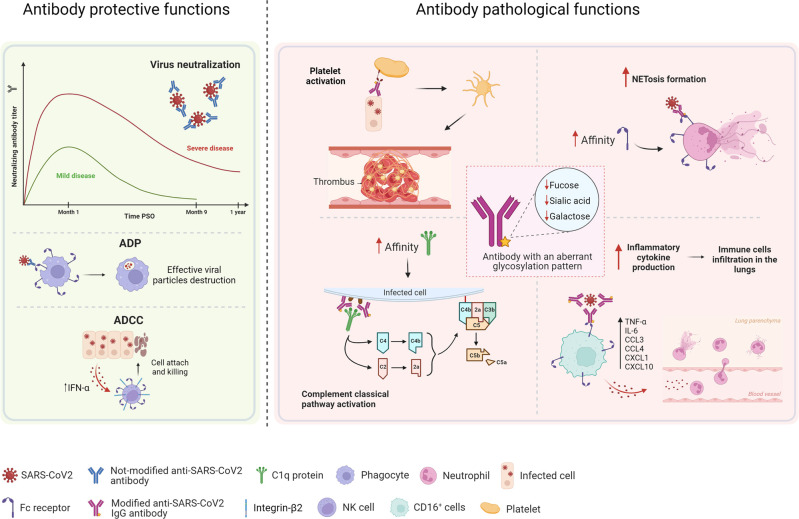

Fig. 3.

Protective and pathological functions of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies.

Anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies can exert protective functions, such as neutralization, antibody-dependent phagocytosis (ADP) and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC). Neutralizing antibody titers are higher in patients with severe disease than in those with mild disease patients, and these antibodies are detected until 1-year post-symptom onset (PSO); however, their levels decrease more rapidly in patients with mild disease. Serum from non-hospitalized patients and convalescent plasma from patients who have recovered display more Fc-dependent effector functions, such as ADP and ADCC, than serum from hospitalized patients. The pathological effects of antibodies in COVID-19 are related in part to aberrant glycosylation patterns, which are observed in the anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies of patients with severe, but not mild disease. These structural modifications can trigger inflammatory processes, such as cytokine production, immune cell infiltration into the lungs, or platelet-mediated thrombosis. These aberrant glycosylation patterns increase the affinity of antibodies for the C1q protein, thereby leading to activation of the classical complement pathway, and increases in affinity for FcγR enhance Fc-dependent functions, such as neutrophil extracellular trap formation (NETosis), which is associated with higher levels of inflammation. (Created with www.Biorender.com).

Lee et al. showed that convalescent patients presented a significant decline in plasma S-specific antibody-dependent ADCC and ADP activity over time, but that these responses remained detectable for longer than neutralization84, suggesting the involvement of a different antibody repertoire. Studies with RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies isolated from convalescent or infected patients (such as the S2H13, S2H14, S2X35, and S309), have shown that because of the different orientation of the complex spike-monoclonal antibody relative to the FcR, only S309 and S2H13 were capable to produce effective Fc-dependent functions16. Anti-S1 and anti-RBD specific antibodies from hospitalized COVID-19 patients elicit higher levels of antibody-dependent complement deposition (ADCD) and ADCC, but lower levels of ADP than antibodies from non-hospitalized and convalescent COVID-19 patients85, 86 (Fig. 3). In parallel, higher levels of ADCD are associated with higher levels of systemic inflammation, whereas higher levels of ADP are associated with milder systemic inflammation during COVID-1985. In addition, Adeniji et al. reported an absence of differences in anti-S or anti-RBD IgG antibody levels likely to account for the differences in ADCC or ADCD between hospitalized and non-hospitalized patients85. Overall, these data indicate that as far as SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies are concerned, it is quality rather than quantity that determines disease outcome.

Less is known about the Fc-effector functions of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in mucosal tissues, and most studies to date have focused on antibody neutralization capacity. Robust neutralization and ADP were detected in nasal washes from convalescent individuals who had experienced mild or severe disease67, 86. In COVID-19 patients, mucosal neutralization has been shown to be associated with nasal67, 72 and saliva-specific IgA31, and with RBD-specific IgM71. Anti-RBD IgA antibodies are more neutralizing than IgG in BAL, suggesting that IgA is more important for this function in the lung31. In addition, Butler et al. showed that depleting IgG antibodies from the nasal washes of convalescent patients decreased ADP but did not affect the neutralization of the virus. By contrast, IgA depletion decreased neutralization capacity without modifying ADP activity67. These observations provide support for the notion that IgA is a key factor in the neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the upper respiratory tract, as reported for other coronaviruses in human and animal models87, 88. In breast milk, anti-spike IgA titers and neutralization capacities are strongly positively correlated and are sustained for up to 10 months PSO89, 90, 91, which suggests that breastfeeding may protect newborns, consistent with observations that breastfed newborns rarely experience severe COVID-1992, 93.

Questions have been raised about the protective functions of antibodies in the face of the increasing number of variants during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Studies in both animal models and humans have shown that neutralizing antibodies elicited against one variant have a lower capacity to neutralize other variants. In a Syrian hamster model, Mohandas et al. showed that infection with the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant generated antibodies that were less effective for the neutralization of Alpha (B.1.1.7) strains and unable to neutralize the Beta (B.1.351) and Delta (B.1.617.2) strains94. Some studies in humans have also reported a lower capacity of convalescent plasma from the first wave of the pandemic to neutralize later SARS-CoV-2 variants, such as Beta (B.1.351) and Delta (B.1.617.2)34, 41, 86, 95, 96. This effect can be accounted for by the differences in spike mutations between variants. For example, Laurie et al. demonstrated that variants with mutations at the E484 position of the spike protein (such as Zeta (P.2), Iota (B.1.526), B.1.351, or B.1.617.2) were better neutralized by serum from E484K-exposed patients than other variants97. However, sequential boosters with different variants strengthen the neutralizing capacity of the antibodies elicited. In vitro studies showed that six monoclonal antibodies isolated from convalescent patients (2K146, S2X324, S2N28, S2X259, sotrovimab, and S2H97) cross-react and neutralize the Omicron variant as well as SARS-CoV virus98. Even though these antibodies target different epitopes, they are all highly conserved between viral variants98, indicating that a broader response can overcome antigenic shift. Accordingly, the Omicron variant is better neutralized in vitro by serum from convalescent vaccinated individuals, or from individuals inoculated with three doses of vaccine97, 98, 99. Similar observations have been reported for other viral infections, such as dengue, in which the cross-reactive antibodies elicited after a secondary heterologous infection have a higher avidity and protect against a third infection100.

Fc-effector functions are also modified by the presence of new variants. A recent study showed that serum from DG14G-infected patients displayed a smaller decrease in ADP, ADCC, ADCD and ADCT (antibody-dependent cellular trogocytosis) against the Beta and Delta patients than serum from Beta-infected patients. In addition, ADCD was the Fc-effector function most affected, consistent with an epitope-based Fc-dependent response101. The greater cross-reactivity of serum from Beta-infected individuals suggests that ADP, ADCC, ADCD and ADCT are less affected by variants. Mutations affecting the RBD and NTD regions targeted by ADCC were found to have no effect on this function, whereas they did alter neutralization, suggesting that Fc-dependent effector functions may make a greater contribution to decreasing the number of severe cases after infection with a variant than neutralization alone101. As demonstrated for other viruses, such as dengue and MERS, it is important to understand whether these antibodies can facilitate infections (ADE) under certain conditions or contribute to disease severity.

Antibodies in COVID-19 pathophysiology

Severe COVID-19 is characterized by dysregulation of the immune response, with the development of a cytokine storm responsible for rapid disease progression to ARDS and death is some patients. Several studies have reported an association between disease outcomes and dysregulation of the immune system, particularly in terms of the innate response102, 103. However, the intrinsic mechanisms of COVID-19 immune pathophysiology are not fully understood.

Neutrophils are the most abundant leukocytes and are often the first to respond to injury and infection104. They express the Fc alpha receptor (FcαRI/CD89) and can perform various effector functions, including ADP and neutrophil extracellular trap formation (NETosis)105, 106. In vitro studies have also shown that serum IgA antibodies are more potent than IgG for stimulating NETosis for many types of viral particles, including the SARS-CoV-2 virus107, 108 (Fig. 3). These studies also showed that NETosis could be potentiated by monomeric but not secretory IgA from saliva, suggesting that the secretory component may be involved in steric interference with binding to FcαRI108. These data suggest that NETosis may occur in tissues and in the vasculature, but probably not in the airways. The NETs in serum from patients suffering severe COVID-19 have a lower degradation capacity than those from asymptomatic patients and patients with mild symptoms109, suggesting that NETs may persist in the tissues for longer periods, resulting in local inflammation. Furthermore, plasmablasts from patients with severe disease, rapidly switch to the IgA2 isotype after stimulation with IL-21 and TGF-β110. This isotype has been shown to be associated with NETosis in patients with severe COVID-19111 or rheumatoid arthritis (RA)112. The IgA1 isotype is the most abundant IgA isotype in the blood of COVID-19 patients. No data are available concerning the levels of the IgA1 and IgA2 isotypes in mucosal secretions. The differences in glycosylation pattern between IgA1 and IgA2 may underlie the greater stimulation of NETosis by IgA2 than by IgA1112. IgA2 is less sialylated than IgA1, and the desialylation of IgA1 has also been reported to increase NETosis and IL-8 production by macrophages in vitro112. It remains unknown whether IgA1 glycosylation patterns are modified in COVID-19 patients, but these data are potentially important, to shed light on the pathological role of IgA isotypes associated with disease severity.

Another pathological effect of the immune response observed in some patients with severe COVID-19 is a small-vessel vasculitis driven by deposits of IgA-C3 immune complexes (ICs)113. IgA vasculitis, formerly known as Henoch–Schönlein purpura (HSP), has also been reported in children with COVID-19, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 infection may be a trigger114. SARS-CoV-2 may induce the secretion of cytokines, such as IL-6, affecting the glycosylation machinery and leading to the synthesis of galactose-deficient IgA1, which then forms IgA-ICs in blood115. Complement activation can result in protective effector functions and pathogen clearance. However, during SARS-CoV-2 infection, deposition of the complement components C4b and C3bc, and of the terminal complement complex (TCC) was restricted to anti-RBD IgG antibodies116. These deposits were correlated with both IgG levels and disease severity116. In addition, the IgG response to SARS-CoV-2 RBD after natural infection appears to be based on the IgG1 and IgG3 isotypes, which are the main ligands for C1q-mediated classical complement pathway activation40, 116. The aberrant immune responses produced during SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with severe disease may be explained by structural deficiencies in anti-SARS-CoV-2 specific antibodies (Fig. 3). Lower levels of galactosylation have been observed for all IgG subclasses in patients with severe disease, but not in convalescent patients or patients with mild disease, and the capacity of IgG to bind to FcyRs and C1q is positively correlated with disease severity117. Furthermore, ICs composed of the trimeric spike protein and afucosylated anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG isolated from COVID-19 patients induce the production of TNF-α, IL-6, CCL3, CCL4, CXCL1, and CXCL10 and robust neutrophil infiltration in the lungs of mice118. In vitro studies have shown that the ICs formed by the SARS-CoV-2 S protein and anti-S IgG antibodies enhance platelet-mediated thrombosis in a FcγRIIA-dependent manner, but only when the Fc domain of the anti-S IgG is modified to match the aberrant glycosylation pattern identified in patients with severe COVID-19119. Low levels of anti-S IgG fucosylation may return to normal within a few weeks of initial infection with SARS-CoV-2, indicating that higher levels of antibody-dependent inflammation occur principally at the time of seroconversion120. Nevertheless, early-phase S-specific IgG in the serum of patients with severe COVID-19 induces the production of IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF by human alveolar macrophages, which may then breach pulmonary endothelial barrier integrity and induce microvascular thrombosis in vitro120. But, can we transpose the observations made during infection to vaccination?

Humoral immune response to vaccination

In the face of the pandemic, a number of vaccines were developed very rapidly, with at least three rapidly approved in most countries121, 122. More than 11.3 billion doses have been administered worldwide to date123, with demonstrated efficacy against the various VOCs, including the Omicron variant. However, we will need a better understanding of the immunological fingerprint of these vaccines to improve vaccine design, and vaccination policies to increase protection against new variants. After full vaccination with BNT162b2 and CoronaVac, lower serum anti-spike and anti-RBD IgG concentrations and neutralization capacities have been shown to be associated with being male, older age, immunosuppression, and comorbid conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and autoimmunity124, 125, 126. However, after the second dose, a similar protective response is observed in individuals of all ages, highlighting the importance of booster doses for the elderly124, 127. Subsequent immunizations, whether natural (through infection) or by vaccination, can modulate the immune response to SARS-CoV-2. Following the second dose of BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273, individuals convalescing from COVID-19 develop higher titers of anti-spike IgG and IgA antibody titers with potent neutralization capacity in serum than individuals who have not had COVID-19125, 128, 129, 130. In addition, 5 months after the boost, memory antibodies from convalescent vaccinated patients have an improvement in neutralizing activity compared to 1-month post-boost, not been like this for naïve vaccinated individuals130. Several studies, including that by Wei et al.125, have shown that unvaccinated individuals with prior infections have lower anti-spike IgG titers than vaccinated individuals (with the BNT162b2 or ChadOx1 vaccine)131, but that they also require lower antibody concentrations to achieve the same level of protection125. Indeed, the better and broader response after vaccination in naïve individuals compared to infected patients has the basis in the formation of germinal centers (GCs)131, 132, 133, 134. While GCs in vaccinees are well formed and B and Tfh cells are greater stimulated, there is an impairment of GCs in patients with severe disease131. This suggests that protection depends on the mechanism of antibody generation and that the antibodies generated after infection and vaccination differ in quality.

One major unanswered question concerns the cross-protection against new variants conferred by vaccination. One dose of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine elicited a better neutralizing response to B.1, Gamma (P.1), and Delta (B.1.617.2) variants in seropositive than in seronegative individuals or non-vaccinated patients hospitalized for COVID-19135. The Moderna mRNA-1273 vaccine elicits a SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody response equivalent to that induced by natural infection, targeting wild-type virus and the Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta variants129. Individuals with pre-existing immunity vaccinated with mRNA-1273 had higher titers of IgG1 and IgA against all variants (WT, Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta) than fully vaccinated naïve individuals, indicating that hybrid infection/mRNA vaccine-induced immunity triggers cross-reactive antibody responses129. Furthermore, individuals infected with the Delta variant after BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccination were found to have higher anti-RBD IgG titers and higher viral neutralization capacities than vaccinated individuals without prior infection136, again suggesting that hybrid immunity triggers a robust anamnestic response, probably contributing to the lower risk of severe disease after vaccination. The vaccination of naïve individuals with three doses, or of previously infected individuals with two vaccine doses as a booster has been shown to enhance the anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune response and, thus, protection as shown by recent studies in which such strategies reduced the loss of neutralization function against various VOC, including Omicron97, 136, 137, 138, 139. In particular, this enhancement is due to an increase and evolution of RBD-137 and NTD-140 specific memory B cells, notably new clones that developed after the third dose targeting more conserved regions of the RBD137. Indeed, Kim et al. demonstrated that 6 months after vaccination, spike-specific memory B cells and long-lived bone marrow plasma cells had increased levels of somatic hypermutation, thus producing anti-spike antibodies with increased affinity and avidity as well as neutralization capacities132. Heterologous or multivalent boosting strategies may, therefore, be important for increasing protection against new variants, because the exposure to multiple spike variants expands the breadth of neutralization97, 136. We recently demonstrated this in a study in which serum from individuals with heterologous vaccination schedules (ChadOx1/BNT162b2) had stronger neutralizing activity than serum from individuals with homologous vaccination schedules (BNT162b2/ BNT162b2), regardless of the SARS-CoV-2 variant141. Furthermore, studies in vitro and in vivo with the monoclonal antibody S2P6, isolated from a convalescent patient, demonstrated that targeting highly conserved epitopes in the spike protein (stem helix in this case) is crucial for protection mediated by neutralization and Fc-effector functions142.

Importantly, mRNA vaccination against COVID generates structurally different antibodies, with effector functions different from those of the antibodies generated in response to natural infection, accounting for the efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for reducing the likelihood of severe disease. Vaccination induces more sialylated, fucosylated, and galactosylated antibodies, especially IgG1, than natural infection leading to severe disease117, 118. These structural modifications increase the ability of anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies to engage in FcyR pathways, which may serve as another mechanism for reducing infection, in addition to their Fab-mediated neutralization activity117. Kaplonek et al. showed that RBD-specific antibody depletion from vaccinated patients had little or no impact on Fc-dependent effector functions, such as ADCD or ADCP, against the Alpha, Beta, Gamma, and Delta variants. Furthermore, plasma from vaccinated individuals displayed high levels of C1q and C3d binding to spike-specific antibodies, or RBD-specific antibodies, unlike convalescent plasma143. This difference can be explained by the higher levels of IgG1 and IgG3 elicited by vaccination than by natural infection and by the fact that these isotypes have a higher potency for activating the complement cascade86, 117. Therefore, even if the spike mutations found on VOCs decrease vaccine efficacy by reducing neutralizing activity, Fc-dependent effector functions may also contribute to the lower incidence of severe disease after vaccination.

SARS-CoV-2 is a respiratory virus, and the induction of a mucosal immune response is, therefore, crucial to prevent infection. Specific antibody levels are not high in the mucosa, but such antibodies are nevertheless detected. Anti-spike and anti-RBD IgG levels in saliva are almost two orders of magnitude lower than those in serum. Anti-spike and anti-RBD IgA antibodies have also been detected at very low levels in the saliva, these levels peaking after the second dose of BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine144. Low levels of neutralizing antibodies have also been detected in saliva, nasal swabs, and nasopharyngeal lavages after mRNA vaccination69, 144. However, a stronger mucosal response has been measured locally in seropositive than in naïve vaccinated individuals69, 83, 145, suggesting that hybrid immunity effectively promotes and stimulates the anamnestic response in mucosal tissues. Nevertheless, anti-S1 sIgA antibodies with neutralizing capacity were present in the saliva at lower levels for a shorter time after BNT162b2 vaccination than after natural infection, possibly because the route of vaccine administration is different from the natural route of infection127, 146. Little is known about the functionality of the mucosal immune response against the various VOCs described to date, but cross-neutralization in the mucosa is expected to be much lower than that against the initial strain, in line with findings for the systemic immune response. Indeed, Garziano et al. reported a fourfold reduction in neutralization titers against the Delta variant in saliva from infected and vaccinated individuals147.

Antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) has been reported to facilitate infections with different viruses, including coronaviruses, such as MERS. Some studies have reported that, in subneutralizing concentrations, serum from convalescent COVID-19 patients can enhance SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro via the FcγR or C1q protein, suggesting that ADE may promote SARS-CoV-2 infection, particularly after vaccination or prior infection148, 149, 150. Others have suggested that neutralizing and enhancing antibodies recognize different epitopes151, 152, 153, 154. Liu et al. showed that monoclonal antibodies from COVID-19 patients targeting the NTD region in the spike protein enhanced SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro through conformational changes induced in the RBD by the antibody binding, facilitating the Spike-ACE2 interaction151. In addition, Lempp et al. demonstrated, using in vitro models, that monoclonal antibodies also directed against the NTD region or against a conserved site at the base of the RBD cannot inhibit viral infection in ACE2 overexpressing cells, however, they can block the lectin-facilitated infection154. On the contrary, monoclonal antibodies specific to the receptor-binding motif (RBM) effectively block ACE2-dependent infection but do not neutralize lectin-dependent infection promoting cell-to-cell fusion154. Serum from convalescent, but not vaccinated individuals can mediate FcγR-dependent virus uptake by monocytes in vitro without infectious viral particle production, but pyroptosis may be triggered, increasing inflammation and COVID-19 pathogenesis155. By contrast, other in vitro studies reported no ADE in convalescent sera, even though at subneutralizing concentrations156, 157. It has been suggested that ADE could contribute to SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro, but preclinical and clinical evidences suggest that this is not the case in vivo. Studies performed in vivo in macaques and mice have shown that antibodies directed against the RBD and NTD do not increase infection rates or disease severity153. Thus, even if ADE is sometimes reported in vitro, other Fc effector functions may make a positive contribution in vivo. Furthermore, vaccination/challenge studies in nonhuman primates revealed no increase in disease158, 159. In addition, the risk of severe disease is not higher in COVID-19 patients treated with convalescent plasma160, 161, 162, or in vaccinees. Moreover, even if new variants, such as Omicron, decrease the efficacy of the neutralizing antibodies elicited by vaccination, no enhancement of disease has yet been reported162, 163, 164.

In general, the intramuscular vaccines currently available reinforce systemic immune responses, but only weakly activate existing mucosal responses in previously infected individuals. This may account for the lack of sterilizing immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and subsequent infections even after vaccination. There is, therefore, an urgent need to improve the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine design to target the mucosal immune response more effectively.

Conclusions and perspectives

Many studies have demonstrated the protective function of the humoral immune response in COVID-19, and after vaccination. Neutralizing antibodies are known to protect against infections, but they are also associated with severe disease in COVID-19. After vaccination, neutralizing antibody titers are correlated with protection against severe disease in most cases, but infections occur due to poor activation of the specific mucosal immune response. Nevertheless, Fc-effector functions, such as ADCC, seem to contribute to protection even in the presence of new variants. However, if SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibodies have an aberrant glycosylation pattern, Fc-mediated protective functions are dysregulated, contributing to disease severity. The jury is still out as to whether the humoral immune system is “guilty” in the case of SARS-CoV-2 infection, but it appears to be a matter of balance, and additional studies are required to shed light on the factors influencing this dual role of antibodies in COVID-19. A full understanding of the humoral immune response to SAR-CoV-2 will be a major asset in the face of possible future coronavirus pandemics.

Despite all the progress made, many questions about the humoral immune response to SARS-CoV-2 remain unanswered. What are the intrinsic factors influencing the uncontrolled humoral immune response in some patients that lead them to develop the severe disease? IgG glycosylation modifications can hamper the immune response in COVID-19, but do IgA antibodies also have aberrant glycosylation patterns in severe disease patients that contribute to the pathophysiology of the disease? Anti-Spike antibodies are the most likely marker of correlates of protection in SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, the presence of viral variants with different neutralization sensitivities, differences in vaccine formulations, and the fact that antibodies alone cannot fully explain immune protection let a question open: what constitutes an immune correlate of protection for SARS-CoV-2 infection? If we want to get to a sterilizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2, next-generation vaccines should target the mucosal immune response and should include more conservative epitopes that cover a broader spectrum of SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Author contributions

M.Y.N., T.B., and S.P. analyzed the data. M.Y.N., T.B., and S.P. wrote the paper. All the authors approved the final version of the paper.

Funding

This work was funded by the MENRT, ANR, and MSD.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Publisher's note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gorbalenya AE, et al. The species Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus: classifying 2019-nCoV and naming it SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:536–544. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-0695-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard | WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard With Vaccination Data. https://covid19.who.int/. (2022).

- 3.Grasselli G, et al. Baseline characteristics and outcomes of 1591 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to ICUs of the Lombardy Region, Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1574. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5394. 7136855, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXovVSrur4%3D, 32250385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coutard, B. et al. The spike glycoprotein of the new coronavirus 2019-nCoV contains a furin-like cleavage site absent in CoV of the same clade. Antiviral Res.176, 104742 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Guy B, et al. Evaluation by flow cytometry of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE) of dengue infection by sera from Thai children immunized with a live-attenuated tetravalent dengue vaccine. Vaccine. 2004;22:3563–3574. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.03.042. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BD2cXmsl2jsLg%3D, 15315835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith N, et al. Distinct systemic and mucosal immune responses during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2021;22:1428–1439. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-01028-7. 8553615, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXhvFegsbnO, 34471264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pisanic, N. et al. COVID-19 serology at population scale: SARS-CoV-2-specific antibody responses in saliva. J. Clin. Microbiol.59, e02204-20 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Ye X, et al. Serum IgG anti-SARS-CoV-2 binding antibody level is strongly associated with IgA and functional antibody levels in adults infected with SARS-CoV-2. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:693462. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.693462. 8531527, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXis1ylsLbL, 34691016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zervou, F. N. et al. SARS-CoV-2 antibodies: IgA correlates with severity of disease in early COVID-19 infection. J. Med. Virol. 10.1002/jmv.2705 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Legros, V. et al. A longitudinal study of SARS-CoV-2-infected patients reveals a high correlation between neutralizing antibodies and COVID-19 severity. Cell. Mol. Immunol.18, 318–327 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Hartog, G. den et al. Persistence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in relation to symptoms in a nationwide prospective study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/cid/ciab172 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Havervall, S. et al. SARS-CoV-2 induces a durable and antigen specific humoral immunity after asymptomatic to mild COVID-19 infection. PLoS ONE17, e0262169 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Al-Mughales, J. A., Al-Mughales, T. J. & Saadah, O. I. Monitoring specific IgM and IgG production among severe COVID-19 patients using qualitative and quantitative immunodiagnostic assays: a retrospective cohort study. Front. Immunol.12, 705441 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Wu, J. et al. Occurrence of COVID-19 symptoms during SARS-CoV-2 infection defines waning of humoral immunity. Front. Immunol.12, 722027 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Sasson, J. M. et al. Diverse humoral immune responses in younger and older adult COVID-19 patients. mBio12, e0122921 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Piccoli L, et al. Mapping neutralizing and immunodominant sites on the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain by structure-guided high-resolution serology. Cell. 2020;183:1024–1042.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.037. 7494283, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXhvFKjs7nF, 32991844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tang, G. et al. The dynamic immunological parameter landscape in coronavirus disease 2019 patients with different outcomes. Front. Immunol.12, 697622 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Kopanja, S. et al. Characterization of the antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 in a mildly affected pediatric population. Pediatr. Allergy. Immunol. 33, e13737 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Konik, M. et al. Long-term SARS-CoV-2 specific immunity is affected by the severity of initial COVID-19 and patient age. J. Clin. Med. 10, 4606 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Patel SK, Velkoska E, Burrell LM. Emerging markers in cardiovascular disease: where does angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 fit in? Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2013;40:551–559. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12069. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC3sXhtFOisbfN, 23432153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacobsen, H. & Klein, S. L. Sex differences in immunity to viral infections. Front. Immunol. 12, 720952 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Weisberg SP, et al. Distinct antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in children and adults across the COVID-19 clinical spectrum. Nat. Immunol. 2021;22:25–31. doi: 10.1038/s41590-020-00826-9. 33154590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh AK, et al. Prevalence of co-morbidities and their association with mortality in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes, Obes. Metab. 2020;22:1915–1924. doi: 10.1111/dom.14124. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXhvVWhs73L, 32573903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shaw AC, Joshi S, Greenwood H, Panda A, Lord JM. Aging of the innate immune system. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2010;22:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.05.003. 4034446, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC3cXhtVersbjI, 20667703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Parini P, Giuliani C, Santoro A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018;14:576–590. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0059-4. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC1cXhtl2gtL7N, 30046148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carsetti R, et al. The immune system of children: the key to understanding SARS-CoV-2 susceptibility? Lancet Child Adolesc. Health. 2020;4:414. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30135-8. 7202830, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXhtVelsLjL, 32458804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imai K, et al. Cross-reactive humoral immune responses against seasonal human coronaviruses in COVID-19 patients with different disease severities. Int J. Infect. Dis. 2021;111:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.026. 8364517, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXitVSrurfI, 34407480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandberg, J. T. et al. SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral and cellular immunity persists through 9 months irrespective of COVID-19 severity at hospitalisation. Clin. Transl. Immunol.10, e1306 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Kurano, M. et al. Response kinetics of different classes of antibodies to SARS-CoV2 infection in the Japanese population: the IgA and IgG titers increased earlier than the IgM titers. Int. Immunopharmacol. 103, 108491 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Shi, D. et al. Dynamic characteristic analysis of antibodies in patients with COVID-19: a 13-month study. Front. Immunol.12, 708184 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Sterlin, D. et al. IgA dominates the early neutralizing antibody response to SARS-CoV-2. Sci. Transl. Med.13, eabd2223 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Wang Z, et al. Enhanced SARS-CoV-2 neutralization by dimeric IgA. Sci. Transl. Med. 2020;13:eabf1555. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf1555. 7857415, 33288661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gaebler C, et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2021;591:639–644. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03207-w. 8221082, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXjslKgtbY%3D, 33461210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravichandran, S. et al. Systemic and mucosal immune profiling in asymptomatic and symptomatic SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals reveal unlinked immune signatures. Sci. Adv. 7, eabi6533 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Slezak J, et al. Rate and severity of suspected SARS-Cov-2 reinfection in a cohort of PCR-positive COVID-19 patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021;27:1860.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.07.030. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXhvVKgtLnO, 34419576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen CH, Michlmayr D, Gubbels SM, Mølbak K, Ethelberg S. Assessment of protection against reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 among 4 million PCR-tested individuals in Denmark in 2020: a population-level observational study. Lancet. 2021;397:1204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00575-4. 7969130, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXntFOnsrg%3D, 33743221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isa MB, et al. Comparison of immunoglobulin G subclass profiles induced by measles virus in vaccinated and naturally infected individuals. Clin. Diagn. Lab Immunol. 2002;9:693–697. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.9.3.693-697.2002. 119984, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BD38XksVGisL4%3D, 11986279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cervia C, et al. Systemic and mucosal antibody responses specific to SARS-CoV-2 during mild versus severe COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021;147:545–557.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.10.040. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXisFemsLnK, 33221383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang, Z. et al. The potential role of an aberrant mucosal immune response to SARS-CoV-2 in the pathogenesis of IgA nephropathy. Pathogens10, 881 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Fuentes-Villalobos, F. et al. Sustained antibody-dependent NK cell functions in mild COVID-19 outpatients during convalescence. Front. Immunol. 13, 796481 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Noh, J. Y. et al. Duration of humoral immunity and cross-neutralizing activity against the Alpha, Beta, and Delta variants after wild-type SARS-CoV-2 infection: a prospective cohort study. J. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/INFDIS/JIAC050 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.H, A. et al. Persisting salivary IgG against SARS-CoV-2 at 9 months after mild COVID-19: a complementary approach to population surveys. J. Infect. Dis. 224, 407–414 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Scheiblauer H, et al. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 for more than one year—kinetics and persistence of detection are predominantly determined by avidity progression and test design. J. Clin. Virol. 2022;146:105052. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.105052. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXislKjs7nE, 34920374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suthar, M. S. et al. Rapid Generation of Neutralizing Antibody Responses in COVID-19 Patients. Cell Rep. Med.1, 100040 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Chen, Y. et al. A comprehensive, longitudinal analysis of humoral responses specific to four recombinant antigens of SARS-CoV-2 in severe and non-severe COVID-19 patients. PLoS Pathog.16, e1008796 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Ni L, et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2-specific humoral and cellular immunity in COVID-19 convalescent individuals. Immunity. 2020;52:971. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.04.023. 7196424, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXptlCjtb4%3D, 32413330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavacini LA, Kuhrt D, Duval M, Mayer K, Posner MR. Binding and neutralization activity of human IgG1 and IgG3 from serum of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses. 2003;19:785–792. doi: 10.1089/088922203769232584. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BD3sXnsF2lsbk%3D, 14585209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frasca, D. et al. Effects of age on H1N1-specific serum IgG1 and IgG3 levels evaluated during the 2011-2012 influenza vaccine season. Immun. Ageing10, 14 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Lamers MM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 productively infects human gut enterocytes. Science. 2020;369:50–54. doi: 10.1126/science.abc1669. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXhtlCmt7jO, 32358202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woudenberg, T. et al. Humoral immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal coronaviruses in children and adults in north-eastern France. EBioMedicine70, 103495 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Ortega, N. et al. Seven-month kinetics of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies and role of pre-existing antibodies to human coronaviruses. Nat. Commun.12, 4740 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Greenbaum, U. et al. High levels of common cold coronavirus antibodies in convalescent plasma are associated with improved survival in COVID-19 patients. Front. Immunol.12, 675679 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Dugas M, et al. Lack of antibodies against seasonal coronavirus OC43 nucleocapsid protein identifies patients at risk of critical COVID-19. J. Clin. Virol. 2021;139:104847. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2021.104847. 8065244, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXhtVOqs7fL, 33965698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dugas M, et al. Less severe course of COVID-19 is associated with elevated levels of antibodies against seasonal human coronaviruses OC43 and HKU1 (HCoV OC43, HCoV HKU1) Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;105:304–306. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.085. 7901274, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXntFOhtLg%3D, 33636357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sermet-Gaudelus, I. et al. Prior infection by seasonal coronaviruses, as assessed by serology, does not prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and disease in children, France, April to June 2020. Euro Surveill.26, 2001782 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Ringlander J, et al. Incidence and severity of Covid-19 in patients with and without previously verified infections with common cold coronaviruses. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;223:1831–1832. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab089. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXhtlWlurnL, 33780548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miyara, M. et al. Pre-COVID-19 immunity to common cold human coronaviruses induces a recall-type IgG Response to SARS-CoV-2 antigens without cross-neutralisation. Front. Immunol. 13, 790334 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Tamminen K, Salminen M, Blazevic V. Seroprevalence and SARS-CoV-2 cross-reactivity of endemic coronavirus OC43 and 229E antibodies in Finnish children and adults. Clin. Immunol. 2021;229:108782. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2021.108782. 8188772, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXhtlWjtLvL, 34118402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dijkman R, et al. Human coronavirus NL63 and 229E seroconversion in children. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:2368–2373. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00533-08. 2446899, 18495857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Friedman N, et al. Human coronavirus infections in israel: epidemiology, clinical symptoms and summer seasonality of HCoV-HKU1. Viruses. 2018;10:515. doi: 10.3390/v10100515. 6213580, 30241410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Castagnoli R, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in children and adolescents: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174:882–889. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1467. 32320004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu R, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. 7159086, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXhvFOmsLY%3D, 32007145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Renk, H. et al. Robust and durable serological response following pediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Commun.13, 128 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Fröberg, J. et al. SARS-CoV-2 mucosal antibody development and persistence and their relation to viral load and COVID-19 symptoms. Nat. Commun.12, 5621 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Isho, B. et al. Persistence of serum and saliva antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike antigens in COVID-19 patients. Sci. Immunol. 5, eabe5511 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Santos J, et al. In nasal mucosal secretions, distinct IFN and IgA responses are found in severe and mild SARS-CoV-2 infection. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:403. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.595343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Butler, S. E. et al. Distinct features and functions of systemic and mucosal humoral immunity among SARS-CoV-2 convalescent individuals. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.618685. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Vu DL, et al. Longitudinal analysis of inflammatory response to SARS-CoV-2 in the upper respiratory tract reveals an association with viral load, independent of symptoms. J. Clin. Immunol. 2021;41:1723–1732. doi: 10.1007/s10875-021-01134-z. 8476983, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXitFGhsr%2FP, 34581925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cagigi, A. et al. Airway antibodies emerge according to COVID-19 severity and wane rapidly but reappear after SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. JCI Insight6, e151463 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Tang, J. et al. Systemic and lower respiratory tract immunity to SARS-CoV-2 omicron and variants in pediatric severe COVID-19 and Mis-C. Vaccines10, 270 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Wright, P. F. et al. Longitudinal systemic and mucosal immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/INFDIS/JIAC065 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Britton, G. J. et al. Limited intestinal inflammation despite diarrhea, fecal viral RNA and SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA in patients with acute COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 11 13308 (123AD). (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Burnett D. Immunoglobulins in the lung. Thorax. 1986;41:337–344. doi: 10.1136/thx.41.5.337. 1020623, 1:STN:280:DyaL28zhs1Grsg%3D%3D, 3750240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Stockley RA, Mistry M, Bradwell AR, Burnett D. A study of plasma proteins in the sol phase of sputum from patients with chronic bronchitis. Thorax. 1979;34:777–782. doi: 10.1136/thx.34.6.777. 471196, 1:STN:280:DyaL3c7mvFGrsA%3D%3D, 542918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Reynolds HY. Immunoglobulin G and its function in the human respiratory tract. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1988;63:161–174. doi: 10.1016/S0025-6196(12)64949-0. 1:STN:280:DyaL1c7itVCqsA%3D%3D, 3276975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shiakolas, A. R. et al. Cross-reactive coronavirus antibodies with diverse epitope specificities and Fc effector functions. Cell. Rep. Med.2, 100313 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Spencer, D. A. et al. Phagocytosis by an HIV antibody is associated with reduced viremia irrespective of enhanced complement lysis. Nat. Commun. 13, 662 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Tortorici MA, et al. Ultrapotent human antibodies protect against SARS-CoV-2 challenge via multiple mechanisms. Science. 2020;370:950. doi: 10.1126/science.abe3354. 7857395, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXisVWjt77P, 32972994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pinto D, et al. Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature. 2020;583:290–295. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2349-y. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXht1Cmu7bI, 32422645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yamin R, et al. Fc-engineered antibody therapeutics with improved anti-SARS-CoV-2 efficacy. Nature. 2021;599:465–470. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04017-w. 9038156, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXisVSntL%2FF, 34547765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McMahan K, et al. Correlates of protection against SARS-CoV-2 in Rhesus Macaques. Nature. 2021;590:630. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03041-6. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXht1Onu7c%3D, 33276369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bastug, A. et al. The changing dynamics of neutralizing antibody response within 10 months of SARS-CoV-2 infections. J. Med. Virol. 10.1002/JMV.27544 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Witkowski M, et al. Untimely TGFβ responses in COVID-19 limit antiviral functions of NK cells. Nature. 2021;600:295–301. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04142-6. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXisFyrt7nN, 34695836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lee, W. S. et al. Decay of Fc-dependent antibody functions after mild to moderate COVID-19. Cell. Rep. Med. 2, 100296 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Adeniji, O. S. et al. COVID-19 severity is associated with differential antibody Fc-mediated innate immune functions. 10.1128/MBIO (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Klingler, J. et al. Detection of antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 in plasma and saliva from vaccinated and infected individuals. Front. Immunol.12, 759688 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 87.Loa CC, et al. Specific mucosal IgA immunity in turkey poults infected with turkey coronavirus. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2002;88:57–64. doi: 10.1016/S0165-2427(02)00135-6. 7119794, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BD38XkslGgsb4%3D, 12088645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Du L, et al. Intranasal Vaccination of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Encoding Receptor-Binding Domain of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Spike Protein Induces Strong Mucosal Immune Responses and Provides Long-Term Protection against SARS-CoV Infection. J. Immunol. 2008;180:948–956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.948. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BD1cXhsVygsQ%3D%3D, 18178835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fox A, et al. The IgA in milk induced by SARS-CoV-2 infection is comprised of mainly secretory antibody that is neutralizing and highly durable over time. PLoS ONE. 2022;17:e0249723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249723. 8906612, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB38Xnt1WjsLs%3D, 35263323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pace RM, et al. Milk from women diagnosed with COVID-19 does not contain SARS-CoV-2 RNA but has persistent levels of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgA antibodies. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:1. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.801797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pace RM, et al. Characterization of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, antibodies, and neutralizing capacity in milk produced by women with COVID-19. mBio. 2021;12:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mBio.03192-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Perlman JM, Salvatore C. Coronavirus disease 2019 infection in newborns. Clin. Perinatol. 2022;49:73. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2021.11.005. 35210010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gupta P, et al. An observational study for appraisal of clinical outcome and risk of mother-to-child SARS-CoV-2 transmission in neonates provided the benefits of mothers' own milk. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022;181:513. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04206-9. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXhslOns77O, 34379196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Mohandas S, et al. Pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (R346K) variant in Syrian hamsters and its cross-neutralization with different variants of concern. eBioMedicine. 2022;79:103997. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.103997. 8993158, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB38XpsV2jtb4%3D, 35405385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pan T, et al. Significantly reduced abilities to cross-neutralize SARS-CoV-2 variants by sera from convalescent COVID-19 patients infected by Delta or early strains. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021;18:2560–2562. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00776-8. 8503867, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXit1WkurrM, 34635805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moyo-Gwete T, et al. Cross-reactive neutralizing antibody responses elicited by SARS-CoV-2 501Y.V2 (B.1.351) N. Engl. J. Med. 2021;384:2161–2163. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2104192. 33826816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Laurie, M. T. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant exposures elicit antibody responses with differential cross-neutralization of established and emerging strains including Delta and Omicron. J. Infect. Dis. 10.1093/INFDIS/JIAB635 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Cameroni E, et al. Broadly neutralizing antibodies overcome SARS-CoV-2 Omicron antigenic shift. Nature. 2021;602:664–670. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04386-2. 35016195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Schmidt F, et al. High genetic barrier to SARS-CoV-2 polyclonal neutralizing antibody escape. Nature. 2021;600:512. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04005-0. 9241107, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXisVSntLzM, 34544114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ngono AE, Shresta S. Immune response to dengue and Zika. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2018;36:279. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-042617-053142. 5910217, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC1cXht1Gks7o%3D, 29345964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Richardson, S. I. et al. SARS-CoV-2 Beta and Delta variants trigger Fc effector function with increased cross-reactivity. Cell. Rep. Med.3, 100510 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Wu, Y. et al. RNA-induced liquid phase separation of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid protein facilitates NF-κB hyper-activation and inflammation. Signal. Transduct Target Ther. 6, 167 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.Cugno, M. et al. Complement activation and endothelial perturbation parallel COVID-19 severity and activity. J. Autoimmun. 116, 102560 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 104.Kolaczkowska E, Kubes P. Neutrophil recruitment and function in health and inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013;13:159–175. doi: 10.1038/nri3399. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC3sXivFygtbo%3D, 23435331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Monteiro, R. C. & Winkel, J. G. J. Van De IgA Fc receptors. 21, 177–204, 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141011 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 106.Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophil extracellular traps in immunity and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2018;18:134–147. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.105. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC2sXhs1WqsrfI, 28990587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gimpel, A. K. et al. IgA complexes induce neutrophil extracellular trap formation more potently than IgG Complexes. Front. Immunol.12, 761816 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Stacey, H. D. et al. IgA potentiates NETosis in response to viral infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A.118, e2101497118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 109.Torres-Ruiz, J. et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to COVID-19 hyperinflammation and humoral autoimmunity. Cells10, 2545 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Ferreira-Gomes M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 in severe COVID-19 induces a TGF-β-dominated chronic immune response that does not target itself. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Staats LAN, et al. IgA2 antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 correlate with NET formation and fatal outcome in severely diseased COVID-19 patients. Cells. 2020;9:2676. doi: 10.3390/cells9122676. 7764693, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3MXnvVKjsL0%3D, 33322797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Steffen, U. et al. IgA subclasses have different effector functions associated with distinct glycosylation profiles. Nat. Commun.11, 120 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 113.Allez M, et al. COVID-19-related IgA vasculitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72:1952–1953. doi: 10.1002/art.41428. 7361577, 1:CAS:528:DC%2BB3cXit1eks77O, 32633104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wong K, et al. COVID-19 associated vasculitis: a systematic review of case reports and case series. Ann. Med. Surg. 2022;74:103249. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Suzuki H, et al. Cytokines Alter IgA1 O-Glycosylation by Dysregulating C1GalT1 and ST6GalNAc-II Enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:5330–5339. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.512277. 1:CAS:528:DC%2BC2cXivF2mu7s%3D, 24398680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]