Abstract

Background

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) causes severe respiratory illnesses in infants and older adults. Older adults are frequently hospitalized with RSV illness and may experience loss of function. This study evaluated longitudinal changes in function associated with RSV hospitalization in older adults.

Methods

Adults ≥60 years hospitalized with laboratory‐confirmed RSV were enrolled (N = 302). Demographics and comorbidities were collected. Functional status was assessed 2 weeks pre‐hospitalization by recall, at enrollment, hospital discharge and 2, 4, and 6 months post‐discharge using the Lawton–Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) (scale 0–8) and Barthel ADL Index (scale 0–100).

Results

RSV‐associated hospitalization resulted in acute functional loss. Median IADL (5 vs. 3, p < 0.0001) and ADL (90 vs. 70, p < 0.0001) scores decreased significantly from pre‐hospitalization to admission and remained decreased at discharge. There were no statistically significant differences between pre‐hospitalization and 2‐, 4‐, or 6‐month scores. However, 33% and 32% of subjects experienced decreased 6‐month IADL and ADL scores, respectively. Additionally, 14% required a higher level of care at discharge. When stratified by pre‐hospitalization living situation, 6‐month IADL scores declined significantly for those admitted from a skilled nursing facility (3 vs. 1, p = 0.001). In multivariate analysis, male sex and diabetes were associated with a 6‐month decline in ADL score of ≥10.

Conclusions

Older adults hospitalized with RSV demonstrate acute functional decline that may become prolonged. Pre‐hospitalization living situation may predict patient outcomes. Further study is needed with hospitalized age‐matched controls and refined measurement tools to better define the specific impact of RSV on function.

Keywords: activities of daily living, adults, functional status, respiratory syncytial virus

1. INTRODUCTION

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a frequent cause of respiratory tract infections, with severe illness seen primarily in infants and older adults. During the winter there are an estimated 700,000 to two million cases of RSV, 1 , 2 600,000 medically attended visits, 117,000 hospitalizations, 1 and 11,000–17,000 deaths in adults ≥60 years of age annually in the United States. 1 , 3 , 4 Although most widely recognized as a pediatric pathogen, 78% to 82% of all RSV‐associated deaths occur in persons ≥65 years of age. 3 , 4 In some years, RSV attack rates and associated hospitalizations can exceed those of influenza among older adults 1 and account for substantial proportions of hospitalizations for pneumonia, exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (CHF), and asthma. 2 , 3 , 5 , 6 In a recent report, we noted the incidence of hospitalization associated with RSV among patients 50–64 and ≥65 years of age was approximately five and 15 times higher, respectively, than patients 18–49 years of age with higher rates of RSV infection in middle‐aged and older adults with CHF, coronary artery disease (CAD), and COPD. 7 Similar to influenza, RSV infection has been linked to acute cardiovascular events. 8

In contrast to accumulating literature on functional decline following influenza infection and hospitalization, there are limited data on the long‐term impact of RSV‐associated hospitalization on the functional status of older persons. 9 , 10 , 11 Half of all new‐onset functional impairment in frail older adults is attributable to hospitalization for any cause and associated with increased risk of 30‐day all‐cause readmission and death. 12 , 13 Sustained post‐hospitalization functional decline is uncommon before 50 years of age, but the risk of decline increases with increasing age and may also be related to pre‐existing frailty and the presence of underlying comorbid conditions. 1 , 7 , 8

Thus, characterization of disease states, including infections, and risk factors associated with functional impairment following RSV‐associated hospitalization is important for prioritization of development of prevention strategies. We therefore evaluated immediate cognitive and functional impairment in hospitalized adults ≥60 years of age acutely infected with RSV and the long‐term changes in functional status after discharge.

2. METHODS

2.1. RSV surveillance

Surveillance for RSV infection in adults ≥18 years of age was conducted at three hospital systems: NewYork‐Presbyterian Hospital, Columbia University Irving Medical Center (NYP‐CUIMC) in New York City (NYC), the University of Rochester Medical Center, Strong Memorial Hospital (URMC), and Rochester Regional Health System, Rochester General Hospital (RGH) in Rochester, NY, during three winters (October 15, 2017, to March 27, 2020) as previously described. 7 Adults with acute respiratory illness (ARI) symptoms, or exacerbations of CHF, COPD, or asthma preceded by ARI symptoms in the past 14 days, were screened for RSV by RT‐PCR on admission as described. 7 The study was approved by the institutional review boards of each participating institution.

RSV‐positive patients ≥60 years of age without terminal underlying conditions or their legally authorized representative (LAR) were approached for consent to participate in a substudy assessing longitudinal change in functional status after RSV hospitalization. The selection of sites representing a densely populated major urban city (NYC) and a site with rural and suburban populations provided ethnic and racial diversity in the study population.

2.2. Data collection for functional status

Enrolled subjects were interviewed to ascertain functional status at pre‐specified time points: by recall in the 2 weeks prior to hospitalization (pre‐hospitalization), at admission, discharge and 2, 4, and 6 months following discharge. Functional status was assessed using four instruments: the Lawton–Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) Scale (range 0–8), the Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) Index (range 0–100), the MRC Breathlessness score (range 1–5), and the Mini‐Cog (described in detail below). For subjects for whom there was evidence of cognitive impairment, IADL, ADL, and MRC scores were assessed with the assistance of a family member. Presence of comorbid conditions was based on self‐report and electronic medical record review. Living situation was also collected at five time points and classified as one of three categories: (1) living at home independently (living in the community without services or assistance from family); (2) living in the community with assistance (from family or home health services) or in an assisted living facility; or (3) living in a skilled nursing or rehabilitation facility.

The Lawton–Brody IADL scale was developed to assess higher level complex activities necessary for living in the community. 14 Subjects are assessed on skills for shopping, cooking, and managing finances that can identify subtle cognitive or physical decline. A score of 0 indicates low function and 8 high function.

The Barthel Index (ADL) is an ordinal scale developed to measure improvement in patients with chronic disability while participating in rehabilitation. 15 It measures performance of activities of daily living functions and includes assessment of feeding, continence and toilet use, dressing, bathing, transfers, and mobility on level surfaces and stairs. 15 A score of 100 denotes complete independence.

The MRC scale comprises five statements that describe a range of respiratory disability from none (Grade 1) to almost complete incapacity (Grade 5). 16 The MRC score does not quantify breathlessness; rather, it quantifies disability associated with breathlessness.

Breathlessness is rated using five statements: (1) no breathlessness except with strenuous exercise; (2) short of breath when hurrying on the level or walk up a slight hill; (3) walks slower than most people on the level, stops after a mile or so, or stops after 15 min of walking at own pace; (4) stops for breath after walking about 100 yards or after a few minutes on level ground; and (5) too breathless to leave the house or breathless when undressing. 16

The Mini‐Cog test was developed as a screening tool for dementia in older adults. 17 A standardized Mini‐Cog assessment was performed at enrollment that included three steps: standardized three‐word registration and recall at 5 min and correctly drawing a complete clock face at a defined time. Subjects receive 1 point for each word recalled and 2 points for a correct clock and 0 points for inability or refusal to draw a correct clock. A score of <4 suggests possible cognitive impairment and the need for further assessment.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were summarized via counts and proportions and compared between the two sites using Fisher's exact test or chi square test. Median and interquartile ranges were used to describe continuous variables including functional status scores, with comparisons based on the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test. Subjects missing a pre‐hospitalization score were excluded from analysis. Univariate analysis was used to assess unadjusted changes in functional status from pre‐hospitalization to each specific time point.

A linear mixed model was used to account for repeatedly measured data and assess differences in the change in ADL and IADL scores from pre‐hospitalization to admission, discharge, and 2 and 4 months after discharge for subjects who were alive 6 months after RSV hospitalization versus those who had died within the 6 month study period. In this analysis, site was modeled as a random effect.

Finally, logistic regression was used to model categorical change in functional status from pre‐hospitalization to 2 months and pre‐hospitalization to 6 months, defined as a decline of 10 or more points in the ADL score or one or more points on the IADL score. A decline of 10 or more points in ADL score has been reported to be associated with clinically meaningful loss of function and 20 or more points with catastrophic disability. 11 Clinical covariates for the model were chosen a priori based on clinically significant risk factors for functional decline and factors with a significant change in functional score at 6 months in univariate analysis. These included age, sex, ICU admission, diabetes, dementia, or stroke and living situation prior to admission. Site was modeled as a random effect. SAS 9.4 was used for all analyses, with tests performed at the two‐sided 0.05 level.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

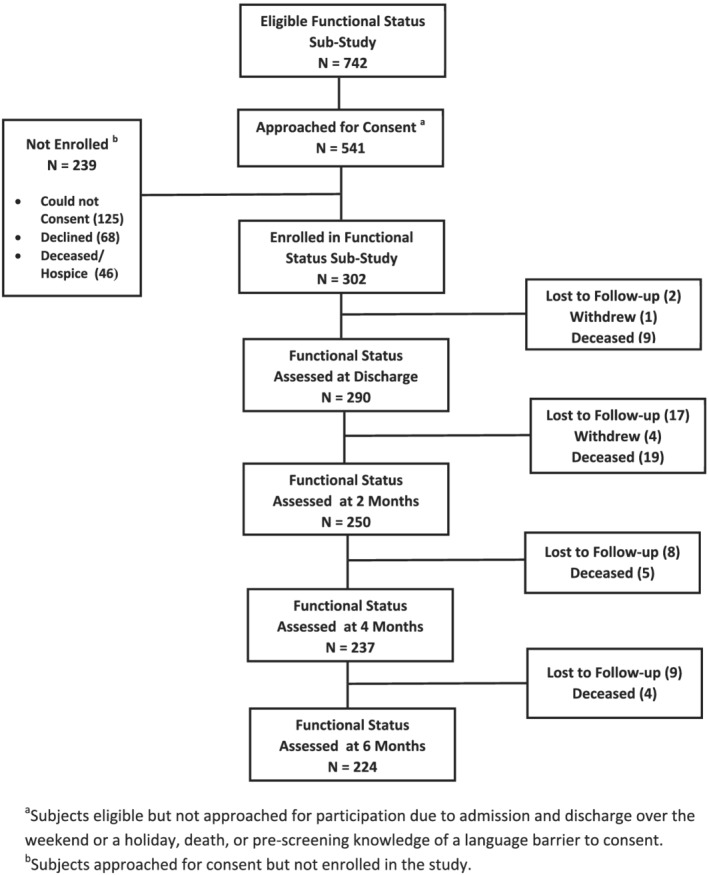

During the three winter seasons, 1099 RSV‐infected hospitalized patients were identified, of whom 742 were ≥60 years. In this substudy, 302 (56%) were consented to participate in the longitudinal follow‐up of functional status. Of these, 224 (74%) completed 6 months of follow‐up (Figure 1). Reasons for non‐enrollment included admissions on weekends and holidays or discharge before consent could be obtained, refusal, or inability to consent due to language or dementia without LAR available to provide consent. In a post hoc analysis of subjects ≥60 years enrolled in the functional status substudy (N = 302) compared with those not enrolled (N = 440), substudy participants were younger (74 [68,82] vs. 78 [68, 87], p < 0.001), more often White and non‐Hispanic and reported higher incidence of underlying chronic lung disease (58% vs. 47%, p = 0.003), cardiovascular disease (71% vs. 60%, p = 0.001), and diabetes (49% vs. 38%, p = 0.003). Those not enrolled in the substudy were more likely to require ICU admission (18% vs. 6%, p = 0.0001) and mechanical ventilation (11% vs. 1%, p = 0.001) and had a higher incidence of dementia (21% vs. 7%, p = 0.0001). However, mortality and hospital length of stay were similar between those in enrolled and not enrolled in the functional status substudy.

FIGURE 1.

Graphic display of enrollment strategy and results for the study population

The median age of subjects in the substudy was 74 years, 63% were female and 79% were White, with 21% identified as Black or African‐American and 23% as Hispanic or Latinx (Table 1). Most subjects were community dwelling prior to hospitalization, 40% of whom lived independently and 52% living with assistance of family or aides or in an assisted living facility. Notable differences were seen between subjects from Rochester, NY, versus subjects from NYC; the latter being less fully independent (50% vs. 24%, p = 0.0001) and more dependent on aides and family and having significantly lower pre‐hospitalization ADL and IADL scores (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the study population enrolled 2017–2020

|

All sites N = 302 |

Rochester, NY N = 187 |

New York City N = 115 |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups, n (%) | ||||

| Median age, years (IQR) | 74 (67, 82) | 73 (67, 80) | 75 (67, 85) | 0.08 |

| 60–74 years | 162 (54) | 109 (58) | 53 (46) | 0.11 |

| 75–89 years | 113 (37) | 64 (34) | 49 (43) | |

| ≥90 years | 27 (9) | 14 (8) | 13 (11) | |

| Female sex, n (%) | 190 (63) | 10 (59) | 80 (70) | 0.07 |

| Race, a n (%) | ||||

| White | 178 (79) | 150 (81) | 28 (68) | 0.09 |

| Black or African‐American | 47 (21) | 35 (19) | 12 (29) | 0.13 |

| Asian | 1 (0) | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.18 |

| Ethnicity, b n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latinx | 57 (23) | 10 (5) | 47 (72) | NA |

| Pre‐hospitalization living situation, c n (%) | ||||

| Living home independently | 122 (40) | 94 (50) | 28 (24) | 0.0001 |

| Community with assistance | 157 (52) | 80 (43) | 75 (65) | 0.0002 |

| Skilled nursing or rehabilitation | 24 (8) | 12 (7) | 12 (10) | 0.27 |

| Chronic comorbid conditions, n (%) | 296 (98) | 182 (97) | 114 (99) | 0.93 |

| No. of conditions, median (IQR) | 3 (2, 4) | 4 (3, 5) | 2 (2, 3) | 0.0001 |

| Chronic pulmonary conditions | ||||

| Any | 175 (58) | 115 (61) | 60 (52) | 0.11 |

| Asthma | 81 (27) | 48 (26) | 33 (29) | 0.59 |

| COPD | 101 (33) | 75 (40) | 26 (23) | 0.002 |

| Cardiovascular conditions | ||||

| Any | 215 (71) | 152 (81) | 63 (55) | 0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 100 (33) | 59 (32) | 41 (36) | 0.53 |

| Coronary artery disease | 90 (30) | 64 (34) | 26 (23) | 0.04 |

| Other conditions | ||||

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30) | 109 (36) | 77 (41) | 32 (28) | 0.02 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 149 (49) | 86 (46) | 63 (55) | 0.16 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 88 (29) | 53 (28) | 35 (30) | 0.70 |

| Chronic liver disease | 16 (5) | 15 (8) | 1 (1) | 0.007 |

| HIV positive | 5 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (2) | 1.0 |

| Cancer | 61 (20) | 50 (27) | 11 (10) | 0.0003 |

| Transplant recipient | 10 (3) | 5 (3) | 5 (4) | 0.51 |

| Dementia | 20 (7) | 3 (2) | 17 (15) | 0.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 39 (13) | 23 (12) | 16 (14) | 0.73 |

| Clinical findings on admission | ||||

| Pneumonia on chest radiograph | 116 (38) | 55 (29) | 61 (53) | 0.0001 |

| Fever ≥100.4°F on admission | 63 (21) | 35 (19) | 28 (24) | 0.56 |

| HR > 100 beats per minute | 108 (36) | 59 (32) | 49 (43) | 0.06 |

| RR > 20 breaths per minute | 146 (48) | 108 (58) | 38 (33) | 0.0001 |

| Systolic BP < 100 mmHg | 24 (8) | 22 (12) | 2 (2) | 0.0008 |

| Oxygen saturation ≤92% | 104 (34) | 84 (45) | 20 (17) | 0.0001 |

| Clinical outcomes, n (%) | ||||

| ICU admission | 18 (6) | 12 (6) | 6 (5) | 0.81 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 3 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0.29 |

| Length of stay, median (IQR) | 5 (3, 8) | 5 (3, 8) | 5 (4, 8) | 0.92 |

| Death in hospital | 10 (3) | 7 (2) | 3 (3) | 0.75 |

| 6‐month mortality d | 38 (13) | 28 (16) | 10 (9) | 0.08 |

| Pre‐hospitalization functional status, median (IQR) e | ||||

| Barthel score | 90 (70, 100) | 95 (80, 100) | 70 (49, 95) | <0.0001 |

| Lawton–Brody score | 5 (2, 8) | 6 (4, 8) | 2 (1, 5) | <0.0001 |

| MRC Breathlessness score | 2 (1, 4) | 2 (1, 4) | 4 (0, 5) | 0.09 |

| Mini‐Cognitive Assessment score | 3 (2, 5) | 4 (2, 5) | 3 (0, 3) | <0.0001 |

Data missing from two subjects in Rochester and 74 subjects in NYC.

Data missing from four subjects in Rochester and 50 subjects in NYC.

Data missing from one subject in Rochester.

Data missing from 15 subjects in Rochester.

Data missing from 31 subjects in NYC.

TABLE 2.

Median and IQR of functional scores from pre‐hospitalization to admission, discharge, and 2, 4, and 6 months after discharge

| Lawton–Brody IADL score (IQR) | Barthel ADL score (IQR) | MRC score (IQR) | Living independently, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐hospitalization (N = 271) | 5 (2, 8) | 90 (70100) | 2 (1, 4) | 122 (40%) |

| Admission a (N = 269) | 3 (1, 6) * | 70 (45, 95) * | 4 (2, 5) * | ‐ |

| Discharge b (N = 290) | 3 (1, 6) * | 85 (60, 100) | 3 (1, 5) | 79 (26%) * |

| 2 months c (N = 250) | 3 (1, 6) | 90 (70, 100) | 2 (1, 4) | 88 (32%) ** |

| 4 months d (N = 237) | 3 (1, 6) | 90 (66, 100) | 2 (1, 4) | 95 (35%) |

| 6 months e (N = 224) | 4 (2, 8) | 90 (65, 100) | 2 (1, 4) | 85 (32%) ** |

| Better f at 6 months, % | 23.6% | 36.6% | 37.7% | NA |

| Same f at 6 months, % | 44.6% | 30.9% | 38.2% | NA |

| Worse f at 6 months, % | 31.8% | 32.5% | 24.6% | NA |

Note: Analysis excludes patients who withdrew or were lost to follow‐up. MRC score ranges from 0–5 with higher score associated with increased breathlessness. Barthel ADL ranges from 0–100 and Lawton–Brody IADL from 0–8, with higher scores representing better function.

N = 269 for Barthel, L‐B, and MRC scores.

N = 225 for Barthel and L‐B, N = 224 MRC score.

N = 214 for Barthel, N = 215 L‐B, N = 213 MRC scores.

N = 209 for Barthel and L‐B, N = 207 for MRC scores.

N = 194 for Barthel and L‐B, N = 193 for MRC scores.

Comparison of subjects for whom paired pre‐hospitalization and 6‐month scores were available.

p < 0.01.

p ≤ 0.05.

The majority of subjects reported at least one comorbid condition pre‐hospitalization with a median of three conditions (Table 1). Chronic pulmonary diseases were identified in 58% including one third with COPD. Cardiovascular disease was present in 71% of subjects, one third having a diagnosis of CHF. Other commonly reported conditions included diabetes (49%), obesity (36%), chronic kidney disease (29%), and a history of cerebrovascular accident in 13%. Rochester subjects were more likely to have COPD, cardiac disease, obesity, and cancer, but less likely to have dementia than NYC subjects.

3.2. Clinical outcomes

The median length of stay for those in the functional status substudy was 5 days (IQR 3, 8). Approximately, one third of subjects were hypoxic at admission and demonstrated pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiograph (Table 1). At enrollment, the median Mini‐Cog score was 3 indicating an overall high frequency of acute or chronic cognitive impairment. Among those living independently prior to hospitalization, 41% had a Mini‐Cog score of ≤3. Few subjects enrolled in functional status required ICU admission (6%) or mechanical ventilation (1%), and in‐hospital all‐cause mortality was 3%. Significantly fewer patients were discharged to an independent living situation compared with the percentage living independently prior to admission (122 [40%] vs. 79 [26%], p = 0.0003) (Table 2). All‐cause mortality was 13% at 6 months post‐discharge.

3.3. Longitudinal functional status assessment

Pre‐hospitalization and admission functional status data were available for 90% and 89% of subjects, respectively. Longitudinal data were available for 96% at discharge, 83% at 2 months, 78% at 4 months and 74% at 6 months (Figure 1).

Acute decline in IADL, ADL, and MRC scores occurred in 62%, 50%, and 48% of participants, respectively. Median IADL score declined from 5 pre‐hospitalization to 3 at admission, ADL declined from 90 pre‐hospitalization to 70 at admission and MRC worsened from 2 pre‐hospitalization to 4 at admission (p < 0.0001 for each comparison). With the exception of the IADL score, functional scores improved from admission to discharge, although they remained lower than pre‐admission scores and 14% of subjects required a higher level of care at discharge (Table 2). Although there were no statistically significant differences between median pre‐hospitalization and 2‐, 4‐, or 6‐month functional scores, 8% of subjects reported ongoing loss of independence at 6 months. Additionally, hospitalization was associated with decreased IADL and ADL scores and worsening MRC score in 32%, 33%, and 24% of surviving subjects, respectively, at 6 months compared with their pre‐hospitalization baseline (Table 2).

When stratified by pre‐hospitalization living situation, IADL scores declined by 66% from pre‐hospitalization through 6 months for those living in a SNF prior to admission (median score 3 vs. 1, p = 0.001). ADL scores also declined by 36% from pre‐hospitalization to 6 months in this group (median 75 vs. 50, p = 0.056) (Figure 2). Subjects living in the community with assistance prior to admission also had a significant, but less dramatic 25% decline in IADL scores at 6 months (median 4 vs. 3, p = 0.04), with no change in median ADL scores at 6 months. Interestingly, subjects who were living completely independently prior to hospitalization had a slight improvement in both IADL (14% increase from 7 to 8) and ADL (5% increase).

FIGURE 2.

Change in functional status in adults ≥60 year of age at pre‐hospitalization and 2, 4, and 6 months after RSV hospitalization for (A) the Barthel Index of Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and (B) the Lawton Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily. Each panel shows data for baseline.

Finally, in the linear mixed model, the decline in ADL scores from pre‐hospitalization to admission were significantly greater in those who died compared with those who survived at 6 months (Table 3). After improving at discharge and at 2 months, the difference in ADL scores (delta) widened significantly at 4 months between survivors and those who died by 6 months. A similar trend was noted for changes in IADL scores pre‐hospitalization to admission, discharge, and 2 and 4 months among survivors versus those who died by 6 months (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of pre‐hospitalization functional scores in subjects alive versus deceased at 6 months after RSV hospitalization

|

Deceased at 6 months N = 38 |

Alive at 6 months N = 38 |

Difference | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ Score | SE | Δ Score | SE | |||

| Barthel Activities of Daily Living score | ||||||

| Admission | −24.09 | 3.26 | −15.47 | 1.31 | −8.62 | 0.01 |

| Discharge | −11.76 | 4.26 | −4.59 | 1.32 | −7.16 | 0.11 |

| 2 months | −6.58 | 5.41 | 0.14 | 1.31 | −6.72 | 0.23 |

| 4 months | −21.20 | 6.67 | −0.92 | 1.31 | −20.28 | 0.003 |

| Lawton–Brody Independent Activities of Daily Living score | ||||||

| Admission | −1.24 | 0.38 | −2.00 | 0.15 | 0.76 | 0.06 |

| Discharge | −1.60 | 0.42 | −1.81 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 0.62 |

| 2 months | −1.25 | 0.44 | −0.61 | 0.15 | −0.63 | 0.18 |

| 4 months | −1.86 | 0.47 | −0.69 | 0.15 | −1.17 | 0.02 |

3.4. Multivariate predictors of functional decline

In univariate analysis, there were no significant differences pre‐hospitalization baseline and 6‐month ADL or IADL scores based on clinical covariates including sex, hospital length of stay, ICU care or specific comorbid conditions. In an attempt to identify predictors of functional decline following hospitalization, we applied multivariate logistic regression to our data using demographic and clinical data as variables. No predictors were associated with a decrease in ADL score of ≥10 points from pre‐hospitalization to 2 months, but male sex and diabetes were independent predictors of a ≥10‐point decline at 6 months. No predictors were associated with a ≥1‐point change in IADL score at either 2 or 6 months after RSV hospitalization.

4. DISCUSSION

Most studies evaluating the burden of RSV in adults focus on hospitalization, respiratory failure, and mortality. Yet clinicians and caregivers of older adults understand that loss of independence is an equally important illness outcome. 18 Our 3‐year prospective study of older adults hospitalized with laboratory‐confirmed community acquired RSV infection allowed us to evaluate functional impairment and quantify this important long‐term sequela of RSV‐associated hospitalization. As expected, many patients reported acute changes in functional status upon hospital admission compared with their pre‐hospitalization baseline. However, even milder RSV illnesses may also acutely impact function in older adults. In a recent report by Curran et al of individuals ≥50 years of age diagnosed as outpatients with RSV, 83% and 60% reported declines in physical function and engagement in leisure activities, respectively, during illness. 19

Acute decline in functional status in older adults is not unique to RSV‐associated hospitalization and may be associated with other respiratory infections, such as influenza. 8 , 10 , 11 , 20 A less well‐studied and a potentially more important measure of the impact of RSV would be assessment of prolonged and/or sustained loss of function. In our study, IADL and ADL scores remained significantly decreased at hospital discharge and 14% of subjects required a higher level of care at discharge compared with their living situation prior to hospitalization. Although median IADL and ADL functional scores at 2, 4, and 6 months did not differ significantly from pre‐hospitalization scores for the group as a whole, one third of our subjects described a persistent decline in ADL and IADL functions at 6 months and importantly 8% reported loss of their previous independence. This is consistent with a prior study of 155 subjects hospitalized with either influenza or RSV that demonstrated persistent greater dependence on others to perform IADLs (27% to 33% for shopping, 31% to 41% for transportation, and 3% to 12% for handling medications) and a decrease in those living at home independently from 28% to 18%. 21

Reasons for our inability to measure a decline in the median scores for the entire group include the heterogeneity of our study population, regional differences between the two sites, and a wide range of pre‐hospitalization scores that were sometimes discordant between instruments. Interestingly, some individuals also reported an improvement in function following hospitalization. It is possible this counterintuitive finding represents inaccurate pre‐hospitalization recall of function by subjects. However, it may also indicate that the recognition and treatment of underlying conditions during hospitalization resulted in improved overall function. In a recent study of older Canadians hospitalized with influenza and other ARIs, 20.2% of those with influenza and 16.9% with other ARIs experienced acute functional decline on admission and 18.2% had persistent functional impairment at 30 days. 11 Similar to our findings, some patients showed an improvement in functional score at 3 months compared with pre‐hospitalization scores that was attributed to treatment of chronic conditions and utilization of healthcare resources like physical therapy and rehabilitation.

We selected measures that we believed would cover a range of activities of daily living, both basic (ADL—feeding, dressing, and toileting) and higher level instrumental (IADL—shopping, laundry, and cooking) activities. It is possible that the measures selected, or the manner in which they are scored (IADL), were not calibrated specifically to detect small changes that impact the ability to function independently. One strategy to overcome the inability of currently available instruments to measure subtle changes in function may be to stratify the analyses by important clinical or demographic cofactors. In our study, pre‐hospitalization living situation appeared to be an important correlate of functional decline. When we analyzed changes in functional scores from baseline to 6 months, stratified by pre‐hospitalization living situation, we noted a significant decline in IADL and ADL scores for subjects admitted from a SNF and a less profound but still significant decline in IADL in those living in the community with assistance. Importantly, we found no change in subjects living independently. In a study of nursing home residents with influenza reported by Barker et al, 25% of subjects with confirmed influenza infection had a decline in function 3–4 months after illness compared with a decline in 17% of matched control subjects (p = 0.04). 22 Further highlighting pre‐hospitalization living situation as an important predictor, we recently found that patients living in a SNF prior to a RSV‐associated hospitalization were 4.4 times more likely to have severe clinical outcomes (composite outcome: ICU care, mechanical ventilation, and death) compared with community‐dwelling adults. 23

Other demographic and clinical factors are likely predictive of functional decline. Acute functional impairment during RSV illness was greater in adults with underlying cardiopulmonary diseases than in otherwise healthy community‐dwelling adults ≥65 years. 1 In another study, persistent respiratory symptoms 3 months following an RSV‐related hospitalization were noted in patients with core risk factors (age ≥65; chronic heart, renal, obstructive pulmonary disease; asthma). 20 However, in our study, only male sex and diabetes were associated with persistent decline of ADL scores at 6 months, and interestingly, no predictors were significantly associated with decline in IADL scores.

Finally, in a comparison of survivors versus those who died within 6 months of RSV hospitalization, we noted a significantly greater decline ADL scores from pre‐hospitalization to admission among those who died. Though ADL scores for both groups improved at discharge and 2 months, at 4 months, the difference in ADL scores between those who died versus survivors again widened, suggesting that acute functional decline on admission may be a useful predictor of mortality post‐RSV hospitalization. In their study of influenza associated hospitalizations, Andrew et al found that acute functional decline from baseline to admission was independently associated with poor clinical outcomes including functional decline (decrease in ADL score of ≥10), catastrophic disability (decrease in ADL score of ≥20), and death. 11

Our study has several limitations. Our cohorts represent only RSV cases severe enough to warrant hospitalization, and we did not have a control group of adults hospitalized ARI from other causes to be able to specifically attribute the changes in functional status to RSV infection. Second, more than half of the subjects were either not approached for the functional status substudy or could not be enrolled for a variety of reasons which could introduce selection bias. However, in a post hoc analysis, it is not clear that differences noted between our study cohort and those not enrolled in the functional status substudy would change the findings. Third, the pre‐hospitalization functional scores were collected using subject or family recall and may have resulted in inaccuracy and no corrections were made for missing values at individual time points. Finally, no adjustments were made to account for any natural decline which may occur over a 6‐month period as a result of underlying frailty and chronic medical conditions in older adults, irrespective of hospitalization. In a study of older adults living in an SNF, the cumulative probability of functional impairment increased 12.8% at 6 months compared with baseline and 34.9%, 46.5%, and 56% at 12, 18, and 24 months, respectively. 24 However, predictors of decline in this population included cognitive impairment and incidence of hospitalization. Further study including granular longitudinal data on the rate of functional decline in community‐dwelling older adults is needed.

In conclusion, older adults hospitalized with RSV infection demonstrate significant acute functional decline and prolonged loss of function in some patients that may be prevented by the development of effective vaccines. Frailty, measured by pre‐hospitalization living situation, may be a predictor of long‐term morbidity and mortality. Further study is needed with age‐matched controls and refined measurement tools to better define RSV‐specific functional impact.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

LF and MP are employees of Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. LS served on an advisory board and serves on a data safety monitory board (DSMB) for Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA. ARB, LS, ARF, and EEW received grant funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA, to perform this work. ARB has research grants from Pfizer, Janssen, and CyanVac. EEW has research grants from Janssen and Pfizer and served on a DSMB sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline and advisory board for Gilead, Inc. ARF has research grants from Pfizer, Janssen, CyanVac, and BioFire Diagnostics and serves on the DSMB for Novavax.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lisa Saiman: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration. Edward E. Walsh: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; funding acquisition; investigation; methodology; project administration. Ann R Falsey: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration. Haomiao Jia: Formal analysis; methodology. Angela Barrett: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; project administration. Luis Alba: Formal analysis; methodology. Matthew Phillips: Formal analysis; methodology; project administration. Lynn Finelli: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; methodology; project administration.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/irv.13043.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge Raul Silverio, Grace Kuo, Mary Criddle, Maryanne Formica, Sharon Moorehead, and Michael Peasley for their contributions to this study and confirm they have provided written authorization. This study was presented in part at the RSVVW 2009 conference, November 12–14, 2019, Accra, Ghana. This research was funded by Merck &Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck& Co., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Branche AR, Saiman L, Walsh EE, et al. Change in functional status associated with respiratory syncytial virus infection in hospitalized older adults. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2022;16(6):1151‐1160. doi: 10.1111/irv.13043

Funding information

This research was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Funding information Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, Cox C, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high‐risk adults. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(17):1749‐1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McClure DL, Kieke BA, Sundaram ME, et al. Seasonal incidence of medically attended respiratory syncytial virus infection in a community cohort of adults >/=50 years old. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e102586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Matias G, Taylor R, Haguinet F, Schuck‐Paim C, Lustig R, Shinde V. Estimates of mortality attributable to influenza and RSV in the United States during 1997‐2009 by influenza type or subtype, age, cause of death, and risk status. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2014;8(5):507‐515. doi: 10.1111/irv.12258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thompson WW, Shay DK, Weintraub E, et al. Mortality associated with influenza and respiratory syncytial virus in the United States. Jama. 2003;289(2):179‐186. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.2.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Falsey AR, McElhaney JE, Beran J, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory viral infections in older adults with moderate to severe influenza‐like illness. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(12):1873‐1881. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Prasad N, Walker TA, Waite B, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus‐associated hospitalizations among adults with chronic medical conditions. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(1):e158‐e163. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Branche AR, Saiman L, Walsh EE, et al. Incidence of respiratory syncytial virus infection among hospitalized adults, 2017‐2020. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(6):1004‐1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ivey KS, Edwards KM, Talbot HK. Respiratory syncytial virus and associations with cardiovascular disease in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(14):1574‐1583. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Macias AE, McElhaney JE, Chaves SS, et al. The disease burden of influenza beyond respiratory illness. Vaccine. 2021;39(Suppl 1):A6‐A14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2020.09.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lees C, Godin J, McElhaney JE, et al. Frailty hinders recovery from influenza and acute respiratory illness in older adults. J Infect Dis. 2020;222(3):428‐437. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Andrew MK, MacDonald S, Godin J, et al. Persistent functional decline following hospitalization with influenza or acute respiratory illness. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69(3):696‐703. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chodos AH, Kushel MB, Greysen SR, et al. Hospitalization‐associated disability in adults admitted to a safety‐net hospital. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12):1765‐1772. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3395-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Greysen SR, Stijacic Cenzer I, Auerbach AD, Covinsky KE. Functional impairment and hospital readmission in Medicare seniors. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(4):559‐565. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self‐maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3 Part 1):179‐186. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61‐65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stenton C. The MRC breathlessness scale. Occup Med (Lond). 2008;58(3):226‐227. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqm162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The mini‐cog: a cognitive ‘vital signs’ measure for dementia screening in multi‐lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021‐1027. doi:10.1002/1099‐1166(200011)15:11<1021::AID‐GPS234>3.0.CO;2‐6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fried TR, Bradley EH, Towle VR, Allore H. Understanding the treatment preferences of seriously ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(14):1061‐1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Curran D, Cabrera ES, Bracke B, et al. Impact of respiratory syncytial virus disease on quality of life in adults aged >/=50 years: a qualitative patient experience cross‐sectional study. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2022;16(3):462‐473. doi: 10.1111/irv.12929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Falsey AR, Walsh EE, Osborne RH, et al. Comparative assessment of reported symptoms of influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and human metapneumovirus infection during hospitalization and post‐discharge assessed by Respiratory Intensity and Impact Questionnaire. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2022;16(1):79‐89. doi: 10.1111/irv.12903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Baker W, Falsey A, Walsh E. Functional decline in older patients hospitalized with cardiopulmonary disease associated with influenza A or respiratory syncytial virus. Int Congr Ser. 2004;1263:69‐72. doi: 10.1016/j.ics.2004.02.055 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Barker WH, Borisute H, Cox C. A study of the impact of influenza on the functional status of frail older people. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(6):645‐650. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goldman CR, Sieling WD, Alba LR, et al. Severe clinical outcomes among adults hospitalized with respiratory syncytial virus infections, New York City, 2017‐2019. Public Health Rep. 2021;137(5):929‐935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jerez‐Roig J, de Brito Macedo Ferreira LM, Torres de Araujo JR, Costa Lima K. Functional decline in nursing home residents: a prognostic study. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177353. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.