Abstract

The neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio(NLR) has been used for diagnosing venous thromboembolism (VTE). We aimed to assess the accuracy of NLR to diagnose VTE by meta-analysis. Systematic electronic searches were conducted June 2, 2021 in PubMed, Embase(Ovid), and Cochrane Library. The search did not have any language or time restriction applied. Our search strategy was based on keywords in combination with both medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and text words. The diagnostic odds ratio, summary receiver operating characteristics, sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, and negative likelihood ratio were estimated. 10 articles with 1513 VTE participants and 2593 control participants were included for quantitative synthesis. The pooled values were as follows: sensitivity = 0.68(95% CI 0.45-0.84), specificity = 0.73(95% CI 0.6-0.83), positive likelihood ratio = 2.5(95% CI 1.8-3.4), negative likelihood ratio = 0.44(95% CI 0.26-0.75), diagnostic odds ratio = 6(95% CI 3-11), and SROC = 0.76(95% CI: 0.73-0.8). NLR could be diagnostic factor for the detection of potential VTE, the accuracy thereof in the current meta-analysis exhibited moderate accuracy for diagnosing VTE. Furthermore, further large cohort studies are needed to determine optimal cut-off values of NLR.

Keywords: neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio, venous thromboembolism, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, meta-analysis

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) encompasses deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), it is the third most common cardiovascular disorder following coronary heart disease and stroke. 1 Despite the rapid development of medical and surgical treatment in recent years, VTE still poses a potential problem. It is mainly because of various clinical entities such as chronic venous insufficiency, phlegmasia cerulea dolens, venous gangrene, and pulmonary thromboembolism which all can have severe consequences. Therefore, VTE poses a high risk of mortality and long-term complications if not treated properly. 2 For these reasons, making an earlier, accurate diagnosis of VTE is vital to initiate prompt treatment and prevent mortality. However, diagnosis of VTE is often difficult, the earlier diagnosis of VTE remains a challenge for physicians due to the lack of symptoms’ accuracy. 3 Therefore, new markers to improve early recognition of VTE are required.

The mechanism of thrombus formation in the venous system has not yet been elucidated. It is well known that hereditary or acquired tendency to thrombosis, hypercoagulability, venous stasis, endothelial damage, and inflammation are the main factors which play a role in the etiopathogenesis of VTE. 4 Evidence suggests the involvement of inflammation not only in the pathophysiology of arterial thrombosis but also in VTE. 5 An established relation exists between inflammatory status and the prothrombotic state in the published data. 6 Inflammation may interfere with various stages of hemostasis, either through the activation of coagulation or through the inhibition of fibrinolysis and anticoagulant pathways. Many studies have shown inflammatory response plays an important role in the pathogenesis of VTE, with representative inflammation markers including the neutrophil lymphocyte ratio(NLR), platelet-lymphocyte ratio(PLR), and systemic immune-inflammatory index (SII).7, 8 Recently, the role of neutrophils in VTE has been demonstrated in many studies. Neutrophils are thought to mediate the pathogenesis of VTE. 9 The initiation of thrombus formation involves an inflammatory process which induces activation of endothelial cells, platelets, and leukocytes. 10 Activated endothelial cells express P-selectin, an adhesion molecule that mediates the attachment of leukocytes and platelets. Additionally, pro-inflammatory cytokines are secreted by the endothelium to recruit innate immune cells, particularly neutrophils and monocytes. Those cells, especially neutrophils, are abundantly found in early thrombi, forming clusters or layers adjacent to the endothelium.11, 12 Attachment of neutrophils to the endothelium is then followed by platelet adhesion. Finally, neutrophils may propagate thrombus formation through neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). 12 NETs are released as a response to cellular damage and inflammatory stimuli. Other function of NETs is to enhance coagulation by recruiting factor XIIa and cleave tissue factor pathway inhibitor, an inhibitor of coagulation. Additionally, binding of NETs to fibrin and von Willebrand Factor (VWF) leads to recruitment of platelets and red blood cells to the site of thrombus formation. 13 Therefore, neutrophils play an important role in the pathogenesis of VTE. NLR is readily available from routine laboratory studies and provides important information about systemic inflammation status, it is a non-specific inflammatory marker that represents the relationship between neutrophils and lymphocytes in inflammation. 14 Higher NLR indicates high neutrophil count and low lymphocyte count. The rise of neutrophil count represents a systemic inflammatory process while the decrease of lymphocytes shows ongoing stress inflicted by the disease. 14 Hence, a higher NLR may indicate VTE.

Some articles have reported that NLR has diagnostic values for VTE, but the results lack consistency. Moreover, most previous studies have been single-center investigations, with varying nature of cases, number of cases and study objectives, thereby making it difficult to reach consensus conclusions with good clinical guidelines. Hence, there is a need to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of NLR for VTE. In this meta-analysis, we analyzed the diagnosis accuracy of NLR for VTE.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the methodology described in the Preferred Reporting items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines 15 and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines. 2 A protocol was registered with PROSPERO, registration number CRD42022339154.

Literature Search

Systematic electronic searches were conducted June 2, 2021 in PubMed, Embase(Ovid), and Cochrane Library. The search did not have any language or time restriction applied. Our search strategy was based on keywords in combination with both medical subject headings (MeSH) terms and text words. The following search terms and search strategy were used: (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio OR neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio OR neutrophil lymphocyte ratio OR neutrophil/lymphocyte Ratio OR neutrophil-lymphocyte OR NLR) AND (“Pulmonary Embolism” OR “pulmonary thromboembolism*” OR “VTE” OR “DVT” OR “PE” OR “Pulmonary Embolism” OR “Thromboembolism” OR “thrombotic disease” OR “thromboembolic disease” OR “Thromboembolism” OR “venous thrombos*” OR “phlebothrombos*” OR “deep vein thrombos*” OR “deep venous thrombos*” OR “deep vein thrombos*” OR “deep venous thrombos*”OR “Venous Thrombosis”). Customised strategies for different databases were adapted where necessary. The reference lists of the included studies and relevant review articles were manually screened to identify other potential studies.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) articles were included that evaluated the accuracy of NLR for diagnosing VTE; (2) 2 × 2 contingency tables could be directly extracted or calculated from the articles. Studies were excluded if (1) case reports or series; (2) nonclinical trials; (3) animal experiments; (4) insufficient data or duplicate publication.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two authors (JJH and YDZ) independently screened abstracts and conducted full-text reviews to check the eligibility for inclusion, with disputes being resolved by obtaining consensus of a third independent author (ZBC). The following data were extracted from the included studies: author, year, country, baseline characteristics of the patients, sample size, level of NLR, and outcome indicators (sensitivity, specificity, true positive number (TP), false positive number (FP), false negative number (FN), true negative number (TN)). If TP, FP, FN, and TN were not reported, these data were calculated by sample size, sensitivity, and specificity. The Quality assessment included in the study was based on the QUADAS-2 scale. 16 Disagreement in study selection, data extraction, or quality assessment was solved by consensus or arbitration.

Statistical Analysis

All the analyses of enrolled articles were performed using RevMan 5.4(Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK), Meta-Disc software (Madrid, Spain) and Stata software version 12.0 (College Station, TX, USA). The TP, TN, FP, and FN rates were extracted from each study. The sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratio, negative likelihood ratio, and calculated diagnostic odds ratio along with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were summarized. Area under curve (AUC) of the summary receiver operating characteristic curve (SROC) was also calculated. For statistical analysis between sensitivity and specificity, Spearman correlation was applied. I2statistic was used to evaluate the heterogeneity among trials. I2> 50% indicated a considerable heterogeneity. Deeks’ funnel plot asymmetry analysis was performed to identify publication bias. Sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the stability of our analysis. Univariate meta-regression and subgroup analysis, and multiple regression were used to explore the potential sources of heterogeneity. P < 0.05 was considered the significant factor to induce heterogeneity.

Results

Study Characteristics and Quality Assessment

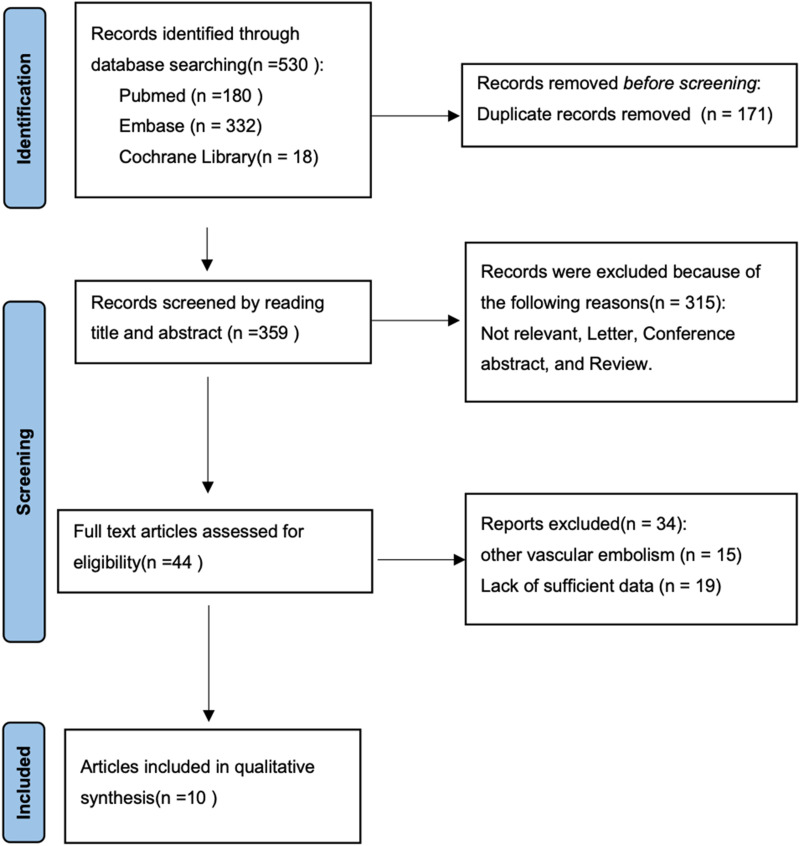

A schematic illustration of the literature search process and study selection is shown in Figure 1. We identified 530 records from the initial literature search. From these 530 studies, 171 duplicates were removed. 315 articles were excluded based on titles and abstracts primarily because these studies were irrelevant, letters, conference abstracts, and reviews. 34 articles were subsequently excluded based on full text because these studies were on other vascular embolisms and lack of sufficient data. Eventually, 10 articles with 1513 VTE participants and 2593 control participants were included for quantitative synthesis.17–26

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

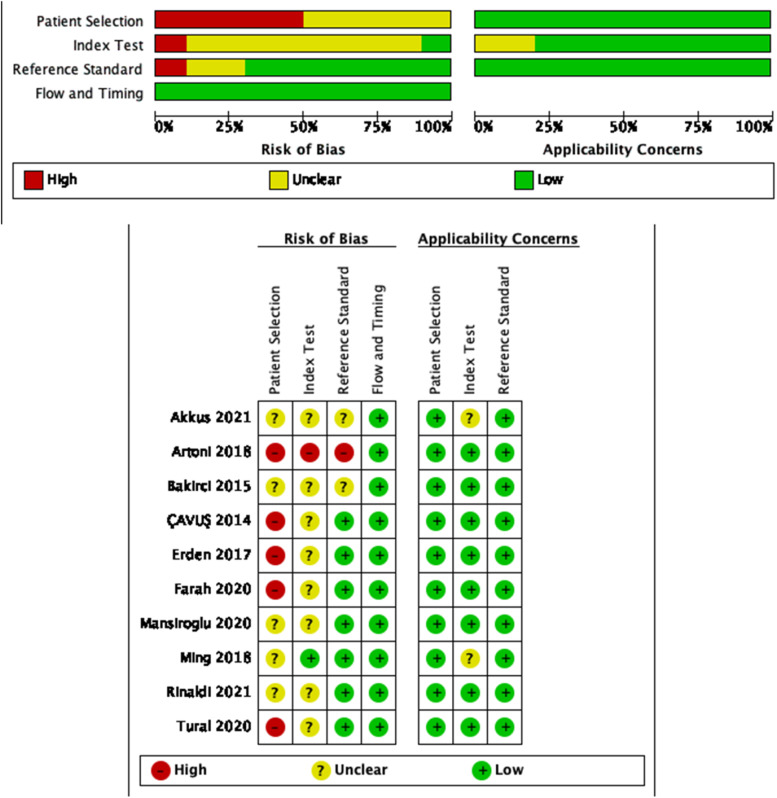

Table 1 and Table 2 illustrate the characteristics of included studies. All were retrospective case-control studies. A majority of studies were conducted in Turkey.17, 19–21, 23, 26 Among the included literature, PE,17, 20 DVT21, 23–26 and VTE18, 19, 22 were 2, 5, and 3, respectively. The cut-off value of NLR vary widely ranging from 1.76 to 5.3. We assessed the quality of each article and described it in a bar graph using the QUADAS-2 tool. The results of the quality assessment of individual studies are presented in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Included Studies.

| Study ID | Country | Type of embolism | Sample size | Age(Y) | NLR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case Control | Case Control | ||||

| Artoni 2018 | Italy | VTE | 486 299 | 47.9 (16.1)vs42.9 (12.9) | 1.8 (0.8)vs1.9(1.0) |

| Mansiroglu2020 | Turkey | DVT | 86 75 | 58(16)vs59(15) | 2.90(18.9–0.87)vs1.92(11.81–0.60) |

| Akkus2021 | Turkey | PE | 17 1435 | 66 (21:84)vs58 (18:94) | 5.14(1.89:31.05)vs2.65(0.16:52.03) |

| Bakirci2015 | Turkey | VTE | 77 34 | 53.7 (10.2)vs54.1(8.8) | 3.41(1.41)vs1.80(0.70) |

| Rinaldi2021 | Jakarta | DVT | 62 56 | 51.85(14.94)vs58.02(11.89) | 7.45(0.41-30.67)vs3.35(0.89–30.67) |

| Tural2020 | Turkey | DVT | 71 142 | 55.14(17.42)vs54.19(15.64) | 3.99(3.24)vs1.92(0.73) |

| Farah2020 | Israel | VTE | 272 55 | 62.7(18.9)vs55.4(15.1) | 5.3(5.3)vs3.1(1.9) |

| ÇAVUŞ2014 | Turkey | PE | 266 124 | 64.8(14.3)vs66.1(9.6) | 3.9(5)vs1.9(0.6) |

| Erden2017 | Turkey | DVT | 61 270 | 39.23(10.88)vs40.07(12.24) | 2.94 (0.9–26.96)vs1.78 (0.14–24.29) |

| Ming2018 | China | DVT | 115 105 | 52.17(14.13)vs49.45(11.81) | 3.03(1.56)vs1.72(0.58) |

PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thrombosis; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; NLR, neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio.

Table 2.

Occurrence of VTE in the Included Studies.

| Study id | Cutoff | TP | FP | TN | FN | SE(%) | SP(%) | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artoni 2018 | 3.6 | 17 | 469 | 284 | 15 | NR | NR | NR |

| Mansiroglu2020 | 1.975 | 48 | 38 | 51 | 24 | 56 | 68.7 | 0.611 (0.538–0.685) |

| Akkus2021 | 4.338 | 14 | 3 | 1093 | 342 | 82.4 | 76.2 | 0.792(0.699–0.884) |

| Bakirci2015 | 1.84 | 68 | 9 | 23 | 11 | 88.2 | 67.6 | 0.849(0.765–0.913) |

| Rinaldi2021 | 5.12 | 42 | 20 | 38 | 18 | 67.7 | 67.9 | 0.726(0.634–0.818) |

| Tural2020 | 1.9657 | 63 | 8 | 86 | 56 | 88.5 | 60.6 | 0.814(0.744–0.884) |

| Farah2020 | 5.3 | 188 | 84 | 31 | 24 | 69 | 57 | 0.67(0.6–0.75) |

| ÇAVUŞ2014 | 2.565 | 187 | 79 | 115 | 9 | 70.3 | 92.7 | 0.817(0.776–0.859) |

| Erden2017 | 2.12 | 44 | 17 | 180 | 90 | 72.1 | 67.7 | 0.739(0.658–0.820) |

| Ming2018 | 1.76 | 96 | 19 | 43 | 62 | 83.5 | 41 | 0.82(NR) |

NR, not reported; TP, true positives; FP, false positives; TN, true negatives; FN, false egatives; SE, sensitivity; SP, specificity; AUC, area under curve.

Figure 2.

Overall quality assessment of included studies (QUADAS-2 tool).

Diagnostic Value of NLR in VTE

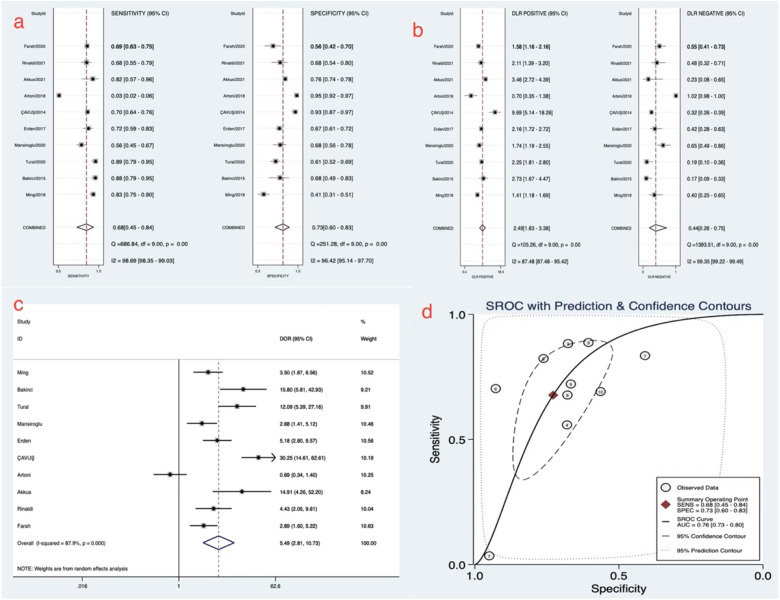

The pooled values were as follows: sensitivity = 0.68 (95% CI 0.45-0.84), specificity = 0.73 (95% CI 0.6-0.83), positive likelihood ratio = 2.5 (95% CI 1.8-3.4), negative likelihood ratio = 0.44 (95% CI 0.26-0.75), diagnostic odds ratio = 6 (95% CI 3-11), and SROC = 0.76 (95% CI: 0.73-0.8). These results indicated that NLR had moderate diagnostic accuracy for VTE. However, significant heterogeneity existed among the trials based on the sensitivity and specificity values (pooled I2 for sensitivity and specificity was 98.69% and 96.42%, respectively) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of NLR to diagnose venous thromboembolism.

(a) The pooled sensitivity and specificity. (b) The pooled positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio. (c) Forest plot of diagnostic odds ratio. (d) The summary receiver operating characteristic curve of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio in diagnosing venous thromboembolism.

Publication Bias and Univariate Meta-Regression and Subgroup Analysis

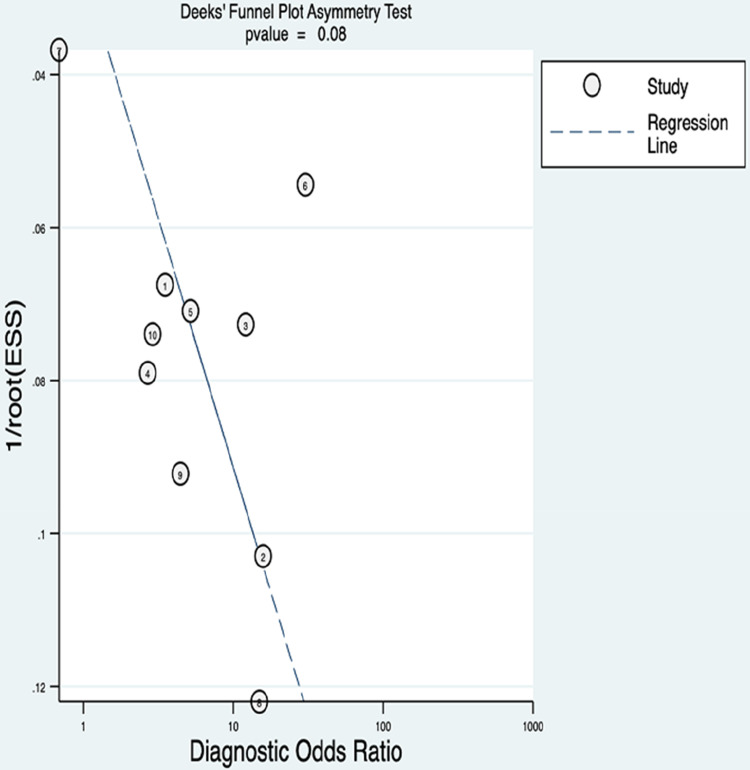

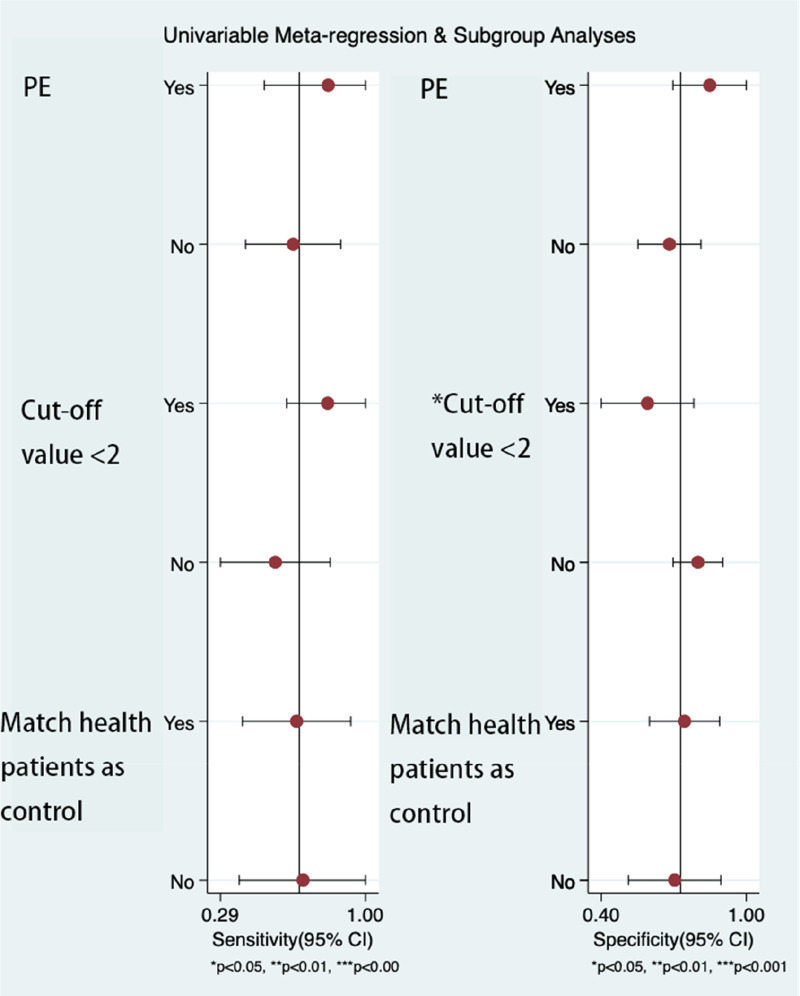

We used Deeks’ funnel plot asymmetry analysis, and subgroup analysis in our study. We found no publication bias among the studies (P = 0.08). Univariable meta-regression and subgroup analysis found that the cut-off value<2 was the source of heterogeneity. The sensitivity of the cut-off value<2 was 0.82(95% CI 0.62-1), and the specificity was 0.59 (95% CI 0.4-0.78). The sensitivity of the cut-off value>2 was 0.56(95% CI 0.29-0.83), and the specificity was 0.66 (95% CI 0.4-0.93). The results of univariate meta-regression analysis and subgroup analysis are shown in Figures 4–5 and Table 3.

Figure 4.

Deek's funnel plot asymmetry text of publication bias.

A statistical difference at P <0.05.

Figure 5.

Univariate meta-regression analysis and subgroup analysis in diagnosing venous thromboembolism.

Univariable meta-regression analysis for the sensitivity and specificity of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio for venous thromboembolism. PE, pulmonary embolism

Table 3.

Subgroup Analysis of the Association Between NLR and VTE.

| Study factors | subgroups | Study number | Sensitivity | I2(%) | Specificity | I2(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | Yes | 2 | 0.82(0.52–1.00) | - | 0.85(0.7–1.0) | - |

| No | 8 | 0.65(0.41–0.88) | 98.9 | 0.68(0.55–0.81) | 98.7 | |

| Cut-off value<2 | Yes | 4 | 0.82(0.62–1.0) | 92.2 | 0.59(0.4–0.78) | 82.6 |

| No | 6 | 0.56(0.29–0.83) | 99.1 | 0.66(0.40–0.93) | 98.4 | |

| Match health patients as control | Yes | 6 | 0.66(0.4–0.93) | 99.3 | 0.74(0.6–0.89) | 98.5 |

| No | 4 | 0.7(0.38–1) | 60.4 | 0.7(0.51--.90) | 88.6 |

PE, pulmonary embolism.

Multiple Regression and Exploration of Threshold Effect

Heterogeneity due to threshold was assessed by Spearman's correlation coefficient. The Spearman's correlation coefficient was 0.539(P = 0.108). To determine the sources of heterogeneity between studies, meta-regression using the following covariate: type of embolism is PE(yes and no), cut-off value<2(yes and no), and match health patients as the control group(yes and no) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Possible Sources of Heterogeneity of Multiple Regression.

| Study factors | coefficient | P | RDOR |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE | −2.036 | 0.0271 | 0.13(0.02–0.71) |

| Cut-off value<2 | 0.175 | 0.7812 | 1.19(0.26–5.51) |

| Match health patients as control | 0.193(0.34–4.29) | 0.7112 | 1.21(0.34–4.29) |

PE, pulmonary embolism.

Discussion

VTE poses a high risk of mortality and long-term complications if not treated properly. 2 However, diagnosis of VTE is often difficult, the earlier diagnosis of VTE remains a challenge for physicians due to the lack of symptoms’ accuracy. Therefore, new markers to improve early recognition of VTE are required. Inflammatory response plays an important role in the pathogenesis of VTE(4–6). NLR is a valuable inflammatory biomarker. It is readily available from routine laboratory studies and provides important information about systemic inflammation status. The results of our meta-analysis including 10 studies manifested that the pooled sensitivity, specificity, and SROC of NLR in the diagnosis of VTE were 0.68 (95% CI 0.45-0.84), 0.73 (95% CI 0.6-0.83), and 0.76 (95% CI: 0.73-0.8), respectively. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the prediction of NLR with VTE. NLR is non-diagnostic due to moderate diagnostic accuracy. However, NLR is also an inexpensive and readily available laboratory parameter which is easy to obtain in a clinical setting. It can help to improve the specificity of VTE detection. NLR can be considered useful as a diagnostic measure for patients with suspected VTE.

Nowadays, several blood biomarkers have been identified to predict VTE, such as D–dimer, CRP, and inflammation markers(NLR, PLR, and SII). Many articles have reported that NLR has both diagnostic and prognostic values for VTE. Kayrak et al performed a multivariate Cox regression analysis on 359 patients with acute PE and found that NLR was an independent predictor of 30-day mortality (HR = 1.03). 27 Liu et al found that a 1-unit increase in NLR related to a 17.1% increase in the probability of death in patients with acute PE. 28 Duman et al have shown that an NLR was predictive for 30-day, 6-month, and 1-year mortality in a cohort of 828 PE patients. 29 Siddiqui et al found VTE patients with higher baseline NLR values were at an increased risk of major bleeding or death. 30 In addition to predicting mortality, Jia et al found NLR was predictive of right ventricular dysfunction. 31 A previous meta-analysis including 1424 patients from 6 retrospective studies found high NLR has a sensitivity of 77% and a specificity of 74% in predicting short-term mortality. 32 Another meta-analysis including 2323 patients from 7 retrospective studies found NLR to independently predict the overall (short-term and long-term) mortality (OR 10.13) and short-term (in-hospital and 30 days) mortality(OR 8.43). 33

D-dimers are fragments of protein released into the circulation when a blood clot breaks down as a result of normal body processes or with use of prescribed fibrinolytic medication. As a sign of hypercoagulability, D-dimer has been clinically used to evaluate the risk of VTE generally. 34 The sensitivity of D-dimer for the diagnosis of VTE is sufficiently high for clinical practice. However, the specificity of D-dimer is low in clinical practice, as many pathophysiological(age, pregnancy, and cancer) processes may stimulate an increase in D-dimer. 35 Therefore, D-dimer is used routinely to exclude VTE. Rinaldi et al have compared the diagnostic power of NLR and D-dimer for predicting DVT. 25 In this study, NLR had higher sensitivity than D-dimer (65% vs 60%) in patients with a low probability of DVT. Furthermore, for patients with a high probability of DVT, NLR had higher specificity than D-dimer (69.2% vs 53.8%).

The association between the levels of CRP and the risk of developing VTE has been described. A meta-analysis published by Kunutsor et al showed that the pooled risk estimate for VTE per 5 mg/l increment in CRP levels was 1.23 (1.09–1.38). 36 Bakirci et al have compared the diagnostic power of NLR and CRP for predicting DVT. 19 In this study, NLR was found to have good diagnostic accuracy with AUC(0.849 vs 0.741) compared with CRP.

Several studies also evaluated the PLR as a diagnostic tool for acute VTE. The study of Akkus et al identified NLR and PLR as independent predictors of PE in 1452 COVID-19 patients. 17 In this study, NLR was found to have good diagnostic accuracy with AUC(0.792 vs 0.695) compared with PLR. Similarly, Tural et al found the same result(0.814 vs 0.621). On the contrary, Erden et al found that PLR has good diagnostic accuracy for VTE compared with NLR in Behcet's disease(0.831 vs 0.719). As for SII, Gok et al found that the optimal cutoff value of SII to predict a massive acute PE was 1161, with 91% sensitivity and 90% specificity (AUC 0.957). 37 It is also a powerful tool for predicting VTE.

We found considerable heterogeneity among the included articles. In the included study, Akkus and colleagues investigated the diagnostic value of NLR in PE in a COVID-19 population. 17 Similarly, Erden and colleagues explored the diagnostic value of NLR in DVT in Behcet's disease. 21 These two diseases may have some effect on NLR values. The NLR levels have been found significantly higher in COVID-19 38 and Behcet's disease. 39 In addition, COVID-19 and Behcet's disease asymptomatic VTE's are frequent events that may also be interfering with the results. Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis of 8 additional studies. The AUC was 0.76(95%CI 0.72–0.79). The sensitivity was 0.65 (95% CI 0.38-0.85), and the specificity was 0.73 (95% CI 0.56-0.85). The heterogeneity of sensitivity and specificity remained high, I2 = 98.66%, and 96.75%, respectively. Excluded these two studies had no significant effect on the meta-analysis. This is likely because, the control group of these two studies was the same disease, which reduced the influence of NLR on the diagnostic ability of VTE. Therefore, these two studies were not excluded from our study. To find the source of heterogeneity, we conducted publication bias, subgroup analysis and meta-regression. We found no publication bias in the included literature. However, in the subgroup analysis, we found that cut-off values were the source of heterogeneity. Currently, there is no clear cut-off value for the diagnosis of VTE. There was a wide variation in the cut-off values in the included literature, from 1.76 to 5.3. The sensitivity and specificity of diagnosis are different due to the difference in cut-off value. However, Spearman's correlation coefficient found no threshold effect. Therefore, further large cohort studies are needed to determine optimal cut-off values. Multiple meta-regression found type of embolism was the source of heterogeneity. Our meta-analysis included 2 articles with PE as the outcome, 5 articles with DVT as the outcome and 3 articles with DVT as the outcome. This may have swayed the reliability of the results to some degree.

This current meta-analysis had several limitations. Firstly, due to these studies belonging to retrospective research, a lack of prospective studies increased the bias risk of quality assessment in the patient selection and index test domains. Secondly, significant heterogeneities existed among included studies. In our study, univariable meta-regression and subgroup analysis found that the cut-off value<2 was the source of heterogeneity. However, we did not record the same evidence from multiple regression and threshold effect(P = 0.108). The cut-off value of NLR in all included studies for the detection of VTE was not set in advance, but the optimal threshold value was determined by the ROC curve. NLR is a laboratory metric with a high degree of variation, there was a wide variation in the cut-off values in the included literature. Inflammatory diseases such as COVID-19 and Behcet's disease may affect the results of NLR. However, after excludthese two studies, there is still remarkable heterogeneity. Thirdly, there are many risk factors for VTE, and we could not analyze the risk factors included in the literature.

Conclusion

In conclusion, NLR could be a diagnostic factor for the detection of potential VTE, the accuracy thereof in the current meta-analysis exhibited moderate accuracy for diagnosing VTE. Furthermore, further large cohort studies are needed to determine optimal cut-off values of NLR.

Acknowledgments

All the authors of the manuscript are immensely grateful to their respective universities and institutes for their technical assistance and valuable support in the completion of this research project.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: Conceptualization: Jingjing Hu.

Data curation: Jingjing Hu, Yidan Zhou.

Formal analysis: Jingjing Hu, Yidan Zhou.

Investigation: Jingjing Hu, Zhaobin Cai.

Methodology: Jingjing Hu, Zhaobin Cai.

Writing – original draft: Jingjing Hu.

Writing – review and editing: Zhaobin Cai.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Zhaobin Cai https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5637-5675

References

- 1.Spannagl M, Samama M-M, Oger E, et al. Venous thromboembolism (VTE) in Europe. Thromb Haemost. 2017;98(10):756-764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahn SR, Susan Solymoss M, Lamping DL, Abenhaim L. Long-term outcomes after deep vein thrombosis: postphlebitic syndrome and quality of life. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;15(6):425-429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Le Gal G, Righini M. Controversies in the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(Suppl 1):S259-S265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakai T, Inoue S, Matsuyama T, et al. Eosinophils may be involved in thrombus growth in acute coronary syndrome. Int Heart J. 2009;50(3):267-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roumen-Klappe EM, den Heijer M, van Uum SH, van der Ven-Jongekrijg J, van der Graaf F, Wollersheim H. Inflammatory response in the acute phase of deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35(4):701-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hess K, Grant PJ. Inflammation and thrombosis in diabetes. Thromb Haemost. 2011;105(Suppl 1):S43-S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kremers B, Wübbeke L, Mees B, Ten Cate H, Spronk H, Ten Cate-Hoek A. Plasma biomarkers to predict cardiovascular outcome in patients with peripheral artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40(9):2018-2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neupane R, Jin X, Sasaki T, Li X, Murohara T, Cheng XW. Immune disorder in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease- clinical implications of using circulating T-cell subsets as biomarkers. Circ J. 2019;83(7):1431-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moon MJ, McFadyen JD, Peter K. Caught at the scene of the crime: platelets and neutrophils are conspirators in thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2022;42(1):63-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branchford BR, Carpenter SL. The role of inflammation in venous thromboembolism. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phan T, Brailovsky Y, Fareed J, Hoppensteadt D, Iqbal O, Darki A. Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratios Predict All-Cause Mortality in Acute Pulmonary Embolism. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2020;26(3):1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borazan E, Balik AA, Bozdag Z, et al. Assessment of the relationship between neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and prognostic factors in non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Turk J Surg. 2017;33(3):185-189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cushman M. Epidemiology and risk factors for venous thrombosis. Semin Hematol. 2007;44(2):62-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeiler S, Stark K, Massberg S, Engelmann B. Propagation of thrombosis by neutrophils and extracellular nucleosome networks. Haematologica. 2017;102(2):206-213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8(5):336-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deek JJ. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):529-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akkus C, Yilmaz H, Duran R, Diker S, Celik S, Duran C. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios in those with pulmonary embolism in the course of coronavirus disease 2019. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2021;25(10):1133-1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Artoni A, Abbattista M, Bucciarelli P, et al. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio as risk factors for venous thrombosis. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2018;24(5):808-814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakirci EM, Topcu S, Kalkan K, et al. The role of the nonspecific inflammatory markers in determining the anatomic extent of venous thromboembolism. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2015;21(2):181-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ÇAvuŞ UY, Yildirim S, SÖNmez E, Ertan Ç, ÖZeke Ö. Prognostic value of neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio in patients with pulmonary embolism. Turk J Med Sci. 2014;44(1):50-55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erden F, Karagoz H, Avci A, et al. Which one is best? Platelet/lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio or both in determining deep venous thrombosis in behcet' s disease? Biomed Res. 2017;28(12):5304-5309. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farah R, Nseir W, Kagansky D, Khamisy-farah R. The role of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio, and mean platelet volume in detecting patients with acute venous thromboembolism. Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(1):e23010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mansiroglu AK, Sincer I, Cosgun M, Gunes Y. Dating thrombus organization with eosinophil counts in deep venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2021;9(4):874-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ming L, Jiang Z, Ma J, Wang Q, Wu F, Ping J. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and platelet indices in patients with acute deep vein thrombosis. Vasa. 2018;47(2):143-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rinaldi I, Hamonangan R, Azizi MS, et al. Diagnostic value of neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and D-dimer as biological markers of deep vein thrombosis in patients presenting with unilateral limb edema. J Blood Med. 2021;12:313-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tural K. Can Complete Blood Cell Count Parameters Predict Deep Vein Thrombosis? Acta Clin Croat. 2020;59(4):661-666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kayrak M, Erdoğan HI, Solak Y, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a restrospective study. Heart Lung Circ. 2014;23(1):56-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu C, Zhan HL, Huang ZH, et al. Prognostic role of the preoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and albumin for 30-day mortality in patients with postoperative acute pulmonary embolism. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20(1):180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Duman D, Sonkaya E, Yıldırım E, et al. Association of inflammatory markers with mortality in patients hospitalized with non-massive pulmonary embolism. Turk Thorac J. 2021;22(1):24-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Siddiqui F, Garcia-Ortega A, Kantarcioglu B, et al. Cellular indices and outcome in patients with acute venous thromboembolism. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost. 2022;28:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jia D, Liu F, Zhang Q, Zeng GQ, Li XL, Hou G. Rapid on-site evaluation of routine biochemical parameters to predict right ventricular dysfunction in and the prognosis of patients with acute pulmonary embolism upon admission to the emergency room. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;32(4):e22362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Galliazzo S, Nigro O, Bertù L, et al. Prognostic role of neutrophils to lymphocytes ratio in patients with acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13(4):603-608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q, Ma J, Jiang Z, Ming L. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in acute pulmonary embolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Angiol. 2018;37(1):4-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kruger PC, Eikelboom JW, Douketis JD, Hankey GJ. Deep vein thrombosis: update on diagnosis and management. Med J Aust. 2019;210(11):516-524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson ED, Schell JC, Rodgers GM. The D-dimer assay. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(7):833-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kunutsor SK, Seidu S, Blom AW, Khunti K, Laukkanen JA. Serum C-reactive protein increases the risk of venous thromboembolism: a prospective study and meta-analysis of published prospective evidence. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(8):657-667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gok M, Kurtul A. A novel marker for predicting severity of acute pulmonary embolism: systemic immune-inflammation index. Scand Cardiovasc J. 2021;55(2):91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seyit M, Avci E, Nar R, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, lymphocyte to monocyte ratio and platelet to lymphocyte ratio to predict the severity of COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;40:110-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tezcan D, Körez MK, Gülcemal S, Hakbilen S, Akdağ T, Yılmaz S. Evaluation of diagnostic performance of haematological parameters in Behçet's disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(10):e14638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]