Abstract

Background

The relative frequencies of indications for primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) are not well-established. This study aims to establish the incidence of THA performed for Avascular Necrosis of the hip (AVN), as well as the other most common indications for THA in the United States, as compared to the incidences at a high-volume tertiary referral center in Miami, Florida. We hypothesize that the relative incidence of AVN and each other indication for THA will vary significantly between the United States as a whole and the tertiary referral center.

Methods

A query of the 2016–2017 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) and a tertiary referral center adult reconstruction registry was completed. The relative frequencies of each indication for THA, demographics, and behavioral risk factors were analyzed.

Results

225,061 primary THA patients in the National Inpatient Sample database and 447 in the Miami tertiary referral center database were included in the final analysis. The proportion of primary THA for AVN in the NIS database (5.97%) was significantly lower than the same proportion in the tertiary referral center database (22.2%), p < .001. There was no significant difference in the incidence of primary THA for osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis, or hip dysplasia between the two populations.

Conclusion

The incidence of THA for AVN is significantly different between a tertiary referral center and the greater United States. Patient demographics, race, and behavioral risk factors are associated with the disparity. Orthopaedic surgeons should recognize the differences in THA indication between populations when counseling patients on treatments, outcomes, and the most current literature.

Keywords: National inpatient sample, Avascular necrosis, AVN Total hip arthroplasty, Osteoarthritis, OA, Indications

1. Introduction

Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) is a highly effective procedure being performed at increasing rates.1 As the global prevalence of osteoarthritis (OA) rises it has become one of the most common indications for THA.2,3 In developed countries, up to 90% of THAs are performed for OA.2 Other common indications include femoral neck fracture, avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head, and inflammatory arthritis.2 However, the rates of these conditions vary between populations.

In the developing world, AVN of the femoral head is highly prevalent due to steroid abuse, chronic alcohol consumption, trauma, sickle cell disease, and HIV.4,5 In these countries the disease is a leading cause of THA.4,5 Conversely, in developed countries, AVN accounts for a much smaller portion of THAs.6 For example, in the United States (US), AVN accounts for roughly 10% of THAs.7

THA outcomes are worse in the setting of AVN, which has been hypothesized to be due to the higher incidence of comorbidities and complexity of patients with AVN (as approximated by higher ASA class), as well as potential differences in bone structure and quality.8, 9, 10, 11 Therefore, arthroplasty research from countries with lower incidence of AVN may not be as applicable to developing countries. Likewise, there are lower-resource populations within the US which may suffer from increased prevalence of AVN and the associated suboptimal THA outcomes.12

The current study aims to compare the incidence of primary THAs performed for AVN on a national level to the incidence at a tertiary referral center in a racially diverse lower resource setting in Miami, Florida. We hypothesize that the incidence of THA for AVN will vary significantly between the national and the regional center populations.

2. Materials and methods

The current study analyzed only research database derived de-identified patient information and was therefore exempt from Internal Review Board approval. An analysis of the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2016 to 2017 was conducted. ICD-10-CM/PCS procedures codes were used to identify all primary THA procedures. THAs were then categorized by diagnoses: AVN, OA, femoral head and neck fracture, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, pathological fracture, and hip dysplasia. Diagnoses were assigned by searching diagnosis codes for keywords, and then assigning all codes containing the keywords to a given diagnosis. For example, for AVN, codes containing “osteonecrosis” or “avascular necrosis” and “hip” were considered a diagnosis of AVN, while similar procedures were used for the other diagnoses. In the case of multiple diagnoses, the most immediate cause for surgery was considered. Priority was given to pathological fracture followed by ankylosing spondylitis, femoral head and neck fracture, AVN, rheumatoid arthritis, hip dysplasia, and OA, respectively. Patients who were not already classified and who had codes for periprosthetic fracture or periprosthetic osteolysis were excluded from the dataset. All remaining THAs with no diagnosis or code for secondary OA were included in an “other” category. Data on demographics and AVN risk factors was recorded.

A second database containing de-identified information of THA patients from University of Miami Health Tower Tertiary Referral Center was queried; the diagnoses were categorized accordingly. This database did not include the diagnosis of pathological fracture; rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis were combined under the category of immune arthritis. NIS database THAs were reclassified to match this database for comparison; pathological fractures of the NIS cohort were reclassified under “other” and rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis were reclassified under immune arthritis. The database also did not include demographic information other than ethnicity, age, and sex of patients. The proportion of AVN was calculated for each database and compared for statistically significant differences.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Data on demographics, comorbidities, and diagnoses incidences are presented as descriptive statistics. Two Proportions Z-Test or Independent Samples T-Test analyses were performed to assess for statistically significant differences between cohorts and sub-cohorts. Statistics were performed using Excel (Version 16.55). A p-value < .05 was considered statistically significant. Odds ratios were calculated for ethnicity or sex given that the patient underwent THA for AVN. This was done by dividing the proportion of total THA for AVN in each ethnicity/sex by the proportion of total THA done for all other indications for the same ethnicity/sex.

3. Results

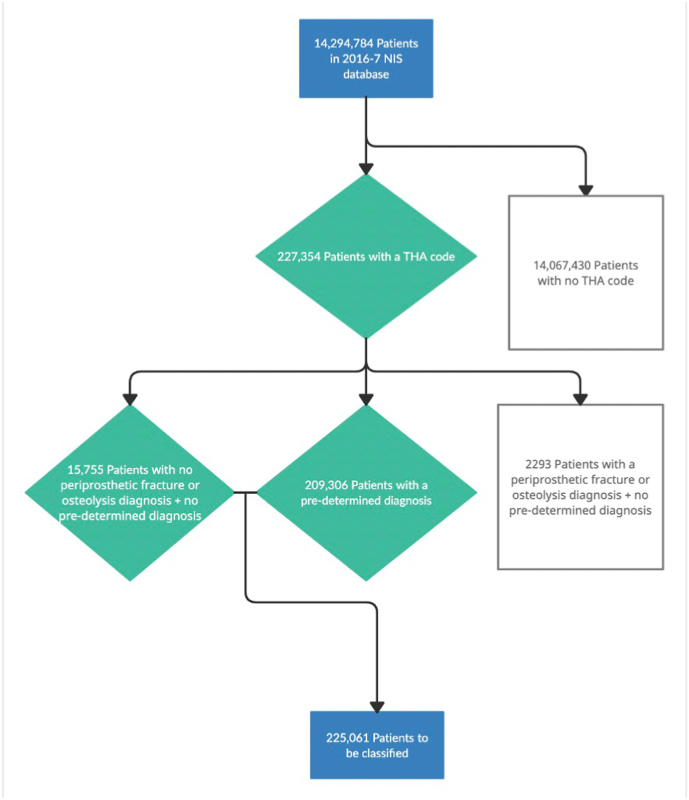

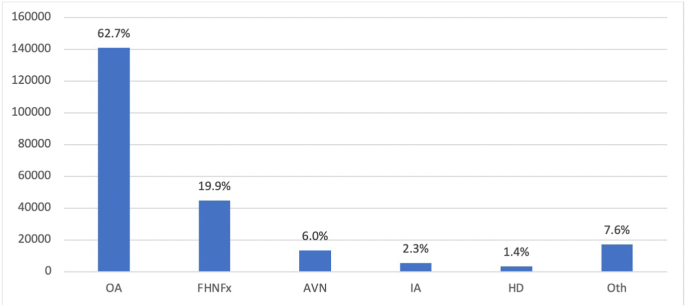

Data on 14,294,784 patients in the 2016-17 NIS database was reviewed. 227,354 THAs were identified. 2293 patients were excluded for diagnosis of periprosthetic fracture or periprosthetic osteolysis leaving 225,061 patients (1.6%) in the final cohort (Fig. 1). The incidence of primary THA indications can be seen in Fig. 2. AVN was the third most common indication (5.97%).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of data collection in the National Inpatient Sample

Data on 14,294,784 from the 2016–2017 NIS database was reviewed. A final THA cohort used in analysis included 225,061 patients. “Pre-determined” diagnoses included avascular necrosis of the hip, osteoarthritis of the hip, rheumatoid arthritis, hip dysplasia, femoral head/neck fracture, ankylosing spondylitis, and pathological fracture. Patients with a THA code and either a pre-determined diagnosis or no periprosthetic fracture or osteolysis diagnosis were the patients used in the final analysis.

Fig. 2.

Total Diagnoses Among Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients, National Inpatient Sample Database 2016-17

Osteoarthritis of the hip (OA) was the most common indication for surgery for Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) patients in the NIS database from 2016 to 17. Other diagnoses considered were Femoral Head/Neck Fracture (FHNFx), Avascular Necrosis of the hip (AVN), Inflammatory Arthritis (IA), Hip Dysplasia (HD), and Other (Oth).

Based on data from the NIS, White race was associated with significantly decreased incidence of THA for AVN relative to the pooled cohort of non-White THA patients, z = 33.30, p < .001. Overall rate of THA for AVN in White race was 5.30% of THAs performed. Each other race analyzed (Black, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, and Other) was individually associated with a significantly increased incidence of THA for AVN relative to the pooled cohorts of non-Black, non-Hispanic, non-Native American, and non-Other THA patients, respectively (all z > 4.44, p < .001). Black race had the highest rate of THA performed for AVN at 12.3%. Male sex, corticosteroid abuse, alcohol abuse, smoking, sickle cell disease, and HIV were all significant risk factors for THA for AVN (all z > 17.82, p < .001). Odds ratios for these demographic and health risk factors are seen in Table 1, Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Odds ratios of having selected demographic characteristics among patients with total hip arthroplasty performed for avascular necrosis as compared to all other indications, 2016-17 NIS database.

| Characteristic | OR |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| White | 0.877 |

| Black | 2.20 |

| Hispanic | 1.31 |

| API | 1.49 |

| Native American | 1.77 |

| Other | 1.31 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1.31 |

| Female | 0.785 |

All races/ethnicities as defined by the NIS.

OR- Odds Ratio.

API-Asian/Pacific Islander.

Table 2.

Odds ratios of having selected conditions among patients with total hip arthroplasty performed for avascular necrosis as compared to all other indications, 2016-17 NIS database.

| Condition | OR |

|---|---|

| HIV | 11.9 |

| SCD | 17.2 |

| Smoking | 2.13 |

| Alc Abuse | 2.70 |

| Steroid Abuse | 2.17 |

OR- Odds Ratio.

SCD- Sickle Cell Disease.

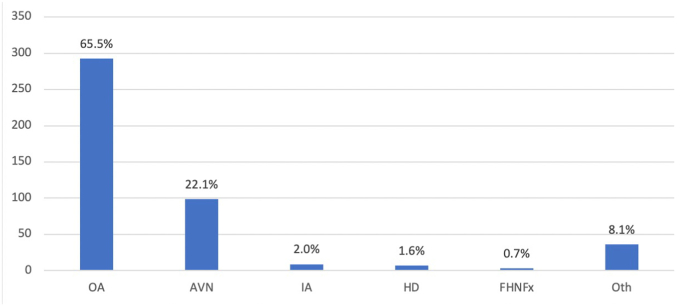

Of the 503 patients in the tertiary referral center database, 464 were primary THAs. 447 had an associated diagnosis and were included in the final analysis. The proportion of all indications for THA can be seen in Fig. 3. 16.5% of THAs performed for patients of White race were for AVN; for patients of Black race, this number was 29.7%. Odds ratios for relative AVN prevalence among races in this database are seen in Table 3. Overall, the proportions of patients who had a primary THA for AVN in the NIS database (5.97%) was significantly lower than the same proportion in the tertiary referral center database (22.15%), z = 14.39, p < .001. A comparison of the indications for primary THA between the two cohorts is seen in Table 4.

Fig. 3.

Total Diagnoses Among Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients, Miami Tertiary Referral Center

Osteoarthritis of the hip (OA) was the most common indication for surgery for Total Hip Arthroplasty (THA) patients in the Miami tertiary referral center. Other diagnoses considered were Avascular Necrosis of the hip (AVN), Inflammatory Arthritis (IA), Hip Dysplasia (HD), Femoral Head/Neck Fracture (FHNFx), and Other (Oth).

Table 3.

Odds ratios of having selected demographic characteristics among patients with total hip arthroplasty performed for avascular necrosis as compared to all other indications, tertiary referral center database.

| Characteristic | OR |

|---|---|

| Race | |

| White | 0.696 |

| Black | 1.49 |

| Hispanic | 1.20 |

| Other | 0.940 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 1.26 |

| Female | 0.739 |

All races/ethnicities as defined by the database.

OR- Odds Ratio.

Table 4.

Selected Proportion of Diagnoses Among Total Hip Arthroplasty Patients, 2016-17 NIS Database vs Miami Tertiary Referral Center (MTRC).

| Database | N | %OA | %FHNFx | %AVN | %IA | %HD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIS | 225061 | 62.7% | 19.9% | 6.0% | 2.3% | 1.4% |

| MTRC | 447 | 65.5% | 0.7% | 22.1% | 2.0% | 1.6% |

| Z | 1.26 | 10.19 | 14.39 | 0.59 | 0.26 | |

| P-Value | 0.208 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.555 | 0.793 |

Note. Rows will not add to 100% as not all indications for Primary THA are listed in both databases, and therefore were excluded.

NIS- National Inpatient Sample.

MTRC- Miami Tertiary Referral Center.

OA- Osteoarthritis.

FHNFx- Femoral Head and Neck Fracture.

AVN- Avascular Necrosis.

IA- Inflammatory Arthritis.

HD- Hip Dysplasia.

4. Discussion

Avascular necrosis of the hip is a debilitating condition which affects 10,000 to 20,000 patients in the United States annually.13 Previous estimates have shown that about 10% of all THAs are performed for AVN.14 Conversely, in lower resource countries, AVN is often the leading indication for THA.4,5 For example, THA for AVN is highly prevalent in India secondary to high incidence of AVN risk factors.4 Risk factors include: sickle cell disease, regional trauma, alcohol abuse, steroid use, sarcoidosis, and viruses including HIV and hepatitis.13 Those who complete THAs for AVN compared to OA have significantly worse outcomes.9 Certain subpopulations within the US may have higher rates of AVN risk factors and the associated poor THA outcomes. Our goal was to determine if there was a difference in the rates of THA for AVN in a lower resource, racially diverse setting in the US compared to the US as a whole.

Our data showed the rate of THA for AVN was significantly higher in our tertiary referral center than the national average (p < .01). In Miami, the prevalence was 22.15% and nationally the prevalence was 5.97%. In both cohorts, white race was a protective factor against THA for AVN. Notably, however, the incidence of THA for AVN was higher in patients of White race in the Miami database than it was for patients of Black race (the race with the highest rate) in the NIS database. In the NIS cohort, all races other than White, male sex, and all assessed comorbidities were significant risk factors. As far as we know, this is the first study to explore the discrepancy in THA for AVN rates in the US.

The majority of arthroplasty research is completed in developed countries. These countries perform THAs predominantly for OA.15 Therefore, the literature is less generalizable to regions where AVN is more prevalent. For example, Germany and Sweden have less than a 0.05% incidence of the disease.16,17 Likewise, countries with major joint replacement registries including Sweden, Australia and Canada report that only 2.8–6% of THAs are performed for AVN.18 How can regions with near 50% incidence of THA for AVN, like India or Sub-Saharan Africa, reliably utilize THA research from developed countries5? Compared to those with OA, AVN patients have increased 30-day and long-term complication rates. In the short term, AVN patients have increased rates of readmission, surgical site infection, and medical complications.9 In a 10-year follow up, Ancelin and Reina et al. found that AVN is associated with increased revision and dislocation rates following THA.8 Our data now shows that micro-populations within the US may also be disadvantaged in regard to the utility of available joint replacement research.

Our data has established demographics and risk factors which are associated with increased incidence THA for AVN. Others have demonstrated similar data for African American patients.11 While race/genetics may be a factor for this disparity (Sickle Cell Disease), we believe socioeconomic discrepancies are overwhelmingly responsible. Poverty is associated with 4 of the 5 risk factors we have found to be correlated with THA for AVN (HIV, Sickle Cell Disease, Smoking, and Alcohol Abuse).19, 20, 21 The poverty rate in Miami-Dade County is 15.7%; this is roughly 50% higher than the national average.22,23 As a result, Miami-Dade County has a higher incidence of risk factors. For example, HIV prevalence in Miami is more than 2.5 times higher than the national average.24,25 Similarly, Miami-Dade County has a black population that is 28% higher than the national average proportion, which can be used as a proxy to estimate Sickle Cell Disease prevalence.22 Other reasons for the disparity may be cultural in nature.

AVN of the femoral head is a more urgent indication for THA than OA. Therefore, OA is more likely to be completed in an elective setting (such as in a tertiary referral center). White Americans are more likely to undergo elective joint replacement surgery than other races when controlling for age, access to insurance, or rates of OA.26 The reason for this difference has been explored in the literature. Research has shown that African Americans have worse attitudes, and lower preference towards elective joint replacement procedures, and are less willing to pay for them compared to White Americans.26 Therefore, our finding of a significantly higher rate of THA for AVN in our regional center can be partially explained by Miami-Dade County's higher-than-average Black population. Ultimately, however, the observed differences cannot be explained by racial factors alone, and are unlikely to be due to the fact that the Miami data comes from a tertiary referral center, as we would expect the opposite result if this were the case. The socioeconomic discrepancies that likely power this difference require further research.

There are limitations to our current study. When using a large database like the NIS, misclassifications can occur27; we are limited to only the data provided by the database when examining our cohort. Therefore, there may have been minor inaccuracies in reported diagnoses and under-coding of AVN risk factors and demographic information.28 With this being said, given the magnitude of the differences reported, it is quite unlikely that coding errors would have any meaningful impacts on the conclusions of this study. We were also unable to reliably differentiate between traumatic and atraumatic AVN in either database, which limits our characterization of the disease. Other potential limitations with large third-party database studies include external validity, selection bias and confounding; these are known complications and are thought to not significantly affect the impact of such a study.28 Moreover, with a large cohort, even small differences may be statistically significant. We also had a large mismatch in our two cohorts’ sizes; this weakens our statistical comparisons. However, when comparing national and local averages, this contrast is expected. Finally, our implied eligibility criteria were too narrow to capture the entirety of the United States and the entirety of the regional population in Miami; while this does limit the potential conclusion that incidence of THA for AVN is different in Miami versus USA, it does not weaken the main argument that certain regional populations may see different incidences of THA for AVN than the average populous of the country they belong to. Despite our stated limitations, we believe this data makes an important contribution to the field of arthroplasty.

5. Conclusion

The incidence of THA for AVN is significantly different between a tertiary referral center in Miami-Dade County and the greater United States. According to national data, up to 6% of THAs are performed for AVN in the US. However, at the center studied in Miami-Dade County, up to 22% of THAs are performed for AVN. Patient demographics, race, and behavioral risk factors are associated with the disparity. Orthopaedic surgeons should recognize the differences in THA indication between populations when counseling patients on treatments, outcomes, and the most current literature.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional ethical committee approval statement

All analysis in the current study was derived from de-identified databases therefore exempting it from our Institutions Internal Review Board review.

Authors contributions

Sagie Haziza- Conceptualization, methodology, writing, review and editing, project administration; Ramakanth Yakkanti- Conceptualization, methodology, writing, review and editing, project administration, supervision; Nathan Wasserman- Methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation; review and editing; Michele D'Apuzzo- Conceptualization, methodology, review and editing; supervision; project administration; Victor Hernandez- Conceptualization, methodology, review and editing; supervision; project administration.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

none.

References

- 1.Singh J.A., Yu S., Chen L., Cleveland J.D. Rates of total joint replacement in the United States: future projections to 2020-2040 using the national inpatient sample. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:1134–1140. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.170990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson R.J., Palmer A.J., Taylor A., Porter M.L., Malchau H., Glyn-Jones S. Hip replacement. Lancet. 2018;392:1662–1671. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31777-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vina E.R., Kwoh C.K. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis: literature update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:160–167. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vardhan H., Tripathy S.K., Sen R.K., Aggarwal S., Goyal T. Epidemiological profile of femoral head osteonecrosis in the north Indian population. Indian J Orthop. 2018;52:140. doi: 10.4103/ORTHO.IJORTHO_292_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies P.S.E., Graham S.M., Maqungo S., Harrison W.J. Total joint replacement in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Trop Doct. 2019;49:120. doi: 10.1177/0049475518822239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergman J., Nordström A., Nordström P. Epidemiology of osteonecrosis among older adults in Sweden. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30:965–973. doi: 10.1007/S00198-018-04826-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seijas R., Sallent A., Rivera E., Ares O. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J Invest Surg. 2019;32:218–219. doi: 10.1080/08941939.2017.1398282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ancelin D., Reina N., Cavaignac E., Delclaux S., Chiron P. Total hip arthroplasty survival in femoral head avascular necrosis versus primary hip osteoarthritis: case-control study with a mean 10-year follow-up after anatomical cementless metal-on-metal 28-mm replacement. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102:1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/J.OTSR.2016.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sodhi N., Anis H.K., Coste M., Piuzzi N.S., Jones L.C., Mont M.A. Thirty-day complications in osteonecrosis patients following total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:2136–2143. doi: 10.1016/J.ARTH.2020.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh J.A., Chen J., Inacio M.C., Namba R.S., Paxton E.W. An underlying diagnosis of osteonecrosis of bone is associated with worse outcomes than osteoarthritis after total hip arthroplasty. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2017;18:8. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1385-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Ambrosi R., Biancardi E., Massari G., Ragone V., Facchini R.M. Survival analysis after core decompression in association with platelet-rich plasma, mesenchymal stem cells, and synthetic bone graft in patients with osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Joints. 2018 Feb 12;6(1):16–22. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1626740. PMID: 29675502; PMCID: PMC5906108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayers W., Schwartz B., Schwartz A., Moretti V., Goldstein W., Shah R. National trends and in hospital outcomes for total hip arthroplasty in avascular necrosis in the United States. Int Orthop. 2016;40:1787–1792. doi: 10.1007/S00264-015-3089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hsu H., Nallamothu S.V. Hip osteonecrosis. StatPearls. 2022 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499954/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barney J., Piuzzi N.S., Akhondi H. Femoral head avascular necrosis. RadiopaediaOrg. 2021 doi: 10.53347/rid-44260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gademan M.G.J., Hofstede S.N., Vliet Vlieland T.P.M., Nelissen R.G.H.H., Marang-Van de Mheen P.J. Indication criteria for total hip or knee arthroplasty in osteoarthritis: a state-of-the-science overview. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2016;17:1–11. doi: 10.1186/S12891-016-1325-Z/TABLES/4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arbab D., König D.P. Atraumatic femoral head necrosis in adults: epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:31. doi: 10.3238/ARZTEBL.2016.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bergman J., Nordström A., Nordström P. Epidemiology of osteonecrosis among older adults in Sweden. Osteoporos Int. 2019;30:965–973. doi: 10.1007/S00198-018-04826-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Petek D., Hannouche D., Suva D. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: pathophysiology and current concepts of treatment. EFORT Open Rev. 2019;4:85–97. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pellowski J.A., Kalichman S.C., Matthews K.A., Adler N. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the U.S. HIV epidemic. Am Psychol. 2013;68:197. doi: 10.1037/A0032694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asnani M.R., Madden J.K., Reid M., Greene L.G., Lyew-Ayee P. Socio-environmental exposures and health outcomes among persons with sickle cell disease. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0175260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cerdá M., Diez-Roux A.V., Tchetgen Tchetgen E., Gordon-Larsen P., Kiefe C. The relationship between neighborhood poverty and alcohol use: estimation by marginal structural models. Epidemiology. 2010;21:482–489. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0B013E3181E13539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: miami-dade county, Florida. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/miamidadecountyflorida/POP060210 n.d.

- 23.Semega J, Kollar M, Shrider EA, Creamer J. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2019-Current Population Reports. (n.d).

- 24.Miami (Miami-Dade county) - AIDSVu. https://aidsvu.org/local-data/united-states/south/florida/miami/ n.d.

- 25.U.S. Statistics | HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics n.d.

- 26.Ibrahim S.A. Racial variations in the utilization of knee and hip joint replacement: an introduction and review of the most recent literature. Curr Orthop Pract. 2010;21:126. doi: 10.1097/BCO.0B013E3181D08223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto R., Brodt E., Skelly A., Dettori J. Administrative database studies: goldmine or goose chase? Evid Base Spine Care J. 2014 doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390027. 05:074–076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li I., Sm F., J D., J H., Es F., T H. Comorbidities, complications, and coding bias. Does the number of diagnosis codes matter in predicting in-hospital mortality? JAMA. 1992;267:2197–2203. doi: 10.1001/JAMA.267.16.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]