Abstract

Long COVID is characterized by persistent and debilitating long-term symptoms from COVID-19. Many persons with Long COVID began gathering in online communities during the early phases of the pandemic to share their illness experiences. This qualitative interview study explored the subjective experiences of 20 persons with Long COVID recruited from five online communities. Their understandings of illness and associated implications for social relationships with family and friends, healthcare professionals, and online community members were explored. Three themes were identified from our analysis, including (1) complex and unpredictable illness experienced amid an evolving understanding of the pandemic; (2) frustration, dismissal, and gaslighting in healthcare interactions; and (3) validation and support from online communities. These findings highlight the significant uncertainty that persons with Long COVID navigated, the features of their often dismaying healthcare experiences, and the ways in which online communities aided them in understanding their illness.

Keywords: Long COVID, Chronic illness, Online communities, Gaslighting, Uncertainty

Funding Disclosure: This study was supported by a grant from the University Research Council at Appalachian State University (#228222).

1. Introduction

Understanding the clinical manifestation of COVID-19 has been an ongoing focus of scientists and the broader public since its identification in December 2019 (Jin et al., 2020; Lauer et al., 2020). Early reports on COVID-19 focused largely on cohorts of hospitalized patients with acute presentations of illness that characterized disease progression by a short incubation period (i.e. the length of time between infection and symptom onset; initial estimates ranged from 5 to 7 days) followed by fever, gastrointestinal, and upper respiratory symptoms lasting roughly two weeks (Cheng et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2020; Jin et al., 2020; Lauer et al., 2020; Lovato & de Filippis, 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). This early understanding of the COVID-19 illness experience differed markedly from accounts by persons who described prolonged, fluctuating, and debilitating symptoms months after a presumed recovery from an initial infection (Carfì et al., 2020; COVID-19 Body Politic Slack Group, 2020; COVID Symptom Study, 2020; Godlee, 2020; Mahase, 2020; Nath, 2020). Indeed, research published during the first year of the pandemic suggested that more than one third of persons who tested positive for COVID-19 had not returned to their usual state of health within two to three weeks, including younger adults with no underlying health conditions and spanning both physical and psychosocial symptoms that negatively impacted quality of life and social roles (Aiyegbusi et al., 2021; Burges Watson et al., 2021; Davis et al., 2021; Tenforde et al., 2020).

This longer and more complex course of COVID-19, along with the wide range of health problems encompassed by people experiencing the condition, became known as “Long COVID” (Callard & Perego, 2021; CDC, 2022; Nath, 2020). A notable feature of Long COVID was the early mobilization of patients in online communities to share their symptoms and stories with one another. Within these communities, patients emphasized that the mechanisms of long-term symptoms were unknown, that many cases initially classified as “mild” according to pneumonia severity were not necessarily mild at all, and that many patients with persistent symptoms experience disability and discriminatory treatment in accessing healthcare (Callard & Perego, 2021; Nath, 2020; Perego et al., 2020).

Only a handful of studies to date have explored the illness experiences of persons with Long COVID (i.e. qualitative investigation of subjective experiences of illness). The present study contributes to this literature by providing a detailed account of the subjective experiences of U.S. adults with Long COVID, including their understandings of illness and relationships with healthcare professionals and online communities. Drawing on 20 in-depth interviews among persons with Long COVID, our analysis reveals how they managed complex and unpredictable symptoms amid a period of heightened medical and scientific uncertainty. We also highlight their dismaying experiences navigating healthcare interactions, including those which left them feeling frustrated, confused, and questioning the validity of their symptoms and illness. Finally, we document the roles that online communities played in connecting them with similar others who provided recognition and support.

2. Conceptual and theoretical framing

2.1. Illness experiences of long COVID amid medical and scientific uncertainty

Conceptions of disease (i.e. abnormalities of bodily organs and systems) and illness (i.e. the social meaning of a condition and its associated changes in functioning) are shaped by medical discourse as well as individual experiences (Conrad & Barker, 2010; Eisenberg, 1977). Medicine in the 21st century has been transformed through biomedical advances in new drugs and treatments, as well as by increased risk and surveillance practices (Clarke et al., 2003). These advances have been visible during the COVID-19 pandemic through rapid genome sequencing of the virus, diagnostic testing methods, the condensed development of an effective vaccine, and the continuous tracking of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths on interactive dashboards (D'Cruz et al., 2020; Heaton, 2020; Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center, 2021). While the speed of these biomedical developments has garnered great attention, considerable scientific uncertainty surrounds the virus that causes COVID-19, its transmission and variants, as well as the long-term health and social consequences of infection (Mandavilli, 2021). Within this context of scientific uncertainty, patients and lay audiences have contributed to our understanding of COVID-19 by challenging dominant assumptions about morbidity and illness duration, and even leading their own research to characterize Long COVID (Callard & Perego, 2021). These audiences have made several epistemic contributions to knowledge about Long COVID, including its naming, the complex and multi-systemic nature of symptoms, temporal patterns in disease cycles and progression, and challenging categorization of disease severity along axes of “mild,” “severe,” and “critical” (Perego & Callard, 2021).

While these represent important contributions to our understanding of Long COVID, substantial uncertainty persists about the long-term health and functioning of persons with this illness (Brown & O’Brien, 2021). Several aspects of Long COVID likely contribute to uncertainty, including ambiguity about symptom patterns, complex treatments and systems of care, limited information about diagnosis and severity, and unpredictable symptoms and prognosis (Mishel, 1988).

Exploring the illness experience of Long COVID can help provide a more comprehensive picture of the meaning, significance, context, and consequences of illness, as well as persons' responses, actions, and adaptations to illness (Bury, 1991; Pierret, 2003). These studies also help to center knowledge about illness—not only the objective observations of modern medicine and the “pathological gaze,” but also the subjective experiences and narratives of people who suffer from a given condition (Mol & Law, 2004). Long COVID presents a unique case for examining the illness experience because of its status as a new and multifaceted patient-made chronic illness (Baz et al., 2021; Callan et al., 2021). Existing research on the Long COVID illness experience suggests that people invest substantial effort making sense of unusual and unpredictable symptoms, that they report disbelief from family and friends, and that they have difficulties finding supportive healthcare professionals (Callan et al., 2021; Gorna et al., 2021; Kingstone et al., 2020; Rushforth et al., 2021; Taylor et al., 2021). Collectively, this work suggests that a promising area for further study involves how subjective experiences of Long COVID are shaped by social interactions, including with family and friends in one's social networks, healthcare professionals, and others coping with Long COVID who share their stories in online communities.

2.2. Online communities and their role in the long COVID illness experience

Many people with Long COVID took to online communities to share symptoms, communicate fraught encounters with medical professionals, and offer support and advice to one another (Moyer, 2020). Recently, scholars have begun to highlight the ways in which online communities facilitate sharing of illness narratives, social support, and uncertainty management among persons with Long COVID (Day, 2022; Kingstone et al., 2020; Southwick et al., 2021; Thompsonet al., 2021). Online communities connect people with a range of illnesses and medical conditions in their efforts to seek information, support, and recognition (Conrad et al., 2016). Social media, including Facebook (groups) and Reddit (subreddits), are popular platforms for connecting people with chronic illness (Maslen & Lupton, 2019; Thompson et al., 2021). Online communities serve several functions for people with chronic illness, including knowledge sharing, identity work, peer-to-peer support and connectivity, advocacy, and mobilization (Kingod et al., 2017). In cases where scientific and medical uncertainty surrounds illness symptoms and their explanation, online communities can also serve as sites for people to seek recognition of their illness and validation of suffering that may be dismissed or disparaged by medical professionals during formal healthcare encounters (Barker, 2008). Further, people with chronic illness can use online communities to share illness narratives and treatments based on experiential knowledge (Maslen & Lupton, 2019).

Online communities should have a special significance for persons experiencing Long COVID due to pandemic social distancing restrictions that encouraged virtual communication, as well as limited information about persistent and varied COVID-19 symptoms in popular and medical discourse. Existing studies of online communities for persons with Long COVID suggest that these platforms provide spaces for persons to share their symptoms and health concerns, experiences with illness duration, test results and diagnosis, and worsening anxiety related to both their condition as well as frustration with doctors and feelings of invalidation (Thompson et al., 2021). Moreover, while persons with Long COVID turned to online communities for information and support following an “abyss of silence” from their healthcare professionals, these online communities contained largely unregulated content shared by members with widely varying symptoms and experiences, contributing to anxiety and frustration about one's own illness trajectory (Day, 2022). The present study aims to extend upon this research by exploring the subjective experiences of Long COVID and the ways in which interviewees' understandings of their illness were shaped by social interactions. We also clarify how online communities aided interviewees in navigating a complex illness amid significant uncertainty. We focus on three research questions: (1) How do persons experiencing Long COVID describe their illness experience? (2) How do they navigate illness uncertainty and forge an understanding of their illness through social interactions? (3) What role do online communities play in fostering validation and support of their illness experience as they seek diagnosis and treatment for their condition?

3. Materials and methods

Twenty self-identified long-haulers were recruited for interviews from five online communities between March and April 2021. These online communities included: (1) a public subreddit for patients with COVID-19 created in March 2020 with ∼12,400 members, (2) a public subreddit for Long Haulers created in August 2020 with ∼1200 members, (3) a private Facebook Group for COVID-19 support created in August 2020 with ∼23,400 members, (4) private Facebook Group for Long COVID support created in November 2020 with ∼16,800 members, and (5) a private Facebook Group for Long Haulers created in August 2020 with ∼2700 members. Permission was obtained from administrators of each community to post a recruitment message explaining the study and inviting participation. While each of these online communities were international in the sense that English-speaking users could post and comment on the forum pages, our research was limited to U.S. residents with Long COVID. Inclusion criteria for this study were: (1) 18 years of age or older, (2) U.S. resident, (3) long-term symptoms and effects from COVID-19, (4) one or more consultations with a healthcare professional about their COVID-19 symptoms, and (5) connection with others with Long COVID in online communities, either by reading the posts of others, commenting on their posts, or sharing one's own story about their illness experience. Demographic information collected through a brief electronic questionnaire included age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, state of residence, and date of symptom onset.

Potential participants who completed this survey were contacted by one of four interviewers. The interviewers held doctorate degrees with training in qualitative interview methods and represented different gender and ethnic groups. A semi-structured interview guide was developed collaboratively by our research team to cover key topics related to our research questions and obtain a detailed illness narrative from each participant that included: (1) descriptions of their symptoms, (2) experiences with healthcare professionals, diagnostics, testing and medical treatments, and (3) navigation of online communities. The study team reviewed several iterations of the interview guide to improve the clarity, parsimony, and ordering of questions. While our research and interview guide was not informed by first-hand experience with Long COVID, one member of our study team had similar experience with unexplained chronic symptoms and medical uncertainty in healthcare interactions that culminated in an eventual diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Using this interview guide (see Appendix A), interviews were conducted over the phone or via videoconference, audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim. The average length of interviews was 36 min (Standard Deviation = 13 min; Range 17–62 min). A majority of participants identified as women (80%), White non-Hispanic (85%), and had a four-year college degree or higher (75%). The average age was 42 years (standard deviation = 12 years; range: 20–64 years); more than half of participants were 35–54 years of age (55%). Interviewees were experiencing COVID symptoms for an average of 232 days (standard deviation = 112 days; range: 96–377 days) by the time of interview (see Table 1 ). Consent was obtained prior to the start of each interview; all procedures were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Appalachian State University.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of study participants (N = 20).

| Study Variable | % (N) or Mean (Standard Deviation) |

|---|---|

| Total Sample | 100.0% (20) |

| Gender | |

| Woman | 80.0% (16) |

| Man | 15.0% (3) |

| Non-Binary/Third Gender | 5.0% (1) |

| Age | 42.0 (12.4) |

| 18–34 Years | 25.0% (5) |

| 35–54 Years | 55.0% (11) |

| 55+ Years | 20.0% (4) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White Non-Hispanic | 85.0% (17) |

| Hispanic | 10.0% (2) |

| Asian | 5.0% (1) |

| Level of Educational Attainment | |

| 4-Year College Degree or Higher | 75.0% (15) |

| Some College (1–3 Years) | 20.0% (4) |

| High School or GED | 5.0% (1) |

| U.S. Census Region | |

| West | 55.0% (11) |

| South | 20.0% (4) |

| Midwest | 15.0% (3) |

| Northeast | 10.0% (2) |

| Length of COVID-19 Symptoms (In Days) | 232.0 (112.6) |

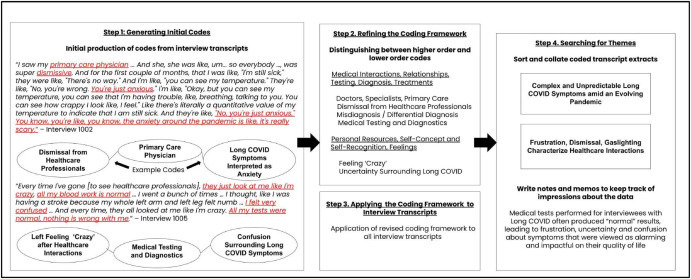

Thematic analysis was used to draw insights from the qualitative interviews by examining the perspectives and experiences of different participants and highlighting their similarities and differences (Nowell et al., 2017). Interview transcripts were imported into Dedoose for coding and analysis. Five authors (DR, NS, JC, EB, CT) became familiar with the data through reading transcripts line-by-line and documenting initial thoughts about codes and themes. A coding framework was collaboratively developed by reviewing a subset of five transcripts for both a priori topic areas (e.g., symptoms, healthcare interactions, communications and interactions in online communities) and emerging concepts (e.g., symptom progression and impacts on quality of life, illness recognition, paths to recovery). This framework was revised and refined over the course of several team meetings, during which time feedback was incorporated on content and parsimony. The final framework was applied by coding all transcripts. The authors then independently reviewed coded excerpts related to each of the research questions, meeting several times to discuss patterns, connections, and distinctions in the data. Interviewee experiences were compared and contrasted to highlight emergent themes and divergent perspectives. For example, a review of coded excerpts for the type, range/combination, severity, and progression of Long COVID symptoms, along with those related to illness uncertainty, representations of COVID-19 early in the pandemic, and contrasts in illness experiences between self and others enabled us to identify our first theme capturing the complexity of interviewees’ illness experiences and their inability to account for their illness or find similar others. We discussed findings in regular team meetings and recorded our analytic decision-making process with detailed notes and memos documenting our personal assumptions to limit biases and facilitate rigorous interpretation. Quotes from interview transcripts were used to illustrate each of the themes. Pseudonyms were used to distinguish between participants. Fig. 1 provides an illustration of our analytic process, including the initial production of codes, refinement of the coding framework, application of the coding framework to interview transcripts, and searching for themes through a review of coded excerpts.

Fig. 1.

Process of Codebook Development and Thematic Analysis

4. Results

We identified three overarching themes. The first (described in section 4.1) highlights the complex and unpredictable symptoms that comprised interviewees' illness experiences, the life-altering impacts of those experiences, and the uncertainty surrounding their illness following limited support and recognition from their social networks, and incomplete understandings of COVID-19 within the broader public and scientific community. The second theme (4.2) focuses on interviewees’ dismaying interactions within healthcare settings, including their frustration with doctors who were unable to treat their condition or who dismissed their experiences outright. The third theme (4.3) specifies the role that online communities played for persons with Long COVID, including the validation that members of these communities provided by recognizing their illness and validating their experience by sharing similar symptoms and healthcare interactions.

4.1. “These symptoms are so weird.” complex and unpredictable symptoms amid an evolving pandemic

Interviewees described Long COVID as a complex and unpredictable illness comprising a range of symptoms spanning multiple body systems that were sometimes general and non-specific. Symptoms varied in their type, timing, and severity, often appearing in cycles. Common symptoms included fatigue, brain fog, shortness of breath, and anxiety. Long COVID was contrasted with acute COVID-19 by sudden symptom relapses that followed periods of presumed improvement and complicated their perceptions of illness trajectory.

Interviewees expressed uncertainty over many facets of their illness, including the source of infection, the timing and course of symptoms, and its lasting effects on their health and functioning. Uncertainty was heightened early in the pandemic when access to testing was limited, understandings of COVID-19 and the mechanisms of spread were evolving, and public attention was largely focused on hospitalized persons with acute presentations of the disease. Interviewees expressed how much was left to be learned about COVID-19 and its medical treatment, and noted that misconceptions were prevalent. Limited knowledge of COVID-19 produced a disconnect between public understanding of the illness and how it was experienced by interviewees. For example, interviewees described early representations of COVID-19 as an illness with flu-like symptoms in which the range of outcomes included death, severe illness, or recovery within a few weeks. Persistent symptoms beyond a presumed recovery period and symptoms inconsistent with influenza led to confusion, frustration, desperation for answers, and concern for long-term health effects. One interviewee with Long COVID had unanswered questions about her illness and expressed desperation to know whether others had similar symptoms or experiences:

In March, we thought COVID was something that would either kill me in three weeks or I’d get over it … It was May when I started having long-term symptoms. It had gone on over a month [and was] worsening rather than getting better. I was getting desperate … I need to know. Am I the only one going through this or are there others? [Megan, Woman, 33]

Uncertainty was exacerbated by the absence of others who experienced a similar illness progression or symptoms. Interviewees contrasted their illness experience with that of friends' and family members,’ both in ways that their illness affected their bodies as well as in the length of their recovery period. One interviewee expressed a sense of isolation with their illness due to a lack of support and recognition from others, as well as frustration towards others who had no lingering symptoms:

Nobody else is having long-term symptoms. I'm the only one. I don't want to say they're calling me dramatic, but they're like, “I don't think that's related [to COVID-19].” I'm like, “No, it definitely is.” They're not really supportive. [Christina, Woman, 40]

Initial presentations of COVID-19 evolved into an illness characterized by persistent symptoms and lasting health effects that jeopardized interviewees' independence and challenged their sense of self. Long COVID impacted multiple aspects of interviewees’ lives, including work and daily tasks. Interviewees took leaves of absence from work and felt unable to make longer-term plans or do activities they once enjoyed. These changes represented a drastic shift for those who previously identified themselves as healthy and functional. One interviewee likened their illness experience, and ongoing efforts to cope with its health and functional consequences, to a stroke recovery:

It’s like when somebody has a stroke, and they get partially paralyzed. And they get through all this therapy, and they keep trying, and they're taking medicine and doing all that, that, you know, they might regain partial control, like learn to walk again, but their arm might not ever be working again. So they're able to heal part of their body but not all of it. That's kind of how life feels, is that, you know, I got through the sickness itself, but it's still an ongoing battle to fix everything that it messed up. [Karen, Woman, 40]

Long-haulers sought to address wide-ranging symptoms that were neither anticipated nor predicted by the state of knowledge about COVID-19 at the time they began experiencing their illness.

4.2. “Am I crazy?” frustration, dismissal, and gaslighting characterize healthcare interactions

The illness uncertainty described by many interviewees was connected to their interactions with healthcare professionals, who were often unable to diagnose and treat them. Interviewees expressed frustration with the medical uncertainty surrounding Long COVID, including the inability of healthcare professionals to provide answers to questions about their illness:

I just wanted somebody to give me some answers, basically, but they didn't have them. [Donna, Woman, 64]

Their symptoms, which were often non-specific and multi-system, combined with tests and instruments that produced negative results, made it difficult to narrow in on a diagnosis. Interviewees described being shuffled between specialists, who would run tests but fail to identify abnormalities. Diagnosis was also complicated by the lack of a formal naming convention and varying labels for Long COVID (e.g., post-viral syndrome/fatigue, autonomic dysfunction). One interviewee perceived that their Long COVID symptoms were taken less seriously by healthcare professionals:

They [healthcare professionals] said, “Okay, you know, there's nothing much we can do, because there's a lot of patients who have worse symptoms. So, you know, you take this back to your primary care, and then you go from there.” [Leela, Woman, 36]

This was perhaps due in part to Long COVID symptoms that were not commonly associated with acute COVID-19, especially early in the pandemic (e.g., brain fog, paresthesia).

Healthcare professionals who were described as supportive often focused on interviewees' quality of life and ability to perform social roles, even if they did not have all the answers or resources to address their concerns. Interviewees acknowledged that these healthcare professionals were engaging in symptom chasing rather than treating an underlying condition. Still, those healthcare professionals who listened to interviewees’ suggestions about tests and symptom management strategies and were familiar with COVID-19 symptoms and syndromes provided meaningful validation. One interviewee described their satisfaction with their treating physician based on the seriousness with which they took Long COVID symptoms as well their efforts to learn more about the condition by completing additional coursework and researching treatments:

The doctor that I'm seeing is really good … He seems to be taking stuff very seriously … And, you know, he had taken an extra course [on] post COVID [symptoms and syndromes], and is there a better inhaler, and stuff like that. [Kathy, Woman, 52]

These supportive interactions were contrasted with those involving dismissive healthcare professionals who viewed their symptoms as less concerning compared with those presenting with acute COVID-19. In several cases, symptoms presented by interviewees were labeled by doctors as psychogenic or rooted in pandemic-related anxiety. Without results from formal medical tests to validate their illness, interviewees felt unable to defend their illness. One interviewee expressed frustration with healthcare professionals who were perceived as dismissive and pushed back against medical evaluations attributing her Long COVID symptoms to pandemic-related anxiety.

There's a lot of dismissiveness … Every doctor I talked to brings up anxiety and it's like, “Okay, I am aware why you think this could be a thing. And I am aware that like, you know, it could play a role, but anxiety is not giving me a fever.” I thought, you know, like, it's just, it just was really frustrating. [Ashley, Woman, 28].

Several interviewees described a gaslighting phenomenon in which they felt mentally manipulated by healthcare professionals. Gaslighting has been defined as attempts by one actor within an intimate relationship to make the other seem or feel crazy (Sweet, 2019). Indeed, more than half of interviewees used this language to describe how they were met with dismissal and doubt when medical evaluations, tests and exams failed to identify recognizable abnormalities. These interactions produced a surreal social environment in which interviewees’ medical claims, notably those expressed by women, were dismissed and deemed non-credible (Fielding-Singh & Dmowska, 2022). One interviewee described:

What I was getting from the medical field [was] that I was crazy. [The] General Practitioner was like, “I don't know about this.” In the hospital, it would be like, “Well, there's nothing wrong with your lungs. There's nothing wrong with your heart.” And it kind of made me feel like, well, was it just in my head? It was like the medical field wasn't believing that I was really having this stuff. [Kelly, Woman, 56]

Gaslighting interactions with healthcare professionals led interviewees to question their symptoms and evaluate their level of sensitivity. One interviewee wondered if she was worrying excessively about her cardiovascular symptoms, drawing analogies between herself and someone with hypochondriasis:

You start to wonder, after so many people dismiss you, you start to wonder, what is real and what's not real? And, are you just being too sensitive? Like, you know, “Oh my gosh, my heartbeat, my heart fluttered. Oh, my gosh,” you know, it's made me become super hypochondriacal. [Susan, Woman, 57]

Another interviewee who described shortness of breath questioned whether there were other explanations for her illness, since she did not need to be placed on a respirator.

I started questioning … Am I crazy? Am I just really not? Because my breathing, it was just, it was like I would have to like, catch a breath. And sometimes my breathing pattern would be off, where I'd have to, like, stop and it was weird. It was hard to explain. I didn't have to be put on a respirator or anything. I almost felt like, gosh, maybe, you know, maybe there's just something else going on? [Donna, Woman, 64].

Lacking answers from healthcare professionals, interviewees found themselves ill and seeking out others with similar experiences.

4.3. “I'm not the only one out there.” online communities provided validation and support

Online communities for Long COVID, including Reddit forums, Facebook Groups, and Slack channels, provided platforms for interviewees to learn from others with similar symptoms and share their stories. Interviewees were drawn to online communities out of an effort to gather information about their illness and ask questions. Interviewees tended to have prior experience with the online platform they used to connect with others coping with Long COVID. In the case of Facebook users we interviewed, their awareness of online communities for Long COVID came about from within their own social networks, including referrals from family, friends, and healthcare professionals. One interviewee described how information they gained from a Facebook group of persons with Long COVID helped to reduce their uncertainty by knowing others were experiencing similar symptoms:

It was one of those things like we weren't ever, like, completely sure that this was COVID. We had to kind of piece it together … And it honestly wasn't until a couple months ago when I read an article that came across my Facebook feed about long-haul, and I was reading through the symptoms, and it was like, “Oh, my God.” Everything made sense at that point … I searched out the survivor groups on Facebook, and I joined, and started reading just people's stories and accounts. I was like, everything here is like what I've been going through. Now I have an answer. [Casey, Non-Binary, 40]

In addition to reducing uncertainty, the presence of others in online communities who presented with similar symptoms fostered a sense of validation through affirmation that symptoms were related to Long COVID rather than psychogenic illness or disorder. One interviewee described how his connections with others on Reddit provided information and helped him realize that he was “not crazy:”

At one point, I'm like, “What the hell is wrong with me? I don't understand.” I started to search online and I found people on Reddit. I was like, oh, okay, this is a thing. Like, I'm not crazy … It gave me information … It validated [my symptoms]. [Brian, Man, 48].

Another interviewee described how finding others with similar symptoms on Facebook helped to quell her anxiety by providing a sense of support and fostering connection with others:

A lot of [my anxiety] was feeling like, I don't know how long my symptoms are going to last. I'm feeling like I don't know anybody else who's experiencing similar symptoms … I started looking at the COVID Facebook posts and connecting with people who have similar symptoms … And I felt like that night, after I joined that COVID Facebook group, was the first night in a very long time that I didn't have that massive anxiety attack. It's definitely been very helpful to connect with people who have similar symptoms, especially when a lot is unknown about the virus … I just felt like it opened up a whole new channel of hope and support and resources. [Julia, Woman, 26]

One interviewee found comfort and support in knowing that she was not alone, but these feelings could not fully offset frustration with the uncertainty surrounding illness etiology and treatments.

It's just more supportive knowing that I'm not alone, like other people have the same symptoms and are going through the same thing. But there's no explanation of why it's happening or any guidance on how to make it stop. But I mean, it's comforting to know that it's not, I'm not like going crazy. I thought I was going crazy for a little bit. [Christina, Woman, 40].

Online communities provided an outlet for interviewees to voice frustration with medical gaslighting. These online interactions fostered a realization that interviewees were not crazy and had similarly complex health and symptom concerns as others. One interviewee described how online communities helped to compensate for medical uncertainty and gaslighting through the sharing of illness experiences and social support:

People sharing [their experiences in online communities] made us feel that what we were telling our doctors, who just looked at us with empty blank faces, made sense. And you, you would get a sense of validation that, “No, you're not crazy. And no, this isn't all in your head.” Getting so much negative treatment from people in the medical community is really degrading. It kind of hits your self esteem. … So it was like there was a sense of community, and what we weren't getting from the medical professionals, we were getting from each other. [Susan, Woman, 57]

Indeed, the collective voice of persons with Long COVID in online communities served to provide empowerment to a group that had experienced disempowerment through dismissive healthcare interactions and medical gaslighting. One interviewee, a practicing healthcare professional, reflected on how her awareness of gaslighting experiences among persons with Long COVID led her to critically evaluate her own actions towards patients and recognize that patients may continue to have challenges with their illness following an acute sickness. She described the moment that led to this realization:

I literally started crying because I was like, this is exactly what I'm experiencing, and there are so many people. And truthfully, as a provider, all I cared about prior to this was getting my patients through the acute infection, [so] that they wouldn't die. I was scared for them. I really did not give any thought as a provider about [what happens] afterwards. Not that I wouldn't listen to someone, but I didn't even think about what that would be, and now going through it, it gives me a whole different perspective of even how I would practice as a provider. [Melissa, Woman, 46]

While interviewees' comments regarding online communities were mostly positive and their interactions were overwhelmingly supportive, some took more critical views of these platforms. For instance, one interviewee suggested a lack of continuity in participation made it challenging to follow members over time and maintain conversations about their illness and symptom trajectories:

At first [the online community] was super helpful, but then it ended up being a lot of people, like introducing themselves for the first time and asking questions, and then never coming back. There's a lot of like, just, you know, new people coming and not- like there wasn't continuous conversation [Ashley, Woman, 28]

Other interviewees questioned the veracity of information shared in online communities, noting the uncertainty surrounding effective treatments for Long COVID and the potential of negative health consequences associated with following unverified medical advice:

People are telling other people to take medications, and, “Oh, do this, and take this supplement, and take that supplement.” When you start telling people to pound electrolytes, if they have a, you know, low GFR [glomerular filtration rate], you're going to damage their kidneys. You might want to not tell people to do this, or at least talk to their doctor before you tell them, “Oh, you're never going to get better, unless you do this.” Because you're going to cause people harm. [Susan, Woman, 57]

In summary, online communities served as important sources of validation, outlets for expressing frustrations, and spaces for learning about symptoms and symptom management. At a time when most people had limited face-to-face social interactions, these online communities were particularly significant.

5. Conclusions

This study describes the subjective illness experiences of persons with Long COVID– the long-term effects that result from infection with the virus that causes COVID-19 (CDC, 2022). Our findings highlight their experiences navigating complex and unpredictable symptoms amid significant uncertainty surrounding the causes and consequences of COVID-19. These results also indicate the often troubling experiences of persons with Long COVID in seeking recognition and treatment from healthcare professionals and the ways in which their interactions in online communities aided them in managing uncertainty. Interviewees described their illness through the prism of a diffuse set of symptoms that spanned multiple body systems months after an initial infection. These descriptions help to expand upon recent research that unpacks the ways in which an acute respiratory syndrome can manifest into a chronic illness with long-term health and social consequences (Higgins et al., 2021; Leviner, 2021).

Interviewees in our study had varying encounters with healthcare professionals when presenting with Long COVID symptoms, including some interactions that were described as supportive in aiding interviewees with finding treatments that led to improvements in their quality of life. However, several persons with Long COVID whom we interviewed described instances of medical gaslighting. Interviewees described how these encounters left them feeling crazy when their symptoms could not be verified with existing medical testing and diagnostics, and when doctors suggested “there's nothing wrong” or implied that the cause of their symptoms was pandemic-related depression or anxiety. These findings help to clarify the specific social processes within healthcare encounters that have left patients with Long COVID feeling isolated, unsupported, and frustrated (Kingstone et al., 2020; Taylor et al., 2021). Dismissal and disbelief among patients by healthcare professionals has been documented in contested illnesses, including chronic pain, myalgic encephalomyelitis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and fibromyalgia (Barker, 2008; Blease et al., 2017; McManimen et al., 2019; Newton et al., 2013). Indeed, interviews with Long COVID patients who were physicians themselves expressed concerns that they would be treated differently due to the overlap of their symptoms with contested illnesses, even avoiding disclosing certain symptoms for fear they would be dismissed (Garner, 2020; Nath, 2020; Taylor et al., 2021). This research parallels how interviewees described their distressing bodily symptoms being classified as psychosomatic, a consequence of pandemic-related anxiety, rather than as clinical sequelae of COVID-19.

Delegitimizing healthcare encounters described by patients with other chronic illnesses such as chronic fatigue syndrome are also attributed to the absence of observable disease or identifiable organic pathology and the outward appearance of normal functioning (Ware, 1992). Patients with medically unexplained physical symptoms describe experiencing clinical encounters characterized by disbelief, disrespect, marginalization, inappropriate psychological explanations, and damaging health advice (Lian & Robson, 2017). Their perceptions of dismissal and disbelief could stem from medical uncertainty among healthcare professionals who arrive at inconclusive diagnostic evaluations and rule out the most serious and life-threatening conditions (Han et al., 2021). Those with Long COVID who perceive their health status as uncertain and threatening (i.e. a novel and complex illness that cannot be accounted for by the healthcare system) may experience significant anxiety (Freeston et al., 2020). These findings are concerning given that illness uncertainty is positively associated with coping difficulty and negatively associated with coping efficacy in chronic illness (Johnson et al., 2006).

Perhaps owing to stay-at-home orders and recommendations for social distancing, online communities became popular forums for persons with COVID-19 to share their illness experiences and challenges with testing, diagnosis, and treatment. While online communities were platforms for those with acute and chronic presentations of COVID-19 to share their illness experiences, these sites were virtual spaces where people with Long COVID could engage in crowd-sourced medicine and collective uncertainty management (Thompson et al., 2021). Online communities, including those on Reddit and Facebook, were important outlets for our interviewees, especially when they perceived limited recognition and support, and even disbelief, from family and friends. Indeed, online communities provided outlets for people with Long COVID to share detailed accounts of their symptoms with others, interpret healthcare experiences, and collectively shape an understanding of their illness. These findings reinforce those of prior studies among help-seeking among persons with contested illness, which illustrate how self-doubt and alienation spurs involvement in support communities and aids in the affirmation of their illness experience as real rather than imagined (Barker, 2002, 2008). Interestingly, interviewees expressed similar points about their illness experiences, including those about illness uncertainty and medical gaslighting. One possibility is that participation in online communities shapes the discourses and narratives around Long COVID. Earlier research has noted the “echo chamber” quality of Long COVID online communities, where certain narratives about the illness experience are shared and promoted (Rushforth et al., 2021). It is possible that discourses around dismissive healthcare professionals and medical gaslighting get picked up and circulated within these communities. However, most interviewees indicated that they sought out online communities after healthcare interactions characterized by dismissiveness and medical gaslighting.

There are notable ways in which this research could be expanded upon. First, our study examined the perspectives of self-identified long-haulers, including their recounting of clinical interactions and experiences with COVID-19 diagnosis and testing. This approach lacks a ‘clinical witness’ to the diagnosis and treatment of persons with a complex illness about which little was known. Soliciting the perspectives of healthcare professionals towards the treatment of patients with Long COVID could help to elucidate how they managed medical uncertainty and assisted patients coping with unexplained symptoms. Our work also suggests directions for studying long-term health and quality of life outcomes. Several interviewees discussed challenges in maintaining full-time work or returning to work, suggesting a need for a more formal investigation of employment and disability policies related to Long COVID.

We intentionally sampled interviewees from online communities to understand how those communities impacted members' experiences. This approach likely excluded people with limited internet access or health literacy. Further, we may have missed other persons coping with long-term effects from COVID-19 who did not see their health issues as being connected to Long COVID. While qualitative interview methods can aid in uncovering participants’ experiences with online communities, including their motivations for joining and forming connections with others who have similar illness, other methods such as online ethnography, or blended approaches that combine offline interviewing with online ethnographic observation, could aid in further understanding how individual experiences are embedded within larger contexts of a social movement aimed at fostering recognition and support for persons with Long COVID (Hine, 2017). Additionally, online ethnographic methods may afford participants greater flexibility to interact with researchers on their own time, which may be important given the significant obstacles that Long COVID presents to daily functioning and participation in work and relationship roles.

Lastly, our research included limited representation among men, older adults, races and ethnicities other than non-Hispanic White, and those with lower socioeconomic status. Additional research on Long COVID is needed to increase representation across these groups and ensure their illness experiences are captured within this literature. Further, the underrepresentation of certain groups within our interview sample may have implications for the themes we identified in our analysis. For instance, case studies examining gaslighting often feature men as gaslighters and women as targets of gaslighting (Sweet, 2019). Studies of medical gaslighting, specifically, have highlighted how unequal power dynamics and histories of discrimination within healthcare encounters produce contexts in which the health concerns of women are dismissed or invalidated by medical professionals (Sebring, 2021). Women have been significantly more likely than men to report certain symptoms of Long COVID, including headaches and myalgia, symptoms that are often contested and elude medicine's pathological gaze (Barker, 2009; Taquet et al., 2021). Additionally, researchers have documented disparities in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality by age, race/ethnicity and sex across earlier and later pandemic stages (Danielsen et al., 2022; Elo et al., 2022; Feldman & Bassett, 2021). Men and minorities may be less represented in the Long COVID online communities we studied. Other forms of social media or data collection sites such as recovery and treatment clinics for persons with Long COVID could be targeted to produce a more diverse sample. As research continues to inform our understanding of the epidemiology of Long COVID, we will gain insight into socio-demographic groups suffering from this illness that warrant further study.

Together, our findings have several practical implications for the support and care of Long COVID. First, referring people who report lingering symptoms and/or health effects from COVID-19 to specialty centers and recovery clinics could help to improve their assessment and treatment within the healthcare system. Previous research has highlighted how strong relationships with healthcare professionals are especially important in clinical encounters where patients present with symptoms that are not easily detected, explained, and managed through existing medical knowledge and technologies (Lian & Robson, 2017). Second, connecting persons with Long COVID to online communities that are patient-led and moderated to prohibit misinformation and unsolicited medical advice could lead to some measure of relief for those with persistent symptoms in knowing that others have had similar experiences. Educating healthcare providers on strategies to address medical uncertainty and to improve patient engagement is needed to reduce instances of medical gaslighting and its negative consequences for individuals. Lastly, but perhaps most importantly, continued efforts are needed to amplify the voices of persons with Long COVID and support them through research, education, and advocacy. This includes following them over the course of their illness and recovery, listening to their narratives, and understanding how they manage symptoms.

Ethics statement

This study was determined to be exempt from review by the Institutional Review Board at Appalachian State University (#21–0068). During our recruitment of study participants, we solicited the permission of administrators who oversaw each of the online communities where we posted a message about our study and information for how to get in contact with one of our investigators for an interview. Our recruitment message posted to each online community shared information about the purpose of the study, topics to be addressed in an interview, the estimated amount of time to complete an interview, and compensation ($25). Informed consent was obtained from each study participant prior to the start of the interview, during which time the participant was made to know that any identifiable information would remain confidential to the research team, the interview would be audio recorded and transcribed verbatim (removing any identifiable information), and that their participation was completely voluntary and they could end the interview at any time. During the analytic process, the research team assigned pseudonyms to each interviewee for the purpose of uniquely identifying illustrative quotes for each theme.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Semi-Structured Qualitative Interview Guide

I'm going to ask you some questions now about your experiences when you became sick with COVID-19, what it was like when you started having symptoms, your meetings with doctors and other healthcare professionals, and your communications with other people who tested positive for COVID-19 on online communities of support, like Reddit, Facebook, Slack, or Twitter.

-

1.Can you walk me through what happened at the time when you first became sick with COVID-19?

-

a.When did you first suspect that you had become infected with COVID-19?

-

b.What did you know about COVID-19 at the time when you first became sick?

-

c.Did others in your network (family or friends) become sick with COVID-19?

-

d.What were some of your first symptoms? Were you concerned about them?

-

e.How did your symptoms affect your day-to-day life and routines?

-

f.Which symptoms were most difficult for you to cope with?

-

g.What was your health like before you became infected with COVID-19?

-

a.

-

2.Can you tell me about what it was like for you to get tested for COVID-19?

-

a.Was there a testing location close to where you lived?

-

b.Was it easy to get to? Did you have to wait long to take a test?

-

c.How long did you have to wait for your test results to come back?

-

d.Were the testing results consistent with what you expected them to be?

-

e.Did you take a test for COVID antibodies? What was the result of that test?

-

a.

-

3.Did you share your concerns about your long-lasting symptoms of COVID-19 with your doctor(s) or other healthcare professionals?

-

a.How did they respond to you when you shared your symptom experiences?

-

b.How did the way they responded to you make you feel?

-

a.

-

4.Did the healthcare professional take certain symptoms more seriously than others?

-

a.How long after you first suspected you had COVID-19 did you start to be concerned that you had long-lasting symptoms from the virus?

-

b.At that time, were you familiar with the group of people who called themselves “long haulers” or used the term “long covid” to label their experiences with the virus. How did you learn about this group of people with lingering COVID-19 symptoms? What did you learn about this group?

-

c.What about your experience led you to consider yourself a “long-hauler”?

-

d.How have the long-lasting (lingering) symptoms continued to impact your daily life?

-

a.

-

5.What made you want to use social media to connect with other long-haulers?

-

a.Which social media platform(s) did you use to connect with other people with lingering symptoms from COVID-19?

-

b.What were you hoping to gain from participating in the online community?

-

c.Did you share your own experience with this online community by posting your story about having long-lasting symptoms of COVID-19?

-

d.How did they respond to you when you shared your symptom experiences?

-

e.What steps did they take (or not take) to help you manage your symptoms?

-

a.

-

6.How did you find the online community (e.g., Reddit, Twitter, Facebook) of support for people with long-lasting COVID-19 symptoms?

-

a.When you found the [online community], were you aware that a group existed of persons with prolonged symptoms (i.e. “long covid” or “long-haulers”)?

-

b.Why did you decide to share your experience with this community?

-

c.What information did you decide to share about your experience with COVID-19?

-

a.

-

7.Did you find support from other persons with prolonged symptoms of COVID-19 in the [online community]?

-

a.What types of support did other people in the [online community] provide to you?

-

b.Did you try to provide support to other people who posted about their prolonged COVID-19 symptoms? What types of support did you offer to them?

-

c.Do you see yourself continuing to participate in [the online community]?

-

a.

-

8.

How would you describe your experience as a long-hauler to someone who was unfamiliar with the lasting effects of COVID-19 infection on people?

-

9.How has your experience as a long-hauler changed the way you view yourself and your health? Has this experience changed your identity and sense of self?

-

a.Has it impacted your family life or identity within your family?

-

b.Has it impacted your spiritual practices or beliefs?

-

c.Has it impacted your work?

-

d.Have you needed someone else to help you do things around the house or take care of you because of your symptoms?

-

a.

References

- Aiyegbusi O.L., Hughes S.E., Turner G., Rivera S.C., McMullan C., Chandan J.S., Haroon S., Price G., Davies E.H., Nirantharakumar K., Sapey E., Calvert M.J., TLC Study Group Symptoms, complications and management of long COVID: A review. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 2021;114:428–442. doi: 10.1177/01410768211032850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker K. Self-help literature and the making of an illness identity: The case of fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) Social Problems. 2002;49:279–300. [Google Scholar]

- Barker K.K. Electronic support groups, patient-consumers, and medicalization: The case of contested illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49:20–36. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker K. Temple University Press; 2009. The fibromyalgia story: Medical authority and women's worlds of pain. [Google Scholar]

- Baz S., Fang C., Carpentieri J.D., Sheard L. Understanding the lived experience of long covid: A rapid literature review. 2021. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357097275 [WWW Document]. URL.

- Blease C., Carel H., Geraghty K. Epistemic injustice in healthcare encounters: Evidence from chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Medical Ethics. 2017;43:549–557. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2016-103691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D.A., O'Brien K.K. Conceptualising Long COVID as an episodic health condition. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burges Watson D.L., Campbell M., Hopkins C., Smith B., Kelly C., Deary V. Altered smell and taste: Anosmia, parosmia and the impact of long Covid-19. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M. The sociology of chronic illness: A review of research and prospects. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1991;13:451–468. [Google Scholar]

- Callan C., Ladds E., Husain L., Pattinson K., Greenhalgh T. 2021. I can't cope with multiple inputs”: Qualitative study of the lived experience of “brain fog” after Covid-19. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callard F., Perego E. How and why patients made Long Covid. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;268 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carfì A., Bernabei R., Landi F. Persistent symptoms in patients after acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2020. Gemelli against COVID-19 post-acute care study group. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC . 2022. Long COVID or post-COVID conditions.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/long-term-effects/index.html [WWW Document]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. URL. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C., Zhang D., Dang D., Geng J., Zhu P., Yuan M., Liang R., Yang H., Jin Y., Xie J., Chen S., Duan G. The incubation period of COVID-19: A global meta-analysis of 53 studies and a Chinese observation study of 11 545 patients. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10:119. doi: 10.1186/s40249-021-00901-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A.E., Shim J.K., Mamo L., Fosket J.R., Fishman J.R. Biomedicalization: Technoscientific transformations of health, illness, and U.S. Biomedicine. American Sociological Review. 2003;68:161–194. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P., Bandini J., Vasquez A. Illness and the internet: From private to public experience. Health. 2016;20:22–32. doi: 10.1177/1363459315611941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad P., Barker K.K. The social construction of illness: Key insights and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51(Suppl):S67–S79. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID Symptom Study How long does COVID-19 last? 2020. https://covid.joinzoe.com/post/covid-long-term [WWW Document]. URL.

- COVID-19 Body Politic Slack Group . 2020. What does COVID-19 recovery actually look like? An analysis of the prolonged COVID-19 symptoms survey by patient-led research team. [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen A.C., Lee K.M., Boulicault M., Rushovich T., Gompers A., Tarrant A., Reiches M., Shattuck-Heidorn H., Miratrix L.W., Richardson S.S. Sex disparities in COVID-19 outcomes in the United States: Quantifying and contextualizing variation. Social Science & Medicine. 2022;294 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis H.E., Assaf G.S., McCorkell L., Wei H., Low R.J., Re’em Y., Redfield S., Austin J.P., Akrami A. Characterizing long COVID in an international cohort: 7 months of symptoms and their impact. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;38 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day H.L.S. Exploring online peer support groups for adults experiencing long COVID in the United Kingdom: Qualitative interview study. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2022;24 doi: 10.2196/37674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Cruz R.J., Currier A.W., Sampson V.B. Laboratory testing methods for novel severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2020;8:468. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg L. Disease and illness. Distinctions between professional and popular ideas of sickness. Culture Medicine and Psychiatry. 1977;1:9–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00114808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo I.T., Luck A., Stokes A.C., Hempstead K., Xie W., Preston S.H. Evaluation of age patterns of COVID-19 mortality by race and ethnicity from March 2020 to october 2021 in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2022;5 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.12686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman J.M., Bassett M.T. Variation in COVID-19 mortality in the US by race and ethnicity and educational attainment. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.35967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding-Singh P., Dmowska A. Obstetric gaslighting and the denial of mothers' realities. Social Science & Medicine. 2022;301 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeston M., Tiplady A., Mawn L., Bottesi G., Thwaites S. Towards a model of uncertainty distress in the context of Coronavirus (COVID-19) Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2020;13:e31. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X2000029X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner P. 2020. Paul Garner: Covid-19 at 14 weeks—phantom speed cameras, unknown limits.https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/06/23/paul-garner-covid-19-at-14-weeks-phantom-speed-cameras-unknown-limits-and-harsh-penalties/ and harsh penalties [WWW Document]. BMJ Opinion. URL. [Google Scholar]

- Godlee F. Living with covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3392. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorna R., MacDermott N., Rayner C., O'Hara M., Evans S., Agyen L., Nutland W., Rogers N., Hastie C. Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience. Lancet. 2021;397:455–457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32705-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han P.K.J., Strout T.D., Gutheil C., Germann C., King B., Ofstad E., Gulbrandsen P., Trowbridge R. How physicians manage medical uncertainty: A qualitative study and conceptual taxonomy. Medical Decision Making. 2021;41:275–291. doi: 10.1177/0272989X21992340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton P.M. The covid-19 vaccine-development multiverse. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020;383:1986–1988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2025111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins V., Sohaei D., Diamandis E.P., Prassas I. COVID-19: From an acute to chronic disease? Potential long-term health consequences. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 2021;58:297–310. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2020.1860895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hine . The SAGE handbook of online research methods; 2017. Ethnographies of online communities and social media: Modes, varieties, affordances. [Google Scholar]

- Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., Zhang L., Fan G., Xu J., Gu X., Cheng Z., Yu T., Xia J., Wei Y., Wu W., Xie X., Yin W., Li H., Liu M.…Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X., Lian J.-S., Hu J.-H., Gao J., Zheng L., Zhang Y.-M., Hao S.-R., Jia H.-Y., Cai H., Zhang X.-L., Yu G.-D., Xu K.-J., Wang X.-Y., Gu J.-Q., Zhang S.-Y., Ye C.-Y., Jin C.-L., Lu Y.-F., Yu X.…Yang Y. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of coronavirus-infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut. 2020;69:1002–1009. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center 2021. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/about About Us [WWW Document]. The Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. URL.

- Johnson L.M., Zautra A.J., Davis M.C. The role of illness uncertainty on coping with fibromyalgia symptoms. Health Psychology. 2006;25:696–703. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.6.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingod N., Cleal B., Wahlberg A., Husted G.R. Online peer-to-peer communities in the daily lives of people with chronic illness: A qualitative systematic review. Qualitative Health Research. 2017;27:89–99. doi: 10.1177/1049732316680203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingstone T., Taylor A.K., O'Donnell C.A., Atherton H., Blane D.N., Chew-Graham C.A. Finding the “right” GP: A qualitative study of the experiences of people with long-COVID. BJGP Open. 2020;4 doi: 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer S.A., Grantz K.H., Bi Q., Jones F.K., Zheng Q., Meredith H.R., Azman A.S., Reich N.G., Lessler J. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: Estimation and application. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020 doi: 10.7326/m20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leviner S. Recognizing the clinical sequelae of COVID-19 in adults: COVID-19 long-haulers. The Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2021;17:946–949. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian O.S., Robson C. It's incredible how much I’ve had to fight.” Negotiating medical uncertainty in clinical encounters. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being. 2017;12 doi: 10.1080/17482631.2017.1392219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato A., de Filippis C. Clinical presentation of COVID-19: A systematic review focusing on upper airway symptoms. Ear, Nose, & Throat Journal. 2020;99:569–576. doi: 10.1177/0145561320920762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahase E. Covid-19: What do we know about “long covid”. BMJ. 2020;370:m2815. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandavilli A. 2021. The U.S. Is getting a crash course in scientific uncertainty. The New York Times. [Google Scholar]

- Maslen S., Lupton D. Keeping it real”: women's enactments of lay health knowledges and expertise on Facebook. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2019;41:1637–1651. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManimen S., McClellan D., Stoothoff J., Gleason K., Jason L.A. Dismissing chronic illness: A qualitative analysis of negative health care experiences. Health Care for Women International. 2019;40:241–258. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2018.1521811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishel M.H. Uncertainty in illness. Image - the Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1988;20:225–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mol A., Law J. Embodied action, enacted bodies: The example of hypoglycaemia. Body & Society. 2004;10:43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer M.W. 2020. https://elemental.medium.com/gaslighted-by-the-medical-system-the-covid-19-patients-left-behind-3ee0d3419197 Gaslighted by the Medical System”: The Covid-19 Patients Left Behind [WWW Document]. Elemental. URL.

- Nath A. Long-haul COVID. Neurology. 2020;95:559–560. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton B.J., Southall J.L., Raphael J.H., Ashford R.L., LeMarchand K. A narrative review of the impact of disbelief in chronic pain. Pain Management Nursing. 2013;14:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell L.S., Norris J.M., White D.E., Moules N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2017;16 [Google Scholar]

- Perego E., Callard F. 2021. Patient-made Long Covid changed COVID-19 (and the production of science. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perego E., Callard F., Stras L., Melville-Johannesson B., Pope R., Alwan N. BMJ Opinion; 2020. Why we need to keep using the patient made term “Long Covid. [Google Scholar]

- Pierret J. The illness experience: State of knowledge and perspectives for research. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2003;25:4–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.t01-1-00337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushforth A., Ladds E., Wieringa S., Taylor S., Husain L., Greenhalgh T. Long Covid--The illness narratives. Social Science & Medicine. 2021;286 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebring J.C.H. Towards a sociological understanding of medical gaslighting in western health care. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2021;43:1951–1964. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick L., Guntuku S.C., Klinger E.V., Pelullo A., McCalpin H., Merchant R.M. The role of digital health technologies in COVID-19 surveillance and recovery: A specific case of long haulers. International Review of Psychiatry. 2021;33:412–423. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2020.1854195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweet P.L. The sociology of gaslighting. American Sociological Review. 2019;84:851–875. [Google Scholar]

- Taquet M., Dercon Q., Luciano S., Geddes J.R., Husain M., Harrison P.J. Incidence, co-occurrence, and evolution of long-COVID features: A 6-month retrospective cohort study of 273,618 survivors of COVID-19. PLoS Medicine. 2021;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A.K., Kingstone T., Briggs T.A., O'Donnell C.A., Atherton H., Blane D.N., Chew-Graham C.A. Reluctant pioneer”: A qualitative study of doctors' experiences as patients with long covid. Health Expectations. 2021;24:833–842. doi: 10.1111/hex.13223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenforde M.W., Kim S.S., Lindsell C.J., Billig Rose E., Shapiro N.I., Files D.C., Gibbs K.W., Erickson H.L., Steingrub J.S., Smithline H.A., Gong M.N., Aboodi M.S., Exline M.C., Henning D.J., Wilson J.G., Khan A., Qadir N., Brown S.M., Peltan I.D.…Feldstein L.R. IVY network investigators, CDC COVID-19 response team, IVY network investigators. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:993–998. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1. Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network - United States, March-June 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C.M., Rhidenour K.B., Blackburn K.G., Barrett A.K., Babu S. Using crowdsourced medicine to manage uncertainty on Reddit: The case of COVID-19 long-haulers. Patient Education and Counseling. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware N.C. Suffering and the social construction of illness: The delegitimation of illness experience in chronic fatigue syndrome. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 1992;6:347–361. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z., Xiang J., Wang Y., Song B., Gu X., Guan L., Wei Y., Li H., Wu X., Xu J., Tu S., Zhang Y., Chen H., Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]