Abstract

Accurate postpartum depression screening measures are needed to identify mothers with depressive symptoms both in the postpartum period and beyond. Because it had not been tested beyond the immediate postpartum period, the reliability and validity of the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS) and its sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value for diagnoses of major depressive disorder (MDD) were assessed in a diverse community sample of 238 mothers of 4- to 15-month-old infants. Mothers (N = 238; M age = 30.2, SD = 5.3) attended a lab session and completed the PDSS, the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), and a structured clinical interview (SCID) to diagnose MDD. The reliability, validity, specificity, sensitivity, and predictive value of the PDSS to identify maternal depression were assessed. Confirmatory factor analysis supported the construct validity of five but not seven content subscales. The PDSS total and subscale scores demonstrated acceptable to high reliability (α = 0.68–0.95). Discriminant function analysis showed the scale correctly provided diagnostic classification at a rate higher than chance alone. Sensitivity and specificity for major depressive disorder (MDD) diagnosis were good and comparable to those of the BDI-II. Even in mothers who were somewhat more diverse and had older infants than those in the original normative study, the PDSS appears to be a psychometrically sound screener for identifying depressed mothers in the 15 months after childbirth.

Keywords: depression, emotional states, instrument development and validation, statistical test development

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Considered the most common complication of childbirth, postpartum depression (PPD) is a mood disorder affecting an estimated 13–19% of new mothers annually (O’Hara & McCabe, 2013). Despite the reported high incidence of PPD, many women go undiagnosed and are consequently untreated (Hanna, Jarman, & Savage, 2004). This may be due in part to new mothers’ fears of stigmatization if they report sadness after giving birth. In addition, real or imagined pressure to express joy, lack of awareness, low energy, and lack of motivation may contribute to maternal under-reporting of PPD symptomatology (O’Hara, Stuart, Gorman, & Wenzel, 2000). Without treatment, PPD can have long-term negative physical and mental sequelae (Hanusa, Scholle, Haskett, Spadaro, & Wisner, 2008), and the adverse effects of PPD may reach beyond maternal health to affect infant development and learning (Forman et al., 2007; Kaplan, Danko, Cejka, & Everhart, 2015; Sohr-Preston & Scaramella, 2006). This underscores the importance of early screening, detection, and treatment (Georgiopoulos, Bryan, Wollan, & Yawn, 2001).

Although measures of depression such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996) have been validated for the detection of PPD (Beck & Gable, 2000), a measure designed specifically to detect PPD may be more accurate (Bennett, Einarson, Taddio, Koren, & Einarson, 2004). One such measure is the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale (PDSS; Beck & Gable, 2001a, 2002). Unlike other frequently used scales, the PDSS was developed using qualitative research into the specific underpinnings of PPD, recognizing the limitations of detection of postpartum depression with current scales (Beck, 2002; Gjerdingen & Yawn, 2007). For example, fatigue, sleep disturbance, and weight gain or loss may be symptoms of depression in adults in general but have different significance in postpartum women (Floyd et al., 2007). Further, although PPD has been defined as meeting criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) within 4 weeks of delivering a child (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000), prevalence estimates suggest that 12–15% of mothers continue to meet criteria for MDD 6–12 months postpartum, with as many as 30% mothers who are diagnosed with depression in the immediate postpartum period still meeting criteria 2 years after giving birth (Goodman, 2004). Thus, screening for depression beyond the initial postpartum period is important, as mothers with positive PDSS screening scores could be referred for further assessment and treatment of depressive symptoms.

1.1 |. Purpose

This study was designed to explore the efficacy of the PDSS, developed for use in the first months after childbirth, as a screening tool for the detection of depression beyond the immediate postpartum period in a racially and ethnically diverse sample of mothers. The aims of the present study were (i) to test the psychometric properties of the PDSS in a population beyond the immediate postpartum period, and (ii) to evaluate the validity of the qualitatively-based and postpartum-specific PDSS in comparison to the gold standard for general depression screening, the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), for predicting Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) diagnoses of MDD in the postpartum population.

2 |. METHOD

2.1 |. Participants

Participants were recruited through advertisements placed in Colorado Parent Magazine and at Early Head Start centers, as part of a larger study aimed at looking at the effects of maternal depression on infant learning (Kaplan, Danko, Diaz, & Kalinka, 2011). Mothers were included in the study if they had an infant between the ages of 4 and 15 months. Of the 245 mothers who completed the PDSS, 238 also provided demographic data, completed the BDI-II, and participated in the SCID. Construct validity and construct reliability were determined using all available data (N = 245), whereas analyses for concurrent validity, sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value used data from 238 participants for whom BDI-II was also available.

Table 1 presents demographic and PDSS and BDI-II diagnostic information for the sample. Mothers’ ages ranged from 16 to 41 years, with a mean age of 30. Infant age ranged from 138 to 459 days and averaged slightly under 1 year. Demographic characteristics (race and ethnicity, age) for this sample were similar to those from the most recent US Census for the general population of the City and County of Denver (US Census Bureau, 2010).

TABLE 1.

Demographic and diagnostic characteristics of sample

| PDSS classification |

BDI-II classification |

SCID classification |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Overall sample, N = 238 | Normal adjustment (PDSS < 60) n = 85 | Significant symptoms (PDSS 60–79) n = 57 | Positive screen (PDSS ≥ 80) n = 96 | Non-Elevated (BDI-II < 14) n = 142 | Elevated (BDI ≥ 14) n = 96 | NDEP (SCID) n = 202 | DEP (SCID) n = 36 |

| Infant gender (F), n (%) | 113 (47%) | 44 (52%) | 25 (44%) | 44 (45%) | 71 (50%) | 42 (43%) | 99 (49%) | 14 (39%) |

| Age of mother (years) | 30.2 (5.3) | 30.6 (4.9) | 30.0 (5.0) | 30.1 (5.8) | 30.6 (4.9) | 29.7 (5.8) | 30.4 (5.3) | 29.6 (5.4) |

| Age of infant (days) | 348.1 (52.3) | 351.0 (47.6) | 343.7 (58.5) | 349.6 (53.9) | 348.6 (52.5) | 347.4 (53.5) | 349.0 (52.6) | 342.4 (54.4) |

| Infant ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||||

| White | 161 (68%) | 59 (69%) | 39 (69%) | 63 (66%) | 102 (72%) | 59 (62%) | 143 (71%) | 18 (51%) |

| Latino | 41 (17%) | 17 (20%) | 6 (11%) | 18 (19%) | 22 (15%) | 19 (20%) | 30 (15%) | 11 (32%) |

| African-American | 22 (9%) | 6 (7%) | 7 (12%) | 9 (10%) | 10 (7%) | 12 (13%) | 17 (8%) | 5 (15%) |

| Asian | 10 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (7%) | 3 (3%) | 7 (5%) | 3 (3%) | 8 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| Native American | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Marital status, n (%) | * | * | * | |||||

| Married | 180 (76%) | 73 (86%) | 39 (68%) | 68 (71%) | 25 (18%) | 33 (34%) | 162 (80%) | 18 (50%) |

| Not married | 58 (24%) | 12 (14%) | 18 (32%) | 28 (29%) | 117 (82%) | 63 (66%) | 40 (20%) | 18 (50%) |

| Mother’s education, n (%) | n = 218 | * | * | |||||

| Less than high school | 9 (4%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (4%) | 6 (7%) | 4 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 5 (3%) | 4 (13%) |

| High school | 67 (28%) | 22 (28%) | 14 (26%) | 31 (37%) | 32 (24%) | 35 (40%) | 55 (29%) | 12 (40%) |

| 2-year degree | 25 (11%) | 8 (10%) | 8 (14%) | 9 (11%) | 24 (10%) | 12 (14%) | 20 (11%) | 5 (17%) |

| 4-year degree | 78 (33%) | 27 (33%) | 22 (40%) | 29 (35%) | 10 (38%) | 28 (32%) | 70 (37%) | 8 (27%) |

| Graduate degree | 39 (16%) | 22 (28%) | 9 (16%) | 8 (10%) | 32 (24%) | 7 (8%) | 38 (20%) | 1 (3%) |

| Family income, n (%) | n = 223 | * | * | |||||

| ≤$25k | 55 (23%) | 13 (16%) | 13 (23%) | 29 (34%) | 24 (18%) | 31 (35%) | 41 (21%) | 14 (47%) |

| $25,001–$50,000 | 66 (28%) | 27 (33%) | 17 (20%) | 22 (26%) | 40 (30%) | 26 (30%) | 56 (29%) | 10 (33%) |

| >$50,000 | 102 (43%) | 42 (51%) | 26 (47%) | 34 (40%) | 71 (52%) | 31 (35%) | 96 (50%) | 6 (20%) |

| Number of children | 1.9 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) | 1.9 (0.9) | 2.0 (1.1) | 1.7 (1.0) | 2.0 (1.0) * | 1.8 (0.9) | 2.4 (1.2) * |

| PDSS score | 74.8 (29.5) | 44.6 (7.1) | 70.4 (5.6) | 104.1 (20.4) * | 59.3 (19.8) | 97.7 (26.5) * | 67.4 (23.7) | 115.9 (25.0) * |

| BDI-II score | 12.9 (10.9) | 5.7 (5.6) | 11.1 (6.4) | 20.4 (11.8) * | 6.1 (3.8) | 23.0 (10.1) * | 10.1 (7.6) | 28.3 (13.4) * |

| GAF rating | 75.1 (9.6) | 79.4 (7.7) | 76.8 (7.5) | 69.7 (10.1) * | 78.9 (7.5) | 69.6 (9.7) * | 76.7 (8.4) | 62.1 (9.0) * |

PDSS, postpartum depression screening scale; BDI-II, Beck depression inventory-11; SCID, structured clinical interview for DSM-IV. Column definitions are means and standard deviations (SD) except where noted (as n [%]) based on PDSS total score, BDI-II total score, and SCID interview, respectively. NDEP, not diagnosed with current major depression, and includes mothers who are not depressed and those diagnosed with depression in partial or full remission. DEP, current major depression diagnosis only. GAF, general assessment of functioning based on SCID. Total N = 238 except where missing data are noted.

p < .05.

There were no differences in frequency of PDSS or BDI-II category and depression diagnosis based on infant age, maternal age, and infant ethnicity. However, mothers with lower household income (≤$25,000/ year) were more likely to have positive BDI-II scores (χ2 [2] = 8.4, p = .02) and were more likely to be classified as depressed by the SCID (χ2 [2] = 14.2, p < .001). Mothers with higher education (some college or college degrees) were less likely to be classified as depressed by the SCID (χ2 [4] = 14.8, p = .005) and were less likely to have positive BDI-II screens (χ2 [4] = 12.6, p = .01). Unmarried mothers were more likely than married mothers to be classified as depressed by the SCID (χ2 [4] = 15.5, p < .001) and were more likely to be positively screened as depressed by the PDSS (χ2 [1] = 6.6, p = .04) and the BDI-II (χ2 [2] = 11.6, p < .001. Mothers with more children were more likely to be categorized as depressed by the SCID (t [34] = −2.51, p = .02) and to have a positive BDI-II screen (t [221] = −2.33, p = .02).

1.2 |. Measures

2.2.1 |. PDSS

The PDSS is a 35-item self-report Likert-type screening tool that has 7 subscales of distress and impairment related to PPD: Sleeping/Eating Disturbances, Anxiety/Insecurity, Emotional Lability, Cognitive Impairment, Loss of Self, Guilt/Shame, and Contemplating Harming Oneself (Beck & Gable, 2000). Participants rate the extent to which they have been feeling each symptom over the past 2 weeks on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). All items are summed for a total score, and items within each subscale are summed for subscale scores. The total score ranges from 5 to 175, and higher scores correspond to greater postpartum depression symptoms.

Initial psychometric studies provided evidence that the PDSS scores demonstrate content validity, reliability, and high sensitivity and specificity for a MDD diagnosis (Beck & Gable, 2001a,b). The sensitivity and specificity of the PDSS to detect an episode of MDD has been reported to be comparable with that of the SCID (Hanusa et al., 2008), and more accurate than the BDI-II in detecting major and minor depression at 12 weeks postpartum (Beck & Gable, 2001b).

More recently, the construct validity of the PDSS has been examined in mothers of infants in the NICU, and a 5-subscale structure was determined to be a better fit to the data (Blucker et al., 2014). Blucker et al. (2014) found that combining the Anxiety/Insecurity, Emotional Lability, and Cognitive Impairment subscales into one subscale better represented their data. In their data, the internal consistency of the total score was high (α = 0.95).

2.2.2 |. BDI-II

The BDI-II is composed of 21 self-report items used to identify and measure the severity of depressive symptoms in the following areas: Sadness, Past Failure, Self-Dislike, Change in Sleeping Pattern, and Change in Appetite. Participants rate the severity of each symptom on a scale from 0 to 3, where 0 generally corresponds to not having symptoms and 3 corresponds to having severe depressive symptoms. Items are summed for a total score. The total score ranges from 0 to 63, with higher scores corresponding to greater depressive symptoms. Previous research has shown that the BDI demonstrates high internal consistency (α = 0.90; Wang & Gorenstein, 2013). Although sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value of the BDI-II for screening of depression was shown to be adequate in general populations (Beck et al., 1996), it was not specifically developed for PPD.

2.2.3 |. SCID

The SCID (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1996) is a semi-structured diagnostic exam that allows trained interviewers to arrive at clinical diagnoses based on DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. Interviewers ask a series of adaptive questions that address both current and past psychiatric symptoms. The adaptive questions mirror psychiatric diagnostic criteria in the DSM-IV. Mothers grouped in the “depressed” group had a diagnosis of MDD or dysthymia based on DSM-IV Axis-I depressive-disorder criteria, while all others were grouped as “non-depressed.”

2.3 |. Procedure and data analysis

Mothers attended an in-person lab session and completed the PDSS and the BDI-II. Mothers completed a variety of demographic and psychodiagnostic questionnaires and were interviewed using the SCID-IV.

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (SPSS Inc., 2016) and Mplus version 7.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2013). Descriptive statistics were analyzed using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables.

2.3.1 |. Construct validity

Construct validity of the PDSS was supported by examining inter-subscale correlations and full scale and subscale correlations and conducting confirmatory factor analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis was first conducted by defining the seven subscales and allowing the five items for each subscale to load on the appropriate subscale (the same model as in the original psychometric study conducted by Beck & Gable, 2000). The confirmatory factor analysis was then repeated using a five-subscale solution (as previously conducted by Blucker et al., 2014). Models were estimated using a maximum likelihood estimation method and full information maximum likelihood to account for any missing data. Overall model fit was assessed using Hu and Bentler’s (1999) recommendations for assessing model fit, including the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; value ≤.08 considered acceptable), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI; value ≥0.95), and standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR; value ≤.08). The TLI was chosen to examine fit because it is a more stringent absolute fit index than the comparative fit index (CFI), as it penalizes for adding more parameters.

2.3.2 |. Construct reliability

Construct reliability was estimated using Cronbach’s coefficient α (Cronbach & Gleser, 1957). Nunnally and Bernstein (1994) recommend using 0.70 as a minimum α for measures defining emotional constructs.

2.3.3 |. Concurrent validity

Concurrent validity for the PDSS was examined by correlation with the BDI-II. Concurrent validity was also supported by discriminant function analysis to determine the utility of the PDSS for correctly classifying depressed versus non-depressed mothers.

2.3.4 |. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for both the PDSS and BDI-II was examined by constructing Receiver Operator Curves (ROC) to determine the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value of the PDSS and BDI-II over a range of cut-off scores using DSM-IV major depression criteria. ROC analyses are useful to determine the optimum cut-off point for a scale, appropriately weighing sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value (Jekel, Elmore, & Katz, 1996). ROC curves were constructed to determine the optimal cutoff point and the overall predictive value of the PDSS and BDI-II as determined by the area under the curve (0.90–1.0 = “excellent,” 0.80– 0.90 = “good,” and 0.70–0.80 = “fair”).

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Construct validity

Inter-subscale correlations of the PDSS’s seven subscales are presented in Table 2. Most subscale scores were correlated at moderate to high levels (r = 0.32–0.83), indicating that content subscale scores represent interrelated constructs of PPD. Individual subscales were more highly correlated with the PDSS total score than with other subscales (r = 0.72–0.97), with the exception of the association between Suicidal Thoughts and Guilt/Shame, which was moderately associated (r = 0.62). This suggests that, in general, these subscales were more directly related to PPD symptoms than to any other individual symptom subscale, and Suicidal Thoughts was not as strongly correlated with other PPD symptoms. Confirmatory factor analysis also was used to evaluate construct validity and to estimate the fit of actual data to hypothesized subscales (Jöreskog, 1969). The fit of the original seven-subscale structure (as outlined by Beck & Gable, 2000) was examined. The latent covariance structure of this model was shown to be not positive definite (i.e., the covariance matrix has at least one variable that is expressed as a linear combination of others, or there is significant multicollinearity), suggesting that the seven-subscale structure did not adequately fit the data. A five-subscale structure was then examined to replicate recent factor structures of the PDSS (Blucker et al., 2014). Table 3 presents the results of the five-subscale CFA of the PDSS. The table includes standardized factor loadings, standard errors, and residual variances for the items assigned to each of the five content scales. Overall, the model demonstrated acceptable fit, RMSEA = .08 (90% CI = [.08, .09], TLI = 0.85, SRMR = .07. Each of the individual factor loadings had a minimum t score of 12.45, indicating that all items fit the model as predicted. All factor loadings were significant (p < .001).

TABLE 2.

PDSS inter-scale correlations

| Diagnostic sample (N = 245) | SLP | ANX/ELB/MNT | LOS | GLT | SUI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleeping/eating disturbance (SLP) | - | ||||

| Anxiety/insecurity (ANX)/emotional lability (ELB)/mental confusion (MNT) | 0.67 | - | |||

| Loss of self (LOS) | 0.60 | 0.83 | - | ||

| Guilt/shame (GLT) | 0.47 | 0.72 | 0.76 | - | |

| Suicidal thoughts (SUI) | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.57 | 0.63 | - |

| PDSS total score | 0.75 | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.62 |

TABLE 3.

Results of confirmatory factor analysis of PDSS in five subscales: maximum-likelihood dimensions and loadings (N = 245)

| Item | I | II | III | IV | V | Residual variance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep/eating disturbance (SLP), α = 0.76 | ||||||

| 1. I had trouble sleeping even when my baby was asleep. | 0.74 (.03) | 0.45 | ||||

| 8. I lost my appetite. | 0.64 (.04) | 0.59 | ||||

| 15. I woke up on my own in the middle of the night and had trouble getting back to sleep. | 0.83 (.03) | 0.32 | ||||

| 22. I tossed and turned for a long time at night trying to fall asleep. | 0.83 (.03) | 0.30 | ||||

| 29. I knew I should eat but I could not. | 0.59 (.05) | 0.65 | ||||

| Anxiety/insecurity (ANX)/emotional lability (ELB)/mental confusion (MNT), α = 0.97 | ||||||

| 2. I got anxious over even the littlest things that concerned my baby. | 0.61 (.04) | 0.63 | ||||

| 3. I felt like my emotions were on a roller coaster | 0.81 (.02) | 0.35 | ||||

| 4. I felt like I was losing my mind. | 0.83 (.02) | 0.32 | ||||

| 9. I felt really overwhelmed. | 0.73 (.03) | 0.46 | ||||

| 10. I was scared that I would never be happy again. | 0.76 (.03) | 0.42 | ||||

| 11. I could not concentrate on anything. | 0.77 (.03) | 0.41 | ||||

| 16. I felt like I was jumping out of my skin. | 0.72 (.03) | 0.48 | ||||

| 17. I cried a lot for no real reason. | 0.72 (.03) | 0.48 | ||||

| 18. I thought I was going crazy. | 0.80 (.03) | 0.36 | ||||

| 23. I felt all alone. | 0.75 (.03) | 0.44 | ||||

| 24. I have been very irritable. | 0.76 (.03) | 0.43 | ||||

| 25. I had a difficult time making even a simple decision. | 0.74 (.03) | 0.46 | ||||

| 30. I felt like I had to keep moving or pacing. | 0.65 (.04) | 0.58 | ||||

| 31. I felt full of anger ready to explode. | 0.71 (.03) | 0.49 | ||||

| 32. I had difficulty focusing on a task. | 0.73 (.03) | 0.47 | ||||

| Loss of self (LOS), α = 0.90 | ||||||

| 5. I was afraid that I would never be my normal self again. | 0.82 (.02) | 0.33 | ||||

| 12. I felt as though I had become a stranger to myself. | 0.84 (.02) | 0.29 | ||||

| 19. I did not know who I was anymore. | 0.83 (.02) | 0.31 | ||||

| 26. I felt like I was not normal. | 0.84 (.02) | 0.30 | ||||

| 33. I did not feel real. | 0.77 (.03) | 0.41 | ||||

| Guilt/shame (GLT), α = 0.81 | ||||||

| 6. I felt like I was not the mother I wanted to be. | 0.81 (.03) | 0.34 | ||||

| 13. I felt like so many mothers were better than me. | 0.82 (.03) | 0.33 | ||||

| 20. I felt guilty because I could not feel as much love for my baby as I should. | 0.61 (.04) | 0.63 | ||||

| 27. I felt like I had to hide what I was thinking or feeling toward the baby. | 0.58 (.05) | 0.69 | ||||

| 34. I felt like a failure as a mother. | 0.87 (.02) | 0.24 | ||||

| Suicidal thoughts (SUI), α = 0.62 | ||||||

| 7. I have thought that death seemed like the only way out of this living nightmare. | 0.95 (.01) | 0.09 | ||||

| 14. I started thinking that I would be better off dead. | 0.93 (.01) | 0.14 | ||||

| 21. I wanted to hurt myself. | 0.77 (.03) | 0.40 | ||||

| 28. I felt that my baby would be better off without me. | 0.65 (.04) | 0.57 | ||||

| 35. I just wanted to leave this world. | 0.93 (.01) | 0.13 |

PDSS, postpartum depression screening scale. Columns are standardized factor loadings with standard errors (in parentheses).

3.2 |. Construct reliability

The PDSS total score demonstrated high internal consistency reliability (α = 0.95), and the subscales demonstrated acceptable to high reliability (see Table 3). However, the Suicidal Thoughts (SUI) subscale reliability estimate fell below the 0.70 recommended cutoff, indicating that the items may not be measuring one latent construct (suicidality). It was noted that items that represent passive suicidal ideation (7, 14, and 35) demonstrated high factor loadings on the latent construct, and the two items measuring active or acute ideation (items 21 and 28) demonstrated lower factor loadings.

3.3 |. Concurrent validity

Using the seven PDSS dimensions, a discriminant function analysis was performed to determine if the PDSS total score accurately predicted membership in either the depressed or the non-depressed group, as defined by SCID-determined DSM-IV MDD diagnosis. The discriminant function calculation was significant, X2 = 100.36, p = .01, Wilkes’ lambda = 0.653, with the discriminant function accounting for 55.3% of the variability between the depressed and non-depressed groups.

Table 4 shows the five dimensions of the PDSS in relation to the discriminant function of each as a predictor between depressed and non-depressed mothers. The correlation values suggested that these scales qualified as interpretable predictors, with the combined factor of Anxiety/Instability, Emotional Lability, and Mental Confusion being an excellent predictor of group membership. The remaining factors were all good predictors of group membership.

TABLE 4.

Correlations between PDSS symptom subscales and canonical discriminant function (N = 245)

| PDSS subscale | Correlation with first discriminant function | Rating |

|---|---|---|

| Sleeping/eating disturbances (SLP) | 0.657 | vg |

| Anxiety/insecurity (ANX)/emotional lability (ELB)/mental confusion (MNT) | 0.907 | e |

| Loss of self (LOS) | 0.706 | vg |

| Guilt/shame (GLT) | 0.708 | vg |

| Suicidal thoughts (SUI) | 0.743 | vg |

PDSS, postpartum depression screening scale; vg, very good; e, excellent.

Table 5 presents the classification of depressed or non-depressed groups based on the SCID for the PDSS and BDI-II. Using the PDSS, 83% of non-depressed mothers were correctly classified in the non-depressed group and 81% of depressed mothers were correctly classified in the depressed group. Using the BDI-II, 89% of non-depressed mothers were correctly classified in the non-depressed group, and 75% of depressed mothers were correctly classified into the depressed group.

TABLE 5.

Discriminant function classification, sensitivity, and specificity of PDSS and BDI-II for MDD detection

| PDSS |

BDI-II |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCID diagnosis |

SCID diagnosis |

||||||

| Depressed | Not depressed | Total | Depressed | Not depressed | Total | ||

| PDSS outcome | BDI-II outcome | ||||||

| Pos. Screen | 29 (True+) | 34 (True−) | 63 | Pos. Screen | 27 (True+) | 23 (True−) | 50 |

| Neg. Screen | 7 (False−) | 168 (True−) | 175 | Neg. Screen | 9 (False−) | 179 (True−) | 188 |

| Total | 36 | 202 | 238 | Total | 36 | 202 | 238 |

| Sensitivity = 29/38 = 76% | Sensitivity = 27/36 = 75% | ||||||

| Specificity = 168/202 = 83% | Specificity = 179/202 = 89% | ||||||

| Positive PV = 29/63 = 46% | Positive PV = 27/50 = 54% | ||||||

| Negative PV = 168/175 = 96% | Negative PV = 179/189 = 95% | ||||||

N = 238. PDSS, postpartum depression screening scale; BDI-II, Beck depression inventory=II; SCID, structured clinical interview for DSM-IV. Positive screen for PDSS defined as Total score ≥ 80. Positive screen for BDI-II defined asTotal score ≥ 14. PV, predictive value.

3.4 |. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive value

The PDSS overall sensitivity for MDD diagnosis was determined to be 0.76 and specificity was 0.83. Table 5 presents a comparative evaluation of sensitivity and specificity of the PDSS and BDI-II for MDD diagnosis. The PDSS and BDI-II produced comparable results, with the PDSS being marginally higher in sensitivity and negative predictive value and the BDI-II being marginally higher in specificity and positive predictive value.

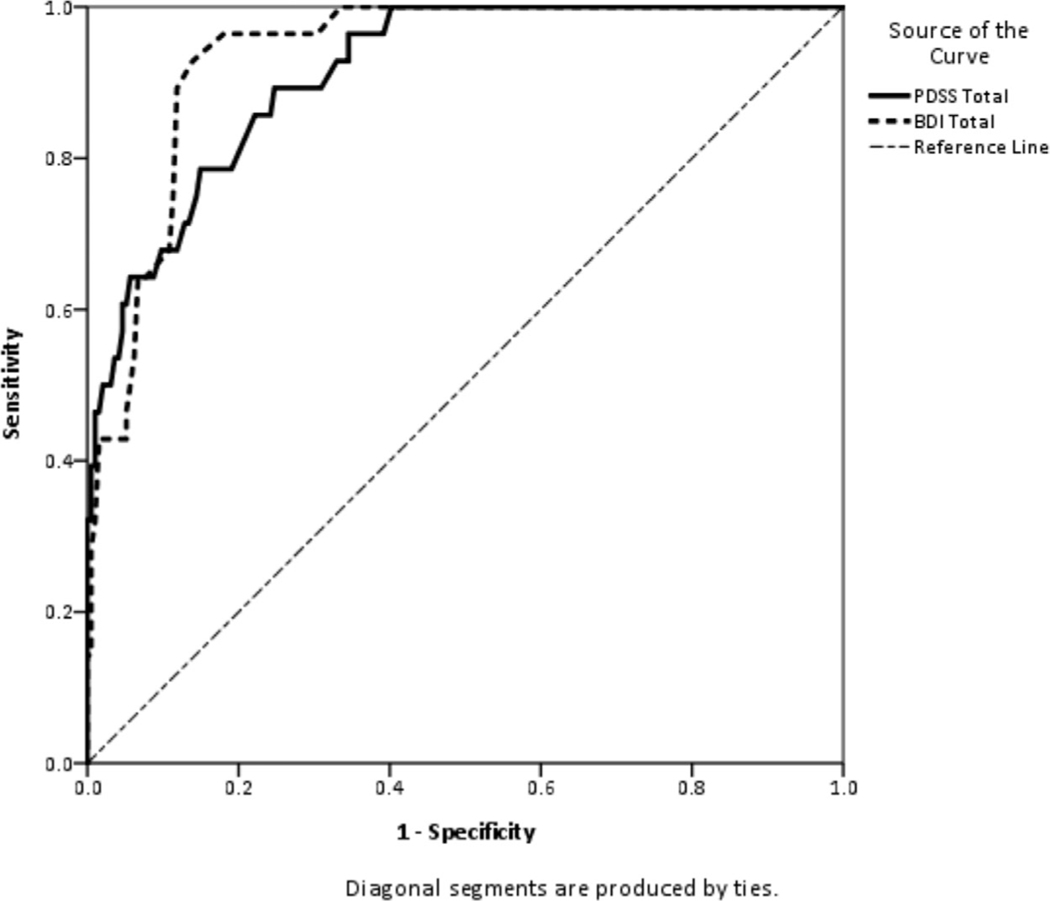

In the ROC analysis (see Figure 1), the PDSS demonstrated excellent balance between sensitivity and specificity. Consistent with reports of Beck and Gable (2002), the optimal cutoff score for the PDSS was determined to be 80 for MDD diagnosis. The BDI-II also demonstrated excellent balance between specificity and sensitivity. The optimal cutoff score for the BDI-II was determined to be 14.5.

FIGURE 1.

ROC curve for PDSS and BDI-II at recommended cutoff scores. PDSS = Postpartum Depression Screening Scale; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II. For PDSS: Major depression. Area under the curve = 0.91 (SD = .02); p < 001. Sensitivity = 0.89. Specificity = 0.71. For BDI-II: Major depression. Area under the curve = 0.93 (SD = .02); p = 0.001. Sensitivity = 0.94. Specificity = 0.73

4 |. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to replicate the psychometric properties of the PDSS in a diverse sample of mothers with older infants and compare it to another frequently used screener, the BDI-II. These findings partially replicate those originally reported by Beck and Gable (2000) for the PDSS. One stark difference between this study’s findings and those of Beck and Gable (2000) was that the seven-factor structure of the PDSS was not supported; a five-factor structure was a better fit to the data. Construct validity of the five-factor structure of the PDSS for our sample was good, as indicated by inter-scale correlations and confirmatory factor analysis. These findings match a recent psychometric study of the PDSS in mothers of NICU infants (Blucker et al., 2014).

Adequate reliability was demonstrated through reliability estimates. Concurrent validity, established through discriminant function classification and canonical discriminant function analysis, was good. In comparison to the BDI-II, results indicate the PDSS had comparable levels of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value. Both the PDSS and the BDI-II predicted significant and largely overlapping proportions of the variance in SCID-derived MDD diagnoses. Despite overall acceptable model fit, the TLI was lower than the recommended cutoff score of 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The remaining fit indices provided moderate support for acceptable model fit between observed and modeled data. The primary problem with the model fit was related to the SUI scale. One possible explanation is that although depressive symptoms can be common in the postpartum period, mothers may not be reporting suicidal thoughts. This lack of reporting is evident from the low correlation between the SUI scale and the total score, as well as among the subscale correlations with the SUI score. Additionally, the SUI scale demonstrated less than acceptable internal consistency, related to low correlations between passive suicidal ideation and active or acute suicidal ideation. Further research into potential barriers to reporting suicidal thoughts (e.g., shame, fear) would be beneficial to better understand this discrepancy in model fit.

Similarities between these results and Beck and Gable’s (2000) findings were obtained despite differences in the two samples: mothers in the original normative sample were better educated, more likely to be married, and less ethnically diverse. Further, the infants in the current sample were on average older than those in the original sample.

By most definitions, some of the depressed mothers in the present sample might not technically have been diagnosed with PPD, given the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of onset of depressive symptoms within 4 weeks after birth. Mothers may have difficulty distinguishing major depressive symptoms from typical and expected shifts in emotional and physiological functioning during this arguably narrow timeframe. PDSS administration occurring later in the first year could account for the lack of clear superiority of the PDSS relative to the BDI-II in specificity, selectivity, and predictive ability due to the generalization of depressive symptoms beyond that of new motherhood. As mothers begin to integrate roles prior to childbirth, symptoms may be viewed as general depression (e.g., loss of interest in activities previously enjoyed) rather than related to the new role of motherhood. Also, given that the average duration of postpartum depression is roughly 6–7 months (O’Hara et al., 2000), some depressed mothers in the present sample may have had longer than average episodes or later than average onsets. However, prevalence estimates suggest that the base rates of PPD are relatively stable over the first year postpartum (Goodman, 2004). Further work directly comparing the sensitivity and specificity of PDSS early and late in the postpartum period might help improve the accuracy of MDD diagnosis in the postpartum period.

Another area of differences between the present study and Beck’s pioneering work was in sensitivity and specificity. Although our results put overall sensitivity and specificity in the excellent range, based on cutoff scores the PDSS missed almost 30% of true depression cases. Pertinent to this discrepancy is that mothers in our study diagnosed with depression in remission were grouped with non-depressed mothers and were contrasted with mothers diagnosed with current major depression. Beck and Gable (2000) used the diagnostic category of minor depression. Had we used this diagnostic category, the sensitivity and specificity of the self-report measures might have been better.

The need for an effective screener for PPD that takes the mother’s experience into account prompted the development of the PDSS. With this qualitatively sound and PPD-specific screener, clinicians have an opportunity to assess the unique attributes related to the postpartum period. The BDI-II does not take into the account the adoption of new roles, values, and goals that come with new motherhood and could therefore miss opportunities to capture the struggles a new mother may be experiencing in the first year after birth. The results of the current analyses support conclusions from the original normative studies that the PDSS is a valuable tool for clinicians and others to identify women who are dealing with mood disorders, and add further value for using the PDSS beyond the initial postpartum period and into the latter part of the first year of motherhood.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Tara Curly and Kristen Ruhl for their assistance in data analysis, and Kaile Ross, Tattiana Romo, Lacey Clement, and Ryan Asherin for their comments and support. This research was supported in part by NICHD grant HD049732, and by funds provided by the College of Liberal Arts & Sciences at the University of Colorado Denver.

Funding information

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Grant number: HD049732; University of Colorado Denver College of Liberal Arts & Sciences

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT (2002). Postpartum depression: A metasynthesis. Qualitative Health Research, 12, 453–472. 10.1097/00006199200109000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT, & Gable RK (2000). Postpartum depression screening scale: Development and psychometric testing. Nursing Research, 49, 272–282. 10.1097/00006199-200009000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT, & Gable RK (2001a). Further validation of the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale. Nursing Research, 50, 155–164. 10.1097/00006199-200105000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT, & Gable RK (2001b). Comparative analysis of the performance of the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale with two other depression instruments. Nursing Research, 50, 242–250. 10.1097/00006199-200107000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT, & Gable RK (2002). Postpartum depression screening scale manual. Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer R, & Brown G. (1996). BDI-II manual. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett HA, Einarson A, Taddio A, Koren G, & Einarson TR (2004). Prevalence of depression during pregnancy: Systematic review. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 103, 698–709. 10.1097/01.aog.0000116689.75396.5f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blucker RT, Gillaspy JA, Jackson D, Hetherington C, Kyler K, Cherry A, ... Gillaspy SR (2014). Postpartum depression in the NICU: An examination of the factor structure of the Postpartum Depression Screening Scale. Advances in Neonatal Care, 14, 424–432. 10.1097/ANC.0000000000000135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach LJ, & Gleser GC (1957). Psychological tests and personnel decisions. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JW (1996). Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders, clinical version (SCID-CV). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd RL, Sobell M, Velasquez MM, Ingersoll K, Nettleman M, Sobell L, ... Nagaraja, J. (2007). Preventing alcohol exposed pregnancies: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32, 1–10. 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman LL, Larsen KE, & Coy KC (2007). Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 85–602. 10.1017/s0954579407070289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiopoulos AM, Bryan TL, Wollan P, & Yawn BP (2001). Routine screening for postpartum depression. Journal of Family Practice, 50, 117–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjerdingen DK, & Yawn BP (2007). Postpartum depression screening: Importance, methods, barriers, and recommendations for practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 20, 280–288. 10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JH (2004). Postpartum depression beyond the early postpartum period. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 33, 410–420. 10.1177/0884217504266915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanna B, Jarman H, & Savage S. (2004). The clinical application of three screening tools for recognizing post-partum depression. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 10, 72–79. 10.1111/j.1440172x.2003.00462.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanusa BH, Scholle SH, Haskett RF, Spadaro K, & Wisner KL (2008). Screening for depression in the postpartum period: A comparison of three instruments. Journal of Women’s Health, 17, 585–596. 10.1089/jwh.2006.0248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jekel JF, Elmore JG, & Katz DL (1996). Epidemiology, biostatistics and preventive medicine. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog KG (1969). A general approach to confirmatory maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 34, 183–202. 10.1007/bf02289343 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Danko CM, Cejka A, & Everhart KD (2015). Maternal depression and the learning-promoting effects of infant-directed speech: Roles of maternal sensitivity, depression diagnosis, and speech acoustics. Infant Behavior and Development, 41, 52–63. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.06.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan PS, Danko CM, Diaz A, & Kalinka CJ (2011). An associative learning deficit in 1-year-old infants of depressed mothers: Role of depression duration. Infant Behavior & Development, 34, 35–44. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, & Muthén L. (2013). Mplus version 7.1 [Computer software]. Nunnally JC, & Bernstein IH (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Stuart S, Gorman L, & Wenzel A. (2000). Efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for postpartum depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 1039–1045. 10.1001/archpsyc.57.11.1039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, & McCabe JE (2013). Postpartum depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 379–407. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohr-Preston SL, & Scaramella LV (2006). Implications of timing of maternal depressive symptoms for early cognitive and language development. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9, 65–83. 10.1007/s10567-006-0004-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. (2016). Statistical package for the social sciences v. 24 [Computer software].

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2011, May 19). Demographic profiles of General Population and Housing Characteristics—City and County of Denver. Retrieved from https://demography.dola.colorado.gov/census-acs/2010-census-data/

- Wang Y, & Gorenstein C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 35, 416–431. 10.1590/1516-4446-2012-1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]