Abstract

The roles of APOEε4 and APOEε2—the strongest genetic risk and protective factors for Alzheimer’s disease—in glial responses remain elusive. We tested the hypothesis that APOE alleles differentially impact glial responses by investigating their effects on the glial transcriptome from elderly control brains with no neuritic amyloid plaques. We identified a cluster of microglial genes that are upregulated in APOEε4 and downregulated in APOEε2 carriers relative to APOEε3 homozygotes. This microglia-APOE cluster is enriched in phagocytosis—including TREM2 and TYROBP—and proinflammatory genes, and is also detectable in brains with frequent neuritic plaques. Next, we tested these findings in APOE knock-in mice exposed to acute (lipopolysaccharide challenge) and chronic (cerebral β-amyloidosis) insults and found that these mice partially recapitulate human APOE-linked expression patterns. Thus, the APOEε4 allele might prime microglia towards a phagocytic and proinflammatory state through an APOE–TREM2–TYROBP axis in normal aging as well as in Alzheimer’s disease.

Although genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have rendered dozens of new risk loci in the past decade, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 allele remains the strongest genetic risk factor for sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and the ε2 allele the strongest protective genetic factor1. APOEε4 carriers have approximately three (for heterozygotes) to 12 (for homozygotes) times higher risk of developing AD and an earlier age at symptom onset than APOEε3 homozygotes2. Conversely, one APOEε2 allele reduces the risk of developing AD by about 60%, and two copies of APOEε2 decrease AD risk by 85% compared to APOEε3 homozygotes3. Pathologically, the APOEε4 allele is primarily associated with a higher burden of amyloid-β (Aβ) plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), whereas the APOEε2 allele is associated with a lower burden of both lesions3–7. In fact, APOE is known to deposit with Aβ in dense-core, typically neuritic, amyloid plaques and within CAA-laden vessels8.

In the past 5 years our understanding of the role of the APOE genotype in AD has expanded from Aβ-centric to glial mechanisms. APOE is expressed and secreted by both microglia and astrocytes, which are known to react to neuritic plaques (NPs)9–11 and to take up and degrade Aβ12. Previous stereology-based quantitative neuropathological studies did not detect any differences in the absolute number of reactive (GFAP+) astrocytes and activated (IBA1+ or CD68+) microglia between APOEε4 carriers and noncarrier AD subjects9–11. Recent transcriptomic studies, however, have shown that the molecular signatures of these glial cells differ by APOE genotype in mice expressing human APOE alleles (ε2, ε3 or ε4) within the murine Apoe locus13–17 (henceforth referred to as APOE knock-in mice), and in human inducible pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC)-derived glial cells obtained from patients with AD12,18,19. Nonetheless, the effects of the various APOE alleles on microglial and astrocytic transcriptomic responses in the human aging and AD brain remain to be fully elucidated20,21.

We hypothesized that the APOEε4 and APOEε2 alleles are associated with opposing microglial and astrocytic phenotypes, deleterious and protective, respectively. To test this hypothesis, we investigated whether APOE genotype influences microglial and astrocytic transcriptomic responses in the normal aging human brain, and in the context of AD (that is, at increasing levels of NPs and neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs)), in publicly available brain bulk RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) datasets. We observed that the APOE genotype influences the microglial gene expression profile, with APOEε4 carriers exhibiting a proinflammatory and phagocytic phenotype compared to APOEε3 homozygotes, and APOEε2 carriers demonstrating the opposite effect. Importantly, these differences were present in subjects with no NPs, suggesting an APOEε4-mediated priming of microglia. Follow-on experiments in APOE knock-in mice subjected to an acute inflammatory stimulus such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or in the presence of chronic β-amyloidosis (that is, crossed with APP/PS1 transgenic mice), further support this association of microglial phenotype with the APOEε4 allele. In contrast to microglia, the influence of APOE alleles on the astrocyte transcriptome appears to be modest and suggests a dysregulation of lipid metabolism and the extracellular matrix.

Results

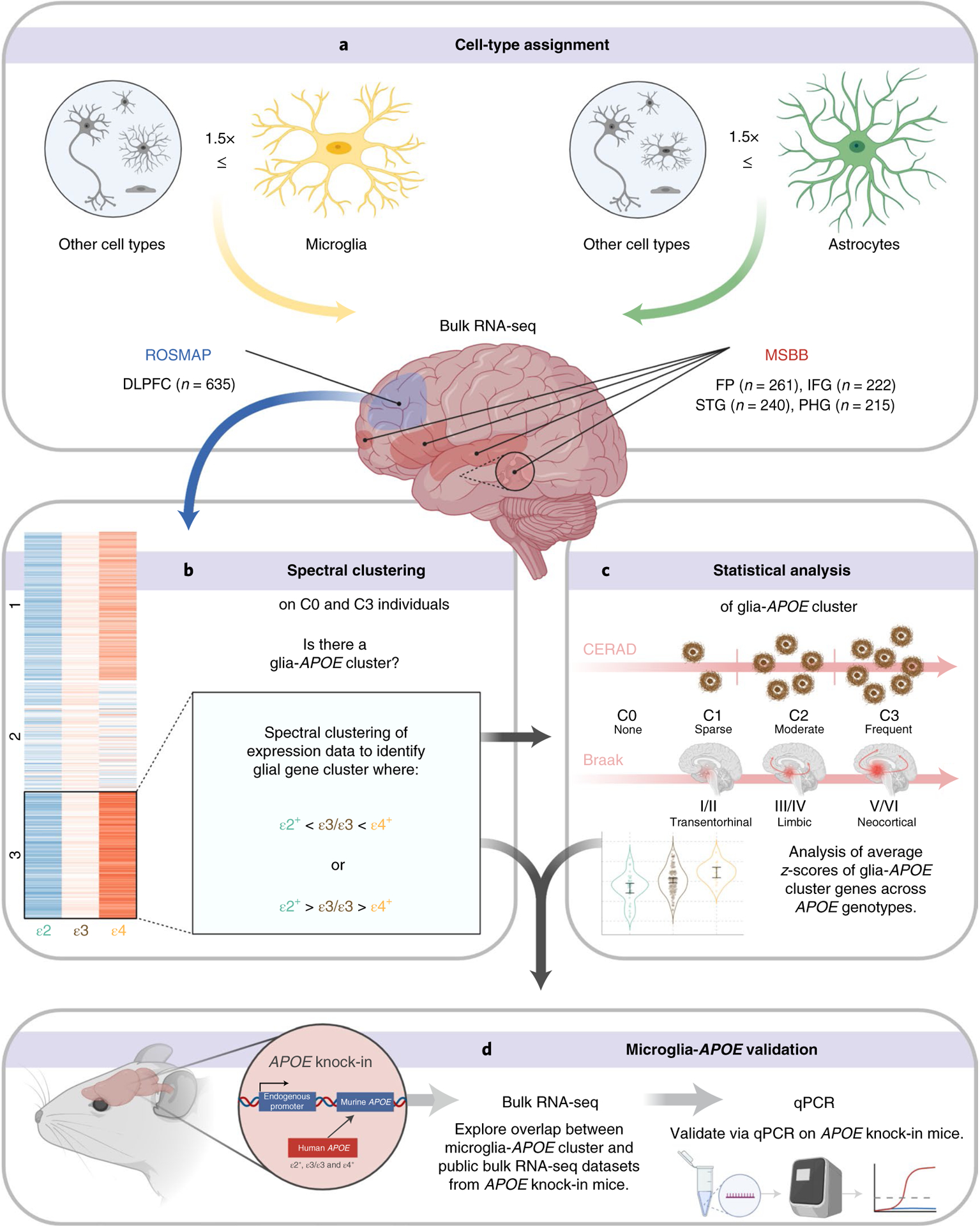

A graphical summary of the workflow is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 |. Workflow of integrative analyses of APOE associations with microglia and astrocyte transcriptomic phenotypes.

a, Microglia- and astrocyte-predominant genes were defined as those whose expression is ≥1.5-fold in microglia or astrocytes, with respect to expression in all other cell types (neurons, oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells; and astrocytes or microglia, respectively), based on a public cell-type-specific RNA-seq database. Public bulk RNA-seq databases from ROSMAP DLPFC and MSBB STG, IFG, PHG and FP were interrogated for expression levels of these microglia- and astrocyte-predominant genes across APOE alleles ((ε2+: ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3); (ε3: ε3/ε3); (ε4+: ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4, ε4/ε4)) and CERAD NP scores (C0, none; C1, sparse; C2, moderate; C3, frequent). b, Spectral clustering of group averaged z-scores of gene expression levels enabled the identification of gene clusters that follow an ε2 > ε3 > ε4 or an ε2 < ε3 < ε4 pattern in subjects without NPs (C0) and with frequent NPs (C3), supporting an association with the APOE genotype that is independent of APOE effects on AD neuropathological changes. c, Statistical analyses were performed to test whether cluster genes are differentially expressed between APOEε2 carriers, APOEε4 carriers and APOEε3 homozygotes. d, APOE-associated genes obtained from human transcriptomic datasets were cross-validated in mouse APOE knock-in mice expressing different human APOE alleles in the mouse Apoe locus, by both RT–qPCR and analysis of publicly available transcriptomic datasets from these mice.

APOE-linked microglial transcriptomic changes in normal aging.

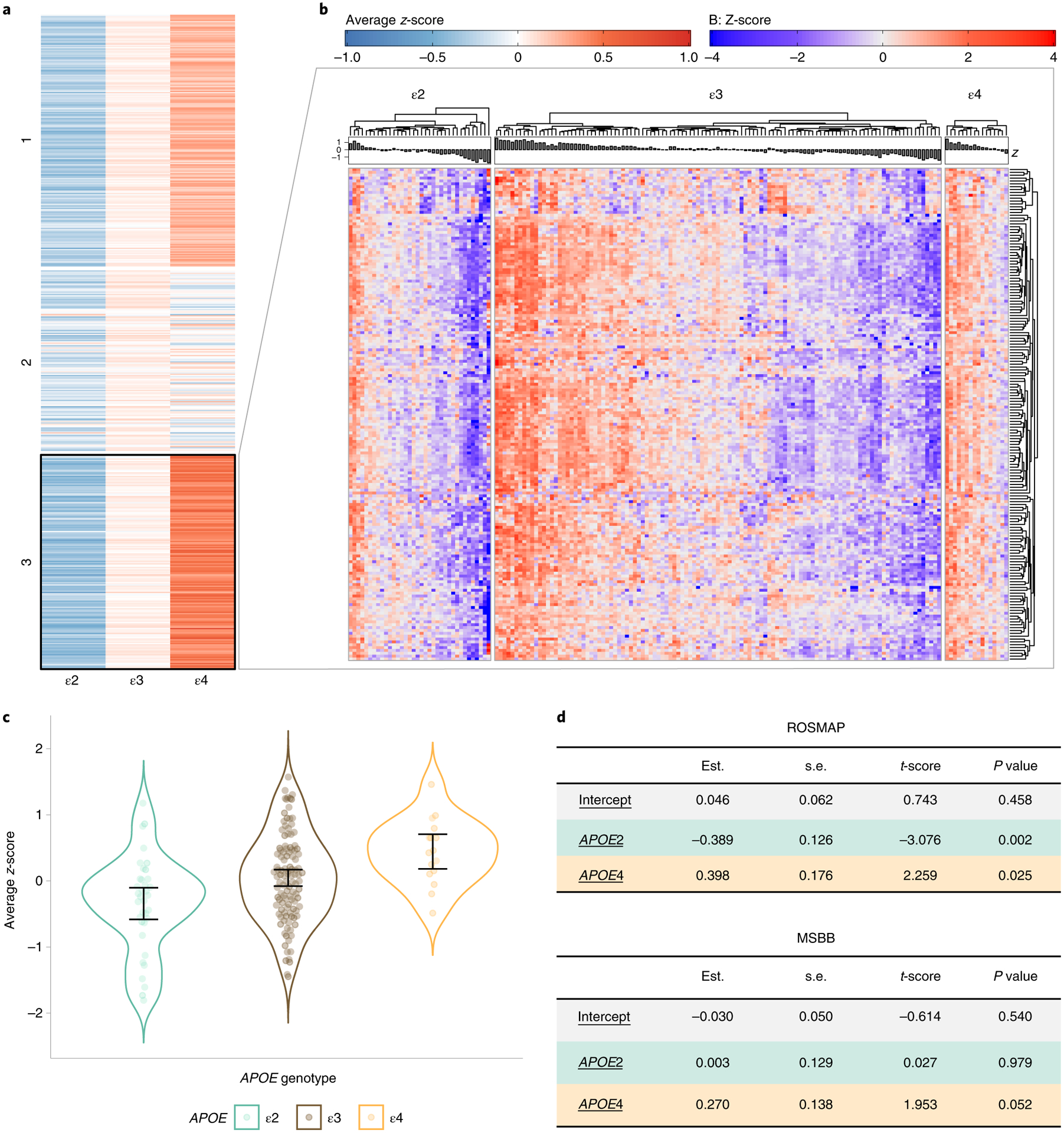

Spectral clustering is useful in finding genes with similar expression profiles in large datasets by extraction of connected genes in a coexpression graph. To identify clusters of coexpressed microglial genes associated with APOE alleles, we performed spectral clustering on the expression levels of 519 microglia-predominant genes in the subset of control subjects with no NPs (CERAD NP score 0 or C0) from the Religious Orders Study and Memory and Aging Project (ROSMAP) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) bulk RNA-seq dataset. We reasoned that genes following an ε2 < ε3 < ε4 or an ε2 > ε3 > ε4 pattern of expression level would be more likely to be regulated or influenced by the APOE genotype, whereas those following a ε2 ~ ε3 ~ ε4 pattern would not be related to APOE. Spectral clustering with k = 3 using the average z-score across individuals in each APOE group (Fig. 2a) identified a cluster with 172 coexpressed genes that are both down in APOEε2 carriers (including ε2/ε3 and ε2/ε2) and up in APOEε4 carriers (including ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4 and ε4/ε4) compared to APOEε3 homozygotes (heatmap in Fig. 2b, violin plot in Fig. 2c). The 172 genes in this cluster, henceforth referred to as the ‘microglia-APOE cluster’, with their average z-scores for each APOE group of the ROSMAP C0 cohort, are available in Supplementary Table 1.

Fig. 2 |. Identification of a microglial gene signature associated with APOE genotype in normal aging.

a, Spectral clustering of group averaged expression-level z-score for each of 519 microglia-predominant genes in ROSMAP subjects with no NPs (CERAD 0), split by APOE group. b, Heatmap showing detail of the expression level of cluster 2 genes from a for all ROSMAP DLPFC C0 subjects, by APOE group (n = 36 APOEε2 carriers, n = 113 APOEε3 homozygotes, n = 16 APOEε4 carriers). Note that the 172 genes of this microglia-APOE cluster overall have higher expression levels in APOEε4 and lower in APOEε2 carriers relative to APOEε3 homozygotes, who have substantial interindividual variability. c, Violin plots showing average expression-level z-score of the 172 genes of the microglia-APOE cluster in each subject, by APOE group. Error bars represent the lower and upper 95% normal confidence limits of the sample mean based on the t-distribution. d, Statistical analysis of the microglia-APOE cluster by APOE group in ROSMAP and MSBB subjects from all brain regions. The average z-scores of cluster genes were tested using a linear model. Estimated coefficient (est.), standard error (s.e.m.), t-score and corresponding two-sided P value are represented.

A closer inspection of this microglia-APOE cluster revealed a strong representation of multiple aspects of phagocytosis, including chemotaxis genes (CCL2, CCL20, CCR1, CCR5); cytoskeleton and cell motility (ABI3, AIF, ARPC1B, DOCK2, DOCK11, LCP1, MYO1F, MYOF, PARVG, SCIN); extracellular matrix and cell adhesion (CLEC5A, CHSY1, EMB, HPSE, ITGAM, ITGB2, ITGB3, LPXN, NEDD9, PLAU, PLEK, SELL, SPP1, SRGN, TGFBI, TGFBR1); antigen presentation (CD14, CD74, CD86, CIITA); opsonization (immunoglobulin receptor FCER1G, complement factors C3, C1QA, C1QB and C1QC and complement receptors C3AR1, C5AR1 and VSIG4); scavenger receptors (CD163, MSR1); phagocytosis receptors and adapters (TREM1, TREM2, TREML1, TYROBP); autophagosome respiration burst (CYBB, NCF2, NCF4); and lysosomal function (CD68, CPVL, CTSC, CTSS, LAPTM5, NAGA). Additionally, this gene cluster contains numerous proinflammatory genes including interleukins and interleukin receptors (IL10RA, IL13RA1, IL16, IL18BP, IL1R2); Toll-like receptors (CD180, TLR1, TLR2, TLR3, TLR7); interferon response (IFNGR1, IFNGR2, IRF8); tumor necrosis factor pathway (TNFRSF1B, TNFAIP8L2); arachidonic acid metabolism (ALOX5, ALOX5AP, PLA2G4A, PTGER4, PTGS1, PTGS2, TBXAS1); and the inflammasome-associated caspase 1 (CASP1). Other interesting genes include the AD-linked GWAS loci INPP5D, MS4A7 (within the MS4A cluster), ABI3 and PLCG2 (refs.1,22–24); calcium homeostasis (S100A9 and S100A11); purinergic signaling (P2RY12 and P2RY13); energy metabolism (FBP1, PYGL and UCP2); and lipid metabolism (CH25H).

Statistical analyses revealed a significant difference in this microglia-APOE cluster composite gene expression—defined as the average z-score of the 172 genes—in C0 APOEε2 and APOEε4 carriers versus C0 APOEε3 homozygotes (APOEε2 versus APOEε3 estimate (s.d.), P = −0.39 (0.13), P = 0.002; APOEε4 versus APOEε3, 0.40 (0.18), P = 0.025; APOEε4 versus APOEε2, 0.79 (0.20), P = 0.0001). Application of spectral clustering on the Braak NFT 0/I/II (B1) rather than C0 subjects yielded similar results, with one cluster of similar size (n = 200 genes) following the ε2 > ε3 > ε4 pattern and significantly overlapping with the microglia-APOE cluster derived from C0 subjects (n = 100 genes overlapping; P = 2.24 × 10−23, hypergeometric test). Comparison of the composite z-score of this B1-derived microglia gene cluster across APOE genotypes revealed statistically significant differences or a trend towards statistical significance relative to APOEε3 homozygotes (APOEε2 versus APOEε3, −0.45 (0.16), P = 0.006; APOEε4 versus APOEε3, 0.23 (0.15), P = 0.123; APOEε4 versus APOEε2, 0.69 (0.20), P = 0.0007).

These analyses were run in a second, independent, public gene expression dataset obtained from the Mount Sinai Brain Bank (MSBB), which includes four different brain regions. When the MSBB bulk RNA-seq study brain regions were analyzed individually, the superior temporal gyrus (STG) contained 71 genes with the ε2 < ε3 < ε4 pattern in common with the ROSMAP microglia-APOE cluster (P = 5.83 × 10−4, hypergeometric test) whereas the other brain regions (parahippocampal gyrus (PHG), inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and frontal pole (FP)) did not show significant overlap with the ROSMAP microglia-APOE cluster. When RNA-seq data from these four brain regions were combined to maximize statistical power, the microglia-APOE cluster displayed a similar trend of change in C0 individuals across APOE groups (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, APOEε2 and APOEε3 did not significantly differ (APOEε2 versus APOEε3, −0 (0.13), P = 0.98), but the difference between APOEε4 and APOEε3 subjects was marginally significant (APOEε4 versus APOEε3, 0.27 (0.14), P = 0.052).

Taken together, these data show a strong association between APOE alleles and the transcriptional profile of microglia in the normal aging brain without neuritic plaques, with APOEε4 driving an apparent switch towards a phagocytic and proinflammatory phenotype25,26.

APOEε4-linked phagocytic/proinflammatory microglia in AD.

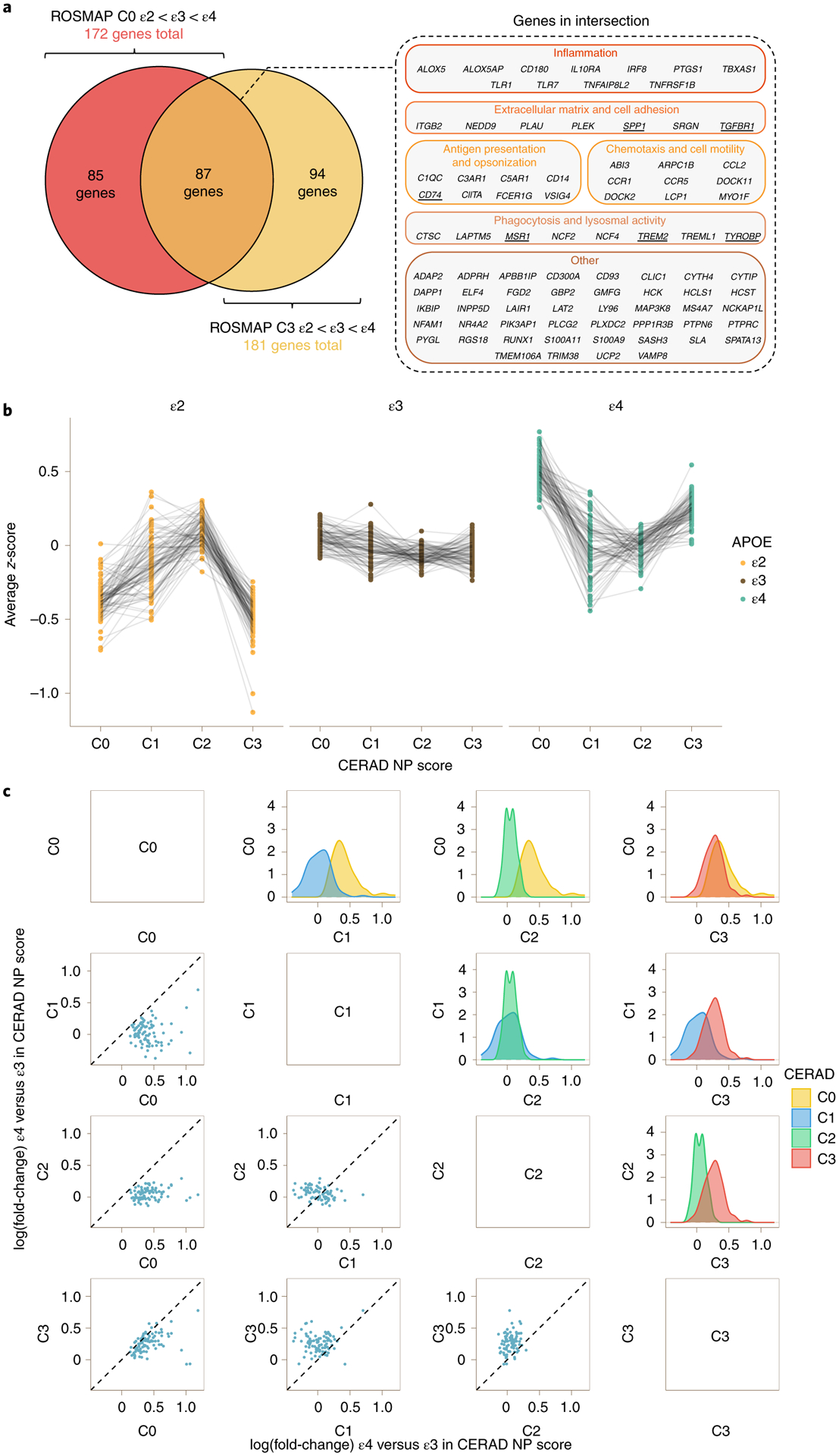

Next, we investigated whether microglia-APOE cluster genes are also present in AD brains and whether changes across APOE genotypes are accentuated or attenuated with increasing NP densitiy (that is, increasing CERAD NP scores). Spectral clustering applied on the ROSMAP DLPFC bulk RNA-seq expression data from individuals with frequent NP (C3) also revealed a cluster of 181 microglia-predominant genes (cluster 3) following an ε2 < ε3 < ε4 pattern. Importantly, 87 of these 181 genes (Fig. 3a) were also part of the microglia-APOE cluster found in the absence of NP (C0 subjects), an overlap that was statistically significant (P = 5.5 × 10−17, hypergeometric test). These included chemotaxis (CCL2, CCR1, CCR5); cytoskeleton and cell motility (ABI3, ARPC1B, DOCK2, DOCK11, LCP1, MYO1F); extracellular matrix and cell adhesion (ITGB2, NEDD9, PLAU, PLEK, SPP1, SRGN, TGFBR1); antigen presentation (CD14, CD74, CIITA); opsonization (FCER1G, C1QC, C3AR1, C5AR1, VSIG4); the scavenger receptor MSR1; phagocytosis receptors and adapters (TREM2, TREML1, TYROBP); autophagosome respiration burst and lysosomal function (NCF2, NCF4, CTSC, LAPTM5); the interleukin receptor IL10RA; Toll-like receptors (CD180, TLR1, TLR7); the interferon-related transcription factor IRF8; the tumor necrosis factor pathway (TNFRSF1B, TNFAIP8L2); and arachidonic acid metabolism (ALOX5, ALOX5AP, PTGS1, TBXAS1). These 87 genes also included the AD-linked GWAS genes INPP5D, MS4A7, ABI3 and PLCG2 (refs.1,22–24), the calcium homeostasis genes S100A9 and S100A11 and the energy metabolism genes PYGL and UCP2.

Fig. 3 |. The microglia-APOE signature is independent of known APOE effects on AD neuropathological changes.

a, Venn diagram (left) showing intersection between the 172 genes from the microglia-APOE cluster obtained by spectral clustering in ROSMAP C0 subjects and the 181 genes from C3 subjects. Note that the 87 DEGs in the intersection included relevant phagocytic and proinflammatory genes (right). The underlined genes were subsequently tested by RT–qPCR in APOE knock-in mice. b, Dot plots with connecting lines depicting group averaged expression-level z-scores of the 87 genes from a split by CERAD NP score and APOE genotype. Note that the most prominent changes across APOE genotypes correspond to C0 (no NPs) and C3 (frequent NPs) subjects. c, Correlation matrix comparing the APOEε4 versus APOEε3 change in expression levels (log(fold-change)) of the 87 DEGs from the microglia-APOE cluster of C0 and C3 subjects in the ROSMAP cohort. The scatter dot plots on the left and density plots on the right demonstrate that the largest differences between APOEε4 carriers and APOEε3 homozygotes are observed in C1 (sparse NPs) and C2 (moderate NPs) versus both C0 (no NPs) and C3 (frequent NPs) subjects. By contrast, APOEε4 versus APOEε3 differences in expression levels were attenuated between C1 (sparse NPs) and C2 (moderate NPs) subjects, and between C0 (no NPs) and C3 (frequent NPs) subjects, suggesting either higher heterogeneity in microglial activation state in intermediate stages (C1 and C2) masking APOE genotype effects, or two waves of activation of this microglial transcriptional program (in C0 and C3).

Statistical testing confirmed a significant difference in the average expression of this gene cluster in APOEε2 and APOEε4 carriers versus APOEε3 homozygotes within these C3 subjects (APOEε2 versus APOEε3, −0.45 (0.21), P = 0.034; APOEε4 versus APOEε3, 0.30 (0.10), P = 0.003; APOEε4 versus APOEε2, 0.75 (0.21), P = 0.0005). In parallel analyses, spectral clustering in Braak NFT V/VI stages (B3 subjects) revealed a cluster (cluster 2) of 141 genes, 99 of which overlapped significantly with the C3 cluster above (P = 1.6 × 10−35, hypergeometric test). When the composite expression-level z-score of these 141 genes was statistically compared across APOE groups, APOEε2 carriers exhibited a trend towards significantly lower levels than APOEε3 homozygotes (−0.53 (0.29), P = 0.066) whereas APOEε4 differed significantly from APOEε2 carriers (0.63 (0.29), P = 0.032) but not from APOEε3 homozygotes (0.09 (0.11), P = 0.378). To determine whether these results are robust across multiple datasets and brain regions, we also performed spectral clustering on C3 subjects from the MSBB cohort. Statistical testing of the 181 ROSMAP C3 ε2 < ε3 < ε4 cluster genes in the combined MSBB data revealed significant differences between APOEε4 and APOEε3 carriers (APOEε2 versus APOEε3, −0.11 (0.16), P = 0.504; APOEε4 versus APOEε3, 0.19 (0.08), P = 0.022; APOEε4 versus APOEε2, 0.30 (0.17), P = 0.084). In addition, MSBB STG and IFG included many genes with the ε2 < ε3 < ε4 pattern, which overlapped significantly with the 181 ROSMAP C3 cluster genes (STG: 82 genes, P = 2.79 × 10−11; IFG: 87 genes, P = 3.38 × 10−16). In contrast, MSBB PHG and FP had very few genes exhibiting these patterns. The modest concordance between ROSMAP and MSBB brain regions (analyzed individually) could be explained, at least in part, by the small number of APOEε4 carriers among C0 subjects and of APOEε2 carriers among C3 subjects, which is inherent in the effect of these APOE alleles on AD risk.

To further confirm the associations of APOE genotype with microglial gene expression independent of plaques, we also performed differential expression analysis of the ROSMAP DLPFC bulk RNA-seq dataset adjusting for CERAD NP score, using APOE genotype as a factor and with an APOEε4 allele dosage model. These models identified 117 and 185 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), respectively, with significantly increased expression in APOEε4 carriers compared to APOEε3 homozygotes (Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). In the dosage model, 79 genes reached study-wide significance (that is, adjusted P < 0.05) in the ROSMAP data and, of these, 63 were also significant (adjusted P < 0.05) in the combined MSBB data. Notably, TYROBP is significant (adjusted P < 0.05) in both datasets while TREM2 is significant (adjusted P < 0.05) in MSBB but only nominally significant (unadjusted P < 0.05) in the ROSMAP data.

We next investigated whether the strength of the association between APOE genotype and the microglial transcriptome varies across CERAD NP scores. We hypothesized that differences in the microglial transcriptome would become more prominent in individuals with moderate (C2) or frequent (C3) cortical NPs (that is, greater fold-changes as AD neuropathology accumulates), given the well-established response of microglia near NPs10,11. We focused these analyses on the 87 genes that are common between the microglia-APOE C0 and C3 clusters—that is, those genes which demonstrated an ε2 < ε3 < ε4 pattern in ROSMAP individuals with no or frequent NPs. Figure 3b illustrates the average expression levels of these 87 microglia-predominant genes across CERAD NP scores, split by APOE group. Figure 3c shows the matrix of correlation and density plots of fold-change for APOEε4 versus APOEε3 comparison across CERAD NP scores. Surprisingly, APOE-associated microglial gene expression changes were most prominent in the absence of NPs (C0) and in the presence of frequent NPs (C3), whereas these differences were attenuated between sparse (C1) and moderate (C2) NPs. Taken together, these results suggest that microglia are primed toward a proinflammatory and phagocytic phenotype in APOEε4 carriers in the normal aging brain, and that these microglial responses are again exacerbated in advanced AD stages.

APOE-associated astrocyte transcriptomic changes.

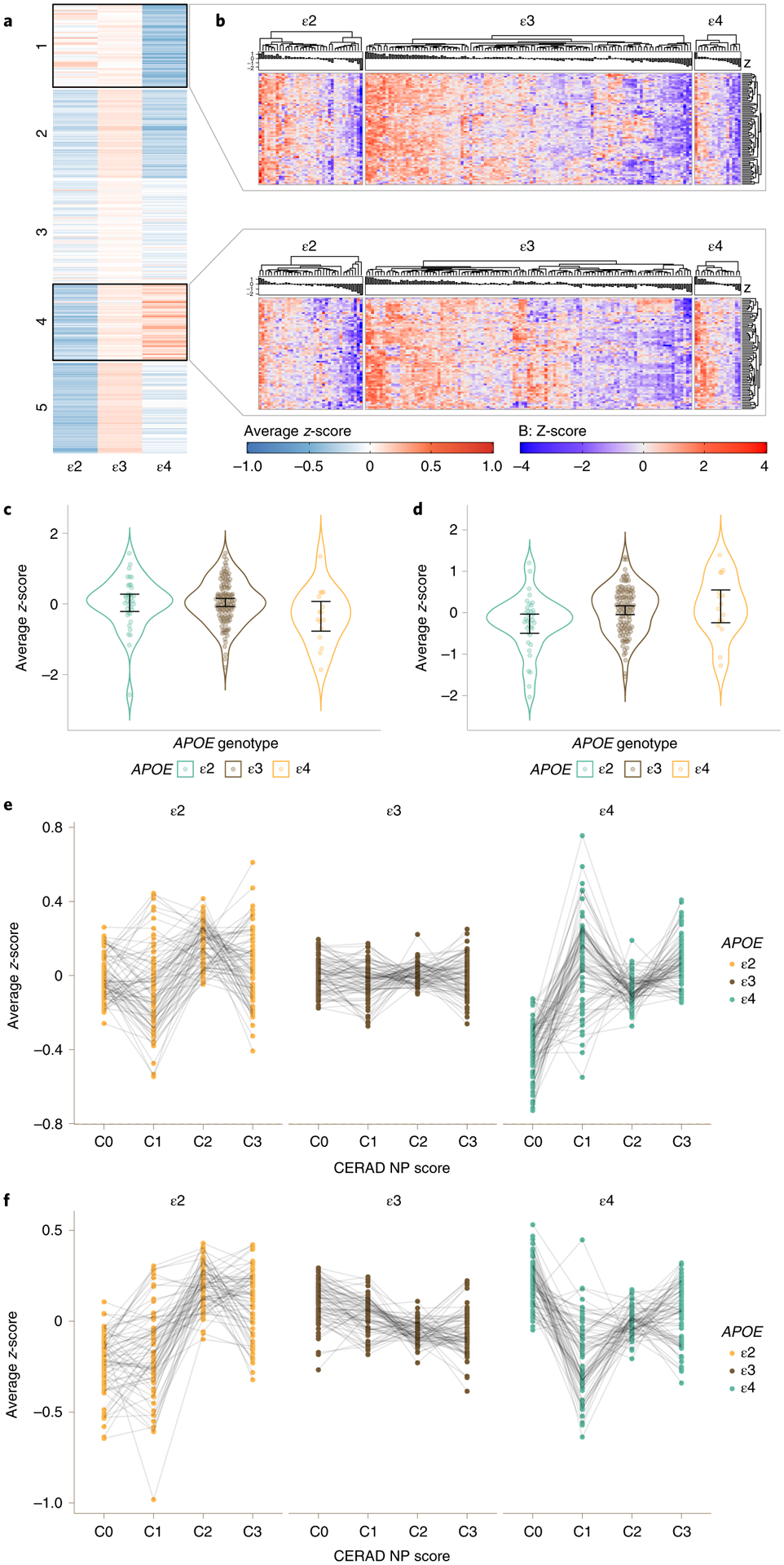

Since APOE expression is highest in astrocytes in the normal brain27, we also investigated APOE allele-associated effects on the astrocyte transcriptome in ROSMAP brains with no NPs (C0 subjects). By applying spectral clustering on the average z-scores of each APOE group for 397 astrocyte-predominant genes, we identified five clusters with distinct patterns of gene coexpression across APOE alleles (Fig. 4a). Clusters 1 and 4 stood out as following an ε2 > ε3 > ε4 and an ε2 < ε3 < ε4 pattern of expression, respectively (Fig. 4b–d). A closer look at cluster 1 (ε2 > ε3 > ε4, n = 75 genes) revealed genes involved in lipid metabolism (ACACB, ACBD7, ACOT11, APOE, LRAT, MTTP, PLA2G5, PLIN1, PLIN5, TTPA) and the extracellular matrix (COL5A3, HEPACAM, PAPLN, SDC4, SNTA1), the trophic factor receptors FGFR3 and CNTFR and many transcription factors including NFATC4. Interestingly, cluster 4 (ε2 < ε3 < ε4, n = 69 genes) is represented also by lipid metabolism (ABCD2, BBOX1, EHHADH) and extracellular matrix (DTNA, FREM2, PLOD2, PTN, SPARCL1) genes, but also includes cytoskeleton (CNN3, GFAP, TUBB2B, VAV3), calcium homeostasis (CAMK2G, SRI, TRPM3), antioxidant defense (MGST1, PON2, PON3), immune response (CXCL1, IL33, TNFRSF11B) and other relevant genes including ALDH1L1, AQP1, MAOB, SCARA3 and the GWAS AD risk gene FERMT2. Thus, while the microglia-APOE cluster is characterized by increased phagocytic and proinflammatory gene expression levels in APOEε4 microglia, similar expression analyses of astrocyte-predominant genes in C0 brains point to a dysregulation of lipid metabolism and the extracellular matrix associated with APOE genotype.

Fig. 4 |. Astrocyte transcriptomic changes associated with APOE genotype in normal aging.

a, Spectral clustering of subject group averaged expression-level z-score for each of 397 astrocyte-predominant genes in ROSMAP subjects with no neuritic plaques (CERAD 0), split by APOE group (ε2: ε2/ε2 + ε2/ε3; ε3: ε3/ε3; and ε4: ε2/ε4 + ε3/ε4 + ε4/ε4). b, Heatmap showing detail of the expression level of cluster 1 and 4 genes from a for all individuals of each APOE group. Note that the 69 genes of cluster 1 overall have higher expression levels in APOEε2 and lower in APOEε4 carriers relative to APOEε3 homozygotes, whereas the 75 genes of cluster 4 overall have higher expression levels in APOEε4 and lower in APOEε2 carriers relative to APOEε3 homozygotes. c,d, Violin plots showing group averaged expression-level z-score of the 69 genes of cluster 1 (c) and the 75 genes of cluster 4 (d) for all ROSMAP DLPFC C0 subjects, by APOE group (n = 36 APOEε2 carriers, n = 113 APOEε3 homozygotes, n = 16 APOEε4 carriers). Error bars indicate the sample mean ±95% normal confidence limits based on t-distribution. e, Dot plots with connecting lines depicting group averaged expression-level z-scores of the 69 genes from cluster 1 in the ROSMAP cohort, split by CERAD NP score and APOE genotype. f, Dot plots with connecting lines depicting group averaged expression-level z-scores of the 75 genes from cluster 4 in the ROSMAP cohort, split by CERAD NP score and APOE genotype. Note that there is much more interindividual variability and more variability across APOE groups compared to the microglia-APOE cluster.

In contrast to microglia, in subjects with frequent NPs (C3), spectral clustering detected only a small cluster (cluster 5) with 68 genes following an ε2 < ε3 < ε4 pattern of expression, but only nine of these 68 genes overlapped with cluster 4 derived from C0 individuals. Additionally, unlike microglia, astrocyte-predominant genes were generally not significantly differentially expressed in ROSMAP APOEε4 or APOEε2 carriers versus APOEε3 homozygotes in either normal (C0) brains or in the presence of frequent NPs (C3 subjects). For example, in C0 subjects, statistical analyses did not reveal significant differences in cluster 1 expression across APOE groups whereas cluster 4 expression was significantly lower in APOEε2 carriers versus APOEε3 homozygotes (−0.32 (0.12), P = 0.006), but did not significantly differ between APOEε4 and APOEε3 homozygotes (0.09 (0.16), P = 0.569). In C3 subjects, APOEε4 carriers tended to have higher expression of cluster 5 than APOEε3 homozygotes (0.17 (0.09), P = 0.069) but APOEε2 carriers did not differ from APOEε3 homozygotes (−0.22 (0.20), P = 0.268) (Fig. 4e,f). Thus, the severity of neuropathology and, perhaps also, microglial responses, rather than the APOE genotype itself, appears to be the primary driver of transcriptomic changes in AD astrocytes.

Testing of microglia-APOE cluster in APOE knock-in mice.

To further test the hypothesis that expression of the APOEε4 allele impacts microglial phenotype, we evaluated published transcriptomics data from APOE knock-in mice and performed new experimental studies on these mice.

Zhao et al.14 investigated the effects of sex, age and APOE alleles in the brain transcriptome of APOE2, −3 and −4 knock-in mice. Only two of the 172 genes of the microglia-APOE cluster identified in ROSMAP C0 individuals were present in APOE-linked modules in this mouse study (IL18BP in the yellow module and ALOX5AP in the tan module, but no genes in the cyan or light cyan modules). Interestingly, we found a highly statistically significant overlap between our human microglia-APOE cluster and their reported aging-associated pink module (P = 2.69 × 10−39, hypergeometric test), with an overlap of 35 genes including some proinflammatory (IFNGR1, IRF8, TLR3) and phagocytosis genes (CD68, CD74, CTSC, LAPTM5, TREM2, TYROBP). The age-associated blue module also had a significant overlap (P = 5.61 × 10−3, hypergeometric test). To test the hypothesis that aging as a stimulus may impact the effect of APOE genotype on glial genes, we performed differential gene expression analysis on their 24-month-old mouse cohort (n = 48, 24 male and 24 female). Notably, only nine genes from the microglia-APOE cluster were significantly increased (adjusted P < 0.05) in APOE4 versus APOE3 knock-in mice, including C3 and CD74. In another study, Nuriel et al. conducted bulk RNA-seq on the entorhinal cortex (EC) and primary visual cortex (PVC) from 14–15-month-old APOE3/4 versus APOE3/3 knock-in mice13. Similarly, we found little similarity between our microglia-APOE cluster and differentially expressed genes from that study (EC, 21 genes including ALOX5AP, C3AR1, CCR5, CD163 and MSR1; PVC, nine genes).

Next, we experimentally examined (via real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT–qPCR)) the expression of 16 relevant microglial and astrocytic genes in brains from APOE knock-in mice, including those representative of the microglia-APOE cluster that highlight the APOE–TREM2–TYROBP axis28–30 (C1qa, C3, Cd68, Cd74, Il1b, Msr1, Spp1, Tgfbr1, Trem2 and Tyrobp), the microglial homeostatic genes Cx3cr1 and P2ry12, the inflammatory marker Tnfa, the astrocyte genes Clu and Gfap and human APOE as control. RT–qPCR data and results are presented in full in Supplementary Table 4.

First, we ran RT–qPCR on bulk brain RNA from 10–12-month-old APOE2, -3 and -4 knock-in mice and observed no significant effect of APOE genotype on the expression levels of any of the genes analyzed (one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey’s post hoc test; Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Gene–gene correlation analyses showed a strong positive correlation (0.6 ≤ r ≤ 0.8) between Cx3cr1 and C1qa and between Cd68, Trem2 and Tyrobp (Supplementary Fig. 2A). Thus, consistent with the RNA-seq results of Zhao et al.14, we confirmed that the baseline expression levels of these genes do not differ across APOE genotypes in mice.

Fig. 5 |. Cross-validation of microglia-APOE cluster in APOE knock-in mice.

a, Bar graphs of relative quantification (2−ΔΔCt) showing mean ± s.e.m. of the expression levels of relevant microglial (underlined in Fig. 3a) and astrocyte genes across 10–12-month-old APOE2 (n = 8), APOE3 (n = 8) and APOE4 (n = 8) knock-in mice, and the results of one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests. Outliers in ΔCt values were detected and discarded from statistical analyses in Clu, huAPOE and Msr1. b, Bar graphs of relative quantification (2−ΔΔCt) showing mean ± s.e.m. of the expression levels of relevant genes across n = 15 biologically independent APOE3 and n = 17 biologically independent APOE4 knock-in mice treated with either PBS or LPS, and the results of two-way ANOVA with genotype, treatment and genotype × treatment interactions. Outliers in ΔCt values were detected and discarded from statistical analyses in C1qa, Cx3cr1 and Tgfbr1. c, Bar graphs of relative quantification (2−ΔΔCt) showing mean ± s.e.m. of the expression levels of relevant genes across APP/PS1 mice crossed with APOE3 (n = 8) and APOE4 (n = 10) knock-in mice, and the results of one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc tests. Outliers in ΔCt values were detected and removed from statistical analyses in Clu, Gfap and Tyrobp. NS, non-significant.

Second, we tested whether the APOEε4 allele is associated with a bias towards a phagocytic/proinflammatory microglial phenotype in the setting of an acute injury such as that caused by a single intraperitoneal injection of LPS31,32. To this end, we injected either LPS or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) into 3–4-month-old APOE3 and APOE4 knock-in mice, euthanized them 3 h later and determined the expression levels of the above genes of interest by RT–qPCR. Two-way ANOVA with APOE, treatment and their interaction as factors demonstrated a statistically significant increase in Ilb1, Tnfa, C1qa, C3, Msr1, Gfap and human APOE in response to LPS injection, whereas levels of the homeostatic microglial genes Cx3cr1 and P2ry12, as well as those of the Trem2-dependent genes Cd74 and Tgfbr1, were significantly decreased following LPS treatment, independently of APOE genotype (that is, P value of genotype × treatment interaction: NS). Remarkably, while no significant differences were detected across APOE alleles in 10–12-month-old APOE knock-in mice, we did observe a statistically significant effect of APOE genotype on Trem2, Tyrobp, P2ry12 and Cd68 (marginal significance), with higher levels in APOE4 versus APOE3 knock-in mice at age 3–4 months, independently of treatment (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 1b). After multiple comparison correction, Tyrobp remained significant and Trem2 was marginally significant (adjusted P = 0.054). Gene–gene correlation analyses showed a very strong positive correlation (0.8 ≤ r ≤ 1.0) between Il1b and Tnfa levels, a moderate to strong positive correlation (0.4 ≤ r ≤ 0.8) between Trem2 and Tyrobp, Trem2 and C1qa, between Trem2 and Cd68 and between C1qa and Cd68 (Supplementary Fig. 2b), suggesting coregulation of these genes in microglia following LPS-induced activation.

Next, to test whether APOE alleles differentially affect microglial gene expression in a chronic neurodegenerative scenario, we compared the brain expression levels of the same selected genes in 12-month-old APP/PS1 × APOE3 versus APP/PS1 × APOE4 knock-in mice, which bear similar NPs to those found in the human AD brain. Trem2, Tyrobp, C1qa, Cd68 and Cd74 were directionally higher (marginally significant, adjusted P < 0.1 after multiple comparison corrections) in APP/PS1 × APOE4 versus APP/PS1 × APOE3 knock-in mice (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 1c). Strong correlations were again observed between Trem2 and Tyrobp, as well as between several other microglia-APOE genes tested (Supplementary Fig. 2c), suggesting that these genes are coregulated across very different stimuli. Taken together, these mouse experiments support the idea that APOE regulates microglial gene expression through the TREM2–TYROBP axis and can bias the microglial transcriptomic phenotype in a scenario of chronic stimulation.

Discussion

Our extensive analyses of available transcriptomic data from human brains identified a cluster of microglial genes that are robustly upregulated in APOEε4 carriers and downregulated in APOEε2 carriers relative to APOEε3 homozygotes, and are enriched in both phagocytosis and proinflammatory genes. The association with the APOEε4 allele was strongest in normal, NP-free brains, suggesting that the APOEε4 allele itself biases microglia toward a disease-associated state in normal aging, perhaps because genetic influences on microglial phenotype are more readily detectable in a homogeneous sample with fewer confounding factors. This APOEε4-linked transcriptomic phenotype of microglia is reminiscent of the concept of microglial priming, defined as a predisposition of microglia towards an exaggerated response following a secondary stimulus33,34, and may in turn exacerbate microglial responses to central nervous system (CNS) lesions such as the NPs and NFTs defining AD. Indeed, although APOE-linked differences were also detectable in AD brains, they were not linearly related to the extent of neuropathological alterations and were apparent only in advanced AD (C3) brains. One possible explanation for this is that the wide variety of AD-related brain changes that can impact the microglial activation state—such as neuronal loss, synaptic loss, NFT development and astrocyte reaction—are probably more heterogeneous in intermediate stages (C1 and C2), thus masking the APOE genotype-specific microglial signature, whereas in advanced AD (C3) these other stimuli may have plateaued, allowing the re-emergence of the APOE-microglia gene signature. Another possibility is that two major waves of microglial activation occur along the course of AD—the first as deposition of Aβ plaques takes place and the second against the pervasive neurofibrillary degeneration—as has been suggested by a neuropathological quantitative study11 and one involving longitudinal multimodal positron emission tomography (PET) imaging (Aβ, tau and TSPO-based PET for glial responses)35.

It is noteworthy that not only inflammation, but virtually all aspects of phagocytosis, were represented in this microglia-APOE cluster: chemotaxis, migration, opsonization, antigen presentation, phagocytosis, autophagosome burst respiration and lysosomal degradation. These observations raise a puzzle: glial uptake is thought to be one of the major Aβ clearance pathways and hence the upregulation of phagocytosis is expected to enhance Aβ clearance, yet the APOEε4 allele correlates with a higher Aβ burden in both in vivo amyloid PET imaging5 and postmortem neuropathological studies3,4,6. However, the APOEε4-associated upregulation of microglial phagocytosis genes might be insufficient to overcome the proaggregant effects of APOE4 on Aβ36–38 and/or APOE4 may lead to defective Aβ uptake and degradation by microglia12,18. Moreover, APOE4 may lead to deleterious phenotypes via enhanced phagocytosis of other substrates. For example, C1Q and C3 have been involved in tagging of synapses for elimination by microglia in AD mouse models39–42, and synaptic loss is the strongest correlate of the severity of cognitive impairment in AD43. Thus, APOEε4 microglia may be more actively engulfing synapses than APOEε2 or APOEε3 microglia, which would result in an earlier age of cognitive decline—a well-known correlate of the APOEε4 allele—and a faster rate of cognitive decline after symptom onset, which we and others have reported44–46.

Also, our microglia-APOE signature notably includes both TREM2 and TYROBP, which highlights the importance of the APOE–TREM2–TYROBP axis. TREM2 loss-of-function mutations have been associated with a two- to threefold increased risk of developing AD47,48. Both APOE and TREM2 are important in the phenotypic switch from homeostatic to AD-associated microglia28–30. AD-linked TREM2 loss-of-function mutations and Trem2 deletion in AD transgenic mice lead to Aβ plaques that are less compact and more neuritic, and have less microglial coverage49–51, whereas their effects on tau NFT pathology remain controversial52–54. Although a phenocopy of these Aβ plaque features has been reported in AD transgenic mice following Apoe deletion55, dense-core Aβ plaques do not differ in size, microglial coverage or neuritic change per plaque between AD APOEε4 carriers and noncarriers10,11,56. On the other hand, TYROBP encodes the adapter protein DAP12, which binds the intracellular domain of TREM2, CD33 and complement receptor 3 (CR3) to mediate their intracellular signal transduction, and is a key regulator of an immune- and microglia-specific network of genes involved in pathogen phagocytosis26. Importantly, Tyrobp genetic deletion in β-amyloidosis and tauopathy transgenic mice is neuroprotective, despite lessening plaque compaction and microglia coverage in the former and increasing phospho-tau levels in the latter57,58. By contrast, Tyrobp overexpression in microglia reduces Aβ plaque burden but also increases phospho-tau burden59. Thus, the observed differences in TREM2 and TYROBP expression levels across APOE genotypes in aged control individuals (higher in APOEε4 carriers and lower in APOEε2 carriers versus APOEε3 homozygotes) could have crucial implications for microglial phenotype, AD pathology and downstream neurodegeneration.

Among the proinflammatory microglial genes upregulated in APOEε4 carriers, Toll-like receptors (TLR1, TLR2 and TLR3) and caspase-1 (CASP1) stand out. Of note, an LPS challenge was reported to increase the secretion of cytokines, including IL-1β, in APOE4 versus APOE2 and APOE3 knock-in mice60, and IL-1β levels were also higher in APOE4 knock-in AD transgenic mice compared to APOE2 and APOE3 knock-in AD mice61. An APOEε4-driven microglial neuroinflammation phenotype has been implicated in accelerated neurodegeneration downstream of tauopathy15,16. Both caspase-1 (CASP1) and IL-1β are key components of the NLRP3 inflammasome, which can drive tau pathology following activation62. In addition, the interferon response was represented in our microglia-APOE cluster by IRF8 and the interferon-γ receptors 1 and 2 (IFNGR1 and IFNGR2, respectively). IRF8 encodes the transcription factor interferon regulatory factor 8, which plays a role in switching microglia to a reactive phenotype in peripheral nerve injury63–65 and was found to be upregulated in AD microglia in a single-nucleus RNA-seq study30.

The association of APOE alleles with astrocyte transcriptome appears more modest in comparison with microglia, as judged by the relative number of DEGs for each glial cell type, but suggested a dysregulation of lipid metabolism and extracellular matrix genes in APOEε4 and APOEε2 carriers versus APOEε3 homozygotes, resembling that found in hiPSC-derived glial cells from APOEε4 versus APOEε3 homozygote individuals19. However, the severity of AD pathology had a greater effect on the astrocyte transcriptome than APOE genotype.

The comparisons of our human microglia-APOE cluster with available RNA-seq data from APOE knock-in mice13,14 rendered very little overlap. Some authors have reported considerable overlap between bulk brain transcriptomic changes in human AD brains and AD mouse models66 and that human and mouse microglial transcriptomes are largely conserved67, while others have found little to no concordance68. Therefore, we attempted to cross-validate our microglia-APOE signature in APOE knock-in mice both with and without stimulus (acute and chronic) via RT–qPCR of relevant genes. While no significant differences across genotypes were observed in the expression levels of the genes analyzed across adult (10–12-month-old) APOE knock-in mice, we did confirm a significant increase in Tyrobp and Trem2 levels in young APOE4 versus APOE3 knock-in mice (regardless of PBS or LPS treatment), and in adult APP/PS1 × APOE4 versus APP/PS1 × APOE3 knock-in mice (although differences in plaque burden between the latter pair might have contributed to these findings). Nonetheless, these results support the relevance of the APOE–TREM2–TYROBP axis in the transcriptomic programs activated by microglia in response to a stimulus32.

It is tempting to speculate that the microglia-APOE gene signature identified in aged brains with no NPs is the result of the cumulative effect of various other insults over the course of the individual’s lifetime (for example, traumatic, infectious, ischemic and so on) on microglia primed by the APOEε4 genetic background. It is also very intriguing that APOEε4 appears to be the evolutionarily conserved allele, with the definitive ε4 site present in the nonhuman primate69. Although corresponding changes in the Arg61 site cast uncertainty about the physiological effects of the Arg112 site in the nonhuman primate, our data raise the question of whether a proinflammatory/phagocytic bias of microglia might carry an evolutionary advantage—for example, fighting CNS infections, removal of neuronal debris after traumatic brain injuries or engulfing and phagocytosing synapses and axons for neural circuit refinement during development. Further studies, perhaps at single-cell resolution, of the nonhuman primate brain may help address this question.

Our study has certain limitations inherent to bulk RNA-seq data. Although it is tempting to ascribe DEGs to gains and losses in the corresponding cell functions, neurodegeneration in AD is associated with shifts in cell subpopulations (for example, decreased proportions of neurons and increased proportions of glial cells) that could explain, at least partially, the observed changes in gene expression levels. Cell-type deconvolution methods are being developed to address this issue70,71. However, our microglia-APOE signature was obtained from subjects with no NPs, implying no overt neurodegeneration other than that associated with normal aging, and therefore limited cell-type shifts. Our cell-type gene assignment, based on the application of expression-level cutoffs to a publicly available transcriptomic dataset of immunopanned cell subpopulations from the human normal brain72, provided robust microglia- and astrocyte-enriched gene sets. Nevertheless, some genes are expressed by more than one cell type and their transcripts may go up or down in one or another cell type in the disease scenario (for example, C3 and APOE itself), and disambiguation of these cell-type-specific changes would require single-cell or single-nucleus transcriptomics data.

In summary, contrasting aging and AD highlights several important biological functions that appear to be different in microglia from APOEε4 and APOEε2 carriers, plausibly correlating with their effect on relative risk for AD, age of onset and even rate of clinical progression. For example, the upregulation of phagocytosis and inflammation gene sets may well place APOEε4 microglia in a predisposition state to react to Aβ plaques and NFTs, as well as to inflammatory and other noxious stimuli. Ultimately, large-scale, single-nucleus RNA-seq of human brains across different stages of AD pathology and APOE genotypes will be required to confirm the influences of the different APOE alleles on glial gene expression programs, and to fully understand how they relate to both AD pathology and clinical progression.

Methods

Bulk brain RNA-seq datasets.

For human data we used the RNA-seq dataset from ROSMAP as the discovery dataset73 and the MSBB RNA-seq dataset as the validation dataset74, which were downloaded from the Accelerating Medicines Partnership–Alzheimer’s Disease (AMP-AD) Knowledge Portal (nos. syn3388564 and syn3157743, respectively). Brie y, ROSMAP data consist of fragments per kilobase exon of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) from DLPFC (Brodmann Area 9) of n = 635 subjects and were adjusted for age, sex and postmortem interval (PMI) using a linear model. The MSBB study provides a trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) from multiple brain regions (IFG, n = 222; STG, n = 240; FP, n = 261; and PHG, n = 215), which are already adjusted for batch, sex, race, age at death, PMI, RNA integrity number, exonic rate and ribosomal RNA rate. Both APOE genotype and clinical and neuropathological data were available for both datasets. The MSBB data across brain regions were combined using the combat function in the sva package in R to adjust for batch or brain region effects. Details of these two cohorts are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 5, respectively.

Table 1 |.

Demographic characteristics and neuropathological findings across APOE groups in the ROSMAP cohort

| Age at death, years (mean ± s.d.) | 87.9 ± 5.4 | 87.0 ± 4.8 | 87.1 ± 4.6 |

| Sex, n female (%) | 63 (72.4) | 242 (62.7) | 102 (63.0) |

| Years of education (mean ± s.d.) | 15.7 ± 3.0 | 16.4 ± 3.6 | 16.7 ± 3.4 |

| CERAD NP score, n (%) | |||

| C0 | 36 (41.4) | 113 (29.3) | 16 (9.9) |

| C1 | 12 (13.8) | 43 (11.1) | 12 (7.4) |

| C2 | 28 (32.2) | 136 (35.2) | 54 (33.3) |

| C3 | 11 (12.6) | 94 (24.4) | 80 (49.4) |

| Braak NFT stage, n (%) | |||

| Braak 0/I/II | 17 (19.5) | 73 (18.9) | 20 (12.3) |

| Braak III/IV | 65 (74.7) | 241 (62.4) | 81 (50.0) |

| Braak V/VI | 5 (5.7) | 72 (18.7) | 61 (37.7) |

| Comorbid pathologies, n (%) | |||

| Cerebral amyloid angiopathy (1/0/NA) | 33 (37.9)/54 (62.1)/0 (0) | 114 (29.5)/272 (70.5)/0 (0) | 91 (56.2)/71 (43.8)/0 (0) |

| Arteriolosclerosis (1/0/NA) | 47 (54)/39 (44.8)/1 (1.1) | 151 (39.1)/232 (60.1)/3 (0.8) | 61 (37.7)/100 (61.7)/1 (0.6) |

| Lewy body pathology (1/0/NA) | 12 (13.8)/73 (83.9)/2 (2.3) | 79 (20.5)/293 (75.9)/14 (3.6) | 38 (23.5)/116 (71.6)/8 (4.9) |

| TDP-43 pathology (1/0/NA) | 37 (42.5)/41 (47.1)/9 (10.3) | 167 (43.3)/187 (48.4)/32 (8.3) | 85 (52.5)/58 (35.8)/19 (11.7) |

| Hippocampal sclerosis (1/0/NA) | 7 (8)/79 (90.8)/1 (1.1) | 19 (4.9)/364 (94.3)/3 (0.8) | 21 (13)/140 (86.4)/1 (0.6) |

Cerebral amyloid angiopathy: 0, none/mild; 1, moderate/severe; NA, missing or unknown. Arteriolosclerosis: 0, none/mild; 1, moderate/severe; NA, missing or unknown. Lewy body pathology: 0, not present; 1, present, NA, missing or unknown. TDP-43 pathology: 0, none; 1, present; NA, missing or unknown. Hippocampal sclerosis: 0, not present; 1, present; NA, missing or unknown.

We also used the following mouse datasets for comparison with human results: a whole-brain bulk RNA-seq study on APOE2, APOE3 and APOE4 knock-in mice14 downloaded from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (no. syn15682620) and bulk RNA-seq data from entorhinal and primary visual cortex of 14–15-month-old APOE3/3 and APOE3/4 knock-in mice13 downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (no. GSE102334 ).

Gene expression analysis.

To assign genes to the appropriate cell type—microglia or astrocytes—we took advantage of the transcriptomic database of human brain cell subpopulations developed by the Barres laboratory using the immunopanning technique72. We considered a gene microglial (or astrocytic) if its level of expression was ≥1.5-fold higher in microglia (or astrocytes) relative to the sum of its expression in all other cell types—that is, neurons, oligodendrocytes, endothelial cells and astrocytes (or microglia). We removed lowly expressed genes (FPKM < 0.1). These criteria rendered 519 microglia-predominant and 397 astrocyte-predominant genes (Supplementary Table 6).

Because activated microglia and reactive astrocytes in the AD brain cluster within and around dense-core NPs9–11, subjects were classified according to their CERAD NP score—that is, none (C0), sparse (C1), moderate (C2) and frequent (C3) NPs75—and their microglial and astrocytic transcriptomes were compared across APOE genotypes within each of these CERAD NP scores. Similar analyses were performed using the Braak NFT staging system76.

We performed two separate analyses: spectral clustering and differential expression analysis. Spectral clustering is a dimensionality-reduction technique that uses the similarity matrix of the data, in this case the relative similarity of the expression-level data (average z-scores of all individuals in each APOE group) for each pair of genes, to identify clusters of coexpressed genes. Spectral clustering was performed using the SNFtool package77. We also tested the average z-score of cluster genes using a linear model. DEGs were identified using limma78 as those with a statistically significant difference in expression level (unadjusted P < 0.05) between the APOEε4 or APOEε2 group with the APOEε3 homozygotes as reference group, after adjusting for CERAD NP score (or Braak NFT stage), as shown below:

The APOEε4 group comprised ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4 and ε4/ε4 subjects whereas the APOEε2 group consisted of ε2/ε2 and ε2/ε3 individuals. We included APOEε2/ε4 carriers within the APOEε4 group given the genetic evidence regarding the dominant effect of the ε4 allele over the ε2 (refs.3,6). Multiple comparison corrections were performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg method79. Plots were generated using ggplot2, and heatmaps with pheatmap packages.

Animals.

We used three groups of APOE knock-in mice expressing human APOEε2, APOEε3 or APOEε4 in the locus of the murine Apoe gene80. A group of 10–12-month-old mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, perfused with ice-cold PBS and their brain tissue was collected for RNA purification and RT–qPCR. Another group, of 3–4-month-old mice, were injected intraperitoneally with either LPS (1 g kg−1) or PBS as control, then euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation 3 h following the injection. The final mouse group was created by backcrossing APP/PS1 transgenic mice81, which develop plaques at around 6 months of age, with APOE3 or APOE4 knock-in mice. These APP/PS1 × APOE knock-in mice, aged 10–12 months, were then euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, perfused with ice-cold PBS and brains were collected for RT–qPCR. Each group included a total of eight mice (four males and four females), and no statistical method was used to predetermine sample size. Mice were housed in an animal facility with controlled conditions of temperature and humidity, 12/12-h dark/light cycle and ad libitum access to food and water. All animal experiments were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care following the guidelines set forth by the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (no. 2006n000178).

RT–qPCR.

RNA was extracted from a slice of forebrain using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and eluted in 80 μl of nuclease-free water. RNA concentration was assessed using the DeNovix DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix) and diluted to a standard concentration of 7.1 ng μl−1 for each sample. RNA was retrotranscribed to complementary DNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). RT–qPCR was conducted with RT2 SYBR Green Mastermix fluorescent dye (Qiagen) and QuantiTect primers (Qiagen), as listed in Supplementary Table 7, in the BioRad CFX96 Real-Time Detection System. The sequence began with a 10-min incubation at 95 °C to activate the DNA polymerase enzyme. Fluorescence data collection then commenced with 40 cycles of alternating 15 s at 95 °C and 60 s at 60 °C. Each mouse RNA sample was run in duplicate, and the average expression was computed. The ΔΔCt relative quantification method was used to calculate gene expression. Gtf2b and Gapdh were used as housekeeping genes included in the RT2-Profiler array to normalize for RNA amount. Briefly, the geometric mean of Ct values of these reference genes was calculated for each mouse and subtracted from the Ct value of each target gene, yielding ΔCt values. For each gene, the average ΔCt value in APOE3 knock-in mice (or, for mice subjected to LPS versus PBS stimulus, the average ΔCt value in APOE3 knock-in PBS-treated mice) was then subtracted from each sample’s ΔCt value to obtain ΔΔCt values. The relative quantification (RQ) value was calculated as 2–ΔΔCt.

Statistics and reproducibility.

Expression data (ΔCt) from RT–qPCR experiments were analyzed with one-way ANOVA for the untreated 10–12-month-old APOE knock-in mice and APP/PS1 × APOE knock-in mice, followed by a post hoc Tukey honestly significant difference (HSD) test. We applied two-way ANOVA with the terms genotype, treatment and genotype × treatment interaction for the 3–4-month-old LPS- versus PBS-treated APOE knock-in mice, followed by a post hoc Tukey HSD test. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05. Multiple comparison corrections were performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg method79. Outliers were detected using the Grubbs test and excluded from analyses. Gene–gene correlations were computed using Spearman’s correlation, and the resulting correlation coefficients were used to generate heatmaps followed by hierarchical clustering. All analyses were performed in R v.4.0.2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The results published here are in whole or in part based on data obtained from the AD Knowledge Portal (https://adknowledgeportal.org). ROSMAP data were provided by the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, USA. Data collection was supported through funding by NIA grant nos. P30AG10161 (ROS), R01AG15819 (ROSMAP; genomics and RNA-seq), R01AG17917 (MAP), R01AG30146, R01AG36042 (5hC methylation, ATAC-seq), RC2AG036547 (H3K9Ac), R01AG36836 (RNA-seq), R01AG48015 (monocyte RNA-seq), RF1AG57473 (single-nucleus RNA-seq), U01AG32984 (genomic and whole-exome sequencing), U01AG46152 (ROSMAP AMP-AD, targeted proteomics), U01AG46161(TMT proteomics), U01AG61356 (whole-genome sequencing, targeted proteomics, ROSMAP AMP-AD), the Illinois Department of Public Health (ROSMAP) and the Translational Genomics Research Institute (genomic). Additional phenotypic data can be requested at www.radc.rush.edu. MSBB data were generated from postmortem brain tissue collected through the Mount Sinai VA Medical Center Brain Bank and were provided by E. Schadt from Mount Sinai School of Medicine. This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (nos. K08AG064039 to A.S.-P., T32AG000222-27 to R.J.J. and P30AG062421 to S.D. and B.T.H.), the Alzheimer’s Association (nos. AACF-17-524184 and AACF-17-524184-RAPID to A.S.-P.), the JPB Foundation (to B.T.H.) and the Jack Satter Foundation (to A.S.-P. and S.D.).

Footnotes

Code availability

Code for all data analyses is available on GitHub at https://mindds.github.io/apoe-glia.

Reporting Summary. Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Additional information

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-021-00123-6.

Peer review information Nature Aging thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

ROSMAP and MSBB RNA-seq data are available from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (https://doi.org/10.7303/syn3388564 and https://doi.org/10.7303/syn3157743, respectively). Mouse RNA-seq data from Zhao et. al. are available at the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (https://doi.org/10.7303/syn20808171), and those from Nuriel et al. at Gene Expression Omnibus (no. GSE102334). The data from our APOE knock-in mice are available in Supplementary Table 4.

References

- 1.Kunkle BW et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat. Genet 51, 414–430 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamazaki Y, Zhao N, Caulfield TR, Liu C-C & Bu G Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat. Rev. Neurol 15, 501–518 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiman EM et al. Exceptionally low likelihood of Alzheimer’s dementia in APOE2 homozygotes from a 5,000-person neuropathological study. Nat. Commun 11, 667 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Serrano-Pozo A, Qian J, Monsell SE, Betensky RA & Hyman BT APOEε2 is associated with milder clinical and pathological Alzheimer disease. Ann. Neurol 77, 917–929 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ossenkoppele R et al. Prevalence of amyloid PET positivity in dementia syndromes: a meta-analysis. JAMA 313, 1939–1949 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg TE, Huey ED & Devanand DP Association of APOE e2 genotype with Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s neurodegenerative pathologies. Nat. Commun 11, 4727 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.West HL, Rebeck GW & Hyman BT Frequency of the apolipoprotein E epsilon 2 allele is diminished in sporadic Alzheimer disease. Neurosci. Lett 175, 46–48 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Serrano-Pozo A, Das S & Hyman BT APOE and Alzheimer’s disease: advances in genetics, pathophysiology, and therapeutic approaches. Lancet Neurol. 20, 68–80 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serrano-Pozo A et al. Reactive glia not only associates with plaques but also parallels tangles in Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Pathol 179, 1373–1384 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serrano-Pozo A et al. Differential relationships of reactive astrocytes and microglia to fibrillar amyloid deposits in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 72, 462–471 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serrano-Pozo A, Betensky RA, Frosch MP & Hyman BT Plaque-associated local toxicity increases over the clinical course of Alzheimer disease. Am. J. Pathol 186, 375–384 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin Y-T et al. APOE4 causes widespread molecular and cellular alterations associated with Alzheimer’s disease phenotypes in human iPSC-derived brain cell types. Neuron 98, 1141–1154 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nuriel T et al. The endosomal–lysosomal pathway Is dysregulated by APOE4 expression in vivo. Front. Neurosci 11, 702 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao N et al. Alzheimer’s risk factors age, APOE genotype, and sex drive distinct molecular pathways. Neuron 106, 727–742 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Y et al. ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature 549, 523–527 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Y et al. Microglia drive APOE-dependent neurodegeneration in a tauopathy mouse model. J. Exp. Med 216, 2546–2561 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitz NF et al. Trem2 deficiency differentially affects phenotype and transcriptome of human APOE3 and APOE4 mice. Mol. Neurodegener 15, 41 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konttinen H et al. PSEN1ΔE9, APPswe, and APOE4 confer disparate phenotypes in human iPSC-derived microglia. Stem Cell Rep. 13, 669–683 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Julia TCW et al. Cholesterol and matrisome pathways dysregulated in human APOE ε4 glia. Preprint at bioRxiv 10.1101/713362 (2019). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Olah M et al. A transcriptomic atlas of aged human microglia. Nat. Commun 9, 539 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefterov I et al. APOE2 orchestrated differences in transcriptomic and lipidomic profiles of postmortem AD brain. Alzheimers Res. er 11, 113 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Conway OJ et al. ABI3 and PLCG2 missense variants as risk factors for neurodegenerative diseases in Caucasians and African Americans. Mol. Neurodegener 13, 53 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sims R et al. Rare coding variants in PLCG2, ABI3, and TREM2 implicate microglial-mediated innate immunity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Genet 49, 1373–1384 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dalmasso MC et al. Transethnic meta-analysis of rare coding variants in PLCG2, ABI3, and TREM2 supports their general contribution to Alzheimer’s disease. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 55 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haure-Mirande J-V et al. Integrative approach to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: deficiency of TYROBP in cerebral Aβ amyloidosis mouse normalizes clinical phenotype and complement subnetwork molecular pathology without reducing Aβ burden. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 431–446 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang B et al. Integrated systems approach identifies genetic nodes and networks in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Cell 153, 707–720 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han SH et al. Apolipoprotein E is present in hippocampal neurons without neurofibrillary tangles in Alzheimer’s disease and in age-matched controls. Exp. Neurol 128, 13–26 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keren-Shaul H et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell 169, 1276–1290 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krasemann S et al. The TREM2-APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity 47, 566–581 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou Y et al. Human and mouse single-nucleus transcriptomics reveal TREM2-dependent and TREM2-independent cellular responses in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Med 26, 131–142 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srinivasan K et al. Untangling the brain’s neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative transcriptional responses. Nat. Commun 7, 11295 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang SS et al. Microglial translational profiling reveals a convergent APOE pathway from aging, amyloid, and tau. J. Exp. Med 215, 2235–2245 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heneka MT et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 14, 388–405 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perry VH & Holmes C Microglial priming in neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol 10, 217–224 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ismail R et al. The relationships between neuroinflammation, beta-amyloid and tau deposition in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal PET study. J. Neuroinflammation 17, 151 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hashimoto T et al. Apolipoprotein E, especially apolipoprotein E4, increases the oligomerization of amyloid β peptide. J. Neurosci 32, 15181–15192 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hori Y, Hashimoto T, Nomoto H, Hyman BT & Iwatsubo T Role of apolipoprotein E in B-amyloidogenesis: isoform-specific effects on protofibril to fibril conversion of Aβ in vitro and brain Aβ deposition in vivo. J. Biol. Chem 290, 15163–15174 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu C-C et al. ApoE4 accelerates early seeding of amyloid pathology. Neuron 96, 1024–1032 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hong S et al. Complement and microglia mediate early synapse loss in Alzheimer mouse models. Science 352, 712–716 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dejanovic B et al. Changes in the synaptic proteome in tauopathy and rescue of tau-induced synapse loss by C1q antibodies. Neuron 100, 1322–1336 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu T et al. Complement C3 is activated in human AD brain and is required for neurodegeneration in mouse models of amyloidosis and tauopathy. Cell Rep. 28, 2111–2123 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shi Q et al. Complement C3 deficiency protects against neurodegeneration in aged plaque-rich APP/PS1 mice. Sci. Transl. Med 9, eaaf6295 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serrano-Pozo A, Frosch MP, Masliah E & Hyman BT Neuropathological alterations in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med 1, a006189 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stone DJ, Molony C, Suver C, Schadt EE & Potter WZ ApoE genotyping as a progression-rate biomarker in phase II disease-modification trials for Alzheimer’s disease. Pharmacogenomics J. 10, 161–164 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu L et al. APOE ε4, Alzheimer’s disease pathology, cerebrovascular disease, and cognitive change over the years prior to death. Psychol. Aging 28, 1015–1023 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qian J, Betensky RA, Hyman BT & Serrano-Pozo A Association of APOE genotype with heterogeneity of cognitive decline rate in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 96, e2414–e2428 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guerreiro R et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med 368, 117–127 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jonsson T et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med 368, 107–116 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y et al. TREM2-mediated early microglial response limits diffusion and toxicity of amyloid plaques. J. Exp. Med 213, 667–675 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parhizkar S et al. Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque-associated ApoE. Nat. Neurosci 22, 191–204 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leyns CEG et al. TREM2 function impedes tau seeding in neuritic plaques. Nat. Neurosci 22, 1217–1222 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bemiller SM et al. TREM2 deficiency exacerbates tau pathology through dysregulated kinase signaling in a mouse model of tauopathy. Mol. Neurodegener 12, 74 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leyns CEG et al. TREM2 deficiency attenuates neuroinflammation and protects against neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 11524–11529 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gratuze M et al. Impact of TREM2R47H variant on tau pathology-induced gliosis and neurodegeneration. J. Clin. Invest 130, 4954–4968 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ulrich JD et al. ApoE facilitates the microglial response to amyloid plaque pathology. J. Exp. Med 215, 1047–1058 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Serrano-Pozo A et al. Stable size distribution of amyloid plaques over the course of Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol 71, 694–701 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Haure-Mirande J-V et al. Deficiency of TYROBP, an adapter protein for TREM2 and CR3 receptors, is neuroprotective in a mouse model of early Alzheimer’s pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 134, 769–788 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Audrain M et al. Integrative approach to sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: deficiency of TYROBP in a tauopathy mouse model reduces C1q and normalizes clinical phenotype while increasing spread and state of phosphorylation of tau. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 1383–1397 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Audrain M et al. Reactive or transgenic increase in microglial TYROBP reveals a TREM2-independent TYROBP–APOE link in wild-type and Alzheimer’s-related mice. Alzheimers Dement. 17, 149–163 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu Y et al. APOE genotype alters glial activation and loss of synaptic markers in mice. Glia 60, 559–569 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodriguez GA, Tai LM, LaDu MJ & Rebeck GW Human APOE4 increases microglia reactivity at Aβ plaques in a mouse model of Aβ deposition. J. Neuroinflammation 11, 111 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ising C et al. NLRP3 inflammasome activation drives tau pathology. Nature 575, 669–673 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Masuda T et al. IRF8 is a critical transcription factor for transforming microglia into a reactive phenotype. Cell Rep. 1, 334–340 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grubman A et al. A single-cell atlas of entorhinal cortex from individuals with Alzheimer’s disease reveals cell-type-specific gene expression regulation. Nat. Neurosci 22, 2087–2097 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mathys H et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 570, 332–337 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wan Y-W et al. Meta-analysis of the Alzheimer’s disease human brain transcriptome and functional dissection in mouse models. Cell Rep. 32, 107908 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gosselin D et al. An environment-dependent transcriptional network specifies human microglia identity. Science 356, eaal3222 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Friedman BA et al. Diverse brain myeloid expression profiles reveal distinct microglial activation states and aspects of Alzheimer’s disease not evident in mouse models. Cell Rep. 22, 832–847 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gearing M, Rebeck GW, Hyman BT, Tigges J & Mirra SS Neuropathology and apolipoprotein E profile of aged chimpanzees: implications for Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9382–9386 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patrick E et al. Deconvolving the contributions of cell-type heterogeneity on cortical gene expression. PLoS Comput. Biol 16, e1008120 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang X et al. Deciphering cellular transcriptional alterations in Alzheimer’s disease brains. Mol. Neurodegener 15, 38 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang Y et al. Purification and characterization of progenitor and mature human astrocytes reveals transcriptional and functional differences with mouse. Neuron 89, 37–53 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Jager PL et al. A multi-omic atlas of the human frontal cortex for aging and Alzheimer’s disease research. Sci. Data 5, 180142 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang M et al. The Mount Sinai cohort of large-scale genomic, transcriptomic and proteomic data in Alzheimer’s disease. Sci. Data 5, 180185 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mirra SS et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 41, 479–486 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Braak H & Braak E Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 82, 239–259 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang B et al. Similarity network fusion for aggregating data types on a genomic scale. Nat. Methods 11, 333–337 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ritchie ME et al. limma Powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, e47 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Benjamini Y & Hochberg Y Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol 57, 289–300 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Huynh T-PV et al. Lack of hepatic apoE does not influence early Aβ deposition: observations from a new APOE knock-in model. Mol. Neurodegener 14, 37 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jankowsky JL et al. Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum. Mol. Genet 13, 159–170 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

ROSMAP and MSBB RNA-seq data are available from the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (https://doi.org/10.7303/syn3388564 and https://doi.org/10.7303/syn3157743, respectively). Mouse RNA-seq data from Zhao et. al. are available at the AMP-AD Knowledge Portal (https://doi.org/10.7303/syn20808171), and those from Nuriel et al. at Gene Expression Omnibus (no. GSE102334). The data from our APOE knock-in mice are available in Supplementary Table 4.