Abstract

Purpose:

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) has committed to advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) by retaining and advancing Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) individuals in the discipline of communication sciences and disorders (CSD), amid critical shortages of faculty to train the next generation of practitioners and researchers. Publishing research is central to the recruitment, retention, and advancement of faculty. However, inequity in peer review may systematically target BIPOC scholars, adding yet another barrier to their success as faculty. This viewpoint article addresses the challenge of inequity in peer review and provides some practical strategies for developing equitable peer-review practices. First, we describe the demographics of ASHA constituents, including those holding research doctorates, who would typically be involved in peer review. Next, we explore the peer-review process, describing how inequity in peer review may adversely impact BIPOC authors or research with BIPOC communities. Finally, we offer real-world examples of and a framework for equitable peer review.

Conclusions:

Inequity at the individual and systemic levels in peer review can harm BIPOC CSD authors. Such inequity has effects not limited to peer review itself and exerts long-term adverse effects on the recruitment, retention, and advancement of BIPOC faculty in CSD. To uphold ASHA's commitment to DEI and to move the discipline of CSD forward, it is imperative to build equity into the editorial structure for publishing, the composition of editorial boards, and journals content. While we focus on inequity in CSD, these issues are relevant to other disciplines.

The discipline of communication sciences and disorders (CSD) has faced underrepresentation of Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) in faculty positions amid a broader critical shortage of academic researchers to train future practitioners and researchers (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association [ASHA], 2019). ASHA (n.d.-a) has publicly pledged to support diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) as part of antiracist efforts. Oftentimes, these initiatives focus on recruitment and retention of BIPOC students and practitioners but not faculty (Mishra et al., 2021). In particular, publishing research is central for faculty to advance in the profession (Taffe & Gilpin, 2021). Inequity in peer review occurs when BIPOC faculty face undue hardship in the peer-review process that is unrelated to the scientific evaluation of their manuscript to greater extents than white or white-passing faculty (i.e., BIPOC who others may perceive as white; Silbiger & Stubler, 2019). Minimizing inequity in the peer-review process is essential for developing solutions to recruit, retain, and advance BIPOC faculty in CSD. To address this need, this viewpoint article describes inequity in peer review and offers solutions for developing equitable peer-review practices, with a specific focus on ASHA journals, given their centrality in CSD.

BIPOC Underrepresentation in CSD

Intersectionality Theory

To understand inequity in peer review, we use intersectionality theory, which posits that individuals may have intersecting identities tied to marginalization (Crenshaw, 1991), as a critical lens for framing the experiences of BIPOC. For example, while all female faculty in CSD may face challenges in advancing in their careers (Rogus-Pulia et al., 2018), Black female faculty may face multiple challenges—and marginalization—tied to experiences of being Black and being female, respectively, in a predominantly white profession and academy (Crenshaw, 1991). Intersectionality shifts the dialogue from trying to interpret individual intentions underlying specific instances of inequity to examining how systems effect marginalization. It is also necessary to consider how policies and processes as parts of systems may lead to intersectional inequity, particularly with regard to racialized outcomes (Powell, 2012). For example, real estate policies that make no mention of race—only income—have systematically excluded racial/ethnic minority groups, as income level in the United States tends to vary by race (Powell, 2012). Peer-review policies could similarly affect racialized outcomes. Currently, there is a dearth of empirical data available to understand inequity in peer review in CSD, particularly as related to understanding intersectional underrepresentation among those most likely to conduct research (i.e., PhD holders).

Underrepresentation as an Ethical Issue

As per the ASHA Code of Ethics (ASHA, 2016), members are obligated not to discriminate against individuals with communication needs based on their identities, such as race, ethnicity, language background, gender, and sexuality. Fulfilling these ethical obligations necessarily involves having a body of diverse professionals who can directly speak to those experiences. Yet as the demographics of ASHA constituents illustrate (ASHA, 2021e, 2021f), the discipline faces a shortage of CSD professionals who can train the next generation of practitioners and researchers as culturally sensitive professionals who can appreciate—and validate—the many ways in which individuals in the population may be diverse. Though allies can partner with diverse professionals of marginalized backgrounds to advance ecologically valid research and practice, only those from marginalized backgrounds will ever have the lived experiences that are the most relevant to understanding diversity and advancing equity and justice (Wilbur et al., 2020).

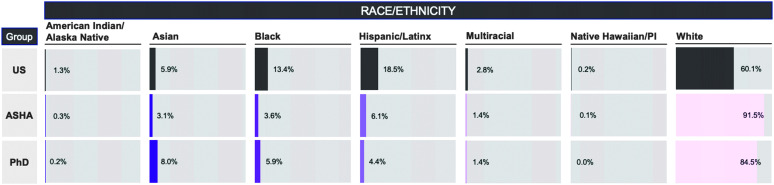

ASHA (2021e, 2021f) has provided statistics indicating that all BIPOC are underrepresented within its membership base relative to the U.S. population U.S. Census Bureau, 2019); see Figure 1. As for the ASHA constituents with PhDs in the United States who work primarily at colleges and universities (ASHA, 2021f), the percentages of each racial and ethnic group translate to extremely small numbers and percentages within the full ASHA membership, let alone the U.S. population: 0.2% American Indian/Alaska Native equals 4 (0.00% within ASHA), 8.1% Asian equals 179 (0.08% within ASHA), 5.9% Black equals 130 (0.06% within ASHA), 4.4% Hispanic/Latinx equals 97 (0.05% within ASHA), 1.4% multiracial equals 31 (0.01% within ASHA), and 0% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander equals 0 (0% within ASHA). As only a broad measure, these statistics underline the need for intersectional data to understand the nuanced ways in which discrimination can play out in higher education in ways and lead to such underrepresentation in speech, language, and hearing faculty in academia. (Bauer et al., 2021). There is no doubt a nearly unlimited number of scenarios that have played out across academia, but as one example that arose during the course of writing this article, an international Asian student shared with the authors that clinical faculty members repeatedly told her she should not become a clinician and made no attempt to make their teaching culturally sensitive. Though that student is now thriving in a doctoral program with an international expert on language and communication in a clinical population, who adjusted her advising to be culturally sensitive, she was effectively pushed out of clinical practice. More broadly in higher education, available data does show that all BIPOC are underrepresented in the upper levels of academia across fields (Ginther et al., 2018). Despite evidence that BIPOC faculty experience persistent challenges due to systemic discrimination throughout their careers (Gosztyla et al., 2021; Mishra et al., 2021), information on how BIPOC PhD holders in CSD may be underrepresented in other ways is unavailable (e.g., by whether they reach associate professor; Buchanan & Wiklund, 2020; Ginther et al., 2018). Data for students pursuing a PhD are similarly nonintersectional and merely reported as white, racial/ethnic minority, and international (Council of Academic Programs in Communication Sciences and Disorders & ASHA, 2020). Nevertheless, the data that are publicly available clearly indicate that BIPOC scholars who would be expected to participate in peer review as part of their career are underrepresented.

Figure 1.

Racial and ethnic representation in the U.S. population, ASHA constituents (N = 212,534; ASHA, 2021e, 2021f), and ASHA constituents with PhDs in the United States working primarily at colleges or universities (N = 2,205).

Experiences of marginalization, including inequity in peer review, may contribute to BIPOC underrepresentation in the academy. Although career pathways are often nonlinear (McGlynn, 2014), there are successively higher expectations for career progression. That is, transitioning from the graduate to postgraduate level typically requires evidence of research and teaching productivity depending on the postgraduate position. To earn promotion and tenure from assistant to full professor, faculty must meet benchmarks, such as having sufficient journal publications and grants, established by their department and institution (Willis et al., 2021). Individuals with marginalized identities may face undue bias in progressing to each next step because of perpetually experiencing inequity, leading to difficulty focusing on and achieving career goals, especially as compared to someone not experiencing that same inequity (Mishra et al., 2021). Specifically, the cyclic fashion of research productivity may be systematically burdensome for BIPOC faculty. For instance, conducting research with clinical populations often requires funding; these costs may be greater if working with BIPOC populations (due to the time and effort required to overcome distrust of research among BIPOC communities; Erves et al., 2017; Wendler et al., 2005), which BIPOC researchers are more likely to do than white researchers (Hoppe et al., 2019). Obtaining such funding requires a record of relevant publications (Ginther et al., 2018). Without publications and grant funding, the researcher may not progress to next levels in academia. Thus, BIPOC authors may face hurdles in their ability to publish and be successful in the academy (Henry et al., 2021; Taffe & Gilpin, 2021; Willis et al., 2021).

Bias in Peer Review

We acknowledge that many researchers face difficulties in advancing their careers in academia, including in the critical area of publishing research. Yet, there remains undue systemic bias in the publication process that adversely impacts BIPOC authors and research with BIPOC communities, including that which is used to develop evidence-based practice and the scientific base at large (Buchanan et al., 2021b). We focus on inequity in peer review, one critical part of the entire research enterprise necessary for advancement in the academy. We recognize there are additional related issues, including how authors as academics seek out those who are similar to themselves in many ways (i.e., homophily) and what editors themselves see as challenges to equity in peer review, but these are beyond the scope of the present article. Rather, we begin by highlighting previous work examining intersectional biases in peer review in allied disciplines. Then, we turn to lived experiences of bias in peer review in CSD, to provide case examples of where and how bias can emerge in editorial board composition, reviewer comments, and manuscript decisions.

Intersectional Bias in Peer Review

Prior work in allied disciplines has found that BIPOC authors or authors working with BIPOC participants can experience bias in academic publishing (Gosztyla et al., 2021; Henry et al., 2021; Resnik & Elmore, 2016). In the absence of publicly available empirical data from ASHA and other CSD journals, we turn to data from other disciplines. Across 7 years of manuscripts from the Journal of Management, manuscripts where authors included “diversity” as a topic area were 12 times more likely to get a “reject” than “accept” decision and 15 times more likely to get a “revise” than “accept” decision in the first two rounds of review compared to similar papers where authors did not include “diversity” as a topic area (King et al., 2018). Importantly, the disparities between manuscript types manifested in the review process itself and not the ultimate, end-state rates of acceptance and rejection, thus highlighting the importance of taking a nuanced approach to intersectional bias (King et al., 2018). Further, diversity-related manuscripts are likely to be published in less prestigious journals, while manuscripts by white authors with predominantly white populations are likely to be published in prestigious journals—even with smaller sample sizes (King et al., 2018; Roberts et al., 2020).

While beyond the primary focus of this article, white reviewers and editors may feel threatened, explicitly or subconsciously, by research with BIPOC communities and by BIPOC authors (Dupree & Kraus, 2020; King et al., 2018). Specifically, a white reviewer or editor may perceive diversity-related manuscripts as advancing the “out-group” over the “in-group” and hold such manuscripts to a higher standard than non–diversity-related manuscripts (King et al., 2018). Further, editors and reviewers may not view this work as valuable (Giwa Onaiwu, 2020). These explanations run counter to the proposal that BIPOC authors will overcome adversity if they complete enough diversity programming aiming to support authors of underrepresented backgrounds in achieving some benchmark that primarily white academia establishes (Valantine & Collins, 2015). To minimize inequity in peer review, efforts must extend beyond race—and developing programming for authors of racially underrepresented backgrounds—alone.

Intersecting Identities

Gender

As a construct, individuals varying by gender may each experience different levels and types of marginalization tied to inequity in peer review (Crenshaw, 1991). While there is only limited evidence of gender bias in peer review (Resnik & Elmore, 2016), BIPOC status intersecting with gender can give rise to worse experiences in career progression in the academy (e.g., Rogus-Pulia et al., 2018). For example, unethical reviewer behavior in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics has shown differentially negative effects on actual productivity in terms of publications per year and career progression (Silbiger & Stubler, 2019). While men of color suffered negative effects, nonbinary authors experienced more negative effects, and BIPOC women and nonbinary BIPOC experienced the most negative effects (Silbiger & Stubler, 2019). Thus, inequity in peer review is not a “one-size-fits-all” construct, but rather, motivates the need for intersectional data and approaches to mitigate bias.

Prestige

Professional status may compound BIPOC marginalization. BIPOC may be less likely than white peers to be hired at prestigious institutions and to reach the upper echelons of academia, which would grant them access to networks and resources (Ginther et al., 2018). This has implications for peer review. For example, analysis of all submissions to Frontiers across 5 years revealed that authors from more prestigious institutions received higher scores in peer review than those at less prestigious ones (Walker et al., 2015). Reviewers are more likely to advocate for papers from more prestigious institutions to advance in the review process in single-blind review, especially when the authors are famous; in contrast, they are less likely to make “accept” decisions than in double-blind review (Tomkins et al., 2017). Further, reviewers are more likely to more favorably review submissions from authors within their network of collaborators (Dondio et al., 2019). Thus, peer review may confound quality with prestige, networks, or even nepotism. A natural conclusion from these findings might be that double-blind review is preferable to single-blind review, because it can mitigate effects of bias due to prestige. However, double-blind review presents its own issues, such as being able to identify authors (Hill & Provost, 2003), especially as areas of research expertise and career trajectories become highly specific. The take-home point is that, regardless of peer-review system (all of which are imperfect), if BIPOC are excluded from professional networks, they may be further marginalized in peer review.

Perceptions of Foreignness

Perceptions of foreignness, in addition to BIPOC status, can give rise to multiple marginalization (see Resnik & Elmore, 2016, for a review). A large-scale survey found that unethical reviewer behavior was pervasive, with comments such as, “The author's last name sounds Spanish. I didn't read the manuscript because I'm sure it's full of bad English” (p. 3; Silbiger & Stubler, 2019). This evidence is consistent with analysis of 5 years of submissions to Frontiers, which showed that authors from English-speaking countries received higher scores in peer review than those in non–English-speaking ones (Walker et al., 2015). Although judging scientific quality by perceptions of English as a first versus additional language status is an issue in CSD and constitutes linguistic bias (Politzer-Ahles et al., 2020), making biased assumptions about language background and race/ethnicity based on the author's name is equally problematic. In all, intersecting identities may give rise to multiple marginalization and exacerbate racialized outcomes in peer review (Powell, 2012).

Lived Examples of Inequity in CSD Peer Review

Because the majority of ASHA constituents, including PhD holders, are not BIPOC, it may be difficult for people to understand and empathize with inequity in peer review. Sharing lived experiences is one practice that permeates our academic and clinical education in our discipline (e.g., case studies of communication disorders used as training examples in the classroom, clinic, and continuing education), and so naturally provides one way to bring to light the inequity that exists. Here, we focus on ASHA journals and a specific top-tier, highly regarded journal in CSD, namely, the Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research (JSLHR). We outline the systems and policies in place that lead to potential points of bias in peer review from when a manuscript is first received to when the author(s) receive an editorial decision, and we share examples of bias experienced by authors of this manuscript.

Editorial Board Composition

Editorial boards play a central role in determining who contributes to the scientific knowledge base and serve as gatekeepers to publication (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020). To illustrate how editorial boards interface with authors in peer review, we describe ASHA's (n.d.-h) procedures for building editorial boards. An editor-in-chief leads each ASHA journal. Editors-in-chief are nominated for this position and appointed by the Journals Board. The Journals Board includes 11 editors-in-chief across the ASHA journals or journal sections; one representative from the standing committee on Clinical Practice Research, Implementation Science, and Evidence-Based Practice; one international member; and one chair (ASHA, n.d.-e). The editors-in-chief and section editors sign contracts listing their roles and responsibilities and receive annual honoraria of $5,000 and $2,500 (or $1,000 for Perspectives editors), respectively, for fulfilling their duties (ASHA, n.d.-f). While service as an editor or editor-in-chief might primarily confer prestige, demonstrate service to the field, and ultimately influences how science is advanced in CSD, these agreements do set up a formal employment relationship, wherein editors-in-chief and editors are independent contractors who agree to the guidelines set forth by their contracts (ASHA, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d).

Next, the editor-in-chief personally recruits section editors, followed by selection of editorial board members in consultation with the editors. For Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, consultation between the editor-in-chief and editors also includes the coordinating committees of each Special Interest Group. For most submitted manuscripts, the editor selects reviewers from the pool of editorial board members, along with occasional ad hoc reviewers as needed. As of 2021, the contracts for editors-in-chief and editors did not explicitly address equity in the editorial board selection process (ASHA, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d). Nevertheless, even without written guidelines, if following ASHA's Code of Ethics (2016) and strategic planning (ASHA, n.d.-b), editorial boards ought to reflect the diversity that ASHA envisions in terms of recruiting and retaining underrepresented populations to the profession, with equitable and inclusive policies in place in the Association (ASHA, n.d.-b). Under this vision, ASHA journals are no exception.

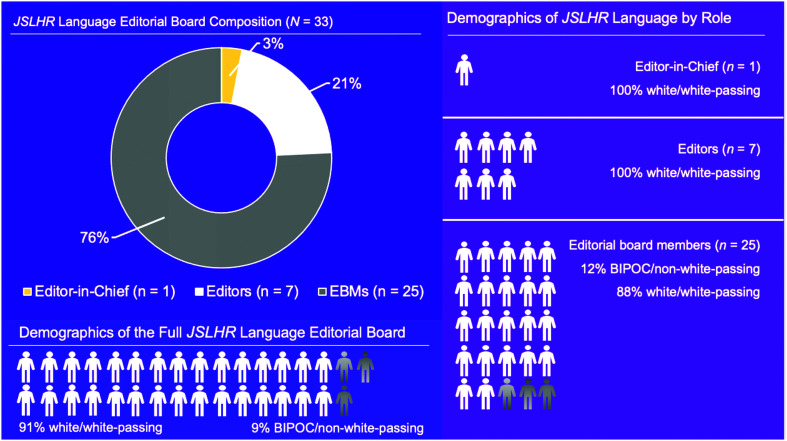

To provide a concrete example, consider the make-up of JSLHR. ASHA journals do not have publicly available demographic information on their editorial board members. Figure 2 shows the perceived editorial board demographics of JSLHR's Language section as of August 2021, with editorial board members' start dates ranging from 2019 to 2021 (ASHA, n.d.-c). To calculate these demographics, two of the present authors—one white/white-passing and one BIPOC/non–white-passing—independently coded each editorial board member as BIPOC/non–white-passing or as white/white-passing using their professional photographs from institutional webpages. There was 97% interrater agreement (i.e., discrepancy in coding one editorial board member). They more conservatively coded the one editorial board member in question as BIPOC/non–white-passing.

Figure 2.

Editorial board perceived demographics for Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research–Language section as of August 2021.

Although judging others by photographs could run the risk of miscategorization, perceptions about race and ethnicity inform how individuals navigate their way through the world. On one hand, race is a social construct that largely relies on how others react to perceived individual differences, rather than to individual differences themselves (Annamma et al., 2013; see Hobbs, 2014, for a review of the ways in which being white-passing in the United States shapes how one navigates in society). Indeed, perceptions about race and ethnicity seem to play out in this way in CSD. For example, a sample of predominantly racial and ethnic minority students in CSD (N = 155) reported experiencing marginalization in terms of being Otherized (i.e., treated as not the norm), facing damaging generalizations from others in their programs (e.g., faculty referring to two Asian students as sisters, despite one being from China and the other from the United States), and facing maltreatment (i.e., statements or actions that negatively impact socioemotional wellbeing or academic success) from faculty and peers alike (Abdelaziz et al., 2021). Given longstanding inequities in racial and ethnic representation in ASHA, there is no reason to believe these experiences—as tied to perceptions about race and ethnicity—change in the professoriate.

The editorial board for JSLHR's Language section (N = 33) has one editor-in-chief, seven editors, and 25 editorial board members. All of the editorial board members with top positions, namely the editor-in-chief (100%) and editors (100%), are white/white-passing. Further, the majority of editorial board members (22 of 25, or 88%) are white/white-passing. In contrast, only three of all 33 editorial board members (9%) are BIPOC or non–white-passing, and they hold the lowest-ranked position on the editorial board. Although having 9% of BIPOC/non–white-passing editorial board members overall may seem comparable to the 8% of BIPOC within ASHA constituents, white/white-passing editorial board members are overrepresented on the JSLHR Language editorial board relative to white PhD holders in ASHA overall (84.5%; ASHA, 2021e).

This demographic comparison only considering PhD holders is critical because editorial board members are unlikely to be individuals without PhDs or individuals not within the ASHA constituency. Qualifications for editors-in-chief and editors explicitly include a history of publications and an established reputation for their research area, and editorial board members are supposed to be area experts with experience reviewing manuscripts who can review at least 8–10 manuscripts per year (ASHA, n.d.-f). These qualifications favor individuals who hold a PhD and are more likely to work in academic research. While more needs to be done to increase BIPOC representation in the ASHA constituency as a whole, even when narrowing our population to those who could be selected for an editorial board position, there is clear discrepancy in race/ethnicity representation. In all, it is unclear how consideration of the many diverse perspectives that ought to inform science influences editorial board composition (King et al., 2018; Rogus-Pulia et al., 2018; Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020). Yet, considering the impact versus the intent of selection processes, lack of diversity in the editorial board can negatively impact equity in peer review. For example, having predominantly white editorial board members might contribute to lack of appreciation for diverse research, which could push BIPOC authors out of top-tier journals. At the same time, given the power of the editorial board, there could be issues of homophily (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020).

Peer Review

Authors seeking to publish must do so within the structure of peer review, which is necessarily a subjective process (Resnik & Elmore, 2016; Smith, 2006). In this section, we describe ASHA journal procedures (ASHA, n.d.-c) and provide examples of how bias in reviewer feedback may have downstream effects. Because the peer-review approach predominantly in use for ASHA journals is single-blind peer review (ASHA, n.d.-c), and because it is impossible to analyze whether peer review leads to racialized outcomes without empirical data (Powell, 2012), it is equally futile to evaluate individual decisions as related to bias without permission to make full manuscripts and reviews publicly available. Reviewer feedback and editorial decision letters for ASHA journals are kept in a black box, which makes it difficult for people in positions of power (i.e., reviewers and editors) to be evaluated or for anyone to identify systemic inequities that could lead to reform of the peer-review system (Vazire, 2019a). Therefore, we provide concrete examples of lived experience to illustrate inequity that emerges in reviewer feedback until such information is made publicly available.

After a manuscript is submitted for peer review, the editor-in-chief reviews its contents and determines whether the manuscript is appropriate for the journal. If the editor-in-chief feels that the material is appropriate, they assign it to an editor for review. In turn, the editor assigns the manuscript to two or three editorial board members or ad hoc reviewers who they feel have appropriate content expertise. The role of reviewers is to report on strengths and weaknesses in the manuscript, covering the appropriateness of the background literature; development of hypotheses when applicable; and the methods, analyses, and interpretations. Specifically, the charge for reviewers is to use a structured peer-review template to (a) provide constructive feedback in a collaborative and collegial spirit to advance the discipline of CSD, (b) be objective in their comments, and (c) respect the intellectual independence of the author (ASHA, n.d.-g). As a subjective process, feedback provision by reviewers may be biased, even when providing feedback using a template. Just because subjectivity is inherent in peer review does not mean that reviews should include biased commentary. We offer several such examples that run counter to ASHA's commitment to antiracism and to ASHA's strategic vision (ASHA, n.d.-a, n.d.-b).

Example 1: Suggesting That Titles Must Include the Word Minorities for Studies Where Participants Are Racial/Ethnic Minorities

Inequity can arise if reviewers conflate participant demographics with the purpose of a paper. For example, a manuscript on language acquisition most likely does not focus on the identities of participants as members of a specific racial or ethnic group. Thus, suggesting that the title should include the word minorities lest it be misleading is irrelevant to the paper. Such feedback could indicate that the reviewer fixated on participant race and ethnicity and subsequently evaluated the manuscript through this lens (King et al., 2018). This characterization marginalizes BIPOC and perpetuates the myth that race is a scientific reality, rather than a social construct that may or may not be relevant to specific aspects of language science (Crenshaw, 1991; Ruedinger et al., 2021). Moreover, such feedback suggests that BIPOC are “Other” and abnormal (Buchanan et al., 2021b; Roberts et al., 2020). While many publications in CSD have all white or predominantly white samples, none include “white” in the title (Buchanan et al., 2021b).

Example 2: Stating That BIPOC Are Likely to Not Speak General American English

Another example of inequity is when reviewers conflate the race and ethnicity of BIPOC participants with language background. For example, assuming that BIPOC are likely to speak variants of English other than General American English—and thus, that researchers working with BIPOC must address variants spoken in their manuscripts—reduces BIPOC to harmful stereotypes. Expecting that variants of English must be a confounding factor for all BIPOC participants, such as Black and African American participants, is antithetical to appreciating the BIPOC in their full representation (Buchanan et al., 2021b; Plaut, 2010). Not all Black people are African American, nor do all African Americans speak African American English. In contrast, white people in the United States speak multiple variants of American English, such as White Middle Class English, Southern White English, and White Working Class English (Barrière et al., 2019; Oetting et al., 2021), yet it is not expected that authors conducting language science with all white or predominantly white samples address variants of spoken English in their manuscripts. In all, focusing on speaker differences only for BIPOC individuals perpetuates the myth that white people are the norm and BIPOC are the “Other” (Buchanan et al., 2021b; Roberts et al., 2020).

Example 3: Instructing the Authors to Use Person-First Language

A third example involves use of preferred terminology that honors the lived experiences of autistic individuals themselves. Many autistic individuals—including autistic researchers—support the use of identity-first language instead of person-first language, as they see being autistic as important to their identities; this movement has led to peer-reviewed papers on anti-ableist guidelines for researchers working with autistic communities (Bottema-Beutel et al., 2021). Recent ASHA publications have used identity-first language, including those from autistic self-advocates discussing why they prefer identity-first language (e.g., Dorsey et al., 2020; Randall, 2021). Further, ASHA adheres to the American Psychological Association (APA, 2020) style guidelines and state that “when an author expresses preference for identity-first language, ASHA honors that preference” (ASHA, n.d.-d). As such, reviewers instructing authors to use person-first terminology—especially if authors provide justification and citations for use of identity-first language—demonstrates a shortcoming in cultural humility and ableism. While it is not expected for reviewers to invariably provide sound feedback, such feedback runs counter to fostering inclusion and to guidance from major professional associations. Furthermore, these types of reviewer comments may be internalized by authors, which continues to perpetuate the idea that BIPOC are not welcome in our discipline and our research.

Editorial Decisions

Finally, after reviewers submit their comments, the role of the section editor is to take those reviewer comments into account in order to inform their decision and to provide specific feedback to the authors in their decision letter, rather than using a generic form letter. The editor can recruit additional reviewers if the original reviewers disagree. In theory, the editor is not merely tallying “votes” from the set of reviewers, but instead is making a decision based on their own experience and expertise, informed by the reviewers' comments. Ideally, throughout the peer-review process, reviewers and editors focus on the science of the manuscript. Deciding whether to advocate for or against a particular manuscript depends, however, on the subjective factor of what excited the reviewers and editors.

If a manuscript receives reviewer feedback like any of the previous examples, a section editor should do two things: consider bias in reviewer feedback in their editorial decision and address reviewer feedback in their communication with the author (ASHA, n.d.-c; Resnik & Elmore, 2016). In ASHA journals, providing only a form letter without any reference to reviewer feedback runs counter to the specific roles and responsibilities that are set forth in agreements with editors (ASHA, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d) and are reinforced in training emphasizing the value of providing personalized feedback. Further, the formulaic nature of a form letter obscures whether an editor fails to see concerns in reviewer comments, such as the examples above, or simply chooses not to address those in their decision-making process or decision letter.

Above action editors are the editors-in-chief, who are ultimately responsible for peer review in the journal for which they hold an editorial role (Buchanan & Wiklund, 2020). In addition to ensuring peer review functions operationally, they have a responsibility to ensure that they minimize bias in peer review, as peer review shapes the scientific literature and evidence base. Passivity on the behalf of the section editor or editor-in-chief in response to cases of biased reviewer feedback effectively encourages it to persist (Roberts & Rizzo, 2021).

Recourse for Authors

When a manuscript is rejected, authors do not have the opportunity to respond to reviewers, nor to share any concern regarding bias in the peer-review process. Some authors may respond to a rejection decision with a letter to the action or section editor and ask the editor to reconsider their decision. However, only those with insider knowledge would consider this informal appeal; such in-group knowledge is unavailable to all, which may enhance biased outcomes. Therefore, we provide official ASHA guidance (n.d.-h).

If an author disagrees with an editorial decision, they may appeal that decision, and the appeal goes straight to the chair of the ASHA Journals Board, who is nominated and approved by the ASHA Committee on Nominations and Elections. There are no protections in place if an author files an appeal. On one hand, the editors-in-chief meet on a standing basis with the chair and other ASHA Journals Board members, such that there is the potential for shared knowledge among all Journals Board members. Further, the vast majority of reviews are single-blind; the reviewers know the identity of the authors but not vice versa. This power dynamic can create negative repercussions for authors beyond the appeal process (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020). For example, if an editor-in-chief or editor felt slighted by an author filing an appeal of a manuscript decision, that feeling might influence their evaluation of the author elsewhere, such as if the author applies for a grant they review or submits another manuscript (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020). Of course, there is the practical issue of authors needing to publish for their career (Willis et al. 2021), which makes authors less likely to appeal a manuscript decision given these conditions, especially pre-tenure. In all, filing an appeal offers limited recourse.

Overall, there are multiple junctures in the peer-review process at which inequity may arise and go unchecked. There is a critical need to develop peer-review systems in a way that does not place the burden of grappling with inequity on the authors.

Proactive Equity in Peer Review

Journals play a critical role in dissemination of research findings with real-world repercussions for BIPOC communities (e.g., early COVID-19 studies demonstrated the effects of underlying medical conditions partly arising from systemic racism in BIPOC communities; Ogedegbe, 2020). The mission at hand is for journals to help lead dialogue on racism and health (Ogedegbe, 2020), even if the content of research or BIPOC author identities are undervalued by those of the dominant majority (King et al., 2018). If journals fail to take on this role while making public commitments to diversity and antiracism, then they may contribute to inequity in the peer-review process (Williams, 2020), knowledge homogenization arising from editorial bias (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020), and diversity dishonesty (i.e., when an organization publicly states to care about diversity to an extent its actions do not support; Wilton et al., 2020). Such dishonesty will likely exacerbate existing inequities by making BIPOC more concerned about their ability to succeed in the peer-review process (Hoppe et al., 2019; Wilton et al., 2020). Peer-review systems must recognize and mitigate bias for manuscripts involving BIPOC authors or research with BIPOC communities.

Some journals in CSD and the health professions have adopted strategies for equitable peer review, with an aim of countering the systemic biases that can make BIPOC appear as less meritorious (Gosztyla et al., 2021). In this section, we describe actions from individual journals aiming to address equity in peer review, which we urge ASHA journals to consider adopting, and provide a framework for equity in peer review using actual equity in publishing frameworks.

Examples From Individual Journals

-

Diversify and Support Reviewers and Editorial Board Members

Editorial boards can diversify and support diverse reviewers and editorial board members (Taffe & Gilpin, 2021). One component of diversification involves inclusion of individuals from clinical populations. To ensure that research is respectful to autistic individuals, Autism in Adulthood includes at least one autistic reviewer per manuscript (Autism in Adulthood, n.d.; Willingham, 2020). Similarly, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) includes reviewers from the clinical population discussed in manuscripts (The BMJ, 2021). Another component includes proactively recruiting and supporting BIPOC reviewers and editorial board members, which Academic Pediatrics and RRNMF Neuromuscular Journal do (Barohn, 2021; Raphael et al., 2020). One specific way to support new reviewers, which the Journal of Engineering Education does, is by developing mentored reviewing programs to coach new reviewers through the peer-review process with an expert mentor (Jensen et al., 2021). This not only provides a training opportunity for peer review, but also provides a way for early career researchers to get their name in the system for ad hoc reviewer selection and a way for more senior researchers to diversify their professional networks and to learn from junior reviewers who ideally represent the diversity that ought to inform science.

-

Encourage and Support Submissions From Underrepresented Authors

Journals may also support submissions from underrepresented authors (Raphael et al., 2020; Taffe & Gilpin, 2021). Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups' SIG 17: Global Issues in Communication Sciences and Related Disorders explicitly welcomes submissions from BIPOC and international students, who may experience marginalization in CSD (Girolamo & Ghali, 2021). Specifically, SIG 17 holds workshops, such as “Steps to a Successful Manuscript Publication: Resources for Local and International Authors,” to provide resources for manuscript writing, insights on the editorial process for the journal, strategies for improving likelihood of manuscript acceptance, and tips for selecting the right publication for a manuscript (Sanchez, 2021). Another strategy is to encourage such submissions by building it into the mission of the journal. While Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences & Disorders (n.d.-a) includes calls for student submissions in its aims and scope, RRNMF Neuromuscular Journal regularly publishes editorial letters welcoming BIPOC submissions and stating the commitment of the journal to supporting BIPOC early career authors (e.g., Barohn, 2021). Such explicit language promotes a more welcoming, BIPOC-friendly community of authors and peer reviewers, setting a tone of inclusivity.

-

Set Internal Guidelines

A third strategy involves developing and upholding internal guidelines for editorial board member and reviewer behavior (Gerwing et al., 2020; Taffe & Gilpin, 2021). Some journals, such as Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences & Disorders (n.d.-b), explicitly do not tolerate reviewers who do not provide constructive feedback. Others, such as RRNMF Neuromuscular Journal, implemented a similar but implicit approach to reviewing and use peer facilitators rather than reviewers (Barohn, 2021). Peer facilitators perform the same role as peer reviewers but are there to help authors publish quality manuscripts true to the vision of the authors, rather than to gatekeep science. As for editorial decisions, Language Learning and Development shares draft decision letters with the editor-in-chief and action editors; hence, the decision letter passes through peer review before going to the author.

To uphold equity guidelines, journals may establish accountability mechanisms and publicly share that data (Roberts et al., 2020; Silbiger & Stubler, 2019). For example, five Elsevier journals made agreeing to review dependent upon agreement to have their feedback published in aggregate anonymously (i.e., without reviewers' names); this resulted in early career scholars providing more objective recommendations and male reviewers providing more constructive feedback (Bravo et al., 2019). Similarly, BMJ found that, in implementing signed review, review quality did not differ when signed reviews were published versus if the reviews were only available to the authors (van Rooyen et al., 2010). Given that authors may be identifiable in double-blind review (Hill & Provost, 2003), making signed reviews publicly available may increase accountability for bias in peer review beyond internal journal procedures.

-

Prioritize BIPOC Content in Material Ways

A fourth strategy calls for centering submissions involving DEI. ASHA journals, JAMA, and Academic Pediatrics have published special issues on diversity, BIPOC communities, and structural racism in health care (Ogedegbe, 2020; Raphael et al., 2020). Similarly, Academic Pediatrics created manuscript types focusing on how race and racism impact children, families, and academic medicine, with a long-term plan to prioritize diversity content (Raphael et al., 2020). Prioritization of BIPOC content also entails humility. For example, the editor-in-chief of the Journal of the Medical Library Association failed to step in when a white editor changed race-related terminology in the manuscript of BIPOC authors and refused to listen to the authors who had primary expertise in the content area; subsequently, the authors withdrew their manuscript and met with the editor-in-chief, who issued a public apology (Akers & Talmage, 2020).

In all, these actions from individual journals are ones that may contribute to equity in peer review. These steps are ones that individuals, particularly those in positions of power within the editorial process, can act upon in the present, while advocating for more systemic change.

A Framework for Equitable Peer Review

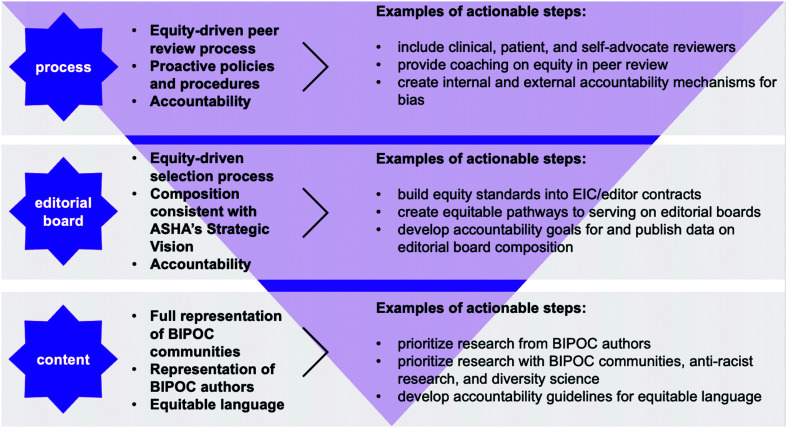

Shaping peer review to be equitable is a systemic endeavor that some associations, such as APA (2021), have addressed through development of work products like the “Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion Toolkit for Journal Editors.” While such an endeavor is undoubtedly a multiyear process (e.g., developing demographic questions for authors and editorial board members around intersecting identities relevant to diversity, such as disability; APA, 2021; Dawson et al., 2020), ASHA journals might begin with processes for equity before segueing into strategies for managing editorial boards and developing priorities for content; see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Framework for developing an equitable peer-review model.

Process

The editorial process sets the stage for editorial board composition and content. Publishing initiatives must develop peer-review policies and procedures from a place of equity, paired with accountability mechanisms (Buchanan et al., 2021b; Resnik & Elmore, 2020; Roberts et al., 2020). There are myriad actions that correspond to achieving process, editorial board, and content goals; see Figure 3. The ASHA Journals Board could support a more inclusive range of editorial board members and Journals Board members, including self-advocates (The BMJ, 2021; Roberts et al., 2020; Willingham, 2020). In tandem, publishing initiatives could provide coaching on equity in the peer-review process to editorial board members (Pollock et al., 2021). In contrast to training, which may be ineffective (Resnik & Elmore, 2016; Taffe & Gilpin, 2021), coaching provides feedback, such that if any editorial board member or ad hoc reviewer fails to meet those standards, there is justification to course correct. To develop accountability mechanisms, journals can implement metrics on how equitable or inequitable reviewers have been in past reviews, develop processes for how they will handle bias in peer review (Buchanan et al., 2021b), and implement an equity ombudsperson who can handle cases if the author believes the editorial office is unjust in their decision-making processes.

Externally, journals can implement diversity rubrics and make that data publicly available (Bravo et al., 2019; Buchanan et al., 2021a, 2021b; Resnik & Elmore, 2016; Roberts et al., 2020; Taffe & Gilpin, 2021). Examples could be journals scoring themselves on criteria pertaining to DEI and antiracism (e.g., whether the editorial board has systems to identify and respond to bias in reviews, how often those systems are used, and what the outcomes are)—and publishing that data (Buchanan et al., 2021a). Finally, journals could publish intersectional data on the demographics of authors who submit to their journals and their outcomes, such as race, ethnicity, or gender (Taffe & Gilpin, 2021). Clearly, this would necessitate collecting data from authors with the aim of understanding whether policies and procedures effect racialized outcomes (Powell, 2012). The aim here is not for journals to collect such data and have individual reviewers be aware of individual author demographics. Rather, the aim is to systematically document underrepresentation, with the ability to course correct if, for example, it becomes evident that there may be inequity (e.g., racialized outcomes).

Editorial Board

With equity-driven processes in place, journals can develop editorial board objectives and actionable steps; see Figure 3. Aims should be to have equity-driven editorial board member selection processes, a composition that aligns to the Strategic Vision of ASHA (n.d.-b), and accountability mechanisms to ensure equity is present throughout the editorial board, from selection to board interactions.

There are many actionable steps to achieve these goals, as seen in Figure 3. In contrast to current ASHA editor and editor-in-chief contracts (ASHA, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c, 2021d), contracts should have standards for equity, such that the expectations for how they should uphold equity are clear. For example, editors-in-chief and editors could be obligated to select editorial board members who recognize the value of publishing BIPOC authors and research with BIPOC communities (Buchanan et al., 2021b) or who will provide an equitable review (Resnik & Elmore, 2016; see Liu et al., 2020, for a suggested five-part reviewer equity competency); for transparency, they could provide a justification for each individual board member that becomes publicly available. In parallel, journals might also have to meet some benchmark of diverse editorial board members, perhaps by creating equitable pathways to serving on editorial boards that lead to leadership pathways as editors or editors-in-chief (Buchanan et al., 2021b; Guy et al., 2020; King et al., 2018). Last, journals could implement a mechanism for authors to provide anonymous ratings of reviews (Buchanan et al., 2021b). This would provide a pathway for authors to voice when reviews are biased; perhaps editorial board members must meet some cutoff score to maintain membership on the editorial board (Buchanan et al., 2021b).

Content

As for content, equity in publishing initiatives should aim for full representation of BIPOC communities and of BIPOC authors (Buchanan et al., 2021b), as well as use of equitable language throughout the editorial process; see Figure 3. First, journals could create and weight criteria for equity in their strategic planning of what to publish (Buchanan et al., 2021b; Linkov et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020). Such a focus could be represented in their mission statement. Second, journals could develop benchmarks for representation in their content and prioritize content where authors justify who is not in their research (e.g., convenience sampling at predominantly white schools may exclude BIPOC students) and state what they are doing to have equitable representation in their research (Roberts et al., 2020; Ruedinger et al., 2021). Third, journals should develop accountability guidelines for language. General guidelines might be using system-centered versus deficit-centered language to describe BIPOC communities (e.g., describing the role of systemic factors in differences among racial and ethnic groups instead of interpreting differences as intrinsic to race or ethnicity) or requiring language in manuscripts and reviews to address participant demographics in an inclusive manner (Buchanan et al., 2021b). Journals might also provide reviewers with examples or tools for checking that their language is not biased (Parsons & Baglini, 2021).

Conclusion

This viewpoint article illustrates how inequity can play out in peer review and offers actionable steps to mitigate bias in the peer-review process. Because of a lack of objective data, we shared real examples within the context of how ASHA journals define the peer-review process. This is an essential first step to starting a conversation around bias in peer review. Some individuals may hope that the experiences shared in this paper may be few in number. However, these examples are just a few of the many that have been shared with or experienced by the authors of this article. Instead, we caution interpretation of a lack of larger-scale, ASHA-level discussion on bias in peer review and a lack of objective, publicly available data as evidence for a lack of bias in peer review. Remember, BIPOC representation in ASHA constituency is well below the BIPOC representation of the U.S. population at large, and systemic racism has silenced many BIPOC voices in the discipline of CSD and the public at large, which together lead to few opportunities for such experiences to brought to light. The authors recognize that sharing these experiences may make some individuals uncomfortable, but until such experiences are openly discussed and addressed, the majority of ASHA constituents, who are of the white majority and who may never experience such bias in the peer review of their work, will never know that such experiences are happening. We urge for data to be publicly available and anticipate that others will continue to explore bias in peer review through collection of objective data.

To uphold our profession's commitment to DEI, equity must be a core value in the journals and in the peer-review process. Overhauling the ways in which scientific communication takes place for equity—creating open review, conducting scientific communication through alternative outlets (e.g., preprint servers and post-publication reviews), and shifting the role of journals from gatekeepers to curators (e.g., a journal might publish a monthly summary of articles from preprint servers; Vazire, 2019b)—may take an indeterminate amount of time to enact. At the same time, we in CSD cannot become complacent about a system that perpetuates inequity and which may contribute to BIPOC underrepresentation among the faculty ranks in the profession. Our hope is that readers will find strategies they may implement or advocate for implementation, as well as critically examine the knowledge base in terms of how inequity shapes the state of the science. An immediate first step might be for those with editorial experience in ASHA journals to publicly reflect upon and share their blind spots and areas for growth, thus shifting the burden for dealing with inequity from relatively powerless authors to the editorial boards in the peer-review process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by T32DC017703 (Directors: Inge-Marie Eigsti and Emily Myers) and T32DC000052 (Director: Mabel Rice). We thank Breanna Krueger (former editorial board member of Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools), Inge-Marie Eigsti (former editorial board member of Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research), Peggy Nelson (former editor-in-chief of the Speech section and current editor-in-chief of the Hearing section of Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research–Speech), Audra Sterling (associate editor of American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology), Mike Cannon (ASHA Senior Director, Serial Publications and Editorial Services), Holly L. Storkel (former editor-in-chief of Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools), Rick Barohn, and Steve Politzer-Ahles for their discussion and feedback. We also thank Vicki Deal-Williams and Melanie Johnson for bringing many of the authors together in the Minority Student Leadership Program.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by T32DC017703 (Directors: Inge-Marie Eigsti and Emily Myers) and T32DC000052 (Director: Mabel Rice).

References

- Abdelaziz, M. M. , Matthews, J. J. , Campos, I. , Kasambira Fannin, D. , Rivera Perez, J. F. , Wilhite, M. , & Williams, R. M. (2021). Student stories: Microaggressions in communication sciences and disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(5), 1990–2002. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_AJSLP-21-00030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers, K. , & Talmage, S. (2020, December 16). An apology from JMLA. Journal of the Medical Library Association. https://jmla.mlanet.org/ojs/jmla/announcement/view/7 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Equity, diversity, and inclusion toolkit for journal editors. https://www.apa.org/pubs/authors/equity-diversity-inclusion-toolkit

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2016). Code of Ethics. https://www.asha.org/code-of-ethics/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2019). Report of the 2013-2018 Academic Affairs Board (AAB) Strategic Plan to Increase the Student Pipeline and Workforce for PhD Researchers and Faculty Researchers. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/reports/academic-affairs-board-report-of-phd-shortage-plan-2013-2018.pdf

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2021a). ASHA Journals editor letter of agreement. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2021b). ASHA Journals editor-in-chief letter of agreement. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2021c). ASHA Journals—Perspectives editor letter of agreement. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2021d). ASHA journals—Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups editor-in-chief letter of agreement. [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2021e). Profile of ASHA members and affiliates, year-end 2020. https://www.asha.org/siteassets/surveys/2011-2020-member-and-affiliate-profiles.pdf

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2021f). Profile of ASHA members and affiliates with PhDs, year-end 2020. https://www.asha.org/research/memberdata/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.-a). Addressing systemic racism and institutional inequities in CSD. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://www.asha.org/about/diversity-equity-inclusion/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.-b). ASHA's envisioned future: 2025. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://www.asha.org/about/ashas-envisioned-future/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.-c). Resources for authors. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://pubs.asha.org/journals/for_authors

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.-d). Guidelines for reporting your research. ASHA Journals Academy. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://academy.pubs.asha.org/asha-journals-author-resource-center/manuscript-preparation/guidelines-for-reporting-your-research/ [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.-e). Journals Board. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://www.asha.org/about/governance/committees/committees/journals-board/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.-f). Journal Editorial Board roles. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://academy.pubs.asha.org/prep-the-asha-journals-peer-review-excellence-program/opportunities-to-get-involved-with-the-asha-journals/journal-editorial-board-roles/

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.-g). Peer review policies. ASHA Journals Academy. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://academy.pubs.asha.org/prep-the-asha-journals-peer-review-excellence-program/peer-review-policies/ [Google Scholar]

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (n.d.-h). What to expect in peer review. ASHA Journals Academy. Retrieved August 20, 2021, from https://academy.pubs.asha.org/asha-journals-author-resource-center/what-to-expect-in-peer-review/ [Google Scholar]

- Annamma, S. A. , Connor, D. , & Ferri, B. (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at the intersections of race and dis/ability. Race Ethnicity and Education, 16(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2012.730511 [Google Scholar]

- Autism in Adulthood. (n.d.). Information for authors. https://home.liebertpub.com/publications/autism-in-adulthood/646/for-authors

- Barohn, R. J. (2021). Letter from the founding facilitator, v.2:2. RRNMF Neuromuscular Journal, (2, 2), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.17161/rrnmf.v2i2 [Google Scholar]

- Barrière, I. , Kresh, S. , Aharodnik, K. , Legendre, G. , & Nazzi, T. (2019). The comprehension of 3rd person singular -s by NYC English-speaking preschoolers. In Ionin T. & Rispoli M. (Eds.), Three streams of generative language acquisition research: Selected papers from the 7th Meeting of Generative Approaches to Language Acquisition–North America, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (Vol. 63, pp. 7–34). John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/lald.63.01ion [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, G. R. , Churchill, S. M. , Mahendran, M. , Walwyn, C. , Lizotte, D. , & Villa-Rueda, A. A. (2021). Intersectionality in quantitative research: A systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM - Population Health, 14, Article 100798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The BMJ. (2021). Guidance for BMJ patient and public reviewers. https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-reviewers/guidance-patient-reviewers

- Bottema-Beutel, K. , Kapp, S. K. , Lester, J. N. , Sasson, N. J. , & Hand, B. N. (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, G. , Grimaldo, F. , López-Iñesta, E. , Mehmani, B. , & Squazzoni, F. (2019). The effect of publishing peer review reports on referee behavior in five scholarly journals. Nature Communications, 10, Article 322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-08250-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, N. T. , Perez, M. , Prinstein, M. J. , & Thurston, I. (2021a). Diversity Accountability Index for Journals (DAI-J): Increasing awareness and establishing accountability across psychology journals. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3pkb5

- Buchanan, N. T. , Perez, M. , Prinstein, M. J. , & Thurston, I. B. (2021b). Upending racism in psychological science: Strategies to change how science is conducted, reported, reviewed, and disseminated. The American Psychologist, 76(7), 1097–1112. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan, N. T. , & Wiklund, L. O. (2020). Why clinical science must change or die: Integrating intersectionality and social justice. Women & Therapy, 43(3–4), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2020.1729470 [Google Scholar]

- Council of Academic Programs in Communication Sciences and Disorders & American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2020). Communication Sciences and Disorders (CSD) Education Survey: National aggregate data report 2019-2020 academic year. https://www.asha.org/academic/hes/csd-education-survey-data-reports/

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039 [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, J. , Coggins, N. L. , Dolechek, M. , & Fosado, G. (2020). Toolkits for equity: An antiracist framework for scholarly publishing. Serials Review, 46(3), 170–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00987913.2020.1806653 [Google Scholar]

- Dondio, P. , Casnici, N. , Grimaldo, F. , Gilbert, N. , & Squazzoni, F. (2019). The “invisible hand” of peer review: The implications of author-referee networks on peer review in a scholarly journal. Journal of Informetrics, 13(2), 708–716. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2019.03.018 [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, R. , Crow, H. , & Gaddy, C. (2020, October 1). Putting autistic voices at the forefront of care. The ASHA LeaderLive. https://leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/leader.FMP.25102020.8/full/ [Google Scholar]

- Dupree, C. H. , & Kraus, M. W. (2020). Psychological science is not race neutral. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 17(1), 270–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620979820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erves, J. C. , Mayo-Gamble, T. L. , Malin-Fair, A. , Boyer, A. , Joosten, Y. , Vaughn, Y. C. , Sherden, L. , Luther, P. , Miller, S. , & Wilkins, C. H. (2017). Needs, priorities, and recommendations for engaging underrepresented populations in clinical research: A community perspective. Journal of Community Health, 42(3), 472–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0279-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerwing, T. G. , Gerwing, A. M. A. , Avery-Gomm, S. , Choi, C. Y. , Clements, J. C. , & Rash, J. (2020). Quantifying professionalism in peer review. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 5(1), Article 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-020-00096-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginther, D. K. , Basner, J. , Jensen, U. , Schnell, J. , Kington, R. , & Schaffer, W. T. (2018). Publications as predictors of racial and ethnic differences in NIH research awards. PLOS ONE, 13(11), Article e0205929. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girolamo, T. , & Ghali, S. (2021). Developing, implementing, and learning from a student-led initiative to support minority students in communication sciences and disorders. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 6(4), 768–777. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_PERSP-20-00299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giwa Onaiwu, M. (2020). “They don't know, don't show, or don't care”: Autism's white privilege problem. Autism in Adulthood, 2(4), 270–272. https://doi.org/10.1089/aut.2020.0077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosztyla, M. L. , Kwong, L. , Murray, N. A. , Williams, C. E. , Behnke, N. , Curry, P. , Corbett, K. D. , Dsouza, K. N. , de Pablo, J. G. , Gicobi, J. , Javidnia, M. , Lotay, N. , Prescott, S. M. , Quinn, J. P. , Rivera, Z. M. G. , Smith, M. A. , Tang, K. T. Y. , Venkat, A. , & Yamoah, M. A. (2021). Responses to 10 common criticisms of anti-racism action in STEMM. PLoS Computational Biology, 17(7), Article e1009141. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1009141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy, M. C. , Afifi, R. A. , Eissenberg, T. , & Fagan, P. (2020). Greater representation of African-American/Black scientists in the NIH review process will improve adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(5), 631–632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, B. V. , Chen, H. , Edwards, M. A. , Faber, L. , & Freischlag, J. A. (2021). A new look at an old problem: Improving diversity, equity, and inclusion in scientific research. The American Surgeon, 87(11), 1722–1726. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031348211029853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, S. , & Provost, F. (2003). The myth of the double-blind review? Author identification using only citations. Acm Sigkdd Explorations Newsletter, 5(2), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1145/980972.981001 [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, A. (2014). A chosen exile: A history of racial passing in American life. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe, T. A. , Litovitz, A. , Willis, K. A. , Meseroll, R. A. , Perkins, M. J. , Hutchins, B. I. , Davis, F. , Lauer, M. S. , Valantine, H. A. , Anderson, J. M. , & Santangelo, G. M. (2019). Topic choice contributes to the lower rate of NIH awards to African-American/Black scientists. Science Advances, 5(10), Article eaaw7238. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw7238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K. , Direito, I. , Polmear, M. , Hattingh, T. , & Klassen, M. (2021). Peer review as developmental: Exploring the ripple effects of the JEE Mentored Reviewer Program. Journal of Engineering Education, 110(1), 15–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20376 [Google Scholar]

- King, E. B. , Avery, D. R. , Hebl, M. R. , & Cortina, J. M. (2018). Systematic subjectivity: How subtle biases infect the scholarship review process. Journal of Management, 44(3), 843–853. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317743553 [Google Scholar]

- Linkov, V. , O'Doherty, K. , Choi, E. , & Han, G. (2021). Linguistic Diversity Index: A scientometric measure to enhance the relevance of small and minority group languages. SAGE Open, 11(2), 21582440211009191. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211009191 [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S. N. C. , Bergman, M. E. , & Hernandez, T. R. (2020). Recommendation: Add a competency on diversity and inclusion. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 13(1), 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2020.21 [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn, T. (2014, July 28). Remetaphoring the “academic pipeline.” Small Pond Science. https://smallpondscience.com/2014/07/28/remetaphoring-the-academic-pipeline/ [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A. , Núñez, G. , & Tyson, C. E. (2021). Faculty of color in communication sciences and disorders: An overdue conversation. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 6(4), 778–782. https://doi.org/10.1044/2021_PERSP-20-00176 [Google Scholar]

- Oetting, J. B. , Rivière, A. M. , Berry, J. R. , Gregory, K. D. , Villa, T. M. , & McDonald, J. (2021). Marking of tense and agreement in language samples by children with and without specific language impairment in African American English and Southern White English: Evaluation of scoring approaches and cut scores across structures. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(2), 491–509. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_JSLHR-20-00243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogedegbe, G. (2020). Responsibility of medical journals in addressing racism in health care. JAMA Network Open, 3(8), e2016531. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, C. E. , & Baglini, R. B. (2021). Peer review: the case for neutral language. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25(8), 639–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaut, V. C. (2010). Diversity science: Why and how difference makes a difference. Psychological Inquiry, 21(2), 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478401003676501 [Google Scholar]

- Politzer-Ahles, S. , Girolamo, T. , & Ghali, S. (2020). Preliminary evidence of linguistic bias in academic reviewing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 47, Article 100895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2020.100895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock, S. , Rhode, S. K. , Harris, S. J. , McAdoo, T. , & Wang, J. (2021, December 2). Community reflections: Takeaways from the diversity sessions at SSP's 43rd Annual Meeting, Part 4. Scholarly Kitchen. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2021/12/02/community-reflections-takeaways-from-the-diversity-sessions-at-ssps-43rd-annual-meeting-part-4/ [Google Scholar]

- Powell, J. A. (2012). Racing to justice: Transforming our conceptions of self and other to build an inclusive society. Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Randall, K. (2021, April 5). From an autistic SLP: How neurotypical colleagues can help. The ASHA LeaderLive. https://leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/leader.FT1.26042021.38/full/ [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, J. L. , Bloom, S. R. , Chung, P. J. , Guevara, J. P. , Jacobson, R. M. , Kind, T. , Klein, M. , Li, S.-T. T. , McCormick, M. C. , Pitt, M. B. , Poehling, K. A. , Trost, M. , Sheldrick, R. C. , Young, P. C. , & Szilagyi, P. G. (2020). Racial justice and academic pediatrics: A call for editorial action and our plan to move forward. Academic Pediatrics, 20(8), 1041–1043. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2020.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, D. B. , & Elmore, S. A. (2016). Ensuring the quality, fairness, and integrity of journal peer review: A possible role of editors. Science and Engineering Ethics, 22(1), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-015-9625-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnik, D. B. , & Smith, E. M. (2020). Bias and groupthink in science’s peer-review system. In Allen D. & Howell J. (Eds.), Groupthink in science (pp. 99–113). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36822-7_9 [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. O. , Bareket-Shavit, C. , Dollins, F. A. , Goldie, P. D. , & Mortenson, E. (2020). Racial inequality in psychological research: Trends of the past and recommendations for the future. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(6), 1295–1309. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620927709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, S. O. , & Rizzo, M. T. (2021). The psychology of American racism. American Psychologist, 76(3), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogus-Pulia, N. , Humbert, I. , Kolehmainen, C. , & Carnes, M. (2018). How gender stereotypes may limit female faculty advancement in communication sciences and disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(4), 1598–1611. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruedinger, E. , Evans, Y. N. , & Balasubramaniam, V. (2021). Abolishing racism and other forms of oppression in scholarly communication. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(1), 10–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez, D. (2021, August 1). Re: SIG 17: Join us at our Live Discussion with PDHs [Discussion post]. ASHA Community SIG 17, Global Issues in Communication Sciences and Related Disorders . https://community.asha.org/home [Google Scholar]

- Silbiger, N. J. , & Stubler, A. D. (2019). Unprofessional peer reviews disproportionately harm underrepresented groups in STEM. PeerJ, 7, Article e8247. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.8247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. (2006). Peer review: A flawed process at the heart of science and journals. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 99(4), 178–182. https://doi.org/10.1258/jrsm.99.4.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taffe, M. A. , & Gilpin, N. W. (2021). Equity, diversity and inclusion: Racial inequity in grant funding from the US National Institutes of Health. eLife, 10, Article e65697. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.65697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences & Disorders. (n.d.-a). Aims & scope. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/tlcsd/aimsandscope.html

- Teaching and Learning in Communication Sciences & Disorders. (n.d.-b). Policies. Retrieved October 1, 2021, from https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/tlcsd/policies.html

- Tennant, J. P. , & Ross-Hellauer, T. (2020). The limitations to our understanding of peer review. Research Integrity and Peer Review, 5(1), Article 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-020-00092-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, A. , Zhang, M. , & Heavlin, W. D. (2017). Reviewer bias in single-versus double-blind peer review. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(48), 12708–12713. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1707323114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). QuickFacts: United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- Valantine, H. A. , & Collins, F. S. (2015). National Institutes of Health addresses the science of diversity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(40), 12240–12242. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1515612112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooyen, S. , Delamothe, T. , & Evans, S. J. (2010). Effect on peer review of telling reviewers that their signed reviews might be posted on the web: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ, 341, Article c5729. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazire, S. (2019a, July). Flip yourself – Part I. Sometimes I'm wrong. https://sometimesimwrong.typepad.com/wrong/2019/07/flip-part-i.html

- Vazire, S. (2019b, July). Flip yourself – Part II. Sometimes I'm wrong. https://sometimesimwrong.typepad.com/wrong/2019/07/flip-part-ii.html

- Walker, R. , Barros, B. , Conejo, R. , Neumann, K. , & Telefont, M. (2015). Personal attributes of authors and reviewers, social bias and the outcomes of peer review: A case study. F1000Research, 4, Article 21. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.6012.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler, D. , Kington, R. , Madans, J. , Van Wye, G. , Christ-Schmidt, H. , Pratt, L. A. , Brawley, O. W. , Gross, C. P. , & Emanuel, E. (2005). Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Medicine, 3(2), Article e19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilbur, K. , Snyder, C. , Essary, A. C. , Reddy, S. , Will, K. K. , & Saxon, M. (2020). Developing workforce diversity in the health professions: A social justice perspective. Health Professions Education, 6(2), 222–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hpe.2020.01.002 [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. T. (2020). Microaggressions: Clarification, evidence, and impact. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619827499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willingham, E. (2020). Autistic people take the helm of studies. Science, 368(6490), Article 460. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.368.6490.460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis, M. , Bridges, A. J. , & Jozkowski, K. N. (2021). Gender and racial/ethnic disparities in rates of publishing and inclusion in scientific-review processes. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 7(4), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000253 [Google Scholar]

- Wilton, L. S. , Bell, A. N. , Vahradyan, M. , & Kaiser, C. R. (2020). Show don't tell: Diversity dishonesty harms racial/ethnic minorities at work. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(8), 1171–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167219897149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]