Context:

In response to the drug overdose crisis, first responders, in partnership with public health, provide new pathways to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and other services for individuals they encounter in their day-to-day work.

Objective:

This scoping review synthesizes available evidence on first responder programs that take an assertive approach to making linkages to care.

Results:

Seven databases were searched for studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals between January 2000 and December 2019. Additional articles were identified through reference-checking and subject matter experts. Studies were selected for inclusion if they sufficiently described interventions that (1) focus on adults who use drugs; (2) are in the United States; (3) involve police, fire, or emergency medical services; and (4) assertively link individuals to SUD treatment. Twenty-two studies met inclusion criteria and described 34 unique programs, implementation barriers and facilitators, assertive linkage strategies, and linkage outcomes, including unintended consequences.

Conclusions:

Findings highlight the range of linkage strategies concurrently implemented and areas for improving practice and research, such as the need for more linkages to evidence-based strategies, namely, medications for opioid use disorder, harm reduction, and wraparound services.

Keywords: first responders, linkage to care, overdose, substance use, treatment

As drug overdose deaths rose dramatically in the United States in the past 2 decades, surpassing 100 000 deaths in 2021,1 many first responder agencies, namely, police, fire, and emergency medical services (EMS), responded in novel ways. They increasingly offered linkage to care to individuals encountered during routine work, with most new linkage programs starting around 2018,2 soon after deaths from synthetic opioids increased sharply.3 First responder linkage programs are cross-sector collaborations with public health to create pathways to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment and other services, such as harm-reduction and wraparound services, for people who use drugs. They are distinguished by their emphasis on intervening in the community, outside of institutional settings, such as hospitals, jails, and prisons.

There are advantages to offering linkage from the community. SUD treatment can be difficult to access owing to cost, availability, and motivational barriers.4,5 Hospitals, jails, and prisons facilitate access,6,7 but these entry points can be unreliable or inadvertently harmful. Individuals who use drugs often avoid hospitals, and even if they utilize them, indicated treatments may not be available.8 Arrest alone can jeopardize future employment, education, and other benefits and negatively affect mental health.9 Jail and prison incarceration can further endanger health and future livelihoods, especially for individuals with SUD, who are less likely to receive evidence-based treatments while in custody.10,11 Individuals in custody are also more likely to fatally overdose after release.12 Drug courts, another pathway to treatment, also have limitations.13 First responder linkage programs help reduce treatment access barriers while bypassing these other systems.

Despite their promise, first responder linkage programs are not well understood.14,15 A recent national survey shows that only one in 6 programs conducts formal evaluation.2 One area that warrants attention is how programs optimize linkages through “assertive,” that is, active and persistent,16 means. While use of such strategies has been studied in other contexts,17 little is known about parallel practices involving first responders. Furthermore, questions remain about efficacy and ethics, specifically whether first responders who act assertively improve treatment or service outcomes15,18,19 or cause unintended harm. Possible harms include privacy loss or, in cases of warrant checking, refusal of services or arrest.18–20 To address this knowledge gap, this scoping review (1) identifies studies of first responder programs that make assertive linkages; (2) describes the programs, implementation barriers and facilitators, and assertive linkage strategies employed; and (3) describes findings, if available, on treatment and service connections and unintended consequences. These outcomes can approximate how well assertive linkage strategies are serving their immediate intended purpose.

Methods

We conducted this scoping review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist for Scoping Reviews.21 Scoping reviews are indicated when concepts, such as assertive linkage, are emergent and not clearly or universally defined or when studies, such as those on first responder linkage, are heterogeneous in design, making it difficult to synthesize evidence and answer a specific research question.22 We designed a search strategy, in collaboration with a public health librarian, to identify relevant studies. To be included, studies had to sufficiently describe, in the same or different publication, programs that (1) focus on adults (ie, older than 18 years) who use drugs; (2) are in the United States; (3) involve police, fire, or EMS; and (4) assertively connect individuals to SUD treatment (eg, medications for opioid use disorder [MOUD], cognitive behavioral therapy, detoxification, counseling). We define assertive linkage as more than passive information sharing (ie, providing phone numbers for individuals to call); instead, programs must actively facilitate linkage, for example, by making appointments, arranging transportation, involving case managers, or ensuring follow-through. We limited the search to publications in English in peer-reviewed journals between January 2000 and December 2019.

A public health librarian executed the finalized search strategy in 7 electronic databases: Academic Search Complete, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Criminal Justice Database, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Sociological Abstracts. Additional articles were identified by searching relevant reference lists and consulting subject matter experts. The full electronic search strategy for MEDLINE follows; others are available upon request:

Exp Substance-Related disorders/OR Exp Opioid-Related Disorders/OR ((substance ADJ2 (abuse* OR misuse* OR disorder* OR addict* OR use*)) OR (drug ADJ2 (abuse* OR misuse* OR disorder* OR addict* OR use*)) OR heroin OR opioid* OR opiate* OR morphine OR opium OR painkiller* OR pain-killer* OR (inject* ADJ2 drug*))

AND

(safe ADJ2 station*) OR (safe ADJ2 site*) OR (safe ADJ2 house*) OR (safe ADJ2 space*) OR (safe ADJ2 facilit*) OR (station* ADJ5 link*) OR (station* ADJ5 partner*) OR fire house* OR fire station* OR police station* OR angel program* OR (arrest* AND diver*) OR (arrest* AND deflect*) OR (pre-arrest* AND diver*) OR (pre-book* AND diver*) OR (arrest ADJ5 link*) OR (pre-arrest ADJ5 link*) OR (law enforcement AND diver*) OR (police* AND diver*) OR (Police* ADJ5 link*) OR (law enforcement ADJ5 link*) OR ((Overdos* OR over-dos* OR post-overdose) AND (Outreach* OR out-reach* OR follow-up OR community based)) OR (first responder ADJ3 diver*) OR quick response team*

AND

journal article.pt

Two authors independently reviewed titles and abstracts, followed by full text, to determine eligibility. Two authors then developed a data-charting form in Excel relevant to the study aims, independently extracted data, discussed findings, and resolved discrepancies through consensus. Data on program and study characteristics were extracted. Program characteristics included name; location; program type; year started; population; eligibility; first responder types and roles; assertive linkage strategies; linkage to MOUD, harm reduction, and wraparound services; consequences for opting out; and other components. Program types, listed as follows, were the only data category where codes were developed deductively:

Prebooking: Patrol officers, using discretion, link individuals to treatment and services in lieu of arresting, booking, or taking no action.

Postoverdose: First responders or other providers, working alone or in teams, contact individuals who recently overdosed or their personal networks to offer linkage.

Location-based: Individuals can request linkage without fear of arrest at designated sites, such as fire or police stations or community events.

Hybrid: Elements of the other 3 intervention types are combined.

Study characteristics included design, methods, variables, findings, other findings of relevance, duration, and unintended consequences.

Results

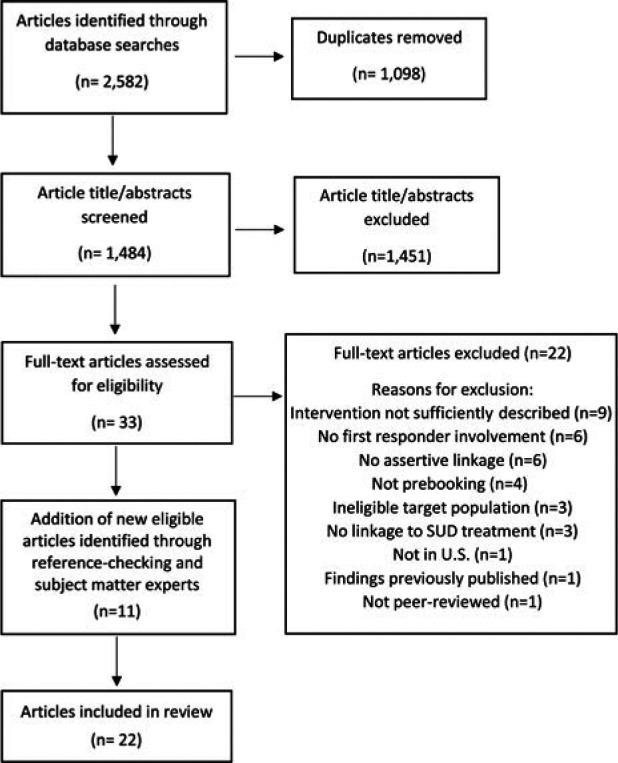

The Figure shows the study selection process, which resulted in 22 studies ultimately included in the review that collectively described 34 unique programs.* Results are organized by program type; implementation barriers and facilitators; assertive linkage strategies; and linkage-relevant findings. A complete record of charted data is available as Supplemental Digital Content Appendices I and II (available at http://links.lww.com/JPHMP/B31 and http://links.lww.com/JPHMP/B32, respectively).

FIGURE.

PRISMA Flow Diagram Showing Study Selection Process

Abbreviation: SUD, substance use disorder.

Program types

Thirteen studies23–35 described 7 prebooking programs or programs with prebooking elements. Populations of focus included individuals involved in low-level23–31 or repeat32 offenses or with severe mental illness.32–34 Three programs23,25–30 had eligibility criteria, which police could override.23 In one program,29 eligibility included victim approval. Police, the only involved first responders in this program type, had multiple roles: identifying individuals,23,24,32–35 determining program eligibility,23–30 transferring case information to a service provider,28 and providing transportion.33

Five studies36–40 described 23 postoverdose programs focused on individuals who recently overdosed or their personal networks. Two programs, for evaluation purposes, had eligibility criteria, including treatment readiness.36,38 Police, fire, or EMS supported this program type by promoting it at overdose scenes,39,40 sharing contact information,36–40 conducting in-person outreach,36,37,39 and staffing locations where individuals could request linkage.39 Of the 21 programs that conducted outreach, 4 involved only police in outreach and 9 involved multidisciplinary teams.36,37,39 Eight programs did not involve first responders in outreach.38,39,40

Three studies19,41,42 described 3 unique location-based programs. Although similar to postoverdose programs that offer drop-in services, these programs focused on individuals with SUD regardless of overdose history. One program19 excluded individuals with active warrants or acute medical or safety concerns but assisted with clearing warrants, if possible. One program41 involved fire, police, and EMS, and 2 programs19,42 involved only police. In 2 programs,19,41 first responders assisted throughout the linkage process. In the third,42 which hosted community events where individuals could request linkage, police staffed and publicized the events.

One study43 described a hybrid program focused on individuals with SUD. No eligibility requirements were specified. Police, the only involved first responders were responsible for referring individuals for linkage and accompanying a care coordinator during in-person outreach.

Implementation barriers and facilitators

Barriers to prebooking programs23,31 included limited police buy-in and willingness to offer linkage to all eligible individuals. Barriers to postoverdose programs36,37,39 included stigma; challenges associated with data sharing, financing, sustainability, replicability, outreach to homes if individuals are not home or illegal activity is occurring; and, once again, limited police buy-in. Location-based programs19,41 were hindered by negative police attitudes toward returning or ineligible individuals (eg, due to active warrants), few linkages to sustained treatment, and attrition. A final, crosscutting barrier involved shortages in treatment19,36 and service23 options.

Facilitators to postoverdose programs38,39 and the single hybrid program,43 an assemblage of the other program types, included police investment, community partnerships, proactive outreach, and persistent follow-up, even after initial linkage. Facilitators to location-based programs included peer involvement,42 naloxone distribution,42 extended operating hours,19 police chief leadership,19 and a nonjudgmental approach.19 No facilitators were identified for prebooking programs.

Assertive linkage strategies

The 34 programs demonstrated use of 9 assertive linkage strategies (Box) categorized as 2 types: engagement strategies and treatment and service connection strategies. Each program used more than 1 strategy concurrently.

BOX. Assertive Linkage Strategies to Link People With Substance Use Disorders to Care.

| Strategy Type | Assertive Linkage Strategy | Description | Programs Utilizing Strategy by Type | Studies Describing Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engagement | Proactive outreach | Data or police referrals are used to identify and contact individuals by phone or in person | Prebooking (n = 2)Postoverdose (n = 21) | 23,35–40,42,43 |

| Location-based (n = 1) | ||||

| Hybrid (n = 1) | ||||

| On-site providers | Providers are present at designated places for drop-in linkage requests or they rapidly travel to meet individuals identified for linkage by police | Prebooking (n = 1) | 19,23,39,41,42 | |

| Location-based (n = 4) | ||||

| Secure transport | Individuals are transported to designated places where providers can engage them directly | Prebooking (n = 3) Postoverdose (n = 1) |

32–34,38 | |

| Treatment/service connection | Case management | Providers help individuals access various types of care | Prebooking (n = 5) | 23–27,31,32,35,39–43 |

| Postoverdose (n = 2) | ||||

| Location-based (n = 2) | ||||

| Hybrid (n = 1) | ||||

| Patient navigation | Providers help individuals access SUD treatment | Postoverdose (n = 2) | 19,36–48 | |

| Location-based (n = 1) | ||||

| Peer support | Peer support or recovery specialists are deployed to enhance service connections | Postoverdose (n = 1) | 36,37,41,42 | |

| Location-based (n = 2) | ||||

| Motivational interviewing | Providers inspire treatment readiness and address motivational barriers | Prebooking (n = 2) | 23,36–38,42 | |

| Postoverdose (n = 2) | ||||

| Location-based (n = 1) | ||||

| Low-threshold access | Efforts are made to increase ease of access for individuals and providers | Prebooking (n = 4) | 28–30,33,34,36,37,41,43 | |

| Postoverdose (n = 1) | ||||

| Hybrid (n = 1) | ||||

| External pressure | Efforts are made to encourage or force treatment or service connections | Prebooking (n = 4) | 23–31,33,34,38 | |

| Postoverdose (n = 5-7) | ||||

| Location-based (n = 1) |

Abbreviation: SUD, substance use disorder.

Engagement strategies focused on contacting individuals to publicize a linkage program, conduct screenings or assessments, motivate individuals toward treatment, or start recovery plans. The first engagement strategy, proactive outreach,23,35–40,42,43 used police or EMS records,36,37,43 referrals,23,35,38,40 or other sources42 to identify individuals and then contact them by phone38,40,42 or physically locate them at home or in the community.23,36–39,43 In one program,38 phone contact was only made with prior consent. In some programs,39 outreach was directed toward not individuals but sites where overdoses occurred. The second strategy, on-site providers,19,23,39,41,42 involved providers being present at designated places to engage self-referring individuals upon arrival19,39,42 or rapidly traveling to individuals identified for linkage by police.23,41 Programs often paired this strategy with positive publicity,19 word of mouth,39 and the distribution of naloxone42 or other items to draw in individuals. A third strategy used secure transport32–34,38 in ambulances, patrol cars, mobile crisis units, or other means to transfer individuals directly to crisis centers32–34 or program offices38 where providers could engage them directly.

Connection strategies focused on actualizing linkages to treatment and services. The first connection strategy was case management, also called care coordination.23–27,31,32,35,39–43 Providers conducted psychosocial assessments,23–25,41 helped individuals establish goals and care plans,23–26,35,41 and provided support and accompaniment as they worked toward goals. The latter involved covering the cost of treatment or services as needed,23–25 continuously checking in,41,43 making handoffs between services,43 and ensuring plan adherence.35 In some programs, treatment and abstinence were not required for participation.23–26,31,39 In others, treatment was expected, and case management, “holistic and wraparound,”43 was designed to support social service and other recovery-oriented needs.35,41,43 In 2 programs,23–26,43 case management was explicitly time-unlimited to honor self-directed goals and coordinate care in the event of possible relapse.

The second connection strategy, patient navigation,19,36–38 differed from case management in its explicit focus on treatment. Providers conducted screenings,19,36–39 helped resolve ambivalence about treatment,36–38 scheduled clinical visits,19,36–38 addressed insurance, childcare, transportation, or other treatment barriers,19,36–38 created appointment reminders,38 and persistently followed up to resolve missed appointments or other issues.36–38 The third strategy, peer support,36,37,41,42 deployed peers to motivate individuals toward treatment,36,37,41,42 lead support groups,36,37 and assist with housing and job placement,36,37,41 leveraging their lived experience as inspiration and support. Often used in conjunction within the preceding 3 strategies was a fourth strategy, motivational interviewing,23,36–38,42 intended to identify and inspire treatment readiness and address barriers.

A fifth connection strategy, low-threshold access, streamlined linkage for individuals28–30,33,34,36,37,41,43 or referring first responders.33,34 Examples of the former included same-day telehealth appointments for buprenorphine within 24 hours, with bridge scripts as needed,36,37 in-house counseling, groups, or detoxification,33,34,36,37 or same-day, fast-tracked, or guaranteed admission.28–30,41,43 One program28–30 guaranteed admission by referring individuals to the same behavioral health provider and forwarding case information in advance, although eligibility requirements and lack of transportation assistance likely made this option higher threshold for some. When directed toward first responders, low-threshold access involved no-refusal policies and 30- to 60-minute intake procedures.33 A final connection strategy, external pressure,23–31,33,34,39 encouraged, even forced, treatment or service connections through involuntary commitment,33,34,39 linking individuals to treatment at the request of third parties,19 or holding individuals responsible, or potentially responsible, for original crimes if they opted out.23–31

Linkage-relevant findings

Of the 34 programs described by studies in this review, 6 programs19,23,35–38,41 reported providing or linking to MOUD, with some mentioning all 3 forms.36–38 Eight programs23–27,31,35–37,41–43 reported providing or linking to wraparound services, including housing, food, vocational, and legal assistance. Three programs39,42,43 reported distributing naloxone.

Linkage to treatment was measured in 9 studies, all but one observational in design. In a postoverdose program study,36 of the 60% of individuals contacted, 33% accepted same-day treatment; after 30 and 90 days, 88% and 56% remained in treatment, respectively. In another study40 of the same program type, of the 66% of individuals linked to treatment either passively or assertively following a naloxone reversal, 33% made at least one visit. The only experimental study,38 also of a postoverdose program, reported that, of the 80% of individuals contacted, 81% were linked to MOUD compared with 18% of controls.

The hybrid program study43 reported contacting 70% of individuals. Linkage to treatment was measured for all individuals regardless of how they entered the program: 77% completed detoxification and 76% accepted next level care. A location-based program19 had the highest linkage rate at 86%. Most individuals (80%) were linked to short-term detoxification, with many (68%) reporting additional placement by the detoxification facility.

The remaining 4 studies with treatment outcomes focused on prebooking programs. Three studies28–30 measured completion of a 90-day behavioral health program, with the most recent30 showing that 91% of individuals completed intake and 84%, the program. Relatively few (2%), however, screened positive for substance use; furthermore, those who did were twice as likely to leave early.29 A final study,34 using a nonequivalent control, found that, 1 year after linkage, individuals were significantly more likely to report counseling and medication compliance.

Only one study24 of a prebooking program measured linkage to services using a single-arm, within-subjects design. Compared with baseline, 18 months following linkage, individuals were more than twice as likely to be sheltered, 89% more likely to be housed, 46% more likely to be on the employment continuum, and 33% more likely to have received income/benefits.

Unintended consequences were described in 2 studies. One study39 cautioned that data sharing for the purposes of unsolicited outreach could lead to “eviction, stigma, social control, or other adverse consequences,” such as future reluctance to call 911, and that use of involuntary commitment could exacerbate this mistrust. Another study19 reported instances of coerced treatment by family members and outside agencies, arrests of individuals with active warrants, discrimination toward individuals who relapsed or were ineligible for linkage, and reluctance to link individuals to evidence-based treatments, such as MOUD.

Discussion and Conclusion

Results from this scoping review suggest that first responder assertive linkage programs, especially prebooking and postoverdose types and programs involving police, are prominent and receiving attention in peer-reviewed literature. The identification of 9 assertive linkage strategies, used concurrently by programs, shows that programs are committed to ensuring swift, unencumbered linkages. That programs use many of the same strategies suggests considerable overlap between them in the assertive linkage strategies they are employing, bringing some conceptual clarity to the concept of assertive linkage. The strategies are also described favorably in studies23,27,36,37 or directly referenced as possibly associated with positive outcomes,19,24,38 which speaks to their potential. Finally, despite reported implementation barriers, studies suggest that programs are feasible with sufficient resources, partnerships, and first responder buy-in and connections, especially to treatment, are occurring. While results of this review are encouraging, they also indicate areas for improvement in practice and research.

First, assertive linkages may be less effective, even counterproductive, when they involve eligibility criteria or result in arrest. Not only does arrest undermine program goals but it potentially introduces new harms associated with criminal justice involvement as well. Second, equally important to how individuals are linked, whether assertively or passively, is where they are linked to. Similar to the findings of other reviews,14 relatively few programs reported linking to evidence-based treatments, such as MOUD, and wraparound services known to enhance treatment44 and recovery.45 In addition, few reported distributing naloxone. Providing access to naloxone, fentanyl test strips, safe injection education, sterile syringes, and other harm-reduction tools is critical, especially for individuals uninterested in treatment.

Third, while many identified assertive linkage strategies, used alone46–50 or in combination,51,52 improve treatment outcomes, others require further evaluation. The effectiveness of proactive outreach, for example, may be limited to community settings53,54 and not extend to personal residences. While 2 studies in this review showed high rates of in-home contact,36,43 with one36 reporting a 33% treatment acceptance rate, not captured was how well others welcomed or benefited from this approach. Also not captured was how individuals perceived outreach conducted by or with police in light of historically punitive and racialized policing practices.55,56 While these are areas for future research, preliminary research shows a preference for outreach by peers.18 Furthermore, as found in this review, gaining consent on-site after an overdose in advance of outreach is feasible38; this may minimize unwanted visits.

Similarly, use of external pressure to facilitate linkage is not strongly supported by evidence.57 This assertive strategy is also at odds with the notion that linkage programs are presumably voluntary. Additional research could explore how linkage under pressure is experienced and how this strategy shapes outcomes.

Fourth, programs are encouraged to employ strategies that align with their populations of focus. For example, while an on-site provider may be less assertive than proactive outreach, it has the ability to reach individuals who are transient and unable to be physically located. Similarly, while case management is highly assertive, peer support or motivational interviewing may be better suited for individuals who face readiness barriers. Furthermore, any assertive linkage strategy that requires treatment or abstinence could alienate individuals who are not treatment-ready but could still benefit from other supports. Some programs23–27,31,39 avoided this by adhering to a harm-reduction approach and allowing individuals to set their own health and wellness goals.

Finally, underscoring the conclusions of others,13,14 the effectiveness of first responder assertive linkage is still largely unknown. Linkage to treatment, the most commonly reported outcome, was not uniformly measured across programs. While it may not be appropriate for all programs to measure this outcome, especially if their goal is harm reduction, not treatment, greater standardization would allow for more cross-site comparisons. Study designs were also less robust. All but one study lacked randomization and comparative controls, introducing possible selection bias and limiting claims of causality. In addition, all studies had small sample sizes. Furthermore, absent from many studies were measures indicating linkages to other services, treatment retention, unintended consequences, and reduction in overdoses. Finally, with few exceptions,19,27,38 program participants were not surveyed or interviewed, or if they were, data were limited by low response rates and possible selection and recall bias.19,38 Future studies could address these shortcomings. They could also measure other linkage to care indicators58 and critically examine untested assumptions built into program designs, such as the more assertive the strategy, the better, and the use of overdose and first responder encounters as ideal instigating events for treatment. Finally, they could focus greater attention on location-based and hybrid programs, programs led by first responders other than police, and the effectiveness of not only the programs but also the linkage strategies employed.

This scoping review has limitations. Because we excluded gray literature, we potentially missed other program types, assertive strategies, and reported outcomes. In addition, we missed studies published after December 2019.59–61 The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on first responder assertive linkage programs are also not captured. Absent, for example, is how COVID-19 may have introduced new barriers and opportunities for service delivery, such as telehealth. Next, given our interest in assertive linkage, we deemphasized and possibly overlooked other important program components and study findings. Furthermore, because of publication bias, unintended consequences of these interventions were likely underreported. Finally, because this scoping review does not critically appraise the evidence, we could not compare outcome data and make definitive conclusions about program or linkage strategy effectiveness.

Nonetheless, this scoping review adds to our understanding of first responder linkage, given its explicit focus on assertive approaches and associated promises and pitfalls. Although linkage to treatment and services can be enhanced through assertive means, individuals can be inadvertently harmed if strategies ultimately lead to coerced treatment, treatment that is not indicated or evidence-based, arrest, discrimination, or the denial of treatment or other services that enhance treatment and prevent overdose.

Implications for Policy & Practice

First responder linkage programs are prominent, indicating that they are contributing to community-based overdose prevention.

Concurrent use of multiple assertive linkage strategies may be best suited to achieving linkage to treatment and services among people who use drugs.

Assertive linkage programs not currently linking to evidence-based strategies, such as MOUD, wraparound services, and harm reduction, may consider making these strategies core components of programming and training providers accordingly.

Programs may critically reassess the role and function of program eligibility criteria that bar participation or result in an unexpected arrest for an active warrant. They may consider lifting such requirements if legally permissible.

Some programs identified implementation barriers beyond their control, such as financing, sustainability, and the availability of adequate and appropriate linkage options, suggesting a need for more state and federal funding opportunities, improved public health infrastructure, and new legislation that support expanded SUD treatment options.

Supplementary Material

*In some cases, multiple studies described the same program. In others, a single study described multiple programs, only some of which qualified as first responder linkage programs, or it described a program that only had some qualifying elements. Unless otherwise stated, only results specific to the qualifying programs or elements are included herein.

The authors thank Joanna Taliano, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Public Health Library and Information Center, for assistance with the literature search, and Ayanna Robinson, for reviewing the manuscript and providing useful feedback.

This research was supported, in part, by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at CDC administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the US Department of Energy and CDC. No funding was provided for this work beyond salary support.

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of CDC.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (http://www.JPHMP.com).

Written work prepared by employees of the Federal Government as part of their official duties is, under the U.S. Copyright Act, a “work of the United States Government” for which copyright protection under Title 17 of the United States Code is not available. As such, copyright does not extend to the contributions of employees of the Federal Government.

Contributor Information

Nancy Worthington, Email: ous8@cdc.gov.

Talayha Gilliam, Email: rte9@cdc.gov, gilliamtalayha@gmail.com.

Sasha Mital, Email: ggu4@cdc.gov.

Sharon Caslin, Email: scaslin@fas.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm. Accessed February 15, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.TASC Center for Health & Justice and Bureau of Justice Assistance. Report of the National Survey to Assess First Responder Deflection Programs in Response to the Opioid Crisis. Washington, DC: Office of Justice Programs; 2021. NCJ No. 300955. [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Donnell J, Gladden R, Seth P. Trends in deaths involving heroin and synthetic opioids excluding methadone, and law enforcement drug product reports, by census region—United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(34):897–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browne T, Priester MA, Clone S, Iachini A, DeHart D, Hock R. Barriers and facilitators to substance use treatment in the rural south: a qualitative study. J Rural Health. 2016;32(1):92–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Priester MA, Browne T, Iachini A, Clone S, DeHart D, Seay KD. Treatment access barriers and disparities among individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: an integrative literature review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;61:47–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Cloud DH, Davis C, et al. Addressing excess risk of overdose among recently incarcerated people in the USA: harm reduction interventions in correctional settings. Int J Prison Health. 2017;13(1):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon MV, et al. Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vilke GM, Sloane C, Smith AM, Chan TC. Assessment for deaths in out-of-hospital heroin overdose patients treated with naloxone who refuse transport. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(8):893–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandes AD. How far up the river? Criminal justice contact and health outcomes. Soc Curr. 2020;7(1):29–45. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunn A, Zaller N, Dickman S, Trimbur C, Nijhawan A, Rich JD. Methadone and buprenorphine prescribing and referral practices in US prison systems: results from a nationwide survey. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(1/2):83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pew Research Center. This state has figured out how to treat drug-addicted inmates. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/02/26/this-state-has-figured-out-how-to-treat-drug-addicted-inmates. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- 12.Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, et al. Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: a qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7(1):3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Csete J. Criminal justice barriers to treatment of opioid use disorders in the United States: the need for public health advocacy. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(3):419–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagley SM, Schoenberger SF, Waye KM, Walley AY. A scoping review of post opioid-overdose interventions. Prev Med. 2019;128:105813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yatsco AJ, Champagne-Langabeer T, Holder TF, Stotts AL, Langabeer JR. Developing interagency collaboration to address the opioid epidemic: a scoping review of joint criminal justice and healthcare initiatives. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;83:102849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roeg DPK, Van De Goor IAM, Garretsen HFL. European approach to assertive outreach for substance users: assessment of program components. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42(11):1705–1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bajis S, Dore GJ, Hajarizadeh B, Cunningham EB, Maher L, Grebely J. Interventions to enhance testing, linkage to care and treatment uptake for hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;47:34–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagner KD, Harding RW, Kelley R, et al. Post-overdose interventions triggered by calling 911: centering the perspectives of people who use drugs (PWUDs). PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0223823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiff DM, Drainoni ML, Weinstein ZM, Chan L, Bair-Merritt M, Rosenbloom D. A police-led addiction treatment referral program in Gloucester, MA: implementation and participants' experiences. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2017;82:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tori ME, Cummins E, Beletsky L, et al. Warrant checking practices by post-overdose outreach programs in Massachusetts: a mixed-methods study. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;100:103483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckett K. The uses and abuses of police discretion: toward harm reduction policing. Harv Law Policy Rev. 2016;10:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clifasefi SL, Lonczak HS, Collins SE. Seattle's Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program: within-subjects changes on housing, employment, and income/benefits outcomes and associations with recidivism. Crime Delinquency. 2017;63(4):429–445. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins SE, Lonczak HS, Clifasefi SL. Seattle's Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD): program effects on recidivism outcomes. Eval Program Plann. 2017;64:49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Collins SE, Lonczak HS, Clifasefi SL. Seattle's law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD): program effects on criminal justice and legal system utilization and costs. J Exp Criminol. 2019;(15):201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morrissey S, Nyrop K, Lee T. Landscapes of loss and recovery: the anthropology of police-community relations and harm reduction. Hum Organ. 2019;78(1):28–42. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kopak AM, Cowar J, Frost G, Ballard A. The Adult Civil Citation Network: an innovative pre-charge diversion program for misdemeanor offenders. J Community Corrections. 2015;25(1):5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kopak AM, Frost GA. Correlates of program success and recidivism among participants in an adult pre-arrest diversion program. Am J Criminal Justice. 2017;42(4):727–745. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopak AM. An initial assessment of Leon County Florida's Pre-Arrest Adult Civil Citation Program. J Behav Health Ser Res. 2019;46(1):177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worden RE, McLean SJ. Discretion and diversion in Albany's Lead Program. Criminal Justice Policy Rev. 2018;29(6/7):584–610. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lattimore PK, Broner N, Sherman R, Frisman L, Shafer MS. A comparison of prebooking and postbooking diversion programs for mentally ill substance-using individuals with justice involvement. J Contemp Criminal Justice. 2003;19(1):30–64. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steadman HJ, Stainbrook KA, Griffin P, Draine J, Dupont R, Horey C. A specialized crisis response site as a core element of police-based diversion programs. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(2):219–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steadman HJ, Naples M. Assessing the effectiveness of jail diversion programs for persons with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. Behav Sci Law. 2005;23(2):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Au-Yeung C, Blewett LA, Lange K. Addressing the rural opioid addiction and overdose crisis through cross-sector collaboration: Little Falls, Minnesota. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(2):260–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langabeer J, Champagne-Langabeer T, Luber SD, et al. Outreach to people who survive opioid overdose: linkage and retention in treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;111:11–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Langabeer JR, Persse D, Yatsco A, O'Neal MM, Champagne-Langabeer T. A framework for EMS outreach for drug overdose survivors: a case report of the Houston Emergency Opioid Engagement System. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2020;25(3):441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scott CK, Dennis ML, Grella CE, et al. Findings from the Recovery Initiation and Management after Overdose (RIMO) pilot study experiment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;108:65–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Formica SW, Apsler R, Wilkins L, Ruiz S, Reilly B, Walley AY. Post opioid overdose outreach by public health and public safety agencies: exploration of emerging programs in Massachusetts. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;54:43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner KD, Bovet LJ, Haynes B, Joshua A, Davidson PJ. Training law enforcement to respond to opioid overdose with naloxone: impact on knowledge, attitudes, and interactions with community members. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;165:22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sacco P, Unick GJ, Gray C. Enhancing treatment access through “safe stations.” J Soc Work Pract Addict. 2018;18(4):458–464. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huber MJ, Umphrey J, Surico E, Lepore-Jentleson J, Johns B. Conversations for change: grassroots effort to reduce overdose and deaths related to opioids. J Drug Alcohol Res. 2019;8:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Streisel S, Visher C, O'Connell DJ, Martin SS. Using law enforcement to improve treatment initiation and recovery. Probation J. 2019;83(2):39–83. [Google Scholar]

- 44.NIDA. Principles of effective treatment. National Institute on Drug Abuse Web site. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/principles-drug-addiction-treatment-research-based-guide-third-edition/principles-effective-treatment. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- 45.Cloud W, Granfield R. Conceptualizing recovery capital: expansion of a theoretical construct. Subst Use Misuse. 2008;43(12/13):1971–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanderplasschen W, Rapp RC, De Maeyer J, Van Den Noortgate W. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of case management for substance use disorders: a recovery perspective. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Penzenstadler L, Machado A, Thorens G, Zullino D, Khazaal Y. Effect of case management interventions for patients with substance use disorders: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2017;8:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bassuk EL, Hanson J, Greene RN, Richard M, Laudet A. Peer-delivered recovery support services for addictions in the United States: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2016;63:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunn C, Deroo L, Rivara FP. The use of brief interventions adapted from motivational interviewing across behavioral domains: a systematic review. Addiction. 2001;96(12):1725–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carter J, Zevin B, Lum PJ. Low barrier buprenorphine treatment for persons experiencing homelessness and injecting heroin in San Francisco. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2019;14(1):20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.D'Onofrio G, Degutis LC. Integrating Project ASSERT: a screening, intervention, and referral to treatment program for unhealthy alcohol and drug use into an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(8):903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Scott CK, Dennis ML. Results from two randomized clinical trials evaluating the impact of quarterly recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users. Addiction. 2009;104(6):959–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fisk D, Rakfeldt J, McCormack E. Assertive outreach: an effective strategy for engaging homeless persons with substance use disorders into treatment. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32(3):479–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scott CK, Dennis ML, Grella CE, et al. A community outreach intervention to link individuals with opioid use disorders to medication-assisted treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;108:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Friedman J, Syvertsen JL, Bourgois P, Bui A, Beletsky L, Pollini R. Intersectional structural vulnerability to abusive policing among people who inject drugs: a mixed methods assessment in California's central valley. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;87:102981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunins HV. Structural racism and the opioid overdose epidemic: the need for antiracist public health practice. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2020;26(3):201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Messinger JC, Ikeda DJ, Sarpatwari A. Civil commitment for opioid misuse: do short-term benefits outweigh long-term harms? J Med Ethics. May 27, 2021. doi:10.1136/medethics-2020-107160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cruz K, Chiang S. Evaluation profile for linkage to care initiatives. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/od2a/pdf/OD2A_EvalProfile_LinkageToCareInitiatives_508.pdf. Accessed February 15, 2022.

- 59.Yatsco AJ, Garza RD, Champagne-Langabeer T, Langabeer JR. Alternatives to arrest for illicit opioid use: a joint criminal justice and healthcare treatment collaboration. Subst Abuse. 2020;14:1178221820953390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davoust M, Grim V, Hunter A, et al. Examining the implementation of police-assisted referral programs for substance use disorder services in Massachusetts. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;92:103142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kopak A, Gleicher L. Law enforcement deflection and pre-arrest diversion programs: a tale of two initiatives. J Adv Justice. 2020;3:37–55. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.