Abstract

The past decade witnessed an explosion of public health/public safety collaborations. Many emerged as pragmatic responses to the opioid epidemic, where communities struggled to help individuals at risk of fatal and nonfatal overdoses. Multidisciplinary programs formed to actively engage people with services, including harm reduction, treatment, and peer support, instead of arrest. These initiatives blur traditional lines between public safety, health, treatment, and services. Novel applications of HIPAA and 42 CFR Part 2 created confusion, sometimes discouraging new ways of doing business and other times leading to a disregard for individual privacy protections in the interest of “doing the right thing.” Neither is ideal. In this article, the authors present a framework for collaborations to navigate issues related to privacy, review relevant laws, provide a practical application to public health/public safety partnerships, and offer practice pointers. With this resource, stakeholders are empowered to create effective and compliant overdose response programs.

Keywords: alternatives to incarceration, collaboration, deflection, 42 CFR Part 2, HIPAA, prearrest diversion, privacy, substance use disorder

Communities across the country are developing public health/public safety partnerships specifically to address mental illness and addiction in the community. Often called “prearrest diversion” or “deflection” programs, the composition of these partnerships varies, as do the partners they engage and the methods they employ.1 Deflections offers individuals—without fear of arrest—connection to substance use treatment and needed community services through teams that often include law enforcement, social workers, peer specialists, clinicians, and others. After completing an initial intake, individuals receive a full assessment and care plan with ongoing follow-up. These initiatives feature collaboration between law enforcement, the community, hospitals, public health providers, substance use treatment providers, and other community service providers.2 Some target a specific population, while others are more generally focused on “at-risk” individuals.3–5 These multisystem initiatives blur traditional lines between public safety, public health, health care, treatment, and recovery services.

The policies, practices, and regulations that historically govern information sharing can be confusing in this environment.6 Sometimes stakeholders resist collaborative efforts, arguing that sharing information is illegal; others largely ignore privacy requirements in the spirit of “helping people” or “saving lives.” Neither is ideal. In this article, we (1) explore key privacy requirements applicable to health and substance use disorders (SUDs), (2) introduce a framework that clarifies each team member's relationship to protected information and ensures the ongoing protection of sensitive information, and (3) offer practice and policy recommendations that promote effective and secure collaboration between public health and public safety.

Federal Privacy Laws

This article focuses on the specific implications of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (“HIPAA”) and 42 USC §290dd-2 Confidentiality of Records (initial effective date July 1, 1944)/CFR Part 2 (“Part 2”). HIPAA, and its administrative rules detailing privacy, security, storage, and other compliance expectations, was developed to address the public's demands that health information be kept safe from authorized disclosure during the advent of standardized electronic billing for health care services. Despite general familiarity with HIPAA, it is often misinterpreted by policy makers, program designers, and the general public. People frequently assume that all health-related information is subject to HIPAA without considering whether the institution collecting it is a covered entity under the law. Given widespread misunderstanding of HIPAA, authors recommend that all readers take time to refresh their understanding of HIPAA7–10

42 CFR Part 2 was first enacted in the 1940s to protect individuals with SUDs who often experienced discrimination at the hands of health care providers because of their substance use. This statute and its administrative rules are together known as Part 2.8,11 Part 2 remains a bit more conservative than HIPAA, for several reasons. First, it was implemented before addiction was recognized by the field of medicine as an illness or disease. At that time, it would have been highly unusual for health care—let alone public health or criminal justice—to be involved in addiction treatment. Second, Part 2 predates HIPAA, electronic health records, medication-assisted treatment, drug courts, prosecutorial diversion, mobile response, or deflection. It is an old policy, and there is general recognition that Part 2 does not account for our modern approach to addiction. However, stigma and criminalization of addiction persist, as does the need to protect people with addiction from discrimination. In 2020, legislation brought about a partial alignment of Part 2 with HIPAA. There are still key differences between the ways these laws treat information.12

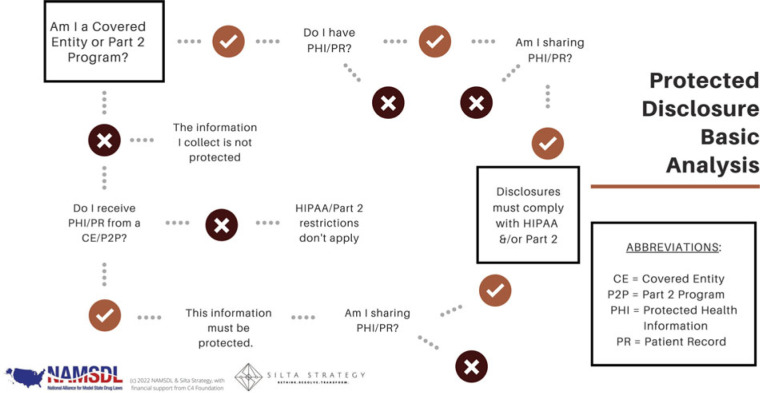

The privacy protections under HIPAA and Part 2 are unique, distinct, and ever evolving. Stakeholders working together as part of a public health and public safety collaborative must understand both sets of privacy requirements, when they attach to individual team members or the team, and how to honor all necessary protections. The following framework was developed to assist with this analysis. It includes a decision-making tool, followed by a step-by-step summary with examples of its application to multidisciplinary teams. Readers are also directed to Supplement Digital Content materials (available at http://links.lww.com/JPHMP/B21), including a privacy requirement comparison chart, maintained online.13,14

A Framework for Compliance

Figure 1 provides a framework for compliance.

FIGURE 1.

Compliance in public health-public safety collaboration. Used with permission. This figure is available in color online (http://www.JPHMP.com).

1. Is the originating entity obligated to protect the information? If information is gathered by a Covered Entity or Part 2 program, analysis regarding privacy requirements must continue. Otherwise, the information need not be protected (at least not yet, and not under these laws). HIPAA applies to “covered entities,” which are health plans, health care clearinghouses, and health care providers who transmit any health information in electronic form in connection with covered transactions. Part 2 covers “Part 2 programs,” which are generally federally funded programs that provide treatment or rehabilitation programs, and practitioners providing SUD diagnosis, treatment, or referral for treatment.

Sometimes it is easy to identify a program or activity that is subject to HIPAA/Part 2. For example, a paramedic delivering lifesaving medical intervention is most likely part of a HIPAA covered entity. HIPAA provides for public health authority access to protected health information (PHI) for the purpose of preventing or controlling disease, injury, or disability—in addition to any specifically carved out covered and noncovered functions. But how about the counselor working for an SUD treatment center? This could easily be both a HIPAA covered entity and a Part 2 program. A police officer or sheriff's deputy who responds to an overdose is generally not initially bound by either HIPAA or CFR42; however, many deflection programs require an additional level of nuance. Although a police officer who responds to a call for service may not be bound by either law, the licensed social worker who co-responds may be. That answer will depend on the individual's employer, responsibilities, and funding source. A social worker who connects community members to housing resources (nonspecific to health or substance use) is probably not considered a covered entity. On the other hand, conducting assessments, making referrals for treatment and services, or offering treatment groups will likely implicate HIPAA and Part 2.

2. What information is protected? If the covered entity/Part 2 program has Protected Health Information or Part 2 Patient Records, protections must be in place for retaining and sharing this information. HIPAA safeguards “PHI,” which is all individually identifiable health information held or transmitted by a covered entity or its business associate, in any form or media, whether electronic, paper, or oral. The restrictions under Part 2 apply to the entire “patient record” on referral and intake and not simply the information pertaining to an SUD. This includes any information, whether recorded or not, created by, received, or acquired by a Part 2 program relating to a current or former patient (eg, diagnosis, treatment, and referral for treatment information, billing information, e-mails, voice mails, and texts). It is important to note that while HIPAA safeguards an individual's health and demographic information, Part 2 more broadly cloaks the entire patient record of current and former patients. A patient is “any individual who has applied for or been given diagnosis, treatment, or referral for treatment.” This includes “any individual who, after arrest on a criminal charge, is identified as an individual with a substance use disorder in order to determine that individual's eligibility to participate in a Part 2 program.”

3. How can protected information be shared? HIPAA and Part 2 each describe parameters for sharing information under a range of circumstances. De-identified or aggregated data can be disclosed without restriction. The easiest way to share details from protected information/records is to remove all identifiers and enough of the contents that there is no reasonable basis to identify an individual. It is advisable to seek advice from counsel to confirm this threshold is reached. While de-identified information can be linked together to track outcomes, those outcomes cannot be traced to the specific individuals being served. This limits its utility for the purpose of direct client service and case management. It is also possible to share aggregated data. This could include summary reports such as the number of new participants enrolled in the program, average length of program engagement, or percentage of successful referrals. There are no restrictions on the use or disclosure of de-identified or aggregate health or SUD information, and both approaches are useful ways to examine program performance. However, they are not adequate for coordinating care.

Individually identifiable information and records can be disclosed in accordance with the required permissions and protections, which often require patient consent and limit disclosure to the minimum necessary information. Part 2 only permits information sharing without patient consent under 3 circumstances: bona fide medical emergency; scientific research (as defined by HIPAA, US Department of Health & Human Services [HHS], or the Food and Drug Administration), audit, or program evaluation; and appropriate court order. Deflection teams will find it noteworthy that Part 2 continues to prohibit law enforcement's use of SUD patient records in criminal prosecutions against patients, absent a court order. Even where Part 2 now incorporates some familiar HIPAA language (such as disclosures for treatment, payment, and operations), these functions require consent.

HIPAA provides for a more extensive disclosure of information without authorization: to HHS, to the individual (unless required for access or accounting of disclosures); treatment, payment, and health care operations; opportunity to agree or object; incident to an otherwise permitted use and disclosure; public interest and benefit activities (12 are listed); and limited data set for the purposes of research, public health, or health care operations. Psychotherapy notes are excluded from this list and always require an authorization. Generally, all other HIPAA disclosures require authorization/consent.

It is worth a reminder that sharing information includes its transmission in any form or media, whether electronic, paper, or oral. Part 2 disclosures are broadly defined as any means to communicate any information identifying a patient as being or having been diagnosed with an SUD, having or having had an SUD, or being or having been referred for treatment of an SUD either directly, by reference to publicly available information, or through verification of such identification by another person. One final note—be sure to include a notice of all statutory restrictions on redisclosure (especially under Part 2) and obtain the requisite promises from the recipient prior to information distribution.

4. What needs to be done by the recipient to protect the information? Generally, the receiving entity must honor the protected status of the information. Expectations are delineated in the applicable laws for business associates, qualified service organizations, and other named recipients. Under HIPAA, a business associate is “a person or organization (other than a member of a covered entity's workforce) using or disclosing individually identifiable health information to perform or provide functions, activities, or services for a covered entity.” Similarly, a Qualified Service Organization under Part 2 “provides services to a Part 2 program, such as data processing, bill collecting, dosage preparation, laboratory analyses, or legal, accounting, population health management, medical staffing, or other professional services, or services to prevent or treat child abuse or neglect.” In both cases, a written agreement containing certain required provisions must be executed before any exchange of information/records can take place. Among other things, the recipient acknowledges that in receiving, storing, processing, or otherwise dealing with any protected information/records, it is fully bound by the relevant federal regulations. Recipients also agree to resist in judicial proceedings any efforts to obtain access to patient identifying information. Additional recipient categories relevant to deflection, including research, are carved out under HIPAA and Part 2, with accompanying obligations.

Implications for Policy & Practice

Compliance is possible! Public health/public safety partnerships can use a simple framework to identify key points where information must be protected.

Programs must fully understand the flow of patient information, from its initial collection through final program engagement, so each disclosure is accounted for and protected.

Program policies, procedures, data management practices, documentation, and training should clearly articulate roles and responsibilities regarding data sharing.

Deflection programs, specifically, may need to seek consultation from professionals with specific expertise in the identification and application of HIPAA, Part 2, and other privacy laws and their amendments.

Discussion

Collaborative public health/public safety programs offer new responses that treat SUDs as a health condition—all while honoring privacy requirements. We recommend the following annual review of practices. First, programs should document and regularly update the roles, responsibilities, policies, and privacy requirements. Training must ensure they are understood and implemented as intended. Second, a program walk through should identify and document key points of engagement and collaboration for clients. This can help manage and organize consent and disclosures, confirm proper application of privacy rules, and trace regular procedural disclosures (ie, conversations, team meetings, etc). Third, seek consultation from HIPAA and Part 2 professionals who can review program setup and identify key decision points. This process should preserve the operations and intent of the program while incorporating any necessary privacy practices. Finally, evaluate how current information management systems ensure compliance. Data must be adequately protected and disclosures facilitated in compliance with the law while also serving program needs. An external, dedicated data management system that is not simply in a Google drive or the “home” system of any one partner is preferred. That system must be compliant with HIPAA data privacy and security rules, so information is only accessible to those with legal standing.

There is no need for uncertainty and confusion about privacy and compliance to hinder public health and public safety partnerships. Using a simple framework for review, programs are empowered to create an approach that protects both the health and privacy interests of the individuals they serve. Understanding and complying with federal policy regulations contribute to the long-term sustainability of public health/public safety partnerships by increasing public trust, embracing client protection, and improving communication among partners.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: Cordata Healthcare Innovations, LLC, provides a technology platform and supports deflection programs in several states.

Conflicts of Interest: None.

Human Participant Compliance Statement: This article does not include data or information from individuals.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citation appears in the printed text and is provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (http://www.JPHMP.com).

Contributor Information

Michele Worobiec, Email: michele.worobiec@siltastratgy.com.

Kelly C. Firesheets, Email: kelly.firesheets@cordatahealth.com.

References

- 1.Charlier J, Reichert J. Police-led responses to behavioral health challenges. J Adv Justice. 2021;3:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 2.PAARI The Police-Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative. Home page. http://bit.ly/2jynY3S. Published 2016. Accessed January 19, 2022.

- 3.Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system. JAMA. 2009;301(2):183–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friese B, Wilson C. Diverting homeless substance users from hospitalization and incarceration: an innovative agency collaboration. J Soc Work Pract Addict. 2021;22(2):137–142. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlem CHG, Scalera M, Anderson G, et al. Recovery Opioid Overdose Team (ROOT) pilot program evaluation: a community-wide post-overdose response strategy. Subst Abuse. 2021;42(4):423–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarty D, Rieckmann T, Baker RL, McConnell KJ. The perceived impact of 42 CFR Part 2 on coordination and integration of care: a qualitative analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(3):245–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.US Department of Health & Human Services. HIPAA for professionals. https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/index.html. Published June 16, 2017. Accessed February 10, 2022.

- 8.National Archives and Records Administration. Electronic Code of Federal Regulations (eCFR). https://www.ecfr.gov. Accessed February 10, 2022.

- 9.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Are you a covered entity? https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Administrative-Simplification/HIPAA-ACA/AreYouaCoveredEntity. Published 2019. Accessed February 9, 2022.

- 10.HHS.gov. Office for Civil Rights (OCR). https://www.hhs.gov/ocr/index.html. Published December 18, 2015. Accessed February 9, 2022.

- 11.SAMHSA. Confidentiality regulations FAQs. https://www.samhsa.gov/about-us/who-we-are/laws-regulations/confidentiality-regulations-faqs. Published July 15, 2013. Accessed January 28, 2022.

- 12.SAMHSA. Center of Excellence for Protected Health Information (CoE-PHI). https://www.samhsa.gov/national-center-excellence-protected-health-information. Accessed February 9, 2022.

- 13.National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws. Home. http://namsdl.org. Accessed February 11, 2022.

- 14.Siltastrategy.com. Home page. http://siltastrategy.com. Published 2022. Accessed February 11, 2022.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.