Abstract

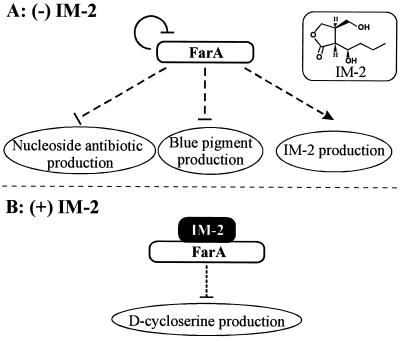

IM-2 [(2R,3R,1′R)-2-1′-hydroxybutyl-3-hydroxymethyl γ-butanolide] is a γ-butyrolactone autoregulator which, in Streptomyces lavendulae FRI-5, switches off the production of d-cycloserine but switches on the production of a blue pigment and several nucleoside antibiotics. To clarify the in vivo function of an IM-2-specific receptor (FarA) in the IM-2 signaling cascade of S. lavendulae FRI-5, a farA deletion mutant was constructed by means of homologous recombination. On several solid media, no significant difference in morphology was observed between the wild-type strain and the farA mutant (strain K104), which demonstrated that the IM-2–FarA system does not participate in the morphological control of S. lavendulae FRI-5. In liquid media, the farA mutant overproduced nucleoside antibiotics and produced blue pigment earlier than did the wild-type strain, suggesting that the FarA protein acts primarily as a negative regulator on the biosynthesis of these compounds in the absence of IM-2. However, contrary to the IM-2-dependent suppression of d-cycloserine production in the wild-type strain, overproduction of d-cycloserine was observed in the farA mutant, indicating for the first time that the presence of both IM-2 and intact FarA are necessary for the suppression of d-cycloserine biosynthesis.

Members of the filamentous, gram-positive bacterial genus Streptomyces are versatile producers of many secondary metabolites, including over two-thirds of all known antibiotics used in human medicine and in agriculture (1, 2). These antibiotics are products of complex biosynthetic pathways, and their production occurs in a growth phase-dependent manner (4) generally coinciding with morphological differentiation on solid media. Among factors known to affect antibiotic production and/or morphological differentiation in streptomycetes (5, 6, 9, 11, 43), γ-butyrolactone autoregulators have been shown in several streptomycetes to serve as extracellular signaling molecules that determine the onset of these two noteworthy characteristics (13). Among the known γ-butyrolactone autoregulators, the earliest known was A-factor (7, 15, 16), which is required for both streptomycin production and sporulation in a streptomycin-negative (Str−) and sporulation-negative (Spo−) mutant of Streptomyces griseus. Other well-studied γ-butyrolactone autoregulators are virginiae butanolides (VBs), which control virginiamycin production in Streptomyces virginiae (23, 40), and SCB1, which induces the precocious production of actinorhodin and undecylprodigiosin in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) (38). The most unique among the γ-butyrolactone autoregulators is IM-2 [(2R,3R,1′R)-2-1′-hydroxybutyl-3-hydroxymethyl-γ-butanolide] of Streptomyces lavendulae FRI-5. In contrast to the solely positive effects exerted by other members of the autoregulator family, IM-2 is capable not only of switching on the production of a blue pigment (BP) and nucleoside antibiotics (showdomycin and minimycin) but also of switching off the production of the antituberculosis antibiotic d-cycloserine (DCS) (8).

In vitro studies of an IM-2-specific receptor protein (FarA) (21, 34, 39) have indicated that FarA is a dimeric DNA binding protein that, in the absence of IM-2, recognizes and binds to specific DNA sequences situated in the promoter region of a target gene. IM-2 binding to FarA causes FarA to dissociate from the DNA, which in turn allows the transcription of the target gene to occur. Similar data have been obtained in vitro for a VB-specific receptor (BarA) (19, 20) and an A-factor-specific receptor (ArpA) (29, 32), suggesting that all the autoregulator receptors express a common activity as transcriptional repressors. Yet a common in vivo trait on the autoregulator-dependent cascade has not been determined by phenotypic analyses of receptor-deficient mutants. When an ArpA− mutant of S. griseus was created in an A-factor-negative background, the defect in sporulation was restored with even earlier initiation than for the wild-type (Str+ Spo+) strain, and the defect in streptomycin production was restored to a further 10-fold overproduction compared to that of the wild-type strain (25), indicating that ArpA acts solely as a repressor of the two processes. However, no morphological difference was observed between wild-type S. virginiae and a barA null mutant (26, 27), indicating that the VB-specific receptor BarA is not involved in morphological differentiation. Furthermore, in the barA null mutant, virginiamycin production was suppressed to only 10% that of the wild-type strain and biosynthesis of VB itself was abolished, which latter trait is not clear for ArpA. Therefore, it is apparent that further investigation of another autoregulator-dependent cascade is needed in order to determine a common trait that will enable us to predict or manipulate the autoregulator-dependent secondary metabolism in Streptomyces species.

In this study, to confirm that FarA is actually involved in the IM-2 signaling cascade of S. lavendulae FRI-5 and also to identify common traits of autoregulator-dependent phenotypes, a farA deletion mutant of S. lavendulae was constructed using homologous recombination, and a phenotypic comparison between the wild-type strain and a strain with a farA deletion was reported. Similar to the case of VB biosynthesis in S. virginiae, FarA was found to regulate IM-2 biosynthesis in S. lavendulae. Lines of evidence are presented showing that FarA is involved as a negative regulator in the production of BP and nucleoside antibiotics. Moreover, it was found that in addition to the presence of IM-2, intact FarA should be present to suppress DCS production. This regulation is novel in autoregulator signaling and suggests that an autoregulator-bound receptor itself, rather than the unbound receptor, could be an important component in the autoregulator signaling cascade.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, growth conditions, and conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to S. lavendulae FRI-5.

S. lavendulae FRI-5 (MAFF10-06015; National Food Research Institute, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fishers, Tsukuba, Japan) was cultured as described previously at 28°C (8) in medium B (containing [in grams per liter] yeast extract, 7.5; glycerol, 7.5; NaCl, 1.25 [pH 6.5]) for antibiotic production, in liquid medium containing half volumes each of YEME medium (12, 17) and Trypticase soy broth (Oxoid) for preparation of total DNA, and on ISP medium 2 (Difco) for spore formation. For conjugal transfer of DNA into S. lavendulae FRI-5, the methylation-deficient E. coli strain ET12567 (dam-13::Tn9 dcm-6 hsdM hsdS) (24) containing the RP4 derivative pUZ8002 (33) was used as the donor. E. coli K-12 strain JM101 (Toyobo) was used for routine subcloning. The plasmids used were pIJ8606 (J. H. Sun and M. J. Bibb, personal communication), a pIJ2925 (14) derivative containing a thiostrepton resistance gene (tsr), pKC1132 (3), and pSET152 (3). Procedures for standard DNA manipulation in E. coli and Streptomyces were described previously (reference 35 and references 12 and 17, respectively). All chemicals were of reagent or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade and were purchased from Nacalai Tesque, Takara Shuzo, or Wako Pure Chemical Industries.

Construction of a farA deletion mutant and a farA complemented strain.

A 2.8-kb EcoRI (blunt-ended)-BstPI fragment containing the 5′ upstream sequence plus the 5′ 123 bp of farA was isolated from pMW101, a pUC19 derivative containing an 8-kb PstI fragment (39), and the fragment was cloned into the EcoRI and SmaI sites of pIJ8606 to give pSG101. A 2.8-kb PvuII-PstI fragment carrying the 3′ 30 bp of farA plus the 3′ downstream sequence from pMW101 was cloned into the PstI and blunt-ended SphI sites of pSG101, generating pSG102. This reconstructed a contiguous 5.6-kb segment of the chromosome, except that a 510-bp BstPI-PvuII fragment internal to farA was replaced with the 1.1-kb tsr gene. The entire 6.7-kb insert was recovered from pSG102 as an EcoRI-PstI fragment and cloned into the EcoRI and PstI sites of pKC1132, yielding pSG103.

E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002) transformed with pSG103 was conjugated with S. lavendulae FRI-5 K101 as previously described (22). Exconjugants in which the plasmid pSG103 had presumptively integrated at the farA locus by a single crossover via homologous recombination were selected with apramycin. After three rounds of incubation at 28°C on ISP medium 2 containing 5 μg of thiostrepton per ml, putative farA::tsr deletion mutants formed from the second crossover were detected by their apramycin sensitivity. One of the strains was designated strain K104. To complement the farA deletion mutant (K104), a 2.1-kb SacI fragment containing the entire farA gene with promoter was isolated from pMW101 and cloned into SacI-digested and blunt-ended pSET152, generating pSG104. After conjugal transfer of pSG104 from E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002) to strain K104, apramycin resistance exconjugants were obtained and designated strain K105. The resulting strains were analyzed by Southern hybridization. The probe used was a 902-bp farA internal fragment amplified by PCR from pMW101 using farAN-3 (5′-CGGGATCCTCATCGGCACACCACGGCCCG-3′) and farAC-3 (5′-CGGGATCCTGCACAGGGGAAAGCGGA-3′) as primers.

IM-2 binding assay.

Crude extracts for the IM-2 binding assay were prepared as described previously (34). IM-2 binding activity was routinely assayed using the ammonium sulfate precipitation method (18) with [3H]IM-2-C5 (10 pmol; 40 Ci/mmol) in the presence and absence of non-labeled IM-2-C5 (15 nmol; 1,500-fold molar excess). The radioactivity in the solution was measured using a liquid scintillation counter (model LS6000; Beckman).

Detection of BP.

At the indicated times, supernatants were obtained by centrifugation (15,000 × g, 4°C, 10 min) of culture broths in medium B and were filtrated through 0.2-μm-pore-size filters, and the absorbance at 590 nm was measured.

Analysis of nucleoside antibiotic and DCS production.

For measuring the production of nucleoside antibiotics, culture broth (60 ml of medium B) in a 500-ml baffled flask was collected after 31 h of cultivation, mycelia were removed by suction filtration, and the filtrate was adjusted to pH 7.0. The filtrate was applied to an active charcoal column (5 g) followed by washing with 100 ml of water, and the absorbed compounds were eluted with 200 ml of methanol. The methanol eluent was evaporated, dissolved in 5 ml of water, lyophilized, and redissolved in 1 ml of water for bioassay. The samples thus prepared contain both showdomycin and minimycin (8), and the bioassay was performed by measuring clear-zone formation with Bacillus subtilis PCI219 as a test organism on glucose-Simmone's agar medium as described by Nishimura et al. (28) after incubation for 2 to 3 days at 30°C. Authentic showdomycin (a generous gift from Shionogi & Co., Ltd.) was used as the standard for the bioassay.

For DCS production, samples in medium B were withdrawn at the indicated times and clarified by filtration through 0.2-μm-pore-size filters. Aliquots (50 μl) were separated and quantified by HPLC (cation-exchange column; Senshu Pak SCX-1251-N; Senshu Scientific Co., Ltd.) with 10 mM ammonium acetate (pH 5.0) as solvent and detection at 210 nm using authentic DCS (Sigma) as the standard.

Morphological assessment.

Spores of the wild-type strain, a farA deletion mutant (strain K104), and a farA complemented strain (strain K105) were streaked or plated out on ISP medium 2, oatmeal agar (8), MS agar (mannitol plus soya flour) (10), minimal medium agar containing 0.5% (wt/vol) mannitol as a carbon source (12, 17), R2 agar (12, 17), and modified SMMS agar (supplemental minimum medium, solid) as described by Takano et al. (38) and were cultivated at 28°C for 7 days before they were analyzed for morphological differences.

Analysis of IM-2 production.

Spores of each strain (6.6 × 108 spores per 25 ml of medium) were inoculated on ISP medium 2 agar plates and incubated at 28°C for 19 h. Cultures from four plates, including agar, were cut into small pieces and kept frozen at −80°C for 1 h. Ethanol (60 ml) (adjusted to pH 2.0 with HCl) was added, the supernatant was obtained by centrifugation and evaporated, and the residue was extracted with ethyl acetate (20 ml). The ethyl acetate extract was evaporated and dissolved in methanol and clarified by passage through cotton, and the filtrates were evaporated. The residue after evaporation was redissolved in methanol-H2O (4:6) at a concentration of 200 mg/ml and purified in aliquots of 50 μl by HPLC (C18 reverse-phase column; 10 by 250 mm; Cosmosil C18), with methanol-H2O (4:6) as a solvent and detection at 210 nm. Fractions (19.8 to 23.4 ml) corresponding to the elution position of authentic IM-2-C4 were combined, evaporated, and dissolved in 3 ml of methanol for the IM-2 bioassay. IM-2 activity in the sample was assayed by measuring the IM-2-dependent production of BP (42). One unit of IM-2 activity is the minimum amount required for the induction of BP production and corresponded to 0.6 ng (2.97 nM) of IM-2-C5 per ml (36). Authentic IM-2-C4 was synthesized as described previously (36).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Insertional inactivation of farA in S. lavendulae FRI-5.

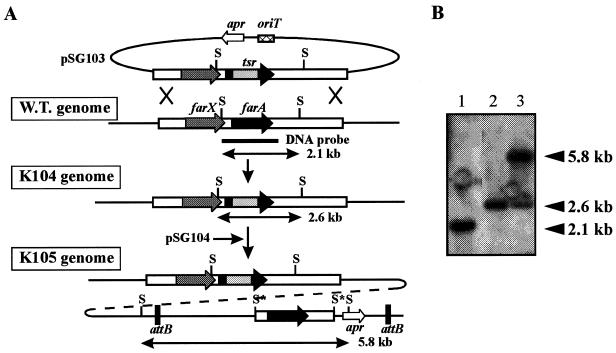

To assess the regulatory role(s) of FarA in the secondary metabolism of S. lavendulae FRI-5, a 510-bp BstPI-PvuII fragment internal to farA was replaced with a thiostrepton resistance gene (tsr) by which 170 amino acids, corresponding to the 42nd to 211th amino acids of FarA (221 amino acids), were deleted. This deletion includes those amino acids constituting the second helix of the helix-turn-helix DNA binding motif (32nd to 51st amino acids) in the N terminus and the presumed autoregulator binding region in the C-terminal half (37); thus, the resulting truncated protein should be devoid of both DNA and IM-2 binding activity. The farA deletion allele together with ca. 2.8 kb of the 5′- and 3′-flanking regions was cloned into pKC1132, a nonreplicating plasmid in streptomycetes, to generate pSG104. Conjugal transfer from E. coli ET12567(pUZ8002) harboring pSG104 to S. lavendulae FRI-5 gave apramycin-resistant exconjugants in which pSG104 integration by a single crossover event was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). After three rounds of sporulation of the pSG104-integrated strain in the presence of thiostrepton, thiostrepton-resistant and apramycin-sensitive colonies were obtained. Southern blot analysis of representative strains, such as strain K104, using PCR-amplified farA as a probe showed that a 2.1-kb SacI fragment in the wild-type strain shifted to a 2.6-kb fragment in strain K104 (Fig. 1), confirming that the K104 chromosome contained only the deleted farA gene by a second crossover.

FIG. 1.

Construction of a farA deletion mutant and its complemented strain. (A) Schematic representation of the strategy used for the disruption of farA and its complementation. The solid arrow represents the farA gene, the dark gray arrow represents the farX gene, whose function is unknown, the light gray arrow represents the thiostrepton resistance gene (tsr), the open arrow represents the apramycin resistance gene (apr), the cross-hatched box represents the oriT sequence, and the black box represents the φC31 attachment site (attB site). Abbreviations: W.T., wild type; S, SacI; S∗, disrupted SacI site. (B) Southern hybridization analysis of chromosomal DNA from strains K101 (wild-type strain; lane 1), K104 (a farA deletion mutant; lane 2), and K105 (a farA complemented strain derived from strain K104; lane 3) digested with SacI. The probe used was the 0.9-kb PCR-amplified fragment containing the entire farA gene.

Phenotypic characterization of a farA deletion mutant (K104) in liquid culture.

To confirm the absence of a functional IM-2 receptor (FarA) in strain K104, IM-2 binding activity was measured with tritium-labeled IM-2-C5 using crude extracts prepared from 8.5-h cells of strain K104 and the wild-type strain (Table 1). The 8.5-h time of cultivation was carefully selected, because BP production at 10.5 h in the wild-type strain indicates the presence at 8.5 h of endogenous IM-2, which usually precedes BP production by about 2 h. The presence of endogenous IM-2 not only inhibits the IM-2 binding assay by competing with labeled IM-2 but also enhances the amount of FarA in the wild-type strain by derepressing farA transcription (21, 39). The results of the IM-2 binding assay demonstrated that strain K104 lost almost all IM-2 binding activity in comparison with a wild-type strain (strain K101).

TABLE 1.

IM-2 binding activity and IM-2 production of the S. lavendulae FRI-5 wild-type strain (strain K101), a farA mutant (strain K104), and a farA complemented strain (strain K105)a

| Strain | IM-2 binding activity (pmol/mg of protein [%]) | IM-2 produced by surface-grown culture (nM) |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type (K101) | 1.55 (100) | 6.48 |

| farA deletion mutant (K104) | 0.11 (7) | 0.71 |

| K104 complemented with intact farA (K105) | 1.24 (80) | 7.13 |

All values were highly reproducible.

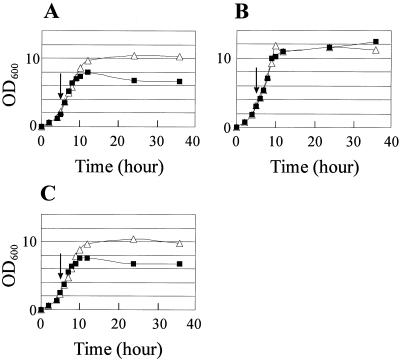

To examine whether the farA mutation affects growth characteristics in liquid culture, the growth of strains K101 and K104 was measured with or without exogenous addition of IM-2 at 5 h of cultivation (Fig. 2). While the growth of the wild-type strain was repressed by the addition of synthetic IM-2-C5 at a final concentration of 100 nM, strain K104 continued to grow irrespective of IM-2 addition, indicating that strain K104 became insensitive to the presence of IM-2.

FIG. 2.

Growth curves in liquid culture of the wild-type strain (strain K101) (A), a farA deletion mutant (strain K104) (B), and a farA complemented strain (strain K105) (C). Each strain was grown in medium B at 28°C without IM-2 addition (open triangles) or with IM-2 addition (final concentration, 100 nM) at 5 h of cultivation (solid squares). Growth was monitored by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Arrows indicate the timing of the IM-2 addition.

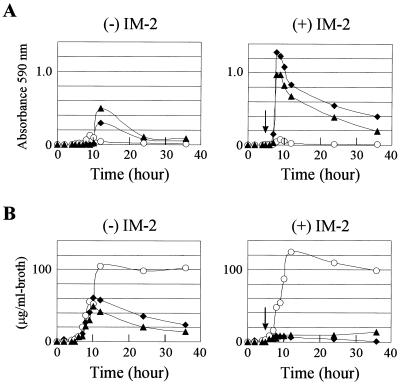

To evaluate how the farA deletion affects IM-2 signaling, BP production in strain K104 was initially monitored by measuring the absorbance at 590 nm (Fig. 3A). In the wild-type strain (strain K101) without exogenous IM-2 addition, BP production was observed after 10.5 h of cultivation, while the addition of IM-2 at 5 h of cultivation induced BP production from 7 h of cultivation. In the farA mutant strain K104, however, regardless of IM-2 addition, BP production was observed after 8 h of cultivation, with much reduced levels of BP (about 4% that of the wild-type strain with external IM-2). This phenomenon in strain K104 resembled that of the VB receptor disruptants of S. virginiae in which virginiamycin production began much earlier, if not occurring constitutively, than in the parental strain but at an amount of only 10% that of the parental strain (26, 27).

FIG. 3.

Time courses of BP production (A) and DCS production (B) in a farA deletion mutant and a wild-type strain. The amounts of BP and DCS at the indicated times were measured as described in Materials and Methods. Strains K101 (wild-type strain; solid diamonds), K104 (farA mutant; open circles), and K105 (complemented strain; solid triangles) were grown at 28°C in medium B. The designation (+) IM-2 indicates that exogenous IM-2 (final concentration of 100 nM) was added to the culture at 5 h of cultivation, and cultivation was continued further, and (−) IM-2 indicates that there was no exogenous IM-2 addition. Arrows indicate the timing of the IM-2 addition.

Similar to BP production, the production of nucleoside antibiotics (showdomycin and minimycin) is induced by IM-2 in a wild-type strain (8). However, without the addition of IM-2, the production was small or negligible, but external IM-2 clearly caused production (8). This suggests that the concentration of endogenously produced IM-2 (about 27 nM) was not high enough to fully activate the biosynthesis of nucleoside antibiotics and that full activation requires that much higher concentrations of IM-2 be generated by external IM-2 addition. In the farA mutant strain K104, however, the production of nucleoside antibiotics was higher even without IM-2 addition than was that of the wild-type with the external addition of IM-2 (Fig. 4), indicating that the farA deletion resulted in overproduction of nucleoside antibiotics. This phenomenon is similar to the case of an A-factor receptor (ArpA)-deficient mutant of S. griseus in which a 10-fold final overproduction of streptomycin was observed, with a 1-day earlier initiation of production than in the wild-type strain (25), suggesting that farA is, as proposed for arpA in the streptomycin biosynthesis of S. griseus, the primary negative regulatory gene for the biosynthesis of nucleoside antibiotics in S. lavendulae FRI-5.

FIG. 4.

Comparison of nucleoside antibiotic production between strain K101 and strain K104 with a bioassay using B. subtilis PCI219. Supernatants from culture broth were applied onto active charcoal columns, and the absorbed compounds were eluted with methanol, concentrated, and used for bioassay. Each strain was cultivated for 31 h without (−) or with (+) IM-2 addition at 5 h of cultivation.

Although phenotypically positive effects on antibiotic production such as those by IM-2 on nucleoside antibiotics and BP are common among autoregulators, phenotypically negative effects on antibiotic production are unusual among γ-butyrolactone autoregulators and are seen only as the termination of DCS by IM-2 (8). Because the repressor function seems common to all the autoregulator receptors (19, 20, 21, 32), we hypothesized that FarA should repress a negative regulator of DCS production and expected that DCS production would be abolished in the farA mutant. However, strain K104 not only continued to produce DCS but also overproduced it (Fig. 3B), suggesting the presence of a completely different mode of regulation by FarA.

Phenotypic characterization of a farA deletion mutant on solid medium.

Recently, the involvement of an A-factor receptor, ArpA, in the morphological control of S. griseus was clearly demonstrated, in which ArpA indirectly represses transcription of the adsA gene encoding an extracytoplasmic sigma factor necessary for morphological differentiation via repressing the adpA gene encoding an activator of adsA (41). To clarify whether farA is involved in the morphological control of S. lavendulae, morphological characteristics of strains K101 and K104 were carefully compared on a range of different solid media. Because no differences in morphology were detected between strains K101 and K104 (data not shown), the IM-2–FarA cascade was concluded to play no role in the morphological differentiation of S. lavendulae FRI-5.

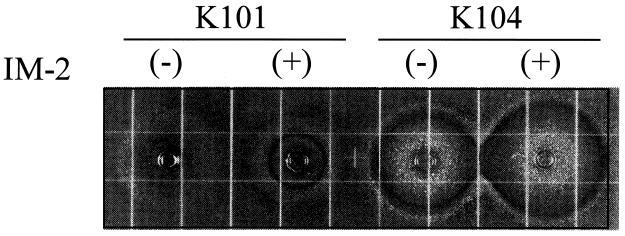

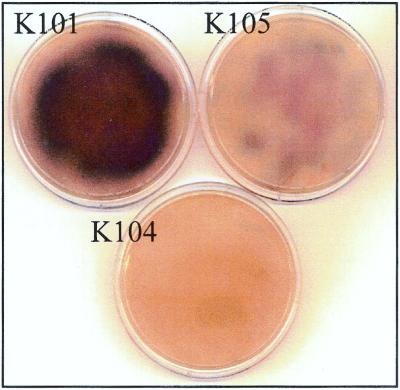

The wild-type strain with a confluent lawn of growth produced a BP-like pigment on ISP medium 2 and R2 agar medium which was lacking or too small to be visible for strain K104 (Fig. 5), indicating that the phenomenon is FarA dependent. Because this phenomenon can be considered to be an IM-2-triggered onset of secondary metabolism on solid media, we assessed the concentration of IM-2 in the solid media (Table 1). As expected, the wild-type strain (K101) produced 6.48 nM IM-2, which is 2.2-fold higher than the minimum effective concentration of IM-2 (2.97 nM). Surprisingly, strain K104 produced only 11% of the amount of IM-2 produced by the wild-type strain, indicating that FarA should be necessary for IM-2 biosynthesis. The similar requirement of an intact autoregulator receptor for the production of a corresponding autoregulator has been observed in the BarA null mutant (26) of S. virginiae and the SCBI receptor (ScbR) mutant of S. coelicolor A3(2) (E. Takano and M. J. Bibb, personal communication). Thus, an autoregulator receptor should generally be involved in the regulation of autoregulator biosynthesis.

FIG. 5.

BP production by strains K101, K104, and K105 on ISP medium 2. Spores of each strain were plated out on ISP medium 2, and plates were incubated for 19 h at 28°C.

trans complementation of a farA deletion mutant.

To confirm that the phenotypic differences observed between the wild-type strain and the farA mutant (strain K104) were due to the lack of functional FarA protein, an intact farA gene was transconjugated and integrated into an attB site of strain K104 via pSG105, a derivative of a Streptomyces integration plasmid, pSET152, containing a ΦC31 attP site and int. The integration of intact farA in apramycin-resistant exconjugants was confirmed by Southern hybridization (Fig. 1), and they were designated strain K105. All the characteristics of strain K105 (the IM-2 binding activity [Table 1], growth in the presence of IM-2 [Fig. 2], BP production [Fig. 3A], DCS production [Fig. 3B], nucleoside antibiotic production [data not shown], and IM-2 production [Table 1]) were restored to the wild-type phenotypes. Furthermore, pigment production on solid media (ISP medium 2 and R2 agar) was also restored in strain K105 (Fig. 5), suggesting that pigment production on solid media is FarA dependent, similar to the FarA-dependent BP production in liquid media. These lines of evidence clearly demonstrated that the phenotypic changes in strain K104 were due solely to the loss-of-function mutation of farA.

All the known γ-butyrolactone autoregulator receptors (FarA as an IM-2 receptor [34], BarA as a VB receptor [30], ArpA as an A-factor receptor [31], and ScbR as an SCBI receptor [Takano and Bibb, personal communication]) are highly conserved in the DNA binding motif present in their N-terminal portions and have been proposed to play roles as transcriptional regulators in antibiotic production (19, 20, 21, 29, 32). Previously, our in vitro analysis of an IM-2-specific receptor, FarA, revealed that one of the target genes of FarA is the farA gene itself (21). The FarA protein in the absence of IM-2 represses farA transcription by binding to specific FarA binding sequences in the farA promoter region. In the presence of IM-2, transcription of farA is derepressed by the dissociation of IM-2-bound FarA from the FarA binding sequences, forming an autoregulatory circuit between IM-2 and FarA.

Phenotypic analyses of a farA deletion mutant revealed that FarA is involved in the IM-2-dependent growth suppression in liquid media, the production of BP and nucleoside antibiotics, and the termination of DCS production, confirming that FarA is a mediator of IM-2 signaling in S. lavendulae. Furthermore, it became clear that FarA is somehow participating in the regulation of IM-2 biosynthesis. However, contrary to the case for the A-factor–ArpA system of S. griseus, no regulatory role in regard to morphology was observed for the IM-2–FarA system, which agreed well with phenomena observed in two other autoregulator systems, namely, the VB-BarA system of S. virginiae and the recently found SCB1-ScbR system of S. coelicolor A3(2) (Takano and Bibb, personal communication). Therefore, a lack of a regulatory role as regards morphology seems to be common, rather than an exception, to γ-butyrolactone autoregulators of streptomycetes.

We propose the following model for the IM-2-mediated signaling cascade for the secondary metabolism of S. lavendulae FRI-5 (Fig. 6). Initially, FarA acts as a transcriptional repressor on farA itself, forming an autoregulatory circuit which should serve to sense and maintain intracellular free IM-2 concentrations under some threshold level in the cells. This autoregulatory circuit has also been observed in the VB-BarA system of S. virginiae (19, 20) and in the recently found SCB1-ScbR system of S. coelicolor A3(2); thus, it seems to be common to γ-butyrolactone autoregulator-receptor systems of streptomycetes. Next, FarA regulates the biosynthesis of IM-2 itself, as shown by the observation that IM-2 production was dramatically decreased in the farA disruptant. Thirdly, the biosyntheses of both BP and nucleoside antibiotics are negatively controlled by FarA. However, there exists a difference in the degrees of regulation. FarA seems to be a primary dominant-negative regulator of the biosynthesis of nucleoside antibiotics, since its disruption resulted in the overproduction of nucleoside antibiotics, a phenomenon identical to ArpA-streptomycin production in S. griseus (25). On the other hand, FarA does not seem to be the dominant regulator of the biosynthesis of BP in that its disruption resulted in earlier initiation of BP production but with a much reduced amount compared to the wild-type strain. S. lavendulae should have an additional regulatory mechanism which terminates the premature initiation of BP, a phenomenon similar to BarA-virginiamycin production in S. virginiae (26, 27). Finally, but most striking for the farA mutant, was the overproduction of DCS, which was completely opposite to the expected lack of DCS production. Supposing that IM-2-unbound FarA is either repressing a repressor or activating an activator of DCS biosynthesis, the loss-of-function mutation of farA should result in the loss of DCS production. Therefore, if unbound FarA is the only functional form, this overproduction phenomenon in the farA mutant is unexplainable and indicates that both the intact FarA and the presence of IM-2 are necessary for the termination of DCS biosynthesis, suggesting as the simplest model that the IM-2–FarA complex may act as a regulator. Because genes under the control of the IM-2–FarA complex are predicted to be bound by the IM-2–FarA complex, searching for DNA fragments bound by FarA in the presence of IM-2 is under way and will give us clues on the signaling mechanism in S. lavendulae in particular and, in general, on the γ-butyrolactone-dependent regulatory cascade in streptomycetes.

FIG. 6.

Proposed model of the IM-2 regulatory cascade leading to the production of secondary metabolites in the absence (A) or presence (B) of IM-2. Solid lines and dashed lines show direct or indirect regulation of expression of subordinate proteins, respectively. Arrows and horizontal lines show activation and repression of the regulation, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Research for the Future Program of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

We are grateful to M. J. Bibb (John Innes Centre, United Kingdom) for helpful discussions regarding the manuscript and to E. Takano (John Innes Centre) for helpful comments on the manuscript. We also thank J. H. Sun (John Innes Centre) for the gift of pIJ8606 and Shionogi & Co., Ltd., for the gift of showdomycin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderson G, Ritchie D A, Cappellano C, Cool R H, Ivanova N M, Huddleston A S, Flaxman C S, Kristufek V, Lounes A. Physiology and genetics of antibiotic production and resistance. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:665–672. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90072-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berdy J. Are actinomycetes exhausted as a source of secondary metabolites? In: Debabov V, Dudnik Y, Danlienko V, editors. Proceedings of the 9th International Symposium on the Biology of Actinomycetes. Moscow, Russia: All-Russia Scientific Research Institute for Genetics and Selection of Industrial Microorganisms; 1995. pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bierman M, Logan R, O'Brien K, Seno E T, Rao R N, Schoner B E. Plasmid cloning vectors for the conjugal transfer of DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces spp. Gene. 1992;116:43–49. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90627-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chater K F, Bibb M J. Regulation of bacterial antibiotic production. In: Kleinkauf H, Dohren H V, editors. Biotechnology. 7. Products of secondary metabolism. Weinheim, Germany: VCH Press; 1997. pp. 57–105. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Demain A L. Microbial secondary metabolism: a new theoretical frontier for academia, a new opportunity for industry. Ciba Found Symp. 1992;171:3–16. doi: 10.1002/9780470514344.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demain A L, Fang A. Emerging concepts of secondary metabolism in actinomycetes. Actinomycetologica. 1995;9:98–117. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hara O, Beppu T. Mutants blocked in streptomycin production in Streptomyces griseus—the role of A-factor. J Antibiot. 1982;35:349–358. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.35.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hashimoto K, Nihira T, Sakuda S, Yamada Y. IM-2, a butyrolactone autoregulator, induces production of several antibiotics in Streptomyces sp. FRI-5. J Ferment Bioeng. 1992;73:449–455. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hobbs G, Obanye A I C, Petty J, Mason J C, Barratt E, Gardner D C J, Flett F, Smith C P, Broda P, Oliver S G. An integrated approach to studying regulation of production of the antibiotic methylenomycin by Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1487–1494. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.5.1487-1494.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hobbs G, Frazer C, Gardner D C J, Cullum J, Oliver S G. Dispersed growth of Streptomyces in liquid culture. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1989;31:272–277. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hood D W, Heidstra R, Swoboda U K, Hodgson D A. Molecular genetic analysis of proline and tryptophan biosynthesis in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): interaction between primary and secondary metabolism—a review. Gene. 1992;115:5–12. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90533-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hopwood D A, Bibb M J, Chater K F, Kieser T, Bruton C J, Kieser H M, Lydiate D J, Smith C P, Ward J M, Schrempf H. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces: a laboratory manual. Norwich, England: The John Innes Foundation; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Autoregulatory factors and communication in actinomycetes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1992;46:377–398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.46.100192.002113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janssen G R, Bibb M J. Derivatives of pUC18 that have BglII sites flanking a modified multiple cloning site and that retain the ability to identify recombinant clones by visual screening of Escherichia coli colonies. Gene. 1993;124:133–134. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90774-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khokhlov A S. Results and perspectives of actinomycete autoregulator studies. In: Okami Y, Beppu T, Ogawara H, editors. Biology of actinomycetes '88. Tokyo, Japan: Japan Scientific Societies Press; 1988. pp. 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khokhlov A S, Tovarova I I, Borisova L N, Pliner S A, Schevshenko L A, Kornitskaya E Y, Ivkina N S, Rapoport I A. A-factor responsible for the biosynthesis of streptomycin by a mutant strain of Actinomyces streptomycini. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1967;177:232–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kieser T, Bibb M J, Buttner M J, Chater K F, Hopwood D A. Practical Streptomyces genetics. Norwich, United Kingdom: The John Innes Foundation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim H S, Nihira T, Tada H, Yanagimoto M, Yamada Y. Identification of binding protein of virginiae butanolide C, an autoregulator in virginiamycin production, from Streptomyces virginiae. J Antibiot. 1989;43:692–706. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kinoshita H, Ipposhi H, Okamoto S, Nakano H, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Butyrolactone autoregulator receptor protein (BarA) as a transcriptional regulator in Streptomyces virginiae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:6986–6993. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.6986-6993.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kinoshita H, Tsuji T, Ipposhi H, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Characterization of binding sequences for butyrolactone autoregulator receptors in streptomycetes. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5075–5080. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.5075-5080.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitani S, Kinoshita H, Nihira T, Yamada Y. In vitro analysis of the butyrolactone autoregulator receptor protein (FarA) of Streptomyces lavendulae FRI-5 reveals that FarA acts as a DNA-binding transcriptional regulator that controls its own synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5081–5084. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.5081-5084.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kitani S, Bibb M J, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Conjugal transfer of plasmid DNA from Escherichia coli to Streptomyces lavendulae FRI-5. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2000;10:535–538. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondo K, Higuchi Y, Sakuda S, Nihira T, Yamada Y. New virginiae butanolides from Streptomyces virginiae. J Antibiot. 1989;42:1873–1876. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacNeil D J, Occi J L, Gewain K M, MacNeil T, Gibbons P H, Ruby C L, Danis S J. Complex organization of the Streptomyces avermetilis genes encoding the avermectin polyketide synthase. Gene. 1992;115:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyake K, Kuzuyama T, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. The A-factor-binding protein of Streptomyces griseus negatively controls streptomycin production and sporulation. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3003–3008. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3003-3008.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakano H, Lee C K, Nihira T, Yamada Y. A null mutant of the Streptomyces virginiae barA gene encoding a butyrolactone autoregulator receptor and its phenotypic and transcriptional analysis. J Biosci Bioeng. 2000;90:204–207. doi: 10.1016/s1389-1723(00)80111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakano H, Takehara E, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Gene replacement analysis of the Streptomyces virginiae barA gene encoding the butyrolactone autoregulator receptor reveals that BarA acts as a repressor in virginiamycin biosynthesis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3317–3322. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.13.3317-3322.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nishimura H, Mayama M, Komatsu Y, Kato H, Shimaoka N, Tanaka Y. Showdomycin, a new antibiotic from a Streptomyces sp. J Antibiot. 1964;17:148–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ohnishi Y, Kameyama S, Onaka H, Horinouchi S. The A-factor regulatory cascade leading to streptomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces griseus: identification of a target gene of the A-factor receptor. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:102–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okamoto S, Nakamura K, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Virginiae butanolide binding protein from Streptomyces virginiae: evidence that VbrA is not the virginiae butanolide binding protein and reidentification of the true binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12319–12326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Onaka H, Ando N, Nihira T, Yamada Y, Beppu T, Horinouchi S. Cloning and characterization of the A-factor receptor gene from Streptomyces griseus. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6083–6092. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6083-6092.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Onaka H, Horinouchi S. DNA-binding activity of the A-factor receptor protein and its recognition DNA sequences. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:991–1000. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4081772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paget M S B, Chamberlin L, Atrih A, Foster S J, Buttner M J. Evidence that the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor ςE is required for normal cell wall structure in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Bacteriol. 1999;181:204–211. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.1.204-211.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruengjitchatchawalya M, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Purification and characterization of the IM-2-binding protein from Streptomyces sp. strain FRI-5. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:551–557. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.551-557.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato K, Nihira T, Sakuda S, Yanagimoto M, Yamada Y. Isolation and structure of a new butyrolactone autoregulator from Streptomyces sp. FRI-5. J Ferment Bioeng. 1989;68:170–173. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sugiyama M, Onaka H, Nakagawa T, Horinouchi S. Site-directed mutagenesis of the A-factor receptor protein: Val-41 important for DNA-binding and Trp-119 important for ligand-binding. Gene. 1998;222:133–144. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00487-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takano E, Nihira T, Hara Y, Jones J J, Gershater C J L, Yamada Y, Bibb M J. Purification and structural determination of SCBI, a γ-butyrolactone that elicits antibiotic production in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11010–11016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waki M, Nihira T, Yamada Y. Cloning and characterization of the gene (farA) encoding the receptor for an extracellular regulatory factor (IM-2) from Streptomyces sp. strain FRI-5. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5131–5137. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5131-5137.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamada Y, Sugamura K, Kondo K, Yanagimoto M, Okada H. The structure of inducing factors for virginiamycin production in Streptomyces virginiae. J Antibiot. 1987;40:496–504. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.40.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamazaki H, Ohnishi Y, Horinouchi S. An A-factor-dependent extracytoplasmic function sigma factor (ςAdsA) that is essential for morphological development in Streptomyces griseus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4596–4605. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4596-4605.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yanagimoto M, Enatsu T. Regulation of a blue pigment production by γ-nonalactone in Streptomyces sp. J Ferment Technol. 1983;61:545–550. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang K, Han L, Vining L C. Regulation of jadomycin B production in Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230: involvement of a repressor gene, jadR2. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:6111–6117. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.21.6111-6117.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]