Abstract

Objective

To review the literature to assess best practices for counseling transgender men who desire gender-affirming surgery on fertility preservation options.

Design

A scoping review of articles published through July 2021.

Setting

None.

Patient(s)

Articles published in Cochrane, Web of Science, PubMed, Science Direct, SCOPUS, and Psychinfo.

Intervention(s)

None.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

Papers discussing transgender men, fertility preservation (FP), and FP counseling.

Result(s)

The primary search yielded 1,067 publications. After assessing eligibility and evaluating with a quality assessment tool, 25 articles remained, including 8 reviews, 5 surveys, 4 consensus studies, 3 retrospective studies, 3 committee opinions, and 2 guidelines. Publications highlighted the importance of including the following topics during counseling: (1) FP and family building options; (2) FP outcomes; (3) effects of testosterone therapy on fertility; (4) contraception counseling; (5) attitudes toward family building; (6) consequences of transgender parenting; and (7) barriers to success.

Conclusion(s)

Currently, there is a lack of standardization for comprehensive counseling about FP for transgender men. Standardized approaches can facilitate conversation between physicians and transgender men and ensure patients are making informed decisions regarding pelvic surgery and future family building plans.

Key Words: transgender men, family-building, fertility preservation

Discuss: You can discuss this article with its authors and other readers at https://www.fertstertdialog.com/posts/xfre-d-22-00004

Fertility preservation (FP) for transgender people, individuals whose sex assigned at birth differs from their gender identity or one’s psychological sense of gender, has garnered increasing attention in recent years. In the United States, an estimated 1.4 million adults and 150,000 youth identify as transgender. Many transgender individuals profess similar family-building desires as cisgender individuals (1). Despite this, the reported rates of FP in this population, compared with the rates of interest in family building through genetic parenthood, are low (2).

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (1), World Professional Association for Transgender Health, and Endocrine Society recommend transgender persons be provided appropriate access to FP services and be informed of the risks of gender-affirming therapy on fertility outcomes (1, 3, 4). More specifically, in transgender men who pursue gender-affirming medical interventions, FP is an important topic to discuss before beginning transition. Hysterectomy and oophorectomy result in irreversible infertility, but the effect of testosterone therapy on the ovaries and future fertility is more ambiguous (5, 6).

Currently, the need for FP counseling in this population has been well-recognized, but actual standardized approaches to help guide professionals involved in counseling have not been established. Standardized templates would likely improve provider knowledge, increase access to FP, and help practitioners and transgender individuals navigate the complexities of family building (2). Therefore, the purpose of this study is to review the literature regarding FP and counseling in transgender men and offer guidance for counseling this patient population. Of note, this review is intended to focus on any individuals with ovaries and a uterus who use medical or surgical means for gender affirmation. The authors acknowledge that there may be other terms to describe such individuals. For the remainder of the article, the authors will use the term transgender men to describe them.

Methods

This was a review of published articles, and institutional review board approval was not required.

Search Strategy

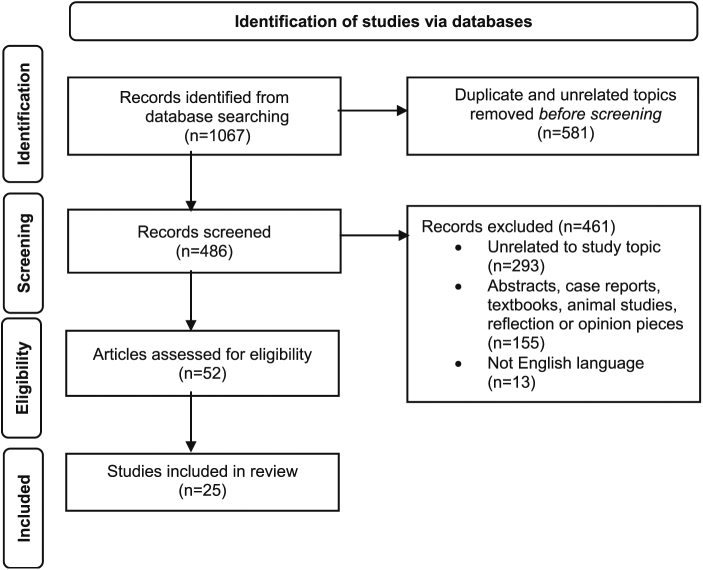

The search strategy was made in collaboration with a Health Sciences Librarian. This study was performed in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for scoping reviews (Fig. 1). Articles published through July 27, 2021, were included. Six databases (Cochrane, Web of Science, PubMed, Science Direct, SCOPUS, and Psychinfo) were searched (Table 1). The Cochrane Library was searched for reviews, protocols, trials, editorials, special collections, and clinical answers. The Web of Science Core Collection was searched with all editions selected. This included Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation, Arts and Humanities Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citations Index, Book Citation Index, Current Chemical Reactions, and Index Chemicus. The Medline database was excluded because it was included within the PubMed database.

Table 1.

Search database.

| Database | Search terms | No. of results |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (((trans men) OR (transmasculine) OR ("female-to-male") OR (transmen) OR (transgender) OR (transsexualism)) AND ((fertility) OR (infertility) OR (pregnancy outcomes)) NOT (diet or nutrition))) | 465 |

| SCOPUS | (((transmasculine) OR (transmen) OR (transgender) OR (transsexualism)) AND ((fertility) OR (infertility))) | 396 |

| Science Direct | (((transmasculine) OR (transmen)) AND ((fertility) OR (infertility))) | 144 |

| Web of Science | (((transmasculine) OR (transmen) OR (transgender) OR (transsexualism)) AND ((fertility) OR (infertility) AND (pregnancy outcomes))) | 18 |

| PsychInfo | 1 - exp fertility 2 - exp transsexualism/ or exp transgender/ or transmen.mp. 3 - exp counseling/ or counseling.mp. 4 - 1 and 2 |

43 |

| Cochrane | (transgender and fertility) | 1 |

| Total results | 1067 |

The goal of the search strategy was to be as comprehensive as possible. Since the topic of FP and counseling of transgender men is small and relatively recent, there were no limits applied, and broader search terms were used. The exploratory search began in PubMed, where the search detail and term mapping feature of the new interface greatly helped in selecting appropriate terms and eliminating ineffectual ones.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Included were articles in English related to transgender men, FP, and FP counseling. Excluded were articles solely pertaining to gender-affirming surgery, FP in the general population, and any abstracts, case reports, animal studies, textbooks, and opinion pieces.

Study Screening and Quality Assessment Tool

Two investigators (S.P. and D.S.) screened articles and were blinded to the other’s results. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. After review and discussion, a quality assessment tool in the form of a critical appraisal tool from the University of Oxford was used to test articles for validity, clinical relevance, and applicability. The University of Oxford provides critical appraisal worksheets, which can be found on their website (https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/critical-appraisal-tools).

Results

Summary Statement

This mini-review explores the topic of FP and counseling in transgender men, offering guidance for professionals counseling this patient population while highlighting the limited data currently available in the literature. A summary of the recommendations reviewed can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of analysis.

| Recommendation | No. and types of articles used to make recommendations | Summary |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Setting the stage for family-building counseling | 2 articles –

|

|

| 2. Timing of counseling | 8 articles –

|

|

| 3. Fertility preservation options | 20 articles –

|

|

| 4. Fertility preservation outcomes | 3 articles –

|

|

| 5. Effects of testosterone therapy | 8 articles –

|

|

| 6. Contraception counseling | 2 articles –

|

|

| 7. Attitudes toward family building | 4 articles –

|

|

| 8. Transgender parenting | 3 articles –

|

|

| 9. Multidisciplinary approach | 5 articles –

|

|

| 10. Barriers to family building | 10 articles –

|

|

Search Sample Description

The initial search yielded 1,067 articles (Fig. 1). Duplicates were removed, and 486 articles were then screened for eligibility, yielding 52 articles for analysis. After further evaluation with a quality assessment tool, 25 articles met inclusion criteria. Of the included articles, 8 were reviews, 5 were surveys, 4 were consensus studies, 3 were retrospective studies, 3 were committee opinions, and 2 were guidelines. The articles included in our analysis can be found in Table 3. After a thorough review, findings addressed by more than 2 articles were categorized, and the recommendations were summarized.

Figure 1.

Prisma flowchart.

Table 3.

Publications included for analysis.

| Article title | Year of publication | Journal of publication | Type of study | Brief summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine | 2021 | Fertility and Sterility | Committee Opinion | This is a summary of ethical considerations about fertility services provided to transgender individuals. All individuals should have access to fertility services regardless of gender identity. |

| Fertility Counseling for Transgender Adolescents: A Review | 2020 | Journal of Adolescent Health | Review | This review summarizes available literature regarding counseling and FP for transgender adolescents. |

| Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline | 2009 | Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism | Consensus | This guideline makes recommendations for hormonal treatments of transgender persons. |

| Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7 | 2012 | World Professional Association for Transgender Health | Guideline | This article from WPATH provides guidance for health professionals to assist transsexual and gender-nonconforming people with health care services, including primary care, mental health services, and fertility services. |

| Fertility desires and reproductive needs of transgender people: Challenges and considerations for clinical practice | 2019 | Clinical Endocrinology | Review | The authors review the available literature on fertility options and family-building experiences of transgender and gender-nonconforming people. |

| Fertility Preservation for Transgender Individuals: A Review | 2020 | Mayo Clinic Proceedings | Review | The article reviews the literature to summarize FP options available for transgender people and addresses barriers to care. |

| Effective fertility counseling for transgender adolescents: a qualitative study of clinician attitudes and practices | 2021 | BJM Open | Survey | By interviewing clinicians involved in fertility care for adolescents, these 5 elements were identified to be important for effective counseling: multidisciplinary team; shared decision making; patient engagement; personalized care; and reflective practice. |

| Health Care for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Individuals | 2021 | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists | Committee Opinion | ACOG offers recommendations regarding health care for transgender and gender-diverse individuals including information about FP and hormonal therapy. |

| Assisted reproductive technology outcomes in female-to-male transgender patients compared with cisgender patients: a new frontier in reproductive medicine | 2019 | Fertility and Sterility | Retrospective | In this study, ART outcomes in transgender male patients (even after testosterone therapy) were found to be reassuring. |

| Effect of Exogenous Testosterone on Reproduction in Transgender Men | 2020 | Endocrinology | Review | This article reviews the process and effect of gender-affirming HRT. It also reviews the parenting experiences of transgender men. |

| Oocyte retrieval outcomes among adolescent transgender males | 2020 | Journal of Assisted Reproductive Genetics | Retrospective | The article compared FP outcomes among adolescent transgender males with those of cisgender females and found that transgender males (before starting testosterone treatment) had an excellent response to ovulation stimulation. The number of oocytes retrieved in both groups was similar. |

| Formative development of a fertility decision aid for transgender adolescents and young adults: a multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study | 2020 | Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics | Consensus | Eighty multidisciplinary experts in reproductive medicine and pediatric transgender health care propose 5 topics and 25 learning objectives that may help transgender and nonbinary adolescents make fertility-related decisions. |

| Fertility preservation options for transgender individuals | 2020 | Translational Andrology and Urology | Review | The authors review current and future FP options for transgender patients, discuss barriers to access, and highlight current practice patterns. |

| Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion | 2019 | Fertility and Sterility | Committee Opinion | This article summarizes topics to address while providing FP counseling in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy. Clinical recommendations about currently available strategies and technologies are discussed. |

| ESHRE guideline: female fertility preservation | 2020 | Human Reproduction Open | Guideline | This guideline provides 78 recommendations to help providers counsel patients regarding FP options. The authors address all patients who may desire this counseling including those undergoing gonadotoxic treatments and transgender individuals. |

| Update on fertility preservation from the Barcelona International Society for Fertility Preservation-ESHRE-ASRM 2015 expert meeting: indications, results, and future perspectives | 2017 | Fertility and Sterility | Consensus | Twenty FP experts from ASRM, ESHRE, and the international society of fertility preservation gathered to publish this article. They review the available literature and published recommendations on indications for FP counseling, FP options available, and FP outcomes. |

| Fertility options in transgender people | 2016 | International Review of Psychiatry | Review | The authors review available literature about fertility options available to transgender individuals. |

| Fertility preservation for transgender adolescents and young adults: a systematic review | 2019 | Human Reproduction Update | Review | This review examines the available psychosocial and medical literature on FP for transgender adolescents. |

| Attitudes Toward Fertility Preservation Among Transgender Youth and Their Parents | 2020 | Journal of Adolescent Health | Survey | Transgender youth and their parents were surveyed. Results indicate that most transgender youth and parents do not find having a biological child important and are not willing to delay therapy for FP. |

| Low Fertility Preservation Utilization Among Transgender Youth | 2017 | Journal of Adolescent Health | Retrospective | The study found that despite high rates of FP counseling among transgender adolescents, there were low utilization rates. |

| A systematic review of fertility preservation options in transgender patients: a guide for plastic surgeons | 2021 | Annals of Translation Medicine | Review | The authors review the literature to summarize FP options and outcomes and aid plastic surgeons when counseling patients. |

| Proceedings of the Working Group Session on Fertility Preservation for Individuals with Gender and Sex Diversity | 2016 | Transgender Health | Consensus | This paper summarizes the results of a meeting of experts at an Oncofertility Consortium conference. The experts address FP options, barriers to care, and ethical considerations of FP in gender-nonconforming and transgender individuals. |

| Access, barriers, and decisional regret in pursuit of fertility preservation among transgender and gender-diverse individuals | 2021 | Fertility and Sterility | Survey | This study’s results show that the primary barrier to access is the cost of treatment. Respondents noted that family-building goals were not adequately addressed. Regret for not pursuing FP was noted in those who were undecided before the transitioning process. |

| Transgender and nonbinary Australians' experiences with healthcare professionals in relation to fertility preservation | 2020 | Culture, Health, and Sexuality | Survey | This survey explores the experiences transgender and nonbinary adults have had with healthcare professionals and the counseling these individuals had received before pursuing FP. |

| Knowledge, Practice Behaviors, and Perceived Barriers to Fertility Care Among Providers of Transgender Healthcare | 2019 | Journal of Adolescent Health | Survey | Various providers, including physicians, psychologists, mental health providers, nurses, physician assistants, and others, were surveyed to determine knowledge about FP options, practice behaviors, and perceived barriers to fertility care in the transgender population. |

ASRM = American Society for Reproductive Medicine; FP = fertility preservation; HRT = hormone replacement therapy; WPATH = World Professional Association for Transgender Health.

Findings and Recommendations

The number and types of studies referenced in each sub-topic are provided at the beginning of each section to help readers understand how recommendations are made and what literature is currently available. This information can also be found in Table 2.

Setting the stage for family-building counseling

In this section, 2 articles are referenced. One is a qualitative survey study, and the other is a committee opinion.

Before FP counseling, a proper environment must be ascertained. This includes creating a welcoming office environment, providing gender-neutral bathrooms, having proper pronouns on forms, and using gender-neutral connotations when engaging in discussions (7). The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) Committee’s opinion on this topic emphasizes creating an inclusive environment that helps reduce inequalities in care delivery to the transgender community (8). The ACOG also suggests increasing health care professionals’ knowledge about transgender care to avoid making assumptions about peoples’ orientation, training all office individuals about appropriate ways to ask about names and pronouns, developing proper ways to apologize for any mistakes with pronouns, ensuring appropriate signs and artwork are chosen, and having signs that clearly state the office’s nondiscrimination policy (8). All members of a health care team should ensure they have adequate training and a welcoming office environment for trans identified individuals, which can help reduce the stress and anxiety that accompanies gender transition.

Timing of counseling

In this section, 8 articles are referenced. Two are reviews, 2 are retrospective studies, 2 are consensus studies, one is a committee opinion, and one is a guideline.

All transgender individuals should be offered FP counseling before beginning transition since transgender individuals have similar family-building desires as cisgender individuals (1, 3, 4). Transgender youth and adolescents also should be counseled that the long-term impact of medical treatment on fertility remains unclear, and FP options currently available should be carefully reviewed and, where appropriate, all therapies offered (1, 5, 9, 10, 11). When counseling young adults, it is important to address how pubertal suppression medications affect the body, the psychosocial implications of pursuing treatments, and alternative family-building options such as adoption (12). Regardless of the age at which transition is desired, all transgender individuals should be offered FP counseling before transition is begun.

Fertility preservation options for transgender men

In this section, 3 articles are referenced. Two are reviews, and the other is a committee opinion.

FP can be pursued during any stage of gender transition, even after gender-affirming hormonal therapy has been initiated (6). However, when to discontinue testosterone before FP remains unclear (1). One review recommends at least 3 months, while another suggests waiting until the return of menses which may be delayed at least 6 months (6, 13). Regardless of whether transgender men have started the use of gender-affirming hormones, FP options should be reviewed with all patients.

Ovarian tissue cryopreservation

In this section, 9 articles are referenced. Five are reviews, 2 are committee opinions, one is a guideline, and one is a consensus study.

Mature gametes do not develop until mid-puberty (2). In prepubertal adolescence, ovarian tissue cryopreservation (OTC) is the only FP procedure that can be offered. This involves surgical excision of ovarian tissue for preservation for future thawing and maturing of follicles. As of 2019, American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) has removed the experimental label on OTC (14). However, a recent ASRM ethics committee recommends that decisions related to extirpation be delayed until adolescence when other less invasive options can be pursued (1). The ESHRE guidelines from 2020 state that tissue cryopreservation is an important option and the patient’s choice (15). The goal is to mature the preserved immature gametes in vitro or to later reimplant tissue into the pelvis (orthotopic) or elsewhere (heterotopic) (2, 16). Ovarian tissue transplantation comes with unwanted side effects, such as restoring female hormone activity. In vitro maturation of retrieved gametes from explants has also yet to be successful in humans (6, 13, 16, 17, 18).

There are no data on pregnancy outcomes on OTC for transgender men. However, in our view, potential concerns should be discussed with patients. For instance, the use of cryopreserved tissue requires additional surgery to reimplant the tissue. If successful, resumption of female hormone production may be undesirable for some individuals. Also, ovulation or ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization may require carrying the pregnancy. Oocyte cryopreservation before transition would likely be better for such patients. Considerations of cost are also complex and warrant discussion as procedures may not be covered benefits under health care plans. Although OTC is no longer considered an experimental procedure, patients should be counseled about the lack of data on human pregnancy outcomes, its side effects, including restoration of female hormone activities, and the additional surgeries it will require.

Oocyte or embryo cryopreservation

In this section, 4 articles are referenced. Three are reviews, and one is a consensus study.

Oocyte or embryo cryopreservations are presently preferred methods of FP in postpubertal transgender men. This requires controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) with daily hormonal injections and oocyte retrieval (6, 13, 17). If the individual has a male partner or a sperm donor, retrieved oocytes can be fertilized, and resultant embryos cryopreserved. COS requires exposure to female hormones and daily injections. Additionally, monitoring with transvaginal ultrasounds and oocyte retrievals is invasive and may worsen gender dysphoria (6, 13, 17). However, unlike tissue cryopreservation, oocyte and embryo cryopreservation are techniques well established in the field of assisted reproduction (16). Therefore, oocyte and embryo cryopreservation are the preferred methods of FP in transgender men.

Other family-building options

In this section, 4 articles are referenced. One is a qualitative survey study, 2 are reviews, and one is a retrospective study.

All family-building options, including fostering, adoption, and donor gametes, should be discussed at the time of counseling. Some studies suggest transgender men prefer adoption (2, 19). However, there are currently no studies of actual experiences of transgender individuals and adoption. Some may see adoption as a best way to have a positive parenthood experience and be easier than undergoing FP (20). Another study remarks that transgender men prefer adoption because they may not realize that family building through FP is also an option (6). Every individual’s family-building goal is different; therefore, all options for family building, including fostering, adoption, and donor gametes, should be discussed at the time of counseling.

Fertility preservation outcomes

In this section, 3 articles are referenced. Two are retrospective studies, and one is a review.

There are limited studies on FP outcomes in transgender men. However, the data reviewed is reassuring. In adolescents who have not begun hormonal therapy, case reports show excellent response to ovarian stimulation with no difference in the number of oocytes retrieved compared with cisgender females (11, 21). Individuals previously prescribed testosterone, and discontinued hormonal treatment for at least 3 months before COS, demonstrated higher mean number of oocytes retrieved than a cisgender cohort (9). Interestingly, in one study, transgender patients required a higher total dose of gonadotropins during stimulation than cisgender patients (9). However, according to the authors, higher doses may have been administered intentionally to maximize oocyte yield and minimize time off hormonal treatment. Despite the limited data available, individuals should be counseled that current studies show reassuring FP outcomes in transgender men.

Effects of testosterone therapy on fertility

In this section, 8 articles are referenced. Six are reviews, and 2 are retrospective studies, Testosterone therapy results in anovulation and amenorrhea, which is reported to occur around 6 months after initiating therapy (13). These hormonal effects appear reversible with cessation (2), including any lasting impact on fertility (9, 11, 21). However, there is debate about the possible long-term effects of testosterone therapy on ovarian histology. Chronic administration of testosterone may lead to follicular atresia, collagenized ovarian cortex, and hyperplasia of ovarian stroma changes seen in polycystic ovarian syndrome (5, 17). Another study suggests that testosterone has no impact on ovarian architecture, and if there is any effect, it is reversible (6). Currently, there are no recommendations regarding safe thresholds for doses of testosterone or the time of cessation of testosterone needed before pursuing FP options.

Contraception counseling

In this section, 2 articles are referenced. Both articles are review studies.

Contraception is important to address before beginning gender transition. There is a misconception that testosterone is an effective contraceptive. However, approximately a quarter of individuals on testosterone experience unplanned pregnancies (13). Even after the cessation of menses, pregnancy may occur (5). Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists do not reliably prevent pregnancy. Intrauterine devices, hormonal or nonhormonal methods, do not interfere with hormonal treatment and can be offered (5). Misconceptions about testosterone as a contraceptive should be addressed, and contraception counseling should be offered before hysterectomy or oophorectomy.

Attitudes toward family building

In this section, 4 articles are referenced. One is a qualitative survey study, 2 are reviews, and 1 is a retrospective study.

There is limited research studying attitudes regarding family building among transgender youth. As a result, most of the studies in this review address both transgender men and women. Among the youth, studies demonstrated that 66% of individuals desired to have children (2, 19, 20). However, only 20% of transgender youth found it important to have biological children, and only 3% were willing to delay hormonal therapy for FP (19). Another study showed that 45% of adolescents planned to adopt (20). It is important to note that 25% of adolescents stated at the time of transition that they were unsure of their intentions regarding genetic parenthood, and 48% acknowledged that their views about parenthood might change over time (2). Among parents of transgender youth, most indicated that they desired their child to have children at some point in their life (18). However, less than 20% of parents of transgender youth expressed that having biological children was important (18, 19).

In transgender adults, one review cited about 50% of transgender adults desired biological children, and 37% stated they would have pursued FP options if offered at the time of transition (2). Despite this, there was still low use of FP services in transgender adults, with one study citing only 3% of transgender men pursuing fertility services before transition (2). With limited studies about attitudes toward family building in transgender individuals, family building goals should not be assumed, and everyone should be thoroughly counseled about FP options.

Transgender parenting

In this section,3 articles are referenced. Two are reviews, and 3 are committee opinions.

Transgender parents are often socially stigmatized, which creates concern for the well-being of their children (1). Although there are few studies about the impact of transgender parenting on children, there are even fewer studies that suggest negative impact. If a parent transitions before the child is born, it is felt important to disclose the parent’s transgender identity early in childhood to avoid the risk of disclosure by someone else (1, 17). In cases of transitioning during a child’s life, children who were younger at the time of their parent’s transition showed better adaptation and healthier relationships with their parents (1, 17). ASRM reported children of transgender parents experienced few, if any, psychosocial problems, identity distress, or depression, and no studies demonstrated children experiencing gender dysphoria (1). The available data implied the development of children of transgender parents is not adversely affected (5). Transgender parents exhibit a similar commitment to their children and good parenting as cisgender counterparts. It is difficult to make accurate predictions about the parenting of transgender families, but the diversity of families and parenting styles are reassuring, and children can develop normally (1).

Transgender parents also may express a desire to pursue third-party reproduction. Although becoming parents via third-party reproduction is not an experience that is unique to solely transgender patients, it is a complex topic that should be included during FP counseling. Currently, ASRM recommends FP counseling to include the future use of donor gametes, donor embryos, and gestational surrogacy (14). If a patient desires to bank reproductive tissue or use donor gametes, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends considering infectious disease screening of the gametes. However, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration does not require recipients of donated gametes to be screened (14). Further details about the recommended screening tests can be found in the ASRM committee's opinion. Transgender individuals should be provided information about third-party reproduction options, the importance of disclosing a parent’s identity to a child early in childhood, and the limited but positive data showing normal development of children of transgender parents.

Effective methods of counseling using a multidisciplinary approach

In this section, 5 articles are referenced. One is a qualitative survey study, one is a review, one is a committee opinion, one is a guideline, and one is a consensus study.

The ASRM and ESHRE guidelines emphasize the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to FP counseling in transgender patients (1, 15). A survey of pediatricians, mental health, and obstetricians identified the following key elements for effective counseling in transgender adolescents: multidisciplinary approach; shared decision making, individualized approaches; and reflective practices from clinicians (7). A multidisciplinary team includes, but is not limited to, obstetricians, specialists in transgender medicine, reproductive endocrinologists, infertility specialists, mental health professionals, and financial advisors (15). This approach appears beneficial as it facilitates spreading information over multiple sessions, builds a community of support, and encourages communication (7, 18, 22). The authors also encourage clinicians to practice reflective practices, which they describe as being mindful of internal biases and cultural settings. (7). Given the challenging nature of counseling, reflective practices assist providers in being mindful of their own intrinsic biases. Using a multidisciplinary approach that includes fertility specialists, obstetricians, specialists in transgender care, mental health professionals, financial advisors, and patient navigators will help guide FP counseling in transgender patients.

Barriers to family building

In this section, 10 articles are referenced. Four are qualitative survey studies, 4 are reviews, one is a retrospective study, and one is a committee opinion.

A significant barrier to FP relates to the cost of treatments (5, 6, 7, 8, 13, 20, 23). Although the cost of ART is a barrier to many, regardless of gender identity, in the U.S., many transgender patients are uninsured or underinsured for gender-affirming treatments (6, 13). Additionally, transgender individuals experience social and economic marginalization, highlighted by ACOG (8), which leads to inequalities in health care access and outcomes. A U.S. national survey noted that 29% of individuals identified as transgender or other nonconforming gender identities were living in poverty, a figure much greater than experienced by the general population(8). Although there are limited data extrapolating the cost burden for patients who are transitioning, FP treatments often exceed $12,000 for assisted reproductive technology procedures plus storage fees (13). Other barriers include the lack of information, discrimination because of identity, invasiveness of procedures with worsening gender dysphoria, and fear of being denied hormonal treatment options after pursuing FP (7, 13, 18, 23, 24). Some transgender patients are concerned that health care providers act as gatekeepers to treatment and worry that a desire to have children in the future would deter physicians from providing hormonal treatment contemporaneously (24).

Providers also face barriers to counseling, including a lack of knowledge and insufficient training in transgender care. Due to the lack of standardized counseling tools, providers are unsure of best practices and fear they may put cisnormative biases on their transgender patients (13). Currently, gynecological oncologists have standardized guidelines for FP counseling for patients undergoing chemotherapy. There is evidence that suggests inconsistent counseling results in lower FP use whereas standardized counseling practices and education for physicians increase the number of patients choosing to pursue FP (13). Accordingly, one study showed providers with knowledge of patient-related barriers provided fertility counseling to transgender patients at a greater frequency than those who did not (25). Barriers in transgender care include a lack of sufficient training and knowledge about transgender patients in providers as well as direct barriers to access by transgender patients (due to cost and inequalities in healthcare); understanding, acknowledging, and addressing these barriers are important when providing FP counseling.

Conclusion

Using FP options among transgender individuals is lower than the rates of interest in family building through genetic parenthood (2). Although not every transgender patient is interested in having biological children, many indicate that they may have pursued FP if options were offered at the time of gender transition (2). Providers are responsible for giving thorough counseling but often indicate that they do not have adequate knowledge of transgender care (13). This discrepancy is alarming and speaks to the need for more comprehensive FP counseling and the need for proper guidance for physicians taking care of transgender patients.

A multidisciplinary approach may reduce barriers, improve FP outcomes, and decrease the burden on a sole provider to provide comprehensive counseling on a complex topic. The development of a standardized template, as outlined here, can improve provider knowledge and increase access to FP. However, further research is warranted to assess the applicability of standardized templates in actual practice. A small sample size of articles was included in our study, owing to the strict inclusion criteria and focus on transgender men. Additionally, our study was limited to articles in English. However, most data on this topic are published in English, with only 13 articles not in English discovered during our search. Finally, prospective studies on this topic are lacking.

In this mini-review, most of the articles detailed available FP options and barriers to care. Specifically, 13 of the articles discussed FP options, and 10 discussed barriers to care. However, only a few addressed setting the stage for counseling and experiences of transgender parenting (2 and 3 articles, respectively). Significant effort has clearly been made by the academic community on overall reproductive outcomes and family building for the transgender population. However, absent are uniform, comprehensive guidelines, or recommendations on how best to counsel this population. With the help of the suggested guidelines presented in our mini-review, we hope to further the conversation about family building in the transgender community.

-

•

Currently, there are no uniform guidelines with recommendations on how to counsel transgender men on fertility services. Providers should recognize when their own knowledge or experience limits their ability to provide comprehensive care or counseling to this community.

-

•

Providers should recognize that transgender men have similar family planning goals as their cisgender counterparts but may find it less important to have a biological child.

-

•

Providers should be aware of intrinsic biases that may affect how fertility counseling is offered and delivered.

-

•

Patients should be reassured that children of transgender parents are not adversely affected, and few experience psychosocial problems, identity distress, depression, or gender dysphoria.

-

•

Office spaces should be gender neutral, inclusive, and clearly state a nondiscrimination policy while avoiding assumptions about one’s orientation, names, or pronouns.

-

•

Fertility preservation counseling should be offered to all individuals regardless of their identity before they begin the transition process.

-

•

Providers should acknowledge and address all barriers to family building and fertility services that transgender patients may face, particularly the barrier of cost, which is the greatest barrier to care.

-

•

Providers should use a multidisciplinary approach when counseling fertility services.

Footnotes

S.U.P. has nothing to disclose. D.S. has nothing to disclose. S.D. has nothing to disclose. M.B. has nothing to disclose. M.V.S. has nothing to disclose. G.B. has nothing to disclose. J.H. has nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine Electronic address aao. Access to fertility services by transgender and nonbinary persons: an Ethics Committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:874–878. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai T.C., McDougall R., Feldman D., Elder C.V., Pang K.C. Fertility counseling for transgender adolescents: a review. J Adolesc Health. 2020;66:658–665. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hembree W.C., Cohen-Kettenis P., Delemarre-van de Waal H.A., Gooren L.J., Meyer W.J., 3rd, Spack N.P., et al. Endocrine treatment of transsexual persons: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3132–3154. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman E., Bockting W., Botzer M., Cohen-Kettenis P., DeCuypere G., Feldman J., et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, Version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13:165–232. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feigerlová E., Pascal V., Ganne-Devonec M.O., Klein M., Guerci B. Fertility desires and reproductive needs of transgender people: challenges and considerations for clinical practice. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2019;91:10–21. doi: 10.1111/cen.13982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ainsworth A.J., Allyse M., Khan Z. Fertility preservation for transgender individuals: a review. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95 doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lai T.C., Davies C., Robinson K., Feldman D., Elder C.V., Cooper C., et al. Effective fertility counselling for transgender adolescents: a qualitative study of clinician attitudes and practices. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Health care for transgender and gender diverse individuals: ACOG Committee Opinion Summary, Number 823. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137:554–555. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leung A., Sakkas D., Pang S., Thornton K., Resetkova N. Assisted reproductive technology outcomes in female-to-male transgender patients compared with cisgender patients: a new frontier in reproductive medicine. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:858–865. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moravek M.B., Kinnear H.M., George J., Batchelor J., Shikanov A., Padmanabhan V., et al. Impact of exogenous testosterone on reproduction in transgender men. Endocrinology. 2020:161. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqaa014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amir H., Oren A., Klochendler Frishman E., Sapir O., Shufaro Y., Segev Becker A., et al. Oocyte retrieval outcomes among adolescent transgender males. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:1737–1744. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01815-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolbuck V.D., Sajwani A., Kyweluk M.A., Finlayson C., Gordon E.J., Chen D. Formative development of a fertility decision aid for transgender adolescents and young adults: a multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2020;37:2805–2816. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sterling J., Garcia M.M. Fertility preservation options for transgender individuals. Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9:S215–S226. doi: 10.21037/tau.2019.09.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fertility preservation in patients undergoing gonadotoxic therapy or gonadectomy: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2019;112:1022–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson R.A., Amant F., Braat D., D'Angelo A., Chuva de Sousa Lopes S.M., Demeestere I., et al. ESHRE guideline: female fertility preservation. Hum Reprod Open. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoaa052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinez F., International Society for Fertility Preservation–ESHRE–ASRM Expert Working Group Update on fertility preservation from the Barcelona International Society for Fertility Preservation-ESHRE-ASRM 2015 expert meeting: indications, results and future perspectives. Fertil Steril. 2017;108:407–415.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Roo C., Tilleman K., T'Sjoen G., De Sutter P. Fertility options in transgender people. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2016;28:112–119. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2015.1084275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baram S., Myers S.A., Yee S., Librach C.L. Fertility preservation for transgender adolescents and young adults: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update. 2019;25:694–716. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persky R.W., Gruschow S.M., Sinaii N., Carlson C., Ginsberg J.P., Dowshen N.L. Attitudes toward fertility preservation among transgender youth and their parents. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67:5839. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nahata L., Tishelman A.C., Caltabellotta N.M., Quinn G.P. Low fertility preservation utilization among transgender youth. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan M., Bustos S.S., Kuruoglu D., Ciudad P., Forte A.J., Kim E.A., et al. Systematic review of fertility preservation options in transgender patients: a guide for plastic surgeons. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:613. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-4523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finlayson C., Johnson E.K., Chen D., Dabrowski E., Gosiengfiao Y., Campo-Engelstein L., et al. Proceedings of the working group session on fertility preservation for individuals with gender and sex diversity. Transgend Health. 2016;1 doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vyas N., Douglas C.R., Mann C., Weimer A.K., Quinn M.M. Access, barriers, and decisional regret in pursuit of fertility preservation among transgender and gender-diverse individuals. Fertil Steril. 2021;115:1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartholomaeus C., Riggs D.W. Transgender and non-binary Australians' experiences with healthcare professionals in relation to fertility preservation. Cult Health Sex. 2020;22:129–145. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2019.1580388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen D., Kolbuck V.D., Sutter M.E., Tishelman A.C., Quinn G.P., Nahata L. Knowledge, practice behaviors, and perceived barriers to fertility care among providers of transgender healthcare. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]